95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Plant Sci. , 29 January 2025

Sec. Plant Abiotic Stress

Volume 16 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2025.1458467

This article is part of the Research Topic Essence of Survival: Impact of Primary and Secondary Metabolism on Plant Acclimation to Abiotic Stress View all 5 articles

Hao Chen1†

Hao Chen1† Jiale Wan1†

Jiale Wan1† Jiali Zhu1

Jiali Zhu1 Ziyi Wang1

Ziyi Wang1 Caiyao Mao1

Caiyao Mao1 Wanjing Xu1

Wanjing Xu1 Juan Yang1

Juan Yang1 Yijuan Kong1

Yijuan Kong1 Xiaofei Zan1

Xiaofei Zan1 Rongjun Chen1

Rongjun Chen1 Jianqing Zhu1

Jianqing Zhu1 Zhengjun Xu1

Zhengjun Xu1 Lihua Li1,2*

Lihua Li1,2*Excessive salt accumuln in soil is one of the most important abiotic stresses in agricultural environments. The Domain of Unknown Function 868 (DUF868) family, comprising 15 members in rice, has been identified in the protein family database. In this study, we cloned and functionally characterized OsDUF868.12, a member of the OsDUF868 family, to elucidate its role in rice response to salt stress. A series of experiments, including RT-qPCR, Agrobacterium-mediated transient transformation in tobacco for localization analysis, phenotypic characterization, physiological and biochemical index measurement, and leaf staining, were conducted to investigate the function of OsDUF868.12 under salt stress. Transcriptional analysis revealed that OsDUF868.12 exhibited the most significant response to low temperature and salt stress. Preliminary subcellular localization studies indicated that OsDUF868.12 is localized in the cell membrane. Phenotypic Identification Experiments showed Overexpression lines of OsDUF868.12 enhanced resistance to salt stress and increased survival rates, while knockout lines of OsDUF868.12 were opposite. Physiological and biochemical assessments, along with leaf staining, demonstrated that overexpression of OsDUF868.12 improved the activity against oxidative stress.under salt stress. Furthermore, overexpression of OsDUF868.12 elevated the transcription levels of positively regulated salt stress-related genes. These findings suggest that overexpression of OsDUF868.12 enhances rice tolerance to salt stress at the molecular level through a series of regulatory mechanisms. This study provides valuable insights into the functional roles of the DUF868 family in plant responses to abiotic stress.

Rice is one of the main food crops in the world (Khan et al., 2021). According to the forecast of the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the world population will reach 9 billion in 2050, which requires a further increase in global food production. In recent years, climate change has intensified, and extreme weather has occurred frequently, the impact of abiotic stresses on plants has become more serious (Fedoroff et al., 2010). Soil salinization will become one of the main factors affecting agricultural production in the coming decades.

Excessive salt accumulation in soil is one of the most important abiotic stresses in agricultural environments (Munns, 2002). Plants growing in saline-alkali soil will suffer from ion toxicity, oxidative damage and osmotic stress (Munns and Tester, 2008), which will significantly inhibit the vegetative growth, seed germination, yield and quality of rice (Quan et al., 2007). Improving the salt tolerance of rice can not only improve the yield and quality of rice, but also solve the problem of reducing the cultivated land area to a certain extent (Yang et al., 2023). Plants have evolved a variety of strategies to cope with salt stress, including ion homeostasis regulatory pathways, antioxidant system activation, osmoregulatory substance synthesis, etc. They form an interconnected signal network (Zhao et al., 2020), for example, there are a variety of CBL-interacting protein kinases (CIPKs) modules in plants, among which the most common pathway used to transmit salt stress signals is the SOS pathway (Salt Over Sensitive) (Zhu, 2002). The protein kinase SOS2 is mainly recruited and activated by calcium sensor SOS3 and then, SOS2 phosphorylates the Na+/H+ reverse transporter, SOS1, which is located on the cell membrane (Qiu et al., 2002), and finally reduces the absorption of Na+ by excreting it out of the cell. In addition, as a reverse transporter of Na+/H+ on the vacuole membrane, NHX1 can also transport cytoplasmic Na+ to the vacuole to prevent excessive concentration of Na+ in the cytoplasm and adverse effects it caused on cells (Barragán et al., 2012), and maintain cell cation homeostasis (Bassil et al., 2019). Finally reduces the absorption of Na+ by excreting it out of the cell.

DUF families are characterized by relatively conserved amino acid sequences and unknown functional domains (Finn et al., 2016). In the Pfam 35.0 database, the Pfam database contains 4795 DUF or UPF families, accounting for 24% of the total protein families in the Pfam database. DUF families are divided into different families based on their specific domains. Studies have shown that DUF families play an important role in plant growth, development, breeding and resistance to biotic and abiotic stresses (Lv et al., 2023). OsRMC mediates root development through jasmonic acid (JA) pathway, it also negatively regulates root curl and participates in stomatal development; in Arabidopsis thaliana, overexpression of DUF761-1 could affect leaf development, shorten leaf length, root length, inflorescence and horn fruit, and reduce seed number; OsSAC1, containing two conserved DUFs—DUF4220 and DUF594, affects sugar accumulation in rice leaves (Serra et al., 2013; Zhu et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2019). In addition, DUFs also contribute to plant abiotic stress response. Overexpression of OsDSR2 could increase sensitivity to salt and simulated drought stress and reduce ABA sensitivity of rice. OsSIDP301, a member of the DUF1644 family, negatively regulates salt stress and grain size in rice, while OsSIDP366, another member of this family, positively regulates responses to drought and salt stresses in rice (Luo et al., 2014; Guo et al., 2016; Ge et al., 2022).

The DUF868 family is widely expressed in plants, but little research has been done on this family. In the study presented here, we showed that OsDUF868.12, which was named according to the order of distribution of DUF868 members on chromosomes in rice, could respond to a variety of abiotic stresses and overexpression of OsDUF868.12 could enhance the salt tolerance of rice.

Rice (Oryza sativa L. subsp. japonica cv. Nipponbare) seeds were used as wild type (WT) and materials for genetic transformation. In all experiments, the seeds were soaked with 2% (v/v) NaClO for 30 min, washed with sterile water and subsequently subjected to imbibition at 37°C for 3 days in the dark. Then, the germinated seeds were cultured in nutrient solution under a cycle of 16-h light at 28°C and 8-h dark at 25°C.

The OsDUF868.12 gene was amplified from WT and cloned into the pU1300 vector to obtain overexpression lines (OsDUF868.12-OE), and knockout lines (OsDUF868.12-KO) were obtained by using the clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR-Cas9) technique. To obtain the expression profile of OsDUF868.12, the promoter sequence of 1500 bp of OsDUF868.12 was obtained through the NCBI database and amplified from the rice genomic DNA, the pCAMBIA1305 vector was duplexed with Hind III and Noc I endonuclease, followed by recombination. To explore the subcellular localization of OsDUF868.12, its coding sequence was amplified from WT and, subsequently, recombination ligation was performed with the pCAMBIA2300-GFP vector, which was duplexed with Hind III and BamH I endonuclease. Finally, the transgenic rice plants were obtained by Agrobacterium-mediated genetic transformation, and the overexpression lines and knockout lines were identified by RT-qPCR and DNA amplification sequencing, respectively.

To study the effect of abiotic stresses and ABA on the transcript accumulation of OsDUF868.12, three-leaf stage WT (Nipponbare) seedlings were used for stress treatments, including cold (4°C), hot (42°C), salt (150 mM NaCl), drought (20% w/v PEG6000) and ABA (50 μM). Leaves were taken at different periods (0 h, 0.5 h, 1 h, 2 h, 4 h, 8 h, 16 h, 24 h and 0 h treatment was the control group) to extract total RNA using Trizol reagent according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The reverse transcription was done using a PrimeScript™ RT reagent Kit with a gDNA Eraser kit, and the cDNA was stored at -20°C. The extracted cDNA was used as a template to analyze the transcript accumulation of OsDUF868.12 under normal and abiotic stress conditions. The initial amount of template cDNA in each amplification reaction was 10 µg. At least three independent biological replicates were performed for each experiment and the rice Ubiquitin gene (Os01g0328400) was used for internal control for qPCR normalization. The 2−ΔΔCT method was used to transform threshold cycle values (Ct) into normalized relative abundance values of mRNA. All primer pairs used were listed in Supplementary Table S1.

Different tissues of the OsDUF868.12p: GUS transgenic plants were collected and detected following the previous method. The tissues were placed in a buffer containing 50 mM NaPO4 (pH 7.2), 5 mM K3Fe (CN)6, 5 mM K4Fe (CN)6, 0.1% (w/w) Triton-100, and 1 mm X-Gluc, and they were incubated overnight at 37°C and soaked tissues in 70% (v/v) ethanol for 5 min to stop the staining. Then, 95% (v/v) ethanol was added and removed chlorophyll completely. Finally, photos were taken with ZEISS stereo microscope.

The seeds of green fluorescent protein (GFP) transgenic plants were germinated, and the roots of 6-day-old seedlings were taken and placed on a slide, mashed, and stained with 10 µM FM4-64 cell membrane dye. After staining, the excess dye solution was cleaned, the cover glass was covered, and the expression of OsDUF868.12-GFP fusion protein was observed under the confocal laser microscope.

Individually cultured Agrobacterium containing the pCAMBIA2300-GFP vector and the membrane marker vector in liquid media until the logarithmic growth phase. Then, the Agrobacteria were centrifuged at 4000 rpm for five minutes. The collected Agrobacteria were resuspended in the resuspension solution to an OD600 of 0.5–1, mixed in a 1:1 ratio, and the mixture was injected into the lower epidermis of tobacco leaves after two hours. The results were observed under a laser confocal microscope 2 days later. The resuspension solution consisted of 100 ml containing 100 µL of 10 mM ACE, 1 ml of 0.2 M MgCl2, 5 ml of 0.2 M MES (pH 5.6), and 93.9 ml of ddH2O.

In order to investigate the tolerance of transgenic lines to salt stress, the 2-day-old rice seedlings were cultured in a nutrient solution containing 150 mM NaCl for 6 days; and observed the growth inhibition status of shoot. Further, 2-week-old rice seedlings were cultured in a nutrient solution containing 200 mM NaCl for 6 days, followed by 10 days of recovery and calculated the survival rates. To investigate the resistance of transgenic rice to oxidative stress, the leaves of 2-week-old transgenic and WT seedlings were cut and placed in 2% (v/v) hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) solution for 2 days and observed the degree of leaf green fade. To investigate the response of transgenic lines to various exogenous plant hormones. The 2-day-old WT and transgenic lines were cultured in nutrient solution for 6 days, which contained 1 µM ABA, and observed the growth status.

The content of chlorophyll was measured as previously described (Gao et al., 2020). The leaves were cut into small pieces and soaked in extract (acetone: ethanol = 2:1) for 2 days in the dark. Subsequently, the samples were centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 5 minutes and the supernatant was collected. The absorbance of the supernatant was measured at wavelengths of 663 nm and 645 nm, respectively. [Chla] = (12.7*A663−2.69*A645)*V/(1000*W). [Chlb] = (22.9*A645−4.68*A663) *V/(1000*W), [Chlt] = [Chla) + [Chlb]. V: the total volume of the extract, W: the weight of the sample.

In order to determine the activities of superoxide dismutase (SOD), peroxidase (POD), content of malondialdehyde (MDA) and content of proline (Pro), the 2-week-old seedlings were transferred to nutrient solution containing or without 200 mM NaCl for 2 days and the aerial parts of the plants were sampled. The 0.2 g sample of the aerial parts was ground into powder by liquid nitrogen, then 3 mL of 100 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.8) was added and the sample was ground into a homogenate. The homogenate was centrifuged at 10,000×g for 10 min at 4°C and the supernatant was used for the assays.

In the SOD assay, 0.2 mL of supernatant was added to 4 mL 100 mM phosphoric acid solution (pH 7.8), 0.08 mL 1 mM EDTA-Na2, 0.27 mL 750 µM NBT, 0.27 mL 130 mM Met, and 0.27 mL 20 µM ribonucleotide in the experimental group. The supernatant was replaced with 0.2 mL PBS as control I and control II. Control I was placed in the dark, and the experimental group and control II were placed in light conditions for 15 min. Control I was used as a reference to adjust the zero and the absorbance at 560 nm was measured using an enzyme meter. In the POD assay, 0.2 mL of supernatant was added to 4 mL 100 mM phosphoric acid solution (pH 7.0), 2.3 µL of 0.2% (v/v) guaiacol, and 2 µL of 30% (v/v) hydrogen peroxide, and recorded the absorbance for 1 min at 470 nm. In the MDA content analysis, 0.1 mL of supernatant was added to 0.4 mL of 0.25% (w/v) Thiobarbituric acid (TBA), boiled for 15 min, and cooled in an ice bath for 5 min, the absorbance at both 532 and 600 nm was recorded for 1 min, respectively. In the content of Pro analysis, 10 mL of 3% sulfosalicylic acid, 10 mL acetic acid and 20 ml of 2.5% acid ninhydrin solution were mixed as reaction solution. 50 µL of supernatant was added to 1 ml of the reaction solution, and the absorbance at 520 nm was recorded.

In addition, Nitro blue tetrazolium (NBT) and 3’-diaminobenzidine (DAB) were used to detect the content of O2- and H2O2 in the leaves, as previously described (Chen et al., 2021a). The isolated leaves were placed in DAB and NBT solutions overnight at 28°C under light and after staining, and soaked in 95% ethanol overnight to remove chlorophyll.

The sequences of the OsDUF868.12 gene were downloaded from The Rice Genome Annotation Project (RGAP) database. The cis-acting elements were found by using the PlantCARE to analyze the promoter sequence of OsDUF868.12. Members of DUF868 family in rice were found in the rice RGAP database, and then other members of the DUF868 family in Zea mays, Arabidopsis thaliana and Solanum lycopersicum were found in the ensemble plants database. These data were finally analyzed through a phylogenetic tree, all experiments were repeated three times. These data were processed and analyzed by the t-test, with P < 0.05 (*) and P < 0.01 (**) to be significantly different.

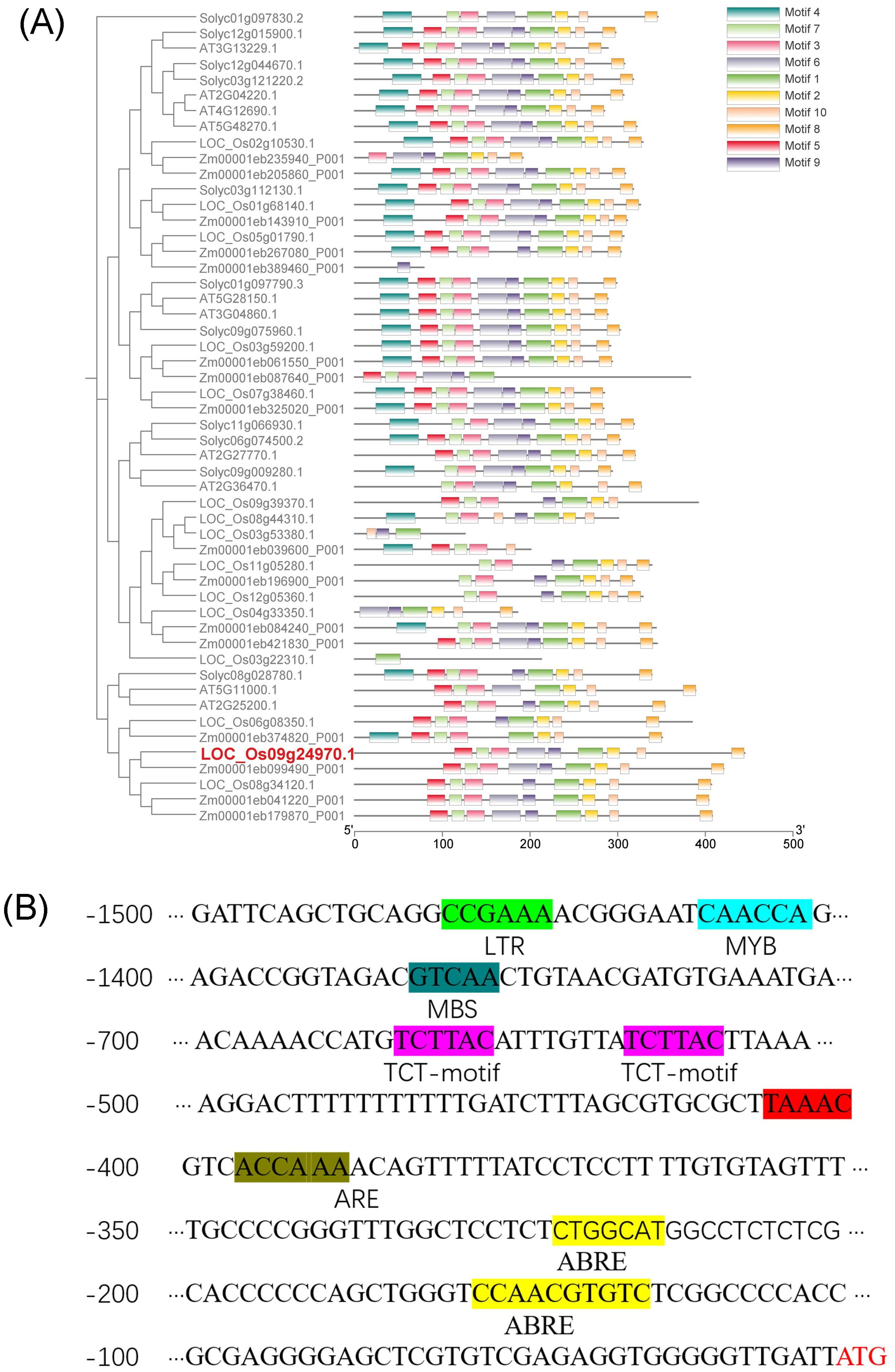

The genetic information of OsDUF868.12 was obtained through the RGAP database (rice.uga.edu/cgi-bin/ORF_infopage.cgi), and the results showed that OsDUF868.12 is located on chromosome 9 with an open reading frame of 1335 bp and no introns, encoding 444 amino acid residues. In order to understand the phylogenetic relationship of OsDUF868.12, other DUF868 family members from Oryza sativa, Zea mays, Arabidopsis thaliana and Solanum lycopersicum were selected for phylogenetic analysis in this study. The results showed that OsDUF868.12 (LOC_Os09g24970.1) had the closest evolutionary relationship with Zm00001eb099490_P001. Meanwhile, the motifs of protein sequences of DUF868 members were analyzed by using MEME software, and a total of 10 motifs were identified. The sequence of OsDUF868.12 had 9 motifs, and these motifs existed in the majority of DUF868 members, indicating that OsDUF868.12 was evolutionarily conservative (Figure 1A). Meanwhile, through the PlantCARE promoter online analysis tool, the 1500 bp promoter elements upstream of the ATG sequence (start codon sequence) of OsDUF868.12 was analyzed. It was found that in addition to a large number of basic promoter elements such as CAAT-box, TATA-box, there were several cis-acting elements related to abiotic stresses (Figure 1B), such as TCT-motif (light-responsive element), ABRE-motif (abscisic acid-responsive cis-element), LTR-motif (low-temperature-responsive element), MBS-motif (drought-induced MYB-binding element), ARE-motif (anaerobic-inducible element).

Figure 1. Bioinformatics analysis of OsDUF868.12. (A) Analysis of evolutionary relationship of DUF868 family. (B) Analysis of promoter sequence of OsDUF868.12.

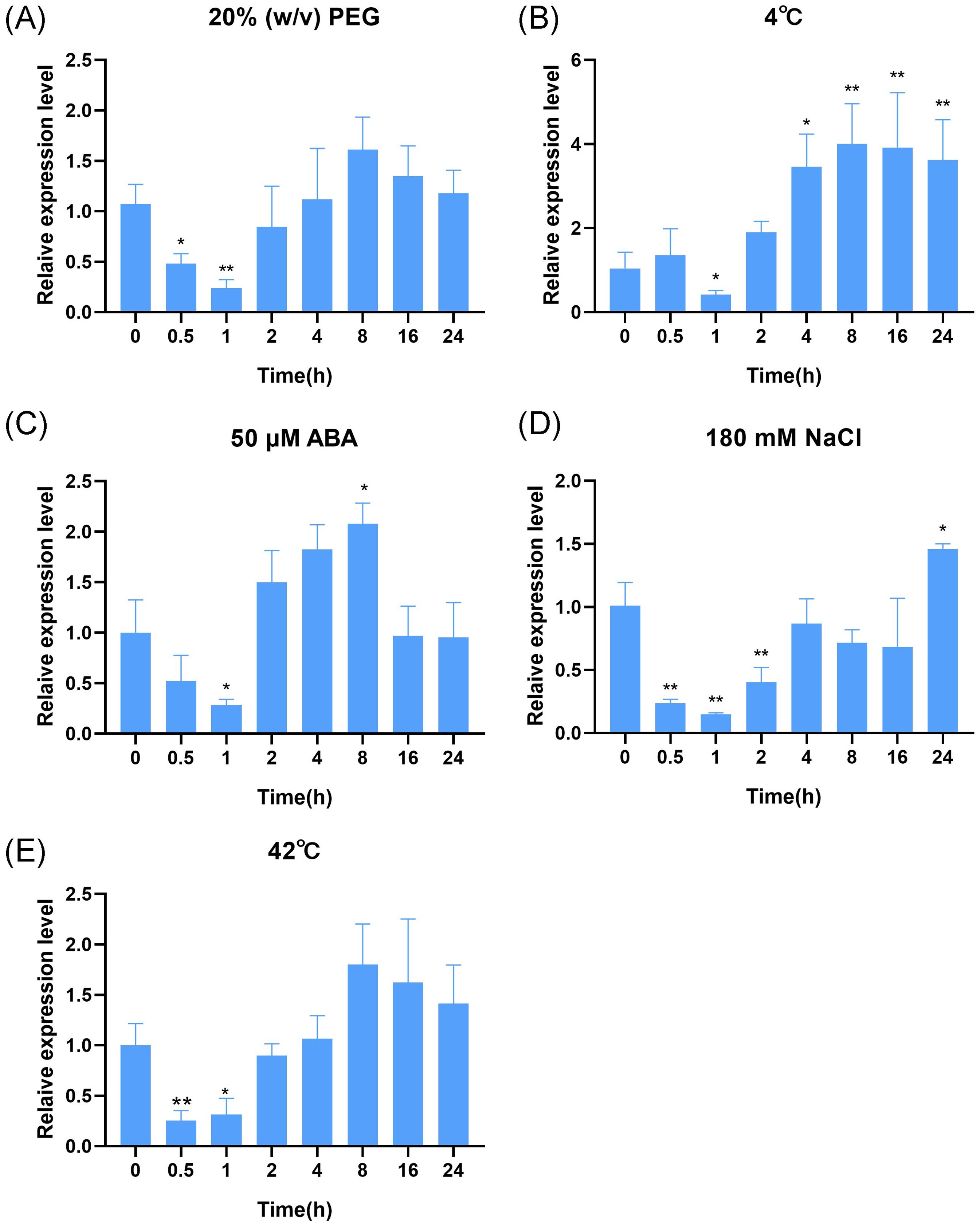

To understand the response of OsDUF868.12 to different types of abiotic stress. WT were treated with various abiotic and ABA at the three-leaf stage for 24 h and sampled, which were analyzed by RT-qPCR and the control group at the corresponding time was used as reference. We found that the transcript level of OsDUF868.12 fluctuated from a minimum of 0.24-fold under 20% (w/v) PEG treatment (Figure 2A) to a maximum of 4.00-fold under 4°C treatment (Figure 2B). In addition, we found that its transcript level was raised to 2.08, 1.46 and 1.80-fold under 50 µM ABA, 180 mM NaCl and 42°C (Figures 2C–E) treatment, respectively. Based on the significance analysis, we preliminarily inferred that OsDUF868.12 is most likely to respond to cold and salt stress.

Figure 2. The transcript levels of OsDUF868.12 in WT at the three-leaf stage under abiotic stress treatments. (A) 20% (W/V) PEG6000; (B) 4°C; (C) 50 µM ABA; (D) 180 mM NaCl; (E) 42°C. Data show the mean ± SD of three replicates. Asterisks indicate significant differences between 0 h and the rest of the time using t-test (*P<0.05, **P<0.01).

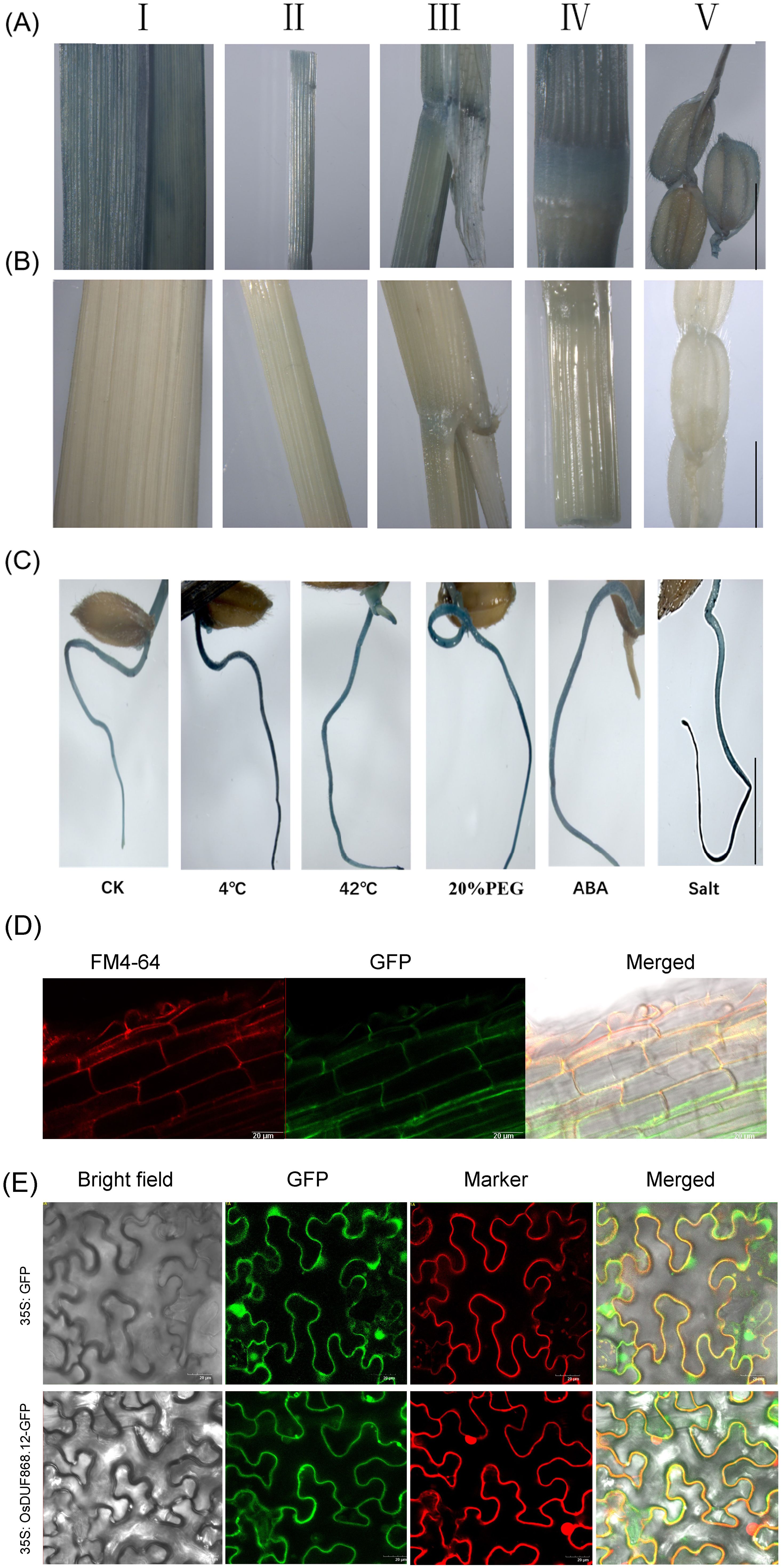

In order to analyze the expression pattern of OsDUF868.12 in situ, OsDUF868.12pro: GUS transgenic plants were constructed. Transgenic lines and WT (Figures 3A, B) were sampled and used for detection of β-glucuronidase (GUS) activity. The staining of different tissue sites, such as stem, leaf, ligule, internode, spike, and root, indicated that OsDUF868.12 could widely expressed in different tissues. In addition, in order to understand the role of this gene in stress response, 5-day-old transgenic seedlings were treated with 4°C, 42°C, 180 mM NaCl, 20% (w/v PEG) and 50µM ABA for 12 h and stained, it showed that the root staining was deepened in different degrees. Among them, the root staining was deepest under 4°C and salt treatments (Figure 3C), further implying that the gene could respond to a variety of abiotic stresses.

Figure 3. Histochemical GUS activity and subcellular localization. (A) GUS staining of different tissues of OsDUF868.12pro: GUS plants. (I: leaf; II: stem; III: leaf ligule; IV: internode; V: young spikelet hull). bar, 1 cm. (B) GUS staining of different tissues of WT (as a negative control for Figure. A). bar, 1 cm. (C) GUS staining of 5-day-old root of OsDUF868.12pro: GUS plants under abiotic stresses. bar, 2 cm. (D) Subcellular localization of OsDUF868.12 in root of rice. bar, 20 μm. (E) Subcellular localization of OsDUF868.12 in tobacco cells. bar, 20 μm.

In order to explore the subcellular localization of OsDUF868.12, GFP transgenic plants were constructed and the roots of plant seedlings were stained by FM4-64 staining solution, which was used as cell membrane dye, and OsDUF868.12 was localized in the cell membrane (Figure 3D). At the same time, we conducted subcellular localization experiments using Agrobacterium-mediated transient transformation in tobacco. The result also showed that OsDUF868.12 was localized in the cell membrane (Figure 3E), which was consistent with its localization in the root.

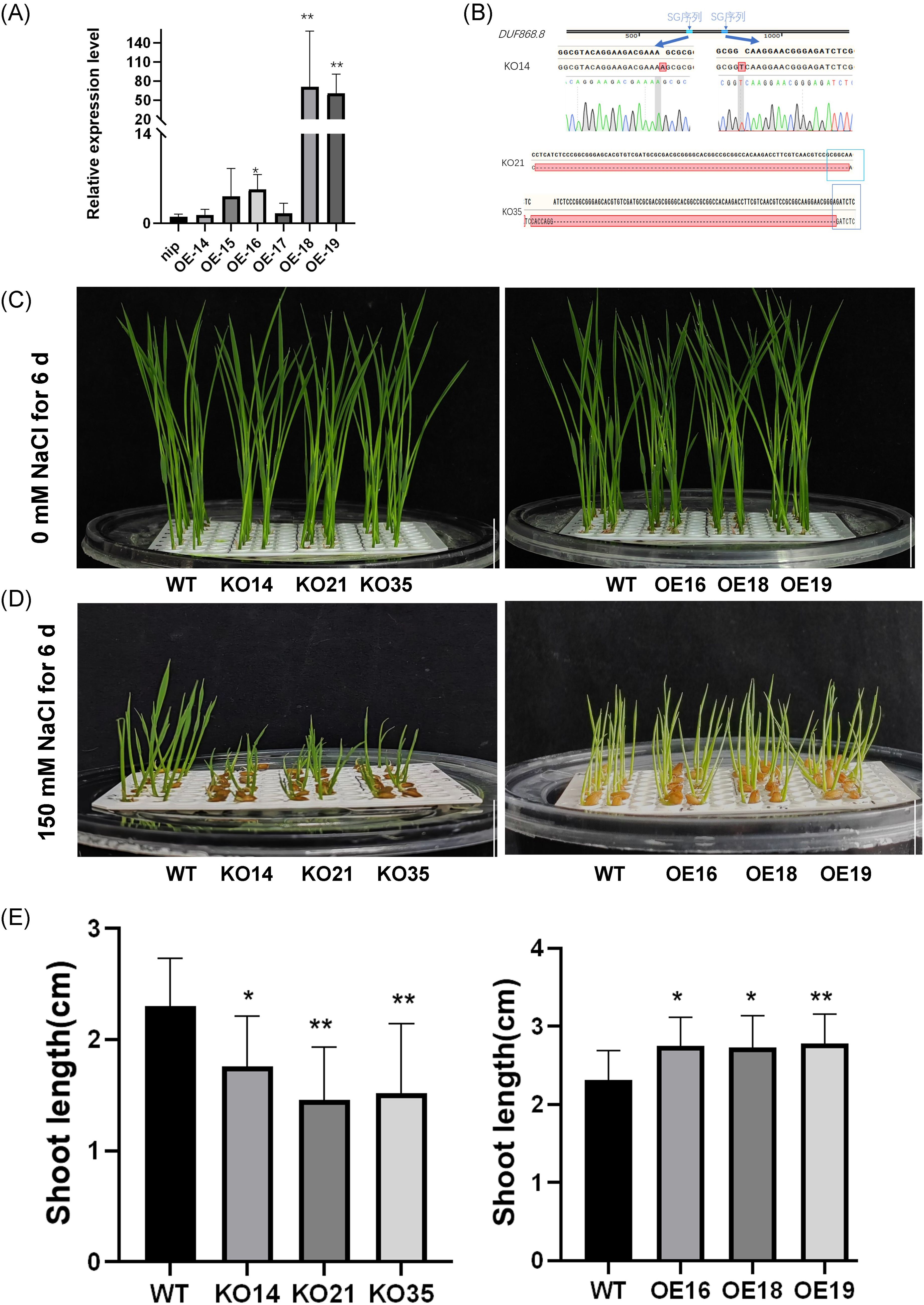

In order to investigate the role of OsDUF868.12 in the regulation of salt stress tolerance, overexpression and knockout lines were constructed, and the transgenic plants were identified by RT-qPCR and PCR. Three independent overexpression lines (OE16, OE18, and OE19) and three independent knockout lines (KO14, KO21, and KO35) were selected for subsequent experiments (Figures 4A, B). In the growth inhibition experiment, the 2-day-old transgenic and WT seedlings were grown in the nutrient solution containing or without 150 mM NaCl for 6 days. There was no significant difference between the transgenic and WT seedlings in the control group (Figure 4C). We found that under 150 mM NaCl treatment, the shoot length of knockout lines was significantly lower than WT under salt stress, but the overexpression lines had a better growth status than WT (Figures 4D, E).

Figure 4. Detection of transgenic lines and growth inhibition experiments under 150 mM NaCl treatment. (A) The transcript levels of the overexpression lines were detected by RT-qPCR. (B) Detection of knockout sites. (C) Plant height of 2-day-old transgenic lines and WT after 6 days of growth under normal nutrient solution. bar, 1cm. (D) Plant height of 2-day-old seedlings after 6 days of growth under 150 mM NaCl. bar, 1 cm. (E) Statistics of plant height of transgenic lines and WT. Data show the mean ± SD of three replicates. Asterisks indicate significant differences between transgenic lines and WT using t-test (*P<0.05, **P<0.01).

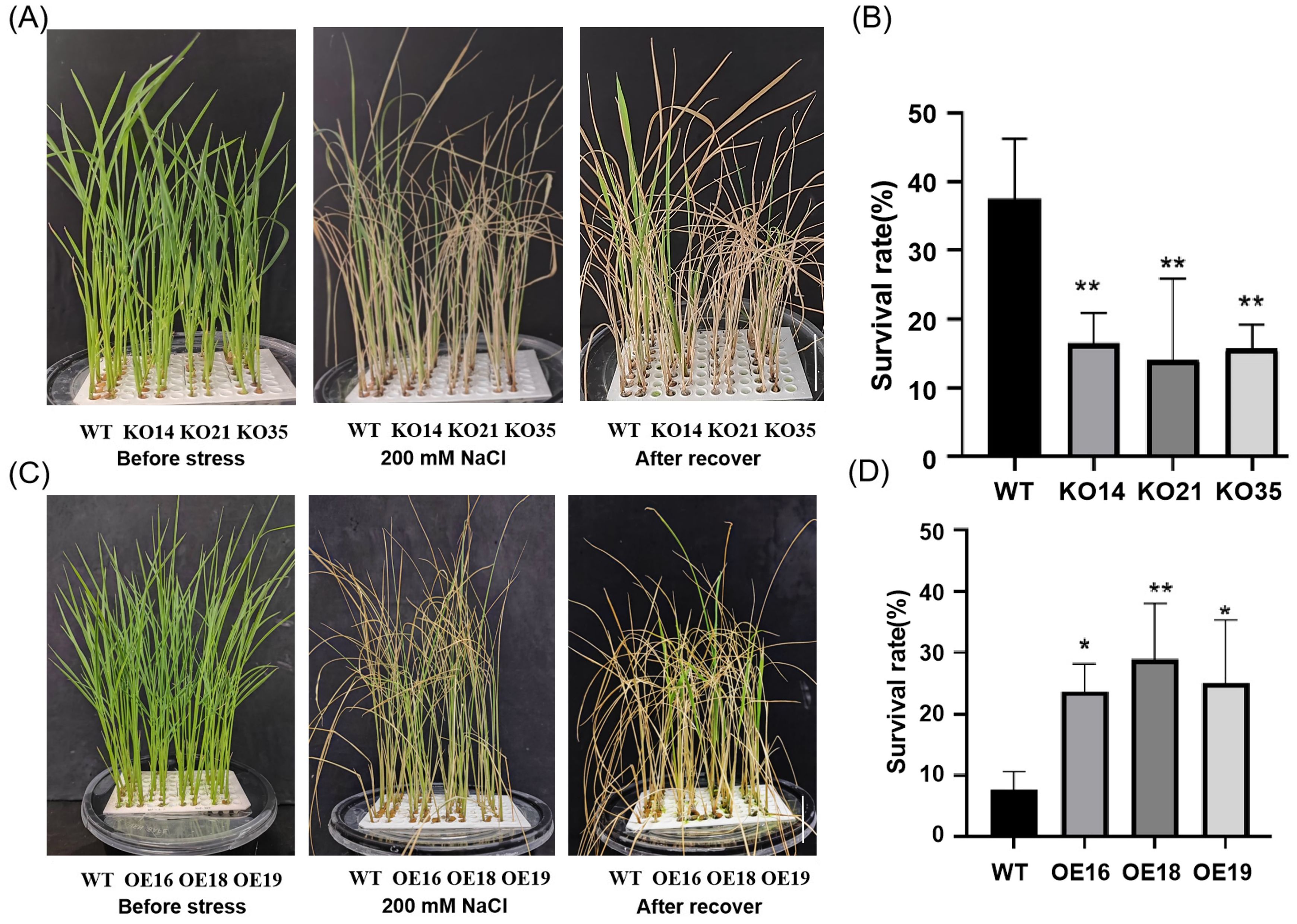

Furthermore, 2-week-old transgenic and WT seedlings were treated with 200 mM NaCl and the survival rates were observed. We found that after 6 days of treatment, compared with WT, the knockout lines exhibited more severe salt damage phenomena, manifested by more severe leaf chlorosis (Figure 5A), while the overexpression lines were opposite (Figure 5C). After recovery for 15 days, the survival rate of the knockout lines was significantly lower than WT (Figure 5B), but that of the overexpression lines were higher (Figure 5D). In summary, the knockout of OsDUF868.12 significantly reduced the tolerance of rice seedlings to salt stress, and overexpression of OsDUF868.12 significantly increased the tolerance of rice seedlings to salt stress.

Figure 5. Survival experiment of transgenic lines and WT under 200 mM NaCl treatment. (A) Phenotype of 2-week-old WT and knockout lines before and after 200 mM NaCl treatment for 6 days and recovery for 15 days. bar, 5 cm. (B) Survival rate of WT and knockout lines after 200 mM NaCl treatment. (C) Phenotype of 2-week-old WT and the overexpression lines before and after 200 mM NaCl treatment for 6 days and recovery for 15 days. bar, 5 cm. (D) Survival rate of WT and knockout lines after 200 mM NaCl treatment. Data show the mean ± SD of three replicates. Asterisks indicate significant differences between transgenic lines and WT using t-test (*P<0.05, **P<0.01).

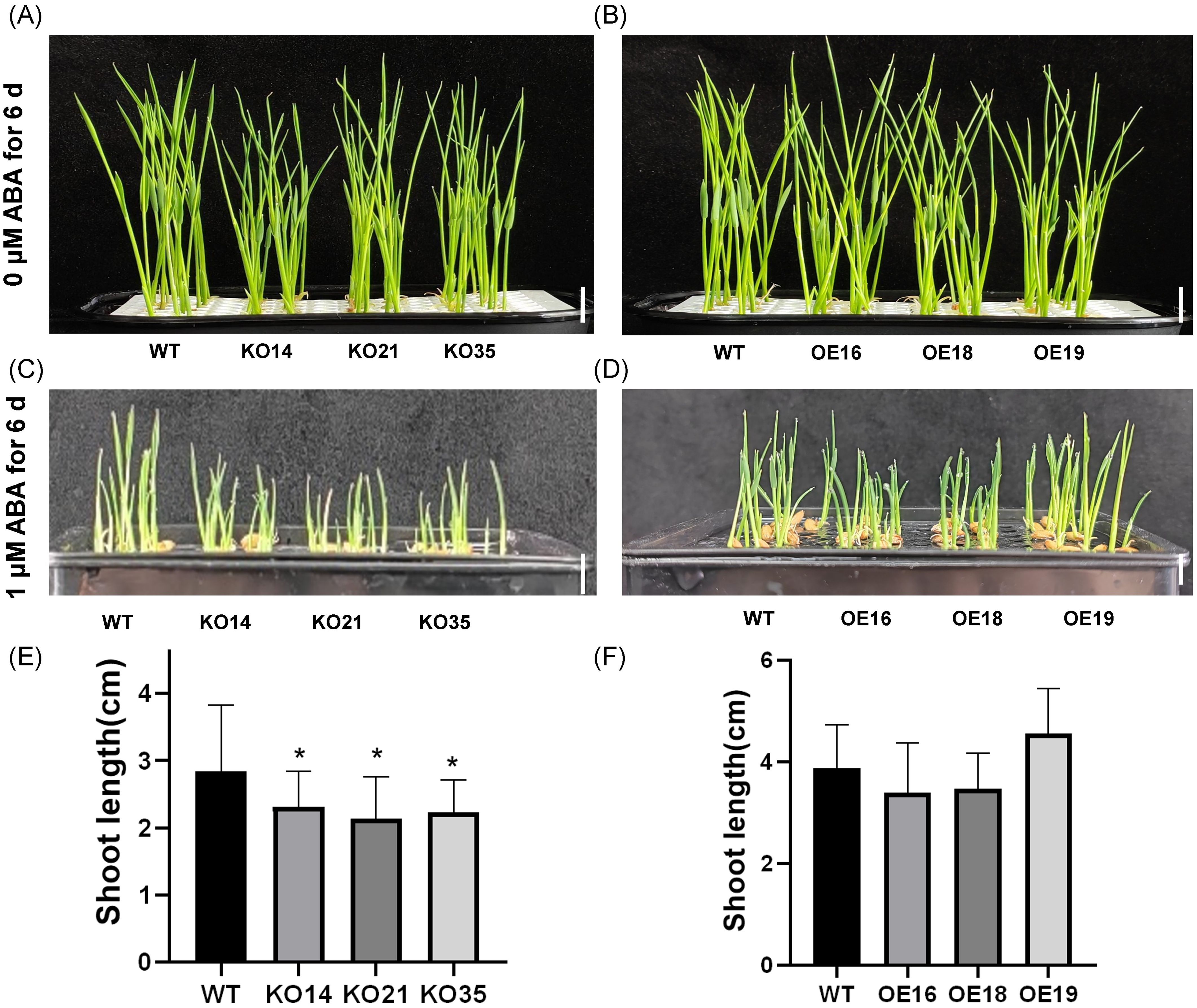

ABA is an important signaling molecule in plants in response to adversity stress, which could reduce salt stress damage by reducing Na+/K+ in plants, inducing the accumulation of osmotic substances and alleviating damage caused by osmotic and various ionic stresses (Qiao et al., 2023). To investigate whether OsDUF868.12 regulates salt stress tolerance of rice in ABA-dependent pathways. We first explored the response of OsDUF868.12 transgenic plants to exogenous ABA during the germination period. The 2-day-old transgenic and WT seedlings were grown in nutrient solution containing or without 1 µM ABA for 6 days. There was no significant difference between transgenic and WT seedlings in the control group (Figures 6A, B). Under exogenous ABA treatment, the shoot length of the knockout lines was significantly lower than WT, while there was no significant difference between the overexpression lines and WT (Figures 6C–F). The results showed that overexpression of OsDUF868.12 could decrease the sensitivity of rice to exogenous ABA compared to the knockout of OsDUF868.12.

Figure 6. Inhibition of plant height of 2-day-old seedlings by ABA. (A, B) Plant height of 2-day-old seedlings after 6 days of growth under normal nutrient solution. bar, 1 cm. (C, D) Plant height of 2-day-old seedlings after 6 days of growth under 1 µM ABA. bar, 1cm. (E, F) Statistics of plant height for Figures (C, D). Data show the mean ± SD of three replicates. Asterisks indicate significant differences between clines and WT using t-test (*P<0.05).

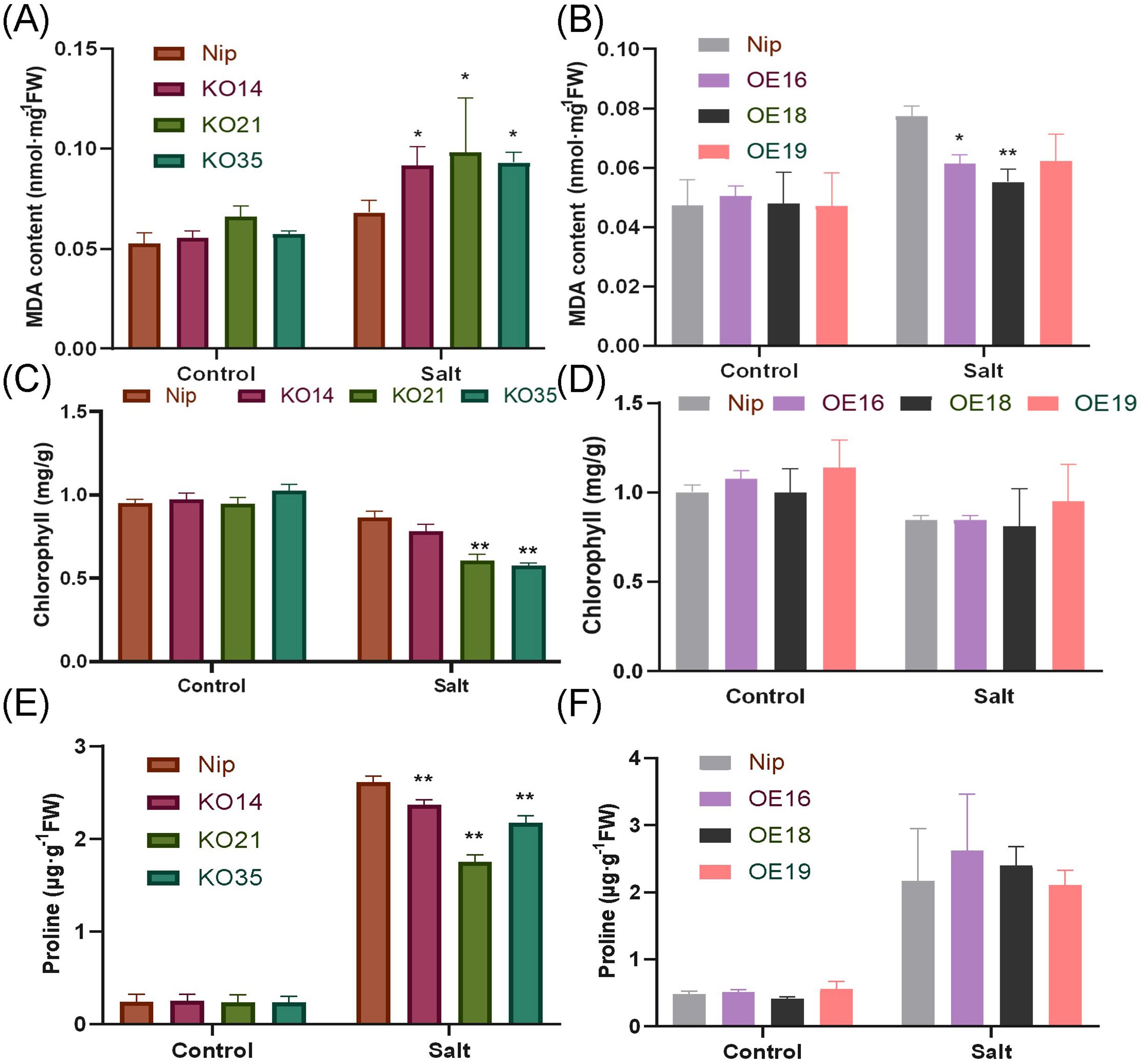

Measurement of MDA and chlorophyll content could be used to assess the degree of damage degree of plant cells. In this study, there was no difference in the MDA content between transgenic lines and WT under normal condition. After 200 mM NaCl stress treatment for 3 days, the MDA content of the knockout lines was significantly higher than WT, and the overexpression lines were opposite (Figures 7A, B). Similar results were also reflected in experiments for the determination of chlorophyll content. After salt stress treatment, compared with WT, less chlorophyll was retained in the knockout lines and there were significant differences in KO21 and KO35, but there was no significant difference between the overexpressed lines and WT (Figures 7C, D). Proline is an important osmoregulatory substance, which is commonly used to protect cells. In this study, no significant difference in proline content in control group. After treatment, the accumulation of proline in the knockout lines was significantly lower than that of WT (Figures 7E, F). Above results illustrated that overexpression of OsDUF868.12 could reduce the cell damage caused by salt stress.

Figure 7. Analysis of MDA, chlorophyll and Proline content of WT and transgenic plants under normal and 200 mM NaCl-treated conditions. (A, B) MDA content, (C, D) chlorophyll content, (E, F) Pro content. Data show the mean ± SD of three replicates. Asterisks indicate significant differences between transgenic lines and WT using t-test (*P<0.05,**P<0.01).

ROS, such as hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and superoxide anion radicals (O2-), are produced and accumulated in plants under abiotic stress, and excessive accumulation of ROS is harmful to the plant. In this study, NBT and DAB staining were used to assess the accumulation of ROS in 2-week-old seedlings before and after 200 mM NaCl stress treatment. We found there was no significant difference in the control group. After 2 days of 200 mM NaCl treatment, compared with WT, more blue-purple spots and more severe surface browning appeared on the leaves of the knockout lines (Figures 8A, B), indicating that the knockout lines accumulated more ROS than WT, while the overexpression lines were opposite. Meanwhile, we treated 0.1g of leaves from WT and transgenic lines by using H2O2. After being treated with 2% (v/v) H2O2 for 2 days, the degree of leaf chlorosis of the overexpression lines was lower than that of WT, while the knockout lines were the opposite (Figure 8C). We further extracted chlorophyll from the leaves using extract (acetone: ethanol = 2:1). There was no significant difference between transgenic and WT seedlings in the control group. In the treated group, the chlorophyll content of the knockout lines was significantly lower than that of WT, while the chlorophyll content of the overexpression lines was significantly higher than that of WT (Figure 8D), indicating that the overexpression lines were more resistant to H2O2. Above results indicated that overexpression of OsDUF868.12 could increase the oxidative stress tolerance of rice.

Figure 8. The accumulation of ROS level in leaves of 2-week-old transgenic plants of OsDUF868.12 and WT before and after 2 days of treatment using 200 mM NaCl and oxidation experiment of H2O2. (A) DAB staining. bar, 3 mm. (B) NBT staining. bar, 3mm (C) 2% (v/v) H2O2 treated detach leaves for 2 days. bar, 1 cm. (D) The chlorophyll content of leaves before and after 2 days H2O2 treatment. Data show the mean ± SD of three replicates. Asterisks indicate significant differences between transgenic lines and WT using t-test (*P<0.05, **P<0.01).

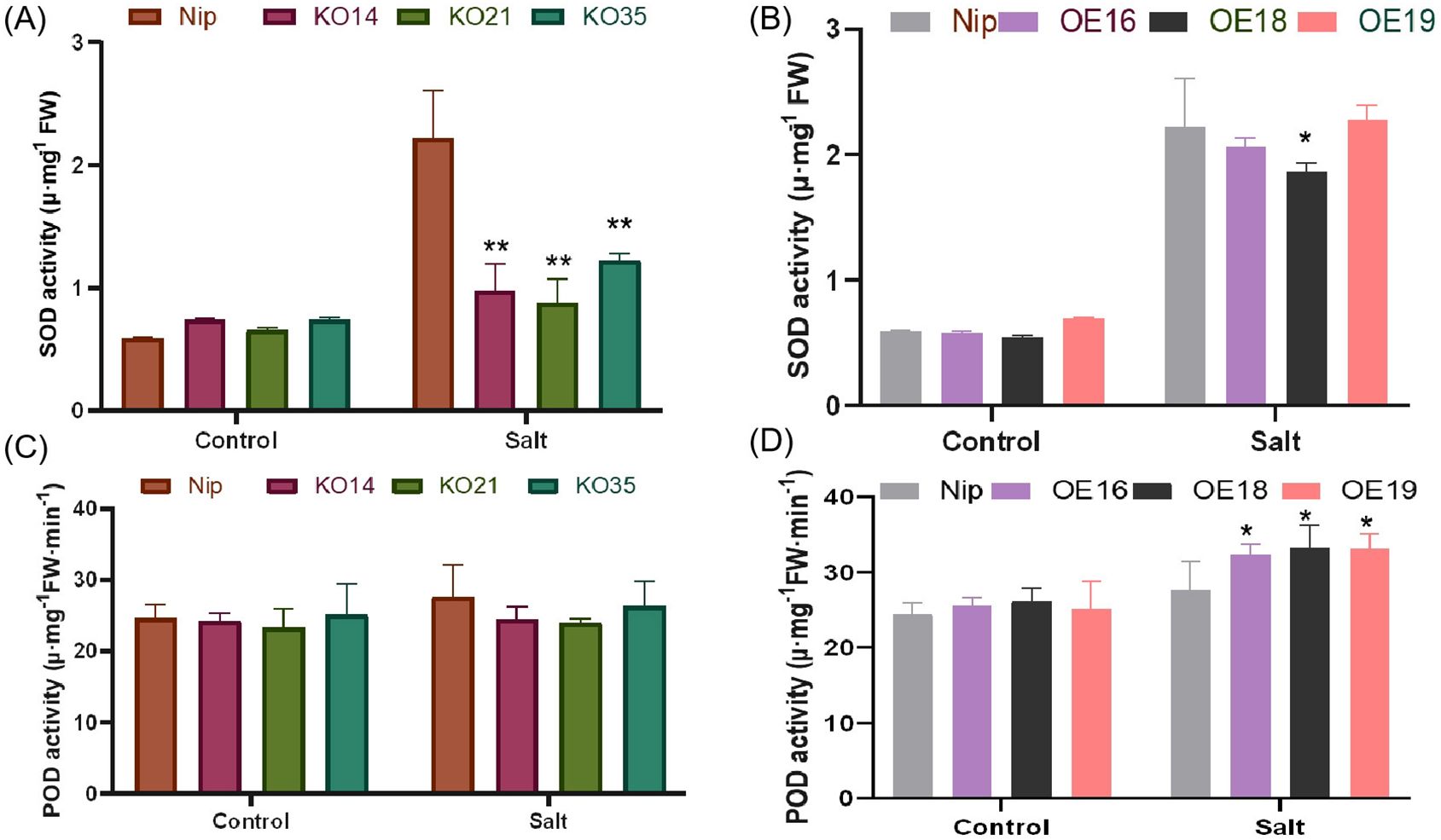

In order to explore whether the differences in ROS accumulation between WT and transgenic lines were related to ROS-scavenging enzyme activities, the activities of SOD and POD were assayed, which are indicators were used to assess superoxide dismutase and peroxidase activities, respectively. Under normal condition, there was no significant difference in SOD and POD activities between WT and transgenic seedlings. After 3 days of salt stress treatment, both SOD and POD activities increased, but SOD activity of the knockout lines was significantly lower than WT (Figure 9A), while no significant difference was found between the overexpression lines and WT (Figure 9B). The POD activity of the overexpression lines was significantly higher than WT (Figure 9C), while that of the knockout lines did not change much (Figure 9D). In the previous study, it was also found that the accumulation of ROS in the overexpression lines was lower than that in WT and the knockout lines. Above results indicated that overexpression of OsDUF868.12 could be able to increase the activity of the ROS-scavenging system, thereby reducing the accumulation of ROS and ultimately enhance salt stress tolerance.

Figure 9. Analysis of SOD and POD activity. (A, B) SOD activity. (C, D) POD activity. Data show the mean ± SD of three replicates. Asterisks indicate significant differences between transgenic lines and WT using t-test (*P<0.05, **P<0.01).

To further investigate the possible molecular mechanisms of salt tolerance in OsDUF868.12, we determined the transcript accumulation of some stress-responsive genes, such as OsLEA3, encoding a late embryogenesis abundant protein, which is a protective protein with a small molecular weight (Moons et al., 1997); OsRbohb, a respiratory burst oxidase homologue, has ROS-generating activity and its expression is mediated by stresses such as salt and drought (Wang et al., 2016); OsSOS1 and OsSOS3 are two critical proteins in the SOS pathway, responsible for Na+ extrusion at the plasma membrane and sensing cytosolic calcium signals, respectively (Gupta et al., 2021); while OsNHX1 encodes a Na+/H+ antiporter located on the vacuolar membrane (Fukuda et al., 2011). After treatment with 200 mM NaCl for 8 h, the transcript levels of OsLEA3 gene were significantly higher in the overexpression lines and lower in the knockout lines than WT (Figure 10A). The transcript levels of OsRbohB were significantly higher in the knockout lines and slightly lower in the overexpression lines than WT (Figure 10B). In addition, the transcript levels of OsSOS1, OsSOS3, and OsNHX1 were significantly higher than WT in overexpression lines and lower than WT in the knockout lines (Figures 10C–E).

Figure 10. Transcript levels of stress-related genes in transgenic lines and WT treated with 200 mM NaCl for 8 (h) (A) OsLEA3. (B) OsRbohB. (C) OsSOS3. (D) OsSOS1. (E) OsNHX1. Data show the mean ± SD of three replicates. Asterisks indicate significant differences between transgenic lines and WT using t-test (*P<0.05, **P<0.01).

Soil salinization is one of the important elements limiting the development of agriculture, and the effects of salt stress on plants mainly include osmotic stress, specific ionic toxicity, nutrient imbalance and ROS (Abbasi et al., 2016). In previous studies, many genes were found to be involved in plant response to salt stress, genes such as GmCBSDUF3, AtRH17, OsDUF6 and BrOAT1 can increase plant tolerance to salt stress through positive regulation (Jung et al., 2013; Seok et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2021b; Lv et al., 2023); MdERF4, GhVIM28, and CYSTM3 can also decrease plant tolerance to salt stress through negative regulation (An et al., 2018; Xu et al., 2019; Yang et al., 2024).

Members of DUF families of proteins have been reported to play important roles at various stages of plant growth. In Arabidopsis thaliana, DUF246 could affect male fertility and the biosynthesis of pectic arabinogalactans. In Populus tremula (Stonebloom et al., 2016), DUF266 could increase cellulose content, reduce recalcitrance (Yang et al., 2017), and enhance biomass production. In rice, DUF1618 could induce hybrid incompatibility (Shen et al., 2017).

In this study, we identified OsDUF868.12 of the OsDUF868 protein family member, which encodes a protein localized to the cell membrane. The results of GUS staining and changes in transcript levels of OsDUF868.12 in WT under abiotic stresses indicate that OsDUF868.12 mainly responds to cold and salt stress.

To further understand the role of OsDUF868.12 in abiotic stress responses, we constructed overexpression and knockout lines. Under the culture of nutrient solution containing 150 mM NaCl, the growth state of the overexpression lines was less inhibited than WT, showing higher plant height, but the growth state of the knockout lines was more inhibited than WT. Meanwhile, under the culture of nutrient solution containing 200 mM NaCl, we found that the overexpression lines exhibited slower leaf chlorosis and the survival rates were higher than WT, while the knockout lines were opposite. Above results preliminarily indicated that OsDUF868.12 could be able to increase the tolerance of rice to salt stress.

ROS has been identified as a class II small molecule that mediates the response to various abiotic stresses such as flooding, heavy metals, and high salinity. Under normal conditions, the generation of ROS at low levels can serve as intercellular signaling molecules, inducing responses in the antioxidant defense system. Conversely, the accumulation of excess ROS can lead to severe oxidative damage, impairing normal biological functions (Hasanuzzaman et al., 2020). It is produced by molecular oxygen and can be scavenged by superoxide dismutase, peroxidase, catalase and glutathione reductase (GR), which are essential for ROS homeostasis. NBT and DAB are used to determine the levels of O2- and H2O2, respectively (Steffens et al., 2013). We found that under salt stress treatment, the overexpression lines had both lighter NBT and DAB staining compared to WT, while the knockout lines were opposite, demonstrating that the overexpression lines showed less accumulation of ROS under salt stress, while the knockout lines of OsDUF868.12 showed deeper accumulation of ROS. MDA is used as an indicator of the degree of ROS-induced cell membrane damage and lipid peroxidation, for example, transgenic tobacco lines of EsSPDS1 showed less accumulation of malondialdehyde in parallel with less ROS accumulation compared to WT (Zhou et al., 2015). In this study, the overexpression lines were found to have lower MDA assay under salt stress condition, which was consistent with the trend of less ROS accumulation. Changes in chlorophyll content are usually the opposite of changes in ROS. Under drought stress, overexpression lines of CYP71D8L had less ROS and more chlorophyll compared to WT (Zhou et al., 2020). In this experiment, compared with WT, the chlorophyll content of the knockout lines decreased more under salt stress. In addition, Proline is an important osmoregulatory substance, and the accumulation of it could improve the tolerance of plants to osmotic stress (Kishor et al., 1995), which further improves the tolerance of plants to salt stress. In this study, the overexpression lines accumulated more content of proline compared to WT. These results demonstrated that OsDUF868.12 was able to improve antioxidant and salt stress tolerance in rice.

Under biotic and abiotic stresses, intracellular ROS homeostasis is disrupted by either enhanced ROS generation capacity or diminished ROS scavenging capacity (Wan et al., 2023), so increasing antioxidant enzyme activities to reduce ROS overproduction is the most effective way to improve plant resistance to abiotic stresses (Panda et al., 2021). Overexpression of ThbHLH1 and overexpression of zmlbd5 increased POD and SOD activities, thereby reducing the accumulation of ROS (Ji et al., 2016; Xiong et al., 2022). In this experiment, we found that the enzyme activities of transgenic lines of OsDUF868.12 were not significantly different from those of WT under normal culture conditions, whereas after salt stress treatment, the POD activity was slightly lower than that of WT in the knockout lines, whereas the enzyme activity was significantly higher than WT in the overexpression lines. The SOD activity was significantly lower than WT in the knockout lines, whereas there was no significant difference between the overexpression lines and WT. These results demonstrated that OsDUF868.12 could be able to improve the salt tolerance of rice by increasing the activities of SOD and POD.

ABA, the important stress hormone, is known to regulate different events of plant development in response to adverse environmental conditions and enable plants to withstand abiotic stresses. In general, increased tolerance to abiotic stresses and increased sensitivity to ABA in transgenic plants are correlated. In wheat, the overexpression of TaASR1-D enhanced tolerance to several abiotic stresses while enhancing sensitivity to ABA (Qiu et al., 2021). In this experiment, overexpression of OsDUF868.12 increased salt tolerance and decreased ABA sensitivity, which is consistent with the fact that the overexpression of OsPP108 increased salt tolerance and decreased ABA sensitivity, in Arabidopsis thaliana (Singh et al., 2015). Therefore, it is initially hypothesized that OsDUF868.12 negatively regulates ABA signaling like OsPP108.

LEA is a class of protective proteins with small molecular weight, and a large number of studies have shown that it not only enhances osmoregulation, but also protects the function of proteins and enzymes thereby positively regulating plant resistance to abiotic stresses (Boucher et al., 2010; Liu et al., 2010; Su et al., 2011; Furuki and Sakurai, 2014). R proteins are a class of respiratory burst oxidase homologs, the large production of this enzyme leads to elevated ROS in plants (Foreman et al., 2003). The transcript level of OsLEA3 gene in the overexpression lines was higher than WT after salt treatment, which was consistent with overexpression being more resistant to salt stress. The transcript level of OsRbohB in the overexpression lines was lower than WT, similarly consistent with the fact that the overexpression lines accumulated less ROS after salt stress treatment compared to WT.

OsSOS1 and OsSOS3 are responsible for Na+ efflux from the plasma membrane (Qiu et al., 2002), OsNHX1 promotes Na+ to enter the vesicle membrane, which plays an important role in ion homeostasis (Wang et al., 2022). They were significantly differentially expressed between overexpression plants and the knockout lines after salt stress treatment. The transcript levels of these genes in the overexpression lines were significantly higher than WT after stress treatment, while their transcription levels were slightly lower in the knockout lines. The tolerance to salt stress in the overexpression lines of OsDUF868.12 was inextricably linked to the up-regulation of these salt tolerance genes.

This study focused on the biological function of OsDUF868.12 under salt stress treatment. The results showed that the overexpression lines were more tolerant to salt stress, while the knockout lines were more sensitive to salt stress, suggesting that overexpression of OsDUF868.12 could improve salt stress tolerance of rice. These findings provide a reference for further in-depth study of the OsDUF868.12 and the development of other members of the DUF868 protein family.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

HC: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JW: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JLZ: Writing – review & editing. ZW: Writing – review & editing. CM: Writing – review & editing. WX: Writing – review & editing. JY: Writing – review & editing. YK: Writing – review & editing. XZ: Writing – review & editing. RC: Writing – review & editing. JQZ: Writing – review & editing. ZX: Writing – review & editing. LL: Writing – review & editing, Methodology.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by Sichuan Science and Technology Program under Grant Numbers 2021YFH0085.

We are grateful to the Rice Research Institute of Sichuan Agricultural University for providing this research platform.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2025.1458467/full#supplementary-material

DUF, Domain of Unknown Function; WT, wild type; GFP, green fluorescent protein; GUS, β-glucuronidase; SOD, superoxide dismutase; POD, peroxidase; MDA, malondialdehyde; Pro, proline; NBT, Nitroblue tetrazolium; DAB, 3’-diaminobenzidine.

Abbasi, H., Jamil, M., Haq, A., Ali, S., Ahmad, R., Malik, Z., et al. (2016). Salt stress manifestation on plants, mechanism of salt tolerance and potassium role in alleviating it: a review. Zemdirbyste-Agriculture 103, 229–238. doi: 10.13080/z-a.2016.103.030

An, J. P., Zhang, X. W., Xu, R. R., You, C. X., Wang, X. F., Hao, Y. J. (2018). Apple MdERF4 negatively regulates salt tolerance by inhibiting MdERF3 transcription. Plant Sci. 276, 181–188. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2018.08.017

Barragán, V., Leidi, E. O., Andrés, Z., Rubio, L., De Luca, A., Fernández, J. A., et al. (2012). Ion exchangers NHX1 and NHX2 mediate active potassium uptake into vacuoles to regulate cell turgor and stomatal function in arabidopsis. Plant Cell 24, 1127–1142. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.095273

Bassil, E., Zhang, S. Q., Gong, H. J., Tajima, H., Blumwald, E. (2019). Cation specificity of vacuolar NHX-type cation/H antiporters. Plant Physiol. 179, 616–629. doi: 10.1104/pp.18.01103

Boucher, V., Buitink, J., Lin, X. D., Boudet, J., Hoekstra, F. A., Hundertmark, M., et al. (2010). MtPM25 is an atypical hydrophobic late embryogenesis-abundant protein that dissociates cold and desiccation-aggregated proteins. Plant Cell Environ. 33, 418–430. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2009.02093.x

Chen, H. C., Chien, T. C., Chen, T. Y., Chiang, M. H., Lai, M. H., Chang, M. C. (2021a). Overexpression of a novel ERF-X-type transcription factor, OsERF106MZ, reduces shoot growth and tolerance to salinity stress in rice. Rice 14, 18. doi: 10.1186/s12284-021-00525-5

Chen, P. H., Yang, J., Mei, Q. L., Liu, H. Y., Cheng, Y. P., Ma, F. W., et al. (2021b). Genome-wide analysis of the apple CBL family reveals that Mdcbl10.1 functions positively in modulating apple salt tolerance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 12430. doi: 10.3390/ijms222212430

Fedoroff, N. V., Battisti, D. S., Beachy, R. N., Cooper, P. J. M., Fischhoff, D. A., Hodges, C. N., et al. (2010). Radically rethinking agriculture for the 21st century. Science 327, 833–834. doi: 10.1126/science.1186834

Finn, R. D., Coggill, P., Eberhardt, R. Y., Eddy, S. R., Mistry, J., Mitchell, A. L., et al. (2016). The Pfam protein families database: towards a more sustainable future. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, D279–D285. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1344

Foreman, J., Demidchik, V., Bothwell, J. H., Mylona, P., Miedema, H., Torres, M. A., et al. (2003). Reactive oxygen species produced by NADPH oxidase regulate plant cell growth. Nature 422, 442–446. doi: 10.1038/nature01485

Fukuda, A., Nakamura, A., Hara, N., Toki, S., Tanaka, Y. (2011). Molecular and functional analyses of rice NHX-type Na+/H+ antiporter genes. Planta 233, 175–188. doi: 10.1007/s00425-010-1289-4

Furuki, T., Sakurai, M. (2014). Group 3 LEA protein model peptides protect liposomes during desiccation. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta-Biomembranes 1838, 2757–2766. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2014.07.009

Gao, S. X., Song, T., Han, J. B., He, M. L., Zhang, Q., Zhu, Y., et al. (2020). A calcium-dependent lipid binding protein, OsANN10, is a negative regulator of osmotic stress tolerance in rice. Plant Sci. 293, 11. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2020.110420

Ge, L., Guo, H. M., Li, X., Tang, M., Guo, C. M., Bao, H., et al. (2022). OsSIDP301, a member of the DUF1644 family, negatively regulates salt stress and grain size in rice. Front. Plant Sci. 13. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.863233

Guo, C. M., Luo, C. K., Guo, L. J., Li, M., Guo, X. L., Zhang, Y. X., et al. (2016). OsSIDP366, a DUF1644 gene, positively regulates responses to drought and salt stresses in rice. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 58, 492–502. doi: 10.1111/jipb.12376

Gupta, B. K., Sahoo, K. K., Anwar, K., Nongpiur, R. C., Deshmukh, R., Pareek, A., et al. (2021). Silicon nutrition stimulates Salt-Overly Sensitive (SOS) pathway to enhance salinity stress tolerance and yield in rice. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 166, 593–604. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2021.06.010

Hasanuzzaman, M., Bhuyan, M., Parvin, K., Bhuiyan, T. F., Anee, T. I., Nahar, K., et al. (2020). Regulation of ROS metabolism in plants under environmental stress: A review of recent experimental evidence. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 42. doi: 10.3390/ijms21228695

Ji, X. Y., Nie, X. G., Liu, Y. J., Zheng, L., Zhao, H. M., Zhang, B., et al. (2016). A bHLH gene from Tamarix hispida improves abiotic stress tolerance by enhancing osmotic potential and decreasing reactive oxygen species accumulation. Tree Physiol. 36, 193–207. doi: 10.1093/treephys/tpv139

Jung, Y., Kyoo, K. K., Nou, I.-S. (2013). Transgenic Tomato Plants Expressing BrOAT1 gene from Brassica rapa var. SUN-3061 Show Enhanced Tolerance to Salt Stress. Plant Breed. Biotechnol. 1, 70–79. doi: 10.9787/pbb.2013.1.1.070

Khan, I., Khan, S., Zhang, Y., Zhou, J. P., Akhoundian, M., Jan, S. A. (2021). CRISPR-Cas technology based genome editing for modification of salinity stress tolerance responses in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Mol. Biol. Rep. 48, 3605–3615. doi: 10.1007/s11033-021-06375-0

Kishor, P., Hong, Z., Miao, G. H., Hu, C., Verma, D. (1995). Overexpression of [delta]-pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthetase increases proline production and confers osmotolerance in transgenic plants. Plant Physiol. 108, 1387–1394. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.4.1387

Liu, Y., Zheng, Y. Z., Zhang, Y. Q., Wang, W. M., Li, R. H. (2010). Soybean PM2 protein (LEA3) confers the tolerance of escherichia coli and stabilization of enzyme activity under diverse stresses. Curr. Microbiol. 60, 373–378. doi: 10.1007/s00284-009-9552-2

Luo, C. K., Guo, C. M., Wang, W. J., Wang, L. J., Chen, L. (2014). Overexpression of a new stress-repressive gene OsDSR2 encoding a protein with a DUF966 domain increases salt and simulated drought stress sensitivities and reduces ABA sensitivity in rice. Plant Cell Rep. 33, 323–336. doi: 10.1007/s00299-013-1532-0

Lv, P. Y., Wan, J. L., Zhang, C. T., Hina, A., Al Amin, G. M., Begum, N., et al. (2023). Unraveling the diverse roles of neglected genes containing domains of unknown function (DUFs): progress and perspective. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 17. doi: 10.3390/ijms24044187

Moons, A., De Keyser, A., Van Montagu, M. (1997). A group 3 LEA cDNA of rice, responsive to abscisic acid, but not to jasmonic acid, shows variety-specific differences in salt stress response. Gene 191, 197–204. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(97)00059-0

Munns, R. (2002). Comparative physiology of salt and water stress. Plant Cell Environ. 25, 239–250. doi: 10.1046/j.0016-8025.2001.00808.x

Munns, R., Tester, M. (2008). Mechanisms of salinity tolerance. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 59, 651–681. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.59.032607.092911

Panda, D., Mishra, S. S., Behera, P. K. (2021). Drought tolerance in rice: focus on recent mechanisms and approaches. Rice Sci. 28, 119–132. doi: 10.1016/j.rsci.2021.01.002

Qiao, Z. H., Yao, C. T., Sun, S., Zhang, F. W., Yao, X. F., Li, X. D., et al. (2023). Spraying S-ABA can alleviate the growth inhibition of corn (Zea mays L.) under water-deficit stress. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 23, 1222–1234. doi: 10.1007/s42729-022-01116-z

Qiu, Q.-S., Guo, Y., Dietrich, M. A., Schumaker, K. S., Zhu, J.-K. (2002). Regulation of SOS1, a plasma membrane Na+/H+ exchanger in Arabidopsis thaliana, by SOS2 and SOS3. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. United States America 99, 8436–8441. doi: 10.1073/pnas.122224699

Qiu, D., Hu, W., Zhou, Y., Xiao, J., Hu, R., Wei, Q. H., et al. (2021). TaASR1-D confers abiotic stress resistance by affecting ROS accumulation and ABA signalling in transgenic wheat. Plant Biotechnol. J. 19, 1588–1601. doi: 10.1111/pbi.13572

Quan, R. D., Lin, H. X., Mendoza, I., Zhang, Y. G., Cao, W. H., Yang, Y. Q., et al. (2007). SCABP8/CBL10, a putative calcium sensor, interacts with the protein kinase SOS2 to protect Arabidopsis shoots from salt stress. Plant Cell 19, 1415–1431. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.042291

Seok, H. Y., Nguyen, L. V., Nguyen, D. V., Lee, S. Y., Moon, Y. H. (2020). Investigation of a novel salt stress-responsive pathway mediated by arabidopsis DEAD-box RNA helicase gene AtRH17 using RNA-Seq analysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 14. doi: 10.3390/ijms21051595

Serra, T. S., Figueiredo, D. D., Cordeiro, A. M., Almeida, D. M., Lourenço, T., Abreu, I. A., et al. (2013). OsRMC, a negative regulator of salt stress response in rice, is regulated by two AP2/ERF transcription factors. Plant Mol. Biol. 82, 439–455. doi: 10.1007/s11103-013-0073-9

Shen, R. X., Wang, L., Liu, X. P., Wu, J., Jin, W. W., Zhao, X. C., et al. (2017). Genomic structural variation-mediated allelic suppression causes hybrid male sterility in rice. Nat. Commun. 8, 10. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01400-y

Singh, A., Jha, S. K., Bagri, J., Pandey, G. K. (2015). ABA inducible rice protein phosphatase 2C confers ABA insensitivity and abiotic stress tolerance in arabidopsis. PloS One 10, 24. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125168

Steffens, B., Steffen-Heins, A., Sauter, M. (2013). Reactive oxygen species mediate growth and death in submerged plants. Front. Plant Sci. 4. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2013.00179

Stonebloom, S., Ebert, B., Xiong, G. Y., Pattathil, S., Birdseye, D., Lao, J. M., et al. (2016). A DUF-246 family glycosyltransferase-like gene affects male fertility and the biosynthesis of pectic arabinogalactans. BMC Plant Biol. 16, 17. doi: 10.1186/s12870-016-0780-x

Su, L., Zhao, C. Z., Bi, Y. P., Wan, S. B., Xia, H., Wang, X. J. (2011). Isolation and expression analysis of LEA genes in peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.). J. Biosci. 36, 223–228. doi: 10.1007/s12038-011-9058-5

Wan, J. L., Zhang, J., Zan, X. F., Zhu, J. L., Chen, H., Li, X. H., et al. (2023). Overexpression of rice histone H1 gene reduces tolerance to cold and heat stress. Plants-Basel 12, 15. doi: 10.3390/plants12132408

Wang, B. X., Xu, B., Liu, Y., Li, J. F., Sun, Z. G., Chi, M., et al. (2022). A Novel mechanisms of the signaling cascade associated with the SAPK10-bZIP20-NHX1 synergistic interaction to enhance tolerance of plant to abiotic stress in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Plant Sci. 323, 13. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2022.111393

Wang, X., Zhang, M. M., Wang, Y. J., Gao, Y. T., Li, R., Wang, G. F., et al. (2016). The plasma membrane NADPH oxidase OsRbohA plays a crucial role in developmental regulation and drought-stress response in rice. Physiologia Plantarum 156, 421–443. doi: 10.1111/ppl.12389

Xiong, J., Zhang, W. X., Zheng, D., Xiong, H., Feng, X. J., Zhang, X. M., et al. (2022). ZmLBD5 increases drought sensitivity by suppressing ROS accumulation in arabidopsis. Plants-Basel 11, 16. doi: 10.3390/plants11101382

Xu, Y., Yu, Z. P., Zhang, S. Z., Wu, C. A., Yang, G. D., Yan, K., et al. (2019). CYSTM3 negatively regulates salt stress tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant Mol. Biol. 99, 395–406. doi: 10.1007/s11103-019-00825-x

Yang, Z. N., Lu, X. K., Wang, N., Mei, Z. D., Fan, Y. P., Zhang, M. H., et al. (2024). GhVIM28, a negative regulator identified from VIM family genes, positively responds to salt stress in cotton. BMC Plant Biol. 24, 16. doi: 10.1186/s12870-024-05156-8

Yang, R. X., Sun, Z. G., Liu, X. B., Long, X. H., Gao, L. M., Shen, Y. X. (2023). Biomass composite with exogenous organic acid addition supports the growth of sweet sorghum (Sorghum bicolor ‘Dochna’) by reducing salinity and increasing nutrient levels in coastal saline-alkaline soil. Front. Plant Sci. 14. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2023.1163195

Yang, Y., Yoo, C. G., Guo, H. B., Rottmann, W., Winkeler, K. A., Collins, C. M., et al. (2017). Overexpression of a Domain of Unknown Function 266-containing protein results in high cellulose content, reduced recalcitrance, and enhanced plant growth in the bioenergy crop Populus. Biotechnol. Biofuels 10, 13. doi: 10.1186/s13068-017-0760-x

Zhang, Y., Zhang, F., Huang, X. Z. (2019). Characterization of an Arabidopsis thaliana DUF761-containing protein with a potential role in development and defense responses. Theor. Exp. Plant Physiol. 31, 303–316. doi: 10.1007/s40626-019-00146-w

Zhao, C., Zhang, H., Song, C., Zhu, J.-K., Shabala, S. (2020). Mechanisms of plant responses and adaptation to soil salinity. Innovation (Cambridge (Mass.)) 1, 100017. doi: 10.1016/j.xinn.2020.100017

Zhou, J. H., Li, Z. Y., Xiao, G. Q., Zhai, M. J., Pan, X. W., Huang, R. F., et al. (2020). CYP71D8L is a key regulator involved in growth and stress responses by mediating gibberellin homeostasis in rice. J. Exp. Bot. 71, 1160–1170. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erz491

Zhou, C., Sun, Y., Ma, Z., Wang, J. (2015). Heterologous expression of EsSPDS1 in tobacco plants improves drought tolerance with efficient reactive oxygen species scavenging systems. South Afr. J. Bot. 96, 19–28. doi: 10.1016/j.sajb.2014.10.008

Zhu, J.-K. (2002). Salt and drought stress signal transduction in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 53, 247–273. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.53.091401.143329

Keywords: OsDUF868.12, rice, abiotic stresses, oxidative stress, physiological and biochemical index

Citation: Chen H, Wan J, Zhu J, Wang Z, Mao C, Xu W, Yang J, Kong Y, Zan X, Chen R, Zhu J, Xu Z and Li L (2025) Overexpression of OsDUF868.12 enhances salt tolerance in rice. Front. Plant Sci. 16:1458467. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2025.1458467

Received: 02 July 2024; Accepted: 06 January 2025;

Published: 29 January 2025.

Edited by:

Weiqiang Li, Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), ChinaReviewed by:

Fei Chen, Hangzhou Normal University, ChinaCopyright © 2025 Chen, Wan, Zhu, Wang, Mao, Xu, Yang, Kong, Zan, Chen, Zhu, Xu and Li. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lihua Li, bGlsaWh1YTE5NzZAc2ljYXUuZWR1LmNu

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.