95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Polit. Sci. , 22 June 2021

Sec. Elections and Representation

Volume 3 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2021.631363

This article is part of the Research Topic The Political Economy of Federalism and Multilevel Politics in Turbulent Times View all 6 articles

Olga Shvetsova1*

Olga Shvetsova1* Julie VanDusky-Allen2

Julie VanDusky-Allen2 Andrei Zhirnov3

Andrei Zhirnov3 Abdul Basit Adeel4

Abdul Basit Adeel4 Michael Catalano4

Michael Catalano4 Olivia Catalano5

Olivia Catalano5 Frank Giannelli6

Frank Giannelli6 Ezgi Muftuoglu4

Ezgi Muftuoglu4 Dina Rosenberg7

Dina Rosenberg7 Mehmet Halit Sezgin4

Mehmet Halit Sezgin4 Tianyi Zhao4

Tianyi Zhao4This essay examines the policy response of the federal and regional governments in federations to the COVID-19 crisis. We theorize that the COVID-19 policy response in federations is an outcome of strategic interaction among the federal and regional incumbents in the shadow of their varying accountability for health and the repercussions from the disruptive consequences of public health measures. Using the data from the COVID-19 Public Health Protective Policy Index Project, we study how the variables suggested by our theory correlate with the overall stringency of public health measures in federations as well as the contribution of the federal government to the making of these policies. Our results suggest that the public health measures taken in federations are at least as stringent as those in non-federations, and there is a cluster of federations on which a bulk of crisis policy making is carried by subnational governments. We find that the contribution of the federal government is, on average, higher in parliamentary systems; it appears to decline with the proximity of the next election in presidential republics, and to increase with the fragmentation of the legislative party system in parliamentary systems. Our analysis also suggests that when the federal government carries a significant share of responsibility for healthcare provision, it also tends to play a higher role in taking non-medical steps in response to the pandemic.

From the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, scholarly consensus has been that public health policies help mitigate the spread of the disease (Hsiang et al., 2020; Pueyo 2020). Did federal institutional design foster strategic incentives for political incumbents to adopt strong public health pandemic policies? In this essay we answer this question as a qualified “Maybe.” We base our conclusions on worldwide evidence of national and subnational public health policy responses during the onset period of the pandemic, in the winter-spring 2020 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2016). Here within we offer a theoretical framework for why governments of different levels behave differently in a crisis in differently designed federations and use data on pandemic policy-making to examine the response of federal and subnational incumbents.

During the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, federal institutions and federal political processes served to both constrain and incentivize politicians’ responses to this crisis. While federations on average adopted more stringent policies than unitary states (Shvetsova et al., 2020b), there was substantial variation across federations (e.g., VanDusky-Allen et al., 2020). The research has argued that federations have a greater supply of policy actors capable of generating the pandemic policy response; because these (redundant) actors can independently generate responses at national and subnational levels, such systems have the capacity to supply the necessary policy response faster (Shvetsova et al., 2020b). Yet the capacity for policy agents to act does not immediately imply the incumbents’ willingness to act. Indeed, strategic calculus may push them to the contrary. This is where our present argument is situated: which governments in a federation were willing to adopt the costly and painful public health policies to mitigate a pandemic? Which governments acted, and which effectively opted to “sit it out”? Did the federal institutional design influence pandemic policies insofar as where they were adopted (federally or subnationally) and how stringent they were overall?

Politicians’ response to a crisis involves the strategic choice that the incumbents in federations face in regard to whether to respond to the crisis by making a policy or to avoid taking responsibility. Forced to balance the ultimate health outcomes and the disruptive side-effects of public health measures, as both affect their own election prospects, elected officials, we assume, have carefully considered which policies to adopt or not adopt. As they were making these choices, they also tried to anticipate what the other policymakers were doing at the same time (Seabright 1996; Gersen 2010 p. 326). A public health policy action at one level spared the political incumbents at another level of government the possible costs of making the actual policies and the repercussions of a higher number of pandemic casualties.

We adopt the theoretical premise that expectations of popular (electoral) accountability underpin the strategic choices of the political incumbents at different levels of government. We theorize that the fear of possible repercussions from the adverse immediate effects of the public health measures, as well as the responsibility for health outcomes, depend on a host of institutional and political factors. We explore these factors both theoretically and empirically further in the paper.

Electoral accountability in general is considered to reflect retrospective judgment of the performance of government by the electorate. Voters simply look back at the election time to punish or reward the incumbent on the most significant issue areas. The pandemic-time accountability is harder to define because the issue dimensions and lines of division in the electorate are distinct from previous experience. Some guidance is offered by the literature on incumbent accountability in crisis management. First, evidence shows that voters view the negative outcomes of external shocks as at least in part the responsibility of the political incumbents. Electorates punish incumbents for disasters and catastrophes beyond their control such as weather events (Gasper and Reeves 2011), floods (Heersink et al., 2017), forest fires (Lazarev et al., 2014), earthquakes and tsunamis (Carlin et al., 2014), draughts and even shark attacks (Achen and Bartels, 2004) etc. The likelihood of the incumbent’s political survival decreases as the deaths in disasters and catastrophes increase (Flores and Smith 2013).1 What the literature does not tell us (due to the lack of evidence to draw meaningful comparisons), is whether this documented punishment holds incumbents accountable for the acts of nature, or for the shortcomings in their mitigation policies (as in: the pain of the disaster could have been less with better policy response), or even for the immediate hardships inflicted on the voters while implementing appropriate and necessary policy responses (e.g., Healy and Malhotra 2009). Any and all of these theoretical mechanisms can be the culprit.

Since federalism creates a particularly strong “clarity of responsibility problem,” it has been pointed out that the politicians can leverage this confusion inherent to the federal institutional arrangements and oftentimes evade responsibility for their actions (Powell and Whitten, 1993; Anderson, 2006; Hobolt et al., 2013). However, voters seem to hold appropriate actors accountable when issues on stake are salient and information regarding the responsible level is readily available (Arceneaux, 2006; Malhotra and Kuo, 2008; Leon, 2011). There is evidence that voters navigate the basics of institutional constraints and some financial fundamentals as they attribute responsibility to a specific level of government (Gasper and Reeves, 2011).

In the current pandemic we start seeing statistical and anecdotal evidence of targeted accountability both for the disruptive effects and for the health outcomes, as well as that accountability being channeled toward appropriate political incumbents. For example, in the early weeks of 2021, California Governor Gavin Newsom faced a threat of being recalled by California voters. The recall initiative was citing the slow roll out of vaccines in California compared to other states coupled with concerns of constrained economic activity, thus both the disruption and health-related grievances. Recall threat to Newsom was viewed as serious, despite his 50 percent approval rating and a pandemic year’s worth of praise from national and state leaders, including then President Donald Trump (Reston 2021). Leaders in the times of crizes situations understand that current circumstance, policymaking, and crisis decision-making can outweigh ideology and past accomplishments with the voters, and even the federal design itself can be brought into question (Leon and Garmendia Madariaga 2020).

There is more than one way in which the constituents are affected by the mitigation policies. First, such measures of course help reduce the transmission of communicable diseases, minimizing their damage to the human health from the virus and to the health care infrastructure from the magnitude of the virus spread. But in addition and adversely, such measures intrude into the daily activities of the residents: they reduce opportunities for trade and provision of services, change how people work and interact, disrupt the existing relations. Among other things, the mitigation policies aimed to slow the spread of the virus have carried heavy economic costs: dramatic slowing down of economic activity, reduced or negative growth, an increase in unemployment, and potentially a drastic economic restructuring.

Here we take as a sustained hypothesis that the political incumbents expect to incur the costs of the voters responding both to the pain of the policies themselves and to the horror of the final pandemic tally, conditionally on their pre-pandemic institutional role. We label the former as disruption electoral costs since they emerge primality from the disruption in the routine activities imposed by the public health measures. We label the electoral punishment for the negative health outcomes as “health” electoral costs. The incumbent can increase her utility both by avoiding policies that cause disruption and by making policies that keep people safe. It is of course immediately apparent that there is a tension between the policy decisions that could lead to these two objectives.

Decentralized policy making offered a hope for the incumbents at different levels that someone else could make the first painful step. As a result, as much as the incumbents might have valued the preservation of the public health, they had incentives to avoid taking the lead on imposing public health restrictions, waiting for the other governments to act. If an incumbent could avoid issuing stringent COVID-19 policies while benefitting from the stringent policies issued by the other level of government, she would generally prefer to do so. This is generally a possibility in federations, and only occasionally so in unitary states (Hollander 2010; Dardanelli et al., 2019; Adeel et al., 2020; Paquet and Schertzer 2020).

In this essay, we identify and discuss two facets of the incentives engendered by the federal institutional design that could drive governments’ strategies in public health policy responses to the pandemic. The first is the factors that concentrate or diffuse the electoral costs of adopting stringent mitigation policies for the national executives, including proximity of elections, political fragmentation of the decision-making bodies, and presidentialism. More concentrated accountability gives the incumbents a stronger motivation to avoid taking politically risky steps. The second is the institutions that determine which levels of government and to what extent are responsible for protecting population health. Whenever the federal government shares in the responsibility for healthcare with subnational governments, it may expect to be blamed for poor health outcomes caused by the uncontrolled health crisis.

In what follows, we address each of these in turn by comparing the public health policies of federal and unitary states as well as across the federations during the onset period of the pandemic, between January 24, 2020 and april 24, 2020 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2016). As our dependent variables we use the overall stringency of the public health restrictions imposed by april 24, 2021 (Shvetsova et al., 2020a) as well as the ratio of the stringency of the policies created by the federal government to the overall stringency of the restrictions imposed by the federal and subnational governments. Given the small number of observations and the observational nature of the data, our analyses can provide only suggestive evidence.

We start in the next section by defining and comparing the stringency of COVID-19 mitigation policies between federal and unitary states. This comparison establishes that federations did not under-perform as compared to unitary nations despite the coordination problem between the levels of government.2 We also show that more of the protective policy stringency can be attributed to subnational incumbents in federations than in unitary states. Following that and from Variation in Policy Responses Among Federal States on, we focus on federations only. In Variation in Policy Responses Among Federal States, we explore the effects of the political factors on the hesitance of the federal level to engage in painful policy making and introduce the institutional determinants of stronger accountability for health during the pandemic. In Institution in Healthcare and Variation in Policy Responses, we introduce the compound indicators capturing the variation of health-specific institutions in federations that affect the respective assignment of accountability for the health outcomes to governments at different levels. There we analyze the impact of institutions that structure governments’ involvement in health care on the strategic options that are available to political incumbents in crisis policy-making. Conclusion summarizes our observations and concludes.

As a first step in our inquiry, we compare federations’ performance in COVID-19 mitigation policy-making against the backdrop of the more globally numerous unitary states. Did the efforts invested by the incumbent differ between federations and non-federations, and more generally, between the more and less centralized polities? How much of such variation was attributable to the subnational governments supplying stringent public health policies?

The data that we use are publicly available as the Dataset on the Institutional Origins of COVID-19 Public Health Protective Policies (Shvetsova et al., 2020a). The data records and codes in multiple categories and on ordinal scales the COVID-19 mitigation policies adopted by national and subnational governments around the world. The fifteen public health categories include the initiation of a state of emergency, self-isolation and quarantine, border closures, limits on social gatherings, closings of schools, entertainment venues, restaurants, non-essential businesses, government offices, and public transportation systems, work from home requirements, lockdowns and curfews, and mandatory wearing of protective equipment. Note that between and within the policy categories, there is variation on their potential to stop the spread of coronavirus. To account for this variation, more restrictive policies are weighed more heavily in the index.3 The resulting Protective Policy Indices (PPIs) capture the extent to which the totality of the imposed measures tightens the channels through which the virus can be transmitted. They range between 0 and 1, where 0 refers to the absence of any restrictions, and one refers to the most severe restrictions along all the dimensions of transmission control, viz. complete closure of intra-state and interstate borders, closure of all non-essential businesses, ban on any gatherings, the mandates to the residents to stay at home, etc.

PPI measures in the dataset are calculated daily for each subnational unit as 1) based on federally issued policies only, 2) based on sub-nationally issued policies only, and 3) based on the most stringent policy level (either from federal or from subnational policies) in each of the constituent policy categories (Total PPI). For the purposes of the cross-national comparisons, we here are taking the national averages of PPIs for the subnational units, weighed by the units’ population shares: National, Average Subnational, and Average Total PPIs. The dataset covers 73 countries at national and subnational levels between January 24, 2020 and April 24, 2020. These 73 countries contain over 1,660 subnational units, each supplying daily PPI values. Nineteen countries in the dataset are federations as defined by their constitutions. The 19 federations among themselves contain 462 subnational units (the list of countries and included subnational units can be found in Supplementary Appendices S2, S3).

In what follows, we focus on the stringency of public health policies reached on April 24, 2020. This day marked roughly the endpoint of the period of non-decreasing public health response to COVID-19 pandemic worldwide. Thus, we will consider the stringency of public health policies on this day as indicative of how far individual governments were willing to go to protect public health when confronted with a global health emergency.

In Figure 1 we show the Average Total PPI for 73 countries as of April 24. The Figure distinguishes between the nations that are unitary according to their constitutions (hollow circles) and federal nations (filled triangles). At the same time, Average Total PPI in Figure 1 is plotted against the level of decentralization as measured by the Regional Authority Index (Hooghe et al., 2016) for unitary and federal states alike. Neither the countries that are federal by constitution, nor those scoring higher on the decentralization scale were behind in their achieved policy stringency. If anything, Figure 1 suggests that decentralization and federalism were associated with stronger overall public health pandemic response.

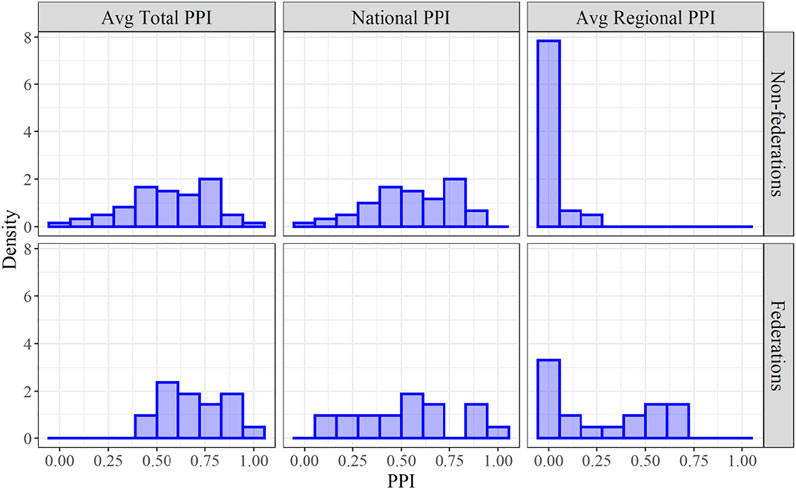

Figure 2 shows the distributions of the Average Total PPI, National PPI, and Average Regional PPI across countries broken down into federations and non-federations.

FIGURE 2. The distributions of achieved PPI among federations and non-federations, as of April 24, 2020.

The subsample of federations as a whole did better on the Average Total and the Average Regional PPIs. The Average Total PPI for federations was 0.69 while for non-federations it was 0.56. But it is the variation in the federal subsample that draws the eye. The distributions of the National and Average Subnational PPI among federations exhibit clear bi-modality: in addition to a cluster of cases in which the central government takes almost all responsibility for making public health policies, federations include a cluster of cases in which the subnational governments take over a large share of responsibility for public health policy-making. Thus, federations achieved same or better overall public health protection via a pattern of government action different from that in unitary states (i.e., the Average Subnational PPI for federations is 0.28 while for non-federations it is 0.02). In federations the policies made at the subnational level may have compensated for the lack of the policies made at the national level and/or might make national level policy-making unnecessary. The other observation is that the combinations of policy strategies of national and subnational governments differed within the federal subsample. Whether this was influenced by their institutional design, and if so then how, is the puzzle that we seek to address below.

As in Figures 1, 2, federations on average invested at least as much policy-making effort in limiting the spread of the pandemic as did the unitary states, and this effort was on average more evenly spread between national and subnational authorities. While there was some overlap when similar policies were in place as issued by both national and subnational governments, overall, we see evidence of the substitution effect in Figures 3, 4 in the next section, where one level of government does what the other did not do in terms of the overall mitigation effort (the Pearson correlation between Average Subnational PPI and National PPI is at −0.51). What we also see, however, is that the relative roles of national vs. subnational governments in COVID-19 policy-making varied drastically across federations.

Figure 3 plots Average Subnational PPI against National PPI for all federations. Notice that the coordinates add up to more than one for several of them, reflecting the duplication of policies at the two levels of government. Still, there is a visual effect of a negative diagonal in Figure 3, combined with more concentration of observations in the upper left and lower right corners.4 Thus we have an indication that many federations have somehow converged to a combination of strategies of the two levels of government where either one of them or the other emerged as the COVID-19 mitigation leader.

The plot in Figure 4 shows the ratio of Average Regional to Average Total PPIs as plotted against the ratio of National Average Total PPIs. These statistics indicate, respectively, what share of the Average Total PPI would have remained had the other government level not engaged in the public health policy making. Observe that if there were no overlap in policies in place due to federal and subnational government on a given day, all observations should have been on the dotted negative diagonal. This is close to being the case in Austria, Belgium, Nepal, Nigeria, South Africa, Switzerland, and Venezuela. Pakistan, India, and Australia are in a group where the overlap in policy-making–policy duplication at national and subnational levels—was the greatest. Most of the times this overlap resulted from the federal government issuing guidelines on specific aspects of mitigation policies and the subnational governments implementing these guidelines into public policies. Notice also that if one level of government fully abstained from COVID-19 policy-making, the resulting observation would be located in wither top-left or bottom-right vertices of the coordinate box. These calculations do not account for the policies adopted by municipal governments, which were a significant influence in large urban centers.

Two federations—Nigeria and the United States—saw the most disengaged federal governments, closely followed by Canada and Russia. Since the PPI dataset codes only actual announced policies and disregards informal recommendations and public service statements, Trudeau’s cabinet in Canada ended up in this group, despite a possibly valid argument that their rhetoric at the national level had significantly influenced Canadians’ protective behavior in the pandemic.

Thus, in Figure 4 we see significant variation in the extent to which regional and federal governments share in supplying the public health measures as they existed in the federation in question. Some countries saw a bias toward federal decision-making, others toward sub-national, and there were also instances of relative parity between government levels in terms of their assumed policy responsibility for pandemic mitigation.

We hypothesize that such variation is to a large degree due to the asymmetries in the accountability of national and subnational incumbents. Such asymmetries can be defined both politically and institutionally: due to the electoral pressures and the institutionally defined responsibility for health. Here we endeavor to take a closer look at the determinants of these asymmetries.

Politicians’ willingness to engage in mitigation policies depends on the balance between wanting to avoid the disruption of the pre-existing economic and social relationships and activities vs. wanting to minimize pandemic casualties. One of the characteristics affecting this balance was the relative immediacy of the disruptive effects. Even where these disruptions were less than elsewhere, in the short term the effect was inevitably negative as compared to the pre-pandemic economic and societal status-quo. Once the public health measures were adopted, changes in economic well-being were instantly measurable at both individual and societal levels (Deb et al., 2020; Desierto and Koyama 2020; Pulejo and Querubin 2020). Meanwhile, the pandemic health toll in the period under review was near-catastrophic in only a few subnational jurisdictions globally, and so credit for the health benefits was hard to claim. If our reasoning holds, the electoral costs for adopting more stringent policies would be higher for incumbents who face elections sooner rather than later, which would lead the incumbents facing immediate re-election to adopt less stringent policies than incumbents not facing impending elections.

The first parameter influencing national incumbents’ expected accountability for the disruptive effects of mitigation policies is the proximity of federal elections, measured as the time (months) until the next election of the national executive (counting from April 1, 2020).5 It turns out that only the United States was facing the impending election of the federal executive, and also very soon, in just over half a year from our benchmark April 1, 2020 date. Hence, we would expect to observe a less stringent government response to the COVID-19 crisis by the United States federal government as compared to other national governments.

Figure 5 shows the ratio of National PPI to Average Total PPI plotted against the time from April 2020 to next scheduled election that form the national executive, separately for the presidential and parliamentary federations. The remaining time until next elections is correlated with federal contribution to protective policies as dictated by our theory (Pearson’s correlation coefficient is 0.54), and this association appears stronger among presidential federations: the United States, Brazil, and Nigeria have the fastest coming elections among the presidential federations, and they also have the lowest contribution of the national government to PPI. It goes without saying that it is impossible to say anything definitive given the number of observations.

The clarity of individual accountability of the federal executive could also affect the weight the executive placed on the disruption electoral costs. The executive structure and the number of parties in the federal executive are among the variables that could affect this clarity of accountability and thereby amplify or reduce the incentives to avoid taking politically risky steps. Generally speaking, given that the executive is unilaterally and directly electorally accountable in presidential systems and in single party, majority parliamentary governments but not in multiparty parliamentary systems, presidents and prime ministers of single party, majority governments have more of a disincentive to take on policymaking on a politically risky issue than prime ministers of multiparty governments (Strom, 2000; Carey 2009). Presidentialism in particular focuses the electoral costs of risky policymaking on an incumbent, thus the policy effectiveness of presidentialism (Shugart and Carey 1992) can turn into policy hesitancy where there is a very real fear that policymaking might go poorly.

It would make sense then to expect the national level in federations with presidential and single party, majority executives to take a less active role in addressing the crisis. They should prefer that sub-national governments assumed full accountability if possible. The Russian vignette from the pandemic onset period illustrates how presidents in federal systems can place the burden of policymaking on subnational policymakers during a crisis. As COVID-19 was spreading through the country, President Putin personally granted everyone in the country a two-week paid vacation. He then blamed the inevitable spike in cases on regional governments not having implemented strong enough mitigation measures.

Evidence for our sample does not contradict this reasoning as Figure 6 illustrates. It plots the same variable, ratio of stringency of federally adopted policies to stringency of all policies (Ratio of National to Average Total PPIs) against the number of parties in the national executive. There is no conclusive evidence that diffusion of individual accountability makes national incumbents more willing to take a lead in pandemic mitigation. Future research with expanded sample will be needed to explore the possibility.

Figure 7 further investigates the potential effect of the multipartism in the lower legislative chamber (as measured by the effective number of legislative parties) on the National to Average Total PPI ratio. Because we would expect Cabinets to further share accountability with the parliamentary floor, while in presidents’ case the fragmented legislature only further stresses their personal accountability for policies, it is not a surprise that this latest effect appears to be distinctly different in the two constitutional systems. There is a modest positive correlation between the ENLP and the National to Average Total PPI ratio for the parliamentary federations (Pearson’s correlation coefficient is 0.32 for this subsample). There is no similar effect for presidential federations.

In Supplementary Appendix S5 we also report the association between the block partisanship of the national head of the executive branch (parties grouped in binary blocks as defined by Bartolini and Mair (2007) and the stringency of national policies. While the theoretical connection remains unclear, it appears that Left incumbents produced more stringent national policies than their Right counterparts.

In the normal course of things, the inclination to wait for the other level of government to act first in the risky areas of concurrent or unassigned/residual jurisdictions is resolved through the federal process, via the mechanism of “federal balancing”. Some scholars of federalism view the entire de facto division of responsibilities between the national and subnational incumbents, beyond the formal jurisdictional delineation, as an ever-shifting outcome of federal bargaining and balancing (Riker 1964; Filippov et al., 2004). While the constitution roughly outlines who does what in a federation, in addition to what it says, there are infinitely many specifics of the allocation of responsibilities and powers, which are being continuously renegotiated by the incumbents in the careful interactions within and across governments and extra-governmental organizations. The drastically reduced time and information for navigating and negotiating pandemic policy-making roles has distorted the flow of federal balancing, where incumbents had freedom to strategically choose whether to act on pandemic mitigation or not.

We believe that the institutional asymmetries in assigning the “duty of care” for the health of the public to one level of government rather than the other enabled some of them to remain relatively passive, while others had to act. If the federal government is not assigned any substantial responsibility for health outcomes, regional governments would be less likely to expect a strong federal action, and so would be forced to act on their own in introducing public health policies.

The balance of accountability across the levels of government in a federation for the ultimate health outcome depends on how institutions link political incumbents to healthcare—on the arrangements for provision and organization of healthcare prior to the onset of the COVID-19 public health crisis. Another influence on the prospective pattern of accountability were the status-quo healthcare practices beyond institutional prescriptions, which reflected, among other things, the role of non-governmental (e.g., private but also other) actors in health. These institutional and process variables, we posit, have jointly determined whether political incumbents 1) were to be accountable for the pandemic health outcomes at all, and if so, the expected magnitude of that accountability, and 2) which among them were to feel the brunt of that accountability.

We will consider that the level or levels of government that act as the “doctor to the public,” so to speak, will be perceived accountable for the health outcomes of the pandemic. An incumbent in this institutionally defined role would have positive incentives to attempt to improve the health outcomes through the making of public health policies (or, in other words, she would face a higher cost from non-acting). The institutions and the processes by which healthcare is organized and delivered in a federation, then, can serve as a proxy for the federal balance of accountability in health (Riker 1964; Filippov et al., 2004; Benz and Sonniksen 2017; Mershon and Shvetsova 2019).

Is healthcare provided by the government? Does government pay medical professionals to care for the patients? Does it financially underwrite individual medical needs? From the many institutions or rules that describe health sector organization in our federations, we build just two indicators in order to assess the respective degree or accountability for health of the federal and subnational governments. Which level of government is the “doctor” is captured by the Federal Government’s Accountability for Health—the extent to which the federal level of government takes over the accountability for health from the subnational governments.6 Meanwhile, how much the population relies on the government as a “doctor”, Government share, will depend on the government market share in the healthcare sector at large (as opposed to the responsibility of the private sector and medical professionals). Where it is available for the federations in our sample, we construct these two indicators using a number of decision-space statutory, financial, and process parameters and the existing literature on decision space in health pioneered by Bossert (1998). Where such literature is not available, we apply the decision-space method and provide original coding (See Supplementary Appendix Table S4.1 in Supplementary Appendix S4).

In every federation in our sample, insofar as governments deliver healthcare at all, this is done at the subnational level or below. Nowhere among the federations does the national government lead in health care delivery. Because this does not vary in our current sample, to operationalize the federal-subnational balance of authority over health (Mershon and Shvetsova 2019) and thus the governments’ respective accountability for health outcomes, is reduced to ascertaining the expected federal incumbent accountability for pandemic health. Since the sub-national incumbent is always accountable, the Federal Government’s Accountability for Health variable gives us the information about whether or not the subnational level can expect help form the federal level in crisis policy-making, or maybe even can fully defer such policy making “up”.

We operationalize the Federal Government’s Accountability for Health variable by weighing in two decision-space components that each might imply federal government’s residual accountability: whether it has an explicit constitutional mandate to protect health, and whether it plays a de facto dominant role among governments in financing government health efforts, i.e., via transfers to subnational governments (see the details in Supplementary Appendix S6). We code Federal Government’s Accountability for Health as High where the constitution tasks the federal government with preserving health and the federal government plays a high role in the government health financing (over 50 percent of all government health spending, see Supplementary Appendix S6). We code it as Low if there is no such constitutional assignment and the federal role in government health financing is low, and we code it in the middle category for the other two contingencies.

We suspect that the division of responsibility for health between the federal and subnational levels outside of the pandemic may affect which government level would lead in the pandemic public health response. Where Federal Government’s Accountability for Health is low, we expect to see less to be done by the federal level, and policy-making takes place mostly at the sub national level.

How stringent will be the policies that governments create to protect the public from health losses? We conjecture that the policy stringency will go up with the increase of the health “market share” controlled by the government. If the previous sub-section addressed the question of which levels of government have the greater “duty of care”, here the question is: Does the government have the “duty of care” on health at all? To what extent is health viewed by the public as the responsibility of governments—what is the “magnitude” of government accountability in health? Is there a firm expectation of any government’s accountability for the ultimate health outcome in the federation?

While much of the world will find such a question strange, it is not so long ago that health was considered a private matter everywhere, and indeed where the government involvement in health provision is low, we can conjecture, it might still be seen as such today by a large portion of the population. Furthermore, many advanced industrial democracies have empowered separate organizations (e.g., sickness funds) with characteristics of legislatively regulated non-profits, to run their healthcare. The fact that the revenue is received by those funds via legally mandated contributions does not make those contributions into fiscal revenue or adds them to government budgets. The operation of these public healthcare organizations is thus extra governmental and is not a daily responsibility of countries’ respective governments. The perception of the government responsibility for the health outcomes may be low when the sickness fund acts as the “doctor to the public” or when most of health care access is privately managed, in weakly regulated insurance markets or out of pocket.

Conjecturing that the combined “market share” of governments of all levels in health can be taken as a proxy for whether the public will look to the government for pandemic protection, we code the binary Government Role in care variable, based on the share of government expenditures (in all levels of government) in total health expenditures in a federation (see Supplementary Appendix Table S4.1). Notice, that these are government expenditures only, and not public expenditures as often reported, since those might include sickness funds budgets. The expectation is that the extent of government role in health as opposed to the role of public non-government agencies (e.g., sickness funds) and private actors will affect the stringency. Where governments play a larger role in healthcare, more stringent policies should be introduced than where governments play a smaller role.

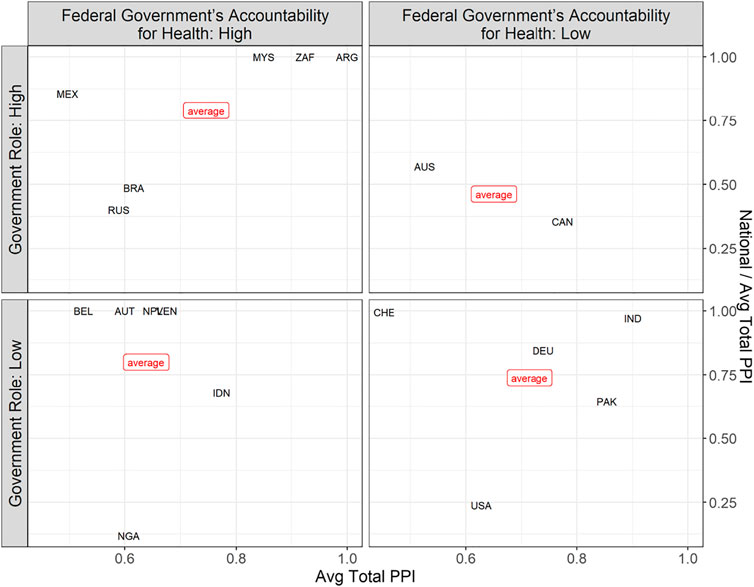

The indicators that we thus obtain capture a federation’s specific balance of accountability on health as well as the overall intensity of governments’ combined role in health and thus presumably the magnitude of their accountability on the issue7. Figure 8 shows the breakdown of our sample according to these variables, and Figure 9 summarizes our expectations for the combination of these variables.

In Figure 10, we use Average Total PPI and the ratio of National PPI to Average Total PPI to test our expectations about the leadership of the national and subnational level incumbents in the adoption of public health measures and their overall strength. Here, again, we rely on the policies initiated by the end of April. By then, the cross-national differences in threat levels have diminished, as the cases of COVID were present everywhere in our sample at that time.

FIGURE 10. Measures of PPI and the government role in health and federal government’s accountability for health.

Figure 10 divides our sample into four panes, each pane corresponding to a quadrant in Figures 9, 10. Each pane presents a scatterplot with two variables: total PPI and the national contribution to total PPI, with the values on each of these dependent variables plotted across the main predictor of that variable. To see if the national contribution to total PPI depends on Federal Government’s Accountability for Health, we need to compare the positions of countries along the vertical axis between the panes on the left and the panes on the right. To see if Average Total PPI depends on Government Role, we need to compare the positions of countries along the horizontal axis between the top and bottom panels.

The chart offers support to our expectation linking the Federal Government’s Accountability for Health to the ratio of national to total PPI. On average, the values of our dependent variable are higher in the left panes than in the right panes. With the exception of Brazil, Russia, and Nigeria, federations with a relatively high values of Federal Government’s Accountability for Health have seen high contributions of the federal government to the public health policies. With the exception of Switzerland, the systems with a lower Federal Government’s Accountability for Health have seen lower contributions of the federal government to the public health policies.

Note that all four exceptions have lower than average stringency of the overall response and this might be one of the reasons for us to downweigh these observations in the comparisons of the federal contribution to the total PPI. We could also speculate that the short-term electoral incentives also contribute to the unexpectedly low contribution of Brazil’s, Nigeria’s, and Russia’s federal governments and the unexpectedly high contribution of the Swiss federal government to the COVID-19 policy making. Brazil, Nigeria, and Russia are presidential federations with a large share of responsibility vested in the president, which inflates the short-term risks of pandemic response faced by the federal executive. Switzerland is a parliamentary federation with a politically fragmented federal legislature and fragmented executive.

Our expectation regarding the overall level of protection does not seem to hold. For it to hold, we should have observed the countries in the top panels further to the right than the countries in the bottom panels.

In this essay, we sought to explore whether political incumbents’ strategies in mitigating the health emergency of the COVID-19 pandemic were influenced in federations by the constitutional/electoral and health-related political institutions. Specifically, we developed conjectures about the institutional variables conducive to more stringent public health policies and about institutional determinants of greater involvement of the federal government in pandemic public health policies. Below are the main take-away points from our exploratory analysis:

- Federalism and decentralization did not diminish the stringency of the overall government pandemic response; if anything, early response in federations was more, not less stringent

- Multiple levels of government contributed to the policy response to COVID-19 infection in federations

- There was substantial overlap—policy duplication—at national and subnational levels

- There is a substantial variation in the federal sample, approaching bi-modality, in terms of the relative policy efforts of national vs. subnational incumbents, which we conjecture requires an institutional explanation

- Presidential national executives were possibly more averse to stringent policy-making closer to the date of the next election

- Diffusion of executive accountability, such as in a multiparty executive and with more fragmented parliaments possibly increased the willingness to engage in more stringent policy response to the virus

- National incumbents with Left block-partisanship were associated with more stringent mitigation policy-making than national incumbents with Right block-partisanship

- Institutional accountability for health variables, which we construct form decision-space in healthcare indicators, are potentially useful predictors of policy engagement across government levels

- Whether accountability for health would revert to the federal government in a case of subnational mismanagement correlates with the degree of involvement of the federal incumbent in COVID-19 mitigation policy-making

- Government market share in healthcare does not seem to affect the overall mitigation policy stringency (Total PPI) in the current sample of 19 federations.

Future research and more data would allow us to further validate or qualify these admittedly preliminary observations. In-depth country studies will explore the richness and complexity that transpired in pandemic policy-making in these nations. Here we can conclude that, depending on their institutional design, federations approach crisis management very differently. When federal and subnational incumbents share the responsibility for crisis response and yet each of them has incentives to avoid making difficult decisions, the overall strength of the public health response depends on whether the incumbents at different levels of government succeed in coordinating to an equilibrium where at least one of them provides the necessary policies. Our evidence shows that by and large the coordination among the federal and subnational government in federations did not fail, and the incumbents in federations collectively managed to provide at least as much protection to their citizens as the incumbents in unitary states, though the balance of federal vs. subnational policy contributions varied. The leadership of the federal government depended on its overall role in the provision of health-care, as well as the relative lack of immediate retribution of the disruptive consequences of public health measures.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

All authors contributed to data collection, data analysis, and writing.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The authors wish to express thanks for the contributions from Onsel Bayrali and Didem Seyis, and for invaluable data work by Dominic Bossey, Kaya Doyle, and Aidan Stevens. We thank Binghamton University, Boise State University, University of Exeter, National Research University Higher School of Economics, and Rutgers for providing the effective research environment and solid infrastructure support during this pandemic, which made this project possible. The authors acknowledge that we own any remaining deficiencies in this paper.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2021.631363/full#supplementary-material

1Some argue that voters do not act as rational principals in these circumstances as their judgments are clouded by attribution bias wrongfully attributing the financial and human toll to their incumbents in “blind retrospection” (Achen and Bartles, 2004). For social psychologists, voters inflict undue costs on the incumbents: their decisions are marred by cognitive biases (Tversky and Kahneman 1974), are inclined to oversample negative information (Rozin and Royzman 2001), and have clouded judgment due to negative emotional response to the catastrophe (Malhotra and Kuo 2009). While these may contribute to the variance, we here are looking for the politicians’ anticipation of rationality-based accountability.

2Arguably, the very multiplicity and duplication of their decision nodes of policy making made federations as decision systems more responsive to the onset of this new threat (Shvetsova et al., 2020b)

3See the Supplementary Appendix S1 for a complete list of the policy categories, specific policies, and their weights in the index.

4The correlation between the Average Regional and National PPIs among federations is −0.52.

5Supplementary Appendix S4 lists time to election for the federations in our sample.

6We omit here the discussion of another institutional indicator, Primary government level in care provision. In our federal sample there is no variation in this variable and the subnational level is the main level for primary care. See Supplementary Appendix S6 for the operationalization of this indicator and country information.

7This economic policy coding roughly corresponds to the main for Bartolini and Mair (2007 p. 46), class cleavage conceptualization of party blocks for Europe.

Achen, C. H., and Bartels, L. M. (2004). Blind Retrospection: Electoral Responses to Drought, Flu, and Shark Attacks. Estudio/Working Paper 2004/199.

Adeel, A. B., Catalano, M., Catalano, O., Gibson, G., Muftuoglu, E., Riggs, T., et al. (2020). COVID-19 Policy Response and the Rise of the Sub-national Governments. Can. Public Pol. 46 (4), 565–584. doi:10.3138/cpp.2020-101

Anderson, C. D. (2006). Economic Voting and Multilevel Governance: A Comparative Individual-Level Analysis. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 50 (2), 449–463. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5907.2006.00194.x

Anifalaje, A. A. (2009). Decentralisation and Health Systems Performance in Developing Countries. Int. J. Healthc. Deliv. Reform Initiatives (Ijhdri) 1 (1), 25–47. doi:10.4018/jhdri.2009010103

Arceneaux, K. (2006). The Federal Face of Voting: Are Elected Officials Held Accountable for the Functions Relevant to Their Office?. Polit. Psychol. 27 (5), 731–754. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9221.2006.00530.x

Bachner, F., Bobek, J., Habimana, K., Ladurner, J., Leuschutz, L., Ostermann, H., et al. (2018). Austria: Health System Review.

Balarajan, Y., Selvaraj, S., and Subramanian, S. (2011). Health Care and Equity in India. The Lancet 377 (9764), 505–515. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(10)61894-6

Bartolini, S., and Mair, P. (2007). Identity, Competition and Electoral Availability: The Stabilisation of European Electorates 1885-1985. ECPR Press.

Benz, A., and Sonnicksen, J. (2017). Patterns of Federal Democracy: Tensions, Friction, or Balance between Two Government Dimensions. Eur. Pol. Sci. Rev. 9 (1), 3–25. doi:10.1017/s1755773915000259

Bossert, T. (1998). Analyzing the Decentralization of Health Systems in Developing Countries: Decision Space, Innovation and Performance. Soc. Sci. Med. 47 (10), 1513–1527. doi:10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00234-2

Carey, J. M. (2009). Legislative Voting and Accountability. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511810077

Carlin, R. E., Love, G. J., and Zechmeister, E. J. (2014). Natural Disaster and Democratic Legitimacy. Polit. Res. Q. 67 (1), 3–15. doi:10.1177/1065912913495592

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2016). The Continuum of Pandemic Phase. ” National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases (NCIRD)Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/pandemic-resources/planning-preparedness/global-planning.html.

Chee, H. L. (2008). Ownership, Control, and Contention: Challenges for the Future of Healthcare in Malaysia. Soc. Sci. Med. 66 (10), 2145–2156. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.01.036

Chua, H. T., and Cheah, J. C. H. (2012). June. Financing Universal Coverage in Malaysia: a Case Study. BMC public health 12 (No. 1), 1–7. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-12-s1-s7

Danishevski, K., Balabanova, D., Mckee, M., and Atkinson, S. (2006). The Fragmentary Federation: Experiences with the Decentralized Health System in Russia. Health Pol. Plann. 21 (3), 183–194. doi:10.1093/heapol/czl002

Dardanelli, P., Kincaid, J., Fenna, A., Kaiser, A., Lecours, A., Singh, A. K., et al. (2019). Dynamic De/centralization in Federations: Comparative Conclusions. Publius: J. Federalism 49 (1), 194–219. doi:10.1093/publius/pjy037

Daryanani, S. (2017). When Populism Takes over the Delivery of Health Care: Venezuela, 11. ecancermedicalscience. doi:10.3332/ecancer.2017.ed73

Deb, Pragyan., Furceri, Davide., Ostry, Jonathan. D., and Tawk, Nour. (202017 June 2020). The Economic Effects of COVID-19 Containment Measures. VoxEUAvailable at https://voxeu.org/article/economic-effects-covid-19-containment-measures.

Desierto, Desiree., and Koyama, Mark. (2020). Health vs. Economy: Politically Optimal Pandemic Policy. Available at doi:10.2139/ssrn.3661650

Filippov, Mikhail., Peter, Ordeshook., and Shvetsova, Olga. (2004). Designing Federalism: A Theory of Self-Sustainable Federal Institutions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511610875

Flores, A. Q., and Smith, A. (2013). Leader Survival and Natural Disasters. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 43 (4), 821–843.

Gasper, J. T., and Reeves, A. (2011). Make it Rain? Retrospection and the Attentive Electorate in the Context of Natural Disasters. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 55 (2), 340–355. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5907.2010.00503.x

Gerkens, S., and Merkur, S. (2010). Belgium: Health System Review. Health Syst. Transit. 12 (5), 1–xxv.

G. P. Marchildon, and T. J. Bossert (2018). in Federalism and Decentralization in Health Care: A Decision Space Approach (University of Toronto Press).

Gupta, I. (2020). India., in International Health System Profiles. Roosa Tikkanen, Robin Osborn, Elias Mossialos, Ana Djordjevic.The Commonwealth Fund. Editor George. A. Wharton. Available at https://www.commonwealthfund.org/international-health-policy-center/countries/india.

Healy, A., and Malhotra, N. (2009). Myopic Voters and Natural Disaster Policy. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 103 (3), 387–406. doi:10.1017/s0003055409990104

Heersink, B., Peterson, B. D., and Jenkins, J. A. (2017). Disasters and Elections: Estimating the Net Effect of Damage and Relief in Historical Perspective. Polit. Anal. 25 (2), 260–268. doi:10.1017/pan.2017.7

Hobolt, S., Tilley, J., and Banducci, S. (2013). Clarity of Responsibility: How Government Cohesion Conditions Performance Voting. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 52 (2), 164–187. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6765.2012.02072.x

Hollander, R. (2010). Rethinking Overlap and Duplication: Federalism and Environmental Assessment in Australia. Publius: J. Federalism 40 (1), 136–170. doi:10.1093/publius/pjp028

Hooghe, L., Marks, G., Schakel, A. H., Chapman Osterkatz, S., Niedzwiecki, S., and Shair-Rosenfield, S. (2016). Measuring Regional Authority: A Postfunctionalist Theory of Governance, I. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hsiang, S., Allen, D., Annan-Phan, S., Bell, K., Bolliger, I., Chong, T., et al. (2020). The Effect of Large-Scale Anti-contagion Policies on the COVID-19 Pandemic. Nature 584, 262–267. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2404-8

Lazarev, E., Sobolev, A., Soboleva, I. V., and Sokolov, B. (2014). Trial by Fire: a Natural Disaster's Impact on Support for the Authorities in Rural Russia. World Pol. 66 (4), 641–668. doi:10.1017/s0043887114000215

León, S., and Garmendia Madariaga, A. (2020). Popular Reactions to External Threats in Federations. Working Paper. September.

León, S. (2012). How Do Citizens Attribute Responsibility in Multilevel States? Learning, Biases and Asymmetric Federalism. Evidence from Spain. Elect. Stud. 31 (1), 120–130. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2011.09.003

León, S. (2011). Who Is Responsible for what? Clarity of Responsibilities in Multilevel States: The Case of Spain. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 50 (1), 80–109. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6765.2010.01921.x

Lührmann, A., Düpont, N., Higashijima, M., Berker Kavasoglu, Y., Marquardt, K.L., Bernhard, M., et al. (2020). Codebook Varieties of Party Identity and Organization (V–Party) V1. Varieties of Democracy (V–Dem) Project. doi:10.23696/vpartydsv1

Malhotra, N., and Kuo, A. G. (2008). Attributing Blame: The Public's Response to Hurricane Katrina. J. Polit. 70 (1), 120–135. doi:10.1017/s0022381607080097

Malhotra, N., and Kuo, A. G. (2009). Emotions as Moderators of Information Cue Use. Am. Polit. Res. 37 (2), 301–326. doi:10.1177/1532673x08328002

Marten, R., McIntyre, D., Travassos, C., Shishkin, S., Longde, W., Reddy, S., et al. (2014). An Assessment of Progress towards Universal Health Coverage in Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa (BRICS). The Lancet 384 (9960), 2164–2171. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(14)60075-1

Meng, Q., Yang, H., Chen, W., Sun, Q., and Liu, X. (2015). People’s Republic of China Health System Review. Health Syst. Transit. 5 (7).

Mershon, C., and Shvetsova, O. (2019). Traditional Authority and Bargaining for Legitimacy in Dual Legitimacy Systems. J. Mod. Afr. Stud. 57 (2), 273–296. doi:10.1017/s0022278x19000065

Miharti, S., Holzhacker, R. L., and Wittek, R. (2016). “Decentralization and Primary Health Care Innovations in Indonesia,” in Decentralization and Governance in Indonesia. Development and Governance. Editors R. Holzhacker, R. Wittek, and J. Woltjer (Cham: Springer), 2, 53–78. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-22434-3_3

Palacios, A., Espinola, N., and Rojas-Roque, C. (2020). Need and Inequality in the Use of Health Care Services in a Fragmented and Decentralized Health System: Evidence for Argentina. Int. J. equity Health 19 (1), 1–14. doi:10.1186/s12939-020-01168-6

Paquet, M., and Schertzer, R. (2020). COVID-19 as a Complex Intergovernmental Problem. Can. J. Pol. Sci. 53, 343–347. doi:10.1017/S0008423920000281

Popovich, L., Potapchik, E., Shishkin, S., Richardson, E., Vacroux, A., Mathivet, B., et al. (2011). Russian Federation: Health System Review.

Powell, G. B., and Whitten, G. D. (1993). A Cross-National Analysis of Economic Voting: Taking Account of the Political Context. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 37 (2), 391–414. doi:10.2307/2111378

Pueyo, T. (2020). “Coronavirus: Why You Must Act Now. Politicians, Community Leaders and Business Leaders: what Should You Do and when.” Medium. Available at https://medium.com/@tomaspueyo/coronavirus-act-today-or-people-will-die-f4d3d9cd99ca March 10, 2020.

Pulejo, Massimo., and Querubin, Pablo. (2020). Electoral Concerns Reduce Restrictive Measures during the COVID-19 Pandemic. NBER Working Paper No. 27498. Available at https://www.nber.org/papers/w27498. doi:10.3386/w27498

Rakmawati, T., Hinchcliff, R., and Pardosi, J. F. (2019). District‐level Impacts of Health System Decentralization in Indonesia: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Health Plann. Mgmt 34 (2), e1026–e1053. doi:10.1002/hpm.2768

Reston, M. (2021). “Newsom Faces Intensifying Recall Threat as Pandemic Frustrations Grow in California.” CNN Politics. Available at https://www.cnn.com/2021/02/06/politics/gavin-newsom-recall-california-pandemic-frustrations/index.html February 6. Last Accessed February 21, 2021).

Riker, William. (1964). Federalism: Origin, Operation, Significance. Boston: Little Brown & Co. doi:10.4271/640472

Robinson, F., Teo, R., and Mohd Zali, S. M. I. R. (2020). COVID-19 Healthcare Management in Sabah. Bjms, 1. doi:10.51200/bjms.vi.2607

Rozin, P., and Royzman, E. B. (2001). Negativity Bias, Negativity Dominance, and Contagion. Pers Soc. Psychol. Rev. 5 (4), 296–320. doi:10.1207/s15327957pspr0504_2

Schokkaert, E., Van de Voorde, C., Crainich, D., De Maeseneer, J., De Spiegelaere, M., Dormont, B., et al. (2011). Belgium’s Healthcare System Should the Communities/Regions Take It Over.

Seabright, P. (1996). Accountability and Decentralisation in Government: An Incomplete Contracts Model. Eur. Econ. Rev. 40 (1), 61–89. doi:10.1016/0014-2921(95)00055-0

Seshadri, S. R., Parab, S., Kotte, S., Latha, N., and Subbiah, K. (2016). Decentralization and Decision Space in the Health Sector: a Case Study from Karnataka, India. Health Policy Plan. 31 (2), 171–181. doi:10.1093/heapol/czv034

Shugart, M. S., and Carey, J. M. (1992). Presidents and Assemblies: Constitutional Design and Electoral Dynamics. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/cbo9781139173988

Shvetsova, O., Adeel, A. B., Catalano, M., Catalano, O., Giannelli, F., Muftuoglu, E., et al. (2020a). Institutional Origins of Protective COVID-19 Policies Dataset V. 1.3. Binghamton University COVID-19 Policy Response Laboratory. Available at https://orb.binghamton.edu/working_paper_series/7/.

Shvetsova, O., Zhirnov, A., VanDusky-Allen, J., Adeel, A. B., Catalano, M., Catalano, O., et al. (2020b). Institutional Origins of Protective COVID-19 Public Health Policy Responses: Informational and Authority Redundancies and Policy Stringency. Pip 1 (4), 585–613. doi:10.1561/113.00000023

Singh, N. (2008). Decentralization and Public Delivery of Health Care Services in India. Health Aff. 27 (4), 991–1001.

Sparrow, R., Budiyati, S., Yumna, A., Warda, N., Suryahadi, A., and Bedi, A. S. (2017). Sub-national Health Care Financing Reforms in Indonesia. Health Policy Plan. 32 (1), 91–101. doi:10.1093/heapol/czw101

Strom, K. (2000). Delegation and Accountability in Parliamentary Democracies. Eur. J. Polit. Res 37 (3), 261–289. doi:10.1111/1475-6765.00513

Suryanto, S., Plummer, V., and Boyle, M. (2016). Financing Healthcare in Indonesia. Apjhm 11 (2), 33–38. doi:10.24083/apjhm.v11i2.185

Keywords: federalism, political institutions, public health, COVID-19, health institutions

Citation: Shvetsova O, VanDusky-Allen J, Zhirnov A, Adeel AB, Catalano M, Catalano O, Giannelli F, Muftuoglu E, Rosenberg D, Sezgin MH and Zhao T (2021) Federal Institutions and Strategic Policy Responses to COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Polit. Sci. 3:631363. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2021.631363

Received: 19 November 2020; Accepted: 31 May 2021;

Published: 22 June 2021.

Edited by:

Sandra León, Universidad Carlos III de Madrid, SpainReviewed by:

Eloisa Del Pino, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, SpainCopyright © 2021 Shvetsova, VanDusky-Allen, Zhirnov, Adeel, Catalano, Catalano, Giannelli, Muftuoglu, Rosenberg, Sezgin and Zhao. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Olga Shvetsova, c2h2ZXRzb0BiaW5naGF0bW9uLmVkdQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.