94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

BRIEF RESEARCH REPORT article

Front. Polit. Sci., 31 March 2021

Sec. Elections and Representation

Volume 3 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2021.627982

This article is part of the Research TopicVoting from AbroadView all 8 articles

This research paper examines the instances of representation of the expatriate Finnish citizen in the different stages of the legislative process in Finland: the preparation of law bills, the process in the Parliamentary committees and in the plenary sessions of the Finnish Parliament Eduskunta. The aim is to answer the questions how many and what kind of expatriate Finns issues there has been on the political agenda, when those issues were there, and who acted for the expatriates then. Here, the research approach is descriptive. Newly digitalized collections of legislative documents create novel opportunities to seek efficiently through a large number of records and find topics that have not gained much attention, in addition to the more obvious cases such as the dual citizenship or recently the postal voting. In Finland, the Finnish diaspora has not been a fervently debated issue and it is only rarely mentioned in the plenary debates of the Parliament. The data includes two kinds of sources, actions by the MPs and Government bills. In the Finnish case, the number of relevant documents is small. Therefore, including different types of text into a single study is necessary to find out the political forces that have influence on the issues concerning the Finnish citizen abroad.

How does the Finnish Parliament Eduskunta handle issues which concern the Finnish citizen living abroad? The analysis draws along Pitkin's theory of representation, particularly substantive representation, in the context of parliamentary actions: how the expatriate citizen's issues are treated in the legislative agenda, who is acting for the expatriates and which kind of issues arise in the parliamentary speeches, motions and questions. In contrast, analyzing the descriptive representation, i.e., how similar the characteristics of the representatives are to the represented, is less of interest in the case of Finland because only a few MPs has expatriate origins.

The expatriates are a heterogeneous group and their interests might be very diverse. Therefore, defining an issue as relevant for the expatriates is a task that should be done cautiously. Here, the scope is limited to a small number of cases where the expatriates are deliberately mentioned though it might leave some relevant pieces of legislation excluded from the data. In the last two decades, there have been only two major debates regarding the expatriates: on the dual citizenship between 1999 and 2002 and on postal voting from abroad which was introduced in 2017.

Recent digitalization makes it possible to examine the presence of expatriate issues in public documents on a new larger scale. The instances of expatriate representation which are included in the analysis were identified with a keyword approach similar to Østergaard-Nielsen and Ciornei (2019a), simply by the appearance of a word referring to the emigrant citizen of Finland.

The transnational outreach of political parties can be classified to four categories by a typology by Østergaard-Nielsen and Ciornei (2019b): on the degree of transnational infrastructure (low–high) and the degree of ideological linkage (low–high). Finland is a prime example of a case to be classified as low on both of these dimensions. There are not transnational organizations in the party hierarchies. The issues concerning the non-resident citizen are absent on the party programs and they appear only sporadically on the political agenda.

Peltoniemi (2016, 2018) has conducted extensive research on the Finnish non-resident citizens and she supplies plenty of information about the represented, but until now, there has not been research what the representatives do on the expatriate issues though the topic has been studied on many other West-European countries. Østergaard-Nielsen et al. (2019) list a variety of sources where to infer party positions on emigrant issues: party manifestos, voter's perceptions, roll-call voting or parliamentary speeches. Østergaard-Nielsen and Ciornei (2019a) analyze parliamentary questions and emigration-related motions to compare issue salience and emigrant representation in four countries. Here, a similar multisource approach is applied. Because the emigrant topic has not been among the salient ones in Finland, any single source would alone provide little information, but when combined they can supply information about the Finnish case.

Next, I briefly summarize the concept of representation before proceeding to the features of the Finnish political system. The theory of representation is based on studies on representation by gender and I do not present new theory for the expatriate representation. In total, the number of instances where the expatriate citizen appeared in the parliamentary speeches, questions, motions and Government bills was surprisingly small. It remains to be questioned if the expatriate citizens are represented at all.

In her seminal work, Pitkin (1967, p. 61) wrote that descriptive representation—standing for the represented—depends on the representative's characteristics, “on what he is or is like, on being something rather than doing something.” Shortly, it is the extent to which a representative resembles those being represented (Dovi, 2018). Representation has been extensively researched in feminist studies and for diaspora studies those definitions can be applied by replacing the women with the expatriates (Palop García, 2019).

Many studies characterize descriptive representation plainly as the distribution of seats in representative bodies with different wordings, like “the numbers of female officeholders” (Clayton et al., 2017), “the proportion of women MPs in Parliament” (Blaxill and Beelen, 2016, p. 414), “shares of female MPs” (Bäck et al., 2014) or “the numerical distribution of seats between women and men in representative bodies on different levels as well as the reasons behind variations of representation of the sexes” (Stensöta, 2012, p. 130).

Descriptive representation can be defined more broadly, too. Bates and Sealey (2019, p. 242) describe it as “the extent to which female presence within institutions reflects their presence within society.” Hinojosa et al. (2018) include also talking functions to descriptive representation: “women can invoke their gender by using phrases like ‘as a woman' in their political communication, thus calling attention to their role as descriptive representatives.” Pitkin used the phrase “standing for” to define descriptive representation (and symbolic representation, too), and “acting for” to describe substantive representation, and while speaking is acting, Hinojosa et al. (2018) formulated it as follows: “‘speaking for' women is a form of substantive representation, while ‘speaking as' women is a means of descriptively representing women.”

In Finland, the descriptive representation of expatriate citizen is very low. It is not straightforward to operationalize it because many MPs have lived some time abroad for their work or studies, or as members of the European Parliament. Only a few MPs are born elsewhere than in Finland. While the places of residence and possible experiences as an expatriate of each MP are difficult to determine, we might look for instances where the MP describes themselves as expatriates or refer to their expatriate past, which Hinojosa et al. (2018) conceptualized as descriptive presentation. That has happened only a few times in Eduskunta.

To define substantive representation, “acting for” the represented, Pitkin (1967) condensed the concept into the phrase: “acting in the interests of the represented, in a manner responsive to them.” Bates and Sealey (2019, p. 242) define substantive representation for women as “the extent to which representatives act for women and promote women's interests” and Clayton et al. (2017) as “the articulation of women's interests in the legislative process” and Stensöta (2012, p. 130) as “the difference that a more equal share of women make substantially, as well as what conditions enable/constrain them/us to exert such impact.” More generally, analyzing substantive representation is “looking at the effects of women's presence in parliament” (Bäck et al., 2014).

This differs from the definitions where the characteristics of the representative are distinct from the action for the represented. For example, Hinojosa et al. (2018) writes that “substantive representation is defined as the representation of women's interests in policymaking. The representative need not be a woman to represent women's interests, any more so than the interests of the homeless would need to be represented by a homeless legislator.” In the Finnish case, substantive representation is the interesting subject to study because the descriptive representation is such low.

Which interests are relevant? Palop García (2018) included in the “emigrant agenda” “(1) the status of non-resident citizens, for instance, the regulation of dual nationality; (2) policies that aim at assisting non-residents abroad, such as the improvement in consular services; (3) policies that foster the integration of emigrants in the state of origin, for example, the creation of a consultative body to discuss emigrant issues, and (4) policies oriented to foster the return of migrants.” Østergaard-Nielsen and Ciornei (2019a) classified legislative proposals to six categories: (1) Culture and education, (2) External voting, (3) Fiscal issues, (4) Nationality, (5) Return and impact, and (6) Transnational welfare and protection. In this study, the question about how to operationalize substantive representation is answered by simply counting any mention of the expatriates as an instance of it, though in a couple of cases explained below someone else's interest may have been represented.

Eduskunta is unicameral and there are 200 MPs who are chosen for 4 years period. They are elected by open list d'Hondt system in 12 constituencies (14 before 2015), whose size varied between 7 and 32 depending on the number of Finnish citizens living in the constituency. The number of non-resident citizens assigned to a constituency does not affect the number of its representatives. One candidate is chosen from the Åland islands. The votes go directly to a candidate and there are neither leveling seats nor imposed thresholds. Intra-party competition is hard.

The expatriates are assigned to a district according to the last place of residence in Finland, or of their parents for those who never lived in Finland. An eligible Finnish citizen can become a candidate in any constituency independent of the place of residence.

The party districts recruit the candidates by a member vote and the party district organization may replace half of the candidates. All major parties try to make balanced candidate lists at least by age, gender, profession and the place of residence in the constituency in Finland. Though there are not formal obstacles to an expatriate to get a seat in Eduskunta and the electoral system in general can be described as open, it can be difficult for a newcomer to achieve the candidacy because it requires support in the district level.

There are close to 300 000 Finnish expatriate citizens and in addition 1.6 million people with Finnish background or ancestry1. In the 2019 Parliamentary elections, 254,574 Finnish citizens had their place of residence elsewhere than in Finland, which is 5.6% of the electorate. In 2019 parliamentary elections, where the postal voting was used the first time, the expatriate turnout reached its maximum at 12.6% (32,053 votes) which was far less than the 72.1% among citizen living in Finland. In the past, the difference has been at the same level or greater.

The party system is fragmented. In Eduskunta, there have been eight parties, of which three or four big ones, but no dominant party. Since 1970's, the Cabinets were majority coalitions with at least two of the big parties. The group cohesion is very high. All parties have been able to enter Government and there are not pre-election coalitions. The government program negotiations are an important step in policy-making, where a compromise is made on the goals of the parties, but no party has mentioned the expatriates on their election or party platforms2. Below, the results are not reported by party because the activity was evenly distributed among the parties.

Examining the parliamentary actions by individual representatives provides information on issues they wish into the agenda and on how the decisions are reasoned. New national legislation is created mostly by Government bills. Because their content is to a large extent controlled by the governing parties, information about the MPs can be supplemented by analyzing the Government bills though relation between the representatives and the represented is not as straightforward as in Pitkin's theory.

This analysis relies on distinct types of texts: parliamentary speeches as they are written in the minutes of Parliament, the government bills, and MPs motions and written questions. The oral questions are included in the speech data.

The Government bills, the Committee reports and the expert statements for the Committees are collected from Lakitutka-databank. The documents are publicly available, but the usability improves when Lakitutka is completed3. The plenary speeches are collected from many sources: author's database (from 1999 to 2014) and FIN-Clarin corpus (2015 and 2016). The parliamentary sessions since 2017 and before 1999 are from Eduskunta webpage. Unfortunately, those records are only available in noisy pdf-files.

The Lakitutka data included all the government bills from 1991, a total of 7,398 documents (October 2020). A bill is usually a lengthy document including the proposed act, a reasoning, motivation and impact assessment. The query was “postal voting OR Internet voting OR repatriation OR expatriate Finns”4 and it found 149 bills, of which 33 were appropriations in the Budget. In addition, the search word “dual citizen*”5 was applied but it returned mostly legislation which considered dual citizens who live in Finland, or if living abroad, the smaller query already returned those bills.

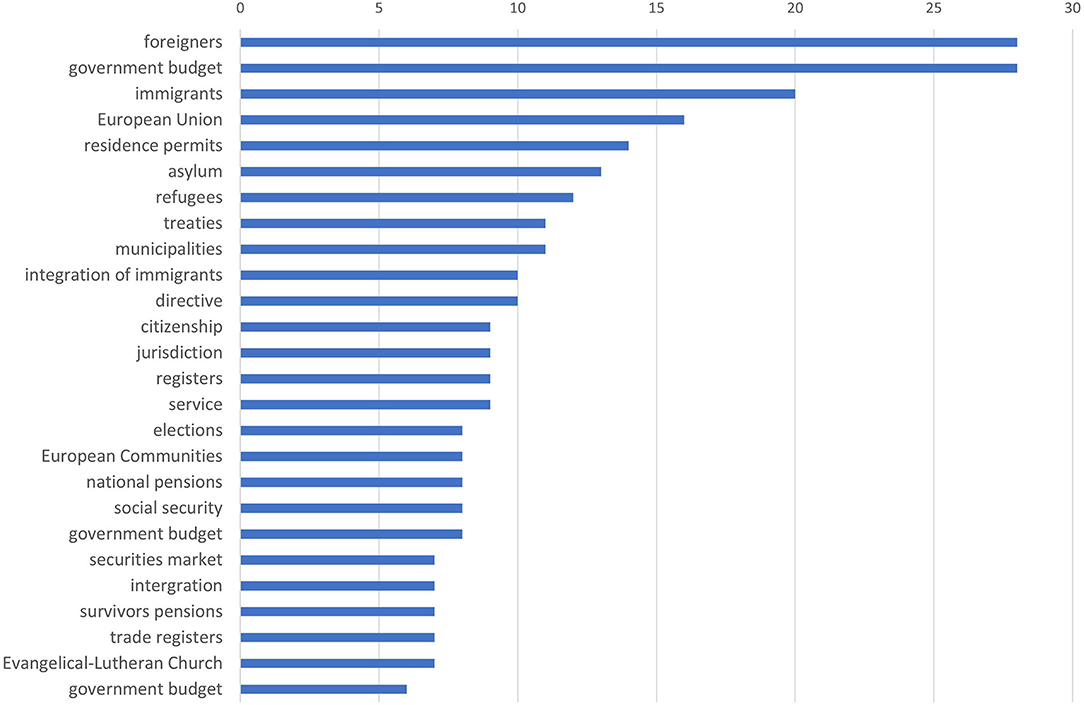

The bills are classified with a subject index in Finnish6. Figure 1 shows the most frequent index words of the bills. There were 1,516 index words in total. On average, a bill was described with 10.2 words (median 7; sd. 18.4). From the index search, we can conclude that the expatriate issues were handled among topics concerning migration, the foreign citizens, public officials or police. Fewer mentions were on the social security and pensions. The European Union was among the mentions too. The elections were mentioned a few times among electoral reforms introducing European Parliament elections and the postal vote. Sometimes, the mention was a minor detail in a large law reform, or in the case of the annual budget, an appropriation for the expatriate's central association Finland Society or the Finnish Expatriate Parliament.

Figure 1. The most frequent index words in the government bills since 1991 for query “kirjeään* OR postiään* OR nettiään* OR paluumuut* OR ulkosuomalai*” (postal voting OR Internet voting OR repatriation OR expatriate Finns). Lakitutka-databank 29th October 2020. Search hits 149/7398 (2.0%) of the bills.

Many bills concerned issues which affected Finns living in Finland as well as abroad but where the main focus was on in Finland. For example, legislation was issued on postal voting in registered associations or shareholders' meetings. Others concerned, for example, banking regulations, European co-operation on border control, UN peacekeepers, asylum and refugees. Some larger pieces of legislation concerned international treaties, like Finland joining the EU, which surely affects expatriate's life but cannot be counted as a mainly expatriate issue.

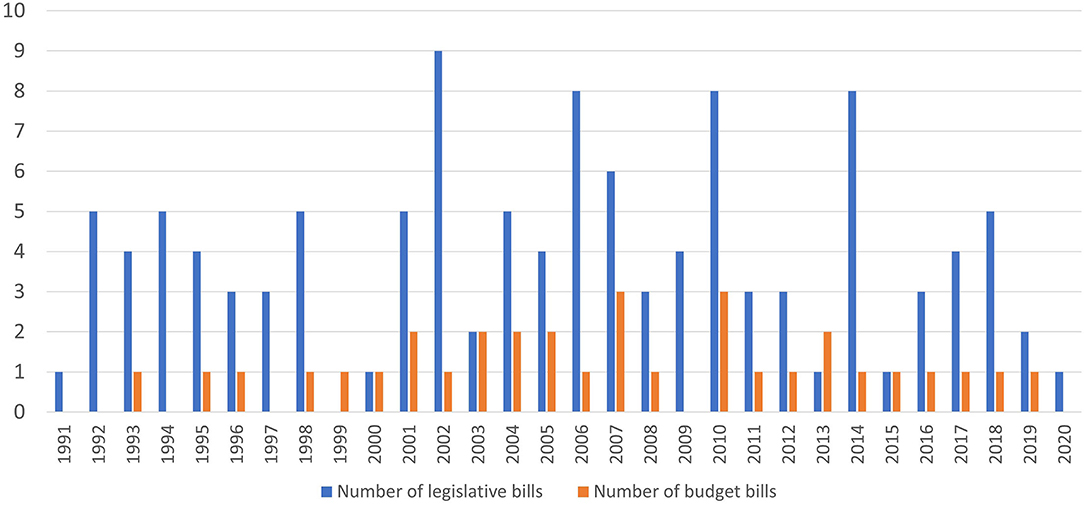

Figure 2 shows that the number of bills varies little yearly unlike the number of speeches or questions. A Finnish peculiarity is the Ingrian people who moved to Ingria, the area where St. Petersburg is situated, in 17th-century. After the collapse of Soviet Union, they could move to Finland as repatriation. In 1990's, many of the mentions of repatriation in the bills concern the Ingrians and appropriations for the migration costs. Sometimes repatriation might refer to the foreign nationals in Finland who migrate to their countries of origin.

Figure 2. The number of bills by type (budget/other legislation) and by the year of the drafting of the bill.

The appropriations went to the Finnish schools abroad, to the Finland Society and to the Finnish Expatriate Parliament. To sum up, the expatriates were rarely represented as a group and their interests were on the legislative agenda often in connection with foreigners and immigration.

The plenary speeches include several types of debate, like on the law bills, budget laws, interpellations and a weekly oral question hour. Mostly, it is possible for every MP to speak at some point in the debate, but in some cases, like the question hour, the time is very scarce. The speech must relate to the subject matter of the debate and there is not any open floor time though by submitting a motion opens a chance to speak about any topic.

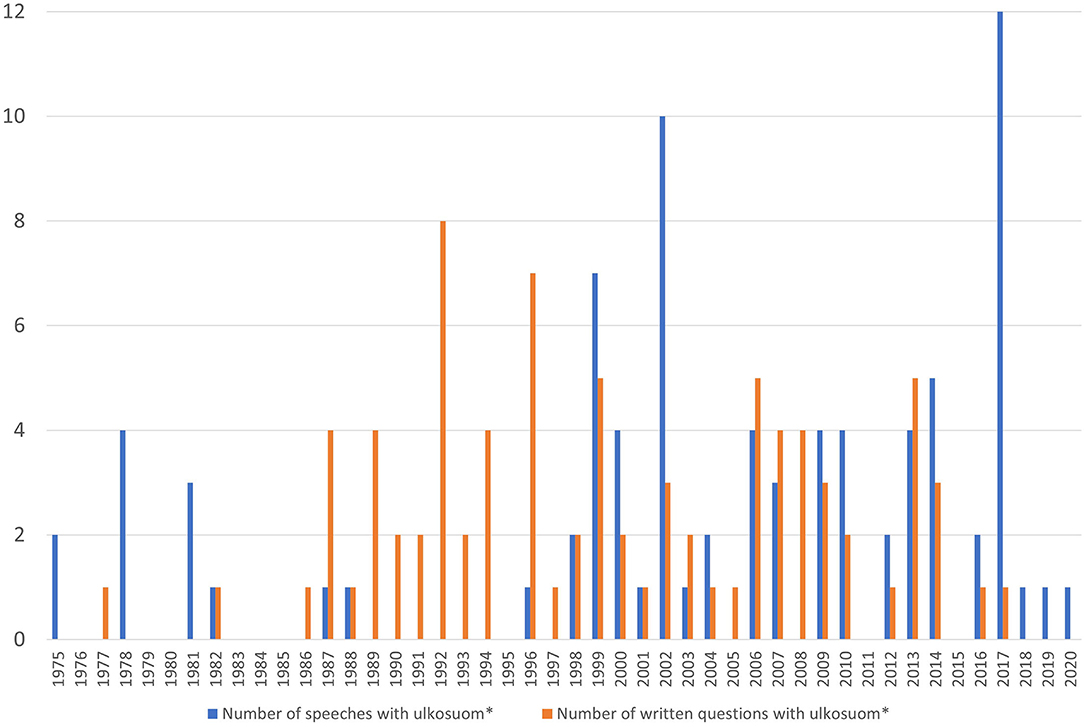

With the speeches, the simplest query ulkosuom* appeared the most useful because other queries returned numerous extraneous speeches. Since 1975, there were only 83 such speeches in the data while between 2000 and 2014 annual speech count was on average 11,890. Figure 3 shows how the number peaked in the debates on the dual citizenship between 1999 and 2002 and on postal voting in 2017. In a debate, the search word is not always repeated in every speech. For example, in the postal voting debate, there were 28 speeches in total, only 12 included ulkosuom*, but then, they concerned more regional elections bill, a current issue then.

Figure 3. The numbers of plenary speeches and written questions with word ulkosuom* (expatriate Finn) in Eduskunta from 1975.

Before 1975, the search returned 43 speeches, but it because of the data quality, it might be an incomplete result. The first mention was in 1929, whether to fund emigrant society's information official. The goal was to persuade Finns not to leave their homeland. In 1969–1970, a debate on expatriate voting rights ensued among election reform.

In the 1970's and early 1980's, the topics were voting abroad, especially in Sweden, and founding a Finnish school there, then in 1990's, the repatriation of Ingrians. In between 1999 and 2002, there was a lengthy discussion on dual citizenship. The most recent debate on an expatriate issue was the introduction of postal voting from abroad in 2017. It was not the first time the issue was mentioned, and there were a few speeches on it already in 2010 and 2014. Other issues were the visibility of the Finnish public broadcasting and appropriations to the Finland Society and Finnish schools abroad. Some speeches were acting for the interests for the Finnish economy rather than the expatriates: how to take advantage of the expatriates for promoting Finnish exports and how to attract skilled professionals like nurses to return.

The debates were participated by MPs from all major parties, but none was especially expatriate-oriented. Usually, the issues were on the agenda by a few enthusiastic representatives at a time, if at all. Last century, the tone was sometimes quite negative, which has changed since then.

In Eduskunta, a major part of the parliamentary action happens in the 17 standing Committees. The Committees deliberate behind closed doors and the publicly available outputs are the Committee reports, the statements to the other Committees, and the expert opinions (including interest groups) delivered at the request of the Committee. The Committee members may submit a dissenting opinion for the record.

At the moment of writing, the Lakitutka-dataset includes 38,436 documents, but might not be complete. The dataset does not yet include MP's motions or citizen initiatives. The analysis is based on the search word ulkosuomal*, which returns 20 Committee reports and 2 statements to another Committee, and 18 expert statements. The expatriate issues were processed in many Committees, where the highest numbers were the Finance Committee (5), the Constitutional Law Committee (4), and the Administration Committee (3). Since 1996, there were from zero to two such reports per year.

In the Finance Committee, the expatriates appeared in a detail in a long list of appropriations. The Constitutional Law Committee considered issues of the citizenship, the electoral participation and conscription, and it listened to expert opinions by the Finland Society and the Expatriate Parliament. Those were cases where the expatriates were clearly represented by their advocate organization which means that someone in the Committee has invited them into the session as an expert. The Administration Committee considered miscellaneous issues like identity card and the right to medical treatment in the EU.

At the moment of writing, the expert opinions were available in the Lakitutka-databank from 2015. The most frequently heard expert was Finland Association (four times), followed by The Association Supporting the Finnish Language Schools Abroad (three times). Two expert opinions were made by the professors of law, two by senior civil servants regarding the postal vote. Six expert opinions were issued by schools and associations related to education. The associations wanted to improve the education of the children of the Finnish expatriates or at least keep the appropriations on the same level as before. The professors regarded postal voting desirable but were cautious on the ballot confidentiality.

In addition to speeches in the plenary sessions or deliberation in the Committees, the MPs have many other options to act for the represented in Eduskunta. Individual MPs, or a group of MPs together, may submit written questions to the Government, and they may submit five types of motions: legislative motions, budgetary or supplementary budgetary motions, petitionary motions or motions for debate. A petitionary motion demands the Government to begin the preparation of new legislation or other kind of action. A motion for debate, if accepted by the Speaker's Council, leads to a topical debate in the plenary session.

The search method was similar to above, the keyword ulkosuom* was applied. The expatriate issues were rare in every type of the motions and in the written questions. Since 1970, only four legislative motions included the keyword7. That is not to say that the motions were unimportant, instead a widely supported motion on dual citizenship by MP Riitta Prusti in 1999 eventually paved the way to major change in the legislation. The three other motions concerned the social security issues but they expired.

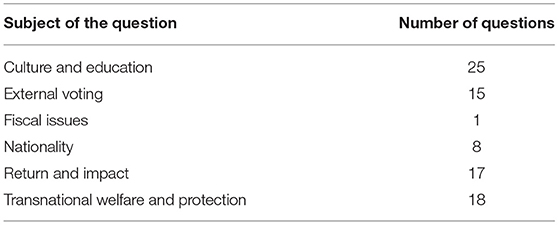

The written questions were analyzed from 1970 by a similar keyword search. It resulted in 84 hits, of which first appeared in 1977, then 11 in the 1980's, 31 in the 1990's, 26 in the 2000's and 13 last decade. In Table 1, the author applied Østergaard-Nielsen and Ciornei (2019a) classification to the written questions.

Table 1. The number of written questions including ulkosuom* since 1970 classified to the categories by Østergaard-Nielsen and Ciornei (2019a).

Before 1987, the questions concerned voting possibilities abroad, postal voting and social security, then social security like unemployment benefits abroad. In the 1990's, a big proportion of the questions concerned the repatriation of the Ingrians. Questions on fiscal issues (defined as taxes, remittances, loans) were issued only once in 1987. In the last two decades, the funding for the Finnish schools and public broadcasts aroused many questions. The nationality-related questions concerned dual citizenship and the fees for gaining the Finnish nationality.

From 1970, there have been 28 petitionary motions, none accepted, which is a small number compared with the hundreds of motions issued annually in the late 20th Century. The number of petitionary motions has decreased in the last two decades and the most recent motion on the expatriate citizen was issued in 2000. In the 1970's, the emigration to Sweden and voting there appeared in the motions, then more culture and social security. In total, there were 10 motions on culture and education, 4 on external voting, 7 on return and impact 7 on transnational welfare and protection.

The budgetary motions, which are hardly ever accepted, were analyzed from 1992. The keyword ulkosuom* appeared in 19 motions, which is again a small number compared with the average of 835 budgetary motions per year between 1992 and 2019. Most of the budgetary motions (11) concern culture and education, like the Finnish schools abroad, or regarding the size of the budget, small amounts of funding to a museum or an association connecting folk dance groups. The second most frequent category (6) concerned transnational welfare and one demanded funding for consulates to facilitate access to the passports. In summary, with the exception of dual citizenship, the impact of the motions was small.

The expatriate Finns are a kind of “forgotten people” in the sense of parliamentary representation. It does not necessarily mean that they are unhappy with the situation. Rather than represented, issues which are important to the Finnish expatriates or at least a part of them might have been cases of advocacy rather than representation.

Compared with the citizen living in Finland, the low turnout in the parliamentary elections among the expatriates does not create demand for active expatriate policy, there is not much supply either, at least in the form of legislative activity. With recently introduced postal voting, it remains to be seen if the situation changes. There are no differences between the parties, as none of them are particularly active in expatriate matters.

One thing that might discourage voting is that the expatriate vote is scattered to the different electoral districts and even if a candidate would promote expatriate issues, they would be able to gather the vote only from a part of the citizen abroad.

This study applied a new framework based on theories developed in the field of gender studies, which in turn draws on Pitkin's classical analysis. The expatriate issues were identified based on the core points identified in the previous studies. As the occurrence of the expatriate issues was rare, Finland provided a kind of negative finding in the context of emigrant representation.

It is beyond the scope of this study to ask why transnational activity is currently so low in Eduskunta or if it would still be rational not to seek more expatriate activity and support after the internet has lowered the costs of communication to and among the non-resident citizens. For comparative studies, Finland offers a case where there is mainly untapped potential in this regard.

To the question, who does represent the non-resident citizen in Finland, the answer is, in addition to the advocate associations like Finland Society, not any specific party, but a few enthusiastic MPs every now and then.

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found at: https://www.eduskunta.fi/FI/taysistunto/Sivut/Taysistuntojen-poytakirjat.aspx; https://lataamo.utu.fi/; http://urn.fi/urn:nbn:fi:lb-2017020202.

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Facilitating Electoral Participation from Abroad (FACE) -project, University of Helsinki.

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

1. ^During 1880–1930, 400,000 Finns emigrated to North America. The second wave took place during 1960's and 1970's when around 300,000 Finns emigrated to Sweden. Since 1980's, emigration has been more Europe-centred (Peltoniemi, 2018). During the larger waves, dual citizenship was not available and many emigrants now have the nationality of their destination country.

2. ^A search for “expatriates” in Finnish and Swedish on the Finnish party platform archive Pohtiva (https://www.fsd.tuni.fi/pohtiva/ accessed Jan-7th-2021).

3. ^A beta-version is already publicly available at https://lataamo.utu.fi/.

4. ^“kirjeään* OR postiään* OR nettiään* OR paluumuut* OR ulkosuomalai*”.

5. ^“kaksoiskansal*”.

6. ^English translation according to the Eduskunta Glossary http://www.eduskunta.fi/kirjasto/EKS/index.html?kieli=en.

7. ^On average, there were more than 200 legislative motions annually from 1991.

Bäck, H., Debus, M., and Müller, J. (2014). Who takes the parliamentary floor? The role of gender in speech-making in the Swedish Riksdag. Pol. Res. Q. 67, 504–518. doi: 10.1177/1065912914525861

Bates, S. H., and Sealey, A. (2019). Representing women, women representing: backbenchers' questions during Prime Minister's Questions, 1979–2010. Eur. J. Pol. Gender 2, 237–256. doi: 10.1332/251510819X15490283059237

Blaxill, L., and Beelen, K. (2016). A feminized language of democracy? The representation of women at Westminster since 1945. Twentieth Century Br. Hist. 27, 412–449. doi: 10.1093/tcbh/hww028

Clayton, A., Josefsson, C., and Wang, W. (2017). Quotas and women's substantive representation: evidence from a content analysis of Ugandan Plenary Debates. Pol. Gender 13, 276–304. doi: 10.1017/S1743923X16000453

Dovi, S. (2018). “Political representation,” in The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2018 Edition), ed E. N. Zalta. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2018/entries/political-representation/ (accessed February 28, 2020).

Hinojosa, M., Carle, J., and Woodall, G. S. (2018). Speaking as a woman: descriptive presentation and representation in Costa Rica's Legislative Assembly. J. Women Pol. Policy 39, 407–429. doi: 10.1080/1554477X.2018.1506204

Østergaard-Nielsen, E., and Ciornei, I. (2019a). Making the absent present: political parties and emigrant issues in country of origin parliaments. Party Pol. 25, 153–166. doi: 10.1177/1354068817697629

Østergaard-Nielsen, E., and Ciornei, I. (2019b). political parties and the transnational mobilisation of the emigrant vote. West Eur. Pol. 42, 618–644. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2018.1528105

Østergaard-Nielsen, E., Ciornei, I., and Lafleur, J.-M. (2019). Why do parties support emigrant voting rights? Eur. Pol. Sci. Rev. 11, 377–394. doi: 10.1017/S1755773919000171

Palop García, P. (2018). Contained or represented? The varied consequences of reserved seats for emigrants in the legislatures of Ecuador and Colombia. Comp. Migr. Stud. 6:38. doi: 10.1186/s40878-018-0101-7

Palop García, P. (2019). Institutional Representation of Emigrants in Their States of Origin: How Much Presence From Abroad? (Ph.D. dissertation). Freie Universität Berlin, Germany.

Peltoniemi, J. (2016). Overseas voters and representational deficit: regional representation challenged by emigration. Representation 52, 295–309. doi: 10.1080/00344893.2017.1300602

Peltoniemi, J. (2018). On the borderlines of voting: Finnish emigrants' transnational identities and political participation. Tampereen yliopistopaino. Retrieved from http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-03-0810-0

Pitkin, H. F. (1967). The Concept of Representation. Los Angeles, CA: University of Press. doi: 10.1525/9780520340503

Keywords: Eduskunta, parliaments, emigrants, expatriates, diaspora, representation, Finland

Citation: Makkonen K (2021) Is Anyone Representing Non-resident Finnish Citizens in the Legislative Process of Finland? Front. Polit. Sci. 3:627982. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2021.627982

Received: 10 November 2020; Accepted: 09 March 2021;

Published: 31 March 2021.

Edited by:

Irina Ciornei, Institut Barcelona d'Estudis Internacionals, SpainReviewed by:

Pedro C. Magalhães, University of Lisbon, PortugalCopyright © 2021 Makkonen. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kimmo Makkonen, a2lrYW1hQHV0dS5maQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.