95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Plant Sci. , 30 September 2022

Sec. Plant Systems and Synthetic Biology

Volume 13 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2022.968780

This article is part of the Research Topic Metabolic Engineering of Valuable Compounds in Photosynthetic Organisms View all 11 articles

Ali Movahedi1†

Ali Movahedi1† Hui Wei2†

Hui Wei2† Boas Pucker3†

Boas Pucker3† Mostafa Ghaderi-Zefrehei4

Mostafa Ghaderi-Zefrehei4 Fatemeh Rasouli5,6

Fatemeh Rasouli5,6 Ali Kiani-Pouya5,6

Ali Kiani-Pouya5,6 Tingbo Jiang7

Tingbo Jiang7 Qiang Zhuge1*

Qiang Zhuge1* Liming Yang1*

Liming Yang1* Xiaohong Zhou8*

Xiaohong Zhou8*It is critical to develop plant isoprenoid production when dealing with human-demanded industries such as flavoring, aroma, pigment, pharmaceuticals, and biomass used for biofuels. The methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) and mevalonic acid (MVA) plant pathways contribute to the dynamic production of isoprenoid compounds. Still, the cross-talk between MVA and MEP in isoprenoid biosynthesis is not quite recognized. Regarding the rate-limiting steps in the MEP pathway through catalyzing 1-deoxy-D-xylulose5-phosphate synthase and 1-deoxy-D-xylulose5-phosphate reductoisomerase (DXR) and also the rate-limiting step in the MVA pathway through catalyzing 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase (HMGR), the characterization and function of HMGR from Populus trichocarpa (PtHMGR) were analyzed. The results indicated that PtHMGR overexpressors (OEs) displayed various MEP and MVA-related gene expressions compared to NT poplars. The overexpression of PtDXR upregulated MEP-related genes and downregulated MVA-related genes. The overexpression of PtDXR and PtHMGR affected the isoprenoid production involved in both MVA and MEP pathways. Here, results illustrated that the PtHMGR and PtDXR play significant roles in regulating MEP and MVA-related genes and derived isoprenoids. This study clarifies cross-talk between MVA and MEP pathways. It demonstrates the key functions of HMGR and DXR in this cross-talk, which significantly contribute to regulate isoprenoid biosynthesis in poplars.

Isoprenoids (terpenoids) present many functional and structural properties over 50,000 distinct molecules in living organisms (Thulasiram et al., 2007). Isoprenoids play vital roles in plant growth and development, as well as in membrane fluidity, photosynthesis, and respiration. They are joining with plant-pathogen and allelopathic interactions to preserve plants from pathogens and herbivores, and they are also created to draw pollinators and seed-dispersing animals. The importance of isoprenoids has been proved in rubber products, drugs, flavors, fragrances, agrochemicals, nutraceuticals, disinfectants, and pigments (Bohlmann and Keeling, 2008). A wide range of isoprenoids is involved in photosynthesis in plants, including electron transfer, quenching of excited chlorophyll triplets, light-harvesting, and energy conversion (Malkin and Niyogi, 2000). Tetrapyrrole ring derived from heme pathway with an appended isoprenoid-derived phytol chain aim chlorophylls in all reaction centers and antenna complexes to absorb light energy and transfer electrons to the reaction centers. The light-harvesting system is maintained by the other isoprenoids, which are linear or partly cyclized carotenes and their oxygenated derivatives, xanthophylls. These carotenes and xanthophylls reduce excess excitation energy through the process of light-harvesting. However, these isoprenoids are attractive in flowers and fruits (Rodriguez-Concepcion, 2010). In contrast to vertebrates synthesizing cholesterol, higher plants synthesize a complex mix of sterol lipids called phytosterols (Boutte and Grebe, 2009).

Plant isoprenoids include gibberellins (GAs), carotene, lycopene, cytokinins (CKs), strigolactones (GRs), and brassinosteroids (BRs), which are produced through methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) and mevalonic acid (MVA) pathways (van Schie et al., 2006; Xie et al., 2008; Henry et al., 2015). These pathways are involved in plant growth, development, and response to environmental stresses (Bouvier et al., 2005; Kirby and Keasling, 2009). The isopentenyl diphosphate isomerase (IDI) catalyzes the conversion of the isopentenyl diphosphate (IPP) into dimethylallyl diphosphate (DMAPP), leading to provide the basic precursors for all isoprenoid productions (Hemmerlin et al., 2012; Lu et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2019). The IPP and DMAPP are essential for regulating MEP and MVA pathway interactions (Huchelmann et al., 2014; Liao et al., 2016). The MVA pathway reactions appear in the cytoplasm, endoplasmic reticulum (ER), and peroxisomes (Cowan et al., 1997; Roberts, 2007), producing sesquiterpenoids and sterols. The 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A synthase (HMGR), a rate-limiting enzyme in the MVA pathway, catalyzes 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutary-CoA (HMG-CoA) to form MVA (Cowan et al., 1997; Roberts, 2007).

On the other hand, the MEP pathway reactions appear in the chloroplast, producing carotenoids, GAs, and diterpenoids. The 1-deoxy-D-xylulose5-phosphate synthase (DXS) and 1-deoxy-D-xylulose5-phosphate reductoisomerase (DXR) are rate-limiting enzymes in the MEP pathway that catalyze the conversion of glyceraldehyde3-phosphate (G-3-P) and pyruvate (Cordoba et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2012; Yamaguchi et al., 2018; Perreca et al., 2020). Isoprenoids like phytoalexin and volatile oils play essential roles in plant growth, development, and disease resistance (Hain et al., 1993; Ren et al., 2008). Besides an extensive range of natural functions in plants, terpenoids also consider the potential for biomedical applications. Paclitaxel is one of the most effective chemotherapy agents for cancer treatment, and artemisinin is an anti-malarial drug (Kong and Tan, 2015; Kim et al., 2016).

Previous metabolic engineering studies have proposed strategies to improve the production of specific plant metabolites (Ghirardo et al., 2014; Opitz et al., 2014). In addition, it has been proved that HMGS overexpression upregulated carotenoid and phytosterol in tomatoes (Liao et al., 2018). The HMGR has been considered as a critical factor in the metabolic engineering of terpenoids (Aharoni et al., 2005; Dueber et al., 2009), and its overexpression in ginseng (PgHMGR1) increased ginsenosides content, which is a necessary pharmaceutically active component (Kim et al., 2014). Overexpression of Salvia miltiorrhiza HMGR significantly improves diterpenoid tanshinone contents (Dai et al., 2011; Kai et al., 2011). The first generation of transgenic tomatoes exhibited a higher phytosterol content because of the overexpression of HMGR1 from Arabidopsis thaliana (AtHMGR1; Enfissi et al., 2005).

Further studies about the MEP pathway revealed that the dissemination of DXR transcript resulted in decreased pigmentation amount, while its upregulation caused the accumulation of the MEP-derived isoprenoids in plastid (Carretero-Paulet et al., 2006). The overexpression of DXR from A. thaliana caused to accumulation of the diterpene anthiolimine in Salvia sclarea hairy roots (Vaccaro et al., 2014). In another study, the overexpression of DXR from peppermint resulted in approximately 50% increased monoterpene compositions (Mahmoud and Croteau, 2001). Further studies on MVA and MEP pathways exhibited their cross-talk in metabolic intermediates through plastid membranes (Laule et al., 2003; Liao et al., 2006).

Poplars provide the raw materials for industrial and agricultural production as an economic and energy species. Its fast growth characteristics and advanced resources in artificial afforestation play a vital role in the global ecosystem (Devappa et al., 2015). This study investigates the biosynthesis of isoprenoids in poplar. The increased expression of PtHMGR in Populus trichocarpa increased the transcript levels of genes associated with MVA and MEP pathways. This work further exhibits that the overexpression of PtDXR in P. trichocarpa causes downregulating of genes related to MVA and, conversely, upregulating of genes associated with MEP. The overexpression of PtDXR also affects GA3, trans-zeatin-riboside (TZR), isopentenyl adenosine (IPA), castasterone (CS), and 6-deoxocastasterone (DCS) amounts. Taken together, PtHMGR and PtDXR genes play critical regulatory points in MEP and MVA pathways through isoprenoid productions.

The “Nanlin 895” (Populus deltoides×Populus euramericana “Nanlin895”) plants were cultured in half-strength Murashige and Skoog (1/2 MS) medium (pH 5.8) under conditions of 24°C and 74% humidity (Movahedi et al., 2015). Subsequently, NT (Transformed WT with empty vector) and transgenic poplars were cultured in 1/2 MS under 16/8 h light/dark at 24°C for 1 month (Movahedi et al., 2018).

The total RNA was extracted from P. trichocarpa leaves and processed with PrimeScript™ RT Master Mix, a kind of reverse transcriptase (TaKaRa, Japan). Forward and reverse primers (Supplementary Table 1: PtHMGR-F and PtHMGR-R) were designed, and the open reading frame (ORF) of PtHMGR was amplified via PCR. The total volume of 50 μl, including 2 μl primers (10 μM), 2.0 μl cDNA (200 ng), 5.0 μl 10 × PCR buffer (Mg2+), 4 μl dNTPs (2.5 mM), 0.5 μl rTaq polymerase (5 U; TaKaRa, Japan) was then used for the following PCR reactions: 95°C for 7 min, 35 cycles of 95°C for 1 min, 58°C for 1 min, 72°C for 1.5 min, and 72°C for 10 min. Subsequently, the product of the PtHMGR gene was ligated into the pEASY-T3 vector (TransGen Biotech, China) based on blue-white spot screening, and the PtHMGR gene was inserted into the vector pGWB9 (Song et al., 2016) using Gateway technology (Invitrogen, United States).

The National Center for Biotechnology Information database (NCBI) has been applied to download HMGR from P. trichocarpa (PtHMGR: Potri.004G208500; XM_006384809) and from other 34 species to align and analyze. The alignment has been performed using Geneious Prime Ver. 2022 software (Biomatters development team) to construct a phylogenetic tree with 1,000 bootstrap replicates.

The CDS of PtHMGR was cloned in pGWB9 vector, and the Agrobacterium tumefaciens var. EHA105, including recombinant pGWB9-PtHMGR, was used to transform “Nanlin 895” poplar leaves and petioles (Movahedi et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2017). Poplar buds were screened on differentiation MS medium supplemented with 30 μg/ml Kanamycin (Kan). Resistant buds were planted in the bud elongation MS medium containing 20 μg/ml Kan and transplanted into 1/2 MS medium, including 10 μg/ml Kan to generate resistant poplar trees (Movahedi et al., 2014). Genomic DNA has been extracted from putative transformants of one-month-old leaves grown on medium-supplemented kanamycin using TianGen kits (TianGen BioTech, China). The quality of the extracted genomic DNA (250–350 ng/μl) was determined by a BioDrop spectrophotometer (United Kingdom). PCR was then conducted using designed primers (Supplementary Table 1: CaMV35S as the forward and PtHMGR-R as the reverse), Easy Taq polymerase (TransGene Biotech), and 50 ng of extracted genomic DNA as a template to amplify about 2,000 bp. In addition, total RNA was extracted from leaves to produce cDNA, as mentioned above. These cDNAs were then applied to real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR; Supplementary Table 1: PtHMGR forward and reverse) to evaluate the PtHMGR expression in PtHMGR overexpressors (OEs) compared with NT poplars. Three independent technical repeats were performed to analyze PtHMGR expression.

PtDXR transformant seedlings were provided from Nanjing Xiaozhuang University through the key laboratory of quality and safety of agricultural products, which has been sequenced previously and confirmed (Xu et al., 2019), followed by culturing under the same conditions as PtHMGR poplars. PtDXR transformants were further confirmed through PCR confirmation for T-DNA insertion.

NT poplars were provided by transforming empty vectors into WT poplars for both PtHMGR and PtDXR transformants, followed by culturing with no medium-supplemented kanamycin to screen.

The 75-day-old PtHMGR-OEs, PtDXR-OEs, and NT poplars were selected to evaluate the phenotypic changes such as stem lengths (mm) and diameters (mm). PtHMGR-OE3 and-OE7 (Two plants) and PtDXR-OE1 and-OE3 (Two plants) were screened 45 times during 75 days to evaluate and compare with NT in the same conditions (Started on day 5th and continued randomly until the 75th day). All data were analyzed by GraphPad Prism 9, using ANOVA one way (Supplementary Table 2).

Three-month-old PtDXR-OEs, PtHMGR-OEs, and NT (grown on soil) leaves were used to extract the total RNA. The qPCR was performed to identify MVA and MEP-related gene expressions in PtDXR-OE and PtHMGR-OEs compared to NT. We used the StepOne Plus Real-time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, United States) and SYBR Green Master Mix (Roche, Germany) to carry out qRT-PCR with the PtActin gene (XM-006370951) serving as the housekeeping gene standard (Zhang et al., 2013). The following conditions were used for qPCR reactions: pre-denaturation at 95°C for 10 min, 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 15 s, and a chain extension at 60°C for 1 min. Three independent biological replicates were used with three technical repeats (Supplementary Table 1; PtHMGR and DXR forward and reverse).

The AB Qtrap6500 mass spectrometer was used in triple four-stage rod-ion hydrazine mode. The HPLC-MS/MS method was used to quantitatively analyze GA3, TZR, IPA, DCS, and CS hormones. Samples were separated using Agilent 1290 HPLC with electrospray ionization as the ion source and scanned in a multi-channel detection mode. Three-month-old leaves were used for hormone extraction. Liquid nitrogen was used to grind fresh plant samples of 0.5 g, and then a mixture of 10 ml isopropanol and hydrochloric acid was added to shake for 30 min at 4°C. Next, 20 ml of dichloromethane was added to the solution, which was shaken for 30 min at 4°C. Subsequently, the collected solution was centrifuged at 13,000× g for 20 min at 4°C, and the lower organic phase was retained. Then, the organic phase was dried under nitrogen and dissolved in 400 μl methanol containing 0.1% formic acid. Finally, the collected solution was filtered through a 0.22 μm membrane and detected using HPLC-MS/MS.

The standard solutions with variable concentrations of 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, 2, 5, 20, 50, and 200 ng/ml were prepared with methanol (0.1% formic acid) as the solvent (Supplementary Figures 5–9). During plotting of the standard curve, non-linear points can be excluded. In the liquid phase, a Poroshell 120 SB-C18 column (2.1 × 150, 2.7 m) was used at a column temperature of 30°C. The mobile phase included A: B = (methanol/0.1% formic acid): (water/0.1% formic acid). Elution gradient: 0–1 min, A = 20%; 1–9 min, A = 80%; 9–10 min, A = 80%; 10–10.1 min, A = 20%; 10.1–15 min, A = 20%. The other requirements used in this experiment included 2 μl injection volume, 15 psi air curtain gas, 4,500 v spray voltage, 65 psi atomization pressure, 70 psi auxiliary pressure, and 400°C atomization temperature.

A sample of 1 g of poplar leaves was ground and dissolved in a mixture of 10 ml of acetone-petroleum ether (1:1). Subsequently, the supernatant was filtered and collected repeatedly. The collected solution was transferred to a liquid separation funnel and layered statically. Then, the upper organic phase was extracted through a funnel containing anhydrous sodium sulfate, and the lower layer was extracted again in petroleum ether. The collected solution was evaporated to dry with rotation at 35°C, dissolved into 1 ml dichloromethane, and filtered. Finally, the solution was filtered through a 0.45-μm filter membrane and analyzed with HPLC. In liquid phase conditions, the Waters Symmetry Shield RP18 reversed-phase chromatographic column (4.6 × 250 mm × 5 μm) was used in this study with a column temperature of 30°C. The mobile phase was a mixture of methanol, acetonitrile, and dichloromethane (methanol: acetonitrile: dichloromethane = 20: 75:5). Elution gradient: 0–30 min, mobile phase = 100%, flow rate = 1.0 ml/min. The injection volume was 10 μl. In addition, the standard curves of α-carotenoid, β-carotenoid, and lycopene were formulated as described above.

The high similarity of achieved alignment, including lots of conserved amino acids (aa), similar domains, HMG-CoA-binding motifs (EMPVGYVQIP and TTEGCLVA), and NADPH-binding motifs (DAMGMNMV and VGTVGGGT; Ma et al., 2012), confirmed detected PtHMGR protein analytically (Supplementary Figure 1). A phylogenetic tree based on the HMGRs from various species supported the PtHMGR candidate identification (Supplementary Figure 2). The tblastn was then applied to reveal 2,614 bp PtHMGR on Chr04:21681480…21,684,242 with a 1,785 bp CDS. The PCR amplified 1855 bp of the PtHMGR from synthesized cDNA of P. trichocarpa confirmed the putative transgenic lines (Supplementary Figure 3A), exhibiting amplicons in PCR identification compared with NT poplar (Supplementary Figure 3B). The expression of PtHMGR through PtHMGR-OEs was significantly higher than in NT poplars (Supplementary Figure 3C), indicating successful overexpression of PtHMGR in poplar.

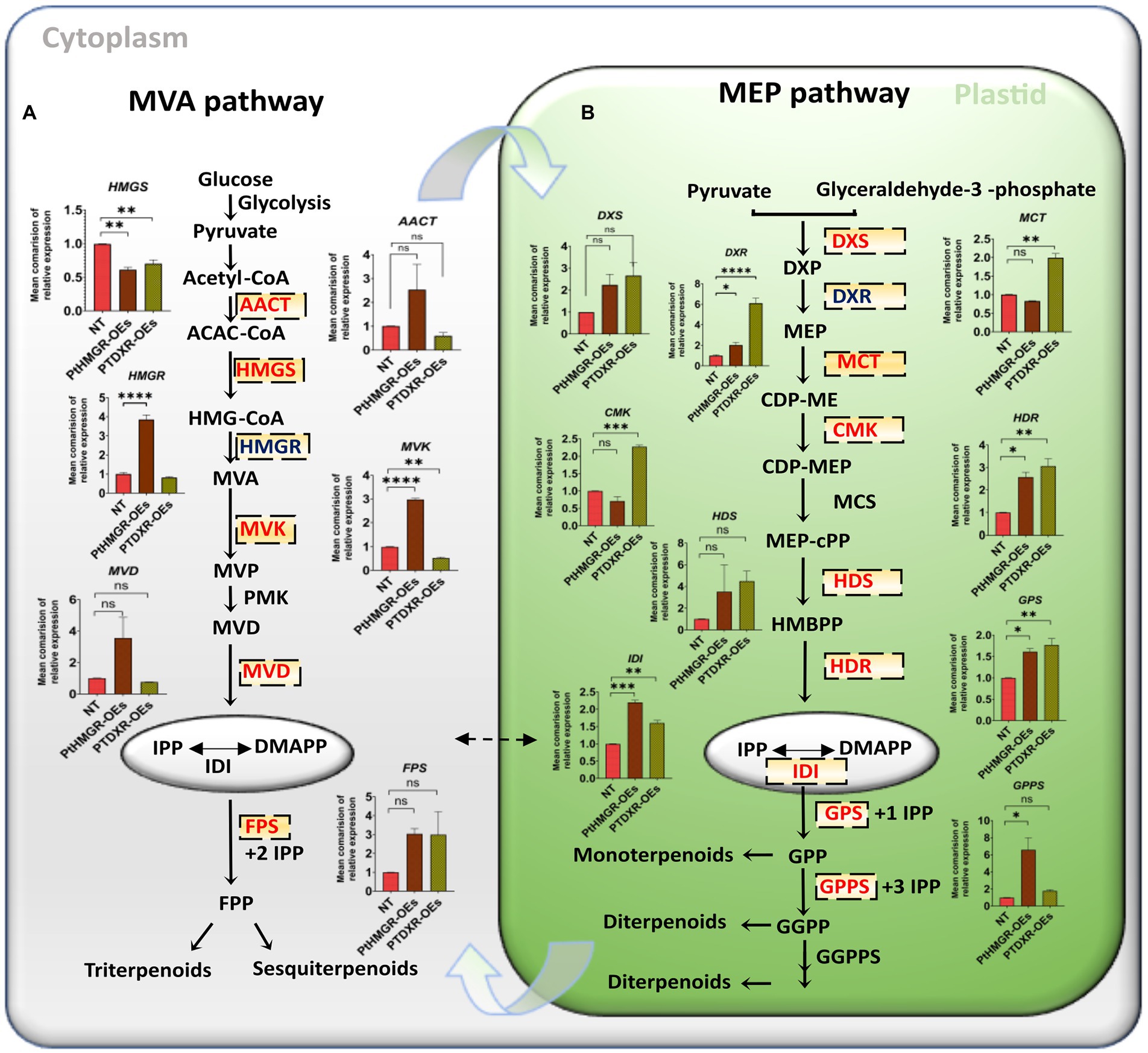

MVA-related genes such as acetoacetyl CoA thiolase (AACT), mevalonate kinase (MVK), mevalonate5-diphosphate decarboxylase (MVD), HMGR, and farnesyl diphosphate synthase (FPS), except HMGS, were significantly upregulated in PtHMGR-OEs (Figure 1A; Supplementary Figure 4A). In contrast, PtDXR overexpression caused upregulating of the FPS expression and downregulating of the AACT, HMGS, HMGR, MVD, and MVK expressions (Figure 1A; Supplementary Figure 4B). On the other hand, PtHMGR-OEs caused significantly upregulate the MEP-related genes such as DXS, DXR, 1-hydroxy-2-methyl-2-(E)-butenyl-4-diphosphate synthase (HDS), 1-hydroxy-2-methyl-2-(E)-butenyl-4-diphosphate reductase (HDR), IDI, geranyl pyrophosphate synthase (GPS), and geranyl diphosphate synthase (GPPS; Figure 1B; Supplementary Figure 4C). In contrast, PtHMGR-OEs caused downregulating 2-C-methyl-d-erythritol4-phosphate cytidylyltransferase (MCT) and 4-diphosphocytidyl-2-C-methyl-D-erythritol kinase (CMK). Moreover, PtDXR overexpression caused upregulating all MEP-related genes (Figure 1B; Supplementary Figure 4D).

Figure 1. MVA and MEP-related gene expression analyses in PtHMGR-and PtDXR-OEs poplars. (A) Mean comparison of relative expressions of MVA related genes affected by PtHMGR-and PtDXR-OEs. (B) Mean comparison of relative expressions of MEP related genes affected by PtHMGR-and PtDXR-OEs; PtActin was used as an internal reference in all repeats; “ns” means not significant, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001; Three independent replications were performed in each experiment.

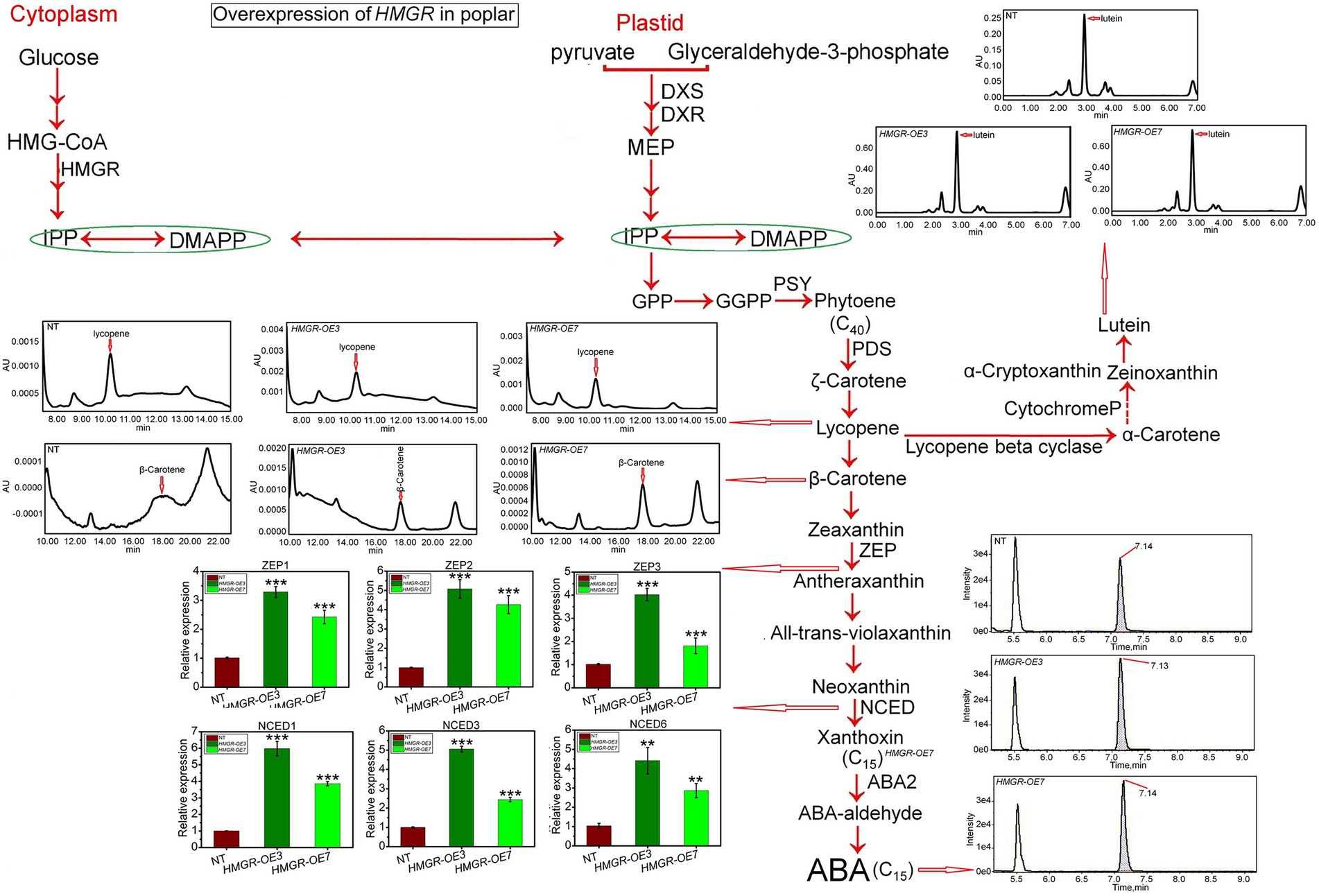

β-carotene is a carotenoid synthesis that has been broadly used in the industrial composition of pharmaceuticals and as food colorants, animal supplies additives, and nutraceuticals. In addition, lycopene is a precursor of β-carotene, referring to C40 terpenoids, and is broadly found in various plants, particularly vegetables and fruits. It has been shown that MVA and MEP pathways directly influence the biosynthesis production of lycopene (Wei et al., 2018; Kim et al., 2019). While one study showed that β-carotene and lutein are synthesized using intermediates from the MEP pathway (Wille et al., 2004), the other study revealed that both MVA and MEP pathways produce isoprenoids such as β-carotene and lutein (Opitz et al., 2014). HPLC-MS/MS has been applied to analyze the MVA and MEP derivatives to quantity. Our analyses revealed a slight increase in the average lycopene content through PtHMGR-OE3 and-OE7 transformants compared to NT (0.0013 AU) with 0.0016 AU (Figure 2). The overexpression of HMGR caused significantly enhanced the synthesis of β-carotene with an average of 0.00065 AU compared with NT by-0.00002 AU (Figure 2). Results also exhibited a significant increase in lutein content through PtHMGR-OE3 and-OE7 with an average of 0.7 AU compared with NT with 0.25 AU (Figure 2). Moreover, the abscisic acid (ABA) content has been influenced by overexpression of HMGR with a considerable increase with an average of 3.7e4 compared with NT with 2.7e4 (Figure 2). The ABA-related gene expressions were also calculated, and results revealed that the overexpression of HMGR significantly upregulated the zeaxanthin epoxidase (ZEP) 1, −2, and −3 genes with averages of ~2.8, ~4.6, and ~ 2.9, respectively in comparing with NT poplars (Figure 2). These results also indicated meaningful upregulation through 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase (NCED) 1, −3, and −6 genes with averages of ~4.16, ~3.79, and ~3.4 compared with NT with an average of ~1 (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Evaluation of the effect of the overexpression of PtHMGR on isoprenoid production and ABA. The qRT-PCR analyses of the expression levels of ABA synthesis-related genes and HPLC-MS/MS analyses of the contents of ABA, β-carotene, lycopene, and lutein in PtHMGR-OEs. The expression levels of the ABA synthesis-related ZEP and NCED genes family are shown. Bars represent mean ± SD (n = 3); Stars reveal significant differences, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001; Experiments were performed in triplicates.

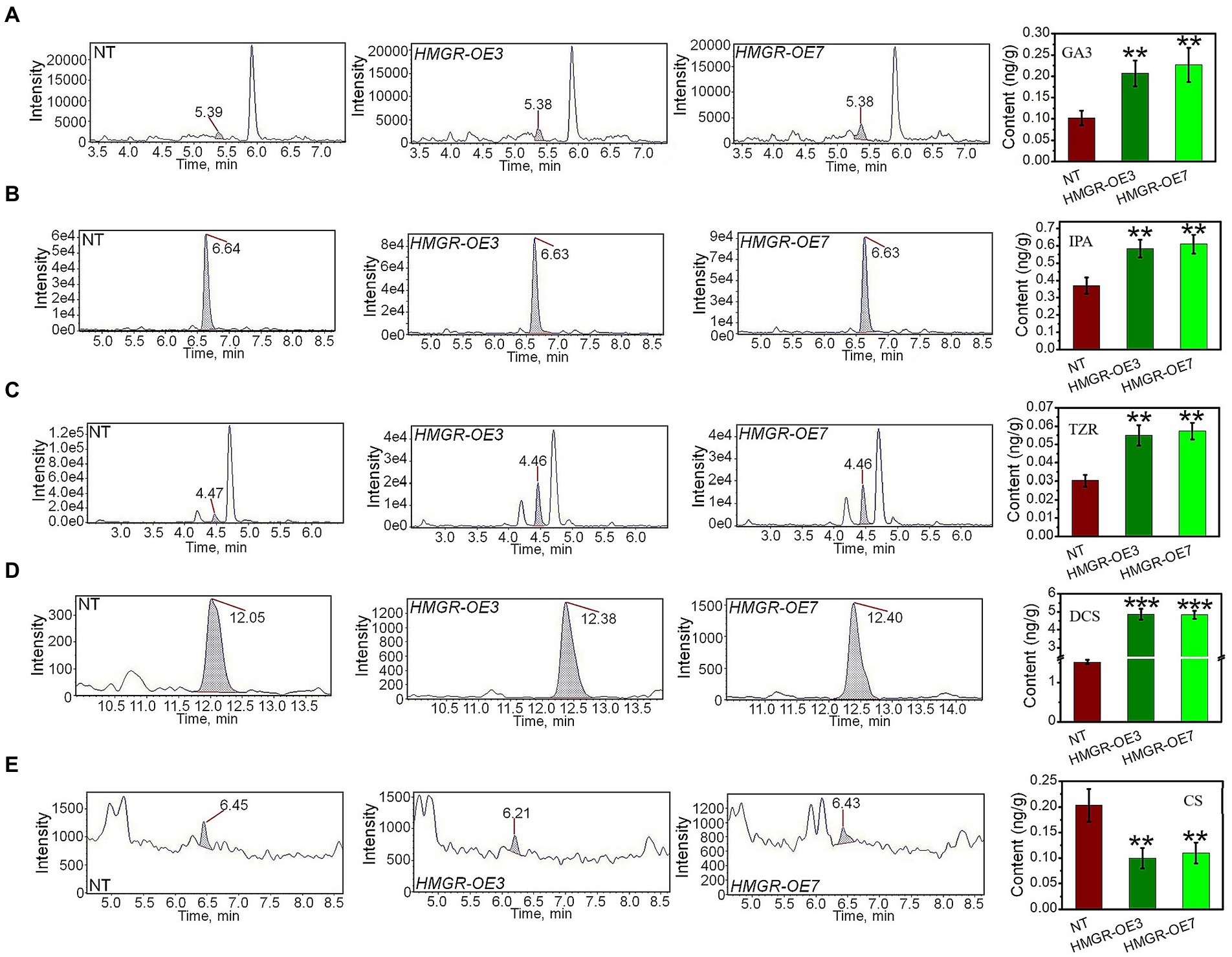

In addition, the total level of GA3, a downstream product of MEP, increased to 0.2–0.35 ng/g in PtHMGR-OE lines, compared to 0.08–0.1 ng/g in NT poplars (Figure 3A). Also, the IPA content in PtHMGR-OEs (0.32–0.41 ng/g) is dominantly higher than that in NT (0.54–0.66 ng/g; Figure 3B). Among MVA-derived isoprenoids, the results of HPLC-MS/MS exhibited significant enhancements in the TZR content through PtHMGR-OEs with an average of 0.56 ng/g than NT with an average of 0.3 ng/g (Figure 3C). Surprisingly, the expression of HMGR caused a 3-fold increase in DCS content with an average of 5 ng/g compared with NT of about 1.5 ng/g (Figure 3D). However, PtHMGR-OEs negatively affected the CS content with a significant decrease compared to NT poplars (Figure 3E).

Figure 3. Analyzing the effect of the overexpression of PtHMGR on MVA and MEP-derivatives. HPLC-MS/MS analyses of the contents of GA3 (A), IPA (B), TZR (C), DCS (D), and CS (E) in PtHMGR-OEs compared to NT poplars. Bars represent mean ± SD (n = 3); Stars reveal significant differences, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001; Experiments were performed in triplicates.

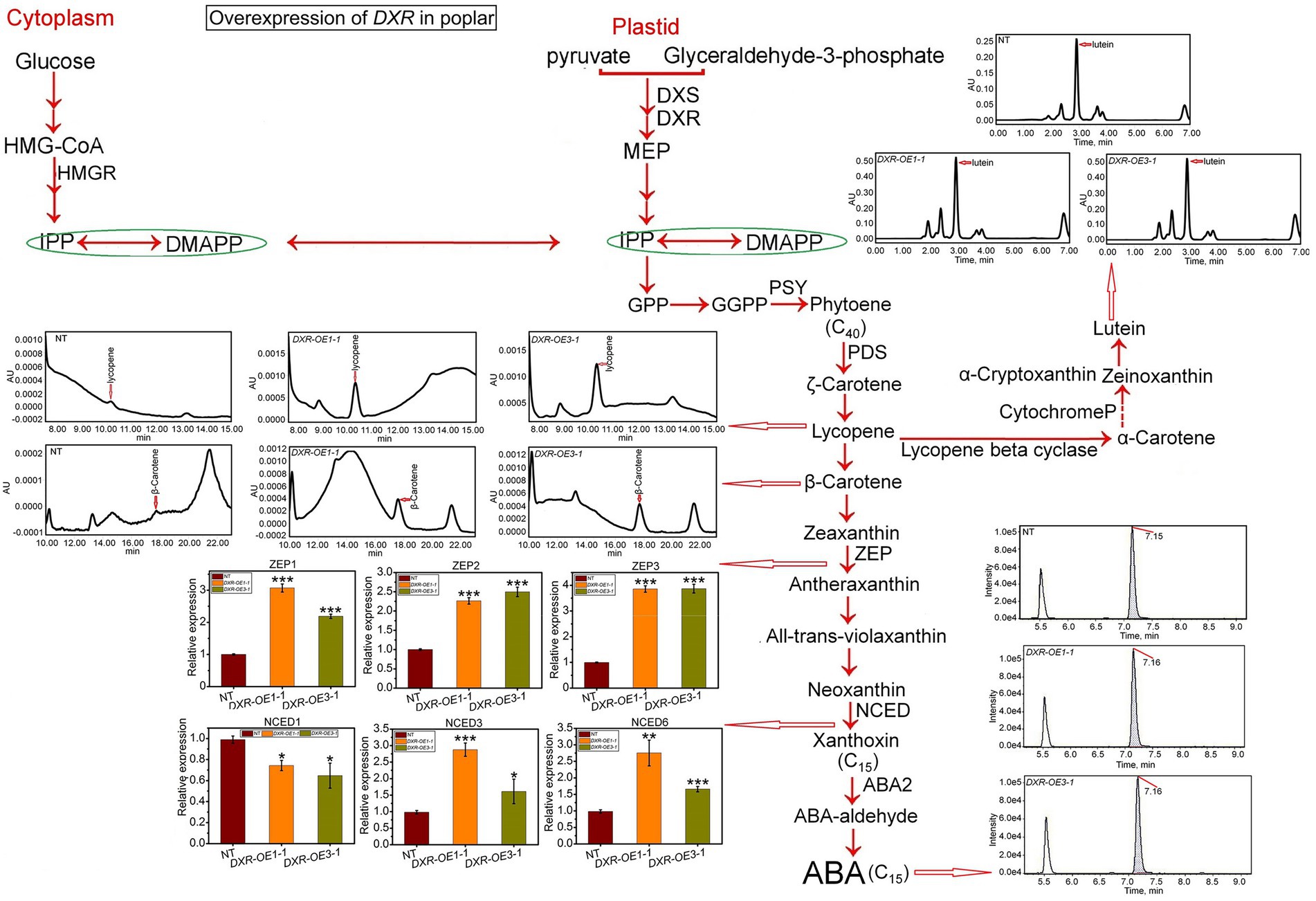

PtDXR-OEs exhibited a significant increase in lycopene, β-carotene, and lutein contents affected by overexpression of PtDXR with the averages of 0.00095, 0.00037, and 0.5 AU compared to NT poplars (Figure 4). Moreover, the ABA content also has been affected by the overexpression of PtDXR and considerably increased more than NT poplars (Figure 4). The expression of the ABA-related gene also has been influenced by the overexpression of PtDXR and upregulated NCED genes, except for NCED1, which has been downregulated (Figure 4). These analyses further exhibited the positive effect of the overexpression of PtDXR on a significant increase in the expression of ZEP1, 2, and 3 (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Assessment of the impact of PtDXR overexpression on isoprenoid and ABA biosynthesis. The qRT-PCR analyses of the expression levels of ABA synthesis-related genes and HPLC-MS/MS analyses of the contents of ABA, β-carotene, lycopene, and lutein in PtDXR-OEs. The expression levels of the ABA synthesis-related ZEP and NCED genes family are indicated. Bars represent mean ± SD (n = 3); Stars reveal significant differences, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001; Experiments were performed in triplicates.

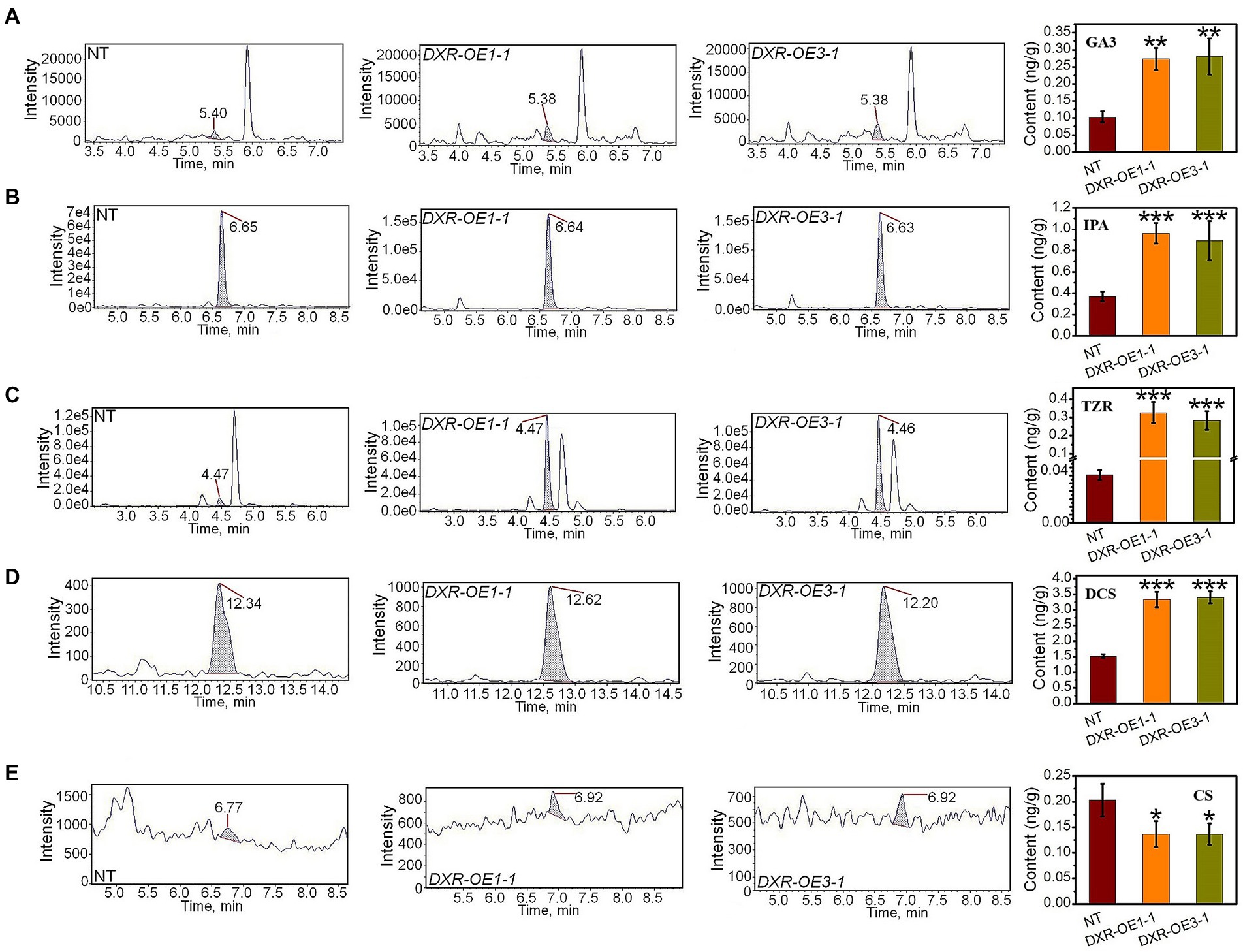

The further analysis of the production of GA3 exhibited a significant increase affected by the overexpression of PtDXR with an average of 0.27 ng/g compared to NT poplars (Figure 5A). Also, the overexpression of PtDXR caused to increase in IPA production significantly (Figure 5B). A considerable increase in TZR content also was observed, influenced by the overexpression of PtDXR with an average of 0.3 ng/g compared to NT with only 0.04 ng/g (Figure 5C). In addition, the overexpression of PtDXR caused to increase in the DCS production significantly, but adversely the CS was meaningfully decreased (Figures 5D,E).

Figure 5. Analyzing the effect of the overexpression of PtDXR on MVA and MEP-derivatives. HPLC-MS/MS analyses of the contents of GA3 (A), IPA (B), TZR (C), DCS (D), and CS (E) in PtDXR-OEs compared to NT poplars.

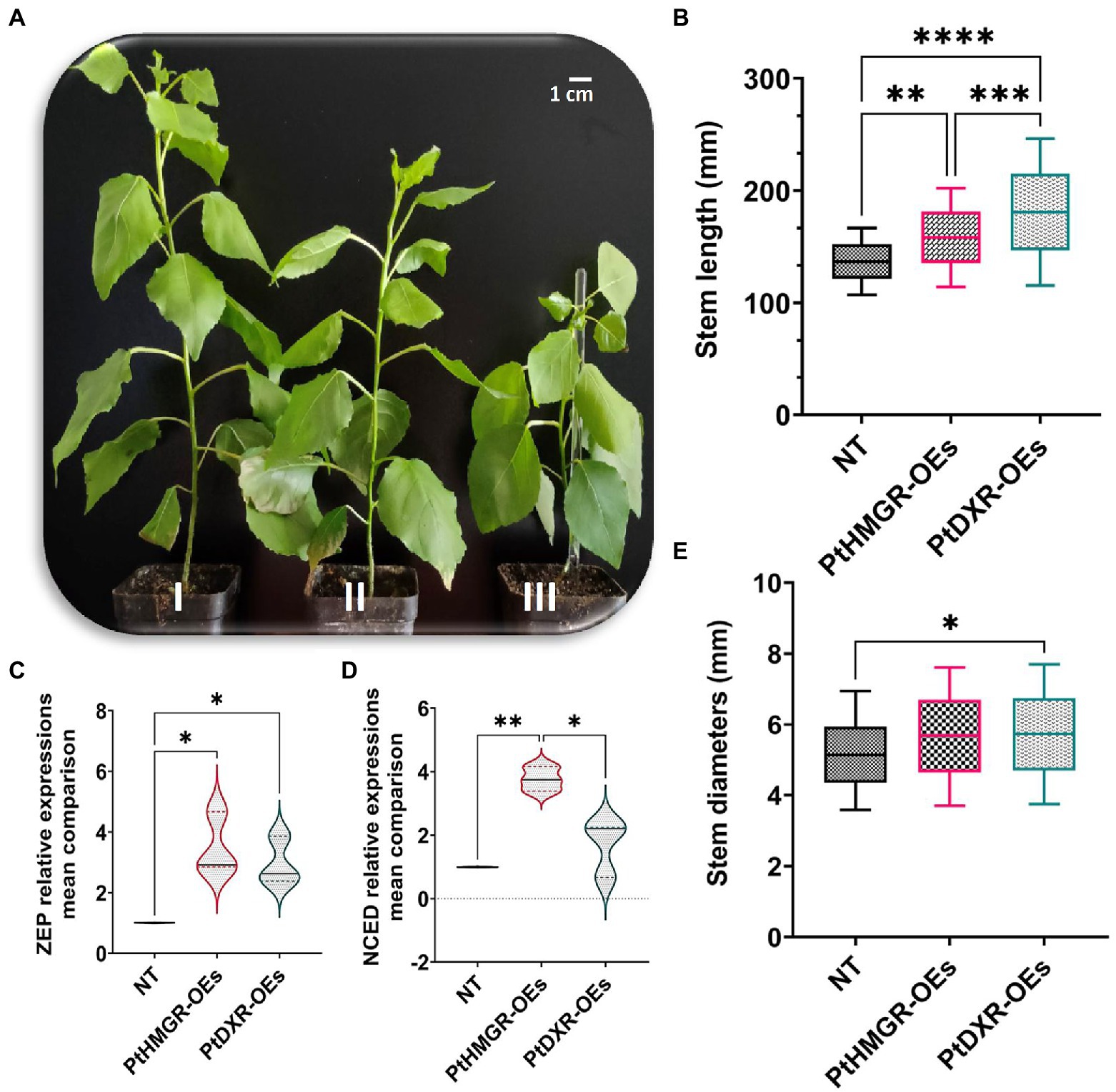

To improve the effect of overexpression of PtHMGR and PtDXR on phenotypic changes, the stem length and stem diameter have been evaluated. Regarding the results, the overexpression of PtHMGR and PtDXR revealed positive effects on increasing the isoprenoid contents. More increase in cytokinins TZR (~0.290 ng/g) and IPA (~0.940 ng/g) affected by the overexpression of PtDXR in comparing with TZR (~0.054 ng/g) and IPA (~0.580 ng/g) affected by the overexpression of PtHMGR, resulting in significantly more developments in the stem length through PtDXR-OEs compared with PtHMGR-OEs (Figures 6A,B). Slightly more stem diameters through PtDXR-OEs compared with PtHMGR-OEs, may be resulted from increasing the expression of ABA-related genes ZEP (~3.40) and NCED (~3.93) in PtHMGR-OEs compared with ZEP (~2.70) and NCED (~1.57) in PtDXR-OEs (Figures 6C–E).

Figure 6. Phenotypic changes analyses resulted from the overexpression of PtHMGR and PtDXR effects on MVA and MEP pathways. (A, I), The PtDXR transgenic revealed a higher stem length than PtHMGR-OEs and NT poplars. (A, II), The PtHMGR transgenic presents more stem development than NT poplar. (A, III), NT poplar was used as a control; Scale bar represents 1 cm. (B) The Box and Whisker mean comparison plot of stem lengths revealed significantly higher lengths of PtDXR-OEs than NT poplars compared with PtHMGR-OEs. PtHMGR transgenics also revealed significantly higher lengths than NT poplars. (C,D) The Violin mean comparison plots of ZEP and NCED relative expressions between PtHMGR-and PtDXR-OEs compared with NT poplars. (E) The Box and Whisker mean comparison plot of stem diameters revealed slightly more diameters between PtDXR-OEs and NT poplars. Stars reveal significant differences, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

Several studies report that the activity of HMGR is regulated by isoprenoid outcomes when stigmasterol and cholesterol reduce the HMGR activity by 35% (Russell and Davidson, 1982). The other study revealed a downregulation of the activity of HMGR in pea by approximately 40% among those treated with ABA, while zeatin and gibberellin improved the activity of HMGR (Russell and Davidson, 1982). Moreover, the MEP pathway is the primary precursor for required plastid isoprenoids (Maurey et al., 1986; Wright et al., 2014). It has been demonstrated that volatile compounds produced by the MEP pathway are involved in protecting plants against biotic and abiotic stresses (Gershenzon and Dudareva, 2007). Additionally, promising metabolite compounds have been developed in the mint plant by modifying the expression of DXR (Mahmoud and Croteau, 2002).

Overexpression of DXR in Arabidopsis results in accumulations of isoprenoids such as tocopherols, carotenoids, and chlorophylls (Carretero-Paulet et al., 2006). Overexpression of DXR has also been proven to improve diterpene content in transgenic bacteria (Morrone et al., 2010). Biotic tolerance, which is important in providing pharmaceutical terpenoids by expanding the number of enzymes included in biosynthetic pathways (Kang et al., 2009; Lu et al., 2016), caused improved DXR expression followed by triptophenolide content in Tripterygium wilfordii cell culture suspension (Tong et al., 2015).

It has been shown that the overexpression of BjHMGS1 (MVA-related gene) affected the expressions of MEP-related genes and slightly increased the transcript levels of DXS and DXR in transgenic tomatoes (Liao et al., 2018). In this study, PtHMGR-OEs exhibited the upregulation of the MEP-related genes DXS, DXR, HDS, and HDR and the downregulation of MCT and CMK. Like BjHMGS1 overexpression in tomatoes that demonstrated a significantly upregulated of the MEP-related genes GPS and GPPS (Liao et al., 2018), we also indicated that the overexpression of PtHMGR enhanced the GPS, and GPPS expressions, resulting in stimulating the crosstalk between IPP and DMAPP, which increased the biosynthesis of plastidial C15 and C20 isoprenoid precursors. Moreover, it has been shown that the overexpression of HMGR in Ganoderma lucidum caused to upregulate MVA related genes FPS, squalene synthase (SQS), or lanosterol synthase (LS), leading to develop the contents of ganoderic acid and intermediates, including squalene and lanosterol (Xu et al., 2012). Like the effect of overexpression of BjHMGS1 in tomatoes, which significantly increased transcript levels of FPS, SQS, squalene epoxidase (SQE), and cycloartenol synthase (CAS; Liao et al., 2018), this study also exhibited that the overexpression of PtHMGR caused to upregulate the MVA related genes AACT, MVK, FPS, MVD, and except HMGS. These results proved that the MVA-related genes contribute to the biosynthesis of sesquiterpenes.

Overexpression of MEP-related gene TwDXR in Tripterygium wilfordii promoted the expressions of MVA-related genes TwHMGS, TwHMGR, TwFPS, and even MEP-related gene TwGPPS but demoted the expression of TwDXS (Zhang et al., 2018). The other study also reported that the overexpression of MEP-related gene NtDXR1 in tobacco upregulated the transcript levels of eight MEP-related genes, indicating that the overexpression of NtDXR1 led to an improved expression of MEP-related genes (Zhang et al., 2015). In A. thaliana, the overexpression of DXR revealed no influence on regulating DXS gene expression or enzyme accumulation, although overexpression of DXR promotes MEP-derived isoprenoids such as carotenoids, chlorophylls, and taxadiene (Carretero-Paulet et al., 2006). Overexpression of potato DXS in A. thaliana led to upregulate GGPPS and phytoene synthase (PSY; Henriquez et al., 2016). In this study, the overexpression of PtDXR upregulated the MEP-related genes. Controversy, the PtDXR-OEs revealed significant downregulation of MVA-related genes. This study indicated that PtHMGR and PtDXR have important influences on MEP and MVA-related gene expression.

HMGR is a rate-limiting enzyme in the MVA pathway of plants and plays a critical role in controlling the flow of carbon within this metabolic pathway. The upregulation of HMGR significantly increases isoprenoid levels in plants. The overexpression of HMGR has been reported in several plants caused to promote the isoprenoid levels significantly. The heterologous expression of Hevea brasiliensis HMGR1 in tobacco increased the sterol content and accumulated intermediate metabolites (Schaller et al., 1995). In addition, the overexpression of A. thaliana HMGR in Lavandula latifolia increased the levels of sterols in the MVA and MEP-derived monoterpenes and sesquiterpenes (Munoz-Bertomeu et al., 2007). In addition, the overexpression of Salvia miltiorrhiza SmHMGR in hairy roots increased the MEP-derived diterpene tanshinone (Kai et al., 2011). In this study, ABA synthesis-related genes (NCED1, NCED3, NCED6, ZEP1, ZEP2, and ZEP3) and the contents of GA3 and carotenoids were upregulated in PtHMGR-OEs. These findings suggest that the overexpression of HMGR may indirectly affect the biosynthesis of MEP-derived isoprenoids, including GA3 and carotenoids. The accumulation of MVA-derived isoprenoids, including TZR, IPA, and DCS, was significantly elevated in PtHMGR-OEs, indicating that overexpression of PtHMGR directly influences the biosynthesis of MVA-related isoprenoids.

DXR is the rate-limiting enzyme in the MEP pathway and is an essential regulatory step in the cytoplasmic metabolism of isoprenoid compounds (Aharoni et al., 2005). It has been shown that the overexpression of DXR in Mentha piperita promotes the synthesis of monoterpenes in the oil glands and increases the production of essential oil yield by 50% (Mahmoud and Croteau, 2001). Another study exhibited that overexpression of DXR from Synechocystis sp. strain PCC6803 in tobacco resulted in increasing the β-carotene, chlorophyll, antheraxanthin, and lutein (Hasunuma et al., 2008). In addition, it has been shown that dxr mutants of A. thaliana revealed a lack of GAs, ABA, and photosynthetic pigments (REF57; Xing et al., 2010) and showed pale sepals and yellow inflorescences (Xing et al., 2010). This study exhibits that the overexpression of PtDXR positively affects the accumulation of GA3 and carotenoids, besides upregulation of MEP-related genes DXS, DXR, IDI, HDS, HDR, MCT, CMK, GPS, and GPPS.

Although the substrates of MVA and MEP pathways differ, there are common intermediates, like IPP and DMAPP (Figure 6). Blocking only the MVA or the MEP pathway, respectively, does not entirely prevent the biosynthesis of terpenes in the cytoplasm or plastids, indicating that MVA and MEP pathway products can be transported and/or move between cell compartments (Aharoni et al., 2003, 2004; Gutensohn et al., 2013). For example, it has been shown that the transferring of IPP from the chloroplast to the cytoplasm was observed through 13C labeling (Ma et al., 2017). In addition, segregation between the MVA and MEP pathways is limited and might exchange some metabolites over the plastid membrane (Laule et al., 2003). Some studies have applied the clustered, regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR) technology to reconstruct the lycopene synthesis pathway and control the flow of carbon in the MEP and MVA pathways (Kim et al., 2016). Results showed that the expressions of MVA-related genes were reduced by 81.6%, but the lycopene yield was significantly increased. By analyzing gene expression levels and metabolic outcomes in PtHMGR-OEs and PtDXR-OEs, we discovered a correlation between MVA and MEP-related genes among the derived products, which are not restricted to cross-talk between IPP and DMAPP (Figure 6).

The overexpression of PtDXR affected the transcript levels of MEP-related genes and the contents of MEP-derived isoprenoids, including GA3 and carotenoids. The weakened expressions of MVA-related genes reduce the yields of MVA-derived isoprenoids (including CS) but increase the TZR, IPA, and DCS contents. This study hypothesizes that IPP and DMAPP produced by the MEP pathway pass the cytoplasm to compensate for the lack of IPP and DMAPP of the MVA pathway to synthesize MVA-derived products.

The analysis of the overexpression of PtHMGR in PtHMGR-OEs exhibited higher transcript levels of MVA-related genes AACT, MVK, FPS, MVD, and except HMGS and MEP-related genes DXS, DXR, HDS, HDS, HDR, IDI, GPS, and GPPS than NT poplars, and proved that the overexpression of MVA related gene PtHMGR involves in regulating of both MEP and MVA pathways. These results demonstrate that cytosolic HMGR overexpression expanded plastidial GPP-and GGPP-derived products, such as GA3 and carotenoids, through cross-talk between MVA and MEP pathways. These results illustrate that regulation in the expression of MEP and MVA-related genes affects the MVA and MEP-derived isoprenoids.

The advanced insights in regulating MVA and MEP pathways in poplars improve the knowledge about these pathways in Arabidopsis, tomato, and rice. Altogether, these results discover that manipulating PtDXR and PtHMGR is a novel strategy to control poplar isoprenoids.

ABA and GA3 have been proved that perform essential functions in cell division, shoot growth, and flower induction (Xing et al., 2016). It has also been shown that the cytokinin TZR, a variety of phytohormones, performs important functions in the development and growth processes in shoots (Sakakibara, 2006; Abul et al., 2010). This study proved that the existing cross-talk between MVA and MEP pathways would be impacted positively by the overexpression of PtHMGR and PtDXR, leading to enhanced plant growth and development.

Isoprenoid compounds, which have a variety of structures and properties, play a critical role in the survival and growth of plants. In this study, PtHMGR showed positive effects on the accumulation of MVA-derived isoprenoids and MEP-derived substances, such as ABA, GA3, carotenoids, and GRs, which are essential hormones for controlling growth and stress responses. PtDXR also exhibited an association with regulating MVA and MEP-related genes and derived isoprenoids.

The data presented in the study are deposited in NCBI (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/XM_006384809.2/) repository, accession number XM_006384809.2. The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material.

AM and HW conceived, planned, and coordinated the project, performed data analysis, wrote the draft, and finalized the manuscript. AM supervised this project. BP validated and contributed to data analysis and curation, revised and finalized the manuscript. MG-Z, FR, AK-P, and TJ reviewed and edited the manuscript. QZ, LY, and XZ coordinated, contributed to data curation, finalized, and funded this research. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (nos. 32001326 and 31971682), the Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (nos. LZ19C160001 and LQ21C160003), the National Key Program on Transgenic Research (2018ZX08020002), and the Talent Research Foundation of Zhejiang A&F University (no. 2019FR055).

The authors declare that this research was conducted without any commercial or financial relationships construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2022.968780/full#supplementary-material

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE 1 | Amino acid sequences alignment of PtHMGR protein and other known HMGR proteins. The high similarities between Populus species and the other species are exhibited. The name of species and also their accession numbers are presented. The HMG-CoA and NADPH binding domains are indicated in red rectangular.

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE 2 | Construction of a phylogenetic tree based on the HMGR sequences of various species. HMGR has been isolated from 35 species via blast on NCBI and aligned, followed by a phylogenetic tree. Results reveal a highly conserved HMGR through all the species. The gray rectangular shows similar HMGR1 via Populus species located on one root, followed by a red dashed rectangle to show the organisms and accession numbers. The names of organisms and corresponding accession numbers are presented.

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE 3 | Confirming of transformation of PtHMGR-OEs. (A) Schematic of constructed cassette transformed into the PtHMGR transgenic poplars. (B) PCR identification of PtHMGR in PtHMGR-OEs and NT poplars. Lane M: 15K molecular mass marker (TransGen, China); lane 1: genome DNA from NT as negative control; lanes 2–9: genome DNA from PtHMGR-OE lines. (C) qRT-PCR identifies the transcript levels of PtHMGR in PtHMGR-OEs and NT poplars. Three independent experiments were performed; Stars reveal significant differences, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE 4 | MEP and MVA-related genes analyses in PtHMGR- and PtDXR-OEs poplars. (A) MVA-related genes AACT, HMGS, HMGR, MVK, MVD, and FPS are affected by the overexpression of PtHMGR. (B) MVA-related genes AACT, HMGS, HMGR, MVK, MVD, and FPS are affected by the overexpression of PtDXR. (C) MEP-related genes DXS, MCT, CMK, HDS, HDR, IDI, GPS, GPPS, and DXR are affected by the overexpression of PtHMGR. (D) MEP-related genes DXS, DXR, MCT, CMK, HDS, HDR, IDI, GPS, and GPPS are affected by the overexpression of PtHMGR. PtActin was used as an internal reference in all repeats; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001; Three independent replications were performed in this experiment.

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE 5 | Chromatogram analyses of GA3 standards via HPLC-MS/MS. The chromatogram of standard GA3 at (A) 0.1, (B) 0.2, (C) 0.5, (D) 2, (E) 5, (F) 20, (G) 50, and (H) 200 ng/ml concentrations. (I) Equations for the GA3 standard curves.

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE 6 | Chromatogram analyses of TZR standards via HPLC-MS/MS. The chromatogram of standard TZR at (A) 0.1, (B) 0.2, (C) 0.5, (D) 2, (E) 5, (F) 20, (G) 50, and (H) 200 ng/ml concentrations. (I) Equations for the TZR standard curves.

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE 7 | Chromatogram analyses of IPA standards via HPLC-MS/MS. The chromatogram of standard IPA at (A) 0.2, (B) 0.5, (C) 2, (D) 5, (E) 20, (F) 50, and (G) 200 ng/ml concentrations. (H) Equations for the IPA standard curves.

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE 8 | Chromatogram analyses of DCS standards via HPLC-MS/MS. The chromatogram of standard DCS at (A) 0.5, (B) 2, (C) 10, (D) 20, and (E) 50 ng/ml concentrations. (F) Equations for the DCS standard curves.

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE 9 | Chromatogram analyses of CS standards via HPLC-MS/MS. The chromatogram of standard CS at (A) 0.5, (B) 5, (C) 10, (D) 20, and (E) 50 ng/ml concentrations. (F) Equations for the CS standard curves.

MEP, Methylerythritol phosphate; MVA, Mevalonic acid; DXR, 1-deoxy-D-xylulose5-phosphate reductoisomerase; HGMR, 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase; GAs, Gibberellins; CKs, Cytokinins; GRs, Strigolactones; BRs, Brassinosteroids; IDI, Isopentenyl diphosphate isomerase; IPP, Isopentenyl diphosphate; DMAPP, Dimethylallyl diphosphate; HMG-CoA, 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutary-CoA; DXS, 1-deoxy-D-xylulose5-phosphate synthase; G-3-P, Glyceraldehyde3-phosphate.

Abul, Y., Menendez, V., Gomez-Campo, C., Revilla, M. A., Lafont, F., and Fernandez, H. (2010). Occurrence of plant growth regulators in Psilotum nudum. J. Plant Physiol. 167, 1211–1213. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2010.03.015

Aharoni, A., Giri, A. P., Deuerlein, S., Griepink, F., Kogel, W. J., Verstappen, F. W., et al. (2003). Terpenoid metabolism in wild-type and transgenic Arabidopsis plants. Plant Cell 15, 2866–2884. doi: 10.1105/tpc.016253

Aharoni, A., Giri, A. P., Verstappen, F. W., Bertea, C. M., Sevenier, R., Sun, Z., et al. (2004). Gain and loss of fruit flavor compounds produced by wild and cultivated strawberry species. Plant Cell 16, 3110–3131. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.023895

Aharoni, A., Jongsma, M. A., and Bouwmeester, H. J. (2005). Volatile science? Metabolic engineering of terpenoids in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 10, 594–602. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2005.10.005

Bohlmann, J., and Keeling, C. I. (2008). Terpenoid biomaterials. Plant J. 54, 656–669. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03449.x

Boutte, Y., and Grebe, M. (2009). Cellular processes relying on sterol function in plants. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 12, 705–713. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2009.09.013

Bouvier, F., Rahier, A., and Camara, B. (2005). Biogenesis, molecular regulation and function of plant isoprenoids. Prog. Lipid Res. 44, 357–429. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2005.09.003

Carretero-Paulet, L., Cairo, A., Botella-Pavia, P., Besumbes, O., Campos, N., Boronat, A., et al. (2006). Enhanced flux through the methylerythritol 4-phosphate pathway in Arabidopsis plants overexpressing deoxyxylulose 5-phosphate reductoisomerase. Plant Mol. Biol. 62, 683–695. doi: 10.1007/s11103-006-9051-9

Cordoba, E., Salmi, M., and Leon, P. (2009). Unravelling the regulatory mechanisms that modulate the MEP pathway in higher plants. J. Exp. Bot. 60, 2933–2943. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erp190

Cowan, A. K., Moore-Gordon, C. S., Bertling, I., and Wolstenholme, B. N. (1997). Metabolic control of avocado fruit growth (Isoprenoid growth regulators and the reaction catalyzed by 3-Hydroxy-3-Methylglutaryl coenzyme A Reductase). Plant Physiol. 114, 511–518. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.2.511

Dai, Z., Cui, G., Zhou, S. F., Zhang, X., and Huang, L. (2011). Cloning and characterization of a novel 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase gene from salvia miltiorrhiza involved in diterpenoid tanshinone accumulation. J. Plant Physiol. 168, 148–157. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2010.06.008

Devappa, R. K., and Rakshit, S. K., and and Dekker, R. F. (2015). Forest biorefinery: potential of poplar phytochemicals as value-added co-products. Biotechnol. Adv., 33, 681–716. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2015.02.012

Dueber, J. E., Wu, G. C., Malmirchegini, G. R., Moon, T. S., Petzold, C. J., Ullal, A. V., et al. (2009). Synthetic protein scaffolds provide modular control over metabolic flux. Nat. Biotechnol. 27, 753–759. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1557

Enfissi, E. M., Fraser, P. D., Lois, L. M., Boronat, A., Schuch, W., and Bramley, P. M. (2005). Metabolic engineering of the mevalonate and non-mevalonate isopentenyl diphosphate-forming pathways for the production of health-promoting isoprenoids in tomato. Plant Biotechnol. J. 3, 17–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2004.00091.x

Gershenzon, J., and Dudareva, N. (2007). The function of terpene natural products in the natural world. Nat. Chem. Biol. 3, 408–414. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2007.5

Ghirardo, A., Wright, L. P., Bi, Z., Rosenkranz, M., Pulido, P., Rodriguez-Concepcion, M., et al. (2014). Metabolic flux analysis of plastidic isoprenoid biosynthesis in poplar leaves emitting and nonemitting isoprene. Plant Physiol. 165, 37–51. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.236018

Gutensohn, M., Orlova, I., Nguyen, T. T., Davidovich-Rikanati, R., Ferruzzi, M. G., Sitrit, Y., et al. (2013). Cytosolic monoterpene biosynthesis is supported by plastid-generated geranyl diphosphate substrate in transgenic tomato fruits. Plant J. 75, 351–363. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12212

Hain, R., Reif, H. J., Krause, E., Langebartels, R., Kindl, H., Vornam, B., et al. (1993). Disease resistance results from foreign phytoalexin expression in a novel plant. Nature 361, 153–156. doi: 10.1038/361153a0

Hasunuma, T., Takeno, S., Hayashi, S., Sendai, M., Bamba, T., Yoshimura, S., et al. (2008). Overexpression of 1-Deoxy-D-xylulose-5-phosphate reductoisomerase gene in chloroplast contributes to increment of isoprenoid production. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 105, 518–526. doi: 10.1263/jbb.105.518

Hemmerlin, A., and Harwood, J. L., and and Bach, T. J. (2012). A raison d'être for two distinct pathways in the early steps of plant isoprenoid biosynthesis? Prog. Lipid Res., 51, 95–148. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2011.12.001

Henriquez, M. A., Soliman, A., Li, G., Hannoufa, A., Ayele, B. T., and Daayf, F. (2016). Molecular cloning, functional characterization and expression of potato (Solanum tuberosum) 1-deoxy-d-xylulose 5-phosphate synthase 1 (StDXS1) in response to Phytophthora infestans. Plant Sci. 243, 71–83. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2015.12.001

Henry, L. K., Gutensohn, M., Thomas, S. T., Noel, J. P., and Dudareva, N. (2015). Orthologs of the archaeal isopentenyl phosphate kinase regulate terpenoid production in plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 112, 10050–10055. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1504798112

Huchelmann, A., Gastaldo, C., Veinante, M., Zeng, Y., Heintz, D., Tritsch, D., et al. (2014). S-carvone suppresses cellulase-induced capsidiol production in Nicotiana tabacum by interfering with protein isoprenylation. Plant Physiol. 164, 935–950. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.232546

Kai, G., Xu, H., Zhou, C., Liao, P., Xiao, J., Luo, X., et al. (2011). Metabolic engineering tanshinone biosynthetic pathway in salvia miltiorrhiza hairy root cultures. Metab. Eng. 13, 319–327. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2011.02.003

Kang, S. M., Min, J. Y., Kim, Y. D., Karigar, C. S., Kim, S. W., Goo, G. H., et al. (2009). Effect of biotic elicitors on the accumulation of bilobalide and ginkgolides in Ginkgo biloba cell cultures. J. Biotechnol. 139, 84–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2008.09.007

Kim, M. S., Haney, M. J., Zhao, Y., Mahajan, V., Deygen, I., Klyachko, N. L., et al. (2016). Development of exosome-encapsulated paclitaxel to overcome MDR in cancer cells. Nanomedicine 12, 655–664. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2015.10.012

Kim, Y. J., Lee, O. R., Ji, Y. O., and Jang, M. G., and and Yang, D. C. (2014). Functional analysis of HMGR encoding genes in triterpene saponin-producing Panax ginseng Meyer. Plant Physiol., 165, 373–387. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.222596

Kim, M. J., Noh, M. H., Woo, S., Lim, H. G., and Jung, G. Y. (2019). Enhanced lycopene production in Escherichia coli by expression of two MEP pathway enzymes from vibrio sp. Dhg. Catalysts 9:1003. doi: 10.3390/catal9121003

Kirby, J., and Keasling, J. D. (2009). Biosynthesis of plant isoprenoids: perspectives for microbial engineering. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 60, 335–355. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.043008.091955

Kong, L. Y., and Tan, R. X. (2015). Artemisinin, a miracle of traditional Chinese medicine. Nat. Prod. Rep. 32, 1617–1621. doi: 10.1039/c5np00133a

Laule, O., Fürholz, A., Chang, H. S., Zhu, T., Wang, X., Heifetz, P. B., et al. (2003). Cross-talk between cytosolic and plastidial pathways of isoprenoid biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100, 6866–6871. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1031755100

Liao, Z. H., Chen, M., Gong, Y. F., Miao, Z. Q., Sun, X. F., and Tang, K. X. (2006). Isoprenoid biosynthesis in plants: pathways, genes, regulation and metabolic engineering. J. Biol. Sci. 6, 209–219. doi: 10.3923/jbs.2006.209.219

Liao, P., Chen, X., Wang, M., Bach, T. J., and Chye, M. L. (2018). Improved fruit alpha-tocopherol, carotenoid, squalene and phytosterol contents through manipulation of Brassica juncea 3-Hydroxy-3-Methylglutaryl-Coa Synthase1 in transgenic tomato. Plant Biotechnol. J. 16, 784–796. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12828

Liao, P., Hemmerlin, A., Bach, T. J., and Chye, M. L. (2016). The potential of the mevalonate pathway for enhanced isoprenoid production. Biotechnol. Adv. 34, 697–713. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2016.03.005

Lu, X. M., Hu, X. J., Zhao, Y. Z., Song, W. B., Zhang, M., Chen, Z. L., et al. (2012). Map-based cloning of zb7 encoding an IPP and DMAPP synthase in the MEP pathway of maize. Mol. Plant 5, 1100–1112. doi: 10.1093/mp/sss038

Lu, X., Tang, K., and Li, P. (2016). Plant metabolic engineering strategies for the production of pharmaceutical Terpenoids. Front. Plant Sci. 7:1647. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01647

Ma, D., Li, G., Zhu, Y., and Xie, D. Y. (2017). Overexpression and suppression of Artemisia annua 4-Hydroxy-3-Methylbut-2-enyl Diphosphate Reductase 1 gene (AaHDR1) differentially regulate Artemisinin and Terpenoid biosynthesis. Front. Plant Sci. 8:77. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00077

Ma, Y., Yuan, L., Wu, B., Li, X., Chen, S., and Lu, S. (2012). Genome-wide identification and characterization of novel genes involved in terpenoid biosynthesis in salvia miltiorrhiza. J. Exp. Bot. 63, 2809–2823. doi: 10.1093/jxb/err466

Mahmoud, S. S., and Croteau, R. B. (2001). Metabolic engineering of essential oil yield and composition in mint by altering expression of deoxyxylulose phosphate reductoisomerase and menthofuran synthase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98, 8915–8920. doi: 10.1073/pnas.141237298

Mahmoud, S. S., and Croteau, R. B. (2002). Strategies for transgenic manipulation of monoterpene biosynthesis in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 7, 366–373. doi: 10.1016/s1360-1385(02)02303-8

Malkin, R., and Niyogi, K. (2000). Photosynthesis. Rockville: American Society of Plant Physiologists.

Maurey, K., Wolf, F., and Golbeck, J. (1986). 3-Hydroxy-3-Methylglutaryl coenzyme A Reductase activity in Ochromonas malhamensis: A system to study the relationship between enzyme activity and rate of steroid biosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 82, 523–527. doi: 10.1104/pp.82.2.523

Morrone, D., Lowry, L., Determan, M. K., Hershey, D. M., Xu, M., and Peters, R. J. (2010). Increasing diterpene yield with a modular metabolic engineering system in E. coli: comparison of MEV and MEP isoprenoid precursor pathway engineering. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 85, 1893–1906. doi: 10.1007/s00253-009-2219-x

Movahedi, A., Zhang, J., Amirian, R., and Zhuge, Q. (2014). An efficient agrobacterium-mediated transformation system for poplar. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 15, 10780–10793. doi: 10.3390/ijms150610780

Movahedi, A., Zhang, J., Sun, W., Mohammadi, K., Almasi Zadeh Yaghuti, A., Wei, H., et al. (2018). Functional analyses of PtRDM1 gene overexpression in poplars and evaluation of its effect on DNA methylation and response to salt stress. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 127, 64–73. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2018.03.011

Movahedi, A., Zhang, J. X., Yin, T. M., and Qiang, Z. G. (2015). Functional analysis of two orthologous NAC genes, CarNAC3, and CarNAC6 from Cicer arietinum, involved in abiotic stresses in poplar. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 33, 1539–1551. doi: 10.1007/s11105-015-0855-0

Munoz-Bertomeu, J., Sales, E., Ros, R., Arrillaga, I., and Segura, J. (2007). Up-regulation of an N-terminal truncated 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl CoA reductase enhances production of essential oils and sterols in transgenic Lavandula latifolia. Plant Biotechnol. J. 5, 746–758. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2007.00286.x

Opitz, S., Nes, W. D., and Gershenzon, J. (2014). Both methylerythritol phosphate and mevalonate pathways contribute to biosynthesis of each of the major isoprenoid classes in young cotton seedlings. Phytochemistry 98, 110–119. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2013.11.010

Perreca, E., Rohwer, J., Gonzalez-Cabanelas, D., Loreto, F., Schmidt, A., Gershenzon, J., et al. (2020). Effect of drought on the Methylerythritol 4-phosphate (MEP) pathway in the isoprene emitting conifer Picea glauca. Front. Plant Sci. 11:546295. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.546295

Ren, D., Liu, Y., Yang, K. Y., Han, L., Mao, G., Glazebrook, J., et al. (2008). A fungal-responsive MAPK cascade regulates phytoalexin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105, 5638–5643. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711301105

Roberts, S. C. (2007). Production and engineering of terpenoids in plant cell culture. Nat. Chem. Biol. 3, 387–395. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2007.8

Rodriguez-Concepcion, M. (2010). Supply of precursors for carotenoid biosynthesis in plants. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 504, 118–122. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2010.06.016

Russell, D. W., and Davidson, H. (1982). Regulation of cytosolic HMG-CoA reductase activity in pea seedlings: contrasting responses to different hormones, and hormone-product interaction, suggest hormonal modulation of activity. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 104, 1537–1543. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(82)91426-7

Sakakibara, H. (2006). Cytokinins: activity, biosynthesis, and translocation. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 57, 431–449. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105231

Schaller, H., Grausem, B., Benveniste, P., Chye, M. L., Tan, C. T., Song, Y. H., et al. (1995). Expression of the Hevea brasiliensis (H.B.K.) Mull. Arg. 3-Hydroxy-3-Methylglutaryl-coenzyme A Reductase 1 in tobacco results in sterol overproduction. Plant Physiol. 109, 761–770. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.3.761

Song, X., Yu, X., Hori, C., Demura, T., Ohtani, M., and Zhuge, Q. (2016). Heterologous overexpression of poplar SnRK2 genes enhanced salt stress tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Front. Plant Sci. 7:612. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00612

Thulasiram, H. V., Erickson, H. K., and Poulter, C. D. (2007). Chimeras of two isoprenoid synthases catalyze all four coupling reactions in isoprenoid biosynthesis. Science 316, 73–76. doi: 10.1126/science.1137786

Tong, Y., Su, P., Zhao, Y., Zhang, M., Wang, X., Liu, Y., et al. (2015). Molecular cloning and characterization of DXS and DXR genes in the Terpenoid biosynthetic pathway of Tripterygium wilfordii. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 16, 25516–25535. doi: 10.3390/ijms161025516

Vaccaro, M., Malafronte, N., Alfieri, M., Tommasi, N., and Leone, A. (2014). Enhanced biosynthesis of bioactive abietane diterpenes by overexpressing AtDXS or AtDXR genes in Salvia sclarea hairy roots. Plant Cell Tiss. Org. 119, 65–77. doi: 10.1007/s11240-014-0514-4

van Schie, C. C., Haring, M. A., and Schuurink, R. C. (2006). Regulation of terpenoid and benzenoid production in flowers. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 9, 203–208. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2006.01.001

Wang, H., Nagegowda, D. A., Rawat, R., Bouvier-Nave, P., Guo, D., Bach, T. J., et al. (2012). Overexpression of Brassica juncea wild-type and mutant HMG-CoA synthase 1 in Arabidopsis up-regulates genes in sterol biosynthesis and enhances sterol production and stress tolerance. Plant Biotechnol. J. 10, 31–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2011.00631.x

Wei, Y., Mohsin, A., Hong, Q., Guo, M., and Fang, H. (2018). Enhanced production of biosynthesized lycopene via heterogenous MVA pathway based on chromosomal multiple position integration strategy plus plasmid systems in Escherichia coli. Bioresour. Technol. 250, 382–389. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2017.11.035

Wille, A., Zimmermann, P., Vranova, E., Furholz, A., Laule, O., Bleuler, S., et al. (2004). Sparse graphical Gaussian modeling of the isoprenoid gene network in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genome Biol. 5:R92. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-11-r92

Wright, L. P., Rohwer, J. M., Ghirardo, A., Hammerbacher, A., Ortiz-Alcaide, M., Raguschke, B., et al. (2014). Deoxyxylulose 5-phosphate synthase controls flux through the Methylerythritol 4-phosphate pathway in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 165, 1488–1504. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.245191

Xie, Z., Kapteyn, J., and Gang, D. R. (2008). A systems biology investigation of the MEP/terpenoid and shikimate/phenylpropanoid pathways points to multiple levels of metabolic control in sweet basil glandular trichomes. Plant J. 54, 349–361. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03429.x

Xing, S., Miao, J., Li, S., Qin, G., Tang, S., Li, H., et al. (2010). Disruption of the 1-deoxy-D-xylulose-5-phosphate reductoisomerase (DXR) gene results in albino, dwarf and defects in trichome initiation and stomata closure in Arabidopsis. Cell Res. 20, 688–700. doi: 10.1038/cr.2010.54

Xing, L., Zhang, D., Zhao, C., Li, Y., Ma, J., An, N., et al. (2016). Shoot bending promotes flower bud formation by miRNA-mediated regulation in apple (Malus domestica Borkh.). Plant Biotechnol. J. 14, 749–770. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12425

Xu, C., Wei, H., Movahedi, A., Sun, W., Ma, X., Li, D., et al. (2019). Evaluation, characterization, expression profiling, and functional analysis of DXS and DXR genes of Populus trichocarpa. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 142, 94–105. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2019.05.034

Xu, J. W., Xu, Y. N., and Zhong, J. J. (2012). Enhancement of ganoderic acid accumulation by overexpression of an N-terminally truncated 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase gene in the basidiomycete Ganoderma lucidum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78, 7968–7976. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01263-12

Yamaguchi, S., and Kamiya, Y., and and Nambara, E. (2018). Regulation of ABA and GA levels during seed development and germination in Arabidopsis. Annu. Plant Rev., 27, 224–247. doi: 10.1002/9781119312994.apr0283

Zhang, K. K., Fan, W., Huang, Z. W., Chen, D. F., Yao, Z. W., Li, Y. F., et al. (2019). Transcriptome analysis identifies novel responses and potential regulatory genes involved in 12-deoxyphorbol-13-phenylacetate biosynthesis of Euphorbia resinifera. Ind. Crop Prod. 135, 138–145. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2019.04.030

Zhang, J., Li, J., Liu, B., Zhang, L., Chen, J., and Lu, M. (2013). Genome-wide analysis of the Populus Hsp90 gene family reveals differential expression patterns, localization, and heat stress responses. BMC Genomics 14:532. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-532

Zhang, J., Movahedi, A., Sang, M., Wei, Z., Xu, J., Wang, X., et al. (2017). Functional analyses of NDPK2 in Populus trichocarpa and overexpression of PtNDPK2 enhances growth and tolerance to abiotic stresses in transgenic poplar. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 117, 61–74. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2017.05.019

Zhang, H., Niu, D., Wang, J., Zhang, S., Yang, Y., Jia, H., et al. (2015). Engineering a platform for photosynthetic pigment, hormone and Cembrane-related Diterpenoid production in Nicotiana tabacum. Plant Cell Physiol. 56, 2125–2138. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcv131

Keywords: methylerythritol phosphate pathway, mevalonic acid pathway, HMGR, DXR, isoprenoid biosynthesis, poplar

Citation: Movahedi A, Wei H, Pucker B, Ghaderi-Zefrehei M, Rasouli F, Kiani-Pouya A, Jiang T, Zhuge Q, Yang L and Zhou X (2022) Isoprenoid biosynthesis regulation in poplars by methylerythritol phosphate and mevalonic acid pathways. Front. Plant Sci. 13:968780. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.968780

Received: 14 June 2022; Accepted: 22 August 2022;

Published: 30 September 2022.

Edited by:

Zhi-Yan (Rock) Du, University of Hawaii at Manoa, United StatesReviewed by:

Min Shi, Zhejiang Chinese Medical University, ChinaCopyright © 2022 Movahedi, Wei, Pucker, Ghaderi-Zefrehei, Rasouli, Kiani-Pouya, Jiang, Zhuge, Yang and Zhou. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Qiang Zhuge, cXpodWdlQG5qZnUuZWR1LmNu; Liming Yang, eWFuZ2xpbWluZ0BuamZ1LmVkdS5jbg==; Xiaohong Zhou, MjAxOTAwMjRAemFmdS5lZHUuY24=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.