94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Plant Sci. , 02 March 2023

Sec. Plant Breeding

Volume 14 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2023.1147019

This article is part of the Research Topic Genetics and Molecular Breeding in Cereal Crops View all 29 articles

Dengan Xu1†

Dengan Xu1† Qianlin Hao1†

Qianlin Hao1† Tingzhi Yang1

Tingzhi Yang1 Xinru Lv1

Xinru Lv1 Huimin Qin1

Huimin Qin1 Yalin Wang1

Yalin Wang1 Chenfei Jia1

Chenfei Jia1 Wenxing Liu1

Wenxing Liu1 Xuehuan Dai1

Xuehuan Dai1 Jianbin Zeng1

Jianbin Zeng1 Hongsheng Zhang1

Hongsheng Zhang1 Zhonghu He2

Zhonghu He2 Xianchun Xia2

Xianchun Xia2 Shuanghe Cao2*

Shuanghe Cao2* Wujun Ma1*

Wujun Ma1*Wheat coleoptile is a sheath-like structure that helps to deliver the first leaf from embryo to the soil surface. Here, a RIL population consisting of 245 lines derived from Zhou 8425B × Chinese Spring cross was genotyped by the high-density Illumina iSelect 90K assay for coleoptile length (CL) QTL mapping. Three QTL for CL were mapped on chromosomes 2BL, 4BS and 4DS. Of them, two major QTL QCL.qau-4BS and QCL.qau-4DS were detected, which could explain 9.1%–22.2% of the phenotypic variances across environments on Rht-B1 and Rht-D1 loci, respectively. Several studies have reported that Rht-B1b may reduce the length of wheat CL but no study has been carried out at molecular level. In order to verify that the Rht-B1 gene is the functional gene for the 4B QTL, an overexpression line Rht-B1b-OE and a CRISPR/SpCas9 line Rht-B1b-KO were studied. The results showed that Rht-B1b overexpression could reduce the CL, while loss-of-function of Rht-B1b would increase the CL relative to that of the null transgenic plants (TNL). To dissect the underlying regulatory mechanism of Rht-B1b on CL, comparative RNA-Seq was conducted between Rht-B1b-OE and TNL. Transcriptome profiles revealed a few key pathways involving the function of Rht-B1b in coleoptile development, including phytohormones, circadian rhythm and starch and sucrose metabolism. Our findings may facilitate wheat breeding for longer coleoptiles to improve seedling early vigor for better penetration through the soil crust in arid regions.

Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) is one of the most important food crops in the world, providing large amounts of starch, rich protein and dietary fiber for humans (Asseng et al., 2020). Maintenance of high and stable wheat yields is crucial for global food security (Boyer, 2004). Drought is an important abiotic stress seriously limiting wheat production (Gupta et al., 2020). Arid and semi-arid regions account for about 60% of global crop production, and drought stress caused by frequent extreme weather events often leads to severe reduction of wheat production (Puttamadanayaka et al., 2020). To ensure the emergence rate under drought stress, deeper sowing is often adopted for better utilization of the water in soil (Zhao et al., 2022). However, a sowing depth beyond the coleoptile length (CL) will result in poor stand establishment, late emergence, and slow early leaf development (BR, 1976; Schillinger et al., 1998). Wheat coleoptiles facilitate the stem and the first leaf to break the ground, and directly determine the maximum sowing depth (Rebetzke et al., 2007a; Rebetzke et al., 2014). However, the short coleoptiles of modern semi-dwarf wheat varieties reduce emergence when sown deep (Zhao et al., 2022). Understanding the genetic basis for CL will help developing high-yield semi-dwarf varieties with longer coleoptiles and suitable for deep sowing. Previous studies have demonstrated that CL has high heritability and additive effects and is controlled by multiple genes (Rebetzke et al., 2004; Rebetzke et al., 2007b). Hence, it is feasible to increase the CL through genetic manipulation.

In the 1960s and 1970s, the wide application of dwarf genes Rht1 (Rht-B1b) and Rht2 (Rht-D1b) combined with the increased application of chemical fertilizer greatly promoted the increase of wheat yield, which was called the “Green Revolution” of wheat (Peng et al., 1999; Hedden, 2003). However, compared with the wild type Rht-B1a, the dwarf gene, while improving the resistance to colonization and harvesting index, led to increased nitrogen fertilizer requirement, decreased 1000-grain weight, lower grain protein content, drought tolerance, lower anthers exposure rate and susceptibility to scab (Tang et al., 2009; Lanning et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2013; He et al., 2016). Genetic analysis has also predicted that Rht-B1b and Rht-D1b loci have certain shortening effects on the CL of wheat, but there has been no further evidence for this speculation (Ellis et al., 2004; Rebetzke et al., 2007b; Yu and Bai, 2010; Li et al., 2011). In contrast, other two widely used Rht genes, Rht8 and Rht24, have been proved to have no negative effect on CL, providing an opportunity to breed semi-dwarfing wheat cultivars with long coleoptiles (Würschum et al., 2017; Chai et al., 2022; Tian et al., 2022; Xiong et al., 2022).

Here, we demonstrated that Rht-B1 is the functional gene underlying a CL QTL on chromosome 4B and its dwarfing allele (Rht-B1b) reduces the CL through multiple pathways such as phytohormones, circadian rhythm and starch and sucrose metabolism. These results provide valuable information for wheat breeding of longer coleoptiles to improve the seedling early vigor and penetration through soil crust in arid regions.

A total of 245 F2:10 RILs derived from the cross of Zhou 8425B × Chinese Spring were used in this study. Zhou 8425B (Pedigree: Zhou 78A/Annong 7959) and Chinese Spring are an elite facultative wheat line and Chinese landrace, respectively. Zhou 8425B contains two dwarfing alleles Rht-B1b and Rht-D1b and has a short coleoptile length (CL) of about 3.3 cm. Chinese Spring contains two wildtype alleles Rht-B1a and Rht-D1a, which contribute to a long CL of about 4.8 cm. Seeds were sampled from plants grown and harvested at Shijiazhuang of Hebei Province and Qingdao of Shandong Province during the 2020–2021 and 2021–2022 cropping seasons, respectively. Good-quality seeds without any visible damage were selected for all lines. Seeds of all parental and progeny lines were sown in cylindrical pots (100 mm high and 80 mm in diameter) at a sowing depth of 2 cm below the soil surface. The CL was determined from the scutellum to the tip of the coleoptile.

For the Zhou 8425B × Chinese Spring population, the 245 RILs and their parents were genotyped with the 90K iSelect SNP array (Wang et al., 2014). Twenty-one linkage groups corresponding to the 21 chromosomes were constructed from 14,955 polymorphic markers. All linkage maps covered 2290.06 cM with marker densities of 7.04 (A), 8.60 (B) and 2.19 (D) markers per cM (Wen et al., 2017). Broad-sense heritability was estimated using IciMapping 4.1 software (https://isbreeding.caas.cn/index.htm). Quantitative trait loci (QTLs) mapping was conducted using IciMapping 4.1 software with inclusive composite interval mapping (ICIM) algorithm (Li et al., 2007). The CL of all lines and the average phenotypic values from the two environments were used for QTL detection. The mapping parameters were chosen as step=1.0 cM and PIN = 0.01. A LOD threshold of 2.5 was chosen for declaration of putative QTLs.

To study the association between Rht-B1 and the 4B QTL in the current study, an overexpression line and loss of function line of Rht-B1 were created. The complete coding sequence (CDS) of Rht-B1b (GenBank: MG681100.1) was overexpressed in a hexaploid wheat cultivar Fielder (Rht-B1b and Rht-D1a) under driving by maize ubiquitin promoter (All primers were listed in Table S1). CRISPR/SpCas9 was used to create knockout line of Rht-B1b. The sgRNA (PAM-guide sequence 5’-GGAGCCGTTCATGCTGCAG-3’) was designed to target conserved regions of Rht-B1b. The resultant construct was transformed into immature embryos by the Agrobacterium tumefaciens (Ishida et al., 2015). Sixty good-quality seeds of each transgenic null lines (TNL), Rht-B1b overexpression lines (Rht-B1b-OE) and Rht-B1b CRISPR/SpCas9 edited lines (Rht-B1b-KO) were evenly sown in ten 10 cm (top diameter) × 8.9 cm (height) plant pots with a sowing depth of 2 cm below the soil surface. Before the coleoptile broke the ground, coleoptile tips and whole coleoptiles of ten TNL and Rht-B1b-OE plants were collected and immediately put into liquid nitrogen for RNA-Seq. Each group included three biological replicates.

Total RNA of three biological replicates was extracted using the TRIzol® reagent, and mRNA was purified from total RNA using poly-T oligo-attached magnetic beads. The first strand cDNA was synthesized using random hexamer primer and RNase H. Subsequently, the second strand cDNA synthesis was obtained using DNA Polymerase I and RNase H. Library preparation for RNA-Seq was conducted by Novogene and sequenced on an Illumina Novaseq platform with 1 ug of total RNA (http://www.novogene.com/).

IWGSC RefSeq v2.1 and annotation v2.1 were used for the reference genome and gene model annotation (Zhu et al., 2021). Raw data were processed to obtain clean reads by removal of adapter, ploy-N and low-quality reads. Paired-end clean reads were aligned to the reference genome using Hisat2 (Kim et al., 2019). FeatureCounts was used to count the read numbers mapped to each gene (Liao et al., 2014). Differential expression analysis was performed using the DESeq2 R package (Love et al., 2014). Genes with an adjusted P-value < 0.05 found by DESeq2 were assigned as differentially expressed genes (DEG). GO and KEGG enrichment analysis of DEGs were implemented by the TBtools (Chen et al., 2020). GO terms and KEGG pathways with corrected P-value lower than 0.05 were considered as significantly enriched by the DEGs.

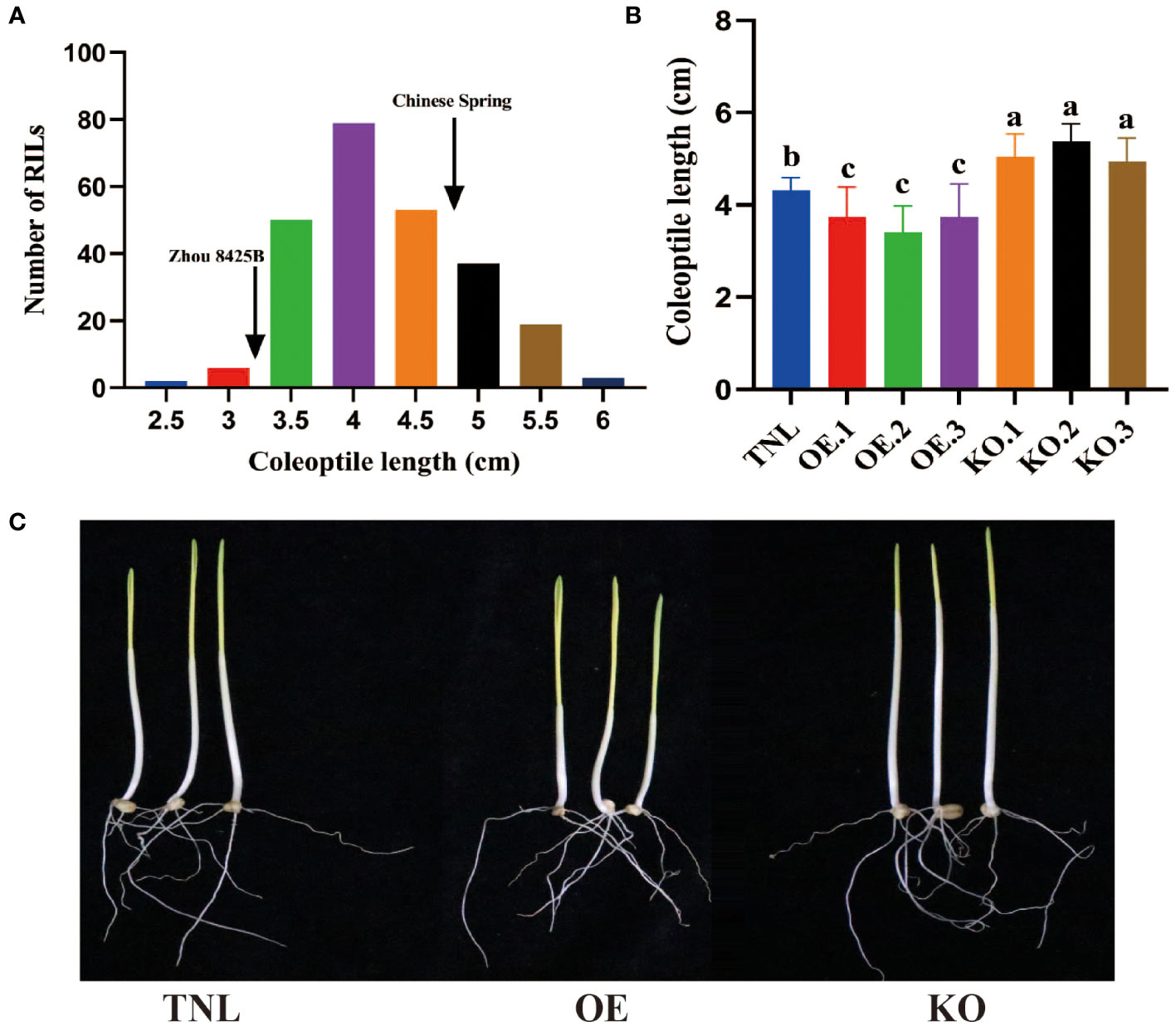

The parental lines, Zhou 8425B and Chinese Spring, differed significantly (P < 0.05) for coleoptile length (CL). Based on data averaged across all environments, CL ranged from 2.5 to 6.1 cm with an average of 4.0 cm. CL showed continuous variation in RIL population and had a high heritability of 0.86 (Figure 1A). Three QTLs for CL were identified on chromosomes 2BL, 4BS and 4DS in the Zhou 8425B × Chinese Spring population (Table 1). Two major QTLs, QCL.qau-4BS and QCL.qau-4DS, were stably detected in all environments, which explained 9.1%–22.2% of the phenotypic variance across environments (Table 1). Based on the genomic position of the flanking markers, we found that QCL.qau-4BS and QCL.qau-4DS spanned the Rht-B1 and Rht-D1 loci, respectively. QCL.qau-2BL explained about 3.0%–3.1% of phenotypic variance, and thus was a minor QTL for CL.

Figure 1 Frequency distributions of RILs for CL and effects of Rht-B1b on coleoptiles of wheat. (A) Frequency distributions of 245 recombinant inbred lines (RILs) in Zhou 8425B × Chinese Spring population for mean values of coleoptile length (CL). Arrows indicate mean values of the parental lines. Coleoptile length (B) and image of seedlings (C) of Rht-B1b overexpressing lines (OE), Rht-B1b knockout lines (KO) and transgenic null lines (TNL). Bars represent standard deviations of thirty biological replicates. Different letters on the bars indicate significant differences in given traits at P < 0.05 between different lines.

Many studies have reported CL QTL on the Rht-B1 locus, indicating that Rht-B1b may reduce wheat CL (Botwright et al., 2001; Li et al., 2017). However, there has been no direct evidence for this speculation. Here, Rht-B1b overexpression and CRISPR/SpCas9 gene-editing were performed and homozygous plants were generated by self-crossing for CL evaluation. The results demonstrated that Rht-B1b overexpression could reduce the CL about 8.6%, while loss-of-function of Rht-B1b would increase the CL about 17.9% relative to that of null transgenic plants (TNL) (Figures 1B, C). Thus, Rht-B1 can be a target gene of QCL.qau-4BS.

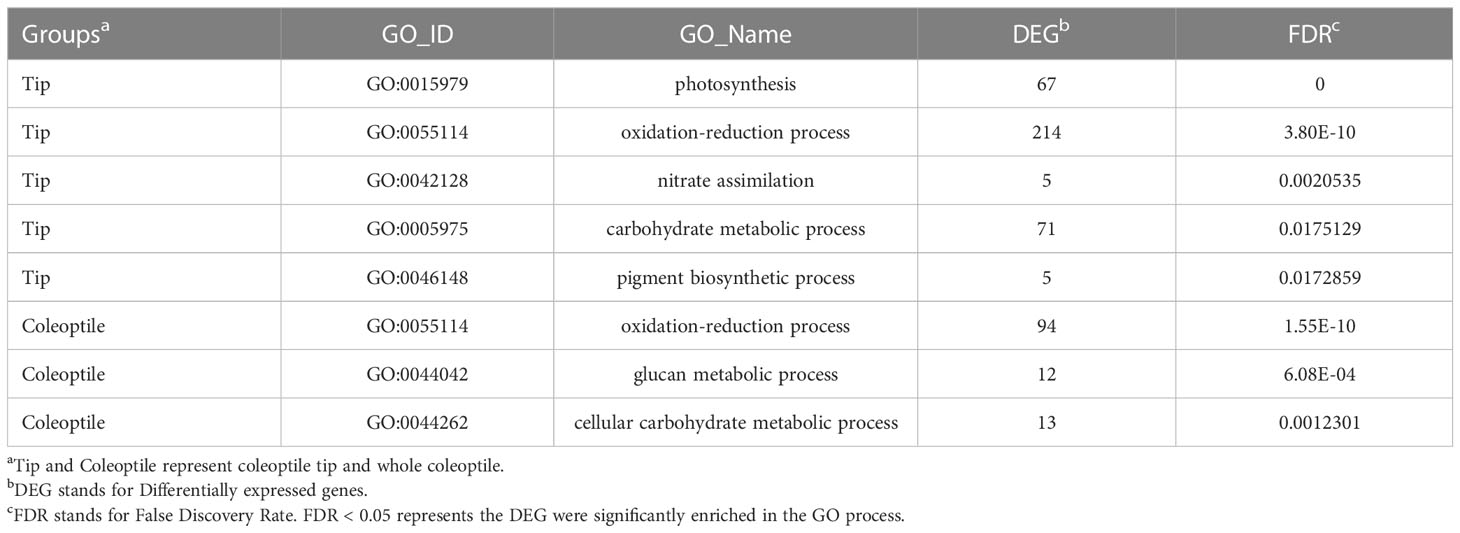

Although Rht-B1b is known to reduce the CL, the underlying regulatory mechanism remains unclear. To dissect the regulatory mechanism, whole coleoptiles and coleoptile tips of TNL and Rht-B1b-OE were collected for RNA-Seq analysis before the coleoptile breaks the ground. Compared with those of TNL, 142/523 and 191/1993 differentially expressed genes (DEG) were upregulated/downregulated by Rht-B1b in the transcriptome of whole coleoptile and coleoptile tips (Table S2 and S3). There were more down-regulated DEGs than up-regulated DEGs, indicating that Rht-B1b mainly represses the gene expression in coleoptiles. GO enrichment analysis of coleoptile tips revealed that Rht-B1b mainly reduces the CL via the process of “photosynthesis”, “oxidation-reduction process”, “nitrate assimilation carbohydrate metabolic process”, and “pigment biosynthetic process”. In the whole coleoptile, DEGs were enriched in the GO processes of “oxidation-reduction”, “glucan metabolism” and “cellular carbohydrate metabolism” (Table 2). In the coleoptile tips, DEGs were mainly enriched in the GO processes of “photosynthesis”, “oxidation-reduction”, “nitrate assimilation”, “carbohydrate metabolism” and “pigment biosynthetic process” (Table 2).

Table 2 Enrichment analysis of the most significant GO processes in the transcriptome of coleoptile tips and whole coleoptiles.

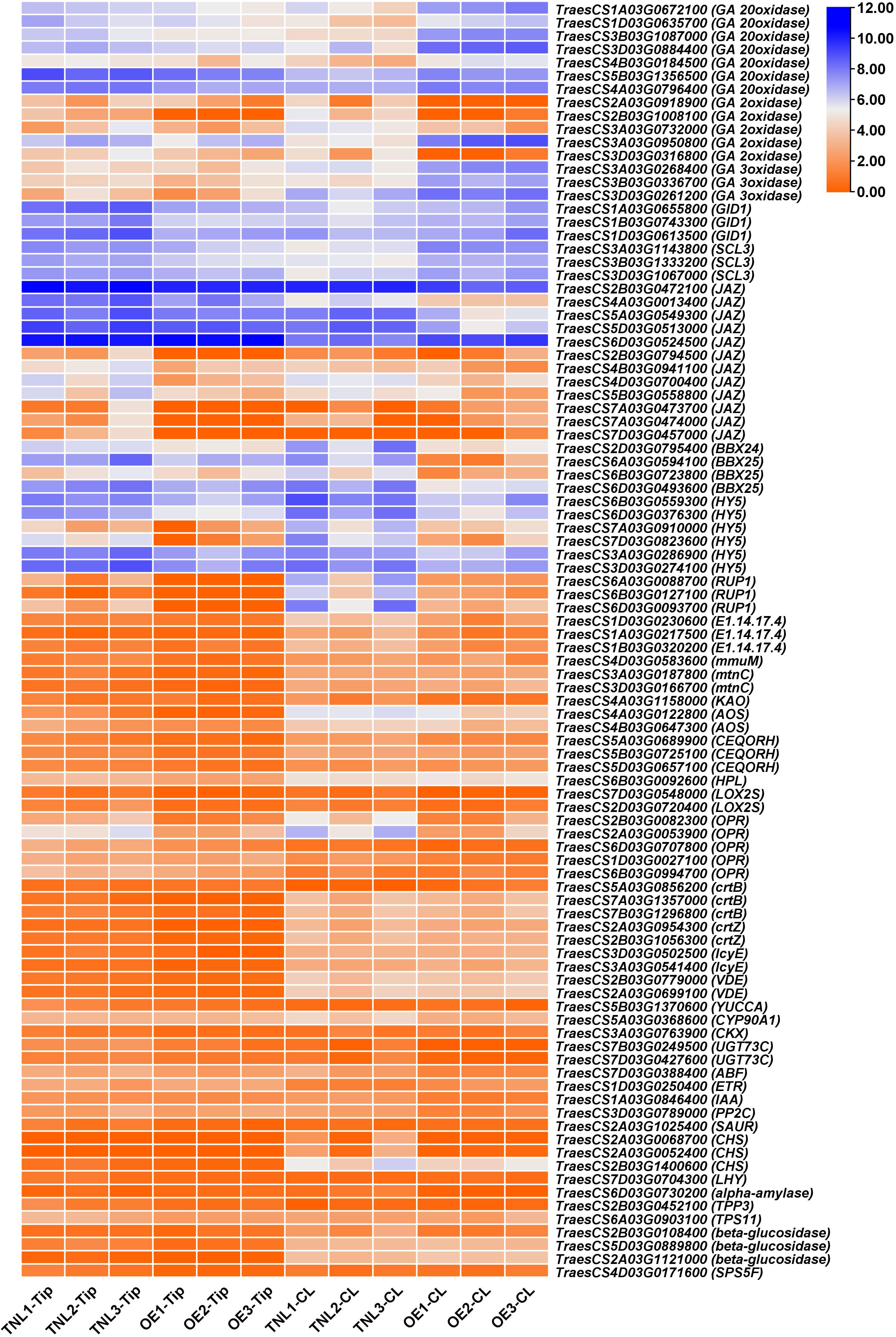

Previous studies showed that hypocotyl elongation is regulated by endogenous regulators, such as phytohormones, circadian clock, sucrose, and environmental stimuli (Saibo et al., 2003; Simon et al., 2018). Interestingly, many DEGs were enriched in the KEGG pathway of plant hormone signal transduction, alpha-linolenic acid metabolism (jasmonic acid), brassinosteroid biosynthesis, carotenoid biosynthesis (abscisic acid), cysteine and methionine metabolism (ethylene), diterpenoid biosynthesis (gibberellin), tryptophan metabolism (auxin), zeatin biosynthesis (cytokinine), circadian rhythm, and starch and sucrose metabolism (Figure 2). Thus, Rht-B1b might play an important role in integrating multiple signal transduction pathways in the wheat coleoptile development.

Figure 2 Putative key downstream genes of Rht-B1b for coleoptile development. TNL, OE, Tip and CL represents transgenic null plant, Rht-B1b-OE plant, coleoptile tip and whole coleoptile, respectively. Orange and blue colors show genes with low and high expression level, respectively.

Numerous studies have demonstrated a positive association between wheat CL and plant number under deep sowing (Hadjichristodoulou et al., 1977; Matsui et al., 2002). However, the two gibberellin-insensitive dwarfing genes, Rht-B1b and Rht-D1b, tend to cause shorter CL and low seedling emergence rate (Schillinger et al., 1998; Rebetzke et al., 2007b). Here, we generated Rht-B1b over-expressing and CRISPR/SpCas9 editing plants to study its influence on coleoptile development. As a result, overexpression of Rht-B1b reduced the CL, while its loss of function increased the CL. Rht-B1b encodes an N-terminal truncated DELLA protein (lack of DELLA and TVHYNP motifs), which is gibberellin-insensitive protein in wheat (Van De Velde et al., 2021). DELLA proteins encoded by the Rht-B1a gene are the downstream repressors of GA signal transduction and, GA induces the degradation of DELLA proteins via the ubiquitin/proteasome pathway (Itoh et al., 2003). Thus, Rht-B1b led to a reduction of CL compared with tall allele Rht-B1a since the GA-induced seedling growth was repressed (Alabadií et al., 2004). So far, there has been no study to validate the effect of Rht-B1b on CL, not to mention the underlying genetic pathway. To uncover the regulatory mechanism of Rht-B1b on CL, a transcriptome analysis was conducted to dissect the underlying genetic pathway.

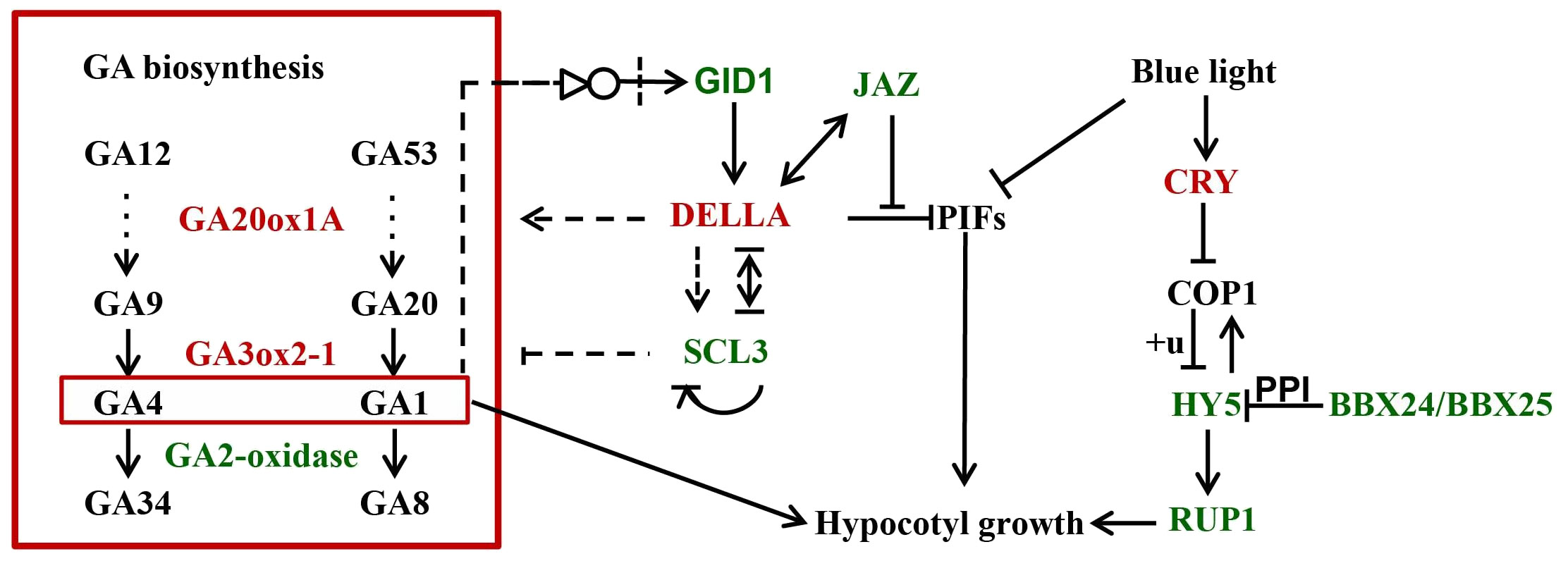

A few studies have demonstrated that, in Arabidopsis, SCL3 and DELLA antagonize each other in modulating downstream GA responses and maintaining GA homeostasis via feedback regulation of GA biosynthetic genes (Zhang et al., 2011). SCL3 functions as a positive regulator of GA signaling, which induces the expression of GA biosynthesis genes and autoregulates its own expression via direct interaction with DELLA. In our transcriptome, 16 genes related to GA biosynthesis, three GA receptor GID1 genes and three SCL3 genes were identified as DEGs between Rht-B1b-OE and TNL, indicating that wheat SCL3 and DELLA antagonize each other in maintaining GA homeostasis and GA responses as in Arabidopsis (Figure 2, 3). In addition, DELLAs can physically interact with and block PIF3 and PIF4 activities by sequestering the transcription factors from binding to their targets, which ultimately results in the inhibition of hypocotyl elongation (De lucas et al., 2008; Feng et al., 2008). JAZ could interrupt DELLA–PIF3 interaction, allowing more PIF transcription factors to activate plant growth (Yang et al., 2012). In our transcriptome, several homologs of JAZs were down-regulated by Rht-B1b-OE (Figure 2, 3). HY5 is a key transcription factor for the regulation of seedling photomorphogenesis. COP1 negatively regulates HY5 by directly and specifically interacting with HY5 (Ang et al., 1998). BBX25 and BBX24 additively enhance COP1 and suppress HY5 functions to regulate of seedling deetiolation process in Arabidopsis (Gangappa et al., 2013). RUP1 is induced by CRYs in response to blue light, which is dependent on HY5 (Tissot and Ulm, 2020). These genes are key factors for cryptochrome blue-light signaling and their homologs in wheat were identified as DEGs, indicating that light and GAs might antagonistically regulate coleoptile in wheat (Figure 2, 3).

Figure 3 A simplified model underpinning Rht-B1b modulating coleoptile length. Black letters in the box show non-differentially expressed genes. Red and green letters show upregulated and downregulated genes by Rht-B1b, respectively. The +u represents ubiquitylation. GA represent gibberellin. The arrows show promotion of gene expression; the lines with blunt ends show repression of gene expression; the bold lines represent direct binding. The species latin prefixes in gene names are not shown.

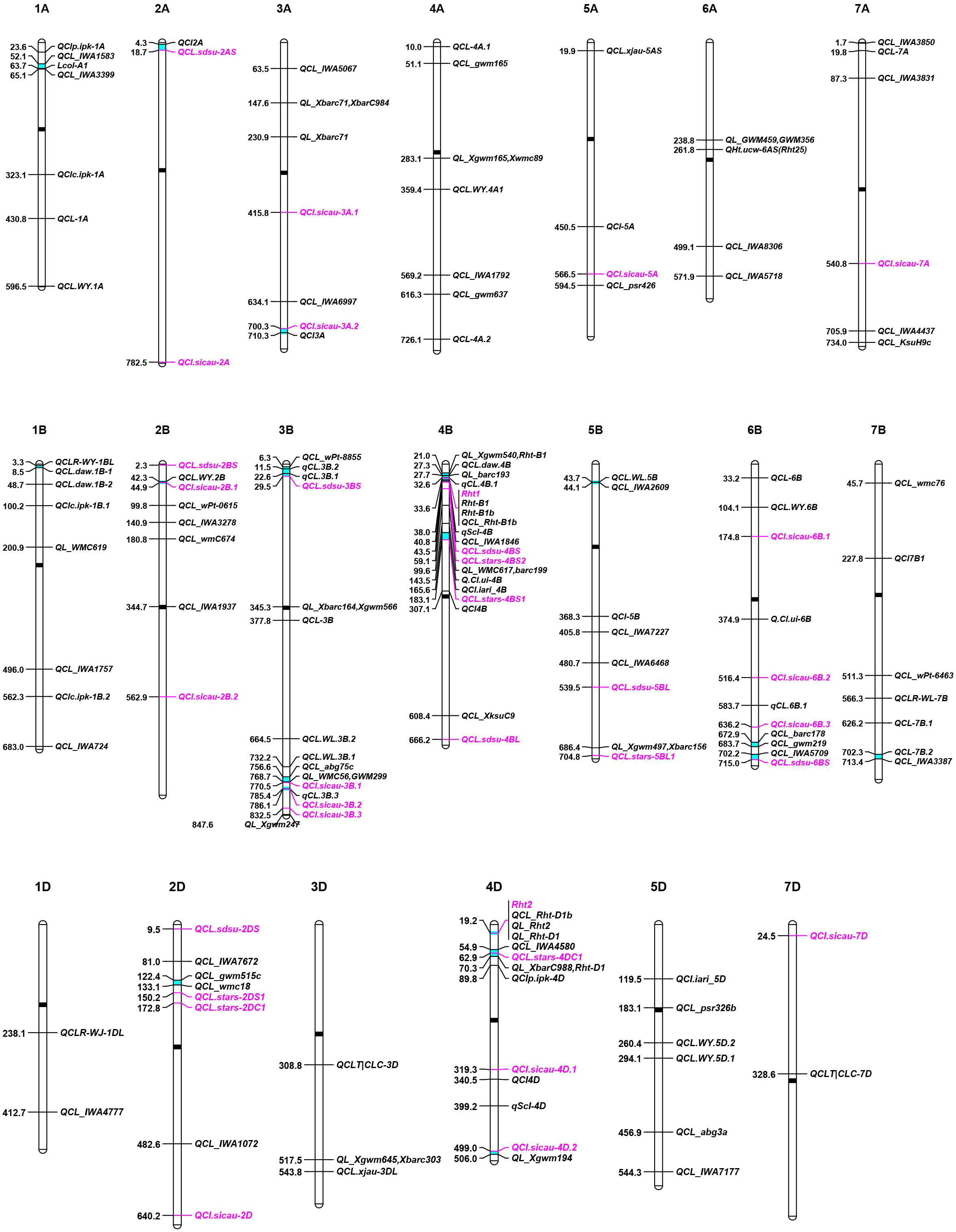

The response of plants to drought is dependent on multiple factors, including duration and severity of drought conditions, frequency of drought, and the growth stage when subjected to the drought stress (Jatayev et al., 2020). Although wheat can be grown in a variety of harsh environments, rising temperature and unpredictable drought exacerbate the impact of drought stress on wheat yield. If drought stress occurs when sowing, farmers tend to sow more seeds in a deeper depth to increase the seedling establishment rate. Short coleoptiles severely hider the application of deep sowing in wheat production since it influences the emergence rate of wheat seedlings, particularly in fields with thick stubble or crusted soil surface (Rebetzke et al., 2014). Most modern semi-dwarf wheat varieties harboring Rht-B1b or Rht-D1b have short coleoptiles and low yields under drought stress relative to tall plants (Li et al., 2017; Sidhu et al., 2020). Wheat CL is a typical quantitative trait controlled by multiple genes (Rebetzke et al., 2007a). Pyramiding of multiple QTLs in modern semi-dwarf wheat cultivars can efficiently increase the CL. Thus, a comprehensive screening was conducted on the genetic locus for CL by QTL mapping and genome wide association analysis (GWAS) from previous studies and assembled them on wheat chromosomes according to their physical locations (Figure 4). So far, a total of 114 QTLs for CL traits in wheat have been found from 20 studies of CL-related QTL mapping in wheat (Figure 4 and Table S4) (Rebetzke et al., 2001; Rebetzke et al., 2007b; Landjeva et al., 2008; Landjeva et al., 2010; Li et al., 2010; Yu and Bai, 2010; Li et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2013; Nagel et al., 2014; Rebetzke et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2014; Singh et al., 2015; Elbudony, 2017; Liu et al., 2017; Mo et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2018; Bovill et al., 2019; Puttamadanayaka et al., 2020; Francki et al., 2021; Ren et al., 2021). About 33 GWAS loci were found to be associated with CL (Figure 4 and Table S5) (Li et al., 2017; Ma et al., 2020; Sidhu et al., 2020). These genetic loci were used for QTL-rich cluster (QRC) detection, which was defined when markers from at least two independent studies were physically located in 10 Mb range (Cao et al., 2020). The genomic positions of flanking markers were obtained from the IWGSC RefSeq V2.1 (Zhu et al., 2021). A total of 18 QTL-rich clusters (QRC) for CL were found in this study (Table 3). Of them, Rht-B1 and Rht-D1 are strong candidate genes of QRC 4B-I and 4D-I, respectively. These QRC of CL provide valuable gene resources for marker-assisted selection breeding for longer coleoptiles.

Figure 4 Distribution of genetic loci for wheat coleoptile length (CL) on chromosomes. QTLs and GWAS loci are indicated in black and pink colors, respectively. The black and cyan bars in chromosomes indicate the positions of centromeres and QTL-rich clusters (QRC), respectively.

In the 1960s and 1970s, the wide application of semi-dwarf genes Rht-B1b and Rht-D1b combined with the increased application of chemical fertilizer greatly promoted the wheat yield improvement, which was referred to as the “Green Revolution” of wheat (Hedden, 2003). However, semi-dwarf wheat with Rht-B1b/Rht-D1b alleles produce lower grain yield than taller plants with Rht-B1a/Rht-D1a under drought environment (Zhang et al., 2013; Jatayev et al., 2020). Compared with wild-type Rht-B1a, semi-dwarf allele Rht-B1b resulted in shorter coleoptile. Seeds of semi-dwarf wheat cultivars are generally sown shallower than taller wheat varieties to ensure the emergence of semi-dwarf seedlings and early vigour (Rebetzke et al., 2007a; Jatayev et al., 2020). Shallow seeding in dry fields reduces emergence for varieties with short coleoptile length (Rebetzke et al., 2001; Jatayev et al., 2020). It is likely that taller wheat cultivars with Rht-B1a/Rht-D1a have higher rate of emergence than semi-dwarf wheat genotypes under early drought environment. Thus, improving lodging resistance of tall wheat has become an important research direction. Besides of reducing the height of plants, an alternative way is to breed wheat varieties with solid-stemmed stems to enhance lodging resistance in wheat (Liang et al., 2022). Wheat with tall plant height Rht-B1a/Rht-D1a allele combined with solid-stemmed stems alleles of TdDof might have high lodging and drought tolerances, long coleoptile and produce higher yield in drought field (Jatayev et al., 2020; Nilsen et al., 2020).

The data presented in the study are deposited in the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) of the National Center for Biotechnology Information in the BioProject with accession number PRJNA936995.

DX: Project administration, Investigation, Visualization, Writing, Editing and Funding acquisition. QH: Investigation, Data curation, Writing. TY: Investigation, Data curation. XL: Investigation, Data curation. HQ: Investigation. YW: Investigation. CJ: Investigation. WL: Investigation. XD: Investigation. JZ: Investigation. HZ: Investigation. ZH: Resources XX: Resources. SC: Review, Supervision and Resources. WM: Review, Supervision, and Funding acquisition. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This work was funded by the project ZR202103020229 supported by Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation, National Natural Science Foundation of China (32101733) and Shandong Agricultural Seeds Engineering Project (2021LZGC013).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2023.1147019/full#supplementary-material

Alabadií, D., Gil, J., Blaízquez, M. A., Garciía-Martiínez, J. L. (2004). Gibberellins repress photomorphogenesis in darkness. Plant Physiol. 134 (3), 1050–1057. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.035451

Ang, L. H., Chattopadhyay, S., Wei, N., Oyama, T., Okada, K., Batschauer, A., et al. (1998). Molecular interaction between COP1 and HY5 defines a regulatory switch for light control of arabidopsis development. Mol. Cell 1 (2), 213–222. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80022-2

Asseng, S., Guarin, J. R., Raman, M., Monje, O., Kiss, G., Despommier, D. D., et al. (2020). Wheat yield potential in controlled-environment vertical farms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 117 (32), 19131–19135. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2002655117

Botwright, T., Rebetzke, G., Condon, T., Richards, R. (2001). The effect of rht genotype and temperature on coleoptile growth and dry matter partitioning in young wheat seedlings. Funct. Plant Biol. 28, 417–423. doi: 10.1071/PP01010

Bovill, W. D., Hyles, J., Zwart, A. B., Ford, B. A., Perera, G., Phongkham, T., et al. (2019). Increase in coleoptile length and establishment by Lcol-A1, a genetic locus with major effect in wheat. BMC Plant Biol. 19 (1), 332. doi: 10.1186/s12870-019-1919-3

Boyer, J. S. (2004). Grain yields with limited water. J. Exp. Bot. 55 (407), 2385–2394. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erh219

BR, W. (1976). The emergence of semidwarf and standard wheats, and its association with coleoptile length. Anim. Prod Sci. 16, 411–416. doi: 10.1071/EA9760411

Cao, S., Xu, D., Hanif, M., Xia, X., He, Z. (2020). Genetic architecture underpinning yield component traits in wheat. Theor. Appl. Genet. 133 (6), 1811–1823. doi: 10.1007/s00122-020-03562-8

Chai, L., Xin, M., Dong, C., Chen, Z., Zhai, H., Zhuang, J., et al. (2022). A natural variation in ribonuclease h-like gene underlies Rht8 to confer "Green revolution" trait in wheat. Mol. Plant 15 (3), 377–380. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2022.01.013

Chen, C., Chen, H., Zhang, Y., Thomas, H. R., Frank, M. H., He, Y., et al. (2020). Tbtools: an integrative toolkit developed for interactive analyses of big biological data. Mol. Plant 13 (8), 1194–1202. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2020.06.009

De lucas, M., Daviere, J. M., Rodriguez-Falcon, M., Pontin, M., Iglesias-Pedraz, J. M., Lorrain, S., et al. (2008). A molecular framework for light and gibberellin control of cell elongation. Nature 451 (7177), 480–484. doi: 10.1038/nature06520

Elbudony, K. A. M. (2017). Genes controlling coleoptile length and seedling emergence in wheat and their role in plant height [PhD thesis, Washington State University]. Retrieved from https://rex.libraries.wsu.edu/esploro/outputs/doctoral/GENES-CONTROLLING-COLEOPTILE-LENGTH-AND-SEEDLING/99900581827501842.

Ellis, M. H., Rebetzke, G. J., Chandler, P., Bonnett, D., Spielmeyer, W., Richards, R. A. (2004). The effect of different height reducing genes on the early growth of wheat. Funct. Plant Biol. 31 (6), 583–589. doi: 10.1071/FP03207

Feng, S., Martinez, C., Gusmaroli, G., Wang, Y., Zhou, J., Wang, F., et al. (2008). Coordinated regulation of Arabidopsis thaliana development by light and gibberellins. Nature 451 (7177), 475–479. doi: 10.1038/nature06448

Francki, M. G., Stainer, G. S., Walker, E., Rebetzke, G. J., Stefanova, K. T., French, R. J. (2021). Phenotypic evaluation and genetic analysis of seedling emergence in a global collection of wheat genotypes (Triticum aestivum l.) under limited water availability. Front. Plant Sci. 12, 796176. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.796176

Gangappa, S. N., Crocco, C. D., Johansson, H., Datta, S., Hettiarachchi, C., Holm, M., et al. (2013). The Arabidopsis b-BOX protein BBX25 interacts with HY5, negatively regulating BBX22 expression to suppress seedling photomorphogenesis. Plant Cell 25 (4), 1243–1257. doi: 10.1105/tpc.113.109751

Gupta, A., Rico-Medina, A., Caño-Delgado, A. I. (2020). The physiology of plant responses to drought. Science 368, 266–269. doi: 10.1126/science.aaz7614

Hadjichristodoulou, A., Della, A., Photiades, J. (1977). Effect of sowing depth on plant establishment, tillering capacity and other agronomic characters of cereals. J. Agri Sci. 89 (1), 161–167. doi: 10.1017/S0021859600027337

He, X. Y., Lillemo, M., Shi, J. R., Wu, J. R., Bjørnstad, Å, Belova, T., et al. (2016). QTL characterization of fusarium head blight resistance in CIMMYT bread wheat line Soru1. PloS One 11 (6), e158052. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0158052

Hedden, P. (2003). The genes of the green revolution. Trends Genet. 19 (1), 5–9. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(02)00009-4

Ishida, Y., Tsunashima, M., Hiei, Y., Komari, T. (2015). Wheat (Triticum aestivum l.) transformation using immature embryos. Methods Mol. Biol. 1223, 189–198. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-1695-5_15

Itoh, H., Matsuoka, M., Steber, C. M. (2003). A role for the ubiquitin-26s-proteasome pathway in gibberellin signaling. Trends Plant Sci. 8 (10), 492–497. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2003.08.002

Jatayev, S., Sukhikh, I., Vavilova, V., Smolenskaya, S. E., Goncharov, N. P., Kurishbayev, A., et al. (2020). Green revolution 'stumbles' in a dry environment: dwarf wheat with Rht genes fails to produce higher grain yield than taller plants under drought. Plant Cell Environ. 43 (10), 2355–2364. doi: 10.1111/pce.13819

Kim, D., Paggi, J. M., Park, C., Bennett, C., Salzberg, S. L. (2019). Graph-based genome alignment and genotyping with hisat2 and hisat-genotype. Nat. Biotechnol. 37 (8), 907–915. doi: 10.1038/s41587-019-0201-4

Landjeva, S., Lohwasser, U., Börner, A. (2010). Genetic mapping within the wheat d genome reveals QTL for germination, seed vigour and longevity, and early seedling growth. Euphytica 171 (1), 129–143. doi: 10.1007/s10681-009-0016-3

Landjeva, S. L. I. O., Neumann, K. L. I. O., Lohwasser, U. L. I. O., Boerner, A. L. I. O. (2008). Molecular mapping of genomic regions associated with wheat seedling growth under osmotic stress. Biol. Plantarum 52 (2), 259–266. doi: 10.1007/s10535-008-0056-x

Lanning, S. P., Martin, J. M., Stougaard, R. N., Guillen Portal, F. R., Blake, N. K., Sherman, J. D., et al. (2012). Evaluation of near-isogenic lines for three height-reducing genes in hard red spring wheat. Crop Sci. 52 (3), 1145–1152. doi: 10.2135/cropsci2011.11.0625

Li, G., Bai, G., Carver, B. F., Elliott, N. C., Bennett, R. S., Wu, Y., et al. (2017). Genome-wide association study reveals genetic architecture of coleoptile length in wheat. Theor. Appl. Genet. 130 (2), 391–401. doi: 10.1007/s00122-016-2820-1

Li, P., Chen, J., Wu, P., Zhang, J., Chu, C., See, D., et al. (2011). Quantitative trait loci analysis for the effect of Rht-B1 dwarfing gene on coleoptile length and seedling root length and number of bread wheat. Crop Sci. 51 (6), 2561–2568. doi: 10.2135/cropsci2011.03.0116

Li, H., Ye, G., Wang, J. (2007). A modified algorithm for the improvement of composite interval mapping. Genetics 175 (1), 361–374. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.066811

Li, Z., Yuan, Q., Shi, C., Chen, J., Han, S., Tian, J. (2010). QTL mapping for coleoptile length and root length in wheat seedling. Mol. Plant Breed. 8 (3), 460–468. doi: 10.3969/mpb.008.000460

Liang, D., Zhang, M., Liu, X., Li, H., Jia, Z., Wang, D., et al. (2022). Development and identification of four new synthetic hexaploid wheat lines with solid stems. Sci. Rep-Uk 12 (1), 4898. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-08866-x

Liao, Y., Smyth, G. K., Shi, W. (2014). Featurecounts: an efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics 30 (7), 923–930. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt656

Liu, X., Zhang, H., Hu, X., Wang, H., Gao, J., Liang, S., et al. (2017). QTL mapping for drought-tolerance coefficient of seedling related traits during wheat germination. J. Nucl. Agri Sci. 2 (31), 209–217. doi: 10.11869/j.issn.100-8551.2017.02.0209

Love, M. I., Huber, W., Anders, S. (2014). Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15 (12), 550. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8

Ma, J., Lin, Y., Tang, S., Duan, S., Wang, Q., Wu, F., et al. (2020). A genome-wide association study of coleoptile length in different Chinese wheat landraces. Front. Plant Sci. 11, 677. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.00677

Matsui, T., Inanaga, S., Shimotashior, T., An, P., Sugimoto, Y. (2002). Morphological characters related to varietal differences in tolerance to deep sowing in wheat. Plant Prod Sci. 2 (2), 169–174. doi: 10.1626/pps.5.169

Mo, Y., Vanzetti, L. S., Hale, I., Spagnolo, E. J., Guidobaldi, F., Al-Oboudi, J., et al. (2018). Identification and characterization of Rht25, a locus on chromosome arm 6AS affecting wheat plant height, heading time, and spike development. Theor. Appl. Genet. 131 (10), 2021–2035. doi: 10.1007/s00122-018-3130-6

Nagel, M., Navakode, S., Scheibal, V., Baum, M., Nachit, M., Röder, M. S., et al. (2014). The genetic basis of durum wheat germination and seedling growth under osmotic stress. Biol. Plantarum 58 (4), 681–688. doi: 10.1007/s10535-014-0436-3

Nilsen, K. T., Walkowiak, S., Xiang, D., Gao, P., Quilichini, T. D., Willick, I. R., et al. (2020). Copy number variation of TdDof controls solid-stemmed architecture in wheat. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 117 (46), 28708–28718. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2009418117

Peng, J., Richards, D. E., Hartley, N. M., Murphy, G. P., Devos, K. M., Flintham, J. E., et al. (1999). 'Green revolution' genes encode mutant gibberellin response modulators. Nature 400 (6741), 256–261. doi: 10.1038/22307

Puttamadanayaka, S., Harikrishna, Balaramaiah, M., Biradar, S., Parmeshwarappa, S. V., Sinha, N., et al. (2020). Mapping genomic regions of moisture deficit stress tolerance using backcross inbred lines in wheat (Triticum aestivum l.). Sci. Rep-Uk 10 (1), 21646. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-78671-x

Rebetzke, G. J., Appels, R., Morrison, A. D., Richards, R. A., McDonald, G., Ellis, M. H., et al. (2001). Quantitative trait loci on chromosome 4B for coleoptile length and early vigour in wheat (Triticum aestivum l.). Aust. J. Agri Res. 52 (12), 1221–1234. doi: 10.1071/AR01042

Rebetzke, G. J., Ellis, M. H., Bonnett, D. G., Richards, R. A. (2007a). Molecular mapping of genes for coleoptile growth in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum l.). Theor. Appl. Genet. 114 (7), 1173–1183. doi: 10.1007/s00122-007-0509-1

Rebetzke, G. J., Richards, R. A., Fettell, N. A., Long, M., Condon, A. G., Forrester, R. I., et al. (2007b). Genotypic increases in coleoptile length improves stand establishment, vigour and grain yield of deep-sown wheat. Field Crop Res. 100 (1), 10–23. doi: 10.1016/j.fcr.2006.05.001

Rebetzke, G. J., Richards, R. A., Sirault, X. R. R., Morrison, A. D. (2004). Genetic analysis of coleoptile length and diameter in wheat. Aust. J. Agri Res. 55 (7), 733–743. doi: 10.1071/AR04037

Rebetzke, G. J., Verbyla, A. P., Verbyla, K. L., Morell, M. K., Cavanagh, C. R. (2014). Use of a large multiparent wheat mapping population in genomic dissection of coleoptile and seedling growth. Plant Biotechnol. J. 12 (2), 219–230. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12130

Ren, Y., Liu, J., Zhang, J., Dreisigacker, S., Xia, X., Geng, H. (2021). QTL mapping of drought tolerance at germination stage in wheat using the 50 k SNP array. Plant Genet. Resources: Characterization Utilization 19 (5), 453–460. doi: 10.1017/S1479262121000551

Saibo, N. J., Vriezen, W. H., Beemster, G. T., van der Straeten, D. (2003). Growth and stomata development of arabidopsis hypocotyls are controlled by gibberellins and modulated by ethylene and auxins. Plant J. 33 (6), 989–1000. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2003.01684.x

Schillinger, W. F. U. A., Donaldson, E., Allan, R. E., Jones, S. S. (1998). Winter wheat seedling emergence from deep sowing depths. Agron. J. 90 (5), 582–586. doi: 10.2134/agronj1998.00021962009000050002x

Sidhu, J. S., Singh, D., Gill, H. S., Brar, N. K., Qiu, Y., Halder, J., et al. (2020). Genome-wide association study uncovers novel genomic regions associated with coleoptile length in hard winter wheat. Front. Genet. 10, 1345. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2019.01345

Simon, N. M. L., Kusakina, J., Fernández-López, Á, Chembath, A., Belbin, F. E., Dodd, A. N. (2018). The energy-signaling hub SnRK1 is important for sucrose-induced hypocotyl elongation. Plant Physiol. 176 (2), 1299–1310. doi: 10.1104/pp.17.01395

Singh, K., Shukla, S., Kadam, S., Semwal, V. K., Singh, N. K., Khanna-Chopra, R. (2015). Genomic regions and underlying candidate genes associated with coleoptile length under deep sowing conditions in a wheat RIL population. J. Plant Biochem. Biot 24 (3), 324–330. doi: 10.1007/s13562-014-0277-3

Tang, N., Jiang, Y., He, B., Hu, Y. (2009). The effects of dwarfing genes (Rht-B1b, Rht-D1b, and Rht8) with different sensitivity to GA3 on the coleoptile length and plant height of wheat. Agri Sci. China 8 (9), 1028–1038. doi: 10.1016/S1671-2927(08)60310-7

Tian, X., Xia, X., Xu, D., Liu, Y., Xie, L., Hassan, M. A., et al. (2022). Rht24b, an ancient variation of TaGA2ox-a9, reduces plant height without yield penalty in wheat. New Phytol. 233 (2), 738–750. doi: 10.1111/nph.17808

Tissot, N., Ulm, R. (2020). Cryptochrome-mediated blue-light signalling modulates UVR8 photoreceptor activity and contributes to UV-b tolerance in Arabidopsis. Nat. Commun. 11 (1), 1323. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-15133-y

Van De Velde, K., Thomas, S. G., Heyse, F., Kaspar, R., van der Straeten, D., Rohde, A. (2021). N-terminal truncated RHT-1 proteins generated by translational reinitiation cause semi-dwarfing of wheat green revolution alleles. Mol. Plant 14 (4), 679–687. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2021.01.002

Wang, S., Wong, D., Forrest, K., Allen, A., Chao, S., Huang, B. E., et al. (2014). Characterization of polyploid wheat genomic diversity using a high-density 90 000 single nucleotide polymorphism array. Plant Biotechnol. J. 12 (6), 787–796. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12183

Wen, W., He, Z., Gao, F., Liu, J., Jin, H., Zhai, S., et al. (2017). A high-density consensus map of common wheat integrating four mapping populations scanned by the 90K SNP array. Front. Plant Sci. 8, 1389. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.01389

Würschum, T., Langer, S. M., Longin, C. F. H., Tucker, M. R., Leiser, W. L. (2017). A modern green revolution gene for reduced height in wheat. Plant J. 92 (5), 892–903. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13726

Xiong, H., Zhou, C., Fu, M., Guo, H., Xie, Y., Zhao, L., et al. (2022). Cloning and functional characterization of Rht8, a "Green revolution" replacement gene in wheat. Mol. Plant 15 (3), 373–376. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2022.01.014

Yang, D., Yao, J., Mei, C., Tong, X., Zeng, L., Li, Q., et al. (2012). Plant hormone jasmonate prioritizes defense over growth by interfering with gibberellin signaling cascade. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109 (19), E1192–E1200. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1201616109

Yu, J. B., Bai, G. H. (2010). Mapping quantitative trait loci for long coleoptile in chinese wheat landrace wangshuibai. Crop Sci. 50 (1), 43–50. doi: 10.2135/cropsci2009.02.0065

Zhang, H., Cui, F., Wang, H. (2014). Detection of quantitative trait loci (QTLs) for seedling traits and drought tolerance in wheat using three related recombinant inbred line (RIL) populations. Euphytica 196 (3), 313–330. doi: 10.1007/s10681-013-1035-7

Zhang, H., Cui, F., Wang, L., Li, J., Ding, A., Zhao, C., et al. (2013). Conditional and unconditional QTL mapping of drought-tolerance-related traits of wheat seedling using two related RIL populations. J. Genet. 92 (2), 213–231. doi: 10.1007/s12041-013-0253-z

Zhang, J., Dell, B., Biddulph, B., Drake-Brockman, F., Walker, E., Khan, N., et al. (2013). Wild-type alleles of Rht-B1 and Rht-D1as independent determinants of thousand-grain weight and kernel number per spike in wheat. Mol. Breed. 32 (4), 771–783. doi: 10.1007/s11032-013-9905-1

Zhang, Z., Ogawa, M., Fleet, C. M., Zentella, R., Hu, J., Heo, J., et al. (2011). Scarecrow-like 3 promotes gibberellin signaling by antagonizing master growth repressor della in arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108 (5), 2160–2165. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012232108

Zhang, N., Pan, R. Q., Liu, J. J., Zhang, X. L., Su, Q. N., Cui, F., et al. (2018). QTL for sensitivity of seedling height to exogenous GA3 and their effects on adult plant height in common wheat. Cereal Res. Commun. 46 (3), 412–423. doi: 10.1556/0806.46.2018.021

Zhao, Z., Wang, E., Kirkegaard, J. A., Rebetzke, G. J. (2022). Novel wheat varieties facilitate deep sowing to beat the heat of changing climates. Nat. Clim Change 12, 291–296. doi: 10.1038/s41558-022-01305-9

Keywords: wheat, coleoptile length, Rht-B1b, QTL, transcriptome

Citation: Xu D, Hao Q, Yang T, Lv X, Qin H, Wang Y, Jia C, Liu W, Dai X, Zeng J, Zhang H, He Z, Xia X, Cao S and Ma W (2023) Impact of “Green Revolution” gene Rht-B1b on coleoptile length of wheat. Front. Plant Sci. 14:1147019. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2023.1147019

Received: 18 January 2023; Accepted: 17 February 2023;

Published: 02 March 2023.

Edited by:

Hongwei Wang, Shandong Agricultural University, ChinaCopyright © 2023 Xu, Hao, Yang, Lv, Qin, Wang, Jia, Liu, Dai, Zeng, Zhang, He, Xia, Cao and Ma. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Shuanghe Cao, Y2Fvc2h1YW5naGVAY2Fhcy5jbg==; Wujun Ma, Vy5NYUBtdXJkb2NoLmVkdS5hdQ==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.