- Institute of Political Science, University of Heidelberg, Heidelberg, Germany

In recent years, young adults have increasingly expressed their displeasure with climate policies, arguing that the preservation of the earth for future generations is not secured by existing policies. A growing number of young citizens demands action from politicians and accuses them of a lack of responsiveness. At the same time, young adults are undergoing political socialization, not only within their families, but especially in school, where they learn to lead an independent life and to form their own political opinions. However, what happens if students question the knowledge on the political system that they have acquired in school? This paper analyses how the exogenous “shock” of Fridays for Future has influenced pupils' political attitudes compared to other continuous skills that pupils learn in school. Relying on a unique survey experiment among pupils from different school types and among students in Germany (more than 300 respondents), we find that priming for Fridays for Future and protest participation significantly change perceived political responsiveness and satisfaction with democracy. The results demonstrate that the efforts of schools to prepare young citizens for professional life have no effect, while equal treatment in school is explanatory for varying political satisfaction. Protest participation seems to have a great influence on how the political attitudes of the young cohort develop.

Introduction

“We are striking because we have done our homework, and they have not.” —Greta Thunberg, climate protest in Hamburg, Germany, 1 March 2019

Although research has found youth to be less politically engaged than older generations (Quintelier, 2007), the sheer number of climate activists who have taken to the streets in recent years has challenged this view. Fridays for Future, started as a “skolstrejk för klimatet” (school strike for climate), was founded and is led by pupils and students and has sparked one of the largest global protest events in history. Around a million teenage school students have attended the climate protests every Friday, protesting against how politicians deal with the climate crisis. Not attending school and observing how a grassroots demonstration is viewed and treated by democratic institutions can influence young adults' perception of those. Being politically socialized by parents and schools (Banks and Roker, 1994; Jennings and Greenberg, 2009; Quintelier, 2013) protesting together with peers can be regarded as an exogenous shock that significantly influences not only how youth is politically socialized but also how they perceive politics. For many participants, Fridays for Future (FFF) is the first experience in non-institutionalized political participation and might therefore have a great effect on political attitudes (Wahlström et al., 2019). In fact, these protest experiences might challenge the knowledge they acquire in school on how the political system works and on how democratic practices can be implemented (Campbell, 2008; Pasek et al., 2008). Thus, on the one hand, schools play a key role in the formation of civic identity, and if school procedures are regarded as fair, democratic orientation and trust will increase (Resh and Sabbagh, 2014). However, on the other hand, the considerable amount of time spent in protests, where attendants are only moderately hopeful that politicians will act in favor of their goals (Wahlström et al., 2019), can influence political attitudes as well.

In this paper, we want to find out whether protest participation in general and FFF specifically have an influence on youth perceptions of political responsiveness as well as on their satisfaction with democracy. We argue that daily school experiences with democracy are challenged by FFF experiences. Even though former studies did not find a relationship between political participation and political trust among young adults (Niemi and Klingler, 2012), we expect FFF, due to its size and regularity, to change how this demographic views politicians and the political system. Since FFF is a protest movement that was founded and is run by youth (Wahlström et al., 2019), it is plausible that it differs from past demonstrations in which youth only made up a part of the whole group of demonstrators.

In order not to distort the results by only asking protesters during demonstrations, we used a unique priming survey experiment, conducted in different schools and in an introductory lecture at Heidelberg University, Germany (n = 338) in 2019. The young adults (15–35 years old) were randomly assigned to receive questions on FFF and the climate crisis at the beginning of a classroom questionnaire. Based on the data collected, we divide the analysis into two parts: first, we analyze whether personal protest participation influences political attitudes. Here, we find that protest participation and equal treatment in school increase satisfaction with democracy but not perceived political responsiveness. Second, we compare an FFF-primed group with a non-primed group to find out whether specific information on youth protest influences satisfaction with democracy and perceived political responsiveness. Respondents primed for FFF differ in their answers from respondents who have not been primed: They report higher degrees of diffuse and specific system support, even though the results are less clear. Diffuse system support particularly increases when youth have personally taken part in demonstrations or when they are reminded of the latest climate protests. These findings have wider scientific and social implications, as they demonstrate that it is important to analyze different kinds of political attitudes to gain a broader picture on how single events and continuous experiences influence youth. While political protest seems to increase satisfaction with democracy, it decreases policy- and government-related attitudes. Additionally, the findings highlight the function of schools as small entities of democracy where individuals incorporate political attitudes for a long time period: the experience of equal treatment by teachers has an effect on satisfaction with democracy but not on perceived political responsiveness. This could mean that system-related attitudes are developed in institutions and during political participation, but that these two places of socialization have no effect on policy- and government-related attitudes.

The rest of this paper enfolds as follows: the next sections review previous literature and introduce our theoretical expectations to answer our research question: How does participation in demonstrations influence perceived political responsiveness and youth satisfaction with democracy? We then present our original dataset and the statistical methods we used to test our hypotheses. The analysis is separated into two parts: While the first is based on the full sample and analyzes how protest participation influences political attitudes, the second part is a comparison of the two groups of the FFF priming experiment. Here, we examine how current events affect young people's evaluations of politicians and the political system as such. This helps us to test robustly whether we find comparable results for protest participation in general and FFF in specific. Finally, we discuss our findings and draw a conclusion in which we also identify implications for future research.

State of Research

Youth Political Participation and School Socialization

Even though the FFF protest movement gives the impression that young adults participate strongly in politics, research on youth participation has been rather critical (Ferreira et al., 2012). For instance, the so-called lifecycle effect states an increasing willingness for political participation up to middle age and a subsequent decline in political participation, resulting in low participation scores among the youth and the elderly (Jennings, 1979). However, while former studies argued that youth are less politically interested and active in general (Dahl et al., 2017), research has since clarified and corrected this observation: Young adults use institutionalized forms of participation less, such as voting or party membership, and rely instead on non-institutionalized forms of political participation, such as boycotts or online discussions (Quintelier, 2007; Weiss, 2020). Since non-institutionalized forms of political participation are often not covered in studies, young adults are frequently considered as being less politically involved. Recent literature also bases this observation on the argument that youth might feel less affected by public policies than the adult population does (Keeter et al., 2003). Quintelier (2007) adds that although young people might harbor a lower level of political interest or trust than adults, they still recognize when politicians do not address topics in their interest. Not feeling considered in political decision-making, for example, might result in a certain political abstinence. Thus, it is important to find out how young people's engagement in non-institutionalized forms of political participation influences their perceptions of political responsiveness and their satisfaction with democracy. While participation research focuses on how to explain certain patterns of youth political participation (O'Toole et al., 2003; Quintelier, 2007, 2013), this study understands political participation as a core factor that influences political attitudes.

A prominent example of youth political participation is the FFF movement. FFF is a movement in which, at a first glance, mainly young people are involved, i.e., people who have little political and financial power and whose concerns thus receive comparatively little attention in political institutions. However, in particular, children from highly educated and high-income families participate in the demonstrations, and they are often supported by their parents (Wahlström et al., 2019). Previous studies have shown that highly educated and wealthier groups are participating more due to their political and material resources, such as time, money, and civic skills, and that they therefore have a higher chance of influencing decision-making processes (Verba et al., 1995; Papadopoulos and Warin, 2007; Grimes and Esaiasson, 2014). Since politicians have a limited ability to gather opinions, it is likely that they will gather those that are visible and consider the publicly expressed interests as representative. FFF produces a large media echo, which contributes to the public awareness of the protests. It thus offers a suitable case to see what effects political participation has on the political attitudes of young adults. These can arise from both the young adults' own participation in the FFF demonstrations and through the perception of the movement.

Next to protest participation, another important aspect for explaining the political attitudes of young adults is socialization. Socialization theories assume that satisfaction with democracy is acquired at a young age, for example when individuals are in school, and that it changes little over the course of one's lifetime (Eckstein et al., 2012; Martini and Quaranta, 2019). This would mean that participation in demonstrations has no significant effect when controlling for people's early life experiences, such as those in school. In democratic societies, schools are core socialization institutions in addition to, for example, family and friends (Miklikowska and Hurme, 2011; Weiss, 2020); they can promote political trust, understanding of democracy, and the willingness to participate politically, both in institutionalized and non-institutionalized forms (Torney-Purta, 2002; Resh and Sabbagh, 2014; Özdemir et al., 2016). Schools have a specific teaching mission in explaining democratic structures and processes and which rights and obligations single citizens have (Flanagan et al., 2007; Lenzi et al., 2014). Teachers can promote political knowledge and political interest among students through discussions within the classroom on political or socially relevant topics. In addition, fair treatment by authorities, such as the government or other political institutions, can play an important role in the development of satisfaction with democracy. Having been treated fairly increases trust in political institutions (Miller and Listhaug, 1999; Grimes, 2006). It has also been shown that when students perceive their teachers as fair and respectful, they are more likely to value the importance of civic engagement and the development of political awareness (Flanagan et al., 2007; Lenzi et al., 2014). Other studies emphasize that the perceived fairness of teachers can have a positive influence on students' political knowledge (Claes et al., 2009) or stimulate their interest in politics (Claes and Hooghe, 2008).

Following this, we want to examine how experiences with protests in early life, but also socialization in school, influence political attitudes. Can the assumed low level of responsiveness be influenced by the occurrence of large protest events run by one's own generation and how large is the effect compared to continuous skills that youths learn in school (Quintelier and Hooghe, 2012; Quintelier and Van Deth, 2014)? Two political attitudes are of central interest here: perceived responsiveness and satisfaction with democracy. While the first measures satisfaction with concrete policy outputs, government decisions and governance, the latter measures satisfaction with the political system as a whole.

Political Attitudes: Satisfaction With Democracy and Perceived Political Responsiveness

The ability of politicians to consider the population's preferences and react to them responsively is an essential aspect of representation in a democratic system (Mansbridge, 2003; Esaiasson and Wlezien, 2017). Political responsiveness is defined as the consideration of citizens' interests in decision-making processes and involves a mutual interaction between citizens and representatives (Dahl, 1971; Esaiasson et al., 2015). In recent years, research in this field has focused on the question of whose political preferences are taken into account (Elsässer et al., 2018), showing that it is unequally distributed among different social groups, such as between the better-off and the middle class or the poor. Many social groups are skeptical about whose preferences are being incorporated into the decisions of representatives and feel that their own interests are not being sufficiently considered (Hibbing and Theiss-Morse, 2001; Allen and Birch, 2015; Hopkins et al., 2018). For instance, political responsiveness varies by income and gender (Gilens, 2012; Bernauer et al., 2015). Scholars have also found that elected governments are more responsive to the demands of highly educated individuals and groups (Page et al., 2013) and that they adjust their policy positions accordingly. However, this still young field of research has not yet presented any findings on age differences (Elsässer et al., 2018). Welfare state research, nevertheless, has pointed out that the preferences of the elderly are more often translated into concrete policies compared to the interests of younger cohorts (e.g., Tepe and Vanhuysse, 2010).

In comparison to political responsiveness, which focuses on specific support for political decision-makers, satisfaction with democracy refers to diffuse support for the underlying political system and its performance (Easton, 1975; Anderson, unpublished manuscript). It is often considered as an umbrella term that includes how the functioning of democracy is assessed and how trust in political institutions is pronounced. Schäfer (2013) found for 17 European countries that people who are interested in politics are more satisfied with democracy. In addition, Zilinsky (2019) found that younger people have a higher satisfaction with democracy than older ones.

Hypotheses

In this paper, we want to bring together two strings of literature: political participation research and research on education. By comparing the effects of protest experience and experiences in school, we are better able to sort the effect sizes. While previous studies have focused on either one or the other (Quintelier, 2013; Lenzi et al., 2014; Özdemir et al., 2016; Marquardt, 2020), we include both settings of socialization, namely experiences in school and one's own experiences through political participation, in our explanatory models. We also look at how one's perception of a social movement influences one's political attitudes. Next, we hypothesize how protest events relate to constant experiences with democracy in school.

While perceptions of political responsiveness are specific and fluid, other political attitudes are considered more continuous and constant. Since we are interested in how youth political participation influences different kinds of attitudes, we also look at satisfaction with democracy as an outcome variable. It could be that non-institutionalized political participation influences political attitudes that rely more on the political system (here: diffuse support) and less on the governmental composition (here: specific support), differently. For instance, a large portion of the population has positive attitudes toward the democratic system in their country but is not satisfied with the performance of political institutions. This notion of “critical citizens” —understood as individuals that support democracy as their ideal form of government but are dissatisfied with current political authorities and institutions—might result in different effects on diffuse and specific regime support (Norris, 1999).

Based on the literature, we expect politics to be less responsive to youth interests due to their relatively weak power position in financial and political regards. We argue that objective and perceived responsiveness are intertwined: Non-targeted groups can observe the results of the decision-making process and conclude that their interests are not represented. Thus, if specific preferences and interests are ignored, perceived political responsiveness of the concerned groups declines (see e.g., Cleary, 2007; Goubin, 2020). Due to the relatively weak political power position of youth, we expect young adults that participate in protests to perceive politicians as less responsive.

H1: Participation in protests decreases perceived political responsiveness among youth.

Initial surveys among FFF participants show that young people do not feel that their demands have been met (Marquardt, 2020; Wahlström et al., 2020). For instance, Wahlström et al. (2020) find in their survey that many participants answered that politicians would rarely reflect on the interests of the protests and that their demands are not transferred into concrete policies. In other words, they perceive that politicians have not responded sufficiently to their political participation. We therefore expect FFF as a youth protest movement to decrease perceived responsiveness. We also expect the actions of the in-group, the social group to which a person identifies as being a member (Crepaz et al., 2017), to affect political attitudes. Youth identify themselves strongly with people from their own age group, as expressed, for example, in the concept of “youth culture,” which describes certain cultural norms and practices young adults share (e.g., Kjeldgaard and Askegaard, 2006). Thus, in contrast to hypothesis 1, we are not asking for individuals to recall their personal experiences of protest participation, but for them to remember the FFF youth movement, as a form a survey priming. This encourages respondents to abstract from individual, specific experiences with FFF protests and to think of the FFF movement as a whole, enabling us to find out how this affects perceptions of the responsiveness of politicians. We test this relationship with a priming experiment, which is explained in detail in the method section.

H2: Young adults who are primed for FFF have a lower perception of political responsiveness than young adults who are not primed.

In addition, we expect young people who participate in demonstrations to fall into the category of critical citizens. By expressing dissatisfaction with how democratic institutions perform, they also make use of their freedom of assembly as a core norm of liberal democracies. Also, Wahlström et al. (2019) find that FFF participants mistrust concrete climate policies but still agree that democracy is the best form of government. Due to this, we hypothesize a positive relationship between youth political participation and political attitudes.

H3: Participation in demonstrations increases youth satisfaction with democracy.

In accordance with the theory of perceived responsiveness, we also expect priming for the in-group's role in this large protest movement to increase satisfaction with democracy. Thus, respondents who are not primed should report a lower level of satisfaction with democracy because they do not remember/are not reflecting on the opportunities for participation offered by the political system. Hence our fourth hypothesis:

H4: Young adults who are primed for FFF have a higher satisfaction with democracy than young adults who are not primed.

Therefore, we expect political participation to decrease specific system support but to increase diffuse system support, regardless of whether individuals participate themselves (H1 and H3) or whether they remember/reflect on the activism of their reference group (H2 and H4).

In bringing together political participation research and educational research, we have to ask what effects experiences in school have on political attitudes. Previous studies showed that being treated fairly and respectfully in school affects the political attitudes of young adults, such as raising their interest in politics (Flanagan et al., 2007; Claes and Hooghe, 2008; Claes et al., 2009; Lenzi et al., 2014). These findings demonstrate the importance of continuous experiences of equal treatment in school and their effect on satisfaction with democracy: If students feel unfairly treated in school, this negative feeling can lead to less satisfaction with democracy (Tyler and Blader, 2000). Thus, we hypothesize:

H5: If young adults were treated equally at school, they have a higher satisfaction with democracy.

In addition to equal treatment, schools can also be considered a public service institution where people learn to lead an independent life. The educational mandate for vocational preparation obliges schools to support individuals as they enter working life. Since entering working life is associated with many uncertainties (Tomasika et al., 2009), it is important to inform them well about application processes, different career paths and so on. However, if young people don't feel well-prepared, they could transfer their dissatisfaction with school services to the political system as a whole. Feeling uninformed and unsupported as they enter the labor market could lead young people to believe that the state does not care about them and that school has no value for their working life (Assor et al., 2005). Thus, we expect that attitudes toward vocational preparation in school can influence satisfaction with democracy as well.

H6: If young adults are well-prepared and informed about working life at school, they have a higher satisfaction with democracy.

However, what matters more when it comes to explaining political attitudes—school or protest events? Protest, when it arises from dissatisfaction with concrete policy outcomes, could diminish the continuous effect that school has on satisfaction with democracy. Unlike vocational preparation and learning fairness through equal treatment, which are continuous processes offered by schools, protest experiences are often unique and thus might be remembered long after the event. We therefore expect non-institutionalized participation to have a larger effect on political attitudes than daily experiences at school.

Case Selection and Method

We focus in our article on the climate protests of the FFF movement. As the regular protests on Fridays have shown, especially younger generations take to the streets to demand stricter environmental policies (Field, 2017; Foran et al., 2017; Wahlström et al., 2019). Thus, FFF is an appropriate case for investigating how large protest movements influence the political attitudes of the youth. However, in comparison to other empirical studies on the non-institutionalized political participation of youths, we draw our sample not from actual demonstrators. We assume that such empirical strategies overestimate the effect of protests since the sample would then consist only of politically active youths who are not representative of the entire youth population. Instead, we collected data from pupils in different school types. As studies by Wahlström et al. (2019) and others found, pupils from higher education institutions are particularly likely to take part in FFF. Including students from secondary and vocational schools, therefore, is essential to creating a more balanced sample. We have collected our data in the state of Baden-Württemberg, Germany. The educational system in Germany is characterized by the division of responsibilities between the Federation and the states (“Länder”). The basic responsibilities of the Federation are defined in the Basic Law (“Grundgesetz”) and unless otherwise stated, educational legislation is the responsibility of the states. Education in Germany is universal and dominated by a large public sector. School attendance is compulsory for at least 9 years from the age of 6 for all children living in Germany. Once pupils have completed compulsory schooling, they can attend a range of courses, from full-time general education to vocational schools, as well as vocational training within the dual system (Eurydice, 2020). Students who completed upper secondary education and received a higher education entrance qualification can choose from a wide range of different tertiary education institutions. Our sample reflects this diversity of educational paths and avoids different contextual structures, as all our respondents are educated in the same state (Baden-Württemberg) and not in different states with different educational legislation.

We contacted via email twelve schools of different types and with different age groups in areas close to our research site (Rhine Neckar region in the Federal State Baden-Württemberg), receiving nine refusals and three commitments. The refusals were based on issues of time constraints, as schools have a strict curriculum. Two other schools were contacted and agreed to participate, but due to Covid-19 and the related school closures in spring 2020, the survey could not take place. Because the sample was not drawn randomly and is based on a non-probability, convenience sampling strategy, the results cannot be generalized to all young adults. As the survey took place under our supervision, the selection criterion was the proximity of the school. There were no other exclusion criteria. The headmasters permitted us to speak to all the pupils of specific class levels. Participants first received a consent form and were informed that they may stop at any time of the survey without consequences and that the results would be published anonymously. The questionnaires were distributed to the teachers in advance so that they could access the appropriateness. Participants received no financial remuneration.

In addition, we assume that not only personal participation in demonstrations influences political attitudes, but that watching individuals from one's own in-group taking to the streets can also affect satisfaction with democracy. The priming for FFF makes youth collective identity salient and since youth generally have a strong sense of belonging, watching others demonstrating also increases the likelihood of the individuals participating themselves (e.g., Klandermans et al., 2002). We therefore decided not only to analyze the direct impact of non-institutionalized participation, but also the indirect impact of priming respondents for their own age group's activity.

We draw our sample from three schools in the Rhine-Neckar region in Germany as well as from an introductory lecture at Heidelberg University. Of our total of 335 respondents, 152 respondents were students from the university, 79 respondents were students from a vocational school, and 107 respondents were pupils from lower and upper secondary schools. All participants filled out the questionnaires, meaning we have a response rate of 100%, however, not for all questions. We collected the data from December 2019 to February 2020. During the survey, research assistants were available to answer any potential questions and to check that respondents did not communicate with each other; thus, they did not recognize that two different types of questionnaires were handed out. The questionnaires were coded manually by five research assistants independently to check for potential coding errors. To take the sample size into account, we relied on descriptive statistics and logit regressions with a small number of covariates. Due to the varying number of cases per educational system, we applied frequency weights throughout our analysis.

The study is separated into two parts: As a first step, we look at the full sample to find out how an individual's experiences in protests and school influence their political attitude. As a second step, we use the priming experiment and build subsamples to find out whether the priming for FFF influences the relationship described above.

Variables and Data

Before we present the results of our analyses, we shortly introduce the variables we used. The dependent variable, “satisfaction with democracy,” is measured using the validated survey item “How satisfied or dissatisfied are you—all in all—with democracy as it exists in Germany?” (Shell Youth Study, 2010). The respondents could answer on a 5-point Likert scale. We dichotomized the answers because analytical diagnostics indicate that we need to reject linear and ordinal model estimations. Perceived political responsiveness is measured using the statement “The interests of students (or: pupils) are not considered in politics,” to which respondents could position themselves on a 5-point Likert scale. This item is based on the ISSP Research Group (2016); however, we made the questions specific to youth. Here, the assumptions for the ordinary least square regression were met, which is why we kept the answer categories. Regarding our explanatory variables, we asked respondents whether they had “already participated in a protest meeting or demonstration.” This item is part of a battery on political participation that is based on the Shell Youth Study (2010). Equal treatment in school was measured with the statement “I was treated by the teachers just like everyone else” on a 5-point Likert scale. Professional preparation is a summative index of the items “My school education prepared me well for professional life” and “I received sufficient information from the school about different career paths.” The items for equal treatment in school and professional preparation are used in various educational surveys, such as the New Jersey School Climate Survey (2012).

We also include socio-demographic controls in our analysis: gender, voting age, political left-right orientation, and political efficacy1. Anderson and Singer (2008) find that dissatisfaction with the political system is more likely to be high among those who tend to be left on the right-left scale. Political self-efficacy is also found to increase satisfaction with democracy. People with a high internal political self-efficacy are more likely to participate and are more likely to believe that their activity is heard on the political level (Verba et al., 1995). Additionally, we expect men to be more satisfied than women (Schäfer, 2013). We also include a variable for voting age, arguing that those who are eligible to vote have more experience with the political system and are thus more satisfied. A summary of the descriptive statistics can be found in Appendix 1 in Supplementary Material. We pretested the survey (n = 15) to correct misunderstandings and inaccuracies.

Empirical Results: the Effects of Experiences in Protests and Schools on Political Attitudes

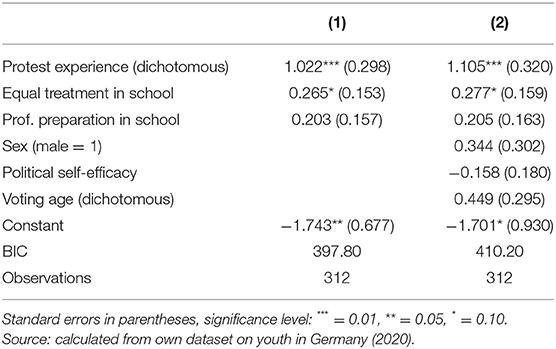

To test hypotheses 1, 3, 5, and 6—which analyze the influence of participation in demonstrations on perceived political responsiveness and satisfaction with democracy among youth—we calculated linear and logit regressions with stratification by units. Since respondents from one school may have different (unobserved) characteristics to respondents from other schools, it is necessary to group them (Kreuter and Valliant, 2007). The remaining two hypotheses on the priming effect are mainly tested using descriptive statistics, mean value comparisons and some restricted regression models. We also apply a survey data analysis in Stata to take our non-probability, convenience sampling into account. To summarize, in this first part of the empirical analysis, we want to find out whether equal treatment in school and professional preparation in school as continuous sources of political socialization have the same or higher effect on specific and diffuse system support as experiences in protest participation. We start by looking at satisfaction with democracy. The results of the weighted logit regressions are presented in Table 1. We use the Bayesian-Information-Criterion (BIC) for assessing model fit because it is less liberal by controlling for sample size.

While column 1 shows the results of the model without controls, column 2 presents the results with gender, voting age, self-efficacy and left-right orientation as controls. The effects for experiences in school and protest participation remain robust; however, the BIC specifies the best model fit for column one, where controls are excluded. In both columns, we can see a positive significant effect for protest participation. If a young adult has taken part in demonstrations, (s)he is more likely to be satisfied with how democracy works than a person who has not. The predictive probability increases from 0.48 to 0.72 if somebody has taken to the streets on at least one occasion. This finding is in line with the critical citizen thesis and supports our expectations outlined in hypothesis 3. Moreover, equal treatment in school increases satisfaction with democracy at a 10% level. While a person that was treated unequally in school has a predicted probability of 0.39 of being satisfied with democracy, an individual who has been treated equally has a predicted probability of 0.65. This supports hypothesis 5. The effect sizes of protest experience and equal treatment in school are comparable. All other variables, including the vocational training component of schools, have no significant effect on satisfaction with democracy. Therefore, we have to reject hypothesis 6 on the effect of vocational training on satisfaction with democracy.

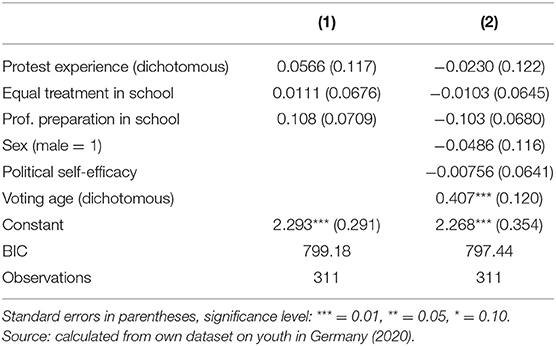

Having found that personal protest experience and equal treatment in school both positively affect satisfaction with democracy, we estimate a linear weighted regression for perceived political responsiveness as a political attitude indicating specific system support. We expected in hypothesis 1 the participation in protest to have a negative effect on satisfaction with democracy. In Table 2, the results of the weighted OLS regression are presented.

The results are again divided into a core model and a model with controls. Both models report no statistical influence for our independent variables. Neither socialization in school nor personal protest experience influence whether respondents believe that politicians care about the interests of young adults. This is an interesting finding, as it highlights that perceived political responsiveness is neither influenced by school experiences nor by protest experience. This refutes hypothesis 1. Nevertheless, we find a positive significant effect for voting age, as respondents over the age of 18 are more likely to perceive politicians as responsive.

n our model specifications, we excluded other controls, such as social class and ethnicity. It is plausible that individuals from higher social classes and with no migration background report higher values of satisfaction with democracy and perceived responsiveness. In Appendixes 3 and 4 in Supplementary Material, we report models that include nationality and the financial situation of the parents as controls. Both control variables are insignificant and protest participation also remains significant for explaining satisfaction with democracy at the 1% significance level. However, while we find an effect at the 10% significance level for equal treatment in school in the model without controls, this effect loses its significance in those with controls. The models for perceived political responsiveness are comparable to the new model specification. Due to our small degrees of freedom, we did not include all sociodemographic and socioeconomic controls in our models. Voting age, gender and political self-efficacy are more closely related to our sociological and educational reasoning, which is why we focus on this set of controls in the paper. Including socio-economic factors would interfere with the stringency of this article, though future research should investigate the effects of these.

Priming Experiment: Does FFF Priming Influence Political Attitudes?

To examine the influence of the FFF protests on perceived responsiveness and satisfaction with democracy, we use a priming experiment. With this empirical strategy, we test hypotheses 2 and 4, which concern the effect of priming for FFF on satisfaction with democracy and perceived responsiveness. While we expect FFF priming to increase satisfaction with democracy (hypothesis 4), we argue that perceived responsiveness will decrease if a respondent has been primed for this youth protest movement (hypothesis 2). Priming describes the psychological consideration that external stimuli can activate certain memories, so-called “stored knowledge” (Higgins, 1996; Higgins and Eitam, 2014). Keeter et al. (2002) recommend survey experiments, also a form of priming, to measure political participation since this method can reduce social desirability.

In this case, we assigned FFF questions randomly to some respondents, while others were directly asked about their political attitudes. Respondents from all four schools/universities received the same questions; thus, all schools/universities were divided into treatment and control groups. We used a simple randomization method, meaning that the order of the distributed questionnaires was random, and we did not select specific respondents to receive either of the two questionnaires. The priming consisted of four questions on climate change, environmental protests and FFF. While two general questions on climate change were based on the Shell Youth Study (2010), we had to develop two questions regarding FFF ourselves, as there are few FFF surveys to date. These four questions were placed at the top of the survey and only slightly increased its length. The respondents did not recognize that two types of questionnaires were filled out in the classroom. A few weeks later, we visited the schools and made the procedure completely transparent and presented the results. The priming of the four questions on climate change and FFF are expected to remind respondents of the FFF movement and to adjust their opinions accordingly. Not only do we expect this to have the same effect direction as general protest participation, we argue that FFF priming will also increase the effect sizes. If somebody has just been reminded of the climate change movements led by youths, (s)he will consider herself/himself as belonging to a certain age group and is therefore likely to evaluate the following questions differently. The salience of young individuals taking to the streets is considered to influence the response behavior of young individuals especially.

The treatment group consisted of n = 150 individuals, while the control group consisted of n = 182 individuals. In the regression models, we have a maximum of 12 missing cases due to missing answers on our three independent variables. The percentage of absences in both groups is between 1 and 5%, which seems acceptable. Due to our use of randomization and specific priming, there is a higher probability that our variance in the perceived responsiveness traces back to the FFF priming. For the following analysis, we used the item “How do you feel about the Fridays for Future movement?” We coded all answers as one for the treatment group, while the control group's missing answer was coded as zero.

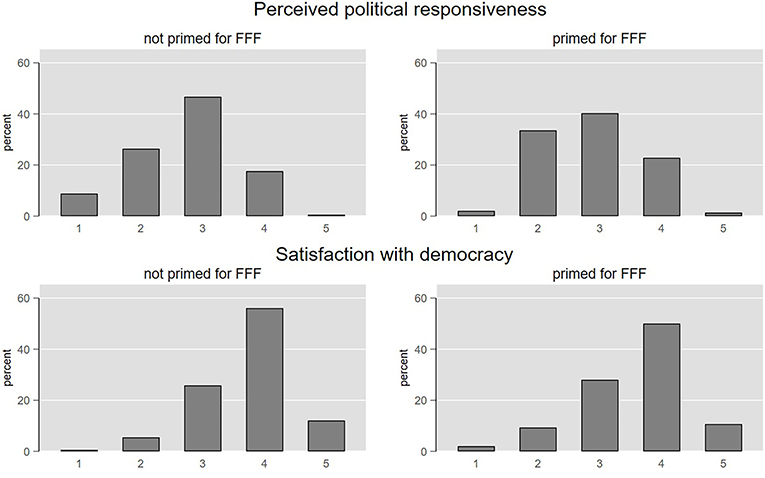

First, we plotted the answer categories on perceived political responsiveness regarding the demands of youths and satisfaction with democracy separated by our two samples in bar charts (see Figure 1). Higher values indicate higher perceived responsiveness and higher satisfaction with democracy. The graph demonstrates that individuals primed for FFF protests differ somewhat from those not primed. While 18% of those who were not primed consider politicians as responsive (category 4 and 5), 24% of those who were primed agree with this statement. This descriptive finding contradicts our expectations because it shows that FFF priming (slightly) increases perceived political responsiveness. Based on these descriptive findings, we can partly confirm hypothesis 2 on the negative effect of FFF priming on perceived political responsiveness. Respondents not being primed classify themselves more often in category 3 (46 vs. 40%), making it “neither true nor wrong” that the interests of youths are not heard by politicians. The graph below in Figure 1 presents the findings for satisfaction with democracy. Here, we see that satisfaction with democracy is higher for those not primed: 68% indicated that they are satisfied or very satisfied, while only 60% of those primed fell into these categories. This contradicts our hypothesis 4 since we argued that priming increases satisfaction with democracy. To find out whether these descriptive statistics are significant, we calculate Pearson's Chi2 test for perceived political responsiveness and satisfaction with democracy. The results for political responsiveness indicate statistically significant differences. Thus, Thus, individuals who have been primed for FFF perceive politicians as more responsive than those who have not been primed further supporting hypothesis 2. Regarding satisfaction with democracy, we find no statistically significant differences. Thus, the results from the bar chart do not indicate that youths primed for FFF are statistically significantly less likely to be satisfied with democracy.

Figure 1. Bar charts for priming effect on political attitudes. Source: calculated from own dataset on youth in Germany (2020).

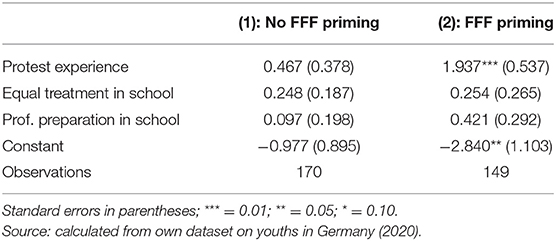

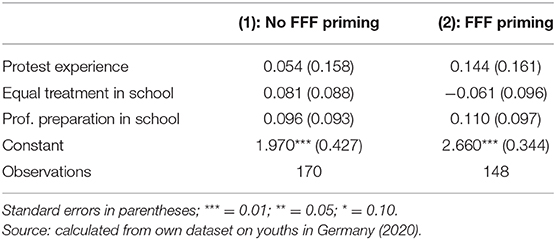

Finally, we calculated the models from the beginning again using subsamples to find out whether the FFF movement influences the effects of protest experience and equal treatment in school. The results for satisfaction with democracy are presented in Table 3, and the results for perceived political responsiveness are in Table 4. However, we include no controls due to the small sample sizes. We start with diffuse system support (satisfaction with democracy) and proceed to specific system support (perceived political responsiveness).

Table 4. Weighted linear regression for subjective political responsiveness with priming subsamples.

Thus, young adults who have engaged in non-institutionalized forms of political participation (here: demonstrations) are more likely to be satisfied with the political system when primed for FFF. This could indicate that not the individual protest participation as such influences satisfaction with democracy, but the specific priming for FFF. Only if primed for FFF does protest experience influence satisfaction with democracy. This highlights that FFF might affect the political attitudes of young adults. However, we do not know whether individuals gathered their protest experiences in FFF-related protests or in other kinds of demonstrations. The other variables indicate no significant effects.

Next, we look at whether the effect of protest and school experiences on perceived political responsiveness differs between those primed and those not primed. Table 4 exhibits no significant effects. This is comparable to Table 2 and highlights that neither protest experience nor equal treatment in school influences political responsiveness and that the FFF movement makes no difference. This is interesting, since we expected specific system support to vary more and to be more influenced by protest experiences. On the other hand, this finding is cause for optimism, as it highlights that the perception of specific policies, parties and politicians is not influenced by what pupils learn in school.

Discussion and Conclusion

This article adds to the literature on the political attitudes of young adults. The main focus was to find out whether non-institutionalized political participation influences young people's perceptions of the responsiveness of politicians and their satisfaction with democracy. 2019 was the year of the climate strike: During the Global Week for Future, roughly six million people in 150 countries took part in protests calling on politicians to take action regarding climate change (The Guardian, 2019). We compared protest experience and youth activism in FFF with other skills that this demographic learns in school, to find out which factor makes a larger difference: the continuous skills that young adults learn in the educational system, or single events of political protest?

We found for our full sample of German pupils and students (n = 338) that equal treatment in school and protest experience increase satisfaction with democracy, while professional preparation in school has no effect on diffuse system support. The effect sizes were almost equal in the weighted logit regressions. Neither non-institutionalized participation nor socialization in school influences perceived political responsiveness. This highlights that theories of participation and socialization cannot explain this case of specific system support.

In a next step, we divided the sample into two groups, relying on a priming experiment where respondents were primed for their in-group's participation in the FFF movement. Here, we wanted to know how this large event influences specific and diffuse system support. In comparison to the first part, we did not ask for the individual's protest participation but primed them for the climate activism of their generation. One the one hand, FFF is a movement through which young adults make their demands heard. On the other, the political success has not been resounding, as the objectives of FFF have not yet been (fully) achieved. So how does this very visible but not fully successful movement affect its own generation, namely young adults? What perception of the responsiveness of politicians and of satisfaction with democracy do young adults have in the context of FFF? Surprisingly, the results show that political responsiveness is higher among those who were primed, while satisfaction with democracy is not influenced by FFF priming. We hypothesized that FFF priming would decrease perceived political responsiveness and increase satisfaction with democracy. To explain the different results between the treatment and control group, we estimated subsample regressions. Here, we found for those who had been primed that their protest experience influenced their satisfaction with democracy. Protest experience has no effect on satisfaction with democracy if the person has not been primed for FFF. However, we do not know whether they gathered their individual protest experiences in FFF or in other kinds of political demonstrations. These findings highlight that FFF has changed the political attitudes of young adults and thus represents an “exogenous shocks.”

Since young adults spend most of their time at school, one could regard schools as central agents of socialization, surpassing the effect of single protest events. The results of our study found the former to be almost as uninfluential as the latter. Socialization in school, neither in terms of equal treatment nor in terms of vocational preparation, does influence whether respondents believe that politicians care about the interests of youths. However, regarding satisfaction with democracy, we were able to show that equal treatment in school is likely to increase satisfaction with democracy. Thus, the school as a socialization agent is relevant to the development of diffuse support for the political system among young adults. This implies that a closer look at how schools promote citizenship education is necessary. Within schools, pupils need to learn both abstract political knowledge and practical ways of getting involved in the political process.

Furthermore, the political attitudes of youth need to be analyzed in more detail. The results for diffuse and specific regime support differed: While system-related attitudes, such as satisfaction with democracy, are positively influenced by protest participation, policy- and government-related attitudes (here: political responsiveness) are not much influenced by protest participation. Future research should therefore examine more precisely how different settings of socialization—school, social networks and friends, and engagement in political activities—influence the various political attitudes of the youth. This is the first study to have combined political participation and socialization theories to explain two types of political attitudes among young adults. Further studies on political youth would improve our understanding of why some young adults are politically frustrated or alienated while others have positive attitudes.

Another starting point for future research would be to focus on specific age groups. We found that youth who are 18 years or older to be more likely to perceive politicians as responsive. It could be fruitful to study whether the legal voting age of 18 leads to lower scores in political performance evaluation. This question also points to the ongoing debates in many European countries, including Germany, as whether the voting age should be lowered (Deutsche Welle, 2020).

A particular strength of our study is the composition of the interviewed sample. By gathering original data, we were able to generate a sample that consists of young adults from very different educational backgrounds, ranging from lower secondary school pupils to vocational pupils and University students. In comparison to other studies, we did not interview participants in demonstrations but young adults in general. This enabled us to implement a priming experiment, which would not have been useful with a sample of demonstration participants, as they would likely have had a strongly positive perception of the FFF movement, meaning the results would not have reflected the perception of the general population of young adults. Experimental research designs are still rare in this research field despite its advantages regarding causality.

Nevertheless, the study also has its weaknesses. These are related to the sample that is not representative and was randomly drawn due to the lack of access to other schools. Moreover, our sample could not be enlarged because of the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic. The school closures in Germany made it impossible to interview more pupils. Furthermore, a survey under these conditions would not have been useful, as the pandemic has probably affected young people's perceptions of the responsiveness of politicians, as well as their satisfaction with democracy. As a result, our hypotheses should also be checked with another, non-convenience sample and within different contexts to draw more general conclusions. Another drawback is the measurement of individuals' protest participation where we did not explicitly refer to FFF. The rationale for using a generalized question on protest participation was that it would be more comparable to other types of political participation, such as signing petitions. Since climate strikes were by far the largest and most frequent types of protest in 2019, we assume that those who indicated having participated in protests to have a high likelihood of having participated in climate demonstrations. In addition, to better understand the relationship between experiences at school and the protest participation experiences of young adults and their political attitudes, studies in the form of in-depth interviews with young adults are an important next step. Nevertheless, this study still produced interesting findings, providing a starting point for further research. To our knowledge, it is one of the first non-descriptive study on FFF, which is surprising given the movement's empirical importance.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the teachers and the participants.

Author Contributions

A-MP and JW contributed the conception and design of the article, did the manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version. A-MP performed the statistical analysis. All authors wrote parts of the manuscript.

Funding

This article benefited from financial support by the project Change through Crisis? Solidarity and Desolidarization in Germany and Europe (Solikris; Federal Ministry of Education and Research of Germany), the Baden-Württemberg Ministry of Science, Research and Arts and Heidelberg University.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the reviewers for their helpful suggestions and comments. Karin Sledge, Christin Heinz-Fischer, and Annika Püschner deserve credit for their assistance in conducting the interviews and coding. We also wish to express appreciation to Laurence Crumbie for proof-reading the paper. Also, we thank all participants at ECPR General Conference 2020 for their comments. The authors would like to expressly thank all participating schools for their support and the trust they have placed in us. Without the willingness of the students to participate in the study, this article would not have been possible.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2020.611139/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^Indicators of nationality and social class are also in our sample. However, we did not include them in the models here. This is based on two reasons: First, the degrees of freedom are too small when controlling for these factors as well. Second, economic and ethnic inequalities would open up another area—political economy—which is less relevant to this study, since we are already integrating two large strings of literature. However, we can state that we did not find any statistically significant effects for these two dimensions of inequality.

References

Allen, N., and Birch, S. (2015). Process preferences and british public opinion: citizens' judgements about government in an era of anti-politics. Polit. Stud. 63, 390–411. doi: 10.1111/1467-9248.12110

Anderson, C. J., and Singer, M. (2008). The sensitive left and the impervious right. Multilevel models and the politics of inequality, ideology, and legitimacy in Europe. Comp. Polit. Stud. 41, 564–599. doi: 10.1177/0010414007313113

Assor, A., Kaplan, H., Kanat-Maymon, Y., and Roth, G. (2005). Directly controlling teacher behaviors as predictors of poor motivation and engagement in girls and boys: the role of anger and anxiety. Learn. Instr. 15, 397–413. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2005.07.008

Banks, M. H., and Roker, D. (1994). The political socialization of youth: exploring the influence of school experience. J. Adolesc. 17, 3–15. doi: 10.1006/jado.1994.1002

Bernauer, J., Giger, N., and Rosset, J. (2015). Mind the gap: do proportional electoral systems foster a more equal representation of women and men, poor and rich. Int. Polit. Sci. Rev. 36, 78–98. doi: 10.1177/0192512113498830

Campbell, D. E. (2008). Voice in the classroom: how an open classroom climate fosters political engagement among adolescents. Polit. Behav. 30, 437–454. doi: 10.1007/s11109-008-9063-z

Claes, E., and Hooghe, M. (2008). “Citizenship education and political interest: political interest as an intermediary variable in explaining the effects of citizenship education,” in Paper Presented at the Conference on Civic Education and Political Participation, 104th Edn. (Boston, MA: American Political Science Association), 28–31.

Claes, E., Hooghe, M., and Stolle, D. (2009). The political socialization of adolescents in Canada: differential effects of civic education on visible minorities. Can. J. Polit. Sci. 42, 613–636. doi: 10.1017/S0008423909990400

Cleary, M. (2007). Electoral competition, participation, and government responsiveness in Mexico. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 51, 283–299. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5907.2007.00251.x

Crepaz, M., Bodnaruk Jazayeri, K., and Polk, J. (2017). What's trust got to do with it? The effects of in-group and out-group trust on conventional and unconventional political participation. Soc. Sci. Q. 98, 261–281. doi: 10.1111/ssqu.12271

Dahl, V., Amnå, E., Banaji, S., Landberg, M., Šerek, J., and Ribeiro, N. (2017). Apathy or alienation? Political passivity among youths across eight European Union countries. Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 15, 284–301. doi: 10.1080/17405629.2017.1404985

Deutsche Welle (2020). Wählen schon mit 16? Retrieved from: https://www.dw.com/de/w%C3%A4hlen-schon-mit-16/a-54430089

Easton, D. (1975). A re-assessment of the concept of political support. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 5, 435–457. doi: 10.1017/S0007123400008309

Eckstein, K., Noack, P., and Gniewosz, B. (2012). Attitudes toward political engagement and willingness to participate in politics: trajectories throughout adolescence. J. Adolesc. 35, 485–495. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2011.07.002

Elsässer, L., Hense, S., and Schär, A. (2018). Government of the People, by the Elite, for the Rich. Unequal Responsiveness in an Unlikely Case. MPIfG Discussion Paper 18/5. Cologne: Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies.

Esaiasson, P., Kölln, A., and Turper, S. (2015). Research note. external efficacy and perceived responsiveness—similar but distinct concepts. Int. J. Public Opin. Res. 27, 432–445. doi: 10.1093/ijpor/edv003

Esaiasson, P., and Wlezien, C. (2017). Advances in the study of democratic responsiveness: an introduction. Comp. Polit. Stud. 50, 699–710. doi: 10.1177/0010414016633226

Eurydice (2020). Germany Overview. Available online at: https://eacea.ec.europa.eu/national-policies/eurydice/content/germany_en (accessed October 11, 2020).

Ferreira, P. D., Azevedo, C. N., and Menezes, I. (2012). The developmental quality of participation experiences: beyond the rhetoric that ‘participation is always good!' J. Adolesc. 35, 599–610. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2011.09.004

Field, E. (2017). Climate change: imagining, negotiating, and co-creating future(s) with children and youth. Curr. Perspect. 37, 83–89. doi: 10.1007/s41297-017-0013-y

Flanagan, C. A., Cumsille, P., Gill, S., and Gallay, L. S. (2007). School and community climates and civic commitments: patterns for ethnic minority and majority students. J. Educ. Psychol. 99, 421–431. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.99.2.421

Foran, J., Gray, S., and Grosse, C. (2017). Not yet the end of the world: political cultures of opposition and creation in the Global youth climate justice movement. J. Soc. Mov. 9, 353–379. Available online at: http://www.interfacejournal.net/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Interface-9-2-Foran-Gray-Grosse.pdf

Gilens, M. (2012). Affluence and Influence: Economic Inequality and Political Power in America. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Goubin, S. (2020). Economic inequality, perceived responsiveness and political trust. Acta Polit. 55, 267–304. doi: 10.1057/s41269-018-0115-z

Grimes, M. (2006). Organizing consent: the role of procedural fairness in political trust and compliance. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 45, 285–315. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6765.2006.00299.x

Grimes, M., and Esaiasson, P. (2014). Government responsiveness: a democratic value with negative externalities? Polit. Res. Q. 67, 758–776. doi: 10.1177/1065912914543193

Hibbing, J. R., and Theiss-Morse, E. (2001). Process preferences and american politics: what the people want government to be. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 95, 145–54. doi: 10.1017/S0003055401000107

Higgins, E. T. (1996). “Knowledge activation: accessibility, applicability, and salience,” in Social Psychology: Handbook of Basic Principles, eds E. T. Higgins and A. W. Kruglan-ski (New York, NY: Guilford), 133–168.

Higgins, E. T., and Eitam, B. (2014). Priming shmiming: it's about knowing when and why stimulated memory representations become active. Soc. Cogn. 32, 97–114. doi: 10.1521/soco.2014.32.supp.225

Hopkins, V., Klüver, H., and Pickup, M. (2018). The influence of cause and sectional group lobbying on government responsiveness. Polit. Res. Q. 72, 1–14. doi: 10.1177/1065912918796326

ISSP Research Group (2016). International Social Survey Programme: Citizenship II - ISSP 2014, ZA6670 Data file Version 2.0.0. Cologne: GESIS Data Archive. doi: 10.4232/1.12590

Jennings, M. K. (1979). Another look at the life cycle and political participation. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 23, 755–771. doi: 10.2307/2110805

Jennings, P. A., and Greenberg, M. T. (2009). The prosocial classroom: teacher social and emotional competence in relation to student and classroom outcomes. Rev. Educ. Res. 79, 491–525. doi: 10.3102/0034654308325693

Keeter, S., Jenkins, K., Zukin, C., and Andolina, M. (2003). “Three core measures of community-based civic engagement: evidence from the youth civic engagement indicators project,” in Paper Presented at the Child Trends Conference on Indicators of Positive Development (Washington, DC), 11.

Keeter, S., Zuking, C., Andolina, M., and Jenkins, K. (2002). Improving the Measurement of Political Participation. Chicago, IL: Annual Meeting of the Midwest Political Science Association.

Kjeldgaard, D., and Askegaard, S. (2006). The glocalization of youth culture: the global youth segment as structures of common difference. J. Consum. Res. 33, 231–247. doi: 10.1086/506304

Klandermans, B., Sabucedo, J. M., Rodriguez, M., and De Weerd, M. (2002). Identity processes in collective action participation: farmers' identity and farmers' protest in the Netherlands and Spain. Polit. Psychol. 23, 235–251. doi: 10.1111/0162-895X.00280

Kreuter, F., and Valliant, R. (2007). A survey on survey statistics: what is done and can be done in Stata. Stat. J. 7, 1–21. doi: 10.1177/1536867X0700700101

Lenzi, M., Vieno, A., Sharkey, J., Mayworm, A., Scaahi, L., Pastore, M., et al. (2014). How school can teach civic engagement besides civic education: the role of democratic school climate. Am. J. Commun. Psychol. 54, 251–261. doi: 10.1007/s10464-014-9669-8

Mansbridge, J. J. (2003). Rethinking representation. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 97, 515–528. doi: 10.1017/S0003055403000856

Marquardt, J. (2020). Fridays for future's disruptive potential: an inconvenient youth between moderate and radical ideas. Front. Commun. 5:48. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2020.00048

Martini, S., and Quaranta, M. (2019). Political support among winners and losers: within- and between-country effects of structure, process and performance in Europe. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 58, 341–361. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12284

Miklikowska, M., and Hurme, H. (2011). Democracy begins at home: democratic parenting and adolescents' support for democratic values. Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 8, 541–557. doi: 10.1080/17405629.2011.576856

Miller, A. H., and Listhaug, O. (1999). “Political performance and institutional trust,” in Critical Citizens: Global Support for Democratic Government, ed P. Norris (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 204–216. doi: 10.1093/0198295685.003.0010

New Jersey School Climate Survey (2012). School Climate Survey: Middle-High School Students. Available online at: https://www.state.nj.us/education/students/safety/behavior/njscs/NJSCS_MSHS_Student_Q.pdf

Niemi, R. G., and Klingler, J. (2012). The development of political attitudes and behaviour among young adults. Aust. J. Polit. Sci. 47, 31–54. doi: 10.1080/10361146.2011.643167

Norris, P. (1999). “Conclusions: the growth of critical citizens and its consequences,” in Critical Citizens. Global Support for Democratic Government, ed P. Norris (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 257–272. doi: 10.1093/0198295685.003.0013

O'Toole, T., Lister, M., Marsh, D., Jones, S., and McDonagh, A. (2003). Turning out or left out? Participation and non-participation among young people. Contemp. Polit. 9, 45–61.

Özdemir, S. B., Stattin, H., and Özdemir, M. (2016). Youth's initiations of civic and political discussions in class: do youth's perceptions of teachers' behaviors matter and why? J. Youth Adolesc. 45, 2233–2245. doi: 10.1007/s10964-016-0525-z

Page, B., Bartels, L., and Seawright, J. (2013). Democracy and the policy preferences of wealthy americans. Perspect. Polit. 11, 51–73. doi: 10.1017/S153759271200360X

Papadopoulos, Y., and Warin, P. (2007). Are innovative, participatory and deliberative procedures in policy making democratic and effective? Eur. J. Polit. Res. 46, 445–472. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6765.2007.00696.x

Pasek, J., Feldman, L., Romer, D., and Hall Jamieson, K. (2008). Schools as incubators of democratic participation: building long-term political efficacy with civic education. Appl. Dev. Sci. 12, 26–37. doi: 10.1080/10888690801910526

Quintelier, E. (2007). Differences in political participation between young and old people. Contemp. Polit. 13, 165–180. doi: 10.1080/13569770701562658

Quintelier, E. (2013). Engaging adolescents in politics: the longitudinal effect of political socialization agents. Youth Soc. 47, 51–69. doi: 10.1177/0044118X13507295

Quintelier, E., and Hooghe, M. (2012). Political attitudes and political participation: a panel study on socialization and self-selection effects among late adolescents. Int. Polit. Sci. Rev. 33, 63–81. doi: 10.1177/0192512111412632

Quintelier, E., and Van Deth, J. W. (2014). Supporting democracy: political participation and political attitudes. Exploring causality using panel data. Polit. Stud. 62, 153–171. doi: 10.1111/1467-9248.12097

Resh, N., and Sabbagh, C. (2014). Sense of justice in school and civic attitudes. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 17, 51–72. doi: 10.1007/s11218-013-9240-8

Schäfer, A. (2013). “Affluence, inequality and satisfaction with democracy,” in Society and Democracy in Europe, eds S. I. Keil and O. W. Gabriel (London: Routledge), 139–161.

Shell Youth Study (2010). Jugend 2010. 16. Shell Jugendstudie. Hamburg: Deutsche Shell Holding GmbH.

Tepe, M., and Vanhuysse, P. (2010). Elderly bias, new social risks, and social spending: investigating change and timing in eight programs across four worlds of welfare, 1980–2003. J. Eur. Soc. Policy 20, 217–234. doi: 10.1177/0958928710364436

The Guardian (2019). Climate Crisis: 6 Million People Join Latest Wave of Global Protests. Retrieved from: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/sep/27/climate-crisis-6-million-people-join-latest-wave-of-worldwide-protests

Tomasika, M. J., Hardy, S., Haase, C. M., and Heckhausen, J. (2009). Adaptive adjustment of vocational aspirations among German youths during the transition from school to work. J. Vocat. Behav. 74:38–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2008.10.003

Torney-Purta, J. (2002). The school's role in developing civic engagement: A study of adolescents in twenty-eight countries. Appl. Dev. Sci. 6, 203–212. doi: 10.1207/S1532480XADS0604_7

Tyler, T. R., and Blader, S. L. (2000). Cooperation in Groups: Procedural Justice, Social Identity, and Behavioral Engagement. Philadelphia, PA: Psychology Press.

Verba, S., Schlozman, K. L., and Brady, H. E. (1995). Voice and Equality. Civic Voluntarism in American Politics. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Wahlström, M., de Moor, J., Uba, K., Wennerhag, M., and De Vydt, M. (Eds.). (2020). Protest for a Future II: Composition, Mobilization and Motives of the Participants in Fridays For Future Climate Protests on 20–27 September, 2019 in 19 Cities Around the World. Retrieved from: https://protestinstitut.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/20190709_Protest-for-a-future_GCS-Descriptive-Report.pdf

Wahlström, M., Kocyba, P., De Vydt, M., and de Moor, J. (Eds.). (2019). Protest for a Future: Composition, Mobilization and Motives of the Participants in Fridays for Future Climate Protests on 15 March, 2019 in 13 European Cities. Retrieved from: https://www.tu-chemnitz.de/phil/iesg/professuren/klome/forschung/ZAIP/Dokumente/Protest_for_a_future_GCS_Descriptive_Report.pdf

Weiss, J. (2020). What is youth political participation? Literature review on youth political participation and political attitudes. Front. Polit. Sci. 2:1. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2020.00001

Keywords: participation, youth, Fridays for Future, satisfaction with democracy, perceived responsiveness, priming, school experiences, survey experiment

Citation: Parth A-M, Weiss J, Firat R and Eberhardt M (2020) “How Dare You!”—The Influence of Fridays for Future on the Political Attitudes of Young Adults. Front. Polit. Sci. 2:611139. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2020.611139

Received: 28 September 2020; Accepted: 01 December 2020;

Published: 22 December 2020.

Edited by:

Isabel Menezes, University of Porto, PortugalReviewed by:

Antonella Guarino, University of Bologna, ItalyJasmine Lorenzini, Université de Genève, Switzerland

Copyright © 2020 Parth, Weiss, Firat and Eberhardt. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Anne-Marie Parth, YW5uZS1tYXJpZS5wYXJ0aEBpcHcudW5pLWhlaWRlbGJlcmcuZGU=

Anne-Marie Parth

Anne-Marie Parth Julia Weiss

Julia Weiss Rojda Firat

Rojda Firat