- Faculty of Education, The University of Hong Kong, Pokfulam, Hong Kong

Youth have often been described as politically apathetic or disengaged, particularly with respect to more conventional forms of participation. However, they tend to prefer non-institutionalized modes of political action and they may express themselves on the Internet. Young people have also been recognized as having a “latent preparedness” to get politically active when needed. This paper reports forms of offline and online participation adopted by young adults in Hong Kong who were surveyed shortly before the anti-extradition bill social movement of 2019 and 1 year later. The results tentatively suggest that young adults may not be very active in politics when they do not perceive the need to bring about change. However, they are involved in expressive activities and on the Internet more broadly, and ready to turn their latent participation into concrete political participation when they are dissatisfied with government actions and believe it is their responsibility to act against laws perceived to be unjust. Cross-sectional and cross-lagged panel analyses show that youth’s participation in offline political activities is associated with their online participation. Positive effects of past experiences in each mode on participation in offline and online political activities show the mobilizing potential of social media and provide support for the reinforcement hypothesis, though previous participation in offline activities appears as a better predictor of political participation when compared with prior participation on the Internet.

Introduction

Young people have often been described as apolitical because of their low levels of participation in institutionalized political activities, yet youth are active in non-institutionalized and “latent” forms of political participation and prepared to take political action if needed (Amnå and Ekman, 2014; Fu et al., 2016; Weiss, 2020). The rise of the Internet and social media has also created new modes of participation and opportunities for political mobilization (Reichert, 2020). Though there is debate as to whether online activities should be conceived of as forms of political participation as they may not directly aim to influence government decisions, creative uses of the Internet (e.g., creating videos, maintaining blogs) can empower young people (Ekström and Östman, 2015; Vromen et al., 2015). Some of these activities have been characterized as “expressive participation” (Skoric et al., 2016), though not all online political activities are considered as expressive (e.g., voting registration on the Internet).

Linking Online and Offline Political Participation

The link between offline and online political participation has been described by two opposing hypotheses. According to the mobilization thesis, new media can empower citizens and are particularly suited to reduce inequalities of participation among otherwise disengaged and uninterested individuals (Norris, 2001). Digital technologies facilitate more personalized pathways to political action and blur the distinction between non-political and political media use (Bennett, 2008). Bennett and Segerberg (2013) further use the term “connective action” to emphasize how the sharing of personalized contents on social media can be turned into political participation through crowd-enabled, organizationally-enabled, or organizationally-brokered action networks. For example, the digital technologies used for sharing nonpolitical content can be utilized by activists to organize themselves and otherwise politically uninterested individuals, particularly as digital platforms are considered more resistant toward government pressures (Zuckerman, 2015). Although a meta-analysis on research in Confucian regimes found a positive association between expression on social media and offline political participation, this association was stronger in democratic systems when compared with flawed democracies and authoritarian regimes (Skoric et al., 2016).

Importantly, discussions about political issues on social media can strengthen group identifications and motivate “connective action” (Bennett and Segerberg, 2013). The citizen communication mediation model of political participation further argues that exposure to political information increases the likelihood of involvement in political discussions, which can lead to political participation—and discussions via digital technologies appear to have particular relevance for political participation (Chan et al., 2017; Lee et al., 2013; Reichert and Print, 2017). Furthermore, theories of biased information processing and motivated skepticism suggest that online communication about political issues can promote (radical) offline political participation, and that the diversity of discussed perspectives may play a role (Zhu et al., 2020).

On the other hand, the reinforcement thesis argues that individuals who already are knowledgeable, interested, and active in traditional, offline forms of political activity will also use online modes, thus expanding their action repertoire and widening the participation gap (Norris, 2001). Though empirical evidence is mixed with some support for both theses, it appears somewhat more in favor of the latter. For example, Boulianne (2020) in her meta-analysis found a trend over time according to which social media use was increasingly and positively correlated with civic and political participation. However, it is possible that both mobilization and reinforcement processes are at work, yet longitudinal studies that could disentangle the causal link(s) between both modes of participation are rare.

Youth Political Participation in Hong Kong

Non-institutionalized as well as online forms of participation are particularly relevant in political systems with few opportunities to influence politics through institutionalized means, such as Hong Kong (Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU), 2020; Skoric et al., 2016). Citizenship is coined by a history of political apathy, as well as long-standing dissatisfaction with Hong Kong’s governments (Lam, 2018; Xia, 2016). However, youth appear quite active in the city, and the share of young adults among registered voters has been increasing (Low et al., 2016). In fact, the turnout gap between young adults and the entire voting population in the elections to the Legislative Council has been decreasing (Center for Youth Studies, 2017), and young adults were the most active group in the elections to the District Councils in 2019 (Chung, 2020).

Yet, young people in Hong Kong are concerned about the city’s future (Low et al., 2016). They have little trust and are dissatisfied with the prevalent political system, and they perceive electoral politics as ineffective (Lam, 2018). One reason is the power gap between civil society and the government, and the perception that politicians prioritize economic stability over political reform toward democracy (Lam-Knott, 2019). Youth in Hong Kong are also more willing to protest and to express their political opinions on social media than other age groups (Center for Youth Studies, 2017). Previous experiences in the Occupy Central movement are but one example (Chu and Yeo, 2020; Jackson et al., 2017). The rise of political activism is also signified by young adults’ awareness of political values and rights, an increasing willingness to challenge the political authority and mainstream social and political values, and the use of radical tactics (Lam, 2018).

Ng (2016) further showed that political events and the media are particularly important influences in young people’s decisions to join opposition parties in flawed democracies such as Hong Kong. European research suggests that users of digital media and participants in collective protests also appear more willing to cast a protest vote (Mosca and Quaranta, 2017), particularly if they are dissatisfied with specific policy issues (Birch and Dennison, 2019). In 2019, an opportunity to turn a latent preparedness to participate in politics arose in Hong Kong when the government pushed for a bill that would have allowed extradition to several countries and most notably to the Chinese mainland (Purbrick, 2019). As the government ignored the voice of the many people who through mass demonstrations demanded that the bill be abandoned, the protests quickly transformed into an anti-government movement adopting various forms of activism. Yet what had started as peaceful mass demonstrations turned into a spiral of police repressive action, political authoritarianism, and militant protests (Ku, 2020).

Lee et al. (2019) identified three key elements of the movement, including a coherent set of demands focusing on repressive politics and police tactics, a high level of solidarity among the protesters, and reliance on digital technology. For example, social media platforms were used for communication among protesters (e.g., where to get first aid kits or riot gear), and encrypted platforms were used to quickly coordinate protest actions (Ting, 2020). Besides common social movement tactics, such as strikes and rallies, other forms such as creating materials, choral singing, translating news articles or holding citizens’ press conferences emerged (Ku, 2020; Lee et al., 2019). Online expressive forms of participation, such as sharing information or posting messages to support the movement, were particularly widespread (Lee et al., 2019), and solidarity slogans, hate speech, and disciplinary tropes in online discussions were central to the solidarity of the movement (Lee, 2020).

A majority of the protesters had experienced some form of tertiary education and many of them were young adults (Lee et al., 2019). Furthermore, political discontent can motivate protest participation (van Stekelenburg and Klandermans, 2013), and Hong Kongers with higher education appear to be politically less satisfied than those with lower education (Wong et al., 2017). Hence, as institutionalized forms of participation in the political process remain limited in Hong Kong, one question was what forms of participation were adopted by university students. Another question was whether online participation was a precursor of offline participation in activities to support the movement, if the direction was rather from offline participation to online activities, or if it was a bidirectional relationship. While cross-sectional data can be helpful in understanding whether individuals who participate in politics through one mode also use the other mode of participation, only longitudinal designs can help disentangle the causal association. That is, only with longitudinal data is it possible to examine whether participation in one mode leads to, or increases, participation in the other mode.

Method

Data were collected online from 1,130 first-year students across all faculties at two major universities in Hong Kong in the spring of 2019 (t1). Students were asked about several aspects related to civic and political participation, including their previous and intended participation in online and offline activities. Here we focus on the 777 local students who provided valid responses at the time, reflecting 18% of all local freshmen at both universities.

In mid-2020, a second survey focusing on students’ opinions on and participation in the anti-extradition bill social movement in Hong Kong was sent out to all students who had given consent to be approached again (t2; including some students who had given consent to be contacted in the future but who had not completed the first survey in 2019). 408 local students provided valid responses in 2020. Three Hundred-Fifty Seven of these students had also completed the first questionnaire in 2019, reflecting 46% of the local students who had participated in t1.

Note that students of different gender and from different universities were not equally likely to have participated in the study in 2019. However, there were no significant differences among students who had and those who had not participated in both waves regarding the variables used in this analysis. Therefore, the data were weighted with respect to students’ gender and university affiliation at t1. Supplementary Table S1 summarizes the descriptive statistics of the relevant variables and their bivariate correlations for the panel sample (including their reliabilities).

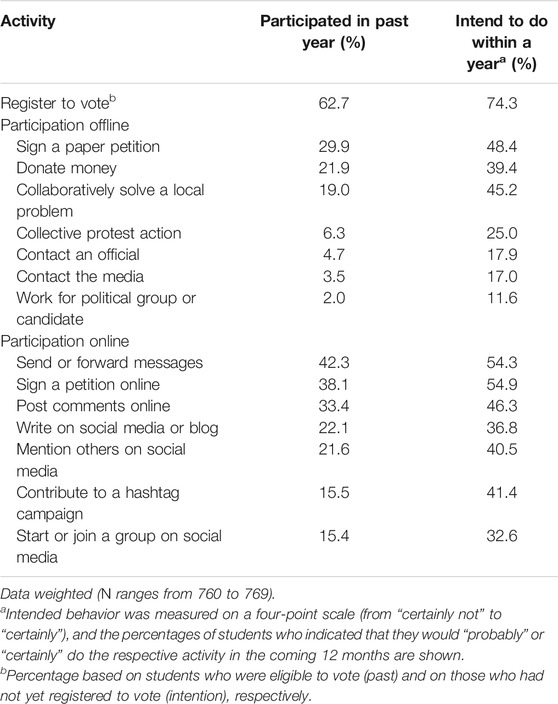

The analysis examined students’ self-reported participation in offline and online civic and political activities prior to the movement (t1; Table 1) and in support of the social movement (t2; Table 2). Cross-lagged multivariate logistic and linear regression analyses using the robust maximum likelihood estimator were conducted using Mplus (Muthén and Muthén, 1998–2017) to understand how collective protest action and online expressive participation as well as how offline and online participation more generally were associated over time (Supplementary Figure S1). Collective protest activities were measured by one item in 2019 (i.e., whether students had protested with others) and using two items in 2020 (i.e., whether students had participated in mass demonstrations and/or in university-based protests). Online expressive action was measured via two items that were comparable in both surveys: students indicated whether they had sent or forwarded political messages, and whether they had posted or replied political comments online.

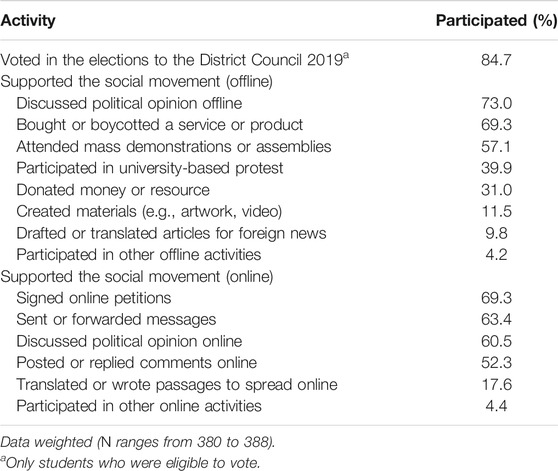

TABLE 2. Offline and online participation in the anti-extradition bill movement since June 2019 (t2).

More comprehensive measures of offline and online participation were also modeled. Offline participation as well as online participation prior to the first survey in 2019 were measured using seven items each (Table 1). The measure of online participation was reliable, but the reliability of offline participation was rather low. This was likely because many of the offline activities were rare prior to t1; in fact, the scale of intended participation in the same offline activities was highly reliable (α = 0.80). Therefore, the offline measure was retained as a binary variable indicating whether or not a student had participated in at least one of the offline activities prior to t1. In 2020, offline participation was measured by means of seven items and online participation was measured by means of five items, excluding offline and online discussions (Table 2).

Covariates in these models included students’ gender, their age (in years), and university affiliation. Behavioral norms are considered important precursors of actual behavior (Dalton, 2008; van Deth, 2007), and thus the perceived importance of participation in peaceful protests against laws believed to be unjust was included (one item sourced from Schulz et al., 2018; t1). Students’ sense of the effectiveness of joint action (online or as a group of young people) to bring about social change and influence government decisions (mean of four items adapted from Jugert et al., 2013; t1), as well as their sympathy for the social movement (one item based on Allen et al., 2017; t2) were included, because collective efficacy and identification with the movement are considered relevant predictors in the context of social movement theory (van Stekelenburg and Klandermans, 2013). In addition, the analysis accounted for students’ satisfaction with the performance of Hong Kong’s government (one item measured at t2) as an indicator of political (dis)satisfaction, another common predictor of collective action (van Stekelenburg and Klandermans, 2013).1

Results

Forms of Participation

Table 1 shows that electoral participation was the most common reported and anticipated activity among the surveyed students in 2019. However, only few had interacted or intended to interact with public officials and/or political groups. More common were non-institutionalized activities geared toward the local community, as well as online forms of participation. Two thirds of all students (66%) reported participation in one of the online political activities, while only about half (53%) had participated in one of the offline activities (not including voting). Common offline activities were signing a petition, donating money, or solving a problem in the local community. Only 6% had previously participated in collective protest activities, but a quarter of the students planned to get involved in collective protests in the year ahead. Regarding the online activities, over a third of the students reported sending or forwarding messages, signing online petitions, or posting comments on public issues online. Starting or joining political groups on social media or contributing to hashtag campaigns were less common, but still more students engaged in these activities than in (nonelectoral) institutionalized or protest political participation. Noteworthily, students who had participated in an offline activity also reported more online participation (r = 0.39; p < 0.001); this correlation was stronger for intended political participation (r = 0.68; p < 0.001).

In June 2020, 91% of the local students who participated in the second survey and reported being eligible to vote in elections in Hong Kong said that they had registered to vote.2 Eighty-five percent of the eligible students had voted in the elections to the District Councils in November 2019. The election was a defeat of the pro-establishment camp, although the pro-democracy camp won several districts by only a small majority (Cheung, 2019). Table 2 summarizes students’ self-reported participation.

The table shows that students were quite active in offline and online activities supporting the social movement. More than three out of four students had participated in at least one of the online (79%) or offline (76%) political activities to support the movement (not including voting and discussions). Many students discussed their political opinion. Boycotting products or services and mass demonstrations were other common activities in which students engaged. Students also signed online petitions and expressed their opinion by sending/forwarding messages or posting comments on the Internet.

Some rarely considered forms of political activity are noteworthy. For example, some students created materials such as videos or artwork related to the movement, others translated articles for foreign news to help raise international awareness of the protests in Hong Kong. A few students also supported the movement as a “civilian reporter” (2%) or first aider on protest sites (2%). As in the first survey, students who had participated in more online activities also reported more offline participation (r = 0.75; p < 0.001).

A quarter of the surveyed students (26%) also indicated that they participated in unauthorized activities to support the movement, while active support for the establishment was rare (6%). Many of the students who were surveyed in 2020 said that they “probably” or “certainly” will support the movement in the future (79%), and 30% were willing to participate in confrontational protest activities. Also, most eligible students (91%) planned to cast their vote in the upcoming elections to the Legislative Council.3

Cross-Lagged Associations Between Offline and Online Participation

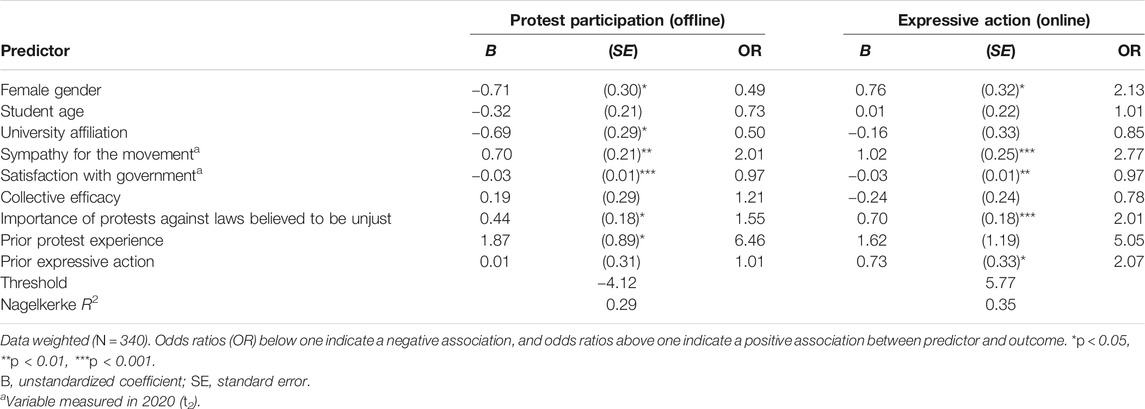

We now turn our attention to the question whether online and offline participation were associated with each other in longitudinal perspective. Table 3 summarizes the results of logistic regression analyses where participation in collective protests (mass demonstrations and/or university-based protests) and in the two previously mentioned online expressive activities (sending/forwarding political messages, posting/replying political comments online) to support the social movement (t2) were regressed on participation prior to the first survey (t1), accounting for covariates.

The results in Table 3 show that male students and students who sympathized with the movement more likely reported participation in collective protests. Students were also more likely to report protest participation if they were less satisfied with the performance of Hong Kong’s government and when they felt that citizens should protest against laws seen as unjust. Importantly, chances to participate in collective protest activities to support the social movement were significantly higher if students had previous collective protest experience. However, previous expressive online action was non-significantly associated with collective protesting in the cross-lagged analysis when covariates were included.

On the other hand, students were more likely to forward political messages and/or post political comments online if they had previous experiences in expressing themselves by means of these activities. In addition, female students more commonly reported these two online expressive activities to support the social movement. The chances of using these forms of online expression were also higher among students who sympathized with the movement, those less satisfied with the Hong Kong government, and students believing in the importance to protest against laws perceived as unjust.

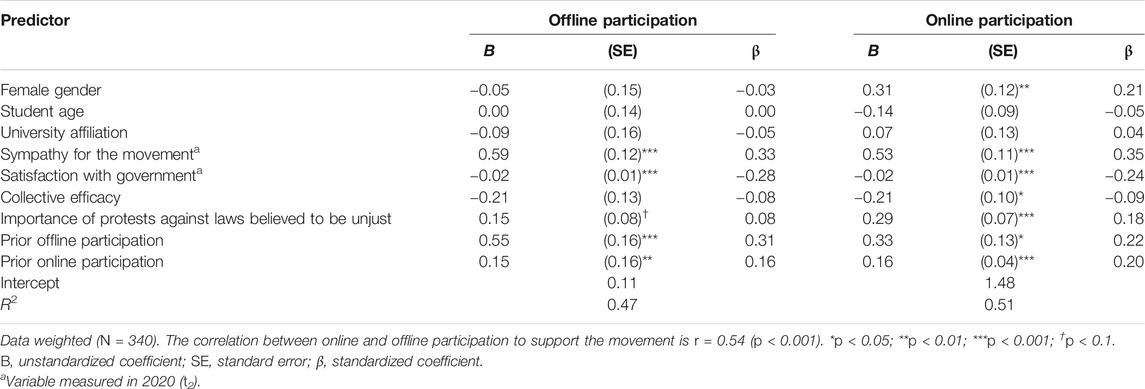

Table 4 summarizes the results of a multivariate linear regression model in which students’ participation in (up to seven) offline activities and in (up to five) online activities to support the movement (t2) were regressed on participation in a broader range of seven offline and seven online activities prior to t1, and the covariates. This analysis draws a more comprehensive picture of the longitudinal associations between offline and online participation. Specifically, female students were more active online compared to male students, but there was no gender difference regarding activities conducted offline. Similarly, students’ who reported higher levels of collective efficacy and those who believed that good citizens should protest against laws perceived as unjust were more active online (the effect of the protest norm was marginally significant for offline activities). Students were also more involved in offline and online activities the more they sympathized with the movement and the less satisfied they were with the government in Hong Kong. Finally, students reported more participation in online activities to support the movement if they had previous participatory experiences in offline or online modes (both effects were non-significantly different from each other, p > 0.1). Although participatory experiences in each mode were also significant and positive predictors of offline activities to support the social movement, offline participation in the movement was more strongly associated with prior offline political experiences than with online political participation prior to t1 (p < 0.05).

Discussion

The results challenge claims according to which young people are apathetic; rather, youth prefer non-institutionalized or “latent” forms of political participation (Amnå and Ekman, 2014; Fu et al., 2016). Besides electoral participation, many of the young adults surveyed here participated in activities geared toward the local community and engaged in a range of online activities.

The fact that many more students had participated in offline political activities to support the anti-extradition bill social movement than prior to the movement, and the significant positive effect of the belief that good citizens should protest against laws believed to be unjust, tentatively indicate that many students became politicized in the context of the anti-extradition bill movement. They were prepared to participate in politics and got involved as they felt that “something went wrong” in the public domain, which indicates the importance of citizenship norms (Dalton, 2008; van Deth, 2007). Many young people also discussed political issues and used creative and/or expressive forms of participation, such as creating videos or posters, forwarding messages or posting comments online. Some students even chose to translate news or to report from protest sites to win over international audiences and to put pressure on the government in Hong Kong. Many students also boycotted products or services (e.g., gastronomical services), they took to the streets to attend peaceful or violent protests, and signed petitions. Donations to support the movement included money and goods such as meal vouchers or helmets.

In line with social movement theory, the results indicate that youth’s participation likely reflects (at least in part) expressive dissatisfaction with the government (van Stekelenburg and Klandermans, 2013). Yet, although young adults in Hong Kong perceive electoral politics as ineffective (Lam, 2018), they were the most active age group in recent elections (Chung, 2020). Their electoral choices probably reflect protest votes, which are influenced by views on specific issues, dissatisfaction, and aspects of political communication rather than political ideology (Birch and Dennison, 2019)—conditions that were present in the Hong Kong context. Moreover, students’ participation in collective protests and their usage of digital media to support the social movement may have increased their willingness to cast a protest vote (Mosca and Quaranta, 2017). Although the present study did not ask for whom they voted, the fact that many students were unhappy with the government’s performance and actively supported the social movement and not the establishment supports these speculations.

In addition to the various forms of participation used by young adults in Hong Kong, the analysis showed that participation in offline and online modes is positively associated with each other. Students who reported participation in one mode were significantly more likely to report activities in the other mode. What is more, cross-lagged analyses suggest that experiences in offline political activities increase the chances of participation through online means. Although expressive action through sending political messages and/or posting political comments on the Internet was not a significant predictor of participation in collective protests, the analysis of a broader set of offline and online activities provides some support for both reinforcement and mobilization: participation in one mode increased the chances of participation in the other mode, thus potentially widening gaps in participation while also creating a path from online activities to offline political participation (Norris, 2001). Note that some scholars have argued that social media were a key element for the communication among protesters and to coordinate protest activities in Hong Kong’s anti-extradition bill social movement (Lee et al., 2019; Ting, 2020). However, the current analysis cannot clarify whether the boundaries between private and political blurred on the Internet and to what extent otherwise politically uninterested and unreachable individuals were mobilized (Bennett, 2008; Zuckerman, 2015). However, it is noteworthy that female students were particularly likely to engage in online forms of activism, as they otherwise seem less willing to participate in politics (Liu, 2020; Schulz et al., 2018). Thus, online activism may help reduce gender inequalities in political participation.

Importantly, the data indicate that the direction is not exclusively from online participation to offline political action, as often discussed (Chan et al., 2017; Skoric et al., 2016). More research is required to examine potential differences in the mechanisms leading to political participation in different modes, and to understand how and when participation in each mode predicts radicalization. Discussion networks and their heterogeneity may be relevant mediators or moderators in this process (Zhu et al., 2020). The findings reported here may have relevance for flawed and hybrid democratic systems, but research in other social and political contexts is warranted.

There are also downsides of the use of digital media for political expression. Although social media can accelerate a social movement, their massive use sets a high benchmark that can lead to less satisfying experiences in the future (Chu and Yeo, 2020). Once people have formed their opinion and “picked a side,” they more likely will selectively expose themselves to channels and information that align with their own views. “[T]he ease to form communities of like-minded peers can result in echo chambers that lack critical discussion, divergent opinion, and political discourse” (Panke and Stephens, 2018; p. 248). Thus, expressing one’s own view on the Internet may become less effective as the potential of having debates to convince those holding different views diminishes, making collective action all the more relevant (Chu and Yeo, 2020). Moreover, echo chambers can also lead to political polarization and radicalization (Law et al., 2018).

In the digital age, it is also important that citizens develop information literacy, deliberation skills, and respect ground rules for communication; encouragement to connect with people who are unlike oneself might also foster understanding of others, exposure to different views, and the capacity to see issues from different perspectives (Law et al., 2018; Panke and Stephens, 2018). For example, recognizing that news pieces written by “civilian reporters,” who were volunteers promoting the movement, may not be as credible as articles published by trained journalists adhering to the standards of quality journalism is an important skill. Unfortunately, research in the U.S. suggests that youth have difficulties evaluating online information and their sources (McGrew et al., 2018). Though recent research indicates that (offline) political participation might not increase citizens’ levels of political knowledge (Grobshäuser and Weißeno, 2020; Reichert and Print, 2019), whether that is also true for online forms of political participation and how participatory experiences more broadly relate to information literacy remains an open question.

Overall, the data indicate that prior participatory experiences may contribute to a “habit” of participation, with potential reinforcement across modes. However, experiences of unsuccessful participation that do not lead to the expected outcomes could also foster feelings of fatigue and helplessness leading to political disaffection and apathy (Jackson et al., 2017; Reichert, 2017). Further longitudinal data are necessary to understand how young adults’ participation in the social movement and the new security legislation in Hong Kong may affect their willingness to influence political decisions in the future. Research should also consider the role of social and political values in explaining youth political participation in flawed democracies and in authoritarian regimes, as well as possible outcomes of participatory experiences.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available. The datasets generated for this study will be made publicly available through the Policy Innovation and Coordination Office in accordance with its guidelines and the requirements specified by the Office of the Privacy Commissioner for Personal Data 5 years after conclusion of the research project. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to reichert@hku.hk.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee, The University of Hong Kong. Written informed consent from the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author Contributions

FR conceptualized the research, conducted the analysis, and drafted and reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

This research project is funded by the Public Policy Research Funding Scheme (Special Round) from the Policy Innovation and Co-ordination Office of The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (Project Number: SR2020A8.006, Principal Investigator: FR), and by the Theme-based Research Scheme from the Research Grants Council of The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (Project Number: T44-707/16-N, Principal Investigator: Nancy Law).

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the project team members who helped with funding acquisition, data collection, and data curation.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2020.608203/full#supplementary-material.

Footnotes

1Note that the results for prior offline and online participation in the regression models remained the same when the two predictors measured at t2 were excluded, though then protest participation prior to t1 became a marginally significant, positive predictor of forwarding messages and/or posting comments online in Table 3 (p < 0.1).

2The question was unspecific as to when they registered (students may have registered at any time before or after t1).

3The election—originally scheduled for September 2020—was postponed for a year after the data had been collected.

References

Allen, S., McCright, A. M., and Dietz, T. (2017). A social movement identity instrument for integrating survey methods into social movements research. SAGE Open. 7, 1–10. doi:10.1177/2158244017708819

Amnå, E., and Ekman, J. (2014). Standby citizens. Diverse faces of political passivity. Eur. Pol. Sci. Rev. 6, 261–281. doi:10.1017/S175577391300009X

Bennett, W. L. (2008). “Changing citizenship in the digital age,” in In civic life online: learning how digital media can engage youth. Editor W. L. Bennett (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press), 1–24.

Bennett, W. L., and Segerberg, A. (2013). The logic of connective action: digital media and the personalization of contentious politics. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Birch, S., and Dennison, J. (2019). How protest voters choose. Party Polit. 25, 110–125. doi:10.1177/1354068817698857

Boulianne, S. (2020). Twenty years of digital media effects on civic and political participation. Commun. Res. 47, 947–966. doi:10.1177/0093650218808186

Centre for Youth Studies (2017). Research Report. Youth political participation and social media use in Hong Kong. The Chinese University of Hong Kong. Available at: https://www.cuhk.edu.hk/hkiaps/cys/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/Research-Report_Youth-Political-Participation-and-Social-Media-Use-in-Hong-Kong.pdf (Accessed September 3, 2020).

Chan, M., Chen, H.-T., and Lee, F. L. F. (2017). Examining the roles of mobile and social media in political participation, A cross-national analysis of three Asian societies using a communication mediation approach. New Media Soc. 19, 2003–2021. doi:10.1177/1461444816653190

Cheung, G. (2019). Hong Kong elections. Why victorious opposition camp has to keep wary eye on swing voters—and has no room for complacency despite massive haul of seats. South China Morning Post. Available at: https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/politics/article/3039314/hong-kong-elections-why-victorious-opposition-camp-has-keep. (Accessed November 26, 2019).

Chu, T. H., and Yeo, T. E. D. (2020). Rethinking mediated political engagement. Social media ambivalence and disconnective practices of politically active youths in Hong Kong. Chin. J. Commun. 13, 148–164. doi:10.1080/17544750.2019.1634606

Chung, K. (2020). Hong Kong district council election data reveals turnout now highest among young people, driven to the ballot box by anti-government protests. South China Morning Post. Available at: https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/politics/article/3078401/hong-kong-district-council-election-data-reveals-turnout (Accessed April 4, 2020).

Dalton, R. J. (2008). Citizenship norms and the expansion of political participation. Polit. Stud. 56, 76–98. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9248.2007.00718.x

Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) (2020). Democracy index 2019: a year of democratic setbacks and popular protest. Available at: https://www.eiu.com/public/topical_report.aspx?campaignid=democracyindex2019 (Accessed September 19, 2020).

Ekström, M., and Östman, J. (2015). Information, interaction, and creative production. The effects of three forms of internet use on youth democratic engagement. Commun. Res. 42, 796–818. doi:10.1177/0093650213476295

Fu, K., Wong, P. W. C., Law, Y. W., and Yip, P. S. F. (2016). Building a typology of young people’s conventional and online political participation. A randomized mobile phone survey in Hong Kong, China. J. Inf. Technol. Polit. 13, 126–141. doi:10.1080/19331681.2016.1158138

Grobshäuser, N., and Weißeno, G. (2020). Does political participation in adolescence promote knowledge acquisition and active citizenship? Educ. Citizenship Soc. doi:10.1177/1746197919900153

Jackson, L., Kapai, P., Wang, S., and Leung, C. Y. (2017). “Youth civic engagement in Hong Kong: a glimpse into two systems under one China,” in Youth civic engagement in a globalized world: citizenship education in comparative perspective. Editor C. Broom (New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan), 59–86.

Jugert, P., Eckstein, K., Noack, P., Kuhn, A., and Benbow, A. (2013). Offline and online civic engagement among adolescents and young adults from three ethnic groups. J. Youth Adolesc. 42, 123–135. doi:10.1007/s10964-012-9805-4

Ku, A. S. (2020). New forms of youth activism—Hong Kong’s Anti-Extradition Bill movement in the local-national-global nexus. Space Polity. 24, 111–117. doi:10.1080/13562576.2020.1732201

Lam, W.-M. (2018). “Changing political activism: before and after the umbrella movement,” in Hong Kong 20 years after the handover: emerging social and institutional fractures after 1997. Editors B. C. H. Fong, and T.-L. Lui (Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan), 73–102.

Lam-Knott, S. (2019). Responding to Hong Kong’s political crisis: moralist activism amongst youth. Inter Asia Cult. Stud. 20, 377–396. doi:10.1080/14649373.2019.1649016

Law, N., Chow, S.-L., and Fu, K. (2018). “Digital citizenship and social media: a curriculum perspective,” in Second handbook of information technology in primary and secondary education. Editors J. Voogt, G. Knezek, R. Christensen, and K.-W. Lai (New York, NY: Springer), 53–68.

Lee, F. (2020). Solidarity in the anti-extradition bill movement in Hong Kong. Crit. Asian Stud. 52, 18–32. doi:10.1080/14672715.2020.1700629

Lee, F. L. F., Yuen, S., Tang, G., and Cheng, E. W. (2019). Hong Kong’s summer of uprising. From anti-extradition to anti-authoritarian protests. China Rev. 19, 1–32. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26838911

Lee, N.-J., Shah, D. V., and McLeod, J. M. (2013). Processes of political socialization. A communication mediation approach to youth civic engagement. Commun. Res. 40, 669–697. doi:10.1177/0093650212436712

Liu, S.-J. S. (2020). Gender gaps in political participation in Asia. Int. Polit. Sci. Rev. 36 (5), 526–544. doi:10.1177/0192512120935517

Low, Y. T. A., Busiol, D., and Lee, T. (2016). A review of research on civic and political engagement among Hong Kong youth. Int. J. Child Adolesc. Health. 9, 423–432. https://www.questia.com/library/journal/1P3-4311940101/a-review-of-research-on-phone-addiction-amongst-children

McGrew, S., Breakstone, J., Ortega, T., Smith, M., and Wineburg, S. (2018). Can students evaluate online sources? Learning from assessments of civic online reasoning. Theory. Res. Soc. Educ. 46, 165–193. doi:10.1080/00933104.2017.1416320

Mosca, L., and Quaranta, M. (2017). Voting for movement parties in Southern Europe: the role of protest and digital information. South. Eur. Soc. Polit. 22, 427–446. doi:10.1080/13608746.2017.1411980

Muthén, L. K., and Muthén, B. O. (1998–2017). Mplus user’s guide. 8th Edn, Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén.

Ng, H. Y. (2016). What drives young people into opposition parties under hybrid regimes? A comparison of Hong Kong and Singapore. Asian Polit. Policy. 8, 436–455. doi:10.1111/aspp.12261

Norris, P. (2001). Digital divide: civic engagement, information poverty, and the internet worldwide. Cambridge, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Panke, S., and Stephens, J. (2018). Beyond the echo chamber. Pedagogical tools for civic engagement discourse and reflection. J. Edu. Technol. Soc. 21, 248–263. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1OeFrw8NXyGdZXqZObtXSanRi6P6ltvaH/view

Purbrick, M. (2019). A report of the 2019 Hong Kong protests. Asian Aff. 50, 465–487. doi:10.1080/03068374.2019.1672397

Reichert, F. (2017). Conditions and constraints of political participation among Turkish students in Germany. Cogent Psychol. 4, 1351675. doi:10.1080/23311908.2017.1351675

Reichert, F. (2020). “Media use and youth civic engagement,” in The international encyclopedia of media psychology. Editors J. van den Bulck, D. R. Ewoldsen, M.-L. Mares, and E. Scharrer (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons Inc.), 1–8.

Reichert, F., and Print, M. (2017). Mediated and moderated effects of political communication on civic participation. Inf. Commun. Soc. 20, 1162–1184. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2016.1218524

Reichert, F., and Print, M. (2019). Participatory practices and political knowledge. How motivational inequality moderates the effects of formal participation on knowledge. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 22, 1085–1108. doi:10.1007/s11218-019-09514-5

Schulz, W., Ainley, J., Fraillon, J., Losito, B., Agrusti, G., and Friedman, T. (2018). Becoming citizens in a changing world: IEA international civic and citizenship education study 2016 international report. Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

Skoric, M. M., Zhu, Q., and Pang, N. (2016). Social media, political expression, and participation in Confucian Asia. Chin. J. Commun. 9, 331–347. doi:10.1080/17544750.2016.1143378

Ting, T. (2020). From ‘be water’ to ‘be fire’: nascent smart mob and networked protests in Hong Kong. Soc. Mov. Stud. 19, 362–368. doi:10.1080/14742837.2020.1727736

van Deth, J. W. (2007). “Norms of citizenship,” in In Oxford handbook of political behavior. Editors R. J. Dalton, and H.-D. Klingemann (Oxford, NY: Oxford University Press), 402–417.

van Stekelenburg, J., and Klandermans, B. (2013). The social psychology of protest. Curr. Sociol. 61, 886–905. doi:10.1177/0011392113479314

Vromen, A., Xenos, M. A., and Loader, B. (2015). Young people, social media and connective action. From organisational maintenance to everyday political talk. J. Youth Stud. 18, 80–100. doi:10.1080/13676261.2014.933198

Weiss, J. (2020). What is youth political participation? Literature review on youth political participation and political attitudes. Front. Polit. Sci. 2, 1–13. doi:10.3389/fpos.2020.00001

Wong, K. T., Zheng, V., and Wan, P. (2017). A dissatisfied generation? An age-period-cohort analysis of the political satisfaction of youth in Hong Kong from 1997 to 2014. Soc. Indicat. Res. 130, 253–276. doi:10.1007/s11205-015-1175-3

Xia, Y. (2016). Contesting citizenship in post-handover Hong Kong. J. Chin. Polit. Sci. 21, 485–500. doi:10.1007/s11366-016-9439-6

Zhu, A. Y. F., Chan, A. L. S., and Chou, K. L. (2020). The pathway toward radical political participation among young people in Hong Kong: a communication mediation approach. East Asia. 37, 45–62. doi:10.1007/s12140-019-09326-6

Keywords: citizenship, civic engagement and participation, Hong Kong, political participation, protest action, social media, social movement, young adult

Citation: Reichert F (2021) Collective Protest and Expressive Action Among University Students in Hong Kong: Associations Between Offline and Online Forms of Political Participation. Front. Polit. Sci. 2:608203. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2020.608203

Received: 19 September 2020; Accepted: 14 December 2020;

Published: 20 January 2021.

Edited by:

Isabel Menezes, University of Porto, PortugalReviewed by:

Jasmine Lorenzini, Université de Genève, SwitzerlandMaria Fernandes-Jesus, University of Sussex, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2021 Reichert. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Frank Reichert, cmVpY2hlcnRAaGt1Lmhr

Frank Reichert

Frank Reichert