- 1École Nationale d'administration Publique, Montreal, QC, Canada

- 2Department of Humanities, Letters and Communication, Université Téluq, Montreal, QC, Canada

This paper has looked at the evolution of attitudes toward welfare recipients and the impact of authoritarian dispositions on these attitudes in the context of the Covid-19 health crisis. We used two representative surveys, the first (n = 2,054) conducted in the summer of 2019 and the second (n = 2,060) in Quebec in June 2020, near the end of the first wave of the Covid-19 pandemic in the province. One thousand one hundred and seventy eight participants in the second survey had also participated in the first, allowing to analyze potential movement among many of the same individuals. Overall, while our results clearly indicated that authoritarian dispositions were associated with more negative views of welfare recipients, the pandemic does not appear to have affected the relationship between these attitudes and authoritarian traits. Additionally, we found no evidence that a direct measure of perceived threat moderated the relation between authoritarianism and attitude toward welfare recipients. Yet, we did find that, in the context of the pandemic, authoritarianism was associated with the attribution of lower deservingness scores to welfare recipients who were fit for work, suggesting that authoritarianism interacts with an important deservingness heuristic when evaluating who deserves to be helped.

1. Introduction

Research about authoritarian personality traits has seen growing interest in the past few years as various mostly right-leaning political movements have captured political scientists' attention. Although authoritarianism is indeed frequently linked to attitudes that directly challenge the foundations of liberal democracies, the trait may also be related to more mundane opinions about a variety of political issues that can impact public policy and the concrete lives of many groups of people. As part of a larger project studying attitudes toward welfare recipients, this paper examines the impacts of authoritarian personality traits on opinions about people in need of social and economic assistance.

The year 2020 was marked by a pandemic of a magnitude not seen in a hundred years and necessitated containment measures to stop the spread of Covid-19. Most industrialized countries have also put in place a variety of programs to support their populations severely affected by a health crisis with significant social and economic repercussions. Many people have had to receive various types of support in order to enable them to get through this crisis and most of those who needed help are not the ones who usually require government assistance. The shock produced by the health crisis is therefore likely to have altered perceptions of those who need public supports. However, while the crisis has certainly affected them as well, people on social assistance are not the ones targeted by most of the support programs put in place as a result of the pandemic. This is because although they may be affected in a variety of ways, their occupation and source of income cannot have been directly affected by the crisis because they were not at work before the pandemic, and their income was already dependent on governmental assistance. Furthermore, we will see that there are several elements that can lead us to believe that these people are very likely to be perceived as less deserving and that this affects opinions about the help they should receive. We also have reasons to believe that authoritarian dispositions could play a role in shaping these perceptions.

The political psychology literature generally conceptualizes authoritarianism as a disposition that can be activated or muted depending on the context, and especially the presence of a threat to the social order (Feldman, 2003; Stenner, 2005). To that effect, the Covid-19 pandemic, along with its economic and social consequences, introduced a contextual shock that is susceptible to have impacted the activation of authoritarian traits among citizens, and consequently the attitudes that are likely affected by the trait. Moreover, opinions about policies aiming to provide help to various groups are very likely to be influenced by deservingness heuristics (Gilens, 2000), which may impact how authoritarianism affects opinions about who should be helped and by how much.

This paper aims to explore these questions by using a two waves panel data collected in Quebec to investigate citizens' attitudes toward welfare recipients before and during the Covid-19 pandemic. After reviewing the relevant literature, we will first examine whether thermometer ratings received by welfare recipients differed before and during the first wave of the pandemic in Quebec. We will also investigate whether authoritarianism was associated with change in opinions between the two waves. We will then look at respondents' generosity toward various types of welfare recipients, analyze whether any change occurred between the two waves, and look at the potential impact of authoritarianism on these attitudes. Finally, we will turn to more direct opinions about which groups deserve help in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic, how welfare recipients are positioned in this context, and how authoritarianism affects opinions about how deserving they are perceived to be. Overall, we find that although authoritarianism is related to more negative views about welfare recipients, it was not related to change in perceptions before and during the pandemic.

This paper contributes to the growing literature on authoritarian dispositions and examines their impact in the unique context of the shock associated with the Covid-19 health crisis, which is likely to have significantly affected perceptions of social threat among many individuals. Our results allow us to better understand and circumscribe the contexts in which different types of threats can activate authoritarian dispositions.

2. Authoritarianism in Political Psychology

Authoritarianism has a rich and controversial research tradition in political science. Adorno et al. (1950) first conceptualized the trait and argued that it is a “personality syndrome” composed of nine separate dimensions such as conventionalism, authoritarian submission, authoritarian aggression, or anti-intellectualism. In order to measure this trait, Adorno et al. produced the Fascist Scale (F-Scale), which has been both influential and severely criticized for its methodological shortcomings (see Altemeyer, 1981; Duckitt, 1992; Feldman, 2003; Brown, 2004).

Altemeyer (1996) later proposed that submission, conventionalism, and authoritarian aggression were the three general dimensions of authoritarianism and proposed the “Right-Wing Authoritarianism” (RWA) scale to measure the trait. Although largely considered as an improvement over the original conceptualization, Altemeyer's RWA measure has also been criticized for including several items that confuse authoritarianism for many of its potential outcomes. In short, the main criticism is that the RWA measure is partly tautological since it directly measures political attitudes. It is therefore not surprising that the scale is then highly correlated with these attitudes (Feldman, 2003; Stenner, 2005; Hetherington and Weiler, 2009).

Feldman (2003) proposed to conceptualize authoritarianism as a disposition emanating from the tension between the values of social conformity and personal autonomy, which are thought as trade-offs inherent to being part of a society. In the tension between the two values, individuals who tend to favor social conformity over personal autonomy are thought to be more authoritarian. Seeking to establish a scale that adequately captures the tension between individual autonomy and social conformity without evoking political attitudes or political objects, Feldman (2003) proposed a strategy based on measuring attitudes about the best qualities to instill in children. Respondents are presented with a set of four of the pairs of qualities directly related to the tension between autonomy and conformity, and are asked to choose the quality they consider most important. The pairs are whether it is more important that a child to be “independent or respectful of his/her parents,” to have “an enquiring mind or be well-mannered,” to be “well-behaved or creative,” and to be “obedient or autonomous.” Measuring preferences and attitudes toward parenting styles, especially in relation with themes associated with obedience and authority, is now the most common method used in political science for measuring authoritarian personality traits (see Feldman and Stenner, 1997; Feldman, 2003; Stenner, 2005; Hetherington and Weiler, 2009; Federico et al., 2011; Henry, 2011; Hetherington and Suhay, 2011; Brandt and Henry, 2012; Brandt and Reyna, 2014).

Generally speaking, it has been shown that authoritarians are much less supportive of groups that seem to deviate from established norms. For instance, Barker and Tinnick (2006) have shown that authoritarianism decreases support for gay rights, and Altemeyer (1996) finds that authoritarians are much more sympathetic to harsh treatments of groups perceived to be deviating from the norm. These tendencies also extend to racial minorities and ethnic groups, as authoritarianism has been shown to increase negative stereotypes of these groups (Sniderman and Piazza, 1993; Stenner, 2005; Parker and Towler, 2019). In Europe, authoritarianism has been shown to be positively related to voting for far-right parties in Austria, Belgium, Denmark, the Netherlands, and Switzerland (Dunn, 2015; Aichholzer and Zandonella, 2016). Studying the French electorate, Vasilopoulos and Lachat (2018) also find that authoritarianism is related to intolerance, economic conservatism, likelihood to support both the far-right Front-National and the far-left parties.

Some scholars are arguing that authoritarianism is too unstable to qualify as a personality trait (see for instance: Asendorpf and Van Aken, 2003; Van Hiel et al., 2004; McAdams and Pals, 2006; Sibley et al., 2007). Others find that the trait is highly inherited and stable over time (see McCourt et al., 1999; Ludeke and Krueger, 2013). Although Adorno et al. (1950) initially conceptualized the trait as deeply rooted in individuals' personality, Altemeyer (1981) argued that it was mostly a predisposition acquired through childhood experiences. Feldman (2003) and Stenner (2005) have mostly argued that authoritarianism is a general disposition, and the literature remains generally unsure about the exact nature of the characteristic (Hetherington and Weiler, 2009).

Additionally, the literature suggests that authoritarianism is highly related to perceptions of threat (Feldman, 2003; Stenner, 2005), as multiple studies have found that perceived threat interact with authoritarianism when it comes to opinions and behaviors regarding marginalized groups (Duckitt, 1989, 2001; Doty et al., 1991; Feldman and Stenner, 1997; Rickert, 1998; Lavine et al., 1999, 2005; Feldman, 2003). Interestingly, Arikan and Sekercioglu (2019) have shown that this is the case for opinions about distributive policies as well. Authoritarianism now tends to be viewed as a latent disposition that can be activated or muted depending on the context, and more specifically depending on perceived threat.

3. Authoritarianism, Attitudes Toward People in Need, and the Covid-19 Crisis

When it comes to opinions about people receiving welfare benefits, the literature points to the importance of a heuristic based on the perception of the “unlucky” or “lazy” nature of the person or group targeted for support. In the early 1980s, Coughlin (1980) reported that in most Western countries, citizens are largely supportive of policies aiming to provide financial support for the elderly, the sick and infirm, and families with children in need. Almost everywhere, the people for whom citizens are least supportive are those on social assistance. These results have also been replicated more recently in Europe (Oorschot, 2006). The implication is that in all countries, the groups toward whom citizens are most generous are those who are in a situation of dependency for reasons deemed beyond their control.

In a seminal book studying public opinion on welfare policies in the United States, Gilens (2000) demonstrates that Americans generally support welfare policies when recipients are judged to be “deserving” as opposed to those who would be “undeserving.” He also shows that the American public is uninformed about who receives assistance, that media representations of recipients tend to over-represent the proportion of African–American people among welfare recipients, and that the American public is largely inclined to view welfare policies as primarily a program to support black people. He shows that racial attitudes are the most important factor structuring white Americans' views about welfare. Among three important stereotypes that often affect the perceptions of African Americans (that they are lazy, unintelligent, and violent), Gilens finds that laziness is the only one that is associated with opposition to welfare policies.

Important work mobilizing the evolutionary biology framework also sheds new light on the psychological mechanisms underlying deservingness heuristics. According to Petersen et al. (2011), deservingness heuristics are the result of an evolutionary adaptation process, in which those who offer help are doing something risky in that they are providing effort and resources that might not produce a reciprocal act if the need arose. As a result, the individual acts underlying collective supports generate a strong need to quickly distinguish between “cheaters” and those who reciprocate. Those who are perceived as merely profiteers from collective support and who are perceived as unlikely to contribute to its establishment will be considered undeserving of support, while those who are seen as potential contributors will be considered deserving. The level of effort displayed by individuals is the simplest heuristic for making quick and efficient judgments about who deserves help and who does not. Those in need who are judged to be lazy will be seen as cheating, while those who are more likely to be considered unlucky will be seen as possibly capable of reciprocity, and therefore deserving of support. Petersen (2012) shows that individuals do use heuristics related to the perception of effort and that these psychological processes are effective at both small and large collective scales. Petersen et al. (2011) also argue that merit heuristics are so central to collective action that they are automatically activated without individuals even realizing it and that factors as physical as the level of hunger affect opinions about policies related to resource sharing (Petersen et al., 2014). From this general perspective, Petersen et al. (2012) also show that the perceived level of effort to find work on the part of welfare recipients affects the emotions of compassion and anger felt by individuals and that these emotions in turn affect their opinions about welfare policies.

An activation of authoritarian traits does not imply that one should expect higher scores on the authoritarian scales themselves. Authoritarianism is not an attitude; it is a general disposition that affects attitudes and the level of influence on them can vary according to its activation. For example, Knuckey and Hassan (2020) have recently used data from the American National Election Study since 1992 to assess the impact of authoritarianism on support for Donald Trump in the 2016 election. The authors find that the trait had more influence among whites in 2016 than in any other presidential election since 1992. However, the authors do not report significant movements in the authoritarianism scores obtained in each of the elections. Authoritarianism scores were not higher in 2016, but they were more strongly linked to support for Trump than they have been for any candidate since 19921.

The questions used to measure the trait are related to values about to child rearing, which has the benefit of avoiding explicit associations with political objects and remaining relatively stable over time. As mentioned above, the exact nature of authoritarian traits remains a matter of debate in political psychology. Some scholars argue that the disposition is not stable enough to be considered a personality trait (see Asendorpf and Van Aken, 2003; Van Hiel et al., 2004; McAdams and Pals, 2006; Sibley et al., 2007). However, the fact remains that the trait is widely considered to be causally antecedent to political attitudes.

An activation of authoritarian traits should therefore not be expected in the simple increase of the authoritarianism scores themselves, but should be assessed by analyzing the influence exerted by the trait on attitudes. In this article, we will therefore evaluate the influence of authoritarian dispositions on three measures related to the perceptions of welfare recipients. Starting from a simple thermometric measure, we will provide a depiction of public generosity toward welfare recipients before demonstrating how various groups are perceived to be deserving of financial help in the specific context of the Covid-19 crisis. The first two measures are longitudinal and therefore allow us to assess whether the link between these measures and authoritarian traits has changed between the two waves. The third measure is more specifically associated with the Covid-19 crisis and aims to evaluate the effect of authoritarianism in this context when it is more clearly highlighted.

As we have already discussed, authoritarianism is related to negative opinions of marginalized groups. Since welfare recipients are indeed marginalized, we would expect authoritarianism to be related to more negative opinions about them. We would also expect these negative opinions to be even stronger for welfare recipients who are deemed undeserving. Being considered fit for work, as opposed to being considered medically unfit, should provide an important deservingness heuristic influencing perceptions. Given that welfare recipients who are deemed fit for work may be viewed as cheaters, we would expect individuals with higher authoritarianism dispositions to hold very negative opinions about them.

The COVID-19 crisis is simultaneously an unprecedented shock and an unusual economic and health threat to hundreds of millions of people. In the context where the recent literature clearly establishes the links between the activation of authoritarian traits and perceived threat, studying the impact of the Covid-19 health crisis on the activation of authoritarianism is of obvious interest. This crisis also raises important issues related to social solidarity, as an activation of authoritarian traits produced by the pandemic is highly likely to have affected the link between authoritarianism and attitudes toward welfare recipients.

The pandemic is particularly likely to have affected more directly the attitudes associated with distributive policies because their importance acquires a salience that they did not have until then. The circumstances surrounding the Covid-19 crisis have thus brought to the forefront the crucial role played by states in building and organizing social supports that directly affect the well-being and security of individuals. The health crisis also undoubtedly placed many citizens in situations of vulnerability they had never before experienced. While many may have developed empathy for people finding themselves in vulnerable situations through no fault of their own, others may have seen new pressures on limited collective resources and developed even more negative views of welfare recipients seen as consumers and never contributors to collective resources.

Moreover, the Covid-19 pandemic has been an important external shock that may have shifted people's perceptions about the stability of the social order. As most governments implemented expensive measures aiming to provide economic and social support to their populations, we can hypothesize that many citizens perceived higher levels of threat, and that individuals who receive welfare support while being perceived as “non reciprocators” (i.e., “cheaters”) could be viewed more negatively than they typically would. It is reasonable to expect that this new environment of increased threat activates authoritarian dispositions, and leads to harsher views about welfare recipients deemed undeserving.

4. Data and Context

On March 13, 2020, the Quebec government declared a health emergency and announced the closure of schools and daycares. The Quebec government then implemented increasingly restrictive health measures that began to be phased out on May 4 outside the Montreal area, and on May 25 in Montreal. Schools and daycares were reopened on May 11 outside the Montreal area, and on June 1 in Montreal. Restaurants were reopened on June 15 outside the Montreal area, and later on June 25 in Montreal. Mandatory masking in closed public places was introduced on July 18 and new health measures were implemented again starting in the fall of 2020, as a second wave of Covid-19 cases hit the province.

Significant economic assistance measures were deployed by the federal government as part of the emergency economic plan. The most visible measure was the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERP), which made a taxable benefit of $2,000 per month quickly available to all Canadians citizens who earned $5,000 or more during the year and were left without a salary due to the health crisis. The measure was extended to seasonal workers and students over the summer, providing them with a benefit of $1,250 per month. Other important measures were put in place to support businesses affected by the pandemic to help them maintain employment ties with their employees. The Canada Emergency Wage Subsidy provided compagnies that had experienced sufficient drops in revenue with a subsidy equivalent to 75% of their employees' wages. Other measures to help businesses ensure that they had sufficient liquidity to meet their obligations were also put in place.

As part of a project on Quebeckers' attitudes toward welfare recipients, a representative sample of 2,054 adults from Quebec (Canada) was first interviewed using an online questionnaire fielded in August 2019. In this first stage of research, respondents were asked various questions related to their opinions about welfare recipients and welfare programs. In the first two weeks of June 2020, as the lockdown measures were starting to be lifted, a representative sample of 2,060 respondents filled an online survey asking various questions about welfare recipients, and the Covid-19 pandemic. One thousand one hundred and seventy eight respondents in this second survey had previously participated in the first stage conducted in 2019, allowing us to compare their attitudes at both time points and examine whether or not any change occurred.

This design allows to compare two representative samples of Quebec's population and track a fair amount of the same individuals before and right after the shock of the first wave of the Covid-19 pandemic in Quebec. Although the data only permit descriptive analysis and cannot lead to firm conclusions about the potential causal impacts of the Covid-19 crisis on authoritarianism activation levels, this descriptive work remains highly relevant. While it is indeed possible that other unobserved factors drive any differences that we may observe in opinions between the two waves, it has to be acknowledged that the pandemic situation and the various confinement measures that were implemented to control the spread of the virus were the most important external shock potentially impacting citizens' opinions. Hence, while we do not claim that our design allows for straightforward causal inference, we nonetheless argue that the general context in which the two waves of the surveys were held leads to descriptive analysis of very high relevance for understanding the potential impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic on citizens' opinions.

Although European studies are progressively more numerous, research on authoritarian dispositions still remains predominantly American. Our data therefore shed new light by focusing on authoritarian traits in a context in which it has been little studied overall. Social assistance policies are adopted at the provincial level in Canada. They are embedded in the cultures, history and political debates of each province (Béland and Daigneault, 2015). A large body of literature presents the specificity of Quebec's welfare system (Vaillancourt, 2012; van den Berg et al., 2017). Our results enrich this work and open avenues for research in other contexts on the links between the activation of authoritarian traits, large-scale crises, and attitudes toward welfare recipients.

In both waves, authoritarianism was measured using three items tapping respondents' preferences about parenting styles. Respondents were asked the following : “Here are some qualities that children can be encouraged to learn. Which one do you think is more important?” The first set of options was “Independence” or “Respect for authority”; the second questions asked to choose among “Obedience” or “Self-reliance”; and the last questions asked to choose either “Curiosity” or “Good manners.” For each item, the authoritarian options were coded as 1, and the non-authoritarian options as 0. We then used the standard approach and computed the sum of the three items to calculate each respondents' authoritarianism score (see Feldman and Stenner, 1997; Feldman, 2003). Authoritarianism scores did not appear to have significantly moved between the two waves. Focusing only on respondents who participated in both waves, the mean authoritarianism score in wave one was 1.36 (sd = 0.96) compared to 1.24 (sd = 1), a non-significant difference.

First, we will analyze how authoritarian traits are associated with simple thermometric scores for welfare recipients. Although these measurements are very useful, they remain limited, and can hardly on their own provide a detailed understanding of the perceptions of a social group. In order to assess the impact of authoritarian traits using a more specific measure, we will turn to a variable measuring the monthly assistance respondents attributed to various types of welfare recipients. This measure, which is particularly well suited to the situation of monetary assistance granted to welfare recipients, makes it possible to quantify on a commonly interpretable scale the level of assistance deemed appropriate, while simultaneously providing the tools to evaluate the links between generosity and authoritarian traits. Finally, we will turn to a measure that evokes more explicitly the deservingness of people receiving social assistance in the specific context of the Covid crisis. This will be used to evaluate the role of authoritarianism in the prioritization of groups deemed deserving of assistance during the crisis. Descriptive statistics of all the main variables used in this article are reported in Supplementary Table 1.

5. Thermometer Ratings in 2019 and in the Summer of 2020

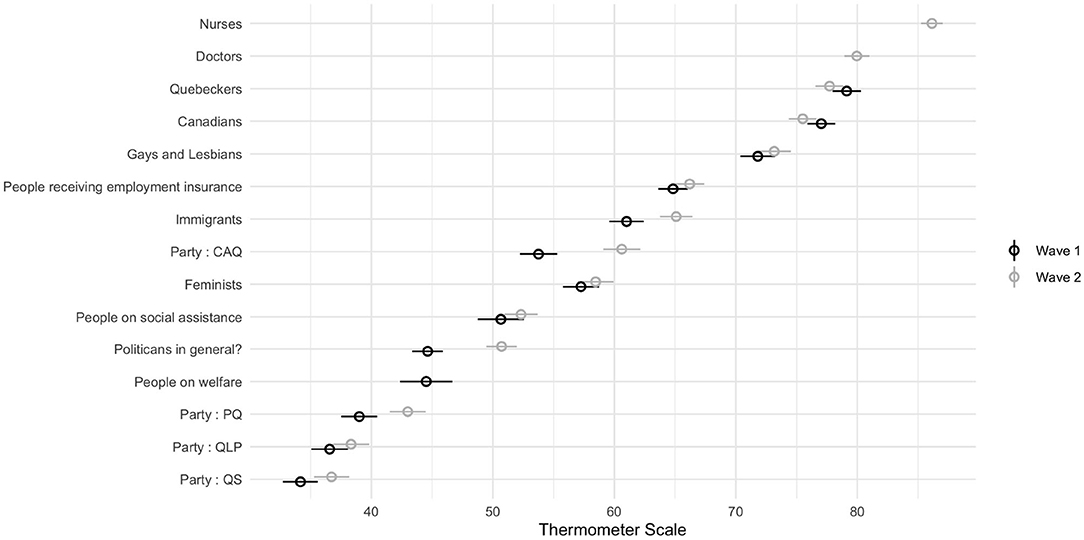

In order to get a first grasp of the data, Figure 1 displays the mean thermometer rating along with the 95% confidence intervals for each group that respondents were asked to evaluate. Doctors and nurses were added to the list in the second wave because these professions have quite obviously been brought to the forefront during the pandemic. Additionally, in wave 1 we wanted to test whether the labeling of people receiving social assistance affected their average thermometer rating. Hence, wave 1 respondents were randomly assigned to give a thermometer score for either “people on social assistance” or “people on welfare”2. No such experiment was included in the second wave and all respondents were asked to rate “people on social assistance.”

Figure 1. Thermometer ratings of various groups in waves 1 and 2. The figure displays average thermometer ratings for each target group along with the 95% confidence intervals, for each wave of the survey. In the second wave, Doctors and Nurses were added to the list of groups to be evaluated. The second wave did not include a randomized assignment to evaluate whether “People on social assistance” or “People on welfare,” only the former was presented to respondents.

Finally, a few words about the provincial political parties depicted in the figure. The Coalition Avenir Quebec (CAQ) is the party currently in power, having won office for the first time in 2018. It is a center-right party that has newly emerged as a party capable of rallying enough voters to produce a majority government. The Quebec Liberal Party (QLP) is a center party (moving left from a more center-right position in the past) and has been in power for most of the past two decades, except for a brief 18-month hiatus in 2012 and 2013 when power was held by a minority government of the Parti Québécois (PQ). The PQ is a historically important party in Quebec, since it has been advocating Quebec's independence from the rest of Canada for the last five decades. It has held power on several occasions in recent history, but has lost a great deal of support in the last 10 years. The PQ is typically seen as center-left coalition, but the party has recently also taken more conservative positions on identity issues, coming closer to the CAQ on these matters. Finally, Québec solidaire (QS) is a left-wing party that is officially sovereigntist and takes positions that are generally considered more favorable to cultural diversity.

A few interesting results emerge. First, doctors and nurses were unsurprisingly the two most appreciated groups in wave 2. Second, apart from the various political parties, people on social assistance were among the least appreciated group, scoring slightly above “politicians in general” in wave 1, and receiving about the same score as politicians in wave 2, in which the latter increased their ratings from the first wave. Third, we did not observe a substantial difference in the average thermometer ratings received by people on social assistance between the two waves. With the exception of the four political parties for which movement was to be expected, most of the groups assessed in the two waves remained relatively stable. Yet, we nonetheless observed significant increases in the appreciation of politicians in general, and of immigrants; possibly as a result of the importance of both of these groups in the pandemic response. Politicians, of course, have been at the forefront of the public response to the crisis, but many television news stories, newspaper articles, and public speeches by politicians themselves have acknowledged and expressed gratitude for the important role played by immigrants and refugees who have worked as orderlies, bringing them into direct contact with patients. In any case, these univariate distributions indicate that movement between waves 1 and 2 was indeed detectable for some groups, but no such movement occurred for thermometer scores of people on social assistance.

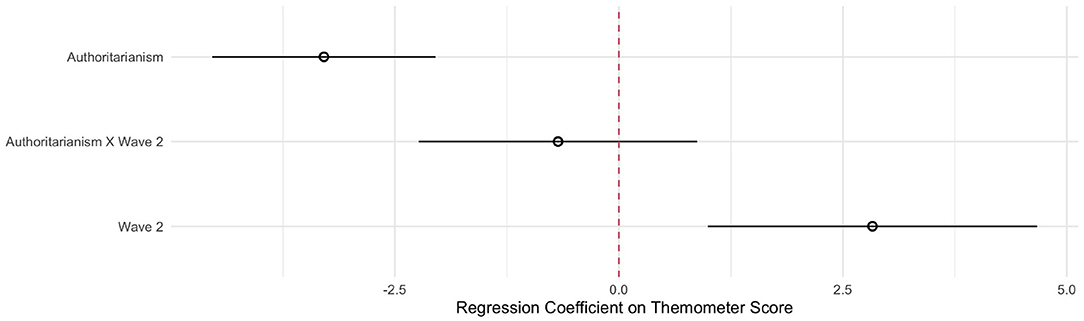

Now turning to multivariate analysis, Figure 2 displays the results of a linear model regressing the thermometer score obtained by people on social assistance on a standardized authoritarianism scale, a wave two dichotomous indicator, and the interaction between the two. We also conditioned the model on sex, age, respondents' mother tongue, as well as income and education levels. Since wave 1 included a randomly assigned wording to designate the group, the model is specified with a dichotomous indicator capturing the specific effect of that treatment on respondents' scores.

Figure 2. Thermometer ratings of people on social assistance—OLS regression. The figure displays the three coefficients of interest along with the 95% confidence intervals. The model conditions on sex, age, respondents' mother tongue, income and education levels, and includes a dichotomous indicator capturing the randomly assigned wording for “people on welfare” or “people on social assistance” in wave 1. Clustered standard errors are used to account for the fact that some respondents participated both in waves 1 and 2. The full results are available on Supplementary Table 2 (model 1).

The results indicate that, conditioned on the other variables in the model, authoritarianism was negatively related to the thermometer appreciation received by welfare recipients. Converting the standardized scale back to the original raw score, a one-point increase on the authoritarianism scale was associated with a significant decrease of the thermometer score of about 3.3 points. The coefficient for the second wave indicator suggests that, conditioned on other variables, the thermometer scores were higher by about 2.8 points in the summer 2020 compared to 2019. Finally, the interactive term between authoritarianism and the second wave indicator clearly indicates that authoritarianism was not related to additional change in thermometer scores received by people on social assistance between waves one and two. This suggests that authoritarianism did not have more or less of an impact on thermometer ratings in wave two than it did in wave one. Hence, individuals who scored higher on the authoritarianism scale did tend to have more negative views of people on social assistance, but apparently their opinion had not been impacted by the pandemic.

In order to more directly test whether potential perceived threat resulting from the pandemic affected opinions, we asked all respondents in the second wave to indicate how affected they had been by the pandemic compared to others around them3. Respondents had to choose whether they had been affected much more (coded 2), a little more (coded 1), about as much (coded 0), a little less (coded −1), or much less than others (coded −2). Arguably, those who perceived to have been the most impacted by the pandemic were also likely to feel the most threatened by the situation. This threat should in turn have increased the impact that authoritarianism had on their opinions. A similar model estimated using only the data from the second wave and interacting authoritarianism with this variable leads us to conclude that it did not (the full results are available on model 2 in Supplementary Table 2). Respondents who had higher authoritarianism score in the second wave and who perceived to have been more impacted than others by the pandemic did not have a significantly different thermometer appreciation of people on social assistance.

It is expected that the longitudinal modeling strategy used here will capture change both at the aggregate and at the individual levels, since a significant portion of the sample participated in both waves. Thus, unless change followed a particularly unconventional pattern, the model should adequately capture the presence of individual change. However, we wanted to ensure that the results remained unchanged if we estimated the model using only respondents who participated in both waves and if we used the change in thermometer scores between wave 1 and wave 2 as the dependent variable. Given the random assignment of a more negative characterization of welfare recipients in Wave 1, we estimated these models separately for respondents who received the negative characterization in Wave 1 and those who were asked to give a score on a more neutral characterization. The results, which are reported in Supplementary Table 3, show that authoritarianism was associated with a significant change in thermometric scores between waves 1 and 2 only among respondents who received a negative characterization at wave 1. Individuals with higher authoritarianism scores in wave 1 who were attributed to the negative characterization of welfare recipients gave significantly higher thermometric scores in Wave 2 when faced with a more neutral characterization. No change was observable among those who had to give a thermometric score for the same characterization. We interpret these results as supporting that authoritarianism was not associated with any real change in the thermometric scores of welfare recipients between waves 1 and 2.

6. Generosity for People on Social Assistance in 2019 and During the Covid-19 Pandemic

Thermometer ratings are a valuable tool to measure and compare people's attitudes toward various groups, but when it comes to assessing perceptions of how generous society should be toward individuals in need, the amount of money that citizens think is appropriate to help those in need provides an opportunity to quantify opinions using a continuous scale that can be interpreted on a common metric. In both waves, we asked respondents to indicate how much money they thought four types of households should receive in social assistance payment every month: we asked the question for a family of two adults and two children in which the adults were deemed unfit to work; for a family of four in which the adults were able to work; for an individual living alone and fit to work, and for individual living alone and unable to work.

Additionally, in order to test other hypotheses which are not the focus of this article, these questions were preceded by a small preamble that included a randomized assignment. In wave 1, some respondents saw a preamble that included the phrase “Keep in mind that the income needed to cover basic needs in Quebec is estimated at $1,500 a month, for a single person,” others did not see that information. In wave 2, all respondents received information about the estimated minimal income, but the amount was randomly varied to be either $1,000, $1,500, $2,000, or $2,500. These anchors did influence respondents' responses in both waves, and we accounted for this in the model by including dichotomous indicators capturing these effects.

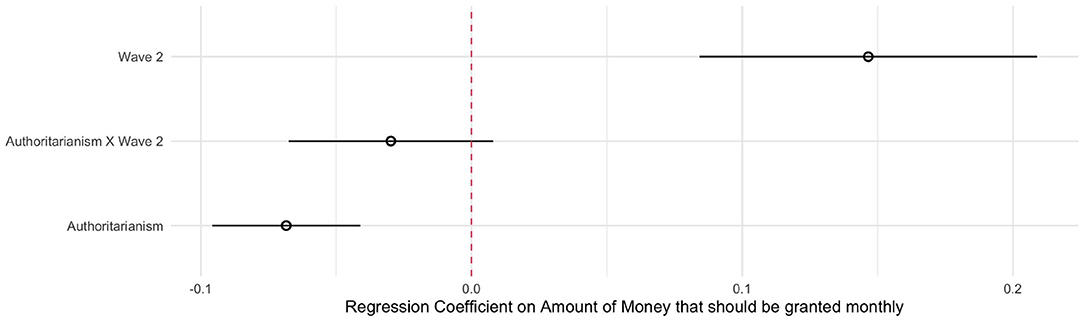

Figure 3 displays the results, focusing again on the three variables of interest. The full results are available on Supplementary Table 4. Our interest lies in the level of generosity of respondents, rather than the variation in generosity across scenarios. Therefore, a modeling strategy that conceptualizes the various scenarios as different but related trials and that aggregates these trials into a single model has the advantage of combining the common information produced by the responses obtained from these scenarios, while allowing for a more efficient use of the data than estimating separate models for each of the scenarios (see Gelman and Hill, 2007; McElreath, 2020 for more detailed explanations of this type of strategy)4. The results suggest that higher levels of authoritarianism was associated with the attribution of lower amounts of money, but that this overall tendency in the summer of 2020 did not differ in a significant way from the first wave. Overall, the results indicate that a one-point increase in authoritarianism was associated with a decrease of around $90 per month attributed to welfare recipients. Additional tests allowing the authoritarianism variable to vary by type of household leads to the same conclusion: individuals with higher authoritarianism scores were less generous, but they did not become more or less generous during the first wave of Covid-19 in Quebec than they were in 2019. Moreover, we estimated other models allowing authoritarianism to interact with the fitness to work status of the welfare recipients, and we uncovered no evidence that individuals scoring higher on the authoritarianism scale were more or less generous depending on the fitness to work status of the target group (see models 2 and 3 in Supplementary Table 4)5.

Figure 3. Amount of monthly financial aid—OLS regression. The figure displays the three coefficients of interest along with the 95% confidence intervals. The model conditions on sex, age, respondents' mother tongue. The model also includes a dichotomous indicator capturing the randomly assigned anchors specifying various monthly amounts of money (No mention, $1,500, $2,000, $2,500) supposedly established as requirements to cover minimum costs of living. Since the model is pooled across 4 questions related to different scenarios (Family of two adults able to work living with their two children, Family of two adults unable to work living with their two children. Someone living alone and able to work, and someone living alone and able to work), we also include fixed effects to capture the influence of these scenarios. Finally, we report clustered standard errors to account for the fact that some respondents participated both in waves 1 and 2. The full results are available on Supplementary Table 4, and the coefficients depicted in the figure are from model 1.

Comparing opinions in 2019 and in the summer of 2020 is indeed very interesting, but we have to acknowledge that perceived threat is expected to occur because of the pandemic, but it is not directly measured. Thus, to test whether the perception of threat measured at the individual level affected the impact of authoritarian dispositions on the amounts allocated monthly to welfare recipients, the variable measuring respondents' perceptions of the level of impact that the crisis had on their lives was used. A model similar to the others was estimated using only second-wave data and including an interaction term between authoritarianism and perception of the level of impact the crisis had on one's life relative to others. The complete results are available in Supplementary Table 4 (model 4). Once again, our results show that the feeling of having been more affected than others had no influence on the relationship between authoritarian dispositions and the monthly amounts allocated.

We again wanted to ensure that an intra-individual change did not remain undetected in the aggregate. Therefore, we estimated similar regression models using only respondents who participated in both waves and using the change in monthly amount awarded between waves 1 and 2 as the dependent variable. These models are reported in Supplementary Table 5. Again, the results confirm that authoritarianism was not associated with a change in attitudes toward welfare recipients.

7. Opinions About How Deserving Are Various Groups in the Covid Context

So far, we have looked at thermometer ratings received by welfare recipients before and during the first wave of the pandemic. We have also analyzed respondents' level of generosity toward them, and again compared that generosity before and during the crisis. Yet, we did not directly ask respondents to state their opinions using questions referring to the specific context of the Covid-19 pandemic. Hence, although it is likely that the pandemic was very much in the respondents' minds during the second wave, the questions that we have analyzed so far did not specifically elicit that specific situation to the respondents' attention.

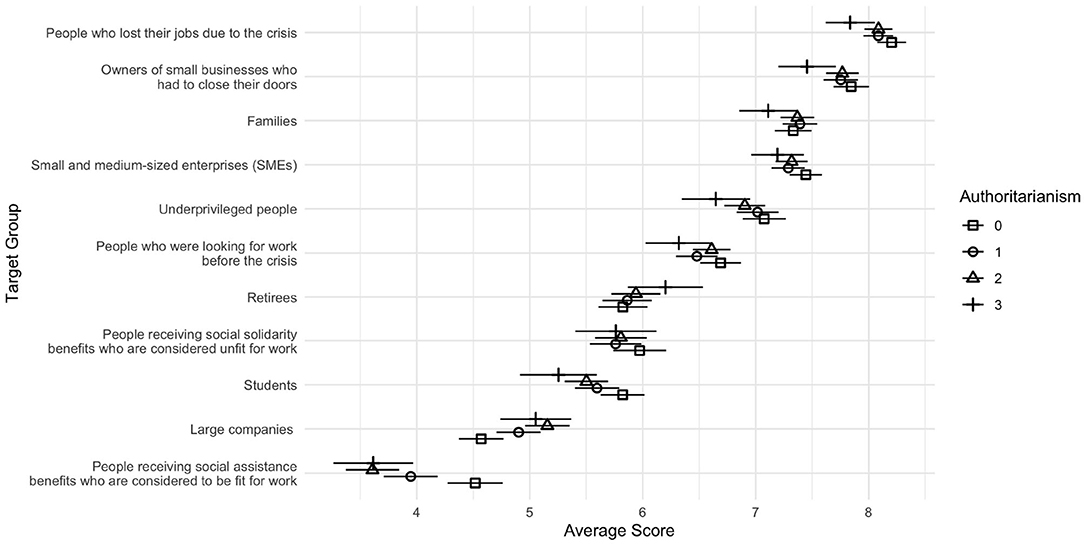

In order to test whether a more direct allusion to the pandemic affected opinions, we asked respondents in the second wave to use a scale from 0 to 10 to indicate how much additional help various groups should receive in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic6. Figure 4 displays the average score obtained by each group along with 95% confidence intervals for all authoritarianism levels.

Figure 4. Deservingness of Help to various groups, by authoritarianism score. The figure displays average score for each target group along with the 95% confidence intervals, by authoritarianism level.

First, we notice that although respondents with high levels of authoritarianism tended to attribute lower scores and that respondents with low authoritarianism levels tended to give higher scores, there was an overall agreement among Quebeckers about the general ordering of the groups. Second, those who were deemed to be the least deserving were people receiving social assistance benefits who are fit for work. Although clearly not a top priority in the respondents' opinion, welfare recipients who are unfit for work received significantly higher scores. It is likely that this discrepancy between fit and unfit for work welfare recipients can be attributed to an effort based deservingess heuristic positioning those fit for work as cheaters who are benefiting from the system without contributing to it (see Petersen et al., 2012).

To evaluate whether authoritarianism was associated with a significant difference in scores given to welfare recipients who are fit or unfit for work once we conditioned on age, sex, and mother tongue, education, and income, we pooled responses obtained by the two groups and estimated a linear regression model that included an interaction term between authoritarianism and the fitness for work status of the group evaluated (the full results are available in model 1 of Supplementary Table 6). Given that responses were nested within respondents, clustered standard errors were used.

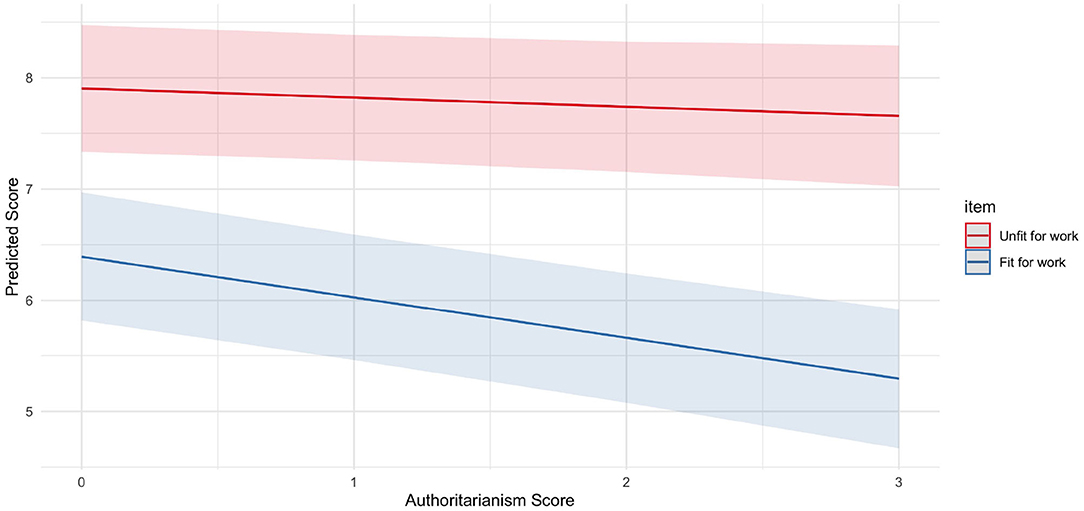

Figure 5 displays the predicted scores obtained by people receiving social assistance benefits depending on their fitness for work status and by authoritarianism level. Two results are apparent. First, welfare recipients deemed unfit for work received significantly higher scores than those who were presented as fit, which was expected given what we have already seen on Figure 4. Second, authoritarianism was significantly related to lower deservingness scores for individuals fit for work, but not for those deemed unfit. Respondents low in authoritarianism gave an average deservingess score of about 4.9 to welfare recipients who were fit for work, this score decreased to about 4 for respondents with high authoritarianism level.

Figure 5. Deservingness of help by fitness for work and authoritarianism score. The figure displays predicted score for welfare recipients who are fit and unfit for work by respondents' level of authoritarianism. The full results are available in Supplementary Table 6, the predicted scores are calculated from model 1. Clustered standard errors were used to account for the nesting of the responses within individuals.

This finding suggests that in the context of Covid-19, authoritarianism was associated with less positive opinions about welfare recipients who are deemed fit for work. Yet, this finding mostly highlights that authoritarianism was related to more negative views about welfare recipients who were fit for work. That this was the case in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic is interesting, but it does not indicate that the pandemic itself was producing such an effect by activating authoritarianism. To test more directly whether perceived threat moderated the relation between authoritarianism and the opinions about welfare recipients depending on their fitness to work status, we yet again used respondents' self-evaluations of the impact that the crisis had on their lives compared to others (model 2, Supplementary Table 6). Estimating a similar model including a triple interaction between that perception, authoritarianism and the fitness to work dichotomous indicator, we again found no evidence that the perception of having been more affected than others moderated this relation.

8. Conclusions

This paper has looked at the evolution of attitudes toward welfare recipients and the impact of authoritarian dispositions on these attitudes in the context of the Covid-19 health crisis. We used two representative surveys, the first (n = 2,054) conducted in the summer of 2019 and the second (n = 2,060) near the end of the first wave of the Covid-19 pandemic in Quebec in June 2020. One thousand one hundred and seventy eight participants in the second survey had also participated in the first, allowing us to analyze the potential movement in many of the same individuals. Overall, while our results clearly indicate that authoritarian dispositions are associated with more negative views of welfare recipients, the shock associated with the pandemic does not appear to have affected the relationship between these attitudes and authoritarian traits.

We first looked at the comparison of the thermometric scores received by people on social assistance in 2019 and during the health crisis in 2020. The results show that authoritarianism was associated with lower appreciation scores, but it was not associated with a change in these scores between the two waves. Furthermore, a more direct measure capturing the perceived threat associated with the crisis did not allow us to conclude that authoritarianism and perceived threat had an interactive influence on the thermometric appreciation scores.

Turning to Quebecers' perception of the appropriate level of monthly assistance to be offered to people on social assistance, we again found that authoritarianism was associated with lower overall generosity, but not with a change in the levels of assistance deemed adequate between the first and second waves. Nor do our data allow us to conclude that authoritarianism interacts with fitness for work status, which is likely to be strongly associated with deservingness heuristics, to influence the level of generosity of Quebecers. The level of perceived threat measured more directly did not, once again, prove to be a factor affecting the relationship between attitudes and authoritarianism.

Finally, by looking more directly at Quebecers' opinions regarding the different groups perceived as deserving help in the specific context of the health crisis, our results show that people on social assistance were clearly not considered a priority group. Authoritarianism was associated with perceptions that welfare recipients were less deserving of help. Our results also indicate that individuals with higher authoritarian traits judged welfare recipients who were fit for work even more harshly, suggesting that fitness for work acted as a strong deservingness heuristic among individuals with higher authoritarian dispositions. This last result also illustrates how individuals with higher scores of authoritarianism were also particularly sensitive to deservingness cues in their assessment of welfare recipients. This sensitivity makes it all the more surprising that a shock as important as that of the Covid-19 crisis did not affect their opinion of welfare recipients.

While recent research has clearly shown the importance perception of threat in the activation of authoritarian dispositions, skepticism toward the health measures put in place during the pandemic crisis seems to have been in many places associated with individuals particularly likely to have high authoritarianism scores. This apparent contradiction between the importance of perceived threats and the reactions observed in several places will no doubt allow us to better specify the links between threats and the activation of authoritarian dispositions. One could, for example, speculate that real threats that are more abstract or less directly associated with identifiable individuals or groups are less likely to activate authoritarian traits. Our results demonstrate that the shock of the pandemic crisis did not affect the relationship between authoritarian dispositions and distributive politics.

These conclusions come in a context where previous work has shown that Quebecers greatly overestimate the costs of welfare programs; that about one in two do not thin that funding for these programs should be increased even after being informed of their real costs; and that fitness for work—which is demonstrated in this article to be associated with a deservingness heuristic in people with authoritarian traits—is understood primarily through a medial, not a social, lens. That authoritarianism is related to perceptions about welfare recipients was to be expected, but the fact that a contextual shock as important as the Covid-19 pandemic did not influence attitudes is perhaps more surprising given that it is quite clear that the situation should have heightened perceptions of threats in the population. This calls for further research to better how perceived threats and authoritarianism are related and whether this relationship actually holds for most attitudes.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Le Comité d'éthique de la Recherche, Université Téluq. Participants voluntarily agreed to participate in the study.

Author Contributions

AB had the original idea, did the statistical analysis, and wrote the majority of the manuscript. NL contributed to the writing and ideas, provided funding for the data collection, and served as the principal investigator of the research project that hosted this study. Both authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This research was funded by the Social Science and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC), award number 892-2018-2003.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2021.660881/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^Exploratory analyses show that authoritarian dispositions influence the electoral choices of Quebecers, but that their influence remained stable between the two waves.

2. ^In French, the exact wording was, respectively, “Les personnes assistées sociales,” and “Les gens sur le bien-être social (les «BS»)?,” which is arguably much more evocative than what is possible in English. The expression “BS” is a well-known slur used in Quebec to express lack of respect or consideration for people receiving welfare support.

3. ^The exact question was: “Comparing yourself to people around you, how much would you say that the Covid-19 crisis affected you? Select the statement that most closely matches what you think.”

4. ^Given that the model pools together responses to four different scenarios repeated in two waves, this could also have been modeled using multilevel strategy. Yet, because the number of groups remains relatively small, the benefits of using a multilevel model appeared minimal (see Gelman and Hill, 2007, p. 247).

5. ^Note that these model include a triple interaction which typically has to be done with caution. We have also estimated the models separately on the four different household types rather than pooling them all together, the results lead to the same conclusions.

6. ^The exact wording was : “The Covid-19 crisis affects several groups of people. For each of the following groups, indicate how you think the group should be supported by governments during the Covid-19 crisis. Use a scale from 0 to 10, where 0 means that the group should not receive any special help and 10 means that the group should receive much help.”

References

Adorno, T. W., Frenkel-Brunswik, E., Levinson, D. J., and Sanford, R. N. (1950). The Authoritarian Personality. New York, NY: Harpers.

Aichholzer, J., and Zandonella, M. (2016). Psychological bases of support for radical right parties. Pers. Individ. Differ. 96. 185–190. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2016.02.072

Arikan, G., and Sekercioglu, E. (2019). Authoritarian predispositions and attitudes toward redistribution. Polit. Psychol. 40, 1099–1118. doi: 10.1111/pops.12580

Asendorpf, J. B., and Van Aken, M. A. G. (2003). Personality–relationship transaction in adolescence: core versus surface personality characteristics. J. Pers. 71, 629–666. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.7104005

Barker, D. C., and Tinnick, J. D. (2006). Competing visions of parental roles and ideological constraint. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 100, 249–263. doi: 10.1017/S0003055406062149

Béland, D., and Daigneault, P.-M. (2015). Welfare Reform in Canada: Provincial Social Assistance in Comparative Perspective. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press.

Brandt, M. J., and Henry, P. J. (2012). Gender inequality and gender differences in authoritarianism. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 38, 1301–1315. doi: 10.1177/0146167212449871

Brandt, M. J., and Reyna, C. (2014). To love or hate thy neighbor: the role of authoritarianism and traditionalism in explaining the link between fundamentalism and racial prejudice. Polit. Psychol. 35, 207–223. doi: 10.1111/pops.12077

Brown, R. (2004). “The authoritarian personality and the organization of attitudes,” in Key Readings in Social Psychology. Political Psychology: Key Readings, eds J. T. Jost and J. Sidanius (Psychology Press), 39–68. doi: 10.4324/9780203505984-2

Coughlin, R. (1980). Ideology, Public Opinions and Welfare Policy: At! Titudes Toward Taxes and Spending in the Industrial Societies. Institute of International Studies Research Series 42. Berkeley, CA: University of California.

Doty, R. M., Peterson, B. E., and Winter, D. G. (1991). Threat and authoritarianism in the United States, 1978–1987. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 61:629.

Duckitt, J. (1989). Authoritarianism and group identification: a new view of an old construct. Polit. Psychol. 63–84.

Duckitt, J. (1992). Threat and authoritarianism: another look. J. Social Psychol. 132, 697–698. doi: 10.1080/00224545.1992.9713913

Duckitt, J. (2001). “A dual-process cognitive-motivational theory of ideology and prejudice,” in Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, ed M. P. Zanna (San Diego, CA: Academic Press), 41–112.

Dunn, K. (2015). Preference for radical right-wing populist parties among exclusive-nationalists and authoritarians. Party Polit. 21, 367–380. doi: 10.1177/1354068812472587

Federico, C. M., Fisher, E. L., and Deason, G. (2011). Expertise and the ideological consequences of the authoritarian predisposition. Publ. Opin. Q. 75, 686–708. doi: 10.1093/poq/nfr026

Feldman, S. (2003). Enforcing social conformity: a theory of authoritarianism. Polit. Psychol. 24, 41–74. doi: 10.1111/0162-895X.00316

Feldman, S., and Stenner, K. (1997). Perceived threat and authoritarianism. Polit. Psychol. 18, 741–770. doi: 10.1111/0162-895X.00077

Gelman, A., and Hill, J. (2007). Data Analysis Using Regression and Multilevel/Hierarchical Models. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Gilens, M. (2000). Why Americans Hate Welfare: Race, Media, and the Politics of Antipoverty Policy. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Henry, P. J. (2011). The role of stigma in understanding ethnicity differences in authoritarianism. Polit. Psychol. 32, 419–438. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9221.2010.00816.x

Hetherington, M., and Suhay, E. (2011). Authoritarianism, threat, and Americans support for the war on terror. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 55, 546–560. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5907.2011.00514.x

Hetherington, M. J., and Weiler, J. D. (2009). Authoritarianism and Polarization in American Politics. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Knuckey, J., and Hassan, K. (2020). Authoritarianism and support for trump in the 2016 presidential election. Soc. Sci. J. 1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.soscij.2019.06.008

Lavine, H., Burgess, D., Snyder, M., Transue, J., Sullivan, J. L., Haney, B., et al. (1999). Threat, authoritarianism, and voting: an investigation of personality and persuasion. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 25, 337–347. doi: 10.1177/0146167299025003006

Lavine, H., Lodge, M., and Freitas, K. (2005). Threat, authoritarianism, and selective exposure to information. Polit. Psychol. 26, 219–244. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9221.2005.00416.x

Ludeke, S. G., and Krueger, R. F. (2013). Authoritarianism as a personality trait: evidence from a longitudinal behavior genetic study. Pers. Individ. Differ. 55, 480–484. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2013.04.015

McAdams, D. P., and Pals, J. L. (2006). A new big five: fundamental principles for an integrative science of personality. Am. Psychol. 61:204. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.61.3.204

McCourt, K., Bouchard, T. J. Jr, Lykken, D. T., Tellegen, A., and Keyes, M. (1999). Authoritarianism revisited: genetic and environmental influences examined in twins reared apart and together. Pers. Individ. Differ. 27, 985–1014. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(99)00048-3

McElreath, R. (2020). Statistical Rethinking: A Bayesian Course with Examples in R and Stan. New York, NY: CRC Press.

Oorschot, W. V. (2006). Making the difference in social Europe: deservingness perceptions among citizens of European welfare states. J. Eur. Soc. Pol. 16, 23–42. doi: 10.1177/0958928706059829

Parker, C. S., and Towler, C. C. (2019). Race and authoritarianism in American politics. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 22, 503–519. doi: 10.1146/annurev-polisci-050317-064519

Petersen, M. B. (2012). Social welfare as small-scale help: evolutionary psychology and the deservingness heuristic. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 56, 1–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5907.2011.00545.x

Petersen, M. B., Aarøe, L., Jensen, N. H., and Curry, O. (2014). Social welfare and the psychology of food sharing: short-term hunger increases support for social welfare. Polit. Psychol. 35, 757–773. doi: 10.1111/pops.12062

Petersen, M. B., Slothuus, R., Stubager, R., and Togeby, L. (2011). Deservingness versus values in public opinion on welfare: the automaticity of the deservingness heuristic. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 50, 24–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6765.2010.01923.x

Petersen, M. B., Sznycer, D., Cosmides, L., and Tooby, J. (2012). Who deserves help? Evolutionary psychology, social emotions, and public opinion about welfare. Polit. Psychol. 33, 395–418. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9221.2012.00883.x

Rickert, E. J. (1998). Authoritarianism and economic threat: implications for political behavior. Polit. Psychol. 19, 707–720. doi: 10.1111/0162-895X.00128

Sibley, C. G., Wilson, M. S., and Duckitt, J. (2007). Effects of dangerous and competitive worldviews on right-wing authoritarianism and social dominance orientation over a five-month period. Polit. Psychol. 28, 357–371. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9221.2007.00572.x

Vaillancourt, Y. (2012). “The Quebec model of social policy, past and present, in Canadian Social Policy. Issues and Perspectives, eds A. Westhues, and B. Wharf (Waterloo, IA: Wilfrid Laurier University Press), 115–144.

van den Berg, A., Plante, C., Hicham, R., Proulx, C., and Faustmann, S. (2017). Combating Poverty: Québec's Pursuit of a Distinctive Welfare State. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press.

Van Hiel, A., Pandelaere, M., and Duriez, B. (2004). The impact of need for closure on conservative beliefs and racism: differential mediation by authoritarian submission and authoritarian dominance. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 30, 824–837. doi: 10.1177/0146167204264333

Keywords: authoritarianism, welfare recipients, perceived threat, deservingness heuristic, attitude change, Covid-19

Citation: Blanchet A and Landry N (2021) Authoritarianism and Attitudes Toward Welfare Recipients Under Covid-19 Shock. Front. Polit. Sci. 3:660881. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2021.660881

Received: 29 January 2021; Accepted: 07 April 2021;

Published: 12 May 2021.

Edited by:

Scott Pruysers, Dalhousie University, CanadaCopyright © 2021 Blanchet and Landry. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Alexandre Blanchet, YWxleGFuZHJlLmJsYW5jaGV0QGVuYXAuY2E=

Alexandre Blanchet

Alexandre Blanchet Normand Landry

Normand Landry