- 1School of Life Science and Engineering, Lanzhou University of Technology, Lanzhou, China

- 2College of Mathematics and Natural Science, The Copperbelt University, Kitwe, Zambia

Potato (Solanum tuberosum) is the fourth largest staple food crop globally. However, potato cultivation is frequently challenged by various diseases during planting, significantly impacting both crop quality and yield. Pathogenic microorganisms must first breach the plant’s cell wall to successfully infect potato plants. Cellulose, a polysaccharide carbohydrate, constitutes a significant component of plant cell walls. Within these walls, cellulose synthase (CesA) plays a pivotal role in cellulose synthesis. Despite its importance, studies on StCesAs (the CesA genes in potato) have been limited. In this study, eight CesA genes were identified and designated as StCesA1-8, building upon the previous nomenclature (StCesA1-4). Based on their phylogenetic relationship with Arabidopsis thaliana, these genes were categorized into four clusters (CesA I to CesA IV). The genomic distribution of StCesAs spans seven chromosomes. Gene structure analysis revealed that StCesAs consist of 12 to 14 exons. Notably, the putative promoter regions harbor numerous biologically functional cis-acting regulatory elements, suggesting diverse roles for StCesAs in potato growth and development. RNA-seq data further demonstrated distinct expression patterns of StCesAs across different tissues. Additionally, quantitative real-time PCR (QRT-PCR) results indicated significant up-regulation of StCesA5 expression under biotic stresses, implicating its potential involvement in potato disease resistance.

1 Introduction

Plant cell wall is a thin, solid and flexible outer cell layer composed of cellulose microfibrils (CMFs) (Cosgrove, 2005), which is known as the ‘first line of defense’ against most pathogenic bacteria in plants. As an important component of plant cell wall, cellulose usually exists in the form of CMFs. The basic structural unit of cellulose is D-glucopyranose, which is linked by β-1,4 glycosidic bonds. Cellulose biosynthesis occurs at the plasma membrane. Cellulose synthase complexes (CSCs), a rosette shaped (Doblin et al., 2002), hexamer complex typically composed of 18-36 individual cellulose synthase subunits, synthesize β-1, 4-glucan chains using UDP-glucose as substrate to regulate cellulose synthesis (Perrin, 2001; Peng et al., 2002).

CesA gene is a gene encoding the catalytic subunit of CSCs, belonging to the GT-A protein family (Liu and Mushegian, 2003). The length of this gene family is generally about 1000bp. The earliest reports of CesA genes date back to 1991 and 1995, with the discovery of two CesA genes in Acetobacter xylinus (Saxena et al., 1991; Saxena and Brown, 1995). Subsequently (Pear et al., 1996), identified two cDNA clones in Gossypium hirsutum and one in Oryza sativa, marking a significant milestone in plant CesA gene research.

Currently, CesA gene family members have been identified in various plants, including 10 CesA genes in Arabidopsis thaliana (Richmond and Somerville, 2000), 12 in Zea mays (Appenzeller et al., 2004), 16 in Solanum lycopersicum (Song et al., 2019), 26 in Glycine max (Nawaz et al., 2017), etc. In Arabidopsis thaliana, AtCesA4 (IRX5), AtCesA7 (IRX3) and AtCesA8 (IRX1) are related to the formation of secondary wall (Taylor et al., 2003), while AtCesA1 (rsw1), AtCesA3 (ixr1) and AtCesA6 (prc1) are associated with the primary wall formation (Persson et al., 2007). Additionally, the cellulose synthase interacting protein 1 (CSI1) has been shown to interact with AtCesA1 and AtCesA6 (Gu et al., 2010), and is highly co-expressed with AtCesAs related to the primary wall in Arabidopsis (Zhang and Zhou, 2015). In tomato, the HEL gene, homologous to CSI1, interacts with CesA and influences the spiral growth of the plant (Yang et al., 2020). In rice (Tanaka et al., 2003), identified OsCesA4, OsCesA7 and OsCesA9 as related to rice secondary wall synthesis through the phylogenetic tree. The insertion of the endogenous retrotransposon Tos17 revealed that the fragile stem phenotype in rice may be attributed to defects in the secondary wall.

The potato, a staple crop originating from the Andean region, is now widely cultivated with China leading global production (Devaux et al., 2021). Among the various diseases affecting potatoes, late blight, caused by Phytophthora infestans, is particularly devastating, often resulting in significant yield losses (Dong and Zhou, 2022). Varieties like ‘Shepody’, ‘Atlantic’, and ‘Favorita’ are highly susceptible, with disease rates soaring above 80% under favorable conditions for the pathogen (Duan et al., 2021). The CesA gene plays a crucial role in plant growth and cellulose synthesis, and its variants in potatoes, known as StCesAs, are of particular interest. Research indicates that certain CesA genes may be involved in susceptibility to late blight (Sun et al., 2016). Therefore, investigating the StCesA gene family in potatoes using bioinformatics could unveil their functions and potentially reveal targets for enhancing resistance to late blight. This is vital as breeding for resistance often incorporates resistance genes against P. infestans (Rpi genes) from wild relatives, which can be expedited through genetic engineering for durable, broad-spectrum resistance (Paluchowska et al., 2022). Understanding the StCesA genes’ involvement in late blight could lead to more resilient potato cultivars, addressing a major agricultural challenge.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Plant materials and treatments

The potato hybrid resistant cultivar ‘Longshu 10’ was subjected to a biotic stress experiment using the oomycete pathogen Phytophthora infestans, the causative agent of late blight. The plant were cultured in the Plant Tissue Culture Laboratory of Lanzhou University of Technology. Tubers of uniform size were selected for growth buried in pots 20 cm in diameter, with a nutrient soil to vermiculite ratio of 3:2, a light/dark cycle of 16/8 h, a day/night temperature of 23 ± 2°C, and weekly watered. After approximately 4 months, potato plants with similar growth were selected, and the fourth and fifth compound leaves below the apical leaves were removed for leaf inoculation in vitro. The leaves were uniformly sprayed with spore suspension of P. infestans at a concentration of 1×105 cells/mL, while the control group received sterile water instead. The inoculated leaves were located at 18 to 20°C and 100% humidity. Samples were collected at 0, 24, 48, and 72 hours post-inoculation to assess the expression patterns of StCesA genes under this specific biotic stress condition. Three biological replicates were performed at each time point to ensure statistical validity. The samples were promptly frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until further analysis.

2.2 RNA isolation, cDNA synthesis, and qRT-PCR

Total RNA of leaves was extracted using TRIzol Reagent (Sangon Biotech, China), and the operation procedure was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol. After the extraction, first-strand cDNA was synthesized from 2μg of total RNA using PrimeScript™ RT Master Mix (Perfect Real Time)(Takara, Japan). Specific primers were designed using Primer Premier 5 (Singh et al., 1998) and synthesized commercially (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China). StEF-1α (LOC102600998) was used as the reference gene for qRT-PCR in a 10μL master mix: 5 µL of 2×TB Green Premix Ex Taq II (Tli Rnase H Plus) (Takara, Japan), 1 µL of the template, 3.6 µL of ddH2O, and 0.2 µl (10μM) of each primer. The qRT-PCR program was: (і) predenaturation at 95°C for 2min, (ii) 40 cycles of amplification: denaturation at 95°C for 5s, annealing at 55°C for 30s, extension at 72°C for 1min, and (iii) extension at 72°C for 10min. The expression levels of genes were analyzed using the 2−ΔΔCT method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001). SPSS was used to analyze the results for significant differences, and the relative gene expression levels were visualized by GraphPad Prism 9.

2.3 Identification of CesA gene family in potato

Sequence files and other related information (Hardigan et al., 2016) of the doubled monoploid (DM) S. tuberosum were obtained from PGSC (http://spuddb.uga.edu/). Sequence of AtCesAs were from TAIR (https://www.arabidopsis.org/). The Hidden Markov Models (HMMs) of Cellulose_synt and zf - UDP (PF03552 and PF14569) were downloaded from Pfam (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro/entry/pfam/) to identify StCesAs. Firstly, PF03552 and PF14569 were used as templates to search the potato protein sequence (E-value ≤ 1e-5) by HMMER v3.4 (http://hmmer.org/), and the candidate members of StCesA gene family were obtained, which were recorded as G1. Then, 10 known AtCesA protein sequences were used for BLAST alignment in the potato genome database (E-value ≤ 1e-5), and the obtained genes were recorded as G2. The genes of G1 and G2 were merged and compared, then duplicate genes were deleted. Finally using NCBI-CDD (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/bwrpsb/bwrpsb.cgi) and SMART (http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/) to eliminate the sequences without typical domain of CesA proteins. Eight StCesA gene family members were finally determined and named as StCesA1-StCesA8 on the basis of retaining the original gene names (Oomen et al., 2004).

2.4 Phylogenetic analysis of the CesA family genes in potato

The 10 known AtCesA protein sequences and the above 8 StCesA protein sequences were aligned by the ClustalW algorithm in MEGA v11.0.13 (Tamura et al., 2021) (https://www.megasoftware.net/) and the NJ (Neighbor-Joining) tree was constructed. The test of phylogeny is bootstrap method and 1000 bootstrap replications were chosen. The phylogenetic tree was generated using iTOL v6.9 (Letunic and Bork, 2024) (https://itol.embl.de/) online server.

2.5 Gene structure, motif distribution, and sequence analysis

In order to analyze the gene structures, the online website GSDS 2.0 (Hu et al., 2015) (http://gsds.gao-lab.org/) was used to analyze the gene structures of StCesAs according to the CDS sequence and genome sequence, and the gene structure map was drawn. To analyze motifs, use MEME v5.5.4 (Bailey et al., 2015) (https://meme-suite.org/meme/tools/meme) to predict the motifs of StCesA proteins, the number of motifs is set to 10, the rest of the parameters of the same by default. For understanding physical and chemical properties of StCesA proteins, using Expasy ProtParam tool (https://web.expasy.org/protparam/) to predict relative molecular weight, isoelectric point, hydrophilicity, and other characteristics.

2.6 Chromosomal distribution, prediction of subcellular localization, and synteny visualization

In order to understand the distributions of StCesAs on chromosomes, the MG2C-2.1 tool (Chao et al., 2021) (http://mg2c.iask.in/mg2c_v2.1/) was used to map the location of StCesA genes on chromosomes according to the annotation file. For predicting the probable subcellular locations of StCesA proteins, we used WoLF PSORT program (Horton et al., 2007) (https://www.genscript.com/wolf-psort.html). Synteny analysis of the CesA genes in Arabidopsis, potato and tomato was performed to determine the synteny relationship between them. The figure was generated using the MCScanX algorithm and the Dual Synteny Plot program of TBtools (Chen et al., 2023).

2.7 Gene ontology enrichment and analysis of cis-acting regulatory elements in promoter regions

GO (Gene Ontology) enrichment of StCesA protein sequence was performed by STRING (https://cn.string-db.org/).The 2000 bp sequences upstream of the transcription start site of each StCesA gene were selected as promoter sequences and submitted to PlantCARE (Lescot et al., 2002) (https://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcare/html/) to predict cis-acting regulatory elements with biological functions. The analysis results were visualized using the ‘ggplot2’ package in R.

2.8 In-slico expression of StCesAs in different tissues

The RNA-seq data of different tissues was derived from PGSC database (NCBI accession: SRA030516) (Potato Genome Sequencing et al., 2011). The gene IDs of StCesAs were retrieved from the database, and the FPKM(Fragments Per Kilobase of exon model per Million mapped fragments) (Mortazavi et al., 2008) values of leaves, roots, flowers, petals, buds, sepals, stolons and petioles were retrieved. The FPKM values were log10 transformed, and the heat map of relative gene expression level was generated by R.

3 Results

3.1 Identification of CesA gene family in potato

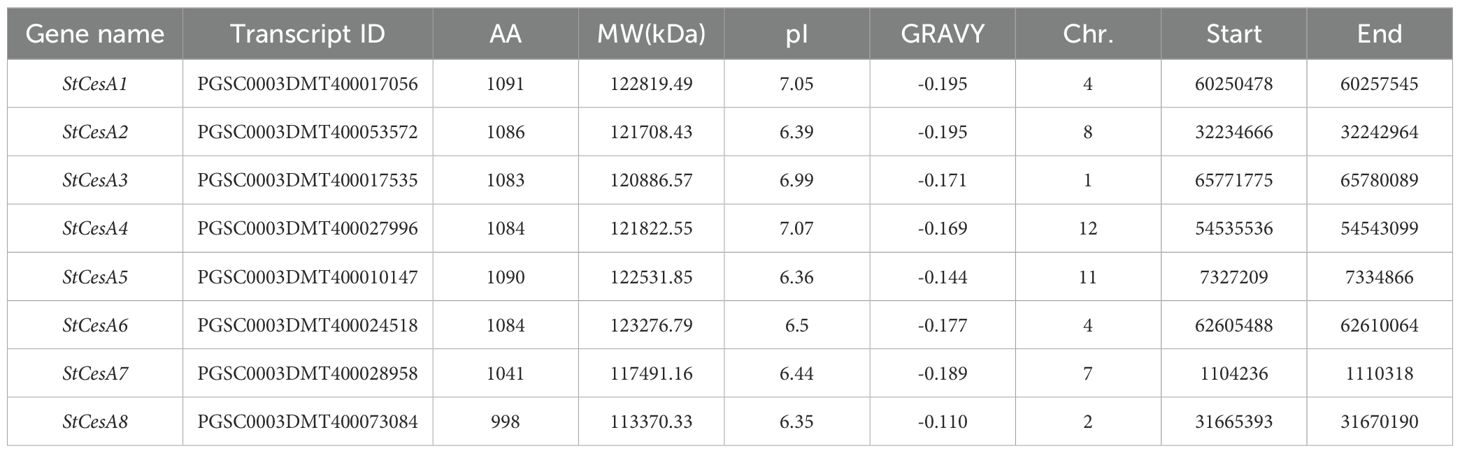

A total of 8 CesA genes were identified in potato. Information on StCesA proteins and their physical and chemical properties (Table 1) indicates that StCesA family members encode proteins with amino acid lengths ranging from 998 to 1091 aa. The minimum molecular weight (MW) is 113.37kDa and the maximum is 123.28kDa. The theoretical isoelectric point (pI) ranges from 6.35 to 7.07. The grand average of hydropathicity score (GRAVY) is between -0.195 and -0.110, indicating that the proteins are hydrophilic. Subcellular localization prediction results showed that StCesA proteins were all expressed on the plasma membrane.

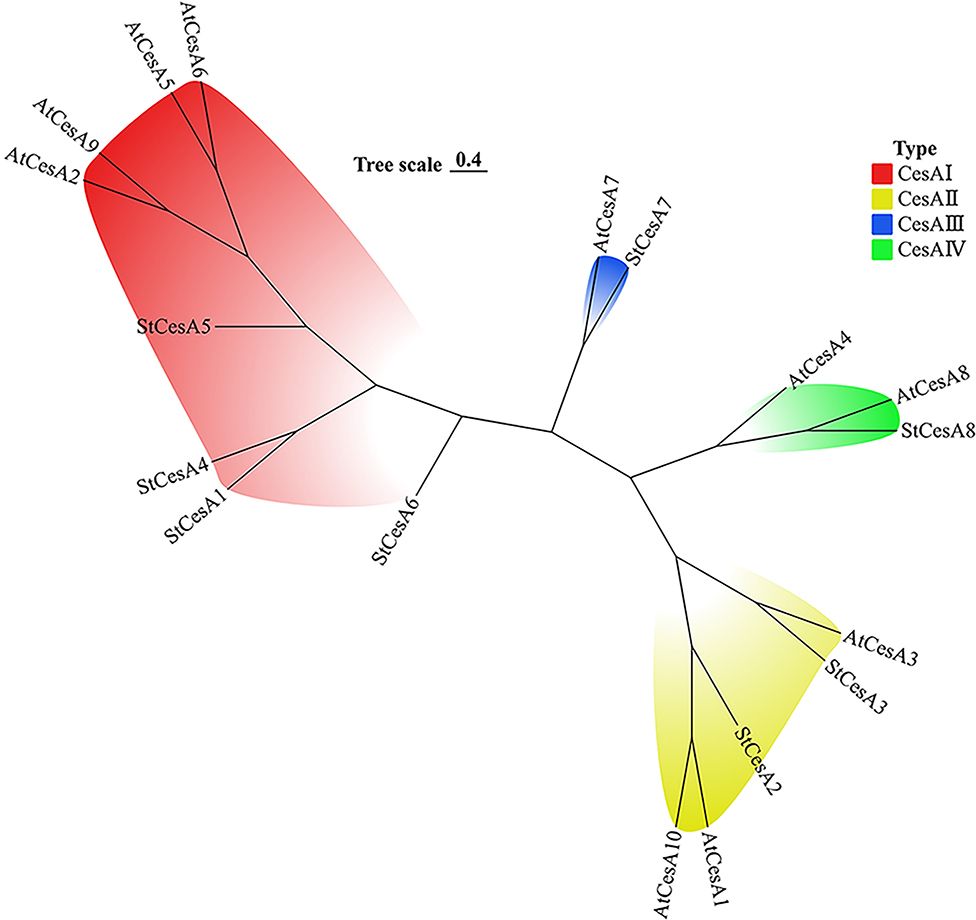

3.2 Phylogenetic analysis

The phylogenetic tree was constructed by multiple comparison of 10 AtCesAs and 8 StCesAs. CesA gene family members are divided into 4 clusters (Figure 1): CesA I cluster contains 4 StCesAs and 4 AtCesAs, CesA II cluster contains 2 StCesAs and 3 AtCesAs, and CesA III cluster contains 1 StCesA and 1 AtCesA. The CesA IV cluster contains 1 StCesA and 2 AtCesAs.

3.3 Gene structure and motif distribution of StCesAs

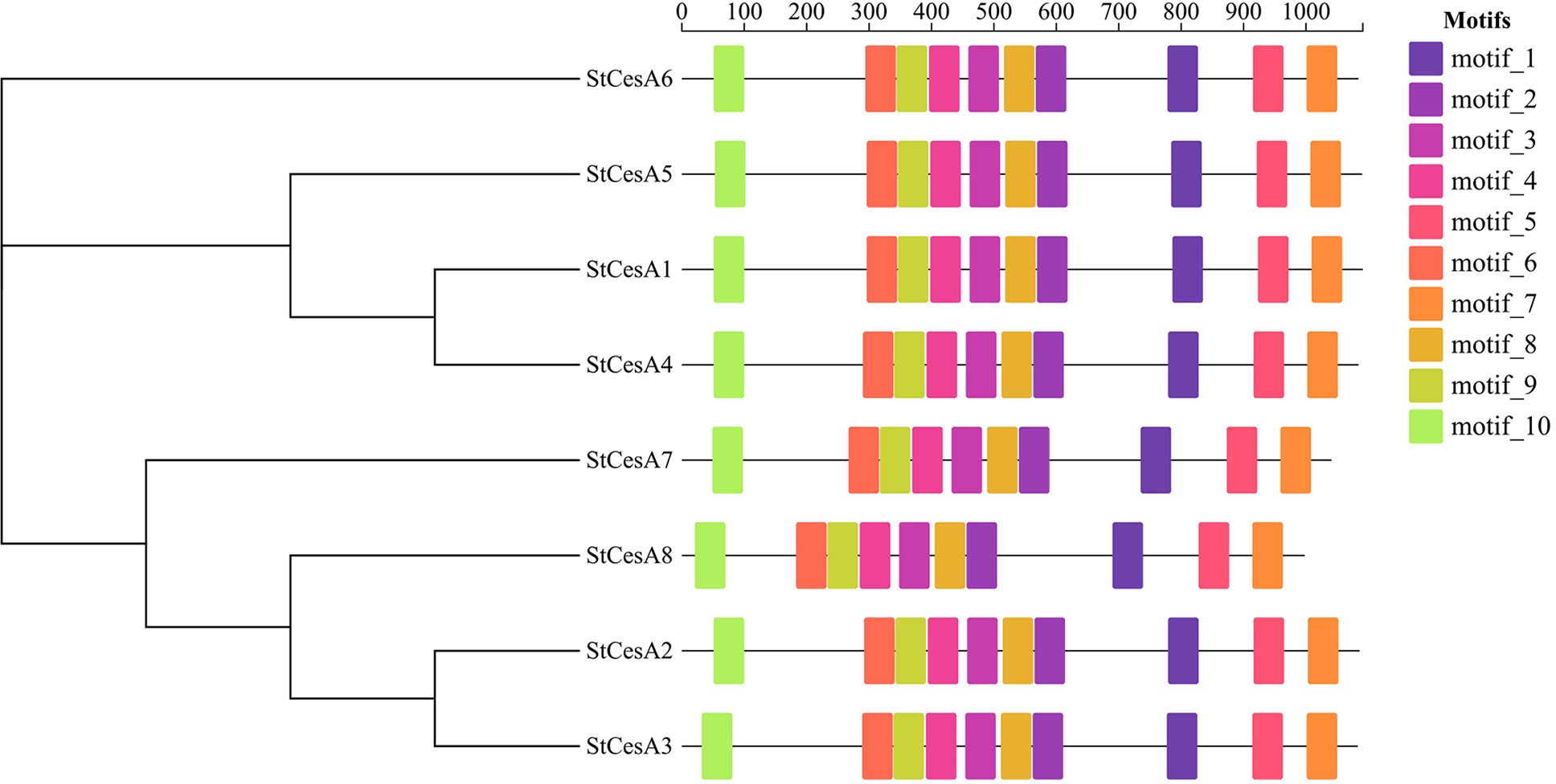

By analyzing the structures of StCesAs through GSDS online server, the distributions of exons and introns of StCesAs was determined. There is no significant difference in the number of exons and introns of StCesAs. StCesA1 and StCesA4 contain 13 exons and 12 introns, followed by StCesA2, StCesA3, StCesA5 and StCesA6 contain 14 exons and 13 introns. StCesA7 and StCesA8 contain 12 exons and 11 introns (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Exon-intron structures of 8 StCesAs genes. The blue boxes indicate exons, dashed lines indicate introns, and upstream or downstream regions are indicated by red boxes.

In order to further explore the structures and functions of StCesA proteins, 10 motifs were predicted using MEME Suite online server, and they were found to have a relatively consistent arrangement and distribution (Figure 3), indicating a relatively close relationship, which is helpful to study the evolutionary link between CesA proteins.

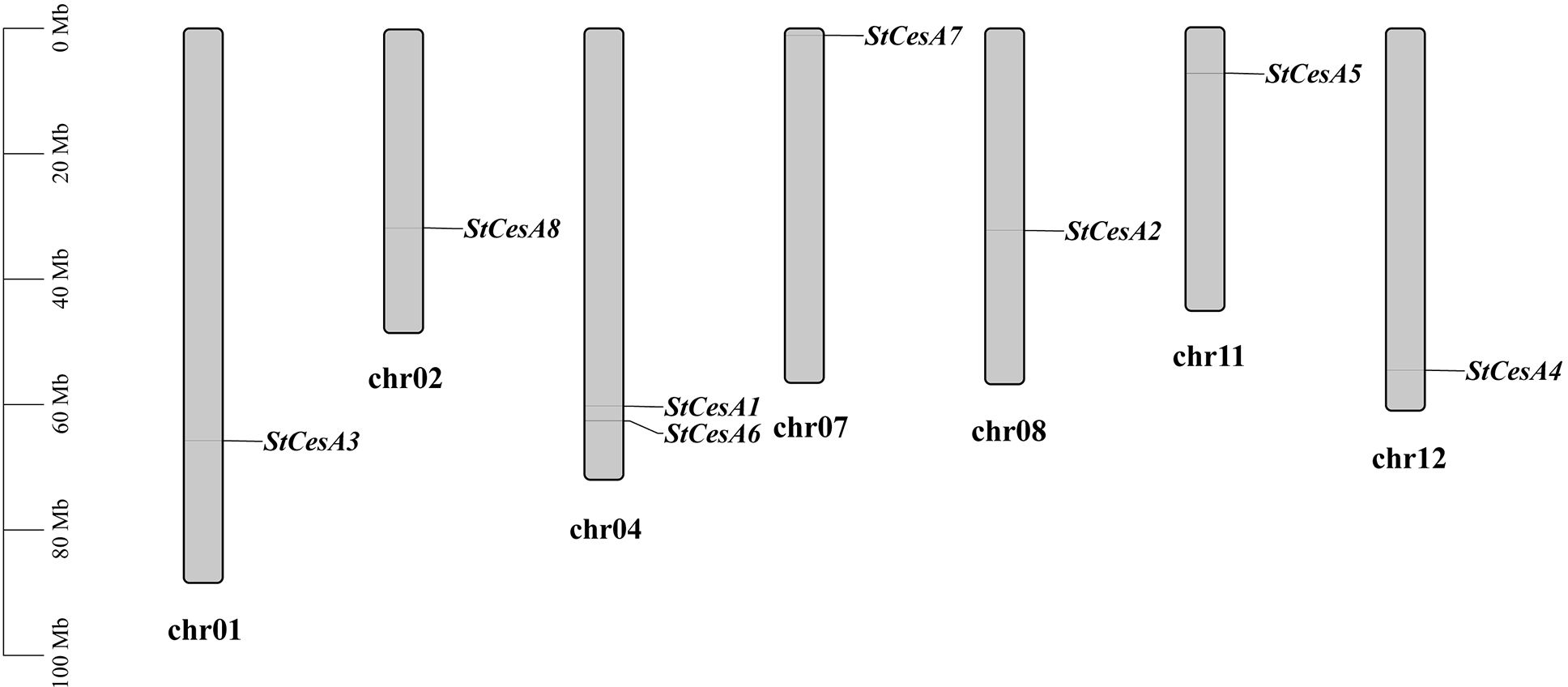

3.4 Chromosomal distribution and synteny analysis

Eight StCesAs were scattered on chr1, chr2, chr4, chr7, chr8, chr11 and chr12 (Figure 4). There are two on chr4 but none on chr3, chr5, chr6, chr9, and chr10. In plant genome evolution, tandem and segmental duplications contribute to the expansion of gene families with new members and new functions (Bano et al., 2021b). Intraspecies synteny analysis showed that StCesA1 and StCesA4 have a segmental duplication (Figure 5A). Interspecies synteny analysis was performed between Arabidopsis and potato and there is a gene duplication (AT4G18780 and StCesA8). Synteny analysis was also performed between the potato genome and the genome of tomato, a plant from the same family (Figure 5B), because late blight occurs mostly in them. A total of 10 homologous gene pairs were found between StCesAs and SlCesAs (both StCesA1 and StCesA4 were homologous to Solyc12g056580.2.1 and Solyc04g071650.3.1). The structures and functions of StCesAs and SlCesAs may be highly similar, which provides a new direction for further studying the functions of cellulose synthase genes in potato and tomato.

Figure 5. (A) Duplicate events of the CesA genes in the potato genome. (B) Synteny analysis of CesA genes between A thaliana, S. tuberosum and S. lycopersicum. Collinear blocks are shown with grey and the collinear CesA genes between species are represented by blue lines.

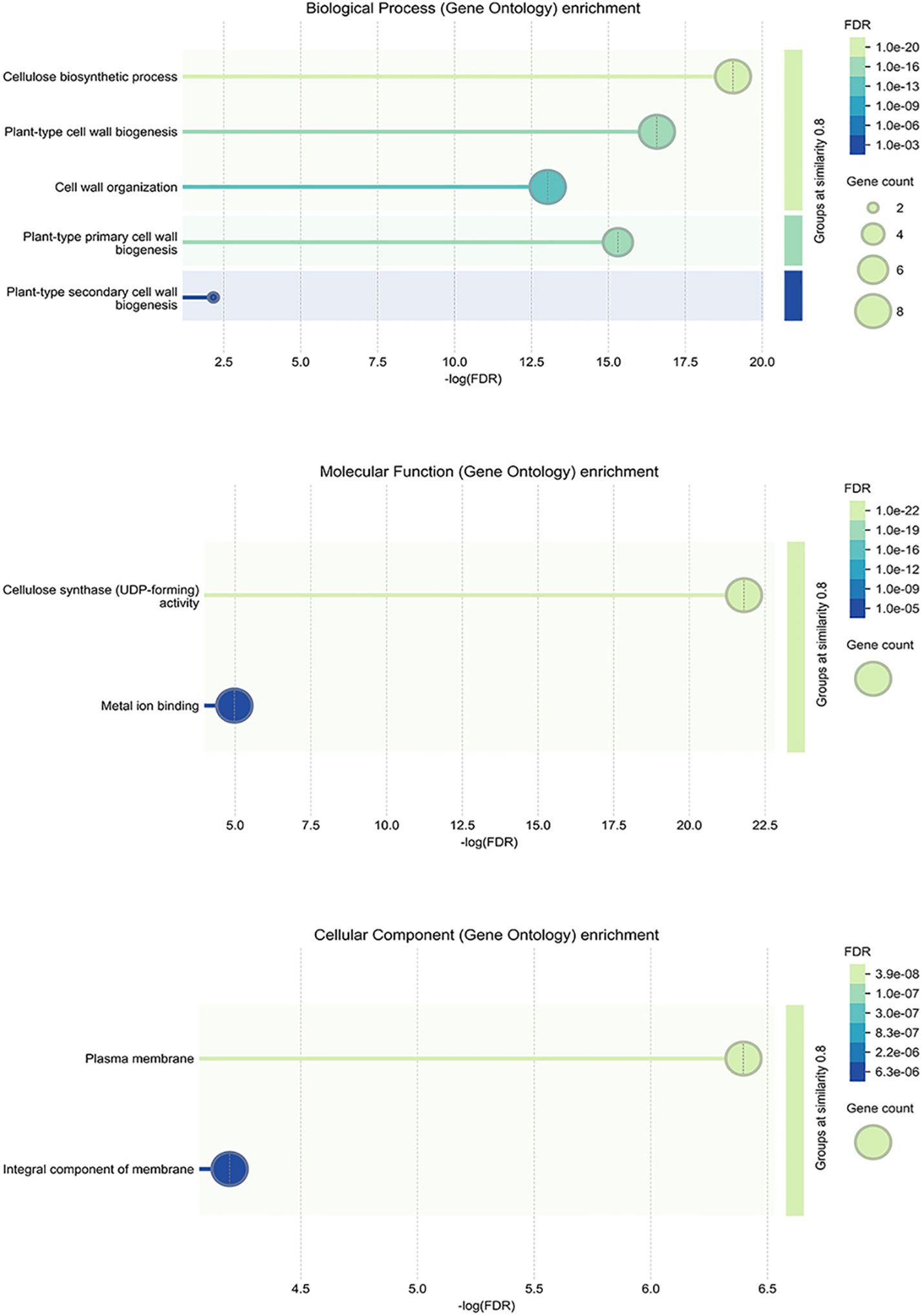

3.5 Gene ontology enrichment of StCesA genes

GO enrichment pathway analysis was performed from three aspects (Figure 6). The results suggest that StCesA genes play a number of important functions in potato. In the Biological Process, most StCesA genes play a role in cellulose biosynthetic, plant-type cell wall biogenesis, etc. In the Molecular Function, in addition to their cellulose synthase (UDP-forming) activity, they also involve in metal ion binding, which is worth noting. In the Cellular Component, all members are inseparable from the membrane.

Figure 6. GO enrichment analysis of StCesA genes in S. tuberosum. It contains three parts: biological process, molecular function and cellular component.

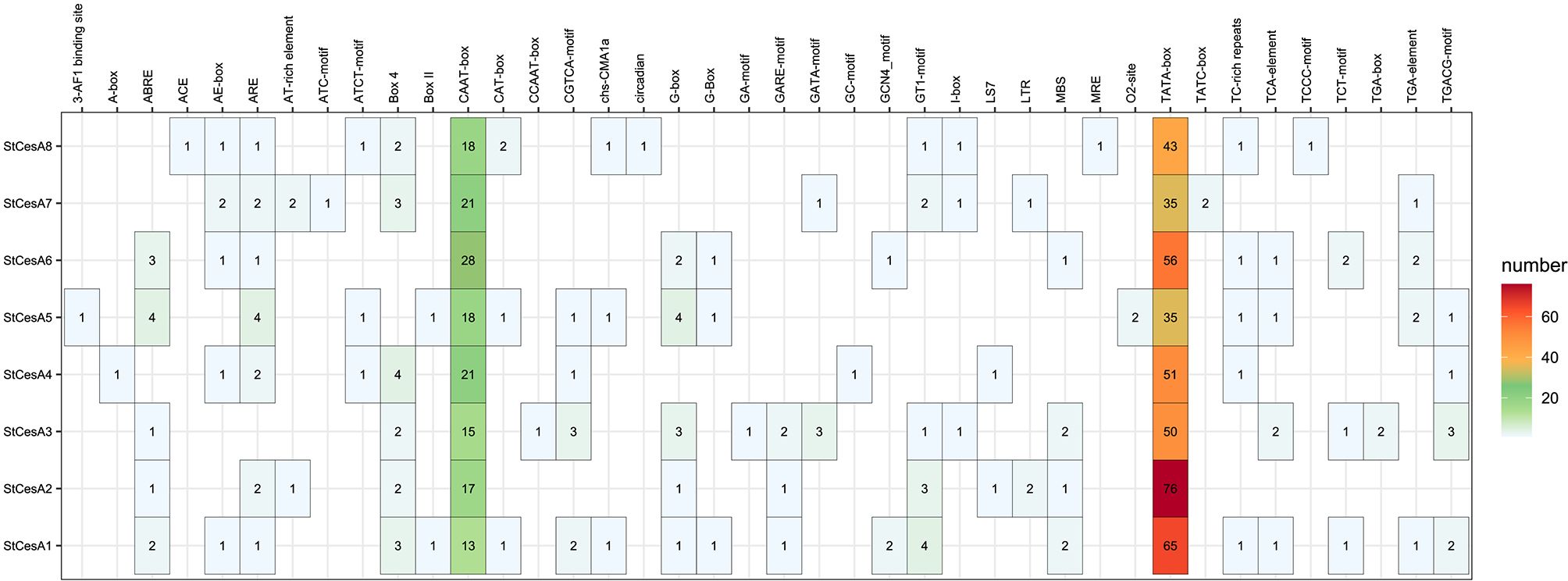

3.6 Analysis of cis-acting regulatory elements in promoter regions

We identified 40 different cis-acting regulatory elements in the promoter regions of the StCesAs (Figure 7). In addition to the common CAAT-box and TATA-box, the cis-acting regulatory elements of StCesAs also include abscisic acid response elements (ABRE), methyl jasmonate response elements (CGTCA-motif, TGACG-motif), light signal response elements (G-box, Box 4, GT1-motif), antioxidant response elements (ARE), etc. In addition, there are TC-rich repeats, which are elements involved in disease resistance and stress response. To sum up, StCesAs play an important role in potato growth under both abiotic and biotic stress.

3.7 In-slico expression of StCesAs in different tissues

In order to understand the expression pattern of StCesAs in different tissues, RNA-Seq data of leaf, root, flower, petal, bud, sepal, stolon, and petiole was downloaded from the potato transcriptome database. The results were visualized using the ‘ggplot2’ package in R (Figure 8). The expression of StCesA2 was the highest in all eight tissues, while StCesA6 was only weakly expressed in stolons and petals, and StCesA8 was not expressed in petals. By analyzing the expression levels of each member, the expression levels of StCesA1 and StCesA2 were the highest in petioles, StCesA3, StCesA7 and StCesA8 were the highest in stolons, StCesA4 and StCesA6 were the highest in petals, and StCesA5 was the highest in flowers.

Figure 8. In-silico expression analysis of StCesAs in 8 tissues of S. tuberosum. The relative expression levels of 8 StCesAs are standardized by transforming to Log2 format.

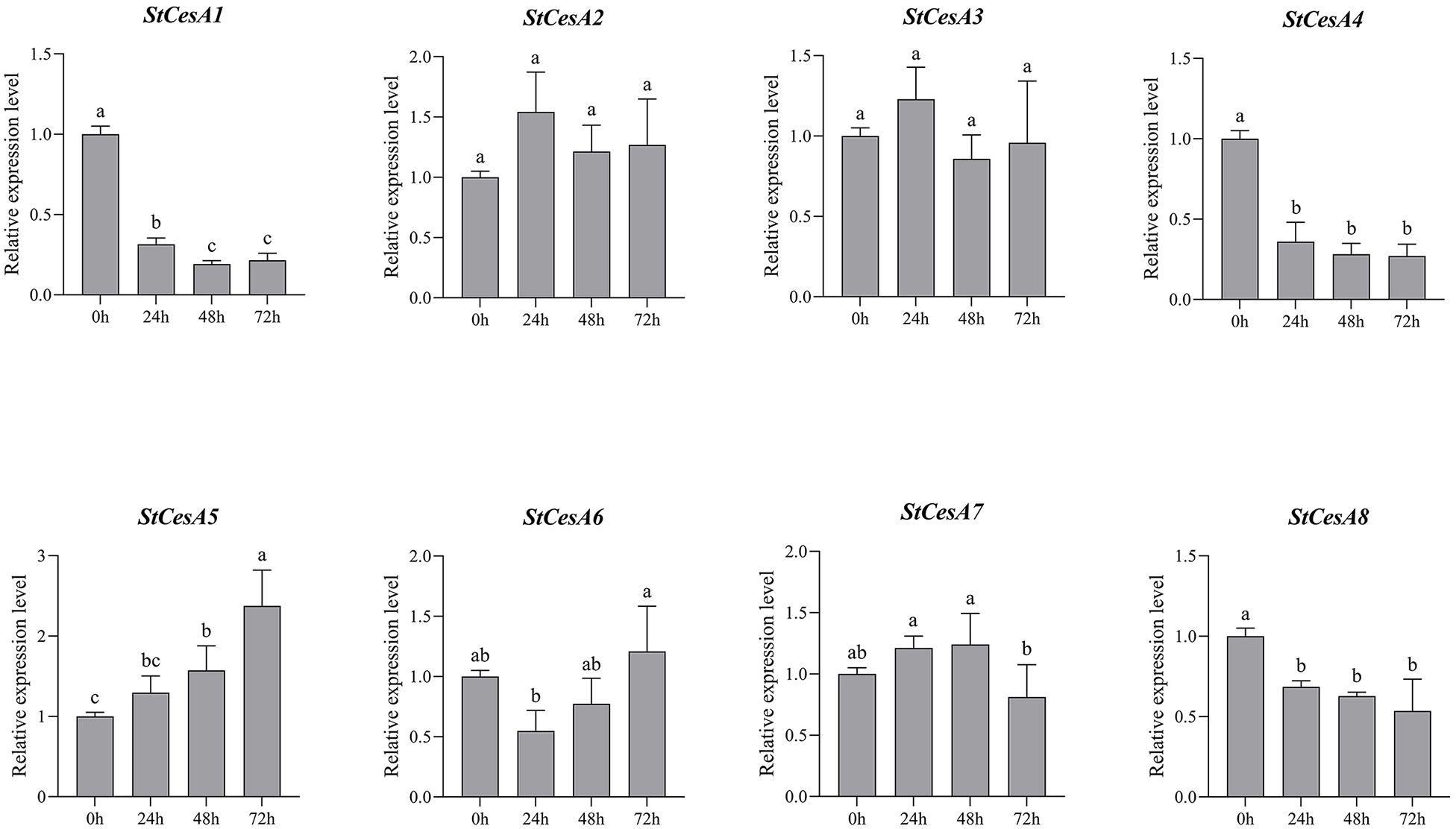

3.8 Expression patterns of StCesA genes in response to biotic stress

To understand the changes in the relative expression of StCesAs (0h, 24h, 48h and 72h) in potato leaves infected by P. infestans, we performed qRT-PCR analysis of 8 StCesA genes (Figure 9). For ‘Longshu 10’, 72h after infection, the relative expression level of StCesA1, StCesA4, StCesA5 and StCesA8 changed significantly, while StCesA2, StCesA3, StCesA4 and StCesA6 showed no significant change. 0~24h, the relative expression level of StCesA1、4、8 was significantly downregulated; 24~48h, only StCesA1 was significantly downregulated;48~72h, StCesA5 was highly upregulated, but the relative expression level of StCesA7 was significantly downregulated. Overall, the relative expression level of StCesA5 increased with time after stress. At the same time, there was no significant difference between the relative expression level of StCesA2 and StCesA3. The pattern of changes in the relative expression level of StCesA1 and StCesA4 after stress was the same, which is another strong evidence of their high homology.

Figure 9. Relative expression levels of 8 StCesA genes in S. tuberosum under P. infestans stress. Data are expressed as mean ±SEM. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences at different time points (p < 0.05).

4 Discussions

Cellulose is one of the important components of the plant cell wall, and its biosynthesis is mainly related to cellulose synthase (CesA), KORRIGAN (KOR) (Zuo et al., 2000), sucrose synthase (SuSy) (Cardini et al., 1955) and other enzymes involved in the process. Since the first CesA gene was reported, CesA genes have been identified in many plants such as Arabidopsis thaliana, tobacco, tomato, barley, and maize (Richmond and Somerville, 2000; Appenzeller et al., 2004; Burton et al., 2008; Song et al., 2019). These studies contribute to our understanding of the structure, function, and evolution of the CesA gene family in plants. The continuous updates to the potato genome database have facilitated the study of gene families with specific functions. In this study, we identified eight CesA family members in potato, laying the foundation for future functional analyses of these genes.

The amino acid sequence length of each StCesA protein was similar, about 1000 aa (Table 1). There were no significant differences in physicochemical properties such as MW, pI, and GRAVY between them, indicating no high variation among StCesAs. In order to understand the possible interaction between StCesA protein and plant system, the subcellular localizations of StCesA proteins were predicted. The results showed that all StCesA proteins were localized on the plasma membrane, confirming their “frontier” positions in biotic and abiotic stresses. Our findings correlates with the results from similar studies in other plant species. For instance, research on maize has identified distinct CesA cDNAs and has shown that CesA genes are expressed in various organs, with some genes being specific to certain cell types involved in primary or secondary wall synthesis (Holland et al., 2000). This suggests that while there may be a conserved core function among CesA genes, their expression patterns and roles can vary significantly between species. As AtCesA1, AtCesA3, AtCesA6 were associated with the formation of the primary wall, and AtCesA4, AtCesA7, AtCesA8 were related to the formation of the secondary wall. We speculate that StCesA2 and StCesA3 are related to the formation of the potato primary wall. In contrast, StCesA7 and StCesA8 are associated with the formation of the potato secondary wall, and the results need to be verified by experiments.Moreover, studies on sweet potato have revealed that sucrose synthase genes, which are part of a different but related gene family, undergo segmental and tandem duplications during evolution and are highly expressed in sink organs (Zhou et al., 2024).

StCesA genes have 12~14 exons and encode proteins of 998~1091 aa in length (Figure 2), while AtCesA genes have 10~14 exons and encode proteins of 985~1088 aa. Introns play important functions in the evolution of some plant species (Roy and Gilbert, 2006). In the evolutionary analysis of CesA genes, the exon-intron structure distribution of StCesA genes and AtCesA genes is similar, most of the genes were highly conserved during evolution, and the introns of these genes were not lost during evolution, while the introns of some other genes would be lost over evolutionary time (Bano et al., 2021a). In general, the genomes of more advanced species comprise fewer introns (Roy and Gilbert, 2005). These results indicate that the CesAs gene structure is evolutionarily conserved in higher plants.

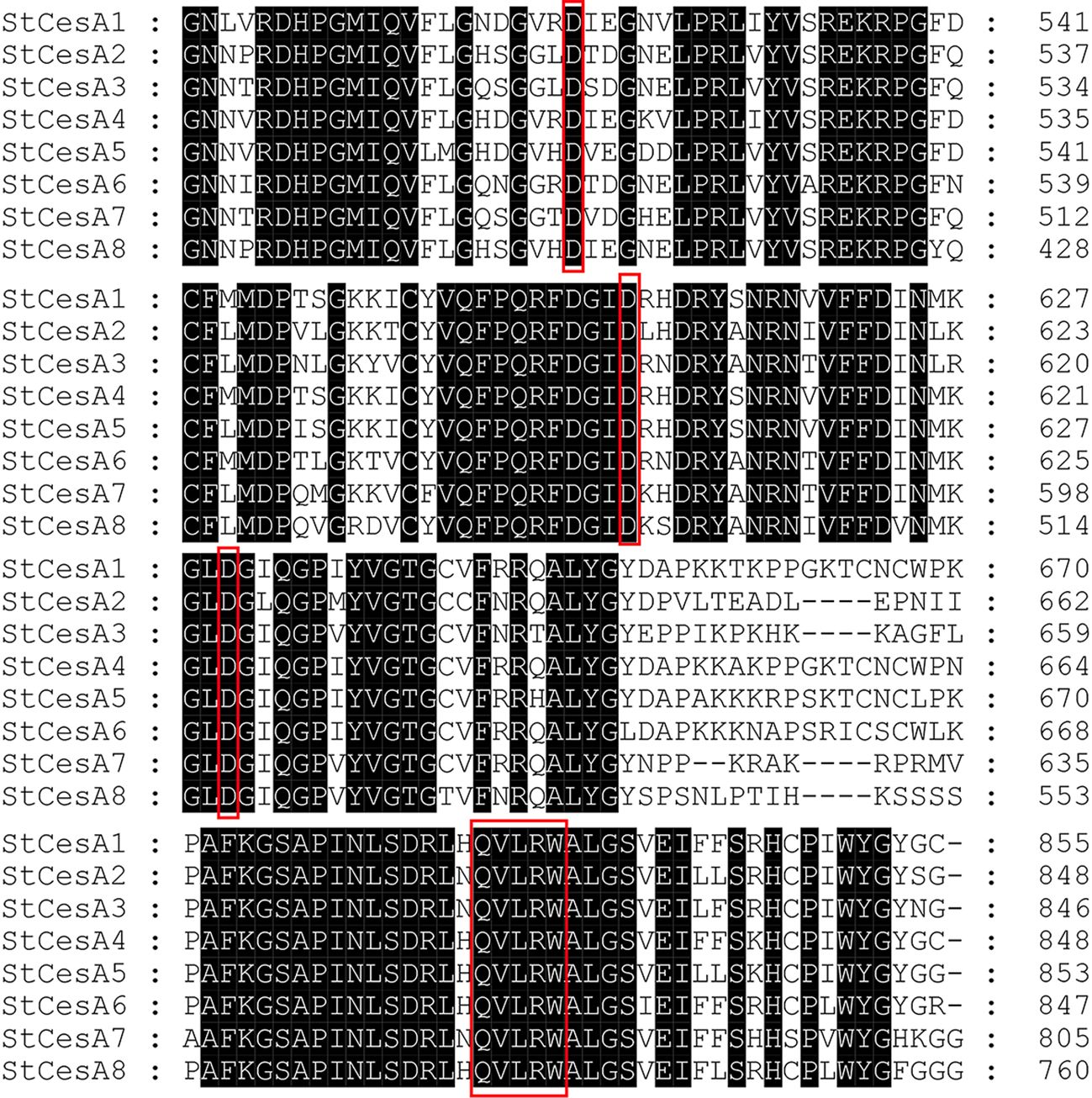

CesA proteins in plants have eight transmembrane domains, two located near the N-terminal, and the other six clustered near the C-terminal. The middle region is a hydrophilic intracellular region, and there is a conserved structure of “D, D, D, QXXRW” in this region (Figure 10), which is closely related to the catalytic activity, as is StCesA proteins. Each member of the CesA family has a cysteine-rich, conserved CXXC domain at the N-terminus, which can fold into a zinc finger or LIM transcription factor conformation (Baltz et al., 1992)—starting from amino acids 10 to 40 at the N-terminal. Its base sequence for CX2CX12FXACX2CX2PXCX2CXEX5GX3CX2C (Somerville, 2006). When the oxidation condition of zinc finger domain is changed, the stability of CSC may be destroyed and the synthesis of crystalline cellulose may be inhibited (Kurek et al., 2002).

Figure 10. Amino acid sequence alignment of StCesA gene family proteins. The black parts represent the identical amino acid residues. The red boxes represent the typical “D, D, D, QXXRW” conserved domain of the CesA gene family.

Potato and tomato are of the same family and have high homology. According to the localization of genes on chromosomes and synteny analysis, chromosome rearrangements exist in the genome differentiation of potato and tomato. The physical map showed that the StCesA gene also rearranged with chromosomes, and the CesA gene family had exemplary conservation in potato and tomato genomes.

Analysis of cis-regulatory regulatory elements of the promoter sequence (2000bp) of members of the StCesA family (Figure 7) revealed that all members contain multiple cis-acting regulatory elements in response to adversity stress. Biotic and abiotic stress can stimulate the synthesis of methyl jasmonate and ethylene, thereby inducing the expression of genes involved in stress response and enhancing defense response. AtCesA3 deletion mutants have constitutive expression of stress response genes, increase methyl jasmonate and ethylene synthesis, and to improve resistance to fungal pathogens (Ellis et al., 2002). StCesA1, StCesA3, StCesA4, and StCesA5 have elements in response to methyl jasmonate, and it is speculated that they may participate in the reaction regulated by methyl jasmonate. It has been shown that altering the integrity of the secondary wall by inhibiting cellulose synthesis leads to the specific activation of new defense pathways, thereby creating an antimicrobial-enriched environment (e.g., peptides, PR proteins, and secondary metabolites) that is harmful to pathogens (Hernandez-Blanco et al., 2007). In addition, the promoters of all StCesA genes contain elements related to light response, suggesting that light may induce StCesA gene expression.

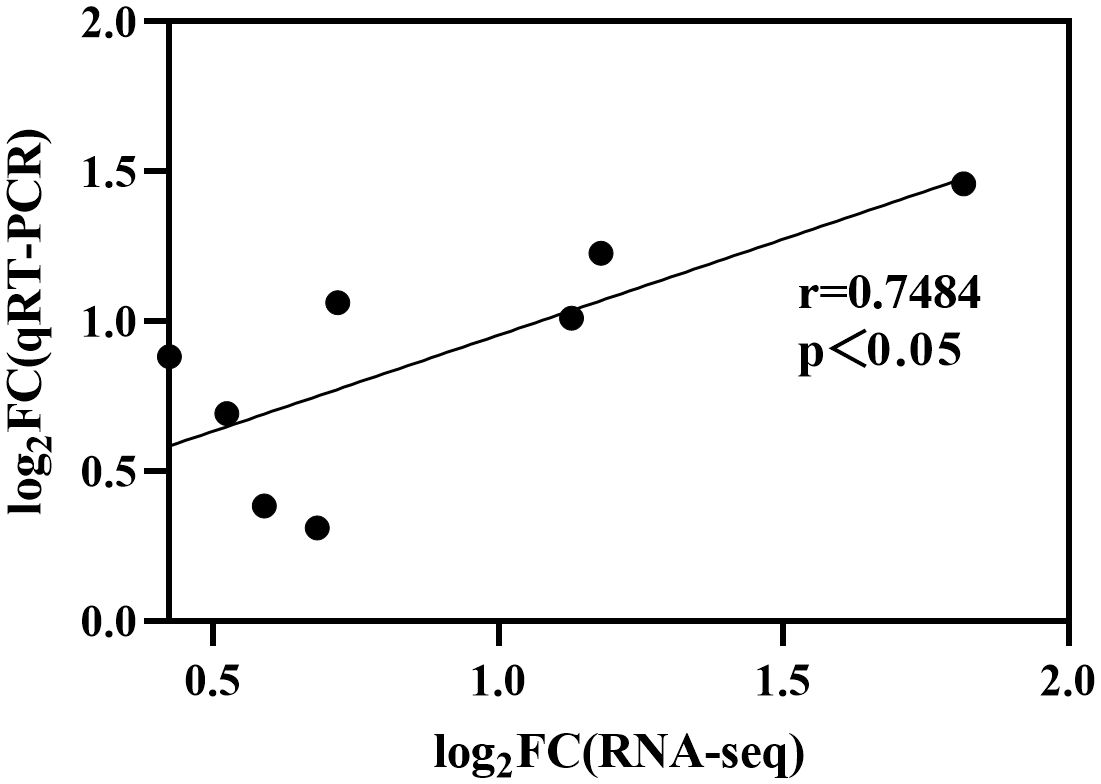

The expression of StCesAs was analyzed using RNA-seq data (Figure 8). Under normal conditions, some genes (StCesA1, 2, 3, 4, 5) were highly expressed in leaves, roots, flowers, petals, shoots, sepals, stolons, and petioles. StCesA7 and StCesA8 were highly expressed in shoots, roots, petioles, and stolons but low in flowers, sepals, leaves, and petals. The expression levels of StCesAs in different tissues indicate that they have distinct roles in potato growth and development. The differences in gene expression patterns between RNA-seq and qRT-PCR data may be due to various factors, such as different strains, growth conditions, and other external factors (Figure 11). The results of qRT-PCR (Figure 9) showed that the expressions of StCesA1, StCesA4, and StCesA8 were down-regulated with time, and the expressions of StCesA2 and StCesA3 reached a high level at 24h, and the expression of StCesA7 reached a high level at 48h. The expression of StCesA5 and StCesA6 reached a high level at 72h. These temporal patterns suggest that the StCesA genes play dynamic roles during different phases of potato growth and development.

Figure 11. Differences in gene expression between RNA-seq and qRT-PCR. Data was transformed to Log2 format and significantly correlated (r=0.7484, p<0.05).

Comparative studies have shown that the cellulose synthase gene family is highly conserved across different plant species and plays a crucial role in cell wall biosynthesis. For instance, research on barley identified seven CslF genes that are involved in the biosynthesis of β-d-glucans in cell walls (Burton et al., 2008). Similarly, a genome-wide bioinformatics analysis of the cellulose synthase gene family in common bean revealed distinct expression patterns during pod development (Liu et al., 2022). Moreover, comparative genomics and co-expression networks have been used to analyze the CesA gene family in eudicots, providing insights into their evolution and functional diversification. The results showed that duplications within the gene family have contributed to the expansion of CesA gene members in eudicots, suggesting an evolutionary mechanism for increasing the complexity and diversity of cellulose synthase functions. Co-expression networks have further demonstrated that primary and secondary cell wall modules are duplicated in eudicots, which may reflect the adaptation of these plants to various environmental conditions and developmental stages (Nawaz et al., 2019).

These results emphasize the complexity nature of cellulose biosynthesis regulation and its influence on plant growth and development. They also highlight the significance of CesA genes in diverse physiological functions and their potential as targets for genetic modification to enhance crop characteristics.

5 Conclusions

In this study, a total of 8 StCesA genes were identified in the whole potato genome using bioinformatics methods. StCesA gene family members are scattered on seven different chromosomes and divided into four clusters based on the phylogenetic tree. Intraspecies analysis showed a gene duplication event between StCesA1 and StCesA4. Synteny analysis showed that StCesAs and SlCesAs shared 10 pairs of homologous genes. We analyzed the expression pattern of StCesAs in different tissues in DM potato using RNA-seq data. The RNA-seq analysis showed that StCesA2 had the highest expression across all tissues, StCesA6 was weakly expressed in stolons and petals, and StCesA8 was not expressed in petals. Specifically, StCesA1 and StCesA2 had the highest expression in petioles, StCesA3, StCesA7, and StCesA8 in stolons, StCesA4 and StCesA6 in petals, and StCesA5 in flowers. Additionally, qRT-PCR analysis showed that the relative expression levels of StCesA1, StCesA4, and StCesA7 were down-regulated, and StCesA5 was up-regulated 72 hours after being infected by P. infestans. The results of this experiment are expected to promote the study of the CesA gene family and lay the foundation for further research on the role of CesA genes in biotic stress.

Data availability statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: PGSC repository: http://spuddb.uga.edu/.

Author contributions

HG: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision, Resources, Methodology. JM: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Formal analysis. LD: Writing – review & editing, Investigation. ZF: Writing – review & editing, Resources, Funding acquisition.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by The National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC)-Regional Science Fund (Grant Nos. 31860397), the Science and Technology Program of Gansu Province in China-Gansu Science and Technology Commissioner Special Project (23CXGA0061), and the Key Program of Natural Science Foundation of Gansu Province in China (22JR5RA228).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Appenzeller, L., Doblin, M., Barreiro, R., Wang, H., Niu, X., Kollipara, K., et al. (2004). Cellulose synthesis in maize: isolation and expression analysis of the cellulose synthase (CesA) gene family. Cellulose 11, 287–299. doi: 10.1023/B:CELL.0000046417.84715.27

Bailey, T. L., Johnson, J., Grant, C. E., Noble, W. S. (2015). The MEME suite. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, W39–W49. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv416

Baltz, R., Domon, C., Pillay, D. T., Steinmetz, A. (1992). Characterization of a pollen-specific cDNA from sunflower encoding a zinc finger protein. Plant J. 2, 713–721. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1992.t01-13-00999.x

Bano, N., Fakhrah, S., Mohanty, C. S., Bag, S. K. (2021a). Genome-wide identification and evolutionary analysis of gossypium tubby-like protein (TLP) gene family and expression analyses during salt and drought stress. Front. Plant Sci. 12. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.667929

Bano, N., Patel, P., Chakrabarty, D., Bag, S. K. (2021b). Genome-wide identification, phylogeny, and expression analysis of the bHLH gene family in tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum). Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 27, 1747–1764. doi: 10.1007/s12298-021-01042-x

Burton, R. A., Jobling, S. A., Harvey, A. J., Shirley, N. J., Mather, D. E., Bacic, A., et al. (2008). The genetics and transcriptional profiles of the cellulose synthase-like HvCslF gene family in barley. Plant Physiol. 146, 1821–1833. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.114694

Cardini, C. E., Leloir, L. F., Chiriboga, J. (1955). The biosynthesis of sucrose. J. Biol. Chem. 214, 149–155. doi: 10.1021/ja01119a546

Chao, J., Li, Z., Sun, Y., Aluko, O. O., Wu, X., Wang, Q., et al. (2021). MG2C: a user-friendly online tool for drawing genetic maps. Mol. Hortic. 1, 16. doi: 10.1186/s43897-021-00020-x

Chen, C., Wu, Y., Li, J., Wang, X., Zeng, Z., Xu, J., et al. (2023). TBtools-II: A “one for all, all for one” bioinformatics platform for biological big-data mining. Mol. Plant 16, 1733–1742. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2023.09.010

Cosgrove, D. J. (2005). Growth of the plant cell wall. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6, 850–861. doi: 10.1038/nrm1746

Devaux, A., Goffart, J. P., Kromann, P., Andrade-Piedra, J., Polar, V., Hareau, G. (2021). The potato of the future: opportunities and challenges in sustainable agri-food systems. Potato Res. 64, 681–720. doi: 10.1007/s11540-021-09501-4

Doblin, M. S., Kurek, I., Jacob-Wilk, D., Delmer, D. P. (2002). Cellulose biosynthesis in plants: from genes to rosettes. Plant Cell Physiol. 43, 1407–1420. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcf164

Dong, S.-m., Zhou, S.-q. (2022). Potato late blight caused by Phytophthora infestans: From molecular interactions to integrated management strategies. J. Integr. Agric. 21, 3456–3466. doi: 10.1016/j.jia.2022.08.060

Duan, Y., Duan, S., Xu, J., Zheng, J., Hu, J., Li, X., et al. (2021). Late blight resistance evaluation and genome-wide assessment of genetic diversity in wild and cultivated potato species. Front. Plant Sci. 12. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.710468

Ellis, C., Karafyllidis, I., Wasternack, C., Turner, J. G. (2002). The Arabidopsis mutant cev1 links cell wall signaling to jasmonate and ethylene responses. Plant Cell 14, 1557–1566. doi: 10.1105/tpc.002022

Gu, Y., Kaplinsky, N., Bringmann, M., Cobb, A., Carroll, A., Sampathkumar, A., et al. (2010). Identification of a cellulose synthase-associated protein required for cellulose biosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 12866–12871. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1007092107

Hardigan, M. A., Crisovan, E., Hamilton, J. P., Kim, J., Laimbeer, P., Leisner, C. P., et al. (2016). Genome reduction uncovers a large dispensable genome and adaptive role for copy number variation in asexually propagated solanum tuberosum. Plant Cell 28, 388–405. doi: 10.1105/tpc.15.00538

Hernandez-Blanco, C., Feng, D. X., Hu, J., Sanchez-Vallet, A., Deslandes, L., Llorente, F., et al. (2007). Impairment of cellulose synthases required for Arabidopsis secondary cell wall formation enhances disease resistance. Plant Cell 19, 890–903. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.048058

Holland, N., Holland, D., Helentjaris, T., Dhugga, K. S., Xoconostle-Cazares, B., Delmer, D. P. (2000). A comparative analysis of the plant cellulose synthase (CesA) gene family. Plant Physiol. 123, 1313–1324. doi: 10.1104/pp.123.4.1313

Horton, P., Park, K. J., Obayashi, T., Fujita, N., Harada, H., Adams-Collier, C. J., et al. (2007). WoLF PSORT: protein localization predictor. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, W585–W587. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm259

Hu, B., Jin, J., Guo, A. Y., Zhang, H., Luo, J., Gao, G. (2015). GSDS 2.0: an upgraded gene feature visualization server. Bioinformatics 31, 1296–1297. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu817

Kurek, I., Kawagoe, Y., Jacob-Wilk, D., Doblin, M., Delmer, D. (2002). Dimerization of cotton fiber cellulose synthase catalytic subunits occurs via oxidation of the zinc-binding domains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 11109–11114. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162077099

Lescot, M., Dehais, P., Thijs, G., Marchal, K., Moreau, Y., Van de Peer, Y., et al. (2002). PlantCARE, a database of plant cis-acting regulatory elements and a portal to tools for in silico analysis of promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 30, 325–327. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.325

Letunic, I., Bork, P. (2024). Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) v6: recent updates to the phylogenetic tree display and annotation tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 52, W78–W82. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkae268

Liu, J., Mushegian, A. (2003). Three monophyletic superfamilies account for the majority of the known glycosyltransferases. Protein Sci. 12, 1418–1431. doi: 10.1110/ps.0302103

Liu, X., Zhang, H., Zhang, W., Xu, W., Li, S., Chen, X., et al. (2022). Genome-wide bioinformatics analysis of Cellulose Synthase gene family in common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) and the expression in the pod development. BMC Genom Data 23, 9. doi: 10.1186/s12863-022-01026-0

Livak, K. J., Schmittgen, T. D. (2001). Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 25, 402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262

Mortazavi, A., Williams, B. A., McCue, K., Schaeffer, L., Wold, B. (2008). Mapping and quantifying mammalian transcriptomes by RNA-Seq. Nat. Methods 5, 621–628. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1226

Nawaz, M. A., Lin, X., Chan, T. F., Imtiaz, M., Rehman, H. M., Ali, M. A., et al. (2019). Characterization of cellulose synthase A (CESA) gene family in eudicots. Biochem. Genet. 57, 248–272. doi: 10.1007/s10528-018-9888-z

Nawaz, M. A., Rehman, H. M., Baloch, F. S., Ijaz, B., Ali, M. A., Khan, I. A., et al. (2017). Genome and transcriptome-wide analyses of cellulose synthase gene superfamily in soybean. J. Plant Physiol. 215, 163–175. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2017.04.009

Oomen, R. J., Tzitzikas, E. N., Bakx, E. J., Straatman-Engelen, I., Bush, M. S., McCann, M. C., et al. (2004). Modulation of the cellulose content of tuber cell walls by antisense expression of different potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) CesA clones. Phytochemistry 65, 535–546. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2003.12.019

Paluchowska, P., Sliwka, J., Yin, Z. (2022). Late blight resistance genes in potato breeding. Planta 255, 127. doi: 10.1007/s00425-022-03910-6

Pear, J. R., Kawagoe, Y., Schreckengost, W. E., Delmer, D. P., Stalker, D. M. (1996). Higher plants contain homologs of the bacterial celA genes encoding the catalytic subunit of cellulose synthase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 12637–12642. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.22.12637

Peng, L., Kawagoe, Y., Hogan, P. (2002). Sitosterol-β-glucoside as primer for cellulose synthesis in plants. Science 295, 147–150. doi: 10.1126/science.1064281

Perrin, R. M. (2001). Cellulose: how many cellulose synthases to make a plant? Curr. Biol. 11, R213–R216. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00108-7

Persson, S., Paredez, A., Carroll, A., Palsdottir, H., Doblin, M., Poindexter, P., et al. (2007). Genetic evidence for three unique components in primary cell-wall cellulose synthase complexes in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 15566–15571. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706592104

Potato Genome Sequencing, C., Xu, X., Pan, S., Cheng, S., Zhang, B., Mu, D., et al. (2011). Genome sequence and analysis of the tuber crop potato. Nature 475, 189–195. doi: 10.1038/nature10158

Richmond, T. A., Somerville, C. R. (2000). The cellulose synthase superfamily. Plant Physiol. 124, 495–498. doi: 10.1104/pp.124.2.495

Roy, S. W., Gilbert, W. (2005). Complex early genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 1986–1991. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408355101

Roy, S. W., Gilbert, W. (2006). The evolution of spliceosomal introns: patterns, puzzles and progress. Nat. Rev. Genet. 7, 211–221. doi: 10.1038/nrg1807

Saxena, I. M., Brown, R. M., Jr. (1995). Identification of a second cellulose synthase gene (acsAII) in Acetobacter xylinum. J. Bacteriol 177, 5276–5283. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.18.5276-5283.1995

Saxena, I. M., Lin, F. C., Brown, R. M., Jr. (1991). Identification of a new gene in an operon for cellulose biosynthesis in Acetobacter xylinum. Plant Mol. Biol. 16, 947–954. doi: 10.1007/BF00016067

Singh, V. K., Mangalam, A. K., Dwivedi, S., Naik, S. (1998). Primer premier: program for design of degenerate primers from a protein sequence. Biotechniques 24, 318–319. doi: 10.2144/98242pf02

Somerville, C. (2006). Cellulose synthesis in higher plants. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 22, 53–78. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.22.022206.160206

Song, X., Xu, L., Yu, J., Tian, P., Hu, X., Wang, Q., et al. (2019). Genome-wide characterization of the cellulose synthase gene superfamily in Solanum lycopersicum. Gene 688, 71–83. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2018.11.039

Sun, K., Wolters, A. M., Vossen, J. H., Rouwet, M. E., Loonen, A. E., Jacobsen, E., et al. (2016). Silencing of six susceptibility genes results in potato late blight resistance. Transgenic Res. 25, 731–742. doi: 10.1007/s11248-016-9964-2

Tamura, K., Stecher, G., Kumar, S. (2021). MEGA11: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 38, 3022–3027. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msab120

Tanaka, K., Murata, K., Yamazaki, M., Onosato, K., Miyao, A., Hirochika, H. (2003). Three distinct rice cellulose synthase catalytic subunit genes required for cellulose synthesis in the secondary wall. Plant Physiol. 133, 73–83. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.022442

Taylor, N. G., Howells, R. M., Huttly, A. K., Vickers, K., Turner, S. R. (2003). Interactions among three distinct CesA proteins essential for cellulose synthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 1450–1455. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0337628100

Yang, Q., Wan, X., Wang, J., Zhang, Y., Zhang, J., Wang, T., et al. (2020). The loss of function of HEL, which encodes a cellulose synthase interactive protein, causes helical and vine-like growth of tomato. Hortic. Res. 7, 180. doi: 10.1038/s41438-020-00402-0

Zhang, B., Zhou, Y. (2015). Plant cell wall formation and regulation. SCIENTIA Sin. Vitae 45, 544–556. doi: 10.1360/n052015-00076

Zhou, Z., Huang, J., Wang, Y., He, S., Yang, J., Wang, Y., et al. (2024). Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of the DA1 gene family in sweet potato and its two diploid relatives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25, 3000. doi: 10.3390/ijms25053000

Keywords: potato, CesA, biotic stress, expression analysis, qRT-PCR

Citation: Gong H, Ma J, Dusengemungu L and Feng Z (2024) Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of the cellulose synthase gene family in potato (Solanum tuberosum L.). Front. Plant Sci. 15:1457958. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2024.1457958

Received: 01 July 2024; Accepted: 18 November 2024;

Published: 11 December 2024.

Edited by:

Ertugrul Filiz, Duzce University, TürkiyeReviewed by:

Faisal Saeed, Niğde Ömer Halisdemir University, TürkiyeNasreen Bano, University of Pennsylvania, United States

Copyright © 2024 Gong, Ma, Dusengemungu and Feng. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Huiling Gong, Z29uZ2hsQGx1dC5lZHUuY24=

†These authors share first authorship

‡ORCID: Huiling Gong, orcid.org/0000-0002-7016-4153

Zaiping Feng, orcid.org/0000-0003-2657-4996

Huiling Gong

Huiling Gong Junxian Ma

Junxian Ma Leonce Dusengemungu

Leonce Dusengemungu Zaiping Feng

Zaiping Feng