94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Plant Sci., 25 April 2023

Sec. Plant Bioinformatics

Volume 14 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2023.1174972

This article is part of the Research TopicHighly Contiguous Plant Genome Assembly and Transcriptional RegulationView all 11 articles

Wei-Cheng Huang1,2,3†

Wei-Cheng Huang1,2,3† Borong Liao1†

Borong Liao1† Hui Liu2,3

Hui Liu2,3 Yi-Ye Liang2,3

Yi-Ye Liang2,3 Xue-Yan Chen2,3

Xue-Yan Chen2,3 Baosheng Wang2,3

Baosheng Wang2,3 Hanhan Xia1*

Hanhan Xia1*Fagaceae species dominate forests and shrublands throughout the Northern Hemisphere, and have been used as models to investigate the processes and mechanisms of adaptation and speciation. Compared with the well-studied genus Quercus, genomic data is limited for the tropical-subtropical genus Castanopsis. Castanopsis hystrix is an ecologically and economically valuable species with a wide distribution in the evergreen broad-leaved forests of tropical-subtropical Asia. Here, we present a high-quality chromosome-scale reference genome of C. hystrix, obtained using a combination of Illumina and PacBio HiFi reads with Hi-C technology. The assembled genome size is 882.6 Mb with a contig N50 of 40.9 Mb and a BUSCO estimate of 99.5%, which are higher than those of recently published Fagaceae species. Genome annotation identified 37,750 protein-coding genes, of which 97.91% were functionally annotated. Repeat sequences constituted 50.95% of the genome and LTRs were the most abundant repetitive elements. Comparative genomic analysis revealed high genome synteny between C. hystrix and other Fagaceae species, despite the long divergence time between them. Considerable gene family expansion and contraction were detected in Castanopsis species. These expanded genes were involved in multiple important biological processes and molecular functions, which may have contributed to the adaptation of the genus to a tropical-subtropical climate. In summary, the genome assembly of C. hystrix provides important genomic resources for Fagaceae genomic research communities, and improves understanding of the adaptation and evolution of forest trees.

The Fagaceae family includes nine genera and roughly 900 species, which dominate forests and shrublands throughout the Northern Hemisphere (Oh and Manos, 2008; Petit et al., 2013). The three largest genera, Quercus (about 450 species), Lithocarpus (about 300 species), and Castanopsis (about 120 species) rapidly diverged after the Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary (K-Pg) (Zhou et al., 2022b) and currently occupy various habitats (Petit et al., 2013; Cannon et al., 2018). Quercus species are the dominant tree species of temperate forests in Eurasia and North American, while Castanopsis and Lithocarpus are mainly found in the tropical-subtropical evergreen forests of East and Southeast Asia (Petit et al., 2013; Cannon et al., 2018). Fagaceae species have been widely used as models of ecological and evolutionary genomic studies for the investigation of the processes and mechanisms of adaptation and speciation (Petit et al., 2013; Cavender-Bares, 2019; Kremer and Hipp, 2020). To date, more than 10 genomes of Quercus species have been assembled (Table 1), and the genomes of a dozen to one hundred individual oaks, such as those of Q. acutissima (Fu et al., 2022; Yuan et al., 2023), Q. dentata (Zhou et al., 2022a), Q. petraea (Leroy et al., 2020) and Q. variabilis (Liang et al., 2022) have been re-sequenced. By contrast, there is only a limited amount of genomic data available for the genus Castanopsis, and only one genome assembly (C. tibetana) is available for this genus (Sun et al., 2022). Molecular markers have been used to investigate the genetic diversity and evolutionary history of Castanopsis species (Shi et al., 2011; Li et al., 2014; Sun et al., 2014; Sun et al., 2016; Jiang et al., 2020; Li et al., 2022). However, our knowledge of the evolution of those species is incomplete or possibly biased due to a lack of sufficient genomic data. The availability of whole genome-wide data would provide an unprecedented opportunity for acquiring a deeper understanding of the adaptation and evolution of the genus Castanopsis, and would expand Fagaceae genome resources for comparative analysis.

Castanopsis hystrix (2n=2x=24) is one of the most important and dominant species of the tropical-subtropical evergreen forests of Asia (Li, 1996). In China, C. hystrix is naturally distributed in mixed and secondary forests, and its distribution extends from Nanling Mountain to Hainan Island and from Taiwan to south Tibet (Huang et al., 1999). C. hystrix is an ecologically and economically valuable species, and its forests play critical roles in water and soil conservation, disaster prevention, biodiversity, and the global carbon budget (Huang et al., 2015; You et al., 2018; Liang et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2019a). C. hystrix is also a source of well-textured heartwood, which is widely used in furniture, construction, and shipbuilding, and it also produces seeds that can be used to extract tanning agents and starch (Chen et al., 1993; Chang et al., 1995). Due to the overexploitation of natural forests, the once widespread C. hystrix populations have been greatly diminished and fragmented (Zhao et al., 2020). High-quality genomic data are essential for assessing the patterns of genetic diversity, tracking the evolutionary history, and developing effective and efficient conservation strategies for this plant species. To date, only plastid and nuclear SSR markers have been used to investigate differences in the genetic diversity and divergence of C. hystrix (Li et al., 2007; Li et al., 2022); however, information on its nuclear genome is still unavailable.

In this study, we assembled and annotated the first chromosome-scale high-quality genome of C. hystrix by integrating PacBio HiFi long-reads, Illumina short-reads, RNAseq, and Hi-C sequencing data. We performed comparative genomic analysis to explore the evolution of genes, gene families, and genomes of C. hystrix and related Fagaceae species. Our study provides new insights into the genome evolution of Fagaceae tree species and provides essential genomic resources for germplasm conservation and genetic improvement of C. hystrix.

Fresh leaves were collected from an adult C. hystrix tree growing in Guangdong Fenghuangshan Forest Park (23.22° N, 113.39° E) and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen until further use. Total genomic DNA was isolated from leave tissues using a DNeasy Plant MiniKit (Qiagen, Germany). The DNA quality and concentration were assessed by agarose gel electrophoresis and the Qubit Fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). To obtain whole genome sequencing data, three DNA libraries were constructed and sequenced. First, an Illumina library with insert size of ~350 bp was sequenced on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform with 150 bp paired-end reads. Second, a 20 kb HiFi library was prepared using the SMRTbell Express Template Preparation kit 2.0 (Pacific Biosciences, USA), and then sequenced on the Pacbio Sequel II platform to produce long-reads. Finally, a Hi-C sequencing library was constructed and sequenced on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform (paired-end 150 bp).

Leaves at three different development stages (bud, immature, and mature) were collected from the same tree used for genome sequencing. Total RNA was extracted from leave samples using an RNAprep Pure Plus Kit (Tiangen, China), and the quality of RNA was evaluated using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) and an Agilent 5400 (Agilent Technologies, USA). Total RNAs isolated from different leave tissues were mixed in equal amounts. A synthesized complementary DNA (cDNA) library was sequenced on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform (paired-end 150 bp).

To predict genomic characteristics, k-mer analysis was performed based on Illumina paired-end reads. The 17 bp K-mers were counted using Jellyfish v2.2.7 (Marcais and Kingsford, 2011), and genome size, heterozygosity, and repetitive element content were predicted based on the k-mer count distribution using GenomeScope v2.0 (Vurture et al., 2017).

The de novo assembly of C. hystrix genome was conducted in three steps by integrating Illumina short-reads, PacBio HiFi long-reads, and Hi-C sequencing data. First, the PacBio HiFi reads were error-corrected using NextDenovo v2.4.0 (https://github.com/Nextomics/NextDenovo), and were then initially assembled using Hifiasm v0.15.4 (Cheng et al., 2022). Second, the draft assembly was polished using NextPolish v1.3.1 (Hu et al., 2020), and redundant contigs were filtered using Redundans pipeline (Pryszcz and Gabaldón, 2016). Finally, contigs were linked to 12 pseudo-chromosomes of C. hystrix using ALLHiC (Zhang et al., 2019b) and Juicebox (Durand et al., 2016) based on Hi-C data. The quality of the genome assembly was evaluated using BUSCO (Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs) (Seppey et al., 2019).

The repeat regions, protein-coding genes, and non-coding RNA (ncRNA) were annotated in the C. hystrix genome assembly. Tandem repeats were identified using Tandem Repeats Finder v4.09 (Price et al., 2005), and dispersed repeats were identified by integrating de novo and homology-based methods. Briefly, de novo prediction was performed using LTR_FINDER v1.0.6 (Xu and Wang, 2007), LTR_retriever v2.9.0 (Ou and Jiang, 2018), RepeatScout v1.0.5 (Price et al., 2005), and RepeatModeler v2.0.1 (Flynn et al., 2020). The homology-based approach was conducted using Repeatmasker v4.1.0 (Chen, 2004). The C. hystrix assembly was searched against the RepBase library (Jurka et al., 2005) to identify sequences that are similar to known repetitive elements.

To annotate protein-coding genes, we conducted de novo, homology-based and RNA-Seq-assisted predictions on the repeat-masked C. hystrix genome. For de novo gene annotation, coding regions of genes were predicted using Augustus v3.2.3 (Stanke et al., 2006), Geneid v1.4 (Blanco et al., 2007), Genescan v1.0 (Burge and Karlin, 1997), GlimmerHMM v3.04 (Majoros et al., 2004), and SNAP (Aylor et al., 2006). For homology-based prediction, protein sequences of Castanea mollissima (Wang et al., 2020), Castanopsis tibetana (Sun et al., 2022), Fagus sylvatica (Mishra et al., 2018), Quercus lobata (Sork et al., 2016), Quercus robur (Plomion et al., 2018), and Quercus suber (Ramos et al., 2018) were downloaded from Genbank and aligned with the C. hystrix genome using TblastN v2.2.26 (Altschul et al., 1990). By comparing the homologous genome sequences to the matched proteins, gene models were constructed using GeneWise v2.4.1 (Birney et al., 2004). For RNA-Seq-based auxiliary prediction, a C. hystrix transcriptome was assembled using Trinity v2.1.1 (Grabherr et al., 2011) and aligned to the C. hystrix genome assembly using Hisat v2.0.4 (Kim et al., 2015). After that, gene models were predicted using PASA v2.0.2 (Keilwagen et al., 2016). Gene models predicted by the three methods were integrated using EvidenceModeler v1.1.1 (Haas et al., 2008), resulting in a non-redundant gene set. The ncRNAs, including rRNAs, micro RNAs (miRNAs), and small nuclear RNAs (snRNAs) were identified by searching the genome assembly against the Rfam database (Griffiths-Jones et al., 2003) with default parameters using Infernal v1.1 (Nawrocki and Eddy, 2013). tRNAs were predicted using the program tRNAscan-se v2.0 (Chan et al., 2021).

To infer gene functions, protein sequences were compared with those in Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) (Kanehisa and Goto, 2000), non-redundant (NR), Gene Ontology (GO) (Ashburner et al., 2000), SwissProt (Boeckmann et al., 2003), InterPro (Hunter et al., 2009), and protein family (Pfam) (Finn et al., 2014) databases using Blastp (E-value cutoff of 1e-5). The motifs and domains were characterized using InterProScan v5.31 (Zdobnov and Apweiler, 2001) by searching against public databases, including ProDom, PRINTS, Pfam, SMRT, PANTHER, and PROSITE.

To track the gene family evolution, we analyzed the protein sequences of C. hystrix generated in this study together with those of 10 other species representing major lineages of Fagaceae and eudicots. Proteins of these species were downloaded from public databases. These species included C. tibetana (https://db.cngb.org; Accession number: CNA0019678), C. mollissima (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn; Accession number: GWHANWH00000000), and Oryza sativa (https://phytozome-next.jgi.doe.gov/info/Osativa_v7_0). Other seven species were downloaded from National Center for Biotechnology Information (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), including Fagus sylvatica (GCA_907173295.1), Juglans regia (GCF_001411555.2), Malus domestica (GCA_002114115.1), Prunus persica (GCA_000346465.2), Populus trichocarpa (GCA_000002775.5), Quercus robur (GCA_932294415.1), Vitis vinifera (GCA_000003745.3). We identified orthologous genes using OrthoFinder v2.5.4 (Emms and Kelly, 2019), and then aligned gene coding regions using the package ParaAT v2.0 (Zhang et al., 2012). Single gene alignments were concatenated using seqkit v1.3 (Shen et al., 2016), and poorly aligned regions were excluded using Trimal v1.4 (Capella-Gutierrez et al., 2009). Then, a maximum likelihood (ML) tree was constructed based on the alignment of orthologous genes using IQ-TREE v2.1.2 (Nguyen et al., 2015), and dated using MCMCTree in the PAML v4.9j package (Yang, 2007). Two fossil calibrations were used to constrain the age of nodes. The first split within the Fagaceae family (genus Fagus vs. the rest of the genera) was constrained to 82–81 million years ago (Mya) (Grímsson et al., 2016), and the divergence time between genera Castanopsis and Castanea was restricted to 52.2 Mya (Wilf et al., 2019). Based on the dated phylogenetic tree, the expansion and contraction of gene families were inferred using CAFÉ v4.2.1 (De Bie et al., 2006).

To investigate the syntenic relationship between C. hystrix and relative species, proteins of C. mollissima (Wang et al., 2020) and C. tibetana (Sun et al., 2022) were downloaded from Genbank and compared with the genome of C. hystrix using Blastp (E-value cutoff of 1e-5). Collinear blocks were inferred using MCScanX (Wang et al., 2012) and visualized in JCVI v1.2.20 (Tang et al., 2008). The times of whole genome duplication (WGD) events were inferred from the synonymous substitution rates (Ks) between paralogous and orthologous gene pairs. The Ks of gene pairs was calculated using the Nei-Gojobori algorithm as implemented in MCScanX.

To investigate the evolution of LTRs in C. hystrix and relative species, we identified LTRs in four Fagaceae species (C. mollissima, C. tibetana, Q. robur, and F. sylvatica) following the same procedure used for C. hystrix (see above). For full-length LTRs, the reverse transcriptase (RT) domains were identified using TEsorter v1.4.5 (Zhang et al., 2022), and were then aligned using MAFFT v7.475 (Katoh et al., 2002) with default parameters. The phylogenetic trees of LTRs were constructed based on the alignment of RT domains using FastTree v2.1.10 (Price et al., 2009). To estimate the insertion times (T) of full-length LTRs, the Kimura two-parameter distance (K) of each LTR-RT pair was calculated and converted to the insertion time using the formula T = K/2μ, where the substitution rate (μ) was estimated using the baseml program in the PAML package.

Hard and well-textured heartwood are typical features of C. hystrix trees (Watanabe et al., 2014). Cell wall and lignin metabolic pathway genes are essential for wood formation. The cellulose synthase (CesA) gene family is involved in primary cell wall formation and cellulose synthase is considered the most important enzyme in the synthesis of cellulose microfibrils in plant cells (Kumar and Turner, 2015; Wang et al., 2022b). Hence, we conducted genome-wide characterization of the CesA family in C. hystrix and three relative Fagaceae species (C. mollissima, C. tibetana and Q. robur). The CesA genes in each species were identified using two methods. First, CesA protein sequences of A. thaliana (Persson et al., 2007) and O. sativa (Hazen et al., 2002) were blasted against the genomes of C. hystrix, C. mollissima, C. tibetana, and Q. robur, and homologous genes with an E-value cutoff of 1e-10 were identified. Second, two DNA-binding domains (PF03552 and PF00535) from Pfam (https://pfam.xfam.org/) were searched against protein sequences of Fagaceae species using HMMER v3.3.2 (Finn et al., 2011). The unions identified by both methods were considered to be common elements. To verify the reliability of the intersected results, we analyzed the completeness of CesA gene domains using Pfam and the conserved domain database (CDD, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/cdd/). Then, the theoretical isoelectric points (PI) and molecular weights of CesA proteins were analyzed on the ExPASy website (https://web.expasy.org/compute_pi/).

For phylogenetic analysis, the amino acid sequences of each CesA member were aligned using MUSCLE v3.8 (Edgar, 2004), and phylogenetic trees were constructed using IQ-TREE with 1000 bootstraps and online visualization using iTOL (https://itol.embl.de/) (Letunic and Bork, 2019). To investigate in detail the classification of protein motifs, Multiple Em for Motif Elicitation (MEME) (http://memesuite.org/) was used to annotate the conserved motifs in these proteins. The maximum number of motifs was set to 10 and the motif width was set 10 to100 in MEME analysis. Blastp and MCScanX were used to identify syntenic blocks and duplication events with default parameters and visualization using TBtools (Chen et al., 2020).

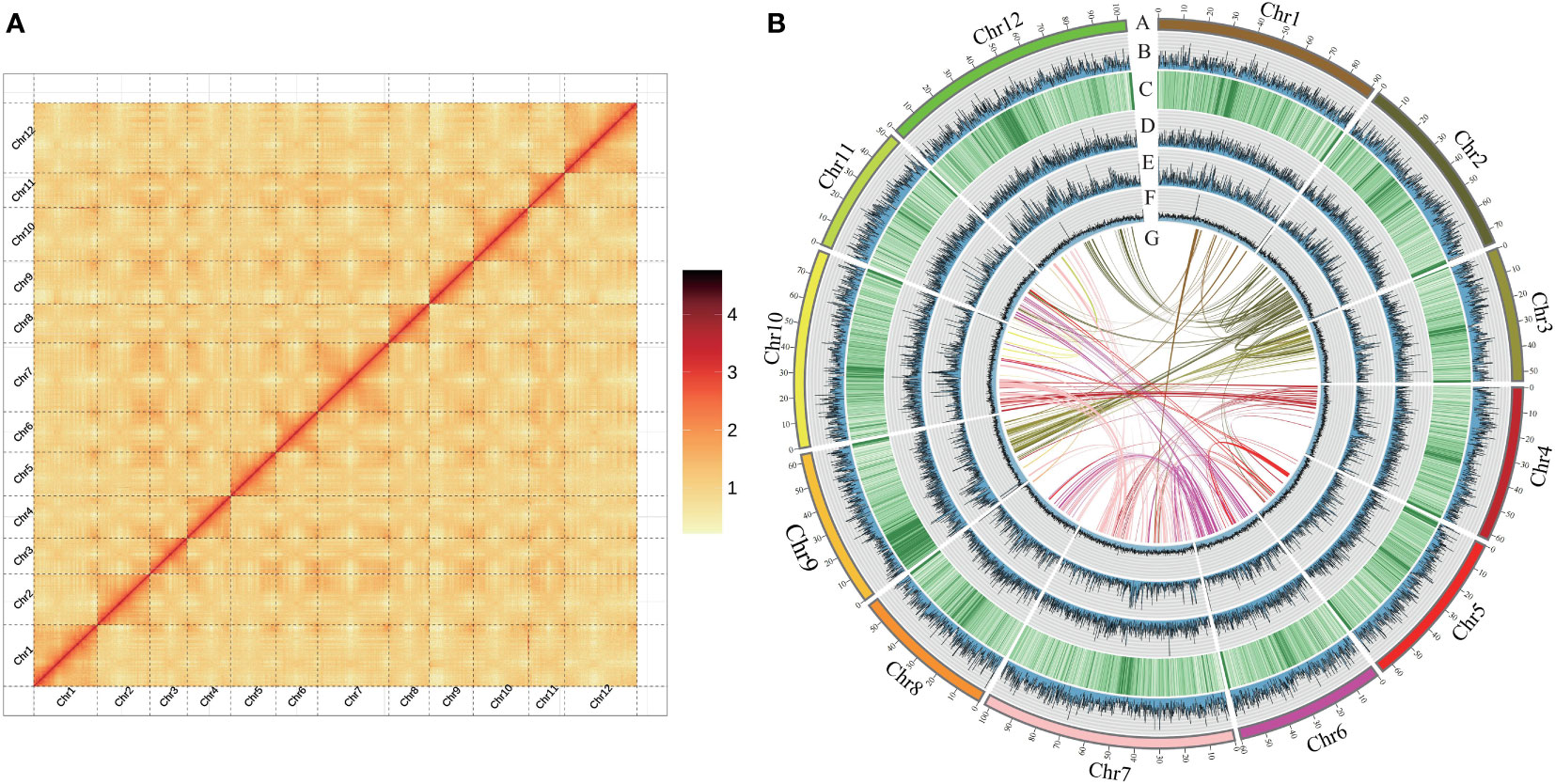

The C. hystrix genome was assembled by using integrated multiple sequencing and assembly technologies. Whole genome sequencing resulted in 52.92 Gb of Illumina short-reads (~59×), 28.14 Gb of PacBio HiFi long-reads (~31×), and 141.12 Gb of Hi-C data (~160×). An initial genome survey using k-mer analysis estimated that the genome size of C. hystrix is about 897.51 Mb and that it has a high level of heterozygosity of 1.26% and a repeat content of 57.38% (Table S1). Illumina short-reads, PacBio HiFi long-reads, and Hi-C sequencing data revealed that the assembled C. hystrix genome is 882.69 Mb, including 211 contigs and 172 scaffolds (Table 1). The contig N50 and scaffold N50 length are 40.95 Mb and 75.63 Mb, respectively. In total, 865.64 Mb (98.07%) of assembled sequences were mounted on 12 pseudo-chromosomes ranging from 51.51 Mb to 103.15 Mb (Figure 1A, Table 1). The heat map of Hi-C interactions shows that the genome assembly is intact and robust (Figure 1B).

Figure 1 Features of Castanopsis hystrix genome. (A) Genome-wide analysis of chromatin interactions in the C hystrix genome based on Hi-C data. (B) The Synteny and distribution of genomic features. (A) The 12 pseudochromosomes; (B) gene density; (C–E) the density of total repeat sequences, Gypsy LTR-RTs, and Copia LTR-RTs; (F) histogram of GC content; (G) intragenomic collinearity. (B–F) were drawn in 100 kb overlapping sliding windows.

The high accuracy and completeness of the C. hystrix genome assembly was supported by three analyses. First, joint analysis of GC content and sequencing depth revealed no obvious deviation in quality across the genome, suggesting the high quality of genome sequencing and assembly (Figures 1, S1). Second, approximately 97.66% of cleaned PacBio HiFi long-reads were successfully mapped to the genome, and more than 99% of the genome assembly had a coverage >10× (Table S2), suggesting that the genome assembly was accurate and complete. Finally, BUSCO analyses revealed that 99.5% of universal single-copy orthologs were present in the genome assembly (Table 1), indicating the high integrity of the genome assembly.

A total of 449.72 Mb (50.95%) of the C. hystrix genome was annotated as repetitive sequences (Tables 1, S3). The most abundant repetitive elements were LTRs (374.50 Mb), followed by tandem repeats (47.64 Mb), long interspersed nuclear elements (LINEs; 18.08 Mb), DNA transposons (12.90 Mb), and short interspersed nuclear elements (SINEs; 16,791 bp) (Table S3).

By integrating de novo, homology-based, and RNA-Seq-assisted predictions, a total of 37,750 protein-coding genes were predicted in the C. hystrix genome (Tables 1, S4). The average lengths of coding sequences (CDSs), exons and introns are 1,067 bp, 244 bp and 1,112 bp, respectively (Table S4). By comparing the predicted gene set with six public databases, 36,962 (97.91%) of the total predicted genes were functionally annotated (Table S5). Non-coding RNA annotation identified 922 miRNAs, 741 tRNAs, 8,971 rRNAs, and 665 snRNAs in C. hystrix (Table S6).

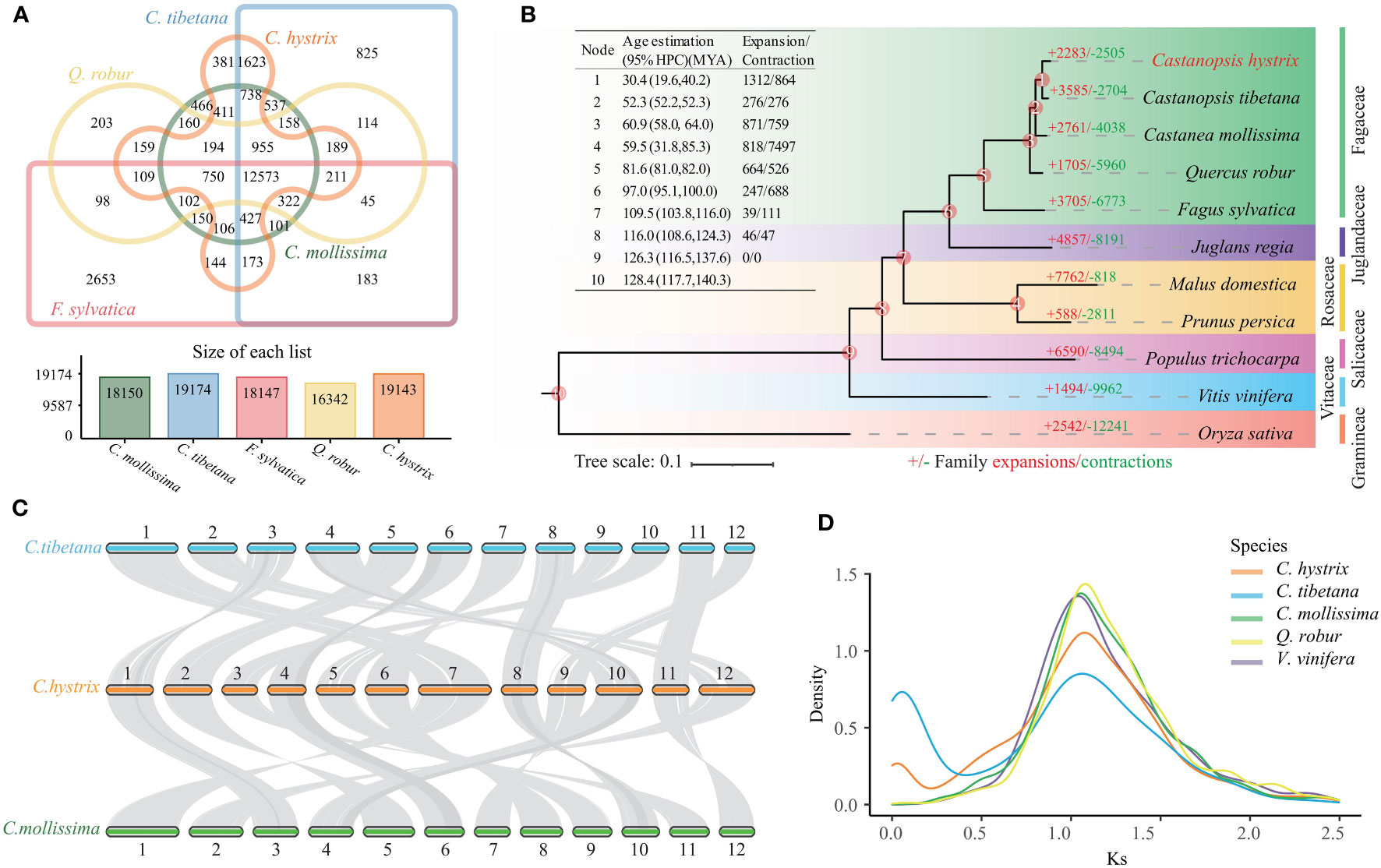

To explore the evolutionary history of the C. hystrix gene family, we clustered 36,448 (96.6%) annotated genes into 19,143 gene families. Among these, 12,573 gene families were shared with those of four other studied Fagaceae species (Figure 2A), and 299 families (1,043 genes) were unique to C. hystrix. Functional enrichment analysis showed that unique genes of C. hystrix were significantly enriched in 10 KEGG pathways and 115 GO terms, including Fatty acid biosynthesis, Porphyrin and chlorophyll metabolism, malate transport, and polynucleotide adenylyltransferase activity (Table S7; Figure S2).

Figure 2 Genomic evolutionary and comparative genomic analyses. (A) Shared and unique gene families in C hystrix, C tibetana, C mollissima, Q. robur, and F sylvatica. (B) Phylogenomic tree and expansion and contraction of gene families among C hystrix and 10 other species. Numbers in red (+) and green (−) show the number of expanded and contracted gene families, respectively. (C) The synteny blocks between C hystrix, C tibetana, and C mollissima. Syntenic blocks were connected by grey lines. (D) The synonymous substitution rates (Ks) distributions of paralogous genes.

A phylogenetic tree constructed using 556 single-copy orthologs among C. hystrix and other 10 angiosperms revealed that two Castanopsis species (C. hystrix and C. tibetana) were grouped together, and these two species are sister to a Castanea species (C. mollissima) (Figure 2B). Calibration of the phylogenetic tree using two Fagaceae fossil records showed that the divergence time between C. hystrix and C. tibetana is 30.4 Mya (95% HPD: 19.6–40.2 Mya) (Figures 2B, S3). The close phylogenetic relationships between Castanopsis and Castanea species were supported by the high genome synteny and colinearity (Figure 2C).

Based on the clustered gene families and dated phylogenetic tree, CAFÉ analyses detected 2283 expanded gene families and 2505 contracted gene families in C. hystrix (Figure 2B; Tables S8). Among these, 202 expanded and 62 contracted gene families were statistically significant (P < 0.01; Table S8). The 202 expanded gene families were enriched in 7 KEGG pathways and 36 GO terms, such as “Arginine and proline metabolism”, “Phenylalanine metabolism”, “Fatty acid degradation”, and “Trehalose biosynthetic process” (Table S9; Figure S2). The 62 contracted gene families were primarily enriched in KEGG pathway processes “Sesquiterpenoid and triterpenoid biosynthesis”, “Plant-pathogen interaction”, and “MAPK signaling” (Table S9). A search of C. hystrix expanded genes families against PlantTFDB (http://planttfdb.gao-lab.org/) revealed that 29 genes were categorized into four transcription factors (TFs) families (FAR1, B3, bHLH, and NAC). Among these, 23 genes belong to the FAR1 family, and the other six genes belong to B3 (one gene), bHLH (two genes), and NAC (three genes) families (Table S10). We also found that 17 and 16 gene families significantly expanded and contracted, respectively, in the most common ancestor of C. hystrix and C. tibetana. Functional enrichment analysis revealed that the 17 expanded gene families were overrepresented in 11 KEGG pathways and 8 GO terms, including “Fatty acid degradation”, “Plant-pathogen interaction” and “RNA-DNA hybrid ribonuclease activity” (Table S9). The 16 contracted gene families were enriched in six KEGG pathways and four GO terms (Table S9).

Comparative genomic analyses were performed to discern the number of WGD events in C. hystrix. A total of 65 syntenic blocks (2,442 collinear genes) with sizes ranging from 11 to 48 gene pairs were detected in C. hystrix, accounting for 6.47% of the total gene set. The number of collinear genes in C. hystrix was close to those of other Fagaceae species (2484–2673 genes; 6.53%–7.71% of the total gene set) but lower than that in V. vinifera (3297 genes; 12.85% of the total gene set) (Table S11). The Ks values of paralogous and orthologous gene pairs showed that all four Fagaceae species and V. vinifera shared a Ks peak of approximately 1.08 units (Figure 2D), most likely representing the triplication event (γ) shared by all eudicots (Murat et al., 2015). Synteny analysis revealed a 1:1 syntenic depth ratio for C. hystrix vs. Fagaceae species and a 2:2 syntenic depth ratio for C. hystrix vs. V. vinifera (Figure S4). These results suggested that no independent WGD events have occurred in C. hystrix and other Fagaceae species.

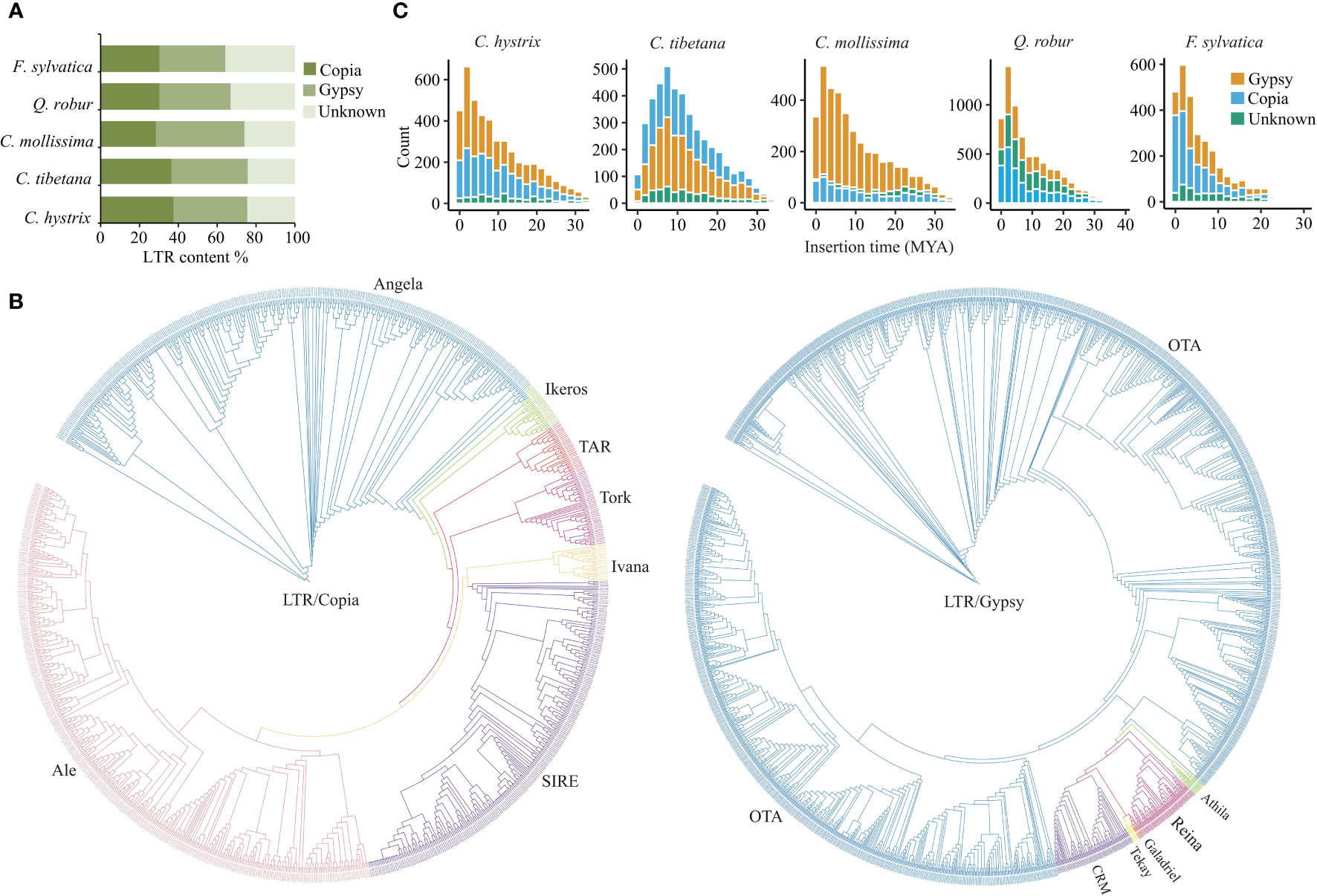

Copia and Gypsy are the two most abundant LTR super families in C. hystrix and three other Fagaceae species. In C. hystrix, Copia- and Gypsy-type LTRs accounted for 37.49% and 38.04% of LTRs, respectively (Figure 3A; Table S12). The content of Copia- and Gypsy-type LTRs was slightly different among Fagaceae species (Figure 3A; Table S12), indicating independent expansion or elimination of repetitive elements. Phylogenetic analyses using RT domains of LTRs revealed that Copia-type elements were clustered into seven major groups, with Ale-type repeats forming the largest group (N = 355) followed by Angela (N = 320), SIRE (N = 235), Tork (N = 46), TAR (N = 29), Ikeros (N = 28), and Ivana (N = 21; Figure 3B). The Gypsy-type elements were grouped into six clades, and the OTA group accounted for 91% (1,658) of Gypsy members (Figure 3B). Full analyses with all Gypsy and Copia elements from the five Fagaceae species showed that the lineages of Copia and Gypsy were grouped according to their respective tribes, indicating different evolutionary relationships among LTR families (Figure S5). To further explore the details of LTR expansion, we estimated the insertion time of full-length LTRs. In C. hystrix, the insertion time peaks of both Copia- and Gypsy-type LTRs were found approximately at 2 Mya, while a more ancient amplification peak was found around 8 Mya in C. tibetana (Figure 3C). In other Fagaceae species, a significant burst of LTRs was detected at 1–3 Mya, but the extent of expansion varied among species and was also different between Copia- and Gypsy-type LTRs (Figure 3C).

Figure 3 The features of LTR expansion in the Fagaceae genomes. (A) Comparison of LTR contents in C hystrix and 4 other species. (B) Neighbor-joining trees of Copia and Gypsy LTRs from C hystrix. (C) Insertion time estimates of full-length LTRs in five Fagaceae species.

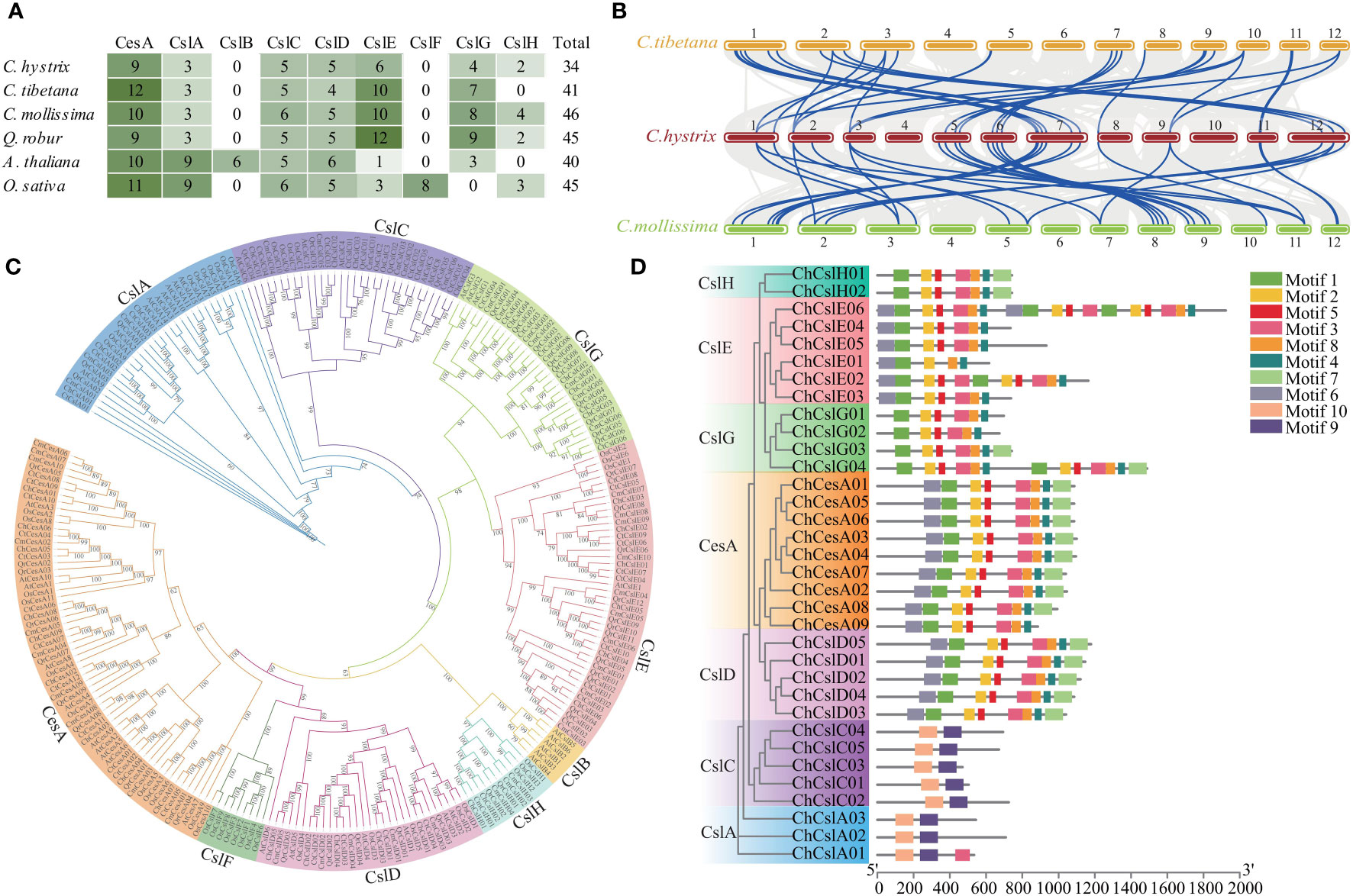

Genome-wide characterization of the CesA family in C. hystrix identified 34 CesA-like genes (Figure 4A; Table S13). Phylogenetic analysis suggested that these genes could be divided into seven subfamilies (CesA, CslA–CslH) (Figure 4C; Table S13). Genes from the same subfamily showed similar protein domains and motif compositions, supporting their phylogenetic relationships (Figures 4D, S6). Similar numbers of CesA-like genes were found in three closely related Fagaceae species (41, 46, and 45 genes in C. tibetana, C. mollissima, and Q. robur, respectively) and two distinct related species, A. thaliana (40 genes) and O. sativa (45 genes) (Figure 4A; Table S14). However, Fagacea species showed different CesA subfamily content to that of A. thaliana and O. sativa (Figure 4A). For example, the number of CslE and CslG genes in Fagaceae species (6–12 and 4–9, respectively) was much higher than in A. thaliana (one and three, respectively) and O. sativa (three and none, respectively) (Figure 4A). Nine CslA genes were identified in A. thaliana and O. sativa, but only three CslA members were found in Fagaceae species (Figure 4A). In addition, the collinearity of CesA-like gene between C. hystrix and other Fagaceae species was clearly higher than those for C. hystrix vs. A. thaliana and O. sativa (Figures 4B, S7). An analysis of the distribution of CesA-like genes across the genome of C. hystrix revealed tandem duplication of 10 CesA genes (Figure S8).

Figure 4 Identification and Evolution of CesA family in Fagaceae. (A) The heatmap shown a comparison of the numbers of CesA genes among four Fagaceae plants, Arabidopsis thaliana, and Oryza sativa. (B) Synteny analysis of CesA genes between C hystrix, C tibetana, and C mollissima. The blue lines highlight the syntenic CesA gene pairs. (C) Phylogenetic tree of CesA gene families in four Fagaceae plants, A thaliana, and O. sativa. (D) Phylogenetic relationships and architecture of the conserved protein motifs in 34 CesA genes from C hystrix.

In this study, we generated a high-quality chromosome-scale assembly of C. hystrix. The assembled genome was approximately 882.6 Mb, of which more than 98% of the sequences were anchored to 12 pseudo-chromosomes ranging from 51.5 to 103.2 Mb in size. The contig N50 of the C. hystrix genome assembly was 40.95 Mb, which is higher than those of recently published Fagaceae species, such as C. tibetana (3.32 Mb) (Sun et al., 2022), C. mollissima (2.83 Mb) (Wang et al., 2020), Castanea crenata (6.36 Mb) (Wang et al., 2022a), Quercus gilva (28.32 Mb) (Zhou et al., 2022c), Q. lobata (1.90 Mb) (Sork et al., 2022), Quercus variabilis (26.04 Mb) (Han et al., 2022), and F. sylvatica (0.14 Mb) (Mishra et al., 2022). Genome assembly integrity, as assessed by BUSCO, reached 99.5% for C. hystrix, surpassing that of previously assembled Fagaceae genomes (90.5%–98.6%; Table 1). The high quality of the genome assembly can be mainly attributed to the successful implementation of new sequencing technologies, a statistical algorithm, and analytical approaches. Although gap-free T2T genomes are available in model species (Naish et al., 2021; Song et al., 2021), de novo genome assembly is still challenging for forest trees because of their large and complex genomes. Our genome assembly of C. hystrix is one of the most high-quality genomes of Fagaceae species ever reported.

Based on comparative genome analysis, we found high genome synteny between C. hystrix and C. tibetana and C. mollissima, although these species diverged more than 30 million years ago (Zhou et al., 2022b). We also found that C. hystrix and other investigated Fagaceae species did not experience WGD after the triplication event (γ) (Murat et al., 2015). These results are consistent with the previous hypothesis that ploidy level and genome structure are conserved among Fagaceae species, which may have facilitated the adaptive introgression between species (Chen et al., 2014; Cannon and Petit, 2020). Transposable elements (TEs) account for large parts of plant genomes, where they play an important role in evolution (Bennetzen and Wang, 2014; Akakpo et al., 2020). The proportion of the repetitive elements in the C. hystrix genome was 50.95%, similar to that reported for other Fagaceae, such as C. tibetana (54.30%) (Sun et al., 2022), C. mollissima (53.24%) (Wang et al., 2020), Q. mongolica (53.75%) (Ai et al., 2022), and Q. variabilis (26.04 Mb) (Han et al., 2022). Evolutionary analyses of LTRs showed that C. hystrix and relative Fagaceae species experienced a recent large-scale LTR burst, but the time and extent of LTR expansion varied between species and between LTR families, which may have influenced the structure and function of genomes and contributed to the adaptation and evolution of Fagaceae species.

Whole genome annotation and analysis revealed considerable gene family expansion and contraction in C. hystrix and relative species. These expanded and contracted gene families were involved in multiple important biological processes and molecular functions, providing valuable information for understanding the genetic basis of adaptation, evolution, and speciation in Fagaceae. For example, 17 gene families expanded in the most recent ancestor of C. tibetana and C. hystrix, and 202 gene families independently expanded in C. hystrix. Functional enrichment analysis suggested that the 17 expanded gene families were highly overrepresented in stress and defense-associated pathways, such as plant–pathogen interaction and Fatty acid degradation (Kindl, 1993; Goepfert and Poirier, 2007; Dodds and Rathjen, 2010; Chhajed et al., 2020). Fatty acid degradation is essential for seed development, seed germination, and post-germinative growth before the establishment of photosynthesis (Kindl, 1993; Goepfert and Poirier, 2007). In addition, expanded gene families in C. hystrix were enriched in the biological processes “Phenylpropanoids”, which influences plant responses to biotic and abiotic stimuli (La Camera et al., 2004; Vogt, 2010), and “Arginine and proline metabolism”, which plays key roles in nitrogen distribution and recycling in plants (Slocum, 2005; Rennenberg et al., 2010). Several expanded genes in C. hystrix are also members of the transcription factor family FAR1, which modulates phyA signaling (Lin et al., 2007) and regulates the balance between growth and defense under shade conditions (Liu et al., 2019). Therefore, the gene family expansions might have facilitated the adaptation of the genus Castanopsis to a tropical-subtropical climate, after they had diverged from their deciduous counterparts in cool-temperate areas. Furthermore, CslE/CslG genes of the CesA family exhibited expansion and tandem duplication in Fagaceae species. CesA genes are involved in the biosynthesis of various polysaccharide polymers, in particular hemicelluloses (Richmond and Somerville, 2000; Lerouxel et al., 2006). A recent study suggested that the expansion of the CesA family might have contributed to the formation of the high-density timbers that are characteristic of Dipterocarpaceae species (Wang et al., 2022b). Thus, we suspect that CesA gene expansion might be related to the development of the high-density woods of Fagaceae species. Taken together, these considerations suggest that gene family expansions might have played critical roles in the genetic, morphological, and physiological innovations of Fagaceae species.

In conclusion, we obtained the first chromosome-scale genome assembly of C. hystrix using a combination of multiple sequencing and assembly approaches. Genome-wide characterization and evolutionary analysis provided novel insights into the genome evolution and key regulatory pathways of wood formation in Fagaceae species. The C. hystrix genome assembly contains both high-quality reference sequences and important functional genes, which expands the genome resources for Fagaceae species and opens the possibility of conducting comparative and functional genomic studies of forest tree species.

The data presented in the study are deposited in the National Genomics Data Center (NGDC) database, BioProject accession number PRJCA015225.

HX designed this study. BW and Y-YL collected samples. W-CH, BL, HL, and X-YC analyzed the data. HX, W-CH, and BL wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 32001244).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2023.1174972/full#supplementary-material

Ai, W., Liu, Y., Mei, M., Zhang, X., Tan, E., Liu, H., et al. (2022). A chromosome-scale genome assembly of the Mongolian oak (Quercus mongolica). Mol. Ecol. Resour. 22, 2396–2410. doi: 10.1111/1755-0998.13616

Akakpo, R., Carpentier, M. C., Ie, H. Y., Panaud, O. (2020). The impact of transposable elements on the structure, evolution and function of the rice genome. New Phytol. 226, 44–49. doi: 10.1111/nph.16356

Altschul, S. F., Gish, W., Miller, W., Myers, E. W., Lipman, D. J. (1990). Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215, 403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2

Ashburner, M., Ball, C. A., Blake, J. A., Botstein, D., Butler, H., Cherry, J. M., et al. (2000). Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. Nat. Genet. 25, 25–29. doi: 10.1038/75556

Aylor, D. L., Price, E. W., Carbone, I. (2006). SNAP: Combine and map modules for multilocus population genetic analysis. Bioinformatics 22, 1399–1401. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl136

Bennetzen, J. L., Wang, H. (2014). The contributions of transposable elements to the structure, function, and evolution of plant genomes. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 65, 505–530. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-050213-035811

Birney, E., Clamp, M., Durbin, R. (2004). GeneWise and genomewise. Genome Res. 14, 988–995. doi: 10.1038/sdata.2018.69

Blanco, E., Parra, G., Guigó, R. (2007). Using geneid to identify genes. Curr. Protoc. Bioinf. 18, 4–3. doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi0403s18

Boeckmann, B., Bairoch, A., Apweiler, R., Blatter, M. C., Estreicher, A., Gasteiger, E., et al. (2003). The SWISS-PROT protein knowledgebase and its supplement TrEMBL in 2003. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 365–370. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg095

Burge, C., Karlin, S. (1997). Prediction of complete gene structures in human genomic DNA. J. Mol. Biol. 268, 78–94. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.0951

Cannon, C. H., Brendel, O., Deng, M., Hipp, A. L., Kremer, A., Kua, C. S., et al. (2018). Gaining a global perspective on fagaceae genomic diversification and adaptation. New Phytol. 218, 894–897. doi: 10.1111/nph.16091

Cannon, C. H., Petit, R. J. (2020). The oak syngameon: more than the sum of its parts. New Phytol. 226, 978–983. doi: 10.1111/nph.16091

Capella-Gutierrez, S., Silla-Martinez, J. M., Gabaldon, T. (2009). TrimAl: A tool for automated alignment trimming in large-scale phylogenetic analyses. Bioinformatics 25, 1972–1973. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp348

Cavender-Bares, J. (2019). Diversification, adaptation, and community assembly of the American oaks (Quercus), a model clade for integrating ecology and evolution. New Phytol. 221, 669–692. doi: 10.1111/nph.15450

Chan, P. P., Lin, B. Y., Mak, A. J., Lowe, T. M.. (2021). tRNAscan-SE 2.0: improved detection and functional classification of transfer RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, 9077–9096. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt509

Chang, C., Lin, M., Lee, S., Liu, K. C. C., Hsu, F. L., Lin, J. Y. (1995). Differential inhibition of reverse transcriptase and cellular DNA polymerase-α activities by lignans isolated from Chinese herbs, Phyllanthus myrtifolius moon, and tannins from Lonicera japonica thunb and Castanopsis hystrix. Antiviral Res. 27, 367–374. doi: 10.1016/0166-3542(95)00020-M

Chen, N. (2004). Using RepeatMasker to identify repetitive elements in genomic sequences. Curr. Protoc. Bioinf. 5, 4–10. doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi0410s05

Chen, S. C., Cannon, C. H., Kua, C. S., Liu, J. J., Galbraith, D. W. (2014). Genome size variation in the fagaceae and its implications for trees. Tree Genet. Genomes 10, 977–988. doi: 10.1007/s11295-014-0736-y

Chen, C., Chen, H., Zhang, Y., Thomas, H. R., Frank, M. H., He, Y., et al. (2020). TBtools: an integrative toolkit developed for interactive analyses of big biological data. Mol. Plant 13, 1194–1202. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2020.06.009

Chen, H., Tanaka, T., Nonaka, G., Fujioka, T., Mihashi, K. (1993). Hydrolysable tannins based on a triterpenoid glycoside core, from Castanopsis hystrix. Phytochemistry 32, 1457–1460. doi: 10.1016/0031-9422(93)85159-O

Cheng, H., Jarvis, E. D., Fedrigo, O., Koepfli, K. P., Urban, L., Gemmell, N., et al. (2022). Haplotype-resolved assembly of diploid genomes without parental data. Nat. Biotechnol. 40, 1332–1335. doi: 10.1038/s41587-022-01261-x

Chhajed, S., Mostafa, I., He, Y., Abou-Hashem, M., El-Domiaty, M., Chen, S. (2020). Glucosinolate biosynthesis and the glucosinolate-myrosinase system in plant defense. Agronomy 10, 1786. doi: 10.3390/agronomy10111786

De Bie, T., Cristianini, N., Demuth, J. P., Hahn, M. W. (2006). CAFE: A computational tool for the study of gene family evolution. Bioinformatics 22, 1269–1271. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl097

Dodds, P. N., Rathjen, J. P. (2010). Plant immunity: towards an integrated view of plant-pathogen interactions. Nat. Rev. Genet. 11, 539–548. doi: 10.1038/nrg2812

Durand, N. C., Robinson, J. T., Shamim, M. S., Machol, I., Mesirov, J. P., Lander, E. S., et al. (2016). Juicebox provides a visualization system for Hi-c contact maps with unlimited zoom. Cell Syst. 3, 99–101. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2015.07.012

Edgar, R. C. (2004). MUSCLE: Multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, 1792–1797. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340

Emms, D. M., Kelly, S. (2019). OrthoFinder: Phylogenetic orthology inference for comparative genomics. Genome Biol. 20, 238. doi: 10.1186/s13059-019-1832-y

Finn, R. D., Bateman, A., Clements, J., Coggill, P., Eberhardt, R. Y., Eddy, S. R., et al. (2014). Pfam: the protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, D222–D230. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1223

Finn, R. D., Clements, J., Eddy, S. R. (2011). HMMER web server: Interactive sequence similarity searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, W29–W37. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr367

Flynn, J. M., Hubley, R., Goubert, C., Rosen, J., Clark, A. G., Feschotte, C., et al. (2020). RepeatModeler2 for automated genomic discovery of transposable element families. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 117, 9451–9457. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1921046117

Fu, R., Zhu, Y., Liu, Y., Feng, Y., Lu, R. S., Li, Y., et al. (2022). Genome-wide analyses of introgression between two sympatric Asian oak species. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 6, 924–935. doi: 10.1038/s41559-022-01754-7

Goepfert, S., Poirier, Y. (2007). β-oxidation in fatty acid degradation and beyond. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 10, 245–251. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2007.04.007

Grabherr, M. G., Haas, B. J., Yassour, M., Levin, J. Z., Thompson, D. A., Amit, I., et al. (2011). Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-seq data without a reference genome. Nat. Biotechnol. 29, 644–652. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1883

Griffiths-Jones, S., Bateman, A., Marshall, M., Khanna, A., Eddy, S. R. (2003). Rfam: an RNA family database. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 439–441. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg006

Grímsson, F., Grimm, G. W., Zetter, R., Denk, T. (2016). Cretaceous And paleogene fagaceae from north America and Greenland: evidence for a late Cretaceous split between fagus and the remaining fagaceae. Acta Palaeobotanica 56, 247–305. doi: 10.1515/acpa-2016-0016

Haas, B. J., Salzberg, S. L., Zhu, W., Pertea, M., Allen, J. E., Orvis, J., et al. (2008). Automated eukaryotic gene structure annotation using EVidenceModeler and the program to assemble spliced alignments. Genome Biol. 9, 1–22. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-1-r7

Han, B., Wang, L., Xian, Y., Xie, X. M., Li, W. Q., Zhao, Y., et al. (2022). A chromosome-level genome assembly of the Chinese cork oak (Quercus variabilis). Front. Plant Sci. 13. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.1001583

Hazen, S. P., Scott-Craig, J. S., Walton, J. D. (2002). Cellulose synthase-like genes of rice. Plant Physiol. 128, 336–340. doi: 10.1104/pp.010875

Hu, J., Fan, J., Sun, Z., Liu, S. (2020). NextPolish: A fast and efficient genome polishing tool for long-read assembly. Bioinformatics 36, 2253–2255. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btz891

Huang, C., Zhang, Y., Bruce, B. (1999). “Fagaceae,” in Flora of China, Eds. Wu, Z. Y., Raven, P. H., Hong, D. Y. (Beijing, China: Science Press and Missouri Botanical Garden Press) 4, 314–400. Available at: http://flora.huh.harvard.edu/china/mss/volume04/FAGACEAE.published.pdf.

Huang, W., Zhou, G., Deng, X., Liu, J., Duan, H., Zhang, D., et al. (2015). Nitrogen and phosphorus productivities of five subtropical tree species in response to elevated CO2 and n addition. Eur. J. For. Res. 134, 845–856. doi: 10.1007/s10342-015-0894-y

Hunter, S., Apweiler, R., Attwood, T. K., Bairoch, A., Bateman, A., Binns, D., et al. (2009). InterPro: the integrative protein signature database. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, D211–D215. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn785

Jiang, K., Xie, H., Liu, T., Liu, C., Huang, S. (2020). Genetic diversity and population structure in Castanopsis fissa revealed by analyses of sequence-related amplified polymorphism (SRAP) markers. Tree Genet. Genomes 16, 52. doi: 10.1007/s11295-020-01442-2

Jurka, J., Kapitonov, V. V., Pavlicek, A., Klonowski, P., Kohany, O., Walichiewicz, J. (2005). Repbase update, a database of eukaryotic repetitive elements. Cytogenetic Genome Res. 110, 462–467. doi: 10.1159/000084979

Kanehisa, M., Goto, S. (2000). KEGG: kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 27–30. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.27

Katoh, K., Misawa, K., Kuma, K., Miyata, T. (2002). MAFFT: a novel method for rapid multiple sequence alignment based on fast Fourier transform. Nucleic Acids Res. 30, 3059–3066. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf436

Keilwagen, J., Wenk, M., Erickson, J. L., Schattat, M. H., Grau, J., Hartung, F. (2016). Using intron position conservation for homology-based gene prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, e89–e89. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw092

Kim, D., Langmead, B., Salzberg, S. L. (2015). HISAT: A fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat. Methods 12, 357–360. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3317

Kindl, H. (1993). Fatty acid degradation in plant peroxisomes: function and biosynthesis of the enzymes involved. Biochimie 75, 225–230. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(93)90080-C

Kremer, A., Hipp, A. L. (2020). Oaks: an evolutionary success story. New Phytol. 226, 987–1011. doi: 10.1111/nph.16274

Kumar, M., Turner, S. (2015). Plant cellulose synthesis: CESA proteins crossing kingdoms. Phytochemistry 112, 91–99. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2014.07.009

La Camera, S., Gouzerh, G., Dhondt, S., Hoffmann, L., Fritig, B., Legrand, M., et al. (2004). Metabolic reprogramming in plant innate immunity: the contributions of phenylpropanoid and oxylipin pathways. Immunol. Rev. 198, 267–284. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.0129.x

Lerouxel, O., Cavalier, D. M., Liepman, A. H., Keegstra, K. (2006). Biosynthesis of plant cell wall polysaccharides - a complex process. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 9, 621–630. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2006.09.009

Leroy, T., Louvet, J. M., Lalanne, C., Le Provost, G., Labadie, K., Aury, J. M., et al. (2020). Adaptive introgression as a driver of local adaptation to climate in European white oaks. New Phytol. 226, 1171–1182. doi: 10.1111/nph.16095

Letunic, I., Bork, P. (2019). Interactive tree of life (iTOL) v4: recent updates and new developments. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, W256–W259. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz239

Li, J. Q. (1996). The origin and distribution of the family fageceae. Acta Phytotaxon. Sin. 34, 376–396. Available at: https://www.jse.ac.cn/EN/Y1996/V34/I4/376.

Li, J., Ge, X., Cao, H., Ye, W. H. (2007). Chloroplast DNA diversity in Castanopsis hystrix populations in south China. For. Ecol. Manage. 243, 94–101. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2007.02.012

Li, C., Sun, Y., Huang, H. W., Cannon, C. H. (2014). Footprints of divergent selection in natural populations of Castanopsis fargesii (Fagaceae). Heredity 113, 533–541. doi: 10.1038/hdy.2014.58

Li, N., Yang, Y., Xu, F., Chen, X., Wei, R., Li, Z., et al. (2022). Genetic diversity and population structure analysis of Castanopsis hystrix and construction of a core collection using phenotypic traits and molecular markers. Genes 13, 2383. doi: 10.3390/genes13122383

Liang, X., He, P., Liu, H., Zhu, S., Uyehara, I. K., Hou, H., et al. (2019). Precipitation has dominant influences on the variation of plant hydraulics of the native Castanopsis fargesii (Fagaceae) in subtropical China. Agric. For. Meteorol. 271, 83–91. doi: 10.1016/j.agrformet.2019.02.043

Liang, Y. Y., Shi, Y., Yuan, S., Zhou, B. F., Chen, X. Y., An, Q. Q., et al. (2022). Linked selection shapes the landscape of genomic variation in three oak species. New Phytol. 233, 555–568. doi: 10.1111/nph.17793

Lin, R., Ding, L., Casola, C., Ripoll, D. R., Feschotte, C., Wang, H. (2007). Transposase-derived transcription factors regulate light signaling in Arabidopsis. Science 318, 1302–1305. doi: 10.1126/science.1146281

Liu, Y., Wei, H., Ma, M., Li, Q., Kong, D., Sun, J., et al. (2019). Arabidopsis FHY3 and FAR1 regulate the balance between growth and defense responses under shade conditions. Plant Cell 31, 2089–2106. doi: 10.1105/tpc.18.00991

Majoros, W. H., Pertea, M., Salzberg, S. L. (2004). TigrScan and GlimmerHMM: two open source ab initio eukaryotic gene-finders. Bioinformatics 20, 2878–2879. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth315

Marcais, G., Kingsford, C. (2011). A fast, lock-free approach for efficient parallel counting of occurrences of k-mers. Bioinformatics 27, 764–770. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr011

Mishra, B., Gupta, D. K., Pfenninger, M., Hickler, T., Langer, E., Nam, B., et al. (2018). A reference genome of the European beech (Fagus sylvatica l.). Gigascience 7, 1–8. doi: 10.1093/gigascience/giy063

Mishra, B., Ulaszewski, B., Meger, J., Aury, J. M., Bodénès, C., Lesur-Kupin, I., et al. (2022). A chromosome-level genome assembly of the European beech (Fagus sylvatica) reveals anomalies for organelle DNA integration, repeat content and distribution of SNPs. Front. Genet. 12 2748. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2021.691058

Murat, F., Zhang, R., Guizard, S., Gavranovic, H., Flores, R., Steinbach, D., et al. (2015). Karyotype and gene order evolution from reconstructed extinct ancestors highlight contrasts in genome plasticity of modern rosid crops. Genome Biol. Evol. 7, 735–749. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evv014

Naish, M., Alonge, M., Wlodzimierz, P., Tock, A. J., Abramson, B. W., Schmücker, A., et al. (2021). The genetic and epigenetic landscape of the Arabidopsis centromeres. Science 374, eabi7489. doi: 10.1126/science.abi7489

Nawrocki, E. P., Eddy, S. R. (2013). Infernal 1.1: 100-fold faster RNA homology searches. Bioinformatics 29, 2933–2935. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt509

Nguyen, L. T., Schmidt, H. A., von Haeseler, A., Minh, B. Q. (2015). IQ-TREE: A fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 32, 268–274. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msu300

Oh, S. H., Manos, P. S. (2008). Molecular phylogenetics and cupule evolution in fagaceae as inferred from nuclear CRABS CLAW sequences. Taxon 57, 434–451. doi: 10.2307/25066014

Ou, S., Jiang, N. (2018). LTR_retriever: A highly accurate and sensitive program for identification of long terminal repeat retrotransposons. Plant Physiol. 176, 1410–1422. doi: 10.1104/pp.17.01310

Persson, S., Paredez, A., Carroll, A., Palsdottir, H., Doblin, M., Poindexter, P., et al. (2007). Genetic evidence for three unique components in primary cell-wall cellulose synthase complexes in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 104, 15566–15571. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706592104

Petit, R. J., Carlson, J., Curtu, A. L., Loustau, M. L., Plomion, C., González-Rodríguez, A., et al. (2013). Fagaceae trees as models to integrate ecology, evolution and genomics. New Phytol. 197, 369–371. doi: 10.1111/nph.12089

Plomion, C., Aury, J. M., Amselem, J., Leroy, T., Murat, F., Duplessis, S., et al. (2018). Oak genome reveals facets of long lifespan. Nat. Plants 4, 440–452. doi: 10.1038/s41477-018-0172-3

Price, M. N., Dehal, P. S., Arkin, A. P. (2009). FastTree: computing large minimum evolution trees with profiles instead of a distance matrix. Mol. Biol. Evol. 26, 1641–1650. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msp077

Price, A. L., Jones, N. C., Pevzner, P. A. (2005). De novo identification of repeat families in large genomes. Bioinformatics 21, i351–i358. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti1018

Pryszcz, L. P., Gabaldón, T. (2016). Redundans: an assembly pipeline for highly heterozygous genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, e113–e113. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw294

Ramos, A. M., Usié, A., Barbosa, P., Barros, P. M., Capote, T., Chaves, I., et al. (2018). The draft genome sequence of cork oak. Sci. Data 5, 1–12. doi: 10.1038/sdata.2018.69

Rennenberg, H., Wildhagen, H., Ehlting, B. (2010). Nitrogen nutrition of poplar trees. Plant Biol. 12, 275–291. doi: 10.1111/j.1438-8677.2009.00309.x

Richmond, T. A., Somerville, C. R. (2000). The cellulose synthase superfamily. Plant Physiol. 124, 495–498. doi: 10.1104/pp.124.2.495

Seppey, M., Manni, M., Zdobnov, E. M. (2019). BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness. Gene prediction: Methods Protoc. 1962, 227–245. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-9173-0_14

Shen, W., Le, S., Li, Y., Hu, F. (2016). SeqKit: A cross-platform and ultrafast toolkit for FASTA/Q file manipulation. PLoS One 11, e163962. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0163962

Shi, M. M., Michalski, S. G., Chen, X. Y., Chen, X. Y., Durka, W. (2011). Isolation by elevation: genetic structure at neutral and putatively non-neutral loci in a dominant tree of subtropical forests, Castanopsis eyrei. PLoS One 6, e21302. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021302

Slocum, R. D. (2005). Genes, enzymes and regulation of arginine biosynthesis in plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 43, 729–745. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2005.06.007

Song, J. M., Xie, W. Z., Wang, S., Guo, Y. X., Koo, D. H., Kudrna, D., et al. (2021). Two gap-free reference genomes and a global view of the centromere architecture in rice. Mol. Plant 14, 1757–1767. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2021.06.018

Sork, V. L., Cokus, S. J., Fitz-Gibbon, S. T., Zimin, A. V., Puiu, D., Garcia, J. A., et al. (2022). High-quality genome and methylomes illustrate features underlying evolutionary success of oaks. Nat. Commun. 13 2047. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-29584-y

Sork, V. L., Fitz-Gibbon, S. T., Puiu, D., Crepeau, M., Gugger, P. F., Sherman, R., et al. (2016). First draft assembly and annotation of the genome of a california endemic oak Quercus lobata nee (Fagaceae). G3: Genes Genomes Genet. 6, 3485–3495. doi: 10.1534/g3.116.030411

Stanke, M., Keller, O., Gunduz, I., Hayes, A., Waack, S., Morgenstern, B. (2006). AUGUSTUS: ab initio prediction of alternative transcripts. Nucleic Acids Res. 34, W435–W439. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl200

Sun, Y., Guo, J., Zeng, X., Chen, R., Feng, Y., Chen, S., et al. (2022). Chromosome-scale genome assembly of Castanopsis tibetana provides a powerful comparative framework to study the evolution and adaptation of fagaceae trees. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 22, 1178–1189. doi: 10.1111/1755-0998.13539

Sun, Y., Hu, H., Huang, H., Vargas-Mendoza, C. F. (2014). Chloroplast diversity and population differentiation of Castanopsis fargesii (Fagaceae): a dominant tree species in evergreen broad-leaved forest of subtropical China. Tree Genet. Genomes 10, 1531–1539. doi: 10.1007/s11295-014-0776-3

Sun, Y., Surget-Groba, Y., Gao, S. (2016). Divergence maintained by climatic selection despite recurrent gene flow: a case study of Castanopsis carlesii (Fagaceae). Mol. Ecol. 25, 4580–4592. doi: 10.1111/mec.13764

Tang, H., Bowers, J. E., Wang, X., Ming, R., Alam, M., Paterson, A. H. (2008). Synteny and collinearity in plant genomes. Science 320, 486–488. doi: 10.1126/science.1153917

Vurture, G. W., Sedlazeck, F. J., Nattestad, M., Underwood, C. J., Fang, H., Gurtowski, J., et al. (2017). GenomeScope: Fast reference-free genome profiling from short reads. Bioinformatics 33, 2202–2204. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx153

Wang, J., Hong, P., Qiao, Q., Zhu, D., Zhang, L., Lin, K., et al. (2022a). Chromosome-level genome assembly provides new insights into Japanese chestnut (Castanea crenata) genomes. Front. Plant Sci. 13. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.1049253

Wang, S., Liang, H., Wang, H., Li, L., Xu, Y., Liu, Y., et al. (2022b). The chromosome-scale genomes of Dipterocarpus turbinatus and Hopea hainanensis (Dipterocarpaceae) provide insights into fragrant oleoresin biosynthesis and hardwood formation. Plant Biotechnol. J. 20, 538–553. doi: 10.1111/pbi.13735

Wang, Y., Tang, H., Debarry, J. D., Tan, X., Li, J., Wang, X., et al. (2012). MCScanX: A toolkit for detection and evolutionary analysis of gene synteny and collinearity. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, e49. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1293

Wang, J., Tian, S., Sun, X., Cheng, X., Duan, N., Tao, J., et al. (2020). Construction of pseudomolecules for the Chinese chestnut (Castanea mollissima) genome. G3: Genes Genomes Genet. 10, 3565–3574. doi: 10.1534/g3.120.401532

Watanabe, M., Kitaoka, S., Eguchi, N., Watanabe, Y., Satomura, T., Takagi, K., et al. (2014). Photosynthetic traits and growth of Quercus mongolica var. crispula sprouts attacked by powdery mildew under free-air CO2 enrichment. Eur. J. For. Res. 133, 725–733. doi: 10.1007/s10342-013-0744-8

Wilf, P., Nixon, K. C., Gandolfo, M. A., Cúneo, N. R. (2019). Eocene Fagaceae from Patagonia and gondwanan legacy in Asian rainforests. Science 364, eaaw5139. doi: 10.1126/science.aaw5139

Xu, Z., Wang, H. (2007). LTR_FINDER: An efficient tool for the prediction of full-length LTR retrotransposons. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, W265–W268. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm286

Yang, Z. (2007). PAML 4: Phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Mol. Biol. Evol. 24, 1586–1591. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm088

You, Y., Huang, X., Zhu, H., Liu, S., Liang, H., Wen, Y., et al. (2018). Positive interactions between Pinus massoniana and Castanopsis hystrix species in the uneven-aged mixed plantations can produce more ecosystem carbon in subtropical China. For. Ecol. Managemen 410, 193–200. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2017.08.025

Yuan, S., Shi, Y., Zhou, B. F., Liang, Y. Y., Chen, X. Y., An, Q. Q., et al. (2023). Genomic vulnerability to climate change in Quercus acutissima, a dominant tree species in East Asian deciduous forests. Mol. Ecol 00, 1–17. doi: 10.1111/mec.16843

Zdobnov, E. M., Apweiler, R. (2001). InterProScan–an integration platform for the signature-recognition methods in InterPro. Bioinformatics 17, 847–848. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.9.847

Zhang, P., He, Y., Feng, Y., De La Torre, R., Jia, H., Tang, J., et al. (2019a). An analysis of potential investment returns of planted forests in south China. New Forests 50, 943–968. doi: 10.1007/s11056-019-09708-x

Zhang, R. G., Li, G. Y., Wang, X. L., Dainat, J., Wang, Z. X., Ou, S., et al. (2022). TEsorter: An accurate and fast method to classify LTR-retrotransposons in plant genomes. Horticulture Res. 9, uhac017. doi: 10.1093/hr/uhac017

Zhang, Z., Xiao, J., Wu, J., Zhang, H., Liu, G., Wang, X., et al. (2012). ParaAT: A parallel tool for constructing multiple protein-coding DNA alignments. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 419, 779–781. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.02.101

Zhang, X., Zhang, S., Zhao, Q., Ming, R., Tang, H. (2019b). Assembly of allele-aware, chromosomal-scale autopolyploid genomes based on Hi-c data. Nat. Plants 5, 833–845. doi: 10.1038/s41477-019-0487-8

Zhao, Z., Liu, Y., Tian, Z. W., Jia, H. Y., Zhao, R. R., An, N. (2020). Dynamics of seed rain, soil seed bank and seedling regeneration of Castanopsis hystrix. Sci. Silvae Sin. 56, 37–49. doi: 10.11707/j.1001-7488.20200505

Zhou, X., Liu, N., Jiang, X., Qin, Z., Farooq, T. H., Cao, F., et al. (2022c). A chromosome-scale genome assembly of Quercus gilva: Insights into the evolution of Quercus section Cyclobalanopsis (Fagaceae). Front. Plant Sci. 13. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.1012277

Zhou, B. F., Shi, Y., Chen, X. Y., Yuan, S., Liang, Y. Y., Wang, B. (2022a). Linked selection, ancient polymorphism, and ecological adaptation shape the genomic landscape of divergence in Quercus dentata. J. Systematics Evol. 60, 1344–1357. doi: 10.1111/jse.12817

Keywords: Castanopsis hystrix, cellulose synthase (CesA) gene, chromosome-scale genome assembly, comparative genomic analysis, gene family

Citation: Huang W-C, Liao B, Liu H, Liang Y-Y, Chen X-Y, Wang B and Xia H (2023) A chromosome-scale genome assembly of Castanopsis hystrix provides new insights into the evolution and adaptation of Fagaceae species. Front. Plant Sci. 14:1174972. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2023.1174972

Received: 27 February 2023; Accepted: 22 March 2023;

Published: 25 April 2023.

Edited by:

Kai-Hua Jia, Shandong Academy of Agricultural Sciences, ChinaReviewed by:

Jie Gao, Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), ChinaCopyright © 2023 Huang, Liao, Liu, Liang, Chen, Wang and Xia. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hanhan Xia, eGlhaGFuaGFuQHpoa3UuZWR1LmNu

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.