94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Polit. Sci., 14 April 2021

Sec. Political Participation

Volume 3 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2021.611824

This article is part of the Research TopicThe Civic and Political Participation of Young People: Current Changes and Educational ConsequencesView all 6 articles

It has been widely argued that effective citizenship education should focus on more than mere teaching of civic knowledge, but should provide a wider range of opportunities for the experience of participation and development of skills, efficacy and interest instrumental to active citizenship. Opportunities for critical reflection such as open classroom discussions, fairness at school, institutional efficacy and student participation at school activities have been linked to the development of civic and political attitudes. The capacity of school education to provide opportunities for critical reflection on students’ participative experiences, however, has not been explored empirically sufficiently. This paper aims to identify the contribution of different school characteristics to the development of civic and political attitudes and their impact on students’ level of participation in civic activities through a mixed methods study. Questionnaire data collected in two waves with 685 adolescents from Italy were analyzed through structural equation modeling to test the effects of school characteristics at Time 1 (democratic climate, student participation and critical reflection) on civic participation at Time 2, mediated by institutional trust, civic efficacy and political interest. In order to explore the quantitative findings and examine further students’ perceptions of the school aspects that support their civic involvement, focus group discussions were conducted with students from secondary schools with different tracks.The results highlight the importance of opportunities for active involvement in school and critical reflection in fostering political interest, efficacy and civic participation. Democratic school climate was found to impact institutional trust and civic efficacy, but not participation. Students’ accounts of schools’ citizenship education activities highlight further the need for a participative environment that rises above information transmission by inviting critical reflection and giving value to students’ active involvement in the institution.

The school’s role in shaping young people’s civic and political sense is pivotal as an institution that is capable of reaching the majority of youth with a clear educational agenda aimed at acquiring civic skills and knowledge (Niemi and Junn, 1998; Schulz et al., 2010).

Beyond the formal curriculum, however, both structural and perceived characteristics of schools can influence adolescents’ civic development. The existing literature has argued that effective citizenship education focuses on more than the mere teaching of civic knowledge and provides opportunities for participation that foster the development of civic skills and efficacy (Haste, 2004). The experience itself of citizenship in the school context is central as “young people learn to be citizens as a consequence of their participation in the actual practices that make up their lives” (Lawy and Biesta, 2006, p. 45). The school, then, can be seen as a microcosm in which public life is exercised daily.

Opportunities for democratic experience in school can be understood within an ecological systems framework (Bronfenbrenner, 1979) as positive contextual characteristics that interact with individual ones and other contexts in shaping young people’s civic development. While they do not operate independently of macro and social predictors, the importance of perceptions of the educational contexts and the mediating role of psychological factors in predicting behavior has been underlined in recent integrative models of civic and political participation (Barrett, 2015; Barrett et al., 2015; Barrett et al., 2019). Adolescents construct ideas of themselves as citizens and of civic processes within the everyday interactions with significant others and with the communities, organizations and institutions of which they are part of. Assuming that youth have resources and are capable of being actors in this process requires that their views are taken seriously over how contextual opportunities can best facilitate its enactment (Shaw et al., 2014). Understanding the capacity of participative opportunities in citizenship education, therefore, entails examining young people’s perceptions of these interactions with school characteristics that can provide practical experience of democratic citizenship.

In this framework, the present research seeks to extend existing research on adolescents’ civic engagement by examining the role of students’ perceptions of school and classroom democratic characteristics in fostering civic attitudes and behaviors. In particular, we are interested in the processes with which students’ experience of democracy at school may influence civic behavioral activation through the increase of key psychological factors such as interest, efficacy and trust over time. Moreover, we seek to further understand possible mechanisms and limitations in these processes from the perspective of students themselves. The research will contribute to existing literature by addressing the role of multiple perceived democratic opportunities at school and their specific input to students’ civic development. In order to tap into adolescents’ views and experiences at school we employ a mixed methods approach combining in a sequential design a two-wave questionnaire at a one-year interval and focus groups with Italian students in upper secondary schools. First, a quantitative study seeks to assess the impact of perceived democratic school characteristics on civic participation at a one-year interval and the role of psychological factors in this process through a structural equation model. Second, a qualitative study further explores adolescents’ perspectives on how these school characteristics influence their civic development and what are their experiences of the barriers and opportunities for participatory citizenship education.

Democratic experiences entail involving students in school governance and in deliberative and participative activities, providing empowering spaces in which they have a voice and are recognized as social agents with claims and interests (Lawy and Biesta, 2006; Cockburn, 2007). School settings, in which youth can participate in relevant discussions, exercise informed judgment and criticize the status quo are seen as crucial in an approach that focuses on facilitating political abilities: “interest in political issues tends to be generated by controversy, contestation, discussion, and the perception that it matters to take a stand” (Flanagan and Christens, 2011, p. 2).

School characteristics that can be related to developing such competences include democratic school climate, active participation in school-based activities and critical reflection on one’s participative role. The experience of these aspects is often outside of formal curriculum and is a result of dialogue and self-reflection (Scheerens, 2011). Democratic school climate, which has been given particular importance in literature on civic engagement, is promoted when students feel that there are opportunities for open discussions in the classroom, that they can take part in school decision-making and that they are treated fairly at school (Ehman, 1980; Torney-Purta, 2002; Eckstein and Noack, 2014; Lenzi et al., 2014). Having influence in school decisions and feeling that one’s opinions are valued is part of the experiences of democracy within school that can influence future civic and political attitudes (Flanagan, 2013; Nieuwelink et al., 2016). Student participation at school can be offered by means of student elections and councils, extra-curricular activities, student projects, networks, etc. (Flanagan et al., 2007; Scheerens, 2011). While these experiences offer the possibility to practice participation and learn democratic competences, it is also important to consider their quality and their capacity to effectively foster meaningful engagement and reflection. According to some authors citizenship education should promote critical reflection and empower youth to articulate their needs (Hedtke, 2013). The quality of participative experiences in citizenship education can be determined by the dimensions of action and reflection, which should be combined in learning opportunities in order to provide a supportive environment for expressing dissent, valuing pluralism and analyzing personal meanings (Fernandes-Jesus et al., 2012; Ferreira et al., 2012). It is argued that schools should provide activities of citizenship education that focus attention on the process of thinking critically about social reality and complex problems in order to promote active citizenship (Piedade et al., 2020). The contribution of perceived critical reflection at school to the promotion of civic participation, however, has received limited attention in empirical research in comparison to democratic school climate and student participation. The presented studies address this gap by examining the relationship between all these aspects of students’ school-related perceptions, civic attitudes and behaviors, while elucidating specificities and limitations in students’ experiences.

Existing research has evidenced that among the psychological factors that contribute to the process of engaging in civic participatory behaviors, cognitive resources related to civic and political domains are particularly important: these include internal and collective efficacy, political and societal interest, institutional trust (Barrett, 2015; Barrett et al., 2019). Perceptions of being able to understand and participate effectively in politics, to influence public decisions, to be able to contribute to collective decision-making processes and social change are considered necessary to develop the motivation to act and engage concretely (Hahn, 1998; Pasek et al., 2008; Sohl and Arensmeier, 2015). Young people’s sense of efficacy can be promoted by school experiences, in particular with respect to the degree to which students feel capable to participate in their school’s governance. In this sense, the value that the school attributes to the participation of students can strengthen their beliefs in the usefulness of collective and democratic commitment in general (Schulz et al., 2010). Political and societal interest is also considered crucial in characterizing youth who are involved latently (Ekman and Amna, 2012) and it is an important precursor of future participation (Prior, 2010; Russo and Stattin, 2017; Wanders et al., 2020). For Emler (2011), interest is the initial factor that leads to participation through a process of opinionation. In this process, education assumes an important role as a social environment that can provide exposure and facilitate discussion on civic and political issues. Activities in citizenship education should therefore be able to engage students by fostering interest in the issues on which they could act. However, few studies have been conducted on how different democratic characteristics of schools can specifically arouse civic and political interest. Another psychological aspect that has been linked to citizenship education and to civic engagement is institutional trust–the belief that political and governmental institutions are trustworthy. Indeed, education policies and goals are often aimed at producing institutional support and consequent “conventional” participation by young citizens, as evidenced in the European community (Hedtke, 2013). However, trust in institutions seems to be related to political activities such as voting and party activity, but it is negatively associated with more critical forms such as protesting and signing petitions (Brunton-Smith, 2011; Hooghe and Marien, 2013).

Previous empirical evidence has shown that democratic school climate promotes civic knowledge, attitudes and participation through the encouragement of open civic discussions in the classroom (i.e., open classroom climate; Torney-Purta, 2002; Torney-Purta and Barber, 2005; Kahne and Sporte, 2008; Geboers et al., 2013). Other important elements for developing civic responsibility and engagement by democratic school climate are the promotion of students’ decision-making power on issues and rules within their school (Torney-Purta et al., 2001; Quintelier and Hooghe, 2013; Lenzi et al., 2014) and the perception of fair treatment at school (Lenzi et al., 2014; Resh and Sabbagh, 2017). The existing research has shown that open classroom climate also contributes to the development of institutional trust (Claes et al., 2012; Dassonneville et al., 2012; Barber et al., 2015). Moreover, the feeling of being treated fairly generally brings to consider authority as more trustworthy (Tyler and Smith, 1999). Some empirical evidence suggests that the democratic school climate increases perceptions of political effectiveness among students (Pasek et al., 2008), especially through open classroom climate (Godfrey and Grayman, 2014; Barber et al., 2015). There is little and less strong evidence on the impact of democratic school climate on political interest (García-Albacete, 2013).

Opportunities for active learning have also been shown to lead to greater civic participation in the future (Davies et al., 2013; Davies et al., 2014). Kahne and Sporte (2008) found that, even taking into account previous levels of civic engagement, opportunities to act directly on civic and political issues at school have a significant impact on adult participation. Participating in school councils has also been shown to predict higher trust in institutions and political interest (Claes and Hooghe, 2017). Hoskins et al. (2012) found positive relationships between participation in school boards and participatory attitudes, suggesting that being a school representative and being elected can contribute to experiencing a participatory school culture that reinforces sense of efficacy.

Schools and educational contexts can also be pivotal in offering experiences of reflective action, i.e., praxis (Freire, 1970). Focusing on the quality of participation experiences, the opportunity for both action and critical reflection can increase civic participation among youth (Fernandes-Jesus et al., 2012; Ferreira et al., 2012). There is, however, lack of research on the psychological processes promoted by the experience of critical reflection at school and on their impact on civic behaviors.

The research was conducted in North-East Italy. In particular we involved upper secondary school in the Emilia Romagna region. The level of civic participation in Italy is relatively low with respect to other European countries according to data from Eurostat (2015). Among Italian young people between 16 and 29 years in 2015 the rate of participation in formal voluntary activities was more than 5% lower than the general EU rate (14.2% vs. 19.3%), while for informal voluntary activities the difference was even bigger (11% in Italy vs. 22.4% in the EU). These statistics point to conditions of low opportunity for involvement by young people and highlight the important mission of schools in providing more effective citizenship education and spaces for participation.

In the Italian context, citizenship education has been understood as a transversal task for all subjects and the last decade has seen important transformations in the way in which education policies have sought to implement it on a national level, while integrating European recommendations (Bombardelli and Codato, 2017; Albanesi, 2020). A series of educational reforms since 2008 introduced the cross-curricular topic of “Citizenship and constitution” with a high degree of school autonomy in implementing it as a learning objective in the teachings of several common subjects (e.g., history, law, geography, etc.). The most recent educational reform (Law 92/2019), accepted after the data collection of the present study, established mandatory civic education as a separate subject in primary and secondary school. These changes have brought to an environment of debate over the reforms’ implementation and difficulties for adequate training and organization of suitable methods for student participation (Losito, 2009; Ambel, 2020). It is thus important for empirical research to gain better understanding of the participative and democratic opportunities that schools in Italy offer and can offer in a better way.

When it comes to extra-curricular activities and participation in decision-making bodies, students in Italian upper secondary schools can participate as representatives in class or school councils as recognized by the Ministry of Education for all types of schools. They also have the right to organize student assemblies and committees as structures for participation. Other activities in clubs or groups may vary according to each institution. With respect to other contexts, however, Italian schools do not offer mandatory service-learning or community service activities.

Citizenship education curricula and laws in Italy are defined at a national level and do not present substantial regional differences. Including different school tracks is crucial in order to ensure adequate variability in terms of socio-economic context, since the choice of school track in Italy is often related to socio-economic background and a vertical hierarchy of prestige and quality, which sees vocational schools at the bottom (e.g., Triventi, 2014). For example, in 2015, 28.8% of students in higher school tracks had at least one parent with a university degree, while this rate decreased to 4.6% in vocational institutes (ISTAT, 2017).

For this reason, we involved schools with different tracks (academic, technical and vocational) and in different territorial contexts: large and small cities, rural settings. The schools were chosen to represent different diverse educational contexts with possibly different resources. We collected questionnaire data in six schools, and we conducted focus groups in four of these, adding an additional mixed track school. Two schools represented the general academic track (i.e., liceo); one school offered mixed general and technical tracks; two schools represented the technical track; finally, one school was vocational.

We employ a mixed methods sequential research design to conduct the two studies (Creswell, 2014). The use of both quantitative and qualitative data was aimed at gaining a deeper understanding of adolescents’ experience of democratic school characteristics and the processes through which they can impact civic engagement. The first study sought to test a mediation model of the impact of the aforementioned school characteristics on civic participation at a one-year interval in a sample of Italian upper secondary school students. The second study sought to further explore adolescents’ perspectives on how democratic school characteristics influence their civic development with the help of focus groups in a subsample of students. We present the methods and results for each study and discuss the overall findings in the final section.

Past research has investigated different school characteristics as explanatory variables of attitudes and behaviors related to civic engagement. However, contributions analyzing multiple democratic experiences and the processes that could explain the promotion of active participation are rare. Moreover, such research has been limited to predicting expected future participation rather than levels of actual participation (e.g., Lenzi et al., 2014; Castillo et al., 2015; Manganelli et al., 2015). In the present study we investigate how perceived democratic school characteristics (democratic school climate, student participation and critical reflection at school) could promote civic participation through the increase of institutional trust, efficacy beliefs and political and social interest, while controlling for classroom-level clustering.

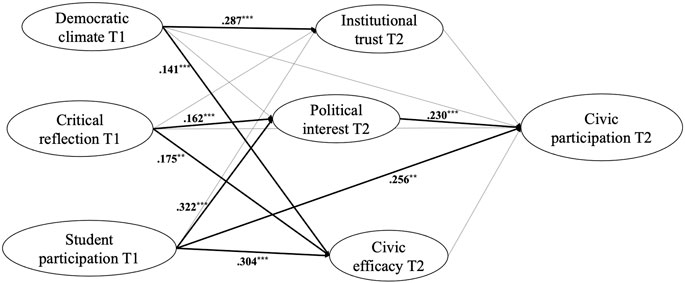

The conceptual model and corresponding hypotheses are presented in Figure 1. We adopt the use of temporally separated measures, with the advantage to reduce common method bias (Podsakoff et al., 2012). The model evaluates the following pathways.

Firstly, perceiving higher democratic school climate at Time 1 is hypothesized to be directly related to higher civic participation at Time 2 (H1). We also expect that greater civic participation at Time 2 is predicted by perceiving to have more experiences of critical reflection at school at Time 1 (H2) and by student participation at school at Time 1 (H3).

Moreover, the role of institutional trust, civic efficacy and political interest as mediators between school characteristics and civic participation is evaluated. It is thus expected that higher democratic school climate predicts higher institutional trust at Time 2 (H4), higher civic efficacy beliefs at Time 2 (H5), and higher political interest at Time 2 (H6). We also hypothesize that higher critical reflection at school at Time 1 is positively related to institutional trust at Time 2 (H7), civic efficacy at Time 2 (H8), and political interest at Time 2 (H9). Student participation at school at Time 1 is also expected to predict higher institutional trust at Time 2 (H10), higher civic efficacy at Time 2 (H11), and higher political interest at Time 2 (H12). In turn, we expect that civic participation at Time 2 is influenced positively by higher institutional trust at Time 2 (H13), higher civic efficacy at Time 2 (H14), and higher political interest at Time 2 (H15).

The data was collected within the European-funded H2020 research project CATCH-EyoU (Grant Agreement 64538). We obtained ethical approval for this study from the Bioethics Committee of the University of Bologna.

The study presents questionnaire data collected in two waves at a one-year interval–in 2016 and in 2017 (Cicognani et al., 2012). The instrument was constructed by the CATCH-EyoU consortium (Noack et al., 2017). In order to adapt the instrument, all measures were translated in Italian by two translators and differences were reconciled by both together with the research team. A back translation was made by an independent translator and discrepancies were examined and resolved by the team. A pilot assessment on a sample of 101 adolescents was conducted prior to the principal data collection in order to arrive at a reliable, parsimonious and valid questionnaire.

Adolescents from upper secondary schools in North-East Italy, aged between 14 and 19 years old, filled out a self-report questionnaire mostly on paper (91.8%), as well as online (8.2%).

The possibility to participate to the research was announced through the Psychology department’s website. The first contact was made with the headmaster and reference teachers from the selected schools. After a formal agreement, the participation in the study was proposed as a school project to entire classes (3rd and 4th year)—four classes per school. No students refused to participate. Questionnaires were completed, either on paper or online, under the supervision of a researcher and/or a teacher during a class hour. Participation consent forms were collected prior to distribution from all students and, in the case of underage participants, also from parents.

The final sample consisted of 685 students (AGE = 16.4; 50.7% female, 49% male, 0.3% responded “other”). Students coming from a higher school track (academic or technical) were 86.4% of the sample.

The independent variables were all measured at Time 1 (T1). The mediators and the outcome were measured one year later at Time 2 (T2). Detailed report of the measures and items is found in Supplementary Material. Moreover, school track, age, sex and perceived family income were controlled for.

Participants were asked to report their age, sex and perceived family income (“Does the money your household has cover everything your family needs?”).

Perceived democratic school climate was assessed with seven items measured on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). The items measured: open classroom climate (adapted from the IEA ICCS study; Schulz et al., 2010; e.g., “Teachers respect our opinions and encourage us to express our opinions during the classes”); school external efficacy (e.g., “Students at our school can influence how our school is run”); and perceived fairness of teachers and of the school’s rules (two items from the Teacher and Classmate Support Scale; Torsheim et al., 2000; e.g., “Our teachers treat us fairly”). The reliability of the scale was very good (α = 0.82).

Critical reflection at school was measured by four items on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). These corresponded to the dimension of reflection within the Quality of Participation Experiences Scale which regards opportunities facilitating reflection through discussion of different perspectives, everyday life issues and integration of conflicting opinions (Ferreira et al., 2012; e.g., “During that time, I have. observed conflicting opinions that brought up new ways of perceiving the issues in question.”). The reliability of the scale was good (α = 0.74).

Student involvement in different school-based opportunities was assessed, including representative and extra-curricular activities, in line with indicators of informal learning proposed by Scheerens (2011). Participants were asked whether in the past year they: had represented other students in student councils or in front of teachers or principals; had been active in a student group or club; had been active in a school sports group or club. Answers were dichotomous (yes/no).

Institutional trust was measured by two items assessing trust in European and national institutions (e.g., “I trust the national government”). Both were measured on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). The reliability was below the commonly accepted threshold of 0.7 (α = 0.61), however given the low number of items, the explorative research aims and the use of SEM-based measurement we consider it sufficient (cfr. Cho and Kim, 2015).

Interest in politics, European and national politics, and societal issues was measured by four items on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = not at all to 5 = extremely), adapted from Amna et al. (2010). An example was “How interested are you in politics?”. The reliability of the scale was very good (α = 0.83).

In order to assess civic efficacy, we measured youth’s collective efficacy and their internal civic efficacy. Two items adapted from Barrett et al. (2015) assessed collective efficacy (e.g., “I think that by working together, young people can change things for the better”). Three items adapted from Russo and Stattin (2017) measured internal civic efficacy defined as the belief in being able competently to participate in political action (e.g., Levy, 2013). An example was “If I really tried, I could manage to actively work in organizations trying to solve problems in society”. The reliability of the scale was good (α = 0.79).

Participation in civic activities in the last 12 months was measured on a 5-point scale (1 = no to 5 = very often) with 4 items from the Civic and Political Participation scale (CPP; Enchikova et al., 2019; Noack et al., 2017). An example was “Volunteered or worked for a social cause”. The reliability of the scale was below the commonly accepted threshold of 0.7 (α = 0.60), however given the low number of items, the explorative research aims and the use of SEM-based measurement we consider it sufficient (cfr. Cho and Kim, 2015).

In order to test the model, we performed a structural equation modeling (SEM) with a robust weighted least squares estimation (WLSMV) in Mplus (Muthén and Muthén, 2015). The analysis took into account the nested structure of the data according to classrooms. In particular, standard errors and a chi-square test of model fit were computed taking into account clustering, using a sandwich estimator for standard error computation. The scales’ items were inserted as observed measures of the hypothesized constructs. We estimated the structural model with: democratic school climate, critical reflection and student participation as predictor latent variables; institutional trust, civic efficacy and political interest as endogenous mediator latent variables; and civic participation as endogenous latent outcome (Figure 1). Age, sex, perceived family income and school track were included as observed control covariates.

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for the variables under investigation.

The measurement model provided a good fit to the data: χ2(329) = 730.17; p < 0.001; CFI = 0.943; TLI = 0.934; RMSEA = 0.042. Table 2 provides the correlations between the latent constructs.

The structural model fitted the data well: χ2(425) = 829.03; p < 0.001; CFI = 0.941; TLI = 0.932; RMSEA = 0.037. Figure 2 reports the results of the test of the hypothesized mediation model.

FIGURE 2. Results of the SEM analysis. Parameter estimates are standardized. Dashed lines represent not significant relationships. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

The results show that civic participation is predicted at a one-year interval directly only by student participation and political interest. Democratic school climate and critical reflection at school measured at T1 did not have significant direct effects on civic participation at T2. Democratic school climate at T1 showed positive influence on institutional trust and civic efficacy at T2, while critical reflection and student participation lead to greater political interest and civic efficacy after one year.

Student participation at school also presented a significant indirect effect on civic participation through its influence on political interest (ß = 0.07; p < 0.01). Critical reflection at school also had a small significant indirect effect on civic participation via political interest (ß = 0.04; p < 0.05). The impact of critical reflection on civic activity was, thus, fully mediated by the increase in political interest.

Moreover, sex as a covariate was significantly associated with civic participation (ß = −0.13; p < 0.01) and institutional trust (ß = −0.15; p < 0.01). Female participants showed higher civic activity and trusted institutions more than male students. The result is in line with previous research that has observed greater participation of women with respect to men, including among young people, in civic activities like volunteering, community service or donating (e.g., Gaby, 2017; Stefani et al., 2021). These differences can be interpreted as partly resulting from gendered socialization (Albanesi et al., 2012; Cicognani et al., 2012; Stefani et al., 2021), as women tend to be oriented toward gender roles characterized by cooperation, rule-abiding and helping (Eagly et al., 2000).

Higher perceived family income was associated positively with institutional trust (ß = 0.21; p < 0.001). Age did not have significant effects on the endogenous variables. Finally, being a student in higher school tracks led to greater civic participation (ß = 0.16; p < 0.001), as well as to having higher interest (ß = 0.20; p < 0.001) and efficacy levels (ß = 0.13; p < 0.001).

Overall, controlling for classroom clustering, the results confirmed the importance of active student participation in school activities as a predictor of civic participation, as it had both a substantial direct effect and a mediated impact through the promotion of political interest (hypotheses H3, H12 and H15). Thus, students were more engaged in civic participation after one year when they had taken part in extracurricular activities such as class and school councils or student groups and clubs. These findings point to the relatively higher importance of practical involvement in school activities for the promotion of civic behavior with respect to other perceived school characteristics.

The presence of a partial mediation effect of political interest for student participation was thus supported. Critical reflection at school showed only a mediated effect on civic participation through the increase of political interest (H9 and H15). Along with student participation, the experience of opportunities for critical reflection at school also seem to foster future civic engagement, to a limited degree, through the increase of political and societal interest. Hence, the main psychological pathway through which democratic school experiences bring about greater civic participation among students is the promotion of interest in current issues in the civic and political sphere.

However, while showing important impact on institutional trust and civic efficacy, democratic school climate did not seem to influence civic participation at a one-year interval as hypothesized. The findings suggest that democratic school climate, in which there are opportunities for open discussions in class, student involvement in decision-making and fair treatment, foster some cognitive resources related to young people’s civic confidence in institutions and their own capabilities of having an impact. These resources, however, do not seem to be sufficient in increasing actual civic behavior within the year in which data was collected. The findings will be discussed in light of the existing literature in the final discussion section, along with findings from the second study.

In order to further elucidate students’ experiences and gain a deeper understanding of the impact and processes of civic activation through practical and informal citizenship education, we explore students’ perspectives on how school characteristics influence their civic and political development. We seek to further understand possible mechanisms and limitations in these processes from the perspective of students themselves in a qualitative study, in order to also make sense of the quantitative results. The aim is to shed light on how upper secondary school students in the Italian context describe the role of school characteristics outside of the formal curriculum in fostering their civic engagement; which aspects can be identified in their experiences–e.g., democratic school climate, critical reflection, opportunities for involvement; and what limitations they point out. To explore young people’s visions in a qualitative approach we used focus group discussions–a method that uses group interaction to generate data and insights (Flick, 2014).

The data was collected within the European-funded H2020 research project CATCH-EyoU. The study was approved by the Bioethics Committee of the University of Bologna.

Data was collected between February and April 2017 in five schools in North and Central Italy regions with two focus group discussions per school (Cicognani and Menezes, 2021). We contacted four of the schools, in which the survey in Study 1 was collected, and an additional one for a total of five schools. In each school the recruitment of students was mediated by a referent teacher according to specific guidelines for the choice of research participants. We sought to recruit about 15–20 students per school from upper secondary classes, who were as much as possible involved in projects or activities organized by the school that promote active citizenship or may be considered forms of youth participation (including school activities, such as working in the school newspaper, being a member of a school sports team, etc.). Participants were requested to read and sign an informed consent form prior to participating (for minors the consent was preliminarily asked also to parents).

Each focus group had 9 to 12 participants (see Table 3). Overall, the study involved 10 focus group discussions with a total of 101 students, aged between 16 and 20 years old (58.4% were female, 41.6% were male).

The focus groups were all conducted in the schools and they were facilitated by a moderator and a co-moderator, both researchers. The discussion started with an ice breaking activity, by showing images of youth participation, whose aim was to facilitate students’ understanding of some of the topics that would be discussed with them and to facilitate the discussion. Subsequently the focus groups followed a semi-structured guide of topics, in which moderators left the discussion flexible and open for interaction and intervened only to ask for further clarification or to redirect the conversation to the topics of interest. Participants were prompted to talk about their ideas and experiences of civic and political participation, their connection to national and European institutions, and the role played by the school in promoting these experiences. The discussion of schools’ role was aimed at tapping into participants’ learning processes within developmental contexts, in particular the school. They were prompted, if the topic did not arise spontaneously, to discuss and give significant examples about whether they talked about civic and political issues at school and with whom, how they learned about these topics, in what kind of activities. The guiding questions relative to the topic of school, analyzed in the present study, are provided in Supplementary Material. Further information is available from the authors upon request.

The focus group discussions were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Thematic content analysis was used with the help of Nvivo 10 software: “Thematic analysis is a method for identifying, analyzing and reporting patterns (themes) within data” (Braun and Clarke, 2006, p. 79). All data was organized in the framework of Nvivo and conversation turns were systematically coded with a combination of top-down and bottom-up strategies. The approach taken was recursive with progressive refinement of the thematic categories and continuous re-examination of the data in a procedure inspired by grounded theory methodology (Glaser and Strauss, 1967). We present the results related to discussions of schools’ role in promoting civic engagement through democratic experiences, in particular. Additional findings are available from the authors upon request.

Overall, students highlighted throughout all discussions that educational institutions should have a central role in fostering their citizenship skills, in informing them about relevant issues and in giving them opportunities for participation. Participants focused spontaneously on aspects beyond the formal curricula and teaching methods by emphasizing the relevance of discussions in class, teachers’ personal approach, opportunities for reflection and extra-curricular activities. The emerging themes did not differ substantially between discussions in schools with different tracks. In the following sections we highlight if particular topics within the general theme emerged in a specific school context.

Many students highlighted that the development of autonomy and independence of thought was at the center of their growth toward becoming active citizens who could contribute to a better society.

Instead I must be an active person, I must know, I must get involved in expressing my opinion, in the right ways, in order to improve what isn’t acceptable around me. […] it is important to be active for those reasons–to have a better future and to have your say, build it yourself the better future, because it doesn’t just come about to us. (FG10).

At the basis of such development, according to participants, was the need to be informed and aware of the social issues that they could contribute to and of the ways in which they could effect change. In this sense, students’ accounts evidenced the need of an education that supports critical awareness, reflection and free expression. Participants in many cases saw their experience in school as lacking on these aspects, which was believed to be a major constraint toward participation.

I mean, I have no idea what I can do, I am not aware of the problems that there are […] But to be active citizen you should know about an issue, a topic of interest, and you should know how to manage situations so that there is something for the community. Not knowing about the problem, not knowing the means, not knowing the bureaucratic structures, not knowing who to turn to, what can I do? (FG3).

Many of the students agreed that the education model that they were experiencing followed a rather passive approach, which did not allow the exercise of democratic skills and agency within the confines of their schools. Some of the students were especially critical in denouncing an education that was more focused on abstract learning and knowledge transmission rather than on personal development and recognition of agency.

For them work in the school is not about forming an individual, but more than anything else is to do mathematics, Italian, history, philosophy […] for them it ends there. (FG4).

In my opinion, unfortunately, most of the time the school encapsulates discourses, it gives us concepts and we have to absorb them only in order to know how to repeat them to the teachers, but it is not that we can practice them. (FG2).

In line with the quantitative findings, students focused on the beneficial aspects of treating current events in the classroom and discussing civic and political topics with their teachers. Across all schools and discussions, participants described interested teachers as their main source of information in school on these issues. Teachers who treated current events and social issues, stimulated students’ interest and discussion were all seen as formative in awakening civic awareness.

It may have happened several times during the hours of philosophy and history–given the personality of our teacher–to talk to us about current issues […] I mean that he is a person who tends to bring out his own ideas and tends to involve the kids, trying to wake them up about what the current world is. (FG1).

It was underlined by the students however that these discussions would not be part of the topics defined by the curriculum and depended on the individual teachers’ approach. At times, this meant that there would be difficulties with catching up with the program and with other teachers who do not share the same interests. In this sense, the dense curriculum and its constraints were widely seen as obstacles toward treating civic issues in class.

In ninth grade we had this teacher and she cared a lot about these things but she was the only one. She followed this and not the program of course.—Useful, but for many things now, the teacher tells us "Did you do this thing from the program before?" and nobody knows what we are talking about, so we have voids in the program.—From a certain point of view, it was constructive, but on the other hand, we are penalized now. (FG7).

We do not deal with current issues, little or almost never. Professors, rightly, say that they have to follow their program, maybe they can't even finish it, and therefore, the time to dedicate to dialogue and in any case to important current topics does not exist or in any case is not sufficient. (FG6).

While civic discussions were reported as stimulating, during the focus groups students would often reveal that what they found lacking was the opportunity for interaction and confrontation between opinions. Participants gave importance to encouraging debate, treating students as equals and fostering free expression in the classroom, in line with their understanding that independent thinking and voicing one’s opinion were at the center of their civic development.

Because then we also learn to think for ourselves, to make our own ideas, not what the book says. Maybe I can think of it as it is in the book, but if I go out, I get a completely different idea, which without debate I can’t develop. (FG2).

Debating, in particular, was seen as the most effective strategy of fostering critical understanding of civic and political issues and independent thinking. In schools that did not have a debate group, students suggested creating ones.

In my opinion it would be nice to dedicate time to debate. To see what someone else thinks […] So we should talk at school, there you go! I would like it very much; maybe stay in the afternoon and create a group where we talk about certain topics, such as immigration. (FG10).

However, students largely referred that debate and confrontation on topical issues would be often avoided in the classroom. According to them, sometimes teachers approached issues unilaterally and avoided stirring discussions with and among students, in order to shun potential conflict or exposing their own opinions. Hence, teachers were considered as particularly influential in facilitating or inhibiting growth of political interest in school, as well as in providing space for crucial critical reflection and debate.

Some read the newspaper, but there’s no debate. (FG9) With the teacher of religion, we always talk about current affairs with her, we can express ourselves freely. Perhaps with other teachers who may have an idea that is felt, let's say that it …—Moderator: prevails?—Yes, that's right. (FG1).

A lot of the students that participated in the discussion were involved in activities of representation in school councils and assemblies (28 students). This type of involvement was highlighted as an important formative experience of taking up responsibilities in organizing activities and representing other students’ needs. Students depicted school councils as a context in which civic competences were developed.

The fact that there is a link between the Institute and the class, attending meetings, you can discover many things […] organizing activities that are done in the school and out of the school, preparing the meetings, organizations, activities. Even the more important things–organizing assemblies for students’ self-management. (FG2)

However, these experiences were accompanied in most cases by a sense of lack of responsiveness by the school authorities and a perception that the power imbalance between students and teachers was unavoidable. Several students reported that their experiences were accompanied by some frustration in cases where students’ voice was limited or ignored by teachers and the school administration. Student representatives evoked examples of having little space for actual decision-making, revealing the existence of a tokenistic dimension of their participation at school. Students from several schools denounced not being given enough responsibility to make decisions within their schools and freedom of voice in their educational life.

And then, the fact that anyway our word does not have the same weight against that of the teachers. The professors will always be right. (FG6)

I spend 5 h per day at this school, it has to mean something, this is my school, I represent something and I don't even know what I represent […] Let’s say that all these organs that have been established are only skin deep, because they are good for nothing–we have no power at all and there's nothing we can do. (FG9).

Interestingly, the most critical students came from an institute that offered comparatively more innovative classroom and extra-curricular activities, such as flipped classrooms and debate groups. It is possible that these initiatives have exerted a positive impact on the development of young people’s critical thinking and confidence, which in turn has helped them in identifying the obstacles that hamper democratic potential in the school.

Beyond student councils, participants reported several extra-curricular initiatives and activities that motivated in them further participation. These included volunteering activities, presentations of organizations and associations, meetings with experts, internships in civic organizations, debate groups, parliament simulations. In most cases, these opportunities had to do with either the promotion of civic and political knowledge or with involvement in pro-social volunteering. Moreover, students from schools with academic tracks seemed to recall more varied opportunities for extra-curricular participation. However, these differences might reflect the selection of participants made by the referent teachers. Furthermore, the pupils we approached did not necessarily have knowledge of all the existing opportunities in their school and reported only the ones that were personally relevant to them.

Nevertheless, students’ accounts of some of these experiences revealed a sense of ambiguity. Participants generally described their participation as valuable and considered it very formative. At times, however, participants lamented being obstructed in their involvement in extra-curricular activities by other teachers or the school’s direction. They highlighted issues of tokenism on behalf of the school and of teachers, which in their perception did not give the right importance to their agency development.

Instead, we’ve found ourselves often with professors who maybe couldn't give value to the initiatives proposed by the school itself. […] there are professors who don't realize the importance it may have. They come to preach to you on a school subject, but fail to realize the opportunities that the school gives. (FG10)

However, in my opinion, the school does not give it such importance, they make us to do it just because […] the school says "Yes, okay," but then doesn't really care much about it. For us, it is very important, but should also be important to the people make us do it. And, more often than not, it isn't. (FG5)

The present research sought to examine the role of school-related opportunities in students’ experiences that impact the development of civic engagement among youth. We employed mixed methods in order to elucidate adolescents’ experience of democratic school characteristics and the processes through which they can promote civic participation. The findings from the two studies presented in the paper–one quantitative and one qualitative–highlight the importance and limitations of aspects such as perceived democratic school climate, perceived opportunities for critical reflection and student participation at school for the development of civic attitudes and behavior. The paper aims to fill gaps in the literature by analyzing multiple democratic experiences and the processes that could explain the promotion of actual active participation among adolescents. Moreover, the research provides original contributions to understanding the understudied dimension of perceived critical reflection at school and its relation to the promotion of civic participation.

The survey specifically examined the influence of perceived democratic school climate, critical reflection at school and student participation on civic participation at a one-year interval, while controlling for classroom-level clustering. In addition, it verified whether mediation processes through institutional trust, political interest and civic efficacy could explain these influences. The hypotheses were tested with a SEM analysis on temporally separated measures, which took into account the nested structure of the data in classrooms and controlled for the confounding effect of age, sex, perceived family income and school track. The results showed that student participation in school activities had an important impact on civic development by influencing positively civic efficacy beliefs, political and societal interest and civic participation. Students showed greater levels of efficacy, interest and civic behavior after one year when they had participated in student councils and extra-curricular groups and activities in their schools. Having experience in these activities could have allowed students to put into practice acquired civic skills and strengthen existing interests in the civic sphere, thus influencing more directly their behavior outside of school. In other words, “civic action, after all, does not simply depend on what individuals decide to do or not to do; it also crucially depends on the opportunities they have for participation” (Biesta, 2011, p. 151). Political and societal interest was found to mediate partially the influence of student participation and to mediate fully the effect of critical reflection on civic behavior. Opportunities for involvement in student activities and for reflecting critically at school promoted greater participative engagement among students through the increase of interest in social and political issues. These findings give support to the claim that schools promote civic development when they represent supportive and challenging environments, in which students can experience opportunities for action and reflection (Fernandes-Jesus et al., 2012; Ferreira et al., 2012; Piedade et al., 2020). The combination of experiencing participative role-taking and having the opportunity to reflect and consider diverse perspectives is an important part of the developmental interactions in citizenship education that students can experiment within the school context. The findings also highlight the crucial role that promoting interest in civic issues can play in the process of participative activation. If according to Emler (2011) interest is the key starting point for becoming an active citizen, then experiences of student participation and critical reflection seem to influence the initiation of young people’s effective engagement with civic matters outside of the school environment.

The role of different dimensions of democratic school climate in promoting civic engagement has been widely recognized in previous research (Torney-Purta, 2002; Flanagan et al., 2007; Quintelier and Hooghe, 2013; Lenzi et al., 2014). Our results evidence that students’ perceptions of openness in the classroom, fairness and influence in schools’ decision-making seem to influence the perception of authorities and institutions and to promote greater confidence in personal and collective civic abilities. These results are consistent with previous findings on the role of open classroom climate in increasing institutional trust and efficacy beliefs (Pasek et al., 2008; Claes et al., 2012; Dassonneville et al., 2012; Barber et al., 2015). However, contrary to what could be expected from the existing literature, democratic school climate did not influence neither directly nor indirectly reported civic participation in our sample. The results suggest that in a one-year period the promotion of personal and collective efficacy and trust in institutions is not sufficient for initiating a process of engagement that results in actual behavior for social causes (volunteering, donating, etc.). The benefits of perceived democratic school climate on an individual level, thus, are not immediately evident with respect to students’ civic activity outside of school. They may however have a more long-running impact and facilitate engagement in a later stage of development. It should also be noted that, while it is generally considered an important dimension of active citizenship, institutional trust has been shown to have an ambivalent and varying relationship with different forms of participation (Brunton-Smith, 2011; Hooghe and Marien, 2013), and people who feel confident in the institutional functioning may not feel the urge to take action and assume a standby position (Amna and Ekman, 2014; Tzankova et al., 2020). Thus, experiencing a positive school climate that is centered around democratic values and convinces students that institutions work well may actually lull them into not delving into critical issues and problems which could otherwise prompt their involvement.

The findings from the focus groups discussions helped explain some of the results obtained in the test of the mediation model. Students’ accounts supported observations of the importance of active involvement in student activities and opportunities for meaningful reflection on diverse opinions. Participants also emphasized how civic discussions in the classroom and being able to have a say in their schools promoted competences and agency. However, focus groups also revealed that civic discussions were not only rare in students’ experiences, but they were nonetheless often not really open to confrontation between opinions. While they appreciated these occasions, students seemed to be aware that more in-depth discussions in the form of debates are needed. Indeed, it has been previously noted that classroom settings rarely offer exposure to substantive civic discussions and students may have a limited conception of what truly constitutes deliberation–i.e., thoughtful consideration of conflicting views on controversial issues (Avery et al., 2013; Maurissen et al., 2018). Our examination of students’ perspectives highlights the necessity of providing contexts where adolescents’ can exchange points of view, explore multiple perspectives and defend their opinions.

Focus groups also provided a clearer picture of the limitations that students perceived in the capacity of their schools to effectively provide democratic experiences. Participants evidenced aspects of curriculum-based constraints that push practice-based citizenship education to the background. They also revealed perceiving tokenistic attitudes in their involvement in school councils and extracurricular activities, which could hinder their beneficial impact on developing civic agency.

Based on the results obtained from the two studies presented in the paper, we argue that democratic school climate is an important factor for the civic development of adolescents, but may not be sufficient in promoting civic participation if not accompanied by active involvement in school activities and by critical reflection on opinions and on experiences in school. It is important for students to practice voicing their opinions, addressing contrasting points of view and to be encouraged to reflect critically in order to promote broader participation in time. Educational settings should also provide opportunities for student involvement that go beyond the promotion of trust in institutions. Engagement through practical activity and interest seem to be more substantial predictors of civic participation and they are promoted by direct and critically oriented ways of being involved at school.

Finally, the results from the survey showed that school tracks had an impact on the levels of political interest, civic efficacy and reported civic participation among students. Being a student in a higher academic track led to better scores on these dimensions. School tracks may indeed provide less opportunities for civic socialization and perpetuate existing social inequalities in participation (e.g., Eckstein et al., 2012). The existing inequalities between schools in the Italian educational system seem to impact students’ civic development as well.

Some limitations of the present research should be mentioned. Both studies were based on data that is not representative. In this sense, conclusions deriving from our findings are not necessarily illustrative of other national or educational contexts. Further research could investigate similarities and differences in a cross-national approach. Moreover, we analyzed as an outcome of the quantitative study a specific type of participation–namely, civic participation in terms of volunteering, activity and donations for social causes. The investigation could be expanded in the future to compare more varied engagement in political or online forms. In addition, the research focused exclusively on perceived characteristics of schools and on individual-level explanations of civic engagement, although taking into account classroom variation and influence of school tracks. Further research should also consider interactions with other structural factors, school-level differences in the variables and socio-political contextual specificities that influence the examined processes.

The findings point to important voids in the implementation of good civic education practices in the complicated context of ongoing educational reforms in Italy. Overall, the students’ experiences with regards to approaching civic and political matters in school appeared to support the centrality of a participatory school culture that creates a supportive environment of open discussion, contestation, involvement and reflection. As resulting from the analysis in the institutes we approached, getting school administration and teachers on board with such an approach to capacity-building still remains a challenge. Collaborative relations, in which students are valued as autonomous agents and can be an integral part of the school life, need to be promoted further in Italy. Students need to feel that their opinions are valued, and that when they collaborate on an issue that interests them, teachers and school administrations will listen to their requests.

The quantitative data that support the findings of Study 1 are openly available from AMS Acta Institutional Research Repository – University of Bologna at http://doi.org/10.6092/unibo/amsacta/6638. The qualitative data that support the findings of Study 2 are openly available from AMS Acta Institutional Research Repository – University of Bologna at http://doi.org/10.6092/unibo/amsacta/6639.This data is made available for open access in compliance with H2020 Program regulation, following the guidelines stipulated by the Data Management Plan adopted by the CATCH-EyoU research project.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Bioethics Committee of the University of Bologna. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin.

IT, CA and EC have written the article, collected and analyzed the survey data and the focus group data used for the study.

The research reported in this paper was funded by the European Union, Horizon 2020 Programme, Constructing AcTive CitizensHip with European Youth: Policies, Practices, Challenges and Solutions (www.catcheyou.eu), grant agreement number 649538. The views and opinions expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Commission.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The content of this manuscript has been published in part as part of the thesis of IT (Tzankova, 2018). A preliminary version of the results of the studies have been presented at the EARA2020 conference (Porto, 2–5 September 2020).

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2021.611824/full#supplementary-material.

Albanesi, C., Zani, B., and Cicognani, E. (2012). Youth civic and political participation through the lens of gender: the Italian case. Hum. Aff. 22 (3), 360–374. doi:10.2478/s13374-012-0030-3

Albanesi, C. (2020). “Le politiche scolastiche sulla promozione della cittadinanza attiva (ducational policies on the promotion of active citizenship),” in La cittadinanza attiva a scuola (Active citizenship at school). Editors E. Cicognani, and C. Albanesi (Rome, Italy: Carocci), 45–72.

M. Ambel (Editors) (2020). Una scuola per la cittadinanzaI: dee, percorsi, contesti [A school for citizenship. PM Edizioni.

Amna, E., and Ekman, J. (2014). Standby citizens: diverse faces of political passivity. Eur. Pol. Sci. Rev. 6 (2), 261–281. doi:10.1017/s175577391300009x

Amna, E., Ekström, M., Kerr, M., and Stattin, H. (2010). Codebook the political socialization program. Örebro, Sweden: Youth & Society at Örebro University.

Avery, P. G., Levy, S. A., and Simmons, A. M. M. (2013). Deliberating controversial public issues as part of civic Education. Soc. Stud. 104 (3), 105–114. doi:10.1080/00377996.2012.691571

Barber, C., Sweetwood, S. O., and King, M. (2015). Creating classroom-level measures of citizenship education climate. Learn. Environ. Res. 18 (2), 197–216. doi:10.1007/s10984-015-9180-7

M. Barrett, and B. Zani (Editors) (2015). Political and civic engagement: multidisciplinary perspectives (London, United Kingdom: Routledge).

M. Barrett, and D. Pachi (Editors) (2019). Youth civic and political engagement (London, United Kingdom: Routledge).

Barrett, M. (2015). “An integrative model of political and civic participation,” in Political and Civic Engagement Multidisciplinary perspectives. Editors M. Barrett, and B. Zani (London, United Kingdom: Routledge), 162–187.

Biesta, G. (2011). Learning democracy in school and society: education, lifelong learning and the politics of citizenship. Rotterdam, Netherlands: Sense Publishers.

Bombardelli, O., and Codato, M. (2017). Country report: civic and citizenship education in Italy: thousands of fragmented activities looking for a systematization. J. Soc. Sci. Educ. 16 (2), 74–81. doi:10.15405/epsbs.2016.11.36

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3 (2), 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Brunton-Smith, I. (2011). Modelling existing survey data: Full technical report of PIDOP Work Package 5. Surrey, United Kingdom: University of SurreyAvailable at: https://epubs.surrey.ac.uk/739988/2/PIDOP_WP5_Report.pdf_revised.pdf

Castillo, J. C., Miranda, D., Bonhomme, M., Cox, C., and Bascopé, M. (2015). Mitigating the political participation gap from the school: the roles of civic knowledge and classroom climate. J. Youth Stud. 18 (1), 16–35. doi:10.1080/13676261.2014.933199

Cho, E., and Kim, S. (2015). Cronbach’s coefficient alpha: well known but poorly understood. Organ. Res. Methods 18 (2), 207-230. doi:10.1177/1094428114555994

Cicognani, E., and Menezes, I. (2021). CATCH-EyoU. representations of the EU and youth active citizenship in educational contexts. Focus groups with Italian students. EXTRACT. Perceived school characteristics fostering civic engagement [Dataset]. University of BolognaAvailable at: http://doi.org/10.6092/unibo/amsacta/6639

Cicognani, E., Noack, P., and Macek, P. (2021). CATCH-EyoU. processes in Youth’s construction of Active EU citizenship. Italian longitudinal (Wave 1 and 2) questionnaires. EXTRACT. Perceived School Characteristics Fostering Civic Engagement [Dataset]. University of BolognaAvailable at: http://doi.org/10.6092/unibo/amsacta/6638

Cicognani, E., Zani, B., Fournier, B., Gavray, C., and Born, M. (2012). Gender differences in youths’ political engagement and participation. The role of parents and of adolescents’ social and civic participation. J. Adolesc. 35 (3), 561–576. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2011.10.002

Claes, E., and Hooghe, M. (2017). The effect of political science education on political trust and interest: results from a 5-year panel study. J. Polit. Sci. Educ. 13 (1), 33–45. doi:10.1080/15512169.2016.1171153

Claes, E., Hooghe, M., and Marien, S. (2012). A two-year panel study among Belgian late adolescents on the impact of school environment characteristics on political trust. Int. J. Pub. Opin. Res. 24 (2), 208–224. doi:10.1093/ijpor/edr031

Cockburn, T. (2007). Partners in power: a radically pluralistic form of participative democracy for children and young people. Child. Soc. 21 (6), 446–457. doi:10.1111/j.1099-0860.2006.00078.x

Dassonneville, R., Quintelier, E., Hooghe, M., and Claes, E. (2012). The relation between civic education and political attitudes and behavior: a two-year panel study among Belgian late adolescents. Appl. Dev. Sci. 16 (3), 140–150. doi:10.1080/10888691.2012.695265

Davies, I., Hampden-Thompson, G., Calhoun, J., Bramley, G., Tsouroufli, M., Sundaram, V., et al. (2013). Young people’s community engagement: what does research-based and other literature tell us about young people’s perspectives and the impact of schools’ contributions? Br. J. Educ. Stud. 61 (3), 327–343. doi:10.1080/00071005.2013.808316

Davies, I., Sundaram, V., Hampden-Thompson, G., Tsouroufli, M., Bramley, G., Breslin, T., et al. (2014). Creating citizenship communities: education, young people and the role of schools. London, United Kingdom: Palgrave Macmillan.

Eagly, A. H., Wood, W., and Diekman, A. B. (2000). “Social role theory of sex differences and similarities: a current appraisal,” in The developmental social Psychology of gender. Editors T. Eckes, and H. M. Trautner (Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum), 123–174.

Eckstein, K., and Noack, P. (2014). Students’ democratic experiences in school: a multilevel analysis of social-emotional influences. International Journal of Developmental Science, 8 (3-4), 105–114. doi:10.3233/DEV-14136

Eckstein, K., Noack, P., and Gniewosz, B. (2012). Attitudes toward political engagement and willingness to participate in politics: trajectories throughout adolescence. J. Adolesc. 35 (3), 485–495. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2011.07.002

Ehman, L. H. (1980). Change in high school students’ political attitudes as a function of social studies classroom climate. Am. Educ. Res. J. 17 (2), 253–265. doi:10.3102/00028312017002253

Ekman, J., and Amna, E. (2012). Political participation and civic engagement: towards a new typology. Hum. Aff. 22 (3), 283–300. doi:10.2478/s13374-012-0024-1

Emler, N. (2011). “What does it take to be a political actor in a multicultural society?,” in Nationalism, Ethnicity, Citizenship. Editors M. Barrett, C. Flood, and J. Eade (Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge Scholars Publishing), 135–162.

Enchikova, E., Neves, T., Mejias, S., Kalmus, V., Cicognani, E., and Ferreira, P. D. (2019). Civic and political participation of European youth: fair measurement in different cultural and social contexts. Front. Edu. 4, 10. doi:10.3389/feduc.2019.00010

Eurostat (2015). Participation in formal or informal voluntary activities or active citizenship by sex, age and educational attainment level. Luxembourg City, Luxembourg: Eurostat.

Fernandes-Jesus, M., Malafaia, C., Ferreira, P., Cicognani, E., and Menezes, I. (2012). The many faces of Hermes: the quality of participation experiences and political attitudes of migrant and non-migrant youth. Hum. Aff. 22 (3), 434–447. doi:10.2478/s13374-012-0035-y

Ferreira, P. D., Azevedo, C. N., and Menezes, I. (2012). The developmental quality of participation experiences: beyond the rhetoric that “participation is always good!”. J. Adolesc. 35 (3), 599–610. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2011.09.004

Flanagan, C. A., and Christens, B. D. (2011). Youth civic development: historical context and emerging issues. New Dir. Child Adolesc. Dev. 2011 (134), 1–9. doi:10.1002/cd.307

Flanagan, C. A., Cumsille, P., Gill, S., and Gallay, L. S. (2007). School and community climates and civic commitments: patterns for ethnic minority and majority students. J. Educ. Psychol. 99 (2), 421–431. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.99.2.421

Flanagan, C. A. (2013). Teenage citizens: the political theories of the young. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Flick, U. (2014). An introduction to qualitative research. 5th Edn. London, United Kingdom: Sage Publications.

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed (Myra Bergman Ramos, trans.), New York: Continuum. (Original work published 1968).

Gaby, S. (2017). The civic engagement gap(s): youth participation and inequality from 1976 to 2009. Youth Soc. 49 (7), 923–946. doi:10.1177/0044118x16678155

Garcia-Albacete, G. M. (2013). “Promoting political interest in schools: the role of civic education,” in Growing into Politics Contexts and timing of political socialization. Editor S. Abenschön (Colchester, United Kingdom: ECPR Press), 91–114.

Geboers, E., Geijsel, F., Admiraal, W., and Dam, G. t. (2013). Review of the effects of citizenship education. Educ. Res. Rev. 9, 158–173. doi:10.1016/j.edurev.2012.02.001

Glaser, B. G., and Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory. Piscataway, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

Godfrey, E. B., and Grayman, J. K. (2014). Teaching citizens: the role of open classroom climate in fostering critical consciousness among youth. J. Youth Adolesc. 43 (11), 1801–1817. doi:10.1007/s10964-013-0084-5

Haste, H. (2004). Constructing the citizen. Polit. Psychol. 25 (3), 413–439. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9221.2004.00378.x

Hedtke, R. (2013). “Who is afraid of non-conformist youth?,” in Education for civic and political participation. Editors R. Hedtke, and T. Zimenkova (London, United Kingdom: Routledge), 54–78.

Hooghe, M., and Marien, S. (2013). A comparative analysis of the relation between political trust and forms of political participation in Europe. European Societies, 15 (1), 131–152. doi:10.1080/14616696.2012.692807

Hoskins, B., Janmaat, J. G., and Villalba, E. (2012). Learning citizenship through social participation outside and inside school: an international, multilevel study of young people’s learning of citizenship. Br. Educ. Res. J. 38 (3), 419–446. doi:10.1080/01411926.2010.550271

ISTAT (2017). Studenti e scuole dell’istruzione primaria e secondaria in Italia [Students and schools in primary and secondary education in Italy]. Roma, Italy: Istituto Nazionale di Statistica.

Kahne, J. E., and Sporte, S. E. (2008). Developing citizens: the impact of civic learning opportunities on students’ commitment to civic participation. Am. Educ. Res. J. 45 (3), 738–766. doi:10.3102/0002831208316951

Lawy, R., and Biesta, G. (2006). Citizenship-as-practice: the educational implications of an inclusive and relational understanding of citizenship. Br. J. Educ. Stud. 54 (1), 34–50. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8527.2006.00335.x

Lenzi, M., Vieno, A., Sharkey, J., Mayworm, A., Scacchi, L., Pastore, M., et al. (2014). How school can teach civic engagement besides civic education: the role of democratic school climate. Am. J. Commun. Psychol. 54, 251–261. doi:10.1007/s10464-014-9669-8

Levy, B. L. M. (2013). An empirical exploration of factors related to adolescents’ political efficacy. Educ. Psychol. 33 (3), 357–390. doi:10.1080/01443410.2013.772774

Losito, B. (2009). La costruzione delle competenze di cittadinanza a scuola: non basta una materia [Building citizenship competencies in schools: one discipline is not enough]. Cadmo 1, 99–112. doi:10.3280/CAD2009-001013

Manganelli, S., Lucidi, F., and Alivernini, F. (2015). Italian adolescents’ civic engagement and open classroom climate: the mediating role of self-efficacy. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 41, 8–18. doi:10.1016/j.appdev.2015.07.001

Maurissen, L., Claes, E., and Barber, C. (2018). Deliberation in citizenship education: how the school context contributes to the development of an open classroom climate. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 21, 951–972. doi:10.1007/s11218-018-9449-7

Muthén, L. K., and Muthén, B. O. (2015). Mplus user’s guide. 7th Edn. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén.

Nieuwelink, H., Dekker, P., Geijsel, F., and ten Dam, G. (2016). ‘Democracy always comes first’: adolescents’ views on decision-making in everyday life and political democracy. J. Youth Stud. 19 (7), 990–1006. doi:10.1080/13676261.2015.1136053

P. Noack, and P. Macek (Editors) (2017). Constructing AcTive CitizensHip with European youth. (Bologna, Italy: University of Bologna).

Pasek, J., Feldman, L., Romer, D., and Jamieson, K. H. (2008). Schools as incubators of democratic participation: building long-term political efficacy with civic education. Appl. Dev. Sci. 12 (1), 26–37. doi:10.1080/10888690801910526

Piedade, F., Malafaia, C., Neves, T., Loff, M., and Menezes, I. (2020). Educating critical citizens? Portuguese teachers and students’ visions of critical thinking at school. Think. Skills Creat. 37 100690. doi:10.1016/j.tsc.2020.100690

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., and Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 63, 539–569. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100452

Prior, M. (2010). You’ve either got it or you don't? The stability of political interest over the life cycle. J. Polit. 72 (3), 747–766. doi:10.1017/s0022381610000149

Quintelier, E., and Hooghe, M. (2013). The relationship between political participation intentions of adolescents and a participatory democratic climate at school in 35 countries. Oxford Rev. Educ. 39 (5), 567–589. doi:10.1080/03054985.2013.830097

Resh, N., and Sabbagh, C. (2017). Sense of justice in school and civic behavior. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 20 (2), 387–409. doi:10.1007/s11218-017-9375-0

Russo, S., and Stattin, H. (2017). Self-determination theory and the role of political interest in adolescents’ sociopolitical development. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 50, 71–78. doi:10.1016/j.appdev.2017.03.008

Scheerens, J. (2011). Indicators on informal learning for active citizenship at school. Educ. Asse. Eval. Acc. 23 (3), 201–222. doi:10.1007/s11092-011-9120-8

Schulz, W., Ainley, J., Fraillon, J., Kerr, D., and Losito, B. (2010). ICCS 2009 international report: civic knowledge, attitudes, and engagement among lower-secondary school students in 38 countries. Amsterdam, Netherlands: IEA.

Shaw, A., Brady, B., McGrath, B., Brennan, M. A., and Dolan, P. (2014). Understanding youth civic engagement: debates, discourses, and lessons from practice. Commun. Dev. 45 (4), 300–316. doi:10.1080/15575330.2014.931447

Sohl, S., and Arensmeier, C. (2015). The school’s role in youths’ political efficacy: can school provide a compensatory boost to students’ political efficacy? Res. Pap. Edu. 30 (2), 1–31. doi:10.1080/02671522.2014.908408

Stefani, S., Prati, G., Tzankova, I., Ricci, E., Albanesi, C., and Cicognani, E. (2021). Gender Differences in Civic and Political Engagement and Participation Among Italian Young People. Social Psychological Bulletin., 16 (1), 1-25. doi:10.32872/spb.3887

Torney-Purta, J., and Barber, C. (2005). Democratic school engagement and civic participation among European adolescents: analysis of data from the IEA Civic Education Study. J. Soc. Sci. Edu. 4 (3), 13–29.

Torney-Purta, J., Lehmann, R., Oswald, H., and Schulz, W. (2001). Citizenship and education in tweny-eight countries. Amsterdam, Netherlands: IEA.

Torney-Purta, J. (2002). The school’s role in developing civic engagement: a study of adolescents in twenty-eight countries. Appl. Dev. Sci. 6 (4), 203–212. doi:10.1207/s1532480xads0604_7