94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Polit. Sci., 15 March 2021

Sec. Elections and Representation

Volume 3 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2021.636745

This article is part of the Research TopicPolitical Psychology: The Role of Personality in PoliticsView all 9 articles

The personality traits of political candidates, and the way these are perceived by the public at large, matter for political representation and electoral behavior. Disentangling the effects of partisanship and perceived personality on candidate evaluations is however notoriously a tricky business, as voters tend to evaluate the personality of candidates based on their partisan preferences. In this article we tackle this issue via innovative experimental data. We present what is, to the best of our knowledge, the first study that manipulates the personality traits of a candidate and assesses its subsequent effects. The design, embedded in an online survey distributed to a convenience sample of US respondents (MTurk, N = 1,971), exposed respondents randomly to one of eight different “vignettes” presenting personality cues for a fictive candidate - one vignette for each of the five general traits (Big Five) and the three “nefarious” traits of the Dark Triad. Our results show that 1) the public at large dislikes “dark” politicians, and rate them significantly and substantially lower in likeability; 2) voters that themselves score higher on “dark” personality traits (narcissism, psychopathy, Machiavellianism) tend to like dark candidates, in such a way that the detrimental effect observed in general is completely reversed for them; 3) the effects of candidates’ personality traits are, in some cases, stronger for respondents displaying a weaker partisan attachment.

Elections are usually considered a mechanism through which voters decide in which direction a polity should be heading policy-wise: What measures should be taken to boost the economy? How should the problem of social inequality be addressed? How can the environment be protected, and climate change effectively tackled? What policies should be implemented to protect the country from foreign threats? But elections are also the time when voters choose political leaders. Often there are large - sometimes even dramatic - differences between candidates in terms of their (perceived) skills (e.g., competence, leadership) and image (e.g., charisma). More fundamentally, most candidates differ with respect to their personality - “who we are as individuals” (Mondak, 2010, p. 2). The recent U.S. presidential elections provide a clear example that voters were asked not only to make a choice between competing sets of policies, but also between different personalities (e.g., Visser et al., 2017; Nai and Maier, 2018; Book et al., 2020).

Choosing leaders with a particular personality profile can potentially lead to serious political consequences. For instance, the personality of political leaders has been shown to drive their accomplishments once in office in terms of, e.g., policy accomplishments, relationships with the legislative branch, use of executive orders, and likelihood of unethical behavior (e.g., Rubenzer et al., 2000; Lilienfeld et al., 2012; Watts et al., 2013; Joly et al., 2019).

Voters often display low motivation and information about politics (e.g., Delli Carpini and Keeter, 1996), and tend thus to rely on cognitive heuristics when making up their mind on political matters (e.g., Sniderman et al., 1991; Lau et al., 2001). Since the personality profile of candidates is hard to hide (and is often explicitly showcased for electoral purposes), it provides ready-to-use cues for voters to gauge what they can expect from a given candidate if elected.

Of course, the personality profile of voters is equally likely to matter for their choices (e.g., Chirumbolo and Leone, 2010; Mondak, 2010; Nai and Maier, 2020a). including when it comes to candidate perception. Most notably, consistent evidence exists that candidate and voter traits are systematically linked to each other, in such a way that that voters are more likely to support candidates with personalities that “match” their own (e.g., Caprara et al., 2003; Caprara and Zimbardo, 2004; Fortunato et al., 2018). However, as this is also the case with respect to partisanship – voters strongly prefer candidates of “their” party – disentangling the specific effect of personality from the effects of partisanship is not a trivial task. Indeed, much evidence exists that the perception of candidates' personality traits is a direct function of partisan preferences(e.g., Hyatt et al., 2018; Nai and Maier, 2019; Fiala et al., 2020).

In this article, we attempt to contribute to a better understanding of how candidates’ (perceived) personality traits influence their likeability, and the role of voters’ individual differences and partisanship. Using an innovative survey experiment among U.S. respondents we demonstrate that 1) the public at large dislikes politicians scoring higher on “nefarious” personality traits; 2) voters that themselves score higher on those “dark” personality traits tend to like dark candidates; 3) the effects of candidates’ personality traits are, in some cases, stronger for respondents with weak partisan attachments.

There is a long tradition that aims to conceptualize, measure, and describe individual personality traits. The Big Five Inventory (BFI; McCrae and John, 1992) is the most studied personality inventory, and the most widely used to study the effects of personality on political attitudes and behavior (e.g., Mondak, 2010). The inventory identifies five “general” personality traits (extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, emotional stability, and openness). More recent studies suggest that humans, in addition to the rather positively valenced traits assessed via the BFI, can have socially aversive - yet non-pathological - traits (Moshagen et al., 2018). The so-called “Dark Triad” identifies three “malevolent” components: narcissism, psychopathy, and Machiavellianism (Paulhus and Williams, 2002). These components have been shown to be associated to political attitudes and behaviors (e.g., Arvan, 2013; Jonason, 2014). In a nutshell, psychopathy is “the tendency to impulsive thrill-seeking, cold affect, manipulation, and antisocial behaviors” (Rauthmann, 2012, p. 487), narcissism is “the tendency to harbor grandiose and inflated self-views while devaluing others [… and to] exhibit extreme vanity; attention and admiration seeking; feelings of superiority, authority, and entitlement; exhibitionism and bragging; and manipulation” (Rauthmann, 2012, p. 487) and Machiavellianism is the tendency to harbor “cynical, misanthropic, cold, pragmatic, and immoral beliefs; detached affect; pursuit of self-beneficial and agentic goals (e.g., power, money); strategic long-term planning; and manipulation tactics” (Rauthmann, 2012, p. 487).

There are good reasons to expect that voters tend to dislike candidates with such dark traits. Individuals higher in psychopathy tend to have a more lenient approach to anti-social behaviors, which they often lack the ability to recognize. They tend furthermore to be impulsive and prone to callousness, and often show a strong tendency towards interpersonal antagonism (Jonason, 2014). Indeed, candidates scoring higher on psychopathy tend to display a “confrontational, antagonistic and aggressive style of political competition” (Nai and Maier, 2020b, p. 2). Like psychopathy, narcissism has been shown to predict more successful political trajectories (Watts et al., 2013), also in part due to the prevalence of social dominance intrinsic in the trait. This being said, narcissism is often linked to overconfidence and deceit (Campbell et al., 2004), a marked preference for hypercompetitiveness (Watson et al., 1998), reckless behavior and risk-taking (Campbell et al., 2004). Narcissists tend to go to great lengths to promote themselves and have indeed been shown to likely engage in angry/aggressive behaviors and general incivility in their workplace (Penney and Spector, 2002). Like psychopathy, Machiavellianism also has an aggressive and malicious side (Rauthmann and Kolar, 2013). People higher in Machiavellianism tend to display “cynical and misanthropic beliefs, callousness, a striving for argentic goals (i.e., money, power, and status), and the use of calculating and cunning manipulation tactics” (Wisse and Sleebos, 2016, p. 123), and in general show a proclivity to engage in malevolent behaviors intended to “seek control over others” (Dahling et al., 2009). Indeed, behavioral evidence suggests that higher Machiavellianism is associated with bullying at work (Pilch and Turska, 2015) and the use of more aggressive forms of humor (Veselka et al., 2010).

All in all, candidates higher in the Dark Triad should be more likely to adopt more aggressive behavioral patterns, as shown for instance in Nai and Maier (2020b) with respect to the use of a harsher communication style. Since all three components of the Dark Triad - narcissism, psychopathy, and Machiavellianism - point towards the direction of anti-social behavior, and voters tend to prefer leaders with a positive personality (Aichholzer and Willmann, 2020), we expect that voters tend, on average, to dislike “dark” candidates. We therefore expect:

H1. Exposure to candidates with dark personality traits reduces positive feelings for the candidate.

Importantly, we do not expect this general effect to exist across the board. Recent advances in the literature on elite cues and electoral behavior have clearly demonstrated that individual differences matter. For instance, Weinschenk and Panagopoulos (2014) show that respondents higher in agreeableness can be discouraged to turn out when exposed to negative campaigning messages. Similarly, the usage of “aggressive metaphors” tend to mobilize voters with “aggressive traits” and demobilizes strong partisans lower in aggression (Kalmoe, 2019). Mutz and Reeves, (2005) show that exposure to uncivil content lowers political trust in respondents that dislike conflicts, Nai and Maier, (2020a) present several instances in which darker personality traits of voters meaningfully moderate the effectiveness of negative and uncivil campaign messages. Beyond communication dynamics, Bakker et al., (2016) show that it is especially voters scoring lower on agreeableness that tend to appreciate populist candidates (who themselves score particularly lower on agreeableness, Nai and Martinez i Coma, 2019).

All in all, we have strong reasons to expect individual differences in voters to moderate the effect of candidates’ personality traits. First, we expect that the detrimental role of the dark personality profile of candidates, expected to exist in general (H1), does not exist among a specific set of respondents: those who themselves score higher on those dark traits. The rationale supporting this expectation is twofold. On the one hand, increasing evidence exists that voters with “darker” personality profiles tend to like darker politics - be it in terms of exposure to more negative and uncivil campaigns (Weinschenk and Panagopoulos, 2014; Nai and Maier, 2020a), or in terms of support for more confrontational and aggressive candidates (e.g., Bakker et al., 2016). On the other hand, this mechanism perfectly overlaps with the general “homophily” (or “congruence”) effect - that is, the established notion that voters are often more likely to support candidates with personalities that “match” their own (Caprara et al., 2003; Caprara and Zimbardo, 2004; Caprara et al., 2007; but see; Klingler et al., 2018). As summarized by Caprara and Vecchione (2017), personality “traits represent important elements through which the similarity-attraction principle may operate in politics because they allow voters to organize their impression of politicians, to link politicians’ perceived personalities to their own, and ultimately to justify their preferences on the assumption that similarity in traits carries similarity in worldview and values. Therefore, the more voters acknowledge their own pattern of behavior in a political leader, the more they may assume that the leader in question also shares their own principles” (Caprara and Vecchione, 2017, p. 236). We thus expect the following:

H2. Exposure to candidates with dark personality traits increases positive feelings for the candidate among respondents with dark personality traits.

We also expect the attitudinal profile of respondents to play a moderating role - more specifically, the strength of their partisan identification. Countless studies have shown that strong partisan affiliation (strong partisanship) is a central factor in determining how voters receive, accept, sample and process (new) political information. Voters unconsciously act as motivated reasoners (Kunda, 1990) and tend to reject information that is inconsistent with their attitudes and previously held beliefs (Druckman, 2012; Taber and Lodge, 2016). Because strong partisanship helps voters navigate the complex and treacherous waters of contemporary politics, it is no surprise that party attachment is one of the most important cognitive heuristics in their toolbox (Lau and Redlawsk, 2001; Schaffner and Streb, 2002; Fortunato and Stevenson, 2019). What happens when this navigation tool is absent? For voters that do not rely on (strong) partisanship to guide their political perceptions – a continuously increasing slice of the population in Western democracies (e.g., Dalton 2019) – we argue the following: exposure to the personality of candidates can act as “thin slices” - that is, “brief excerpt[s] of expressive behavior sampled from the behavioral stream” (Ambady et al., 2000, p. 203; see also; Spezio et al., 2012) - and heuristically provide them with schemata on which they develop their judgment. Voters heuristically compensate the lack of information they suffer from when they make judgments about political candidates (e.g., Huckfeldt et al., 2005). They use “evaluative impression formation of candidates by organizing and summarizing a diverse body of information in relatively simple terms [… which] ultimately determine voters’ likes and dislikes of candidates” (Caprara et al., 2002, p. 78). In other terms, we expect the effect of exposure to personality vignettes to be generally more effective, that is, more strongly associated with differences in candidate perception, for voters with weak partisan attachment.

H3. Candidates personality traits have stronger effects on candidate likeability among respondents with weak party attachment.

The main objective of this article is to assess the effect that (dark) personality profiles of political candidates have on shaping how voters perceive them - both directly, and as a function of individual differences in voters themselves (personality, partisanship). Unfortunately, disentangling the effects of candidates’ personality on voters’ perceptions is an arduous task. Voters’ perception of political figures is likely to reflect their underlying partisan preferences. For instance, there is consistent evidence that liberals have a much more critical perception of Donald Trump than conservatives. The former mostly highlight Trump’s lower agreeableness, lower conscientiousness, and lower emotional stability, whereas the latter rate the President higher on all the Big Five, and especially on openness and conscientiousness (e.g., Hyatt et al., 2018; Nai and Maier, 2019; Fiala et al., 2020). In this case, assessing how voters perceive specific personality traits - and the effects of such perceptions - is contaminated by their (pre-existing) political opinions about Trump refracted through the lens of partisanship.

In this article we tackle this issue via innovative experimental data. We present what is, to the best of our knowledge, the first study that manipulates the personality profile of a candidate along well-established personality inventories - and assesses its subsequent effects in terms of voters’ perceptions (however, see Rehmert, 2020 and de Geus et al., 2020, for examples of studies that use conjoint experiments to manipulate other salient aspects of the personal profiles of candidates, such as gender or socio-economic background). The design, embedded in an online survey distributed to a convenience sample of US respondents (MTurk, N = 1,971), exposed respondents randomly to one of eight different “vignettes” presenting personality cues for a fictive candidate - one vignette for each of the five general traits (Big Five) and one for each of the three “nefarious” traits of the Dark Triad. Respondents were asked to rate the personality of the candidate they were exposed to using the traditional abbreviated personality measures (the “TIPI” for the Big Five and the Dirty Dozen for the Dark Triad) and were subsequently asked to give an overall assessment of the candidate (thermometer).

Via this innovative experimental setup – a research design able to disentangle the effects of candidate personality, perceived traits, and voter’s preferences in such a way that their partisan preferences do not come into play - our analyses provide rather consistent support for our hypotheses. Our results will show that 1) the public at large dislikes “dark” politicians, and rates them significantly and substantially lower in likeability; 2) voters that themselves score higher on “dark” personality traits (narcissism, psychopathy, Machiavellianism) tend to like dark candidates, in such a way that the detrimental effect observed in general is completely reversed for them; 3) the effects of candidates’ personality traits are, in some cases, stronger for respondents displaying a weaker partisan attachment.

All materials, data, and syntaxes are available for replication in the following OSF repository: https://osf.io/wxruy/

In May 2020 we fielded a survey among a convenience sample of 2,010 US respondents via Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (MTurk; Paolacci and Chandler, 2014), an online crowd-sourced data platform. MTurk provides convenience samples, which should not be assumed to be representative of the general US population. In this sense, they are ill-suited to provide information to project general trends to the population at large (e.g., electoral predictions based on voting intentions). Nonetheless, MTurk surveys have been shown to perform quite well when compared to other convenience samples (Berinsky et al., 2012), because they tend to mirror the psychological divisions of liberals and conservatives in the US general population (Clifford et al., 2015). MTurk samples seem thus to represent a cheap and reliable way to collect systematic data from convenience samples (Hauser and Schwarz, 2016) - but see, for a more critical take, Harms and DeSimone (2015) and Ford (2017).

MTurk participants were invited to fill in a short online survey against a small compensation ($0.7). The questionnaire included an “attention check” (Berinsky et al., 2014) where specific instructions - select the option “other” and write a keyword in the entry box - were embedded within a long and digressing question. Respondents that failed such attention check (N = 39, 1.9%) were assumed to only skim through the questions and were excluded. The analyses are run on a final sample of N = 1,971 respondents. The final sample is composed of 49% of female respondents, and the average age is 42 years. The sample is mostly composed of white/Caucasian respondents (75%), followed by blacks/African-Americans (12%). 41% of respondents declare being “very interested” in politics, and only 2% declare “no interest at all”. The average self-reported left-right position is 4.8 (SD = 3.1) on a 0–10 scale.

The survey included an experimental component in which we “simulated” the personality traits of a fictive candidate. We created eight imaginary magazine interviews with a fictive candidate - independent Paul A. Bauer, running for a seat in the US House of Representatives for Minnesota's 9th Congressional district.1 Each mock interview was set up to cue respondents towards a specific personality trait of the fictive candidate, using both the framing of the journalist conducting the interview and the candidate response. For instance, the introductory paragraph the interview intended to cue higher extraversion (henceforth: “extraversion vignette”), reads as follows (excerpt):

“Bauer is a rising star in politics but is still relatively unknown to the public at large. Acquaintances describe him as enthusiastic and outgoing, but also as extremely talkative. I asked him three short questions, and found him to be extraverted and warm.”

After this initial introduction, tailored to the specific trait we wanted to cue, all mock interviews (“vignettes”) were set up as a series of questions and answers about what their usual day looks like and their perception of what politics is, similar to interviews that one might encounter reading the back page of a magazine like Newsweek. For instance, the “emotional stability vignette” reads as follows for the answer to the journalist question “what is politics to you?”:

“Politics is being able to take the best decision in the most calm and nuanced way possible. Impulsivity cannot have a place in politics. At the end of the day, only nuanced and rational decisions matter.”

Finally, the fictive candidate was asked to identify which “fictional character” he would like to be “for just a single day.” The use of fictional character to illustrate personality traits and facets is relatively common in the literature. For instance, Jonason et al. (2012) refer, to illustrate the dark traits of narcissism, psychopathy and Machiavellianism, to the fictive characters of James Bond, Hannibal Lecter, and House, M.D. Similarly, Schumacher and Zettler (2019) contrasts the two opposed personas of the fictive US presidents Josiah Bartlett (The West Wing) and Frank Underwood (House of Cards) to illustrate higher and lower scores on the “Honesty-Humility” trait in the HEXACO inventory. Drawing inspiration from these works, the fictional candidate refers in the interview to two fictive characters he would like to be for one day, with the idea that such characters reflect his personality, thereby amplifying the cueing potential of the vignette.2 The mock magazine interview included a picture of the fictive Paul A. Bauer; in actuality a portrait of former Swiss federal councilor Didier Burkhalter, who reflects, in our opinion, a perfectly generic stereotype of the political norm: a “normal” white, middle-aged male candidate.

After random exposure to one of the eight “personality vignettes”, respondents were asked to rate the candidate using two “short” personality batteries: the “TIPI” for the Big Five (Gosling et al., 2003) and the “Dirty Dozen” for the Dark Triad (Jonason and Webster, 2010). The former is set up as a battery of 10 statements about the candidate (e.g., “the candidate might be someone who is extraverted, enthusiastic,” “anxious, easily upset”), which respondents had to evaluate; pairs of statements yield scores on the five traits in the Big Five inventory. The latter is a battery of 12 statements (e.g., “the candidate might be someone who tends to want others to pay attention to him,” “… tends to be cynical”); the average of three sets of four statements yield scores for each trait in the Dark Triad. Using abbreviated measures of personality traits is not without its critics. Very brief measures (e.g., 1-item and 2-item scales, like the TIPI) have been shown to substantially underestimate the role personality traits appear to play when it comes to political behaviour, thereby increasing the odds of generating Type I and Type II errors (Credé et al., 2012). Bakker and Lelkes (2018) also show that abbreviated measures of personality traits tend to underestimate the relationship between ideology and personality traits and that researchers should ideally utilize more elaborate measures (e.g., 20-item or 50-item batteries). We have nonetheless chosen to use the 10-item “TIPI” battery in this research for pragmatic reasons: as it occupies the proverbial “middle ground” between the (extremely abbreviated) measures critiqued by Credé et al. (2012) and the ideal yet unwieldy measures proposed by Bakker and Lelkes (2018), it therefore represents an acceptable trade-off between feasibility and reliability for the purposes of our study.

A series of t-tests shows that respondents that were exposed to a vignette for a specific trait (e.g., extraversion) systematically rated the candidate as significantly higher on that trait when compared to the average of the other seven traits: t(1,969) = −13.77, p < 0.001 (extraversion), t(1,969) = −13.56, p < 0.001 (agreeableness), t(1,969) = −5.61, p < 0.001 (conscientiousness), t(1,969) = −11.23, p < 0.001 (emotional stability), t(1,969) = −7.85, p < 0.001 (openness), t(1,969) = −11.48, p < 0.001 (narcissism), t(1,969) = −13.81, p < 0.001 (psychopathy), and t(1,969) = −16.81, p < 0.001 (Machiavellianism). On average, thus, the “personality vignettes” were quite successful: they evoked in the mind of the respondents the personality profile that we intended to manipulate in the first place. Supplemental Figure SA in the Appendix illustrates the average score on all the personality traits for the fictive candidate as estimated by the respondents, depending on which vignette they were exposed to (bars in each panel).

Randomization checks indicate a successful random distribution of respondents according to their age, party identification, and personality traits (even if some marginal differences exist for some traits). Our tests indicate that female respondents were more likely to be exposed to a positive treatment and male more likely to be exposed to a negative treatment; the difference is statistically significant, χ2(1, N = 1964) = 9.87, p = 0.002. To exclude any confounding effects, we will replicate all analyses discussed below controlling for the gender of the respondents; see robustness checks discussed in Robustness Checks.

The dependent variable in all our analyses - the way respondents feel about the candidate, or more simply candidate likability - is simply measured using the “feeling thermometer” developed by the ANES research group (Wilcox et al., 1989). Responses range on a 0–100 scale where low scores signal an unfavorable or “cold” opinion and high scores a favorable or “warm” one (M = 58.38, SD = 26.18).

The questionnaire included a series of questions intended to measure party proximity. First respondents were asked whether they think of themselves as a Democrat, a Republican, and Independent, or if they have no preference. Respondents that selected the first two options were then asked whether they would call themselves a strong or a not very strong Democrat (Republican). Respondents that selected the other options (independents or non-aligned) were given the chance to indicate if they feel close to the Democrats, Republicans, or neither. The combination of these different questions yields a 5-point scale, taking the values 1 for “Strong Democrat” (25.1%), 2 for “Leaning Democrat” (respondents that feel weakly attached to the Democratic party or that declared themselves independents but feel closer to that party; 26.9%), 3 for “Independent” (including those who do not lean in either direction; 11.7%), 4 for “leaning Republican” (19.2%), and 5 for “Strong Republican” (17.1%).

Using some of these variables we have also created a simplified binary variable of strength of partisan attachment. Because Independents cannot be considered as having a weak ideological identity, we have excluded all respondents that declare themselves “Independents” (or anything else than D or R) in the initial question above. Strength of partisanship is thus computed among respondents that think of themselves as either a Republican or a Democrat, and takes the value 0 if this identification is perceived as weak, and 1 if this identification is perceived as strong. Among those respondents, 42.1% have a weak partisan attachment, and 57.9% have a strong one.

Prior to the experimental component we also measured the respondents’ personality traits, using the same scales used afterwards for the candidates - the “TIPI” for the Big Five inventory (Gosling et al., 2003) and the “Dirty Dozen” for the Dark Triad (Jonason and Webster, 2010). All inventories yield scales that range from 1 “Very low” to 7 “Very high.” Figure 1 plots the distribution of respondents on the eight traits. The average score on the three “dark” traits of narcissism, psychopathy, and Machiavellianism reflects a unified measure of the “dark core” (e.g., Paulhus and Williams, 2002; Book et al., 2015; Moshagen et al., 2018; M = 3.02, SD = 1.36; α = 0.82).

Does exposure to candidates with a dark personality drive more negative perceptions of these candidates? And, if so, for whom? This section presents evidence suggesting that the personality of candidates goes a long way indeed - and especially for some.

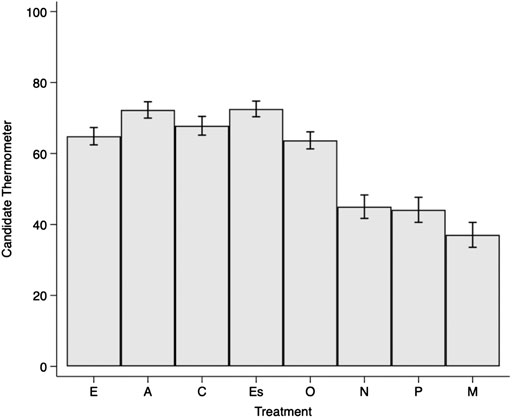

To what extent is the (perceived) personality of political candidates associated with their likeability by the public at large? Are agreeable candidates more likeable? Are narcissists disliked? Table 1 regresses the scores on the feeling thermometer for the candidate (0–100) on the personality vignette respondents were exposed to. Because conscientiousness represents an ideal trait for political leaders (and is also the trait that is more likely to drive better electoral results for competing candidates; Nai, 2019), we use exposure to the conscientiousness vignette as the reference category - that is, the effects of exposure to the other vignettes are computed against exposure to this vignette. Model M1 shows that candidates framed as higher in agreeableness and emotional stability receive somewhat higher ratings on the feeling thermometer, whereas candidates framed as higher in openness receive lower scores. But it is for the Dark Triad that we see the most impressive effects. Compared to candidates framed higher in conscientiousness, candidates framed with narcissistic, psychopathic, and, especially, Machiavellian traits receive significantly and substantially lower thermometer scores - up to 30 points less for Machiavellianism. The average thermometer score associated with all vignettes is illustrated in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2. Feeling thermometer per candidate personality vignette. Big Five: E ‘Extraversion’, A ‘Agreeableness’, C ‘Conscientiousness’, Es ‘Emotional Stability’, O 'Openness’ Dark Triad: N ‘Narcissism’, P ‘Psychopathy’, M ‘Machiavellianism’

Model M2 then estimates the thermometer score of the candidate as a function of respondents’ exposure to a “socially desirable” personality vignette (one of the Big Five, reference category) or rather to a “socially nefarious” vignette (one of the Dark Triad traits). Exposure to a dark trait, compared to exposure to a Big Five trait, reduces positive feelings for the candidate up to 26 points. Models M1 and M2 confirm, in other terms, that darker personality traits are detrimental for the likeability of competing candidates. The public at large, it seems, dislikes dark politicians.

Model M3 controls for respondents’ partisan identification and adds an interaction term between partisan identification and type of personality vignette (Dark Triad or Big Five) respondents were exposed to. There is no direct effect of party identification – which makes sense as the fictional candidate has been introduced as an Independent. The significant interaction in Model M3 shows that exposure to a “dark” vignette yields slightly higher thermometer scores for respondents identifying as a (strong) Republican. This reflects results in the literature showing that dark personality traits are more likely to be expressed among (strong) conservatives (e.g., Jonason, 2014). The effect is however not particularly strong.

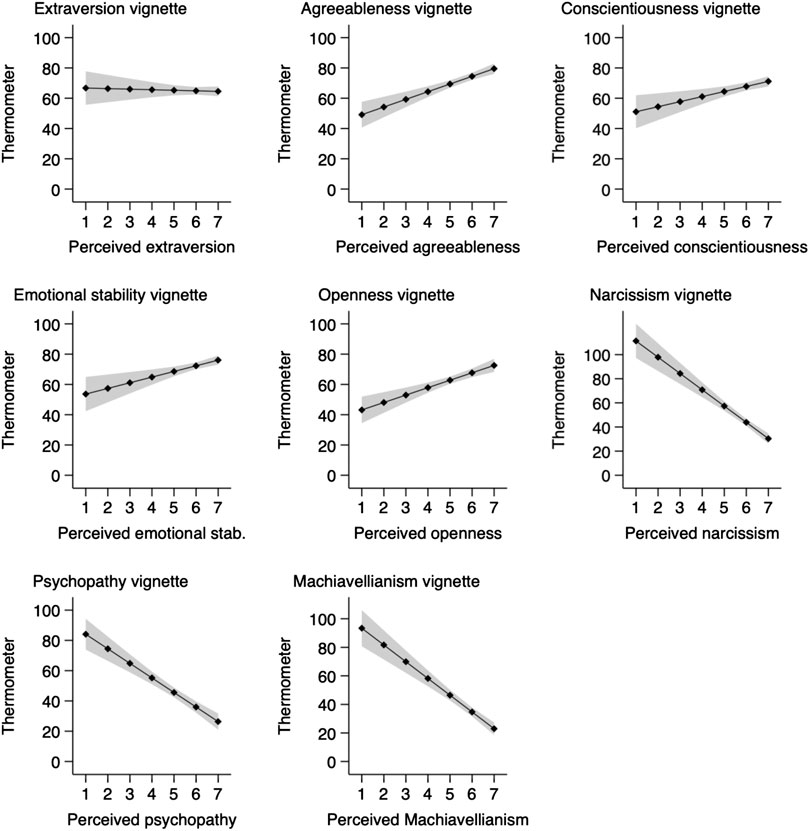

Beyond simple exposure to personality cues, perceived personality traits of the candidates are likely to matter. For instance, it would not matter that a respondent is exposed to a narcissist candidate if they do not perceive the candidate as particularly higher on that trait. With this in mind Figure 3 plots, for each trait, the marginal effect of trait perception on the candidate likeability (feeling thermometer). For each panel in Figure 3, the models estimate how respondents feel about the candidate (thermometer) as a function of how high they perceive the candidate to score on the trait, depending on which vignette they were exposed to. Thus, for instance, the top-right panel is only run for respondents exposed to the “conscientiousness” vignette and estimates the marginal effects of perceived candidate conscientiousness (1-7 scale on the x-axis) on the feeling thermometer.

FIGURE 3. Feeling thermometer by perceived personality trait. In all models the dependent variable is the feeling thermometer for the fictive candidate, and ranges between 0 “very cold” and 100 “very warm” feelings towards him. Marginal effects with 95% confidence intervals, based on coefficients in Supplementary Table SA1 (Appendix).

As the figure shows, for all personality traits - excluding extraversion (top-left panel) - the more respondents perceive the candidate as scoring higher on the trait in question, the stronger its effects on the thermometer. Full results are in Supplementary Table SA1 in the Appendix.

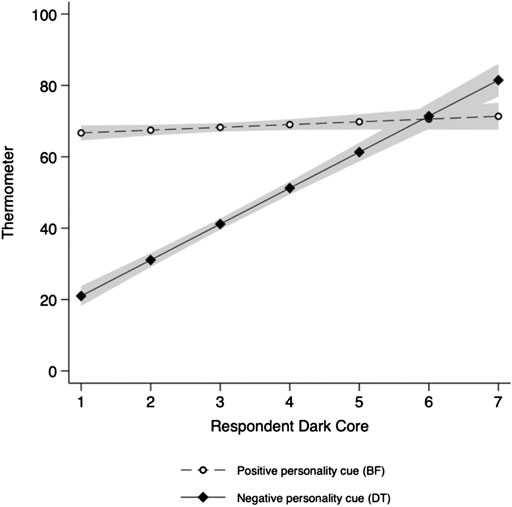

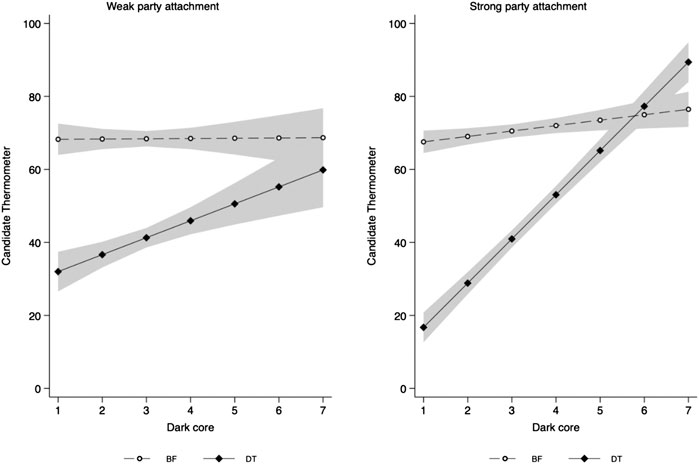

Results discussed above regarding the partisan identification of respondents - that is, that exposure to a “dark” vignette yields slightly higher thermometer scores for respondents identifying as (strong) Republican(s) - support the idea that the personality of candidates does not play uniform roles across the electorate. Evidence discussed in Bakker et al. (2016), for instance, shows that it is especially voters scoring lower on agreeableness that tend to appreciate populist candidates (themselves scoring particularly lower on agreeableness, Nai and Martinez i Coma, 2019). Similarly, recent experimental evidence shows “darker” forms of political communication, such as negativity and incivility, are appreciated by voters with specific personality profiles (e.g., Weinschenk and Panagopoulos, 2014; Nai and Maier, 2020a). With this in mind, the question is then: to what extent is the effect of candidates’ personality traits on their likeability a function of the personality of the respondents themselves? Table 2 tests for the moderating role of respondent’s personality (dark core) on the effects of exposure to dark personality vignettes on the thermometer scores. M1 shows a significant interaction term, substantiated with marginal effects in Figure 4.

FIGURE 4. Feeling thermometer by candidate and respondent personality traits. In all models the dependent variable is the feeling thermometer for the fictive candidate, and ranges between 0 “very cold” and 100 “very warm” feelings towards him. Marginal effects with 95% confidence intervals, based on coefficients in Table 2, Model M1.

As Figure 4 shows clearly, not only does the respondents’ (dark) personality moderate the effects of the candidate’s personality, but it reverses the negative effect shown across all respondents. This means that higher scores on the feeling thermometer are a function of increasing levels of dark personality of respondents themselves (dark core, representing the average scores on narcissism, psychopathy, and Machiavellianism) - but only for respondents exposed to a “dark” vignette. For respondents scoring lower on the dark core it is exposure to positive personality traits (Big Five) that drives higher thermometer scores. Simply put: dark voters like dark candidates. This effect does not seem to be further moderated by the partisan affiliation of the respondent (M2).

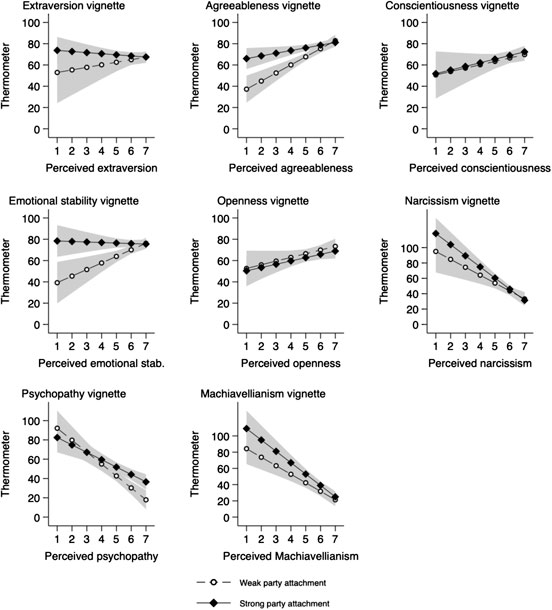

We also expected respondents with a weaker party identification to be more likely to be affected by the candidate’s personality cues - because they are more likely to use such cues heuristically. Supplementary Table SA2 in the Appendix reports a series of models where we have regressed, for each personality vignette, the candidate thermometer scores on the interaction between perceived candidate personality and the respondent strength of partisanship (binary variable, 0 low, 1 strong). Figure 5 substantiates all interaction effects in Supplementary Table SA2, with marginal effects. Each panel represents respondents exposed to a specific personality vignette (e.g., extraversion in the top-left panel), and the graph reflects the estimated marginal thermometer scores as a function of perceived trait (x-axis) for respondents with weak party attachment (white circles) and strong party attachment (black diamonds). We find significant interaction terms in three cases - agreeableness, emotional stability, and psychopathy (respectively, models M2, M4, and M7 in Supplementary Table SA2). In all three cases, the effect of the personality vignettes shown before for all respondents (Table 1) is stronger for respondents with a weak party attachment compared to those with a strong attachment. The effect is particularly visible for agreeableness and emotional stability. Put otherwise, for these three traits we can confirm the expectation that respondents with weak party attachment use cues related to the personality of candidates to make up their mind about the likeability of said candidates - much more so compared to respondents with strong party attachment.

FIGURE 5. Feeling thermometer by perceived personality trait, by strength of party attachment. In all models the dependent variable is the feeling thermometer for the fictive candidate, and ranges between 0 “very cold” and 100 “very warm” feelings towards him. Marginal effects with 95% confidence intervals, based on coefficients in Supplementary Table SA2 (Appendix).

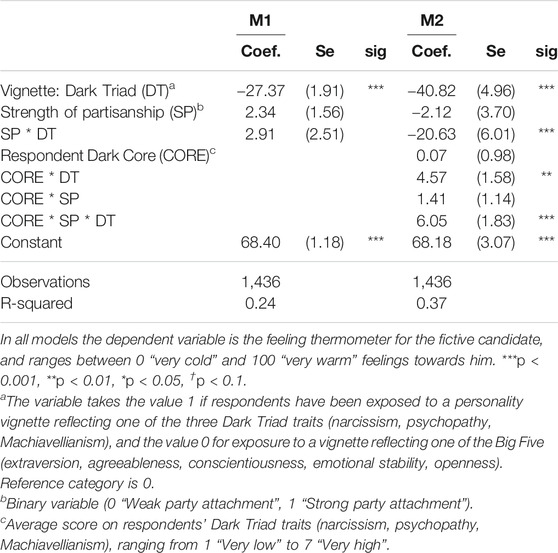

Table 3 reports results of a simplified test for the moderating effect of party strength, contrasting only exposure to a “socially desirable” personality vignette (one of the Big Five, reference category) instead of a “socially nefarious” vignette (one of the Dark Triad traits). Model M1 illustrates the absence of interaction effects between this simplified measurement of simulated personality and intensity of party strength - confirming the idea, discussed above, that this interaction exists only for specific traits and not across the board. Furthermore, M2 suggests that the moderating role of party strength is also a function of respondents’ dark personality traits. As substantiated in Figure 6 with marginal effects, the three-way interaction shows that it is especially among respondents scoring higher on the “dark core” that weak party attachment increases the effect of dark personality cues (left-hand panel), and that this effect exists also, and more strongly so, among respondents with high party attachment. In other terms, if strength of party attachment seems to have specific effects for specific traits, it does not moderate the effectiveness of personality cues across the board. Furthermore, its effect is clearly overshadowed by the strong moderating role of the dark personality traits of respondents.

FIGURE 6. Feeling thermometer by exposure to candidate personality vignettes, respondents’ dark traits, and strength of partisanship. In all models the dependent variable is the feeling thermometer for the fictive candidate, and ranges between 0 “very cold” and 100 “very warm” feelings towards him. Marginal effects with 95% confidence intervals, based on coefficients in Table 3 (Model M2).

TABLE 3. Feeling thermometer by exposure to candidate personality vignettes, respondents’ dark traits, and strength of partisanship.

All results presented above resist models with alternative specifications. The same results are found in models that exclude respondents living in Minnesota (thus potentially privy of the deception in our experimental manipulation; N = 26), and in models that do not exclude “shrinkers” that failed the attention check (N = 39). Replication materials in the OSF repository include all specifications for these additional robustness checks. Finally, all results resist controlling the models by the gender of the respondent; the fact that male and female respondents were not randomly distributed across experimental conditions, as described beforehand, does not seem to affect the results.

Differences between candidates are often framed merely as policy differences. For instance, shortly before the 2020 US presidential election Nature highlighted the contrasting approaches and policy proposals put forth by Biden and Trump to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic and climate change (Maxmen et al., 2020).

This paper argues that not only policy differences matter but also differences in candidates’ personality when it comes to voter perferences. Using an innovative experimental design in which we manipulated the personality profile of a fictitious candidate – we randomly exposed subjects to vignettes created to cue one of the five general traits (Big Five) or one of the three “nefarious” traits of the Dark Triad – we demonstrated that the public at large dislikes “dark” politicians, and rates them significantly and substantially lower in likeability. Furthermore, our findings suggest that the personality profile of voters and the (perceived) personality profile of candidates interact with each other. Voters are more likely to prefer candidates with personalities that “match” their own. In particular, the analyses found that voters that themselves score higher on “dark” personality traits (narcissism, psychopathy, Machiavellianism) tend to like dark candidates. The magnitude of this effect is so substantial that the detrimental effect observed in general is completely reversed for them. Finally, the study demonstrated that the effects of candidates’ personality traits are, in some cases, stronger for respondents that have weaker partisan attachments.

Such results underline the relevance of personality for political decision making. Voters take into account the personality of candidates when forming judgments, above and beyond partisanship.

Although our research design is innovative (we are not aware of studies in political communication that manipulate the personality traits of candidates in a similar fashion), it also comes with limitations. First, independent candidates are rather rare; in the 2018 Midterm election they received only about 2.5% of the votes cast for the House of Representatives (Federal Election Commission, 2019: 9). Hence, it is unclear whether the effects we find can be generalized for candidates running for the Democratic or the Republican Party. A clear partisan identification of the candidate (e.g., Republican) would have been more realistic and generalizable, but would have introduced the confounding role of respondents’ partisanship into our design. Because voters’ perception of political figures has been shown to be a function of their partisan preferences (e.g., Hyatt et al., 2018; Nai and Maier, 2019; Fiala et al., 2020), assigning a clear partisan identity to the fictive candidate would have introduced a perceptual bias in both how respondents assess the profile of the candidate (personality traits) and their general evaluation (thermometer) - which we feared not being able to disentangle empirically. Furthermore, because personality traits are themselves not independent from political leaning (e.g., liberals tend to score higher on openness; Jonason, 2014; Xu et al., 2020), assigning a clear partisan identity to the candidate would likely make some traits more “in character”, thus potentially introducing another source of perceptual bias. Using an independent candidate allows to directly “control out” the driving role of respondents’ partisanship in assessing the personality of the candidate.

Second, the relatively complex nature of the vignettes (candidate description, answers to questions, and references to fictive characters) makes it harder to estimate precisely the contribution of each specific element in regards to the effects they caused. Of course, all experimental components were unique to each specific vignette, and as such worked conceptually as a whole to cue respondents about the profile of the candidate. But, even if manipulation checks were successfull on the whole, more specific checks for each of the active components would have helped disentangle the unique contribution of the specific elements in the vignettes. Third, the fact that the personality of candidates matters should not overshadow the relevance of other characteristics of their profile - their gender, for instance, is often linked with stereotypical perceptions of personality and other candidate characteristics more complex experiments are required. Fourth, it is unclear how important psychological personality traits really are. Models including, e.g., other candidate perceptions (for instance, competence, integrity) as well as a candidate’s stance on important issues are necessary to assess the true impact of psychological personality traits, especially in light of the fact that personality is often contingent to political leanings (and thus, likely, policy propositions). Fifth, this study is limited to a very specific case, the United States, known for harsh electoral competition and entrenched affective polarization (Iyengar et al., 2019). Future comparative research will need to establish whether the driving role of (perceived) candidate personality is also at play in less extremely competitive political arenas, such as more consensual democracies or countries with proportional electoral systems. Finally, our article exclusively assesses the role of candidate personality on voters’ perceptions and attitudes; with the data at hand, we cannot make claims as to whether the dynamics discussed here also matter for downstream behaviors, such as voting choices or turnout. Nonetheless, given the primacy of candidate evaluation for voting choices (e.g., Garzia et al., 2020), it is rather unlikely that the manner in which respondents perceive the personality of candidates, both directly and as a function of their own personality profile, is completely unconnected to their actual political behavior. Further research that is able to extend the dynamics investigated here to include voting behaviors, for instance by triangulating experimental with observational data, is therefore both recommended and necessary.

The data presented in this article, as well as codes and all experimental materials, can be accessed via the following repository for replication purposes: https://osf.io/wxruy/.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Department of Communication Science at University of Amsterdam on 11 May 2020 (ref. 2020-PCJ-12317). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

AN and JM conceived the general idea and developed the theoretical framework. AN and JV developed the initial framing of the experimental treatments and protocol. All three authors designed jointly the treatments and finalized the protocol. AN implemented data collection and performed the computations, also following suggestions by JM. AN wrote the initial draft but all three authors discussed the results and contributed to the final manuscript.

The authors acknowledge the generous financial support from the Amsterdam School of Communication Research (ASCoR) for data collection.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The authors wish to thank the special issue editors and anonymous reviewers for their comments and inputs on previous versions of the article. Any remaining mistakes are of course our responsibility alone. Preliminary trends discussed in this article were presented during the 2020 (virtual) Annual Meeting of the European Consortium for Political Research (ECPR, panel “Personalization in Contemporary Political Communication”); many thanks to all participants for valuable inputs. AN also wishes to thank his fellow members of the LausAmsterdam research group on negative personalization (Loes Aaldering, Fred Ferreira da Silva, Diego Garzia, Katjana Gattermann) for their cutting-edge theoretical and empirical insights.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2021.636745/full#supplementary-material.

1Minnesota has only eight Congressional districts.

2The list of all fiction characters is as follows: Han Solo (Star Wars) and Michael Scott (The Office) for extraversion; WALL-E (Pixar's WALL-E) and Forrest Gump (Forrest Gump) for agreeableness; Hermione Granger (Harry Potter books and movies) and The Batman (Batman movies) for conscientiousness; Samwise Gamgee (The Lord of the Rings book and movies) and Sancho Panza (Don Quixote) for emotional stability; Lisa Simpson (The Simpsons) and Huckleberry Finn (The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn) for openness; James Bond (James Bond movies and novels) and Miranda Priestly (The Devil Wears Prada) for narcissism; Hannibal Lecter (The Silence of the Lambs) and Sarah Connor (The Terminator) for psychopathy; House, M.D (House, M.D) and Frank Underwood (House of Cards) for Machiavellianism.

3For transcripts see https://www.debates.org/voter-education/debate-transcripts/september-29–2020-debate-transcript/;https://eu.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/elections/2020/10/23/debate-transcript-trump-biden-final-presidential-debate-nashville/3740152001/

Aichholzer, J., and Willmann, J. (2020). Desired personality traits in politicians: similar to me but more of a leader. J. Res. Personal. 88, 103990. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2020.103990

Ambady, N., Bernieri, F. J., and Richeson, J. A. (2000). Toward a histology of social behavior: judgmental accuracy from thin slices of the behavioral stream. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 32, 201–271. doi:10.1016/S0065-2601(00)80006-4

Arvan, M. (2013). Bad news for conservatives? Moral judgments and the Dark Triad personality traits: a correlational study. Neuroethics 6 (2), 307–318. doi:10.1007/s12152-011-9140-6

Bakker, B. N., and Lelkes, Y. (2018). Selling ourselves short? How abbreviated measures of personality change the way we think about personality and politics. J. Polit. 80 (4), 1311–1325. doi:10.1086/698928

Bakker, B. N., Rooduijn, M., and Schumacher, G. (2016). The psychological roots of populist voting: evidence from the United States, The Netherlands and Germany. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 55 (2), 302–320. doi:10.1111/1475-6765.12121

Berinsky, A. J., Huber, G. A., and Lenz, G. S. (2012). Evaluating online labor markets for experimental research: Amazon.com's Mechanical Turk. Polit. Anal. 20 (3), 351–368. doi:10.2307/23260322

Berinsky, A. J., Margolis, M. F., and Sances, M. W. (2014). Separating the shirkers from the workers? Making sure respondents pay attention on self‐administered surveys. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 58 (3), 739–753. doi:10.1111/ajps.12081

Book, A., Visser, B. A., and Volk, A. A. (2020). Average Joe, crooked Hillary and the unstable narcissist. Expert impression of 2016 and 2020 U.S. presidential candidates’ public personas. Retrieved 24 November 2020 from Available at: https://psyarxiv.com/4vypw/.

Book, A., Visser, B. A., and Volk, A. A. (2015). Unpacking “evil”: claiming the core of the dark triad. Personal. Individual Differences 73, 29–38. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2014.09.016

Campbell, W. K., Goodie, A. S., and Foster, J. D. (2004). Narcissism, confidence, and risk attitude. J. Behav. Decis. Making 17 (4), 297–311. doi:10.1002/bdm.475

Caprara, G., Barbaranelli, C., Consiglio, C., Laura, P., and Zimbardo, P. G. (2003). Personalities of politicians and voters: unique and synergistic relationships. J. Pers Soc. Psychol. 84 (4), 849–856. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.849

Caprara, G. V., and Zimbardo, P. G. (2004). Personalizing politics: a congruency model of political preference. Am. Psychol. 59 (7), 581–594. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.59.7.581

Caprara, G. V., Barbaranelli, C., Chris Fraley, R., and Vecchione, M. (2007). The simplicity of politicians' personalities across political context: an anomalous replication. Int. J. Psychol. 42 (6), 393–405. doi:10.1080/00207590600991104

Caprara, G. V., Barbaranelli, C., and Zimbardo, P. G. (2002). When parsimony subdues distinctiveness: simplified public perceptions of politicians’ personality. Polit. Psychol. 23 (1), 77–95. doi:10.1111/0162-895X.00271

Caprara, G. V., and Vecchione, M. (2017). Personalizing politics and realizing democracy. New York: Oxford University Press.

Chirumbolo, A., and Leone, L. (2010). Personality and politics: the role of the HEXACO model of personality in predicting ideology and voting. Personal. Individual Differences 49 (1), 43–48. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2010.03.004

Clifford, S., Jewell, R. M., and Waggoner, P. D. (2015). Are samples drawn from Mechanical Turk valid for research on political ideology? Res. Polit. 2 (4), 1–15.doi:10.1177/2053168015622072

Credé, M., Harms, P., Niehorster, S., and Gaye-Valentine, A. (2012). An evaluation of the consequences of using short measures of the Big Five personality traits. J. Pers Soc. Psychol. 102 (4), 874. doi:10.1037/a0027403

Dahling, J. J., Whitaker, B. G., and Levy, P. E. (2009). The development and validation of a new Machiavellianism scale. J. Manag. 35 (2), 219–257. doi:10.1177/0149206308318618

Dalton, R. J. (2019). Citizen politics. Public opinion and political parties in advanced industrial democracies. 7th Edn. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

de Geus, R. A., McAndrews, J. R., Loewen, P. J., and Martin, A. (2020). Do voters judge the performance of female and male politicians differently? Experimental evidence from the United States and Australia. Polit. Res. Q. doi:10.1177/1065912920906193

Delli Carpini, M. X., and Keeter, S. (1996). What Americans know about politics and why it matters. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Druckman, J. N., and Lupia, A. (2012). Social science. Experimenting with politics. Science 335 (2), 1177–1179. doi:10.1126/science.1207808

Federal Election Commission (2019). Federal elections 2018. Election results for the U.S. Senate and the U.S. House of Representatives. Washington, DC: Federal Election Commission.

Fiala, J. A., Mansour, S. A., Matlock, S. E., and Coolidge, F. L. (2020). Voter perceptions of president Donald Trump’s personality disorder traits: implications of political affiliation. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 8, 2167702619885399. doi:10.1177/2167702619885399

Ford, J. B. (2017). Amazon's Mechanical Turk: a comment. J. Advertising 46 (1), 156–158. doi:10.1080/00913367.2016.1277380

Fortunato, D., Hibbing, M. V., and Mondak, J. J. (2018). The Trump draw: voter personality and support for Donald Trump in the 2016 republican nomination campaign. Am. Polit. Res. 46 (5), 785–810. doi:10.1177/1532673X18765190

Fortunato, D., and Stevenson, R. T. (2019). Heuristics in context. Polit. Sci. Res. Methods 7 (2), 311–330. doi:10.1017/psrm.2016.37

Garzia, D., Ferreira da Silva, F., and De Angelis, A. (2020). Partisan dealignment and the personalisation of politics in West European parliamentary democracies, 1961–2018. West European Politics. doi:10.1080/01402382.2020.1845941

Gosling, S. D., Rentfrow, P. J., and Swann, W. B. (2003). A very brief measure of the Big-Five personality domains. J. Res. Personal. 37 (6), 504–528. doi:10.1016/S0092-6566(03)00046-1

Harms, P. D., and DeSimone, J. A. (2015). Caution! MTurk workers ahead—fines doubled. Ind. Organizational Psychol. 8 (2), 183–190. doi:10.1017/iop.2015.23

Hauser, D. J., and Schwarz, N. (2016). Attentive Turkers: MTurk participants perform better on online attention checks than do subject pool participants. Behav. Res. Methods 48, 400–407. doi:10.3758/s13428-015-0578-z

Huckfeldt, R., Mondak, J. J., Craw, M., and Mendez, J. M. (2005). Making sense of candidates: partisanship, ideology, and issues as guides to judgment. Brain Res. Cogn. Brain Res. 23 (1), 11–23. doi:10.1016/j.cogbrainres.2005.01.011

Hyatt, C., Campbell, W. K., Lynam, D. R., and Miller, J. D. (2018). Dr. Jekyll or Mr. Hyde? President Donald Trump’s personality profile as perceived from different political viewpoints. Collabra: Psychol. 4 (1), 162. 10.1525.collabra.162.pr

Iyengar, S., Lelkes, Y., Levendusky, M., Malhotra, N., and Westwood, S. J. (2019). The origins and consequences of affective polarization in the United States. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 22, 129–146. doi:10.1146/annurev-polisci-051117-073034

Joly, J., Soroka, S., and Loewen, P. (2019). Nice guys finish last: personality and political success. Acta Politica 54, 667–683. doi:10.1057/s41269-018-0095-z

Jonason, P. K., and Webster, G. D. (2010). The dirty dozen: a concise measure of the dark triad. Psychol. Assess. 22 (2), 420. doi:10.1037/a0019265

Jonason, P. K. (2014). Personality and politics. Personal. Individual Differences 71, 181–184. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2014.08.002

Jonason, P. K., Webster, G. D., Schmitt, D. P., Li, N. P., and Crysel, L. (2012). The antihero in popular culture: life history theory and the dark triad personality traits. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 16 (2), 192–199. doi:10.1037/a0027914

Kalmoe, N. P. (2019). Mobilizing voters with aggressive metaphors. Polit. Sci. Res. Methods 7 (3), 411–429. doi:10.1017/psrm.2017.36

Klingler, J. D., Hollibaugh, G. E., and Ramey, A. J. (2018). What I like about you: legislator personality and legislator approval. Polit. Behav. 41 (2), 499–525. doi:10.1007/s11109-018-9460-x

Kunda, Z. (1990). The case for motivated reasoning. Psychol. Bull 108 (3), 480–498. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.108.3.480

Lau, R. R., and Redlawsk, D. P. (2001). Advantages and disadvantages of cognitive heuristics in political decision making. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 45 (4), 951–971. doi:10.2307/2669334

Lilienfeld, S. O., Waldman, I. D., Landfield, K., Watts, A. L., Rubenzer, S., and Faschingbauer, T. R. (2012). Fearless dominance and the U.S. presidency: implications of psychopathic personality traits for successful and unsuccessful political leadership. J. Pers Soc. Psychol. 103 (3), 489–505. doi:10.1037/a0029392

Maxmen, A., Subbaraman, N., Tollefson, J., Viglione, G., and Witze, A. (2020). What a Joe Biden presidency would mean for five key science issues. Nature 586, 177–180. doi:10.1038/d41586-020-02786-4

McCrae, R. R., and John, O. P. (1992). An introduction to the five-factor model and its applications. J. Pers 60 (2), 175–215. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.1992.tb00970.x

McDermott, M. L. (1997). Voting cues in low-information elections. Candidate gender as a social information variable in contemporary United States elections. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 41 (1), 270–283. doi:10.2307/2111716

Mondak, J. J. (2010). Personality and the foundations of political behavior. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Moshagen, M., Hilbig, B. E., and Zettler, I. (2018). The dark core of personality. Psychol. Rev. 125 (5), 656–688. doi:10.1037/rev0000111

Mutz, D. C., and Reeves, B. (2005). The new videomalaise: effects of televised incivility on political trust. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 99 (1), 1–15. doi:10.1017/S0003055405051452

Nai, A., and Maier, J. (2018). Perceived personality and campaign style of hillary clinton and Donald Trump. Personal. Individual Differences, 121, 80–83.

Nai, A., and Maier, J. (2019). Can anyone be objective about Donald Trump? Assessing the personality of political figures. J. Elections, Public Opin. Parties. doi:10.1080/17457289.2019.1632318

Nai, A., and Maier, J. (2020a). Is negative campaigning a matter of taste? Political attacks, incivility, and the moderating role of individual differences. Am. Polit. Res. doi:10.1177/1532673X20965548

Nai, A., and Maier, J. (2020b). Dark necessities? Candidates’ aversive personality traits and negative campaigning in the 2018 American Midterms. Elect. Stud. 68 (1), 102233. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2020.102233

Nai, A., and Martinez i Coma, F. (2019). The personality of populists: provocateurs, charismatic leaders, or drunken dinner guests? West Eur. Polit., 42 (7), 1337–1367. doi:10.1080/01402382.2019.1599570

Nai, A. (2019). The electoral success of angels and demons. Big five, dark triad, and performance at the ballot box. J. Soc. Polit. Psychol. 7 (2), 830–862. doi:10.5964/jspp.v7i2.918

Paolacci, G., and Chandler, J. (2014). Inside the Turk: understanding Mechanical Turk as a participant pool. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 23 (3), 184–188. doi:10.1177/0963721414531598

Paulhus, D. L., and Williams, K. M. (2002). The dark triad of personality: narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy. J. Res. Personal. 36 (6), 556–563. doi:10.1016/S0092-6566(02)00505-6

Penney, L. M., and Spector, P. E. (2002). Narcissism and counterproductive work behavior: do bigger egos mean bigger problems? Int. J. Selection Assess. 10 (1–2), 126–134. doi:10.1111/1468-2389.00199

Pilch, I., and Turska, E. (2015). Relationships between Machiavellianism, organizational culture, and workplace bullying: emotional abuse from the target’s and the perpetrator’s perspective. J. Business Ethics 128 (1), 83–93. doi:10.1007/s10551-014-2081-3

Rauthmann, J. F., and Kolar, G. P. (2013). The perceived attractiveness and traits of the Dark Triad: narcissists are perceived as hot, Machiavellians and psychopaths not. Personal. Individual Differences 54 (5), 582–586. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2012.11.005

Rauthmann, J. F. (2012). The Dark Triad and interpersonal perception: similarities and differences in the social consequences of narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 3 (4), 487–496. doi:10.1177/1948550611427608

Rehmert, J. (2020). Party elites’ preferences in candidates: evidence from a conjoint experiment. Polit. Behav. doi:10.1007/s11109-020-09651-0

Rubenzer, S. J., Faschingbauer, T. R., and Ones, D. S. (2000). Assessing the U.S. Presidents using the revised NEO personality inventory. Assessment, 7 (4), 403–420. doi:10.1177/107319110000700408

Schaffner, B. F., and Streb, M. J. (2002). The partisan heuristic in low-information elections. Public Opin. Q. 66 (4), 559–581. doi:10.1086/343755

Schumacher, G., and Zettler, I. (2019). House of Cards or West Wing? Self-reported HEXACO traits of Danish politicians. Personal. Individual Differences 141, 173–181. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2018.12.028

Sniderman, P. M., Brody, R. A., and Tetlock, P. E. (1991). Reasoning and choice: Explorations in political psychology. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Spezio, M. L., Loesch, L., Gosselin, F., Mattes, K., and Alvarez, R. M. (2012). Thin‐slice decisions do not need faces to be predictive of election outcomes. Polit. Psychol. 33 (3), 331–341. doi:10.2307/23260394

Taber, C. S., and Lodge, M. (2016). The illusion of choice in democratic politics: the unconscious impact of motivated political reasoning. Polit. Psychol., 37, 61–85. doi:10.1111/pops.12321

Veselka, L., Schermer, J. A., Martin, R. A., and Vernon, P. A. (2010). Relations between humor styles and the Dark Triad traits of personality. Personal. Individual Differences 48 (6), 772–774. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2010.01.017

Visser, B. A., Book, A. S., and Volk, A. A. (2017). Is Hillary dishonest and Donald narcissistic? A HEXACO analysis of the presidential candidates’ public personas. Personal. Individual Differences 106, 281–286. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2016.10.053

Watson, P. J., Morris, R. J., and Miller, L. (1998). Narcissism and the self as continuum: correlations with assertiveness and hypercompetitiveness. Imagination, Cogn. Personal. 17 (3), 249–259. doi:10.2190/29JH-9GDF-HC4A-02WE

Watts, A. L., Lilienfeld, S. O., Smith, S. F., Miller, J. D., Campbell, W. K., Waldman, I. D., et al. (2013). The double-edged sword of grandiose narcissism: implications for successful and unsuccessful leadership among U.S. Presidents. Psychol. Sci. 24 (12), 2379–2389. doi:10.1177/0956797613491970

Weinschenk, A. C., and Panagopoulos, C. (2014). Personality, negativity, and political participation. J. Soc. Polit. Psychol. 2, 164–182. 10.5964/jspp.v2i1.280

Wilcox, C., Sigelman, L., and Cook, E. (1989). Some like it hot: individual differences in responses to group feeling thermometers. Public Opin. Q. 53, 246–257. doi:10.1086/269505

Wisse, B., and Sleebos, E. (2016). When the dark ones gain power: perceived position power strengthens the effect of supervisor Machiavellianism on abusive supervision in work teams. Personal. Individual Differences 99, 122–126. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2016.05.019

Keywords: candidate personality, voter personality, dark triad, big five, experiment

Citation: Nai A, Maier J and Vranić J (2021) Personality Goes a Long Way (for Some). An Experimental Investigation Into Candidate Personality Traits, Voters’ Profile, and Perceived Likeability. Front. Polit. Sci. 3:636745. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2021.636745

Received: 02 December 2020; Accepted: 13 January 2021;

Published: 15 March 2021.

Edited by:

Julie Blais, Dalhousie University, CanadaReviewed by:

Aaron Weinschenk, University of Wisconsin–Green Bay, United StatesCopyright © 2021 Nai, Maier and Vranić. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Alessandro Nai, YS5uYWlAdXZhLm5s

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.