94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

OPINION article

Front. Plant Sci., 26 March 2025

Sec. Plant Abiotic Stress

Volume 16 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2025.1550190

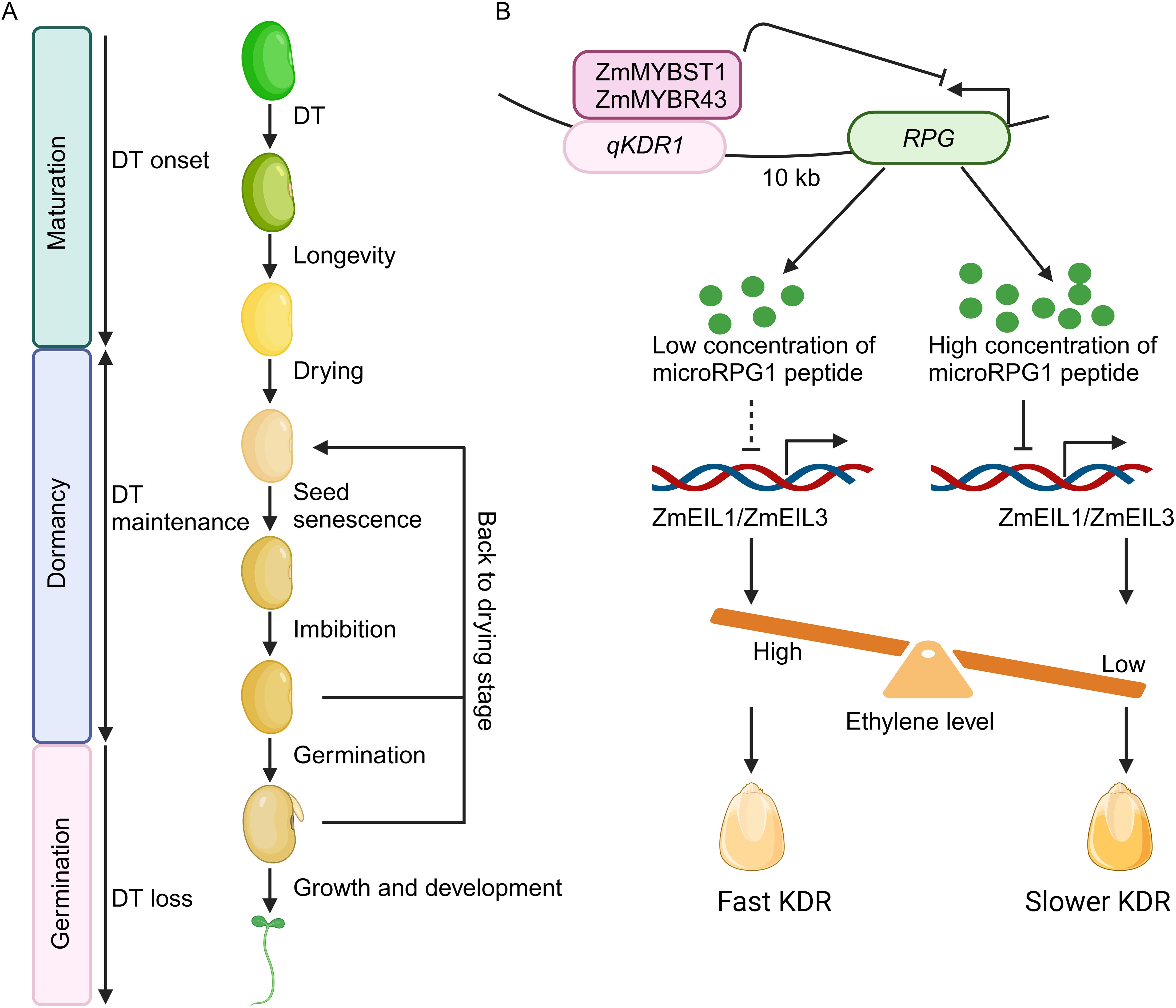

Seeds serve as the major means of reproduction for most plant species and form the foundation of both agriculture and natural ecosystems (Waterworth et al., 2024). Seeds are also the key genetic resources to deal with the increasing human population and climate fluctuations (Leprince et al., 2017). Seed development can be categorized into three major stages: maturation, dormancy, and germination (Figure 1A; Zinsmeister et al., 2020; Powell, 2022; Nadarajan et al., 2023; Waterworth et al., 2024). In the maturation phase, seeds acquire desiccation tolerance, followed by developmental processes that expands longevity to dormancy stage. Maturation drying reduces seed moisture content to 5% – 15% of fresh weight (Figure 1A; Zinsmeister et al., 2020). Dormancy of seeds under optimal conditions, such as low temperature and humidity, prolongs viability, while suboptimal conditions lead to seed aging (Figure 1A; Powell, 2022; Nadarajan et al., 2023). Seed dormancy is modulated by a complex interplay of genetic, biochemical, and molecular determinants intricately connected to environmental signals such as light, temperature, nitrate availability, and phytohormones including abscisic acid (ABA) and gibberellin (GA) (Chahtane et al., 2017; Matilla, 2024; Rachappanavar, 2025). The difference between dormant seeds and non-dormant seeds could be attributed to a number of gene expression changes (Meimoun et al., 2014), physiological, developmental, and morphological features of the grains on the spike, including pericarp color, transparency, hairiness, waxiness, permeability of water, α-amylase activity, and concentrations of growth regulators such as ABA and GA within the embryo (Sohn et al., 2021). Seed germination is initiated by water uptake (imbibition), resulting in activation of multiple cellular actions, and is completed with the emergence of the young roots and shoots (Figure 1A; Carrera-Castaño et al., 2020; Waterworth et al., 2024).

Figure 1. The microRPG1 peptide modulates seed desiccation through ethylene signaling pathways. (A) Key developmental phases in seed life. The establishment of desiccation tolerance (DT) occurs during the late maturation phase, subsequently followed by developmental processes that promote longevity during the dormancy period. Maturation drying leads to a reduction in seed moisture levels. DT is maintained by intricate networks during dormancy. Optimal conditions of low temperature and humidity prolong seed viability, whereas less favorable environmental conditions contribute to seed senescence. Water imbibition triggers metabolic activities and cellular processes, culminating in germination. Cutting-edge technologies rehydrate seeds, followed by desiccation, to enhance cellular repair and boost seed vigor. DT is lost when seeds progress to germination. (B) Mechanistic model of microRPG1 peptide in seed desiccation. RPG encodes a peptide, namely microRPG1, comprising 31 amino acids. Two MYB transcription factors, ZmMYBSt1 and ZmMYBR43, interact with the qKDR1 locus, thereby repressing the transcriptional activity of RPG and the levels of microRPG1 peptide. The microRPG1 peptide subsequently regulates the expression of ZmEIL1 and ZmEIL3, pivotal transcription factors in the ethylene signaling cascade, thereby modulating ethylene signaling and KDR. Elevated ethylene concentrations facilitate KDR, while reduced ethylene levels deaccelerate KDR. The figure is adapted from Yu et al., 2024. Dashed line means weak effect. The figure is created via biorender.com.

The acquisition of desiccation tolerance at the late seed maturation stage provides a critical survival mechanism for crops, enabling them to adaptive to adverse environmental conditions such as extreme temperatures and drought (Leprince et al., 2017; Zinsmeister et al., 2020; Waterworth et al., 2024). The majority of crop plants can generate seeds classified as orthodox seeds, which possess the ability to withstand drying to low moisture content (below 7%) and harsh extreme environmental conditions such as freezing (-10°C) for a long time (Nadarajan et al., 2023; Waterworth et al., 2024). In maize, the moisture content of kernel suitable for mechanized harvesting is from 15% - 25%, however, in some regions such as China, maize varieties have high grain water content at harvest, ranging from 30% - 40% (Xiang et al., 2012; Kebebe et al., 2015; Dai et al., 2017; Li et al., 2018a, 2018b; Zhou et al., 2018). Kernel dehydration rate (KDR), defined as the rate of moisture loss between two adjacent periods after pollination (Zhang et al., 2024), is a critical determinant of maize seed quality and exerts a significant impact on the efficiency of mechanical harvesting (Li et al., 2018b). Besides, the removal of free water leads to a phase transition as the cytoplasm reduces mobility from a fluid to glassy state (Buitink and Leprince, 2008), resulting in metabolic quiescence and increased seed longevity (Zinsmeister et al., 2020). To date, genetic elements implicated in the modulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) signaling, lipid peroxidation at the cell membrane, the preservation of DNA and RNA integrity, DNA methylation status, biosynthesis of seed storage proteins (SSPs), and phytohormones such as ABA, auxin, GA, and brassinosteroids (BRs) have been documented as crucial regulators of seed longevity (Nadarajan et al., 2023; Pirredda et al., 2023; Waterworth et al., 2024). Abiotic factors including light, thermal conditions, drought and salinity stress also significantly impact seed longevity, with temperature and water availability emerging as predominant factors (Zinsmeister et al., 2020). In maize, several quantitative trait loci (QTLs) have been characterized as pivotal players in the regulation of KDR (Li et al., 2020, 2021a; Zhang et al., 2023; Jin et al., 2024). Collectively, a higher level of desiccation tolerance is crucial for maize mechanized harvesting, preventing grain breakage, mildew, and reducing the costs associated with harvest and storage (de Jager et al., 2004; Xiang et al., 2012; Kebebe et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2022; Xia et al., 2024). Thus, a comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms governing desiccation tolerance of seeds is necessary and crucial.

Seed dehydration is linked to a multitude of physiological modifications, including the accumulation of macromolecules (proteins, lipids, and carbohydrates), enhanced membrane integrity, and activation of cellular dehydration defense mechanisms, which are governed by hormone signaling pathways such as abscisic acid (ABA) and ethylene (Angelovici et al., 2010; Bewley et al., 2013; Kijak and Ratajczak, 2020; Oliver et al., 2020; Smolikova et al., 2020). The onset of desiccation tolerance occurs when seeds enter into dormancy stage at the late maturation stage (Leprince et al., 2017; Smolikova et al., 2020). Numerous signaling components including Late Embryogenesis Abundant (LEA) proteins, small heat shock proteins (sHSPs), non-reducing oligosaccharides, antioxidants, reactive oxygen species (ROS), as well as gibberellin (GA), and ABA, have been identified as crucial regulators of seed desiccation tolerance (Angelovici et al., 2010; Kijak and Ratajczak, 2020; Smolikova et al., 2020; Waterworth et al., 2024). In addition, many transcription factors such as ABA-INSENSITIVE 3 (ABI3), FUSCA 3 (FUS3) and LEAFY COTYLEDONS 2 (LEC2) have been discovered to defines the balance between GA and ABA to finally initiate the onset of seed desiccation tolerance (Smolikova et al., 2020). However, the regulatory mechanisms of seed desiccation tolerance mediated by the small signaling peptides remain largely elusive.

Micropeptides, also referred to as microproteins or short open reading frame (sORF)-encoded peptides, are essential products derived from a larger polypeptide or from MicroRNAs (miRNAs), long non-coding RNA (lncRNA), and circular RNA (circRNA), typically characterized by an arbitrary length of less than 100 - 150 amino acids (Hashimoto et al., 2008; Makarewich and Olson, 2017; Sousa and Farkas, 2018; Vitorino et al., 2021; Pan et al., 2022; Sruthi et al., 2022; Bhar and Roy, 2023; Gautam et al., 2023). A growing number of evidence show the key roles of micropeptides in various plant developmental and adaptive processes including but not limited to plant growth (Sharma et al., 2020; Erokhina et al., 2021; Badola et al., 2022), adventitious root formation (Chen et al., 2020), nodule formation (Couzigou et al., 2016), cold response (Chen et al., 2022), anthocyanin biosynthesis (Vale et al., 2024), and responses to cadmium and arsenic stressors (Kumar et al., 2023; Lu et al., 2024), and immunity (Zhou et al., 2022). Recently, the microRPG1 (micropeptide of RPG ORF1) peptide that governs kernel dehydration rate (KDR) in maize has been identified, offering novel perspectives on the molecular mechanisms that regulate seed desiccation mediated by micropeptide and providing valuable insights for future genetic breeding of cereal crops (Figure 1B; Lyu, 2024; Yu et al., 2024).

Maize (Zea mays) is one of the most important crops world-wide, with an annual global production of over 1147 million tons (Yang and Yan, 2021). Mechanized harvesting of maize kernels is a viable solution to reduce labor costs and to enhance production efficiency. However, mechanized harvesting has not yet been achieved in China due to the absence of appropriate corn cultivars (Li et al., 2018a; Wang et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2020). Mechanized harvesting of maize requires a sufficiently low moisture content of kernels (15% - 25%) (Liu et al., 2020). This poses a significant challenge as the majority of corn cultivars in China exhibit a high grain moisture content during harvest, usually between 30% and 40% (Dai et al., 2017; Li et al., 2018a; Zhou et al., 2018). Consequently, enhancing KDR and minimizing kernel moisture content at the harvest stage are critical and has become a major aim of modern maize breeding (Sala et al., 2006; Qu et al., 2022). To this end, a prominent quantitative trait locus (QTL) for KDR, designated as Kernel Dehydration Rate 1 (qKDR1), has been identified within the corn recombinant inbred line population, which originated from the crossbreeding of corn inbred lines K22 and DAN340, known for their variant KDRs (Pan et al., 2016; Xiao et al., 2016; Yu et al., 2024).

qKDR1 is located on chromosome 1, specifically within a 1417 base pair (bp) intergenic non-coding region of the maize genome (Yu et al., 2024). Targeted deletion of this sequence via CRISPR-Cas9 at this locus yields varying KDRs, demonstrating that the 1417-bp segment of qKDR1 is crucial for KDR variability, as its knockout leads to impaired KDR. To investigate the regulatory mechanism of qKDR1 on KDR, transient transcriptional activity assays were conducted in maize protoplasts. The findings reveal that qKDR1 functions as a silencer, with the 369-bp segment of qKDR1 identified as the major repressive element. Subsequent RNA-sequencing analysis is performed to ascertain potential targets of qKDR1, leading to the identification of the target gene, qKDR1 Regulated Peptide Gene (RPG). RPG is situated 10 kilobases upstream of qKDR1 and exhibits high expression levels in maize kernels, and its transcriptional activity declines during the later stages of kernel maturation. In maize lines where qKDR1 has been knocked out, RPG expression is markedly elevated. Collectively, these results indicate that qKDR1 acts as a repressor of RPG expression. Furthermore, analysis of public chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-seq) datasets has uncovered two MYB-related transcription factors, ZmMYBST1 and ZmMYBR43, that bind to the qKDR1 locus. Both ZmMYBST1 and ZmMYBR43 exhibit expression patterns that similar to RPG, and they also inhibit RPG transcriptional activity. Additionally, CRISPR-Cas9-generated double mutants of ZmMYBST1 and ZmMYBR43 demonstrate a reduced rate of KDR. These findings suggest that ZmMYBST1 and ZmMYBR43 interact with the qKDR1 region to downregulate RPG expression, thereby modulating KDR.

Ribosome profiling sequencing (Ribo-seq) reveals that mRNA of RPG is ribosome bound in three open reading frames, ORF1, ORF2, and ORF3. Mutations in ORF1 accelerated KDR, whereas mutations in the two other ORFs has no obvious effect on KDR. Overexpressing ORF1 resulted in a decelerated KDR. Furthermore, the kernel moisture content of ORF1 knockout lines is decreased under different environments. The endogenous ORF1 micropeptide is also verified by immunoprecipitation (IP) and mass spectrometry (MS). These findings indicate that ORF1 encodes the functional RPG micropeptide (microRPG1). Furthermore, ZmEIL1 and ZmEIL3, key players in ethylene signaling, are identified as the downstream targets of microRPG1 peptide via RNA-seq assay. ZmEIL1 and ZmEIL3 are upregulated in the microRPG1 knockout and downregulated in the overexpression lines, respectively. Consistently, ZmEIL1 and ZmEIL3 knockout lines also exhibit decelerated KDR. In contrast, application of ethylene facilitates KDR rate. Hence, microRPG1peptide represses ethylene signaling, which further decelerates kernel dehydration (Figure 1B).

Although the essential function of the microRPG1 peptide in the modulation of desiccation tolerance of seed has been established in both maize and Arabidopsis (Yu et al., 2024), the precise molecular mechanisms warrant further exploration. First, the binding affinities and sites of ZmMYBST1 and ZmMYBR43 to qKDR1 remain to be elucidated. Secondly, the mechanism by which qKDR1 inhibits RPG expression, potentially through the native promoter of RPG, requires further investigation. It has been proposed that microRPG1 is localized at the plasma membrane, nucleus, and cytoplasm, indicating that unidentified receptors may exist and could potentially recognize the microRPG1 peptide, thereby initiating cellular signaling cascades, including ethylene signaling in the nucleus and cytoplasm to finely regulate desiccation tolerance. The advanced CRISPR screening platform provides a powerful methodology for generating single or multiple mutations of receptor-like kinases (RLKs) simultaneously (Gaillochet et al., 2021), which will facilitate the identification of uncharacterized receptors that can recognize microRPG1 signal to modulate maize KDR. Furthermore, it is plausible that the microRPG1 peptide exerts its effects independently of any specific receptors. Additionally, the interactions between the microRPG1 peptide and other phytohormones such as ABA and GA, which are implicated in the regulation of seed desiccation tolerance (Kijak and Ratajczak, 2020; Smolikova et al., 2020), necessitate further scrutiny. Importantly, single-cell transcriptomic assays have facilitated the identification of novel regulators involved in seed development (Liew et al., 2024; Yao et al., 2024), a technique that could potentially unveil the regulators of seed desiccation tolerance at a single-cell resolution and establish the unprecedented transcriptional networks mediated by microRPG1 peptide that govern seed desiccation tolerance. Notably, seeds develop desiccation tolerance during the maturation phase and sustain this tolerance during the dormancy phase (Figure 1A). A critical question that remains unresolved is how maize initiates the transcription and biosynthesis of the microRPG1 peptide. Furthermore, the mechanisms by which the microRPG1 peptide interacts with both known and yet-to-be-identified factors involved in seed desiccation tolerance require elucidation (Smolikova et al., 2020; Farrant et al., 2022; Waterworth et al., 2024).

Despite the fact that the microRPG1 peptide is exclusively found in the genera Zea (Yu et al., 2024), it is plausible that other yet-to-be-identified small signaling peptides may also influence desiccation tolerance. Desiccation tolerance is established during seed maturation on the maternal plant through an array of programmed cellular mechanisms (Waterworth et al., 2024), suggesting that small signaling peptides involved in the dehydration process, such as CLAVATA3/EMBRYO SURROUNDING REGION 9 (CLE9) (Zhang et al., 2019) and CLE25/26 (Takahashi et al., 2018; Endo and Fukuda, 2024), C-TERMINALLY ENCODED PEPTIDE 5 (CEP5) (Smith et al., 2020), and RAPID ALKALINIZATION FACTOR (RALF) (Jing et al., 2024), along with other drought-responsive small signaling peptides (Xie et al., 2022; Ji et al., in press; Zhang et al., 2025), could also potentially modulate seed desiccation tolerance, but this requires further examinations. Additionally, the mass spectrometry imaging (MSI) technique has been employed in in plants to elucidate the spatial distribution of structurally diverse plant hormones (Chen et al., 2024) and various other plant compounds (García-Rojas et al., 2024; Yin et al., 2024; Zou et al., 2025) even at the single-cell resolution (Croslow et al., 2024; Zhang et al., 2024). This technique has been successfully performed to identify small peptides mammalian cells (David et al., 2018; Bottomley et al., 2024). Thus, MSI could be instrumental in discovering novel small signaling peptides associated with desiccation tolerance during the late maturation phase of seeds, thereby enhancing the existing knowledge of the mechanisms underlying seed dehydration (Figure 1A). In addition to the microRPG1 peptide, multiple miPEPs have been discovered in various crop and horticultural species (Ji et al., in press); however, their biological roles remain largely uncharacterized. The CRISPR-Cas system can facilitate the generation of miPEP knockout mutants (Li et al., 2021b), and to identify potential receptors (Gaillochet et al., 2021). Moreover, CRISPR-mediated gene regulation tools, such as CRISPR interference (CRISPRi), CRISPR activation (CRISPRa), CRISPRoff, CROP-seq, CRISP-seq, CRISPR-based epigenetic modifications, and Perturb-seq (Liu et al., 2022), coupled with single-cell transcriptomics (Liew et al., 2024; Yao et al., 2024), can be utilized to elucidate the influence of miPEPs on growth, agronomic and horticultural traits, and stress response mechanisms at single cell resolution. These tools also enable the construction of novel transcriptional networks modulated by miPEP peptides.

In summary, the discovery of microRPG1 peptide contributes to understanding seed desiccation and to the improvement of corn seeds to adapt to mechanized harvesting. According to Worldostats (https:://worldostats.com/corn-maize-production-by-country-2025/) and FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations) (Liu et al., 2025), the global production of corn is a staggering 1.16 billion tones per year. The top 3 leading maize producing countries are the USA (348.8 million tons), China (277.2 million tons) and Brazil (109.4 million tons), accounting for over half of global maize production. The application of microRPG1 peptide would lower the moisture content of maize, and prevent grain breakage, mildew, reduce labor costs and increase maize production worldwide for food supplement in future. In addition, it is possible to introduce the RPG gene in to other cereal crops such as rice, wheat and millet artificially or application of exogenous microRPG1 peptide to manipulate the moisture content of seeds, which is beneficial for storage and mechanized harvesting in future. Identifying the uncharacterized signaling components and novel small signaling peptides involved in seed desiccation would provide a new genetic toolbox for the genetic enhancement of cereal crops and broaden the applications of small signaling peptides in modern agriculture.

RL: Writing – original draft. ZZ: Writing – original draft. SH: Writing – original draft. HX: Writing – original draft. HH: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work is supported by funding from Jiangxi Agricultural University (9232308314), Science and Technology Department of Jiangxi Province (20223BCJ25037) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (32460081) to HH.

We would like to thank the lab members, the reviewers and editor for their constructive comments. We apologize to those whose great work we are unable to include due to limited space.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declare that Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Chat-GPT was used to improve the readability

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Angelovici, R., Galili, G., Fernie, A. R., Fait, A. (2010). Seed desiccation: a bridge between maturation and germination. Trends Plant Sci. 15, 211–218. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2010.01.003

Badola, P. K., Sharma, A., Gautam, H., Trivedi, P. K. (2022). MicroRNA858a, its encoded peptide, and phytosulfokine regulate Arabidopsis growth and development. Plant Physiol. 189, 1397–1415. doi: 10.1093/plphys/kiac138

Bewley, J. D., Bradford, K. J., Hilhorst, H. W. M., Nonogaki, H. (2013). Seeds: Physiology of development, germination and dormancy. 3rd ed (New York, NY, USA: Springer).

Bhar, A., Roy, A. (2023). Emphasizing the role of long non-coding RNAs (lncRNA), circular RNA (circRNA), and micropeptides (miPs) in plant biotic stress tolerance. Plants 12, 3951. doi: 10.3390/plants12233951

Bottomley, H., Phillips, J., Hart, P. (2024). Improved detection of tryptic Peptides from tissue sections using desorption electrospray ionization mass spectrometry imaging. J. Am. Soc Mass. Spectrom. 35, 922–934. doi: 10.1021/jasms.4c00006

Buitink, J., Leprince, O. (2008). Intracellular glasses and seed survival in the dry state. C R Biol. 331, 788–795. doi: 10.1016/j.crvi.2008.08.002

Carrera-Castaño, G., Calleja-Cabrera, J., Pernas, M., Gómez, L., Oñate-Sánchez, L. (2020). An Updated overview on the regulation of seed germination. Plants 9, 703. doi: 10.3390/plants9060703

Chahtane, H., Kim, W., Lopez-Molina, L. (2017). Primary seed dormancy: a temporally multilayered riddle waiting to be unlocked. J. Exp. Bot. 68, 857–869. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erw377

Chen, L., Zhang, Y., Bu, Y., Zhou, J., Man, Y., Wu, X., et al. (2024). Imaging the spatial distribution of structurally diverse plant hormones. J. Exp. Bot. 75, 6980–6997. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erae384

Chen, Q. J., Deng, B. H., Gao, J., Zhao, Z. Y., Chen, Z. L., Song, S. R., et al. (2020). A miRNA-encoded small peptide, vvi-miPEP171d1, regulates adventitious root formation. Plant Physiol. 183, 656–670. doi: 10.1104/pp.20.00197

Chen, Q. J., Zhang, L. P., Song, S. R., Wang, L., Xu, W. P., Zhang, C. X., et al. (2022). vvi-miPEP172b and vvi-miPEP3635b increase cold tolerance of grapevine by regulating the corresponding MIRNA genes. Plant Sci. 325, 111450. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2022.111450

Chen, Q. J., Zhang, L. P., Song, S. R., Wang, L., Xu, W. P., Zhang, C. X., et al. (2022). vvi-miPEP172b and vvi-miPEP3635b increase cold tolerance of grapevine by regulating the corresponding MIRNA genes. Plant Sci. 325, 111450. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2022.111450

Couzigou, J. M., André, O., Guillotin, B., Alexandre, M., Combier, J. P. (2016). Use of microRNA-encoded peptidemiPEP172c to stimulate nodulation in soybean. New Phytol. 211, 379–381. doi: 10.1111/nph.13991

Croslow, S. W., Trinklein, T. J., Sweedler, J. V. (2024). Advances in multimodal mass spectrometry for single-cell analysis and imaging enhancement. FEBS Lett. 598, 591–601. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.14798

Dai, L., Wu, L., Dong, Q., Zhang, Z., Wu, N., Song, Y., et al. (2017). Genome-wide association study of field grain drying rate after physiological maturity based on a resequencing approach in elite maize germplasm. Euphytica. 213, 182. doi: 10.1007/s10681-017-1970-9

David, B. P., Dubrovskyi, O., Speltz, T. E., Wolff, J. J., Frasor, J., Sanchez, L. M., et al. (2018). Using tumor explants for imaging mass spectrometry visualization of unlabeled peptides and small molecules. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 9, 768–772. doi: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.8b00091

de Jager, B., Roux, C. Z., Kühn, H. C. (2004). An evaluation of two collections of South African maize (Zea mays L.) germ plasm: 2. The genetic basis of dry-down rate. South Afr. J. Plant Soil 21, 120–122. doi: 10.1080/02571862.2004.10635035

Endo, S., Fukuda, H. (2024). A cell-wall-modifying gene-dependent CLE26 peptide signaling confers drought resistance in Arabidopsis. PNAS Nexus 3, pgae049. doi: 10.1093/pnasnexus/pgae049

Erokhina, T. N., Ryazantsev, D. Y., Samokhvalova, L. V., Mozhaev, A. A., Orsa, A. N., Zavriev, S. K., et al. (2021). Activity of chemically synthesized peptide encoded by the miR156A precursor and conserved in the Brassicaceae family Plants. Biochemistry 86, 551–562. doi: 10.1134/S0006297921050047

Farrant, J.M., Hilhorst, H.. (2022) Crops for dry environments. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 74, 84–91. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2021.10.026.

Gaillochet, C., Develtere, W., Jacobs, T. B. (2021). CRISPR screens in plants: approaches, guidelines, and future prospects. Plant Cell 33, 794–813. doi: 10.1093/plcell/koab099

García-Rojas, N. S., Sierra-Álvarez, C. D., Ramos-Aboites, H. E., Moreno-Pedraza, A., Winkler, R. (2024). Identification of plant compounds with mass spectrometry imaging (MSI). Metabolites 14, 419. doi: 10.3390/metabo14080419

Gautam, H., Sharma, A., Trivedi, P. K. (2023). Plant microPro-teins and miPEPs: small molecules with much bigger roles. Plant Sci. 326, 111519. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2022.111519

Hashimoto, Y., Kondo, T., Kageyama, Y. (2008). Lilliputians get into the limelight: novel class of small peptide genes in morphogenesis. Dev. Growth Differ. 50, S269–S276. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-169X.2008.00994.x

Ji, C., Li, H., Zhang, Z., Peng, S., Liu, J., Zhou, Y., et al. (2025). The power of small signaling peptides in crop and horticultural plants. Crop J. in press. doi: 10.1016/j.cj.2024.12.020

Jin, X., Zhang, X., Wang, P., Liu, J., Zhang, H., Wu, X., et al. (2024). QTL mapping and omics analysis to identify genes controlling kernel dehydration in maize. Theor. Appl. Genet. 137, 233. doi: 10.1007/s00122-024-04715-9

Jing, X. Q., Shi, P. T., Zhang, R., Zhou, M. R., Shalmani, A., Wang, G. F., et al. (2024). Rice kinase OsMRLK63 contributes to drought tolerance by regulating reactive oxygen species production. Plant Physiol. 194, 2679–2696. doi: 10.1093/plphys/kiad684

Kebebe, A. Z., Reid, L. M., Zhu, X., Wu, J., Woldemariam, T., Voloaca, C., et al. (2015). Relationship between kernel drydown rate and resistance to Gibberella ear rot in maize. Euphytica 201, 79–88. doi: 10.1007/s10681-014-1185-2

Kijak, H., Ratajczak, E. (2020). What do we know about the genetic basis of seed desiccation tolerance and longevity? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 3612. doi: 10.3390/ijms21103612

Kumar, R. S., Sinha, H., Datta, T., Asif, M. H., Trivedi, P. K. (2023). microRNA408 and its encoded peptide regulate sulfur assimilation and arsenic stress response in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 192, 837–856. doi: 10.1093/plphys/kiad033

Leprince, O., Pellizzaro, A., Berriri, S., Buitink, J. (2017). Late seed maturation: drying without dying. J. Exp. Bot. 68, 827–841. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erw363

Li, Y., Li, W., Li, J. (2021b). The CRISPR/Cas9 revolution continues: From base editing to prime editing in plant science. J. Genet. Genomics 48, 661–670. doi: 10.1016/j.jgg.2021.05.001

Li, S. K., Wang, K. R., Xie, R. Z., Ming, B. (2018a). Grain mechanical harvesting technology promotes the transformation of maize production mode. Sci. Agric. Sin. 51, 1842–1844. doi: 10.3864/j.issn.0578-1752.2018.10.003

Li, L. L., Xue, J., Xie, R. Z., Wang, K. R., Ming, B., Hou, P., et al. (2018b). Effects of grain moisture content on mechanical grain harvesting quality of summer maize. Acta Agron. Sin. 44, 1747–1754. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1006.2018.01747

Li, S., Zhang, C., Lu, M., Yang, D., Qian, Y., Yue, Y., et al. (2020). QTL mapping and GWAS for field kernel water content and kernel dehydration rate before physiological maturity in maize. Sci. Rep. 10, 13114. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-69890-3

Li, S., Zhang, C., Yang, D., Lu, M., Qian, Y., Jin, F., et al. (2021a). Detection of QTNs for kernel moisture concentration and kernel dehydration rate before physiological maturity in maize using multi-locus GWAS. Sci. Rep. 11, 1764. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-80391-1

Liew, L. C., You, Y., Auroux, L., Oliva, M., Peirats-Llobet, M., Ng, S., et al. (2024). Establishment of single-cell transcriptional states during seed germination. Nat. Plants 10, 1418–1434. doi: 10.1038/s41477-024-01771-3

Liu, G., Lin, Q., Jin, S., Gao, C. (2022). The CRISPR-Cas toolbox and gene editing technologies. Mol. Cell 82, 333–347. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2021.12.002

Liu, H. J., Liu, J., Zhai, Z., Dai, M., Tian, F., Wu, Y., et al. (2025). Maize2035: A decadal vision for intelligent maize breeding. Mol. Plant 18, 313–332. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2025.01.012

Liu, J., Yu, H., Liu, Y., Deng, S., Liu, Q., Liu, B., et al. (2020). Genetic dissection of grain water content and dehydration rate related to mechanical harvest in maize. BMC Plant Biol. 20, 118. doi: 10.1186/s12870-020-2302-0

Lu, L., Chen, X., Chen, J., Zhang, Z., Zhang, Z., Sun, Y., et al. (2024). MicroRNA-encoded regulatory peptides modulate cadmium tolerance and accumulation in rice. Plant Cell Environ. 47, 1452–1470. doi: 10.1111/pce.14819

Makarewich, C. A., Olson, E. N. (2017). Mining for micropeptides. Trends Cell Biol. 27, 685–696. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2017.04.006

Matilla, A. J. (2024). Current insights into weak seed dormancy and pre-harvest sprouting in crop species. Plants 13, 2559. doi: 10.3390/plants13182559

Meimoun, P., Mordret, E., Langlade, N. B., Balzergue, S., Arribat, S., Bailly, C., et al. (2014). Is gene transcription involved in seed dry after-ripening? PLoS One 9, e86442. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0086442

Nadarajan, J., Walters, C., Pritchard, H. W., Ballesteros, D., Colville, L. (2023). Seed longevity-the evolution of knowledge and a conceptual framework. Plants 12, 471. doi: 10.3390/plants12030471

Oliver, M. J., Farrant, J. M., Hilhorst, H. W. M., Mundree, S., Williams, B., Bewley, J. D. (2020). Desiccation tolerance: avoiding cellular damage during drying and rehydratio. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 71, 435–460. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-071219-105542

Pan, Q., Li, L., Yang, X., Tong, H., Xu, S., Li, Z., et al. (2016). Genome-wide recombination dynamics are associated with phenotypic variation in maize. New Phytol. 210, 1083–1094. doi: 10.1111/nph.2016.210.issue-3

Pan, J., Wang, R., Shang, F., Ma, R., Rong, Y., Zhang, Y. (2022). Functional micropeptides encoded by long non-coding RNAs: A comprehensive review. Front. Mol. Biosci. 9, 817517. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2022.817517

Pirredda, M., Fañanás-Pueyo, I., Oñate-Sánchez, L., Mira, S. (2023). Seed longevity and ageing: a review on physiological and genetic factors with an emphasis on hormonal regulation. Plants 13, 41. doi: 10.3390/plants13010041

Powell, A. (2022). Seed vigour in the 21st century. Seed Sci. Technol. 50, 45–73. doi: 10.15258/sst.2022.50.1.s.04

Qu, J., Zhong, Y., Ding, L., Liu, X., Xu, S., Guo, D., et al. (2022). Biosynthesis, structure and functionality of starch granules in maize inbred lines with different kernel dehydration rate. Food Chem. 368, 130796. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.130796

Rachappanavar, V. (2025). Utilizing CRISPR-based genetic modification for precise control of seed dormancy: progress, obstacles, and potential directions. Mol. Biol. Rep. 52, 204. doi: 10.1007/s11033-025-10285-w

Sala, R. G., Andrade, F. H., Camadro, E. L., Cerono, J. C. (2006). Quantitative trait loci for grain moisture at harvest and field grain drying rate in maize (Zea mays L.). Theor. Appl. Genet. 112, 462–471. doi: 10.1007/s00122-005-0146-5

Sharma, A., Badola, P. K., Bhatia, C., Sharma, D., Trivedi, P. K. (2020). Primary transcript of miR858 encodes regulatory peptide and controls flavonoid biosynthesis and development in Arabidopsis. Nat. Plants 6, 1262–1274. doi: 10.1038/s41477-020-00769-x

Smith, S., Zhu, S., Joos, L., Roberts, I., Nikonorova, N., Vu, L. D., et al. (2020). The CEP5 peptide promotes abiotic stress tolerance, as revealed by quantitative proteomics, and attenuates the AUX/IAA equilibrium in Arabidopsis. Mol. Cell Proteomics 19, 1248–1262. doi: 10.1074/mcp.RA119.001826

Smolikova, G., Leonova, T., Vashurina, N., Frolov, A., Medvedev, S. (2020). Desiccation tolerance as the basis of long-term seed viability. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 101. doi: 10.3390/ijms22010101

Sohn, S. I., Pandian, S., Kumar, T. S., Zoclanclounon, Y. A. B., Muthuramalingam, P., Shilpha, J., et al. (2021). Seed Dormancy and pre-harvest sprouting in rice-an updated overview. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 11804. doi: 10.3390/ijms222111804

Sousa, M. E., Farkas, M. H. (2018). Micropeptide. PLoS Genet. 14, e1007764. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007764

Sruthi, K. B., Menon, A., P, A., Vasudevan Soniya, E. (2022). Pervasive translation of small open reading frames in plant long non-coding RNAs. Front. Plant Sci. 13, 975938. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.975938

Takahashi, F., Suzuki, T., Osakabe, Y., Betsuyaku, S., Kondo, Y., Dohmae, N., et al. (2018). A small peptide modulates stomatal control via abscisic acid in long-distance signalling. Nature 556, 235–238. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0009-2

Vale, M., Badim, H., Gerós, H., Conde, A. (2024). Non-mature miRNA-encoded micropeptide miPEP166c stimulates anthocyanin and proanthocyanidin synthesis in Grape Berry Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25, 1539. doi: 10.3390/ijms25031539

Vitorino, R., Guedes, S., Amado, F., Santos, M., Akimitsu, N. (2021). The role of micropeptides in biology. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 78, 3285–3298. doi: 10.1007/s00018-020-03740-3

Wang, W., Ren, Z., Li, L., Du, Y., Zhou, Y., Zhang, M., et al. (2022). Meta-QTL analysis explores the key genes, especially hormone related genes, involved in the regulation of grain water content and grain dehydration rate in maize. BMC Plant Biol. 22, 346. doi: 10.1186/s12870-022-03738-y

Wang, C., Shu, Z., Cheng, B., Jiang, H., Li, X. (2018). Advances and perspectives in maize mechanized harvesting in China. J. Anhui Agric. Univ. 45, 551–555.

Waterworth, W., Balobaid, A., West, C. (2024). Seed longevity and genome damage. Biosci. Rep. 44, BSR20230809. doi: 10.1042/BSR20230809

Xia, Y., Shen, A., Che, T., Liu, W., Kang, J., Tang, W. (2024). Early detection of surface mildew in maize kernels using machine vision coupled with improved YOLOv5 deep learning model. Appl. Sci. 14, 10489. doi: 10.3390/app142210489

Xiang, K., Reid, L. M., Zhang, Z. M., Zhu, X. Y., Pan, G. T. (2012). Characterization of correlation between grain moisture and ear rot resistance in maize by QTL meta-analysis. Euphytica 183, 185–195. doi: 10.1007/s10681-011-0440-z

Xiao, Y., Tong, H., Yang, X., Xu, S., Pan, Q., Qiao, F., et al. (2016). Genome-wide dissection of the maize ear genetic architecture using multiple populations. New Phytol. 210, 1095–1106. doi: 10.1111/nph.2016.210.issue-3

Xie, H., Zhao, W., Li, W., Zhang, Y., Hajný, J., Han, H. (2022). Small signaling peptides mediate plant adaptions to abiotic environmental stress. Planta 255, 72. doi: 10.1007/s00425-022-03859-6

Yang, N., Yan, J. (2021). New genomic approaches for enhancing maize genetic improvement. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 60, 101977. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2020.11.002

Yao, J., Chu, Q., Guo, X., Shao, W., Shang, N., Luo, K., et al. (2024). Spatiotemporal transcriptomic landscape of rice embryonic cells during seed germination. Dev. Cell 59, 2320–2332.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2024.05.016

Yin, Z., Huang, W., Li, K., Fernie, A. R., Yan, S. (2024). Advances in mass spectrometry imaging for plant metabolomics-Expanding the analytical toolbox. Plant J. 119, 2168–2180. doi: 10.1111/tpj.v119.5

Yu, Y., Li, W., Liu, Y., Liu, Y., Zhang, Q., Ouyang, Y., et al. (2024). A Zea genus-specific micropeptide controls kernel dehydration in maize. Cell. 188, 44–59.e21. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2024.10.030

Zhang, Z., Han, H., Zhao, J., Liu, Z., Deng, L., Wu, L., et al. (2025). Peptide hormones in plants. Mol. Hortic. 5, 7. doi: 10.1186/s43897-024-00134-y

Zhang, H., Lu, K. H., Ebbini, M., Huang, P., Lu, H., Li, L. (2024). Mass spectrometry imaging for spatially resolved multi-omics molecular mapping. NPJ Imaging 2, 20. doi: 10.1038/s44303-024-00025-3

Zhang, L., Shi, X., Zhang, Y., Wang, J., Yang, J., Ishida, T., et al. (2019). CLE9 peptide-induced stomatal closure is mediated by abscisic acid, hydrogen peroxide, and nitric oxide in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Environ. 42, 1033–1044. doi: 10.1111/pce.13475

Zhang, Y., Zhang, X., Zhu, L., Wang, L., Zhang, H., Zhang, X., et al. (2023). Identification of the maize LEA Gene family and Its relationship with kernel dehydration. Plants 12, 3674. doi: 10.3390/plants12213674

Zhou, G., Hao, D., Xue, L., Chen, G., Lu, H., Zhang, Z., et al. (2018). Genome-wide association study of kernel moisture content at harvest stage in maize. Breed. Sci. 68, 622–628. doi: 10.1270/jsbbs.18102

Zhou, H., Lou, F., Bai, J., Sun, Y., Cai, W., Sun, L., et al. (2022). A peptide encoded by pri-miRNA-31 represses autoimmunity by promoting Treg differentiation. EMBO Rep. 23, e53475. doi: 10.15252/embr.202153475

Zinsmeister, J., Leprince, O., Buitink, J. (2020). Molecular and environmental factors regulating seed longevity. Biochem. J. 477, 305–323. doi: 10.1042/BCJ20190165

Keywords: microRPG1, kernel dehydration rate, ethylene, mechanized harvesting, maize

Citation: Lu R, Zhang Z, Hu S, Xia H and Han H (2025) A micropeptide regulates seed desiccation. Front. Plant Sci. 16:1550190. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2025.1550190

Received: 23 December 2024; Accepted: 10 March 2025;

Published: 26 March 2025.

Edited by:

Raveendran Muthurajan, Tamil Nadu Agricultural University, IndiaReviewed by:

Rajanbabu Venugopal, Tamil Nadu Agricultural University, IndiaCopyright © 2025 Lu, Zhang, Hu, Xia and Han. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Huibin Han, aHVpYmluaGFuQGp4YXUuZWR1LmNu

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.