- 1Department of Political Science, McGill University, Montreal, QC, Canada

- 2Department of Political Science, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, Netherlands

This research examines the influence of political candidates’ personality dispositions and constituency characteristics on their assessments of the needs of immigrants and religious minorities. Previous research, drawing on data from citizens, links personality differences to attitudes toward diversity and support for minority communities. Extending this research to candidates during an ongoing election campaign, this study examines the interaction between constituency diversity and politicians’ intrinsic motivations to recognize the interests of immigrants and religious minorities. Using data from a unique candidate survey during the 2018 municipal elections in two large Canadian provinces (N = 1,073), results show that personality traits provide an intrinsic motivation, independent of candidates’ descriptive characteristics or the level of diversity in their constituency, to recognize a higher level of support needed by members of these diverse communities. More agreeable candidates are consistently more likely to acknowledge that more should be done for immigrants and religious minorities whereas the negative influence of conscientiousness on minority recognition is suppressed in highly diverse constituencies. The results extend previous research on personality and intergroup dynamics and situate candidates’ recognition of the needs of others as an important antecedent to political representation.

Introduction

In Canada, recognition and support for the needs of ethnic and cultural minorities is a cornerstone of the country’s multiculturalism policy. Although Canadians’ commitment to diversity and multiculturalism has traditionally been strong (Berry and Kalin, 1995; Soroka and Roberton, 2010), support for immigration has been less stable (Wilkes and Corrigall-Brown, 2011; Harell et al., 2012; Banting and Soroka, 2020). Especially in more recent years, the issue of religious accommodation has become more salient in the country, drawing increased attention to the needs and practices of religious minority communities.

Much research seeks to explain individuals’ attitudes toward immigrants and immigration (for reviews, see Hainmueller and Hopkins, 2014; Esses, 2021) and, more recently, public opinion toward religious symbols (Bilodeau et al., 2018; Ferland, 2018; Turgeon et al., 2019). While the attitudes of the general public are of great interest, demographic shifts brought on by migration are spurring significant changes in the composition of the electorate, posing new questions about what motivates politicians to recognize the needs of immigrants and religious minorities. The extent to which candidates are willing to recognize the needs of minority group members is an important consideration when assessing potential shortcomings in political representation.

Politicians’ motivations to speak out for minority interests are affected by intrinsic and extrinsic factors. Politicians’ support for minorities is associated with shared descriptive characteristics and external constituency considerations in motivating their recognition of the needs of others. Research on descriptive representation underlines the importance of shared experiences in representing minority interests, yet in constituencies characterized by higher levels of diversity, politicians are shown to be more likely to speak up for minority interests even when they themselves do not come from minority backgrounds (Bird, 2011; Black, 2011; Saalfeld and Bischof, 2013; Sobolewska et al, 2018). Apart from an affinity induced by shared experiences as members of under-represented communities, intra-individual differences in whether or not political actors show solidarity with minority groups have received less attention in situations where external electoral incentives vary.

Political candidates are faced with strategic electoral considerations and are incentivized to attend to minority interests in highly diverse electoral districts. On the campaign trail, political candidates have a rational incentive to be attuned to issues affecting their constituents and, if elected, legislators are expected to serve, in various ways, as representatives, acting on behalf of constituents by giving voice to the issues that affect them (Pitkin, 1967). Yet, despite these strong extrinsic motives to attend to minority interests, electoral incentives do not always cause political actors to offer their support to minority groups (Dinesen et al., 2021). Instead, politicians’ pre-existing attitudes and beliefs influence the positions they take on policy issues and this “psychological baggage” that candidates bring with them when they get involved in politics may divert their attention to the needs of some groups over others (Butler et al., 2011; Butler, 2014).

The present research is intended to advance insight into the personal motives of political candidates to express solidarity with minority groups. We investigate the extent to which political candidates’ personality traits offer an intrinsic motivation to support the needs of diverse groups of citizens independent of the role of shared experience brought on by common background characteristics or external considerations about the constituencies candidates seek to represent. We draw on data from a unique survey involving a large non-probability sample of political candidates (N = 1,073) collected during the 2018 municipal elections in two large Canadian provinces. We supplement this data with census records from Statistics Canada on the level of diversity in candidates’ municipalities. Together, the data illustrate the nuanced way intrinsic motivations and constituency considerations interact to shape politicians’ responsiveness to the needs of ethnocultural and religious minorities.

Personality and Support for Ethnic and Cultural Minorities

Personality is a broad, multidimensional concept, referring to foundational individual differences that emerge through human development reflecting principal differences between people. Personality psychology has increasingly become attractive to political scientists interested in explaining individual-level variation in political attitudes and behavior (Mondak, 2010; Gerber et al., 2011; Blais and Pruysers, 2017). Personality research has also fueled a growing scholarly interest into the extent that politicians’ own dispositions impact their political behavior (Nai and Martinez i Coma, 2019; Nai and Maier, 2020; Scott and Medeiros, 2020). Moreover, personality is relevant to the study of group-specific attitudes and opinions. Often phrased as self-assessments, these questionnaires are measured without reference to any political content yet show consistent relationships with political orientations (Sibley and Duckitt, 2008; Gerber et al., 2010). Hence, personality differences are predictive of our propensity to like and dislike others, making it a relevant variable in the study of support for minority interests.

The most widely used framework for assessing personality is the five-factor model, the so-called “Big Five,” emphasizing five dispositional traits that capture a substantial degree of variation in individual differences (see John and Srivastava, 1999). These traits include extraversion, characterized by assertiveness and high energy; agreeableness, a tendency to be sympathetic and trustful toward others; conscientiousness, a preference for order, stability and self-discipline; openness to experience, reflective of creativity and open-mindedness; and, emotional stability, the opposite of neuroticism, capturing a tendency to be avoid feeling anxious, easily upset and prone to negative emotions.

Personality psychologists have examined these and other character traits from various lenses. One criticism of the five-factor model is that these dimensions do not fully capture the breadth of variance in human personality. Further models have sought to expand beyond the five-factor approach by introducing a distinctive sixth dimension, honesty-humility, tied to fairness and altruism (Ashton and Lee, 2007), or by elaborating on the negative dimensions of human personality (i.e., the “Dark Triad”; see Paulhus and Williams, 2002). Nonetheless, the “Big Five” captures substantial variability in individual differences and remains an influential framework in the study of a range of intergroup attitudes, political values, and policy preferences (Gerber et al., 2010; Mondak, 2010). This framework is particularly useful in research involving political actors due to the availability of very brief measures facilitating research when participants’ time constraints are of great importance.

Personality characteristics are worthy of scrutiny in understanding what incentivizes politicians to recognize the needs of minorities because of their well-known association with policy preferences, racial attitudes, and prejudice among citizens. Individual differences in agreeableness, openness, and conscientiousness have been demonstrated to correlate with citizens’ policy preferences toward issues affecting immigrants, refugees, and religious minorities (Ackermann and Ackermann, 2015; Dinesen et al., 2016; Ziller and Berning, 2019; Pruysers, 2020). While the relationship between personality and attitudes toward diversity has been established, research on the personality of politicians and their influence on the solidarity candidates express toward members of minority communities remains under-studied.

Rather than exerting a deterministic influence over social and political attitudes, personality traits interact with situational forces to shape how individuals respond to various issues. Generally, open-minded individuals tend to favor progressive social policies and are more likely to be inclusive of cultural diversity, whereas individuals scoring higher on measures of conscientiousness tend to favor conformity and disapprove of challenges to the status quo (Gerber et al., 2011). In a meta-analysis of nearly 72,000 individuals across 73 studies (Sibley et al., 2012), weak associations between political conservatism and the personality dimensions of openness and conscientiousness are found to be moderated by situational variables such as threat perceptions, illustrating the joint influence of individual and situational factors in predicting political preferences. While these personality traits are associated with support for different social and economic policies (Gerber et al., 2010), cross-national comparative research reveals significant variation in the relationship between personality traits and policy preferences in different countries, again pointing to the importance of taking context into account when studying the link between personality and politics (Fatke, 2017).

Beyond one’s political orientations, correlational research examining the association between personality and generalized prejudice report weak associations with openness and conscientiousness, and much stronger associations between agreeableness and outgroup attitudes. The research suggests these aspects of personality are most closely related to evaluations toward an assortment of different groups (Ekehammar and Akrami, 2003; Sibley and Duckitt, 2008; Crawford and Brandt, 2019). Agreeableness is thought to be a particularly relevant personality trait in predicting intergroup attitudes and evaluations. Compared to openness and conscientiousness, which are tied to apprehensions toward ideologically dissimilar outgroups, agreeableness is linked to evaluations of a wide assortment of groups and, “may therefore be the single trait within the Big Five personality structure that determines people’s general orientation toward other people” (Crawford and Brandt, 2019, p. 1464).

In light of the generally consistent relationships between personality traits, political preferences and outgroup attitudes, it is of no surprise that these traits have been found to be predictive of increased recognition and support for the needs of immigrants, refugees, and religious minorities. Concerning attitudes toward immigrants and immigration policy, researchers find more supportive attitudes toward immigrants and immigration among more agreeable and less conscientious individuals (Gallago and Pardos-Prado, 2014; Dinesen et al., 2016). Consistent with these findings, more open-minded, agreeable, and less conscientious individuals are also found to be more likely to support extending voting rights to immigrants and more willing to support the religious rights of Muslims (Ziller and Berning, 2019).

Such findings are supported by further research on the negative relationship between prejudice toward migrants (Talay and De Coninck, 2020). Pruysers (2020) finds no direct association between agreeableness and support for refugees in Canada; rather conscientiousness and openness to experience are once again found to be associated with lower or higher support, respectively, for refugees. Ackermann and Ackermann (2015) also find greater support for equal opportunities for immigrants among more agreeable, open-minded, and less conscientious individuals. Their findings once again underline the importance of considering individual differences alongside situational factors because, as their data show, the negative relationship between conscientiousness and support for equal opportunity of immigrants is attenuated by perceptions of increased ethnic diversity in respondents’ neighbourhoods. Further research also shows that varying situational considerations about the skill level of migrants may alter the relationship between conscientiousness and immigration attitudes (Dinesen et al., 2016).

Some personality traits provide a strong motivational incentive to express solidarity with ethnic and cultural minorities but the influences of personality on social and political issues appear to be expressed differently from one situation to the next. Previous research shows how these core individual differences have robust relationships to political orientations and outgroup attitudes (Gerber et al., 2011; Sibley et al., 2012). More agreeable individuals tend to show increased empathy and a heightened concern for the well-being of others (Graziano et al., 2007). Furthermore, conscientiousness and openness to experience are consistently linked with higher and lower levels, respectively, of political conservatism, social dominance orientation, and right-wing authoritarianism, key social and political values which underpin beliefs about intergroup competition and conformity (Ekehammer et al., 2004; Sibley and Duckitt, 2008; Gerber et al., 2011). Based on this literature, we anticipate that agreeableness, openness to experience, and conscientiousness are especially important dimensions of personality, motivating candidates to recognize the increased needs of different minority groups.

Politicians’ Motives to Support Minority Interests

Research on representation point to a number of different ways in which politicians might act on behalf of constituents (Pitkin, 1967; Mansbridge, 2003). Political candidates may advocate on behalf of minority interests by drawing attention to the needs of others and speaking out on the issues important to members of the constituencies they represent. While shared experiences and the background of individual legislators are important for the representation of minority interests (Bird, 2011; Black, 2011; Sobolewska et al., 2018), research on legislative behavior in Canada and other Western democracies shows that a small number of politicians still advocate on behalf of the needs of others even when they themselves do not share in a common ethnic or cultural group membership with those they represent.

A critical extrinsic factor that motivates politicians’ representation of minority issues is the demographic make-up of their constituencies. In constituencies characterized by higher levels of diversity, politicians are known to speak up for minority interests at a level comparable to representatives from a minority background. Examining parliamentary questions in the United Kingdom, Saalfeld and Bischof (2013) show that representatives from a minority background were more likely to raise ethnic issues but that all MPs, regardless of ethnic background, engaged more with such issues as the ethnic make-up of their own constituencies increased. A similar pattern is also found in the Canadian House of Commons. Analyses of the issues raised during Parliamentary debates finds that Canadian MPs of visible minority background consistently raise ethnic-related issues regardless of the level of diversity in their districts (Bird, 2011; Black, 2011). However, as this work also shows, non-minority MPs representing highly diverse constituencies raise issues pertaining to citizenship and immigration, discrimination, and cultural diversity at comparable levels as minority MPs. They are also significantly more likely to raise such issues when compared to legislators from non-minority backgrounds representing less diverse ridings.

In a field experiment with legislators from the United States, Broockman (2013) e-mailed politicians an inquiry from a citizen with a typically Black-sounding name and measured reply rates to the question. All legislators, Blacks as well as non-Blacks, tended ignore the inquiry to a much greater extent if the letter did not come from a citizen residing in their district. Black legislators, however, were significantly more likely to respond to the inquiry regardless of whether or not the letter came from a constituent, suggesting intrinsic motivations outside electoral politics may guide politicians’ representation of minority interests. In a recent study, Danish local incumbent politicians were found to be less responsive to requests for information on where to vote in an upcoming election from an individual from a minority (i.e., Middle Eastern/North African) background (Dinesen et al., 2021). Whether or not the letter writer signaled their intention to vote for the politician did not significantly increase politicians’ responsiveness. Once again, electoral incentives appear ineffective at mitigating the role of individual differences in shaping whether or not politicians provide assistance to members of certain minority groups. Electoral incentives may not always outweigh individual predispositions to be (non)responsive to minorities.

In light of the strong influence that constituency diversity plays on politicians’ support for minorities (Bird, 2011; Saalfeld and Bischof, 2013; Sobolewska et al., 2018), it is worthwhile to compare candidates’ recognition of the needs of minorities, examining whether the relationship between candidates’ personality traits, specifically, their agreeableness, openness to experience, and conscientiousness, and their recognition of the needs of others from diverse minority groups are moderated by the level of diversity in a locality.

Research Design

To advance our understanding of what motivates politicians to recognize minority interests, our research design explores municipal-level considerations alongside individual difference variables that are expected to motivate solidarity with the needs of minorities. The study focuses on a so far overlooked, yet important, intrinsic motivation: the role of personality characteristics across contexts where constituency considerations vary. Beyond constituency considerations and shared experiences due to ethnic affinity, what role do politicians’ personality traits have in their willingness to recognize the needs of minorities?

In light of the evidence tying personality to diversity attitudes, we hypothesize that candidates’ personality traits have a direct association with their recognition of the need to do more for immigrants and religious minorities (Hypothesis 1). Specifically, we hypothesize that more agreeable, open-minded, and less conscientious candidates are most supportive of the need to do more for group members. Furthermore, research on politicians’ substantive representation of minority interests point to constituency characteristics as extrinsic factors motivating politicians to recognize the needs of ethnocultural minorities. Independent of candidates’ personality and other background characteristics, we expect candidates contesting elections in municipalities characterized by a higher proportion of minority residents to be significantly more likely to acknowledge the needs of minorities (Hypothesis 2). We also believe that neither intrinsic nor extrinsic motivations to recognize the needs of minorities operate in isolation. Because of the positive association between open-mindedness and, especially, agreeableness, and diversity attitudes, together with the electoral incentive candidates have to attend to minority issues in more diverse constituencies, we expect the relationship between openness to experience and agreeableness to be strengthened in more diverse constituencies (Hypothesis 3); whereas the negative association between conscientiousness and support for minorities is attenuated in these municipalities (Hypothesis 4).

Methodology

To answer our research question and test the hypotheses that were put forth, we utilise data drawn from a large survey of municipal candidates in two large Canadian provinces, Ontario and British Columbia, collected during the 2018 municipal elections. A non-probability sample of municipal candidates was constructed by creating a list of all municipal candidates who included e-mail addresses on official candidate registries maintained by electoral authorities in both provinces. Because of the short time period of several weeks between the release of candidate lists and the election, practical limitations prevented us from recruiting candidates whose e-mails did not appear in these registries. Our sample, therefore, cannot be said to be representative of the entire slate of candidates.1 Given the brief measure of personality used in the study which measures each trait with two items (see below for details), we do not impute missing scores on these items opting to exclude respondents with incomplete questionnaires via listwise deletion.

Measures

Support for two minority groups was measured with two survey items asking respondents “how much do you think should be done” for immigrants and religious minorities. Respondents indicated their level of support on a five-point scale, with ordered categories ranging from “much more” to “much less,” with the mid-point of the scale labeled, “about the same.” Both measures were recoded into a three-category ordered variable measuring support for each group by collapsing together those indicating “much” or “somewhat” more should be done along with those indicating “much” or “somewhat” less should be done for immigrants and religious minorities.

Personality traits were measured using the ten-item personality inventory (TIPI; Gosling et al., 2003). The TIPI consists of ten statements anchored by opposing pairs of adjectives with two items tapping each personality trait in the five-factor model. Participants were instructed to indicate “how well the following pair of words describe you, even if one word describes you better than the other.” Self-rated adjectives for each of the five personality traits were as follows: openness: complex, open to new experiences and conventional, uncreative (reversed); conscientiousness: dependable, self-disciplined and disorganized, careless (reversed); extraversion: enthusiastic, extraverted and reserved, quiet (reversed); agreeableness: critical, quarrelsome (reversed) and sympathetic, warm; and, emotional stability: anxious, easily upset (reversed) and calm, emotionally stable. Participants were instructed to indicate the extent to which each adjective pair describe them on a scale from 1 (extremely poorly) to 7 (extremely well). As with any short instrument, there is a trade-off between the construct validity and the brevity of the measure. The necessity of such brief scales, however, is all the more important with research involving political candidates during an actual election campaign.

Appended to the survey data are several constituency-level measures derived from municipal data drawn from the 2016 Canadian census.2 The literature clearly points to the importance of local diversity; therefore, we utilise the proportion of visible minorities3 in candidates’ municipalities. Also, seeing as research has highlighted the conditional impact of unemployment on attitudes toward immigration (Palmer, 1996), we control for the proportion of unemployed residents in the candidates’ municipality. Furthermore, the level of urbanization of residence can impact attitudes toward immigration (Fennelly and Federico, 2008). We therefore use the population density (the number of persons per square kilometer) of candidates’ municipalities to control for this influence.

We also adjust for a series of individual-level controls. Kokkonen and Karlsson (2017) conduct one of the few studies that explores attitudes toward immigrants among politicians and find that gender, education, age, partisan affiliation, and foreign background are significant determinants of these attitudes. We thus adjust for candidates’ gender (female = 1) and post-secondary education (university educated = 1). Age is measured categorically, contrasting candidates ages 30–39, 40–49, 50–64, and 65 and older to the youngest group of respondents under 30 years of age. We use politicians’ self-assessed political orientation to adjust for their political predispositions. Specifically, we asked candidates, “in politics, people sometimes talk of left and right. Where would you place yourself on the scale below?” Candidates were presented with an 11-point scale ranging from 0 (Left) to 10 (right). As for the candidates’ political experience, we control for whether or not candidates are incumbents in the election as more experienced politicians may have different levels of contact with constituency members, increasing the chances that incumbent politicians in highly diverse constituencies hear more about the needs of their constituents. The election outcome, whether or not candidates were elected, as well as party affiliation, whether or not candidates ran under a local party affiliation, were also controlled for. Moreover, we measure whether or not candidates associate themselves with a typically white ethnic group or are of Indigenous or visible minority background. This variable was constructed from a survey item asking candidates to report their belonging to various ethnocultural groups. Candidates indicated they were of Asian or South Asian; Middle Eastern, Arab or West-Asian; Black; Latin American; Indigenous or from another minority background were categorized as non-White whereas those indicating they were of Canadian, European or Anglo-American heritage (including from the United States, Australia or New Zealand ancestry) were categorized as White.4

Participant Characteristics

The final dataset consists of 1,073 politicians from 153 municipalities across Ontario (n = 662; 61.7%) and from 122 municipalities across British Columbia (n = 411; 38.3%) returning completed questionnaires on all variables of interest. Just over one-third of the respondents identified as female (n = 363; 33.8%). Most respondents were over the age of 50 (n = 717; 66.8%), 22% of whom (n = 238) were 65 or older. The remaining respondents were between the ages of 40–49 (n = 201; 18.7%), 30 to 39 (n = 119; 11.1%), with a small number of respondents under the age of thirty (n = 36; 3.4%). About half the sample reported some post-secondary education (n = 550; 51.3%) while approximately 23 percent (n = 246) were incumbents in the election. Nearly all respondents were of non-visible minority background (n = 983; 92%) and most were native English speakers (n = 948; 88%). Descriptive statistics for the variables used in the analyses are presented in Supplementary Table A1.

In most provinces, Canadian municipal candidates do not run for office under a particular political affiliation, although a number of local political parties exist in certain municipalities in select Canadian provinces, such as Quebec and, important for our purposes, British Columbia. In Canadian municipal elections, these political parties are not attached to provincial or federal counterparts. In our sample of municipal candidates whose data is presented here, a very small number of candidates (n = 23), all from British Columbia, reported a party affiliation at the local level. Altogether, 453 respondents (42.2%) were elected in their district, with a significantly higher number of winners from British Columbia (n = 198; 48.2%) than Ontario (n = 255; 38.5%), χ2 (1) = 9.30, p = 0.002.

There were no significant interprovincial differences between age, gender, and incumbent status. Candidates from Ontario were somewhat more likely to have post-secondary education experience, χ2 (4) = 8.47, p = 0.004. Ontario candidates (Mean = 5.01, SD = 2.02) were more right-leaning than candidates from British Columbia (Mean = 4.55, SD = 1.96), t (891) = −3.68, p < 0.001, whereas candidates from British Columbia, on average, were running in more urban municipalities (Mean = 811.5 people/km2, SD = 1,202.05 people/km2) compared to respondents from Ontario (Mean = 668.3 people/km2, SD = 923.2 people/km2), t (706) = 2.07, p = 0.04. There were no significant differences with respect to the proportion of visible minority residents between participants from the two provinces, however the sub-sample of participants from British Columbia (Mean = 3.85%, SD = 1.49%) had a higher percentage of unemployed residents, on average, in their municipalities compared to respondents from Ontario (Mean = 3.53%, SD = 0.81), t (562) = 4.06, p < 0.001.5

Results

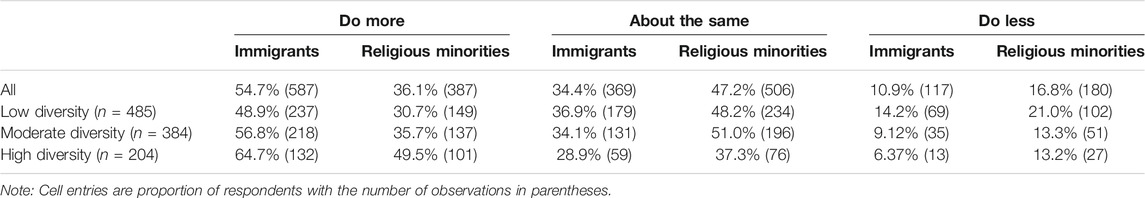

The distribution of candidates’ responsiveness to the level of support needed by immigrants and religious minorities is reported in Table 1. In general, candidates in the sample are more supportive of the need to do more for immigrants (54.7%) than religious minorities (36.1%). While most candidates agreed that more should be done for immigrants, respondents were more satisfied with the status quo level of support offered to religious minorities, with just under one-half of respondents (47.2%) supporting doing “about the same” as now. Although there were no significant differences detected in candidates’ recognition for the need to do more for immigrants between those identifying as belonging to a visible minority or Indigenous group compared to other candidates, χ2 (2) = 4.01, p = 0.13, a higher proportion of candidates from minority backgrounds recognized the need to do more for religious minorities than other candidates (52.2, χ2 (2) = 11.8, p = 0.003.

TABLE 1. Distribution of candidates’ responses to whether more or less should be done for immigrants and religious minorities by relative level of diversity (i.e., proportion of visible minorities) in candidates’ municipalities.

Variation in candidates’ assessments of the needs of immigrants and religious minorities are examined across constituencies with differing levels of visible minority residents (see Table 1). To facilitate an examination of the distribution of candidates’ support across municipalities with varying levels of diversity, candidates’ municipalities were trichotomized based on whether they resided in a municipality with relatively lower levels of diversity, below 5%, which approximately corresponds to the sample median (5.6%); a “moderate” level of diversity, defined here as between 5% and less than 20% visible minority residents; or, a “high” level of diversity, with municipalities reporting 20% or more visible minority residents. The results reveal a steady increase in the proportion of candidates signaling their support for the need to do more for immigrants, χ2 (4) = 19.61, p < 0.001, and religious minorities, χ2 (4) = 29.23, p < 0.001 as the level of diversity in their municipality increases. Nonetheless, even in highly diverse constituencies, support remains much higher for immigrants than for religious minorities.

These bivariate analyses provide preliminary insights into how municipal candidates’ recognition of the needs of immigrants and religious minorities varies as a function of the ethnocultural diversity of their constituencies. To rule out potential confounding variables, and also to test the primary research hypotheses that intrinsic influences rooted in candidates’ personality characteristics work in conjunction with contextual variation in constituency diversity to motivate candidates’ support for minorities, we turn our attention to a multivariate analysis.

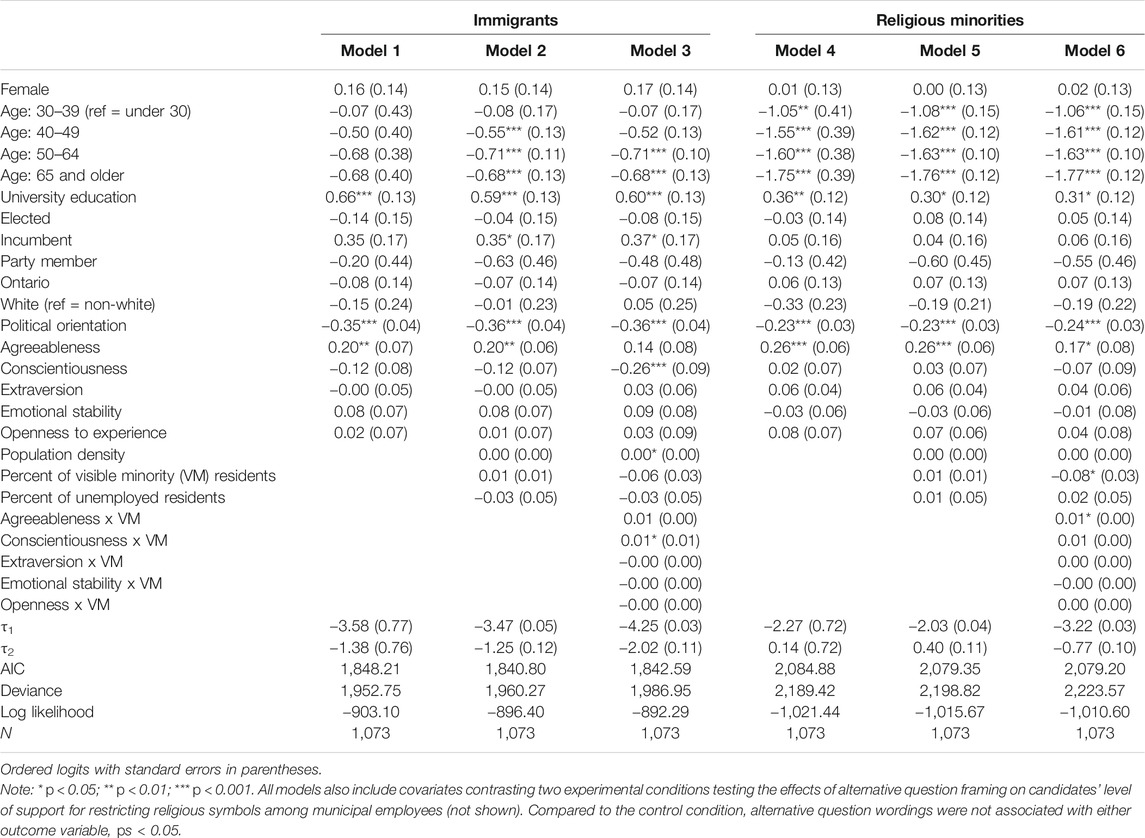

The primary results of the study are reported in Table 2, which presents a series of ordered logistic regression models predicting support for immigrants (models 1–3) and religious minorities (models 4–6).6 Models 1 and 4 present the associations between individual difference variables and politicians’ recognition of the level of support needed by immigrants and religious minorities, respectively, as measured on an ordered log-odds scale, holding constant other variables in the model. In models 2 and 5, these associations are re-estimated controlling for constituency characteristics including the percentage of visible minority and unemployed residents, along with the municipalities’ population density to control for the level of urbanization. These models provide tests of the direct effects of the hypothesized associations above. Finally, models 3 and 6 present tests of the predicted moderation effects between personality traits and constituency diversity.

TABLE 2. Results from ordinal logistic regression analyses predicting support for doing more for immigrants (Models 1–3) and religious minorities (Models 4–6) as a function of social background, personality traits, and constituency characteristics.

An examination of the distribution of candidates’ responses to the amount of support needed by immigrants and religious minorities show greater overall sympathies for the needs of immigrants than for religious minorities. Candidates’ overall support for both groups, however, is shaped by similar demographic variables. Older candidates, along with those who characterize their political orientation as more right-leaning, are less likely to support increased assistance to immigrants and religious minorities. These results are in line with those of Kokkonen and Karlsson (2017). A post-secondary education is also significantly positively associated with increased support for the interests of these minority groups. We find no evidence to suggest that male and female candidates differ in their recognition of the level of supports needed by immigrants and religious minorities.

To contextualize the relationship between these demographic variables and endorsing the need to do more for immigrants and religious minorities, we examine the changes in the proportional odds ratios associated with a unit shift in each predictor, using the coefficients in models 2 and 5. Candidates’ who place their political views to the right are 0.7 times less likely to recognize the need to do more for immigrants and 0.8 times less likely to recognize the needs of religious minorities. Compared to the youngest candidates in the sample under the age of thirty, the odds of a politician in the 50–64 age range endorsing the need to do more for immigrants drops by a factor of 0.49. This decline is less pronounced for religious minorities, decreasing by a factor of 0.20. Controlling for the other variables in the model, a candidate with a university education is 1.8 times more likely to endorse doing more for immigrants and 1.3 times more likely to endorse doing more for religious minorities. Incumbent politicians also acknowledge the increased needs of immigrants compared to non-incumbents by a factor of 1.4, but when it comes to recognizing the needs of religious minorities, incumbency is not found to be significantly associated with increased support.

Turning our attention to our primary hypotheses, the data provide mixed support for our anticipated associations between personality and candidates’ recognition of the level of support needed by immigrants and religious minorities. Of the five personality traits, only agreeableness demonstrated a significant, independent and direct association with both outcome measures. The hypothesized negative relationship between conscientiousness was only observed when assessing the perceived needs of immigrants, not religious minorities, and only when running for election in ridings with low levels of visible minority residents. Against our expectations, more open-minded candidates were not more likely to recognize the needs of immigrants or religious minorities, regardless of the level of diversity in one’s municipality. However, it may be that the inclusion of candidates’ self-assessed left-right political orientation is capturing some of the association between openness and conscientiousness and opinions on the needs of others, as these variables are known to be related to political orientations (Sibley et al., 2012).

To examine the influence controlling for candidates’ self-assessed political orientations has on the association between personality and candidates’ recognition of the need to do more for immigrants and religious minorities, the models presented in Table 2 are re-analysed, this time removing political orientation as a covariate. The results are reported in Supplementary Table A2 and reveal the expected associations between openness to experience and recognition of the increased needs of immigrants (b = 0.14, SE = 0.07, p < 0.05) and religious minorities (b = 0.14, SE = 0.06, p < 0.05), whereas conscientiousness is negatively associated with recognition of the needs of immigrants (b = −0.21, SE = 0.07, p < 0.01) but not religious minorities (b = −0.04, SE = 0.07, p > 0.05). The independent associations between agreeableness persist, relatively unchanged.

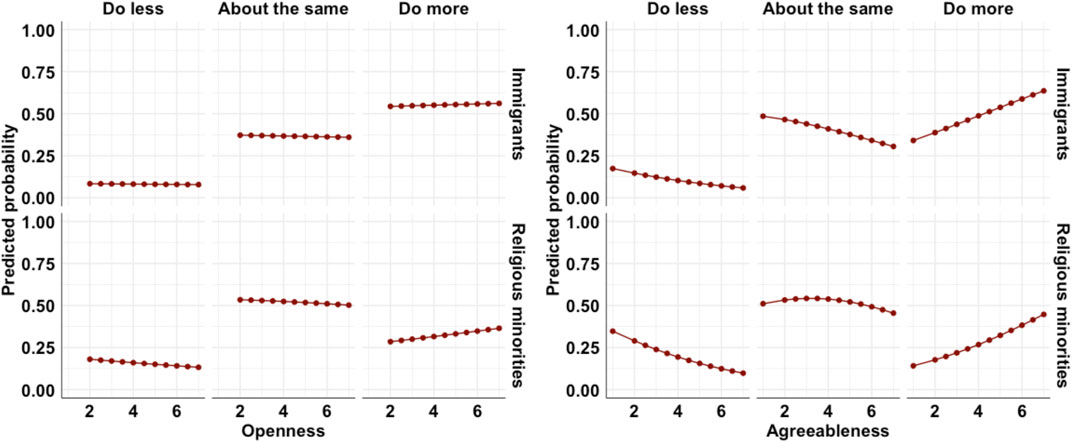

Figure 1 reports the change in the predicted probability of selecting each response option when evaluating the level of support needed for immigrants and religious minorities as a function of candidates’ self-reported levels of agreeableness and open-mindedness, using the coefficients reported in Table 2 (models 2 and 5).7 As predicted, more agreeable candidates are significantly more likely to recognize the need to do more for both minority groups. The positive association between agreeableness and support for religious minorities is strengthened somewhat among candidates in the most diverse municipalities, however there is no difference in the strength to which agreeableness is associated with increased support for immigrants across municipalities with different levels of diversity.

FIGURE 1. Predicted probabilities associated with endorsing various levels of support for immigrants and religious minorities as a function of self-reported agreeableness and openness to experience.

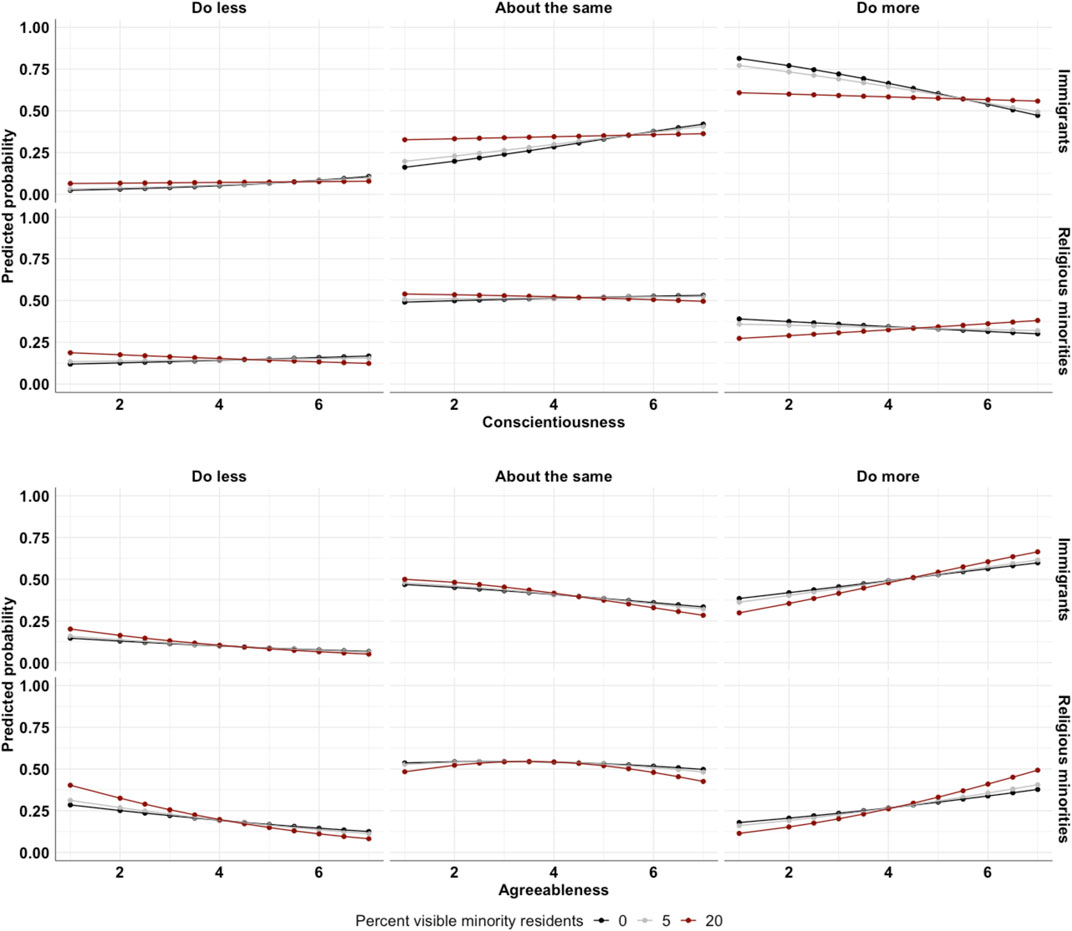

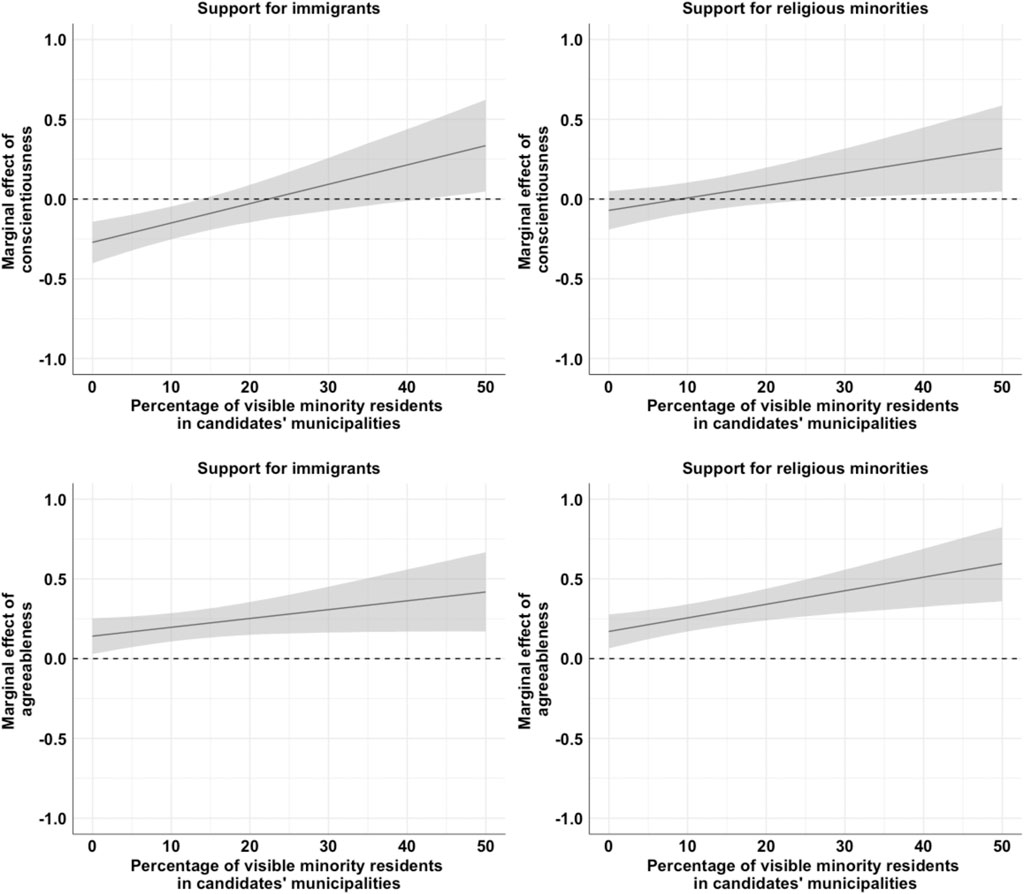

Against our expectations, open-mindedness is not associated with a higher likelihood of supporting the need to do more for immigrants and religious minorities, independent of the other individual and constituency covariates in the model. Likewise, there is no evidence of a general decrease in support among the more conscientious politicians. Conscientiousness, however, also interacts with constituency diversity in predictable ways to explain the perceived need of immigrants. These interaction effects are visualized in Figure 2 which plots the changing probability of endorsing each level of support for immigrants and religious minorities as a function of candidates’ self-assessed level of conscientiousness or agreeableness and the proportion of visible minority residents in politicians’ municipalities.

FIGURE 2. Moderation effects of constituency diversity on the relationship between conscientiousness, agreeableness and recognition of the needs of immigrants and religious minorities.

To aid in the visualization of the interaction, the proportion of visible minority residents is trichotomized into discrete levels: when visible minorities are absent from a constituency, when the proportion of visible minority residents is at approximately the sample median, and when the proportion of visible minority residents is high, at 20% of the population. As the data show, the level of ethnocultural diversity in a municipality can suppress the negative association between conscientiousness and support for immigrants, as expected from prior research on the interaction between conscientiousness, situational cues, and immigration attitudes (Ackermann and Ackermann, 2015; Dinesen et al., 2016). When the proportion of visible minorities in a municipality is high, the negative relationship between conscientiousness and support for doing more for immigrants disappears. The opposite effect is found with respect to the interaction between agreeableness and candidates’ recognition of the needs of religious minorities, strengthening in highly diverse ridings. Together, the results show that the association between certain personality traits and candidates’ recognition of the needs of immigrants and religious minorities are conditional on situational factors such as the level of diversity in one’s surroundings. The marginal effects of agreeableness and conscientiousness at different levels of municipal diversity are visualized in Figure 3, which illustrate how conscientiousness becomes significantly positively associated with support for the needs of immigrants and religious minorities in highly diverse districts, while the positive associations between agreeableness persist, albeit to a weaker degree, at low levels of diversity.

FIGURE 3. Marginal effects of conscientiousness and agreeableness on the predicted level of support for immigrants and religious minorities across municipalities with contrasting proportions of visible minority residents (84% confidence intervals).

Discussion and Conclusion

Demographic changes brought on by international migration patterns are resulting in an electorate that is increasingly diverse. Yet, in many instances, minority communities remain under-represented in legislative bodies, relying instead on politicians from other backgrounds to speak out on the issues that affect them. Politicians’ recognition of the needs of others can be an important precursor to political representation. Still, research shows that politicians may discount the needs of those from minority backgrounds, focusing attention on issues that align with their own priorities and preferences (Butler et al., 2011; Butler, 2014; Dinesen et al, 2021). Nonetheless some politicians do continue to advocate for the needs of under-served communities. What motivates the responsiveness of political actors to the needs of others?

We argue that candidates’ personalities are important in their own right, a unique and understudied source of variation in one’s recognition of the needs of minorities. Research on representation points to the importance of politicians’ own background (Bird, 2011; Broockman, 2013), showing that politicians are most likely to advocate on behalf of minority interests when they themselves share in a common group membership with constituents from minority communities (Black, 2011; Saalfeld and Bischof, 2013; Sobolewska et al., 2018). However, common descriptive characteristics are not necessary preconditions to advocate on behalf of others. Instead, other intrinsic motives apart from shared experiences push certain candidates to show solidarity with minority constituents. While electoral considerations offer an external incentive to attend to issues affecting minorities, recent experimental research involving politicians shows electoral motives may not always be sufficient at overcoming individual differences in how responsive politicians are to appeals from minorities (Dinesen et al., 2021).

Individual differences in personality motivate political orientations (Sibley et al., 2012) and evaluations of others (Crawford and Brandt, 2019). Personality traits are also tied to variation in a number of social and political outcomes, including attitudes toward immigration and refugee (Ackermann and Ackermann, 2015; Dinesen et al., 2016; Ziller and Berning, 2019; Pruysers, 2020). We extend this research, showing how political candidates’ personalities, together with characteristics of their local area, influence their recognition of the needs of immigrants and religious minorities. Candidates’ agreeableness explains significant variation in their recognition of the needs of immigrants and religious minorities, independent of their own background, general left-right political orientations, and characteristics of the constituencies they seek to represent. We find political candidates to be more likely to recognize immigrants as in need of more supports than religious minorities. We also find some qualified evidence that more conscientious candidates are, on average, less likely to recognize the need to do more for immigrants, but this negative tendency is only expressed among candidates running in elections in municipalities with very low levels of ethnocultural diversity. Some aspects of candidates’ personalities are independently associated with their recognition of the needs of others, whereas other individual differences work in conjunction with situational factors in candidates’ localities to shape the level of supports perceived to be needed by immigrants.

The findings support several of our expectations and are in line with meta-analyses in personality and social psychology that point to agreeableness as a core disposition shaping how individuals relate to others (Crawford and Brandt, 2019). Research has shown that politicians tend to score high on this trait (Dietrich et al., 2012; Caprara et al., 2003; Hanania, 2017). Individuals who seek political office may, in general, be somewhat more predisposed to recognizing the needs of others. Seeing as populations in Western democracies are becoming more diverse, and that descriptive political representation often falls short, the relationship between agreeableness and the recognition of the needs of others may be advantageous for the substantive representation of minorities’ interests.

Yet, the findings regarding conscientiousness and open-mindedness run counter to our expectations. Conscientiousness is found to be associated with reduced support for doing more for immigrants but only in localities that are overwhelmingly white. Our data show that this negative association is not observed when assessing the needs of religious minorities, suggesting that different considerations are at play when evaluating the needs of immigrants and religious minorities. As for candidates’ openness to experience, we do not find this trait to be associated with greater support for the need to do more for either minority group. Further analyses, however, suggest the association between openness to experience appears to be masked by respondents’ left-right political orientation (see Supplementary Table A2). The fact that this effect disappears after controlling for individuals’ left-right political self-placement adds support to the notion that open-mindedness influences outgroup attitudes for primarily ideological reasons, whereas agreeableness remains relatively unchanged by the addition of a control for political orientation.

The results also point to important similarities and differences in the way the needs of immigrants and religious minorities are perceived. Overall, the Canadian municipal candidates participating in our research are much more likely to acknowledge the need to do more for immigrants than they are for religious minorities, pointing to a potentially higher barrier to recognizing and attending to issues that impact religious diversity and religious minority communities in Canada. This finding points to an important distinction in how these two minority communities are perceived with implications for the protection and promotion of different forms of diversity in multicultural Canada. Future research is needed to uncover how these two groups cue different sets of considerations about the levels of perceived need.

That immigrants and religious minorities are perceived as having different levels of neediness has implications for the representation of religious minority communities. If religious minorities are not perceived as a group in need, members of religious minority communities may be disadvantaged by a lack of support by political representatives when issues targeting religious minorities appear on the legislative agenda. The greater tendency among many politicians not to perceive religious minority communities as in need of additional supports is an important consideration as legislation that targets people of faith, such as bans on religious symbols in the public service, are increasingly appearing on the legislative agenda in the public debate over secularism and the limits of peoples’ willingness to accommodate diversity. In the absence of descriptive representation, minority communities are dependent on the substantive representation of issues important to them by politicians that do not share in their background. Religious minorities may therefore face particular difficulty getting the attention of political actors. Although common demographic characteristics are associated with increased recognition of the needs of both immigrants and religious minorities, younger, left-leaning candidates were somewhat less sympathetic to the needs of religious minorities than they are for the needs of immigrants. Future research could better focus on the reason for these divergent views by assessing candidates’ perceptions of the supports available to these minority communities and the barriers faced by members of both groups. Clearly, however, participants do not perceive the neediness of immigrants and religious minorities to be the same.

The argument that personality motivates politicians’ considerations about the needs of others is not a deterministic one. Rather, personality and situational forces interact to influence politicians’ responsiveness. The results echo those of Ackermann and Ackermann (2015) who find that the perception of increased diversity in one’s neighborhood attenuates the tendency for more conscientious individuals to oppose equal opportunities for immigrants. Other researchers have further illustrated how situational considerations may shape the responses of highly conscientious individuals to immigration. Dinesen and colleagues (2016) also report experimental evidence showing that the tendency of highly conscientious individuals to oppose increased immigration can be alleviated by considerations about the high skill level of migrants. We also show that a different contextual consideration, the proportion of ethnocultural diversity in a locality as measured by the share of visible minority residents in candidates’ municipalities, can also suppress the tendency for more conscientious candidates to be less willing to recognize the increased needs of immigrants. While their data also show the relationship between agreeableness and support for increased immigration is conditional on contextual cues, our data point to a consistent, positive association between agreeableness and recognition of support for both immigrants and religious minorities regardless of the level of diversity in a municipality.

This research, of course, is limited in important ways. To facilitate data collection, we relied on publicly available e-mail addresses. Although most candidates do publish this information, it is not a requirement and as a result some municipal candidates were excluded from our sampling frame. Our sample also consists of predominantly White politicians. Although we control for whether or not candidates self-identify as belonging to a predominantly white ethnic background, differences in how ethnic majority and minority politicians perceive the needs of immigrants and religious minorities may differ between candidates belonging to majority or minority backgrounds. Our sample size precludes a more nuanced analysis of these differences. Our survey also did not include questions on candidates’ own immigration or religious background, preventing us from examining whether candidates’ recognition of need changes when candidates share an affinity with members from either group. Finally, we were unable to obtain more precise ward-level data on the make-up of politicians’ municipal constituencies. As such, we are required to draw on the census subdivision level, which corresponds to the municipality as a whole and results in a slightly less precise level of aggregation than the candidates’ electoral wards. Future research might consider not only contextual data on a much more localized level but should also measure the frequency and valence of direct contact experiences with diversity.

Another practical limitation of survey research involving political candidates is the need to utilise very brief survey instruments. While the measures used in the present research facilitate this task, they come with a trade-off in construct validity inherent in any very short measure of extensive personality inventories (see Bakker and Lelkes, 2018). In light of the persistent, positive relationship between agreeableness and support for minority groups (Gallago and Pardos-Prado, 2014; Ackermann and Ackermann, 2015; Dinesen et al., 2016; Crawford and Brandt, 2019; Ziller and Berning, 2019), future research could benefit from studying relevant personality traits in more depth, opting for larger inventories to measure agreeableness (or another dimensions of personality) at the expense of other traits which exhibit limited or null relationships between intergroup attitudes across studies. Finally, although we believe a benefit of our survey methodology is to explore candidates’ intrinsic motivations to recognize the needs of minority groups outside of a legislative setting and during an ongoing campaign, we cannot be sure of the extent to which such recognition translates into tangible policy outcomes or actual legislative behavior.

Notwithstanding these limitations, our data add nuance to the existing literature on personality and politics and the interplay between intrinsic and constituency motivations in shaping politicians support for immigrants and religious minorities. The results contribute to the growing literature on personality and politics by illustrating how core personality traits commonly associated with diversity attitudes also motivate politicians’ perceptions of the needs of minority groups. Such recognition is an important precursor to political representation and taken together, the data offer new insights into the intrinsic motivations of municipal candidates to support the needs of others.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available to the public. This dataset was collected from candidates recruited during an ongoing political campaign during 2018. As a reassurance to the individuals that participated in the research, we guaranteed the protection of their data in the consent form, explicitly stating that participants’ individual data would not be shared in any format outside the research team (the authors). As such, we are unable to provide the raw data. Data requests and related inquiries should be directed to Y29saW4uc2NvdHQyQG1haWwubWNnaWxsLmNh.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by McGill University REB: 194-1017. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

CS designed the study, assisted in the data collection, conducted the data analyses, and drafted the manuscript. MM assisted in the research design, data collection and drafting of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2021.674164/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1In total, 6,645 candidates ran in 417 municipalities in Ontario for mayor or councillor positions, whereas British Columbia had 2,223 municipal candidates across 158 municipalities. A total of 4,981 municipal candidates were invited to participate in the survey, 3,228 from Ontario and 1,753 from British Columbia. Of those invited to participate in the study, 1,017 returned questionnaires from Ontario and 596 from British Columbia, resulting in a response rate of 32% for Ontario and 34% for British Columbia. We use a subset of these respondents (N = 1,073) in the present analyses who provided complete information on our core variables of interest.

2The level of aggregation is the census subdivision, which correspondents to provincial municipalities in Canada.

3Statistics Canada defines visible minorities as any group of persons who identify as non-Caucasian and non-Indigenous, consisting primarily of Blacks, Asians (including individuals identifying as Chinese, Korean, Filipino or from other countries in South, South-Eastern or Western Asia), Arabs or Latin Americans.

4The dataset also contained a question wording experiment as part of a separate study that asked politicians to rate their support for a ban on religious symbols (control condition) or to consider strong public support for a ban on religious symbols or the rise in anti-Muslim discrimination (treatment conditions) and evaluate their own support for the proposal. Politicians were randomly assigned to these three experimental conditions, which were asked prior to the questions on politicians’ support for immigrants and religious minorities. The condition assigned did not have a significant influence on candidates’ support for the need to do more for immigrants, χ2 (4) = 2.87, p = 0.58, or religious minorities χ2 (4) = 5.73, p = 0.22, nonetheless, dummy variables are included in all models below to control for exposure to these alternative questions.

5To test for any relationship between the level of diversity in respondents’ municipalities and their reported personality traits, a series of one-way analyses of variance were computed, with p-values adjusted for multiple comparisons (i.e., a Bonferroni correction with alpha set to p = 0.01). None of the personality traits were significantly associated with a three-level (low, medium high; see Table 1) categorical measure of constituency diversity: Openness: F(2, 1,070) = 2.68, p = 0.07; Conscientiousness: F(2, 1,070) = 0.53, p = 0.59; Extraversion: F(2, 1,070) = 1.66, p = 0.19; Agreeableness: F(2, 1,070) = 0.39, p = 0.68; Neuroticism: F(2, 1,070) = 2.33, p = 0.10. A series of linear regressions with the continuous measure of percentage of visible minorities was also non-significant for each personality trait (ps > 0.05).

6Brant tests do not suggest significant violations of the parallel-trends assumption for either outcome measure.

7Predicted probabilities are estimated holding all other variables at their mean or modal value, as well as for respondents assigned to the control condition on our question wording experiment on supporting bans on religious symbols.

References

Ackermann, K., and Ackermann, M. (2015). The Big Five in Context: Personality, Diversity and Attitudes toward Equal Opportunities for Immigrants in Switzerland. Swiss Polit. Sci. Rev. 21, 396–418. doi:10.1111/spsr.12170

Ashton, M. C., and Lee, K. (2007). Empirical, Theoretical, and Practical Advantages of the HEXACO Model of Personality Structure. Pers Soc. Psychol. Rev. 11, 150–166. doi:10.1177/1088868306294907

Bakker, B. N., and Lelkes, Y. (2018). Selling Ourselves Short? How Abbreviated Measures of Personality Change the Way We Think about Personality and Politics. J. Polit. 80, 1311–1325. doi:10.1086/698928

Banting, K., and Soroka, S. (2020). A Distinctive Culture? the Sources of Public Support for Immigration in Canada, 1980-2019. Can. J. Pol. Sci. 53, 821–838. doi:10.1017/S0008423920000530

Berry, J. W., and Kalin, R. (1995). Multicultural and Ethnic Attitudes in Canada: An Overview of the 1991 National Survey. Can. J. Behav. Sci./Revue canadienne des Sci. du comportement 27, 301–320. doi:10.1037/0008-400x.27.3.301

Bilodeau, A., Turgeon, L., White, S., and Henderson, A. (2018). Strange Bedfellows? Attitudes toward Minority and Majority Religious Symbols in the Public Sphere. Polit. Religion 11, 309–333. doi:10.1017/s1755048317000748

Bird, K. (2011). “Patterns of Substantive Representation Among Visible Minority MPs: Evidence from Canada’s House of Commons,” in The Political Representation of Immigrants and Minorities. Voters, Parties and Parliaments in Liberal Democracies. Editors Saalfeld. Bird, and Wüst (New York, USA: Routledge).

Black, J. H. (2011). “Who Represents Minorities? Question Period, Minority MPs, and Constituency Influence in the Canadian Parliament,” in Just Ordinary Citizens?: Towards a Comparative Portrait of the Political Immigrant. Editor A. Bilodeau (Toronto, Canada: University of Toronto Press).

Blais, J., and Pruysers, S. (2017). The Power of the Dark Side: Personality, the Dark Triad, and Political Ambition. Personal. Individual Differences 113, 167–172. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2017.03.029

Broockman, D. E. (2013). Black Politicians Are More Intrinsically Motivated to Advance Blacks' Interests: A Field Experiment Manipulating Political Incentives. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 57, 521–536. doi:10.1111/ajps.12018

Butler, D. M., Broockman, D. E., Caprara, G. V., Barbaranelli, C., Consiglio, C., Picconi, L., et al. (2011). Do politicians Really Discriminate against Constituents? A Field experiment on State legislatorsPersonalities of Politicians and Voters: Unique and Synergistic Relationships. Am. J. Polit. ScienceJournal Personal. Soc. Psychol. 55 (4), 463–477. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5907.2011.00515.x 200384849856

Butler, D. M. (2014). Representing the Advantaged: How Politicians Reinforce Inequality. New York, USA: Cambridge University Press.

Caprara, G. V., Barbaranelli, C., Consiglio, C., Picconi, L., and Zimbardo, P. G. (2003). Personalities of Politicians and Voters: Unique and Synergistic Relationships. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 84 (4), 849–856. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.849

Crawford, J. T., and Brandt, M. J. (2019). Who Is Prejudiced, and toward Whom? the Big Five Traits and Generalized Prejudice. Pers Soc. Psychol. Bull. 45, 1455–1467. doi:10.1177/0146167219832335

Dietrich, B. J., Lasley, S., Mondak, J. J., Remmel, M. L., and Turner, J. (2012). Personality and Legislative Politics: The Big Five Trait Dimensions Among U.S. State Legislators. Polit. Psychol. 33 (2), 195–210. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9221.2012.00870.x

Dinesen, P. T., Dahl, M., and Schiøler, M. (2021). When Are Legislators Responsive to Ethnic Minorities? Testing the Role of Electoral Incentives and Candidate Selection for Mitigating Ethnocentric Responsiveness. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 115 (2), 450–466. doi:10.1017/S0003055420001070

Dinesen, P. T., Klemmensen, R., and Nørgaard, A. S. (2016). Attitudes toward Immigration: The Role of Personal Predispositions. Polit. Psychol. 37, 58–72. doi:10.1111/pops.12220

Ekehammar, B., Akrami, N., Gylje, M., and Zakrisson, I. (2004). What Matters Most to Prejudice: Big Five Personality, Social Dominance Orientation, or Right-Wing Authoritarianism?. Eur. J. Pers 18, 463–482. doi:10.1002/per.526

Ekehammar, B., and Akrami, N. (2003). The Relation between Personality and Prejudice: a Variable - and a Person-Centred Approach. Eur. J. Pers 17, 449–464. doi:10.1002/per.494

Esses, V. M. (2021). Prejudice and Discrimination toward Immigrants. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 72, 503–531. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-080520-102803

Fatke, M. (2017). Personality Traits and Political Ideology: A First Global Assessment. Polit. Psychol. 38, 881–899. doi:10.1111/pops.12347

Fennelly, K., and Federico, C. (2008). Rural Residence as a Determinant of Attitudes toward US Immigration Policy. LA RURALITÉ EN TANT QUE FACTEUR DÉTERMINANT DE LA MANIÈRE DONT EST PERÇUE LA POLITIQUE D'IMMIGRATION AUX ETATS-UNIS. RESIDENCIA EN ZONAS RURALES COMO FACTOR DETERMINANTE DE LA ACTITUD HACIA LA POLÍTICA DE INMIGRACIÓN DE LOS ESTADOS UNIDOS. Int. Migration 46, 151–190. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2435.2008.00440.x

Ferland, B. (2018). L'impact des minorités visibles sur l'appui à la Charte des valeurs et l'interdiction des signes religieux. Can. J. Pol. Sci. 51, 23–59. doi:10.1017/s0008423917001500

Gallago, A., and Pardos-Prado, S. (2014). The Big Five Personality Traits and Attitudes towards Immigrants. J. Ethnic Migration Stud. 40, 79–99.

Gerber, A. S., Huber, G. A., Doherty, D., Dowling, C. M., and Ha, S. E. (2010). Personality and Political Attitudes: Relationships across Issue Domains and Political Contexts. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 104, 111–133. doi:10.1017/s0003055410000031

Gerber, A. S., Huber, G. A., Doherty, D., and Dowling, C. M. (2011). The Big Five Personality Traits in the Political arena. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 14, 265–287. doi:10.1146/annurev-polisci-051010-111659

Gosling, S. D., Rentfrow, P. J., and Swann, W. B. (2003). A Very Brief Measure of the Big-Five Personality Domains. J. Res. Personal. 37, 504–528. doi:10.1016/s0092-6566(03)00046-1

Graziano, W. G., Habashi, M. M., Sheese, B. E., and Tobin, R. M. (2007). Agreeableness, Empathy, and Helping: A Person × Situation Perspective. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 93 (4), 583–599. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.93.4.583

Hainmueller, J., and Hopkins, D. J. (2014). Public Attitudes toward Immigration. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 17, 225–249. doi:10.1146/annurev-polisci-102512-194818

Hanania, R. (2017). The Personalities of Politicians: A Big Five Survey of American Legislators. Personal. Individual Differences 108, 164–167. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2016.12.020

Harell, A., Soroka, S., Iyengar, S., and Valentino, N. (2012). The Impact of Economic and Cultural Cues on Support for Immigration in Canada and the United States. Can. J. Pol. Sci. 45, 499–530. doi:10.1017/s0008423912000698

John, O. P., and Srivastava, S. (1999). “The Big Five Trait Taxonomy: History, Measurement, and Theoretical Perspectives,” in Handbook of Personality: Theory and Research. Editors L. A. Pervin, and O. P. John (New York, USA: Guilford Press).

Kokkonen, A., and Karlsson, D. (2017). That's what Friends Are for: How Intergroup Friendships Promote Historically Disadvantaged Groups' Substantive Political Representation. Br. J. Sociol. 68, 693–717. doi:10.1111/1468-4446.12266

Mansbridge, J. (2003). Rethinking Representation. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 97, 515–528. doi:10.1017/s0003055403000856

Mondak, J. J. (2010). Personality and the Foundations of Political Behavior. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511761515

Nai, A., and Maier, J. (2020). Dark Necessities? Candidates' Aversive Personality Traits and Negative Campaigning in the 2018 American Midterms. Elect. Stud. 68, 102233. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2020.102233

Nai, A., and Martínez i Coma, F. (2019). The Personality of Populists: Provocateurs, Charismatic Leaders, or Drunken Dinner Guests?. West Eur. Polit. 42, 1337–1367. doi:10.1080/01402382.2019.1599570

Palmer, D. L. (1996). Determinants of Canadian Attitudes toward Immigration: More Than Just Racism?. Can. J. Behav. Sci./Revue canadienne des Sci. du comportement 28, 180–192. doi:10.1037/0008-400x.28.3.180

Paulhus, D. L., and Williams, K. M. (2002). The Dark Triad of Personality: Narcissism, Machiavellianism, and Psychopathy. J. Res. Personal. 36, 556–563. doi:10.1016/s0092-6566(02)00505-6

Pruysers, S. (2020). Personality and Attitudes towards Refugees: Evidence from Canada. J. Elections, Public Opin. Parties. doi:10.1080/17457289.2020.1824187

Saalfeld, T., and Bischof, D. (2013). Minority-ethnic MPs and the Substantive Representation of Minority Interests in the House of Commons, 2005-2011. Parliamentary Aff. 66, 305–328. doi:10.1093/pa/gss084

Scott, C., and Medeiros, M. (2020). Personality and Political Careers: What Personality Types Are Likely to Run for Office and Get Elected?. Personal. individual differences 152, 109600. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2019.109600

Sibley, C. G., and Duckitt, J. (2008). Personality and Prejudice: A Meta-Analysis and Theoretical Review. Pers Soc. Psychol. Rev. 12, 248–279. doi:10.1177/1088868308319226

Sibley, C. G., Osborne, D., and Duckitt, J. (2012). Personality and Political Orientation: Meta-Analysis and Test of a Threat-Constraint Model. J. Res. Personal. 46, 664–677. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2012.08.002

Sobolewska, M., McKee, R., and Campbell, R. (2018). Explaining Motivation to Represent: How Does Descriptive Representation lead to Substantive Representation of Racial and Ethnic Minorities?. West Eur. Polit. 41, 1237–1261. doi:10.1080/01402382.2018.1455408

Soroka, S., and Roberton, S. (2010). A Literature Review of Public Opinion Research on Canadian Attitudes toward Multiculturalism and Immigration, 2006-2009Citizenship and Immigration Canada, Research and Evaluation. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195335354.003.0015

Talay, L., and De Coninck, D. (2020). Exploring the Link between Personality Traits and European Attitudes towards Refugees. Int. J. Intercultural Relations 77, 13–24. doi:10.1016/j.ijintrel.2020.04.002

Turgeon, L., Bilodeau, A., White, S. E., and Henderson, A. (2019). A Tale of Two Liberalisms? Attitudes toward Minority Religious Symbols in Quebec and Canada. Can. J. Pol. Sci. 52, 247–265. doi:10.1017/s0008423918000999

Wilkes, R., and Corrigall-Brown, C. (2011). Explaining Time Trends in Public Opinion: Attitudes towards Immigration and Immigrants. Int. J. Comp. Sociol. 52, 79–99. doi:10.1177/0020715210379460

Keywords: personality, candidates, constituency diversity, immigrants, religious minorities, minority interests, political recognition

Citation: Scott C and Medeiros M (2021) Recognizing the Needs of Others: Municipal Candidates’ Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivations to Support Immigrants and Religious Minorities. Front. Polit. Sci. 3:674164. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2021.674164

Received: 28 February 2021; Accepted: 14 May 2021;

Published: 21 June 2021.

Edited by:

Laura Stephenson, Western University, CanadaReviewed by:

Scott Pruysers, Dalhousie University, CanadaRodney Kenneth Smith, The University of Sydney, Australia

Copyright © 2021 Scott and Medeiros. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Colin Scott, Y29saW4uc2NvdHQyQG1haWwubWNnaWxsLmNh

Colin Scott

Colin Scott Mike Medeiros

Mike Medeiros