94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Polit. Sci., 08 January 2021

Sec. Elections and Representation

Volume 2 - 2020 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2020.591983

This article is part of the Research TopicImproving, Bypassing or Overcoming Representation?View all 11 articles

Dimitri Courant1,2*

Dimitri Courant1,2*Among democratic innovations, deliberative mini-publics, that is panels of randomly selected citizens tasked to make recommendations about public policies, have been increasingly used. In this regard, Ireland stands out as a truly unique case because, on the one hand, it held four consecutive randomly selected citizens' assemblies, and on the other hand, some of those processes produced major political outcomes through three successful referendums; no other country shows such as record. This led many actors to claim that the “Irish model” was replicable in other countries and that it should lead to political “success.” But is this true? Relying on a qualitative empirical case-study, this article analyses different aspects to answer this question: First, the international context in which the Irish deliberative process took place; second, the differences between the various Irish citizens' assemblies; third, their limitations and issues linked to a contrasted institutionalization; and finally, what “institutional model” emerges from Ireland and whether it can be transferred elsewhere.

In recent years, various countries witnessed democratic innovations to include citizens in political decision-making and improve representation (Saward, 2000; Smith, 2009; Elstub and Escobar, 2019). Among those experimentations, deliberative mini-publics (DMPs) had the most impacts (Reuchamps and Suiter, 2016). Mini-publics are stratified randomly-selected panels bringing ordinary citizens together to deliberate on public policy issues (Grönlund et al., 2014). Various types have been implemented all over the world: citizens' juries, deliberative polls, or more recently, citizens' assemblies (CAs) which are increasingly being used worldwide, with varying uptakes (Courant and Sintomer, 2019; Gastil and Wright, 2019; Harris, 2019).

Ireland stands out as a truly unique case because, on the one hand, it held four consecutive randomly selected citizens' assemblies, and on the other hand, some of those processes produced major political outcomes through three successful referendums; no other country shows such a record. Following the deliberations of the Convention on the Constitution (CotC), bringing together 66 randomly selected citizens and 33 politicians, the 2015 referendum on marriage equality changed the Constitution and legalized same-sex marriage; following the recommendations of the Irish Citizens' Assembly (ICA), involving 99 citizens, the 2018 referendum produced another constitutional change legalizing abortion.

The real-life experimentation in Ireland seems to have provided some empirical support to the many theoretical propositions and projects for an institutionalized deliberative democracy mainly relying on randomly selected mini-publics (Leib, 2004; O'Leary, 2006; Barnett and Carty, 2008; Callenbach and Phillips, 2008; Sutherland, 2008; Buchstein, 2010; MacKenzie, 2016; Gastil and Wright, 2019). Mentioning the Irish case, Dryzek et al. (2019, 1145) note: “These processes reinvigorated the political landscape after the political disasters that the global financial crisis unleashed on Ireland,” Those political uptakes were viewed as a “success” by many (Honohan, 2014; Renwick, 2015, 2017; Suteu, 2015; Flinders et al., 2016; Van Reybrouck, 2016), and also led several actors to claim that the “Irish model” was replicable in other countries and that it should lead to political “improvements”1. This influenced, among others, the Citizen Conventions for Climate in France and the Climate Assembly UK in the United Kingdom, as well as activists' demands, such as Extinction Rebellion. Moreover, the citizens' assemblies of Ireland are gradually becoming a reference, or even the main reference, for deliberative democracy scholars (Reuchamps and Suiter, 2016; Setälä, 2017; Dryzek et al., 2019; Gastil and Wright, 2019; Harris, 2019). Are we really facing a paradigm shift that could improve political representation globally? This optimistic claim raises interrogations and require empirical investigation. Does the “Irish model” actually exist? If so can the Irish model be replicated? And should the Irish model be replicated, that is to say, did it perform as well as advocates say? An empirical analysis of the Irish case is necessary to understand what made this deliberative process possible in the first place, in terms of international, structural, contextual, and local factors. In order to properly analyze the phenomenon, four areas must be investigated.

First, in which international context did the Irish deliberative process take place? It is crucial to locate Ireland's innovations within the global trend of deliberative mini-public and to grasp the transfer and inspiration that the Irish case took from other mini-publics worldwide. Moreover, citizens' assemblies already took place in other countries, so what could possibly make Ireland “better” than its foreign predecessors?

Second, is there such thing as an “Irish model” given the differences between its various mini-publics? How were those different deliberative mini-publics created? What is the contrasted dynamic of this institutionalization process, from informal margins to official center? What processes, actors, and contexts turn democratic innovations into new democratic institutions? This article studies the “incomplete” institutionalization process of deliberative democracy in Ireland by comparing the successive assemblies, their ruptures and continuities, and their articulation. The most notable change requiring explanation is the presence then absence of politicians between assemblies. It is important to study the “deliberative system” (Parkinson and Mansbridge, 2012) within which the Irish mini-publics fitted.

Third, is the Irish experience an “absolute success” or are there limitations worth investigating, and if so, which ones? How did those citizens' assemblies function and dysfunction? If those deliberative innovations provided some major uptakes and were widely celebrated, careful examination reveals several shortcomings and problems which should be taken into account as most applies to mini-publics worldwide. Conversely, many elements in the Irish assemblies offer insights of efficient practices and subtle design. For political representation to be truly “improved” it is necessary to critically assess democratic innovation real-life cases through informed and empirically grounded research.

Finally, is Ireland actually crafting new democratic institutions transferable to other countries, or is it merely a local exception? What “institutional model” could emerge from the Irish case? Given the empirical analysis, careful hypothesis and theories can be made about the impact of Ireland beyond its borders.

As we will see, supporters of the “Irish model” claim it is a “success” often without good knowledge of the cases and while remaining vague as to the criteria for assessing the said “success.” They tend to focus on the mere fact that Irish mini-publics saw some of their recommendations approved by referendums, and that those recommendations were judged “good” or “progressive” by the commentators. In answering the four research areas listed above, I refer to a theoretical framework commonly used in the evaluation of mini-publics distinguishing between input, throughput and output legitimacy (Bekkers and Edwards, 2007; Papadopoulos and Warin, 2007; Caluwaerts and Reuchamps, 2015; Reuchamps and Suiter, 2016). Input legitimacy refers to the quality of representation, the openness of the agenda and the level of information. Throughput legitimacy includes the quality of participation, the quality of decision making, and the contextual independence. Output legitimacy encompasses public endorsement, the weight of the results, and responsiveness and accountability. This framework integrates the dimensions highlighted by others scholars, like the analysis of representativeness, citizen control over the process, and decision-making impact (Böker and Elstub, 2015, 133–134), or the distinction between participant selection, communication and decision, and authority and power (Fung, 2006). I also try go beyond mere design features to look at the actual practice in its concrete reality (Geissel and Gherghina, 2016).

The Irish mini-publics have been mentioned a lot, but very few scientists have actually conducted research on them. A core group of a few researchers published the vast majority of articles on those cases. If several very interesting and stimulating scientific papers and books' chapters have been written by those few authors on the Irish cases, most took a quantitative approach (Farrell et al., 2013; Suiter et al., 2016a,b; O'Malley et al., 2020). Moreover, the authors being directly involved in the organization and promotion of several of the Irish CAs, their own role as actors is not analyzed. Most of the time the authors mention their involvement in a footnote rather than opting for reflexivity and making their own actions an object of the study. Their papers, even when more descriptive than quantitative (Farrell et al., 2018), tend to focus on one of the three assemblies rather than all of them and their connections.

Therefore, there is a gap in the literature at two levels. On the one hand, in terms of methodology, qualitative methods have been largely underused. On the other, in terms of position and approach, an exploration of the long and dynamic process between the cases has also received less analysis than other aspects, such as opinion changes or the impact of talking in the assemblies. This paper considers all actors in these process, including the crucial actions of the political scientists, who were interviewed as part of this research. In this regard, this paper adopts some of the features of a process-tracing approach (Bezes et al., 2018; Beach and Pedersen, 2019). Another relative originality of my research is my position, contrary to a fair share of scientists adopting an “involved position,” I am not studying assemblies I actively advocated for or organized, which lends itself to a more “external” point of view. However, because I have conducted a long qualitative fieldwork, I remain “connected” to the case and avoid the “disconnected position” that other researchers adopt as they write on cases they have not empirically studied themselves.2

In order to answer the questions asked above and to offer an original approach, this paper adopts a critical political sociology approach relying on a qualitative case-study based on: a comprehensive fieldwork in Ireland, hundreds of hours of direct ethnographic observation spread over 48 days out of a total of 75 days of fieldwork, but also 44 semi-directives in depth interviews ranging from 1 to 2 h for most and around 30 min for a minority (with randomly selected citizens, politicians, organizers, etc. see Table 1), as well as content analysis of over 300 various sources such as press articles, official documents, reports, video records of debates, and statements. Analysis and coding were conducted using Computer-assisted qualitative data analysis software (CAQDAS) and more specifically NVivo, and mixing deductive codes and inductive ones, following a framework analysis approach (Ritchie et al., 2014; Saldana, 2016). Adopting a qualitative methodological framework is “particularly suited to answer three types of questions (…). How democratic innovations emerge? How is deliberation framed by the organizers and participants of these events? What are the effects of democratic innovations on participants and public policies?” (Talpin, 2019, 487). This design matches the research questions and the diversity of data allowed for a strong triangulation (Richards, 2015).

First, I start by presenting the context within which the Irish case arises. It is crucial to put the Irish citizens' assemblies (ICAs) into context, by highlighting they are the latest chapter of a long trend involving deliberative mini-publics and as a product of international transfers, in order to break the illusion that “all was invented in Ireland”—as several press articles cited before may lead to believe. Secondly, I analyze the institutionalization process of deliberative democracy in Ireland by studying the successive assemblies, their ruptures and continuities, and their articulation. Finally, in light of the empirical insights, I discuss the progress and the limitations of the Irish case, showing that if Ireland went further than its predecessors, it did encounter new challenges and common problems that other mini-publics might face as well.

Due to the importance of the political changes initiated through its democratic innovations, Ireland should be considered a trailblazer but also as the successor to a wider political trend aimed at making democracy more deliberative and inclusive through randomly selected panels of citizens (Saward, 2000; Smith, 2009; Courant and Sintomer, 2019). I distinguish six generations of deliberative mini-publics.3

First, the High Council of the Military Function (HCMF, Conseil Supérieur de la Fonction Militaire) established by the French Parliament in 1969, still active today, brings together 85 randomly selected representatives and deals with all matters related to soldiers' working conditions; it is the first and the most durable mini-public in modern history, as well as the first permanent randomly selected institution in the modern world (Courant, 2019a). Secondly, the Citizens' Juries and Planning Cells, created in the 1970s by Ned Crosby and Peter Dienel, involve ordinary citizens in drafting a report to inform public policy decisions, spread throughout many countries but without strong institutionalization (Crosby and Nethercut, 2005; Hendriks, 2005; Vergne, 2010). Third, the Consensus Conferences on techno-scientific issues were launched in the 1980s by the Danish Board of Technology and spread in various EU countries as well as in Switzerland, where the TA-SWISS was officially established by Parliament to produce impartial evaluations of contested new technologies (Joss and Bellucci, 2002). Fourth, Deliberative Polling was invented by James Fishkin in the 1990s and has been tested around the world since. It aims at showing “considered opinion” contrary to traditional opinion polls that capture only “raw opinions” (Fishkin, 2009; Mansbridge, 2010). Fifth, the Citizens' Initiative Review was set up in Oregon in 2010 to have a panel produce impartial information on upcoming referendums that is sent to the voting population in order to help it cast an informed ballot (Knobloch et al., 2015); since then, the device has spread to Arizona, Colorado, Washington State, Massachusetts, and California. Finally, the new trend of this family of democratic innovations are the Citizens' Assemblies (CAs), launched in Canada in 2004 (Warren and Pearse, 2008) and then replicated with various changes in the Netherlands (Fournier et al., 2011), Australia (Carson et al., 2013), Iceland, Belgium, Ireland (Reuchamps and Suiter, 2016), and the United Kingdom (Flinders et al., 2016; Renwick, 2017; Hughes, 2018). According to Böker and Elstub (2015), deliberative polls tend to have the greatest representativeness but the least impact; citizens juries, planning cells and consensus conferences have moderate representativeness and impact; while CAs tend to have a high representativeness and the greatest impact (see also: Harris, 2019). Very often, the HCMF and the CIR are left out by scholars comparing mini-publics, but those cases display a high level of embeddedness in their respective political system.

Of those generations of mini-public based democratic innovations, the last one is now front of stage and potentially reveals a “constitutional turn for deliberative democracy” (Reuchamps and Suiter, 2016). The first citizens' assembly was established in 2004 in the Canadian province of British Columbia. The government gave to a mini-public of 158 randomly selected citizens and two hand-picked citizen natives the mission to propose a new electoral system for the province that would be submitted to a referendum (Warren and Pearse, 2008). Two years later, a similar process was put in place in the Netherlands and Ontario. However, all of the proposals failed to be implemented. The super-majority threshold of 60% for the referendum was missed by a small margin (58%) in British Columbia and by a substantial one in Ontario (37%), while the Dutch proposal was rejected by the government without being put to a vote (Fournier et al., 2011).

Nevertheless, in Iceland, the deliberative constitutional process obtained a popular victory at the ballot box in 2012. In the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, massive protests led to the resignation of the government and the election of a left-wing and ecologist coalition. A process to revise the constitution was implemented in several phases. First, in November 2009, under the impulse of a civil society movement, a National Assembly composed of 900 randomly selected citizens along with 300 representatives of civil-society associations deliberated for 1 day on the future of the country and the issues to be tackled by a constitutional reform. The government replicated the process under the name National Forum, in which 950 randomly selected citizens deliberated for a day to identify important topics. Elections were then organized, but parties were forbidden to take part in them. Of the 322 candidates, 25 were elected with a 30% turnout to form the Constitutional Assembly (or Council), whose work is widely followed online, giving birth to what some called a “crowdsourced-Constitution”—even if this is contested. The text was submitted to a referendum in 2012 and was supported by a majority of Icelanders. However, the next elections brought right-wing parties back to power, which refused to approve the “citizens' constitution” in Parliament and blocked its implementation (Bergmann, 2016).

In 2009, an NGO, the New Democracy Foundation, organized the Australian Citizens' Parliament, in which 150 randomly selected participants deliberated for 4 days before presenting its proposal to Parliament, but without much effect or implementation (Carson et al., 2013). Finally, in 2011–2012, Belgium witnessed a randomly selected assembly: the G1000, which remained completely citizen-led and extra-institutional. Hence, its political effects remained marginal in terms of concrete reform, even though its media coverage and quality made it a relative success (Jacquet et al., 2016; Caluwaerts and Reuchamps, 2018).

A useful distinction to be made is the one between state-supported citizens' assemblies and civil-society-led citizens' assemblies. The former, comprising the Canadian and Netherlandish cases, are characterized by an official mandate, important funding, and consequent time for deliberation. The latter, which include the Australian and Belgian cases, do not have institutional support, rely on crowdfunding and donations, and do not allow for long deliberation. In the Icelandic and Irish cases, there is a dynamic process, initiated by civil-society led CAs which pushes the elected representatives to implement state-supported CAs.

Studying planning cells and citizens' juries, Vergne (2010, 90) distinguishes three modes of diffusion for democratic innovations: transposition, in which the original model is directly imported without any changes; transfer, an academic collaboration that results in concrete implementation through which the original model is modified; and influence, when local actors learn the concept from a third party and only take inspiration from it for their own projects. The cases of the Netherlands and Ontario are somewhat similar to a transposition of the British Columbia model. The Irish process, however, draws from all those previous citizens' assemblies in various ways, oscillating between transfer and influence.

The main difference between most mini-publics worldwide, including other CAs, and the Irish cases it that the latter stand out in terms of policy output. In 2019, new CAs have been established, on the issue of climate change, like in the UK or in France (Courant, 2020a). Moreover, in terms of institutional linkage, Belgium has recently witnessed more advanced quasi-institutionalized forms of citizen deliberation with a permanent Citizen Council in the German-speaking Community and permanent mixed parliamentary commission in the Brussels-Capital Region. To date their output legitimacy, however, does not equal that of the Irish experiences.

In the follow up to the democratic innovations described above, the Republic of Ireland was the setting for major political innovations. This transfer was due in part to a worldwide academic network of political scientists. Already in 2005 and 2007, reports from the Democracy Commission and the Irish Democratic Audit, respectively, were produced by the think tank TASC and called for political reform. The Democracy Commission report called for deliberative and participatory approaches to governance, and mentions deliberative panels (Harris, 2005; Coakley, 2010), but with no concrete uptakes. Then, as the country was facing the 2008 financial crisis, a group of researchers, intellectuals and activists debated the necessity of a constitutional reform, especially on the blog politicalreform.ie linked to the Political Studies Association of Ireland. However, and to the best of my knowledge, the first record of a mention of a public advice to use a citizens' assembly in Ireland is the audition of Professor Kenneth Benoit at the parliamentary Joint Committee on the Constitution, on Wednesday 9th December 2009: “In British Columbia a citizens' electoral commission was appointed. This system would, I believe, be the most workable in the Irish case” (Oireachtas, 2009). At the time the CA is only considered for the task of electoral reform, and the Joint Committee is very receptive from the start, eventually making it one of its main recommendation in its final report in July 2010 (Joint Committee on the Constitution, 2010):

“In order to de-politicize any reform process, [the Committee] proposes the establishment of a Citizens' Assembly to examine the performance of PR-STV in Ireland, and if it deems that reforms are necessary, to propose changes (…). It is the opinion of the Committee that the establishment of such an Assembly would facilitate greater popular engagement with the democratic institutions as well as enhancing the legitimacy of any proposed reform.”

In the month following Benoit's presentation, political parties started incorporating his suggestion in their promises, starting with Fine Gael in March 2010 (Farrell, 2010a), then Labor (Farrell, 2010b). Part of the political science community was continuing to push for a CA on electoral reform to become reality, especially the editors of the politicalreform.ie blog who also published an opinion piece in The Irish Times in November 2010 (Byrne et al., 2010). Professor Kenneth Carty, researcher on the Canadian' CAs, gave a presentation on the British Columbia CA, at Trinity College Dublin, the month before. Moreover, the same group of Irish academics developed a “reform score card” in advance of the Irish general election—a CA was mentioned on it (Byrne et al., 2011; Suiter, 2011). As one of its initiators explained:

“the original idea was that we would do a framework to focus on what we thought were the five key areas of political reform. We circulated that to all of the political parties to say that we are going to be ranking your manifestos, you're going to be compared to each other on the basis of these five key areas and we are going to be making it very public” (Connolly, 2011).

After some back tracking and hesitation from political leaders (Collins, 2010; Farrell, 2010c), the 2011 general election definitely opened a “window of opportunity” (Kingdon, 1995) for the CA to gain the attention of political parties, which almost all of whom included a citizen-led constitutional reform in their campaign promises, but with no specification or detail (Carney and Harris, 2011; Wall, 2011). Two of them, Fine Gael (center-right) and Labor (center-left), formed a coalition government, which had pledged to set a CA, after the once dominant Fianna Fáil lost its majority in what was called an “electoral earthquake” (Gallagher and Marsh, 2011; Suiter et al., 2016a). However, no progress was made on this point and there was fear that the design of the CA would be weak and poorly executed. As an Irish analyst noted: “The programme for government did not define what it meant by a constitutional convention, did not detail its likely composition and was silent on what would happen to any recommendations” (Whelan, 2012).

Meanwhile, the group of researchers calling for political reform contacted intellectuals and activists, founded the “We the Citizens” movement, and launched a randomly selected informal assembly in 2011—a so-called “pilot”—to show to the political class and, more broadly, to the country that the direct implication of “ordinary citizens” could be beneficial to change the constitution. One of the key actors of this process, Professor David Farrell, had been invited to give evidence by the Canadian and Dutch citizens' assemblies as an expert in electoral systems, and he was impressed by those deliberative innovations.

This civil-society movement was contacted by the Atlantic Philanthropies, an American foundation aiming to sponsor various initiatives empowering citizens. Benefiting from this financial support, “We the Citizens” held seven participatory forums based on the world café model in Ireland's major cities. Farrell explains: “We were booking conference rooms in hotels and announcing the events in the press and local radio saying: ‘if you want to discuss the future of the country, you are welcome, we will offer you tea and snacks.’”4 The goal was, as with the G1000 and the first two steps of the Icelandic process, to spring up ideas and set the agenda in a bottom-up dynamic way to foster input legitimacy, in other words, to listen to what “ordinary people” wished for the future of Ireland.

Those seven participatory meetings in various cities allowed ‘We the Citizens’ to spot recurring topics and to launch its Pilot Citizens' Assembly in May–June 2011 (Farrell et al., 2013; Suiter et al., 2016b; O'Malley et al., 2020). The polling company Ipsos MRBI constituted a representative sample of which 100 individuals actually were gathered for one weekend in Dublin to deliberate on three issues:

1. the role of members of Parliament (connection with the constituency, electoral system, size of Parliament);

2. the identity of politicians (women, mandate limit, unelected ministers);

3. and the arbitration between tax increases or budget cuts in a time of economic crisis.

In terms of output, the pilot assembly gave “We the Citizens” the opportunity to draft a report pleading for a constitutional citizens' assembly to reform the Irish political system and more crucially to outline a process of how to do so with rigorous procedures. This report, which empirically narrates the deliberative process (We the Citizens, 2011), was used in lobbying various politicians, civil servants, and civil society representatives. This had the effect to prevent the project of State-sponsored CA to fall in oblivion and to set a high deliberative standard for its proceedings. The political scientists from “We The Citizens,” David Farrell, Jane Suiter, Eoin O'Malley, were joined by fellow political scientist Clodagh Harris and a law scholar Lia O'Hegarty, on the Academic and Legal Research Group for the Convention on the Constitution.

We can distinguish a pattern here. A democratic innovation gaining institutional support is often the product of organized democratic activists with high social and symbolic capital often among which political scientists who push the proposal, which is sometimes later accepted by a newly elected government. This was the case in the Netherlands, where the action of the D66 party was crucial (Fournier et al., 2011); in Australia with the New Democracy Foundation (Carson et al., 2013); in Iceland with the input of the Anthills and the access to power of green-left coalition (Bergmann, 2016); and in Oregon, which benefitted from the involvement of Ned Crosby, John Gastil and Healthy Democracy Oregon (Knobloch et al., 2015). To a lesser extent, in British Columbia, activists such as Nick Loenen also pushed for a randomly selected assembly, and, more crucially, the CA on electoral reform was supported by a newly elected party (Lang, 2010, 117). This illustrates a global tendency of sortition activism, in which militants defend sortition (i.e., random selection) in their discourses and sometimes implement it in their practices, as is the case in France, Belgium, the United Kingdom, Australia, and Mexico (Courant, 2018a, 2020b). Interestingly, in the Irish case, it is not mainly deliberative democracy scholars who pushed for a CA, but scholars mostly coming from electoral studies, who had heard about the Canadian and Dutch CAs because those were dealing with electoral reform.

The “electoral earthquake” putting an end to the long-dominant party Fianna Fáil (center-right) and the winning Fine Gael/Labor coalition (Gallagher and Marsh, 2011) allowed for a negotiation around a constitutional convention between various academics, activists, and politicians. Indeed, the two wining parties disagreed on the composition of this assembly, Labor wanted an equal mix of politicians, citizens, and experts, while “We the Citizens” advocated for 100% randomly selected citizens. Eventually, a compromise was reached: the Convention on the Constitution (CotC) was composed of 66 randomly selected citizens and 33 politicians from various political parties represented proportionally to their strength in Parliament.5 The 33 politicians were composed of 29 members of the Oireachtas (parliament) and four representatives of Northern Ireland political parties. For the 66 citizens and the 33 politicians an equivalent number of alternates were also selected so that the assembly would not be diminished in numbers in the absence of some of its members. And indeed, the politicians did rotate quite a lot: “throughout the lifetime of the Convention, there were a total of 52 members from the Irish parliament who attended its meeting” (Farrell et al., 2020). The experts would be involved in the process but by giving lectures to inform the assembly with factual data, without directly deliberating. The parties were free to choose the way their politicians members were selected. For the citizens:

“the recruitment was done door to door by the polling company, with quotas. The random element was knocking on every 16th door within an area. On the contrary, in Canada they mailed letter and then did a lottery. In Ireland there are different electoral registers, here they used the Presidential electoral register for sortition.”6

This assembly came together for the first time in Dublin Castle in December 2012 for its inaugural meeting, with its first deliberative session in January 2013, and had the task of proposing recommendation on eight topics, mainly linked to articles of the constitution. A crucial point is that in Ireland, any constitutional change must be approved by referendum. Hence, this institutionally constraining framework largely explains the “deliberative enthusiasm” displayed by the political class, which is an adaptation to legal imperatives and should not be too quickly viewed as a “deep participatory conviction.” As it is impossible to modify the constitution without the direct approval of the people, it is therefore rational to consult a representative sample of the population before any referendum.

Its recommendations were to be transmitted to the government and parliament, which would decide if some could be submitted to a referendum. Eight items were given by the government, while two others (9 and 10 bellow) were chosen by the CotC via public consultations through public meetings and an online platform, leading to a hybrid input legitimacy:

1. Reduction of presidential term

2. Reduce voting age

3. Role of women in home/public life

4. Increasing women's participation in politics

5. Marriage equality

6. Electoral system

7. Votes for emigrants/N. Ireland residents in presidential elections

8. Blasphemy

9. Dáil reform

10. Economic, social, and cultural rights

This eclectic agenda was criticized for lacking coherence and ambition, with few important or divisive topics. As a commentator puts it: “There is no evidence of any kind of overarching theme or logic to the agenda—it seems to be a pick and mix of the least harmful political reform proposals put forward by the governing parties during the election campaign” (Wall, 2012).

The general deliberative model upon which the CotC was based was somewhat similar to the Canadian innovations, and in some ways to the Icelandic and Belgian cases, and more broadly to the general process of deliberative mini-publics. Under the supervision of a Chair and a senior civil servant assisted by three staff members, the participants came together one weekend a month, during which they auditioned experts and then deliberated in small groups, which were pseudo-randomly shuffled each weekend. Those meetings, held in Malahide Grand Hotel (Malahide is a small city north of Dublin), benefited from paid facilitators and note takers. As the Secretary of the Convention admits: “I did most of the organizational work (…). Having note-takers and facilitators, it was Farrell's idea (…). He was correct.7” Farrell explains: “We shook the trees to find facilitators to pay: PhD students, Master students and barristers (lawyers). I mainly did the recruitment process and training, with role-play sessions.”8 Contrary to the fears of many commentators, surveys reveal that the 66 citizens did not perceive the debates as being dominated by the 33 politicians (Suiter et al., 2016a). After each small group deliberation, the CotC asked questions of the experts. Each topic was concluded by a vote on the recommendations the assembly wished to transmit to the government (Arnold et al., 2019). Interestingly, as the Chair notes, at the very first weekend the CotC voted to reduce the voting age to 16 while the agenda of the Government was to consider 17; “from a procedural point of view what was important was a willingness to slightly extend the… not so much the term of reference, but how you were dealing, how you were interpreting the term of reference.”9 This allowed for a robust throughput legitimacy.

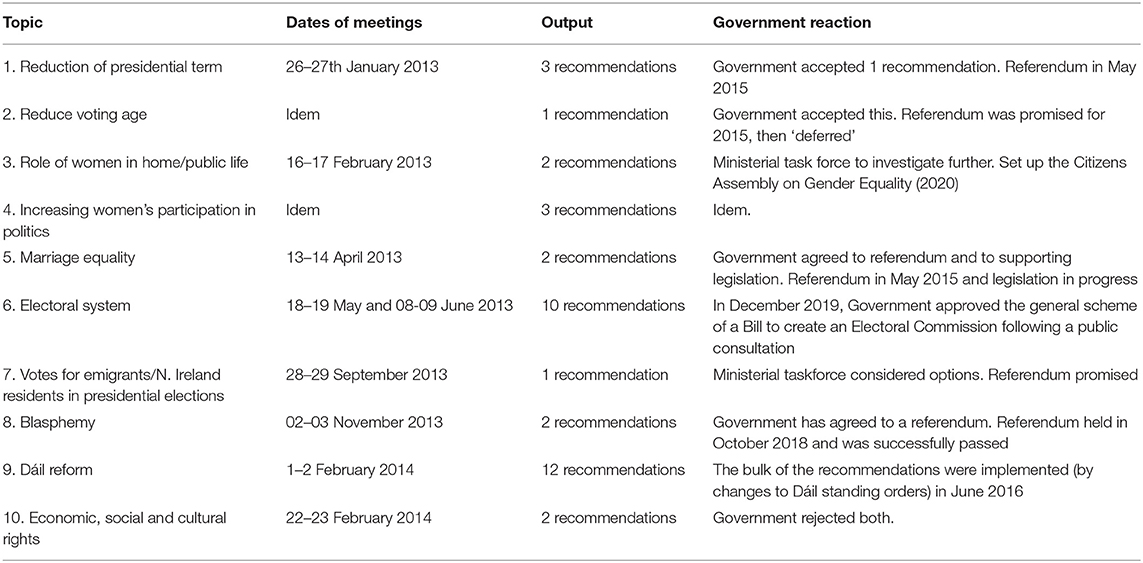

The CotC's work was concluded in March 2014. Its output legitimacy is a contrasted one. While the government and Parliament directly integrated some of its recommendations into legislation, some others were not even debated (Farrell et al., 2018; see, Table 3). In this way, the elected officials conducted “selective listening” or “cherry picking,” as observed in many participatory institutions (Smith, 2009; Nez and Talpin, 2010, 214). At the time, only two of its recommendations were put to a referendum: the legalization of same-sex marriage and the reduction of the age of eligibility for the presidency from 35 to 21. Due to its importance, the first issue completely “overshadowed” the second. On 22 May 2015, the “marriage equality” referendum gained an astonishing majority of votes (61%) in the follow-up to an intense campaign, during which most parties supported the “yes” side (Elkink et al., 2017). However, on the same day, the reduction of the age of eligibility for the presidency was rejected due to a lack of public awareness and media exposure, that led to most Irish citizens only discovering the existence of a second question when they came to vote.10 These results prove the limitations facing the CotC, especially the lack of awareness of its existence among the general population, which is a common feature shared by many democratic innovations, therefore restraining their impact (Crosby and Nethercut, 2005; Goodin and Dryzek, 2006; Fournier et al., 2011). After a long period of time during which none of the Convention's propositions was submitted to popular vote, the offense of blasphemy is finally removed from the Constitution with almost 65% support in the 26th October 2018 referendum.

In February 2016, new elections were held, breaking the Labor/Fine Gael coalition and leaving the latter in the position of a minority government. One of the commitments of Taoiseach (Prime Minister) Enda Kenny, leader of Fine Gael, was to summon a new constitutional assembly in the follow-up to the perceived “success” of the first one. However, even though the main issue remained societal and not economic, abortion is a highly divisive issue—much more so than “marriage equality,” which was broadly supported. As a deeply Catholic country, Ireland made the ban of abortion from a legal to a constitutional disposition—the 8th Amendment or Article 40.3.3—in a 1983 referendum, with the island thus becoming “the only country to inscribe the right to life of the ‘unborn child’ in its Constitution” (Nault, 2015).

In the fall of 2016, a second deliberative assembly was set up with significant changes compared to the previous one, which makes this “institutionalization” contrasted and complex. Composed exclusively of 99 randomly selected citizens and chaired by a Supreme Court judge, this democratic innovation—simply called the Citizens' Assembly (ICA)—was given the task of crafting recommendations on five issues:

1. The Eighth Amendment of the Constitution (abortion)

2. How we best respond to the challenges and opportunities of an aging population

3. How the state can make Ireland a leader in tackling climate change

4. The manner in which referenda are held

5. Fixed term parliaments

No reason was officially given for a major change: the non-participation of politicians in this new assembly. The true reason was in no way an “organizational learning” or a reaction to potential problems in the CotC, largely complimented by both citizen and politician members, but was rather linked to the very nature of the issue, as abortion is perceived as being politically dangerous. Hence, most politicians refused to take a public stance on abortion out of fear of losing votes or their seats due to the deep cleavage among the electorate on this question. A parliamentarian explained: “When we go canvasing, it happens that some people ask about our opinion on abortion, and they make it clear that this issue only will determine their vote.”11 The construction of this deliberative device is therefore deeply embedded in the “politics of blame avoidance” (Weaver, 1986; Hood, 2010), here the mini-public is given a task politicians refused to deal with themselves for fear of public backlash from one side or the other.

Other differences between the CotC and the ICA are revealing. The number of topics was lowered from 10 to five, while the importance of the issues increased, which could allow for more efficient deliberation. However, the constitutional dimension was not necessarily obvious for the issues of the aging population or climate change. To use Hans-Liudger Dienel's distinction (2010, 108), the ICA's five topics were a mix of “open” and “closed problems,” the former “presenting no clear cut solution” but requiring “new ideas,” while the latter being “a conflictual issue imposing the search for compromise between several known solutions, but incompatible and antagonistic.” Typically, climate change is an “open problem,” while abortion is a “closed one.” The time given to each topic differed, with an initial planning of four weekends for abortion and then one per remaining topic. Due to demands from the assembly itself, Parliament granted three additional weekends for dealing, respectively, with abortion, the aging population, and climate change, revealing that the ICA had a bit of agency. Citizen representatives also managed to move climate change from the last to the third position (Courant, 2020a). However, the ICA's agency was less than that of its predecessor, the CotC, which had the opportunity to choose two of its 10 topics. This crucial point, undermining the input legitimacy, will be discussed further in the following part.

The civil servant staff completely changed over from one assembly to another, which presented a serious risk of “loss of organizational knowledge,” but the former team did communicate with the new team to explain their know-how.12 The Secretary to the ICA underlines:

“And of course you can improve on it then, because you are improving on a system that was there already, they were the ones who pioneered it. And so some of the thing that are easier for me because I have the benefits of their wisdom, which means I have time to concentrate on other things. The staff of the previous one, the secretary and the team, were incredibly helpful to us, providing us with their lessons and their learnings and pointing to potential pitfalls, things to look out for.”13

The location was identical, but the polling company in charge of recruiting the representative sample changed in favor of Red C, as the diversity of the CotC was deemed unsatisfactory. Indeed, some doubts were cast on the quality of the previous random selection done by Behavior & Attitudes, as David Farrell points out:

“some citizens in the CotC knew each other prior, which shouldn't have happened with good random selection. The opinion poll company, took shortcuts, they did a bad job, they took students, three or four were students of mine, one couple was from the same household. They came to the house and asked a first person, then a second.”14

In contrast, Red C committed to a qualitative recruitment of the panel with a more rigorously random door-to-door first contact, “even though it was expensive and time-consuming,” as its director underlined.15 Beside randomness, the pollsters also had to respect representative criteria: gender, age, location, and social class—but not county which led to some counties not being represented. However, in February 2018 a random check of the recruitment process by Red C revealed that one of their employee did not follow the protocol and recruited seven persons, for replacing departing members, through telephone conversation and “through friends and family of the recruiter.” As a result, “the replacement members, who attended just one session of the assembly held on January 13 and 14 dealing with ‘The Manner in Which Referenda are Held’ have been relieved of their duties” (Bray, 2018). These two cases raise questions: can a mini-public acquire public legitimacy if doubts are cast over the random selection procedure (Courant, 2020b)? It also reveals that the “quality of representation,” a part of input legitimacy, should not just be evaluated by “ticking the box” of “random selection” but by investigating qualitatively how this selection was carried out in practice.

Some facilitators involved in the previous assembly returned to the ICA but this time within a professional structure, the consultancy firm Roomax, specially set up for this event, gaining expertise through the process.16 In Ireland as in other countries, the institutionalization process of democratic innovation was followed by the “professionalization of participation” (Nonjon, 2005; Lee, 2015), which can increase throughput legitimacy. Contrary to the CotC, the ICA had two separate roles for academics. On the one hand, two “officially appointed” researchers were only there to study the mini-public through pre and post-deliberation surveys at each weekends. On the other hand, other academics were participating in the organization of ICA in an Expert Advisory Group, which had the purpose of drafting the deliberation program and proposing speakers. Previously, the two roles were mixed in the CotC. Few external researchers were also allowed to attend, but if a small number was present on occasion and mostly for just one weekend, I am the only one who observed every single session.

As with its predecessor, the inaugural meeting was held in Dublin Castle in the presence of the Taoiseach and many journalists, but party leaders and other politicians were absent this time.17 The following meetings, in Malahide, followed a very similar procedure to those of the CotC, with one meeting every month or so, expert lectures, roundtable deliberations in small groups assisted by professional facilitators and note takers, plenary Q&A sessions and discussions, and at the conclusion of a topic, a formal secret vote.

Fervent Catholics and pro-life activists opposed the citizens' assembly before its deliberations had even begun, through social networks and protests in front of Dublin Castle and then in Malahide, but in limited numbers—less than 30 in Dublin and between one and six in Malahide.18 More surprisingly, the pro-choice far-left was quite vocal against the assembly as well, arguing that the government was “kicking the can down the road” instead of having the courage to tackle the issue directly. They argued for a debate in Parliament and a referendum, without the delay and expense involved in a deliberative device; it seemed logical as opinion polls did show that a majority of Irish citizens were in favor of legalizing abortion, but mostly under conditions. These claims were also aimed at justifying the existence and utility of small pro-choice parties and to criticize a center-right government they opposed in general. However, feminist pro-choice activists from the Repeal the 8th coalition gradually lost their skepticism, as comments and questions broadcast during the livestreamed plenary sessions by the randomly selected citizens of the assembly showed their insights and accuracy.19

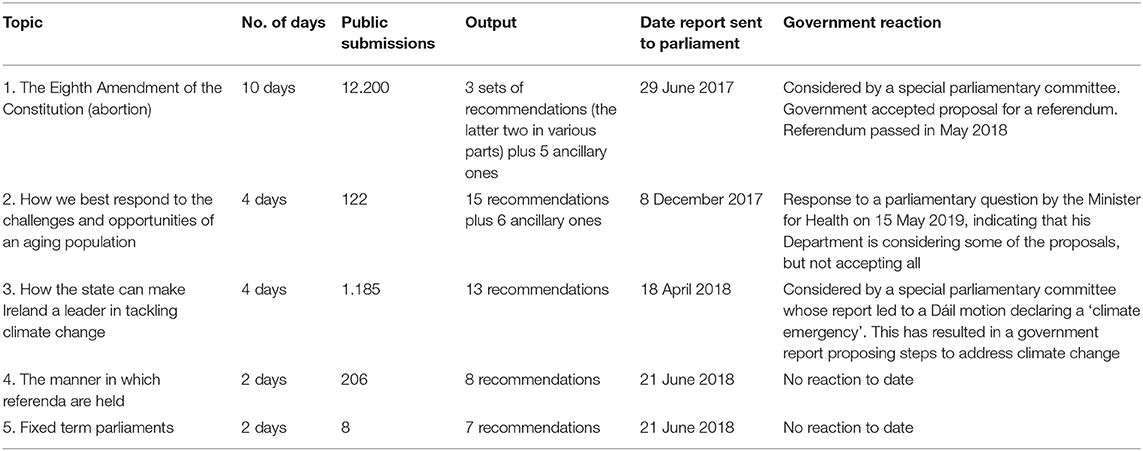

The citizens' assembly deliberated for five weekends on abortion, from November 2016 until April 2017. The citizens listened to many experts, representatives of advocacy groups, and individuals giving testimonies. Its website and Secretariat also gathered over 12,000 submissions from both organizations and individuals. In April 2017, ICA members had a secret ballot vote, which resulted in wide support in favor of legalizing abortion (64%). Their recommendations were put together in a report submitted to Parliament and closely studied by a parliamentary joint committee. The latter's deliberations reached a similar result, so the repeal of the 8th amendment was put to a referendum. This referendum was also made possible by the mobilization of activists and concerned citizens in the public sphere, especially through demonstrations, asking the Taoiseach (Prime Minister) to “Listen to the Citizens' Assembly,” as written on some signs, and to accept to have a referendum. Indeed, the first reaction of the Taoiseach, Leo Varadkar, to the “liberal” recommendations of the ICA was to say that “the country is not ready for abortion on demand,” arguing “I honestly don't know if the public would go as far as what the Citizens' Assembly have recommended” (Doyle, 2017; Hayden, 2017). In the follow-up to an intense campaign between pro-life and pro-choice, the Irish people voted in favor of the right to abortion in proportion somewhat similar to that of the ICA, with 66.4% “yes” and a historical turnout of almost 65% (Elkink et al., 2020), thus granting a strong output legitimacy.

A fourth citizens' assembly, this time on gender equality, was established in July 2019 by the Parliament. However, being still in process and disrupted by the Covid19 pandemic at the time of writing, it was not possible to fully include it as a case. Nevertheless, we already know that this new CA is also made up of 99 randomly selected citizens, as the previous one, but this time the “members are being paid a stipend on a per weekend basis” (Harris et al., 2020, 9), as it often the case for mini-publics. The CA is tasked to make recommendations to the Parliament on various items:

• “challenge the remaining barriers and social norms and attitudes that facilitate gender discrimination (…);

• identify and dismantle economic and salary norms that result in gender inequalities (…);

• seek to ensure women's full and effective participation and equal opportunities for leadership (…);

• scrutinize the structural pay inequalities (…)” (Government Press Office, 2019).

Previously, in July 2019, the Citizens' Assembly Act was passed by Parliament, but despite its impressive name this one-page act only allows “for the access and use of information contained in the register of electors established under the Electoral Act 1992 for the purpose of selecting citizens of Ireland to be members of certain citizens' assemblies” (Oireachtas, 2019); without any other specification as to the shape, power or frequency of such CAs. Another CA, a local one this time, was also announced in 2019 to consider local government in Dublin but is not up and running at the time this article is being published (October 2020). Those two new assemblies angered The Irish Times (2019) as lacking the justification because relating to “purely political issue(s) which TDs (deputies) are well capable of deciding.” The tendency toward using more and more CAs is not slowing down as the recent Programme for Government includes several commitments to establish others CAs on various topics (Government of Ireland, 2020). Nevertheless, for the issue of marriage equality and abortion, in the Irish case, as in many others, “the use of deliberative processes can render formerly blocked situations finally governable” (Lascoumes and Le Galès, 2012, 53). The ICA was largely described as a major success; however, the Irish “contrasted institutionalization” (see, Table 2) of democratic innovations raises problems and challenges.

Ireland is the first country in the world where four nation-wide citizens' assemblies were held successively, and the first country were some propositions crafted by randomly selected citizens were approved by the maxi-public through referendums. Indeed, even though the British Columbia citizen assembly's proposition for electoral reform managed to reach over 58% of the vote, the 60% threshold for the referendum to be successful was missed (Warren and Pearse, 2008). The similar process in Ontario was even more clearly negative, with only 37% voting “yes” (Fournier et al., 2011). As for the new Icelandic Constitution, even though two randomly selected assemblies participated in the process, the text was drafted by an elected assembly—admittedly composed of non-professionals but famous and elected nonetheless. Moreover, this constitution was never approved by Parliament and has yet to be implemented (Bergmann, 2016). In that regard, the deliberative Irish process was an impressive “output success” but suffered from its own limitations and problems, directly related to its lack of institutionalization. Its limitation can be seen in all dimensions of input, throughput and output (Bekkers and Edwards, 2007; Papadopoulos and Warin, 2007; Caluwaerts and Reuchamps, 2015; Reuchamps and Suiter, 2016), which I analyze one by one, after studying first a transversal dimension: politicians' influence.

First, as in many other instances, the elected officials had a decisive influence over the fate of the democratic innovation, on the input, throughput and output levels, which left room for arbitrary decisions and strategic self-interested orientations. Politicians have the power to decide:

1. whether they want to set up a deliberative device or not,

2. when,

3. on which topics,

4. for how long,

5. who supervise it (which influences speakers' selection),

6. its budget,

7. and more crucially, its output, what happens to the recommendations.

A striking feature of the Irish state-mandated assemblies was the absence of economic issues amongst the topics chosen by the political class. The reflection on citizen-led reforms started as the country faced an economic crisis and questioned its economic model (Farrell, 2014). Moreover, one of the three issues emerging from “We the Citizens” bottom-up participatory agenda setting was precisely the trade-off between tax increases or spending cuts (O'Malley et al., 2020). However, among the eight topics given to the CotC by politicians, none was related to the economy (e.g., voting age, removal of blasphemy as an offense, the right to vote from abroad, etc.), but because the assembly was granted the right to choose two additional issues through public consultations, the topic of “economic, social, and cultural rights” was eventually selected (Suiter et al., 2016a). However, the two recommendations on this topic were rejected outright by the Government. For the ICA, the questions of the aging population and climate change could be seen as linked to the economy; however, a structural reflection on the Irish economic model was not firmly put at the center of focus (Courant, 2020a).

So far, of the 10 topics leading to 40 recommendations by the CotC, only three were submitted to referendum, and some were rejected or proper responses such as referendum were postponed for years, possibly forever (see Tables 3, 4). Nevertheless, in the follow-up to the 8th Amendment referendum, the government seemed committed to holding more referendums on propositions coming from the two official deliberative assemblies. In terms of output, an institutionalization could render the articulation between deliberation and referendum systematic, without giving the political class the opportunity to decide whether they want to give a voice to the electorate. This was the case in Canada, where governments were committed to submitting the assemblies' proposals to voters before knowing what they would be.

Table 3. The CotC's uptakes—adapted and augmented from Farrell (2018) and Harris et al. (2020).

Table 4. The citizens' assembly (2016–2018) uptakes—adapted from Farrell (2018) and Harris et al. (2020).

Secondly, on the input level, on the one hand the CotC had the opportunity to choose two of the topics under deliberation through public consultations while the eight others were given by the Government and Parliament, but on the other hand the ICA had its agency reduced and was strictly constrained to the five issues given by Parliament. This change suppressed an opportunity for deliberation between the maxi- and mini-publics. The consultations in Canada and the Netherlands (Fournier et al., 2011), the online participation in Iceland (Bergmann, 2016), and the bottom-up agenda setting in Australia (Carson et al., 2013) and Belgium (Jacquet et al., 2016; Caluwaerts and Reuchamps, 2018) were important elements of democratization. The Irish case displayed a tendency toward reducing public input. “We the Citizens” pilot assembly had its agenda set by seven participatory public meetings. For the two topics it had the right to choose, the CotC decided to consult the public to decide which would be those topics (Arnold et al., 2019). However, in the ICA, the only public input was through written submissions, without the possibility of direct interaction or deliberation; apart from presentations from a few selected interest groups' representatives. A democratic institutionalization could render the agenda-setting procedure more systematic, transparent, and open to public input. The stronger way to guarantee a strong input legitimacy would be to establish a right of initiative, a direct democracy mechanism (Papadopoulos, 1998), allowing the maxi-public to petition and gather signatures to choose the topics a CA should deliberate on.

Moreover, in the three first CAs, the agenda was composed of items with no logical connection between them. The eclectic agenda of the CotC and of the ICA give an impression of an incoherent patchwork of issues, perhaps of which the main common thread was that the political class did not want to address them itself. The change from very different topics is one of the explanations of the high citizens' turnover in the ICA, participants were committed to follow an item from start to finish and to vote on it, but felt less inclined to start over for entirely different issues (Courant, 2018b). However, this seem to be changing as the new CA on gender equality is mono-topic, as for the French and British CAs on climate change.

The eclectic aspects of the Irish CAs' remits make it difficult to understand the intended function of those mini-publics. Dryzek (2016) distinguishes five roles for deliberation in the policy process: “a limited input into analysis of the relative merits of policy options; a means of resolving conflicts across relevant actors and interests; a form of public consultation; a unique source of valuable inputs into policy processes; a comprehensive aspiration for whole systems of governance.” Because of its various topics and uneven uptakes, the Irish CAs can be considered as embracing simultaneously each of these roles, depending on the topic and its treatment. For instance, on the voting age the CotC provided “a limited input into analysis of the relative merits of policy options,” on marriage equality it was “a means of resolving conflicts,” while on abortion the ICA was “a unique source of valuable inputs.”

Third, on the throughput level, my empirical ethnographic observation of the interactions within the Citizens' Assembly reveals some constraints: “call to order” and lack of agency for the citizens. Indeed, mini-publics in general and the Irish CAs especially rely on a strict “division of deliberative labor” between the following actors and tasks:

1. Sponsor (Government and Parliament): establishes a deliberative forum on topics of its own choosing, select the Secretariat and the Chair.

2. Secretariat: select the other actors and run the process, in collaboration with the Chair.

3. Chair: chair the debates, help the Secretariat in running the process, presents the report.

4. Polling company: recruit the citizens' panel.

5. Expert advisory group: monitor the process, propose, and select the speakers (experts and stakeholders), prepares the ballot.

6. Steering group: approves the program.

7. Facilitators and Note-takers: help the deliberation to be fair and efficient.

8. Experts and stakeholders: contradictory, inform the panel.

9. Randomly selected citizens: listen, learn, deliberate, recommend, and vote.

Moreover, the climate of extreme tension surrounding abortion rendered the proceedings of the ICA in some ways more coercive than those of its predecessor. The ICA's chair, the Hon. Ms. Justice Mary Laffoy, in conformity with her habitus of Supreme Court judge, led the debates with an assertive approach, leaving little space for contestation to arise among participants, which can be a problem from an “agonistic perspective of democracy” (Mouffe, 2000). Her use of time tended to favor expert lectures, which often ran over their allocated time, over the small groups and plenary session deliberation time. The governing style of a chair is affected by the actor's professional habitus. This was the case in Canada, where Jack Blaney in British Columbia adopted a “liberal approach,” letting “members talk as much as they wished even if this meant going over time” (Fournier et al., 2011, 105), while in Ontario, George Thompson, a “former deputy minister and family court judge” (Fournier et al., 2011, 29), had not “granted participants with the same level of trust as Baney,” according to Lang (2010, 127). Similarly, CotC's chair Tom Arnold, coming from an international charity NGO, conducted the deliberations in a way that increased the participants' agency, while Laffoy followed a stricter practice of her “role.” The chair's room to maneuver could be lowered to the participants' benefit if a long-term deliberative institution were to be institutionalized, due to clearer rules and a standardization of the “role” (Lagroye and Offerlé, 2010; Dulong, 2012).

Aside from the Chair, the influence of the Expert Advisory Group (EAG) is also critical as they prepare the learning program and propose the speakers, as well as the ballot upon which the citizens vote. If the procedure for amending the ballot was spotless for the issue of abortion and of the aging population, the deliberative and procedural quality then lowered for further sessions, especially for climate change. In this session, the Chair and the EAG rejected the majority of modifications requests made by the citizens instead of letting them decide (Courant, 2020a). Contrary to the previous times, the Chair did not call for vote by a show of hand in case of dissensus but sometimes asked for a vague oral expression. This practice was criticized by a citizen member:

“What did you think of the ballot and the voting? I think it was very sloppy… You make a suggestion and some people shout ‘No’… and that's it. No vote. No show of hand. Members at my table reacted: ‘How many said ‘no’? We don't know’. It is very disappointing (…). The procedural mistake will damage the credibility of the process…. And the EAG, they have too much power on the ballot. It is not right. It's not just me, other citizens told me so.”20

The core problem might be as follow: there are no public deliberations for setting up deliberative mini-publics or organizing them. A lot of the choices made by the organizers are made behind closed doors and without giving reasons justifying those choices afterwards. In the Irish case few citizens members took part in steering group meetings, which is a way to address the issues but data shows that it was insufficient (Suiter et al., 2016a; Courant, 2020a). In this regard, theoretical suggestions have been made for “critical mini-publics” (Böker and Elstub, 2015) but empirical studies of existing practices remain to be conducted and institutional designs of “meta-deliberation,” that is deliberation on the procedures and conditions of deliberation itself, remain to be implemented (Courant, 2020a).

Fourth, on the output level, the impact of the mini-publics' deliberation on the maxi-public's vote is complex. While the electorate did follow the ICA's recommendations to legalize same-sex marriage and abortion, it rejected the one to reduce the age of eligibility for the presidency. Therefore, the hypothesis of systematic support toward propositions crafted by citizens' assemblies is invalidated once again. The claim that “adding politicians along citizens in mini-publics” will make the CA's recommendation impossible to reject was also invalidated.

Nevertheless, empirical quantitative studies reveal that if a citizen knows about the existence of a citizens' assembly, he or she will be more likely to support its recommendations (Warren and Pearse, 2008; Fournier et al., 2011, 132). The problem is therefore the lack of public visibility of democratic innovations. A significant part of the Irish citizenry was unaware or weakly aware of the existence of the CotC at the time of the referendum, but the “informed part” was influenced in favor of following the CotC's recommendations (Pilet, 2016). As Elkink et al. (2017, 371) show by checking for the awareness of the CotC with four statements: “Taking ‘don't know’ as a lack of knowledge, this leads to a five-point scale from zero to four indicating the level of awareness of the convention. In our sample, 54 per cent score up to two, a further 34 per cent have three items correct, and the remaining 12 per cent are fully aware of the Convention.” They also show that “while there is no discernible impact on the likelihood of turning out to vote, there is a positive and statistically significant effect on the probability of voting yes” (Elkink et al., 2017, 372), but that the impact of the referendum campaigns was more important in explaining the outcome.

However, the Citizens' Assembly benefited from stronger media coverage, especially due to the controversial nature of its first topic. As Suiter and Reidy (2020, 550) underline, for the abortion referendum “66% were aware of the mini-public.” The question remains: if the ICA was known by a fair share of the electorate, how exactly did it influence the referendum's outcome? This has yet to be definitely proven, but “exit polling data suggested many voters in Ireland had made up their minds on abortion before the official campaign began” (Press Association, 2018a). However, if the majority of Irish voters were in favor of a legalization of abortion, it was under conditions (rape, health issue…) before the assembly's deliberations, which lead to its proposition: abortion without condition. This proposition was approved by referendum revealing that the opinion of the maxi-public evolved in the direction of the mini-public. Moreover, Elkink et al. (2020, 6) show that, once again, “knowledge of the Citizens' Assembly made one significantly more likely to vote yes” but “voters' levels of personal trust in the Citizens' Assembly, however, did not affect the vote choice.” Suiter and Reidy (2020, 551) note that “the Constitutional Convention at the marriage referendum and the Citizens' Assembly at the abortion referendum also mattered by enhancing the quality of vote choice;” but, surprisingly, their analysis does not take into account the failure of the referendum on the age of eligibility for the presidency, therefore somewhat skewing their conclusion. Moreover, all credit cannot be attributed to citizens' assembly; social movements, protests, local debates, and campaigns also played a role, but also demographic factors revealing a tendency toward liberal opinions, especially church attendance and age (Elkink et al., 2020). The impact of the CotC on the referendum on blasphemy has not yet been demonstrated.

More crucially, in Ireland the maxi-public's vote for “yes” in the referendum on abortion was in the end higher that the mini-public's vote in the assembly. Hence, one can wonder if this does not disprove a central claim made by deliberative democracy scholars, that “the mini-public considered opinion is qualitatively superior to the opinion of the population at large” (Fishkin, 2009). If the referendums had been carried out without the CAs' deliberations beforehand, would the results have been different in a significant way? Despite some statistical studies, this question remains. Regardless, it seems likely that greater institutionalization and regularity of deliberative processes would increase the population's awareness and achieve greater uptakes (Goodin and Dryzek, 2006; Warren and Gastil, 2015). A stronger institutionalization linking deliberative mini-publics (DMPs) to referendum has been achieved further afield from Ireland, in various States of the United States with the Citizens' Initiative Review (CIR). In this process, the statement of the citizens' panel is mailed to all the voters by the official authorities (Knobloch et al., 2015). However, using the media in deliberative democracy remains a challenge for structural reasons (Parkinson, 2005).

There are two ways of looking at those “limitations.” On the one hand, one might argue that the lack of institutionalization allows for greater flexibility and adaptation to various situations. In this perspective, elite decision makers need to change the shape and procedures of a democratic innovation as they see fit; therefore, appointing a judge as chair, setting up an eclectic agenda and restraining the assembly's agency might have been necessary conditions for the crucial but divisive abortion issue to be tackled efficiently. On the other hand, the lack of institutionalization is potentially what prevents certain democratic innovations from meeting great expectations. A form of institutionalization could insert deliberative procedures into the “ordinary political life,” as elections are, and allow for deeper political improvements.

We saw that the Irish process was contrasted with great achievement but also limitations. Is Ireland actually crafting new democratic institutional models transferable abroad? And if so which ones?

A core dimension, if not the main, of deliberative democracy is a focus on fair procedures. A decision is not just or fair because the majority is in favor of it but because the deliberative procedures to reach this decision were fostering: equality, inclusion, fairness, transparency, and an impartial weighting of all competing arguments (Manin, 1987; Dryzek et al., 2019). We have seen that there were some shortcomings in the Irish process, but globally its deliberative procedures and quality were good, respecting most of the usual standards (Gastil and Levine, 2005; Fishkin, 2009; Reuchamps and Suiter, 2016). However, compared to the previous CAs, the CotC and to a lesser extend the ICA were downgrades in term of deliberative quality regarding the shorter time given to each items. While the three assemblies on electoral reform in Canada and the Netherlands had dozens of weekends spread over a year to deal with one topic, the CotC did not give more than 4 days per topic. There is no documented evidence of any deliberative improvement in terms of experts auditions, small-table discussion or plenary deliberation when comparing Ireland to its predecessors, or its successors like the French Climate Convention and its 9 weekends, two of which being held online due to the pandemic (Courant, 2020a).

The main difference is that in Ireland, 3 out of 4 referendums emerging from the mini-publics were successful, even though with 58% of “yes” the British Columbia CA was only defeated by an excessive super-majority threshold. This makes Ireland a politically successful case with a quantitative approval but not necessarily a deliberative improvement. Moreover, beyond procedure one must take substance into account. Would Ireland be considered a “model” if its mini-publics had advised against marriage equality and legalizing abortion? And this even if the rest of the features were present (i.e., successful referendum, qualitative deliberation, diversity of experts…)? Isn't there a bias that “as long as mini-publics are saying what one believes, one supports them”? The fact that many commentators, activists or academics (myself included) were favorable to marriage equality and legalizing abortion prior to the CAs deliberations is likely to be an important factor for them to qualify the Irish cases as a “success” or “model;” most of those actors having actually very little knowledge of how the Irish CAs operated concretely. Deliberative mini-publics (DMPs) should be valued for the quality of their procedure, not for merely approving a policy one already believes in, otherwise they are bound to remain a marginal aspect of political life.

As we have seen, there is no such thing as a clear “Irish model” given the important differences between its various CAs (see, Table 2). Nevertheless, some claimed, especially prior to the ICA 2018 successful referendum on abortion, that the main reason for “output success” in Ireland was the mixing of politicians and citizens in the CotC; contrasting it with the Icelandic “failure” (Renwick, 2015; Suteu, 2015; White, 2017). It was already proven that this claim does not hold; mainly as the recommendation on the age of the president was massively rejected by referendum and other recommendations were rejected by Government or Parliament. However, the hybrid assembly was a clear originality proper to Ireland. But does it “work,” as many have said (Honohan, 2014; Van Reybrouck, 2016)? Survey results show that members of the CotC did not think that politicians dominated the debates (Suiter et al., 2016a). However, a more detailed quantitative approach, but relying on a limited “n” with sometimes only 6 or 9 respondents for the politician members group, reveals that “there was a moderate liberal bias among those politicians who chose to become members of the Convention. And while this does not appear to have influenced the outcomes of its decisions (…), in one respect at least the presence of politician members does appear to have affected the outcome—on the issue of electoral reform, a matter of considerable personal interest to politicians” (Farrell et al., 2020). Indeed, I concur and argue that a mixed DMP only works under certain specific conditions, which are the following:

1. Proportion: the politicians were in minority, one out of three. Sixty-six citizens constitute already a small number in order to get a diverse sample, lowering it more would deteriorate its representativeness and its cognitive diversity.

2. Strong deliberative design: the deliberative procedures were based on those of a citizens' mini-public rather than parliament. The Chair crafted some deliberative principles that he repeated at each meeting: openness, fairness, equality of voice, efficiency, and collegiality (Arnold et al., 2019). Those principles were taken and repeated by the two following Chairs of the subsequent Irish CAs'. On the contrary, in the Australian 1998 Constitutional Convention, “the only other case (…) of a convention whose membership comprised a mix of politicians and ordinary citizens (though these were not randomly selected); there the decision was taken to operate along normal parliamentary lines” (Farrell et al., 2020).21

3. Awareness: the 14 facilitators, the Chair and the Secretariat were explicitly vigilant so that politicians did not dominate the debate. As the Secretary underlines: “The facilitators and note-takers, their job was to manage big voices at roundtable discussions, that was very important.”22 And the Chair points out:

“The equality issue then, that really was put in to address the fact that there was concern at the very beginning that politicians would dominate citizens. And I felt it was really important to say from the very beginning: ‘everybody here is equal’. And that came even to a simple thing like me saying at the very first meeting: ‘nobody is going to have any title here, your title is your first name’; so it didn't matter if you are a Minister or a TD (member of parliament) or anything else, or a doctor or whatever, you were going to be called by your first name.”23

4. Independent Authority: the Chair, Tom Arnold, experienced leader of a well-known charity, and the Secretary, Art O'Leary, with his experience as a senior civil-servant, were respected by the politicians, and unsuspected of bias. O'Leary could call the politicians to order if they were stepping out of line or being absent, has he says himself:

“One benefit of me having come from the Parliament is that I was able to ring the politicians on their mobile and say: ‘I need you to be there tomorrow. I had this ridiculous call from your secretary ringing in to say that you won't be there. That ain't happening. If you don't come I'm gonna ring the Taoiseach and tell him that you're refusing to go, or I'll ring the government chief whip or someone’. So there was coercion, encouragement, bullying… everything to get the politicians into the room.”24

5. Anonymity: the politicians were in principle free to speak and vote without fear of the party whip; this required that all votes were anonymous, so no distinction could be made between citizens' and politicians' votes'. Without this feature the deliberative dynamic would have likely been compromised, politicians would have followed their party lines and refused to change their minds in light of new arguments.

6. Topics: most issues debated by the CotC were consensual, however the sessions on the electoral systems and even more on Parliament reform were tense. One advantage of having “ordinary citizens” talking about constitutional reforms is that they do not have a direct vested interest in the “rule of the game,” contrary to professional politicians (Thompson, 2008; Courant, 2019b). More generally, deliberation in a mixed-assembly might be compromised if the issues being debated are highly divisive and leading to a strong cleavage between the political parties involved. A citizen participant of the CotC explains:

“One of the piece we had to discuss was whether we should abolish the Seanad (Senate) or not (…). The Constitutional Convention had its tasks and interested parties could make submission for or against and that was the only way you could get your submission in, if you'd given it in advance. The Senators decided to bypass that and just bring in pre-printed materials and put them on all the tables. Which was very unfair. We didn't get time to read over them, they didn't go through proper channels, and they had a vested interest, with no opposing interest. And they forced that upon the Constitutional Convention. And it wasn't right (…). That was one of the few bad things that I've experienced in the Convention, in that members of the Convention sabotaged the Convention.”25

The hybrid composition of a DMP is therefore not easy and the “CotC model” should not be transferred to any other country or context without taking those six specific conditions into account. If those six factor were changed (having more politicians than citizens, following parliamentary procedures instead of deliberative ones, removing anonymity, etc.) one can make the hypothesis that this new mixed assembly would fail. Moreover, Ireland might show specific cultural features absent from other countries. Several interviewees told me that having a beer with a member of Parliament was not uncommon in Ireland, while it certainly is in France. The degree of “elitism” among politicians should also be taken into account. Regardless, politicians tend to come from higher social classes, having more wealth, higher degrees, symbolic or social capitals and confidence in public speaking. However, Farrell et al. (2020) suggest that “an additional weakness” of the CotC was its length, which allows the members to develop “a degree of ‘we’ thinking, reaching shared goals and outcomes. This speaks to the need to keep such process shorter in length.” Finally, mixed membership of citizens and politicians was also tested in the 2015 Democracy Matters CA, which led the involved research team to conclude: “At least in the short term, inclusion of politicians decreases the quality of deliberation (including the amount of perceived domination)” (Flinders et al., 2016, 42).