95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

MINI REVIEW article

Front. Plant Sci. , 29 July 2022

Sec. Plant Pathogen Interactions

Volume 13 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2022.961840

This article is part of the Research Topic Systemic Resistance and Defense Priming Against Pathogens View all 9 articles

Plants have evolved adaptive strategies to cope with pathogen infections that seriously threaten plant viability and crop productivity. Upon the perception of invading pathogens, the plant immune system is primed, establishing an immune memory that allows primed plants to respond more efficiently to the upcoming pathogen attacks. Physiological, transcriptional, metabolic, and epigenetic changes are induced during defense priming, which is essential to the establishment and maintenance of plant immune memory. As an environmental-friendly technique in crop protection, seed priming could effectively induce plant immune memory. In this review, we highlighted the recent advances in the establishment and maintenance mechanisms of plant defense priming and the immune memory associated, and discussed strategies and challenges in exploiting seed priming on crops to enhance disease resistance.

Plants employ a plethora of mechanisms to defend against invading pathogens, including virus, bacteria, fungi, oomycetes, and pests (Zhou and Zhang, 2020). Thorns, spikes, cuticles, cell walls, and antimicrobial secondary metabolites constitute the plant preformed defense to deter pathogens. As an inducible defense mechanism, pattern-triggered immunity (PTI) is initiated by cell surface-localized pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs) upon the perception of pathogen patterns. In addition, plants utilize intracellular nucleotide-binding domain leucine-rich repeat-containing receptors (NLRs) to detect pathogen effector proteins and activate effector-triggered immunity (ETI; Yu et al., 2017; Saur et al., 2021). PTI and ETI are initiated by different activation mechanisms and usually have distinct dynamics and amplitude. Recent studies revealed that PTI and ETI converge into some common downstream signaling pathways and potentiate each other in the unified plant immunity (Ngou et al., 2021; Yuan et al., 2021a,b).

During long-term coevolution with pathogens, plants have acquired adaptive strategies to cope with recurrent pathogen infections. Perception of initial pathogens by plants could induce a primed state marked by the enhanced activation of defense responses upon the subsequent pathogen challenges (Reimer-Michalski and Conrath, 2016; Mauch-Mani et al., 2017). This defense priming is typically associated with induced resistance (IR) such as systemic acquired resistance (SAR), induced systemic resistance (ISR), and mycorrhiza-induced resistance (MIR; Reimer-Michalski and Conrath, 2016; Mauch-Mani et al., 2017). Defense priming requires immune memory to store the changes or information acquired from the initial pathogen perception, and retrieves this information upon a later pathogen challenge (Ramirez-Prado et al., 2018). As an environmental-friendly, pre-sowing enhancement technique, seed priming could effectively induce plant immune memory and have a great potential in sustainable crop protection (Jogaiah et al., 2020; Joshi et al., 2021; Martínez-Aguilar et al., 2021; Pal et al., 2021; Yadav et al., 2021; Kappel et al., 2022). Herein, we summarized recent development on the establishment and maintenance mechanisms of plant defense priming and the immune memory associated. Strategies, limitations, and future directions in exploiting seed priming for crop protection are discussed.

Primed state of plant immune system could be induced by various biological, physical, and chemical stimuli. Typically, pathogens and their derived molecules such as patterns and effectors could act as warning signals to trigger plant defense priming (Abdul Malik et al., 2020). Furthermore, beneficial interactions with root-colonizing microorganisms could lead to the establishment of primed state (Yu et al., 2022). Moreover, herbivore-associated signals such as physical contacts, oral secretions, and oviposition fluids could function as priming stimuli (Mauch-Mani et al., 2017). Interestingly, certain abiotic stresses such as extreme temperatures and mechanical wounding could prime the plant immune system (cross-priming; Liu et al., 2022). Defense-related phytohormones jasmonic acid (JA), salicylic acid (SA), and their derivatives could induce plant defense priming when applied exogenously (Mauch-Mani et al., 2017). Synthetic functional SA analogs N-cyanomethyl-2-chloro isonicotinic acid (NCI), benzothiadiazole (BTH)/acibenzolar-S-methyl (ASM), and isotianil are potent priming inducers. In addition, a plethora of plant metabolites and related synthetic chemicals such as sulforaphane (SFN), β-amino acids (R)-beta-homoserine (RBH), glycerol, and enzyme ascorbate oxidase (AO) were recently identified as defense priming agents (Buswell et al., 2018; Zhou and Wang, 2018; Li et al., 2020; Singh et al., 2021). Due to their unique physicochemical properties, nanomaterials such as nanoparticles and nanoemulsions are increasingly employed in plant defense priming (Do Espirito Santo Pereira et al., 2021). Notably, functional SA analog BTH/ASM, non-protein amino acid β-aminobutyric acid (BABA), and chitin polymeric derivative chitosan have been successfully developed into commercial priming agents (Yassin et al., 2021).

Upon perception of initial priming stimuli, the plant would enter into the priming phase and undergo physiological, transcriptional, metabolic, and epigenetic changes (Mauch-Mani et al., 2017). Although most of these changes are transient and disappear quickly after the initial stimuli were removed, some alterations could be retained to form plant somatic immune memory (Lämke and Bäurle, 2017). In a few cases, these changes occur in plant reproductive tissues including gametes to form intergenerational or transgenerational immune memory. Generally, plant intergenerational immune memory is unstable during meiosis and affects only one stress-free generation. In contrast, plant transgenerational immune memory is meiotically stable and could be detected in two or more stress-free generations (Ramírez-Carrasco et al., 2017).

After perception of invading pathogens, plants induce defense responses such as elevation in cytoplasmic calcium concentration ([Ca2+]cyt), ROS burst, and callose deposition (Balmer et al., 2015; Cao et al., 2017; Hake and Romeis, 2019). Defense-related calcium changes were reported in various plant cells or tissues in response to the treatment with synthetic PAMPs oligopeptide flg22, pep13, liposaccharides, and chitin (Balmer et al., 2015). Interestingly, noctuid moth (Spodoptera littoralis) feeding could induce a systemic [Ca2+]cyt elevation in Arabidopsis, but this calcium response in Arabidopsis systemic tissues was not observed upon exposure to the synthetic PAMP flg22 (Cao et al., 2017). Pretreatment with polypeptide extract from dry mycelium of Penicillium chrysogenum (PDMP) could induce disease resistance against tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) in tobacco plants (Li et al., 2021b). Recent RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) and fluorescence microscopy demonstrated that pretreatment with PDMP inhibited TMV movement by increasing callose deposition around plasmodesmata (Li et al., 2021b). However, PDMP-induced callose deposition was not observed in the ABA biosynthesis mutant, which could be rescued by exogenous ABA treatment (Li et al., 2021b). These results suggested that PDMP-pretreatment induced ABA biosynthesis-dependent callose priming to protect tobacco plants from TMV infection (Li et al., 2021b).

Massive transcriptional reprogramming has been reported to take place in response to pathogen infections and priming agent treatments in model and crop plants. Although enhanced resistance against P. syringae pv. phaseolicola infection was induced by non-protein amino acid BABA and SA analog INA in common bean (P. vulgaris), but BABA and INA primed different defense-related genes, suggesting that distinct transcriptomic reprogramming takes place in response to different priming stimuli (Martínez-Aguilar et al., 2016). Consistent with this, a transcriptomic analysis showed that 33 genes were specifically induced by the priming agent sulfated laminarin (PS3) but not by laminarin (Lam) in grapevine (Vitis vinifera; Gauthier et al., 2014). Transcriptomic reprogramming induced by priming stimuli ultimately results in massive proteomic changes in primed plants. Indeed, accumulation of MPK3/6, PR proteins, pattern recognition receptor FLS2, and coreceptor BAK1 was primed by BABA and BTH treatment in Arabidopsis thaliana, Lactuca sativa, and Solanum tuberosum (Beckers et al., 2009; Tateda et al., 2014; Baccelli and Mauch-Mani, 2016). Some of these transcriptomic and proteomic changes would confer primed plant enhanced responsiveness to the subsequent pathogen infections.

To prepare for the incoming pathogens, primed plants usually undergo metabolic changes in the biosynthesis of primary and secondary metabolites (Frost et al., 2008; War et al., 2011; Brosset and Blande, 2022). It was recently demonstrated that BABA treatment induced resistance to Botrytis cinerea and affected the contents of soluble sugar and phenylpropanoid metabolites in grape berries (Li et al., 2021a). RNA-seq and comparative transcriptomic analysis revealed that treatment of grapes with 100 mM BABA relatively upregulated genes associated with phenylpropanoid biosynthesis compared with grapes subjected to 10 mM BABA treatment. These results suggested that the BABA-primed defense determines alterations in sucrose and phenylpropanoid metabolism in postharvest grapes (Li et al., 2021a). Interestingly, the grape MYB-type transcription factor VvMYB44 directly activates the expression of sucrose and phenylpropanoid metabolism-related genes, and might participate in BABA-induced priming (Li et al., 2021a).

In plants, methylation of cytosine to 5-methylcytosine (5-mC) mainly occurs in the sequence context of CG, CHG, and CHH (H is A, C, or T; Zhang et al., 2006; Elhamamsy, 2016; Kong et al., 2020; Zhi and Chang, 2021). Plant DNA cytosine methylation profile is initially established via the RNA-dependent DNA methylation (RdDM) pathway involving the DNA methyltransferase DOMAINS REARRANGED METHYLTRANFERASE 2 (DRM2), and maintained by DNA methyltransferases METHYLTRANSFERASE 1 (MET1), CHROMOMETHYLASE 2 (CMT2) and CMT3 during mitosis and meiosis (Yaari et al., 2019; Erdmann and Picard, 2020). As a reversible epigenetic mark, 5-mC could be directly removed by DNA glycosylases such as REPRESSOR OF SILENCING 1 (ROS1), DEMETER (DME), DEMETER-LIKE 2 (DML2), and DML3 in Arabidopsis (Zhu, 2009; Tang et al., 2016). DNA methylation occurs in various genomic regions including gene promoters and transposable elements (Chan et al., 2005; Law and Jacobsen, 2010). Generally, gene promoter hypermethylation is associated with gene repression, whereas transposable element hypermethylation contributes to the TEs silencing and genome stability maintenance (Elhamamsy, 2016; Zhi and Chang, 2021). Genome-wide DNA hypomethylation induced by invading pathogens and/or priming agents has been widely observed in a wide range of plant species, which has been extensively discussed in prior reviews (Atighi et al., 2020; Annacondia et al., 2021; Zhi and Chang, 2021; Huang and Jin, 2022).

Although DNA cytosine methylation usually affects the expression of nearby defense genes in cis, in trans-regulation by DNA methylation might be more important to plant defense priming (van Hulten et al., 2006). Treatment of priming agent BABA leads to a genome-wide DNA cytosine hypomethylation in tomatoes (Catoni et al., 2022). DNA methylome and transcriptome analysis revealed that about 80% of primed tomato genes did not contain any differentially methylated regions (DMRs), suggesting that DNA cytosine methylation regulates the majority of defense-related transcription in-trans (Catoni et al., 2022). PstDC3000-triggered SAR is transmitted to at least two stress-free generations, and this transgenerational SAR was potentiated in the DNA hypomethylation mutant dmr1dmr2ctm3 (ddc; Luna et al., 2012). This study supports the involvement of DNA cytosine methylation in the generational transmission of plant immune memory. Consistent with this, DNA cytosine methylation at the promoter region of the R3a resistance gene is associated with the potato intergenerational resistance against late blight disease (Meller et al., 2018). In Arabidopsis, mitochondrial stress (MS) triggered by exogenous applications of antimycin A (AA) could induce plant resistance (MS-IR) against the biotrophic oomycete pathogen Hyaloperonospora arabidopsidis (Hpa; López Sánchez et al., 2021). It was demonstrated that the MS-IR could be transmitted to one stress-free generation (López Sánchez et al., 2021). Notably, this intergenerational MS-IR is compromised in the DNA hypomethylation mutant nrpe1 and DNA hypermethylation mutant ros1, implicating that DNA cytosine (de)methylation machinery gets involved in the generational transmission of MS-IR (López Sánchez et al., 2021).

N-terminal histone tails stretching out of the nucleosome core could be subject to various modifications such as acetylation and methylation (Imhof and Wolffe, 1998; Tessarz and Kouzarides, 2014; Liu and Chang, 2021; Peng et al., 2021). Histone acetylation catalyzed by histone acetyltransferase (HAT) usually facilitates gene transcription, whereas histone deacetylation mediated by histone deacetylase (HDAC) could repress gene expression. In contrast, histone methylation co-regulated by histone methyltransferase and histone demethylase contributes to both gene repression and activation. Generally, H3K4me3 and H3K36me3 act as active chromatin marks, whereas H3K9me3 and H3K27me3 are linked to repressive chromatin states (Black et al., 2012). Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analysis revealed enrichment of permissive chromatin marks H3K4me3 and H3K36me3 at defense-associated genes was induced by BABA and INA treatments in the common bean (Martínez-Aguilar et al., 2016, 2021). Notably, BABA application could induce the bistable deposition of permissive mark H3K4me2 and repressive mark H3K27me3 on defense-related genes Non-expressor of PR genes (NPR1) and Suppressor of NPR1 (SNI1) in potato (Meller et al., 2018). This switchable chromatin state was proposed to be associated with the enhanced responsiveness of defense genes in primed plants (Meller et al., 2018).

Functional characterization of histone-modifying enzymes sheds novel light on the epigenetic regulation of plant defense priming and immune memory. AtLDL1 and AtLDL2 were identified as two Arabidopsis homologs of human lysine-specific demethylase1-like1 (LDL1; Noh et al., 2021). The ldl1 ldl2 double mutant displayed increased H3K4me1 accumulation at the promoter regions of defense-related genes, potentiated defense-related transcription, and enhanced disease resistance against the secondary Pseudomonas infection (Noh et al., 2021). This evidence supports that LDL1 and lLDL2 negatively regulate the defense priming via the epigenetic suppression of defense-related genes (Noh et al., 2021). The contribution of histone modification to the generational transmission of plant immune memory has been supported by current evidence. BABA treatment could enhance the potato resistance against the oomycete pathogen P. infestans, and this pronounced disease resistance could be transmitted to at least one stress-free generation (Meller et al., 2018). Notably, the enhanced deposition of permissive epigenetic mark H3K4me2 was observed at SA-responsive genes such as StPR1 and StPR2 in both BABA-primed (F0) parent plant and its progeny (F1) in the absence of P. infestans challenge (Meller et al., 2018). This study revealed that the epigenetic mark H3K4me2 might contribute to the generational transmission of immune memory in potatoes (Meller et al., 2018).

In response to developmental and environmental cues, chromatin structure is dynamically and tightly regulated by various modulators such as histone chaperones and chromatin remodelers (Zhou et al., 2015; Song et al., 2021). As a major histone chaperone, CHROMATIN ASSEMBLY FACTOR 1 (CAF-1) could associate with the replisome and gets involved in the de novo assembly of histone H3 and H4 into nucleosomes (Han et al., 2015; Mozgová et al., 2015; Muñoz-Viana et al., 2017). Nucleosome occupancy micrococcal nuclease (MNase) assays revealed low nucleosome enrichment at common bean (P. vulgaris) PATHOGENESIS RELATED GENE-1 gene (PvPR1) was induced by either INA treatment or Pseudomonas syringae pv. phaseolicola NPS3121 (PspNPS3121) infection (Martínez-Aguilar et al., 2021). This study suggested that chromatin structure at defense-related genes was changed by pathogen infections and/or priming agent treatments. Consistent with this, BABA treatment and SA application both lead to reduced nucleosome occupancy at defense-related genes PR1, PR5, WRKY6, and WRKY53 in Arabidopsis (Mozgová et al., 2015). Notably, chromatin features such as low nucleosome occupancy at defense-related genes in CAF-1 mutants fasciata2 (fas2) resemble BABA-primed or SA-treated wild-type plants, suggesting that histone chaperone CAF-1 suppresses chromatin structure changes essential for plant defense priming (Mozgová et al., 2015). In addition to histone chaperons, chromatin remodelers regulate chromatin structure changes in plant defense response and priming. Chromatin remodeling factor DDM1 is a SWI2/SNF2-like protein (Brzeski and Jerzmanowski, 2003). Loss of DDM1 functions resulted in decreased DNA cytosine methylation in the Arabidopsis NB-LRR-encoding genes (Li et al., 2010; Kong et al., 2018). Another Arabidopsis chromatin remodeling factor MOM1 was demonstrated to regulate the expression of immune receptor genes by targeting distal pericentromeric transposable elements (Cambiagno et al., 2018). Interestingly, treatment with priming compound BIT (1,2-benzisothiazol-3(2 h)-one,1, 1-dioxide) in rice could inhibit the expression of the rice chromatin remodeler gene BRHIS1, and attenuate the suppression of BRHIS1 on defense-related transcription (Li et al., 2015). This study suggested a potential role of chromatin remodeler BRHIS1 in repressing chromatin remodeling required for defense priming in rice (Li et al., 2015).

Seed priming is a feasible, pre-sowing enhancement technique and has been widely employed in the commercial production of crop seeds (Paparella et al., 2015). As extensively discussed in prior reviews, seed priming initiates multiple pre-germinative metabolisms, including enzyme activation, energy production, metabolites biosynthesis, and DNA repair (Hussain et al., 2016). Seed priming could secure the enhanced and uniformed seed germination and seedling establishment under field conditions, and greatly contributes to the improvement of crop growth and production (Marthandan et al., 2020; Johnson and Puthur, 2021). Increasing evidence revealed that seed priming could induce plant immune memory that is either stably maintained throughout developmental stages or transmitted over generations (Jogaiah et al., 2020; Joshi et al., 2021; Martínez-Aguilar et al., 2021; Pal et al., 2021; Yadav et al., 2021; Kappel et al., 2022). As summarized in Table 1, different types of seed priming approaches such as biological priming, chemical priming, and nanomaterials priming have been successfully established to protect crop plants against pathogen infections.

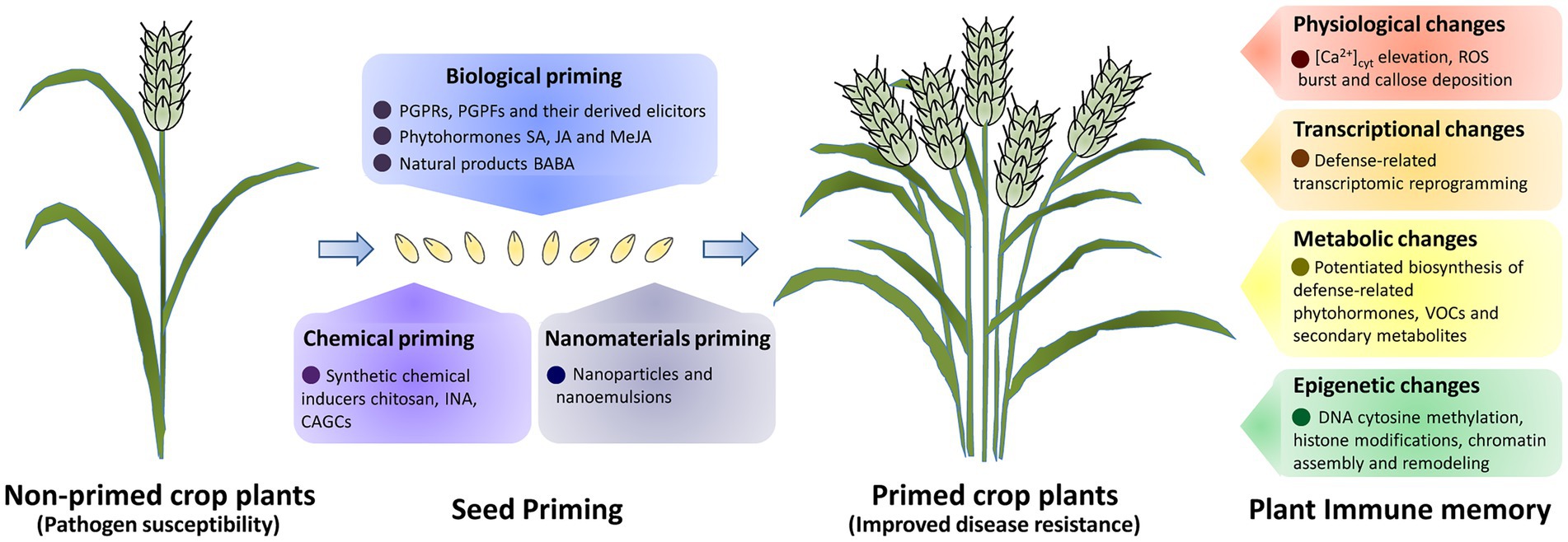

Beneficial microbes such as plant-growth-promoting fungi (PGPFs) Trichoderma spp., plant-growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPRs) Pseudomonas spp., Paenibacillus spp., and Bacillus spp. have been employed in seed primings on crops (summarized in Table 1 and Figure 1). Seed priming of chilli with PGPFs T. harzianum, T. asperellum, and PGFR Paenibacillus dendritiformis triggers physiological, transcriptional, and metabolic changes such as ROS burst and induction of defense-related enzymes and phenolic compounds, as well as increased disease resistance against anthracnose disease (Mitra et al., 2021; Yadav et al., 2021). Sugar beet primed with the PGPF T. atroviride exhibited upregulation of defense gene BvPR3 and induced systemic resistance against Cercospora leaf spot (CLS) disease (Kappel et al., 2022). In addition, seed priming of crop plants with elicitors derived from beneficial microbes also could trigger immune memory, as well as induced resistance, throughout their developmental stages. Seed priming of pearl millet with total crude protein (TCP) extracted from Trichoderma spp. enhanced levels of peroxidase and lipoxygenase, and induced pearl millet disease resistance against downy mildew (Nandini et al., 2017). Pearl millet primed with LPS isolated from Pseudomonas fluorescens exhibited physiological and transcriptional changes such as ROS burst, callose deposition, and upregulation of PR genes, as well as induced disease resistance against downy mildew disease (Lavanya et al., 2018).

Figure 1. A schematic of seed priming and plant immune memory for crop disease resistance improvement. Priming of crop seeds with beneficial microbes and their derived elicitors, phytohormones and natural products, biological primimg could lead to the establishment of immune memory and induced crop disease resistance. Seed primimg with synthetic chemical inducers (chemical primimg), also could improve crop disease resistance. Physiological, transcriptional, metabolic and epigenetic changes are induced in defence priming to establish the immune memory in primed crop plants.

Phytohormones SA and JA and plant natural product BABA could effectively induce crop disease resistance when applied exogenously in seed priming (summarized in Table 1 and Figure 1). For instance, eggplant primed with SA exhibited upregulation of defense-related genes MPK1, GPX, and PRs, and showed increased disease resistance against Verticillium wilt (Mahesh et al., 2017). Priming of tomato with SA induced expression of APx, CAT, and GR, and enhanced bacterial spot disease resistance (Srinivasa et al., 2022). Notably, MeJA-primed tomato plants exhibited increased levels SA, kaempferol, and quercetin, upregulation of PAL5, BSMT, CHS, and FLS, as well as enhanced tomato disease resistance to the hemi-biotroph Fusarium oxysporum (Król et al., 2015). In addition, pearl millet primed with BABA exhibited significant changes in protein abundance and enhanced disease resistance against downy mildew (Anup et al., 2015). These studies paved a path for the exploitation of phytohormones and natural products in seed priming for crop protection.

Synthetic chemical inducers chitosan, INA, and cholic acid-glycine conjugates (CAGCs) have been successfully applied in the seed priming of crop plants for disease resistance improvement (see Table 1 and Figure 1). Priming of cucumber with chitosan induced deposition of lignin and callose, enhanced the accumulation of defense-responsive enzymes, and increased disease resistance against powdery mildew (Jogaiah et al., 2020). Chitosan-primed sugar beet plants exhibited upregulation of PR3, PAL, and GST genes, as well as enhanced resistance against CLS disease (Kappel et al., 2022). Rice primed with CAGCs induced expression of defense genes EDS1, ICS1, NPR1, MKK4, and PR1 genes, and enhanced resistance against rice bacterial leaf blight disease (Pal et al., 2021). Notably, INA-primed common bean plants and their stress-free offsprings exhibited epigenetic changes such as enrichment of H3K4me3 and H3K36me3, as well as low nucleosome occupancy at PvPR1 gene (Martínez-Aguilar et al., 2021). This study demonstrated that seed priming with INA induced the establishment of transgenerational immune memory in common bean (Martínez-Aguilar et al., 2021). Consistent with this, INA-primed common bean plants and their stress-free offsprings exhibited reduced susceptibility to the bacterial pathogen P. syringae pv. phaseolicola (Martínez-Aguilar et al., 2021). Recently, advanced chemical inducers-synthesis strategies such as computer-aided inducer design have been developed, which would certainly contribute to the advance of seed priming and its application in crop protection (Zhou and Wang, 2018).

With the advance in nanotechnology, several nanomaterials have been developed for crop protection (Do Espirito Santo Pereira et al., 2021). As summarized in Table 1 and Figure 1, nanomaterials could effectively trigger crop immune memory and induced disease resistance when applied exogenously in defense priming (Quiterio-Gutiérrez et al., 2019; Shelar et al., 2021). Seed priming of tomato with mycogenic selenium nanoparticles (SeNPs) induced accumulation of lignin and hydrogen peroxide, as well as elevated expression levels of LOX, PAL, GLU, and SOD genes (Table 1; Joshi et al., 2021). These SeNP-primed tomato plants displayed enhanced resistance against the late blight caused by Phytophthora infestans throughout their developmental stages, indicating that nanoparticles could be applied in the seed priming for crop protection (Joshi et al., 2021). Priming of pearl millet with nanoemulsions formulated from membrane lipids of Trichoderma brevicompactum (UP-91) effectively induced deposition of lignin, ROS, and callose, and increased pearl millet resistance against downy mildew disease (Table 1; Nandini et al., 2019). This study suggested that combined nanotechnology with biological priming might represent a promising seed priming method for crop protection (Table 1; Nandini et al., 2019).

To secure crop production under pathogen threats, natural and induced genetic variations have been employed for crop improvement via conventional or genomic breeding (Rodriguez-Moreno et al., 2017). Genetic engineering, genomic editing, and targeting induced local lesions in genomes (TILLING) of resistance or susceptibility genes represent promising approaches in crop breeding (Bruce, 2012; Acevedo-Garcia et al., 2017; Gao, 2021; Koseoglou et al., 2022). At the same time, integrated management systems based on host-pathogen-environment interaction have been established to control some pathogens and pests (Jindo et al., 2021). Compared with these current approaches, seed priming is cost and time effective, and applicable to a wide range of crop species, including those recalcitrant crops with low rates of transformation and regeneration. Furthermore, seed priming could enhance crop resistance to multiple types of pathogens. For example, BABA enhances disease resistance against powdery mildew and downy mildew in several crop species (Worrall et al., 2012; Anup et al., 2015). As discussed in the epigenetic section in detail, defense priming induced epigenetic changes such as alteration in DNA methylation, which could lead to mobilization of transposable elements and formation of heritable genetic variations (Luna et al., 2012; Meller et al., 2018; López Sánchez et al., 2021; Catoni et al., 2022). These genetic variations could be employed for breeding purposes, which might provide a direction to integrate priming strategy into breeding programs in future research.

Although seed priming has great potential for use in crop protection, caution must be exercised in the application of priming materials. The safety of priming microbes, chemicals, and nanomaterials, as well as their impact on ecosystems and fates in environments, needs to be extensively evaluated before large-scale application. Some priming chemicals such as BABA, chitosan, and BTH are commercially available, but industrial production of other priming materials such as PGPFs, RGRRs, and nanomaterials need to be established or optimized to meet the demand in agronomical practices. Since pre-treatment with some priming materials like BABA and BTH usually induces plant defense response and leads to growth penalty, it is crucial to establish proper application conditions for each priming agent (Buswell et al., 2018). In addition, priming concentration and duration also need to be optimized for each crop variety.

In this review, we summarized molecular bases of plant defense priming and immune memory associated, and discussed recent advances and future directions in exploiting seed priming for crop protection. As shown in Figure 1, seed priming of crop plants with beneficial microbes, phytohormones, and natural products (biological priming), synthetic chemical inducers (chemical priming), nanoemulsions, and nanoparticles (nanomaterials priming) could effectively improve crop resistance against pathogen infections. Physiological, transcriptional, metabolic, and epigenetic changes are induced by defense priming to constitute the immune memory that is either stably maintained in developmental stages or transmitted over generations in primed crop plants. Although the past decade has seen great progress in exploiting seed priming for crop protection, we still have a long way to go towards fully understanding the mechanism of plant immune memory as well as its application in sustainable agriculture. For instance, most of our knowledge about the molecular mechanism of plant defense priming comes from the study of model plants like Arabidopsis, establishment and maintenance mechanisms of plant defense priming in crop plants is poorly understood. Furthermore, seed priming has been widely reported on crop protection against pathogenic microbes, but its effectiveness against herbivores is less documented. In addition, degradation of thermomemory-associated heat shock proteins (HSPs) by autophagy contributes to erasing thermomemory in Arabidopsis, but the resetting mechanism of plant immune memory remains to be disclosed (Hilker and Schmülling, 2019; Sedaghatmehr et al., 2019). With the advance in the knowledge of plant immune memory and the development of priming methodology, exploiting seed priming would provide new avenues for better crop protection in future agriculture.

CC, ZY, and PZ wrote this manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31701412), the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (ZR2017BC109), Qingdao Science and Technology Bureau Fund (17-1-1-50-jch), and Qingdao University Fund (DC1900005385).

We would like to thank Nicolás M. Cecchini for the kind invitation to write this review. We are also grateful to two reviewers for their very helpful comments and suggestions on this manuscript.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abdelrahman, M., Abdel-Motaal, F., El-Sayed, M., Jogaiah, S., Shigyo, M., Ito, S. I., et al. (2016). Dissection of Trichoderma longibrachiatum-induced defense in onion (Allium cepa L.) against Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. cepa by target metabolite profiling. Plant Sci. 246, 128–138. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2016.02.008

Abdul Malik, N. A., Kumar, I. S., and Nadarajah, K. (2020). Elicitor and receptor molecules: orchestrators of plant defense and immunity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 963. doi: 10.3390/ijms21030963

Acevedo-Garcia, J., Spencer, D., Thieron, H., Reinstädler, A., Hammond-Kosack, K., Phillips, A. L., et al. (2017). Mlo-based powdery mildew resistance in hexaploid bread wheat generated by a non-transgenic TILLING approach. Plant Biotechnol. J. 15, 367–378. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12631

Annacondia, M. L., Markovic, D., Reig-Valiente, J. L., Scaltsoyiannes, V., Pieterse, C., Ninkovic, V., et al. (2021). Aphid feeding induces the relaxation of epigenetic control and the associated regulation of the defense response in Arabidopsis. New Phytol. 230, 1185–1200. doi: 10.1111/nph.17226

Anup, C. P., Melvin, P., Shilpa, N., Gandhi, M. N., Jadhav, M., Ali, H., et al. (2015). Proteomic analysis of elicitation of downy mildew disease resistance in pearl millet by seed priming with β-aminobutyric acid and Pseudomonas fluorescens. J. Proteome 120, 58–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2015.02.013

Atighi, M. R., Verstraeten, B., De Meyer, T., and Kyndt, T. (2020). Genome-wide DNA hypomethylation shapes nematode pattern-triggered immunity in plants. New Phytol. 227, 545–558. doi: 10.1111/nph.16532

Baccelli, I., and Mauch-Mani, B. (2016). Beta-aminobutyric acid priming of plant defense: the role of ABA and other hormones. Plant Mol. Biol. 91, 703–711. doi: 10.1007/s11103-015-0406-y

Balmer, A., Pastor, V., Gamir, J., Flors, V., and Mauch-Mani, B. (2015). The ‘prime-ome’: towards a holistic approach to priming. Trends Plant Sci. 20, 443–452. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2015.04.002

Beckers, G. J., Jaskiewicz, M., Liu, Y., Underwood, W. R., He, S. Y., Zhang, S., et al. (2009). Mitogen-activated protein kinases 3 and 6 are required for full priming of stress responses in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 21, 944–953. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.062158

Black, J. C., Van Rechem, C., and Whetstine, J. R. (2012). Histone lysine methylation dynamics: establishment, regulation, and biological impact. Mol. Cell 48, 491–507. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.11.006

Brosset, A., and Blande, J. D. (2022). Volatile-mediated plant-plant interactions: volatile organic compounds as modulators of receiver plant defence, growth, and reproduction. J. Exp. Bot. 73, 511–528. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erab487

Bruce, T. J. A. (2012). GM as a route for delivery of sustainable crop protection. J. Exp. Bot. 63, 537–541. doi: 10.1093/jxb/err281

Brzeski, J., and Jerzmanowski, A. (2003). Deficient in DNA methylation 1 (DDM1) defines a novel family of chromatin-remodeling factors. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 823–828. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209260200

Buswell, W., Schwarzenbacher, R. E., Luna, E., Sellwood, M., Chen, B., Flors, V., et al. (2018). Chemical priming of immunity without costs to plant growth. New Phytol. 218, 1205–1216. doi: 10.1111/nph.15062

Cambiagno, D. A., Nota, F., Zavallo, D., Rius, S., Casati, P., Asurmendi, S., et al. (2018). Immune receptor genes and pericentromeric transposons as targets of common epigenetic regulatory elements. Plant J. 96, 1178–1190. doi: 10.1111/tpj.14098

Cao, X. Q., Jiang, Z. H., Yi, Y. Y., Yang, Y., Ke, L. P., Pei, Z. M., et al. (2017). Biotic and abiotic stresses activate different Ca2+ permeable channels in Arabidopsis. Front. Plant Sci. 8:83. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00083

Catoni, M., Alvarez-Venegas, R., Worrall, D., Holroyd, G., Barraza, A., Luna, E., et al. (2022). Long-lasting defence priming by β-aminobutyric acid in tomato is marked by genome-wide changes in DNA methylation. Front. Plant Sci. 13:836326. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.836326

Chan, S. W.-L., Henderson, I. R., and Jacobsen, S. E. (2005). Gardening the genome: DNA methylation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nat. Rev. Genet. 6, 351–360. doi: 10.1038/nrg1601

Do Espirito Santo Pereira, A., Caixeta Oliveira, H., Fernandes Fraceto, L., and Santaella, C. (2021). Nanotechnology potential in seed priming for sustainable agriculture. Nanomaterials (Basel) 11, 267. doi: 10.3390/nano11020267

Elhamamsy, A. R. (2016). DNA methylation dynamics in plants and mammals: overview of regulation and dysregulation. Cell Biochem. Funct. 34, 289–298. doi: 10.1002/cbf.3183

Erdmann, R. M., and Picard, C. L. (2020). RNA-directed DNA methylation. PLoS Genet. 16:e1009034. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1009034

Frost, C. J., Mescher, M. C., Carlson, J. E., and De Moraes, C. M. (2008). Plant defense priming against herbivores: getting ready for a different battle. Plant Physiol. 146, 818–824. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.113027

Gao, C. (2021). Genome engineering for crop improvement and future agriculture. Cell 184, 1621–1635. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.01.005

Gauthier, A., Trouvelot, S., Kelloniemi, J., Frettinger, P., Wendehenne, D., Daire, X., et al. (2014). The sulfated laminarin triggers a stress transcriptome before priming the SA- and ROS-dependent defenses during grapevine’s induced resistance against Plasmopara viticola. PLoS One 9:e88145. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0088145

Hake, K., and Romeis, T. (2019). Protein kinase-mediated signalling in priming: immune signal initiation, propagation, and establishment of long-term pathogen resistance in plants. Plant Cell Environ. 42, 904–917. doi: 10.1111/pce.13429

Han, S. K., Wu, M. F., Cui, S., and Wagner, D. (2015). Roles and activities of chromatin remodeling ATPases in plants. Plant J. 83, 62–77. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12877

Hilker, M., and Schmülling, T. (2019). Stress priming, memory, and signalling in plants. Plant Cell Environ. 42, 753–761. doi: 10.1111/pce.13526

Huang, C. Y., and Jin, H. (2022). Coordinated epigenetic regulation in plants: a potent managerial tool to conquer biotic stress. Front. Plant Sci. 12:795274. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.795274

Hussain, S., Khan, F., Hussain, H. A., and Nie, L. (2016). Physiological and biochemical mechanisms of seed priming-induced chilling tolerance in rice cultivars. Front. Plant Sci. 7:116. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00116

Imhof, A., and Wolffe, A. P. (1998). Transcription: gene control by targeted histone acetylation. Curr. Biol. 8, R422–R424. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(98)70268-4

Jindo, K., Evenhuis, A., Kempenaar, C., Pombo Sudré, C., Zhan, X., Goitom Teklu, M., et al. (2021). Review: holistic pest management against early blight disease towards sustainable agriculture. Pest Manag. Sci. 77, 3871–3880. doi: 10.1002/ps.6320

Jogaiah, S., Abdelrahman, M., Tran, L. S., and Shin-ichi, I. (2013). Characterization of rhizosphere fungi that mediate resistance in tomato against bacterial wilt disease. J. Exp. Bot. 64, 3829–3842. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ert212

Jogaiah, S., Satapute, P., De Britto, S., Konappa, N., and Udayashankar, A. C. (2020). Exogenous priming of chitosan induces upregulation of phytohormones and resistance against cucumber powdery mildew disease is correlated with localized biosynthesis of defense enzymes. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 162, 1825–1838. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.08.124

Johnson, R., and Puthur, J. T. (2021). Seed priming as a cost effective technique for developing plants with cross tolerance to salinity stress. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 162, 247–257. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2021.02.034

Joshi, S. M., De Britto, S., and Jogaiah, S. (2021). Myco-engineered selenium nanoparticles elicit resistance against tomato late blight disease by regulating differential expression of cellular, biochemical and defense responsive genes. J. Biotechnol. 325, 196–206. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2020.10.023

Kappel, L., Kosa, N., and Gruber, S. (2022). The multilateral efficacy of chitosan and Trichoderma on sugar beet. J. Fungi (Basel). 8, 137. doi: 10.3390/jof8020137

Kong, W., Li, B., Wang, Q., Wang, B., Duan, X., Ding, L., et al. (2018). Analysis of the DNA methylation patterns and transcriptional regulation of the NB-LRR-encoding gene family in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Mol. Biol. 96, 563–575. doi: 10.1007/s11103-018-0715-z

Kong, L., Liu, Y., Wang, X., and Chang, C. (2020). Insight into the role of epigenetic processes in abiotic and biotic stress response in wheat and barley. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 1480. doi: 10.3390/ijms21041480

Koseoglou, E., van der Wolf, J. M., Visser, R., and Bai, Y. (2022). Susceptibility reversed: modified plant susceptibility genes for resistance to bacteria. Trends Plant Sci. 27, 69–79. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2021.07.018

Król, P., Igielski, R., Pollmann, S., and Kępczyńska, E. (2015). Priming of seeds with methyl jasmonate induced resistance to hemi-biotroph Fusarium oxysporum f.sp. lycopersici in tomato via 12-oxo-phytodienoic acid, salicylic acid, and flavonol accumulation. J. Plant Physiol. 179, 122–132. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2015.01.018

Lämke, J., and Bäurle, I. (2017). Epigenetic and chromatin-based mechanisms in environmental stress adaptation and stress memory in plants. Genome Biol. 18, 124. doi: 10.1186/s13059-017-1263-6

Lavanya, S. N., Udayashankar, A. C., Raj, S. N., Mohan, C. D., Gupta, V. K., Tarasatyavati, C., et al. (2018). Lipopolysaccharide-induced priming enhances NO-mediated activation of defense responses in pearl millet challenged with Sclerospora graminicola. 3. Biotech 8, 475. doi: 10.1007/s13205-018-1501-y

Law, J. A., and Jacobsen, S. E. (2010). Establishing, maintaining and modifying DNA methylation patterns in plants and animals. Nat. Rev. Genet. 11, 204–220. doi: 10.1038/nrg2719

Li, X., Jiang, Y., Ji, Z., Liu, Y., and Zhang, Q. (2015). BRHIS1 suppresses rice innate immunity through binding to monoubiquitinated H2A and H2B variants. EMBO Rep. 16, 1192–1202. doi: 10.15252/embr.201440000

Li, Y., Jiao, M., Li, Y., Zhong, Y., Li, X., Chen, Z., et al. (2021b). Penicillium chrysogenum polypeptide extract protects tobacco plants from tobacco mosaic virus infection through modulation of ABA biosynthesis and callose priming. J. Exp. Bot. 72, 3526–3539. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erab102

Li, Y., Qiu, L., Liu, X., Zhang, Q., Zhuansun, X., Fahima, T., et al. (2020). Glycerol-induced powdery mildew resistance in wheat by regulating plant fatty acid metabolism, plant hormones cross-talk, and Pathogenesis-related genes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 673. doi: 10.3390/ijms21020673

Li, Y., Tessaro, M. J., Li, X., and Zhang, Y. (2010). Regulation of the expression of plant resistance gene SNC1 by a protein with a conserved BAT2 domain. Plant Physiol. 153, 1425–1434. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.156240

Li, C., Wang, K., Lei, C., Cao, S., Huang, Y., Ji, N., et al. (2021a). Alterations in sucrose and phenylpropanoid metabolism affected by BABA-primed defense in postharvest grapes and the associated transcriptional mechanism. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 34, 1250–1266. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-06-21-0142-R

Liu, H., Able, A. J., and Able, J. A. (2022). Priming crops for the future: rewiring stress memory. Trends Plant Sci. 27, 699–716 doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2021.11.015

Liu, J., and Chang, C. (2021). Concerto on chromatin: interplays of different epigenetic mechanisms in plant development and environmental adaptation. Plants (Basel) 10, 2766. doi: 10.3390/plants10122766

López Sánchez, A., Hernández Luelmo, S., Izquierdo, Y., López, B., Cascón, T., and Castresana, C. (2021). Mitochondrial stress induces plant resistance through chromatin changes. Front. Plant Sci. 12:704964. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.704964

Luna, E., Bruce, T. J., Roberts, M. R., Flors, V., and Ton, J. (2012). Next-generation systemic acquired resistance. Plant Physiol. 158, 844–853. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.187468

Mahesh, H. M., Murali, M., Chandra, A., Melvin, P., and Sharada, M. S. (2017). Salicylic acid seed priming instigates defense mechanism by inducing PR-proteins in Solanum melongena L. upon infection with Verticillium dahlia Kleb. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 117, 12–23. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2017.05.012

Manjunatha, G., Roopa, K. S., Prashanth, G. N., and Shetty, H. S. (2008). Chitosan enhances disease resistance in pearl millet against downy mildew caused by Sclerospora graminicola and defence-related enzyme activation. Pest Manag. Sci. 64, 1250–1257. doi: 10.1002/ps.1626

Marthandan, V., Geetha, R., Kumutha, K., Renganathan, V. G., Karthikeyan, A., and Ramalingam, J. (2020). Seed priming: a feasible strategy to enhance drought tolerance in crop plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 8258. doi: 10.3390/ijms21218258

Martínez-Aguilar, K., Hernández-Chávez, J. L., and Alvarez-Venegas, R. (2021). Priming of seeds with INA and its transgenerational effect in common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) plants. Plant Sci. 305:110834. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2021.110834

Martínez-Aguilar, K., Ramírez-Carrasco, G., Hernández-Chávez, J. L., Barraza, A., and Alvarez-Venegas, R. (2016). Use of BABA and INA as activators of a primed state in the common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). Front. Plant Sci. 7:653. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00653

Mauch-Mani, B., Baccelli, I., Luna, E., and Flors, V. (2017). Defense priming: an adaptive part of induced resistance. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 68, 485–512. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042916-041132

Meller, B., Kuźnicki, D., Arasimowicz-Jelonek, M., Deckert, J., and Floryszak-Wieczorek, J. (2018). BABA-primed histone modifications in potato for intergenerational resistance to Phytophthora infestans. Front. Plant Sci. 9:1228. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.01228

Mishra, A., Singh, S. P., Mahfooz, S., Singh, S. P., Bhattacharya, A., Mishra, N., et al. (2018). Endophyte-mediated modulation of defense-related genes and systemic resistance in Withaniasomnifera (L.) dunal under Alternaria alternata stress. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 84, e02845–e02817. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02845-17

Mitra, D., Mondal, R., Khoshru, B., Shadangi, S., Das Mohapatra, P. K., and Panneerselvam, P. (2021). Rhizobacteria mediated seed bio-priming triggers the resistance and plant growth for sustainable crop production. Curr. Res. Microb. Sci. 2:100071. doi: 10.1016/j.crmicr.2021.100071

Mozgová, I., Wildhaber, T., Liu, Q., Abou-Mansour, E., L'Haridon, F., Métraux, J. P., et al. (2015). Chromatin assembly factor CAF-1 represses priming of plant defence response genes. Nat. Plants 1:15127. doi: 10.1038/nplants.2015.127

Muñoz-Viana, R., Wildhaber, T., Trejo-Arellano, M. S., Mozgová, I., and Hennig, L. (2017). Arabidopsis chromatin assembly factor 1 is required for occupancy and position of a subset of nucleosomes. Plant J. 92, 363–374. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13658

Nandini, B., Hariprasad, P., Shankara, H. N., Prakash, H. S., and Geetha, N. (2017). Total crude protein extract of Trichoderma spp. induces systemic resistance in pearl millet against the downy mildew pathogen. 3. Biotech 7, 183. doi: 10.1007/s13205-017-0816-4

Nandini, B., Puttaswamy, H., Prakash, H. S., Adhikari, S., Jogaiah, S., and Nagaraja, G. (2019). Elicitation of novel trichogenic-lipid nanoemulsion signaling resistance against pearl millet downy mildew disease. Biomol. Ther. 10, 25. doi: 10.3390/biom10010025

Ngou, B., Ahn, H. K., Ding, P., and Jones, J. (2021). Mutual potentiation of plant immunity by cell-surface and intracellular receptors. Nature 592, 110–115. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03315-7

Noh, S. W., Seo, R. R., Park, H. J., and Jung, H. W. (2021). Two Arabidopsis homologs of human lysine-specific demethylase function in epigenetic regulation of plant defense responses. Front. Plant Sci. 12:688003. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.688003

Pal, G., Mehta, D., Singh, S., Magal, K., Gupta, S., Jha, G., et al. (2021). Foliar application or seed priming of cholic acid-glycine conjugates can mitigate/prevent the rice bacterial leaf blight disease via activating plant defense genes. Front. Plant Sci. 12:746912. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.746912

Paparella, S., Araújo, S. S., Rossi, G., Wijayasinghe, M., Carbonera, D., and Balestrazzi, A. (2015). Seed priming: state of the art and new perspectives. Plant Cell Rep. 34, 1281–1293. doi: 10.1007/s00299-015-1784-y

Peng, Y., Li, S., Landsman, D., and Panchenko, A. R. (2021). Histone tails as signaling antennas of chromatin. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 67, 153–160. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2020.10.018

Quiterio-Gutiérrez, T., Ortega-Ortiz, H., Cadenas-Pliego, G., Hernández-Fuentes, A. D., Sandoval-Rangel, A., Benavides-Mendoza, A., et al. (2019). The application of selenium and copper nanoparticles modifies the biochemical responses of tomato plants under stress by Alternaria solani. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 1950. doi: 10.3390/ijms20081950

Ramírez-Carrasco, G., Martínez-Aguilar, K., and Alvarez-Venegas, R. (2017). Transgenerational defense priming for crop protection against plant pathogens: a hypothesis. Front. Plant Sci. 8:696. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00696

Ramirez-Prado, J. S., Abulfaraj, A. A., Rayapuram, N., Benhamed, M., and Hirt, H. (2018). Plant immunity: from signaling to epigenetic control of defense. Trends Plant Sci. 23, 833–844. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2018.06.004

Reimer-Michalski, E. M., and Conrath, U. (2016). Innate immune memory in plants. Semin. Immunol. 28, 319–327. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2016.05.006

Rodriguez-Moreno, L., Song, Y., and Thomma, B. P. (2017). Transfer and engineering of immune receptors to improve recognition capacities in crops. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 38, 42–49. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2017.04.010

Saur, I., Panstruga, R., and Schulze-Lefert, P. (2021). NOD-like receptor-mediated plant immunity: from structure to cell death. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 21, 305–318. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-00473-z

Sedaghatmehr, M., Thirumalaikumar, V. P., Kamranfar, I., Marmagne, A., Masclaux-Daubresse, C., and Balazadeh, S. (2019). A regulatory role of autophagy for resetting the memory of heat stress in plants. Plant Cell Environ. 42, 1054–1064. doi: 10.1111/pce.13426

Shelar, A., Singh, A. V., Maharjan, R. S., Laux, P., Luch, A., Gemmati, D., et al. (2021). Sustainable agriculture through multidisciplinary seed nanopriming: prospects of opportunities and challenges. Cell 10, 2428. doi: 10.3390/cells10092428

Singh, R. R., Pajar, J. A., Audenaert, K., and Kyndt, T. (2021). Induced resistance by ascorbate oxidation involves potentiating of the phenylpropanoid pathway and improved rice tolerance to parasitic nematodes. Front. Plant Sci. 12:713870. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.713870

Song, G. C., Choi, H. K., Kim, Y. S., Choi, J. S., and Ryu, C. M. (2017). Seed defense biopriming with bacterial cyclodipeptides triggers immunity in cucumber and pepper. Sci. Rep. 7, 14209. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-14155-9

Song, Z. T., Liu, J. X., and Han, J. J. (2021). Chromatin remodeling factors regulate environmental stress responses in plants. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 63, 438–450. doi: 10.1111/jipb.13064

Srinivasa, C., Umesha, S., Pradeep, S., Ramu, R., Gopinath, S. M., Ansari, M. A., et al. (2022). Salicylic acid-mediated enhancement of resistance in tomato plants against Xanthomonas perforans. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 29, 2253–2261. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2021.11.067

Tang, K., Lang, Z., Zhang, H., and Zhu, J. K. (2016). The DNA demethylase ROS1 targets genomic regions with distinct chromatin modifications. Nat. Plants 2, 16169. doi: 10.1038/nplants.2016.169

Tateda, C., Zhang, Z., Shrestha, J., Jelenska, J., Chinchilla, D., and Greenberg, J. T. (2014). Salicylic acid regulates Arabidopsis microbial pattern receptor kinase levels and signaling. Plant Cell 26, 4171–4187. doi: 10.1105/tpc.114.131938

Tessarz, P., and Kouzarides, T. (2014). Histone core modifications regulating nucleosome structure and dynamics. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 15, 703–708. doi: 10.1038/nrm3890

van Hulten, M., Pelser, M., van Loon, L. C., Pieterse, C. M., and Ton, J. (2006). Costs and benefits of priming for defense in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103, 5602–5607. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510213103

War, A. R., Sharma, H. C., Paulraj, M. G., War, M. Y., and Ignacimuthu, S. (2011). Herbivore induced plant volatiles: their role in plant defense for pest management. Plant Signal. Behav. 6, 1973–1978. doi: 10.4161/psb.6.12.18053

Worrall, D., Holroyd, G. H., Moore, J. P., Glowacz, M., Croft, P., Taylor, J. E., et al. (2012). Treating seeds with activators of plant defence generates long-lasting priming of resistance to pests and pathogens. New Phytol. 193, 770–778. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2011.03987.x

Yaari, R., Katz, A., Domb, K., Harris, K. D., Zemach, A., and Ohad, N. (2019). RdDM-independent de novo and heterochromatin DNA methylation by plant CMT and DNMT3 orthologs. Nat. Commun. 10, 1613. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09496-0

Yadav, M., Dubey, M. K., and Upadhyay, R. S. (2021). Systemic resistance in chilli pepper against anthracnose (caused by Colletotrichum truncatum) induced by Trichoderma harzianum, Trichoderma asperellum and Paenibacillus dendritiformis. J. Fungi (Basel) 7, 307. doi: 10.3390/jof7040307

Yassin, M., Ton, J., Rolfe, S. A., Valentine, T. A., Cromey, M., Holden, N., et al. (2021). The rise, fall and resurrection of chemical-induced resistance agents. Pest Manag. Sci. 77, 3900–3909. doi: 10.1002/ps.6370

Yu, X., Feng, B., He, P., and Shan, L. (2017). From chaos to harmony: responses and signaling upon microbial pattern recognition. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 55, 109–137. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-080516-035649

Yu, Y., Gui, Y., Li, Z., Jiang, C., Guo, J., and Niu, D. (2022). Induced systemic resistance for improving plant immunity by beneficial microbes. Plants (Basel) 11, 386. doi: 10.3390/plants11030386

Yuan, M., Jiang, Z., Bi, G., Nomura, K., Liu, M., Wang, Y., et al. (2021a). Pattern-recognition receptors are required for NLR-mediated plant immunity. Nature 592, 105–109. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03316-6

Yuan, M., Ngou, B., Ding, P., and Xin, X. F. (2021b). PTI-ETI crosstalk: an integrative view of plant immunity. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 62:102030. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2021.102030

Zhang, X., Yazaki, J., Sundaresan, A., Cokus, S., Chan, S. W., Chen, H., et al. (2006). Genome-wide high-resolution mapping and functional analysis of DNA methylation in Arabidopsis. Cell 126, 1189–1201. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.08.003

Zhi, P., and Chang, C. (2021). Exploiting epigenetic variations for crop disease resistance improvement. Front. Plant Sci. 12:692328. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.692328

Zhou, M., and Wang, W. (2018). Recent advances in synthetic chemical inducers of plant immunity. Front. Plant Sci. 9:1613. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.01613

Zhou, J. M., and Zhang, Y. (2020). Plant immunity: danger perception and signaling. Cell 181, 978–989. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.04.028

Zhou, W., Zhu, Y., Dong, A., and Shen, W. H. (2015). Histone H2A/H2B chaperones: from molecules to chromatin-based functions in plant growth and development. Plant J. 83, 78–95. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12830

Keywords: seed priming, immune memory, epigenetics, disease resistance, crop protection

Citation: Yang Z, Zhi P and Chang C (2022) Priming seeds for the future: Plant immune memory and application in crop protection. Front. Plant Sci. 13:961840. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.961840

Received: 05 June 2022; Accepted: 13 July 2022;

Published: 29 July 2022.

Edited by:

Ho Won Jung, Dong-A University, South KoreaReviewed by:

Damar Lopez-Arredondo, Texas Tech University, United StatesCopyright © 2022 Yang, Zhi and Chang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Cheng Chang, Y2NAcWR1LmVkdS5jbg==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.