95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Polit. Sci. , 22 July 2021

Sec. Political Participation

Volume 3 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2021.676672

This article is part of the Research Topic Political Trust View all 9 articles

We test the importance of responsiveness, performance and corruption to explain the evolution of political trust in Spain between 1997 and 2019. To this end, the study analyses two longitudinal datasets, namely, a repeated cross-sectional dataset from the Spanish samples of Eurobarometer and an individual-level panel survey conducted during a period of economic recovery in 2015. The study finds that perceptions about political corruption and responsiveness matter greatly in shaping political trust and to a lesser extent economic performance. Although the Great Recession is likely responsible for the sharp decline in trust towards political parties and the parliament between 2008 and 2012, the analysis suggests that trust in representative institutions remains low even after the Recession because of a series of devastating corruption incidents and a perceived lack of responsiveness of the political system. On the other hand, the study finds indications that trust in the judicial system might have been mainly affected by perceptions of corruption.

Political trust is in decline in many contemporary democracies. Indeed, the growing literature on political trust has already taught us much about the manifold causes of this downturn. Economic and social performance is at the top of this list, especially in Europe where, in the aftermath of the 2008 Great Recession, the economic and social crises had been put forward as one main explanation (Ellinas and Lamprianou, 2014; Dotti Sani and Magistro, 2016; Van Erkel and Van Der Meer, 2016; Dustmann et al., 2017; Foster and Frieden, 2017; Van der Meer, 2017; Ruelens, et al., 2018) together with the fiscal crisis and its consequences in terms of welfare retrenchment (Polavieja, 2013; Kumlin and Haugsgjerd, 2017). Other scholars have stressed the significance of the shortcomings of the political process (Grimes, 2006; Van der Meer, 2010; Hakhverdian and Mayne, 2012; Chang, 2013; Bauhr and Grimes, 2014; Torcal, 2017; Van der Meer and Hakhverdian, 2017). These shortcomings are manifested in citizens’ perceptions that political actors are not responsive to their demands and concerns which, in turn, have a negative effect on political trust (Torcal 2014; Linde and Peters, 2020). Finally, political trust has also been linked to political corruption (Della Porta, 2000; Pharr, 2000; Uslaner, 2002; Uslaner, 2017).

However, only limited evidence exists on how each of these factors shapes political trust over time. This study contributes to the debate by providing two complementary longitudinal analyses of these factors in Spain: we first analyse a pooled dataset based on the Spanish samples of the Eurobarometer between 1997 and 2019, where our focus lies at the contextual-level. The rest of the analysis is based on an individual-level panel survey during 2015.

The case of Spain is well-suited for testing the effects of the three factors on political trust, as periods of political stability and economic growth have alternated periods of great economic and political distress. Moreover, political trust has declined substantially since 2008 despite its already low levels, becoming one of the European countries with the lowest levels of political trust (Torcal and Christmann, 2020). By the end of 2019, only one in 10 citizens expressed trust in the representative institutions of the Spanish state.1 This renders it an interesting country to study.

This remarkable decline in political trust in Spain has opened a debate on its causes, reflecting the larger debates in this field of study. Some scholars attribute it to the 2008 Great Recession and its social consequences that were particularly harsh in Spain (Polavieja, 2013). Other authors blame the defective functioning of the political process during the crisis (Orriols and Cordero, 2016). In this latter line of thought, the economic crisis and the subsequent austerity measures constituted a ‘stress test’ of Spanish democracy in the eyes of most of its citizens, resulting in a negative assessment of its functioning (Torcal, 2014).

Yet there also exists a third, alternative explanation for the deterioration of political trust in Spain: the great political distress caused by a series of major corruption scandals in the 2010s. In 2012, the newly elected conservative Prime Minister, Mariano Rajoy, not only faced the debt crisis but also was confronted with a series of corruption scandals related to the illegal funding of his political party, the Partido Popular (PP), and the subsequent salience of the topic in the political agenda (Orriols and Cordero, 2016). Scandals also affected, although to a lesser extent, other political parties, such as the Partido Socialista Obrero Español (PSOE) in the Andalusian region and Convergencia i Unió (CiU), the former conservative Catalan nationalist party.

The remainder of the article is structured as follows: First, a summary of the literature is provided and focuses on the three explanatory factors to elucidate political trust and on which the study formulates empirical expectations/hypotheses. Second, the Spanish case is described to provide in-depth information about the manifold corruption incidents that haunted Spanish politics in the previous decade. The third section describes the research design, the model specification, the datasets employed and the results of two complementary analyses. The last section concludes and puts the empirical findings into perspective.

In recent academic debates, scholars often emphasise “performance” evaluations when it comes to explaining trends in political trust in contemporary democracies. Here, experts often adopt a “trust-as-evaluation” approach, in which people tend to trust institutions more or less following rational calculations and depending on how trustworthy they perceive each institution in relation to its benchmarks (van der Meer and Hakhverdian, 2017). Attention is directed towards aspects related to the output-side of the political system, that is it, whether the (democratic) government is effective and performs well, ensuring wealth and affluence (Scharpf, 1999; Rothstein, 2009; Martini and Quaranta, 2020).

The stark decline of political trust among the worst affected countries of the 2008 economic and fiscal crisis helped to confirm the idea that people change their attitudes because of instrumental evaluations of economic and social conditions. Hence, political trust at the societal-level depends on the institutional capacity to meet and represent citizens’ social and economic needs and demands, which are mostly rooted in socio-economic (self-) interest. Thus, economic stewardship is typically identified as a leading cause of trust: when citizens are dissatisfied with economic performance, distrust of government ensues, whereas the reverse effect is produced when economic prosperity abounds (Hetherington, 1998; Citrin and Luks, 2001; Listhaug, 2006; Offe, 2006).

This effect could be based on two different logics or mechanisms: one direct and one more indirect. The first may be the result of citizens’ sociotropic considerations of the general situation, such as their retrospective evaluation of the country’s economy (Listhaugh and Wiberg, 1995; Miller and Listhaug, 1999; Newton and Norris, 2000; Newton, 2007). In addition, awareness of the depth of the economic crisis is likely to create uncertainty about individual economic futures as well, leading many to feel economically vulnerable (Mughan and Lacy, 2002), negatively affecting institutional trust. Thus, further instrumental economic calculations of the people could also be intertwined with these general evaluations of output performance, affecting institutional trust. Individual experiences of economic hardship can reduce citizens’ degree of trust in institutions whether lasting or transitory (Clarke et al., 1993; Brooks and Manza, 2007). In accordance, recent studies have shown that fluctuations in economic performance affect the levels of political trust over time (Dotti Sani and Magistro, 2016; Van Erkel and Van der Meer, 2016; Van der Meer, 2017; Ruelens, et al., 2018). Finally, following the same logic (Rothstein, 2003; Kumlin, 2004), some authors have also linked the present welfare state retrenchment (Alesina and Wacziarg, 2000; Kumlin and Haugsgjerd, 2017) and the experience of unemployment (Gallie, 1994; Polavieja, 2013) with declining trends in institutional trust. Thus, social and economic performance evaluations can affect institutional trust and such a decline in trust could be the product of more instrumental evaluations of the personal consequences of the crisis.

Alternatively, several studies also argued that political institutions are increasingly perceived as unresponsive to citizens’ demands (Norris, 2011; Hakhverdian and Mayne, 2012; Harteveld et al., 2013) and that the decrease in political trust is a symptom of perceived deficits in the functioning of the political process (Alesina and Wacziarg, 2000; Pharr et al., 2000). This process-oriented research was initiated by (Hibbing and Theiss-Morse, 1995; Hibbing and Theiss-Morse, 2002), and it has been paying attention to either subjective perceptions or objective indicators of ‘institutional fairness’ (Anderson and Tverdova, 2003; Kumlin 2004; Grimes, 2006; van der Meer, 2010; Hakhverdian and Mayne, 2012; Linde, 2012; Bauhr and Grimes, 2014; Persson et al., 2017; van der Meer and Hakhverdian, 2017). Although, this is an important element to consider, citizens’ evaluation of the political process also entails responsiveness, which can be defined as the short-term match between what people want and what they receive from political parties and leaders in terms of policies and policy output (Linde and Peters, 2020: 291; see also Torcal, 2014). In many cases, this hypothesis had not been contrary to the importance of the instrumental economic/social calculations of economic performance but rather complementary. Thus, the increasing political distrust of the public is probably not only a direct effect of the Great Recession and its social consequences, as has been argued, but also the consequence of how responsive political authorities and political representatives have been with citizens’ demands in coping with the consequences of the economic crisis (Torcal, 2017).

Finally, another factor considered by the comparative literature on the evolution of political trust is the negative effect of political corruption. Initially, an essential aspect of this literature is linked to the literature on output performance, which highlights the indirect effect of corruption through its effects on the procedural performance of political institutions or the difficulties it poses on governments in producing policies and services in response to the demands of the general public (Rothstein, 2003; Warren, 2004; Rothstein and Uslaner, 2005; Catterberg and Moreno, 2006; Rothstein and Stolle, 2008; Ariely and Uslaner, 2017).

The studies on this topic have employed two approaches to examine the effects of corruption on political trust. The macro-contextual approach emphasises the aggregate performance of institutions in avoiding corruption (Mishler and Rose, 2001; Harring, 2013) and the necessity of creating auditing mechanisms for its control (Rothstein 2021). Alternatively, the micro-level approach links individual perceptions of corruption to the political integrity of institutions and main political actors (i.e. politicians and political parties), which negatively influences political trust (Chang and Chu, 2006; Uslaner, 2011; Hakhverdian and Mayne, 2012; Chang, 2013; Uslaner, 2017). Accordingly, political corruption is not so much an indicator of the performance of the political process but of the citizens’ perceptions of elite and political actors’ probity which could spread to the rest of the society (Rothstein, 2003), constituting what it has been called as one of the three “p” factors for explaining political trust: performance, process and probity (Citrin and Stoker, 2018; Hetherington and Rudolph, 2015). As, Wang (2016) argued, the focus should be less on the efficiency of the government due to corruption but on its ethics. In other words, leaders’ misconduct during office (Della Porta, 2000; Pharr, 2000) produces a general sense of lack of probity in the institutions and their incumbents.

Previous studies on the relative importance of these three factors are limited and are often based on cross-sectional analysis at the individual or contextual level or do not jointly test these explanations to evaluate the importance of these factors. Thus, the present study contributes to the literature by conducting a longitudinal analysis of the effects of these three factors on political trust. Furthermore, the study focuses on a single country, which allows for a panel analysis at the societal and individual levels to be conducted. Thus, we evaluate the relative effects of performance, responsiviness and corruption on political trust based on the following hypotheses:

H1A: In times of good economic performance respondents tend to show higher levels of political trust.

H1B: Positive evaluations of the economy lead to increased political trust among respondents over time.

H1C: Increased economic insecurity decreases political trust among respondents over time.

H2A: In times during which people perceive their political system as responsive, respondents tend to show higher levels of political trust.

H2B: Positive evaluations of political responsiveness increase political trust among respondents over time.

H3A: In times of major incidents of corruption, respondents tend to show lower levels of political trust.

H3B: Perceptions of corruption decrease political trust among respondents over time.

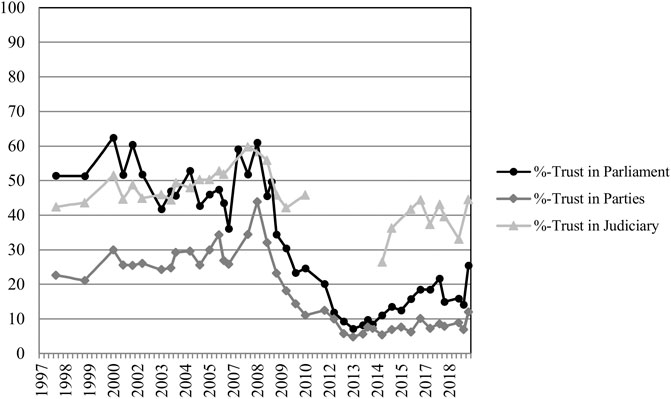

As can be observed in Figure 1, political trust in Spain was gradually increasing during times of the economic boom at the end of the 1990s/first half of the 2000s—although at low levels and depending on the type of institution (with the judiciary ending up at the top). Yet, since 2008, political trust in Spain has seen a dramatic decline— even compared to the rest of Europe (Torcal and Christmann, 2020)—from which it has not recovered by the end of the 2010s. This decline, however, has been more conspicuous for the institutions of representation (parliament) and political actors (political parties) than for the legal system. This trend is not only remarkable but also unique because a similar downswing had not been observed during precedings economic crises in Spain (Montero et al., 1997).

FIGURE 1. Political trust in Spain (1997–2019). Notes: Measured on a quarterly basis. Weighted percentages. The values for political trust are interpolated (line); dot show the observed values. Eurobarometer.

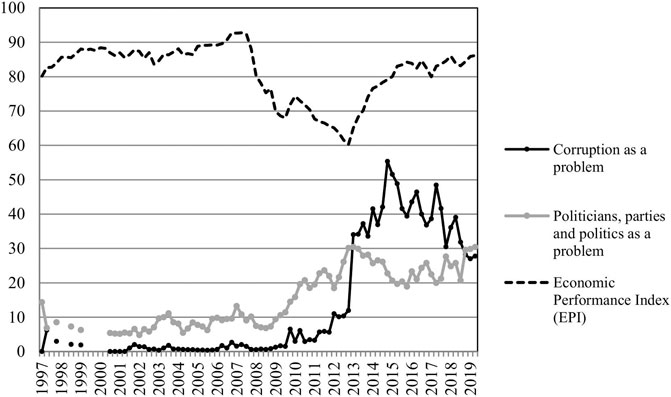

Still, it seems plausible to connect this decline in trust with the deterioration of the Spanish economy after the 2008 financial crisis. In particular, the deterioration of the economic situation as measured by the Economic Performance Index (EPI) is closely mirrored by the decline in political trust as we can observe in Figure 2 (for an explanation of this index and additional economic indicators, see the Supplementary Material). On the other hand, a more recent period of economic growth and unemployment decrease starting at the end of 2013 has not been entirely reflected in increasing levels of political trust, pointing to the possibility of other explanations for its evolution over time.

FIGURE 2. Economic performance and public evaluations in Spain (1997–2019). Notes: Measured on a quarterly or yearly basis. Sources: OECD Stat, IMF WEO Database, Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas.

Another plausible alternative explanation for the dramatic decline in political trust in Spain is the worsening evaluations of institutional/political responsiveness, potentially also as an indirect effect of the Great Recession. Subsequently, within a short time period, public concerns about the actors of political representation have been rising since 2009, independent from other concerns such as political corruption. This is visible in the increasing percentage of Spaniards expressing that the main problem in Spain was politicians, political parties and politics in general (see Figure 2), reflecting an increasing concern about the responsiveness of the political system. The problem also manisfested itself in the share of people who strongly agreed with the statement “politicians do not worry what people like me think or want …,” which grew from 12.4% in 2000 and 15.8% in 2008 to 26% in 2009, 42% in 2011 and 46.4% in 2014, according to the data collected by the Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (CIS) in Spain.2 A similar evolution was observed with regard to the statement, “… people in power only look after their personal interest …” with 18 and 16.4% in 2000 and 2008, respectively, to 30% for 2009, 42.6% in 2011 and 47.6% in 2014 of people strongly agreeing.3

Thus, it seems very clear that the economic crisis initiated in 2008 was combined with a generalised perception that the system was not responsive to citizens demands and that the main parties that traditionally governed are ‘essentially the same’ (Bosch and Durán, 2019), opening a road for the establishment of new parties, especially Podemos (a radical left-wing party that had been founded just a few months before the 2014 European elections), a party calling for total regeneration of the political system while presenting more radical proposals to address citizens’ discontent (Ramiro and Gomez, 2017). This party obtained surprisingly 8% of the vote in those particular elections and continued growing with a 20.7% of voters’ support for the following national elections in 2015.

Since 2012, a significant number of political scandals emerged from within the Spanish public sphere. The list of these scandals included those that influenced relevant important actors, such as the conservative incumbent party PP, at the time, and its most notorious historical leaders (Orriols and Cordero, 2016). In this case these scandals were related to the presence of illegal mechanisms for party funding (e.g. the Gürtel case and the Bárcenas papers). In addition, the main opposition party, the PSOE, was primarily affected by the misappropriation of funds from a programme for re-training long-time unemployed citizens in Andalusia (known as Expediente de Regulación de Empleo—ERE). Scandals were also present in Catalonia, affecting the former President of the Generalitat, Jordi Pujol, and other members of his family, who were eventually convicted for corruption. Finally, related to these scandals, there was the illegal financing of the Convergencia i Unió (CiU), the former conservative Catalan nationalist party, which seemed to receive important sums of money in exchange for public contracts (the so-called “3% bribes”). However, the public’s preoccupation with corruption extended beyond the scandals attributed to the main parties. On several occasions, financial institutions became involved. For example, leaders from different parties who formed part of the Board of Directors of Bankia were accused of illegally spending €15.5 million between 2003 and 2012 using “black” credit cards for personal purchases (Águeda, 2014).

The aforementioned scandals have also been reflected in the increasing public concern regarding cases of corruption. According to the data taken from the monthly barometers of the CIS in Spain, the percentage of respondents who answer that “corruption and fraud” are among the “three principal problems that currently exist in Spain” abruptly soared after 2012, reaching its highest level at the end of 2014 (see Figure 2) and remaining relatively high until 2019 (the last observation point of the present study). Conversely, corruption was not considered one of the most significant problems in Spain in the 15 years prior to 2012 (unlike concerns and reservations expressed for politicians and political parties, which started to rise substantially after 2009 from an already higher level).

The remainder of this article performs a longitudinal analysis of political trust at both the aggregate and the individual level. At the contextual level, we analysed a pooled dataset based on repeated cross-sectional surveys performed in Spain by the Eurobarometer, which allows us to assess if changes in the objective economic and political performance is related to the dramatic decline in political trust at the national level. At the respondent level, the study employed three waves of an individual-level panel dataset CIUPANEL,4 which allowed us to examine the effects of dynamic political and economic perceptions, political responsiveness and political corruption on political trust among the same individuals over time.

We have constructed a pooled dataset based on 43 representative surveys conducted by the Eurobarometer to test the contextual effects of the economic and political process and political corruption on political trust over time in Spain.5 This includes individual-level information from 33,000 respondents between 1997 and 2019 (see Table A.1 in the Supplementary Material). As multiple surveys have often been conducted in the same year, we decided to use quarters as the unit of time at the contextual level. Thus, our unit of analysis was the survey respondent (level 1) who was nested in quarters (level 2). We used three dependent variables for political trust in this study: trust in parliament, trust in political parties and trust in the judiciary. These variables have been measured dichotomously in the Eurobarometer surveys with two categories “tend not to trust” and “tend to trust” (see Supplementary Material for detailed descriptions of the dependent variables).

We have chosen to use objective indicators and proxies for the measurement of the explanatory variables: economic performance, perceptions of responsiveness and political corruption. The most frequently used longitudinal variables to describe the performance of an economy are unemployment, public debt, economic growth and inflation. Here, we opted for calculating the EPI that combines information for all of these variables in a comprehensive index (see Supplementary Material for details); thus avoiding issues created by collinearity between these variables in the analysis. To measure the level of democratic responsiveness in Spain (as a proxy for democratic process performance), we collected the percentage of respondents who answered that “politicians and parties” were among the “three principal problems that currently exist in Spain” using the same monthly barometers of the CIS in Spain mentioned above. Finally, we measured the salience of political corruption by the percentage of respondents who answer that “corruption and fraud” are among the “three principal problems that currently exist in Spain,” again, employing the same CIS database. We decided against the usage of indicators based on expert surveys such as Transparency International and the World Bank’s aggregate measures of corruption as they remain unexpectedly stable for Spain between 1995 and 2015—despite the considerably serious (political) corruption scandals in the mid-1990s and the 2010s.

Political institutions such as the electoral system, the parliamentary type of executive and the role of the Supreme Court or the asymmetrical bicameralism remain constant for the period under consideration. The high disproportionality of the Spanish electoral system has led to a two-party system with an alternation of power between the socialist PP and the conservative PSOE, where only regional parties could successfully compete with both parties in few electoral districts until very recently (Torcal and Lago, 2007). This has severely limited party system fractionalisation in the legislature, leading to highly concentrated single-party governments. However, there has been a significant change in the supply of electoral parties since 2011, which might have altered citizens’ political trust despite the continuity of the institutional context. In our study, party supply is measured using the effective number of electoral parties (ENEP) (for further detail, see the Supplementary Material).

Furthermore, because democratic elections can be expected to enhance people’s feelings about their political institutions and the political process, we controlled for whether a survey was conducted during or shortly after a parliamentary election (Esaiasson, 2011; Blais et al., 2015). We did so by including a dummy variable that captures proximity to elections by taking value 1 if a survey was conducted during the 6 months after a national parliamentary election. See the supplementary materials for more details on the measurement of all contextual-level variables.

At the individual level, we controlled for socio-demographic variables such as age, gender (reference category = female) and education. Age is measured in years, whereas education is measured categorically as the age at completion of studies (reference category = “over 19,” other categories = “less than 15,” “15–19” and “still studying”). Moreover, we accounted for the employment status (reference category = “employed, student, retired or other,” other category = “unemployed”), the marital status of the respondents (reference category = “single, separated, widowed or divorced,” other category = “cohabitating or married”) and urban residence (reference: less than 10,000 inhabitants; otherwise, more than 10,000 inhabitants). Finally, we included political discussion as an indicator of cognitive mobilisation (reference: never) and the individual position on the left–right scale.

The inclusion of other individual-level variables would create large temporal gaps in the dataset. Hence, other potential variables of interest, such as evaluations of the economy, could not be added to the model because they are only included in relatively recent waves of the Eurobarometer. However, we believed that these limitations are outweighed by the fact that we estimated our model based on hierarchical data covering more than two decades (1997–2019) of Spanish democracy.

We fitted multilevel probit models, where survey respondents are nested within time points (quarters), because trust in the Spanish parliament, trust in parties and trust in the judiciary are measured with dichotomous variables in the Eurobarometer (trust vs. distrust). We estimated one full model for each institution, which includes the individual-level control variables previously discussed, the context-level control variables and the three contextual variables of interest: the corruption aggregate measured (percentage of respondents who answer that “corruption and fraud” are among the “three principal problems that currently exist in Spain”); the political receptiveness aggregate measured (percentage of respondents who answer that “politicians and parties” are among the “three principal problems that currently exist in Spain”) and the EPI. Missing values were deleted listwise.

The analysis of the individual-level CIUPANEL panel data set in Spain (Torcal et al., 2016) can provide an additional test to explain change within individuals over time. The non-probability panel consists of an online sample of the Spanish population followed over six waves between 2014 and 2016. Quotas in the first two waves were applied for gender, age, education, size of city/village of residence and autonomous regions; in the third to sixth wave quotas were only applied for gender, age and autonomous regions to recontact as many respondents as possible. A study comparing this online panel with the probabilistic sample of the European Social Survey in Spain showed that the quality of estimations in terms of reliability and validity for political trust measures is similar to the non-probability online sample from the commercial provider Netquest (Revilla et al., 2015). For the present study, we used waves 3, 4, and 5 of this panel, which were administrated in December–January 2014, May–June 2015 and December 2015. The participation rate of wave 3 was 82%, 84% for wave 4 and 88% for wave 5. Descriptive statistics for all employed variables are provided in the supplementary materials. More information on the sample composition are provided in the data protocol of the CIUPANEL. Trust in parliament, trust in parties and trust in the judiciary were asked in a similar way as in the Eurobarometer, although measured with an 11-point response scale, ranging from 0 (absolutely do not trust) to 10 (full trust).

Here, we relied on a question regarding respondents’ retrospective evaluations of the economic situation to test the effects of the economic outputs of the political system. In the CIUPANEL, the following question is asked: “In the last the last 12 months would you say that the economic situation in Spain in general is: 1) going much better, 2) going a little better, 3) the same, 4) going a little worse, or 5) going much worse?”. We measured the personal economic security and well-being by creating an index based on the factor scores of the following questions: (A) “Today, to what extent are you worried about paying the bills for your home?”; (B) “Today, to what extent are you worried about needing to reduce your standard of living?”; (C) “Today, to what extent are you worried about having a job?” and (D) “Today, to what extent are you worried about paying back bank loans or mortgages?” with the answer categories being 4) very worried; 3) somewhat worried; 2) not very worried and 1) not at all worried.

To tap into perceived responsiveness (external efficacy), we created an index based on the factor scores of the following questions: (A) “To what extent would you say that politicians care what people like you think?” and (B) “To what extent would you say that the political system in Spain allows people like you to have something to say in what the government does?” with the answer categories ranging from (0) not at all to (10) very much. To measure perceived political corruption, we employed the following question: “In your opinion, how many politicians in our country have been involved or related with corruption?” with the answer categories being 1) almost none of them; 2) a few of them; 3) many of them and 4) almost all of them.”

At the individual level, we controlled for respondent’s left–right self-placement and political interest. In addition, we included a question on government performance evaluation to separate the potential effect of incumbent performance (support) from a purely economic performance evaluation (see the Supplementary Material for more details).

To analyse the CIUPANEL panel data, we estimated three “two-way fixed-effects (FE)” regression models. This method allowed us to study the effects of changes in political and economic perceptions, perceived responsiveness, and corruption on changes in trust in parties, the parliament and the judiciary within the same individuals, while controlling for time-invariant unobserved characteristics of the respondents. Wave dummies (ref = wave 3) were included to control for time-specific unobserved confounders. Missing values were deleted listwise.

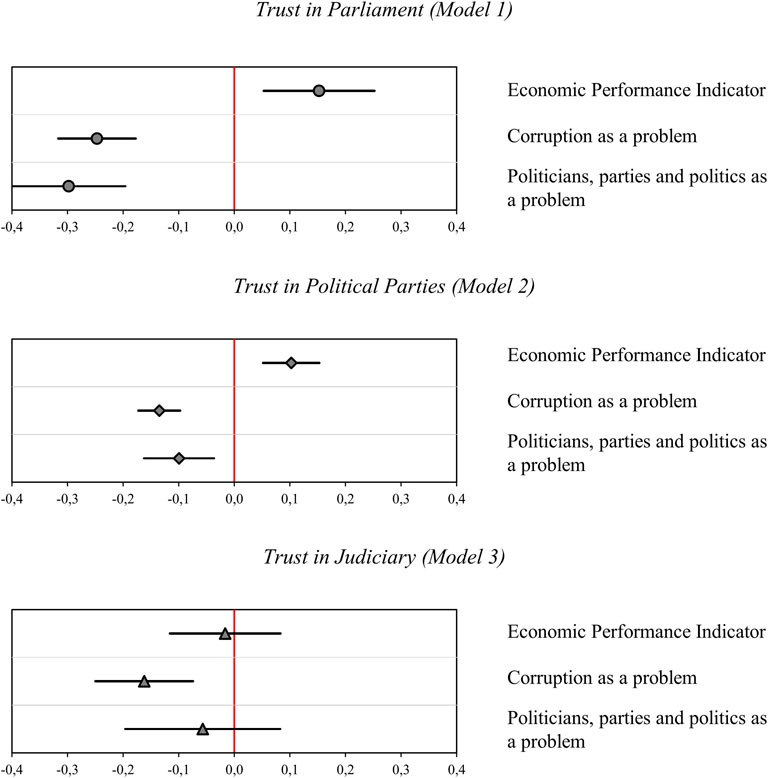

The results of our longitudinal contextual-level analysis are summarised in Table 1. To facilitate interpretation of the output of the estimation we report standardised coefficients for continuous variables. The underlying scale of a probit model also has a standard deviation of one so all the coefficients can be easily interpreted. In addition, we report the predicted probabilities of changing from not trusting to trusting over the EPI, democratic responsiveness and perception of corruption (maximum observed value–minimum observed value) in Figure 3, holding all the other variables at their means. We will not interpret the individual-level control variables as we have mainly included them to account for compositional effects.

FIGURE 3. Predicted change in probabilities (Table 1). Notes: Predicted change in probabilities of trusting over the range of explanatory variables. Predictions are based on Model 1 (trust in parliament), Model 2 (trust in political parties) and Model 3 (trust in judiciary). For the predictions all other variables are held at their means. Lines represent (95%-CI).

We first decomposed the variances in political trust by estimating empty models. These “null” models provide the information to compute the Intraclass Correlation Coefficients (ICC), which reflects the share of variation in political trust that can be attributed to the individual and the aggregate levels. The null models show that 75 and 96% of the variation in the data can be attributed to the respondent level. Conversely, around 24% (parliament), 16% (political parties) and 4% (judiciary) of the variance belong to the quarter levels, which are a sizeable degree of clustering, especially for the two first institutions.

Let us now turn to the longitudinal results at the context-level of the full model also displayed in Table 1. First, the effect of economic performance is substantial and significant for trust in parliament and trust in political parties, providing support for H1A. However, we find no effect of economic performance on trust in the judiciary. Yet, we must also note that the Eurobarometer has not asked for trust in the judiciary between 2011 and 2014, thereby limiting variability on the measure and increasing the risk of committing a type-2 error.

Second, the measure capturing the salience of political corruption is strong and significant in all models (confirming H3A), even when controlling for the other performance indicators. As we can see, the various political corruption scandals in the last years have resulted in an increase of the importance given to corruption as a main problem by citizens, decreasing the probability of trusting institutions by more than 25 per cent for the parliament, around 10 per cent for the political parties and more than 15 per cent for the judiciary.

Finally, another significant and substantial factor for explaining the negative evolution of political trust in Spain are the increasing concerns about politicians, political parties and politics, providing support for H2A. The effect size is comparable to the effect of political corruption for trust in parliament and trust in political parties. However, we find no effect of our political responsiveness measure on trust in the judiciary, which mostly depends on the time evolution of perceived corruption, showing how political trust is also object-dependent.

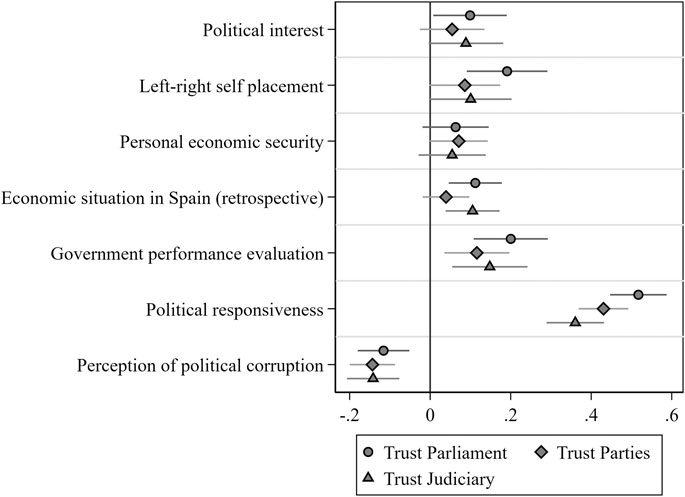

Table 2 presents the results of the three linear FE models. To facilitate the interpretation of the results, all the explanatory variables were standardised to an average of 0 and a standard deviation of 1. The marginal effects are plotted in Figure 4. Overall, the fit of the models was good, and they can explain between 13 and 20 per cent of the within variation of the dependent variables.

FIGURE 4. Predicted Change in Probabilities for Fixed Effects Models (Table 2). Notes: Based on Model 4 (trust in parliament), Model 5 (trust in political parties) and Model 6 (trust in judiciary). Horizontal Lines represent (95%-CI).

In Table 2, we can see that individuals’ political trust in these three institutions strongly responds to changing perceptions regarding two out of the three factors under investigation, that is, political responsiveness and perceptions of corruption for which we find consistent longitudinal effects within respondents for all trust items. All coefficients for these two variables are strong and point in the expected direction, confirming H2B and H3B. However, changes in the evaluation of the economic situation in Spain or in the personal economic situation appear to have only a small (H1B) or null effect on changes in political trust (falling to reject the null hypothesis for H1C).

However, this does not imply that changes in economic perceptions and conditions are not related per se with trust in representative institutions as our analysis provides only a short snapshot of the overall dynamics. Indeed, the results of this analysis fit well with the trends displayed in Figures 1, 2, where the recovery of the Spanish economy has not been translated in a recovery of trust in political parties and the parliament. Consistently, we find strong effects for our indicators of political responsiveness and political corruption—at a time where public concerns about the political process and probity have been highly salient. Given also the results of the long-term analysis of political trust at the national level presented in Table 1, this could be interpreted as an indication that the effect size of the three factors might vary at specific contexts/periods or that the effect is stronger during times of crisis—first, the economic crisis and later the perceived political crisis with its series of high-profile corruption incidents and a faltering belief in the performance of the political process.

For observational data there are two broad endogeneity concerns that stand in the way of causal inference: omitted variables and selection bias. Although our longitudinal analysis excludes the possibility that time-invariant unobserved variables at a higher level are biasing the “within” coefficients (“within-person” or “within-country”), there might still be other time-varying variables that are not accounted for in our models. Regarding the longitudinal analysis of the Eurobarometer data it appears rather unlikely for there to be a substantial reverse causation for the economic variables at the contextual level (the economy is not driven by political trust). However, this concern is more significant when we seek to explain one political attitude with another political attitude. For one, we believe that reverse causation is unlikely for the second indicator (“corruption as a problem”) on an empirical basis.6 Yet we cannot rule out the possibility of reverse causation for our third indicator (“politicians, parties and politics as a problem”).

As a robustness test for the contextual-level analysis of the pooled Eurobarometer surveys, we re-estimated our analysis with an alternative measure for process performance: the “government and opposition index,” measuring support for the main government and opposition parties (see Table A.5 in the Supplementary Material). As a robustness test for the individual-level panel analysis we re-estimated the models omitting government evaluations owing to concerns of collinearity with economic evaluations (compare Table A.7 in the Supplementary Material). Furthermore, we also estimated random effects (RE) models with lagged independent variables (see Table A.8 in the Supplementary Material). In summary, we found that the results for all variables of interest were similar in all different model specifications.

Political trust in Spain was gradually increasing during times of the economic boom at the end of the 1990s/first half of the 2000s but has suffered a dramatic decline after the financial and debt crisis after 2008 from which it has never recovered—despite a economic recovery after 2013. This article centred around this problem, contributing to the debate on the consequences of economic performance on citizens’ trust in representative institutions and the judiciary when compared with the effect of two relevant factors, corruption and evaluations of the political process, which we found to be highly relevant for the Spanish case as well.

The preceding analysis is based, firstly, on a pooled dataset from the Spanish Eurobarometer surveys between 1997 and 2019 and, secondly, on an individual-level panel data set collected during 2015 in Spain. Our focus with the first dataset was to perform a test of the three relevant factors at the societal-level, allowing us to unpack their relative importance on the evolution of political trust in Spain over time. The second analysis explained changes of political trust “within” respondents over time, thus focusing on changes in individuals’ perceptions, evaluations and personal situations.

The data assembled in this study strongly suggests that the Great Recession has indeed been responsible for the strong decline in political trust in Spain. It has been one of the worst affected countries of the financial and public debt crisis and its social consequences were particularly harsh. A second, more indirect explanation can be found in the perceived inability of Spanish politicians have been adequately responsive while they were coping with the crisis, likely contributing to the breakdown of the two-party system in Spain (Orriols and Cordero, 2016). Yet, Spain has also suffered a series of major corruption incidents in the 2010s—involving high ranked members from different political parties across the ideological spectrum—and these scandals have likely also undermined people’s belief in the probity of political elites. We believe that these latter two explanations, perceived shortcomings of political responsiveness and salience of corruption have contributed to the suppression of trust in representative institutions after 2012—even after the economy gradually started to recover. The effect of perceived corruption on political trust was particularly salient for the judiciary, showing how political trust is also object-dependent.

Low levels of political trust constitute an important problem for many contemporary democracies as well. An often expressed hope is that political trust should recover as soon as economic and social problems are mitigated or resolved. Hooghe and Okolikj (2020) show that this appears to be the case for Europe at large and that respondents across Europe have reacted positively to economic recovery, restoring trust to pre-crisis levels. However, this finding does not reflect the situation in Spain, where political trust remains considerably low. Here, the crisis might have served as a “performance test” for the Spanish democracy, the perceived failure of which led to a decline in peoples’ evaluations of the responsiveness of the political system, which, combined with a series of political corruption incidents hindered the recovery of trust in representative institutions. This combination has likely also paved the way to the proliferation of populist and right-wing parties in Spain that often appeal to their greater moral integrity and transparency. In our opinion, we might also obtain similar results when this model is applied to other South-European countries, which are facing similar problems of corruption and deficits in the democratic process such as Greece or Italy who have also failed to restore political trust to pre-crisis levels.

This observation indicates the possibility that economic performance and the quality of governance/public administration might constitute necessary but not sufficient conditions for a trusting citizenry. In the face of prolonged economic malaise, political trust might erode, no matter the state of their democracy. Conversely, even with a strong economy, if countries fail to be responsive to citizens’ demands, they could be expected to lose confidence in their (democratic) political system (Torcal, 2014; Linde and Peters, 2020). Or, is it only during an economic crisis that people consider these aspects, and does their tolerance for such aspects increase if the economy is booming? One avenue for future research could be to assess the relative weight of each factor and investigate the conditions under which a particular factor matters more.

Our commented Stata do-files are deposited in the datorium under: https://doi.org/10.7802/2274. Here, we also provided the pooled Eurobarometer dataset, with the variables used in the analysis and the robustness checks. The CIUPANEL dataset is available by request at: https://www.upf.edu/web/survey/research-projects-data.

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

The research study was supported by the Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad, Programa Estatal de Fomento de la Investigación Científica y Técnica de Excelencia—Subprograma Estatal de Generación de Conocimiento, under grant number CSO 2016-79772-P (2016–2020) and by the ICREA-ACADEMIA Intense Research Award.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2021.676672/full#supplementary-material

1See: https://ec.europa.eu/commfrontoffice/publicopinion/index.cfm/Chart/getChart/themeKy/18/groupKy/85 (retrieved 2021/03/10).

2Data accessed at http://www.cis.es/cis/opencms/ES/NoticiasNovedades/InfoCIS/2014/PlataformaOnLineBancodeDatos.html.

3These data are from the series of the Center of Sociological Research (CIS), studies numbers 2384, 2757, 2807, 2860 and 3028.

4This is the acromyn for “Crisis and challenges in Spain: attitudes and political behaviour during the economic and the political representation crisis” (Torcal et al., 2016).

5Data accessed at http://www.gesis.org/eurobarometer-data-service/search-data-access/data-access.

6When considering the respective time trend in Figure 2, we can see that political corruption has never been a major concern until 2012, when the awareness of this issue has increased after a series of corruption incidents. Therefore, we can connect the variation in this indicator to the public debate at the time. Furthermore, this indicator remained essentially unchanged even in the years of the greatest losses in political trust between 2008 and 2012.

Águeda, P. (2014). Anticorrupción investiga el gasto de 15 millones con tarjetas en “negro” de la cúpula de Caja Madrid. Eldiario.es. Available at: http://www.eldiario.es/politica/Anticorrupcion-investiga-tarjetas-Caja-Madrid_0_309019381.html (Accessed October 1).

Alesina, A., and Wacziarg, R. (2000). “The Economics of Civic Trust,” in Disaffected Democracies. What’s Troubling the Trilateral Countries? Editors S. J. Pharr, and R. D. Putnam (Princeton: Princeton University Press), 147–170.

Anderson, C. J., and Tverdova, Y. V. (2003). Corruption, Political Allegiances, and Attitudes Toward Government in Contemporary Democracies. Am. J. Pol. Sci. 47, 91–109. doi:10.1111/1540-5907.00007

Ariely, G., and Uslaner, E. M. (2017). Corruption, Fairness, and Inequality. Int. Pol. Sci. Rev. 38, 349–362. doi:10.1177/0192512116641091

Bauhr, M., and Grimes, M. (2014). Indignation or Resignation: The Implications of Transparency for Societal Accountability. Governance 27, 291–320. doi:10.1111/gove.12033

Blais, André., Morin-Chassé, A., and Singh, S. P. (2015). Election Outcomes, Legislative Representation, and Satisfaction with Democracy. Party Pol. 23, 85–95.

Bosch, A., and Durán, I. M. (2019). How Does Economic Crisis Impel Emerging Parties on the Road to Elections? The Case of the Spanish Podemos and Ciudadanos. Party Polit. 25, 257–267. doi:10.1177/1354068817710223

Brooks, C., and Manza, J. (2007). Why Welfare States Persist: The Importance of Public Opinion in Democracies. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Catterberg, G., and Moreno, A. (2006). The Individual Bases of Political Trust: Trends in New and Established Democracies. Int. J. of Pub. Op. Res. 18 (1), 31–48. doi:10.1093/ijpor/edh081

Chang, E. C. (2013). A Comparative Analysis of How Corruption Erodes Institutional Trust. Taiwan. J. Democracy 9 (1), 73–92.

Chang, E. C. C., and Chu, Y.-H. (2006). Corruption and Trust: Exceptionalism in Asian Democracies? J. Polit. 68, 259–271. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2508.2006.00404.x

Citrin, J., and Luks, S. (2001). “Political Trust Revisited: Déjà Vu All over Again?,” in What is it about Government that Americans Dislike? Editors J. R. Hibbing, and E. Theiss-Moore (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press), 9–27.

Citrin, J., and Stoker, L. (2018). Political Trust in a Cynical Age. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 21, 49–70. doi:10.1146/annurev-polisci-050316-092550

Clarke, H. D., Dutt, N., and Kornberg, A. (1993). The Political Economy of Attitudes toward Polity and Society in Western Democracies. J. Pol. 55, 998–1021.

Dotti Sani, G. M., and Magistro, B. (2016). Increasingly Unequal? The Economic Crisis, Social Inequalities and Trust in the European Parliament in 20 European Countries. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 55, 246–264. doi:10.1111/1475-6765.12126

Dustmann, C., Eichengreen, B., Otten, S., Sapir, A., Tabellini, G., and Zoega, G. (2017). Europe’s Trust Deficit. London: CEPR Press.

Ellinas, A. A., and Lamprianou, I. (2014). Political Trust in Extremis. Comp. Polit. 46, 231–250. doi:10.5129/001041514809387342

Esaiasson, P. (2011). Electoral Losers Revisited - How Citizens React to Defeat at the Ballot Box. Elect. Stud. 30, 102–113. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2010.09.009

Foster, C., and Frieden, J. (2017). Crisis of Trust: Socio-Economic Determinants of Europeans’ Confidence in Government. Eur. Union Polit. 18, 511–535. doi:10.1177/1465116517723499

Gallie, D. (1994). Are the Unemployed an Underclass? Some Evidence from the Social Change and Economic Life Initiative. Sociology 28, 737–757. doi:10.1177/0038038594028003006

Grimes, M. (2006). Organizing Consent: The Role of Procedural Fairness in Political Trust and Compliance. Eur. J. Polit. Res 45, 285–315. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6765.2006.00299.x

Hakhverdian, A., and Mayne, Q. (2012). Institutional Trust, Education, and Corruption: A Micro-Macro Interactive Approach. J. Polit. 74, 739–750. doi:10.1017/S0022381612000412

Harring, N. (2013). Understanding the Effects of Corruption and Political Trust on Willingness to Make Economic Sacrifices for Environmental protection in a Cross-National Perspective. Soc. Sci. Q. 94, 660–671. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6237.2012.00904.x

Harteveld, E., Meer, T. v. d., and Vries, C. E. D. (2013). In Europe we Trust? Exploring Three Logics of Trust in the European Union. Eur. Union Polit. 14, 542–565. doi:10.1177/1465116513491018

Hetherington, M. J., and Rudolph, T. J. (2015). Why Washington Won’t Work. Polarization, Political Trust and the Governing Crisis. Chicago: The Chicago University Press. doi:10.7208/chicago/9780226299358.001.0001

Hetherington, M. J. (1998). The Effect of Political Trust on the Presidential Vote, 1986-96. Am. Pol. Sci. Rev. 93, 311–326. doi:10.2307/2585398

Hibbing, J., R., and Theiss-Morse, E. (2002). Stealth Democracy: Americans' Beliefs about How Government Should Work. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hibbing, J. R., and Theiss-Morse, E. (1995). Congress as Public Enemy: Public Attitudes toward American Political Institutions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hooghe, M., and Okolikj, M. (2020). The Long-Term Effects of the Economic Crisis on Political Trust in Europe: Is There a Negativity Bias in the Relation between Economic Performance and Political Support? Comp. Eur. Polit. 18, 879–898. doi:10.1057/s41295-020-00214-5

Kumlin, S., and Haugsgjerd, A. (2017). “The Welfare State and Political Trust: Bringing Performance Back in,” in Handbook of Political Trust. Editors S. Zmerli, and T. W. G. Van der Meer (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar), 418–439.

Kumlin, S. (2004). The Personal and the Political: How Personal Welfare State Experiences Affect Political Trust and Ideology. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Linde, J., and Peters, Y. (2020). Responsiveness, Support, and Responsibility: How Democratic Responsiveness Facilitates Responsible Government. Party Polit. 26 (3), 291–304. doi:10.1177/1354068818763986

Linde, J. (2012). Why Feed the Hand That Bites You? Perceptions of Procedural Fairness and System Support in post-communist Democracies. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 51 (3), 410–434. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6765.2011.02005.x

Listhaug, O. (2006). “Political Disaffection and Political Performance. Norway, 1957-2001,” in Political Disaffection in Contemporary Democracies. Social Capital, Institutions, and Politics. Editors M. Torcal, and J. R. Montero (London: Routledge), 213–243.

Listhaug, O., and Wiberg, M. (1995). Confidence in Political and Private Institutions, in Citizens and the State. Editors H.-D. Klingemann, and D. Fuchs (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 298–322.

Martini, S., and Quaranta, M. (2020). Citizens and Democracy in Europe: Contexts, Changes and Political Support. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan.

Miller, A., and Listhaug, O. (1999). “Political Performance and Institutional Trust,” in Political Performance and Institutional Trust in Critical Citizens: Global Support for Democratic Government. Editor P. Norris (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 204–216.

Mishler, W., and Rose, R. (2001). What Are the Origins of Political Trust? Comp. Polit. Stud. 34, 30–62. doi:10.1177/0010414001034001002

Montero, J. R., Gunther, R., and Torcal, M. (1997). Democracy in Spain: Legitimacy, Discontent, and Disaffection. St Comp. Int. Dev. 32, 124–160. doi:10.1007/BF02687334

Mughan, A., and Lacy, D. (2002). Economic Performance, Job Insecurity and Electoral Choice. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 32, 513–533. doi:10.1017/S0007123402000212

Newton, K. (2007). “Social Political Trust,” in The Oxford Handbook of Political Behavior. Editors R. J. Dalton, and H.-D. Klingemann (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press), 342–361.

Newton, K., and Norris, P. (2000). “THREE. Confidence in Public Institutions: Faith, Culture, or Performance?,” in Disaffected Democracies. What’s Troubling the Trilateral Countries? Editors S. J. Pharr, and R. D. Putnam (Princeton: Princeton University Press), 52–73.

Norris, P. (2011). Democratic Deficit. Critical Citizens Revisited. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Offe, K. (2006). “Political Disaffection as an Outcome of Institutional Practices? Some post Tocquevillean Speculations,” in Political Disaffection in Contemporary Democracies. Social Capital, Institutions, and Politics. Editors M. Torcal, and J. R. Montero (London: Routledge), 23–45.

Orriols, L., and Cordero, G. (2016). The Breakdown of the Spanish Two-Party System: the Upsurge of Podemos and Ciudadanos in the 2015 General Election. South Eur. Soc. Polit. 21 (4), 469–492. doi:10.1080/13608746.2016.1198454

Persson, T., Parker, C. F., and Widmalm, S. (2017). Social Trust, Impartial Administration and Public Confidence in EU Crisis Management Institutions. Public Admin 95, 97–114. doi:10.1111/padm.12295

Pharr, S. J. (2000). “EIGHT. Officials' Misconduct and Public Distrust: Japan and the Trilateral Democracies,” in Disaffected Democracies. What’s Troubling the Trilateral Countries? Editor S. J. Pharry, and R. D. Putnam (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press), 173–201.

Pharr, S. J., Putnam, R. D., and Dalton, R. J. (2000). A Quarter-century of Declining Confidence. J. Democracy 11, 5–25. doi:10.1353/jod.2000.0043

Polavieja, J. (2013). “Economic Crisis, Political Legitimacy, and Social Cohesion,” in Economic Crisis, Quality of Work and Social Integration: The European Experience. Editor D. Gallie (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press), 256–278.

Porta, D. d. (2000). “NINE. Social Capital, Beliefs in Government, and Political Corruption,” in Social Capital, Beliefs in Government, and Political Corruption in Disaffected Democracies: What’s Troubling the Trilateral Countries? Editors S. J. Pharr, and R. D. Putnam (Princeton: Princeton University Press), 202–228.

Ramiro, L., and Gomez, R. (2017). Radical-left Populism during the Great Recession: Podemos and its Competition with the Established Radical Left. Polit. Stud. 65, 108–126. doi:10.1177/0032321716647400

Revilla, M., Saris, W., Loewe, G., and Ochoa, C. (2015). Can a Non-probabilistic Online Panel Achieve Question Quality Similar to that of the European Social Survey? Int. J. Market Res. 57, 395–412. doi:10.2501/IJMR-2015-034

Rothstein, B. (2021). “Auditing, Trust, and the Social Contract,” in Controlling Corruption. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 112–131.

Rothstein, B. (2009). Creating Political Legitimacy. Am. Behav. Scientist 53, 311–330. doi:10.1177/0002764209338795

Rothstein, B. (2003). Social Capital, Economic Growth and Quality of Government: The Causal Mechanism. New Polit. Economy 8 (1), 49–71. doi:10.1080/1356346032000078723

Rothstein, B., and Stolle, D. (2008). The State and Social Capital: an Institutional Theory of Generalized Trust. Comp. Polit. 40, 441–459. doi:10.5129/001041508X12911362383354

Rothstein, B., and Uslaner, E. M. (2005). All for All: Equality, Corruption, and Social Trust. World Pol. 58, 41–72. doi:10.1353/wp.2006.0022

Ruelens, A., Meuleman, B., and Nicaise, I. (2018). Examining Macroeconomic Determinants of Trust in Parliament: A Dynamic Multilevel Framework. Soc. Sci. Res. 75, 142–153. doi:10.1016/j.ssresearch.2018.05.004

Scharpf, F. W. (1999). Governing in Europe: Effective and Democratic? Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Torcal, M. (2017). “Political Trust in Western and Southern Europe,” in Handbook on Political Trust. Editors S. Zmerli, and T. W. Van der Meer (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing), 418–439.

Torcal, M., and Christmann, P. (2020). “Political Culture in Spain in the Twenty-First century,” in Symptoms of a Crisis of Representation in the Oxford Handbook of Spanish Politics. Editor D. I Muro eLago (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 313–330. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198826934.013.19

Torcal, M., and Lago, I. (2007). The 2006 Regional Election in Catalonia: Exit, Voice, and Electoral Market Failures. South. Eur. Soc. Polit. 12 (2), 221–235.

Torcal, M., Martini, S., and Serani, D. (2016). Crisis and Challenges in Spain: Attitudes and Political Behavior during the Economic and the Political Representation Crisis (CIUPANEL) (Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness) (CSO 2013-. 2014-2016, PI: Mariano Torcal, 47071-R). Available at: https://www.upf.edu/web/survey/research-projects-data.

Torcal, M. (2014). The Decline of Political Trust in Spain and Portugal. Am. Behav. Scientist 58, 1542–1567. doi:10.1177/0002764214534662

Uslaner, E. M. (2011). “Corruption, the Inequality Trap, and Trust in Government,” in Political Trust. Why Context Matters. Editors S. Zmerli, and M. Hooghe (Colchester, United Kingdom: ECPR Press), 141–162.

Uslaner, E. M. (2017). “Political Trust, Corruption, and Inequality,” in Handbook of Political Trust. Editors S. Zmerli, and T. W. Van der Meer (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar), 302–315.

Uslaner, E. M. (2002). The Moral Foundations of Trust. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

Van der Meer, T. W. G. (2017). “Democratic Input, Macroeconomic Outut and Political Trust,” in Handbook of Political Trust. Editors S. Zmerli, and T. W. G. Van der Meer (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar), 270–284.

Van der Meer, T., and Hakhverdian, A. (2017). Political Trust as the Evaluation of Process and Performance: A Cross-National Study of 42 European Countries. Polit. Stud. 65, 81–102. doi:10.1177/0032321715607514

Van der Meer, T. (2010). In What We Trust? A Multi-Level Study Into Trust in Parliament as an Evaluation of State Characteristics. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 76, 517–536. doi:10.1177/0020852310372450

Van Erkel, P. F. A., and Van Der Meer, T. W. G. (2016). Macroeconomic Performance, Political Trust and the Great Recession: A Multilevel Analysis of the Effects of Within-Country Fluctuations in Macroeconomic Performance on Political Trust in 15 EU Countries, 1999-2011. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 55, 177–197. doi:10.1111/1475-6765.12115

Wang, C.-H. (2016). Government Performance, Corruption, and Political Trust in East Asia. Soc. Sci. Q. 97, 211–231. doi:10.1111/ssqu.12223

Keywords: political trust, corruption, political responsiveness, political process, economic performance, Spain

Citation: Torcal M and Christmann P (2021) Responsiveness, Performance and Corruption: Reasons for the Decline of Political Trust. Front. Polit. Sci. 3:676672. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2021.676672

Received: 05 March 2021; Accepted: 05 July 2021;

Published: 22 July 2021.

Edited by:

Jennifer Rhian Gaskell, University of Southampton, United KingdomReviewed by:

Lisanne De Blok, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, NetherlandsCopyright © 2021 Torcal and Christmann. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mariano Torcal, bWFyaWFuby50b3JjYWxAdXBmLmVkdQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.