- 1College of Horticulture and Landscape Architecture, Yangzhou University, Yangzhou, China

- 2Joint International Research Laboratory of Agriculture and Agri−Product Safety of Ministry of Education of China, Yangzhou University, Yangzhou, China

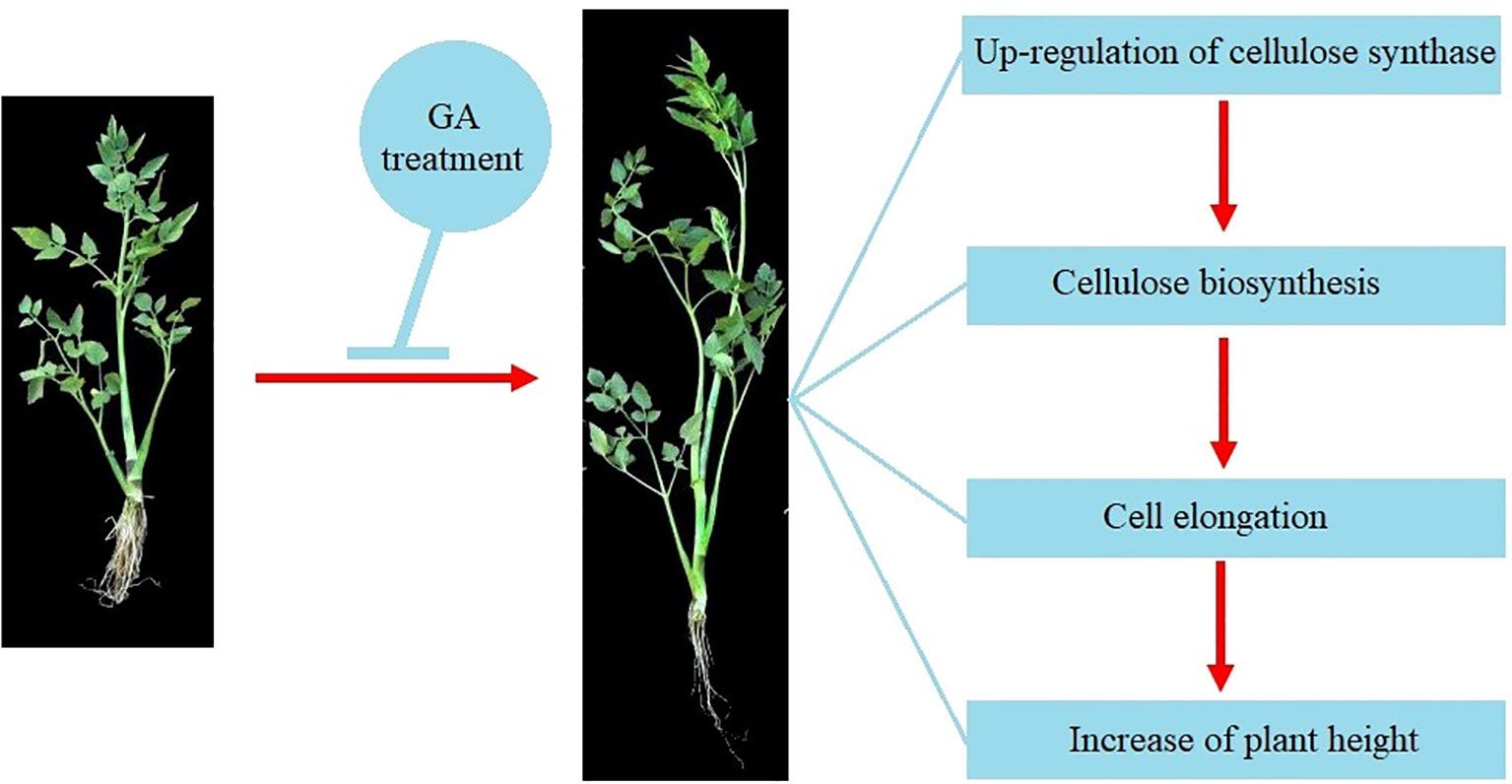

Oenanthe javanica (Blume) DC. is a popular vegetable with unique flavor and its leaf is the main product organ. Gibberellin (GA) is an important plant hormone that plays vital roles in regulating the growth of plants. In this study, the plants of water dropwort were treated with different concentrations of GA3. The plant height of water dropwort was significantly increased after GA3 treatment. Anatomical structure analysis indicated that the cell length of water dropwort was elongated under exogenous application of GA3. The metabolome analysis showed flavonoids were the most abundant metabolites and the biosynthesis of secondary metabolites were also regulated by GA3. The exogenous application of GA3 altered the gene expressions of plant hormone signal transduction (GID and DELLA) and metabolites biosynthesis pathways to regulate the growth of water dropwort. The GA contents were modulated by up-regulating the expression of GA metabolism gene GA2ox. The differentially expressed genes related to cell wall formation were significantly enriched. A total of 22 cellulose synthase involved in cellulose biosynthesis were identified from the genome of water dropwort. Our results indicated that GA treatment promoted the cell elongation by inducing the expression of cellulose synthase and cell wall formation in water dropwort. These results revealed the molecular mechanism of GA-mediated cell elongation, which will provide valuable reference for using GA to regulate the growth of water dropwort.

1 Introduction

Water dropwort [Oenanthe javanica (Blume) DC.] is a perennial aquatic herb in the Apiaceae family, which is mainly grown in tropical and temperate regions (Lu and Li, 2019). Water dropwort contains various bioactive substances and it is well known to have many medicinal effects, such as promoting digestion, reducing blood pressure and blood sugar (Yang et al., 2014; Kim et al., 2016). Water dropwort is also consumed as a popular vegetable because it is rich in vitamins, proteins, dietary fibers, and flavonoids (Feng et al., 2018). Fresh stems and petioles are the main edible parts of water dropwort, which has a unique aroma and taste (Park et al., 2015; Feng et al., 2022). The yield of water dropwort was closely related to the petiole length; thus, GA is an effective way to improve the petiole length in the production of water dropwort.

Gibberellins (GAs) are important plant hormones derived from the tetracyclic backbone of diterpenic acids, which have multiple functions in regulating various developmental processes and environmental responses in plants (Sponsel, 2016). The biosynthesis and signal transduction pathway of GAs in plants has been extensively presented (Hedden, 2020). The geranylgeranyl diphosphate (GGPP) was converted into ent-kaurene catalyzed by ent-copalyl diphosphate synthase (CPS) and ent-kaurene synthase (KS). GA is then synthesized from ent-kaurene by various enzymes in plants, including ent-kaurene oxidase (KO), ent-kaurenoic acid oxidase (KAO), GA20-oxidase (GA20ox) and GA3-oxidase (GA3ox). The inactivation of bioactive GAs was regulated by the GA2-oxidase (GA2ox). The signal transduction of GAs involves many proteins, such as GIBBERELLIN INSENSITIVE DWARF1 (GID1), DELLA, specific ubiquitin E3 ligase complex (SCFSLY1/GID2/SNE), and SLEEPY1 (SLY1) (Yamaguchi, 2008).

In plants, GAs play vital roles in many biological processes (Daviere and Achard, 2013). Specially, GAs regulate the plant height by promoting the stem elongation (Ohtaka et al., 2020; Li et al., 2023). Altering GA levels by exogenous application or genetic approaches was widely used to promote yields and productivity in crops production (Gao and Chu, 2020). The semidwarf varieties derived from GA biosynthetic genes semidwarf1 (GA20ox2) altered the GAs contents and resulted in the high-yielding performance in rice production, which was extensively applied in the 20th century’s Green Revolution (Spielmeyer et al., 2002). In addition, exogenous application of GAs was also an effective method for regulating the growth of plants (Pearce et al., 2013; Cai et al., 2018). Previous study indicated that the height and biomass of Neolamarckia cadamba were increased after GAs treatment (Li et al., 2022). However, the effects of GAs application on the growth and metabolite accumulation of water dropwort have not been reported and the suitable application concentration of GAs was still unknown.

In this study, the plants of water dropwort were treated with different concentrations of GA3 and GA inhibitor. The effects of various treatments on the growth of water dropwort were determined. The metabolomic and transcriptomic analysis were conducted to identify the metabolites and key regulatory genes in water dropwort under GAs and uniconazole treatments. This study increases our understanding for the regulatory mechanism of GA-mediated cell elongation and provides the suitable approach to regulate the height and metabolites of water dropwort.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Plant materials and experimental treatments

The water dropwort variety ‘Fuqin No.1’ was used as plant material in this study, which was stored in the aquatic vegetable experimental base of Yangzhou University (32°39′N, 119°42′E). The water dropwort was grown in the pots (38 cm × 28 cm) containing fertile soil under natural condition. The water dropwort was irrigated with water every 5 days and the 30-day-old plants were treated with different concentrations of GA3. The treatments of T1, T2, T3, T4 represented 40 mg/L, 80 mg/L, 120 mg/L, 160 mg/L of GA3, respectively. T5 indicated the treatment of uniconazole (a gibberellin inhibitor, 50 mg/L). The water dropwort treated with distilled water was set as control group (CK). Each treatment was performed for three biological replicates. The 65-day-old plants of water dropwort were measured and the samples were harvested for further analysis.

2.2 Anatomical structure analysis

The petioles of water dropwort under different treatments were sampled for anatomical structure analysis. The middle part of petioles was cut into 3 mm and the tissue structure was immobilized in the phosphate buffer solution containing 2.5% of glutaraldehyde (pH = 7.2). The slices were dewaxed and dehydrated with xylene and ethanol, respectively. The samples were then stained by the safranin-O (1%) for 2 h and cleaned by ethanol (Que et al., 2018). The anatomical structure of water dropwort was observed by light microscope. The Image J software was used to detect the cell length of water dropwort under different treatments (Schindelin et al., 2015).

2.3 Determination of GAs contents

To further investigate the changes of GAs contents in water dropwort, the petioles of CK, T2, and T5 groups were collected for determination of GAs contents. The samples of water dropwort were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored in -80 °C refrigerator. The samples were then sent to MetWare (http://www.metware.cn/) for the determination of GAs contents. The measurement was performed using AB Sciex QTRAP 6500 LC-MS/MS platform (He et al., 2020).

2.4 Metabolites analysis

The broadly targeted metabolomics of water dropwort were conducted in MetWare (http://www.metware.cn/). Briefly, the plant samples were first freeze-dried and crushed. Fifty mg of lyophilized powder were dissolved in methanol solution (70%). The samples were then centrifugated and filtrated for further UPLC-MS/MS analysis. Four μL of the above extraction were injected into the UPLC-ESI-MS/MS system. The effluent was further analyzed by an ESI-triple quadrupole-linear ion trap (QTRAP)-MS (Li et al., 2021). The differentially expressed metabolites (DEMs) among different groups were identified based on the variable importance in projection (VIP) and fold change (FC) values. The VIP values were obtained from the OPLS-DA model. The metabolites with a VIP value ≥ 1 and FC value ≥2 or ≤0.5 were determined as DEMs (Cao et al., 2022). The identified metabolites were annotated based on the KEGG database (http://www.kegg.jp/kegg/compound/).

2.5 Transcriptome analysis

The petioles of water dropwort from three biological replicates under CK, T2, and T5 treatments were sampled and frozen in liquid nitrogen for transcriptome analysis (Zhang et al., 2017). The purity and integrity of extracted total RNA was detected by NanoDrop 2000 and Agient2100/LabChip GX, respectively. The RNA-seq libraries were constructed by Biomarker Technologies Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). The constructed libraries were sequenced by the Illumina NovaSeq6000 platform. Based on the high-quality genome of water dropwort (Liu et al., 2023), the clean reads of transcriptome were compared to the reference genome by the HISAT2 software (Kim et al., 2015). The expression levels of the gene were calculated based on the read counts and normalized by the fragments per kilobase of transcript per million fragments mapped (FPKM) method (Trapnell et al., 2010). The transcriptome analysis of water dropwort was conducted on the BMKCloud (www.biocloud.net). The raw data has been deposited in SRA database with the ID of PRJNA977200.

2.6 Identification of cellulose synthase family in water dropwort

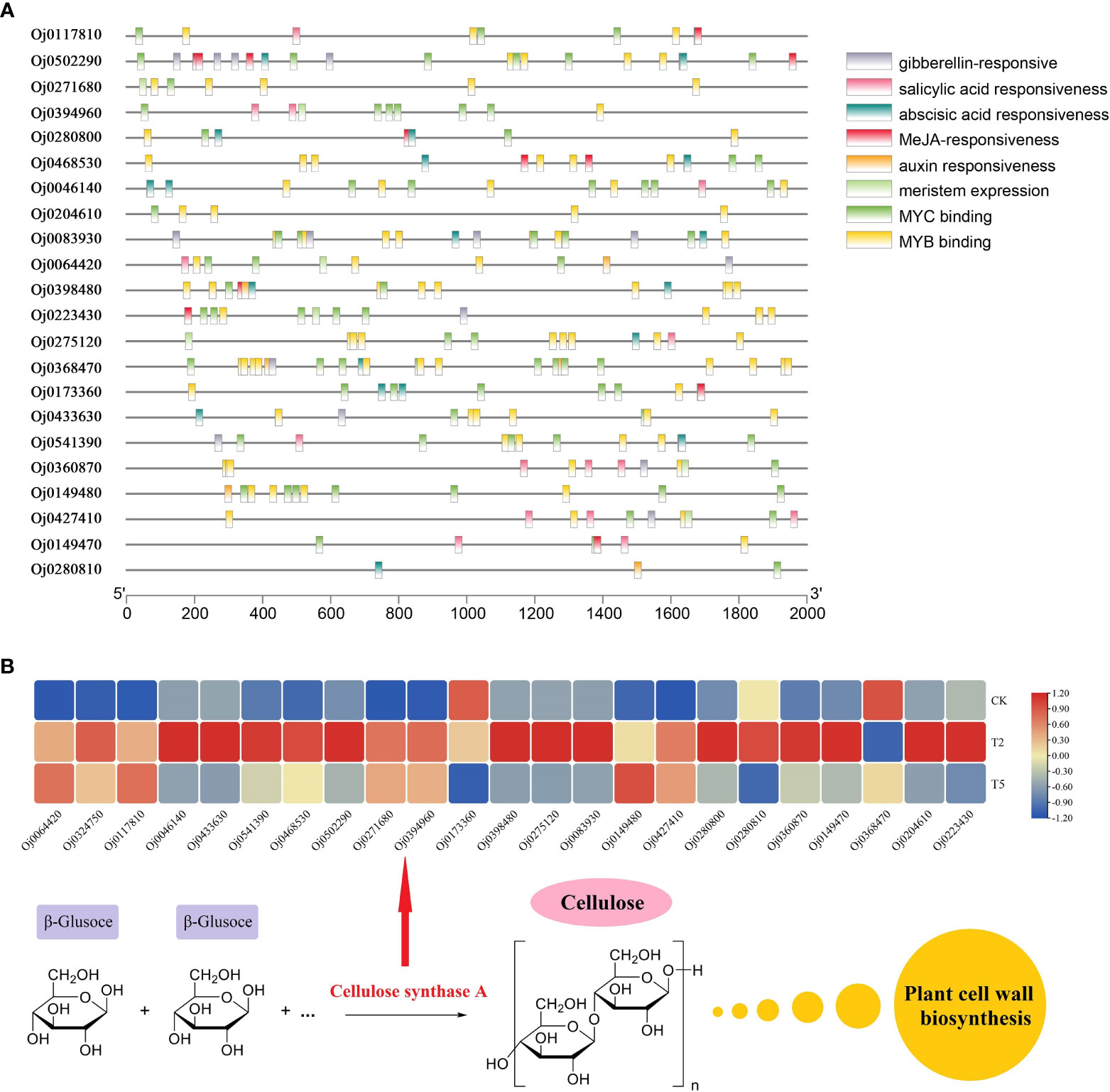

In order to identify the members of the cellulose synthase (CES) family in water dropwort, the HMM model (PF03552) was used to search the CES family member from water dropwort by TBtools (Chen et al., 2020). The obtained candidate CES family sequences were further determined by analysis of conserved domains in Pfam databases (Finn et al., 2014). The sequences of Arabidopsis CES family were downloaded from The Arabidopsis Information Resource (TAIR) (Rhee et al., 2003). The protein sequences of CES family from water dropwort and Arabidopsis were used to construct the phylogenetic tree by MEGA 7.0 using neighbor-joining method (Kumar et al., 2016). The promoter sequence (upstream 2000 bp) of different CESA family genes were extracted from the genome of water dropwort (Liu et al., 2023). The cis-acting elements analysis of promoter was performed on the PlantCARE (Lescot et al., 2002) and the different cis-acting elements were visualized by TBtools (Chen et al., 2020).

3 Results

3.1 Growth analysis of water dropwort under GA treatment

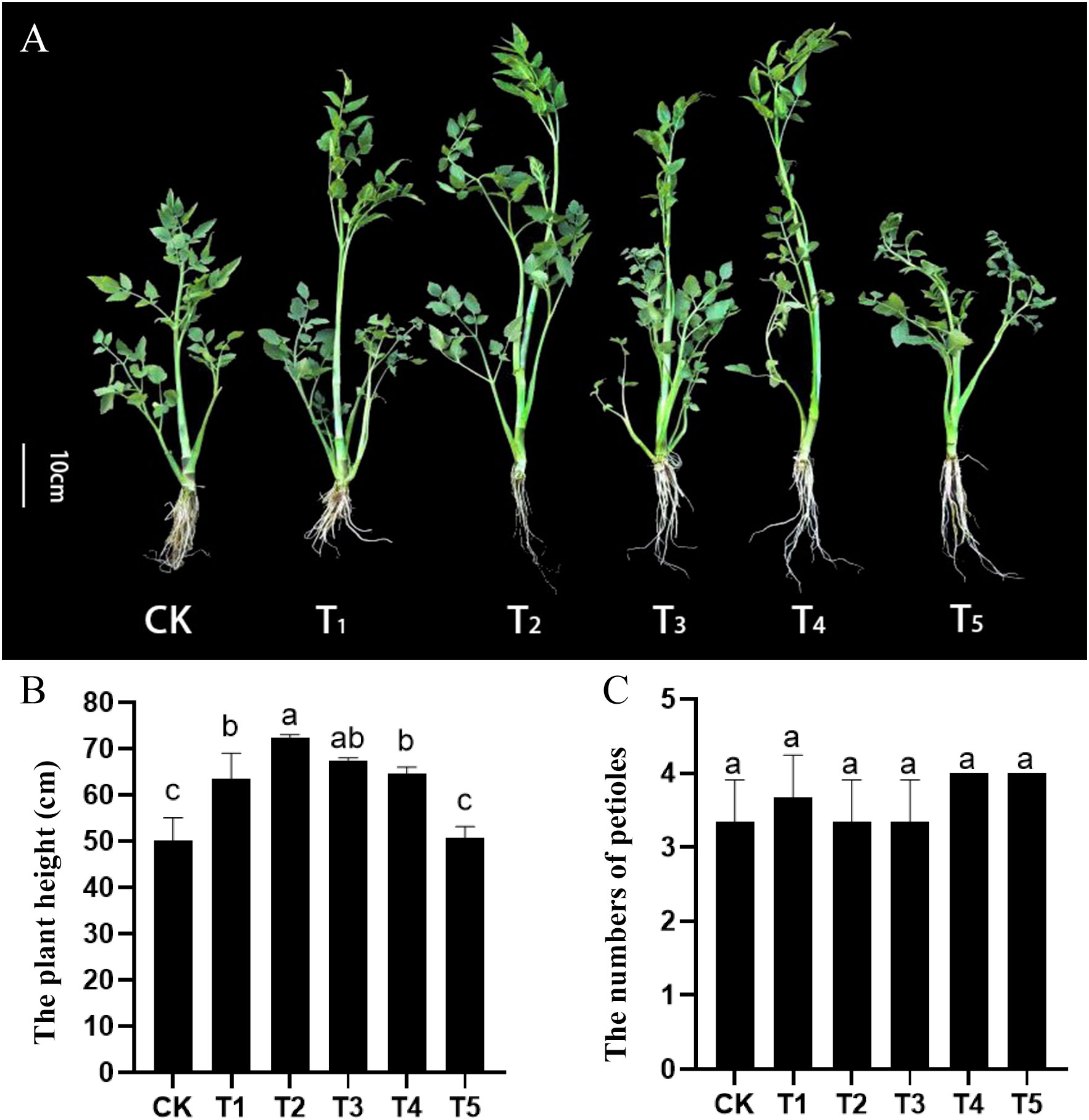

To investigate the effects of GA treatment on the growth of water dropwort, the GA3 with five concentrations (0, 40, 80, 120, 160 mg/L) and uniconazole (GA biosynthesis inhibitor) were used to treat water dropwort plants. The water dropwort was measured and sampled after 30 days of treatment. The growth of water dropwort was influenced by GA treatment (Figure 1A). Plant height of water dropwort was significantly increased after GA3 treatment, and the GA3 with concentration of 80 mg/L (T2) showed the most significant effect on the growth of water dropwort (Figure 1B). The effects of GA3 and uniconazole on the petiole numbers were not obvious (Figure 1C).

Figure 1 Effects of exogenous GA3 and uniconazole treatments on the growth of water dropwort (A) The growth status of water dropwort under GA3 and uniconazole treatments. (B) The plant heights under GA3 and uniconazole treatments. (C) The petioles numbers of under GA3 and uniconazole treatments. White lines in the left represent 10 cm in that pixel. CK, T1, T2, T3, and T4 represent 0, 40, 80, 120, 160 mg/L exogenous GA3 treatment, respectively. T5 represent the exogenous uniconazole (a gibberellin inhibitor) treatment. The columns with different letters indicate the significant differences at P < 0.05.

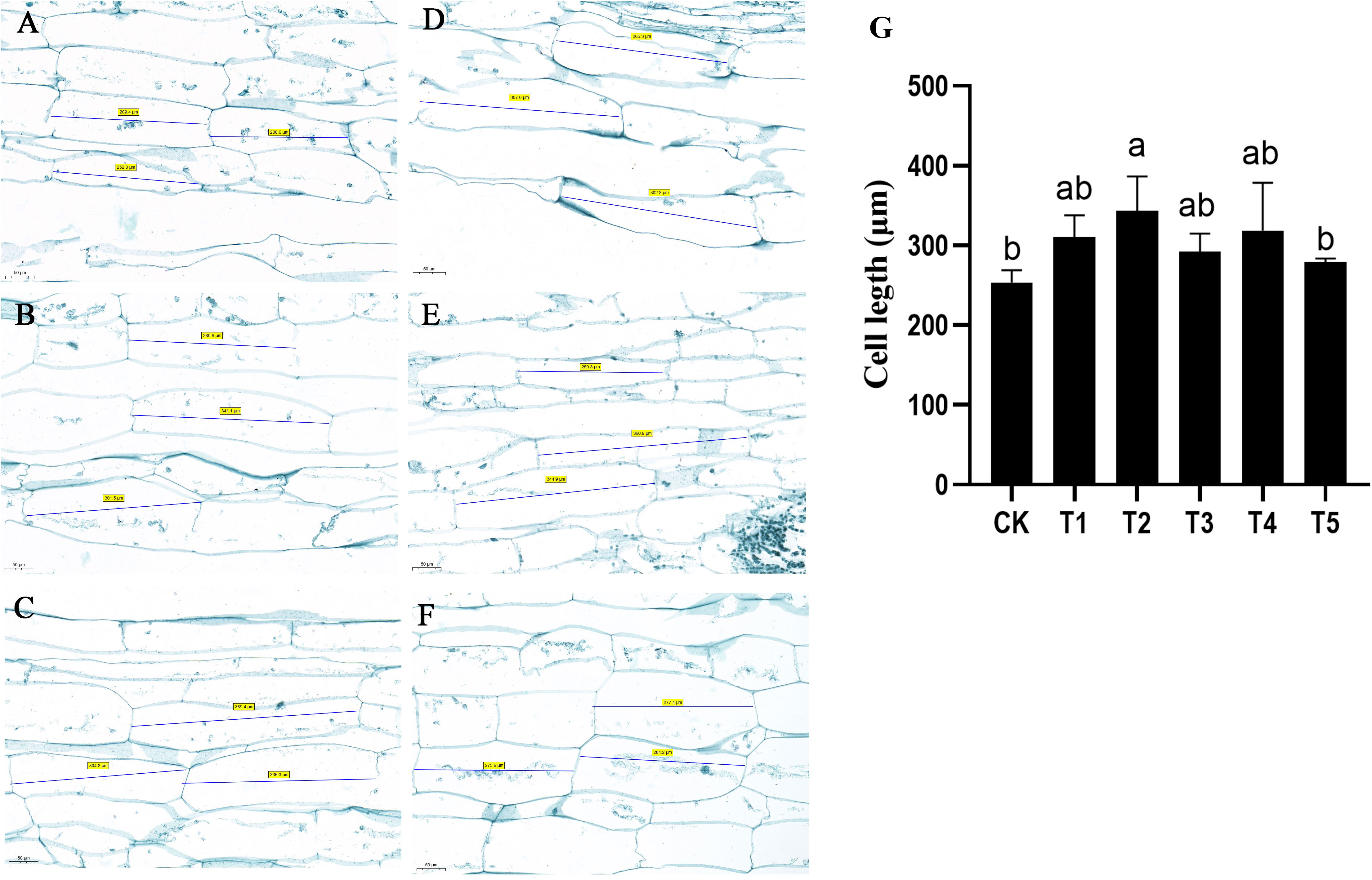

3.2 Anatomical structure analysis of water dropwort

The anatomical structure of petioles under GA and uniconazole treatments was examined. The results indicated that the cell length of petiole was significantly increased after GA treatment (Figures 2A–F). The cell length of water dropwort petiole without any treatment was approximately 253.6 μm. By contrast, the cell length of petiole with 80 mg/L of GA3 treatment was 343.5 μm, which was significantly longer than CK and uniconazole treatments (Figure 2G). These results suggested that the GA-mediated increase of plant height was mainly due to cell elongation of water dropwort. Compared with other concentrations of GA treatments, the T2 (80 mg/L) treatment had the most significant promoting effect on the cell length of water dropwort.

Figure 2 Effects of exogenous GA3 treatment on the cell length of water dropwort Longitudinal slice images of the water dropwort under CK (A), T1 (B), T2 (C), T3 (D), T4 (E), and T5 (F). The ‘number’ in the picture represents the cell length. (G) The statistic analysis of cell length. The columns with different letters indicate the significant differences at P < 0.05.

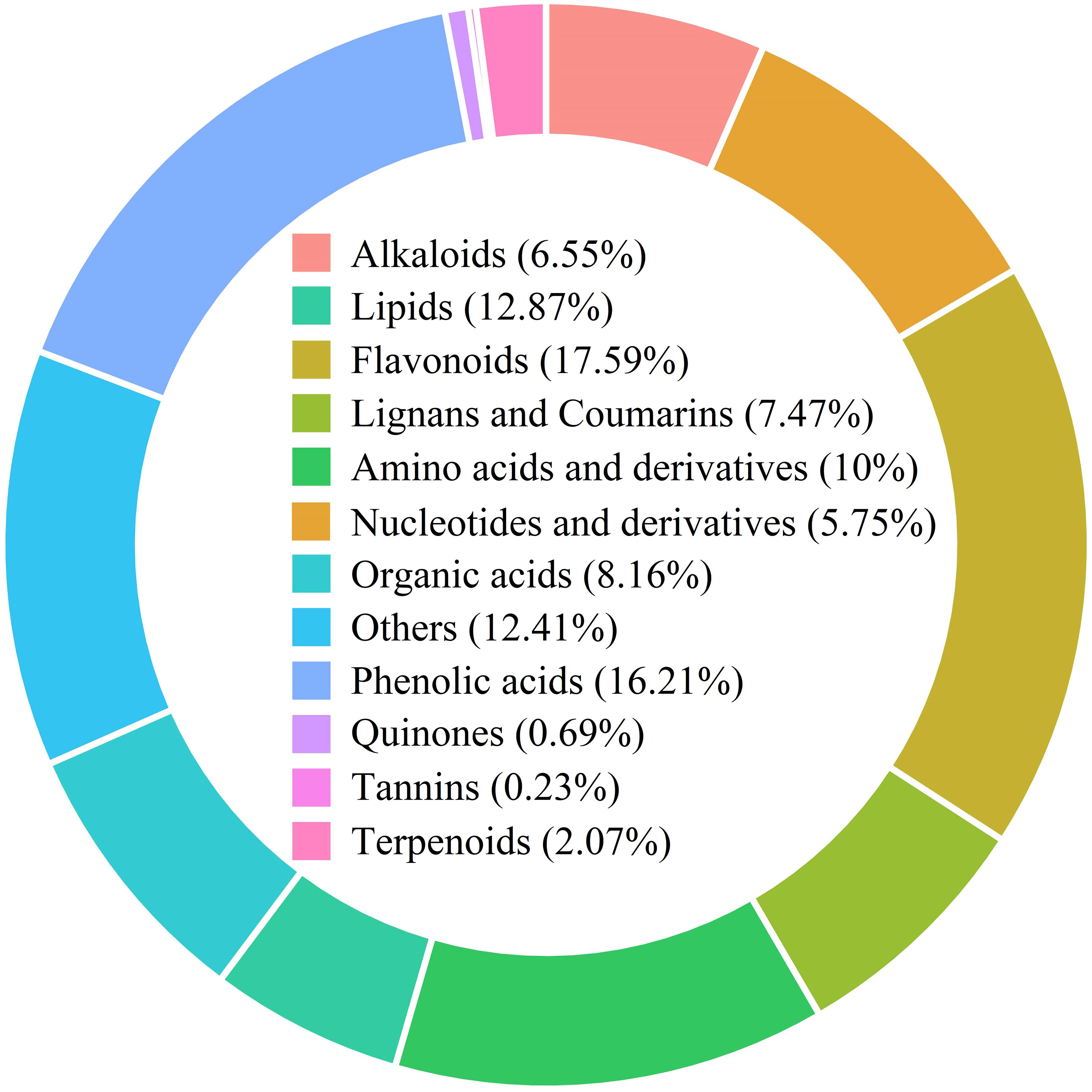

3.3 Metabolites analysis of water dropwort

The metabolomic analysis of water dropwort was performed to understand the metabolites changes under GA treatment. A total of 870 metabolites were identified from all samples of water dropwort (Supplementary Table S1). The detected metabolites can be classified into different categories. The flavonoids accounted for the highest proportion of 17.59%, followed by phenolic acids, amino acids and derivatives, and organic acids, which accounted for 16.21%, 10% and 8.16% respectively (Figure 3). Cluster analysis indicated that different metabolites accumulated in CK, T2, and T5 treatments.

Figure 3 The metabolites identified from water dropwort under GA3 treatment based on the metabolome analysis.

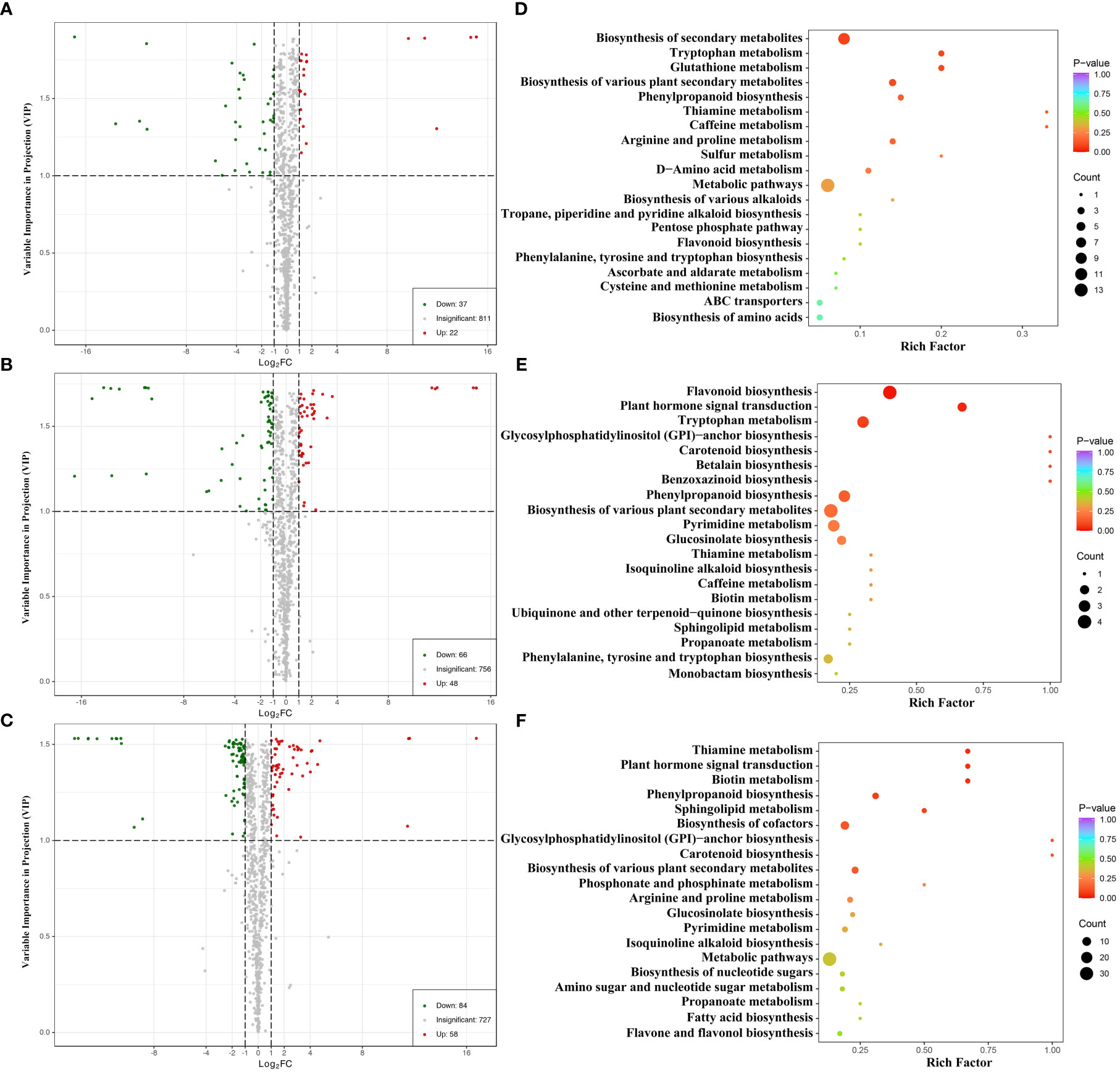

3.4 Differentially expressed metabolites analysis

The differentially expressed metabolites (DEMs) among CK, T2, and T5 groups of water dropwort were analyzed (Supplementary Table S2). The VIP based on the OPLS-DA model and FC values were combined to identify the DEMs in different groups of water dropwort (Figures 4A–C). The results indicated that 59 DEMs were identified in CK and T2 group, including 37 down-regulated and 22 up-regulated DEMs. A total of 114 DEMs were identified in CK and T5 group, including 66 down-regulated and 48 up-regulated DEMs. A total of 142 DEMs were identified in CK and T5 group, including 84 down-regulated and 58 up-regulated DEMs. The KEGG enrichment analysis of DEMs in different groups of water dropwort was also conducted. The results indicated that the metabolic pathways and biosynthesis of secondary metabolites were the most abundant pathways (Figures 4D–F).

Figure 4 The differential expressed metabolites analysis of water dropwort under GA3 treatment (A–C): Volcanic map of differential metabolite analysis in CK, T2, and T5 groups. (D–F): The enrichment analysis of differential metabolite in CK, T2, and T5 groups.

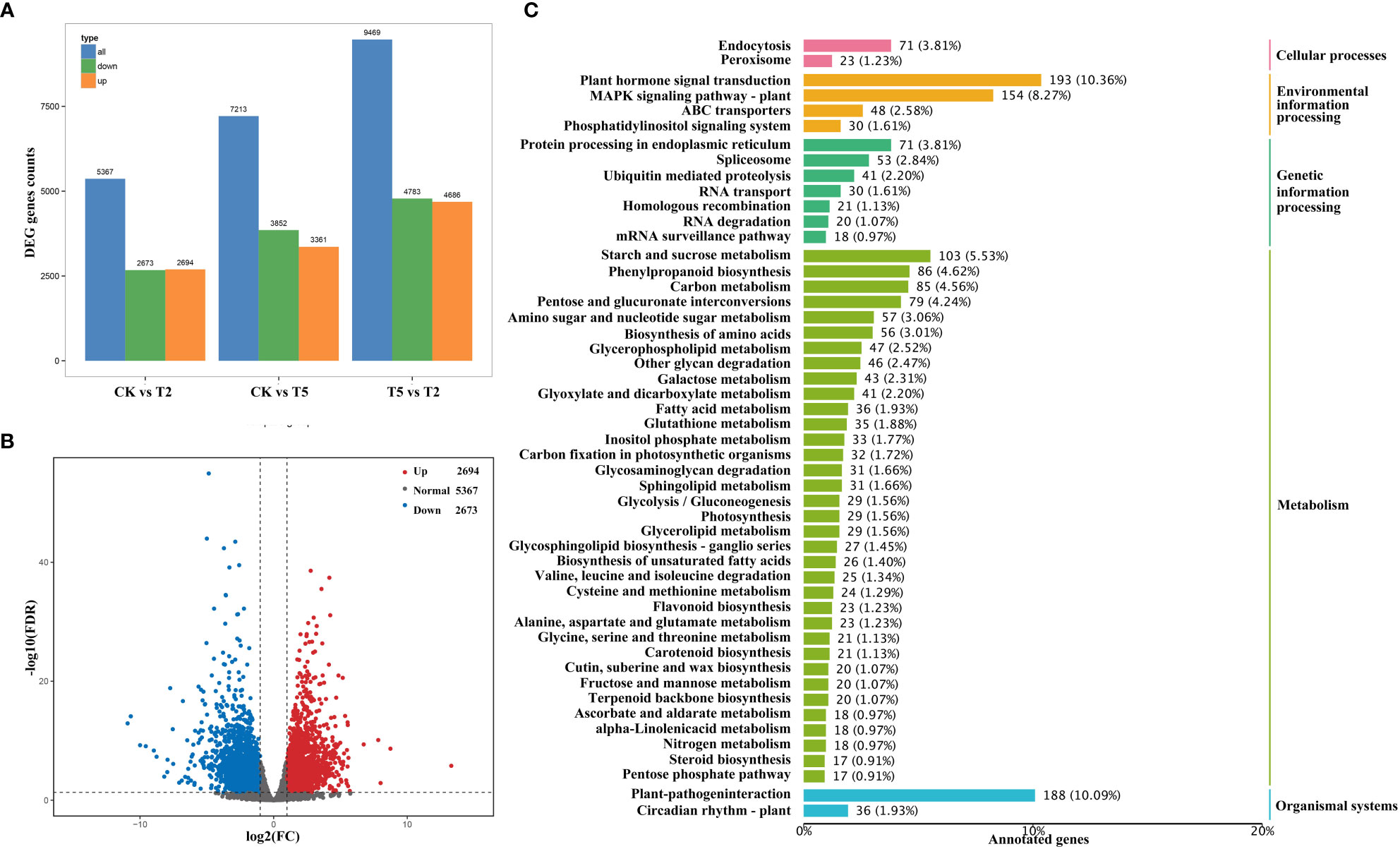

3.5 Transcriptomic analysis of water dropwort

To identify the gene expression profiles under exogenous GA treatment, the transcriptome analysis of water dropwort was conducted. A total of 63.98 Gb clean data were obtained and the percentage of Q30 bases of each sample was no less than 92.52% (Supplementary Table S3). The mapped efficiency of different samples with reference genome ranged from 91.20% to 94.46%. The differential expressed analysis of water dropwort under different treatments was performed (Figure 5A). The volcano plot indicated that a total of 5,367 DEGs were identified between CK and T2 treatments, including 2,694 up-regulated DEGs and 2,673 down-regulated DEGs (Figure 5B).

Figure 5 The transcriptome analysis of water dropwort under GA3 treatment (A) Statistical analysis of differentially expressed genes. (B) Volcanic map of differentially expressed genes analysis. (C) The KEGG enrichment analysis of differentially expressed genes in water dropwort.

The annotation and enrichment analysis of DEGs was conducted according to the GO and KEGG databases. The GO enrichment analysis mainly includes the biological process, cellular component, and molecular function. As for biological process branch, the ‘carbohydrate metabolic process’ had the most abundant DEGs after exogenous GA treatment. The components involved in cell wall were also identified in the biological process branch, such as ‘cell wall organization’ and ‘cell wall biogenesis’ (Supplementary Figure S1). In cellular branch, the plasma membrane had the largest number of DEGs in all components. In addition, the cell wall-related components were also detected from the branch. The exogenous GA3 may promote plant elongation by regulating cell-related life processes in water dropwort. KEGG annotation and enrichment analysis were conducted to identify the metabolic pathways of water dropwort (Figure 5C). The DEGs were most enriched in the ‘plant hormone signal transduction’ pathway after exogenous GA treatment. This suggested that the exogenous GA treatment could regulate plant growth by affecting various hormone signaling pathways. In addition, the DEGs were also abundantly enriched in many metabolisms, including ‘starch and sucrose metabolism’, ‘phenylpropanoid biosynthesis’, and ‘carbon metabolism’.

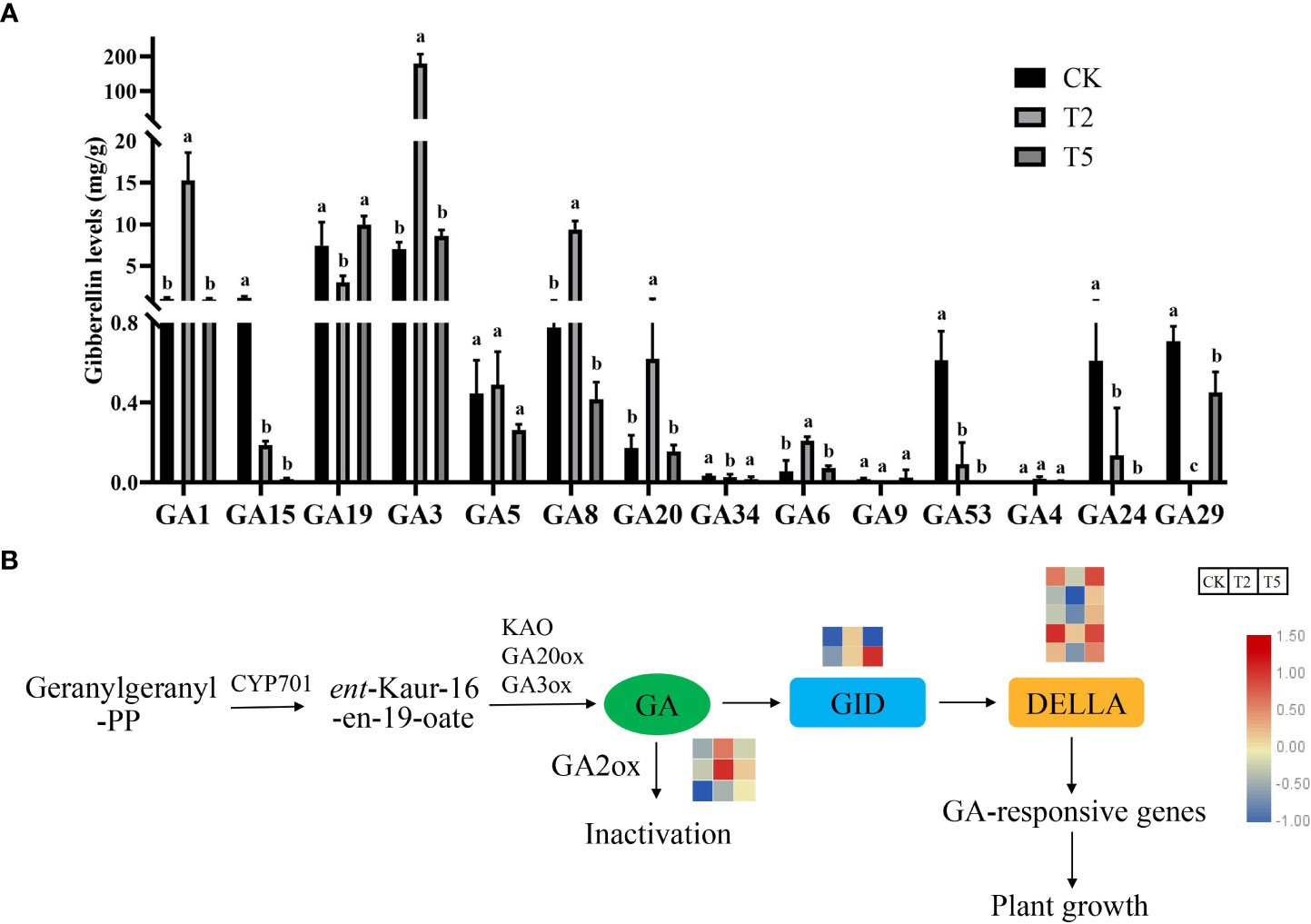

3.6 The GAs contents and DEGs related to GA biosynthetic pathway

To investigate the effect of exogenous GA3 treatment on different kinds of GA, the GAs contents of CK, T2, and T5 were determined. Compared with CK and T5 treatments, the GA3 content under T2 treatment was significantly increased after exogenous GA3 treatment. In addition, the contents of GA1, GA4, and GA8 were also increased after GA3 treatment. However, some GAs were significantly decreased after GA3 treatment, such as GA15, GA19, GA24, GA29, and GA53 (Figure 6A). The transcriptomic analysis indicated that the GA biosynthesis and signaling transduction was significantly influenced by the exogenous GA treatment. GAs is synthesized from the geranylgeranyl-PP (GGPP). The expression trends of GA biosynthesis genes (KAO, GA20ox, GA3ox) in different groups varied. The transcripts of GA metabolism-related gene (GA2ox) were up-regulated after exogenous GA treatment. The active GAs can bind with GID proteins to form a complex in plants. The GID genes were up-regulated and DELLA genes were down-regulated after exogenous GA treatment (Figure 6B).

Figure 6 Effects of exogenous GA3 treatment on the various gibberellin contents and the gene expressions (A) The contents of different kinds of GA under GA3 treatment. (B) The expression of differentially expressed genes in GA biosynthesis and signaling transduction pathway. The columns with different letters indicate the significant differences at P < 0.05.

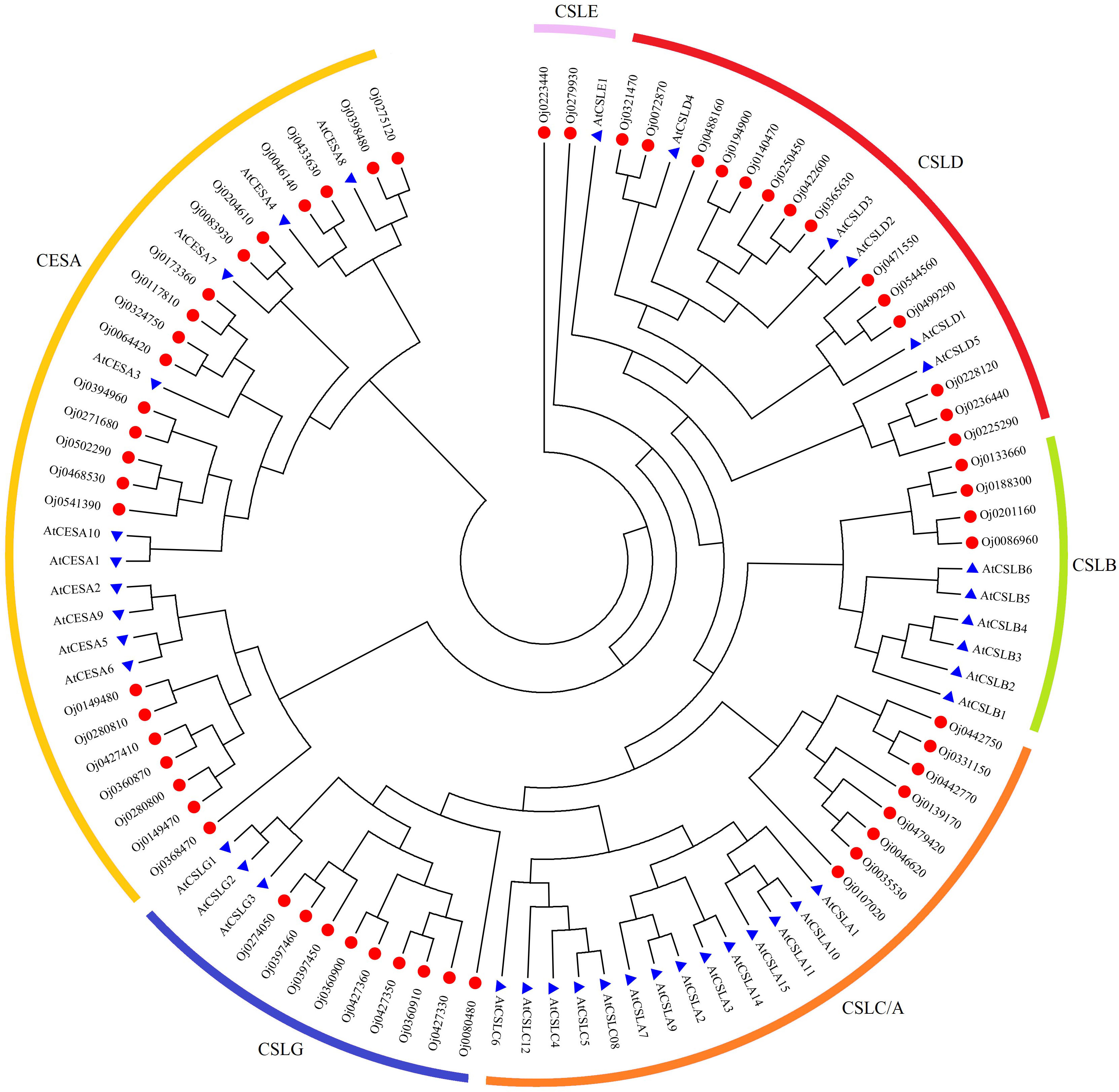

3.7 Identification of cellulose synthase family in water dropwort

The biosynthesis of cellulose was related to the cell wall formation in plants. A total of 59 cellulose synthase (CES) family members were identified from the genome of water dropwort. Based on the phylogenetic relationships with Arabidopsis, the CES proteins of water dropwort can be divided into different cellulose subfamilies, including synthase (CESA) and cellulose synthase-like (CSLA/B/C/D/E/G) subfamilies (Figure 7).

Figure 7 Phylogenetic analysis of cellulose synthase genes family from Arabidopsis and water dropwort.

A total of 22 members were detected from CESA subfamily, and the cis-acting elements analysis were conducted by PlantCARE (Figure 8A). The gibberellin-responsive elements were discovered in the promoters of CESA family genes, suggesting these CESA genes may be regulated by the gibberellin signal in water dropwort. In addition, the CESA genes also contained abundant other hormone-related elements, such as auxin responsiveness elements, MeJA responsiveness elements, and abscisic acid responsiveness elements. The biosynthesis of cellulose was catalyzed by the CESA proteins, the transcriptions of CESA genes were analyzed in water dropwort (Figure 8B). The results indicated that most CESA genes were up-regulated under GA3 treatment. The changes of gene expression promoted the biosynthesis of cellulose, which further provided the materials for the cell wall in the cell elongation of water dropwort under GA3 treatment.

Figure 8 The cis-responsive elements and expression analysis of CESA family genes (A) The cis-responsive elements analysis of the promoters of CESA family genes. (B) The expressions of CESA family genes under CK, T2, and T5 treatments.

4 Discussion

Water dropwort was a perennial aquatic herb in the Apiaceae family, which is consumed as vegetable in China (Feng et al., 2018). Currently, research on water dropwort mainly focus on the regulation of flavonoids and the flavor-related substances (Kumar et al., 2021; Kumar et al., 2022; Liu et al., 2023). The published high-quality genome sequence also provided basis for the fundamental and applied research of water dropwort (Liu et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2023). Petiole and stem were the main editable parts of water dropwort. Trying to improve the yield of product organs has become a farming goal in production of water dropwort. Regulation of plant growth by plant hormones is an effective approach in agronomic production (Cai et al., 2014; Sakata et al., 2014). However, the studies aiming at using plant hormones to promote the plant height of water dropwort were still unavailable.

In the current study, the plants of water dropwort were treated with different concentrations of GA3 and uniconazole (a GAs inhibitor). The plant height was significantly increased after exogenous GA3 treatment, which indicated that the GAs mainly affected petiole length, but did not affect petiole number. Anatomical structure analysis indicated that the cell length was increased under T2 treatment. The reason for the lack of difference in cells length between CK and T3, T4, and T5 is mainly due to the fact that the promoting roles of GAs is concentration-dependent. GAs is a common plant hormone first identified from fungus Gibberella fujikuroi, which was investigated to promote the stem elongation in many plants (Eriksson et al., 2000; Claeys et al., 2014). The cell length in the second internode of Neolamarckia cadamba was also significantly increased after exogenous application of GAs (Li et al., 2022). The GA-deficient mutant with dwarf phenotype further proved the roles of GAs in regulating the plant height (Ashikari et al., 1999; Sakamoto et al., 2004). Our results indicated that the GA3 treatment promoted the petiole length by inducing the cell elongation of water dropwort.

To further investigate the changes of metabolites and gene expression under GAs treatment, the metabolome and transcriptome analysis of water dropwort was conducted. Flavonoids were the most abundant metabolites in water dropwort and the metabolome analysis indicated that the DEMs were mainly enriched in the metabolic pathways and biosynthesis of secondary metabolites under GA treatments. The accumulation of flavonoids plays an important role in the medicinal efficacy of water dropwort. The flavonoids extracted from water dropwort have many medicinal functions, such as delay the senescence (Moon et al., 2009), anti-inflammatory (Ahn and Lee, 2017; Wei and Ma, 2021), antioxidant (Seo et al., 2016), and antidiabetic effect (Yang et al., 2000).

The contents of various GAs were also increased after exogenous GA3 treatment. The transcriptome analysis indicated that the GA2ox genes were up-regulated after exogenous GA3 treatment, which inactivates GA (Wuddineh et al., 2015). This is due to the high levels of GAs resulted in the feedback regulation of GAs metabolism genes in plants (Gallego-Giraldo et al., 2008). The GA-mediated regulation in plants usually involves in the cooperative regulation of various plant hormones (Que et al., 2018). In this study, the transcriptome analysis indicated that numerous DEGs were significantly enriched in the plant hormone signal transduction pathway. These results indicated that GAs promoted plant elongation through synergistic regulation of multiple plant hormone signal transduction in plants. Changes of cell wall growth play an important role in the elongation process of plants (Munekata et al., 2022; Petrova et al., 2022). GO enrichment analysis showed that the exogenous GA3 promoted plant elongation by regulating cell-related life processes in water dropwort, such as ‘cell wall organization’ and ‘cell wall biogenesis’.

Cellulose, a natural polysaccharide, is the main component of plant cell walls (Zhong et al., 2019). The biosynthesis of cellulose was catalyzed by cellulose synthase complex (CSC) in plants (Somerville, 2006). The cellulose synthase gene family (CES) in plants is a multi-gene family and 10 CESA genes were found in the Arabidopsis genome (Richmond and Somerville, 2000). The expression of CESA genes in plants can be regulated by different phytohormones-mediated signaling to precipitate the cell wall formation (Huang et al., 2015). In the current study, a total of 22 CESA members was identified from the genome of water dropwort. Multiple hormone-related elements including gibberellin-responsive were discovered from the promoters of CESA genes. Transcriptome analysis showed that the expressions of CESA genes were significantly up-regulated in water dropwort after GA3 treatment. These results suggested that the exogenous GA3 treatment can promote the biosynthesis of cellulose and thereby elongate cells, leading to an increase in plant height (Figure 9). The function of the identified key genes will be our research focus in future work.

5 Conclusion

In the current study, the comprehensive analysis of morphological, metabolome, and transcriptome revealed the effects of exogenous gibberellin on water dropwort. The plant height of water dropwort was significantly increased after exogenous gibberellin treatment. The metabolites and different kinds of GAs were also regulated by exogenous gibberellin treatment. These results provided valuable information for understanding the molecular mechanism of GA-mediated cell elongation in plants. This study also offered a strategy to modulate the growth by using exogenous GAs in the production of water dropwort.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: NCBI BioProject https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/, PRJNA977200.

Author contributions

KF and LL initiated and designed the research. KF, XL, YY, RL, ZL, NS, ZY, SZ, and PW performed the experiments. KF, XL, YY, ZL, and RL analyzed the data. KF and LL contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools. KF wrote the manuscript. LL revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This study was financially supported by the China Agriculture Research System (CARS-24), Jiangsu seed industry revitalization project (JBGS [2021]017), National Natural Science Foundation of China (32102368), Jiangsu Agriculture Science and Technology Innovation Fund [CX(21)3026], and Natural Science Foundation of the Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions of China (21KJB210008).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2023.1225635/full#supplementary-material

References

Ahn, H., Lee, G. S. (2017). Isorhamnetin and hyperoside derived from water dropwort inhibits inflammasome activation. Phytomedicine 24, 77–86. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2016.11.019

Ashikari, M., Wu, J. Z., Yano, M., Sasaki, T., Yoshimura, A. (1999). Rice gibberellin-insensitive dwarf mutant gene dwarf 1 encodes the alpha-subunit of GTP-binding protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. United States America 96, 10284–10289. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.18.10284

Cai, T., Meng, X., Liu, X., Liu, T., Wang, H., Jia, Z., et al. (2018). Exogenous hormonal application regulates the occurrence of wheat tillers by changing endogenous hormones. Front. Plant Sci. 9, 1886. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.01886

Cai, T., Xu, H. C., Peng, D. L., Yin, Y. P., Yang, W. B., Ni, Y. L., et al. (2014). Exogenous hormonal application improves grain yield of wheat by optimizing tiller productivity. Field Crops Res. 155, 172–183. doi: 10.1016/j.fcr.2013.09.008

Cao, K., Wang, B., Fang, W., Zhu, G., Chen, C., Wang, X., et al. (2022). Combined nature and human selections reshaped peach fruit metabolome. Genome Biol. 23, 146. doi: 10.1186/s13059-022-02719-6

Chen, C., Chen, H., Zhang, Y., Thomas, H. R., Frank, M. H., He, Y., et al. (2020). TBtools: an integrative toolkit developed for interactive analyses of big biological data. Mol. Plant 13, 1194–1202. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2020.06.009

Claeys, H., De Bodt, S., Inze, D. (2014). Gibberellins and DELLAs: central nodes in growth regulatory networks. Trends Plant Sci. 19, 231–239. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2013.10.001

Daviere, J. M., Achard, P. (2013). Gibberellin signaling in plants. Development 140, 1147–1151. doi: 10.1242/dev.087650

Eriksson, M. E., Israelsson, M., Olsson, O., Moritz, T. (2000). Increased gibberellin biosynthesis in transgenic trees promotes growth, biomass production and xylem fiber length. Nat. Biotechnol. 18, 784–788. doi: 10.1038/77355

Feng, K., Kan, X. Y., Li, R., Yan, Y. J., Zhao, S. P., Wu, P., et al. (2022). Integrative analysis of long- and short-read transcriptomes identify the regulation of terpenoids biosynthesis under shading cultivation in oenanthe javanica. Front. Genet. 13, 813216. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2022.813216

Feng, K., Xu, Z. S., Que, F., Liu, J. X., Wang, F., Xiong, A. S. (2018). An R2R3-MYB transcription factor, OjMYB1, functions in anthocyanin biosynthesis in oenanthe javanica. Planta 247, 301–315. doi: 10.1007/s00425-017-2783-8

Finn, R. D., Bateman, A., Clements, J., Coggill, P., Eberhardt, R. Y., Eddy, S. R., et al. (2014). Pfam: the protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, D222–D230. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1223

Gallego-Giraldo, L., Ubeda-Tomas, S., Gisbert, C., Garcia-Martinez, J. L., Moritz, T., Lopez-Diaz, I. (2008). Gibberellin homeostasis in tobacco is regulated by gibberellin metabolism genes with different gibberellin sensitivity. Plant Cell Physiol. 49, 679–690. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcn042

Gao, S., Chu, C. (2020). Gibberellin metabolism and signaling: targets for improving agronomic performance of crops. Plant Cell Physiol. 61, 1902–1911. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcaa104

He, Y., Zhao, J., Yang, B., Sun, S., Peng, L., Wang, Z. (2020). Indole-3-acetate beta-glucosyltransferase OsIAGLU regulates seed vigour through mediating crosstalk between auxin and abscisic acid in rice. Plant Biotechnol. J. 18, 1933–1945. doi: 10.1111/pbi.13353

Hedden, P. (2020). The current status of research on gibberellin biosynthesis. Plant Cell Physiol. 61, 1832–1849. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcaa092

Huang, D., Wang, S., Zhang, B., Shang-Guan, K., Shi, Y., Zhang, D., et al. (2015). A gibberellin-mediated DELLA-NAC signaling cascade regulates cellulose synthesis in rice. Plant Cell 27, 1681–1696. doi: 10.1105/tpc.15.00015

Kim, D., Langmead, B., Salzberg, S. L. (2015). HISAT: a fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat. Methods 12, 357–360. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3317

Kim, J. K., Shin, E. C., Park, G. G., Kim, Y. J., Shin, D. H. (2016). Root extract of water dropwort, oenanthe javanica (Blume) DC, induces protein and gene expression of phase I carcinogen-metabolizing enzymes in HepG2 cells. Springerplus 5, 413. doi: 10.1186/s40064-016-2078-8

Kumar, S., Huang, X., Ji, Q., Qayyum, A., Zhou, K., Ke, W., et al. (2022). Influence of blanching on the gene expression profile of phenylpropanoid, flavonoid and vitamin biosynthesis, and their accumulation in oenanthe javanica. Antioxidants 11, 470. doi: 10.3390/antiox11030470

Kumar, S., Huang, X., Li, G., Ji, Q., Zhou, K., Zhu, G., et al. (2021). Comparative transcriptomic analysis provides novel insights into the blanched stem of oenanthe javanica. Plants 10, 2484. doi: 10.3390/plants10112484

Kumar, S., Stecher, G., Tamura, K. (2016). MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. And Evol. 33, 1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054

Lescot, M., Dehais, P., Thijs, G., Marchal, K., Moreau, Y., Van De Peer, Y., et al. (2002). PlantCARE, a database of plant cis-acting regulatory elements and a portal to tools for in silico analysis of promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 30, 325–327. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.325

Li, M., Haixia, Y., Kang, M., An, P., Wu, X., Dang, H., et al. (2021). The arachidonic acid metabolism mechanism based on UPLC-MS/MS metabolomics in recurrent spontaneous abortion rats. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 12, 652807. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2021.652807

Li, W. F., Ma, Z. H., Guo, Z. G., Zuo, C. W., Chu, M. Y., Mao, J., et al. (2023). Insights on the stem elongation of spur-type bud sport mutant of 'Red delicious' apple. Planta 257, 48. doi: 10.1007/s00425-023-04086-3

Li, L., Wang, J. Q., Chen, J. J., Wang, Z. H., Qaseem, M. F., Li, H. L., et al. (2022). Physiological and transcriptomic responses of growth in neolamarckia cadamba stimulated by exogenous gibberellins. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 11842. doi: 10.3390/ijms231911842

Liu, J. X., Jiang, Q., Tao, J. P., Feng, K., Li, T., Duan, A. Q., et al. (2021). Integrative genome, transcriptome, microRNA, and degradome analysis of water dropwort (Oenanthe javanica) in response to water stress. Hortic. Res. 8, 262. doi: 10.1038/s41438-021-00707-8

Liu, J.-X., Liu, H., Tao, J.-P., Tan, G.-F., Dai, Y., Yang, L.-L., et al. (2023). High-quality genome sequence reveals a young polyploidization and provides insights into cellulose and lignin biosynthesis in water dropwort (Oenanthe sinensis). Ind. Crops Products 193, 116203. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2022.116203

Lu, C. L., Li, X. F. (2019). A review of oenanthe javanica (Blume) DC. as traditional medicinal plant and its therapeutic potential. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2019, 6495819. doi: 10.1155/2019/6495819

Moon, S. C., Park, S. C., Yeo, E. J., Kwak, C. S. (2009). Water dropwort (Ostericum sieboldii) and sedum (Sedum sarmentosum) delay H(2)O(2)-induced senescence in human diploid fibroblasts. J. Med. Food 12, 485–492. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2008.1111

Munekata, N., Tsuyama, T., Kamei, I., Kijidani, Y., Takabe, K. (2022). Deposition patterns of feruloylarabinoxylan during cell wall formation in moso bamboo. Planta 256, 59. doi: 10.1007/s00425-022-03970-8

Ohtaka, K., Yoshida, A., Kakei, Y., Fukui, K., Kojima, M., Takebayashi, Y., et al. (2020). Difference between day and night temperatures affects stem elongation in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) seedlings via regulation of gibberellin and auxin synthesis. Front. Plant Sci. 11. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.577235

Park, J. H., Cho, J. H., Kim, I. H., Ahn, J. H., Lee, J. C., Chen, B. H., et al. (2015). Oenanthe javanica extract protects against experimentally induced ischemic neuronal damage via its antioxidant effects. Chin. Med. J. 128, 2932–2937. doi: 10.4103/0366-6999.168063

Pearce, S., Vanzetti, L. S., Dubcovsky, J. (2013). Exogenous gibberellins induce wheat spike development under short days only in the presence of VERNALIZATION1. Plant Physiol. 163, 1433–1445. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.225854

Petrova, A., Sibgatullina, G., Gorshkova, T., Kozlova, L. (2022). Dynamics of cell wall polysaccharides during the elongation growth of rye primary roots. Planta 255, 108. doi: 10.1007/s00425-022-03887-2

Que, F., Khadr, A., Wang, G. L., Li, T., Wang, Y. H., Xu, Z. S., et al. (2018). Exogenous brassinosteroids altered cell length, gibberellin content, and cellulose deposition in promoting carrot petiole elongation. Plant Sci. 277, 110–120. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2018.10.010

Rhee, S. Y., Beavis, W., Berardini, T. Z., Chen, G., Dixon, D., Doyle, A., et al. (2003). The arabidopsis information resource (TAIR): a model organism database providing a centralized, curated gateway to arabidopsis biology, research materials and community. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 224–228. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg076

Richmond, T. A., Somerville, C. R. (2000). The cellulose synthase superfamily. Plant Physiol. 124, 495–498. doi: 10.1104/pp.124.2.495

Sakamoto, T., Miura, K., Itoh, H., Tatsumi, T., Ueguchi-Tanaka, M., Ishiyama, K., et al. (2004). An overview of gibberellin metabolism enzyme genes and their related mutants in rice. Plant Physiol. 134, 1642–1653. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.033696

Sakata, T., Oda, S., Tsunaga, Y., Shomura, H., Kawagishi-Kobayashi, M., Aya, K., et al. (2014). Reduction of gibberellin by low temperature disrupts pollen development in rice. Plant Physiol. 164, 2011–2019. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.234401

Schindelin, J., Rueden, C. T., Hiner, M. C., Eliceiri, K. W. (2015). The ImageJ ecosystem: an open platform for biomedical image analysis. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 82, 518–529. doi: 10.1002/mrd.22489

Seo, S., Seo, K., Ki, S. H., Shin, S. M. (2016). Isorhamnetin inhibits reactive oxygen species-dependent hypoxia inducible factor (HIF)1 alpha a accumulation. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 39, 1830–1838. doi: 10.1248/bpb.b16-00414

Somerville, C. (2006). Cellulose synthesis in higher plants. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 22, 53–78. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.22.022206.160206

Spielmeyer, W., Ellis, M. H., Chandler, P. M. (2002). Semidwarf (sd-1), "green revolution" rice, contains a defective gibberellin 20-oxidase gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 9043–9048. doi: 10.1073/pnas.132266399

Sponsel, V. M. (2016). “Signal achievements in gibberellin research: the second half-century,” in Annual plant reviews, (John Wiley & Sons Ltd.) 1–36. doi: 10.1002/9781119210436.ch1

Trapnell, C., Williams, B. A., Pertea, G., Mortazavi, A., Kwan, G., Van Baren, M. J., et al. (2010). Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat. Biotechnol. 28, 511–515. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1621

Wei, R. R., Ma, Q. G. (2021). Flavonolignan 2, 3-dehydroderivatives from oenanthe javanica and their anti inflammatory activities. Z. Fur Naturforschung Section C-a J. Biosci. 76, 459–465. doi: 10.1515/znc-2021-0001

Wuddineh, W. A., Mazarei, M., Zhang, J. Y., Poovaiah, C. R., Mann, D. G. J., Ziebell, A., et al. (2015). Identification and overexpression of gibberellin 2-oxidase (GA2ox) in switchgrass (Panicum virgatum l.) for improved plant architecture and reduced biomass recalcitrance. Plant Biotechnol. J. 13, 636–647. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12287

Yamaguchi, S. (2008). Gibberellin metabolism and its regulation. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 59, 225–251. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.59.032607.092804

Yang, X. B., Huang, Z. M., Cao, W. B., Zheng, M., Chen, H. Y., Zhang, J. Z. (2000). Antidiabetic effect of oenanthe javanica flavone. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 21, 239–242. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2005.00055.x

Yang, S. A., Jung, Y. S., Lee, S. J., Park, S. C., Kim, M. J., Lee, E. J., et al. (2014). Hepatoprotective effects of fermented field water-dropwort (Oenanthe javanica) extract and its major constituents. Food Chem. Toxicol. 67, 154–160. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2014.02.010

Zhang, X., Zhang, L., Zhang, Q., Xu, J., Liu, W., Dong, W. (2017). Comparative transcriptome profiling and morphology provide insights into endocarp cleaving of apricot cultivar (Prunus armeniaca l.). BMC Plant Biol. 17, 72. doi: 10.1186/s12870-017-1023-5

Keywords: water dropwort, metabolites, cellulose synthase, transcription, gene

Citation: Feng K, Li X, Yan Y, Liu R, Li Z, Sun N, Yang Z, Zhao S, Wu P and Li L (2023) Integrated morphological, metabolome, and transcriptome analyses revealed the mechanism of exogenous gibberellin promoting petiole elongation in Oenanthe javanica. Front. Plant Sci. 14:1225635. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2023.1225635

Received: 19 May 2023; Accepted: 27 June 2023;

Published: 17 July 2023.

Edited by:

Yi-Hong Wang, University of Louisiana at Lafayette, United StatesReviewed by:

Shenghao Liu, Ministry of Natural Resources, ChinaYaqiong Wu, Jiangsu Province and Chinese Academy of Sciences, China

Copyright © 2023 Feng, Li, Yan, Liu, Li, Sun, Yang, Zhao, Wu and Li. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Liangjun Li, bGpsaUB5enUuZWR1LmNu

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Kai Feng1†

Kai Feng1† Liangjun Li

Liangjun Li