- 1Institute of Botany, Jiangsu Province and Chinese Academy of Sciences, Nanjing, China

- 2College of Biology and the Environment, Nanjing Forestry University, Nanjing, China

- 3Institute of Botany, Jiangsu Province and Chinese Academy of Sciences, Jiangsu Key Laboratory for the Research and Utilization of Plant Resources, Nanjing, China

- 4Department of Biology, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark

- 5School of Biological Sciences, The University of Western Australia, Crawley, WA, Australia

Introduction: Partial or complete submergence of trees can occur in natural wetlands during times of high waters, but the submergence events have increased in severity and frequency over the past decades. Taxodium distichum is well-known for its waterlogging tolerance, but there are also numerous observations of this species becoming partially or complete submerged for longer periods of time. Consequently, the aims of the present study were to characterize underwater net photosynthesis (PN) and leaf anatomy of T. distichum with time of submergence.

Methods: We completely submerged 6 months old seedling of T. distichum and diagnosed underwater (PN), hydrophobicity, gas film thickness, Chlorophyll concentration and needles anatomy at discrete time points during a 30-day submergence event. We also constructed response curves of underwater PN to CO2, light and temperature.

Results: During the 30-day submergence period, no growth or formation new leaves were observed, and therefore T. distichum shows a quiescence response to submergence. The hydrophobicity of the needles declined during the submergence event resulting in complete loss of gas films. However, the Chlorophyll concentration of the needles also declined significantly, and it was there not possible to identify the main cause of the corresponding significant decline in underwater PN. Nevertheless, even after 30 days of complete submergence, the needles still retained some capacity for underwater photosynthesis under optimal light and CO2 conditions.

Discussion: However, to fully understand the stunning submergence tolerance of T. distichum, we propose that future research concentrate on unravelling the finer details in needle anatomy and biochemistry as these changes occur during submergence.

1 Introduction

Partial or complete submergence of trees can occur in natural wetlands during times of high waters. Accordingly, more than 1,000 species of trees and bushes in Pantanal (one of the world’s largest tropical wetlands) become submerged every year in the wet season when the River Negro rises up to 10 m above its water level in the dry season (Parolin, 2009). However, trees can also face complete submergence in man-made wetlands such as at the banks of the Three Gorges Reservoir, where Taxodium distichum has been introduced in an attempt to stabilize the steep banks (Wang et al., 2019; Ding et al., 2021; He et al., 2021). Since the Three Gorges dam has first stored water in June 2003, plants growing at lower elevations, including the cultivated T. distichum, have experienced periodic complete submergence every year. In this case, T. distichum not only survived but grew from seedling to tree (Li et al., 2006). We propose that the outstanding flood tolerance of T. distichum is partly a result of its remarkable ability to photosynthesize under water, which slows down carbohydrate depletion and protects the tissue from anoxia via O2 production during extended periods of submergence.

In air, gases diffuse 10,000-fold faster than in water, and therefore, CO2 and O2 generally restrict photosynthesis and respiration of submerged terrestrial plants. Consequently, submerged aquatic plants have evolved a number of key shoot and root traits involved in facilitating CO2 or O2 exchange with the floodwater including, but not limited to, thin leaf lamina composed of only two cell layers, thin or completely absent leaf cuticle, chloroplasts in the leaf epidermis, and aerenchyma to facilitate internal aeration (Sculthorpe, 1967). However, even in the presence of these extreme adaptations, CO2 availability can still limit underwater photosynthesis (Madsen and Sand-Jensen, 1991; Maberly and Madsen, 2002), and about half of the world’s aquatic plant species have thus evolved the ability to use bicarbonate (HCO3−) as an alternative inorganic carbon source in photosynthesis (Prins and Elzenga, 1989; Iversen et al., 2019). Lacking most of these key leaf traits, the photosynthetic rates of submerged terrestrial plants are significantly lower than those of aquatic plants regardless of whether underwater photosynthesis is measured at ambient or elevated CO2 levels (Colmer et al., 2011). Similarly, the availability of molecular O2 can restrict underwater respiration of submerged terrestrial plants, and an O2 pressure of almost twice that of atmospheric equilibrium is needed to saturate respiration (Colmer and Pedersen, 2008). A recent meta-analysis encompassing 112 species of both aquatic and terrestrial plants have clearly demonstrated that partial or complete submergence lead to significant declines in tissue O2 status particularly during darkness when the only source of O2 for underwater respiration is O2 dissolved in the floodwater (Herzog et al., 2023). However, some species of wetland plants form numerous adventitious roots emerging from the stem and hanging into the floodwater as response to partial or complete submergence (Rich et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2017; Lin et al., 2023). Such roots are referred to as aquatic adventitious roots and have been shown to act as “physical gills” by facilitating uptake of O2 from the floodwater (Ayi et al., 2016).

Some terrestrial plants, including the focal species of the present study, possess superhydrophobic leaves, and these have been shown to enhance gas exchange with the floodwater. Upon submergence, superhydrophobic leaves retain a thin gas film visible as a silvery sheen from the leaf surface (Pedersen and Colmer, 2012). Gas film formation on submerged leaves was first reported for deepwater rice, wheat, barley, and oats, where the beneficial effects on carbon fixation was also first reported (Raskin and Kende, 1983). Later, a series of studies reported leaf gas film formation during submergence in several species of wild wetland plants, where gas films were retained on partially or completely submerged leaves (Colmer and Pedersen, 2008; Pedersen et al., 2009; Winkel et al., 2016). The increased CO2 exchange caused by leaf gas films results in enhanced underwater net photosynthesis rate (PN), and generally underwater PN is 6- to 10-fold higher in the presence of leaf gas films compared with leaves without superhydrophobic leaves or with leaves where the gas films have been experimentally removed (Colmer and Pedersen, 2008; Pedersen et al., 2009; Winkel et al., 2011; Verboven et al., 2014; Konnerup et al., 2017; Winkel et al., 2017). Although the beneficial effects of leaf gas films have emphasized CO2 exchange for underwater photosynthesis, leaf gas films have also been shown to significantly enhance internal aeration. Accordingly, removal of hydrophobicity (and thereby also the leaf gas films) by brushing with a dilute detergent resulted in steep declines in O2 status of belowground tissues both in rice (Winkel et al., 2013) and in a wild wetland plant (Winkel et al., 2011), clearly demonstrating the crucial importance of leaf gas films for internal aeration of submerged terrestrial plants.

Low light availability under water may also restrict photosynthesis and submergence can invoke shade acclimation of submerged terrestrial leaves. In natural water bodies, the light intensity under water is lower than that in the air above not only because light is being reflected at the surface but also because light is being absorbed by water itself, by suspended particles such as algae, and by colored dissolved organic matter (Kirk, 1994). Murky floodwaters with algal blooms and/or high amounts of colored dissolved organic matter offer even less light for submerged plants with only 0.5% of the surface insolation left at deep floods (Vervuren et al., 2003). Consequently, many terrestrial plants respond to submergence by shade acclimations in their leaves, and these acclimations involve a reduction in leaf thickness, a thinner cuticle, thinner cell walls, and therefore a lower leaf mass area all resulting in better tissue O2 status (Mommer et al., 2007) and enhanced underwater PN due to better CO2 exchange (Mommer et al., 2004). Interestingly, the strong beneficial effect of leaf gas films on CO2 uptake is to a certain extent counteracted by the reflection of light at low light intensities; i.e., at low light, the silvery sheen of gas films reflects light and results in lower underwater PN (Winkel et al., 2017), showing that leaf gas films can also be disadvantageous during submergence in a low-light environment.

Trees and bushes forming the riparian vegetation often become partial or completely submerged when the river rises. However, poor flood tolerance of terrestrial plants leads to decreases in species richness as flooding intensity increases, leaving only the most flood-tolerant species to form the riparian vegetation (Garssen et al., 2017). Consequently, there are only two genera of Central European Trees showing very high flood tolerance (i.e., species of Alnus and Salix), and these are characterized with the formation of adventitious roots, lenticels, and aerenchyma in response to flooding (Glenz et al., 2006). However, the model species of the present study, T. distichum (L.) Rich, also shows extraordinary flood tolerance. It is a deciduous tree of the Taxodium genus, native to North America and Mexico where it forms large natural stands mostly in coastal plains affected by tide, in marshes with poor drainage, and in lowlands with periodic flooding (Wang et al., 2022; Guo et al., 2023). Owing to its outstanding flood tolerance, T. distichum has broad application prospects and is promoted for use in ecosystem restoration and construction of wetlands (Ding et al., 2021; He et al., 2021). More recently, it was found to have excellent tolerance to long-term periodic submergence in the water-level-fluctuating zone of the Three Gorges Reservoir (Wang et al., 2016, 2019). Interestingly, we found that T. distichum had a higher survival rate when submerged in winter than in summer, which may be because the activity of enzymes involved in underwater PN is affected by water temperature like other enzymes; thus, it is necessary to explore the response of underwater PN to temperature.

Consequently, the aims of the present study were to characterize underwater PN and leaf anatomy of T. distichum with time of submergence and to establish light, CO2, and temperature response curves of the underwater PN. Aerial photosynthesis of T. distichum has been thoroughly investigated (Wang et al., 2016; Taylor and Smith, 2017), but its capacity for underwater photosynthesis has not yet been evaluated. Interestingly, it was previously reported that T. distichum possesses a superhydrophobic leaf cuticle (Neinhuis and Barthlott, 1997), which should result in gas film formation during submergence. We therefore hypothesized that (i) some photosynthesis takes place when submerged, but the rate is strongly limited by light and CO2 showing a characteristic relationship with temperature; (ii) the underwater PN of T. distichum declines with time of submergence; (iii) and the decline in PN is linked to loss of leaf hydrophobicity and thereby the beneficial role of leaf gas films. Our study therefore fills an important gap related to the complete lack of knowledge related to the photosynthetic capacity of woody plants under water and the associated mechanistic understanding of flood tolerance of trees.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Plant materials and growth conditions

Leaf material for characterization of key photosynthetic parameters was sampled from a 4-year old T. distichum (L.) Rich at the Institute of Botany, Jiangsu Province and Chinese Academy of Sciences (32°05’ N, 118°83 ‘E) during midmorning from 9 to 10 a.m. The plant height was 2.6 m high and the diameter at breast height was 2.32 cm, which was in a rapid growth phase. Young but fully expanded and healthy branchlets with green needle-like leaves of the linear-lanceolate type were chosen for these experiments in June–July, whereas scale-like and appressed needles were disregarded.

For the long-term submergence experiment, seeds of T. distichum were sown in a seedling tray and after germination transferred to pots (23 cm upper diameter, 15 cm basal diameter, and 22 cm high) filled with a mixture of potting soil and sandy clay. The seedlings were grown in a greenhouse (temperature: 23 ± 2°C; humidity: 60%–70%) for 2 months and then moved outdoors for another 4 months, and the pots were watered daily with tap water. 30 healthy seedlings with an average height of 45 cm were selected for the experiment.

2.2 CO2 versus underwater PN

Underwater PN was measured following the approach of Pedersen et al. (2013). In brief, artificial floodwater was prepared according to Smart and Barko (1985) with a final alkalinity of 2.0 mol H+ equivalent m−3. Considering that the underwater photosynthetic CO2 saturation concentration of submerged leaves of terrestrial wetland plants is approximately 20–75 times or even higher than the atmospheric equilibrium concentration (~18 mmol m−3 free CO2) (Pedersen et al., 2009), a CO2 concentration range of 10–2,000 mmol m−3 was set. In addition, compared with high CO2 concentration, underwater PN changes more significantly under low CO2 concentration; thus, six concentration gradients (10, 25, 50, 100, 200, and 500 mmol m−3) were set for low concentration and three concentration gradients (1,000, 1,500, and 2,000 mmol m−3) were set for high concentration. Prior to the pH adjustment, the solution was purged with N2 to reduce the O2 concentration approximately 30%–50% of air equilibrium to prevent photorespiration during incubation (Setter et al., 1989). The artificial floodwater was then siphoned into 44-mL glass vials and two pieces of 3-mm glass beads were added to each vial to ensure the mixing during incubation. One branchlet with needles (approximately 1 cm2 or approximately 15.8 mg fresh mass) before the vial was sealed with a glass lid (no headspace or gas bubbles present). The vials were mounted on a vertically rotating disk (10 rpm) and inundated in a constant temperature bath at 25°C and illuminated with a photon flux of 1,000 µmol m−2 s−1 (see below). Vials without tissue served as blanks.

After 60 min, the vials were retrieved and the O2 concentration was measured using an O2 optode (OPTO-MR, Unisense, Denmark) inserted into the vial. The needles in the vial were then neatly placed on a clean white background board while a ruler is placed to take the photo. Make sure the leaves do not overlap each other when taking the photo; ImageJ software was used to measure the exact leaf area (Schneider et al., 2012). The photosynthetic rate was calculated using the following equation:

where ΔO2 is the difference in O2 concentration in vial with tissue and blanks, Vvial is the volume of the vials, i.e., 0.044 L, t is the incubation time, and A is the area of the needles.

2.3 Light versus underwater PN

Floodwater and tissue were prepared as above but with a fixed CO2 concentration of 500 mmol m−3. Compared with high light intensity, underwater PN changes more significantly under low light intensity; thus, six gradients (0, 50, 100, 200, 300, and 500 µmol photons m−2 s−1) were set for low light intensity and three gradients (1,000, 1,500, and 2,000 µmol photons m−2 s−1) were set for high light intensity. Different light intensities were established by using a high-pressure Na lamp at various distances and by regulating the voltage. For zero light, the vials were wrapped in aluminum foil. The light intensities were measured using a spherical PAR (photosynthetically active radiation) sensor (QSL2101, Biospherical Instruments Inc., USA). As for the CO2 response (see above), samples were incubated for 60 min.

2.4 Temperature versus underwater PN

Floodwater and tissue were prepared as above but with a fixed CO2 concentration of 500 mmol m−3 and PAR at 1,000 µmol photons m−2 s−1. The temperature was set to 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, or 35°C using a combination of an immersion heater (300W, SUNSUN, Zhejiang, China) and a water cooler (TECO, Taiwan, China) to achieve a stable temperature, which was monitored in real time by a temperature electrode (Temp-UniAmp thermosensor, Unisense, Denmark). As for the CO2 response (see above), samples were incubated for 60 min.

2.5 Long-term submergence

A 30-day submergence experiment with two treatments (drained controls or completely submerged) was conducted using 6-month-old T. distichum seedlings. Fifteen pots with one plant in each were transferred to three plastic tanks (depth, 69 cm; volume, 122 L) filled with tap water, with five seedlings (technical replicates) in each tank (true replicates). The water was changed every 2 days, and the hose was placed at the bottom of the bucket to ensure that the water was completely replaced. Another 15 plants served as controls, and these were unsubmerged and kept under conditions (photoperiod and temperature) similar to those for submerged plants and irrigated every 2 days. Underwater PN was measured on healthy needles on days 7, 14, 21, and 31 using a PAR of 1,000 µmol photons m−2 s−1 and a CO2 concentration of 500 mmol m−3 (see experimental procedure above) and leaves were transported in water back to the laboratory to minimize damage and exposure to air. It should be noted that the underwater PN of the submerged leaves of terrestrial wetland plants will be severely limited by the CO2 availability at atmospheric equilibrium CO2 concentrations. In order to more accurately evaluate the underwater photosynthetic capacity of submerged leaves, a CO2 concentration higher than atmospheric equilibrium was required, and 500 mmol m−3 is set for this experiment.

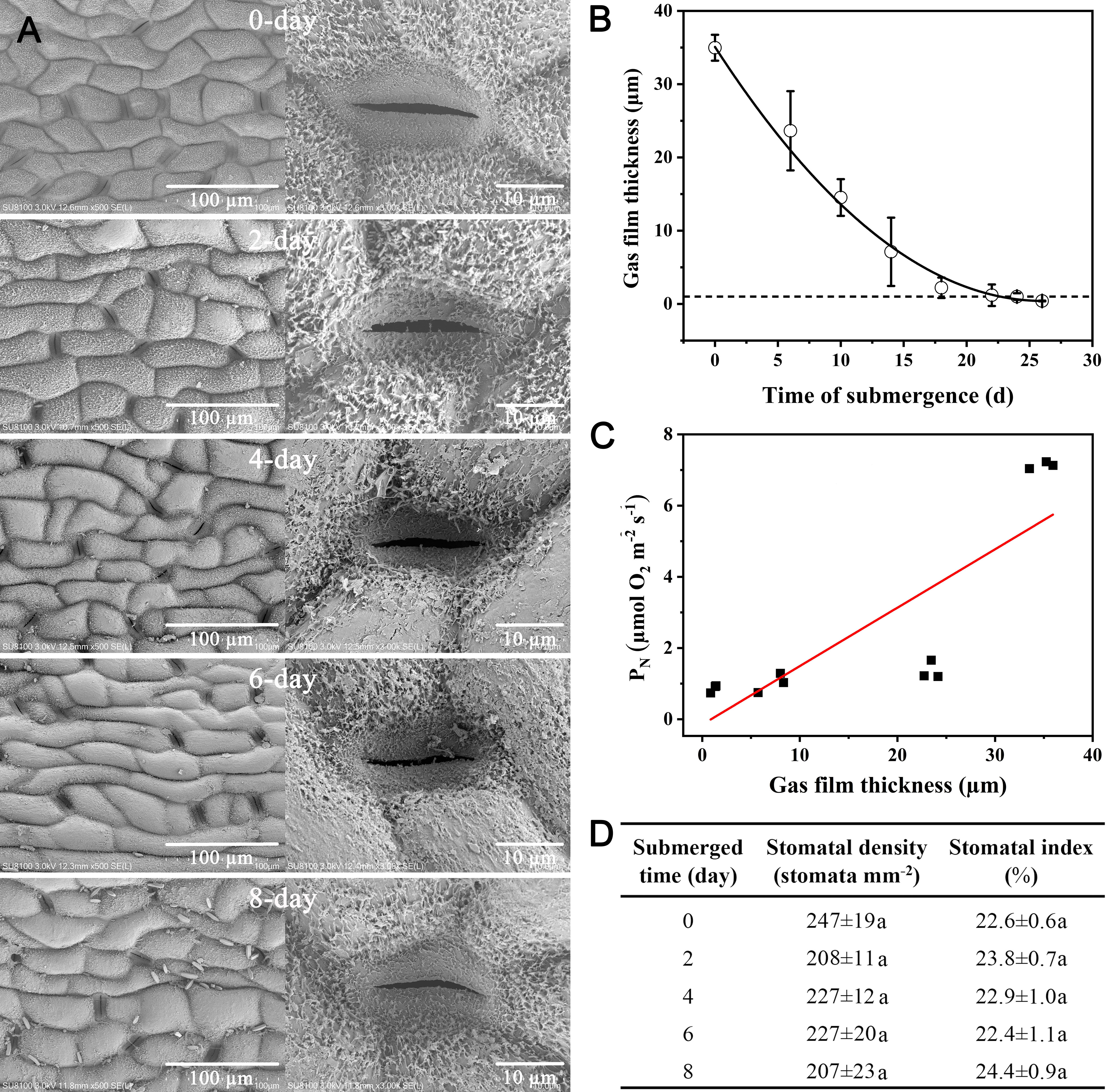

During the first 8 days of the submergence experiment, submerged leaves were harvested every other day. These were observed and photographed with scanning electron microscopy (SU8100, Hitachi Scientific Instruments, Japan). Subsequently, stomatal density (number of stomata per mm−2) and stomatal index (ratio of number of stomata to the total number of epidermal cells including stomata) were calculated from these images (Hegde and Krishnaswamy, 2021; Li et al., 2022).

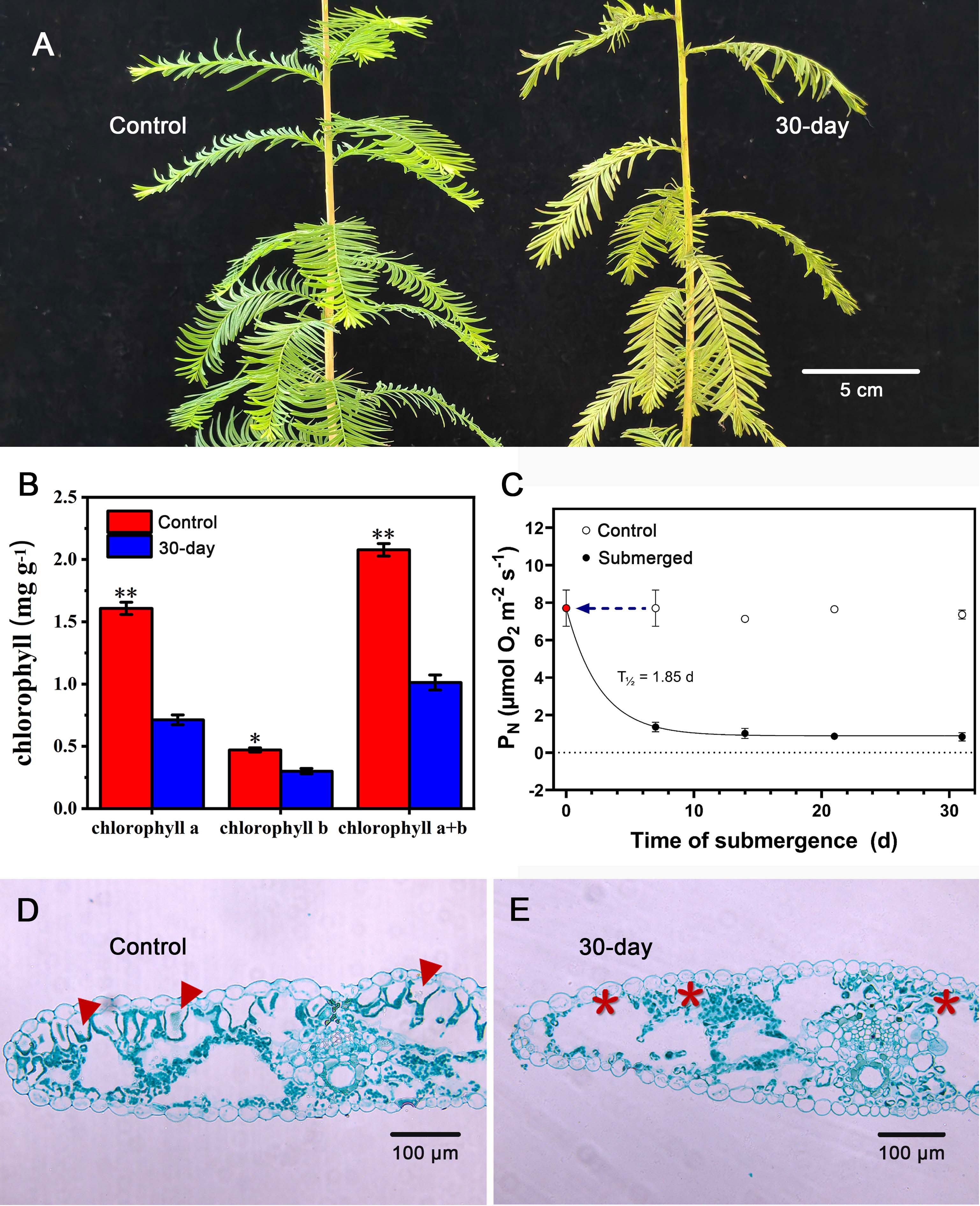

At the end, healthy leaves were sampled and then transported into water to minimize damage and re-exposure to air. Chlorophyll measurements were conducted on submerged leaves as well as controls using ethanol extractions and absorbance of the extract was measured on a spectrophotometer (UV-1800, Shanghai Mepuda Instrument Co., LTD, China). Chlorophyll was calculated using the equations in Zhang et al. (2020).

Finally, cross-sections for microscopy were prepared from paraffin-embedded needles and later studied using visible light microscopy (BX53F, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

2.6 Influence leaf gas films on underwater PN

To investigate the effects of leaf gas films on underwater PN, four healthy 6-month-old T. distichum seedlings were selected. Two fully unfolded branchlets were sampled from each plant and then they were divided into two groups. To remove hydrophobicity and thereby prevent formation of leaf gas films, one group was brushed five times, on both sides, with a fine paintbrush dipped into 0.01% (v/v) Triton X. After that, they were washed for 5 s, three times, in artificial floodwater without Triton X (Teakle et al., 2014; Winkel et al., 2014). The other group was untreated and served as control with each group having four replicates. Underwater PN was measured as described above with 500 mmol CO2 m−3 under a photon flux of 1,000 µmol photons m−2 s−1 at 25°C.

2.7 Assessment of gas film thickness and needle hydrophobicity

Leaf gas film thickness was measured following the approach of Raskin and Kende (1983). In brief, the buoyancy of a branchlet was measured on five replicates using a four-digit balance with a hook underneath before and after removal of hydrophobicity using 0.01% Triton X; see above. Next, the area of the needles was determined (see above), and the gas film thickness (m) was calculated as gas film volume (m3) divided by needle area (m2).

Surface hydrophobicity was assessed by measuring the contact angle of a 1-mm3 droplet of water on the needle surfaces following Sikorska et al. (2017). Branchlets with needles were held horizontal using a glue stick. Water droplets were applied to the lamina of 10 replicate needles (5 on the adaxial side and 5 on the abaxial side), and photographed at ×35 magnification using a horizontally positioned dissecting microscope (MZ62, Mshot, China) and a digital camera. The droplet contact angles were measured using ImageJ (ImageJ v.1.43U, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Finally, specific leaf area (SLA) was measured by determining the area (see above) and dry mass of needles, where the needles were dried for 48 h at 60°C. SLA was calculated as area (m2) divided by dry mass (kg).

2.8 Data analysis

We used non-linear regression to fit models derived from FvCB (CO2 response) (Liang and Liu, 2017) and light response was fitted according to the Ye model (Ye et al., 2013). The temperature optimum was modeled using a Gaussian function and a standard exponential function was used to predict temperature coefficient Q10 (Pedersen et al., 2016). The temperature coefficient Q10 represents the relative change of underwater PN with every 10°C change in temperature. The data were processed using Excel 2016 and graphed with Origin software (2021 64Bit, Electronic Arts Games, USA). Results were expressed as means ± standard deviation. All statistical tests were conducted using SPSS 16.0s (SPSS Inc., USA) including that of the Duncan’s multiple range test. Unless otherwise stated, a probability level of 0.05 was used.

3 Results

3.1 Submergence of Taxodium during times of high water level

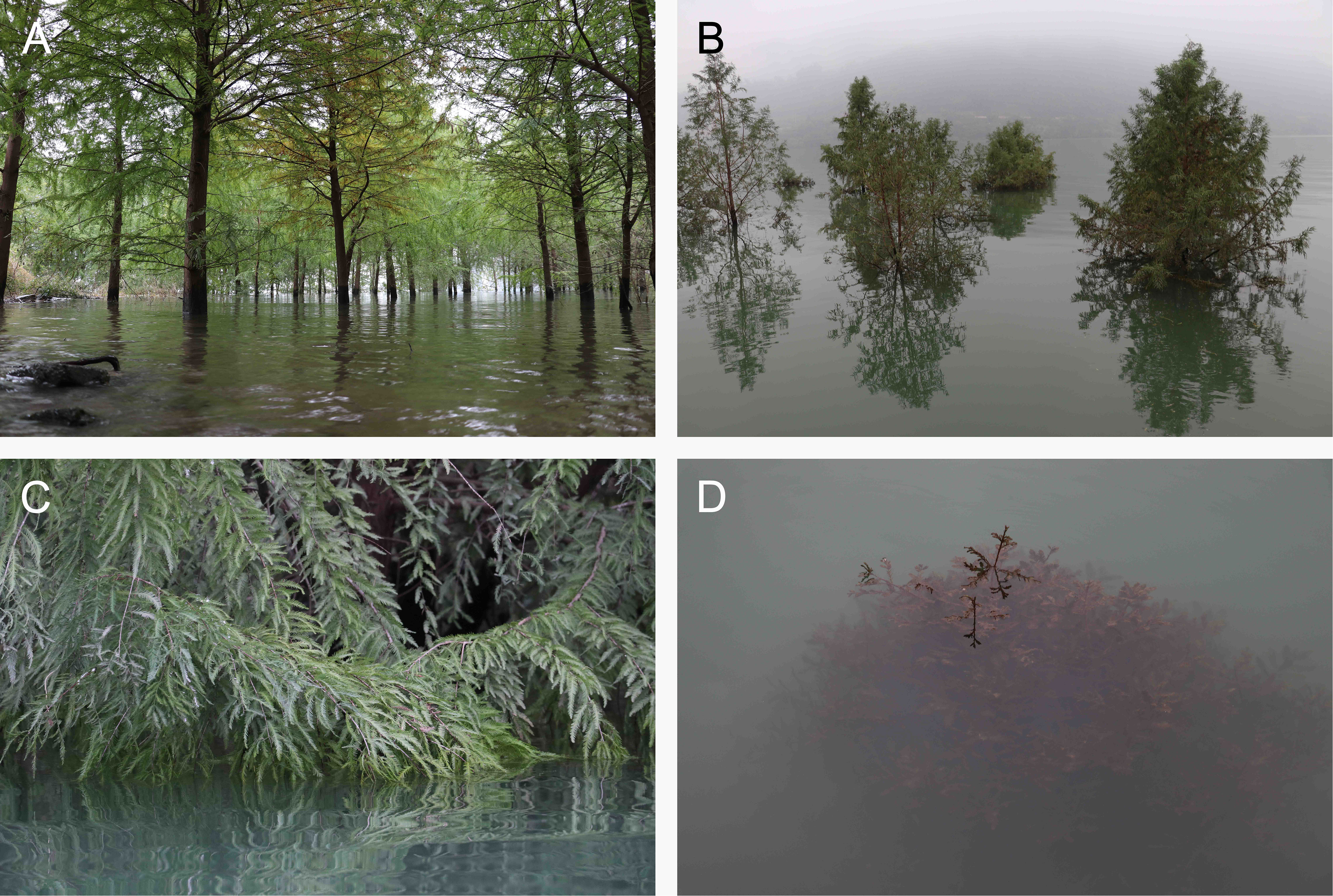

Waterlogging, partial submergence, and even complete submergence of Taxodium is a recurrent phenomenon during times of high water levels. When the water first starts rising, the soil becomes flooded, resulting in waterlogging of vast areas of trees (Figure 1A), and as the water continues to rise, the lower branches become submerged (Figures 1B, C). Ultimately, the entire canopy is under water (Figure 1D), and gas exchange with the atmosphere is no longer possible. The floodwater in the Yangtze River is murky as a result of suspended materials (Figure 1D), and therefore the light environment also changes upon submergence, resulting in reduced photosynthesis due to the combination of low light and restricted CO2 availability. The habitat photos in Figure 1 clearly demonstrate the relevance of our study, where we are aiming to characterize the ability of T. distichum to continue photosynthesizing under water with emphasis on response to CO2 and light availabilities, and temperature.

Figure 1 Habitat photos of Taxodium growing along the banks of the Three Gorges Reservoir, which is part of the Yangtze River. The species depicted is hybrid between Taxodium distichum and Taxodium mucronatum, which has been planted on the banks in an attempt to reduce erosion as the annual water level fluctuations are up to 175 m (Wang et al., 2019). (A) The initial phase of flooding resulting in waterlogging, but as the water continues to rise, the low branches become submerged (B, C). Finally, the entire canopy is under water (D) and may remain so for up to 120 days and still survive (Yang et al., 2023).

3.2 Response of underwater net photosynthesis to CO2, light, and temperature by Taxodium distichum

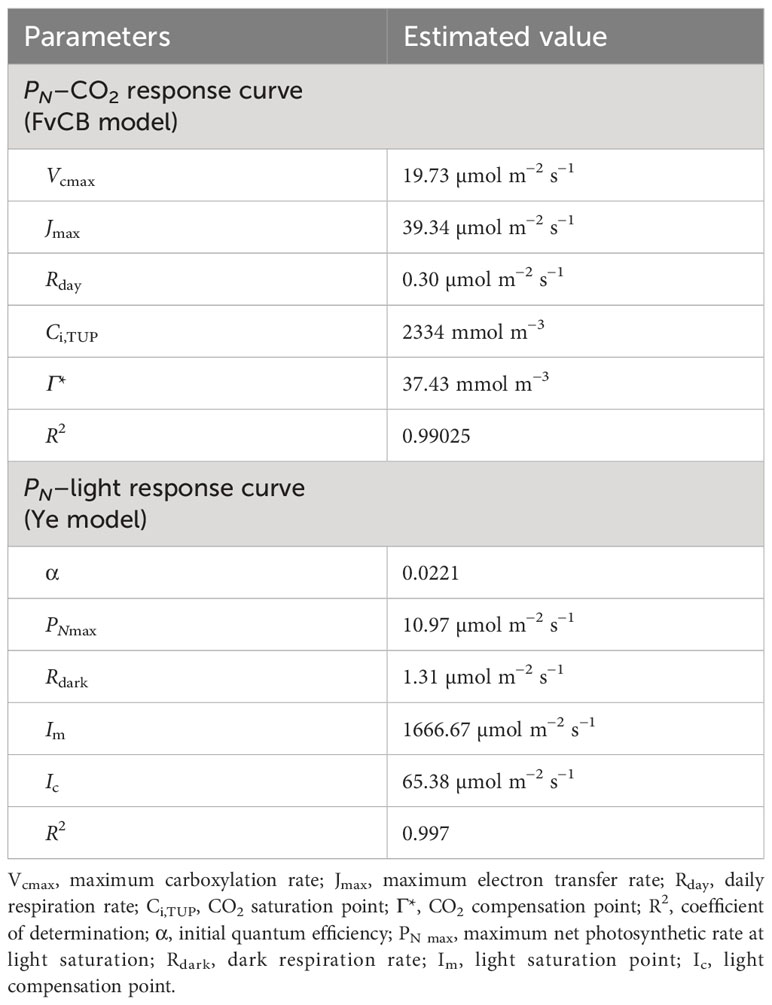

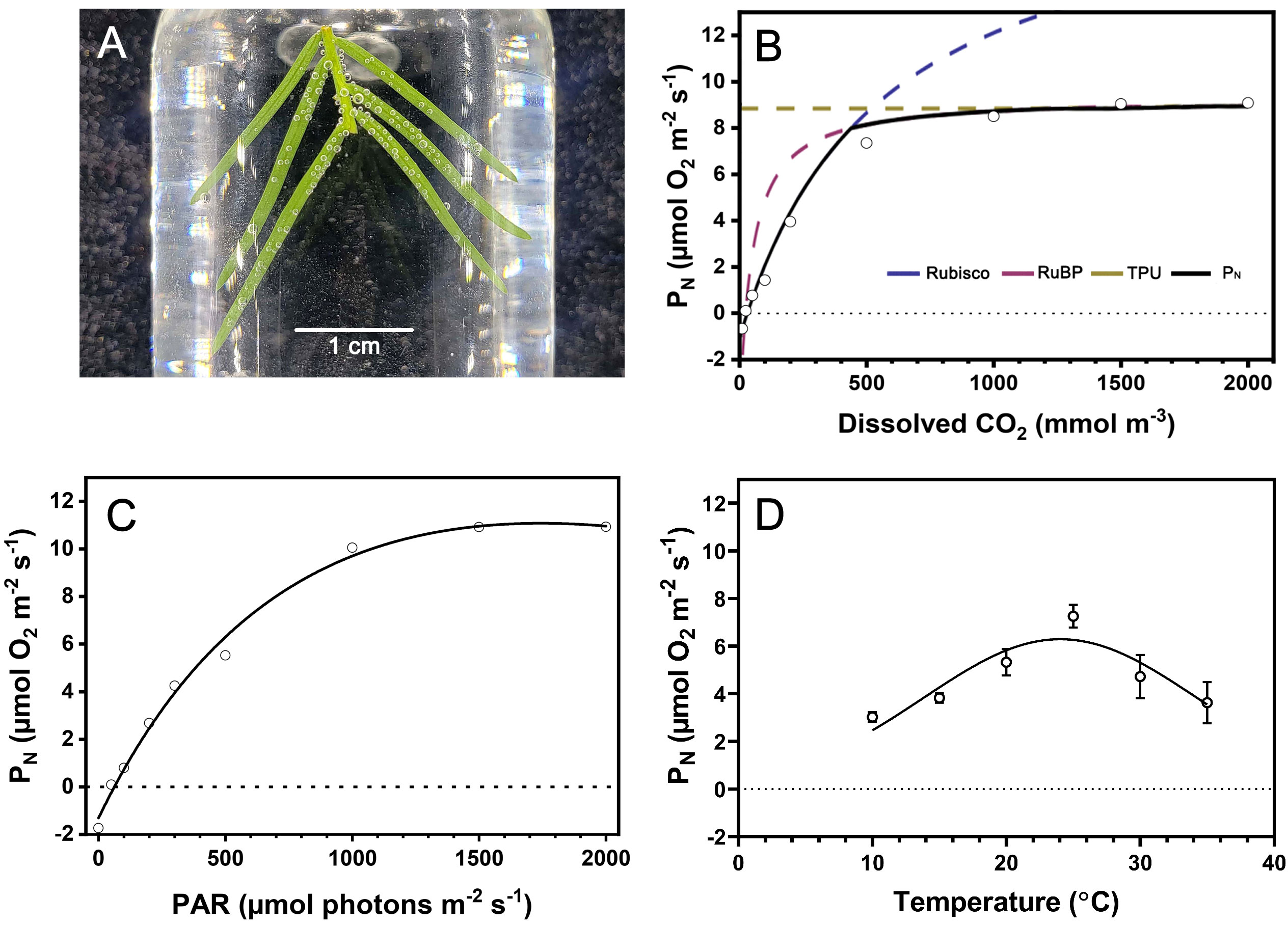

We characterized the response of underwater net photosynthesis (PN) to dissolved CO2, light availability, and temperature, which are relevant environmental parameters during submergence of T. distichum. Submerged branchlets with needles produced O2 when incubated in the artificial floodwater in the light visible as bubble formation on the needles (Figure 2A). The response of PN (i.e., net O2 consumption) to dissolved CO2 at 25°C and a photon flux of 1,000 µmol photons m−2 s−1 showed a typical saturation response, increasing as CO2 was raised to 2,000 mmol m−3 (Figure 2B). The FvCB model estimated the maximum carboxylation rate (Vcmax), maximum electron transfer rate (Jmax), and day respiratory rate (Rday) to be 19.73 µmol m−2 s−1, 39.34 µmol m−2 s−1, and 0.3 µmol m−2 s−1, respectively. However, the CO2 compensation point (Γ*) and CO2 saturation point (Ci,TUP) are 37.43 mmol m−3 and 2,334 mmol m−3, which are approximately 2-fold and 130-fold atmospheric equilibrium (~18 mmol m−3 free CO2), respectively (Table 1).

Figure 2 Response of underwater photosynthesis to CO2, light, and temperature of submerged Taxodium distichum branchlets. In (A), a section of a branchlet is incubated in artificial floodwater in a glass vial, and the gas bubbles forming on the leaves show that O2 is being produced in underwater photosynthesis. (B) Underwater net photosynthesis (PN) at PAR = 1,000 µmol photons m−2 s−1 as a response to CO2 dissolved in the floodwater followed a saturation curve and is fitted to the means using the FvCB model (R2 = 0.99). (C) Similarly, underwater PN was fitted to a general light response curve (Ye model, R2 = 0.997) measured with 500 µmol L−1 dissolved CO2 in the floodwater to enable estimation of PNmax (10.97 µmol O2 m−2 s−1). In (D), the response of PN to temperature is shown with 500 µmol L−1 dissolved CO2 in the floodwater and PAR = 1,000 µmol photons m−2 s−1, and using a Gaussian fit revealed an optimum for PN at 25°C. Data points in B–D show the mean ± SD (n = 4).

We diagnosed PN at contrasting light availabilities with 500 µmol CO2 L−1 in the floodwater. As expected, underwater PN also followed a saturation response with increasing light availability. In darkness, the dark respiration (Rdark) of branchlets with needles was 1.31 µmol O2 m−2 s−1 (Figure 2C). Using the equation from Ye et al. (2013), the light compensation point (Ic) and light saturation point (Im) were 65.38 µmol photons m−2 s−1 and 1,666.67 µmol photons m−2 s−1, respectively. PNmax was estimated to 10.97 µmol O2 m−2 s−1 at the given environmental conditions, i.e., dissolved CO2 at 500 µmol L−1 at 25°C (Table 1).

Underwater PN followed an exponential increase with increasing temperature in the tested interval from 10 to 25°C whereafter it steeply decreased with increasing temperature. Using a Gaussian model, we estimated the temperature optimum for underwater PN in T. distichum to 25°C with 500 µmol L−1 dissolved CO2 in the floodwater at a photon flux of 1,000 µmol photons m−2 s−1 (Figure 2D). Using the same dataset, but without considering temperatures exceeding the optimum for underwater PN, we estimated the Q10 of PN to 1.84 demonstrating the strong dependence of underwater PN on environmental temperature.

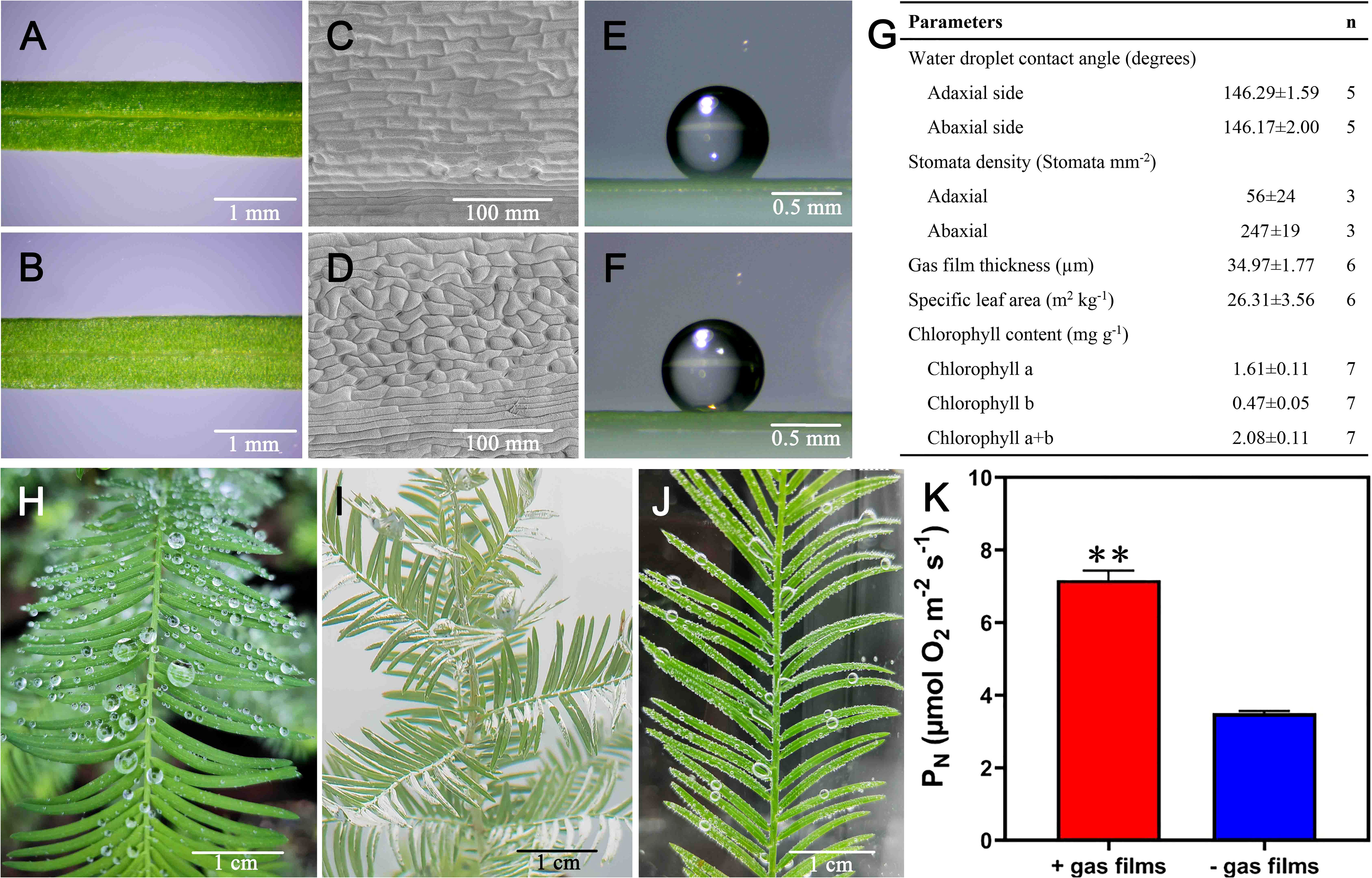

3.3 Hydrophobicity and gas film retention by needles of Taxodium distichum

At the onset of submergence, T. distichum forms a thin gas film on its needles and therefore we aimed at characterizing hydrophobicity, gas film thickness, and other key features known to influence underwater PN. Macroscopically, the needles are very similar on their adaxial and abaxial sides, but stomatal density differs with more than fourfold higher density of stomata on the abaxial side (Figures 3A–D, G). However, the water-repellent traits were similar, showing a contact angle of 146° on both sides, and although these angles only render the needles hydrophobic (and not superhydrophobic) (Koch and Barthlott, 2009), the hydrophobicity was nevertheless sufficient to initially retain a 35-µm-thick gas layer upon submergence (Figures 3E–G). The needles of T. distichum in air have been observed to repel water, and the gas film formed underwater is directly visible as a silvery sheen (Figures 3H, I), and its well-described facilitation of underwater photosynthesis is evident from the bubble formation when the branchlets are submerged in CO2-rich water in the light (Figure 3J). We also manipulated needle hydrophobicity to enable a direct comparison of underwater PN of needles with or without a gas film, and we found that the gas film increased underwater PN 2.1-fold as compared with needles where gas film formation was prevented (Figure 3K).

Figure 3 Adaxial (A, C, E) or abaxial (B, D, F) view of the needle surface close to the mid-vein, scanning electron micrograph of the cuticle and lateral view of a 1 mL water droplet. More details are shown in (G). The needles in the air repel water (H), and retain a thin gas film upon submergence visible as a silvery sheen (I). When submerged in light, underwater photosynthesis results in bubble formation on the needle surfaces (J, K) shows the effect of gas film on underwater net photosynthesis measured at PAR = 1,000 µmol photons m-2 s-1 and CO2 at 500 µmol L-1. In (K), ** indicates P < 0.01, one-tailed Student’s t-test.

3.4 Response of Taxodium distichum to long-term submergence

The fact that Taxodium can become completely submerged for several months prompted us to conduct a controlled laboratory experiment where we submerged 6-month-old plants for 30 days. During the first 24 days of submergence, the hydrophobicity was lost and the leaf cuticle gradually became colonized with bacteria with the first bacterial cells appearing already after 2 days of submergence (Figure 4A). The colonization of bacteria was accompanied by a decline in hydrophobicity, and leaf gas films dramatically decreased during the first few days of submergence (Figure 4B). This loss of gas films resulted in a significant decline in underwater PN as indicated by the significant positive correlation between gas film thickness and under PN (Figure 4C). Key stomatal features (stomatal density and stomatal index) did not change during the first 8 days of submergence (Figure 4D).

Figure 4 Changes in needle surface structure, gas film thickness, and underwater PN with time of submergence of Taxodium distichum. Scanning electron micrographs (A) show the changes in surface structure immediately before submergence (day 0, control) and days 2, 4, 6, and 8. Decline in gas film thickness (B) during the 30 days of submergence and the relationship between gas film thickness and underwater PN (C). A Pearson correlation analysis showed a correlation coefficient of 0.83 and p< 0.01. The table (D) shows stomatal aperture, density, opening rate and index, and the same time points. Data are means ± SD, n = 3–5. Different letters within the same column of data indicate p< 0.05 (Duncan’s multiple comparison).

However, over the entire submergence period of 30 days, significant changes took place at the needle level. The needles started yellowing (Figure 5A), and the yellow was also reflected in a significant decline in chlorophylls (Figure 5B). The combined effect of loss of hydrophobicity and the decline in chlorophylls resulted in a steep decline in underwater photosynthesis already within the first 8 days of submergence with a predicted T½ in PN of 1.85 days (Figure 5C). In addition to the biochemical changes in chlorophyll concentration, the needles also underwent anatomical changes during the 30 days of submergence as all of the palisade cells degraded (Figures 5D, E). Importantly, even with the loss of palisade tissues and the significant declines in chlorophylls, the needles maintained some capacity for underwater PN during the entire submergence period as underwater PN never declined below 1 µmol O2 m−2 s−1.

Figure 5 Response to long-term submergence by Taxodium distichum. (A) shows habitus photos of an unsubmerged control plant and a plant that has been completely submerged for 30 days. In (B), chlorophylls (Chla, Chlb, and Chla+b) are shown for unsubmerged control needles and needles that have been submerged for 30 days. (C) shows underwater net photosynthesis (PN) with time of submergence along with control measurements on unsubmerged branchlets at each sampling point. Data are means ± SD (n = 4), and * and ** indicate p< 0.05 and p< 0.01, respectively (one-tailed Student’s t-test), and the half-life of PN was calculated using an exponential decay function. Below, (D, E) show cross-sections of an unsubmerged needle and a needle that has been submerged for 30 days. To the left, arrowheads point at palisade tissues, and to the right, * indicates missing palisade tissues.

4 Discussion

Partial or complete submergence of trees is a common phenomenon in several natural or man-made wetlands (Parolin, 2009) and yet the ability of the leaves to photosynthesize under water had not yet previously been studied. In the present study, we found that the needles of T. distichum are hydrophobic and retain a thin gas film during submergence, and the gas films greatly enhanced underwater PN through their beneficial effect on gas exchange between needles and floodwater. We also found that the needle hydrophobicity was lost with time of submergence, but even after a month of complete submergence, the needles still maintained some capacity for underwater PN. Nevertheless, the needles had undergone structural and biochemical changes with loss of mesophyll cells and significant declines in chlorophyll concentrations. Below, we are discussing these findings in the context of existing knowledge on flood tolerance of terrestrial plants with emphasis on beneficial leaf traits such as leaf hydrophobicity, gas film formation, and SLA, and we also identify areas of exploration to fill in the many knowledge gaps that still remain.

4.1 Hydrophobicity of Taxodium distichum needles and gas film formation

Terrestrial leaves generally perform poorly under water due to the restricted gas exchange in water compared with air resulting in restricted O2 uptake for respiration or CO2 uptake for photosynthesis. The poor performance has been clearly demonstrated using the model plant, Rumex palustris, showing that underwater PN of aerial leaves was only 0.5% of the rate in air (Mommer et al., 2006). In stark contrast, leaves of R. palustris formed under water could attain rates of underwater PN at 35% of that in air showing the great benefit of leaf acclimation to underwater gas exchange. However, leaf acclimation is only a feasible strategy for long-term submergence, as production of new aquatic leaves requires reallocation of carbohydrates to fuel leaf. Instead, superhydrophobic leaves that retain a gas film under water have been shown to be a very competitive solution to enhance gas exchange without further investment in leaf acclimation (Colmer and Pedersen, 2008).

Hydrophobicity can be characterized using the contact angle of a microscopic water droplet. Accordingly, leaf cuticles with contact angles exceeding 150° are classified as superhydrophobic (with rice being a typical example) (Kwon et al., 2014), whereas those with contact angles less than 150°—but larger than 90° (Koch and Barthlott, 2009)—are hydrophobic. In the case of T. distichum, the contact angles were just below the 150° cut (146°, Figure 3G), but the needles nevertheless retained a gas film upon submergence (Figure 3I). The gas films forming on the needles of T. distichum were of similar thickness (35 µm, Figure 3G) to those formed by rice leaves (30–60 µm) (Winkel et al., 2014; Kurokawa et al., 2018; Mori et al., 2019) or by wheat leaves (20–40 µm) (Konnerup et al., 2017). Consequently, it is not surprising that the beneficial effects on gas exchange and underwater PN were significant.

In water, gas diffusion is slow and therefore physiological processes relaying on gas exchange can become restricted by slow substrate supply such as CO2 for photosynthesis. However, leaf gas films greatly enhance gas exchange (Verboven et al., 2014), and we found that needles with gas films achieved twofold higher photosynthetic rates compared with needles that had the hydrophobicity removed and where gas films therefore did not form (Figure 3K). It has previously been found that leaf gas films can increase underwater PN up to three- to sevenfold (Colmer and Pedersen, 2008), but the photosynthesis in these experiments was assessed at lower (200 µM) external CO2 concentrations, where the beneficial effect of gas films on gas exchange is more pronounced (Winkel et al., 2017). Interestingly, the underwater PN obtained at saturating light and CO2 levels in the present study matched those of PN in air; i.e., in both environments, the rates were approximately 10–12 µmol O2 m−2 s−1 (Figures 2B, C) (Neufeld, 1983; Mommer et al., 2006), underlining the significant effect of gas films on the needles of T. distichum. Consequently, we propose that a key reason for the stunning flood tolerance of T. distichum is its ability to maintain a substantial photosynthetic activity during submergence resulting in both carbohydrate and O2 production. However, the realized photosynthetic rates greatly depend on both light and CO2 availability under water and, to a large extent, temperature as well.

4.2 Influence of CO2, light, and temperature on underwater PN of Taxodium distichum

CO2 uptake by T. distichum followed a classical FvCB response curve. However, underwater PN remained negative until the CO2 compensation point at 37.43 mmol m−3 was reached; below, the needles of T. distichum consumed more O2 than they produced. The CO2 compensation point is equivalent to approximately twofold that of atmospheric equilibrium (~18 mmol m−3 free CO2), demonstrating the importance of net CO2 production in the floodwater in order for the underwater PN to become positive and therefore result in significant carbohydrate production. The Ci,TUP (CO2 saturation point) was estimated to 2,334 mmol m−3, or 130-fold atmospheric equilibrium, which is higher than that of submerged rice (Winkel et al., 2013) and submerged wheat (Winkel et al., 2017), and even higher than that of submerged Hordeum marinum (Pedersen et al., 2010). It has been demonstrated that the underwater PN capacity of submerged plants was severely limited at atmospheric equilibrium CO2 concentrations (Pedersen et al., 2009). Although some studies found that the CO2 concentration recorded in flooded rice fields was 20–180 times the atmospheric equilibrium concentration (360–3,240 mmol m−3) (Setter et al., 1987), the diffusion rate of the gas in water is 10,000 times lower than in air, resulting in underwater PN being still limited (Pedersen et al., 2013). CO2 availability limitations are a long-standing challenge for submerged plants, but interestingly, rice, wheat, and H. marinum retain leaf gas films when submerged, which has been shown to significantly enhance gas exchange. The overall similarity of the CO2 response in T. distichum to the other three terrestrial species with leaf gas films is likely due to the physical effect of the gas films facilitating the exchange between needles and floodwater rather than physiological similarities among these distantly related species.

Light utilization by T. distichum under water also showed a saturating response to light when assessed with 500 µmol CO2 L−1 in the floodwater. As for CO2, underwater PN was initially negative at low light levels and only reached positive values (Ic) at PAR > 65.38 µmol photons m−2 s−1 (Figure 2C). When PAR is higher than the saturation point (Im) of 1,666.67 µmol photons m−2 s−1, underwater PN reaches a maximum value (PNmax) of 10.97 µmol m−2 s−1, which is very difficult to achieve due to light loss; thus, underwater PN is generally limited by PAR. The initial quantum efficiency (α) of 0.0221 absorbed was in the same order of magnitude as that of submerged wheat (Winkel et al., 2017) and Phalaris arundinacea (a terrestrial wetland species also forming leaf gas films upon submergence) (Vervuren et al., 1999; Winkel et al., 2017), whereas two other species without gas films utilized light much less efficiently (Rumex crispus and Arrhenatherum elatius) (Vervuren et al., 1999). These findings emphasize the importance of gas films also for light use efficiency as the light use relies not only on incident light reaching the leaf surfaces but also on entry of CO2.

In addition to CO2 and light, underwater PN of T. distichum was also strongly affected by the environmental temperature. In the temperature range tested, i.e., 10 to 35°C, there was a strong positive relationship between temperature and underwater PN until the temperature optimum was reached at 25°C after which PN declined with increasing temperature (Figure 2D). This is a common response of underwater PN to rising temperature as also demonstrated for two tidal seagrass species, Thalassia hemprichii and Enhalus acoroides (Pedersen et al., 2016). Being tropical species, these seagrasses showed a temperature optimum for underwater PN at 33°C, i.e., 8°C above that of T. distichum. The Q10 of underwater PN in T. distichum was somewhat lower (1.8) than that of T. hemprichii (2.0) and E. acoroides (2.8) (Pedersen et al., 2016), but it nevertheless show the strong dependency of temperature for underwater PN also in T. distichum. This is an important point to consider when extrapolating the current laboratory findings to the field situation since the water temperature in the Yangtze River can fluctuate from 11 to 22°C during the time of the year when the trees on the banks become submerged (Yu et al., 2021).

4.3 Responses of Taxodium distichum to long-term submergence

The trees growing on the banks of the Yangtze River can become partially or completely submerged for up to 120 days and still survive (Yang et al., 2023), and we therefore tested the response of T. distichum to long-term submergence. Six-month old seedlings were completely submerged for a period of 30 days with sampling of leaf tissue during the period at discrete time points. Leaf gas films quickly diminished, and the decline in gas film thickness was accompanied by a decline in underwater PN (Figure 4C). The strong relationship between gas film thickness and underwater PN during long-term submergence has previously been observed in rice (Winkel et al., 2014), but our study represents the first to demonstrate this relationship for a tree species.

The gas films forming on the surfaces of the submerged needles of T. distichum persist longer than in other species tested with hydrophobic cuticles. In the present study, the gas films were detectable up to 24 days of submerged after which they had totally vanished (Figure 4B). This is longer than observed for rice, which represents the only other species with superhydrophobic leaves, where gas film thickness have been followed during a submergence event. Here, it was found that gas film thickness was below the detection limit already after 7 days of submergence (Winkel et al., 2014). In T. distichum, the needles maintained their ability to photosynthesize also after the gas films were lost at a rate of approximately 1 µmol O2 m−2 s−1, which is similar to the photosynthetic rate of rice and wheat once the leaf gas films of these species have also disappeared due to long-term submergence (Winkel et al., 2014; Konnerup et al., 2017). It is still not fully understood why the loss in hydrophobicity occurs during submergence. However, the present study as well as one on wheat (Konnerup et al., 2017) clearly demonstrated that a biofilm was established during submergence (Figure 3I), but if this biofilm is the result or the cause of loss of hydrophobicity remains unknown.

Distinct anatomical and biochemical changes occurred during the long-term submergence event. The decline in total chlorophylls was significant with initial values at 2.1 mg g−1 DM and only 1.0 mg g−1 DM after 30 days of submergence (Figure 5B). While this decline will have significant consequences for the light capturing capabilities, the decline in submerged rice was even more pronounced where the initial levels are at approximately 18 mg g−1 DM to less than 5 mg g−1 DM in only 2 weeks. The decrease in chlorophyll concentration observed in the present study may be one of the important reasons for the decrease in underwater PN, as it has been shown that underwater PN of rice is positively correlated with leaf chlorophyll concentration (Winkel et al., 2014). The significant decrease in chlorophyll concentration is likely a result of palisade tissue loss in needles (Figures 5D, E). To our knowledge, similar observations are missing in the literature as previous studies have focused on anatomy of leaves formed during the submergence event (Mommer et al., 2007) and not on acclimation of already existing leaves. The lysis of palisade tissues observed towards the end of the 30-day submergence event might be accompanied by water infiltration in the newly formed cavities, and such water-filled cavities would slow down intra-tissue diffusion of O2 and CO2 (Armstrong, 1980). Interestingly, the parallel decline in chlorophyll concentration and leaf gas film thickness makes it difficult to identify the primary causal effect of the observed decline in underwater PN.

5 Conclusions and perspectives

During the 30-day submergence period, no growth or formation new leaves were observed, and therefore, T. distichum shows a quiescence response to submergence (cf. Bailey-Serres and Voesenek, 2008). The hydrophobicity of the needles declined during the submergence event, resulting in loss of gas films. However, the chlorophyll concentration of the needles also declined significantly, and it was therefore not possible to identify the main cause of the corresponding significant decline in underwater PN.

Several questions still remain unresolved in order to fully understand the striking ability of T. distichum to withstand partial or complete submergence for months. We propose that future research concentrate on unraveling the finer details in needle anatomy and biochemistry as these changes occur during submergence. For example, the lysis of palisade tissues should be further studied in order to understand if the lysis is merely a consequence of senescence processes or if the lysis is actively controlled via programmed cell death with the aim of acclimating the leaves to a low-light environment and the slow diffusion of gases in water. We also suggest to investigate if changes in cuticle structure take place beyond those involved in surface hydrophobicity. A thinning of the cuticle would greatly enhance diffusion of O2 and CO2 from the floodwater to the needles’ tissues and thereby enhance the supply of O2 for dark respiration or CO2 for underwater photosynthesis. In addition, whether the bacteria colonized on leaf surface will cause negative impacts on the leaf cells and hence affect hydrophobicity and photosynthesis, and the difference in underwater PN capacity and detailed submergence tolerance mechanisms of T. distichum seedlings and big trees are also interesting questions that are worthy of further investigation.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Author contributions

JG: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Software, Data curation. JX: Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision. YY: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Resources. OP: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Data curation. JH: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by grants from the Jiangsu Special Fund on Technology Innovation of Carbon Dioxide Peaking and Carbon Neutrality, grant no. BE2022420, and the Jiangsu Long-term Scientific Research Base for Taxodium Rich Breeding and Cultivation, grant no. LYKJ(2021)05. OP was supported by the Carlsberg Foundation, grant no. CF23-0039.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2024.1355729/full#supplementary-material

References

Armstrong, W. (1980). “Aeration in higher plants,” in Advances in botanical research (Elsevier) 7, 225–332. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2296(08)60089-0

Ayi, Q., Zeng, B., Liu, J., Li, S., Van Bodegom, P. M., Cornelissen, J. H. C. (2016). Oxygen absorption by adventitious roots promotes the survival of completely submerged terrestrial plants. Ann. Bot. 118, 675–683. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcw051

Bailey-Serres, J., Voesenek, L. (2008). Flooding stress: acclimations and genetic diversity. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 59, 313–339. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.59.032607.092752

Colmer, T., Pedersen, O. (2008). Oxygen dynamics in submerged rice (Oryza sativa). New Phytol. 178, 326–334. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.02364.x

Colmer, T. D., Winkel, A., Pedersen, O. (2011). A perspective on underwater photosynthesis in submerged terrestrial wetland plants. AoB Plants 2011, plr030. doi: 10.1093/aobpla/plr030

Ding, D., Liu, M., Arif, M., Yuan, Z., Li, J., Hu, X., et al. (2021). Responses of ecological stoichiometric characteristics of carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus to periodic submergence in mega-reservoir: growth of Taxodium distichum and Taxodium ascendens. Plants 10, 2040. doi: 10.3390/plants10102040

Garssen, A. G., Baattrup-Pedersen, A., Riis, T., Raven, B. M., Hoffman, C. C., Verhoeven, J. T., et al. (2017). Effects of increased flooding on riparian vegetation: Field experiments simulating climate change along five European lowland streams. Global Change Biol. 23, 3052–3063. doi: 10.1111/gcb.13687

Glenz, C., Schlaepfer, R., Iorgulescu, I., Kienast, F. (2006). Flooding tolerance of Central European tree and shrub species. For. Ecol. Manage. 235, 1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2006.05.065

Guo, J., Xue, J., Hua, J., Yin, Y., Creech, D. L., Han, J. (2023). Research status and trends of taxodium distichum. HortScience 58, 317–326. doi: 10.21273/HORTSCI17045-22

He, X., Wang, T., Wu, K., Wang, P., Qi, Y., Arif, M., et al. (2021). Responses of swamp cypress (Taxodium distichum) and Chinese willow (Salix matSudana) roots to periodic submergence in mega-reservoir: Changes in organic acid concentration. Forests 12, 203. doi: 10.3390/f12020203

Hegde, S. M., Krishnaswamy, K. (2021). Measurement of stomatal density stomatal index in some species of terrestrial orchids. Ann. Agri Bio Res. 26, 173–177.

Herzog, M., Pellegrini, E., Pedersen, O. (2023). A meta-analysis of plant tissue O2 dynamics. Funct. Plant Biol. 10, 1071/FP22294. doi: 10.1071/FP22294

Iversen, L. L., Winkel, A., Båstrup-Spohr, L., Hinke, A. B., Alahuhta, J., Baattrup-Pedersen, A., et al. (2019). Catchment properties and the photosynthetic trait composition of freshwater plant communities. Science 366, 878–881. doi: 10.1126/science.aay5945

Kirk, J. T. O. (1994). Light and photosynthesis in aquatic ecosystems (New York: Cambridge Univ Press). doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511623370

Koch, K., Barthlott, W. (2009). Superhydrophobic and superhydrophilic plant surfaces: an inspiration for biomimetic materials. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A: Mathematical Phys. Eng. Sci. 367, 1487–1509. doi: 10.1098/rsta.2009.0022

Konnerup, D., Winkel, A., Herzog, M., Pedersen, O. (2017). Leaf gas film retention during submergence of 14 cultivars of wheat (Triticum aestivum). Funct. Plant Biol. 44, 877–887. doi: 10.1071/FP16401

Kurokawa, Y., Nagai, K., Huan, P. D., Shimazaki, K., Qu, H., Mori, Y., et al. (2018). Rice leaf hydrophobicity and gas films are conferred by a wax synthesis gene (LGF 1) and contribute to flood tolerance. New Phytol. 218, 1558–1569. doi: 10.1111/nph.15070

Kwon, D. H., Huh, H. K., Lee, S. J. (2014). Wettability and impact dynamics of water droplets on rice (Oryza sativa L.) leaves. Experiments fluids 55, 1–9. doi: 10.1007/s00348-014-1691-y

Li, C., Zhong, Z., Liu, Y. (2006). Effect of soil water changes on photosynthetic characteristics of Taxodium distichum seedlings in the hydro-fluctuation belt of the Three Gorges Reservoir area. Front. Forestry China 1, 163–169. doi: 10.1007/s11461-006-0013-9

Li, Q., Zhou, L., Chen, Y., Xiao, N., Zhang, D., Zhang, M., et al. (2022). Phytochrome interacting factor regulates stomatal aperture by coordinating red light and abscisic acid. Plant Cell 34, 4293–4312. doi: 10.1093/plcell/koac244

Liang, X.-Y., Liu, S.-R. (2017). A review on the FvCB biochemical model of photosynthesis and the measurement of A-Ci curves. Chin. J. Plant Ecol. 41, 693–706. doi: 10.17521/cjpe.2016.0283

Lin, C., Peralta Ogorek, L. L., Liu, D., Pedersen, O., Sauter, M. (2023). A quantitative trait locus conferring flood tolerance to deepwater rice regulates the formation of two distinct types of aquatic adventitious roots. New Phytol. 238, 1403–1419. doi: 10.1111/nph.18678

Maberly, S. C., Madsen, T. V. (2002). Freshwater angiosperm carbon concentrating mechanisms: processes and patterns. Funct. Plant Biol. 29, 393–405. doi: 10.1071/PP01187

Madsen, T. V., Sand-Jensen, K. (1991). Photosynthetic carbon assimilation in aquatic macrophytes. Aquat. Bot. 41, 5–40. doi: 10.1016/0304-3770(91)90037-6

Mommer, L., Pedersen, O., Visser, E. J. W. (2004). Acclimation of a terrestrial plant to submergence facilitates gas exchange under water. Plant Cell Environ. 27, 1281–1287. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2004.01235.x

Mommer, L., Pons, T. L., Visser, E. J. (2006). Photosynthetic consequences of phenotypic plasticity in response to submergence: Rumex palustris as a case study. J. Exp. Bot. 57, 283–290. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erj015

Mommer, L., Wolters-Arts, M., Andersen, C., Visser, E. J., Pedersen, O. (2007). Submergence-induced leaf acclimation in terrestrial species varying in flooding tolerance. New Phytol. 176, 337–345. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.02166.x

Mori, Y., Kurokawa, Y., Koike, M., Malik, A. I., Colmer, T. D., Ashikari, M., et al. (2019). Diel O2 dynamics in partially and completely submerged deepwater rice: leaf gas films enhance internodal O2 status, influence gene expression and accelerate stem elongation for ‘snorkelling’during submergence. Plant Cell Physiol. 60, 973–985. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcz009

Neinhuis, C., Barthlott, W. (1997). Characterization and distribution of water-repelent, self-cleaning plant surfaces. Ann. Bot. 79, 667–677. doi: 10.1006/anbo.1997.0400

Neufeld, H. S. (1983). Effects of light on growth, morphology, and photosynthesis in baldcypress (Taxodium distichum (L.) Rich.) and pondcypress (T. ascendens Brongn.) seedlings. Bull. Torrey Botanical Club 110, 43–54. doi: 10.2307/2996516

Parolin, P. (2009). Submerged in darkness: adaptations to prolonged submergence by woody species of the Amazonian floodplains. Ann. Bot. 103, 359–376. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcn216

Pedersen, O., Colmer, T. D. (2012). Physical gills prevent drowning of many wetland insects, spiders and plants. J. Exp. Biol. 215, 705–709. doi: 10.1242/jeb.065128

Pedersen, O., Colmer, T. D., Borum, J., Zavala-Perez, A., Kendrick, G. A. (2016). Heat stress of two tropical seagrass species during low tides–impact on underwater net photosynthesis, dark respiration and diel in situ internal aeration. New Phytol. 210, 1207–1218. doi: 10.1111/nph.13900

Pedersen, O., Colmer, T. D., Sand-Jensen, K. (2013). Underwater photosynthesis of submerged plants – recent advances and methods. Front. Plant Sci. 4. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2013.00140

Pedersen, O., Malik, A. I., Colmer, T. D. (2010). Submergence tolerance in Hordeum marinum: dissolved CO2 determines underwater photosynthesis and growth. Funct. Plant Biol. 37, 524–531. doi: 10.1071/FP09298

Pedersen, O., Rich, S. M., Colmer, T. D. (2009). Surviving floods: leaf gas films improve O2 and CO2 exchange, root aeration, and growth of completely submerged rice. Plant J. 58, 147–156. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03769.x

Prins, H. B. A., Elzenga, J. T. M. (1989). Bicarbonate utilization: function and mechanism. Aquat. Bot. 34, 59–83. doi: 10.1016/0304-3770(89)90050-8

Raskin, I., Kende, H. (1983). How does deep water rice solve its aeration problem? Plant Physiol. 72, 447–454. doi: 10.1104/pp.72.2.447

Rich, S. M., Pedersen, O., Ludwig, M., Colmer, T. D. (2013). Shoot atmospheric contact is of little importance to aeration of deeper portions of the wetland plant Meionectes brownii; submerged organs mainly acquire O2 from the water column or produce it endogenously in underwater photosynthesis. Plant Cell Environ. 36, 213–223. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2012.02568.x

Schneider, C. A., Rasband, W. S., Eliceiri, K. W. (2012). NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods 9, 671–675. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2089

Setter, T., Kupkanchanakul, T., Kupkanchanakul, K., Bhekasut, P., Wiengweera, A., Greenway, H. (1987). Concentrations of CO2 and O2 in floodwater and in internodal lacunae of floating rice growing at 1–2 metre water depths. Plant Cell Environ. 10, 767–776. doi: 10.1111/1365-3040.ep11604764

Setter, T. L., Waters, I., Wallace, I., Bekhasut, P., Greenway, H. (1989). Submergence of rice I. Growth and photosynthetic response to CO2 enrichment of floodwater. Aust. J. Plant Physiol. 16, 251–263. doi: 10.1071/PP9890251

Sikorska, D., Papierowska, E., Szatyłowicz, J., Sikorski, P., Suprun, K., Hopkins, R. J. (2017). Variation in leaf surface hydrophobicity of wetland plants: the role of plant traits in water retention. Wetlands 37, 997–1002. doi: 10.1007/s13157-017-0924-2

Smart, R., Barko, J. (1985). Laboratory culture of submersed freshwater macrophytes on natural sediments. Aquat. Bot. 21, 251–263. doi: 10.1016/0304-3770(85)90053-1

Taylor, S. A., Smith, W. K. (2017). “Effect of increased salinity exposure on photosynthetic indicators and water status of bald cypress (Taxodium distichum) seedlings”. In: RURALS: Review of Undergraduate Research in Agricultural and Life Sciences 11 (1), 1. Available at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/rurals/vol11/iss1/1.

Teakle, N. L., Colmer, T. D., Pedersen, O. (2014). Leaf gas films delay salt entry and enhance underwater photosynthesis and internal aeration of M elilotus siculus submerged in saline water. Plant Cell Environ. 37, 2339–2349. doi: 10.1111/pce.12269

Verboven, P., Pedersen, O., Ho, Q. T., Nicolai, B. M., Colmer, T. D. (2014). The mechanism of improved aeration due to gas films on leaves of submerged rice. Plant Cell Environ. 37, 2433–2452. doi: 10.1111/pce.12300

Vervuren, P., Beurskens, S., Blom, C. (1999). Light acclimation, CO2 response and long-term capacity of underwater photosynthesis in three terrestrial plant species. Plant Cell Environ. 22, 959–968. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3040.1999.00461.x

Vervuren, P. J. A., Blom, C. W. P. M., De Kroon, H. (2003). Extreme flooding events on the Rhine and the survival and distribution of riparian plant species. J. Ecol. 91, 135–146. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2745.2003.00749.x

Wang, C., Li, C., Wei, H., Xie, Y., Han, W. (2016). Effects of long-term periodic submergence on photosynthesis and growth of Taxodium distichum and Taxodium ascendens saplings in the hydro-fluctuation zone of the Three Gorges Reservoir of China. PloS One 11, e0162867. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0162867

Wang, T., Wei, H., Ma, W., Zhou, C., Chen, H., Li, R., et al. (2019). Response of Taxodium distichum to winter submergence in the water-level-fluctuating zone of the Three Gorges Reservoir region. J. Freshw. Ecol. 34, 1–17. doi: 10.1080/02705060.2018.1470041

Wang, Z., Yin, M., Creech, D. L., Yu, C. (2022). Microsporogenesis, pollen ornamentation, viability of stored Taxodium distichum var. distichum pollen and its feasibility for cross breeding. Forests 13, 694. doi: 10.3390/f13050694

Winkel, A., Colmer, T. D., Ismail, A. M., Pedersen, O. (2013). Internal aeration of paddy field rice (O ryza sativa) during complete submergence–importance of light and floodwater O 2. New Phytol. 197, 1193–1203. doi: 10.1111/nph.12048

Winkel, A., Colmer, T. D., Pedersen, O. (2011). Leaf gas films of Spartina anglica enhance rhizome and root oxygen during tidal submergence. Plant Cell Environ. 34, 2083–2092. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2011.02405.x

Winkel, A., Herzog, M., Konnerup, D., Floytrup, A. H., Pedersen, O. (2017). Flood tolerance of wheat–the importance of leaf gas films during complete submergence. Funct. Plant Biol. 44, 888–898. doi: 10.1071/FP16395

Winkel, A., Pedersen, O., Ella, E., Ismail, A. M., Colmer, T. D. (2014). Gas film retention and underwater photosynthesis during field submergence of four contrasting rice genotypes. J. Exp. Bot. 65, 3225–3233. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eru166

Winkel, A., Visser, E. J., Colmer, T. D., Brodersen, K. P., Voesenek, L. A., Sand-Jensen, K., et al. (2016). Leaf gas films, underwater photosynthesis and plant species distributions in a flood gradient. Plant Cell Environ. 39, 1537–1548. doi: 10.1111/pce.12717

Yang, Q., Bejarano, M. D., Ma, W., Salam, M., Pu, B., Wei, H., et al. (2023). Effects of long-term submergence on non-structural carbohydrates and N and P concentrations of Salix matSudana along the Three Gorges Reservoir. Hydrobiologia 850, 2035–2047. doi: 10.1007/s10750-023-05215-5

Ye, Z. P., Suggett, D. J., Robakowski, P., Kang, H. J. (2013). A mechanistic model for the photosynthesis–light response based on the photosynthetic electron transport of photosystem II in C3 and C4 species. New Phytol. 199, 110–120. doi: 10.1111/nph.12242

Yu, S., Sheng, L., Zhan, L., Niluo, Z. (2021). Analysis of temperature variation characteristics in the three gorges reservoir area after impoundment of the three gorges dam. Acta Ecologica Sin. 41, 384–389. doi: 10.1016/j.chnaes.2020.06.003

Zhang, J., Sun, H., Gao, D., Qiao, L., Liu, N., Li, M., et al. (2020). Detection of canopy chlorophyll content of corn based on continuous wavelet transform analysis. Remote Sens. 12, 2741. doi: 10.3390/rs12172741

Keywords: bald cypress, contact angle, flood tolerance, gas films, hydrophobicity, swamp cypress, low oxygen quiescence syndrome

Citation: Guo J, Xue J, Yin Y, Pedersen O and Hua J (2024) Response of underwater photosynthesis to light, CO2, temperature, and submergence time of Taxodium distichum, a flood-tolerant tree. Front. Plant Sci. 15:1355729. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2024.1355729

Received: 14 December 2023; Accepted: 04 March 2024;

Published: 19 March 2024.

Edited by:

Zi-Piao Ye, Jinggangshan University, ChinaCopyright © 2024 Guo, Xue, Yin, Pedersen and Hua. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ole Pedersen, b3BlZGVyc2VuQGJpby5rdS5kaw==; Jianfeng Hua, amZodWFAY25iZy5uZXQ=

Jinbo Guo

Jinbo Guo Jianhui Xue

Jianhui Xue Yunlong Yin1,3

Yunlong Yin1,3 Ole Pedersen

Ole Pedersen Jianfeng Hua

Jianfeng Hua