- Centre for International Politics, Organization and Disarmament School of International Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, India

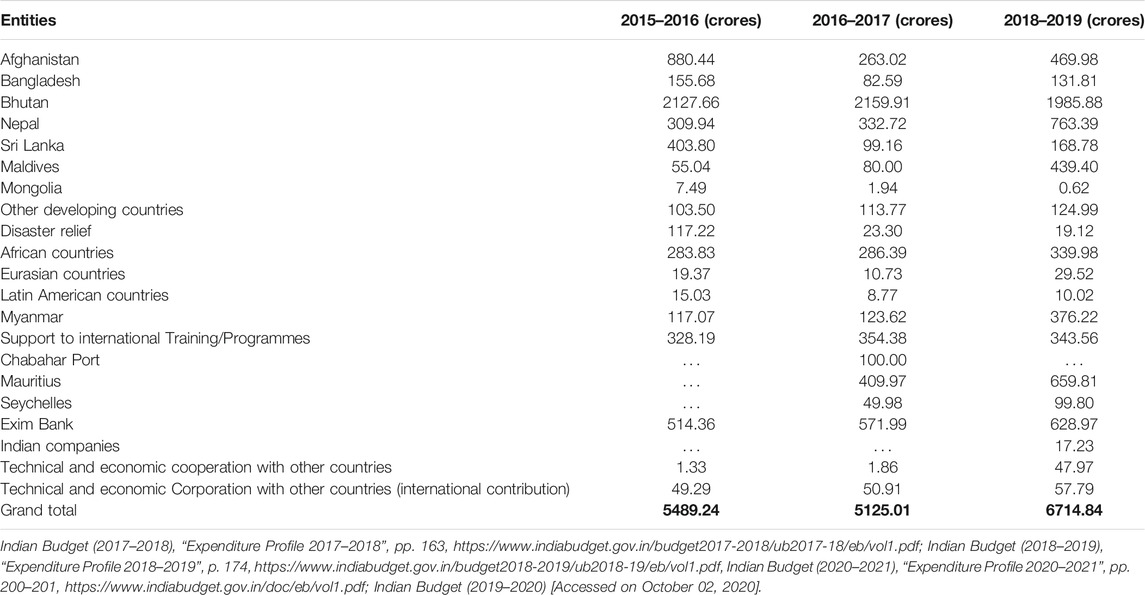

The emotional and ideological factor to express solidarity with the other developing countries is the main driving factor for India to engage in development assistance. In the changed geopolitical and geo-economic context in the globalized world, the economic factor of access to the market for Indian products and natural resources for its growing industrial sector became the additional motivation. As India does not subscribe to peacebuilding, it has no separate category of peacebuilding assistance. This study’s central focus is on why India’s way of providing development and peacebuilding assistance captured the world’s attention in the 21st century and how India’s ways are different from that of the OECD’s Development Assistance Committee (DAC) countries. It highlights India’s unique guiding principles, approaches, and modalities for development and peacebuilding assistance. It focuses on why the developing countries appreciated India’s development and peacebuilding assistance, although it is not much in terms of volume compared to the Development Assistance Committee countries. It emphasizes the advantages of accepting diversity instead of an attempt for uniformity in peacebuilding assistance.

Introduction

India’s peculiarity as a development assistance provider is that India itself was the major recipient of development assistance from the developed countries and multilateral organizations. Despite its own challenges, India set aside some of its scarce resources to assist other developing countries who had undergone similar exploitation and subjugation under the colonial rule. Its development assistance was motivated by emotional and ideological reasons to express solidarity with other developing countries. It had earned a rich dividend as India could emerge as the leader of developing countries and could exercise moral power to influence international politics during the Cold War era. Its lived experiences as a developing country influence the guiding principles and modalities for its development assistance.

Even in the changed geopolitical and geo-economic context of the globalized world, India continued to provide development assistance to other developing countries. However, the economic motivation to expand the market for Indian products and natural resources for its growing industrial sector became an additional motivational factor for engaging in development and peacebuilding assistance to the developing countries in the globalized era.

In the post–Cold War era, when the developed countries adopted peacebuilding to address challenges of the post-conflict states of intrastate conflicts, India did not subscribe to it. It suspected the intention behind the project of peacebuilding. Therefore, India did not separate its peacebuilding assistance from that of the development assistance. India’s development and peacebuilding assistance increased in volume. The modalities and geographical spread of its assistance also diversified as it gained new international status as an emerging economy in the turn of the century. Due to uniqueness of India’s principles, approaches, and modalities of development and peacebuilding assistance, the international attention has been attracted toward it. They are strikingly different from that of the DAC countries. These differences are due to the difference in India’s historical experiences, socioeconomic condition, and lived experiences as a developing country.

This study’s central focus is on why and how India’s way of providing development and peacebuilding assistance is different from that of the DAC countries. The article starts with discussing the evolution of Indian development assistance to lay the background and then delve into change in India’s development and peacebuilding assistance in the 21st century. Next, the article highlights India’s unique guiding principles of development and peacebuilding assistance and how they differ from the DAC countries. The major section of the article discusses the various modalities and instruments to provide development and peacebuilding assistance. It specifically discusses the assistance to Afghanistan and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) as examples for India’s peacebuilding assistance to the post-conflict states. The article ends with focusing on some of the major critiques of India’s development and peacebuilding assistance.

Evolution of Development Assistance

It is a misnomer to label India as a new actor in the international development arena as it has been providing development assistance to the developing countries since its independence in 1947. Despite its own development challenges, India dedicated a portion of its scarce resource to help fellow developing countries. Its decision to share its experience and expertise in development was emotional and ideational act of expressing solidarity with other developing countries (Mullen, 2014:3; Singh, 2017:73). This motivation was rooted in its shared experiences with the colonial countries. India played a pioneering role in awakening among the Asian and African people the exploitative relationship between the colonial powers and the colonies and it also set an example of freedom movement to achieve independence. After gaining its independence from the British colonial rule, India played a leading role in pushing for decolonization process, especially in the United Nations, which led to gaining of the political independence of Asian and African countries in 1950s and 1960s (Kennedy, 2015:94). Soon, Asian and African countries realized that they had not achieved economic independence as the exploitative economic relations between the colonial countries and the former colonizers continued even after their political independence. Once again, India played a leadership role of the developing countries in their struggle not only to keep way from the Cold War power struggle by following nonaligned foreign policy but also to bring about rapid economic development in the developing countries (Murthy, 2020: 6–11). Under such contextual situation, despite its own social and economic challenges, India shared its scarce resources and expertise to assist the fellow developing countries. Thus, India’s involvement in providing development assistance was an act of expressing solidarity with the developing countries rather than sense of responsibility or generosity. This emotional and ideological involvement with the developing countries paid a rich dividend as it could emerge as the leader of the developing countries in the world politics and use the currency of moral power to assert its influence at the global level. This emotional and ideological factor also influenced in adoption of India’s unique approaches to development. Thus, development assistance was and has been an integral part of India’s foreign policy.

At the initial stage, India’s development assistance was given mainly to its neighboring countries, such as Nepal, Burma, and Afghanistan, in grants and multiyear loans and technical assistance. For example, India provided “loans of around 200 million rupees to Myanmar and 100 million rupees to Nepal” in the 1950s (Sinha, 2017: 131). Later, the geographical extent of its assistance expanded other countries in Asia, Africa, and Latin America. From its own lived experience, India realized that the lack of skilled manpower is a major impediment for economic development. Therefore, India accorded priority in building capacity of the fellow developing countries in the form of assistance in the training program and educational scholarship. For example, in 1949, India provided scholarships to students from Asian and African countries. Since then, scholarships and educational exchange remain a significant part of India’s development assistance. Between 1947 and 1964, apart from bilateral development assistance, India offered assistance through the multilateral framework of Colombo Plan for Economic Development and Cooperation in South and Southeast Asia (Colombo Plan) launched in 1950 and Special Commonwealth Assistance for Africa Program (SCAAP) begun in 1960. It also started contributing to the United Nations Development Program (Tuhin, 2016, p. 30).

Due to rapid expansion of its capacity-building assistance, India launched Indian Technical and Economic Cooperation (ITEC) in 1964 as the main institutional mechanism for imparting training, skill development, and experience sharing with other developing countries. This mechanism has been actively used to this day. Indian development assistance under ITEC also included small numbers and amounts of grants and loans for disaster relief, agricultural, and industrial development. However, these grants and loans were only a small percentage of Indian development assistance (Center for Policy Research, 2015:1). In terms of volume, compared to the developed countries, the Indian development assistance was not much, but they are highly valued because of the suitability and appropriateness to the developing countries’ socioeconomic conditions. Through these development assistances, India could strengthen its soft power and augment its influence in global politics.

In the post–Cold War, the intrastate conflict became more frequent, and the concept of peacebuilding entered the United Nations lexicon to assist the states in rebuilding after being shuttered by this kind of conflict. The liberal peace theory became the primary theoretical lens that motivated DAC countries to engage in peacebuilding assistance in the post-conflict to bring about durable peace. The major donors like the United States and European countries have devised explicit policies, principles, and strategies to engage with fragile post-conflict states. For instance, “USAID has an explicit fragile states strategy, and the OECD has its policies and principles on engaging fragile states” (Adhikari, 2018: 165). In contrast, India does not have a specific policy or strategy that guides its engagement in the post-conflict states nor did it join the developed countries to champion the liberal peacebuilding agenda. India suspects the peacebuilding agenda of the DAC countries (Choedon, 2015).

Unlike the DAC countries, India did not differentiate between the development assistance and peacebuilding assistance. While the DAC countries focused on addressing the “governance gap”, especially in the post-conflict states, India continued to provide assistance to fill up “capacity gaps” (Sharan et al., 2013:6; Arora, 2017:243). After its domestic economic reforms with a shift toward the neoliberal policy paradigm in the 1990s, its development and peacebuilding assistance has been influenced more by geo-economic consideration than just the political and ideological factor. Its development assistance started to gear toward more commercial oriented with “tied credit”.

India’s involvement in the post-conflict reconstruction in the 1990s is known through its peacekeepers in the UN missions. They were actively engaged in reconstruction activities in their areas of deployment. Invariably, the Indian contingents included military engineers, medical team, and logistic experts, and these components were utilized to carry out various reconstruction and peacebuilding activities for the local population. For example, the Indian peacekeepers in Rwanda, in the 1990s, built roads and schools, dug up tube-wells for freshwater, rebuilt places of worship, and provided much needed medical assistance to the local population. The Indian medical camp of the UN mission in Ethiopia and Eritrea, for example, offered medical treatment to around 30,000 local populations (Choedon, 2017:24). These activities were beyond the call of duty. The Indian peacekeepers engaged in them to win the hearts and minds of the local population, which were crucial for the success of UN missions and earn goodwill for India. Due to their active involvement in reconstruction activities, some scholars have described the Indian peacekeepers as “developmental peacekeepers”. It indicates that Indian peacekeepers in the UN missions are the early peacebuilders since the 1990s.

Development and Peacebuilding Assistance in the 21st Century

Although a large section of its population is still in poverty, India has become a significant development assistance provider since the turn of the century. It is now part of the non-DAC group of countries which together account for around 12 per cent of worldwide aid (Meier and Murthy, 2011: 4). Between 2000 and 2014, India’s development assistance increased from Rs. 134 million in 1990–1991 to Rs. 1.2 billion in 2012–2013 (International Commission for Red Cross (ICRC), 2014). As of 2018–19, it has increased to Rs. 6.7 billion in the form of grants, loans, and interest rate subsidies from Exim Bank’s Line of Credits (LOCs) (Union Budget of India, 2020-2021: 201). Keeping in view the purchasing power parity of a US dollar spent in India, India’s development assistance budget is estimated to be several times higher than its value in dollar terms at the current prices (Sinha, 2017: 133; Samuel and George, 2016:24). It is because the cost of services and training resourced from India is much lesser than that of Europe or the United States. India’s assistance for peacebuilding in the post-conflict states also expanded as it now “have the finances, capacities, and expertise to provide effective support” (Singh, 2017:83). Its development and peacebuilding assistance evolved to become more mutually beneficial both for India and its partner countries in the 21st century.

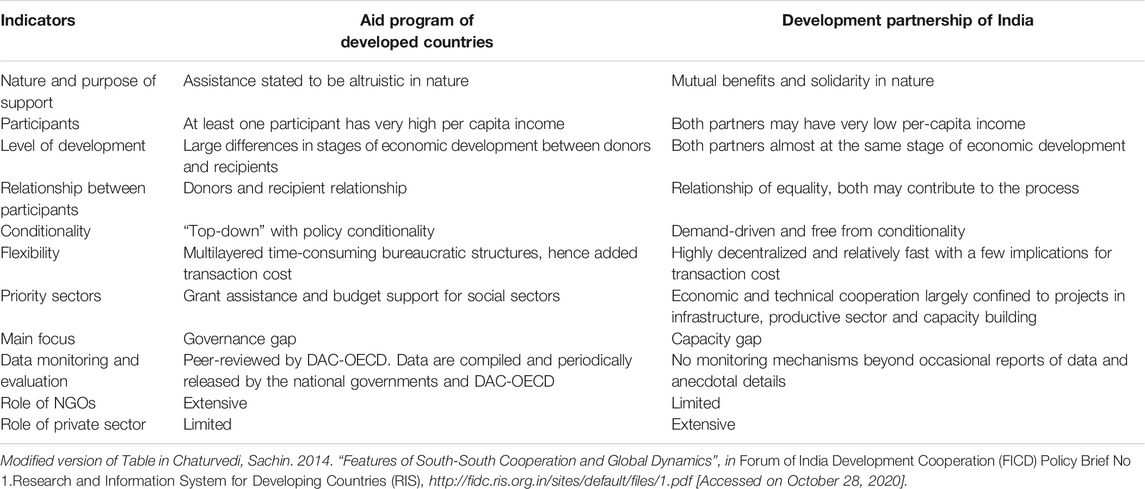

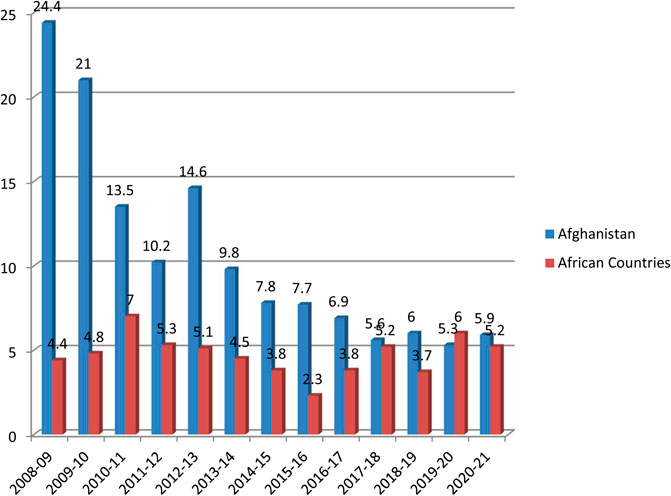

Table 1 shows the phenomenal increase in both the volume and diversification of modalities and the geographical spread of its development and peacebuilding assistance, keeping with India’s growing stature in international affairs. Table 1 also shows that there has been a reduction of grants to Afghanistan and increased to the African states, where there are a large number of post-conflict states. The exponential increase in the involvement of the emerging countries like India in the development and peacebuilding aid field raised tension and pose challenges to the developed countries’ exclusive hold in this field. The genesis of tension could be traced to the difference in motivation of engaging in development/peacebuilding assistance. DAC countries were motivated with the sense of responsibility toward the less developed states, whereas India was motivated by ethos of sharing its resources with the developing countries who suffered similar experience of exploitation and oppression under the colonial rule. The difference in motivation set the stage for adopting different approaches and principles in providing development assistance. These differences in approaches and principles cause tension. Therefore, India is not a part of the DAC, nor does it share its data with DAC or follow the DAC’s foreign aid policies (Mullen, 2014: 2).

TABLE 1. Grants and interest rate subsidies to development partners and international contribution from 2015 to 2019

Guiding Principles of Development and Peacebuilding Assistance

India’s emotional and ideological factor in dealing with the developing countries also influenced the shaping of its guiding principle of its development and peacebuilding assistance. India’s approach to development and peacebuilding assistance has been guided by a set of normative and operational principles, which are strikingly different from that of the DAC countries, as indicated in Table 2. In the globalized era, India preferred to use the term development partnership instead of development assistance or development cooperation. Instead of the donor–recipient relationship, India intentionally labeled its relationship as a development partnership to emphasis the egalitarian ethos of engagement. Although the guiding principles are not articulated in one document, these are reflected in its administration of development assistance to the developing countries.

One of the guiding principles of India’s development assistance is the principle of non-interference in domestic affairs and it respects the sovereignty of the development partners. This principle is aligned with the foreign policy paradigm of non-alignment and South-South solidarity, reflecting the post-colonial states’ sensitivity that cherished sovereignty as sacrosanct (Arora, 2017: 236). Their sensitivity to the issue of sovereignty is due to the hard and long struggle they had to fight against the colonial powers and had to make immense sacrifice to gain independence. Corollary to this principle is the principle of non-conditionality of the assistance which India adhered to in its dealing with development partners. The ethos behind this principle is not to constrain the sovereignty of the development partners. This principle is the direct outcome of India’s decision not to interfere with the development partners’ national policies, which sharply contrasts to the DAC countries’ imposition of macroeconomic and governance conditionality in their development assistance (Samuel and George, 2016:7). The developing countries also find India’s development and peacebuilding assistance congenial due to the principle of non-conditionality.

In line with the above two principles, India insisted on developing development partners’ independence in setting their national agenda and align its assistances to their national priorities. This practice signifies its adherence to the principle of national ownership of the development partners. Due to this principle, India has adopted the demand-driven approach to its development assistance in which the development assistance should be in “response to requests from the partner country and focus on addressing prevailing, pressing, and expressed needs” (Arora, 2017: 229). This approach signifies India’s sensitivity to the national interests, socioeconomic realities of its development partners. It is one of the core principles which distinguish the Indian way of development and peacebuilding assistance from that of the DAC countries.

Its persistence in using the term “development cooperation” and “development partnership” manifest that its relationship with the development partners is guided by the principle of “equality and mutual benefit”. It signifies each partner is on equal footing, without undue influence a partner exercise over another (Arora, 2017: 235). It indicates ethos of equality as both the parties in the development partnership have something to offer and take from each other. In reality, there is less mutual benefit as the recipients of development and peacebuilding assistance are the gainers to receive assistance at favorable terms. However, India states that its assistance is guided by the principle of “equality and mutual benefit” to placate the recipients’ concern of sovereignty. The Developing countries, including India, felt that sovereignty been violated by the western donors and the World Bank’s imposition of conditionalities for the assistance and loan.

These visions and values encapsulated in these principles have stood India in good stead as they demonstrate the uniqueness of India’s development and peacebuilding assistance and significantly enhanced its soft power and geopolitical influence.

Modalities and Instruments

India’s assistance in the 21st century is no longer in terms of modest loans and grant or just human resource training but now engage in skill-upgrading and the establishment of specialized institutions and infrastructures across the partner countries. Its loans in the form of lines of credit (LOCs) are for infrastructure development, investment, and trade, including post-conflict states. With the substantial increase in assistance, the aid modalities and instruments deployed have also diversified. The four main instruments that have emerged over the period are as follows:

1. Capacity-building and training (provided by ITEC within the Development Partnership Administration (DPA) in the Ministry of External Affairs (MEA))

2. Grant assistance (managed by the DPA within MEA. DPA also coordinates all other assistance related to loans)

3. Lines of credit or concessional loans (managed by Exim Bank of India with the Ministry of Finance as the coordinating institution)

4. Bilateral trade and investment

Capacity-Building: Training and Scholarship

By the turn of the century, India has made technical cooperation and capacity-building as a major policy focus for development and peacebuilding assistance. The Indian capacity development and training modality is both an end and means of development of its partners. It has been carried out through the ITEC program, which is fully government-funded, and is essentially bilateral. The government of India has made a considerable increase in the budget allocation for ITEC. It has increased from Rs. 1.33 crores in 2015–2016 to Rs. 47.97 crores in 2018–2019, as shown in Table 1. The capacity development and training programs have expanded substantially both in geographical spread and sectorial coverage. The Development Partnership Administration (DPA) was set up in the Ministry of External Affairs in January 2012 to manage and coordinate these programs. The ITEC now has the following five main channels of assistance:

1. Training in India of nominees of ITEC partner countries

2. Project-based cooperation, including related activities such as feasibility studies and consultancy services

3. Deputation of Indian experts abroad on the request of partner countries

4. Study tours to India for individuals and groups suggested by partner countries

5. Humanitarian aid for disaster relief

Apart from these five channels of ITEC, the educational scholarship is another channel for capacity building of the partner countries. India has capacity building partnership with 160 partner countries from Asia, Africa, East Europe, Latin America, the Caribbean, and Pacific and Small Island countries at present. It includes many of the post-conflict states. The civilian training program under IREC is conducting in 89 premier institutions of over 334 courses in a wide and diverse range of skills and disciplines, including alternative energy, project management, quality management, and women empowerment. It includes new courses in emerging areas such as artificial intelligence, nanotechnology, cybersecurity, and forensics. The courses are also adapted to partner countries’ demand and requirements (Ministry of External Affairs (MEA), Government of India, 2019-20: 247). The geographical coverage of the number of countries under the ITEC program and types of programs increased exponentially. For instance, the Program has expanded from about 4,000 training slots in 2006–07 to around 14,000 slots (including defense training) in 2019–20 (Ministry of External Affairs (MEA), Government of India, n.b.).

Apart from the civilian training, defense training is also conducted. The defense personnel from all three wings of services nominated by the partner countries are trained in the Indian prestigious institutions like National Defense College and Defense Services Staff College. The training field covers security and strategic studies, defense management, marine and aeronautical engineering, logistics and management, etc. (Ministry of External Affairs (MEA), Government of India, n.a.). For example, during 2019–20, 2,342 defense training slots were allocated to partner countries. The courses were both general and specialized nature (Ministry of External Affairs (MEA), Government of India, 2019-20: 249).

Among the post-conflict states, Afghanistan figures very high in India’s development assistance for reconstruction and peacebuilding due to its strategic significance. India invested significantly in Afghan people through education and capacity building assistance programs carried out by ITEC and Indian Council of Cultural Relations (ICCR) scholarship. Table 3 shows that annually between 300 and 600 s Afghans are trained in India.

The Ministry of External Affairs constituted Special Scholarship Scheme for Afghan nationals in August 2005 and appointed ICCR as the agency to implement. It started with 500 scholarships, and it has been increased to 1,000 from the academic year 2012–13 (Indian Council for Cultural Relations (ICCR), n). India is also supporting Afghanistan in the establishment of Afghanistan National Agriculture Sciences and Technology University in Kandahar. Even in defense matters, India provides considerable assistance. For example, the Indian technicians provided services to Afghan Air Force’s fleet of MiG 21 fighters and other defense equipment, mostly Russian and Soviet origin. India is also involved in the reorganization of the Afghan National Army (Pant, 2010: 140–41).

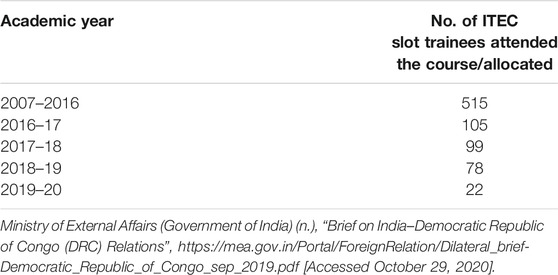

Among all the post-conflict states in Africa, India has been proactively engaged in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) for a long time both in terms of its involvement in the UN peacekeeping operations as well as bilateral peacebuilding assistance. The DRC has been a partner country of India in terms of capacity building and training under ITEC, as reflected in Table 4. Further, other kinds of training have been offered, for example, seven Congolese women (“Solar Mamas”) were trained between 2010 and 2015 in solar electrification and rooftop water harvesting course at Barefoot College, Rajasthan.

The DRC has availed the scholarship under ICCR, for example, in 2012–2013 thirteen scholarships and in 2013–14 fourteen. In subsequent years, the number of scholarships availed reduced. Again in 2018–19, there is a spike as it availed fifteen scholarships (Ministry of External Affairs (MEA), Government of India, n.c.). Two DRC scholars were also beneficiary of the prestigious CV Raman International Fellowship for African Researchers in 2014 and 2017.

Apart from making the people of the partner countries competent in administration, finance, and management skills, the Indian capacity building and training programs also empower the marginalized sections, particularly women at the grassroots level. For example, Indian NGO’s such as Self Employed Women’s Association (SEWA) has assisted, through the ITEC program, to develop skill and capacity of Afghan women to sustain themselves economically (Arora, 2017: 241). Similarly, Under the ITEC program, Solar Mamas from the rural poor non-electrified villages across Africa are being trained (The Indian Express, 2020).

Other Assistance Under Indian Technical and Economic Cooperation

The focus area of ITEC is also on technological transfer and the development of projects such as the Pan-African e-Network project. The ITEC also carries out other initiatives such as TERI-led initiative of a solar microgrid, solar home light systems, and solar multi utility units. These are some of the examples of transfer of technology as part of India’s development assistance to its partner countries. These technological transfers contributed to sustainable energy and rural electrification (Arora, 2017: 244). India has also supplied information technology–related equipment, hospital equipment, medicines, ambulances, vehicles, tractors, and agricultural equipment.

Another kind of assistance under ITEC is the scheme of deputing Indian experts to partner countries based on their requirements. It served a vital means to share Indian expertise with the developing countries. In 2019, 47 experts in various fields were on deputation to partner countries in health, agriculture, disaster response, archaeology, Ayurveda, legal experts, and English teachers. Even the defense training teams have been deputed to the partner countries based on their request (Ministry of External Affairs (MEA), Government of India, 2019-20: 249).

India also provides humanitarian aid for disaster relief to the affected countries. India’s conception of humanitarian assistance is narrower than Western donors. India uses the terms “humanitarian assistance” or “disaster relief” only to activities that address human suffering caused by natural disasters like cyclones, droughts, earthquakes, or floods. The DAC countries use the term humanitarian assistance to include assistance even to civilian populations affected by armed conflicts (Meier and Murthy, 2011: 6). The bulk of India’s humanitarian assistance for disaster relief is provided to its extended neighborhood. Its humanitarian assistance for disaster relief to countries in Africa and South America has increased over the year.

India’s humanitarian aid for disaster relief to Afghanistan is impressive. Since 2003, India has supplied high-protein biscuits to Afghan school children and directly donated one million tons of wheat in 2008. It has also stationed five medical missions in various parts of Afghanistan. In 2018, India supplied 1.7 lakh tons of wheat and 2,000 tons of pulses (Ministry of External Affairs (MEA), Government of India, 2019-20: 251). Just as the development assistance, India’s humanitarian aid for disaster relief to African countries has a long tradition.

Grants and Loans

India provides grant and loans to the partner countries and post-conflict states to develop critical infrastructure in various sectors such as railway links, roads and bridges, waterways, border-related infrastructure, transmission lines, power generation, hydropower, etc. India specifically grants projects to share with the development partners its strength in the field of information technology. For example, it provides grants to establish centers of excellence in information technology in various partner countries and impart training to the local population (Ministry of External Affairs (MEA), Government of India, 2019-20: 250). The DPA within MEA manages the grants. It also coordinates all other assistance related to loans.

One of the notable projects fully funded by the government of India was “Pan African e-network Project” for tele-education and telemedicine launched in 2009. It was intended to use the Indian expertise in information technology to benefit health care and higher education to all the African students. The Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, was responsible for the project, while the Telecommunications Consultants India Limited (TCIL) was the implementing agency. The African countries, including post-conflict states, could benefit as the project linked them to premier educational institutions and super speciality hospitals in India. At the time of handing over the project to the African Union Commission in 2017, 22,000 African students obtained degrees in various streams from various Indian universities through the network. 770 telemedicine consultations and tele-expertise sessions were carried out annually for the African countries, and 6,700 continuous medical education (CME) sessions were held for doctors and nurses in Africa (Mishra, 2018).

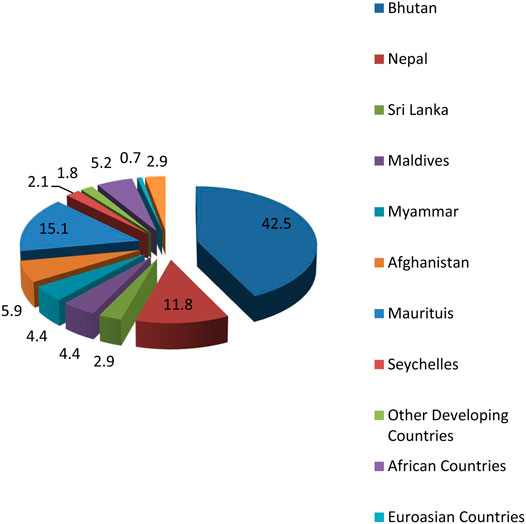

A similar kind of project, known as “e-VidyaBharti (Tele-education) and e-ArogyaBharti (Telemedicine)”, has been launched by the External Affairs Ministry of India on October 07, 2019. This project too aimed to “enable African students to access premier Indian education through the comforts of their homes and offer Indian medical expertise to African doctors and patients alike” (Ministry of External Affairs (MEA), Government of India, 2019). The project is expected to be fully funded by the government of India for its entire duration and open for participation to all partner countries in Africa. Figure 1 shows the latest geographical spread and volume of grants and loans to the countries and regions.

FIGURE 1. Grants and loans to countries and regions in 2020-2021 (percent of the total grants and loans). Source: Ministry of External Affairs (n), https://meadashboard.gov.in/indicators/92 [Accessed October 10, 2020].

Figure 1 shows that, apart from India’s neighboring countries, Afghanistan and African regions have been allotted large portion of India’s grant and loan assistance. India has been one of the leading donors to Afghanistan to carry out reconstruction and peacebuilding. It has taken on several medium and large infrastructure projects. These include the Salma Dam and power substation in Doshi and Charikar, and the Parliament building in Afghanistan. It has also taken on the small development projects scheme in agriculture, rural development, education, health, vocational training, etc. (Embassy of India, Kabul, n.).

In an attempt to adjust to the new situation in Afghanistan with the negotiation between the Kabul government and Taliban and an effort to reach out to the Taliban, India announced 150 projects worth US$ 80 million at the Afghanistan 2020 Conference held on November 23, 2020, through video-conferencing (Indian Express, 2020: 5). It signals India’s long-term commitment to Afghanistan’s future irrespective of whether it is reign by Taliban or other political forces.

Among the African countries, a large share of India’s grant has been provided to DRC for reconstruction and peacebuilding. The DRC has been the recipient of various grants, such as 60 Sonalika tractors with accessories and spare parts worth US$ 0.66 million, the supply of medicine worth US$ 1 million, signed MOU in October 2010 set up IT Centre of Excellence in Kinshasa. It has also been a beneficiary of tele-education and telemedicine under the Pan African e-network project (Embassy of India, Kinshasa, n.). Figure 2 shows grants to Afghanistan and African regions over the years.

FIGURE 2. Grant to Afghanistan and African region with many post-conflict states (2008-09 to 2020-21) (percent of the total grants and loans). Source: Ministry of External Affairs (n), https://meadashboard.gov.in/indicators/92 [Accessed October 12, 2020].

Lines of Credit

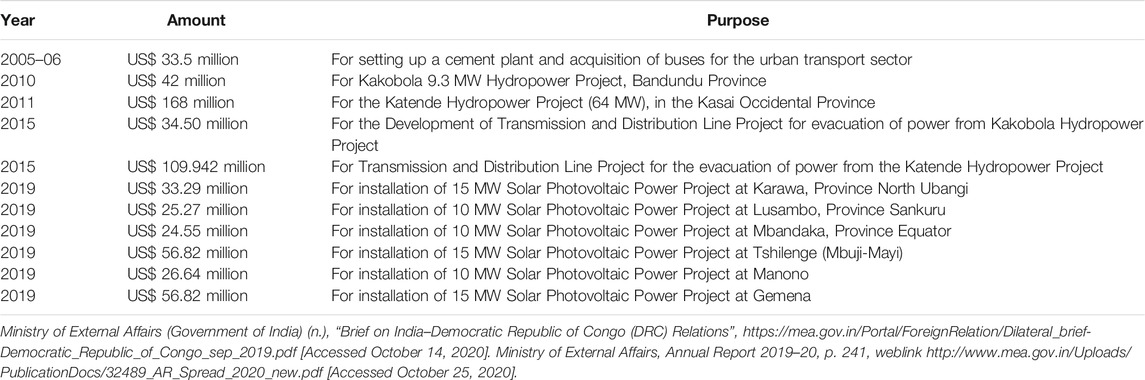

With the increase in request from the partner countries for assistance in the 21st century, India was not in a position to meet them through its usual modality of grants and loan directly charged to the national budget and disbursed through the State Bank of India. It could no longer justify the increase in assistance to other developing countries when a third of the Indian population lives below the poverty line. Therefore, a new modality of the line of credit scheme (LOCs) has been introduced since 2004. It is a long-term loan at a concessional rate provided to its partner countries, and the money is disbursed and repaid in a phased manner through the EXIM Bank. The Exim Bank of India manages this scheme with the Ministry of Finance as the coordinating institution. LOCs on concessional terms have become India’s main instruments of assistance for developing countries, including post-conflict states in the 21st cenury. The interest rate differentials from the international market rate of interest are borne by the government of India, which is reflected in Table 1.

The LOCs are increasingly extended to partner countries for large-scale projects (Chaturvedi, 2012: 568). Total line of credits provided by India in 2014–2020 is US$ 18.6477 billion (Ministry of External Affairs (MEA), Government of India, n. d). During the founding conference of the International Solar Alliance (ISA) on March 11, 2018, the Prime Minister of India, Modi, had announced India’s commitment to extend nearly US$ 1.4 billion worth of LOCs to cover 27 projects amounting to US$ 1.29 billion in 15 countries, especially in Africa (MEA, 2019–20: 244). The African countries have over the years remained the primary beneficiary of Indian LOCs. Indian LOCs are demand-driven as the projects are identified primarily by African governments.

However, these LOCs meant to enable the borrowing countries to import goods and services from India as 75 per cent of the goods and service bought through the LOCs has to be procured from India. Similar to the label of “tied aid” of the DAC countries, this kind of condition for the credit is labeled as “tied credit” (Sinha, 2017: 135). Due to the tied nature of credit, doubts have been raised whether this kind of credit could be regarded as development assistance. For some, it appears more as a way of promoting the exports of Indian goods and services. Keeping in view the tradition set by the Western donors to regard “tied aid” as an aid, there is no justification of why the “tied credit” should not be considered as development assistance.

The DRC has been granted LOCs of $227.55 million in 2014–2019 for reconstruction and peacebuilding projects. The number of LOCs for infrastructure projects in DRC has increased in the recent year, as reflected in Table 5.

Bilateral Trade and Investment

Another major instrument for development cooperation is bilateral trade and investment. In fact, in the globalized world, promoting its own trade and investment interests has been an important reason for India engaging in development and peacebuilding assistance. The DPA coordinate a range of activities related to trade and investment. As discussed earlier, the EXIM Bank provides credit to the partner countries to promote India’s goods and services. One of the reasons African countries become the primary beneficiary of Indian LOCs is that Africa is an important source for oil and minerals and other raw materials for the expanding Indian economy. At the same time, African countries have become an important market for India’s capital and consumer goods. Both India and Africa sees an enormous scope for mutually beneficial trade, commerce, and investment linkages (Desai, 2009: 415). Several prominent Indian private business houses have made large investments in Africa in sectors such as automobile, information technology, and pharmaceuticals.

Among the post-conflict states, trade and commercial linkages between India and DRC have been expanding. Indian companies are engaged in the mining of natural minerals like copper, cobalt, and diamond in DRC. The DRC imports large-scale pharmaceutical products from India, and some of them are reexported to neighboring countries like the Republic of Congo, Gabon, and the Central African Republic. Indian businessmen have also been investing in DRC in sectors like logistics, education, restaurants, supermarkets/departmental stores, etc. TATA Motors and Mahindra have distribution centers in the DRC. Bharti Airtel of India ranks as the third-largest telecommunication company in DRC (Ministry of External Affairs (MEA), Government of India, n. c). These accounts show that Indian private sector companies are actively involved in reconstruction and peacebuilding projects in DRC.

Similarly, bilateral trade and investment between India and Afghanistan is another modality adopted to assist Afghanistan in peacebuilding. The Preferential trade agreement signed by India and Afghanistan in 2003 gives substantial duty concessions to specific categories of Afghan dry fruits when entering India, with Afghanistan allowing reciprocal concessions to several Indian products. Kabul also encourages Indian businesses to help develop a manufacturing hub in cement, oil and gas, electricity, and services including hotels, banking, and communications (Pant, 2010: 138). The bilateral trade between India and Afghanistan has expanded, and it has crossed US$ 1.5 billion in the financial year 2019–2020. The trade between the two countries increased over the last five years. Of late, the Afghan government has been interested in obtaining its procurement requirements from India. Kabul’s Indian mission has facilitated several agreements between Indian companies and the Afghan National Procurement Authority (Embassy of India, Kabul, n.). The Indian private sector companies are also actively involved in Afghanistan in reconstruction and peacebuilding projects.

The above substantial increase in assistance and diversification of modalities and instruments became possible due to the change of India’s status from just one of the developing countries to an emerging economy by the turn of the century. Its favorable assistance modalities and expression of solidarity with the developing countries also continue to serve its foreign policy as Global South continue to be base for project of India’s power at the global level.

Critique

The Indian development assistance has been criticized on various accounts. One of the major criticisms is the lack of clearly formulated development policy which makes challenging to gauge the effectiveness of the development assistance (John and George, 2016: 25, 29). The reason for this lacuna seems to be that India’s development assistance is not a donor-driven approach. Instead, it is a demand-driven approach with a strong element of mutuality of benefits of both the partners. Further, the situation and requirement of the development partners vary. Therefore, it seems not feasible to have one straitjacket policy for all kinds of situations.

Another issue frequently raised by the stakeholders is the delays in loan approval by the Indian authorities and negligence on the part of the Indian contractor agencies to provide goods and service, which slow down some of the projects’ progress. This issue has been raised again at the 17th review meet on LOCs in August 2020 (Saif, 2020). The issue needs to be addressed to improve the effectiveness of the development assistance and peacebuilding activities.

Regarding India’s records in executing big projects, especially carried out by the Indian state-owned enterprises, it has pointed out unsatisfactory implementation due to the lack of supervision and monitoring system (Sinha, 2017: 148). This issue needs to be addressed by making the stakeholders more accountable and ensure more cost-effective delivery.

The lack of adequate transparency and accountability mechanism in India’s development and peacebuilding assistance is another major challenge. One of the possible reasons for this lacuna is the principles of mutuality and equality of the partners. These principles expect both the partners to be accountable to each other. Further, India does not have the tradition of evaluation or monitoring report of development assistance of India.

Another criticism is the absence of robust project guidelines for the Indian private sector actors’ involvement in the development activities, especially in the post-conflict states. They have been often accused of not following ethical, human rights, or environmental guidelines, leading to compromise of the development gains (John and George, 2016: 29). It may be possible to formulate guidelines for the Indian private sector actors involved in providing goods and service under the LOCs system. However, it will be challenging to establish guidelines for those Indian private sector actors who carry out transactions in the developing countries, including the post-conflict states, with their own capital and arrangements with the host states.

India has the experience of engagement with substantial development and peacebuilding assistance for just two decades. India could improve its transparency and accountability mechanisms over the period, keeping in view its own priority and values.

Conclusion

India’s engagement in providing development assistance to the developing countries goes back since its inception as an independent sovereign state in 1947. Despite its own enormous challenge of development after centuries of the colonial rule, India sat aside some of its scarce resources to assist the other developing countries. The Indian way of providing development and peacebuilding assistance is significantly different from that of the DAC countries in terms of motivation, guiding principles, and approach.

The DAC countries provided development assistance due to their sense of obligation toward the less developed countries. India was motivated to provide development and peacebuilding assistance to express solidarity to the fellow developing countries that had common experiences of exploitation and suppression under the colonial rule. India’s guiding principles and development assistance approaches are in tune with the recipients’ sensitivity to the issue of sovereignty. Compare to the DAC countries, the Indian development assistance is not much in terms of volume, but they were highly valued because of the suitability and appropriateness to the socioeconomic conditions of the developing countries. India’s expression of solidarity earned rich dividend as India could emerge as the leader of the developing countries and use the moral power to gain influence at international politics.

However, in the post–Cold War and globalized era, there is a shift in India's motivational factor to remain engaged in providing development and peacebuilding assistance. In the changed geopolitical and geo-economic situations, finding a market for Indian products and raw materials for its rapidly growing industries became the predominant motivating factor. Thus, along with political solidarity, India has been motivated to provide development and peacebuilding assistance to gain mutually beneficial economic engagement. In reality, there is less mutual benefit as the recipients of development and peacebuilding assistance are the gainers to receive assistance at favorable terms. However, India states that its assistance is guided by the principle of “equality and mutual benefit” to respect the recipients’ sensitivity to sovereignty.

The increased intrastate conflict and preoccupation of the international community to deal with post-conflict states led to the emergence of a new concept of peacebuilding based on liberal peace theory. Western countries are motivated to spread liberal, capitalist, economic, and liberal democratic systems in the post-conflict states with the belief that these would be the antidote to internal conflicts. So they adopted peacebuilding as a separate device from that of the development assistance to assist the post-conflict states in rebuilding. India does not subscribe to the liberal peace paradigm. India suspected the intention of the DAC countries’ enthusiastic involvement in peacebuilding in the post-conflict states.

India has not separated peacebuilding from its development assistance. So there is no separate provision for peacebuilding assistance in the Indian national budget. However, India is involved in post-conflict reconstruction and peacebuilding activities by providing development assistance to the post-conflict states. The volume and scale were not much throughout the 1990s. India's major role in the post-conflict states in the 1990s was through its peacekeepers in the UN peacekeeping operations and their active engagement with reconstruction activities in the areas of their deployment which earned them the label of “developmental peacekeepers.”

However, by the turn of the century, India, along with some of the developing countries, achieved rapid economic growth, and they have become the significant development assistance providers. There is a phenomenal increase in both the volume and diversification of India’s development assistance in keeping with India’s growing stature in international affairs. India’s engagement in peacebuilding activities also expanded and diversified as it now has the finances, capacities, and expertise to provide effective support to the post-conflict states. It is reflected in India’s involvement in peacebuilding activities in two most prominent post-conflict states in the 21st century, Afghanistan and DRC.

However, the DAC countries view the non-DAC countries’ engagement in the development and peacebuilding aid arena as a threat to their development assistance and peacebuilding frameworks and erosion of their sphere of activities. There is a vast difference in the principles, the focus, and the modalities of the assistance. These differences between the DAC countries and India have emerged due to difference in historical experiences, socioeconomic context, and lived experiences of India as a developing country. The principles of equality between the participants, the mutual gain of both the parties and the assistance based on demand-driven, free from conditionality, respecting the sovereignty, and local ownership of the recipients’ countries differ sharply from those of the DAC countries. Also based on the lived experiences, India focuses its development assistance on capacity building, which is different from that of the intrusive focus of the DAC countries on addressing the governance gap.

Even the varieties of modalities and instruments through which India provided development assistance to its partners are also unique, and they are suitable and appropriate to the socioeconomic realities of the developing countries. India’s development assistance to its partners through bilateral trade and investment is also in tune with the prevailing idea of trade as an important tool for development touted at the global level. So the “tied credit” that India practiced does not merit being viewed with disdained as this practice promotes both partners’ mutual interests.

In a nutshell, India’s way of development and peacebuilding assistance attracts international attention because of its unique principles, approaches, and modalities. At the moment, development and peacebuilding assistance have been done on parallel tracks by the DAC and non-DRC countries, including India, suspicious of each other. Instead of viewing India’s way of doing development and peacebuilding assistance as a challenge to the DCA’s established frameworks, it would be advantageous to accept the diversities as complementarity to address the global challenges. Instead of carrying on usual ways of superimposing the economic and governance models of mature and high-income donors of DAC countries, they could learn some lessons from India’s experiences of doing peacebuilding and providing development assistance. India has shown the alternative way of doing peacebuilding and providing development assistance. It is advantageous to the developing countries as they have now an alternative source of development and peacebuilding assistance. The diversity in the field of development and peacebuilding assistance in the post-conflict states should be celebrated rather than endeavor to bring about uniformity.

Keeping in view the recurring conflicts and humanitarian crises despite the peacebuilding efforts, the United Nations has shifted the focus on “sustaining peace” since 2016. There is possibility of doing further research on feasibility of adopting India’s approach to development/peacebuilding assistance as means to bring about sustainable peace in the conflict areas.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2021.637912/full#supplementary-material

References

Adhikari, M. (2018). India in South Asia: Interaction with Liberal Peacebuilding Projects. India Q. 74 (2), 160–178. doi:10.1177/0974928418766731

Arora, Kashyap. (2017). An Indian Approach to International Development Cooperation: Towards a ‘White Paper’ on Policy. Jindal J. Public Policy 3 (1), 227–270. Available at: https://jgu.s3.ap-south-1.amazonaws.com/jsgp/An_indian_approach_towards_white_paper.pdf (Accessed September 10, 2020).

Centre for Policy Research (2015). 50 Years of Indian Technical and Economic Cooperation: A Report,” Available at https://www.cprindia.org/sites/default/files/working_papers/IDCR%20Report%20-%2050%20years%20of%20ITEC.pdf (Accessed October 12, 2020).

Chaturvedi, S. (2012). India's Development Partnership: Key Policy Shifts and Institutional Evolution. Cambridge Rev. Int. Aff. 25 (4), 557–577. doi:10.1080/09557571.2012.744639

Choedon, Yeshi. (2017). India’s UN Peacekeeping Operations Involvement in Africa: Change in Nature of Participation and Driving Factors. Int. Stud. 51 (1-4), 16–34. doi:10.1177/0020881717719184

Choedon, Y. (2015). India and Democracy Promotion. India Q. 71 (2), 160–173. doi:10.1177/0974928414568618

Embassy of India, Kabul (n). “Development Partnership”. Available at: https://eoi.gov.in/kabul/?0707?000 (Accessed October 05, 2020).

Embassy of India, Kinshasa (n). “India – Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC): Relations. Available at: https://eoi.gov.in/kinshasa/?pdf0810?000 (Accessed October 16, 2020).

Indian Council for Cultural Relations (ICCR) (n). Indian Council for Cultural Relations Scholarship Schemes. Available at: http://a2ascholarships.iccr.gov.in/home/getAllSchemeList (Accessed October 10, 2020).

Indian Express, (2020). “India Pledges Aid to Rebuild Afghanistan, Commits to Projects Worth $80 Million,” November 24.

International Commission for Red Cross (ICRC) (2014). “From Aid to Partnerships: India’s Humanitarian Assistance. Available at: https://www.icrc.org/en/document/aid-partnerships-indias-humanitarian-assistance (Accessed September 15, 2020).

Kennedy, Andrew. B. (2015). “Nehru's Foreign Policy: Realism and Idealism Conjoined,” in Indian Foreign Policy. Editors David. M. Malone, C. Raja Mohan, and Srinath Raghavan (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 92–103.

Meier, Claudia., and Murthy, C. S. R. (2011). India’s Growing Involvement in Humanitarian Assistance. Research Paper No. 13 (Berlin: Global Public Policy Institute). Available at: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1789168 (Accessed September 10, 2020).

Ministry of External Affairs (Government of Indian) (MEA) (2019). Official Launch of E-VidyaBharti and E-ArogyaBharti Project by External Affairs Minister,”. Available at: https://www.mea.gov.in/press-releases.htm?dtl/31928/Official+Launch+of+eVidyaBharti+and+eArogyaBharti+Project+by+External+Affairs+Minister+October+09+2019 (Accessed October 10, 2020).

Ministry of External Affairs (MEA), Government of India (2019-20). Annual Report. Available at: http://www.mea.gov.in/Uploads/PublicationDocs/32489_AR_Spread_2020_new.pdf (Accessed October 25, 2020). doi:10.2139/ssrn.3395638

Ministry of External Affairs (MEA) Government of Indian (nc). Brief on India-Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) Relations. Available at: https://mea.gov.in/Portal/ForeignRelation/Dilateral_brief-Democratic_Republic_of_Congo_sep_2019.pdf (Accessed October 14, 2020). doi:10.2139/ssrn.3395638

Ministry of External Affairs (MEA) Government of Indian (nd). Performance Smart Board. Available at: https://meadashboard.gov.in/indicators/133 (Accessed November 10, 2020).

Ministry of External Affairs (MEA), Government of India (nb). Capacity Building and Technical Assistance as Development Partnership. Available at: https://mea.gov.in/Capacity-Building-and-Technical-Assistance-as-Development-Partnership.htm (Accessed October 20, 2020).

Ministry of External Affairs (MEA), Government of India (na). Indian Technical and Economic Cooperation Programme. https://www.itecgoi.in/about (Accessed October 25, 2020). doi:10.2139/ssrn.3395638

Mishra, Abhishek. (2018). Pan Africa E-Network: India’s Africa Outreach. (New Delhi: Observer Research Foundation). Available at: https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/pan-africa-e-network-indias-africa-outreach/ (Accessed October 09, 2020).

Mullen, Rani. D. (2014). “The State of Indian Development Cooperation,” in The State of Indian Development Cooperation (New Delhi: Indian Development Cooperation Research (IDCR) Report), 2–22. Available at: https://www.cprindia.org/research/reports/state-indian-development-cooperation-report (Accessed October 15, 2020).

Murthy, C. S. R. (2020). India in the United Nations: Interplay of Interests and Principles (New Delhi: Sage). doi:10.4135/9789353885786

Pant, H. V. (2010). India in Afghanistan: a Test Case for a Rising Power. Contemp. South Asia 18 (2), 133–153. doi:10.1080/09584931003674984

Saif, Saifuddin. (2020). 17th Review Meet on Indian LOC Projects Starts Wednesday. The Business Stand. 16 August. Available at: https://tbsnews.net/bangladesh/infrastructure/17th-review-meet-indian-loc-projects-starts-wednesday-120346 (Accessed November 16, 2020).

Samuel, John., and George, Abraham. (2016). Oxfam India-ISDG Research Study. Available at: https://www.oxfamindia.org/sites/default/files/WP-Future-of-Development-Cooperation-Policy-Priorities-for-an-Emerging-India-12072016.pdf (Accessed October 10, 2020). Future of Development Cooperation Policy Priorities for an Emerging India

Sharan, Vivan., Cambell, Ivan., and Rubin, Daniel. (2013). India's Development Cooperation: Charting New Approach in a Chaning World. Observer Res. Found. Spec. Rep. Issue2, July. doi:10.1109/ghtc-sas.2013.6629893. Available at: https://www.orfonline.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/SpecialReport2.pdf (Accessed September 10, 2020).

Singh, P. K. (2017). “Peacebuilding through Development Partnership: An Indian Perspective,” in Rising Powers and Peacebuilding Breaking the Mold?. Call and Cedric de Coning. Editor T. Charles (Palgrave Macmillan), 69–91. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-60621-7_4

Sinha, S. (2017). “Rising Powers and Peacebuilding: India's Role in Afghanistan,” in Rising Powers and Peacebuilding Breaking the Mold?. Call and Cedric de Coning. Editor T. Charles (Palgrave Macmillan), 129–165. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-60621-7_7

The Indian Express (2020). “PM Modi Interacts with ‘Solar Mamas’ of Africa in Tanzania,”. Available at: https://indianexpress.com/article/india/india-news-india/pm-modi-interacts-with-solar-mamas-of-africa-in-tanzania-2905151/ (Accessed October 27, 2020).

Tuhin, Kumar. (2016). “India’s Development Cooperation through Capacity Building,” in India’s Approach to Development Cooperation. Editors Chaturvedi. Sachin, and Mulakala. Anthea(London and New York: Routledge), 29–44.

Union Budget of India (2020-2021). Table of Contents. Available at: https://www.indiabudget.gov.in/doc/eb/vol1.pdf (Accessed October 15, 2020).

Keywords: solidarity, ownership, mutuality, egalitarian, conditionality

Citation: Choedon Y (2021) India’s Engagement in Development and Peacebuilding Assistance in the Post-Conflict States: An Assessment. Front. Polit. Sci. 3:637912. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2021.637912

Received: 04 December 2020; Accepted: 30 April 2021;

Published: 31 May 2021.

Edited by:

Marc Lanteigne, Arctic University of Norway, NorwayReviewed by:

Sasikumar S. Sundaram, American University, United StatesLina Alexandra, Centre for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), Indonesia

Copyright © 2021 Choedon. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yeshi Choedon, eWVzaGljaG9lZG9uQHlhaG9vLmNvbQ==

Yeshi Choedon

Yeshi Choedon