- 1Institute for Socio-Economics, University of Duisburg-Essen, Duisburg, Germany

- 2Chair for Political Sociology, University of Bamberg, Bamberg, Germany

- 3Center for Political Communication, Zeppelin University, Friedrichshafen, Germany

Affective polarization has increased substantially in the United States and countries of Europe over the last decades and the ramifications of the COVID-19 pandemic have the potential to drastically reinforce such polarization. I investigate the degree and dynamic of affective polarization during the COVID-19 pandemic through a two-wave panel survey with a vignette experiment in Germany fielded in April/May and July/August 2020. I 1) compare the findings to a previous study from 2017, and 2) assess how economic distress due to the crisis changes perceptions of other partisans. Results show that the public today experiences slightly stronger polarization between AfD voters and supporters of other parties. Yet, higher economic distress decreases the negative sentiment of voters of other parties towards AfD supporters. I argue that experiencing economic distress increases the awareness of political debate and the responsiveness to government decisions. Thus, in times of broad cross-party consensus, this can translate into public opinion so that it makes people less hostile towards other partisans.

1 Introduction

In recent years affective political polarization has increased dramatically in the United States (Iyengar et al., 2019), but also in Europe and elsewhere (Reiljan, 2020; Wagner, 2020). In contrast to ideological polarization, which mostly considers differences in political views, affective polarization is more of an identity-based comparison between in- and out-groups (Iyengar et al., 2012; Mason, 2015; Mason, 2018). As such, it is defined as emotional attachment to in-group partisans and hostility towards out-group partisans (Hobolt et al., 2020). Thus, supporters of right-wing populist parties strongly oppose partisans of green or left-wing parties and vice versa, whereas both strongly favor their own fellow partisans. Importantly, such animosity is based on strong in-group identification and negative partisanship with out-groups (Tajfel and Turner, 1979; Medeiros and Noël, 2014) and not necessarily strong policy disagreement. In large part affective polarization has increased over the last decades mostly due to an increase in out-party animus and not stronger affection for the own party (Baldassarri and Gelman, 2008; Iyengar et al., 2019), as it has become widely acceptable to cast aspersions on supporters of other political parties (Iyengar and Westwood, 2015).1 Although there exists a multitude of factors that increase polarization, transformation processes play a particular role in shaping social sorting and out-group animus. Rapid social change and increased economic and cultural competition have transformed societies so that they are now divided between two groups: 1) the “winners” of globalization who we find mostly among the higher educated and who are described as cosmopolitan, more tolerant towards out-groups and leaning towards green and left-wing parties; and 2) the “losers” of globalization who are often found among the lower educated or within the working class and who are considered as more closed-minded and susceptible to right-wing populist parties (Kriesi et al., 2008).

Earlier studies have shown that citizens identify with these cleavages and that they can translate into social divides, too. Affective polarization has thus not only led to more negative perceptions between citizens and parties (Iyengar et al., 2019) but also between partisans in their daily lives (Helbling and Jungkunz, 2020; Jungkunz and Helbling, forthcoming). In particular, out-party animus is stronger than antipathy towards different ethnic groups and it is also asymmetric: supporters of mainstream parties dislike supporters of right-wing populist parties much more strongly than vice versa. Ultimately, affective polarization can shape individual policy beliefs and it politicizes even neutral or apolitical issues (Druckman et al., 2020).

To explore and disentangle the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on affective polarization a two-wave panel survey with a vignette experiment was conducted in Germany in April/May and July/August 2020. I first compare the average perceptions between different partisans with an earlier study from 2017. I find that the German public today experiences slightly stronger polarization between supporters of the right-wing populist AfD on the one hand, and supporters of other parties on the other. In a second step I then analyze how the experience of economic distress due to the corona crisis shapes citizens’ perceptions of partisan out-groups. Results show that higher economic distress decreases the negative sentiment of center and left-wing party voters towards AfD supporters, but not vice versa. I argue that the experience of distress increases the awareness of political debate and the responsiveness to government decisions. Thus, under broad cross-party consensus, this can translate into public opinion so that it makes people less hostile towards other partisans.

2 Polarization During the COVID-19 Pandemic

The current COVID-19 pandemic has the potential to drastically reinforce social and political polarization for two reasons. First, it is likely to intensify existing social divides, as it disproportionately affects the less-affluent parts of society. Within weeks millions of people around the world have experienced a substantial reduction of their working time or job loss, which led to massive drops in consumer spending, debt payments and wealth (Coibion et al., 2020). To make things worse, the economic outfall of the COVID-19 pandemic struck citizens on various dimensions quite differently. For one, the crisis creates two clusters between those with higher educational degrees who predominantly work in office-type jobs that can easily be managed from home during the lockdown, and another one which consists of people in manual labor with many daily social interactions or those who are regarded as “essential workers” (von Gaudecker et al., 2020; Mongey and Weinberg, 2020). Furthermore, the crisis has also a much higher impact on already poorer regions, as these have a much lower share of workers who can work from home (Irlacher and Koch, 2020). As the corona crisis increases existing inequalities and further deepens the gulf between rich and poor regions and citizens, it potentially reinforces polarization along existing cleavage lines (Kriesi et al., 2008).

Secondly, how the pandemic affects public opinion polarization may also be conditional on how elite communication fosters social recategorization. More specifically, if parties from both aisles unite around one issue, it is possible to “transform members' cognitive representation of the memberships from two groups to one group [...], from ‘us’ and ‘them’ to a more inclusive ‘we’” (Gaertner et al., 1993, 2–3). Thus, creating a superordinate ingroup identity of “us” against the coronavirus may shift the salience of political differences similar to other cases like wars or natural disasters (see further Achen and Bartels, 2016; Lenz, 2012). Yet, if political discourse becomes even more polarized on the issue of handling the corona crisis, this may very well intensify affective polarization on the micro level.

And to some degree, there is already evidence that these developments have substantial consequences in terms of how people perceive parties, politicians and government. On the one hand, we see that public opinion is deeply divided along partisan lines as to how countries ought to react to the COVID-19 pandemic. In the United States, Republicans believe that the pandemic is less severe and they are much less willing to engage in health protection measures like hand washing or social distancing (Allcott et al., 2020; Gadarian et al., 2020; Green et al., 2020). Similarly, the United Kingdom is also heavily polarized over media reports of the pandemic and government reaction to it. Those leaning left are much less likely to say that the government has done a good job in handling the pandemic and they are more likely to think that the media has not been critical enough of the government response (Nielsen et al., 2020).

Yet, there is also evidence that public opinion can shift into the opposite direction as response to the crisis, in particular in countries where the political arena speaks with one voice. Evidence from Canada shows that partisanship has no effect on social distancing, as there is cross-party consensus about how to handle the response to the pandemic (Merkley et al., 2020). Another cross-European study found that a lockdown can have positive effects on satisfaction with democracy, trust in government and support for the governing Prime Minister or President (Bol et al., 2020). Studying the local elections in Bavaria right before the lockdown in March 2020 Leininger and Schaub (2020) find no evidence of hostile sentiments in the form of stronger support for the right-wing populist AfD, but rather a sense of forward-looking motivation according to which voters opt for the party that is most likely to help them overcome the crisis. And even in the U.S. public reaction is partly shaped by who issues recommendation for response. Combining governors’ recommendations for residents to stay at home issued on Twitter with mobile phone mobility data Grossman and colleagues (2020) found that Democratic counties were actually more responsive to statements issued by Republican governors than were Republican counties. Thus, statements were most effective when signal and party position do not overlap (Chiang and Knight, 2011).

Major crises can turn into so called “critical junctures” or they can solidify the status quo depending on how political institutions perform and how citizens perceive such performance (Campbell, 2012; Bol et al., 2020). These mixed findings about reactions to the COVID-19 pandemic can thus be steered by elite cues. Prior research has shown that elite cues and polarized political debate can have a decisive impact on political attitude formation and voting behavior in normal times (Zaller, 1992; Mondak, 1993; Lupia, 1994; Druckman et al., 2013) or during electoral campaigns (Hansen and Kosiara-Pedersen, 2017) and intense or biased media coverage (Levendusky, 2013; Levendusky and Malhotra, 2016). However, there is little evidence about the influence of elite cues during a pandemic in which individual behavior affects not only political outcomes but also personal health (Grossman et al., 2020). I argue similarly that being affected by the corona crisis increases or decreases polarization based on whether there is cross-party consensus about how to handle the crisis best within a country. Whenever parties and politicians are heavily divided over how to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic, this will further increase social divides, as citizens perceive a strong political polarization and they are thus more likely to develop stronger negative attitudes towards partisans of other parties, too. However, whenever there is cross-party consensus, citizens will be more likely to notice such unity and harmony between parties that can positively shape individual out-group attitudes. This is also in line with earlier research which found that cross-cutting issue preferences, like in the case of personal health, can attenuate political hostility (Bougher, 2017). I thus hypothesize that polarization is likely to decrease following the outbreak of the corona crisis, if the political climate has witnessed more or less cross-party consensus about how to handle the crisis (H1).

Furthermore, earlier research from the financial crisis and Eurocrisis has shown that identity heuristics have become less important and utilitarian concerns about the effectiveness of the EU and benefits of integration much more important in times of economic threat (Hobolt and Wratil 2015; also Braun and Tausendpfund 2014; Braun et al., 2019; Daniele and Geys 2015). Thus, when the debate on European integration focused on economic aspects, a threat to one’s personal economic situation made it more likely for citizens to consider integration in terms of economic self-interest instead of national identity. Thus, being in a situation of personal financial distress makes people seek for economic solutions that are pragmatic and improve one’s own situation. In a certain way personal economic distress can act as a cold shower that brings citizens back to reality away from the theater of politics. Therefore, I expect that the relationship between national debate and affective polarization will become stronger whenever citizens are affected more strongly, as it increases the attention to politics in order to find out about potential solutions for improving one’s own situation (H2). The government provides more or less the only opportunity to issue instant financial help, e.g., through short-time allowances or immediate aid for small and medium-sized business owners. Thus, if people with economic distress listen more closely to what government does and more importantly how it communicates, such behavior can also translate into the perception of citizens.

3 Data and Method

A representative two-wave online panel survey was conducted in Germany between April 20 and May 5 (n = 1,670) and between July 23 and August 8, 2020 (n = 1,661) to discover how perceptions between partisans have changed due to the consequences of the pandemic.2 Of the respondents from wave 1 a total of 1,195 respondents also took part in wave 2. I selected Germany as a representative case for a country in which there is cross-party consensus about the corona crisis response measures like social distancing, the closing of schools and economic recovery programs at the onset of the pandemic. Initially, the right-wing populist AfD was much more quiet on the issue of handling the COVID-19 pandemic as compared to the financial crisis or the refugee crisis. Although somewhat critical at the beginning of the outbreak, the party issued a position paper that is mostly in line with other measures adopted by the government.3 Since then its stance has become much more sceptical though with party leaders heavily criticizing COVID-19 measures. Thus, it is a case where stronger economic distress due to the corona crisis should decrease political polarization at the beginning of the pandemic. Yet, once the AfD became more critical of it, I expect to find an increase in polarization yet again. Finally, using data from Germany also allows me to compare the findings to a previous study from 2017 so that I can investigate whether polarization has increased or decreased on average between groups over time.

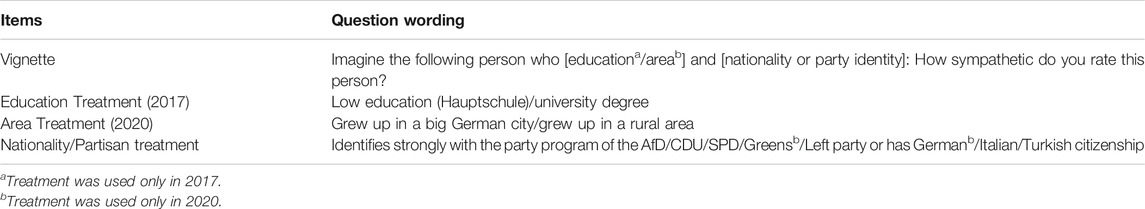

To achieve that, a vignette survey experiment was conducted in which each respondent was randomly presented with the description of a fictitious person with a different combination of partisanship and regional origin (see Table 1 or Supplementary Table S4 for detailed question wording). In line with earlier studies (see further Druckman and Levendusky, 2019), I measure affective polarization in terms of sympathy with citizens of varying party affiliation. This has the advantage to capture how affective polarization (and potentially social cohesion) is distributed within society and not between citizens and parties and politicians. To do so, respondents were asked, for instance, to “Imagine a person that grew up in a [rural area/big city]. The person identifies strongly with the party program of the AfD”. For parties I differentiated between CDU, SPD, the Greens, the Left Party and the AfD. That way I can assess how citizens evaluate their own partisan group and various other partisans. In line with the theoretical remarks from above, I am particularly interested in how sympathy evaluations between partisans of the right-wing populist AfD and mainstream party supporters unfold during the COVID-19 pandemic.

I also included additional treatments for foreign nationalities (Italians and Turks) as a reference in order to disentangle whether partisan polarization is as strong or stronger than polarization along national lines4. Afterwards, respondents were asked to rate that person on a thermometer scale ranging from very strong antipathy (−50) to very strong sympathy (+50).5 To assess the economic distress due the corona crisis on the cognitive load of respondents two questions were asked on five-point Likert scales about 1) whether the respondent currently thinks a lot about her economic situation and 2) whether thinking about his economic situation makes him anxious. I then created a mean index to build the main predictor variable.6 In addition, I use data from an earlier survey in Germany in October 2017 (n = 1,229) to compare the development over time (see for further description Helbling and Jungkunz 2020).7

4 Results

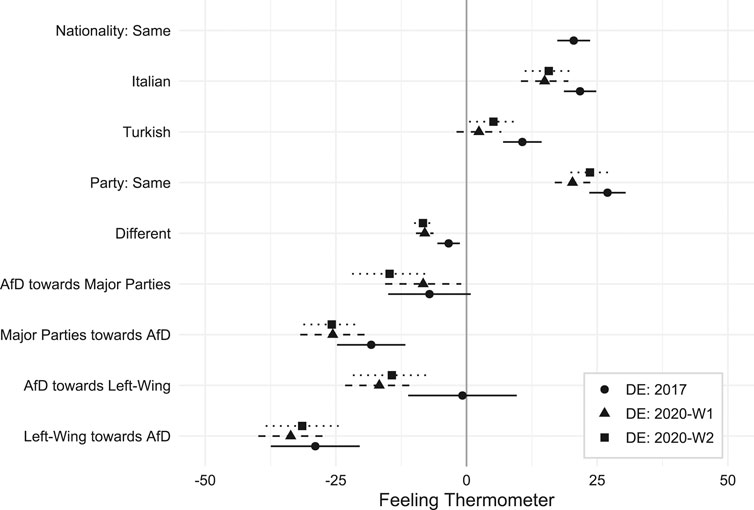

In a first step, I compare mean evaluations between various ethnic and partisan groups between 2017 and the 2020 waves in order to identify potential shifts in sympathy due the corona crisis. In sum, Figure 1 shows that the perception of different nationalities has changed only slightly for Italians, whereas Turks are rated about five to eight points lower as compared to 2017 (from +10.7 to +2.4 in wave 1 and +5.1 in wave 2).8 These shifts are significant between 2017 and 2020, but not between both waves in 2020. In terms of partisan polarization, the average sentiment for people leaning towards one’s own party went down slightly and not significantly (from +27.0 to +20.3) but recovered to +23.6 points in the second wave, which is about as favorable as people with one’s own nationality. Much lower we find the estimates for people rating partisans different from one’s own party, which have worsened significantly since 2017 (from −3.4 to −8.0 in wave 1) but remained more or less constant throughout the corona crisis (−8.4 in wave 2).

FIGURE 1. Comparison of Social Divides Across Time. Reported are mean values of the feeling thermometer variable by treatment groups with 95% confidence intervals. For interpretation: “AfD towards Major Parties” represents the sympathy of AfD voters towards supporters of CDU/CSU and SPD.

The most interesting finding results from the asymmetric comparisons between individual partisans. First, I find that the sympathy gap between AfD supporters and supporters of major parties (CDU/CSU and SPD) has increased substantially between 2017 and 2020 from a net point difference of 12.1 to 17.3, which is almost entirely due to the fact that the major party voters sympathize significantly less with AfD supporters (from −18.4 down to −25.6). This development can probably partly be attributed to the ongoing radicalization within the AfD leadership (Isemann and Walther, 2019), which worsened the stereotype of AfD supporters in the eyes of other partisans. It is important to note though that voters of the AfD do not experience stronger aversion towards major party supporters although parts of the party have radicalized even more in between both time points. Given that the AfD was more or less in line with the COVID-19 response measures issued by the government at that time, it indicates that cross-party consensus can potentially curb further affective polarization. Secondly however, I find quite the opposite development during the corona crisis. Between March and August 2020 the evaluation of major party voters towards AfD supporters remained more or less the same, whereas AfD voters showed a substantial (but not significant) decline in sympathy for major party supporters (from −8.3 down to −14.7 points). Once again, this could be attributed to a change in discourse by AfD elites who now openly support anti-corona demonstrations and try to position themselves as sharp critiques of the corona measures.9 As a result, this may have manifested in the minds of their supporters, too. Finally, I also find greater polarization between the ends of the political spectrum, as AfD voters show a strong and substantial (but not significant) decrease in sympathy for left-wing partisans (from −0.8 to −16.7 in wave 1 and −14.3 in wave 2) and vice versa (from −28.9 to −33.6 in wave 1 and −31.4 in wave 2).10 These differences are much smaller as compared to the development between major parties and the AfD though and there is barely any change during the course of the corona crisis. It is thus particularly interesting to look at how being economically affected by the corona crisis changes the evaluations of ethnic and partisan groups, which I will do in the next step.

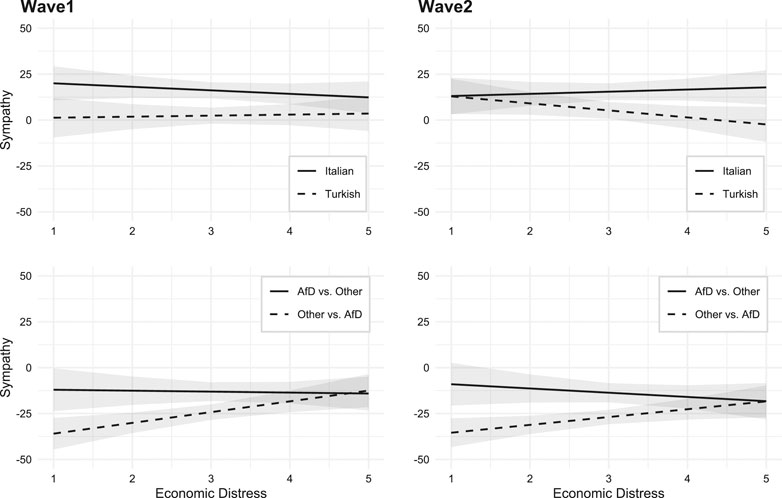

To do so, I estimated the effect of cognitive load due to economic distress through the corona crisis on the level of sympathy with various groups. In all models I control for education, sex and income. In the upper panel of Figure 2 it turns out that at the onset of the corona crisis higher distress does neither lead to substantially higher or lower sympathy for Italians or Turks. Whereas Turks remain around the midpoint of the scale, Italians are evaluated slightly worse from +19.5 down to +12.5 points, although this difference between respondents with high and low distress is not statistically significant. Thus, greater economic distress does not increase out-group animosity for ethnic minorities. This pattern changes in wave 2, where I find that there is no effect for Italians, but a downward trend for Turks from low (+12.9) to high distress (−2.4). Although this difference is significant only at the 90% level, there is a substantial and significant gap in the evaluation of Turks and Italians (+17.1) among respondents with high distress. Thus, it seems as if social divides between ethnic groups did not increase at the beginning of the corona crisis, but rather as its ramifications began to settle in.

FIGURE 2. Predictions of Economic Distress on Sympathy. Reported are predictions of the feeling thermometer variable with 95% confidence intervals. Economic distress ranges from very low (1) to very high (5).

A different picture occurs in the lower panel though. On the one hand, we see that the AfD voters perceive all other partisans more or less constant and somewhat negative at around −13 points in wave 1.11 On the other hand, there is a quite substantial and significant increase in sympathy from −35.9 to −12.5 points for voters of all other parties towards AfD partisans from very low to very high economic distress. One could argue that the cross-party consensus about how to handle the response to the pandemic has decreased the polarization of party rhetoric. Being affected more strongly by the crisis implies that people are also more aware and responsive to government action. The government provides more or less the only opportunity to issue instant financial help, e.g., through short-time allowances or immediate aid for small and medium-sized business owners. Thus, if people with economic distress listen more closely to what government does and more importantly how it communicates, such behavior can also translate into the perception of citizens. Those who support parties which are active in the public discourse of providing solutions to the corona crisis (which the AfD has silently done at this point in time) also decreases their negative perception of other partisans.12

This pattern also extends into wave 2. However, this time we also experience a small downward trend for AfD voters towards supports of other parties (from −9.1 down to −18.2). Although this is in line with the theoretical argument, earlier findings and the change in discourse within in the AfD,13 the difference is not significant, which could potentially be due to sample size. Finally, I ran robustness checks by estimating the effect of experiencing distress in wave 1 on the evaluation of ethnic minorities and partisans in wave 2. The results show similar patterns to what we see in the second wave in Figure 2 (see Supplementary Table S13).

5 Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic poses a fundamental challenge for states and citizens around the world. Besides the drastic effects on economic systems and the well-being of individuals it also poses ramifications for the interaction between citizens and politics. So far there is suggestive evidence that the way parties and politicians handle the response to the corona crisis also influences the polarization of public opinion (van Bavel et al., 2020). If political debate is heavily split over the urgency of the crisis and how to handle it best, this can lead to greater polarization, too. Unfortunately, the study cannot test how social divides unfold in a country where political discourse is very heavily polarized over the handling of the COVID-19 pandemic. Although the changing nature of political discourse in Germany between the AfD and other parties provides some evidence for my hypotheses, it requires further research under different political circumstances. Judging from other findings in the United States and Great Britain I would expect an increase in social divides, too. If, however, there is cross-party consensus and the political arena speaks with one voice, there is a chance to actually decrease affective polarization, particularly for those who are more preoccupied by the crisis. The results are in line with earlier research from Canada, where there has also been cross-party consensus on COVID-19 counter-measures (Merkley et al., 2020). Creating a superordinate identity that bridges existing cleavage and partisan groups might work to counter increasing polarization. On a greater perspective, this can provide a starting point for politics and further research as to how affective polarization can be mitigated.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/QCRDRO.

Ethics Statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

All work has been carried out by SJ.

Funding

This article is part of the research project “The influence of socio-economic problems on political integration” (PI: Paul Marx) funded by the North Rhine-Westphalian Ministry of Culture and Science.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Marc Helbling, Paul Marx and the two reviewers for their very helpful comments. I would also like to thank the Bamberg Graduate School of Social Sciences (BAGSS) for continuous support. I further acknowledge support by the Open Access Publication Fund of the University of Duisburg-Essen.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2021.622512/full#supplementary-material.

Footnotes

1Such processes are often driven by meso- and macro-level politicization and polarization, too (Hutter et al., 2016; Hutter and Kriesi, 2019). Yet, such developments are beyond the scope of the article and I will focus on perceptions between citizens on the individual level.

2The samples are representative in terms of sex, age and education. More information about sampling procedure and treatment assignment can be found in Supplementary Tables S1–S3, S5–S7 and section 3 in the Supplementary Material. The first wave of the study thus falls right into the period of the lockdown which started on March 22 and was lifted gradually from May 6 onwards.

3See e.g., https://www.afdbundestag.de/positionspapier-corona-krise/

4For the analyses I combined the treatments about education and regional origin, as this increases sample size and is not directly related to the research question.

5Unfortunately, respondents evaluated different persons in each wave, which is why I cannot estimate within-person shifts in sentiment over time.

6I also ran additional analyses using more objective indicators that asked about whether respondents think their current income is secure or whether they worry about their economic future. The results indicate a similar pattern compared to the findings presented here.

7The question wording differed slightly between that survey and the one presented here. The differences are reported in Supplementary Table S3 in the Supplementary Material.

8Full regression tables can be found Supplementary Tables S8–S12 in the Supplementary Material.

9See for instance https://www.tagesschau.de/inland/corona-demos-afd-101.html

10Due to a low number of cases I combined the vignettes of Greens and Left Party into left-wing. However, in 2017 Greens were not part of the vignette and left-wing represents Left-Party supporters only.

11In contrast to the time trends I combined all parties except the AfD into one group, as the pattern has been more or less the same and it improves the sample size for the analyses here. Estimating the effect for AfD vs. partisans of major parties and vice versa yields similar results.

12Potentially, this one-sided shift could also occur due to alternative explanations. For instance, it is possible that citizens who are more in contact with AfD voters (and thus have higher sympathy towards them) tend to be more preoccupied with their financial situation than those who have no contact with AfD partisans, e.g., because they live in areas that have been hit harder by the crisis. Although the data does not indicate substantial differences in terms of preoccupation among voters (see Supplementary Table S12 in the Supplementary Material), I cannot investigate such possibilities further and leave it to future research to disentangle such mechanisms.

13A current Politbarometer survey estimates that about 60 percent of the AfD supporters find the measure against the spread of the coronavirus excessive, whereas only about seven to 16 percent of all other partisans say so (https://ww.zdf.de/nachrichten/politik/politbarometer-coronavirus-grenzoeffnung-eu-100.html).

References

Achen, C. H., and Bartels, L. M. (2016). Democracy for realists: why elections do not produce responsive government. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Allcott, H., Boxell, L., Conway, J., Gentzkow, M., Thaler, M., and Yang, D. (2020). Polarization and public health: partisan differences in social distancing during the coronavirus pandemic. J. Public Econ. 191, 104254. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104254

Baldassarri, D., and Gelman, A. (2008). Partisans without constraint: political polarization and trends in American public opinion. Am. J. Sociol. 114, 408–446. doi:10.2139/ssrn.1010098

Bol, D., Giani, M., Blais, A., and Loewen, P. J. (2020). The effect of COVID‐19 lockdowns on political support: some good news for democracy?. Eur. J. Polit. Res. doi:10.1111/1475-6765.12401

Bougher, L. D. (2017). The correlates of discord: identity, issue alignment, and political hostility in polarized America. Polit. Behav. 39, 731–762. doi:10.1007/s11109-016-9377-1

Braun, D., and Tausendpfund, M. (2014). The impact of the Euro crisis on citizens’ support for the European Union. J. Eur. Integration 36, 231–245. doi:10.1080/07036337.2014.885751

Braun, D., Popa, S. A., and Schmitt, H. (2019). Responding to the crisis: eurosceptic parties of the left and right and their changing position towards the European Union. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 58, 797–819. doi:10.1111/1475-6765.12321

Campbell, A. L. (2012). Policy makes mass politics. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 15, 333–351. doi:10.1146/annurev-polisci-012610-135202

Chiang, C.-F., and Knight, B. (2011). Media bias and influence: evidence from newspaper endorsements. Rev. Econ. Stud. 78, 795–820. doi:10.1093/restud/rdq037

Coibion, O., Gorodnichenko, Y., and Weber, M. (2020). The cost of the COVID-19 crisis: lockdowns, macroeconomic expectations, and consumer spending. Cambridge, MA: NBER.

Daniele, G., and Geys, B. (2015). Public support for european fiscal integration in times of crisis. J. Eur. Public Pol. 22, 650–670. doi:10.1080/13501763.2014.988639

Druckman, J. N., and Levendusky, M. S. (2019). What do we measure when we measure affective polarization?. Public Opin. Q. 83, 114–122. doi:10.1093/poq/nfz003

Druckman, J. N., Klar, S., Krupnikov, Y., Levendusky, M., and Ryan, J. B. (2020). How affective polarization shapes Americans’ political beliefs: a study of response to the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Exp. Polit. Sci., 1–12. doi:10.1017/XPS.2020.28

Druckman, J. N., Peterson, E., and Slothuus, R. (2013). How elite partisan polarization affects public opinion formation. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 107, 57–79. doi:10.1017/S0003055412000500

Gadarian, S. K., Goodman, S. W., and Pepinsky, T. B. (2021). Partisanship, health behavior, and policy attitudes in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. SSRN Electron. J. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3562796

Gaertner, S. L., Dovidio, J. F., Anastasio, P. A., Bachman, B. A., and Rust, M. C. (1993). The common ingroup identity model: recategorization and the reduction of intergroup bias. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 4, 1–26. doi:10.1080/14792779343000004

Green, J., Edgerton, J., Naftel, D., Shoub, K., and Cranmer, S. J. (2020). Elusive consensus: polarization in elite communication on the COVID-19 pandemic. Sci. Adv. 6, eabc2717. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abc2717

Grossman, G., Kim, S., Rexer, J. M., and Thirumurthy, H. (2020). Political partisanship influences behavioral responses to governors’ recommendations for COVID-19 prevention in the United States. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 117, 24144–24153. doi:10.1073/pnas.2007835117

Hansen, K. M., and Kosiara-Pedersen, K. (2017). How campaigns polarize the electorate. Party Polit. 23, 181–192. doi:10.1177/1354068815593453

Helbling, M., and Jungkunz, S. (2020). Social divides in the age of globalization. West Eur. Polit. 43, 1187–1210. doi:10.1080/01402382.2019.1674578

Hobolt, S. B., and Wratil, C. (2015). Public opinion and the crisis: the dynamics of support for the Euro. J. Eur. Public Pol. 22, 238–256. doi:10.1080/13501763.2014.994022

Hobolt, S. B., Leeper, T. J., and Tilley, J. (2020). Divided by the vote: affective polarization in the wake of the Brexit referendum. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 66, 1–18. doi:10.1017/S0007123420000125

Hutter, S., and Kriesi, H. (2019). Politicizing Europe in times of crisis. J. Eur. Public Policy 26, 996–1017. doi:10.1080/13501763.2019.1619801

Hutter, S., Grande, E., and Kriesi, H. (2016). Politicising Europe: integration and mass politics. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Irlacher, M., and Koch, M. (2020). Working from home, wages, and regional inequality in the light of covid-19. J. Econ. Stat.

Isemann, S. D., and Walther, E. (2019). “Wie extrem ist die AfD? die entwicklung der afd und deren wählerschaft als radikalisierungsprozess,” in Die AfD—psychologisch betrachtet. Editors E. Walther, and S. D. Isemann (Wiesbaden, Germany: Springer), 157–177.

Iyengar, S., and Westwood, S. J. (2015). Fear and loathing across party lines: new evidence on group polarization. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 59, 690–707. doi:10.1111/ajps.12152

Iyengar, S., Sood, G., and Lelkes, Y. (2012). Affect, not ideology: a social identity perspective on polarization. Public Opin. Q. 76, 405–431. doi:10.1093/poq/nfs038

Iyengar, S., Lelkes, Y., Levendusky, M., Malhotra, N., and Westwood, S. J. (2019). The origins and consequences of affective polarization in the United States. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 22, 129–146. doi:10.1146/annurev-polisci-051117-073034

Jungkunz, S., and Helbling, M. (Forthcoming). Populist polarization in the age of globalization,” in The ideational approach to populism: consequences and mitigation. Editors N. Wiesehomeier, K. A. Hawkins, E. Hawkins, A. Chryssogelos, and L. Littvay (Cambridge, UK:Cambridge University Press).

Kriesi, H., Grande, E., Lachat, R., Dolezal, M., Bornschier, S., and Frey, T. (2008). West European politics in the age of globalization. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Leininger, A., and Schaub, M. (2020). Voting at the dawn of a global pandemic. Working Paper. doi:10.31235/osf.io/a32r7

Lenz, G. S. (2012). Follow the leader? How voters respond to politicians’ policies and performance. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Levendusky, M., and Malhotra, N. (2016). Does media coverage of partisan polarization affect political attitudes?. Polit. Commun. 33, 283–301. doi:10.1080/10584609.2015.1038455

Levendusky, M. (2013). Partisan media exposure and attitudes toward the opposition. Polit. Commun. 30, 565–581. doi:10.1080/10584609.2012.737435

Lupia, A. (1994). Shortcuts versus encyclopedias: information and voting behavior in California insurance reform elections. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 88, 63–76. doi:10.2307/2944882

Mason, L. (2015). “I disrespectfully agree”: the differential effects of partisan sorting on social and issue polarization. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 59, 128–145. doi:10.1111/ajps.12089

Mason, L. (2018). Ideologues without issues: the polarizing consequences of ideological identities. Public Opin. Q. 82, 866–887. doi:10.1093/poq/nfy005

Medeiros, M., and Noël, A. (2014). The forgotten side of partisanship. Comp. Polit. Stud. 47, 1022–1046. doi:10.1177/0010414013488560

Merkley, E., Bridgman, A., Loewen, P. J., Owen, T., Ruths, D., and Zhilin, O. (2020). A rare moment of cross-partisan consensus: elite and public response to the covid-19 pandemic in Canada. Can. J. Pol. Sci. 53, 311–318. doi:10.1017/s0008423920000311

Mondak, J. J. (1993). Public opinion and heuristic processing of source cues. Polit. Behav. 15, 167–192. doi:10.1007/bf00993852

Mongey, S., and Weinberg, A. (2020). Characteristics of workers in low work-from-home and high personal-proximity occupations. Chicago, IL: Becker Friedman Institute White Paper.

Nielsen, R. K., Kalogeropoulos, A., and Fletcher, R. (2020). UK public opinion polarised on news coverage of government coronavirus response, and concern over misinformation. Oxford, UK: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

Reiljan, A. (2020). “Fear and loathing across party lines” (also) in Europe: affective polarisation in European party systems. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 59, 376–396. doi:10.1111/1475-6765.12351

Tajfel, H., and Turner, J. C. (1979). “An integrative theory of lntergroup conflict,” in The social psychology of intergroup relations. Editors W. G. Austin, and S. Worchel (Monterey, CA: Brooks/Cole), 33–47.

van Bavel, J. J., Baicker, K., Boggio, P. S., Capraro, V., Cichocka, A., Cikara, M., et al. (2020). Using social and behavioural science to support COVID-19 pandemic response. Nat. Hum. Behav. 4, 460–471. doi:10.1038/s41562-020-0884-z

von Gaudecker, H.-M., Holler, R., Janys, L., Siflinger, B., and Zimpelmann, C. (2020). Labour supply in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic: empirical evidence on hours, home office, and expectations. Bonn, Germany: IZA Discussion Paper No, 13158.

Wagner, M. (2021). Affective polarization in multiparty systems. Elect. Stud., 69, 102199. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2020.102199

Keywords: COVID-19, polarization, attitudes, affective, Germany

Citation: Jungkunz S (2021) Political Polarization During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Polit. Sci. 3:622512. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2021.622512

Received: 28 October 2020; Accepted: 14 January 2021;

Published: 04 March 2021.

Edited by:

Matt Henn, School of Social Sciences, Nottingham Trent University, United KingdomReviewed by:

Federico Vegetti, University of Turin, ItalyDaniela Braun, Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, Germany

Copyright © 2021 Jungkunz. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sebastian Jungkunz, c2ViYXN0aWFuLmp1bmdrdW56QHVuaS1kdWUuZGU=

Sebastian Jungkunz

Sebastian Jungkunz