- Political Science Department, Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Brussels, Belgium

Refugee resettlement is implemented by many different national and international stakeholders who operate in different locations and on the basis of sometimes diverging objectives. The implementation of the resettlement process has thus been characterized as multi-level governance, with resettlement stakeholders coordinating and negotiating the selection of refugees for resettlement. Still, literature on the implementation of refugee resettlement has remained very limited and has mainly focused on one specific stakeholder or stage of the process. In addition, a common conceptualization of the different stages is currently missing in academic literature. To address this research gap, the article proposes a common terminology of all stages of the resettlement process. Highlighting the diversity of resettlement programs, the article relies on a comparative case study of the German resettlement and humanitarian admission programs from Jordan and Turkey. By drawing on the concept of multi-level governance, the article examines diverging objectives and interdependencies between resettlement stakeholders, such as UNHCR and resettlement countries. As a result, the article argues that the increasing emphasis on national selection criteria by resettlement countries, including Germany, puts resettlement countries even more in the center of decision-making authority–in contrast to a diffusion of power that characterizes multi-level governance.

Introduction

“We are moving people, not boxes” (interviewee from IOM Turkey, 2019).

Refugee resettlement is generally explained in one sentence: According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), it constitutes “the selection and transfer of refugees from a State in which they have sought protection to a third State which has agreed to admit them–as refugees–with permanent residence status” (UNHCR, 2011, p. 3). Behind this short definition, however, lies a process that is implemented by many different stakeholders, in various locations and over different periods of time. And despite the increase of resettlement countries and the diversification of resettlement programs since the early 2000s, literature on the implementation of resettlement programs has remained rather scarce (but see Garnier et al., 2018; Darrow 2015; Sandvik, 2011). In addition, published articles on resettlement mostly focus either on the role of one specific resettlement stakeholder (see for instance Garnier, 2014 on UNHCR’s strategy and policies on resettlement) or on one specific stage of the resettlement process (see for instance Darrow, 2015 on the street-level implementation of resettled refugees’ reception in the United States).

This article, in turn, considers all stages of the resettlement process from the point in time when refugees enter the process until they arrive in the resettlement country. Given that, to the best of the author’s knowledge, current literature does not provide a common conceptualization of the different stages of the resettlement process, the article provides an overview about the various stages and proposes a common conceptualization of the resettlement process that could be employed in future research.

To do so, the article firstly discusses different existing conceptualizations of the resettlement process as employed by two main resettlement stakeholders (i.e., UNHCR and the International Organization for Migration, IOM). Given that these conceptualizations predominantly focus on the specific responsibilities of the stakeholder who published the particular overview, this article instead proposes a conceptualization of the resettlement process that considers the responsibilities of all stakeholders involved in the process.

Introducing such a blueprint for analysis is especially relevant in regard to the diversification of refugee admission programs that can be observed since the early 2000s (Beirens and Fratzke, 2017). In Europe, for instance, many countries introduced new refugee admission programs in response to the ongoing Syrian civil war. Those programs are often not permanent resettlement programs under UNHCR auspices, but rather ad hoc humanitarian admission programs set up in response to specific humanitarian crises–like the Syrian civil war (ibid.)

As a result, programs differ for instance with regards to the stakeholders involved in the process, the eligibility for admission (e.g., some programs are only targeted towards Syrian nationals) and the residence status persons receive after admission. Despite those differences, refugee admission programs are mostly referred to as ‘resettlement’. ‘Resettlement’ is thus often used as an umbrella term for different refugee admission programs–despite the fact that many programs divert from UNHCR’s traditional definition of resettlement.

Applying the proposed conceptualization of the resettlement process to particular admission programs can thus highlight differences in the implementation of the programs (e.g., with regards to the stakeholders involved in the process)—but also show the similarities amongst different programs. To offer such an analysis, this article applies the proposed conceptualization to two specific programs: 1) Germany’s resettlement program in Jordan and 2) Germany’s humanitarian admission program in Turkey.

Germany was selected for the article’s case study given its comparatively large quota for resettlement and humanitarian admission: in 2019, Germany ranked fifth among resettlement countries. In addition, Germany also received the highest number of asylum seekers world-wide that year (UNHCR, 2020e). The country is thus an important destination for displaced persons in the world, including resettled refugees.

Germany has also played a major role in negotiating the EU-Turkey Statement that was signed in 2016 (Deutsche Welle, 2016). The EU-Turkey statement has been an attempt to reduce the number of refugees arriving in Europe from Turkey via the Aegean Sea. For this purpose, a 1:1 mechanism was developed, establishing that for every Syrian refugee Turkey would readmit from Greece after March 2016, one Syrian would be resettled from Turkey to an EU member state (Deutsche Welle, 2018). To realize the EU’s commitment to the 1:1 mechanism, the EU promised the Turkish government to admit up to 76,504 persons via resettlement and humanitarian admissions (Welfens and Bonjour, 2020).

As a result, the EU-Turkey Statement is predominantly shaping Germany’s current engagement in resettlement activities. Since 2016, the humanitarian admission program from Turkey is Germany’s largest admission program in terms of admitted persons with a monthly quota of 500 persons (BMI, 2018b). By contrast, Germany’s resettlement program from Jordan only resettled 363 refugees in the whole year of 2019 (UNHCR, 2020c).

Most refugees admitted to Germany are thus admitted through humanitarian admission instead of the permanent resettlement program. A closer analysis of the German humanitarian admission and resettlement programs can thus shed light on how different admission programs are employed by the same resettlement country and what this means for the rights that admitted persons enjoy in Germany.

Since 2015, a specific legal basis for the admission of resettled refugees exists in Germany, independent from the legal basis covering humanitarian admissions that was already established in the German residence act (Grote et al., 2016). The admission of resettled refugees is thus separated from other legal statuses that displaced persons can receive, such as refugee status under the Geneva Convention or subsidiary protection (Ibendahl, 2016). Nevertheless, resettled refugees and refugees recognized through the asylum procedure enjoy more or less the same rights in Germany (Grote et al., 2016).

Resettled refugees are allowed to work and entitled to social security benefits and they can apply for a permanent residence permit after three years of residence in Germany (Caritas, 2020b). Very importantly, the German resettlement program does not specify the nationality of refugees as an eligibility criterion. In contrast, the humanitarian admission program from Turkey is specifically targeted toward Syrian refugees (BMI, 2018b)1. In addition, the threshold to receive a permanent residence permit is higher for refugees admitted through the humanitarian admission program as they can only apply for a permanent residence permit after five years (Ibendahl, 2016).

Syrian refugees who are admitted under the humanitarian admission program also face higher restrictions for family reunification than resettled refugees, but they are allowed to work and entitled to social security benefits similar to refugees admitted through resettlement (Ibendahl, 2016). Thus, although there are many similarities between the two programs with regards to refugees’ rights in Germany, the German resettlement program provides refugees with a more secure perspective in Germany than the humanitarian admission program, which can be crucial for the concerned refugees.

Applying the article’s proposed conceptualization of the resettlement process to the case-study of the two German programs also sheds light on similarities and differences in the implementation of the two programs, for instance with regards to the stakeholders involved in the resettlement process.

Indeed, resettlement and humanitarian admission processes are implemented by many different stakeholders who need to constantly adapt to changing circumstances (e.g., with regards to fluctuating annual resettlement quota) and challenges. The article highlights those challenges and provides an in-depth analysis of how implementing stakeholders coordinate and negotiate the implementation of the two German programs.

To do so, the article draws on the concept of multi-level governance that stresses the diffusion of decision-making authority across stakeholders on subnational, national and supranational levels (Hooghe and Marks, 2001). Employing multi-level governance as a lens to study the German resettlement and humanitarian admission programs, the article focuses on the selection process of the two German programs. Thereby, it examines the responsibilities and (sometimes diverging) objectives of UNHCR and the German Federal Office for Migration and Refugees (German: Bundesamt für Migration und Flüchtlinge, BAMF) in selecting refugees for resettlement and humanitarian admission. In addition, the article also highlights interdependencies between both implementing stakeholders.

The article’s analysis is based on a literature review as well as 20 semi-structured in-depth key informant interviews with resettlement stakeholders, such as personnel from UNHCR, the European Asylum Support Office (EASO) and IOM. Key informant interviews were conducted in Jordan and Turkey between April and November 2019. In addition, the article relies on 16 semi-structured in-depth interviews with Syrian refugees who were resettled from Jordan and Turkey to Germany. The interviews took place in May 2019 (for the Turkey cohort) and December 2019 (for the Jordan cohort) and were conducted in the reception center in Friedland (Germany) where most resettled refugees spend their first two weeks after their arrival in Germany.

The article is structured as follows. First, it provides an overview about historical and current approaches toward resettlement by different resettlement stakeholders. The next section discusses existing overviews of the resettlement process before proposing a common conceptualization to analyze resettlement processes. It is followed by an overview about Germany’s resettlement and humanitarian admission programs in Jordan and Turkey and an application of the proposed conceptualization to the two German programs. The subsequent section introduces the concept of multi-level governance as a theoretical lens to study the stakeholders involved in the resettlement process. Finally, the last section examines the responsibilities and objectives of UNHCR and BAMF in the selection process (and beyond), as well as interdependencies and power relations between the two stakeholders.

Resettlement in History and Current Practice

This section will discuss historical and current approaches and developments in the field of refugee resettlement in general, before proposing a new conceptualization of the resettlement process.

Resettlement in History

As stated above, resettlement is defined by UNHCR as “the selection and transfer of refugees from a State in which they have sought protection to a third State which has agreed to admit them–as refugees–with permanent residence status” (UNHCR, 2011, 3). According to this definition, only persons who have received refugee status (and have consequently crossed an international border) can be resettled2. Once refugees are resettled, they will receive permanent residence status with the prospect of eventually becoming citizens of the resettlement country (UNHCR, 2011).

Resettlement is a voluntary act; no country is legally obliged to offer resettlement places. Instead, resettlement is traditionally considered as a tool for refugee protection as well as a tool for responsibility sharing amongst the international community (Beirens and Fratzke, 2017; Garnier et al., 2018a; Labman, 2019).

With regards to refugee protection, resettlement represents one of the three durable solutions–next to voluntary repatriation and local integration–that UNHCR foresees for resolving a refugee situation. In this regard, resettlement specifically offers a durable solution for vulnerable refugees “whose life, liberty, safety, health or other fundamental rights are at risk in the country where they have sought refuge” (UNHCR, 2011, 36). To be selected for resettlement, refugees must thus be identified as particularly vulnerable, for instance because they are survivors of torture or because they have medical needs that cannot be attended to in the host country. Resettlement is thus highly selective in its character and includes a resource intensive selection process by several stakeholders to identify and select particular vulnerable persons for resettlement.

This link of vulnerability and selectivity is also important with regards to the conceptualization of resettlement as a tool for responsibility sharing amongst the international community. Given that most refugees (first) flee to neighboring countries in close proximity to the conflict, the responsibility of refugee protection primarily lies on those host countries (UNHCR, 2020d)3. Other countries, which are further away from crisis-prone areas and thus receive a lower number of asylum seekers, can help to share responsibility for refugee protection by providing resettlement for particular vulnerable refugees from those neighboring countries.

Traditionally, resettlement countries4 were thus countries located far away from 20th century crises and which therefore did not experience a high number of spontaneous arrivals of asylum seekers in their territory. Being an ocean away from many humanitarian emergencies, the United States, Canada and Australia were thus at the forefront of resettlement activities throughout the last decades (Beirens and Fratzke, 2017). Together with New Zealand, the Netherlands and the Scandinavian countries, they represent the ‘traditional resettlement countries’, having included resettlement programs in their national legislation between 1975 and 1987 (Honoré, 2003). As stated above, those ‘traditional’ resettlement programs generally offer permanent residence status to the refugees concerned. Resettlement is therefore considered a permanent solution to displacement and resettled refugees are perceived as new citizens of their resettlement country. In addition, most of the “traditional resettlement countries” base their selection of refugees for resettlement primarily on UNHCR’s vulnerability criteria, instead of employing additional national selection criteria, such as refugees’ “integration potential,” as will be discussed in more detail below. Although resettlement can thus indeed provide a durable solution for individual vulnerable refugees, the conceptualization of resettlement as a tool for international solidarity and responsibility sharing is rather problematic.

To move beyond the benefits of resettlement for the individual refugees who are resettled, UNHCR introduced the concept of the “strategic use of resettlement” (SUR) in 2003. The SUR concept outlines that if resettlement is used in a strategic manner, it has the potential to create additional benefits such as positively impacting the protection conditions in the host country from where refugees are resettled (UNHCR, 2003). This proposition neatly ties into the idea of resettlement as a responsibility sharing tool by alleviating pressure on those host countries which receive a high number of displaced persons.

However, improving protection conditions in host countries would presuppose the resettlement of a considerable high number of refugees compared to the number of displaced persons residing in the host countries. Considering the vast gap between refugees’ resettlement needs and UNHCR’s annual submissions of cases to resettlement countries, this is clearly not the case. For instance, in 2019, global resettlement quotas only allowed for offering a resettlement place to one refugee out of 20 vulnerable refugees in need of resettlement (UNHCR, 2020d).

Given the vast discrepancy between the numbers of refugees in need of resettlement and the numbers of refugees who are actually resettled, resettlement can thus rarely make a difference in terms of responsibility sharing with host countries. In the case of Jordan for instance, resettlement has generally not been perceived by resettlement stakeholders as (positively) impacting the broader refugee protection landscape–even during a peak of resettlement numbers in 2016 (Durable Solutions Platform, 2020). Instead, resettlement from Jordan has mostly been a “drop in the ocean” (Durable Solutions Platform, 2020, 19) in terms of protection benefits in the host country.

Consequently, the idea of resettlement as a tool for responsibility sharing amongst the international community is arguably more rhetoric in nature than observable in practice. Indeed, it is important to keep in mind that this “traditional” view on resettlement–providing permanent residency for the most vulnerable refugees and sharing solidarity with host countries–is only an ideal. And although this ideal is upheld rhetorically by many governments of resettlement countries, it stands in contrast to the reality of resettlement program’s high selectivity and the vast gap between vulnerable refugees in need of resettlement and existing resettlement quotas.

Resettlement in Current Practices

Since the early 2000s, resettlement countries and programs have increasingly diversified. Despite some fluctuations, the number of countries offering resettlement places has increased considerably: from 2005 to 2019, the number of resettlement countries rose from 16 countries to 29 countries (Beirens and Fratzke, 2017; UNHCR, 2020d). Much of the new commitment to resettlement can be traced back to the beginning of the Syrian civil war in 2011 and–in the case of European countries–to the subsequent high rise in numbers of persons crossing the Mediterranean in search of asylum in 2015 and 2016. As a result, European countries make up a considerable share of the new resettlement countries (Beirens and Fratzke, 2017).

While some European countries introduced permanent resettlement programs, many opted for ad hoc and non-permanent humanitarian admission programs instead (Beirens and Fratzke, 2017). Those humanitarian admission programs are set up as an immediate response to a specific current humanitarian crisis. Consequently, they target specific groups of refugees from specific host countries in specific periods of time.

Very importantly, humanitarian admission programs are generally perceived by resettlement countries as a tool for temporary instead of long-term protection. In line with the conception that these programs enable the admission from “hot conflict” (Grote et al., 2016, 6), the idea is that refugees should return to their home countries as soon as return is deemed to be safe again. Consequently, humanitarian admission programs generally do not immediately provide permanent residence for the admitted refugees (European Migration Network, 2016; Beirens and Fratzke, 2017)—an aspect that contradicts the “traditional view” on resettlement as well as UNHCR’s definition.

However, this contradiction might be blurred in reality if the “hot conflicts” in refugees’ home countries remain unsolved in the long term. Given that it is often not safe for refugees to return to their home countries for (more than) decades, many refugees who were admitted through humanitarian admission programs will eventually receive permanent residence in their resettlement country. Thus, although humanitarian admission programs might initially not be set up for permanent residence of the admitted refugees, the reality for the admitted persons is likely to be different depending on how the situation in their home country develops. Still, the recent developments in Denmark, which has denied at least 189 Syrian the renewal of temporary residence permits since 2020 on the basis that the Danish government deems parts of Syrian to be safe to return to, highlights the fragility of temporary resident permits for the concerned refugees (The Guardian, 2021).

With the diversification of resettlement countries and programs, the motivations for countries to offer resettlement places are also diversifying. Many resettlement countries indeed still stress refugee protection and international responsibility sharing as their motivation to offer resettlement places. However, the idea of resettlement as an alternative to the “spontaneous” arrivals of asylum seekers is increasingly cited as an incentive to engage in resettlement activities (Beirens and Fratzke, 2017; van Selm, 2018). For instance, the former EU Commissioner for Home Affairs Dimitris Avramopoulos made references to the idea that resettlement would reduce the incentives for irregular migration to Europe when proposing the EU Commission’s proposal for an EU resettlement scheme (Beirens and Fratzke, 2017).

In addition, many resettlement countries, including some of the “traditional resettlement countries,” are opting for national selection criteria in addition to vulnerability considerations. Those national selection criteria generally consider refugees’ potential to successfully integrate in the resettlement country which may be determined for instance through refugees’ prior education and work experience (Westerby, 2020). Resettlement thus may become a tool for migration management, where resettlement countries select (a few) refugees they deem suitable to enter the country while increasingly closing off their borders for asylum seekers (Hashimoto, 2018; Welfens, 2018). Thus, resettlement countries’ rationales for offering resettlement places can deviate considerably from the “traditional” objective of resettlement as a tool for the (additional) protection of displaced persons and international responsibility sharing.

Despite the vast differences in motivations to offer resettlement places, linking resettlement activities with any intended broader impacts may be problematic. As stated above, it is very difficult to attribute positive impacts on the overall protection landscape in host countries to resettlement when resettlement quotas are considerably lower than resettlement needs. On the other hand, linking the treatment of asylum seekers and the engagement in resettlement activities may also be difficult for resettlement countries to achieve in practice: just because a country is offering (a few) resettlement places does not lead to the fact that displaced persons will be discouraged to seek asylum at its borders.

However, resettlement may be used by governments as an “excuse” to limit access to asylum and to frame asylum seekers as illegally crossing borders and seeking asylum. For instance, Labman (2019) outlines how the discourse in Canada on resettlement and asylum has been interlinked to curtail spontaneous arrivals of asylum seekers. Citing a UNHCR resettlement officer in Canada, she points out that “resettled refugees were presented as part of the refugees using the ‘front door.’ And by providing refugees greater access, Canada suggested it had the moral authority to limit access to those refugees described as using the ‘back door’” (Labman, 2019, 45).

Consequently, there are many different reasons, which may overlap and/or stand in opposition to each other, to offer resettlement places which manifest in an array of policies and programs. To address this diversity of programs, Welfens et al. (2019) introduced the concept of “Active Refugee Admission Policies” (ARAP). This concept comprises the full range of admission programs for persons in need of protection, including but not limited to resettlement. As such, it provides an umbrella term for all admission pathways with a humanitarian scope, such as resettlement, humanitarian admission and private sponsorship but also other complementary pathways for the purpose of education (e.g., student visas), work and family reunification. Those programs might have different goals, different admission processes and diverging eligibility criteria. They may also differ with regards to the stakeholders involved in the process. For instance, civil society actors are more involved in private sponsorship programs than “traditional” resettlement. Nevertheless, ARAPs all have in common that they aim to offer “people in need of protection safe and orderly access to a destination country” (Welfens et al., 2019).

Consequently, the scope of ARAPs is much broader than resettlement and humanitarian admission programs that are discussed in this article. However, it highlights the commonalities between the different programs and serves as a good reminder to (also) seek out similarities instead of only highlighting differences between admission programs. Thus, although this section outlined differences within the realm of resettlement and humanitarian admission programs, the overarching principle of providing safe legal pathways for people in need of protection remains the same for all the programs.

After discussing resettlement–and humanitarian admission–programs in history and current practices, the following section will propose a common conceptualization of the resettlement process while unpacking the different stages of the process.

Towards a New Conceptualization of the Resettlement Process

Resettling refugees includes many different decisions and actions. Where and how the process starts and finishes exactly can be debated: on the one hand, it can be argued that the resettlement process starts with a resettlement country government’s decision to offer resettlement places and finishes with the resettled refugees’ reception and first steps toward integration in the resettlement country. On the other hand, it is also possible to view the process in a wider perspective, since the implementation of the resettlement process is imbedded in the ongoing policy cycle of agenda setting, policy formulation, adoption, implementation and evaluation (Hill and Varone, 2014). Given that this article focuses on the organization and implementation of the resettlement process (i.e., on the operational level), the former perspective will be adopted here.

The stages of the resettlement process involve different stakeholders, different locations and varying periods of time. They also might overlap, be reversed in order, revised or excluded in their entirety for the same program. Moreover, the stages might be different for any resettlement country, host country and/or program. Still, the different actions that stakeholders take in the process can generally be aggregated into several distinct stages that build on one another.

To the best of the author’s knowledge, there does neither exist a common breakdown of the different stages of the resettlement process nor a common conceptualization of the resettlement process in current academic literature. Instead, the few authors who have focused on the implementation of the resettlement process have generally zoomed in on one of the stages of the resettlement process. For instance, Darrow (2015) analyses how the reception of resettled refugees’ is implemented in the United States and Sandvik (2011) details the procedure adopted by UNHCR to screen and select refugees for resettlement.

Nevertheless, main resettlement stakeholders such as UNHCR and IOM indeed provide general overviews of the resettlement process. For instance, UNHCR published a flow chart in addition to its detailed elaborations in the UNHCR Resettlement Handbook (UNHCR, 2021b). This flow chart meticulously describes the steps to be taken by different UNHCR staff and offices, starting with case identification and ending with the resettlement departure and closing the case. It also describes the responsibilities of other actors in the process, in particular the tasks of the resettlement country (RST country) involved in the resettlement case, such as accepting or rejecting the case.

Consequently, the UNHCR flow chart does indeed provide a very detailed overview about the different steps that need to be taken to facilitate the resettlement process. As a result, however, the employed flow chart takes up the space of two entire pages without grouping the different tasks into overarching themes and/or stages (e.g., highlighting which tasks make up the selection of refugees for resettlement). This choice of visualization renders the UNHCR flow chart rather inadequate for applying the outlined process to different resettlement programs.

IOM also includes a flow chart of the resettlement process in the annex of its 2020 report on IOM’s engagement in resettlement activities (IOM, 2020). This overview groups IOM’s responsibilities according to the different stages of the resettlement process. However, this flow chart only provides an overview about IOM’s responsibilities without making references to other stakeholders’ responsibilities in the process.

Consequently, while the two flow charts provide a generalized overview about the resettlement process that can be applied to different resettlement countries and resettlement programs, they are either very detailed and somewhat unstructured (i.e., UNHCR flow chart) or only include the responsibilities of one stakeholder in the process, as is the case with the IOM overview.

Indeed, while both flow charts provide great insights into the particular perspectives and responsibilities of the resettlement stakeholder who is authoring the publication, they remain (to varying degrees) superficial in terms of other stakeholders’ responsibilities. Consequently, a less actor-centric general overview about the resettlement process is needed in order to easily compare and contrast different resettlement programs.

This article proposes such a new conceptualization of the resettlement process, which can be applied and adapted to different resettlement countries and programs. Incorporating different aspects of the two outlined resettlement flow charts, it also synthesizes information from the various resettlement programs outlined in the 24 individual country chapters published together with the UNHCR Resettlement Handbook (UNHCR, 2018a).

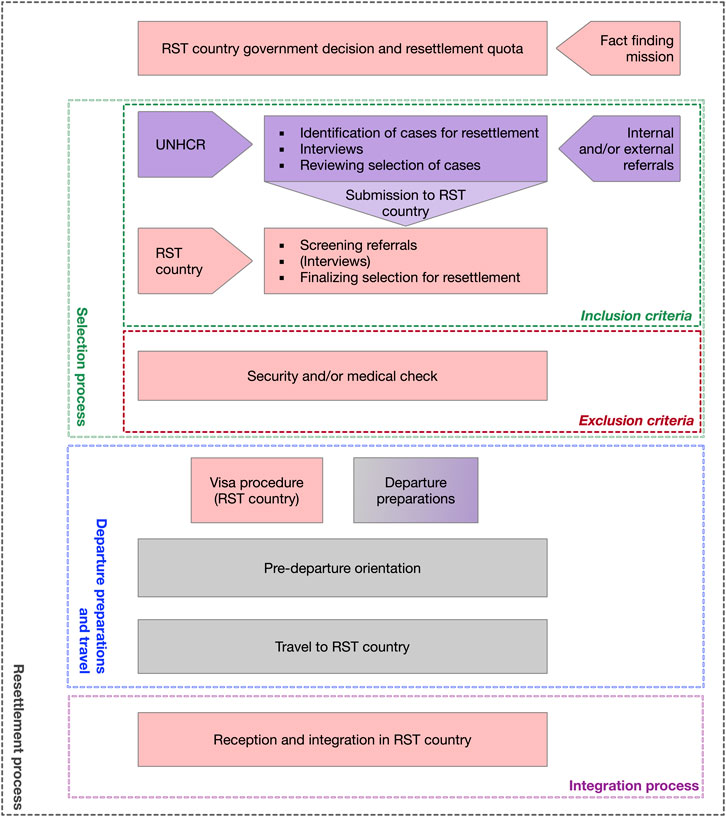

The article thus proposes the following conceptualization of the different stages of the resettlement process, as visualized in Figure 1.

The Resettlement Process

The “resettlement process” describes the entire implementation process, starting with the resettlement country government’s decision on resettlement programs and its resettlement quota. This decision might precede fact finding missions of representatives of the resettlement country to the host country to consult with the host country’s government and other key partners (Grote, Bitterwolf, and Baraulina, 2016). As stated above, for this article’s conceptualization, the resettlement process ends with the resettled refugees’ reception and integration in the resettlement country. The resettlement process thus incorporates the following stages: the selection process, the departure preparations and travel to the resettlement country, and the integration process.

The Selection Process

The “selection process” concerns the selection of refugees for resettlement by various stakeholders. It starts with the identification of cases for resettlement by UNHCR, which might be a result of internal referrals (i.e., from other UNHCR units such as the protection unit) or external referrals, for instance from NGOs working with the refugee population. Following case identification, UNHCR conducts resettlement interviews, reviews the selection of cases and submits the selection of cases to the respective resettlement country (UNHCR, 2011). The resettlement country is then responsible to screen the referrals and to finalize the selection of refugees for resettlement. To do so, most resettlement countries generally rely on selection missions to locally conduct a second interview with the pre-selected refugees. However, many resettlement countries also offer dossier selection, meaning that they base their selection entirely on UNHCR’s pre-selection without conducting an additional interview (UNHCR, 2018a).

Dossier selection is often reserved for urgent cases that require an accelerated resettlement process. The country chapter for Canada, for instance, establishes that “in emergency cases where an urgent protection need has been identified, it may be possible to waive the usual requirement for an interview and biometrics” (UNHCR, 2018b, 7). An exception is Chile, where dossier selection is not linked to emergency cases but to the number of cases submitted from the same host country. As such, in cases where less than ten dossiers are submitted from the same host country, Chile relies on dossier selection. If the number of dossiers submitted from one host country exceeds ten dossiers, Chile employs selection missions to conduct interviews with the pre-selected refugees (UNHCR, 2002).

This part of the selection process is based on “inclusion criteria,” such as vulnerability and other selection criteria. In addition to inclusion criteria and as a second stage of the selection process, many resettlement countries also conduct security and medical checks. Resettlement countries do not always conduct those checks themselves: many resettlement countries for instance employ IOM for carrying out medical examinations (UNHCR, 2018a; IOM, 2020).

In contrast to the prior selection based on “inclusion criteria,” refugees are screened during security and medical on the basis of “exclusion criteria,” such as safety concerns and contagious diseases. Consequently, these checks could lead–in the worst-case scenario–to the exclusion of already selected refugees (UNHCR, 2011; IOM, 2020).

Departure Preparations and Travel

After refugees are selected for resettlement, their departure needs to be prepared. This stage generally includes several stakeholders: while visa procedures are normally in the hands of the resettlement country, other departure preparations are often implemented by UNHCR and IOM. Those departure preparations include logistical preparations, such as organizing exit permits and flight scheduling, and in many cases also pre-departure orientations which aim to prepare refugees mentally for their resettlement (IOM, 2020).

The Integration Process

The “integration process” refers to the reception and integration of resettled refugees in the resettlement country. This process can differ substantively amongst resettlement countries and programs. With regards to housing, for instance, some countries, such as Norway and Sweden, provide resettled refugees with individual accommodation as soon as they arrive in their resettlement country. In other countries, resettled refugees need to stay in reception centers before they can move into individual housing (European Migration Network, 2016).

The integration process and refugees’ experiences in their host countries can thus differ considerably depending on specific resettlement countries and programs. The same can be said (to varying degrees) for the other stages of the resettlement process.

It is also important to note that every resettlement process can be delayed or cancelled for any case at any time and stage. Delays and cancellations can both happen for a variety of reasons, ranging from the host government denying exit permits for the selected refugees to the current COVID-19 pandemic. But it is also possible that refugees decide to reject their resettlement offer and to drop out of the process at some stage (interviewees from UNHCR Jordan and UNHCR Turkey 2019).

Still, all resettlement programs by necessity follow the structure of a selection process, departure preparations and travel, and integration process. The article’s conceptualization of the resettlement process into three (overlapping) stages therefore aims to offer a concise overview about the whole resettlement process and to provide a blueprint for comparing different programs.

The following sections will provide such a comparison for Germany’s resettlement and humanitarian admission programs in Jordan and Turkey. Firstly, the next section discusses Germany’s historic engagement in resettlement activities as well as the current German resettlement and humanitarian admission programs in Jordan and Turkey. Secondly, the article applies the proposed conceptualization of the resettlement process to the two German programs in order to highlight similarities and differences in the programs’ implementation.

Germany’s Resettlement and Humanitarian Admission Programs in Jordan and Turkey

Germany has a long tradition of resettling refugees dating back to the early 1950s (European Migration Network, 2016). Implementing humanitarian admission programs since 1956, Germany has first resettled refugees rather sporadically before committing to humanitarian admission on a more regular basis since the 1990s (Grote et al., 2016). For instance, between 1990 and 1999, Germany admitted approximately 3,000 refugees from Albania, almost 350,000 war refugees from Bosnia and approximately 15,000 war refugees from Kosovo as part of a human admission program. More recently, approximately 20,000 Syrian refugees were admitted to Germany from countries neighboring Syria as well as from Egypt and Libya between 2013 and 2016 (ibid.).

In 2012, Germany then moved from only employing ad-hoc humanitarian admission programs to also offering a permanent resettlement program (Baraulina and Bitterwolf, 2018). Since then, Germany’s annual resettlement quota has fluctuated from 300 persons in 2012 to 2,900 persons in 2019 (Grote et al., 2016; BMI, 2018a). Since the establishment of the permanent resettlement program, resettlement to Germany took place from a variety of host countries–some recurrent, some not–such as Tunisia, Indonesia, Sudan, Jordan, Lebanon, Egypt, and Ethiopia (ibid.).

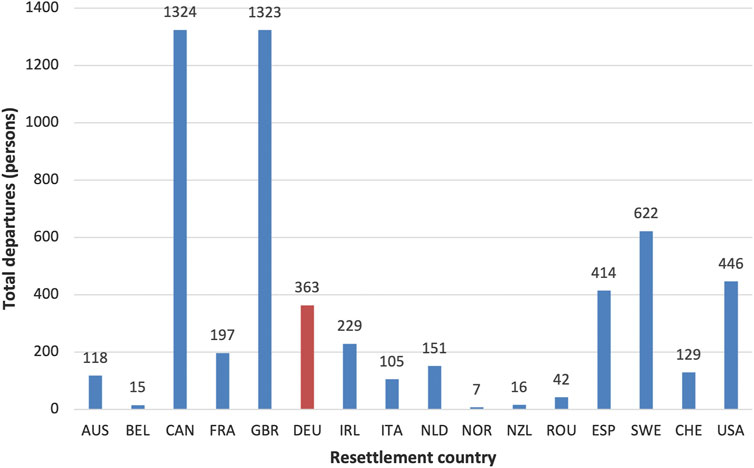

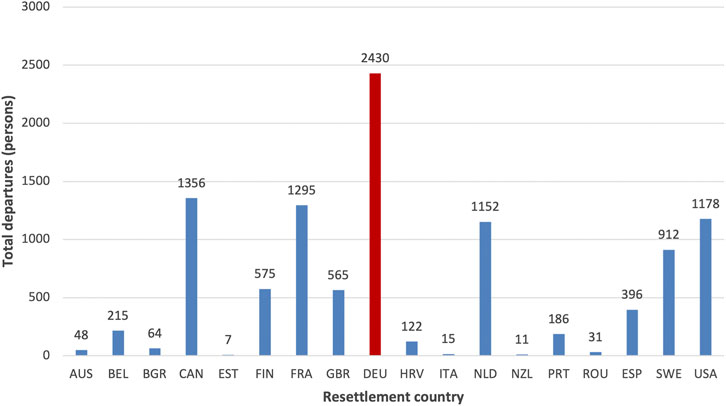

In the case of Jordan, Germany has just begun to restart resettlement in 2019 after halting the resettlement program for the last years. In 2019, 363 refugees were resettled from Jordan to Germany and in total, 5501 refugees were resettled from Jordan to 16 different resettlement countries (UNHCR, 2020c), as can be seen in Figure 2. This makes Jordan one of the largest UNHCR resettlement operations worldwide, ranking third behind Turkey and Lebanon (UNHCR, 2020b).

FIGURE 2. Resettlement departures from Jordan in 2019. Source: UNHCR (2020b).

The large majority of refugees who were resettled from Jordan to Germany in 2019 were Syrians. Still, the German resettlement program is also targeted towards refugees with other nationalities and in 2019, 32 refugees from Iraq and 18 refugees from Sudan were resettled from Jordan to Germany (UNHCR, 2020c).

In addition to the permanent resettlement program, Germany has also employed several non-permanent humanitarian admission programs (Grote et al., 2016). As stated above, since 2016, most refugees have been admitted to Germany through the humanitarian admission program from Turkey, with a monthly quota of 500 persons (BMI, 2018b).

Turkey is the world’s largest refugee hosting country as well as the largest resettlement operation which organized the departure of in total 10,558 persons in 2019 (UNHCR, 2020b). With regards to departures to Germany, 2,430 persons were admitted from Turkey to Germany through the humanitarian admission program in 2019 (UNHCR, 2020c), as visualized in Figure 3.

FIGURE 3. Resettlement departures from Turkey in 2019. Source: UNHCR (2020b).

As outlined in the introduction, the two programs differ to some degree with regards to eligibility and the admitted refugees’ rights in Germany. As such, refugees who are resettled to Germany through the permanent resettlement program receive an initial residence permit for three years on the legal basis of section 23 (IV) of the German Residence Act. After three years, the permit can be changed into a permanent residence permit (Caritas, 2020b).

In contrast, the German humanitarian admission program admits Syrian refugees on the basis of section 23 (II)—instead of 23 (IV)—of the German Residence Act. Admitted persons receive an initial residence permit for two or three years, depending on the year of their arrival in Germany (Caritas, 2020a). After five years of residence in Germany, they then can apply for a settlement permit if they meet certain requirements, such as a secure livelihood and sufficient knowledge of the German language (Art. 26 (4), German Residence Act). Syrian refugees who are admitted under the humanitarian admission program also face higher restrictions for family reunification than resettled refugees, but they are allowed to work and entitled to social security benefits similar to refugees admitted through resettlement (Ibendahl, 2016).

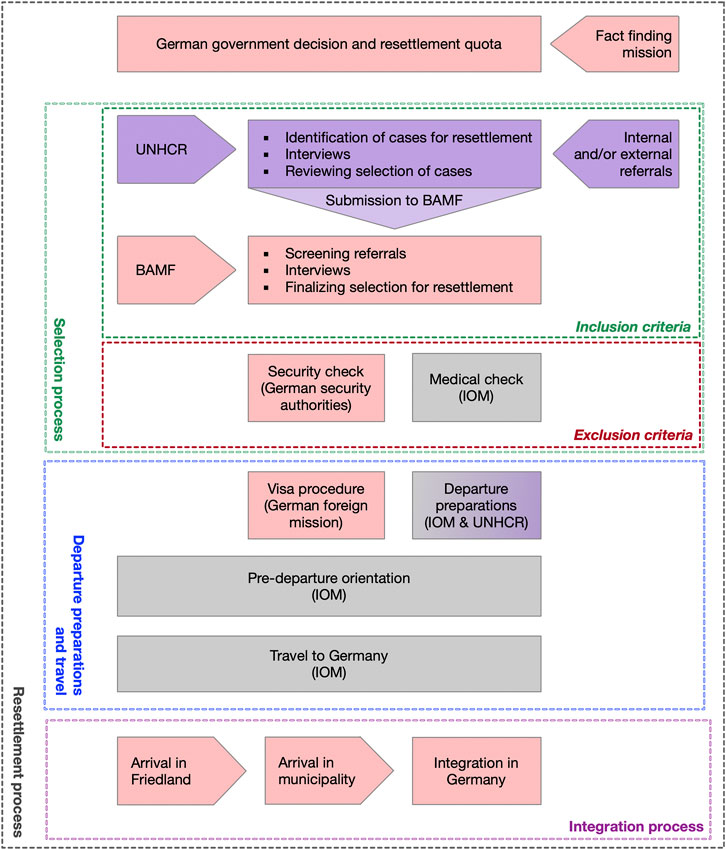

In addition to differences in eligibility and refugees’ rights in Germany, the implementation of the resettlement process also differs to some degree for the two programs. To illustrate those differences, the article applies the proposed conceptualization of the resettlement process to the two German programs, starting with the resettlement process from Jordan to Germany. The following flow chart in Figure 4 which is based on the author’s own fieldwork insights as well the German country chapter of the UNHCR Resettlement Handbook (UNHCR, 2018c) thus highlights how the outlined conceptualization can be adapted to a specific resettlement program.

As shown in the flow chart, the selection process of the German resettlement program from Jordan includes the identification and selection of refugees for resettlement by UNHCR and BAMF.

BAMF is a German federal agency under the responsibility of the Federal Ministry of the Interior (BAMF, 2020). It represents Germany’s central migration authority with many different areas of responsibilities related to asylum, integration and migration to Germany. With regards to resettlement and humanitarian admission, BAMF is responsible for organizing and implementing the German programs. As such, it has both a coordinating role to ensure the smooth cooperation between the different stakeholders as well as an implementing and decision-making role, especially with regards to the selection of refugees.

Germany does not allow for dossier submissions, which means that pre-selected refugees are interviewed through selection missions by BAMF personnel in addition to the UNHCR interview. Germany also employs security and medical checks for finalizing the selection of cases (UNHCR, 2018c). Security checks are carried out by German security authorities, while the medical check is conducted by IOM personnel (ibid.). Once the selection is finalized, the German foreign mission handles the visa procedure and UNHCR and IOM carry out other departure preparations. IOM is also contracted by the German authorities to conduct a pre-departure orientation for all selected refugees prior to their travel to Germany (ibid.).

After their travel to Germany, which is also organized by IOM, resettled refugees (except for critically ill persons and unaccompanied minors) stay in a reception center in Friedland. After two weeks in Friedland, they are distributed amongst the different federal Länder according to the “Königstein Key” (Grote et al., 2016)5. The federal Länder then further assign the resettled refugees to the different municipalities who are responsible for the refugees’ reception. Given that the reception of refugees falls into the competence of the federal Länder, the reception in the municipalities may vary widely depending on the specific federal Land (Grote et al., 2016; Caritas, 2020a).

Consequently, while the selection process, the departure preparations and travel to Germany are more or less the same for the different resettlement cases and fall into the responsibility of a few main stakeholders, the reception and integration process is implemented by many different stakeholders, including local immigration authorities and municipalities, and may look very different depending on the federal Land.

With regards to the main stakeholders in the process, the flowchart displays that UNHCR and BAMF play a major role for selecting refugees for resettlement from Jordan to Germany. The flow chart also shows that, while cases might be referred internally from other UNHCR units or externally by NGOs, the Jordanian government is not involved in the selection process.

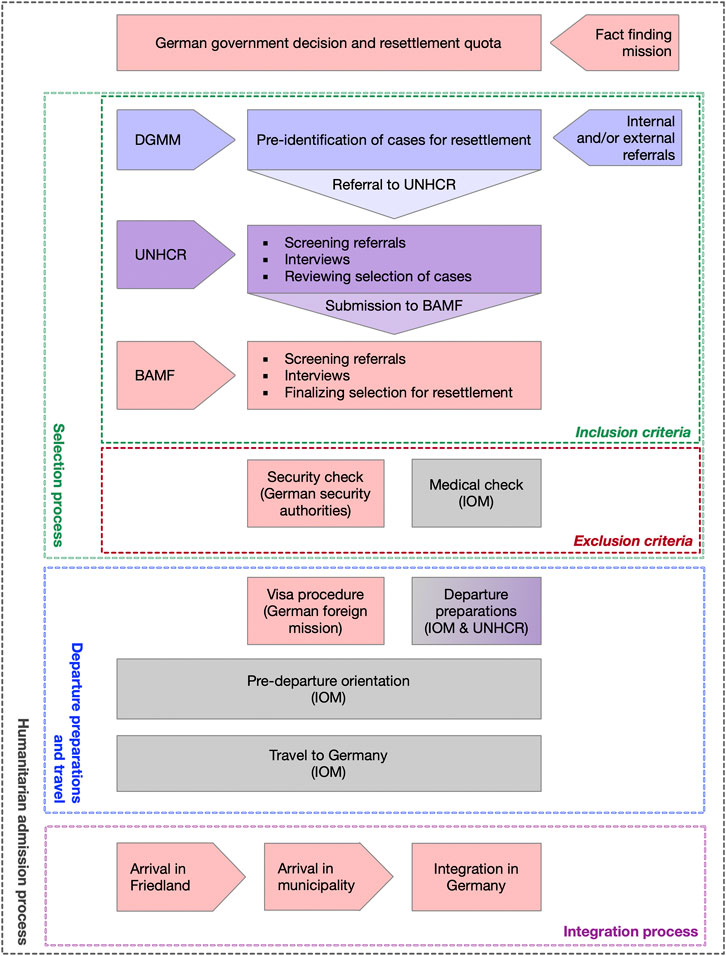

This is different for the German humanitarian admission program from Turkey where the host country government is involved in the selection and referral of refugees for resettlement considerations. In particular, the Turkish migration authorities called Directorate General of Migration Management (DGMM) pre-identifies cases for resettlement amongst Syrian refugees registered in Turkey and refers those cases to UNHCR. UNHCR then follows up with the referred cases as outlined above (interviewees from UNHCR Turkey 2019, and EASO 2019). The humanitarian admission process from Turkey to Germany thus includes an additional stakeholder and stage in the selection process, as illustrated in the following flow chart in Figure 5.

Although the outlined humanitarian admission process includes an additional stage and stakeholder in the selection process, this does not necessarily mean that the process takes longer than the resettlement process from Jordan to Germany. In fact, refugees who were resettled either from Jordan or Turkey and were interviewed by the author during their stay in Friedland, reported no significant differences in the duration of ‘their’ resettlement process. Most refugees who were resettled from Jordan indicated that their resettlement process took around five to nine months (there was one family whose resettlement process took almost two years, but this was an exception amongst the interviewees). For refugees admitted from Turkey, the process tended to be only slightly longer, ranging from approximately six months to one year.

After providing an overview about the German resettlement and humanitarian admission processes and their implementation, the following sections will analyze the responsibilities, objectives and interdependencies of UNHCR and BAMF as the two main stakeholders responsible for the selection of refugees in both programs.

To do so, the next section will firstly introduce the concept of multi-level governance as a theoretical lens to analyze the interactions and interdependencies of stakeholders in the resettlement process.

The Multi-Level Governance of Refugee Resettlement

The concept of multi-level governance (MLG) stresses the diffusion of authority and decision-making competences amongst actors across subnational, national and supranational levels of governance (Hooghe and Marks, 2001). Traditionally, the concept was employed to capture changes in decision-making competencies due to European integration (Hooghe and Marks, 2001). As such, multi-level governance stresses the shift from nation states as sole decision-makers in the European Union to a new system of governance that incorporates state and non-state actors on subnational, national and supranational levels (ibid.). However, the concept has also been employed for studies that are not primarily concerned with EU-state relationships (see for instance Betsill and Bulkeley, 2006; Hepburn and Zapata-Barrero, 2014).

Moving beyond European studies, authors have examined how decision-making and implementation of national policies is moved upwards (to EU and/or international organizations), downwards (for instance to local authorities), and outwards (for instance to civil society). Hereby, the interactions of actors responsible for decision-making and implementation merit special attention, since “a minimal degree of bargaining and negotiation among all of the involved institutions and actors should take place before one can speak of MLG” (Adam and Caponio, 2019, 27). Such interactions can take place horizontally between actors on the same level of governance (e.g., between public and private actors). In addition, interactions can also take place between different levels of governance (e.g., between a national government and an international organization). These interactions are defined as vertical relations (Zapata-Barrero and Barker, 2014).

Scholars have also analyzed the nature of those interactions. For instance, Lavenex (2015) discusses three different types of relationships between international organizations (IOs) and the EU in relation to EU external migration policies, where international organizations can either act as agenda-setters, rule transmitters or subcontractors for EU institutions.

Thereby, the notion of IOs as agender-setters is linked to the idea that IOs act as counterweights vis-à-vis EU actors, whereby IOs “seek to complement and correct EU policies where they perceive deficiencies with respect to their own migration policy mandate” (Lavenex, 2015, 2). For instance, Lavenex (2015) explains how UNHCR, as the guardian of the principles agreed in the 1951 Geneva Refugee Convention, seeks to bring human rights aspects of asylum legislation (back) into EU policy making.

IOs can also act as rule transmitters for EU institutions. In this case, IOs are not directly involved in the implementation of EU policies, but nevertheless add to the EU’s ambitions and goals in relation to third countries. As such, the author argues that UNHCR’s involvement in refugee status determination in countries neighboring the EU which do not employ a national asylum procedure is “conducive to the EU’s ambitions to develop asylum systems in surrounding countries” (Lavenex, 2015, 13).

Lastly, the conceptualization of IOs as subcontractors for EU institutions refers to the outsourcing of EU projects’ implementation to those institutions. Indeed, IOs such as UNHCR and IOM have become important actors in implementing programs in the realm of EU external migration policies and accordingly, the EU has become an important source of funding for IOs (Lavenex, 2015).

In a nutshell, MLG can thus be characterized as the diffusion of power amongst different stakeholders on different levels of governance. It is important to note that “stakeholders” are defined in this article as the different organizations (e.g., UNHCR and BAMF) responsible for the implementation of the resettlement process. Consequently, the article examines the interactions of stakeholders on the organization level instead of the individual level.

Indeed, refugee resettlement is–and always has been–inherently multi-level governance (Garnier et al., 2018). From a resettlement country’s perspective, the pre-selection of refugees takes place outside the national realm by UNHCR and/or host country governments, the final selection and admission is granted by resettlement country governments on the national level and settlement and integration takes place on the local level within the resettlement country. Resettlement thus involves many different stakeholders at the international, national and local level, including international organizations, national ministries, and civil society organizations. These stakeholders cooperate and bargain with each other according to their objectives in the resettlement process.

Such objectives depend on the stakeholders’ specific responsibilities within the resettlement process. Consequently, the same stakeholder might have different objectives in different implementation stages. It is important to note here that the article is not concerned with the overarching rationale of stakeholders to engage in resettlement activities in the first place6. Instead, the article focuses on the different responsibilities and objectives of stakeholders throughout the implementation of the resettlement process. By doing so, the article will shed light on interdependencies of implementing stakeholders and how they coordinate and negotiate the resettlement process.

As stated above, the focus will be on UNHCR and BAMF as two main stakeholders engaged in the selection of refugees for resettlement and humanitarian admission to Germany. By examining both stakeholders’ responsibilities and (sometimes diverging) objectives in the selection process, the article will shed light on UNHCR’s and BAMF’s interdependencies in the selection process and beyond.

UNHCR’s and BAMF’s Responsibilities in the Resettlement Process

“Every actor involved in resettlement efforts–including different ministries and executive agencies, as well as local authorities and nonprofit organization–has its own goals” (Beirens and Fratzke, 2017, 10)

As discussed above, UNHCR and BAMF select refugees for resettlement based on inclusion criteria. In addition, both stakeholders are involved (to a varying degree) throughout the whole process. Therefore, this section outlines the responsibilities and objectives of UNHCR and BAMF in the selection process and beyond.

UNHCR

The schematic overviews illustrate that UNHCR is either the first, in the case of resettlement from Jordan, or the second, in the case of humanitarian admission from Turkey, stakeholder to review cases and to select refugees for resettlement. UNHCR does so based on “rule-based, vulnerability-focused resettlement criteria” (Garnier, 2016, 66) which are outlined in the UNHCR resettlement handbook as submission categories (UNHCR, 2011). In order to be considered for resettlement, refugees must meet the requirements of at least one of the submission categories. The categories are legal and/or physical protection needs (such as a threat for arbitrary arrest in the host country), survivors of violence and/or torture, medical needs, women and girls at risk, family reunification (in order to reunite with family in a resettlement country), children and adolescents at risk and a lack of foreseeable alternative durable solutions. The last category refers to situations where both voluntary repatriation to the home country as well as local integration in the host country is not deemed possible for the refugees in question (ibid.).

In a nutshell, UNHCR’s submission categories are based on refugees’ vulnerabilities and protection risks in the host country and do not take refugees’ prospects to integrate in a specific resettlement country into account (Westerby, 2020). Based on these submission categories, UNHCR field-offices in host countries pre-select refugees for resettlement. The process to do so is also outlined in the UNHCR resettlement handbook. As stated above, it includes inter alia external and internal referrals and general case identification, the conduct of the resettlement interview, the preparation of a resettlement registration form for every case, and the review process for the selected cases (UNHCR, 2011)7.

As a next step, UNHCR identifies suitable resettlement countries and submits the selected cases to the identified resettlement country. The identification of a suitable resettlement country is easier said than done and is based on a whole variety of factors. These include for instance family links to the resettlement country, the annual quota of resettlement countries as well as the resettlement countries own selection criteria and admission priorities (ibid.).

Resettlement countries’ selection criteria are additional to UNHCR’s submission categories based on vulnerability and can be divided into “program-level criteria” and “non-Convention criteria” (Westerby, 2020). As such, program-level criteria are based on the resettlement country’s available resources to admit and host refugees. For instance, many resettlement countries have problems to find suitable accommodation for large families and therefore do not accept those families. This can become a problem for UNHCR (and most of all for the affected refugees), since large families are often the most vulnerable refugees and in urgent need of resettlement (interviewee from UNHCR Jordan 2019). Resettlement countries also generally pose a quota for medical cases (i.e., refugees with severe medical needs) that UNHCR needs to take into account for its referrals.

Besides program-level criteria, some resettlement countries also employ other national selection criteria. Those “non-Convention criteria” are not anchored in international refugee law. Instead, they are often related to refugees’ individual “integration potential” in the resettlement country and may include refugees’ education and work experience as well as the refugees’ religious beliefs (Westerby, 2020). Timing also plays a role: for instance, some resettlement countries might meet their annual quota earlier in the year, thus reducing the options for UNHCR to match refugees with suitable resettlement countries for the rest of the year (interviewee from UNHCR Jordan 2019).

Once suitable resettlement countries are determined and the dossiers are submitted, UNHCR is still responsible for counseling refugees throughout the remaining process. Thereby, one of UNHCR’s main roles is to manage refugees’ expectations about resettlement (UNHCR, 2011). Given that resettlement often represents the only durable solution for refugees, it is a highly sought-after opportunity amongst refugee populations which may lead to unrealistic expectations with regards to resettlement. UNHCR’s role is thus to counsel refugees throughout the process and to provide them with information on “the limits and possibilities of resettlement” (UNHCR, 2011, 142). UNHCR also follows up with their cases (e.g., registering new-born babies) and coordinates the admission process (e.g., with regards to departure preparations) with the other stakeholders. As such, refugees remain under the mandate of UNHCR until they depart to their resettlement country. Once they arrive at their destination, the resettlement country takes over the responsibility for the integration of the resettled refugees (Sandvik, 2011).

BAMF

Once UNHCR has identified Germany as a suitable resettlement country and has submitted the dossiers to BAMF for follow-up, BAMF screens the dossiers and invites suitable refugees for an interview. As outlined above, this is at least the second interview (and not the last one) that refugees go through in order to be selected for resettlement. The selection process can thus be described as a “duplicative process whereby refugees are often doubly screened for credibility and resettlement eligibility” (Labman, 2019, 60).

To conduct the interviews, selection teams deployed by BAMF normally travel to the host country and carry out the interviews locally. As outlined in the Germany country chapter of the UNHCR resettlement handbook, these interviews serve to “verify information provided in the dossiers, to double check and if necessary update personal data, to assess school and occupational qualifications and to determine personal needs” (UNHCR, 2018c, 6).

The BAMF interviews are also used to select refugees based on Germany’s national selection criteria. These criteria include the preservation of family unity, family or other ties in Germany conducive to integration, the need for protection and the ability to become integrated in Germany. For the last criterion, the level of school and occupational training, work experience, language skills and a young age are considered as indicators for refugees’ “integration potential” (UNHCR, 2018c).

The Germany country chapter also outlines the German quota for medical cases, which is five percent for resettlement (e.g., from Jordan) and three percent for humanitarian admissions. Germany thus employs both ‘program-level criteria’ and ‘non-Convention criteria’ as discussed above.

After finalizing the case selection, BAMF hands over the cases to the German security authorities who conduct an additional security check followed by the final decision on the admission of the cases by BAMF. If the decision is positive, the German foreign mission abroad handles the visa procedure and BAMF instructs IOM to organize the travel of the selected refugees. IOM also conducts the medical check and carries out a pre-departure orientation for the refugees. Lastly, BAMF staff might accompany refugees on their flight to Germany before handing over the responsibility to the local authorities after the arrival in Germany (UNHCR, 2018c).

Both UNHCR and BAMF thus play a crucial role in the selection process as well as a coordinating role throughout the whole admission process. Still, their responsibilities and objectives differ throughout the process: while UNHCR’s main role is to ensure that the most vulnerable refugees are pre-selected for resettlement, BAMF’s main responsibility lies in selecting refugees according to Germany’s national selection criteria. These include–but also go beyond–vulnerability and protection concerns. Both stakeholders thus need to navigate and negotiate their individual mandates throughout the selection process while making sure to successfully implement the whole resettlement process. The following section therefore takes a closer look at the two stakeholders’ diverging objectives in selecting refugees for resettlement while highlighting their interdependencies within the process.

UNHCR’s and BAMF’s Objectives and Interdependencies in the Resettlement Process

As stated above, UNHCR is responsible for identifying refugees for resettlement based on their vulnerability (according to UNHCR’s submission categories), while BAMF selects refugees according to Germany’s selection criteria that include, but also go beyond, vulnerability and protection risks considerations. One of the main differences between UNHCR’s and BAMF’s objectives in the selection process thus lies in their different prioritization of vulnerability criteria for refugees’ selection for resettlement.

As such, UNHCR identifies refugees for resettlement based on “objective need rather than on the subjective desire of refugees themselves or other actors such as host states or resettlement states” (Labman, 2019, 27). If this is entirely true is impossible to verify, since all implementation processes include a degree of agency and discretion of implementing actors (Lipsky, 2010). Still, there is a clear distinction between UNHCR’s and BAMF’s objectives in the selection of refugees due to the fact that UNHCR is not considering the prospective integration of refugees in Germany. In contrast, BAMF is responsible for selecting those most vulnerable refugees who the German government deems able to integrate (better) in Germany.

“Integration Potential” as Selection Criterion for Resettlement

As stated above, Germany is not the only resettlement country that employs national selection criteria in addition to UNHCR’s submission criteria. In fact, especially European resettlement countries often employ national selection criteria, such as refugees’ “integration potential,” in their selection process (see the country chapters of the UNHCR Resettlement Handbook as well as Cellini, 2018; Westerby, 2020). Ireland, for instance, even goes as far as to include in its country chapter that Ireland “requires a ‘balanced’ caseload. This […] must also include community leaders and, where possible, spiritual leaders” (UNHCR, 2018d, 4). Besides, also the EU Commission’s proposal for an EU resettlement framework refers to “social or cultural links, or other characteristics that can facilitate integration” (European Commission, 2016, Article 10) as considerations for selecting refugees for resettlement.

This tendency to include refugees’ “integration potential” as an additional selection criteria for resettlement has received considerable criticism from civil society organizations and scholars alike (see for instance ECRE, 2017; Bamberg, 2018; Westerby, 2020). Often, it is perceived as a means for resettlement countries to only select “desired” refugees, and hence transforming resettlement into a tool for migration management. Also the UNHCR resettlement handbook specifically states that “the notion of integration potential should not negatively influence the selection and promotion of resettlement cases” (UNHCR, 2011, 245). In this line of argumentation, the responsibility lies with the resettlement country to ensure that refugees can integrate in the resettlement country and not the other way around (interviewee from UNHCR Jordan 2019).

However, from a resettlement country’s perspective it could also be argued that it is easier for refugees to acclimate and settle down in a resettlement country when they possess a “higher integration potential.” Taking refugees’ social and cultural links to a resettlement country into account in the selection would thus also be in the interest of the selected refugees.

Although this argument might apply to the situation of some pre-selected refugees, and notwithstanding the paternalism it displays, it is important to remember the possibilities refugees have when they are not selected for resettlement which are more often than not: none. Consequently, many refugees might rather opt for encountering obstacles in their integration in a resettlement country than the precarious conditions they are faced with in the host country. For instance, one interviewed refugee who was resettled from Turkey to Germany, and who was afraid of racism and how she would integrate in Germany, stated that “the situation in Germany is a thousand times better than in Turkey. I would have always said yes to resettlement” (refugee interviewee, Friedland 2019). Then again, others might not. The point here is to take the agency of pre-selected refugees into account instead of assuming what would be in their best interest.

In addition to the criticism of employing “integration potential” as a selection criterion, it also remains unclear how BAMF operationalizes said criterion. Welfens and Bonjour (2020) point out in their analysis of family norms in the selection process of Germany’s program from Turkey, that “how exactly the BAMF assesses “integration potential” or in which instances it is deemed to be “too low” remains opaque” (Welfens and Bonjour, 2020, 15). The authors also provide a quote from a BAMF representative who, after being asked about BAMF’s definition of ‘integration capacity’ at a resettlement expert meeting, responded by saying:

“Well capacity is … I would rather say “perspective” and I would say that there are no fixed criteria that you can specify in an administrative regulation. Rather we ask about personal ideas about the life in Germany …we also emphasize that Germany is an open society, that it is very diverse, freedom of religion—and we ask concretely about that […]” (interviewee from BAMF as quoted in Welfens and Bonjour, 2020, 15).

Indeed, many interviewed resettled refugees mentioned that the interview with BAMF personnel included information about Germany, such as German culture, democratic principles as well as rights and obligations. Some respondents also pointed out that they were asked about their religion and their habits with regards to praying and fasting. In addition, one respondent mentioned that he was being asked “weird” questions, such as “Would you help a German man who is beaten by Arabs?” (refugee interviewee, Friedland 2019).

Still, these are only snapshots of refugees’ interview experiences that do not explain how ‘integration potential’ is actually operationalized by BAMF. Nor is it clear how much weight BAMF personnel puts on ‘integration potential’ considerations when selecting refugees for resettlement. In this regard, there might be a “discursive gap” (Czaika and Haas, 2013) between the public policy discourse on “integration potential” as a selection criterion in resettlement programs and actual policies on paper. In addition, there might also be an “implementation gap,” pointing to a discrepancy between policies on paper (that are not publicly available) on the operationalization of the ‘integration potential’ and their actual implementation (ibid.) Thus, although the introduction of ‘integration potential’ as an additional selection criterion for resettlement has received considerable criticism–both on the EU- as well as the national level–its operationalization and its importance for refugees’ selection remain a black-box.

Notwithstanding these discrepancies, the above discussion highlights that viewpoints on refugees’ “integration potential” as a selection criterion for resettlement can differ considerably between stakeholders involved in the resettlement process and other stakeholders working on resettlement. Still, and despite diverging objectives, the following analysis highlights that stakeholders depend on each other in the process in order to successfully implement the resettlement programs.

UNHCR’s and BAMF’s Interdependencies in the Resettlement Process

Since resettlement is a process where the activity of one stakeholder feeds into the activity of the next stakeholder, interdependencies between stakeholders exist in and between all stages of the process. During the selection process, stakeholders are dependent on the (pre-) selection conducted by other stakeholder(s) first in line. In the case of humanitarian admission from Turkey, UNHCR is dependent on the Turkish migration authorities, since only refugees that are referred by them can be reviewed for resettlement by UNHCR. As a result, UNHCR might not be able to consider all refugees who would fall under the UNHCR submission categories for the pre-selection in Turkey.

In contrast, the Jordanian government is not involved in resettlement activities. With regards to resettlement from Jordan, UNHCR is thus the first stakeholder pre-selecting refugees for resettlement without being dependent on referrals from host government authorities.

In both processes, however, BAMF is dependent on UNHCR’s pre-selection of refugees. Consequently, refugees are first selected according to UNHCR’s vulnerability criteria and then according to Germany’s national selection criteria. The German national selection criteria are thus only applied for the pool of cases that has been pre-identified by UNHCR. Even if BAMF takes refugees’ “integration potential” into account for the final selection, “cherry-picking” is not possible amongst all refugees, but only amongst those who were pre-selected by UNHCR and are therefore deemed (the most) vulnerable by UNHCR.

On the other hand, UNHCR is also depended on BAMF to accept the pre-selected refugees. Thus, only pre-screened candidates who have the prospect of being selected by BAMF are referred, which again might not necessarily include the most vulnerable refugees in the pre-selected pool of cases. Indeed, this creates a dilemma for UNHCR. On the one hand, UNHCR is responsible to ensure that the most vulnerable refugees are selected for resettlement. On the other hand, UNHCR staff is advised to take “selection criteria and admission priorities of resettlement countries” (UNHCR, 2011, 354) into account for the identification of suitable resettlement countries to ensure that cases have a chance to be accepted by the identified resettlement country8.

As such, UNHCR could be perceived as a “subcontractor” (Lavenex, 2015) for the implementation of Germany’s resettlement and humanitarian admission programs by providing the groundwork for BAMF to make their selection of refugees. However, BAMF is also dependent on UNHCR’s pre-selection and ongoing coordination of the resettlement and humanitarian admission processes. Due to these interdependencies, UNHCR’s and BAMF’s relationship in the multi-level governance of the resettlement process could be rather described as an (unequal) partnership than a subcontracting relationship. As such, the implementation of the programs is not entirely delegated to UNHCR and UNHCR can still shape the programs according to its own mandate to some extent. It could thus be argued that, although UNHCR is an agent in the implementation of the German resettlement programs, the agency also acts as “agender-setter” and “counterweight.” In this regard, UNHCR seeks to “complement and correct” (Lavenex, 2015, 2) the specific resettlement programs according to its mandate as the guardian of the 1951 Geneva Refugee Convention. Still, the ultimate decision-making authority with regards to refugees’ selection lies with BAMF.

More general, it can be argued that the diversification of resettlement programs in the last decade shifts a considerable degree of authority over resettlement programming back to resettlement countries. Whereas the traditional view on resettlement foresees a reliance on UNHCR’s submission categories as the sole selection criteria, the diversification of programs and the subsequent reliance on national selection criteria reinforces resettlement countries’ decision-making authority in resettlement.

Consequently, whereas multi-level governance foresees a shift from nation states as sole decision-makers to a diffusion of power amongst stakeholders on subnational, national and supranational levels, developments in the field of resettlement since the early 2000 rather suggest a shift of decision-making authority back to nation states.

To capture power relations beyond the relationships of stakeholders in implementing the resettlement process, it is also important to keep in mind how international organizations are funded–which is primarily by donor governments (Roper and Barria, 2010). In the case of UNHCR, Germany actually represents one of the major donor countries.

In 2019 and 2020, Germany ranked third amongst the largest donor countries to UNHCR after the United States and the European Union with a contribution of USD 390.5 million in 2019 and USD 447 million in 2020 (UNHCR, 2021a; UNHCR, 2020a). In 2018, Germany even represented–for the first time in history–the second largest donor to UNHCR after the United States but before the European Union with a contribution of USD 476.9 million (UNHCR, 2018e). To carry out its mandate, UNHCR is thus dependent on funding by the German government, as well as on other major donors such as the United States and the European Union.

Consequently, the concept of international organization as “agents in the implementation of EU policies” (Lavenex, 2015, 7) who are dependent on funding and support by their donors can also be applied to the relationship between UNHCR and Germany more broadly. In this regard, there is a clear power imbalance between Germany as donor and UNHCR as funding receiver. Still, literature (see for instance Garnier, 2014; Barnett, 2001; Barnett and Finnemore 1999; Chimni, 1998) has pointed out how UNHCR has gained autonomy vis-à-vis states. Garnier for instance refers to the “significant degree of UNHCR’s institutional autonomy” (2014, 954) and Chimni points out that UNHCR’s role is to “be a guardian of the larger interests of the coalition which establishes and sustains it, not the individual interests of its members. This often brings the organization in confrontation with even its more powerful members” (1998, 368). Despite the organization’s dependence on donor countries, including Germany, UNHCR can thus still play a role as “agenda-setter” and “counterweight” to states’ actions.

Conclusion

Starting with the observation that resettlement programs have diversified since the early 2000s, the article provided an overview about historical and current approaches towards resettlement. Thereby, it was argued that with the increase of resettlement countries, also perceptions about resettlement and motivations for offering resettlement places have become more diverse. As such, resettlement is increasingly cited as a tool for migration management. In addition, resettlement countries often opt to respond to “hot conflicts” through humanitarian admission programs instead of permanent resettlement programs.

Such humanitarian admission programs are mostly perceived by resettlement countries as a temporary solution and tend to give less rights to admitted refugees: in the case of Germany, for instance, refugees admitted through the humanitarian admission program from Turkey can only apply for a settlement permit after five years, whereas refugees admitted via resettlement can already apply for a settlement permit after three years of residence in Germany. Consequently, it is important to distinguish between the different resettlement and humanitarian admission programs and to shed light on their similarities and differences.

The article did so by proposing a new conceptualization of the resettlement process and by applying the general overview to two exemplary programs: the German resettlement program from Jordan and the German humanitarian admission program from Turkey.

Given that resettlement (and humanitarian admission) processes are implemented by many different stakeholders who coordinate and negotiate the processes across different levels of governance, the article employed the concept of multi-level governance as a theoretical lens for its analysis. As such, the article focused on UNHCR and BAMF as two main stakeholders responsible for the selection of refugees based on inclusion criteria and outlined their responsibilities and objectives in the selection process and beyond.