- 1Department of Anthropology, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN, United States

- 2Integrative Research Center, Department of Anthropology, Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, IL, United States

- 3Department of Anthropology, University of Georgia, Athens, GA, United States

- 4Department of Human Ecology, Centro de Investigación y de Estudios Avanzados del IPN-Unidad, Merida, Mexico

We have found that collective action theory, as developed by Margaret Levi and others, provides a new direction for the study of growth and decline of premodern states. By following this lead, we challenge the traditional consensus that despotic rule and relations characterized most premodern states, demonstrating instead a state-building process in which fiscal economies of joint production fostered the implementation of good government such as accountable leadership and public goods. In this paper we focus attention on causes and consequences of state decline, highlighting the decline pattern found in societies where there had been good government. Our comparative investigation reveals that while regimes providing good government policies and practices were highly regarded by citizens and brought benefits to them, they were not always enduring over time and regime decline was frequently followed by serious demographic and economic consequences. While causes of decline were varied, we describe and comment on four well-documented examples in which primary causality can be traced to a principal leadership that inexplicably abandoned core principles of state-building that were foundational to these polities, while also ignoring their expected roles as effective leaders and moral exemplars.

Introduction

The goal of this paper is to build on in-depth, cross-cultural comparative studies of premodern states (especially Blanton and Fargher, 2008) to propose a novel perspective on the causes of state collapse. To develop our argument, we first summarize key elements of our theoretical approach, grounded in collective action theory. We then link differing degrees of collective action to variable expressions of premodern state-building along an axis defined by the degree of good government policies and practices, following the criteria of Rothstein (Rothstein, 2011, 2014) and others. The theoretical lens that we employ predicts that states organized on the basis of collective action and good government provide collective benefits, but only insofar as leaders and citizens honor their mutual moral commitments (Levi, 1988). Our prior investigations documented that such states provided broader-based benefits than did more autocratic states. Yet, surprisingly, we also found that states with stronger commitments to good government were no more enduring than autocratic polities and, in fact, were more vulnerable to what we define as a “major” collapse pattern (including social unrest, agrarian collapse, and state failure). We argue that polities with higher degrees of collective action, owing to the mutual moral commitments between leaders and taxpayers, actually have a heightened vulnerability to major collapse when their leaders undermine the trust and confidence of taxpayers through amoral actions.

Background to the Focus on Collapse

While asking questions about collapse was not part of our original research design (Blanton and Fargher, 2008), we turned to the issue in light of the growing democratic backsliding of contemporary democratic nation-states. We read in the news every day about the rise to power of autocrats, electoral disfunction, official corruption, and growing distrust of governing institutions (e.g., Levitsky and Ziblatt, 2018), even in countries where democratic ideals had been honored for a generation or more, such as Hungary, Mexico, Venezuela, Turkey, and the United States. Yet, there is no consensus explanation for democratic “backsliding.” For example, Waldner and Lust (2018, p. 93) concluded in their literature review that recent efforts to explain backsliding “remain inchoate.” We wondered whether our research on premodern states might lead to new thinking about democratic decline that could enrich that conversation. To assess whether the investigations we implemented could have meaning for today, we had to revisit the commonly held assumption that the Western invention of democratic modernity was a radical departure from a human past in which state-building and government tended toward autocracy (e.g., Tilly, 1990, p. 21; Thapar, 1992; Acemoglu et al., 2005; North et al., 2009, p. 31, 112). This “Orientalist,” Eurocentric, and antiquated bias, informed by a presentist perspective, sees premodern states as an early social evolutionary stage in which passive citizens were dominated by self-interested authoritarians whose political power and divine status were bulwarks against good government reform.

Some have criticized the Orientalist claim, yet it is still expressed by contemporary authors willing to ignore key evidence (e.g., Scott, 2017; cf. Blanton, 2019). Others (e.g., Mayshar et al., 2017; Stasavage, 2020, p. 62) grant that premodern states were not always despotic yet see the exceptions as “weak” states in which principals could not exact taxes due to the friction of distance or informational constraints on production. Our research results throw an unflattering light on presentism, Orientalism, and evolutionism because practices and policies of good government similar to modern democracies were more common among premodern states than long presumed and those states were not necessarily weak, as our examples, described below, illustrate.

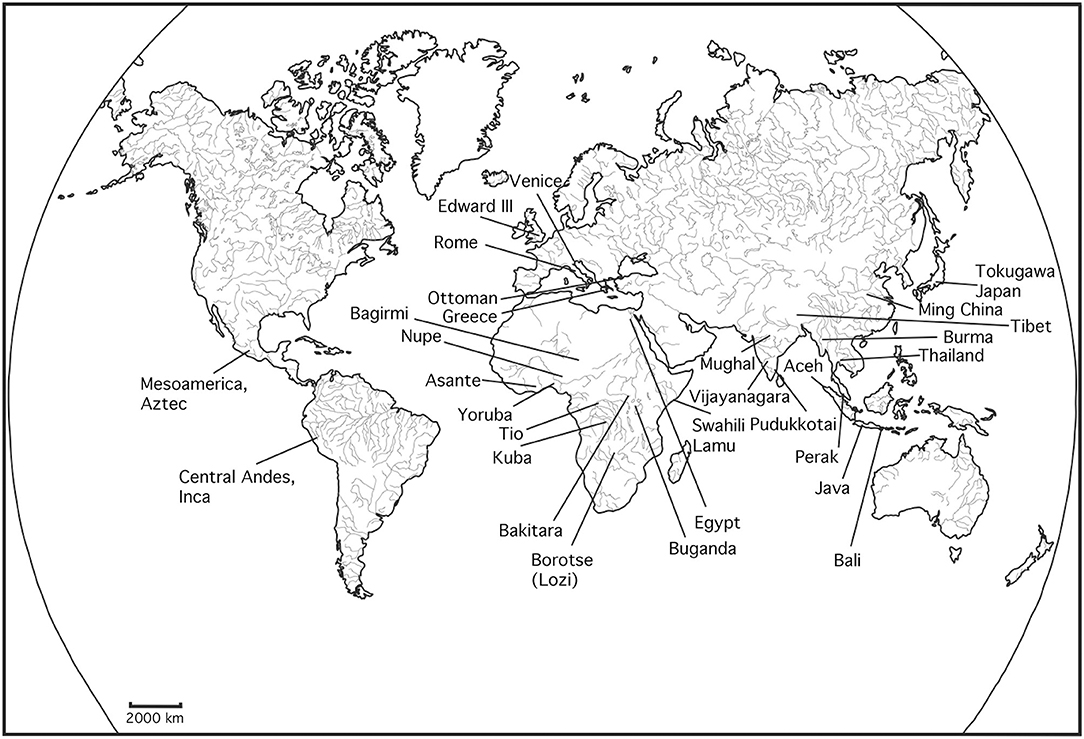

We first became aware of unexpected similarities between past and present states from our ethnohistoric and archaeological research experiences in China and Turkey but, especially, in Mexico (e.g., Blanton et al., 1996, 1999; Fargher et al., 2011; Feinman, 2013), where some urban capitals characterized by distributed power arrangements and collective action governed their respective sustaining regions for centuries. Other archaeologists, working in Mexico and elsewhere, have arrived at similar conclusions (Thurston, 2010; Cowgill, 2015; Carballo and Feinman, 2016; Fargher and Heredia Espinoza, 2016; Feinman and Carballo, 2018). Our main source for this paper is a cross-cultural comparative analysis of data collected from a world-wide sample of 30 premodern states whose political systems were endogenous, lacking influence from contemporary Western notions of democracy (Blanton and Fargher, 2008, 2016; a brief summary of theory, methods, and main results is found in Blanton and Fargher, 2009; Figure 1).

Figure 1. Locations of the coded societies. For selection criteria, coding methods, and coding, see Blanton and Fargher (2008).

Collective Action Theory

In the absence of suitable theory in our own discipline that would address similarities between past and present, we turned to the work of political scientists and economists who view state-building from the vantages of collective action theory (especially Levi, 1988, 2006, cf. Ostrom, 1990). This theory predicts that any group aiming to gain benefit from jointly produced and managed resources will be threatened by the cooperator problems of free-riding and shirking (in addition, state-building to realize collective benefit entails opposition from a privileged elite, who gain little from the costs of collective action, and numerous challenging coordination problems not addressed here [Blanton and Fargher, 2016]). Given potential threats to cooperative group success, group members understand that mutual benefit is maximized when other members accept the moral responsibility to act unselfishly and responsibly in relation to the production and management of shared resources.

In the case of states, collective action theory views cooperator problems as most likely to arise when taxpayers are the principal source of the state's resources in the form of taxes, labor, and military service (“joint production”), what political scientists and economists refer to as a “fiscal state” (Schumpeter, 1991 [1918]). In these states, revenues and other resources are produced primarily by the citizen population and the state is the principal institution charged with managing those resources for group benefit. To realize productive collective action the leadership will be motivated to supply institutions that equitably allocate member obligations (for example, by building institutions for equitable taxation) and benefits (for example, assuring equitable access to public goods across the realm). The leadership is also motivated to develop institutional means to monitor the adherence to group obligations of state agents and taxpayers and to sanction malfeasance, while agreeing to limits on their own agency1. Taxpayers who provide the bulk of the state's resources are assumed to be rational social actors who may choose to free ride or to shirk taxpaying obligations, opt out, or even oppose a leadership if they perceive that moral claims they make on leaders and fellow taxpayers are ignored (Levi, 1988, p. 53). In this way the theory focuses attention on those social factors that motivate rational taxpayers to comply with tax obligations, unlike most prior theories of premodern states-building in which taxpayers are viewed as passive victims of state appropriation (e.g., Mayshar et al., 2017)2.

By contrast, and also as expected from collective action theory, mutual moral accountability will be less salient when the leadership has direct and discretionary control over vast material and symbolic resources that are not jointly produced. Accordingly, leadership can mobilize resources to build and sustain its power while avoiding demands for good government reform (e.g., Winters, 2011). Thus, according to collective action theory, the actions of leaders are assumed to be contingent because they are strongly shaped by fiscal economy. This is a departure from much prior state-building theory that makes strong initial assumptions about how leaders act, for example when Charles Tilly blanketly assumes that state-makers were “coercive and self-seeking entrepreneurs” (Tilly, 1985, p. 169).

Key aspects of collective action theory are important to note for the aims of this paper. First, the sense of moral obligation found in collective action theory is very different from claims that cooperation grows from the moral sensibilities of a society's cultural code, for example, when Robbins and Kiser (2018, p. 249) argue that taxpayers will comply if they see the state as legitimate based on “an alignment of morals between citizens and rulers.” While local cultural beliefs will shape cooperative action to varying degrees (Ahlquist and Levi, 2011), collective action theory posits that mutual moral obligation arises primarily out of the management of jointly shared resources. Secondly, under conditions of collective action, leadership is understood to be strongly relational between leaders and citizens. This contrasts with most prior theory that assumes that the actions of leaders alone determined modes of governance and political change (Ahlquist and Levi, 2011).

Collective Action Theory and Good Government

Levi's focus on collective action and revenue systems has provoked considerable interest among economists and political scientists who developed a research field termed the “New Fiscal Sociology” (Moore, 2004; Bräutigam et al., 2008; Martin et al., 2009; Yun-Casalilla and O'Brien, 2012; Martin and Prasad, 2014; Monson and Scheidel, 2015). Like the fiscal sociologists, we saw much potential in Levi's work, but we wanted to carry her Western-centered project across regions, time periods, and cultures. To realize this broadly comparative goal we operationalized the political scientists' notion of “good government” (or “quality of government”) (e.g., Levi, 2006; Ahlquist and Levi, 2011; Rothstein, 2011, 2014) to make it suitable for cross-culture coding, quantitative analysis, and hypothesis testing (Ember and Ember, 2001). One key advantage of the good government approach is that it provided us with a means to reassess the excessively simple equation between democracy and the expression of citizen voice through electoral politics. While the ideal of free, competitive elections and universal suffrage are centrally important criteria of democratic success today, they have been widely available only since the late nineteenth century at the earliest, and were rare in premodernity, while other features of good government were more common. Furthermore, as is evident from the present situation, voting does not alone ensure good government nor checks on concentrated power (Schedler, 2015).

To study good government, we asked: Did a state have the governing capacity and willingness to accommodate citizen voice in some way (analogous to elections) and to provide desired services such as public goods, a fair judiciary, and equitable taxation? Did effective institutions identify and punish those in positions of authority who benefit privately from the state's resources? Did the principal leadership accept limits on its power; for example, could they be impeached for violation of those limits? We converted the good government criteria into numerically codable variables, then aggregated them into scale measures: Public Goods, Bureaucratization (the state's ability to assess citizen voice and to exert controls over administrative processes and officials), Modes of Control over Governing Principals, and a Good Government Summary (Blanton and Fargher, 2008, 2009). We found that regimes scoring high on multiple good government measures were not common in human history, yet, it is important to note that even today such indicators are strongly expressed in a minority of nations. For example, surveys classify two-thirds of contemporary nation-states as only weakly democratic or autocratic (Mechkova et al., 2017), and Freedom House (2018) identifies 55% of nation-states as “not free or partly free.”

More precisely, when we compared our good government scores with a sample of thirty-one contemporary nations from the Global Integrity Report (https://www.globalintegrity.org) (whose coding system shares features with ours), we found a surprising degree of similarity. In our sample of premodern states, we found that, for the highest-scoring one-quarter of cases, the mean value of Modes of Control over Governing Principals is 83% of the possible total score, while the Bureaucratization score for the same group is 87% (the corresponding means for the lower 75% of cases are 48%, for control over principals and 59% for bureaucratization). The Global Integrity Report variable most similar to our control over principals variable (“Executive”) had a relatively high mean score for the upper quarter of the sample, at 71%, while the mean value for a variable that is similar to our Bureaucratization measure (combining their Public Requests, Election Integrity, Civil, and Law Enforcement) is 80% (for the lower 75% of cases, the mean scores are 51 and 59%, respectively). The methodologies of the two studies are not directly comparable, yet we suggest that their results point to the possibility that in key policies and practices of governing, modern and premodern are not two radically different political worlds.

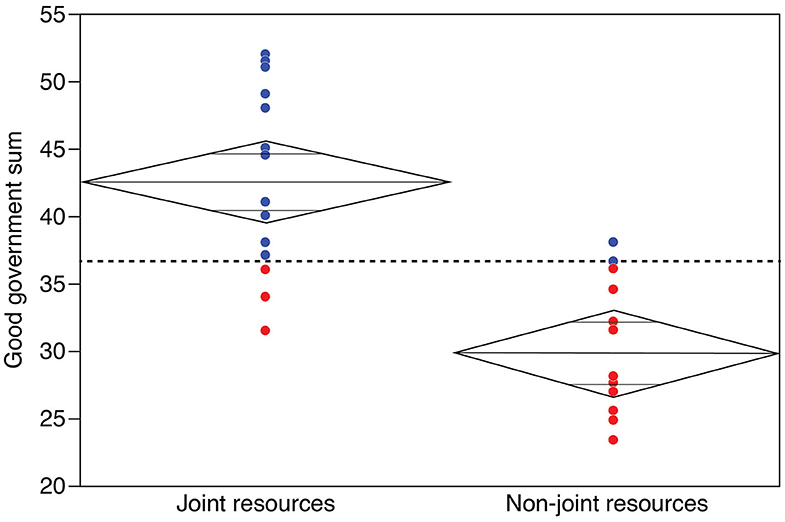

The Practical and Moral Foundations of Good Government

The historical experience of building good government, as we know from US history and from Early Modern England, entailed a lengthy and complex process of institution-building to overcome practical problems of building state capacity (e.g., Hindle, 2000) coupled with a deep commitment to establish a more equitable society and polity in the face of elite opposition (Rollison, 2010; e.g., Fatovic, 2015). Similarly, in our sample, state-builders implemented good government in the face of elite opposition and practical logistical problems, including strategies to provide public goods across the realm and to control official corruption (we describe four examples below). Given joint production, collective action theory predicts that, to maintain its power, the state's fiscal health, and taxpayer compliance, leadership will be compelled to demonstrate a willingness and ability to comply with moral claims directed at them and to make use of the state's resources for generally shared benefit. That fiscal economy had a profound impact on state-building is evident when we looked at the mean values of our Good Government Sum variable split by predominantly joint or non-joint fiscal economy (p = 0.0001, n = 30, using a two-tailed t-Test of difference of means) [(Blanton et al., in press); sources, codes and data to replicate are found in Blanton and Fargher (2008)] (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Good Government Summary by Resource Emphasis (primarily joint or primarily non-joint) (p = 0.0001, n = 30, using a two-tailed t-Test of difference of means). The width of the diamonds is proportionate to sub-sample size; the vertical points represent the 95% confidence intervals. Blue dots are higher than the grand mean, red dots lower.

The Endurance And Collapse Pattern of States With Good Government

Like modern democracies (e.g., Acemoglu et al., 2019), we found that premodern good government created a social environment that provided benefits to citizens (see also Blanton and Fargher, 2016, p. 245–281; Acemoglu and Robinson, 2019, p. 126–135). We found enhanced commercial development (using an ordinal measure with values up to 5, Kendall's tau b = 0.37, p = 0.0098, n = 29)(Blanton and Fargher, 2010), increased material standard of living and better food security and health outcomes across social sectors (although these are difficult to code quantitatively given the nature of premodern data), a tendency toward large population size (r = 0.46, p = 0.027 for population size of polity by Public Goods, n = 30) (Blanton and Fargher, 2016, p. 342) and population growth during the focal period (splitting Public Goods by evidence for growth or no growth, p = 0.05, two-tailed t-Test of difference of means, n = 15) (ibid.), and, as we point out below, in some cases religious and other aspects of individual freedom. We found another difference between polities featuring good government and the more authoritarian states in our sample. The latter featured more frequent social disruptions such as anti-tax rebellions, violent factional disputes, and succession crises (Kendall's tau b = −0.3035, p = 0.0389, n = 30) (Blanton, 2010).

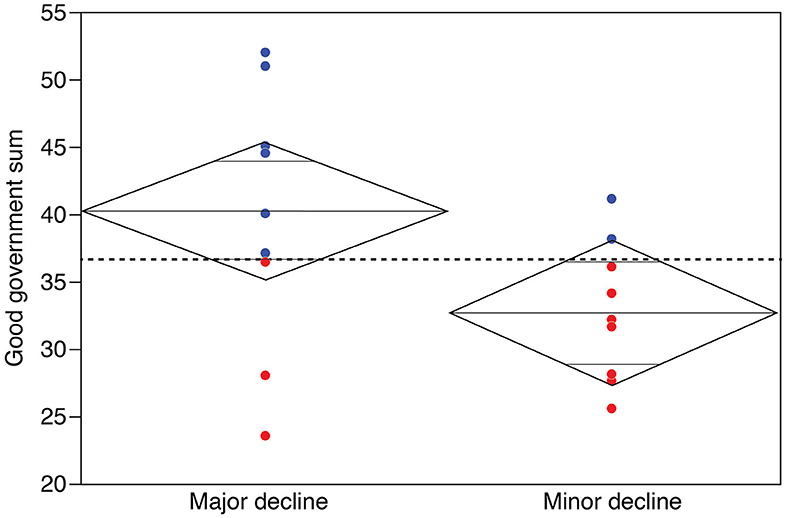

Given the benefits of good government, we might expect that states exhibiting it would have superior endurance. Yet, when we coded the period of processual continuity (during which the main features of a regime's policies remained largely intact), the mean value for the more authoritarian is 152.4 years (n = 14), vs. 166.1 years where there is evidence of good government (not a statistically significant difference). Although the period of continuity was similar, there is a remarkable difference in the aftermath of regime collapse. We noted three decline patterns across the 30-society sample: (1) political collapse was substantial and system-wide, and included significant demographic, economic, and agricultural decline (although not precluding eventual reconsolidation) (“Major” decline) (2) collapse is evident but was more patchy in character, so that some subregions or particular cities were affected more than others; and (3) only minor demographic, economic, and agricultural decline is evident in spite of regime collapse (“Minor Decline”).

Interestingly, decline of the more authoritarian states displayed a predominance of the minor collapse pattern, while the majority of states scoring higher on good government featured the major pattern (Figure 3) (the difference between major and minor, splitting the good government sum value is p = 0.04, two-tailed t-Test of difference means, n = 19). The variant decline patterns are not fully understood. However, below we identify what we perceive to be a possible initial causal factor—a moral failure of the top leadership, that is unique to the more collectively-organized states. Although we cannot fully explain why this kind of failure would necessarily precipitate a major collapse, we suggest that the difference between major and minor patterns is due to the considerably greater degree of social interaction and integration across boundaries of ethnicity, status, and religion in the states exhibiting enhanced good government policies. For example, interaction was enhanced by costly investments in transportation infrastructure and in efforts to improve the accessibility and navigability of cities (Blanton and Fargher, 2011). Urban and rural populations were also relatively highly connected through occupational specializations and market systems (Blanton and Fargher, 2010). Once a regime had collapsed, the threads of interconnectivity that had been fostered by the state were frayed, and fragmentation, localism, and conflict ensued.

Figure 3. Good government summary by decline pattern (p = 0.04, from a two-tailed t-Test of difference means, n = 19).

Causes of State Collapse: Insights From Four Premodern States

The initial causes of collapse may be difficult to discern because principal factors are not always obvious and pertinent data are not always available, although the causal factor archaeologists often focus attention on—human-caused environmental collapse (e.g., McAnany and Yoffee, 2010)—is not apparent. Military conquest brought a frequent end, but some of the histories point to cases where collapse was largely due to endogenous sociocultural factors. Most notably, we found that states organized around good government, with its implied expectation of mutual moral obligation, are exceptionally exposed to the risk of collapse when leadership turns away from the principles and practices that undergird citizen expectations. To illustrate the playing-out of this kind of collapse scenario, we provide brief historical summaries of four cases: Ming Dynasty, Mughal, the Roman High Empire, and the Republic of Venice. These four exemplified fiscal economies of largely joint production and are among the higher scoring polities in the sample for good government. Each of these polities was large, governed during episodes of broad economic prosperity, and endured for long periods. All were among the most prosperous premodern social formations, both in the worlds in which they were situated and historically across time. Yet, eventual moral lapses in the central leadership brought loss of citizen confidence, decline in fiscal health and government services, demographic decline, growing inability of the central authorities to control crime and administrative corruption, and the eventual rise of opposition movements and political polarization.

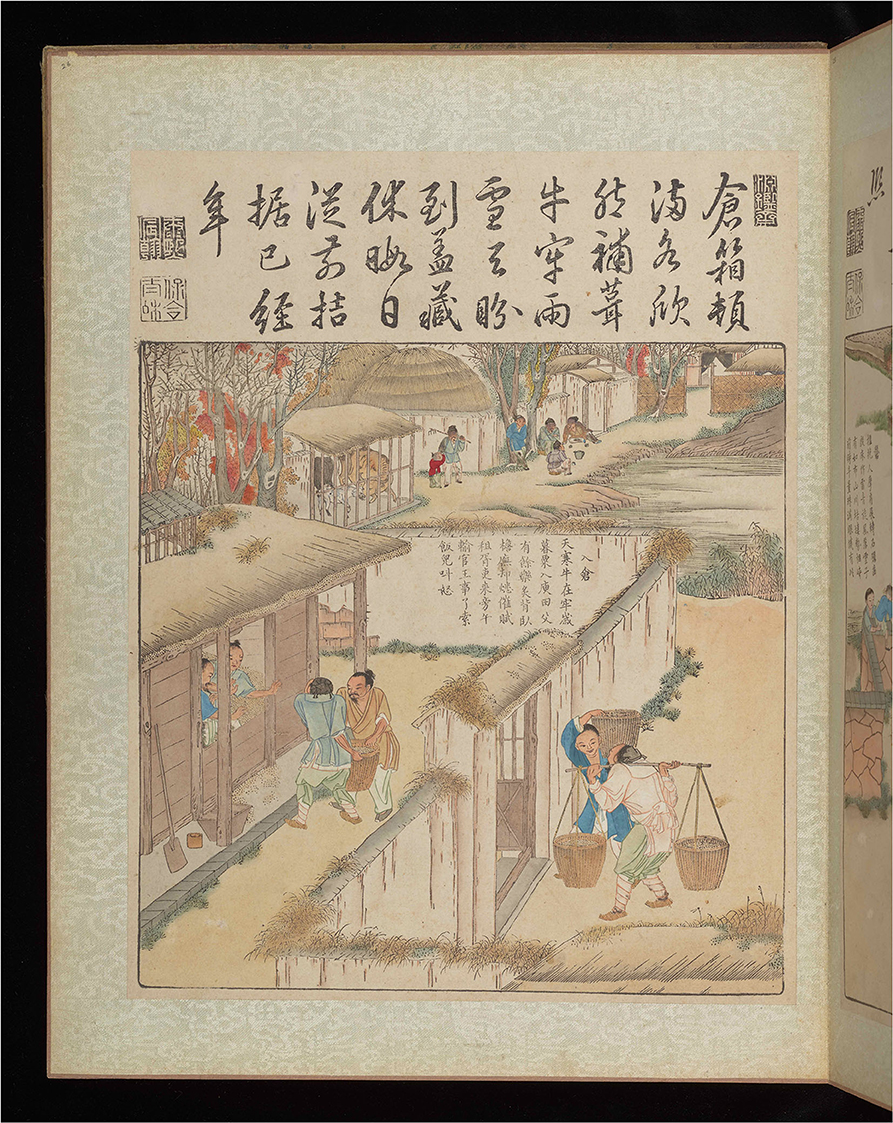

Ming Dynasty China [CE 1368-1644; major sources are Brook, 1998, 2005; Ho, 1962; Elvin, 1973; Chan, 1982; more sources for Ming and the other case studies are found in Blanton and Fargher, 2008]. Political reforms were put in place beginning in the late fourteenth century by the Ming Dynasty founder, the Hung-wu emperor. His program, based on a revival of Confucian philosophy (with its implied expectations for virtuous rulership), had the goal to enhance the state's ability to serve the general good of society. Perhaps owing to the emperor's peasant origins, one goal was to expand recruitment into civil and military administrations. To that end, the state built governing capacity to provide for examinations and funded thousands of schools to enhance the social capital of less wealthy exam-takers (Ho, 1962, p. 255; Schneewind, 2006). The dynasty is also recognized for its institutional capacity to field complaints from citizens about government functioning, to assure equitable taxation, and to monitor the actions of officials to root out and punish official corruption. Public goods included state-sponsored community granaries that buffered families against food shortages and overpricing by grain merchants (Figure 4). In addition to governing in conjunction with the civil administration, emperors were expected to serve as moral exemplars in society. They were prohibited from enriching themselves through commerce or other forms of profit making, and they were expected to set an example of frugality and lack of selfishness. Historians describe how the possibilities of political reform inspired the Hung-wu emperor and his immediate successors to work diligently to build and sustain good government policies.

Figure 4. Chinese village granary (CBL C 1717.1, p.26) ® The Trustees of the Chester Beatty Library, Dublin.

But the tradition of commitment to virtuous rulership and effective governance did not last very far beyond the beginning of the fifteenth century, by which time emperors were noted more often to show little interest in governing and to neglect their duties. For example, the Chia-ching emperor (1522–1566), in the words of Albert Chan (1982, p. 110), became so obsessed with Taoist ceremonies and alchemy he “had completely forgotten his obligations as a ruler.” That the leadership should provide a moral example was also forgotten by his successor, the Wan-li emperor (1567–1572), who departed from the expectations of frugality and lack of selfishness and instead became an avid seeker of personal wealth. To this end he made use of his eunuchs (devotees of the emperor who operated outside the usual administrative controls) to extract resources illegally, while he remained secluded in his palace, avoiding contact with officials in the civil administration who opposed his actions. This neglect of duty and moral failure eventuated in loss of confidence in the leadership and limited its ability to control excess taxation and official corruption among its administrative cadre. A decline in revenues and provision of public goods, such as flood management and crime control, soon followed. Rebellions, catastrophic decline of agrarian production and a growth in numbers of destitute people ensued. Lack of military preparedness along the northern border exposed the empire to invasion by the powerful Manchus, which brought on the dynasty's end in 1644.

Mughal (1556 CE-mid eighteenth century CE; main sources are Habib, 1963; Sarkar, 1963; Ali, 1985; Ziad, 2002). A religious ecumenism termed the “universal peace” was a key principle of Mughal state-building introduced by the notable state-builder Akbar, with the goal to enhance possibilities for public reasoning in a religiously pluralistic society. As the economist Sen (2005, p. 18) described it, “Akbar laid the foundations of secular legal structure and religious neutrality of the state, which included the duty to ensure that ‘no man be interfered with on account of religion, and anyone is allowed to go to a religion that pleases him.”' Although the Mughals were Muslims, Akbar and his immediate successors recruited Hindus and members of other religious groups into government service, while striving to maintain communication with religious leaders of all sorts. The universal peace was combined with other good government policies including the provision of governing capacity for equitable taxation, public goods, and control over administrative corruption. These policies and practices resulted in a phase of political unification across much of South Asia that lasted for a century.

Akbar's plan for state-building was maintained through two successor reigns, but the fourth emperor, Aurangzeb, beginning around the 1650s, came under the influence of Muslim leaders. They convinced him to abandon the universal peace and to foreground Islam as the central religion of the empire. In doing so he antagonized the empire's substantial Hindu population (for example, by taxing Hindus more than Muslims and by approving the destruction of new temples), which in turn discredited the central authorities, initiating a period of political, social, and demographic decline and growing corruption. Revolts, plummeting agrarian production, and population decline soon followed. By the mid-eighteenth century, the empire was militarily unable to respond to inroads made by the English East India Company.

Rome (late first century BCE-192 CE; main sources include Abbott, 1963; Millar, 1977; MacMullen, 1988; Birley, 2000) Beginning in the last century BCE, Julius Caesar and Augustus emerged as leaders in the contentious Late Republican Period, introducing governmental reforms and infrastructure investments that resulted in an unprecedented increase in material standard of living across social sectors and imperial territories for the next 200 years (for example, some 85,000 kilometers of roads were built connecting Rome to the provinces). Caesar made the Senate's proceedings more transparent, instituted administrative controls over provincial governments to limit corruption, and mandated a form of community government that assured both citizen representation and accountable leadership at the local level. Augustus followed up on reform programs by offering more urban public goods such as improved water supplies and fire and police departments, the latter in Rome staffed by an estimated 10,000 trained professionals.

The example set by Julius Caesar and Augustus provided a template for the behavior of subsequent rulers, one that justified rule by showing devotion to the duties of governing, displaying obedience to the needs of the people, and living moderately. The code of virtuous rulership was adopted by imperial successor Vespasian and most of his successors, over a span of two centuries, through Marcus Aurelius (for example, Marcus, following the example of the highly regarded Hadrian, canceled all debt due the treasury in CE 178). The death of Marcus in 180 occurred at a crucial time when the empire faced serious challenges—including fiscal shortages, problems with soldier recruitment at a time of military peril, and a rebellion—requiring astute and devoted leadership. However, his successor Commodus failed to provide either. He showed little interest in governing, instead finding his true calling as a performer in the arena as a gladiator (eventually identifying himself as Hercules), and in so doing, as A. R. Birley (2000:194) put it, “destroying a consensus” that had endured for many years. Having alienated many through his ineptitude and corruption, Commodus was assassinated in 193. Following his death, the empire descended into a period of crisis for more than a century; for example, between 235 and 260, 51 individuals claimed the title of Roman emperor. Corrupt practices such as the selling of official positions became the new normal. According to the historian MacMullen (1988, p. 169), during this century, in the absence of exemplary leadership and administrative capacity, corruption pervaded the empire and, given the pervasive striving for personal financial gain, “relationships involving anything other than the wish for material possession had no chance to develop.”

Venetian Republic (CE Twelfth to fourteenth centuries to 1797; main sources for Venice are Pullan, 1968; Lane, 1973; Norwich, 1982; Romano, 1987; Chambers and Pullan, 2001; Horodowich, 2008; de Maria, 2010). As early as the Twelfth to fourteenth centuries, in the context of a growing Afro-Eurasian trade, Venice emerged as a key commercial entrepot. With expanded economic influence and great wealth, the Venetian governing elite, consisting of a council of prominent families (the Great Council), introduced political reforms that to some degree reflected their high regard for Roman institutions of municipal government, but also their recognition of the importance of social cohesion for the success of the society. Three key principles guided the state-building program. One was the goal to create a society that would function as a religiously neutral moral community able to transcend the inherent potential for conflict in a socially and culturally diverse populace. For example, while Catholicism was predominant, the state's official policy was religious neutrality, reflecting the fact that the population included immigrants and that Venetians traded with persons with diverse cultural and religious beliefs. Some governing policies reflected a deep fear of revolutionary autocratic overthrow that would destroy the Republic, a well-founded fear as there were three attempts at revolution during the fourteenth century. The other key principle was a strongly inscribed belief that individual wealth is likely to have a negative influence on the political process. The desire for great wealth, it was thought, brings political corruption that can threaten community solidarity.

Driven by these central ideas, a form of government was put into place capable of addressing citizen concerns while exacting controls over the actions of judicial and other governing officials. For example, the actions of the chief administrative officer, the Doge, were carefully monitored and violations, including incompetence or corruption, were grounds for removal from office through a well-established impeachment process. Further, given the requirement of religious neutrality and to defend against unwanted foreign influence, the Doge and family members were forbidden to have any official connection with the Papacy, and they were prohibited from engaging in commercial activities. The state also provided public goods, far more than any other European state of the period, including transportation infrastructure and water control, maintenance of public order, food security, public street lighting, a public health office, poor relief, and public education. By the 1400s, owing to its stability, good government, and great wealth, Venice was widely regarded as “the most splendid state in Europe” (Norwich, 1982, p. 342).

Venice was able to maintain its moral code and good government practices far longer than the Ming, Mughal, and Roman examples, perhaps in part because it had an effective impeachment process, which was exercised on several occasions. Most of the key reforms were put into place during the twelfth to fourteenth centuries and were sustained successfully until about 1600, at which time there was a gradual decline in commitment to key principles and a hardening of the divide between wealthy and poor. Even then, although it gradually weakened, the republic was not officially dissolved until its governing council surrendered to Napoleon Bonaparte in 1797. From the sixteenth through the eighteenth centuries Venice faced many challenges, internal and external. At times its devotion to religious neutrality invited conflict with a strident papacy that was battling the Reformation. Venice also faced increased military pressure from the Ottoman empire at the same time it struggled to maintain its neutrality in the context of an increasingly war-like seventeenth century Europe, all of this at a time when economic decline made it difficult to maintain military preparedness, as much of the Venetian economy was lost when trading shifted away from the Mediterranean and toward the Atlantic.

There is evidence that the Venetian social compact and moral code were beginning to fray under pressure, with negative outcomes, including military setbacks, food crises, and a wave of epidemics beginning in the 1630s. Actions taken by the Doge, his family, and a governing council (“the Ten”) in the 1620s provide evidence of a growing social divide. Even though for centuries the Doges had been carefully vetted and virtually all had demonstrated a lifetime of service to the Republic, these criteria were ignored in the selection at that time of Giovanni Corner, scion of a wealthy family, as Doge. Soon after he was elected, his sons were found to have engaged in non-allowed businesses and one accepted an appointment as Bishop of Bergamo, a direct violation of the religious neutrality law. Although in the past such actions would have resulted in impeachment, little was done to bring the family to justice, even though a relative of Corner had made an assassination attempt against a critic of the Doge. The weak response of the Ten provoked dismay among Venetian citizens who suspected them of having been corrupted or unwilling to act against a sitting Doge who shared their elite status. Shortly after this incident, in spite of negative public sentiment, the Great Council of the city changed rules to give the Ten even more powers, a move that, as the historian John Norwich put it (1982, p. 538), “was a sad day for Venice, since the Ten was encouraged to behave in ever more dictatorial fashion, to consider itself ever more immune from outside control and—not least important—to make itself ever more unpopular both with the citizens as a whole and with other organs of government.”

Discussion

What can we learn from these episodes of good government and collapse? Although the three monarchies (Ming, Mughal, and High Roman Empire) lacked elections and possibilities for impeachment, they illustrate a moral bond between citizen and leadership that is inherent where there is joint production. Moral failure of the leadership in this social setting brings calamity because the state's lifeblood—its citizen-produced resource-base—is threatened when there is loss of confidence in the state, which brings in its wake social division, strife, flight, and a reduced motivation to comply with tax obligations. In the resulting weakened fiscal economy, services that citizens have come to depend on fail, including public goods and administrative control of corruption. By contrast, in the case of a more authoritarian regime, moral collapse of the leadership is not as serious an economic problem, neither for the leadership, whose chief resources are not significantly citizen-provided, nor for citizens, who have little motivation to comply anyway, and who benefitted little from public goods or other government services.

The case of Venice is more troublesome in light of some political processes we see in contemporary democracies. Most notably, although they were not elected by the general population, the constitutional system of Venice extended strict control over the actions of elected Doges, who were carefully vetted, and for which an established impeachment process was in place. Even this venerated, successful, and centuries-long system, under the weight of economic decline, was ignored when the Ten failed to impeach a sitting Doge who had, and whose family had, clearly violated rules. This event was followed by the passage of new rules by the Great Council that gave the central authorities more dictatorial powers over society. Thus, the state officials themselves brought on what its founders had always feared: an autocratic overthrow of the Republic.

We suggest that the histories of four premodern societies stand as a reminder that to sustain a political system, past and present, has always been a challenging and fragile project (cf. Miller, 2018). To realize and sustain good government is especially difficult owing in large part to the importance of shared moral obligations between citizens and the state, whether eloquently written down like the US Constitution, or not. Good government, past or present, is premised on checks on power, a distribution of voice, ways to police corruption, equitable fiscal financing of the state, limits on greed, and leadership dedicated to public service. For the Ming, the Mughal, the Romans, and Venetian states, what began in exuberant phases of intense state-building effort intended to construct more just and functional systems of good government, ended when the leadership inexplicably undermined those earlier goals, core values, and practices. As a result, the societal threads of effective cooperation and security were torn, and once prosperous nations and empires were exposed to the duel threats of invasion and decline.

Modern democracies such as the US were similarly conceived in the context of an exuberant push to build a just society, but today that impetus and commitment to that shared socioeconomic compact appears to be fading (Sitaraman, 2017; Andersen, 2020). Levitsky and Ziblatt (2018, p. 212) argue that today politicians often ignore the once important values of mutual tolerance and institutional forbearance. In the US, bipartisan support for public goods has been weakening since the 1960s (Whitman, 2017; Kleinenberg, 2018; Reich, 2018). Surveys on values point to decline in belief in democratic ideals and institutions (Howe, 2017). Citizen confidence in the state has been rocked repeatedly by a sequence of incompetent, unpopular, and damaging actions by the principal leadership, including the Vietnam war, Watergate, the economically destructive outcomes of the 2008 economic crisis, the inability to effectively manage the coronavirus pandemic, and now the divisive response by the White House to the Black Lives Matter movement.

Many citizens perceive that they have little stake in what should be a democratic society. The work of Gilens and Page (2014) confirmed this sensibility. Given the growing influence of wealthy individuals and interest groups on public policy, they doubt whether the US even has a majoritarian electoral democracy. Decline in citizen confidence is compounded by a great economic transition in the US, a U-turn over the last five decades in wealth and income inequalities. The more progressive tax policies of the mid-twentieth century have been jettisoned while the Supreme Court has allowed billionaires and corporations to flood elections with cash. At the same time, access to public goods at the heart of social mobility, such as reasonably priced access to high-quality university education, has been cut. These economic shifts are undergirded by a new ethos and practices that enshrine shareholder value, personal freedom, nepotism, cronyism, the comingling of state and personal resources, and narcissistic aggrandizement in ways rarely seen in the early history of our Republic. If we are to avoid the fates of the premodern governments we described, a reaffirmation of the core moral values and institutions at the heart of the nation is urgently needed.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Funding

Principal funding for the cross-cultural comparison has been provided by the National Science Foundation of the United States (0204536-BCS and 0809643-BCS) and the Center for Behavioral and Social Sciences, Purdue University.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the useful comments by three external reviewers that helped us refine our argument.

Footnotes

1. ^Collective action theory addresses what Bates (1988) termed the “supply problem”- how to identify conditions in which a state's leadership would be motivated to supply costly administrative systems and to accept limits on their own agency.

2. ^Prior theories argue that premodern states were mired in low-productivity technologically simple forms of agrarian production and limited commercialization that inhibited the development of modern bureaucratic forms of the state (e.g., Ardant, 1975; Acemoglu et al., 2005; Kiser and Karceski, 2017). Collective action theory sees productivity more in terms of state-building strategies and taxpayer motivation rather than fixed technologies or inelastic commercial development (Blanton and Fargher, 2016: 245-282).

References

Abbott, F. F. (1963). A History and Description of Roman Political Institutions, 3rd. Edn. New York, NY: Biblo and Tannen.

Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S., and Robinson, J. (2005). The rise of europe: atlantic trade, institutional change, and economic growth. Am. Econ. Rev. 95, 546–579. doi: 10.1257/0002828054201305

Acemoglu, D., Naidu, S., Restrepo, P., and Robinson, J. A. (2019). Democracy does cause growth. J. Public Economy 127, 47–100. doi: 10.1086/700936

Acemoglu, D., and Robinson, J. A. (2019). The Narrow Corridor: States, Societies, and the Fate of Liberty. New York, NY: Penguin.

Ahlquist, J. S., and Levi, M. (2011). Leadership: what it means, what it does, and what we want to know about it. Annual Rev. Political Sci. 14, 1–24. doi: 10.1146/annurev-polisci-042409-152654

Ali, M. A. (1985). The Apparatus of Empire: Awards of Ranks, Offices, and Titles to the Mughal Nobility (1574-1658). Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Ardant, G. (1975). Financial policy and economic infrastructure of modern states and nations. In: The Formation of National States in Western Europe, ed. Charles Tilly (Princeton: Princeton University Press), 164–242.

Bates, R. H. (1988). Contra contractarianism: some reflections on the new institutionalism. Politics Soc. 16, 387–401. doi: 10.1177/003232928801600207

Birley, A. R. (2000). “Hadrian to the Antonines,” in The Cambridge Ancient History, 22nd Edn, Vol. 11: The High Empire, A. D. 70 to 192, ed. A. K. Bowman, P. Garnsey, and D. Rathbone (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 132–194. doi: 10.1017/CHOL9780521263351.004

Blanton, R. E. (2010). Collective action and adaptive socioecological cycles in premodern states. Cross-Cultural Res. 44, 41–59. doi: 10.1177/1069397109351684

Blanton, R. E. (2019). Review of James Scott, Against the Grain: A Deep History of the Earliest States, New Haven: Yale University Press. Rev. Politics 81, 516–518. doi: 10.1017/S0034670519000068

Blanton, R. E., and Fargher, L. F. (2008). Collective Action in the Formation of Premodern States. New York, NY: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-73877-2

Blanton, R. E., and Fargher, L. F. (2009). Collective action in the evolution of pre-modern states. Soc. Evol. History 8, 133–166.

Blanton, R. E., and Fargher, L. F. (2010). Evaluating Causal Factors in Market Development in Premodern States: A Comparative Study, with Critical Comments on the History of Ideas About Markets,” in Archaeological Approaches to Market Exchange in Ancient Societies, eds C. P. Garraty and B. L. Stark (Boulder, CO: University Press of Colorado), 207–226.

Blanton, R. E., and Fargher, L. F. (2011). The collective logic of pre-modern cities. World Archaeol. 43, 505–522. doi: 10.1080/00438243.2011.607722

Blanton, R. E., and Fargher, L. F. (2016). How Humans Cooperate: Confronting the Challenges of Collective Action. Boulder, CO: University Press of Colorado.

Blanton, R. E., Fargher, L. F., Feinman, G. M., and Kowalewski, S. A. (in press). The fiscal economy of good government: past present. Curr. Anthropol.

Blanton, R. E., Feinman, G. M., Kowalewski, S. A., and Nicholas, L. M. (1999). Ancient Oaxaca: The Monte Albán State. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511607844

Blanton, R. E., Feinman, G. M., Kowalewski, S. A., and Peregrine, P. N. (1996). A dual-processual theory for the evolution of mesoamerican civilization. Curr. Anthropol. 37, 65–68. doi: 10.1086/204471

Bräutigam, D., Fjeldstad, O., and Moore, M., (eds.). (2008). Taxation and State-Building in Developing Countries: Capacity and Consent. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511490897

Brook, T. (1998). The Confusions of Pleasure: Commerce and Culture in Ming China. Berkeley: The University of California Press. doi: 10.1525/9780520924079

Carballo, D. M., and Feinman, G. M. (2016). Cooperation, collective action, and the archaeology of large-scale societies. Evolut. Anthropol. 26, 288–296. doi: 10.1002/evan.21506

Chambers, D. S., and Pullan, B. (2001). Venice: A Documentary History, 1450-1630. Toronto: Toronto University Press

de Maria, B. (2010). Becoming Venetian: Immigrants and Arts in Early Modern Venice. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Fargher, L. F., and Heredia Espinoza, V. Y., (eds.). (2016). Alternate Pathways to Complexity. Boulder, CO: University Press of Colorado.

Fargher, L. F., Heredia Espinoza, V. Y., and Blanton, R. E. (2011). Alternative pathways to power in late postclassic highland mesoamerica. J. Anthropol. Archaeol. 30, 306–326. doi: 10.1016/j.jaa.2011.06.001

Fatovic, C. (2015). America's Founding and the Struggle over Economic Inequality. Lawrence: University of Kansas Press.

Feinman, G. M. (2013). The Emergence of Social Complexity: Why More than Population Size Matters. In: Cooperation and Collective Action: Archaeological Perspectives, ed. D. M. Carballo (Boulder: University Press of Colorado), 35–56.

Feinman, G. M., and Carballo, D. M. (2018). Collaborative and competitive strategies in the variability and resiliency of large-scale societies in mesoamerica. Economic Anthropol. 5, 7–19. doi: 10.1002/sea2.12098

Freedom House (2018). Freedom in the World: Democracy in Crisis. Available online at: https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/freedom-world-2018 (accessed 05, 2020).

Gilens, M., and Page, B. I. (2014). Testing theories of american politics: elites, interest groups, and average citizens. Perspect. Politics 12, 564–581. doi: 10.1017/S1537592714001595

Hindle, S. (2000). The State and Social Change in Early Modern England: c. 1550-1640. New York, NY: Palgrave.

Ho, P. (1962). The Ladder of Success in Imperial China: Aspects of Social Mobility, 1368-1911. New York, NY: Columbia University Press. doi: 10.7312/ho−93690

Horodowich, E. (2008). Language and Statecraft in Early Modern Venice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Howe, P. (2017). Eroding norms and democratic deconsolidation. J. Democracy 28, 15–29. doi: 10.1353/jod.2017.0061

Kiser, E., and Karceski, S. M. (2017). Political Economy of Taxation. Annual Rev. Political Sci. 20, 75–92. doi: 10.1146/annurev-polisci-052615-025442

Kleinenberg, E. (2018). Palaces for the People: How to Build a More Equal and United Society. New York, NY: Broadway Books.

Levi, M. (2006). Why We Need a New Theory of Government. Perspect. Polit/ 4, 5–19. doi: 10.1017/S1537592706060038

Martin, I. W., Mehrota, A. K., and Prasad, M., (eds.). (2009). The New Fiscal Sociology: Taxation in Comparative and Historical Perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Martin, I. W., and Prasad, M. (2014). Taxes and fiscal sociology. Annual Rev. Sociol. 40, 331–345. doi: 10.1146/annurev-soc-071913-043229

Mayshar, J., Moav, O., and Neeman, Z. (2017). Geography, transparency, and institutions. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 111, 622–636. doi: 10.1017/S0003055417000132

McAnany, P., and Yoffee, N., (eds.). (2010). Questioning Collapse: Human Resilience, Ecological Vulnerability, and the Aftermath of Empire. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mechkova, V., Lührmann, A., and Lindberg, S. I. (2017). How much democratic backsliding? J. Democracy 28, 162–169. doi: 10.1353/jod.2017.0075

Millar, F. (1977). The Emperor in the Roman World (31 BC-AD 337). Ithaca: Cornell University Press. doi: 10.2307/1087113

Miller, J. (2018). Can Democracy Work? A Short History of a Radical Idea, from Ancient Athens to Our World. New York, NY: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux.

Monson, A., and Scheidel, W., (eds) (2015). Fiscal Regimes and the Political Economy of Premodern States. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Moore, M. (2004). Revenues, state formation, and the quality of governance in developing countries. Int. Political Sci. Rev. 25, 297–319. doi: 10.1177/0192512104043018

North, D. C., Wallis, J. J., and Weingast, B. R. (2009). Violence and Social Orders: A Conceptual Framework for Interpreting Recorded Human History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511575839

Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511807763

Pullan, B., (ed). (1968). Crisis and Change in the Venetian Economy in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries. London: Metheun and Co.

Robbins, B., and Kiser, E. (2018). Legitimate authorities and rational taxpayers: an investigation of voluntary compliance and method effects in a survey experiment of income tax evasion. Rational. Soc. 30, 247–301. doi: 10.1177/1043463118759671

Rollison, D. (2010). A Commonwealth of the People: Popular Politics and England's Long Social Revolution, 1066-1649. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511807541

Romano, D. (1987). Patricians and Popolani: The Social Foundations of the Venetian Renaissance State. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press.

Rothstein, B. (2011). The Quality of Government: Corruption, Social Trust, and Inequality in International Perspective. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Rothstein, B. (2014). “Good Governance,” in: The Oxford Handbook of Governance, ed. D. Levi-Faur (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 143–154.

Schedler, A. (2015). “Electoral Authoritarianism,” in Emerging Trends in the Social and Behavioral Sciences, eds R. Scott and S. Kosslyn. doi: 10.1002/9781118900772.etrds0098

Schneewind, S. (2006). Community Schools and the State in Ming China. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Schumpeter, J. A. (1991 [1918]). “The crisis of the tax state,: in J. Schumpeter: The Economics and Sociology of Capitalism, ed R. Swedberg (Princeton: Princeton University Press), 99–140.

Scott, J. C. (2017). Against the Grain: A Deep History of the Earliest States. New Haven: CT; London: Yale University Press.

Sen, A. (2005). The Argumentative Indian: Writings on Indian History, Culture, and Identity. New York, NY: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux.

Sitaraman, G. (2017). The Crisis of the Middle-Class Constitution: Why Economic Inequality Threatens Our Republic. New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf.

Stasavage, D. (2020). The Decline and Rise of Democracy. Princeton: Princeton University Press. doi: 10.2307/j.ctvss3zz6

Thurston, T. L. (2010). “Bitter Arrows and Generous Gifts: What Was a ‘King' in the European Iron Age?,” in Pathways to Power: New Perspectives on the Emergence of Social Inequality, eds T. D. Price and G. M. Feinman (New York, NY: Springer), 193–254. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-6300-0_8

Tilly, C. (1985). “War making and state making as organized crime,” in Bringing the State Back In, eds P. B. Evans, D. Rueschemeyer, and T. Skocpol (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 169–191. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511628283.008

Waldner, D., and Lust, E. (2018). Unwelcome change: coming to terms with democratic backsliding. Annual Rev. Political Sci. 21, 5.1–5.21. doi: 10.1146/annurev-polisci-050517-114628

Whitman, M. V. N. (2017). Bipartisan Support of Public Goods Made America Great. Atlantic Monthly CityLab.

Yun-Casalilla, B., and O'Brien, P. K., (eds.). (2012). The Rise of Fiscal States: A Global History, 1500-1914. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781139004237

Keywords: premodern states, state growth and failure, collective action theory, good government, fiscal economy, moral collapse, comparative research, new fiscal sociology

Citation: Blanton RE, Feinman GM, Kowalewski SA and Fargher LF (2020) Moral Collapse and State Failure: A View From the Past. Front. Polit. Sci. 2:568704. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2020.568704

Received: 12 June 2020; Accepted: 04 September 2020;

Published: 16 October 2020.

Edited by:

Anna Herranz-Surrallés, Maastricht University, NetherlandsReviewed by:

Israel Solorio, National Autonomous University of Mexico, MexicoAntoaneta L. Dimitrova, Leiden University, Netherlands

Copyright © 2020 Blanton, Feinman, Kowalewski and Fargher. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Richard E. Blanton, YmxhbnRvbnJAcHVyZHVlLmVkdQ==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Richard E. Blanton

Richard E. Blanton Gary M. Feinman

Gary M. Feinman Stephen A. Kowalewski

Stephen A. Kowalewski Lane F. Fargher4†

Lane F. Fargher4†