94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Polit. Sci., 07 May 2021

Sec. Elections and Representation

Volume 3 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2021.660088

This article is part of the Research TopicIntergroup Dynamics and Electoral PoliticsView all 6 articles

The far right typically performs worse in local elections than in national ones. We propose that a key reason for this underperformance is the difference in how intergroup attitudes manifest and are informed in local and national settings. We document the existence of a local-national gap in intergroup attitudes through survey experiments and open-ended survey questions that randomly vary whether study-participants are asked about the national or the local setting. In the first experiment, we find a substantial local-national gap, where the influx of refugees during the refugee crisis was seen as instigating changes in the national setting, but rarely locally. In the second experiment, we investigate the perceived amount and nature of public discussions about refugees and immigration. We again find a substantial local-national gap. Compared to discussions in the local setting, there is a perception of more discussion in the national setting, and the nature of those discussions are perceived as more heated, conflictual, and biased than local discussions. We also find a local-national gap in information sources about refugees and immigration in a final study. In local questions, native citizens are more likely to rely on everyday experiences and social networks. In national questions, they are more likely to rely on media representations. These local-national gaps are seen in urban, suburban, and rural areas. Importantly, we also find the gap among respondents who had an asylum seeker center established in their local community recently. The local-national gaps in intergroup attitudes revealed here can account for patterns in far-right electoral performance that so far have remained puzzling, and they deserve further attention in future research both in political science and social psychology.

How come far-right parties are less successful electorally in local elections than in national ones? This is a puzzle that has received less attention than it deserves in the now voluminous literature on the far right, (e.g., Mudde, 2007; Kriesi et al., 2008; Norris and Inglehart 2018; Ivarsflaten et al., 2019). In studies focused on national elections, it is now agreed that intergroup attitudes, and in particular opposition to immigration and policies to help the inclusion of immigrant-origin minorities, are central to voters of the far right (de Lange, 2007; Ivarsflaten, 2008; Ivarsflaten and Sniderman, 2021). Here we argue that to account for the local-national gap in far-right electoral outcomes we need to take into consideration an aspect of these intergroup attitudes that so far is not well recognized and understood. We will argue that natives relate differently to questions concerning immigration and immigrants when they refer to the local community than when the reference point is the national setting. This is, we propose, a missing link in existing theories that seek to explain the observed local-national gap in electoral outcomes for the far right.

We show that there exists a substantial local-national gap in public opinion about immigrants and immigration in three survey experiments conducted in the aftermath of the 2015 European refugee crisis. The first experiment focuses on perceptions of change as a result of a sudden influx of refugees with reference to either the country or to the local community. The second study investigates perceptions about the public debate concerning refugees and immigration either in the national or the local setting. The third experiment asks about sources of information in questions related to refugees and immigration and varies whether the question references the country or the local community. Across all three experiments we find large and robust local-national gaps consistent with the account we advance.

There is by now an extensive line of research on the far right and their voters (Norris and Inglehart, 2018; Ivarsflaten et al., 2019; Kriesi et al., 2008; Mudde, 2007; Kitschelt and McGann, 1995). Nearly all of it, even the studies that examine sub-national variation, focuses on outcomes of national elections. Some have noted that breakthroughs for the far right often have occurred first in second-order elections (Reif and Schmitt, 1980), whether local or to the European Parliament. Nevertheless, studies of far-right outcomes in local elections are sparse. The local-national gap in intergroup attitudes that is the focus of attention in this study is not widely known or studied in the literature and hence its possible implications for far-right electoral performance has not previously been highlighted.

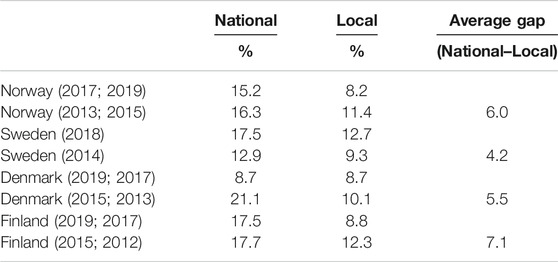

Table 1 shows that the far right consistently under-performed in local elections compared to national ones in the four largest Nordic countries—Sweden, Norway, Denmark, and Finland. We focus on these countries for a number of reasons. First, this is a part of Europe where the far right has been particularly successful in national elections. The success came first in Denmark and Norway, where the parties were formed in the early 1970s, but the far right has for the last 15 or so years been strongly prevalent also in Sweden and Finland. Second, the local-national gaps in electoral outcomes are comparable in these countries because of their similar party and election systems (Lipset and Rokkan, 1967; Bentsson et al., 2013). Also, since the party systems are nationalized and the state systems are unitary in all these Nordic countries, local elections are simultaneous and country wide. This facilitates comparison of national and local results. The survey experimental results to be reported below are conducted in one of these Nordic countries, Norway. The far right in Norway is fully institutionalized. In national elections it has been the country´s third largest party since the 1990s and onwards. It served in national government from 2013 to 2019. While some far-right parties may suffer local-national gaps in electoral performance simply because they are new and hence not fully institutionalized, this is not the case in the Norwegian context, which is the main empirical focus in this article.

TABLE 1. The local-national gap in election results for the Nordic far right. Official results from the two most recent national and local elections.

Table 1 covers the four most recent elections in each country—two national and two local ones. In Sweden, local and national elections are held simultaneously. In all the other countries they are asynchronous. The two first columns list the official results for the national and local elections respectively. The last column displays the average local-national gap in far-right electoral performance. The average gaps are calculated as the difference between the results of the two national elections (averaged) and the two local elections (averaged), for each country. All gaps are positive and larger than zero, which means that the far right in all countries on average performed better in national than in local elections. The size of this difference is around 5 percentage points, which is considerable, since the election results for these far-right parties do not rise above 21.1 percent in any of the elections covered in Table 1.1 It is also worth noting that the local-national gap in aggregate electoral performance is at least as large in the countries where the far right is fully institutionalized (Norway and Denmark, and arguably also in Finland) as in the countries where they are not fully so (most clearly in Sweden). Elsewhere in Europe there are similarly examples of fully institutionalized far-right parties, (e.g. in Austria and Switzerland) and more recently established and therefore not fully institutionalized such parties, (e.g. in Germany and the Netherlands).

Voting for the far right is strongly related to intergroup attitudes, more specifically what has been called nativism. In the standard text on the ideology of the far right in Europe, Mudde (2007, p. 19) defines nativism as “an ideology, which holds that states should be inhabited exclusively by members of the native group (“the nation”) and that nonnative elements (persons and ideas) are fundamentally threatening to the homogenous nation-state”.

There is no doubt that nativism is a potent force in today’s Europe. In the case of the Brexit referendum, where a majority voted to leave the European Union, studies have shown that concern over border control, of keeping immigrants and refugees out, was one of the reasons people voted as they did (Hobolt, 2016; Sobolewska and Ford, 2020). And while the particularities of the United Kingdom’s situation are singular, there are similarities elsewhere. In the United States, President Trump won enough votes for a majority in the electoral college after a campaign in 2016, which echoed the slogans of far-right parties in Europe in calling for “America First.” “France d’abord” had for decades been the rallying cry of the National Front in France as it had of the Austrian Freedom Party, “Österreich zuerst” (Rydgren, 2005; Mudde, 2007; Ivarsflaten et al., 2019). In Norway, Denmark, Italy, Finland, Flanders, Switzerland, and the Netherlands, far-right parties have been in or exercised substantial influence over governments for more than a decade already. Sweden and Germany appeared for a long time to be exceptions to the rule of the surge of the far right, but in recent years we have seen the establishment and growth of powerful such parties also there—Sverigedemokraterna and Die Alternative für Deutschland.

Just like the literature focusing on the far-right parties themselves and their ideologies, studies of voter patterns have repeatedly underscored the importance of nativist attitudes for far-right voters (Carter, 2005; de Lange, 2007; Ivarsflaten, 2008; Norris and Inglehart, 2018). This series of studies, and several others, have shown that voters who favor a liberal approach to border control and asylum and those who support inclusionary minority policies more generally are highly unlikely to vote for the far right. By contrast those who favor strict immigration and refugee policies and those who support exclusionary policies toward immigrant-origin minorities are more likely to vote for the far right, especially if they attach high salience to this area of politics. In other words, there is a strong link between exclusionary intergroup attitudes and the likelihood of voting for the far right.

Immigration politics is central both on the national political stage and in local political debates (Scalise and Burroni, 2020). For example, the admission and distribution of asylum seekers is one issue which puts immigration on the agenda in local politics (Blommaert et al., 2003; Zorlu 2016; Bygnes 2020). Scholars have described asylum accommodation at the local level as a “battleground” where the migration process is managed by local political and administrative authorities and agencies (Campomori and Ambrosini, 2020). Local authorities and cities may implement immigration and settlement polices which diverge from those at the national level. For example, we have seen the creation of so-called “solidarity cities” in Europe or “sanctuary cities” in North-America and the United Kingdom (Jørgensen, 2012; Barber, 2013; Augustin and Jørgensen, 2019). The research documenting the centrality of local experiences in the field of immigration politics deepens the puzzle of the local-national gap in election results for the far right. Why when nativism is so important to the far-right vote, does the far-right underperform where natives and newcomers live their everyday lives together?

We propose that an important missing piece in explanations of the local-national gap in far-right electoral performance is to be found through an improved model of intergroup attitudes. More specifically, we hypothesize that there are systematic differences in intergroup attitudes dependent on whether citizens’ focus on the national or the local setting. In the study of intergroup relations, this idea is not new but extends from an insight well known and described in the classic work by Herbert Blumer. Already in 1958, he pointed out the difference between individuals’ concrete lived experiences of intergroup contact in everyday life and the abstract image created of “the others” through collective and mediated public discourse. Addressing racial prejudice, Blumer wrote:

…the building of the image of the abstract group takes place in the area of the remote and not of the near. It is not the experience with concrete individuals in daily association that gives rise to the definitions of the extended, abstract group. Such immediate experience is usually regulated and orderly. Even where such immediate experience is disrupted the new definitions which are formed are limited to the individuals involved. The collective image of the abstract group grows up not by generalizing from experiences gained in close, first-hand contacts but through the transcending characterizations that are made of the group as an entity (Blumer, 1958, p.6, p.6)

Applying Blumer’s argument to the puzzle at hand, we argue that public views about local manifestations of immigration (as an issue “in the near”) are distinct from views on immigration as a national phenomenon (an issue “in the far”). Whereas the former is likely to be grounded in local experiences, the latter is predominately informed by the construction of the issue in the media and more broadly in the national public arena. In more recent work on construal-level theory, similar ideas are central. The distinction is usually referred to as that between low and high levels of construal, where the low level roughly corresponds to issues “in the near” (Hess et al., 2018). It follows from this line of thinking that citizens´ attitudes to immigration and immigrant-origin minorities as a local and a national phenomenon may well diverge.

If there are systematic differences in the public´s views on immigration-related phenomena in local and national settings, this can account for the observed local-national gap in far-right voting. An example of how a local-national gap would manifest and result in a premium on far-right electoral outcomes at the national level is the following: If immigrant-origin minority presence does not disrupt everyday lives considerably in the local setting, reactions may well be muted and concerns not spurred about immigration and immigrants when the focus is on the local community. By contrast, concerns may be strong if the focus is instead on the national setting, especially if national public debates and media coverage about immigration and immigrants are politicized and heated. And, according to this line of thinking, such local-national gaps in intergroup attitudes should be observable irrespective of the nature of the local community—whether it is urban or rural or has extensive experience accommodating newcomers or not. As Blumer (1958) pointed out, people’s everyday intergroup interactions in the near may well be positive, while at the same time views of out-groups can remain negative in the far.2

Empirically, we address a straight-forward question. Do citizens relate differently to immigration-related phenomena in local and national settings? Survey experiments are ideally suited for learning the answer to this question. They allow us to examine citizen opinion on immigration-related issues, while randomly varying, between subjects, only which setting is in focus3. This procedure enables observation of the hypothesized local-national gap directly, without confounders or consistency bias. Moreover, since the experiments are embedded in a larger survey, we will examine whether the local-national gap appears across citizens living in different types of local settings—urban, suburban, and rural, and having different experiences of immigrant settlement in their own communities.

We fielded three survey experiments using this procedure. They followed the same basic template. The participants were randomized into two experimental groups and received the same survey question. In all three cases the experimental “treatment” was the same. Only one small, but for our purposes all-important, part of the question differed between groups. One group was asked about the issue in the far—the national setting is in focus. The other group was asked about the issue in the near—the local setting is in focus.4

The studies were conducted in the aftermath of the 2015 refugee crisis and we first focus on perception of change due to the crisis. Our data was collected in Norway, one of the major receiving countries within the EEA in 2015 (Eurostat, 2016). A recent qualitative study from Norwegian local communities during the refugee crisis showed that people reported fewer negative experiences resulting from the establishment of ASCs than anticipated before the asylum seekers arrived (Bygnes, 2020). This finding spurred our interest in how people perceive change depending on whether they focus on the national or local setting. In Experiment 1, we asked “As you see it, has something changed in [your local community/Norway] as a result of the 2015 refugee crisis?” The participants could answer either yes or no.

Next, we examined the local-national gap in public discussions concerning refugees and immigrants. We asked our respondents to evaluate the amount and nature of discussion on refugees and immigration focusing either on Norway or on their local community. We asked: “How much would you say that issues relating to refugees and immigration are discussed in [Norway/your local community] these days?” Responses were given on a five-point scale ranging from 1 “very little” to 5 “very much.” Next, we asked the participants to describe the nature of discussions: “How would you characterize the discussions about refugees and immigration in [Norway/your local community]?” followed by four seven-point semantic differential scales (calm–heated; objective–non-objective; solution-oriented–a source of conflict; and interesting–boring).

Finally, in Experiment 3, we asked respondents for their sources of information about refugees and immigration.5 Participants were asked “How do you get information about refugees and immigration in [Norway/your local community]? They were instructed to reply in their own words.6 Their answers were coded based on a template developed from a previous study carried out in the United States which similarly used an open-ended survey format to document differences in source of information relevant to the formation of intergroup attitudes across different geographic units (Wong et al., 2012).

Data was collected in the Norwegian Citizen Panel (Ivarsflaten and team, 2018), a research-purpose online panel owned by the University of Bergen in June 2018 (Wave 12) and October 2018 (Wave 13). Participants in the NCP were recruited in waves 1, 3, 8, and 11 based on random samples drawn from the National Population Registry. The samples were limited to individuals aged 18 or older, with a current home address in Norway. Response rates for initial recruitment to the panel ranged from 15.1 to 23.0%, whereas the response rate among panel participants was 70.5 and 74.6 percent in waves 12 and 13, respectively. Compared to the population, there is some underrepresentation of individuals with lower levels of education, especially men, and younger respondents in the NCP. There are also some deviations from the population based on geographic region. These deviations are not a major concern for the study at hand since its main purpose is to investigate local-national gaps in responses from respondents in randomly created experimental groups. The total number of participants, the number of valid cases and the demographic characteristics of the samples are reported in Table 2.

The NCP is organized in such a way that all participants answer some identical core questions, and are randomized into representative subpanels that focus on specific topics, (e.g. immigration, climate change, or health). With the exception of Experiment 1, which was run in two subpanels, the experiments were embedded in one subpanel of the NCP. Experiment 1 was included in wave 12 (June 2018), whereas Experiments 2 and 3 were included in wave 13 (October-November 2018).

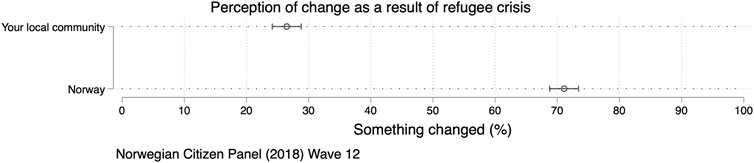

In our first experiment, we asked about perceived changes resulting from the refugee crisis. In accordance with the procedure described above we randomly assigned half of the respondents to answer this question with reference to the country. The other half was asked about the local setting. Figure 1 shows the main results from this survey experiment. It reveals an extraordinarily large local-national gap in responses. When their focus was on the national setting—the question “in the far”–as many as 71% of respondents7 perceived changes as a result of the refugee crisis. By contrast, as few as 27% perceived changes when their focus was on the local setting—the question “in the near.” This is not a narrow local-national gap, it is a wide gulf. A vast majority perceive change to have occurred when we ask them to focus on the country. Only a small minority perceive this change when we put focus on the local community.

FIGURE 1. The local-national gap in perception of change as a result of the 2015 refugee crisis. Percent of sample who perceived something had changed.

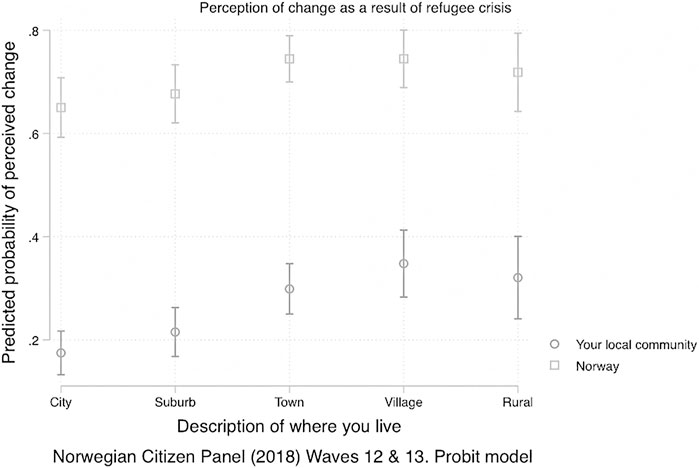

Could the local-national gulf in this question be driven by the fact that urban local communities are more diverse and that their inhabitants may perceive less change, at least locally, as a result of an influx of additional refugees than would inhabitants of less diverse (often rural) communities? The argument we have proposed implies that the local-national gap should be present across all types of communities even if the size of the gap may vary for reasons such as those mentioned. Therefore, if we were to find that the local-national gap is present, for example in urban communities but not in rural ones, this would count as evidence against the account we have advanced. By contrast, if we find that the gap is present for respondents living in different kinds of communities, this would strengthen the proposed account. Since the first experiment was administered to two different sub-panels, we have a large enough sample in this case (N = 2,849) to conduct detailed analysis of heterogenous effects across community type.

Figure 2 shows the results of a probit model, where the likelihood of perceived change is the dependent variable and experimental treatment and community type are the explanatory variables (interacted).8 The main take-away from the figure is that the local-national gap in perceived change remains sizable in all types of communities—whether they fit the description of urban, suburban, town, or rural/village. Interestingly, when the question is asked with reference to the national setting, levels of perceived change do not vary significantly across type of community. There is some indication that inhabitants in the more sparsely populated communities were somewhat more likely to perceive changes, but the differences are not statistically significant at conventional levels. Respondents in all types of communities are highly likely to have perceived changes when focusing on the national setting.

FIGURE 2. The local-national gap in perception of change by type of community. Proportion of sample who perceived something had changed.

When the question is asked about the local setting the main pattern is again one of similarity across types of communities. In all community types, only a minority of respondents are likely to have perceived change when focusing on the local setting. That noted, there is a difference in the levels of perceived change between sparsely and densely populated communities that reaches conventional levels of statistical significance. Respondents living in more rural communities (towns and villages) were somewhat more likely to perceive changes in their local communities as a result of the refugee crisis than were respondents living in more urban communities (cities and suburbs). Most importantly, however, any differences between communities are dwarfed when compared to the local-nation gap, which is sizable regardless of community type.

The difference seen between sparsely and densely populated communities in responses to the question “in the near” suggests that differences in local manifestations of the refugee crisis had some impact on perceived change. We know that during the refugee crisis in 2015/16, as many as 259 new asylum reception centers were established to house asylum applicants. There is substantial variation in how northern European countries host and distribute asylum seekers after arrival. In Norway, the reception and distribution of asylum seekers is handled centrally by the Directorate of Immigration (UDI). The specific process by which asylum center locations are chosen is subject to Norway’s strict rules for public procurement. When increased ASC capacity is needed, the UDI issues calls for new centers and different NGOs and private actors make bids to run a center. As a rule, the bidder who can run a center within the minimum standards required for the lowest cost is awarded the contract, but the UDI is required to cooperate closely with local communities and decision-making bodies.

The unprecedented increase in arrivals during 2015 lead to a swifter and more chaotic process for establishment of new centers than usual, and decisions were under substantially less local influence than what would normally be the case. Most of the ASCs during the crisis were established in existing buildings, (e.g. hotels, lodging for workers etc.), for which the owners had all the necessary permits to provide housing. Because this was done rapidly in response to an unexpected and large influx of refugees, many centers were located in more sparsely populated areas where localities that could be used were available at lower prices than in the urban and suburban areas.

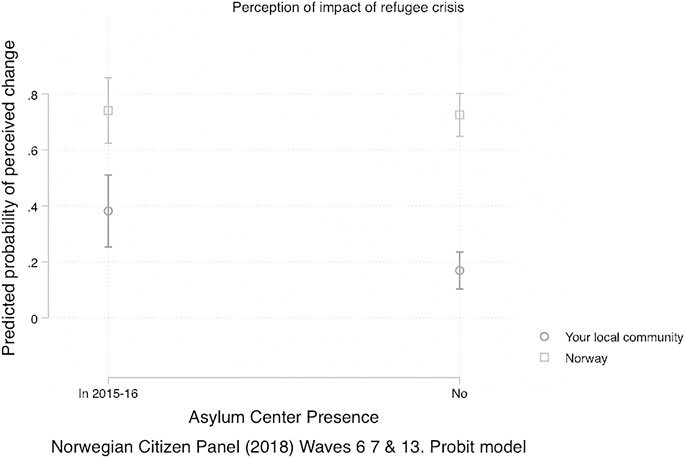

We naturally expect that respondents who live in local communities that received new asylum centers during the refugee crisis are more likely to report that they perceived change to their local community. Since Experiment 1 was embedded in a panel, several of our respondents had in previous waves been asked whether they live in a local community which received an ASC. We are therefore able to check if the local-national gap we observed is caused by this key difference in how the refugee crisis manifested in local communities.

Figure 3 displays the results of an analysis done according to the same procedure as laid out above in the description of Figure 2, only this time we condition the analysis on whether respondents lived in a local community that received a new ASC during the refugee crisis or not. It shows as expected that perception of change differs starkly in local communities with and without new ASCs. The likelihood that respondents who experienced the establishment of an ASC perceived that their local community had changed as a result of the refugee crisis is about 40%. By comparison, respondents living in local communities that did not experience such establishments were considerably less likely to perceive that their local community had changed. The comparable figure is about 20%. That noted, in neither type of community does a clear majority of respondents perceive that their local community had changed, even if they were aware that an ASC had been established there.

FIGURE 3. The local-national gap in perception of change by whether community received a new Asylum Seeker Center during the refugee crisis in 2015/6. Proportion of sample who perceived something had changed.

Turning now to consider the main question of the local-national gap, Figure 3 reveals a remarkable pattern. Even in those local communities that received an asylum center during the refugee crisis, a much larger share of respondents perceived that the country had changed than had their local community. About 80% of respondents in both communities perceive change when they were asked to consider the national setting. Remarkably, even in those very local communities that hosted the new asylum centers established in response to the refugee crisis, the local-national gap remains both substantially and statistically significant. A much larger share experienced change “in the far” as opposed to “in the near.”

In the second experiment, we asked respondents to evaluate the amount and nature of discussion about refugees and immigration. As before, we randomly varied whether respondents were asked about their local community or about Norway. We expected to find a local-national gap also in perception of public discussions, where respondents would perceive more and more conflict-oriented and divisive debates when focusing on the question “in the far” compared to when they focus on the question “in the near.”

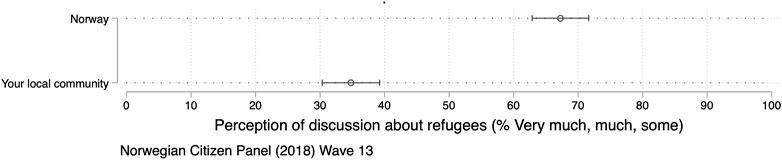

Figure 4 displays the main results for the experiment on amount of discussion. It brings out another sizable local-national gap. The share of respondents who report public discussion about immigration when the focus is on the national setting is around 70%. The share of respondents who report discussion about such questions when their focus is on the local community is only 35%. In other words, about twice as many respondents report some, much, or very much discussion about refugees in the national setting compared to the local one.

FIGURE 4. The local-national gap in perception of the amount of discussion about refugees and immigrants. Percent of sample who perceive very much, much, or some discussion.

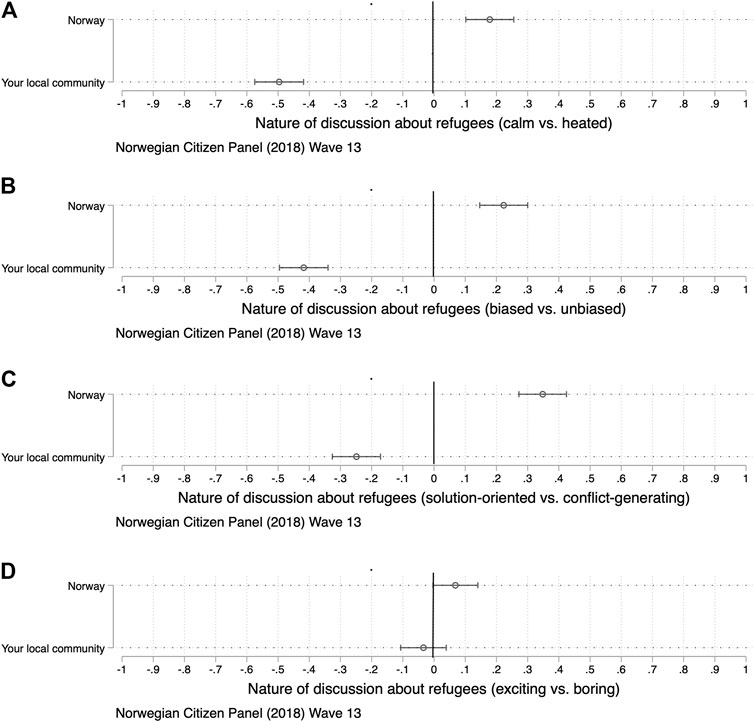

Turning to the analysis of the questions about the nature of discussion in Figure 5 panels A–D, we see that the local-national gap also extends to the nature of discussion about issues relating to refugees and immigration. When focusing on the question in the near, respondents are more likely to perceive the discussion as calm (Panel A), unbiased (Panel B), and solution-oriented (Panel C). When focusing on the question in the far, they are by contrast more likely to perceive discussions about issues relating to refugees and immigration as heated (Panel A), biased (Panel B), and a source of conflict (Panel C). Only on one of the dimensions do we not observe a local-national gap. As seen in Panel D of Figure 5, there is no gap in evaluations on the question of whether such discussion is interesting or boring. Respondents are equally likely to perceive the discussion as interesting regardless of setting.

FIGURE 5. The local-national gap in perception of the nature of discussion. Panel A. Calm vs. Heated. Direction and proportion of deviation from midpoint. Panel B. Unbiased vs. Biased, Direction and proportion of deviation from midpoint. Panel C. Solution-oriented vs. Conflict-generating. Direction and proportion of deviation from midpoint. Panel D. Boring vs. Exciting. Direction and proportion of deviation from midpoint.

In the final study, we dig deeper into the question of information sources about refugees and immigration. We already established notable local-national gaps in public perception of change following from the refugee crisis and public debate about issues related to immigration. One plausible conjecture is that this gap results from a difference in where members of the public seek and receive information about refugees and immigration. Systematic differences between the local and national setting in information sources of the kind proposed in Blumer´s classic account and discussed earlier would support this idea.

As described above, we examined this proposition in an open-ended question where we asked respondents to record the sources they rely on for information about refugees and immigration. Following up the approach used throughout this study, we randomly varied whether respondents were asked about the local or the national setting. Nearly all respondents recorded at least one source, and many recorded several. The responses were manually coded by two researchers using a template adapted from a previous study as described above (Wong et al., 2012). Most responses fit easily into this template. A complete overview of all cited sources is presented in the supplementary material (Supplementary Table S6).

Table 3 below lays out the main results. The media (without additional specifications) was mentioned as a source by the vast majority in both experimental groups. That noted, there is a considerable local-national gap in the share of respondents who mention the media broadly as a source of information about refugees and immigration. When asked about the national setting, nearly all respondents, 9 out of 10, mention the media as one of their sources. By contrast, when asked about the local setting, a substantially smaller share of respondents, about two-thirds, mention the media broadly as a source of information. The difference is approximately 25 percentage points.

Respondents asked to focus on their local community were more likely than those asked about the national setting to cite specific local media outlets, personal networks, and personal experiences and observations as sources of information with respect to refugees and immigration. In other words, we find that there are two kinds of local-national gaps in sources of information. First, there is a gap with respect to the likelihood of relying on social networks and personal experiences and observations. Those asked about the local community, are more likely to mention these types of sources than are those asked about the national setting. Second, we identify a gap in the type of media respondents mention. For the local setting, respondents are considerably more likely to report specific local media outlets as a source, while for the national setting local media is not frequently mentioned. Interestingly, there is not a local-national gap in the likelihood that social media is mentioned as a source of information. About a third of respondents mention social media in both conditions.

In this article we have dealt with an important but underexplored puzzle. Why, when nativism is so important for the far-right vote, do far-right parties underperform where natives and newcomers live their everyday lives together? Immigrants live in local communities. Voters and residents encounter immigrants where they live, and this is where local authorities and local organizations accommodate and integrate newcomers (Augustin and Jørgensen, 2019; Søholt and Aasland, 2019; Campomori and Ambrosini, 2020; Scalise and Burroni, 2020). We provided new empirical insights into an aspect of intergroup attitudes that can contribute to solving this puzzle. In three survey experiments, we revealed that natives relate systematically differently to questions concerning immigration and immigrants in local and national settings. We suggest that this local-national gap in intergroup attitudes is likely a part of the explanation for the underperformance of the far right in local elections.

All studies have limitations. So does this one. While we know from previous work that voting for the far right is strongly associated with intergroup attitudes and while this study demonstrates a local-national gap in intergroup attitudes, we have not proven the link between these two phenomena at the individual level. Doing so can be done, but will require a significant investment in new longitudinal data-collection to track individuals and their vote in (most often non-synchronous) local and national elections. The new hypothesis emerging from the findings of this study that could be tested on the individual-level is that those voters who cause the local-national gap in intergroup attitudes are the ones that are mainly responsible for the observed under-performance of the far right in local elections. To our knowledge this hypothesis has neither been posed nor tested before.

While we argue that it is likely that the local-national gap we have demonstrated in intergroup attitudes play a part in accounting for the observed local-national gap in far-right electoral outcomes, we do not want to suggest that it is likely to be the only explanation. In some countries, where the far-right is less institutionalized, such as in Germany or Sweden, the gap in electoral performance can be explained by supply side factors. The Norwegian case studied here, however, strongly suggests that the supply side is not the full explanation. The Norwegian far-right is on all counts a fully institutionalized party, so the persistent gap in electoral performance in local and national elections needs additional explanations. We have advanced one plausible alternative demand-side explanation here.

The main reason why we have proposed that it is likely that the local-national gap we have identified in intergroup attitudes will be relevant to the electoral outcomes of the far right is the strong link shown in previous research between intergroup attitudes and the far-right vote. That said, it should be noted that the items we have examined here are not the conventional indicators of nativism. Future studies should examine if the local-national gap persists also across a wider variety of indicators of nativism. Based on previous research, which finds strong correlations across survey items probing attitudes about immigrants and refugees, (e.g. Ivarsflaten, 2008, Sniderman et al., 2001), one plausible conjecture is that local-national gaps are common across items regardless of how they are phrased. That said, it is an interesting and highly relevant question for future research whether certain aspects of immigration is so firmly entrenched as either a national or a local issue as to counteract the disconnections between local and national setting that we have documented here.

In future research, the finding reported here about different sources of information for the local and national setting will likely be central. Norway (like Finland and Sweden) has a strong local press, both in terms of number of newspapers distributed and their importance as disseminators of public information and discussions (Allern and Pollack, 2019). Allern and Pollack (2019) foreground that in this context local media plays an unparalleled role in monitoring political decisions and public administration at the local level. We found that respondents asked to focus on their local community were more likely than those asked about the national setting to cite personal networks, personal experiences and observations, and local media as sources of information about refugees and immigration. This result is in line with previous related research. For example, a United States study found similar patterns regarding sources people draw on to form perceptions of the racial composition of their local community and the nation (Wong et al., 2012). The reliance on local media as a source of information about the local community is not surprising, but it is important especially in so far as local and national media consistently differ in their coverage of immigration-related news and themes.

Schmauch and Nygren’s (2020) analysis of local media coverage of refugees and integration in Sweden showed that a “threat frame” previously documented in analyses of national media was largely absent in their material. Similarly, Hognestad and Landmark (2017), who studied Norwegian local media stories during the refugee crisis, point to fewer “problem oriented” stories in their analyses, compared to previous analyses of Norwegian national media. When our respondents indicate that national debates are more heated, conflictual, and biased than local debates, this may in part reflect actual differences in media coverage of refugees and immigration at the local and national levels. Our account suggests that further research into such differences in media coverage is warranted as they may be important both in accounts of systematic variation in intergroup attitudes and voting patterns in local and national settings.

Our tests of possible heterogeneous effects across different types of local communities–urban, suburban, and rural–indicate that the local-national gap in intergroup attitudes is not driven by a dynamic associated with a particular type of local community. Perhaps most striking is the fact that we observed the local-national gap also among respondents who had an ASC established in their local community. Also they, who objectively speaking were most directly affected by the influx of refugees, were more likely to think that changes had occurred if they were asked about the national than about the local setting. This pattern can only be understood if we allow for intergroup attitudes in the national setting to be informed by something other than local experiences. More specifically, the findings are highly consistent with Blumer´s account of the construction of immigrants as a symbolic threat “in the far.” A possible implication of this line of argument is that not only differences in information sources and media representations, but also differences in political debates about immigration and immigrants in national and local politics matters. Future research should examine if the local-national gap documented here on the level of citizens also extend to political leaders and elected representatives.

As Blumer suggested, this should not be taken to mean that local conditions are unimportant. This study was conducted in Norway, a wealthy and well-organized democratic system where asylum reception condition even during the refugee crisis were better than in many other places, especially perhaps in transit hot-spots further South in Europe. Crowded and inhumane reception conditions and protracted waiting could lead to more conflict and resentment also at the local level than was observed in the context studied here, and this could make intergroup attitudes in the local setting more similar to those we have observed here for the national setting, and in this way narrow the local-national gap. Further studies in other contexts using the methodological approach established in this study could examine these questions empirically. Above all, this study underscores the importance in future studies of intergroup attitudes and far right voting of carefully distinguishing between local and national settings.

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: The data are provided by UiB, prepared and made available by Ideas2Evidence, and distributed by the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (NSD). Neither UiB nor NSD are responsible for the analyses/interpretation of the data presented here. Data from the Norwegian Citizen Panel are available upon request from the Norwegian Centre for Research Data: https://nsd.no/nsddata/serier/norsk_medborgerpanel.html. Data from the Norwegian Citizen Panel are available for non commercial use. Please see conditions of use here: https://www.uib.no/en/digsscore/122158/data-and-conditions-use. An anonymized version of the text data in Experiment 3 are available from the Authors upon request.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Norwegian Data Protection Authority (License number 34817). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

HB, SB, and EI contributed to the conception and design of the study. EI and HB performed the statistical analysis. HB, SB, and EI wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version. The author order is alphabetical and the auhtors contributed equally to this work.

The Norwegian Citizen Panel is Funded by the Trond Mohn Foundation and the University of Bergen (the DIGSSCORE grant). This study has also received funding from the Norwegian Research Council (IMEX, project number 262987). Open access publication of the paper is funded by the University of Bergen.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All sources of funding have been necessary to prepare and publish the present study and they are gratefully acknowledged. The authors would also like to thank Hanna Fylkesnes and Emilie Berâs Pedersen for their assistance in coding the qualitative material.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2021.660088/full#supplementary-material

1The far-right parties in these four countries at this point in time were: The Progress Party (Fremskrittspartiet) in Norway; the Danish People’s Party (Dansk Folkeparti) in Denmark; the Sweden Democrats (Sverigedemokraterna) in Sweden; the (True) Finns’ Party (Perussoumalaiset) in Finland.

2Additionally, of course, it is important to highlight that national and local governments have different jurisdictions. The issue of border control is mainly a national issue and in so far as immigration and immigrants are debated and perceived mainly as an issue of border control, voters may perceive immigration to be less salient in local politics than at the national level. Difference in the salience of the immigration issue in national and local politics is also likely a part of the explanation for the observed local-national gap in far-right electoral performance. What we additionally show is that even when salience is held constant in a series of survey experiments, voters still relate differently to immigration-related phenomena in local and national settings.

3This type of survey experiments, where respondents are randomly assigned to answering survey items that are the same except for one or a few words are not intended to demonstrate that a treatment can change respondents minds. Rather, they are designed to reveal aspects of public opinion that are otherwise hidden or hard to observe (see e.g., Sniderman, 2018 for an overview of the uses of this approach to survey experiments). Because of the carefully controlled question format and the random assignment to either local or national conditions, the survey experiments presented here show more conclusively than other types of survey designs that altering the context from local to national—and nothing else—results in the substantial differences in intergroup attitudes documented.

4We employed two different conceptualizations of the local level: the administrative term “municipality” and the respondent-defined “local community.” Norwegian municipalities vary greatly in geographical size and population, and are not equivalent to a single local community. As stated by Wong, Bowers, Williams, and Simmons (2012, p. 1153) “peoples’ perceptions of their environment do not resemble governmental units.” In this paper, our focus is on respondents’ perceptions of their local community.

5Experiments 2 and 3 were nested, meaning that respondents were randomized into either the national or the local condition for all questions. This was done to strengthen the experimental stimulus and prevent respondent confusion by providing a consistent focus on either the local or the national setting in a set of related questions. Experiments 2 and 3 were fully independent from experiment 1, which was fielded on a separate wave of the survey.

6Three open boxes were provided to encourage respondents to report more than one source. Most respondents did so.

7The figures contain the confidence intervals around these point-estimates. They are not repeated in the text to ease reading.

8Full regression results for all figures are reported in the Supplementary Material.

9The full tables of results corresponding to all figures are reported in Supplementary Material.

Allern, S., and Pollack, E. (2019). Journalism as a Public Good: A Scandinavian Perspective. Journalism 20 (11), 1423–1439. doi:10.1177/1464884917730945

Augustin, O. G., and Jørgensen, M. B. (2019). Solidarity Cities and Cosmopolitanism from below: Barcelona as a Refugee City. Social Inclusion 7 (2), 198–207. doi:10.17645/si.v7i2.2063

Barber, B. (2013). If Mayors Ruled the worldDysfunctional Nations, Rising Cities. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Bentsson, A., Hansen, K., and Hardarson, O. (2013). The Nordic Voter: Myths of Exceptionalism. London: Rowman & Littlefield.

Blommaert, J., Dewilde, A., Stuyck, K., Peleman, K., and Meert, H. (2003). Space, Experience and Authority. Jlp 2 (2), 311–331. doi:10.1075/jlp.2.2.08blo

Blumer, H. (1958). Race Prejudice as a Sense of Group Position. Pac. Sociological Rev. 1 (1), 3–7. doi:10.2307/1388607

Bygnes, S. (2020). A Collective Sigh of Relief: Local Reactions to the Establishment of New Asylum Centers in Norway. Acta Sociologica 63 (3), 322–334. doi:10.1177/0001699319833143

Campomori, F., and Ambrosini, M. (2020). “Multilevel Governance in Trouble: the Implementation of Asylum Seekers’ Reception in Italy as a Battleground”. Comp. Migration Stud. 8 (22), 1–19. doi:10.1186/s40878-020-00178-1

Carter, E. (2005). The Extreme Right in Western Europe: Success or Failure?. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

de Lange, S. L. (2007). A New Winning Formula? Party Polit. 13 (4), 411–435. doi:10.1177/1354068807075943

Eurostat (2016). Asylum in the EU Member States. Record Number of over 1.2 Million First Time Asylum Seekers Registered in 2015. Syrians, Afghans and Iraqis: Top Citizenships. ” (Press release).

Hess, Y. D., Carnevale, J. J., and Rosario, M. (2018). A Construal Level Approach to Understanding Interpersonal Processes. Social Personal. Psychol. Compass 12 (e12409), 1–13. doi:10.1111/spc3.12409

Hobolt, S. B. (2016). The Brexit Vote: a Divided Nation, a Divided Continent. J. Eur. Public Pol. 23 (9), 1259–1277. doi:10.1080/13501763.2016.1225785

Ivarsflaten, E., Blinder, S., and Bjånesøy, L. (2019). “How and Why the Populist Radical Right Persuades Citizens,” in The Oxford Handbook of Electoral Persuasion. Editors B. G. Elizabeth Suhay, and A. Trechsel (Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press).

Ivarsflaten, E., and Sniderman, P. M. (2021). The Struggle for Inclusion: Muslim Minorities and the Democratic Ethos. Forthcoming: Chicago University Press.

Ivarsflaten, E., and team, N. (2018). Norwegian Citizen Panel Waves 12 and 13. first NSD edition. University of Bergen and UNI Research Rokkan Centre. Bergen, Norway: The Norwegian Center for Research Data.

Ivarsflaten, E. (2008). What Unites Right-Wing Populists in Western Europe?. Comp. Polit. Stud. 41 (1), 3–23. doi:10.1177/0010414006294168

Jorgensen, M. B. (2012). The Diverging Logics of Integration Policy Making at National and City Level. Int. Migration Rev. 46 (1), 244–278. doi:10.1111/j.1747-7379.2012.00886.x

Kitschelt, H., and McGann, A. (1995). The Radical Right in Western Europe: A Comparative Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kriesi, H., Grande, E., Lachat, R., Dolezal, M., Bornschier, S., and Frey, T. (2008). West European Politics in the Age of Globalization. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511790720

Lipset, S. M., and Rokkan, S. (1967). “Cleavage Structures, Party Systems and Voter Alignments: An Introduction,” in Party Systems and Voter Alignments: Cross-National Perspectives. Editors S. M. Lipset, and S. Rokkan (New York: Free Press).

Mudde, C. (2007). Populist Radical Right Parties in Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511492037

Norris, P., and Inglehart, R. (2018). Cultural Backlash: Trump, Brexit, and Authoritarian Populism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Reif, K., and Schmitt, H. (1980). Nine Second-Order National Elections - a Conceptual Framework for the Analysis of European Election Results. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 8 (1), 3–44. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6765.1980.tb00737.x

Rydgren, J. (2005). Is Extreme Right-Wing Populism Contagious? Explaining the Emergence of a New Party Family. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 44 (3), 413–437. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6765.2005.00233.x

Scalise, G., and Burroni, L. (2020). Industrial Relations and Migrant Integration in European Cities: A Comparative Perspective. J. Eur. Soc. Pol. 30 (5), 587–600. doi:10.1177/0958928720951111

Schmauch, U., and Nygren, K. G. (2020). Committed to Integration: Local Media Representations of Refugee Integration Work in Northern Sweden. Nordic J. Migration Res. 10 (3), 15–26. doi:10.33134/njmr.326

Sniderman, P. M. (2018). Some Advances in the Design of Survey Experiments. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 21, 259–275. doi:10.1146/annurev-polisci-042716-115726

Sobolewska, M., and Ford, R. (2020). Brexitland: Identity, Diversity and the Reshaping of British Politics. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781108562485

Søholt, S., and Aasland, A. (2019). Enhanced Local-Level Willingness and Ability to Settle Refugees: Decentralization and Local Responses to the Refugee Crisis. J. Urban Aff. doi:10.1080/07352166.2019.1569465

Wong, C., Bowers, J., Williams, T., and Simmons, K. D. (2012). Bringing the Person Back in: Boundaries, Perceptions, and the Measurement of Racial Context. J. Polit. 74 (4), 1153–1170. doi:10.1017/s0022381612000552

Keywords: intergroup attitudes, far-right, immigration and migration, the European refugee crisis, local politics

Citation: Bye HH, Bygnes S and Ivarsflaten E (2021) The Local-National Gap in Intergroup Attitudes and Far-Right Underperformance in Local Elections. Front. Polit. Sci. 3:660088. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2021.660088

Received: 28 January 2021; Accepted: 23 April 2021;

Published: 07 May 2021.

Edited by:

Allison Harell, Université du Québec à Montréal, CanadaReviewed by:

Ruth Dassonneville, Université de Montréal, CanadaCopyright © 2021 Bye, Bygnes and Ivarsflaten. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Elisabeth Ivarsflaten, ZWl2MDAxQHVpYi5ubw==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.