Abstract

In the last decade, there has been a significant rise in the number of global social movements, generating claims of a new networked era of global social movements, in which young people often play a central role. Young generations and social movements tend to identify with a diverse set of social and political issues on both a global and local scale, while often displaying a progressive and transversal outlook. Among these youth social movements, we find Fridays For Future, a youth climate organization noted for its unique scope and tactics as well as for illustrating the prominence of environmental issues in youth activism. Since 2018, the movement has progressively grown into a network composed of many local and national groups across the world. Beyond analysis of the global character of the movement and the profile and motivations of its activists, it seems opportune to look at how—at the organizational level—these local groups evolve and position themselves. Based on a social network and a content analysis of Fridays For Future-Barcelona’s Twitter account since its creation, this article explores the organization’s “glocal” and transversal dynamics, the relationship that might exist between these two, and the potential influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on these processes. The results show that, stemming from a global preoccupation for climate change, this Youth Climate Movement organization has been increasingly oriented towards local-level networking, anchoring its activism in local struggles and realities. They also show a positively-associated process—reinforced by the COVID-19 pandemic—of increasing transversality, reflecting aspirations for global justice and the idea of an interdependency between climate change and other social, political and economic issues.

Introduction

Since the latter half of the 20th Century, there have been consolidated trends whereby social movements have been increasingly globalized and “specialized,” or single-issue oriented. From the 1960s onwards, “new” social movements started to put more emphasis on self-expression and to focus on specific causes, while the more transversal collective action of the working class was losing prominence (Tilly 2004). In parallel, concurrent processes of economic globalization and technological change have contributed to further strengthening transnational causes and identities, triggering a significant shift in social movements’ claims, strategies and alliances (Tarrow and McAdam 2005). This process has been strengthened in the waves of transnational protests since the 2010s (in which the use of digital media played an important role). Some claimed that we were entering a new era of global social movements characterized by networked citizens voicing their claims at international institutions and economic elites (della Porta and Mosca 2005; Smith and Wiest 2012; Castells 2015). During this same period, research on youth political participation identified similar trends, among which an issue-based engagement, post-materialist values (emphasis on self-expression, global justice, environmentalism, among others) as well as global identities and concerns (Cammaerts et al., 2014; Soler-i-Martí 2015). In fact, some of the most relevant transnational protests of the last decade, from the Arab spring to the last wave of climate movement, have a deep generational dimension.

However, we also find some evidence that nuance both the dynamics of globalization and specialization of social movements. On the one hand, an over-emphasis on international networks might have clouded the importance of local and national contexts in the emergence of collective action and the forms it takes (Voss and Williams 2012), contexts that are still central to the mediation of meanings and symbols (Brennan et al., 2005). Digital media not only enable (or at least facilitate) global connectedness, but they also fortify relationships and broaden networks on a more immediate local, regional, or national scale. Some talk about contemporary social movements as being increasingly “glocal,” operating both globally and locally, and with overlapping online and offline networks (Urkidi 2010).

On the other hand, while contemporary youth social movements indeed tend to be more issue-based, or single-issue oriented (Castells 1996), some scholars identify an increasingly transversal approach, as activists address an increasing diversity of issues and adopt what could be called a “cosmopolitan outlook” (Koukouzelis 2017; Sloam and Henn 2019). In line with this idea, even single-issue social movements would be adopting a more holistic view in their diagnoses and demands.

This article aims to contribute to the debate on the role of the local dimension and transversality in global issue-oriented movements. We expect that the reinforcement of local actions and connections with other local movements contribute to the incorporation of new issues into the activism of the global climate movement.

Due to its unequivocally global, issue-oriented and generational nature, the Fridays For Future movement represents an ideal case study. To identify the above-mentioned dynamics and examine their relationship in a specific local context, the paper focuses on the Fridays For Future-Barcelona local group. As done in previous research (de Moor 2020; Díaz-Pérez et al., 2021; Dupuis-Déri 2021), this article uses a local group of the global Youth Climate Movement as a case study. The context of Barcelona, a city with a rich ecosystem of social movements and mobilizations1, offers an ideal opportunity to study the interactions of the local movement with other organizations and struggles. The Fridays For Future-Barcelona local group was created in February 2019 and is now led by around 20 highly involved and educated young activists (most of them between 15 and 25 years old). As its name suggests, it is part of the global Youth Climate Movement organization “Fridays For Future”. This global strike movement was initiated in August 2018 when 15-year-old activist Greta Thunberg—now a leading and inspiring figure of the movement—started a series of strikes outside the Swedish parliament protesting inaction on climate change and the unwillingness of those in power and society in general to give this issue the urgent attention it deserves. Soon joined by others, this novel movement quickly spread globally through the hashtag #FridaysForFuture, and seemingly provided a global platform on which concerned young people from across the world could articulate their claims and organize to push for climate action. Through sustained weekly pressure on authorities via school strikes, Fridays For Future activists—in large part composed of high school and college students—have managed to give a new life to climate activism and to substantially increase the prominence of the issue of climate change in the political and media agenda.

This article looks at the evolution of Fridays For Future-Barcelona’s “glocal” and transversal nature as well as examines the relationship between these two phenomena. It does so through a content analysis of their tweets and a social network analysis of their interactions (both from the creation of their account in February 2019 until the end of the first COVID-19 lockdown in Spain in mid-June 2020).

More precisely, the article first examines the extent to which global and issue-oriented social movements are reinforcing themselves by anchoring their activism at the local level, creating links with other movements and incorporating other issues into their agenda. Second, it will try to fill a research gap by analyzing the potential relationship between the localization of global movements and the increasing transversality of their demands.

The following section will provide a brief theoretical overview of the global-local dynamics of social movements, as well as of the idea of transversality in social movements. The article will then present the data that were used and the results of the analyses, before moving on to the conclusion.

The results suggest that, arising from a global preoccupation for climate change, the youth climate movement organization Fridays For Future-Barcelona has been focused on local-level mobilizing and networking—anchoring its activism in local struggles and realities. It has increasingly adopted a transversal outlook built upon aspirations for global justice and the idea of an interdependency between climate change and other social, political and economic issues. Finally, the results suggest that this local-level networking has favored the gradual incorporation of other issues into their own discourse.

Globalization and Localization of Social Movements

Although they are not a new phenomenon, through the deepening of globalization and the expansion of information and communication technologies (ICTs), there has been—in the last decades—a significant rise in the number of transnational social movements. These are conventionally defined as social movements that are active in more than one country (della Porta et al., 2009; Smith and Wiest 2012). There can be a wide variation in the scope of these transnational movements, from those operating in a few countries to global movements present across nearly all of the world’s nations.

Increasingly, those global movements and campaigns arise from global-level influences such as climate change or economic liberalization. Global capital and structures of domination have contributed to exacerbating collective grievances across the world on a variety of issues such as human rights and global warming (Almeida and Chase-Dunn 2018).

In parallel, the advent of new information and communication technologies (ICTs) is believed to have facilitated both the proliferation of non-institutional forms of political participation (e.g., protests, petitions, boycotts, etc.) and the rise of global social movements. ICTs allow for denser ties between activists and social movement organizations across the world (Bennett and Segerberg 2012), and they drastically reduce the costs associated with alternative forms of political participation, for example by allowing for instant communication flows and by reducing the need to meet physically in order to organize and coordinate protests (Earl and Kimport 2011; Kavada, 2015). The outburst of transnational protests (e.g., Arab Spring, Occupy Movement) from the 2010s onwards convinced many observers that we were entering a new era of global social movements. In this “networked” era, digital media play a central role in linking young, well-educated protesters who feel part of global movements making claims targeted at international institutions and economic elites (della Porta and Mosca 2005; Smith and Wiest 2012; Castells 2015).

ICTs intensify connections between global structures and create structural equivalence across different parts of the world, fostering horizontal networks which play a key role in the spread of social movements, with subsequent distinctions in the local forms of collective action (Snow et al., 2004; Erikson and Occhiuto 2017). Beyond their role in facilitating global connectedness, ICTs also strengthen relationships and broaden networks within the more proximate regional or local context. In fact, social movements are believed to be increasingly “glocal,” operating both at the global and the local scale, with a strong overlap between online and offline networks (Hampton and Wellman 2001; Urkidi 2010).

As our data suggest, “techno-enthusiasm” surrounding the ability of ICTs to create global synergies and a global public sphere should not cloud the importance of local and national contexts in the emergence and forms of collective action. Scholars studying transnational social movements have in the past been criticized for over-emphasizing international networks and for neglecting the role of the local or national context in which social movement organizations are created and operate (Gordon 1984; Voss and Williams 2012), a context that is believed to mediate the conditions for global collective action (Silva 2013). Yet, it seems that localization and local-level organizing and networking are key components of contemporary youth social movements.

The shifting balance of power across the state, the economy and civil society, and democratic institutions’ loss of control over a growing number of policy issues and processes (Strange 1996; Burnham 2001; Crouch 2004) have been particularly evident since the 2008 financial crisis (Miró 2021). These might be contributing to gradual changes in citizen engagement and in the strategies and practices of contemporary social movements (Fawcett et al., 2017). Indeed, as activists grasp the increasing power of the economy in relation to the state—whose capacity to grant concessions is fading—they are building new alternatives for civic engagement within their more direct local context, even when driven by global causes and concerns (e.g., financial crisis or global warming). These are increasingly aimed at engaging civil society instead of opposing the state, which they realize is increasingly unlikely to lead to meaningful change (Williams 2008; Voss and Williams 2012). Faced with a growing dissatisfaction with the functioning of democracy and a loss of confidence in institutions, social movements are developing new democratic practices at the local level, both from theory and from practice, building new spaces of social trust and politics from below (Della Porta 2012). It could be said that globalization shaped social movement dynamics in several ways, on the one hand by linking global structures, and on the other hand, by making civil society the most realistic arena for building alternatives and challenging the status quo.

Local struggles and localization remain the base for social movements and for the mediation of meaning and symbols (Groenewald 2000; Brennan et al., 2005). Contemporary social movements are increasingly built around global and common causes, but are autonomous and place-based, engaging civil society at local and regional levels. In this article, we expect these local interactions to contribute to a progressive increase in the transversality of social movements, partly through the gradual realization of the connections that exist between different struggles.

Towards a Transversal Activism?

The advent of a post-industrial society is believed to have led to important changes in terms of political participation. These are often described as a shift from a class-based ideology and a focus on material wellbeing to the rise of non-institutional and issue-based forms of engagement with a focus on post-material issues like human rights or the environment (Inglehart 1997; Cammaerts et al., 2016).

It seems that contemporary social movements like the Youth Climate Movement are indeed taking position on post-material issues in their activism (although not exclusively as they also address issues like access to housing or healthcare). Yet, instead of showing signs of an end of ideology (cf., Bell 1965), or being strictly issue-based—or single-issue oriented (Castells 1996)—they are increasingly embracing a transversal, or “cosmopolitan” outlook (Sloam and Henn 2019), considered as an ideology and a learning process (Koukouzelis 2017).

The idea of cosmopolitanism is complex, multifaceted and goes beyond transversality (Gizatova et al., 2017). Here, it is understood as a principle of mutual respect and equal moral worth of all human beings, regardless of ethnicity, nation, beliefs, gender, or socioeconomic position (Ypi 2012).

In the case of the Youth Climate Movement, cosmopolitanism could be seen as a response to the “globalization of domination” (Gills 2005), related to the idea that those who have benefited the least from extractivism and economic growth will suffer their consequences the most, in the form of infectious diseases, conflict over natural resources, droughts and forced migration, among others (Brock 2012). Cosmopolitanism, in this case, proposes a normative vision of global justice as a solution to the climate crisis, distanced from international treaties and state negotiations. While the notion of justice was traditionally confined to the politics of nation states, the idea of global justice is central to cosmopolitanism and its rejection of the statist logic of state legitimacy (Koukouzelis 2017). Cosmopolitanism ought not be seen as a fixed principle, but rather as a learning process through social change and connectivity between individuals, groups and society. It has an essential cognitive dimension which, via social processes of contestation and de-contestation of normative ideas, might unify diverse claims under an overarching “value umbrella.” This learning process evolves through the realization of new connections between issues that were previously seen as isolated. The ability to see these previously unknown connections represents the foundation for the possibility of global and environmental justice (Delanty 2014). Based on the ideas of global justice and environmental justice, grassroots climate movements have gone even further in the transversality of the concept by adopting the notion of “climate justice” (Chatterton et al., 2013). The latter emphasizes, on the one hand, the connection between the global nature of climate change and its effects on local communities and, on the other, the binding link between “principles of social justice, democratic accountability and participation, and ecological sustainability” (Schlosberg and Collins 2014: 370). Looking at climate activism globally, there seems to be an increasing recognition of the need to adopt a more holistic approach to fighting climate change and reducing carbon emissions. An approach that acknowledges interdependence, that includes everyone and that—as a precondition for solving the climate crisis—addresses the underlying imbalances that have fueled the problem in the first place. These include capitalism, racism, patriarchy, or inequalities (Koukouzelis 2017; Johnson and Wilkinson 2020).

In line with their transversal outlook and this apparent unification of issues and values, research suggests that contemporary youth are more politically and culturally tolerant, and more supportive of social justice than older cohorts (Dalton 2015; Sloam and Henn 2019).

The progressive realization of interdependence (both issues and individuals), shared values, and common positions on a diversity of issues like the environment or gender equality, but also access to housing or healthcare, might lay the ground for the unification of young activists as a coherent political unit striving for global justice and the transformation of capitalist social relations and structures of domination (Hosseini et al., 2017).

The recognition of the need to adopt a more holistic approach and the realization of the connections that exist between different issues could also mark the downfall of single-issue campaigning. The latter, by not accounting for this transversality and intersectionality, might adopt a restrictive focus that merely addresses the “visible part of the iceberg.”

Focusing on the animal rights debate, the following quote is a telling illustration of the above claim: “Instead of merely changing the conditions under which animals are exploited, sometimes we can end their exploitation” (Regan 2004, 196).

Going beyond the study of the “glocal” or transversal nature of social movements, this article attempts to fill a research gap by looking at the relationship between localization and transversality, using Fridays For Future-Barcelona as a case study. It draws from the assumption that closer links with other local movements might contribute to an increase in transversality, as activists realize—and act upon—the connections that exist between different issues. On top of this, we will take into account the role of the COVID-19 pandemic and the subsequent lockdown, which likely had—and is still having—a significant impact on activists and social movement organizations worldwide (Pressman and Choi-Fitzpatrick 2020; Thompson 2020).

In doing so, this study relies on Twitter data, in the form of a content and a social network analysis, as will be developed in the next section.

Data and Methods

This article is based on data collected from the social media platform Twitter, which remains a very popular and accessible source of data for social science research, often praised for its political value and relevance (Tumasjan et al., 2010; Jungherr 2016). The movement uses other social networks such as Instagram or Facebook, but Twitter is where they post most frequently, better capturing their day-to-day activity, positioning and interactions. Social media data—or digital trace data—allow for observations of online social behavior in its natural setting, behaviors that are not solicited nor potentially influenced by the researcher. Although not devoid of weaknesses (e.g., lack of depth and of individual-level insights), digital trace data provide the researcher with a window into large-scale processes and behaviors, where more traditional survey or ethnographic data might introduce biases, such as those associated with social desirability or a lack of accuracy of retrospective self-reports (Fisher 1993; Stodel 2015). The analysis of the content that the movement publishes on social media is also a very insightful source for analyzing its discourse (Polletta and Gardner, 2015). Social media posts leave a trail of the messages, topics, orientations, and relationships with other actors with whom the movement presents itself publicly.

Taking Fridays For Future-Barcelona as a case study, this article relies on two sets of data that help us improve our understanding of contemporary youth political participation and the Youth Climate Movement. The timeline for both data sets runs from February 2019 (when the organization and Twitter account were created) to mid-June 2020 (corresponding to the end of the first COVID-19 lockdown in Spain). This time period not only allowed us to observe the organization’s evolution from the start, identifying dynamics of localization and increasing transversality, but also to examine the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic and the confinement measures on these identified dynamics.

The first analysis of this article is a social network analysis (SNA), while the second is a content analysis.

Social Network Analysis (SNA) is used to examine patterns in relations between interacting units, focusing on network structures in terms of nodes (i.e., Twitter users) and ties or edges (i.e., the interactions or relationships between these nodes) (Prell, 2011; Scott and Carrington, 2011). They are particularly useful in identifying trends in network dynamics, giving information on the positioning and activity of different actors and organizations.

The social network map presented in the analysis below corresponds to the whole @f4f_barcelona Twitter user-network between February 2019 and June 2020. It is based on all the tweets that appeared in the @f4f_barcelona timeline, including their own tweets but also retweets and mentions (including to other accounts via retweets of @f4f_barcelona). The size of the circles corresponds to the in-degree of the accounts (the attention that specific accounts receive in the network—larger circles received more mentions and retweets than smaller ones). The social network map was created through Gephi using the ForceAtlas2 layout algorithm for the network spatialization (Jacomy et al., 2014). The scope (local, regional, national, international) of the accounts were hand-coded by a single coder. When there was doubt, or when no information was available, the accounts were coded as “N/A” (not available).

We carried out a content analysis of all of Fridays For Future-Barcelona’s Twitter posts (tweets) from February 2019 until June 2020. The Twitter data were collected from Fridays For Future-Barcelona’s official Twitter account using the Twlets platform. We then sampled all the tweets present in the network to only focus on @f4f_barcelona’s original tweets. These were posted by members of the local group’s communication commission. Each of the 724 tweets were hand-coded by a single coder using a codebook that helped us to classify their content. The codebook was developed using a bottom-up approach, identifying relevant variables as part of the data collection process. We used 33 variables of interest that included information about the date of the post, the full text of the tweet, interaction information, multimedia use, main purpose of the tweet, references to climate change or other social issues, the use of future, generational or emergency speech, references to different actors and their scope, or references to the media, among others. For the purpose of this content analysis, we specifically relied on variables related to mentions and references to different types of actors as well as to the different issues that were addressed in the tweets (see Appendix Table A1 and Appendix Figure A1 for more details). Based on the full text of the tweets, we also performed an analysis of the evolution of the occurrence of specific keywords.

Results

In this section, we will present the results of the analyzes, starting first with the “glocal” nature of the movement, looking at the scope of their interactions through the social network analysis and examining the evolution in the scope of the movements that they mention and make references to. Second, we will move on to the analysis of the movement’s transversality, looking at the evolution of their mentions or references to different issues. Finally, we will look at the relationship between localization and transversality, exploring how interactions with local-level movements and organizations might contribute to the incorporation of other issues into their discourse.

“Glocal” Nature and Localization

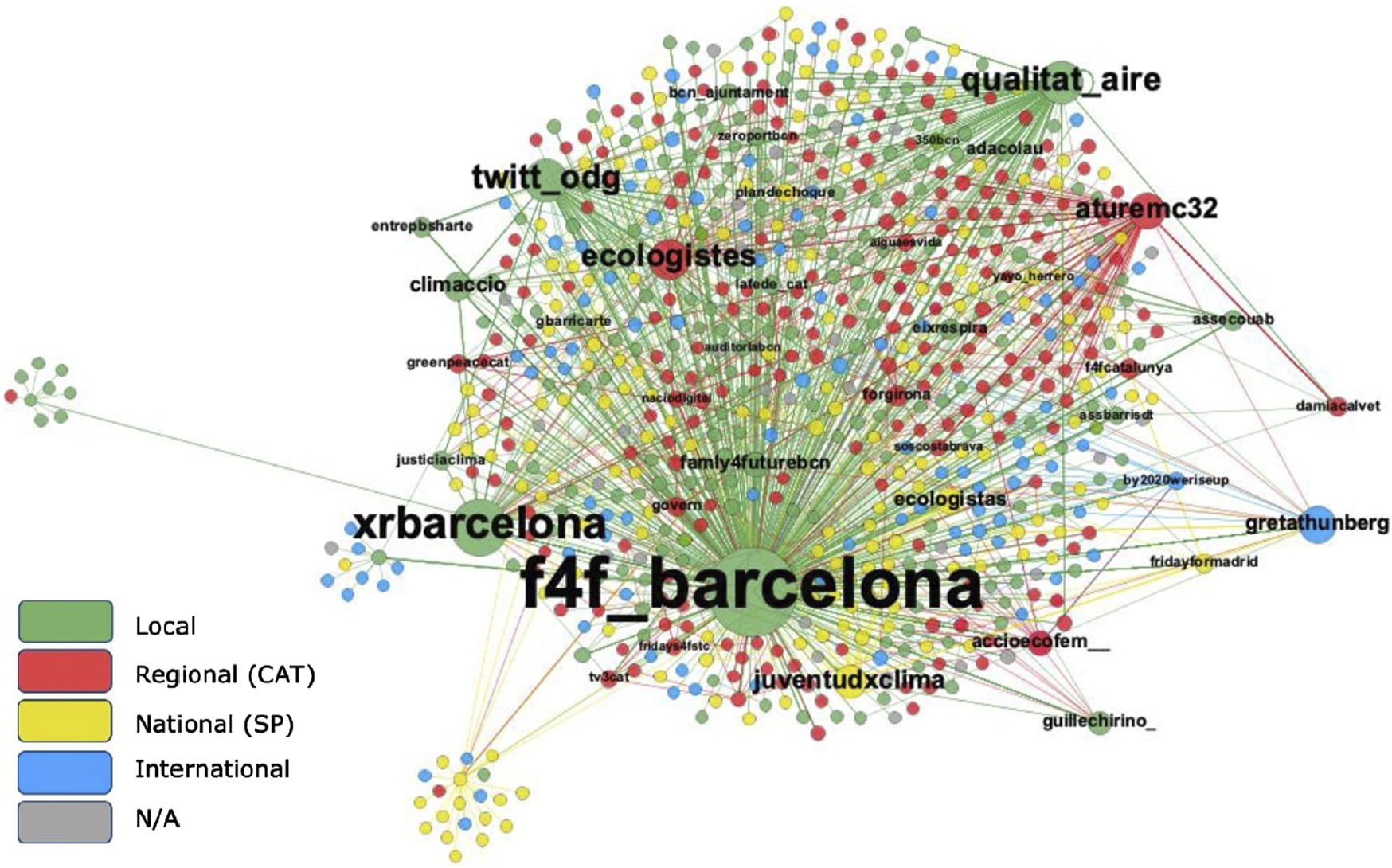

Looking at the whole study period, the social network map below (Figure 1) shows the scope of the different Twitter accounts with which Fridays For Future-Barcelona (@f4f_barcelona) interact (mentions and retweets). As mentioned above, the size of the circles corresponds to the in-degree of the accounts (the attention that specific accounts receive in the network).

FIGURE 1

Scope of the Twitter accounts with which @f4f_barcelona interact (based on mentions and retweets).

The map shows the significant centrality of local- and regional-level civil society actors in the Twitter interactions of the @f4f_barcelona network.

Looking at the map, we see that although national and international accounts are present across the network, interactions with these accounts are less intense compared to interactions with local- and regional-level accounts.

We see that a majority of the edges come from and go to local- and regional-level accounts, and that the accounts with the highest in-degree are almost exclusively local and regional.

As could be expected, Greta Thunberg also has a relatively high in-degree, being the leading figure of the movement and receiving regular mentions and retweets from some of the accounts in the network. However, she does not appear central as she does not actively take part in the network (she has a low out-degree centrality in the network, meaning she does not initiate many—if any—edges).

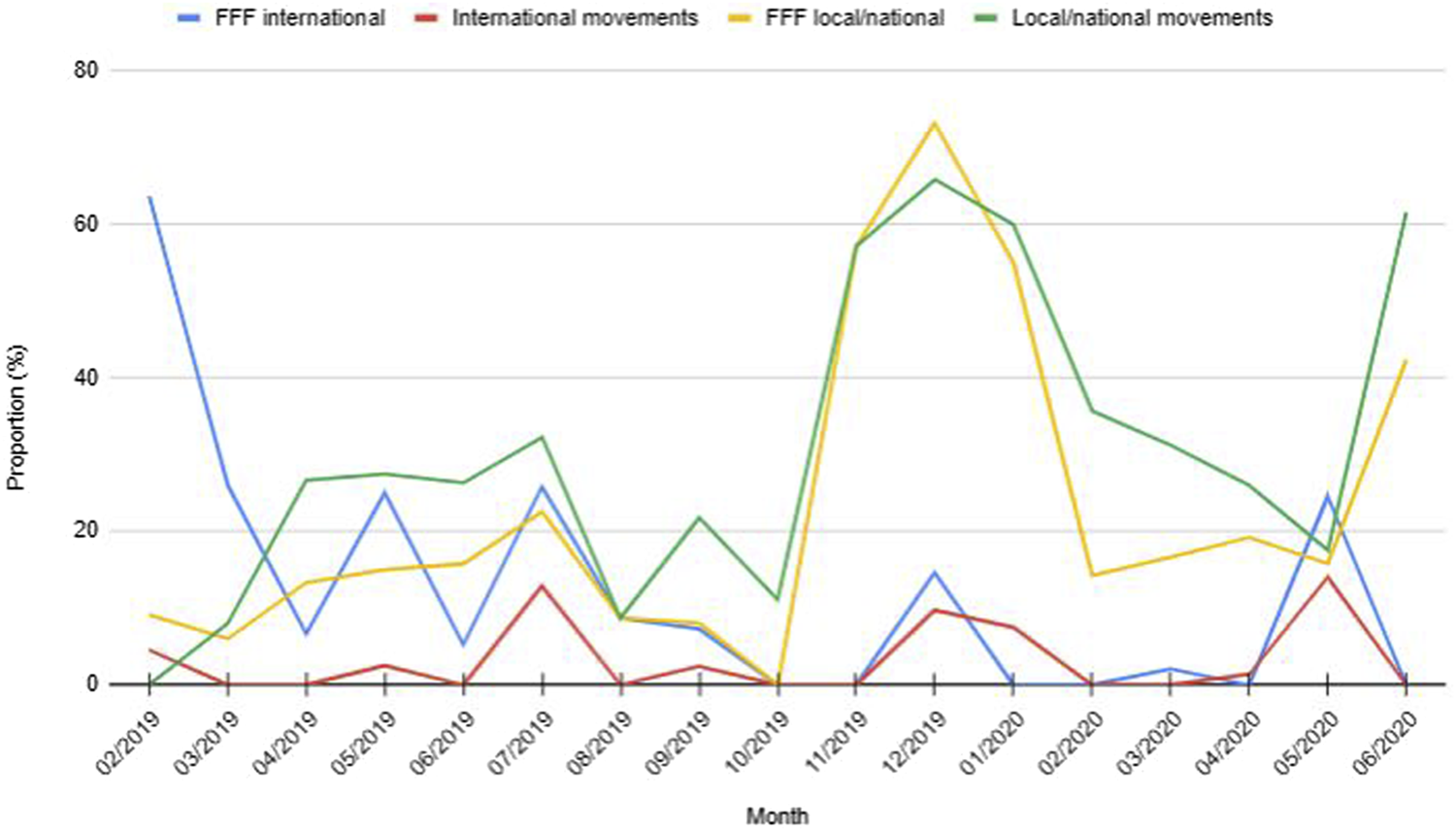

This map suggests that, despite the potential of digital media to reach millions of people from across the world and to tap on and cultivate the scale and global dimension of the movement, their use of Twitter is primarily kept within the more proximate local and regional realm, and in many cases reflects connections that exist offline (e.g., joint actions with @xrbarcelona or @qualitat_aire). It is worth mentioning here that 93% of their tweets were written in Catalan. Only 1% of their tweets were written in English, all of which were posted in the first few months after the local group’s creation (i.e., before June 2019), suggesting an initial intention to engage at the international level. In line with this, Figure 2 below shows the evolution of the proportion of tweets that mention or make reference to different international and local/national movements. The blue and red lines correspond—respectively—to Fridays For Future groups or other movements that are based outside of Spain, whether in Europe or elsewhere. The yellow and green lines correspond—respectively—to Fridays For Future groups or other movements that are based either in Barcelona, in Catalonia, or in other parts of Spain.

FIGURE 2

Monthly proportion of tweets mentioning or making reference to international and local/national movements.

Looking at Figure 2, we notice an initially high intensity of references to and interactions with Fridays For Future groups at the international level. This relation with the global movement is notable during the first weeks following the formation of the local group in Barcelona, but then quickly decreases. Alongside this, in this same early period there seems to be a general increase in the proportion of tweets that mention or make reference to Fridays For Future groups, and in particular other movements, at local and national levels. It is likely that the peak in local/national-level interactions and references in and around December 2019 is partly attributable to the COP25 which took place in Madrid during the first half of this month. There were mobilization efforts among different movements based in Spain, and the organization and coordination of joint actions around the climate conference. Yet, the proportion of tweets in which Fridays For Future-Barcelona refer to and interact with local/national-level movements remains relatively high during the following months, with a new marked increase in June 2020. It should be mentioned here that in the specific case of Catalonia and Barcelona, high levels of mobilization around the independence movement—particularly related to the sentence of separatist leaders in October 2019—might have favored a higher intensity of interactions with local and regional movements. Similarly, the COVID-19 outbreak and the subsequent lockdown are also likely to have contributed to strengthening the links between this youth climate organization and other local movements dealing with other—and often related—issues associated with the pandemic (e.g., access to healthcare, public services, inequalities).

Transversality

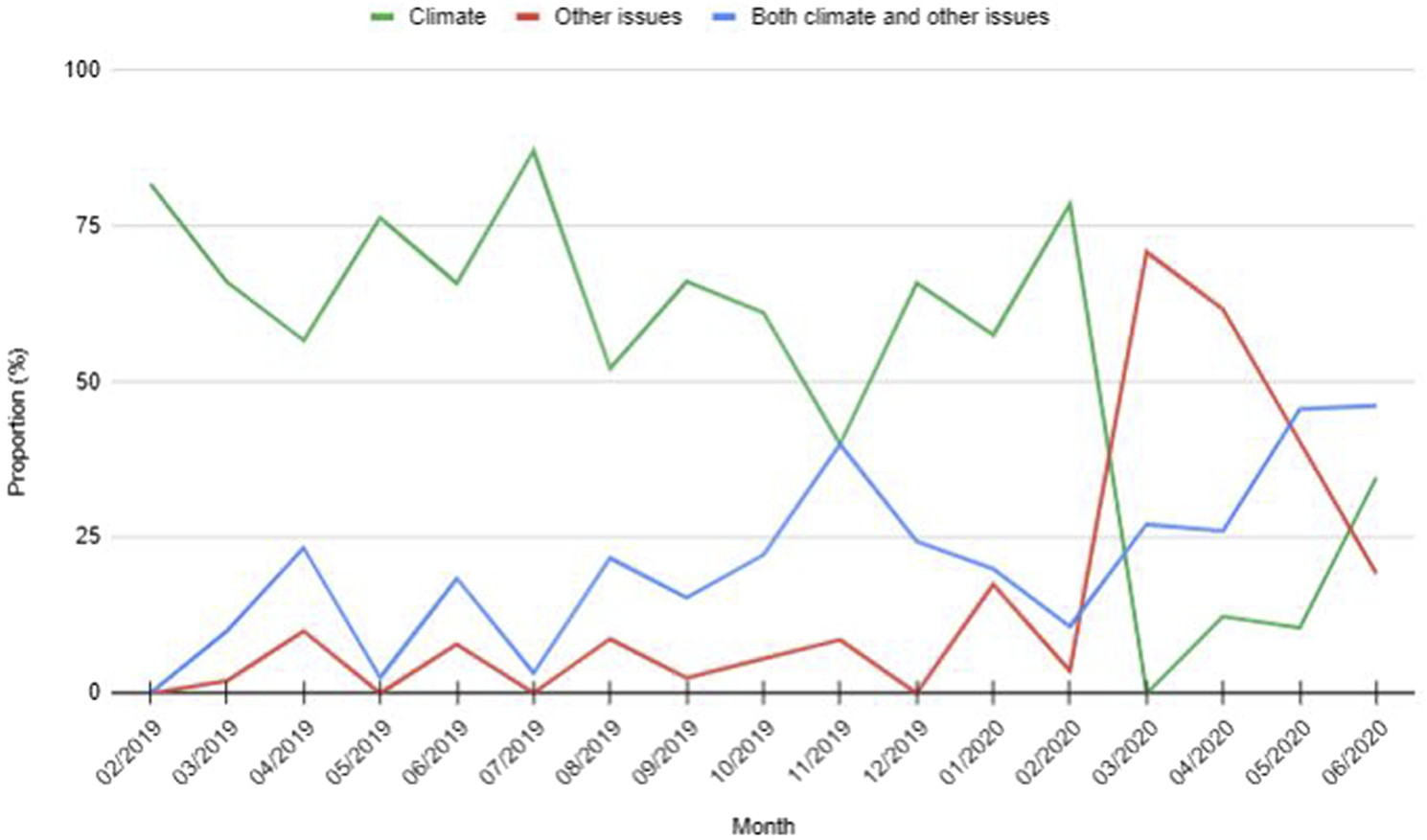

As illustrated in Figure 3 below, the content analysis of the tweets suggests a gradual increase in the incorporation of issues other than climate change or the environment into the activism of Fridays For Future-Barcelona.

FIGURE 3

Monthly proportion of tweets making reference to the climate vs. other issues.

The above graph illustrates the monthly proportion of tweets that make reference to climate change or the environment, other issues, or a combination of both. It shows a general decrease in the proportion of tweets that exclusively make reference to climate change or the environment, and an increase in the proportion of tweets that exclusively make reference to issues other than climate change or the environment. These upward and downward trends were particularly pronounced at the beginning of the COVID-19 lockdown in March 2020, when (climate) protests were no longer an option and when a significant amount of attention was given to issues of access to healthcare, the visibility of health workers, or social inequalities. This sudden shift can be explained—at least partly—by the disruptive nature of the pandemic and the subsequent measures adopted by governments worldwide, all of which significantly altered the spectrum of possibilities and future perspectives. It can also reflect an adaptation strategy by Fridays For Future-Barcelona who were willing to keep the movement alive on social media and to emphasize the interdependency of the climate crisis and other issues. However, despite all of this, the graph shows a steady increase in the proportion of tweets that refer to both climate or the environment and other issues, whether social, political, or economic. Reflecting back on the idea of cosmopolitanism as a learning process, this suggests the gradual diversification of their issue focus, along with the gradual realization of the connections that exist between the climate crisis and other social, political, and economic issues. It could in fact be that the COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated a process of increasing transversality that was already under way.

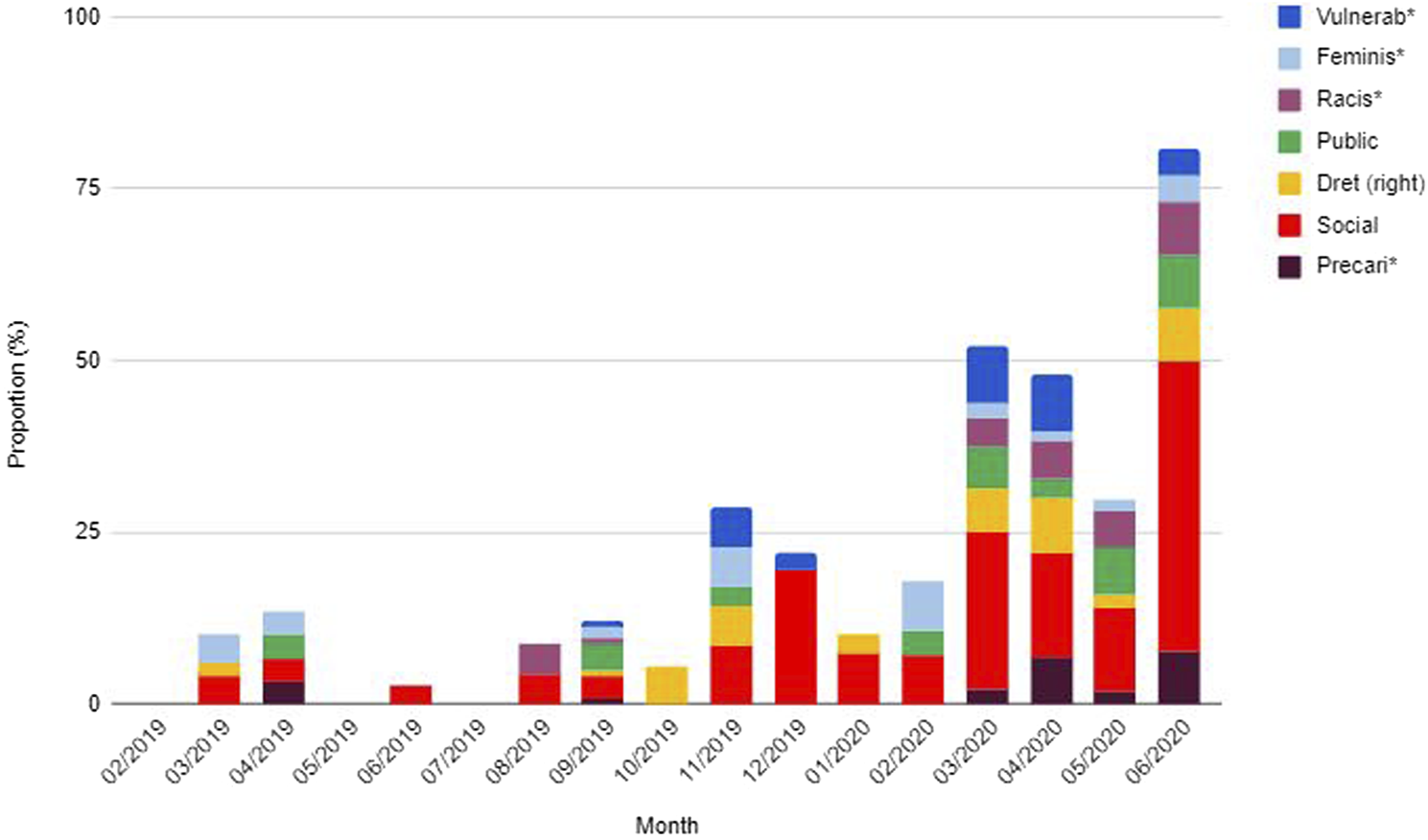

In line with the above, a look at the evolution of the occurrence of specific keywords relevant to social issues in their tweets (see Figure 4 below2) suggests the same trend, seemingly accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic and the subsequent lockdown.

FIGURE 4

Monthly proportion of tweets including selected keywords relevant to social issues.

The graph shows the monthly proportion of tweets that contain selected keywords relevant to social, political, and economic issues, whether of a material nature or not. Once again, it suggests an increase in transversality and in the inclusion of other issues into their Twitter discourse. For instance, we see an important increase in the proportion of tweets that include the keyword “social,” oscillating between 0 and 4% during most of 2019, and rising to 20% in December 2019 and 42% in June 2020. This increase might have gone hand in hand with the gradual realization of the connections that exist between global warming and social justice. The notion of ‘climate justice’ is key in emphasizing this link, as illustrated in Figure 5 and Figure 6 below.

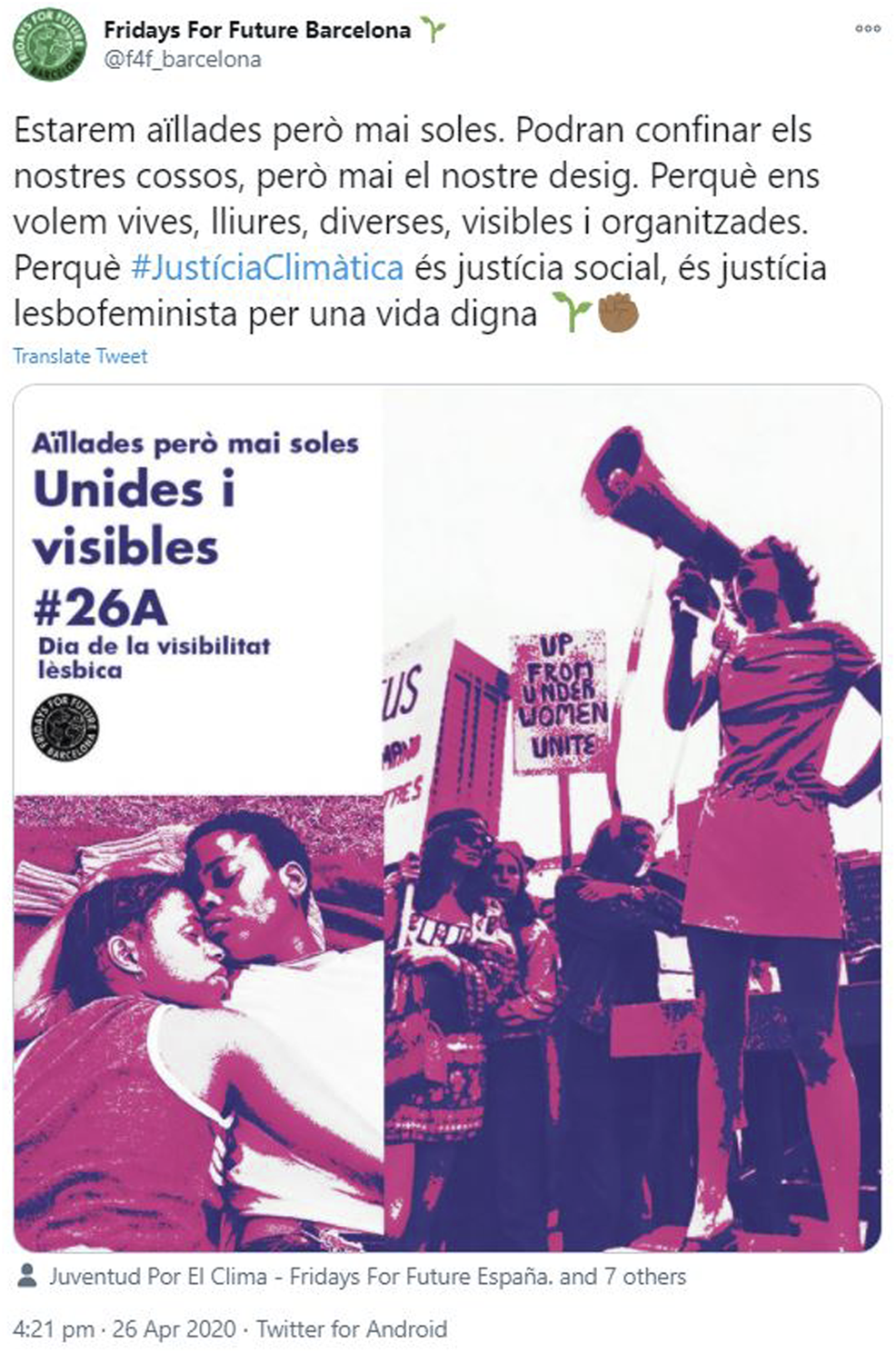

FIGURE 5

Example of a tweet highlighting the connection between climate justice, social justice and gender justice (or “lesbofeminist justice”).

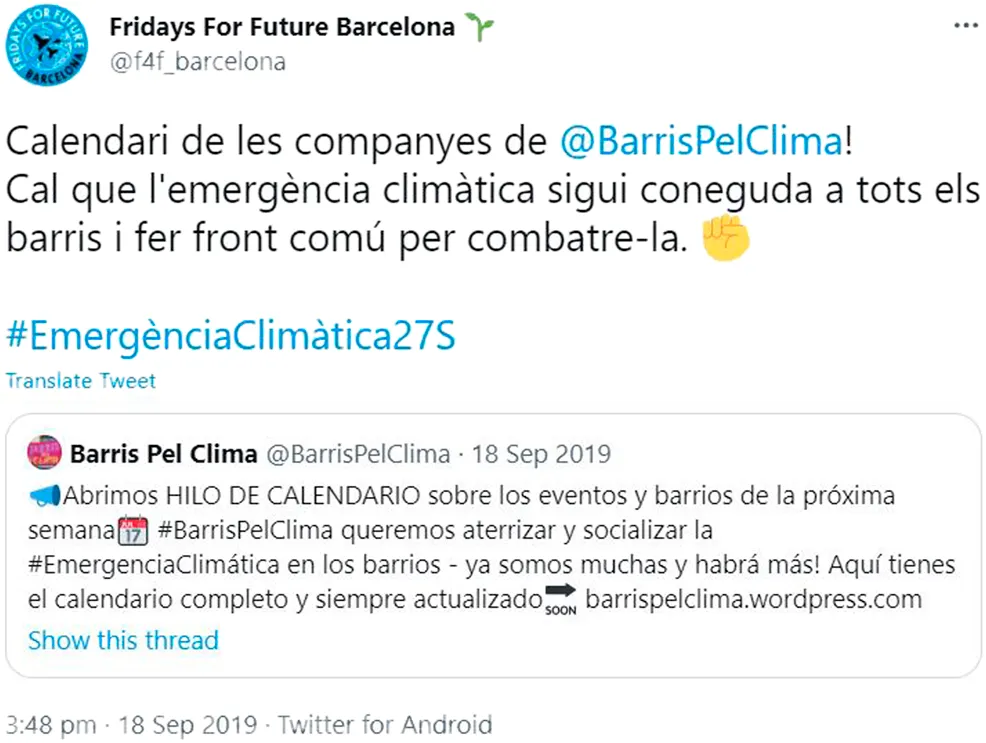

FIGURE 6

Example of a tweet presenting climate justice as an intersectional and transversal environmental outlook.

Text translation: We will be isolated but never alone. They can confine our bodies, but never our desire. Because we want us alive, free, diverse, visible and organized. Because #ClimateJustice is social justice, it is lesbofeminist justice for a decent life.

Text translation: When we talk about #ClimateJustice we are talking about an intersectional and transversal environmental outlook, that focuses on the effects, consequences and realities that occur in all bodies, territories and lives.

The apparent increase in transversality from March 2020 onwards can certainly be attributed—at least to some extent—to the COVID-19 pandemic and its social and economic consequences, as well as to the need to adapt their tactics and communication strategy to a new and changing context. However, as mentioned previously, the results suggest the acceleration of a diversification process that was already under way and that is likely to continue going into the future.

On the Relationship Between Localization and Transversality

In the results analyzed so far, it is clear that Fridays for Future-Barcelona—despite being part of a global movement—have established a close relationship with other movements and organizations at a local, regional, and national level. In parallel, we saw that they are gradually incorporating other social issues into their discourse, beyond climate change and the environment. In this section, we will look at whether there might be a relationship between these two phenomena.

The codification of the tweets allows one to see how different aspects of the posts are related. In our case, we are particularly interested in analyzing how interactions and proximity with other local/national movements and organizations might foster the incorporation of other issues into the organization’s discourse. To do this, we performed a logistic regression analysis (presented in Table 1) using the presence of other social issues in their discourse as a dependent variable.

TABLE 1

| B | (se) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 342,980 | — | (189,293) | |

| Period | Date | 0.000 | * | (0.000) |

| Lockdown | 0.872 | * | (0.393) | |

| Reference to COVID-19 | 1,058 | ** | (0.355) | |

| Purpose of the post | Call for action | −0.654 | ** | (0.244) |

| Coverage of actions | −0.492 | — | (0.264) | |

| Dissemination of internal activities | −1,282 | *** | (0.302) | |

| Media coverage | −0.257 | — | (0.325) | |

| Objectives reached | −0.896 | — | (0.626) | |

| FFF speech | Emergency speech | −0.687 | ** | (0.226) |

| Generational speech | −0.828 | — | (0.485) | |

| References to the future | 0.009 | — | (0.260) | |

| Mentions and references to other organizations and social movements | FFF international | −0.386 | — | (0.391) |

| FFF local | −0.729 | * | (0.298) | |

| International org. or movements | 1,057 | — | (0.539) | |

| Local or national org. or movements | 1,027 | *** | (0.271) | |

| N | — | 726 | — | — |

| Nagelkerke R2 | — | 0,417 | — | — |

Logistic regression model of posting on other social issues.

*sig < 0.05

**sig < 0.01

***sig < 0.001

Independent variables include time-related variables, such as the date and the lockdown period, the exceptionality of which might have a particular effect. In this sense, a variable that accounts for the posts that directly mention COVID-19 was included. The model also includes variables related to the purpose of the post (whether it is aimed at calling for action, covering actions, disseminating internal activities, media coverage, or highlighting objectives reached). We also included variables related to the type of discourse that is salient in the post. In particular, they refer to the discursive resources of the global movement such as the idea of emergency, the appeal to younger generations and perceptions of the future. Finally, there are four variables corresponding to different types of actors that the posts mention or refer to: Fridays For Future international; other local groups of Fridays For Future in Spain; other international movements or organizations; and other local or national movements or organizations. All the variables are dummies, except the date which is a continuous variable.

In line with the previous results, the model shows that as time passes, the probability that Fridays For Future-Barcelona’s posts incorporate other social issues increases, a trend that is reinforced in the lockdown period. The fact of dealing with a topic related to COVID-19 also favors the incorporation of other social issues into the message. This reflects the organization’s support to campaigns calling for social measures to address the economic and social impact of the pandemic. Variables related to the purpose of the posts reveal how posts aimed at convening to and disseminating external (call for actions) or internal (dissemination of internal events) activities negatively affect the likelihood that the post will address social issues. These results might point to the idea that, despite the incorporation of other issues into the organization’s discourse, its actions are still fundamentally climate-oriented, and so are their calls for action on social media. The results of the variables on the discursive resources of the movement suggest that the idea of emergency is used primarily to refer to the climate. In fact, the idea of emergency in the climate movement has tended to replace the concept of climate change to stress the need to take immediate action. Finally, the variables that analyze mentions and references to other organizations or movements suggest that posts that mention or refer to other local groups of Fridays For Future (within Spain) negatively affect the likelihood that the post will address other social issues. On the other hand, posts that mention or refer to other local/national organizations or movements significantly and positively affect the likelihood that the post will address other social issues.

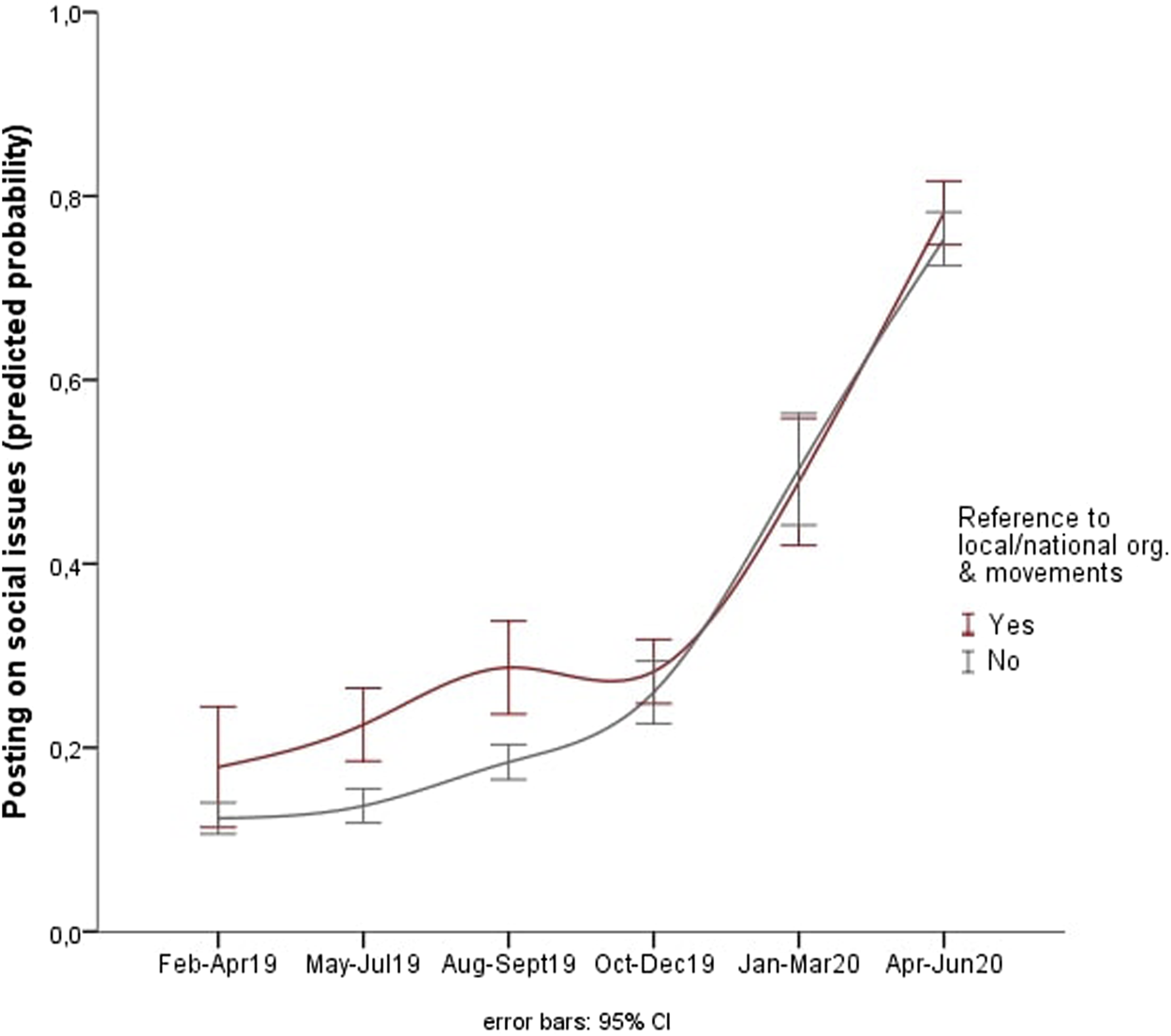

The latter is particularly relevant for the purpose of this article. In trying to refine our interpretation of the effect of mentions and references to local/national organizations or movements on the likelihood of the post addressing other social issues, Figure 7 below presents the predicted probabilities extracted from the model. The figure also includes the time variable as we are interested in understanding how—over our analytical timeframe—proximity and interactions with local and regional movements have affected their transversality and the incorporation of other issues into their discourse.

FIGURE 7

Predicted probability of posting on other social issues by time period and reference to local/national organizations and movements.

A first result shown in the above graph is that, controlling for the other variables, the probability that Fridays for Future-Barcelona’s posts incorporate other social issues beyond climate has increased significantly over the period of analysis. It seems clear, then, that the hypothesis of increasing transversality is confirmed by the data. These results also highlight how posts that mention or refer to other local/national organizations or movements positively affect the likelihood of addressing social issues. In any case, when incorporating the time variable, we observe that this effect occurs mainly in the first half of the analyzed time period. From February to September 2019, the likelihood of incorporating other social issues into their tweets clearly increases when mentioning or referring to other local/national organizations or movements. In contrast, in the second half of the time period, where the probability of transversal discourse increases even more, the effect of mentions or references to other local/national organizations or movements virtually disappears.

These results suggest that, in an initial phase during which the discourse of Fridays For Future-Barcelona was probably still in the process of formation, proximity and interactions with other local/national organizations and movements (facilitated by online social networks) might have influenced and contributed to the incorporation of other issues into their discourse. Subsequently, this transversal discourse seems to become integrated as their own. At this point, the probability of treating social issues further increases, while the effect of mentioning or referring to other local/national organizations or movements disappears. It seems that this transversality is then no longer linked with their interactions with other local/national organizations or movements but becomes an integral part of their discourse and identity.

Discussion and Conclusion

In this article, we were interested in analyzing global movements’ “glocal” and transversal dynamics, the relationship between these two, and the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Based on a case study of Fridays For Future-Barcelona, looking at their Twitter discourse and interactions, this article has contributed to shedding light on their local orientation, their increasing transversality, and on the apparent relationship between these two tendencies. Additionally, our findings suggest a significant influence of the COVID-19 pandemic and the confinement measures on the activism of this local group of Fridays For Future.

The advent of ICTs and the deepening of globalization have contributed to the rise of global social movements. Digital media are believed to play a central role in linking young, well-educated activists protesting before international institutions and economic elites (della Porta and Mosca 2005; Smith and Wiest 2012; Castells 2015). Yet, beyond their role in intensifying connections between global structures and shared grievances, our case study shows that Fridays For Future-Barcelona are making a use of social media (more particularly Twitter) that is more oriented towards strengthening networks and connections within their more immediate local and regional context, with an apparent overlap between online and offline networks. As our results suggest, they mostly concentrate their efforts at engaging civil society at local and regional levels, with few signs of extensive transnational organizing and networking. Although Fridays For Future can be considered as an archetype of global movements, built around global concerns and grievances, with a shared global identity and a coordinated action strategy, the local groups—and specifically Fridays For Future-Barcelona—are autonomous and place-based. This supports not only the idea of the local level as being central in social movement dynamics (Groenewald 2000; Brennan et al., 2005), but also of local civil society and awareness-raising as representing the most realistic and promising repertoire of contention in their fight for climate and global justice.

A likely related process identified in this article is one of increasing transversality. Although Fridays For Future-Barcelona started as a climate-centered organization, they swiftly and increasingly incorporated other social, political and economic issues into their discourse.

The advent of a post-industrial society is believed to have contributed to the emergence of non-institutional and issue-based political participation based on post-material values like human rights or the environment (Inglehart 1997; Cammaerts et al., 2016). Our results not only confirm claims of contemporary social movements as having a post-material orientation, but they also—and perhaps more importantly—suggest that they might be gradually unifying their struggles—built upon aspirations for global justice—under an overarching “value umbrella.” Some studies have shown the persistence of the individual effect of post-materialist values in times of austerity (Nový et al., 2017; Henn et al., 2018), but it also seems that, in line with our results, social movements with a strong generational component are returning to materialist issues. The notion of cosmopolitanism can help in refining the direction of generational value change by focusing on normative and moral questions of rights and equality. Beyond contemporary activism as having a post-materialist orientation, our results seem more in line with the concept of cosmopolitanism as a moral principle of equal worth of all human beings (Ypi 2012). It might be that instead of emphasizing the material or post-material orientation of different political claims, one ought to consider the centrality of progressivist notions of equal worth and rights, regardless of whether the issue is of a material nature or not. Fridays For Future-Barcelona focus on both material (e.g., access to public services) and post-material (e.g., global warming or freedom of speech) issues, but it seems that the common thread across their activism is the principle of equal worth of all human beings, regardless of nationality, ethnicity, sexual orientation or socio-economic background.

Our results in this article seem to reflect the idea of cosmopolitanism as a learning process through the gradual realization of the connections that exist between different struggles. In an attempt to fill a gap in the scientific literature, this study has contributed to the empirical examination of the relationship between localization and transversality in social movements. We have highlighted the potential effect that close connections with other local movements might have on transversality—or the incorporation of other issues into their own discourse. This effect seemed most important in the first phase after the movement’s creation, after which this transversality seemingly became integrated into their own discourse. While it would be wise to confirm this effect in other contexts and with other movements, it is likely that these local connections fuel a politicization process, opening a window into a diverse set of social, political and economic issues previously seen as unrelated. The Fridays For Future movement has been particularly attractive among young people, many of whom did not have any prior militant experience (Wahlström et al., 2019; de Moor et al., 2020). Following the impressionable years hypothesis, young people are in a period of life that is particularly favorable to the incorporation of political orientations and values which are likely to remain stable later on (Alwin, 1994; Prior, 2010). Thus, from the point of view of individual politicization, it can be expected that a movement formed by young people, at the age of forming their repertoire of political orientations, is likely more prone to the incorporation of new causes and values. But politicization also occurs at the movement level. Cities are fertile grounds for social and political mobilization, precisely because they are spaces characterized by interactions between social phenomena, people and groups, thereby furthering their interconnection (Miller and Nicholls, 2013). The fight for a specific cause facilitates interactions with other movements that—while not sharing the same cause—share a certain framework for social change. That is why identification with one’s own group can lead to a politicized collective identity (Simon and Klandermans, 2001). Thus, Fridays For Future-Barcelona’s links with other local movements and actors could contribute to a more politicized reading of social reality and, consequently, to the incorporation of other issues into their social media discourse.

These local connections and subsequent politicization process might—in the case of local groups of Fridays For Future—favor exits from the “bubble” of global climate activism, going beyond a strictly issue-based participation to provide perspective and a broader vision of the issue at stake. This apparent tendency of increasing transversality might point to the possibility of building common ground for constructive dialogue and collective learning, as well as active and meaningful political cooperation among different collectives and identities. In this sense, looking at the last decade’s mobilizations with a youth component and often highlighting a generational conflict—from the Arab Spring and the Occupy Movement or the Indignados in Spain or Greece to the recent protests in Hong Kong or Chile—we see that they all have in common the will to challenge the whole political, economic and social system, despite being rooted in particular local or national struggles. The case of Fridays For Future-Barcelona also shows how—at a time when Norberto Bobbio (1984) “unfulfilled promises of democracy” are more visible than ever—youth social movements are increasingly aware of the close connections that exist between different causes.

Considering the article’s findings, one ought to bear in mind, first, that this is a case study of Fridays For Future-Barcelona and that more research is needed to be able to generalize the findings to other social movements and organizations. Secondly, we should stress the significant impact that the COVID-19 pandemic had on activism and social movements worldwide. The disruptive nature of the pandemic and the subsequent restrictions altered the spectrum of possibilities and brought significant uncertainty. The prominence of social issues related to the economic and social impacts of the pandemic (particularly acute among young people) is likely to have prompted an adaptation strategy by Fridays For Future-Barcelona, willing to keep the movement alive on social media and to stress the connections between the climate crisis and other social issues. This has certainly been influential, most probably by accelerating the process of increasing transversality identified in this article. The COVID-19 pandemic is—like climate change—a global issue with important local consequences. It has further highlighted our global interdependence and the need for strong local networks and solidarity in the face of adversity. It is also a multifaceted and transversal crisis, questioning our relationship with the natural world, challenging our health capacities and testing our resilience across all sectors of the economy.

Looking forward, it can be expected that the processes identified in this research will be further reinforced in a post-COVID context, which will likely be characterized by significant social and economic hardship and a continued questioning of our political and economic systems.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without reservation.

Author contributions

LT and RS-i-M have collaborated in designing and conducting this study. LT has taken a leading role in developing the article and has also codified the content of the tweets. RS-i-M has developed the multivariate statistical analysis and contributed to the theoretical framework and the discussion.

Funding

This article is based on data from two research projects on the Fridays For Future movement: YouGECA (Youth Global Engagement for Climate Action) funded by the PlanetaryWellbeing2019 UPF programme, and #4F (Hashtags For Future) funded by the AJOVE2019-AGAUR.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Mariona Ferrer-Fons, Laura Pérez-Altable and Ariadna Fernández-Planells for their contribution to this research as well as Fridays For Future-Barcelona for their openness and goodwill.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1.^In the last decade, Catalonia, and Barcelona in particular, has experienced a wave of virtually uninterrupted mobilizations linked to, on the one hand, social and political struggles (reinforced by the 15 M), and on the other hand, to the issue of Catalonia’s independence.

2.^The * at the end of some of the keywords were used to include all the variants of these words. For example, “vulnerab*” accounts for “vulnerable” and “vulnerabilitat.”

References

1

Almeida P. Chase-Dunn C. (2018). Globalization and Social Movements. Annu. Rev. Sociol.44, 189–211. 10.1146/annurev-soc-073117-041307

2

Alwin D. F. (1994). “Aging, Personality, and Social Change: The Stability of Individual Differences over the Adult Life Span,” in Life-span Development and Behavior. Editors FeathermanD. L.LernerR. M.PerlmutterM. (Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates), 135–185.

3

Bell D. (1965). The End of Ideology: On the Exhaustion of Political Ideas in the Fifties. Glencoe: Free Press.

4

Bennett W. L. Segerberg A. (2012). The Logic of Connective Action. Inf. Commun. Soc.15 (5), 739–768. 10.1080/1369118X.2012.670661

5

Bobbio N. (1984). The Future of Democracy. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

6

Brennan B. Hoedeman O. Terhorst P. Kishimoto S. Balanyá B. (2005). Reclaiming Public Water: Achievements, Struggles and Visions from Around the World. Available at: https://www.tni.org/en/tnibook/reclaiming-public-water-book. 10.1093/0199256268.001.0001

7

Brock H. (2012). CLIMATE CHANGE: Drivers of Insecurity and the Global South. Available at: https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/146109/Climate Change and Insecurity in the Global South.pdf. 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195366556.013.0014

8

Burnham P. (2001). New Labour and the Politics of Depoliticisation. The Br. J. Polit. Int. Relations.3 (2), 127–149. 10.1111/1467-856x.00054

9

Cammaerts B. Bruter M. Banaji S. Harrison S. Anstead N. (2014). The Myth of Youth Apathy. Am. Behav. Scientist.58 (5), 645–664. 10.1177/0002764213515992

10

Cammaerts B. Bruter M. Banaji S. Harrison S. Anstead N. (2016). Youth Participation in Democratic Life: Stories of Hope and Disillusion. Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan. 10.1057/9781137540218

11

Castells M. (2015). Networks of Outrage and Hope: Social Movements in the Internet Age. 2nd ed.Cambridge: Polity.

12

Castells M. (1996). The Rise of the Network Society. Cambridge: Blackwell Publishers.

13

Chatterton P. Featherstone D. Routledge P. (2013). Articulating Climate Justice in Copenhagen: Antagonism, the Commons, and Solidarity. Antipode45, 602–620. 10.1111/j.1467-8330.2012.01025.x

14

Crouch C. (2004). Post-democracy. Hoboken: Wiley.

15

Dalton R. J. (2015). The Good Citizen: How a Younger Generation Is Reshaping American Politics. Washington DC: CQ Press.

16

della Porta D. Kriesi H. Rucht D. (2009). Social Movements in a Globalizing World. 2nd ed. (Palgrave Macmillan). Available at: https://cadmus.eui.eu/handle/1814/12446.

17

de Moor J. De Vydt M. Uba K. Wahlström M. (2020). New Kids on the Block: Taking Stock of the Recent Cycle of Climate Activism. Soc. Mov. Stud., 1–7. 10.1080/14742837.2020.1836617

18

Delanty G. (2014). The Prospects of Cosmopolitanism and the Possibility of Global justice. J. Sociol.50 (2), 213–228. 10.1177/1440783313508478

19

della Porta D. (2012). Critical Trust : Social Movements and Democracy in Times of Crisis. Cambio. Rivista.Sulle.Trasformazioni Sociali.2 (4), 33–43. 10.13128/cambio-19432

20

della Porta D. Mosca L. (2005). Global-net for Global Movements? A Network of Networks for a Movement of Movements. J. Pub. Pol.25 (1), 165–190. 10.1017/S0143814X05000255

21

Díaz-Pérez S. Soler-i-Martí R. Ferrer-Fons M. (2021). From the Global Myth to Local Mobilization: Creation and Resonance of Greta Thunberg's Frame. Comunicar: Media Edu. Res. J.29, 35–45. 10.3916/C68-2021-03

22

Dupuis-Déri F. (2021). Youth Strike for Climate: Resistance of School Administrations, Conflicts Among Students, and Legitimacy of Autonomous Civil Disobedience-The Case of Québec. Front. Polit. Sci.3, 634538. 10.3389/fpos.2021.634538

23

Earl J. Kimport K. (2011). Digitally Enabled Social Change: Activism in the Internet Age. Cambridge: MIT Press. 10.7551/mitpress/9780262015103.001.0001

24

Erikson E. Occhiuto N. (2017). Social Networks and Macrosocial Change. Annu. Rev. Sociol.43, 229–248. 10.1146/annurev-soc-060116-053633

25

Fawcett P. Flinders M. Hay C. Wood M. (2017). Anti-Politics, Depoliticization, and Governance. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

26

Fisher R. J. (1993). Social Desirability Bias and the Validity of Indirect Questioning. J. Consum Res., 20(2), 303–315. 10.1086/209351

27

Gills B. K. (2005). 'Empire' versus 'Cosmopolis': The Clash of Globalizations. Globalizations2 (1), 5–13. 10.1080/14747730500164828

28

Gizatova G. Ivanova O. Gedz K. (2017). Cosmopolitanism as a Concept and a Social Phenomenon. J. Hist. Cult. Art Res.6 (5), 25–30. 10.7596/taksad.v6i5.1294

29

Gordon D. F. (1984). The Role of the Local Social Context in Social Movement Accommodation: A Case Study of Two Jesus People Groups. J. Scientific Study Religion23 (4), 381–395. 10.2307/1385726

30

Groenewald C. (2000). Social Transformation between Globalization and Localization. Scriptura72, 17–29. 10.7833/72-0-1241

31

Hampton K. Wellman B. (2001). Long Distance Community in the Network Society. Am. Behav. Scientist.45 (3), 476–495. 10.1177/00027640121957303

32

Henn M. Oldfield B. Hart J. (2018). Postmaterialism and Young People's Political Participation in a Time of Austerity. Br. J. Sociol.69 (3), 712–737. 10.1111/1468-4446.12309

33

Hosseini S. A. H. Gills B. K. Goodman J. (2017). Toward Transversal Cosmopolitanism: Understanding Alternative Praxes in the Global Field of Transformative Movements. Globalizations14 (5), 667–684. 10.1080/14747731.2016.1217619

34

Inglehart R. (1997). Modernization and Postmodernization: Cultural, Economic, and Political Change in 43 Societies. Princeton: Princeton University Press. 10.1515/9780691214429

35

Jacomy M. Venturini T. Heymann S. Bastian M. (2014). ForceAtlas2, a Continuous Graph Layout Algorithm for Handy Network Visualization Designed for the Gephi Software. PLoS ONE9 (6), e98679. 10.1371/journal.pone.0098679

36

Johnson A. E. Wilkinson K. K. (2020). All We Can Save: Truth, Courage, and Solutions for the Climate Crisis. New York: One World.

37

Jungherr A. (2016). Twitter Use in Election Campaigns: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Inf. Tech. Polit.13 (1), 72–91. 10.1080/19331681.2015.1132401

38

Kavada A. (2015). Creating the Collective: Social media, the Occupy Movement and its Constitution as a Collective Actor. Inf. Commun. Soc.18 (8), 872–886. 10.1080/1369118X.2015.1043318

39

Koukouzelis K. (2017). Climate Change Social Movements and Cosmopolitanism. Globalizations14 (5), 746–761. 10.1080/14747731.2016.1217621

40

Miller B. Nicholls W. (2013). Social Movements in Urban Society: The City as a Space of Politicization. Urban Geogr.34 (4), 452–473. 10.1080/02723638.2013.786904

41

Miró J. (2021). Abolishing Politics In The Shadow of Austerity? Assessing The (De)Politicization Of Budgetary Policy In Crisis-Ridden Spain (2008–2015). Policy Studies42 (1), 6–23. 10.1080/01442872.2019.1581162

42

Moor J. (2020). Alternatives to Resistance? Comparing Depoliticization in Two British Environmental Movement Scenes. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res.44 (1), 124–144. 10.1111/1468-2427.12860

43

Nový M. Smith M. L. Katrňák T. (2017). Inglehart's Scarcity Hypothesis Revisited: Is Postmaterialism a Macro- or Micro-level Phenomenon Around the World?. Int. Sociol.32 (6), 683–706. 10.1177/0268580917722892

44

Polletta F. Gardner B. G. (2015). “Narrative and Social Movements,” in The Oxford Handbook of Social Movements. Editors Della PortaD.DianiM. (Oxford: Oxford University Press). 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199678402.013.32

45

Prell C. (2011). Social Network Analysis: History, Theory and Methodology. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications.

46

Pressman J. Choi-Fitzpatrick A. (2020). Covid19 and Protest Repertoires in the United States: an Initial Description of Limited Change. Soc. Mov. Stud., 1–8. 10.1080/14742837.2020.1860743

47

Prior M. (2010). You've Either Got it or You Don't? the Stability of Political Interest over the Life Cycle. J. Polit.72 (3), 747–766. 10.1017/S0022381610000149

48

Regan T. (2004). Empty Cages: Facing the Challenge of Animal Rights. New York: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

49

Schlosberg D. Collins L. B. (2014). From Environmental to Climate justice: Climate Change and the Discourse of Environmental justice. Wires Clim. Change.5, 359–374. 10.1002/wcc.275

50

Scott J. Carrington P. J. (2011). The SAGE Handbook of Social Network Analysis. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications.

51

Silva E. (2013). Transnational Activism and National Movements in Latin America: Bridging the Divide. 1st ed. (New York: Routledge). 10.4324/9780203489901

52

Simon B. Klandermans B. (2001). Politicized Collective Identity: A Social Psychological Analysis. Am. Psychol.56, 319–331. 10.1037/0003-066X.56.4.319

53

Sloam J. Henn M. (2019). Youthquake 2017: The Rise of Young Cosmopolitans in Britain. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. 10.1007/978-3-319-97469-9

54

Smith J. Wiest D. (2012). Social Movements in the World-System: The Politics of Crisis and Transformation. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

55

Snow, D. A. Soule, S. A. Kriesi, H. (2004). in The Blackwell Companion to Social Movements (Hoboken: Blackwell Publishing Ltd).

56

Soler-i-Martí R. (2015). Youth Political Involvement Update: Measuring the Role of Cause-Oriented Political Interest in Young People's Activism. J. Youth Stud.18, 396–416. 10.1080/13676261.2014.963538

57

Stodel M. (2015). But what Will People Think?: Getting beyond Social Desirability Bias by Increasing Cognitive Load. Int. J. Market Res.57 (2), 313–322. 10.2501/IJMR-2015-024

58

Strange S. (1996). The Retreat of the State. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 10.1017/cbo9780511559143

59

Tarrow S. McAdam D. (2005). “Scale Shift in Transnational Contention,” in Transnational Protest And Global Activism. Editors della PortaD.TarrowS. (New York: Rowman & Littlefield), 121–149. 10.1017/cbo9780511791055

60

Thompson C. (2020). #FightEveryCrisis: Re-framing the Climate Movement in Times of a Pandemic. Interface12 (1), 225–231. https://www.interfacejournal.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Interface-12-1-Thompson.pdf

61

Tilly C. (2004). Social Movements 1768-2004. London: Paradigm Publishers.

62

Tumasjan A. Sprenger T. Sandner P. Welpe I. (2010). Predicting Elections with Twitter: What 140 Characters Reveal about Political Sentiment. Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, Washington, DC, May 23–26, 2010, 4 (1), 178–185. Availble at: https://ojs.aaai.org/index.php/ICWSM/article/view/14009.

63

Urkidi L. (2010). A Glocal Environmental Movement against Gold Mining: Pascua-Lama in Chile. Ecol. Econ.70 (2), 219–227. 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2010.05.004

64

Voss K. Williams M. (2012). The Local in the Global: Rethinking Social Movements in the New Millennium. Democratization19 (2), 352–377. 10.1080/13510347.2011.605994

65

Wahlström M. Kocyba P. De Vydt M. de Moor J. (2019). Protest for a Future: Composition, Mobilization and Motives of the Participants in Fridays for Future Climate Protests on 15 March, 2019 in 13 European Cities. Retrieved from: https://osf.io/xcnzh/. 10.17605/OSF.IO/XCNZH

66

Williams M. (2008). The Roots of Participatory Democracy: Democratic Communists in South Africa and Kerala. India: Palgrave Macmillan US. 10.1057/9780230612600

67

Ypi L. (2012). Global Justice and Avant-Garde Political Agency. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Appendix Table A1 | Summarized codebook.

| Content/characteristic of the tweet | Indicators (dichotomous) |

|---|---|

| Interactions | Fridays For Future international: @mention of reference to international FFF groups (outside of Spain) |

| Fridays For Future local/national: @mention of reference to local/national FFF groups (inside of Spain) | |

| International movements: @mention of reference to international movements other than FFF (outside of Spain) | |

| Local/national movements: @mention of reference to local/national movements other than FFF (inside of Spain) | |

| Discourse | Climate change: mention or discourse related to the issue of climate change |

| Other issues: mention or discourse related to issues other than climate change (e.g., immigrants’ rights, feminism, access to public services, COVID-19) |

Appendix Figure A1 | Example of a tweet coded as i) interactions with local/national movements and ii) discourse on climate change.

Translation: Calendar of our colleagues from @BarrisPelClima! The climate emergency must be known across all neighborhoods and we need to fight it together.

Summary

Keywords

global social movements, fridays for future, climate change, social media, glocal, local, twitter, transversality

Citation

Terren L and Soler-i-Martí R (2021) “Glocal” and Transversal Engagement in Youth Social Movements: A Twitter-Based Case Study of Fridays For Future-Barcelona. Front. Polit. Sci. 3:635822. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2021.635822

Received

30 November 2020

Accepted

23 July 2021

Published

09 August 2021

Volume

3 - 2021

Edited by

Matt Henn, Nottingham Trent University, United Kingdom

Reviewed by

Sarah E. Pickard, Université de la Sorbonne Nouvelle Paris III, France

Ana IsabelNunes, Nottingham Trent University, United Kingdom

Updates

Copyright

© 2021 Terren and Soler-i-Martí.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ludovic Terren, lterren@uoc.edu

This article was submitted to Political Participation, a section of the journal Frontiers in Political Science

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.