- 1Small Grains and Potato Germplasm Research Unit, USDA-ARS, Aberdeen, ID, United States

- 2Wheat Health, Genetics, and Quality Research Unit, USDA-ARS, Pullman, WA, United States

Mutator-like transposable elements (MULEs) represent a unique superfamily of DNA transposons as they can capture host genes and cause higher frequency of mutations in some eukaryotes. Despite their essential roles in plant evolution and functional genomics, MULEs are not fully understood yet in many important crops including barley (Hordeum vulgare). In this study, we analyzed the barley genome and identified a new mutator transposon Hvu_Abermu. This transposon is present at extremely high copy number in barley and shows unusual structure as it contains three open reading frames (ORFs) including one ORF (ORF1) encoding mutator transposase protein and one ORF (ORFR) showing opposite transcriptional orientation. We identified homologous sequences of Hvu_Abermu in both monocots and dicots and grouped them into a large mutator family named Abermu. Abermu transposons from different species share significant sequence identity, but they exhibit distinct sequence structures. Unlike the transposase proteins which are highly conserved between Abermu transposons from different organisms, the ORFR-encoded proteins are quite different from distant species. Phylogenetic analysis indicated that Abermu transposons shared closer evolutionary relationships with the maize MuDR transposon than other reported MULEs. We also found phylogenetic incongruence for the Abermu transposons identified in rice and its wild species implying the possibility of horizontal transfer of transposon. Further comparison indicated that over 200 barley genes contain Abermu-related sequences. We analyzed the barley pan genomes and detected polymorphic Hvu_Abermu transposons between the sequenced 23 wild and cultivated barley genomes. Our efforts identified a novel mutator transposon and revealed its recent transposition activity, which may help to develop genetic tools for barley and other crops.

Introduction

Transposons or transposable elements (TEs) are mobile DNA sequences that have the capability to move from one location to another in genome(s). Transposons may induce harmful even lethal mutations that affect host fitness including some genetic diseases in humans (Payer and Burns, 2019). However, they may also cause chromosomal recombination, form new genes, and change gene expression. Therefore, transposons are considered an important driving force in gene and genome evolution (Kazazian, 2004). Transposons are classified into two major classes based on their transposition mechanisms and sequence structures. Class I elements or RNA retrotransposons mobilize via a copy-and-paste model and have the potential to dramatically increase copy number, whereas class II elements or DNA transposons transpose via multiple mechanisms including cut-and-paste, rolling circle replication and self-synthesizing transposition (Kapitonov and Jurka, 2006). Both class I and II elements can be further grouped into autonomous and non-autonomous transposons. The former are usually intact elements and encode necessary protein(s) for transposition, whereas the latter mostly contain internal deletions or accumulated mutations, do not generate functional transposases and their movement is catalyzed by the autonomous partners.

The mutator-like transposable elements (MULEs) are one major superfamily of DNA transposons, they were originally discovered in maize (Zea mays; Robertson, 1978) and have since been found in a very wide range of organisms including plants, animals, fungi and diatoms (Chalvet et al., 2003; Feschotte and Pritham, 2007). Typical MULEs contain relative long (can be over 300-bp) terminal inverted repeats (TIRs) and generate target site duplications (TSDs) of 7–12 bp (Yu et al., 2000). It has been revealed that some MULEs called Pack-MULEs have captured functional genes or fragments of expressed genes in both plants and animals (Yu et al., 2000; Jiang et al., 2004; Tan et al., 2021). In some cases, a Pack-MULE can contain fragments from multiple genes that may form new open reading frames (ORFs) and play unique roles in gene evolution (Jiang et al., 2004). Additionally, mutator elements may represent the most mutagenic plant transposons identified thus far as they insert into the maize genome at very high frequency (Lisch, 2002). Therefore, mutator transposons provide valuable resources for developing genetic tools to mutate genes and understand their molecular functions (Fernandes et al., 2004).

Although MULEs are widely present in eukaryotes, the vast majority of these elements were inactive and silent in host genomes due primarily to mutations, deletions and/or the epigenetic regulations on transposons (Singer et al., 2001; Lisch, 2009). Thus far, only a handful of active mutators have been identified including Hop in the fungus Fusarium oxysporum (Chalvet et al., 2003), Os3378 in rice (Oryza sativa; Gao, 2012), Muta1 in mosquito (Aedes aegypti; Liu and Wessler, 2017) and three elements in maize, Mu9/MuDR (Hershberger et al., 1991), Jittery (Xu et al., 2004) and Mu13 (Tan et al., 2011). Except Mu13, all these active MULEs are autonomous transposons, but they show different sequence features. Hop, Os3378, Muta1 and Jittery only have one gene encoding mutator transposase protein (Chalvet et al., 2003; Xu et al., 2004; Gao, 2012; Liu and Wessler, 2017). However, the MuDR transposon contains two genes including mudrA encoding the transposase MURA and mudrB encoding the help protein MURB (Lisch, 2002). Impressively, both Os3378 and Muta1 were able to transpose in yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae; Zhao et al., 2015; Liu and Wessler, 2017) suggesting their potential applications in distantly related species and the complex transposition and regulation mechanisms of MULEs. To better understand the evolution and transposition mechanisms of MULEs and to develop new resources for plant functional genetics, it is important to identify more new MULEs.

Barley (Hordeum vulgare, 2n = 2X = 14) is an important food and feed crop grown in a wide range of areas spanning from temperate to tropical climates. It has been cultivated for about 10,000 years and is one of the first domesticated crops (Badr et al., 2000). Barley belongs to the Triticeae tribe of the grass family which also contains bread wheat (Triticum aestivum, 2n = 6X = 42). Due to its diploid genome structure, close evolutionary relationships with the polyploidy wheat, and other unique features, barley has emerged as a model system for characterizing molecular functions of agronomically important genes in cereal crops (Carciofi et al., 2012). Thus far, over 20 genomes of cultivated barley and its wild progenitor, Hordeum spontaneum, have been sequenced and high repetitive fractions (over 80%) were detected in these genomes (Mascher et al., 2017; Jayakodi et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2020; Schreiber et al., 2020; Zeng et al., 2020; Xu et al., 2021). MULEs were identified in both cultivated and wild barley genomes (Mascher et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2020; Xu et al., 2021). However, the transposition and evolution of mutator transposons in barley is still poorly understood. In this study, we comparatively analyzed the barley genomes, discovered a new mutator transposon and investigated its transposition activity and evolution.

Materials and Methods

Plant Materials

A total of 11 cultivated barley varieties/landraces and five wild barley (H. spontaneum) accessions were collected in this study. The detailed information about the collected materials is shown in Supplementary Table 1. Five seeds for each genotype were planted, and the seedlings were grown in the greenhouse at the ARS Small Grains and Potato Germplasm Research Unit in Aberdeen, Idaho. The young leaves were collected from about 3-week seedlings, ground in extraction buffer with the 2010 Geno/Grinder (SPEX SamplePrep, Metuchen, NJ), and genomic DNA was extracted using the cetyltrimethyl ammonium bromide (CTAB) method (Doyle, 1990).

Transposon Annotation

To identify MULEs in barley, the MURA transposase protein in maize (accession no. AAA21566) was first used to search against the barley full-length cDNAs (FLcDNAs) database (Matsumoto et al., 2011), the significant hits (E-value <1 × e−10) then served as the queries to conduct BLASTN searches against the version 2 pseudomolecules_assembly1 of the six-row malting barley cultivar “Morex” (Mascher et al., 2017), hereafter referred to as the barley reference genome. The significant hits and their 20-Kb flanking sequences (10-kb for each side) were extracted and used to define complete mutator transposons based on the terminal inverted repeats and target site duplications. The complete mutator element identified in barley was then used to search against GenBank and find homologous transposons in other genomes. We combined two approaches for predicting transposon structures and transposase proteins: (1) the internal region of each complete transposon was annotated by Fgenesh (Solovyev et al., 2006) and GENSCAN (Burge and Karlin, 1997); and (2) the internal region was also used to conduct BLASTX search and to predict the gene structures based on the homologous proteins deposited in GenBank. In addition, we also searched against the rice genome annotation database2 and other public genome annotation websites to gain more insights into the transposon structures.

Detection of Polymorphic Transposons

The representative 8,176-bp complete transposon was applied to screen the barley reference genome (Mascher et al., 2017) with RepeatMasker program3 using the default parameters. The “nolow” option was selected to avoid masking the low-complexity DNA. All hits were manually inspected to identify complete transposons and typical derivative elements and determine their exact boundaries based on the TIRs, flanking TSDs and sequence comparisons with the representative element. The 600-bp flanking sequence (300-bp for each side) for each transposon with well-defined boundaries was used to search against the genomes of 20 cultivated barley varieties and two wild barley accessions (Liu et al., 2020; Jayakodi et al., 2020; Schreiber et al., 2020; Zeng et al., 2020; Xu et al., 2021) and to detect its presence/absence in other 22 barley genomes based on the sequence alignment.

Identification of Mutator-Related Genes and Sequence Alignment

The barley reference genome and the gene annotations (GFF3 file; Mascher et al., 2017) were used to extract the full gene sequences including both exons and introns with the bedtools package.4 The representative complete element was used to search against both CDS database and the extracted gene sequences in barley to detect if any genes contain transposon-related sequences. All significant hits (E-value < 1 × e−10) were then manually inspected, and the redundant hits were removed.

To compare the transposon-related gene in barley with the orthologous regions in wild barley and bread wheat, the gene and the 20-Kb flanking region were extracted and used to conduct BLASTN searches against the corresponding regions in the wild species and wheat with the default options, except that we applied the output eight format. The sequence alignments were conducted with the Artemis Comparison Tool (ACT) program.5

Estimation of Non-synonymous and Synonymous Substitution Rates

The protein sequences of mutator transposons and alcohol dehydrogenases 1 (ADH1) were aligned with ClustalW using MEGA11 software (Tamura et al., 2021), and the alignment of multiple protein sequences and the cDNA sequences were used to calculate the number of non-synonymous substitutions per non-synonymous site (Ka) and the number of synonymous substitutions per synonymous site (Ks) using the PAL2NAL program (Suyama et al., 2006). The ADH1 protein (accession no. ADH03830.1) in cultivated rice (Oryza sativa) was used as a query to search against GenBank and identify homologous sequences in other Oryza species.

PCR Validation of Polymorphic Transposons

Both transposons and their flanking sequences (300-bp for each side) were obtained from the Morex genome and used to design primers with the Primer3 program (Untergasser et al., 2012). The designed primers (Supplementary Table 2) were synthesized by the Eurofins Genomics LLC (Louisville, KY, United States) and applied for PCR analysis. PCR amplifications were conducted in a Bio-Rad S1000 Thermal Cycler in 20 μl reactions consisting of ~50 ng of genomic DNA, 0.2 mM primer, deionized water, and 10 μl EconoTaq PLUS GREEN 2X Master Mix (Middleton, WI, United States) containing 0.1 units/μl of EconoTaq DNA Polymerase, Reaction Buffer (pH 9.0), 400 μM dATP, 400 μM dGTP, 400 μM dCTP, 400 μM dATP, and 3 mM MgCl2. The PCR temperature cycling conditions were 1 cycle of 98°C for 2 min; 35 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, 72°C for 30 s; and 1 cycle of 72°C for 5 min. Amplification products were run on 0.8% agarose gels and stained with ethidium bromide.

Construction of Phylogenetic Trees

Both conserved domains and entire protein sequences of mutator transposases were aligned using ClustalW program with default options and the ambiguous regions were trimmed. The alignments of multiple sequences were then used to generate evolutionary trees with software MEGA11 (Tamura et al., 2021) using the neighbor-joining method. The phylogenetic analysis was performed based on 1,000 bootstrap replicates.

Results

Identification of a New Mutator Transposon

To identify putative transcriptional mutator transposons in barley, the maize MuDR transposase protein, MURA, was used as a query to search against the barley full-length (FL) cDNA database (Matsumoto et al., 2011). Eight significant hits (E-value <1 × e−26) were found and a FLcDNA sequence (accession no. AK251670) stood out as it showed the lowest E-value (6 × e−82). AK251670 was then used to search against the barley genome sequences (Mascher et al., 2017) and to find complete mutator transposons according to the TIRs and TSDs. An 8,176-bp transposon was identified, sequence searches indicated that its DNA exhibited no significant identity to any described MULEs. We named the new element Hvu_Abermu. This element contains the TIRs of 138–145 bp and is flanked by 9-bp TSD. The relative long TIRs and 9-bp TSD are similar to the typical features of other MULEs including Hop (Chalvet et al., 2003), Os3378 (Gao, 2012), MuDR (Hershberger et al., 1991), Jittery (Xu et al., 2004) and Mu13 (Tan et al., 2011). However, Hvu_Abermu was much larger than these MULEs that ranged in size from 1,495 bp (Mu13) to 4,942 bp (Os3378).

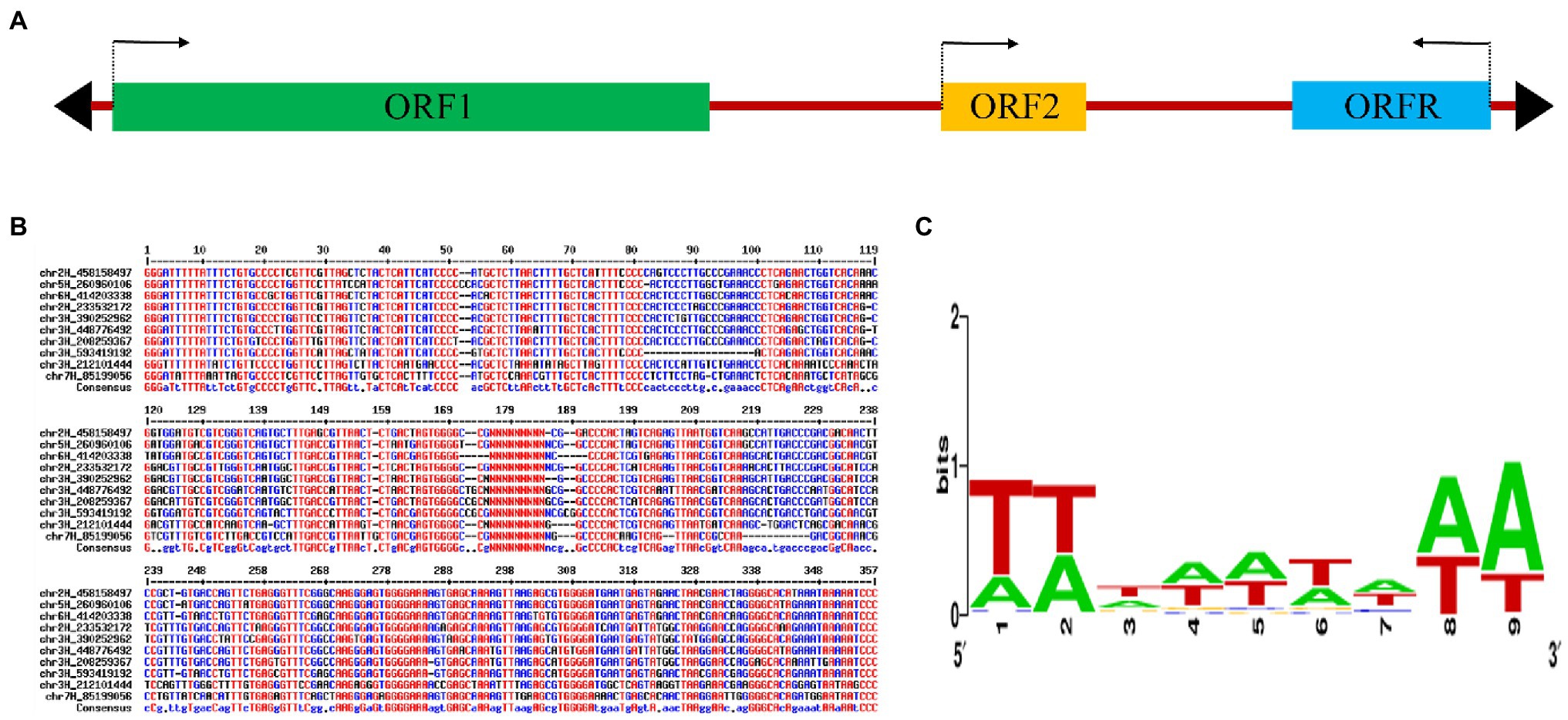

The typical MuDR transposon contains two genes with transcription occurring in opposite directions, whereas many other autonomous MULEs only have one gene encoding mutator transposase protein. Impressively, Hvu_Abermu contains three open reading frames (ORFs), and the first two ORFs, ORF1 and ORF2, showed the same direction of transcription. However, the third ORF, ORFR, is transcribed in the opposite orientation compared to ORF1 and ORF2 (Figure 1A). The 826-aa protein encoded by ORF1 exhibited significant sequence similarity to MURA (E-value = 2 × e−62) and other mutator transposase proteins. Significant hits (E-value <1 × e−10) of ORF2 were identified in barley, wheat, Brachypodium distachyon, Dichanthelium oligosanthes, Panicum virgatum and wild relatives of wheat. However, the function of ORF2-coding protein is not clear. Despite both mudrB of maize MuDR transposon and the ORFR of Hvu_Abermu showed opposite direction of transcription to the ORF encoding mutator transposase, they shared no sequence identity at nucleotide or protein levels. Since the protein encoded by ORF1 of Hvu_Abermu shows similar size to MURA, and also contains complete transposase domains including DDE and zinc finger (ZnF) that are essential for catalyzing mutator transposition, Hvu_Abermu is likely an autonomous MULE.

Figure 1. A mutator transposon in barley. (A) The sequence structure of Hvu_Abermu. Colorful rectangles and black triangles represent the open reading frames (ORFs) and terminal inverted repeats (TIRs) of the transposon and the arrows indicate the transcription orientations. (B) Sequence alignment of 5′ and 3′ TIRs of 10 Hvu_Abermu transposons. The internal regions of transposons are indicated by 20 Ns. (C) WebLogo of 9-bp TSDs of 267 Hvu_Abermu elements in barley.

High Copy Number and Insertion Preference

Like other DNA transposons that mobilize with a cut-and-paste mechanism, many mutator families are present at low copy number in host genomes. For example, the Jittery transposon is present in maize inbred lines at zero to two copies (Xu et al., 2004). The barley reference genome was screened using RepeatMasker and identified 11,430 repeats including both complete elements and deletion derivatives. Usually, one repeat including the fragmental element caused by insertion or deletion can be counted as one copy of Hvu_Abermu. However, in some cases (less than 10% occurrence), one transposon was split into two or more repeats. Thus, we estimated there are about 10,000 Hvu_Abermu copies in the barley genome including complete transposons, truncated elements, or fragmental sequences derived from Hvu_Abermu. It is worth noting that this number may be underestimated as the barley genome is highly repetitive and about 5% of the genome sequences were not assembled into the reference genome (Mascher et al., 2017).

The Hvu_Abermu sequences and the flanking regions were subsequently manually inspected. The vast majority of these elements were fragmented and lacked TIRs and TSDs. However, the exact boundaries for 278 Hvu_Abermu transposons were identified based on their TIRs and TSDs including 267 elements flanked by 9-bp TSDs, 10 elements surrounded by 8-bp TSDs and one transposon flanked by 10-bp TSDs. No TSD was found for six Hvu_Abermu transposons, but their boundaries can be clearly determined by the conserved 5′GGG…CCC3′ terminal motifs of Hvu_Abermu elements (Figure 1B) and sequence comparisons with the 8,176-bp reference Hvu_Abermu suggesting that either the TSDs have undergone dramatic mutations and cannot be recognized, or their insertions did not generate TSD as some MULEs did (Liu and Wessler, 2017). Our sequence inspection indicates that Hvu_Abermu frequently generated 9-bp TSDs when they integrated into the barley genome. The flanking 9-bp TSDs of the 267 Hvu_Abermu transposons were extracted and aligned, the multiple sequence alignments suggest that the Hvu_Abermu transposons preferentially insert into TA-rich regions (Figure 1C).

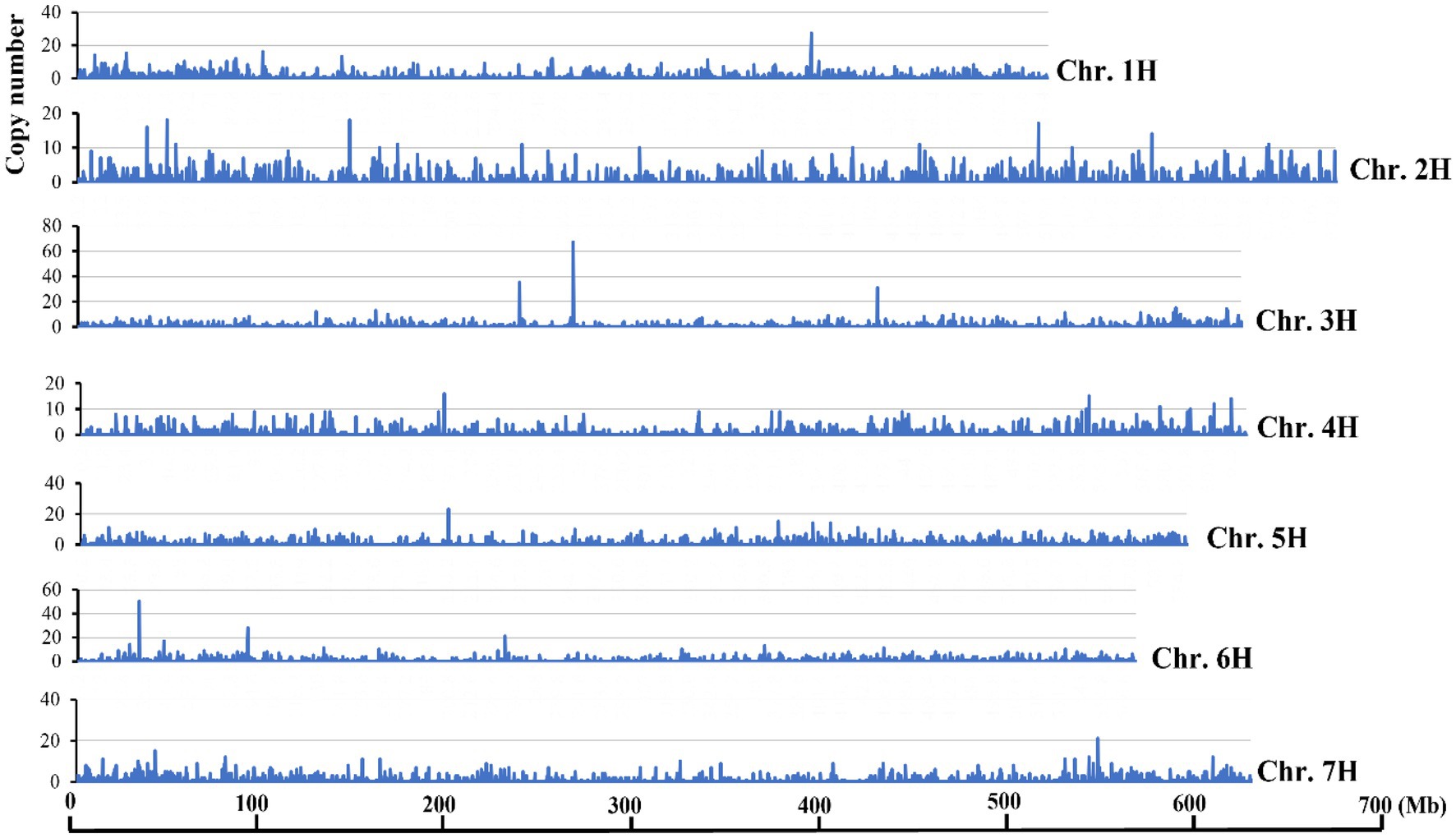

Transposons showed uneven distributions across the barley genome and the chromosome termini have accumulated/retained more DNA transposon sequences than other regions (Mascher et al., 2017). To test if Hvu_Abermu transposons showed similar trends, the copy numbers for each 200-Kb window was counted and along with the estimated density of Hvu_Abermu elements. The results indicate that Hvu_Abermu transposons were dispersed across the barley genome and no higher density of transposons was detected in the terminal regions of seven barley chromosomes (Figure 2). However, variable densities among the seven chromosomes were observed. The average transposon density was 2.65 Hvu_Abermus per Mb sequence for the seven chromosomes. Chromosome 1 had the highest density (2.85 transposons/Mb), whereas chromosome 4 had the lowest density (2.18 transposons/Mb).

Abermu Family Transposons are Present in Both Monocots and Dicots

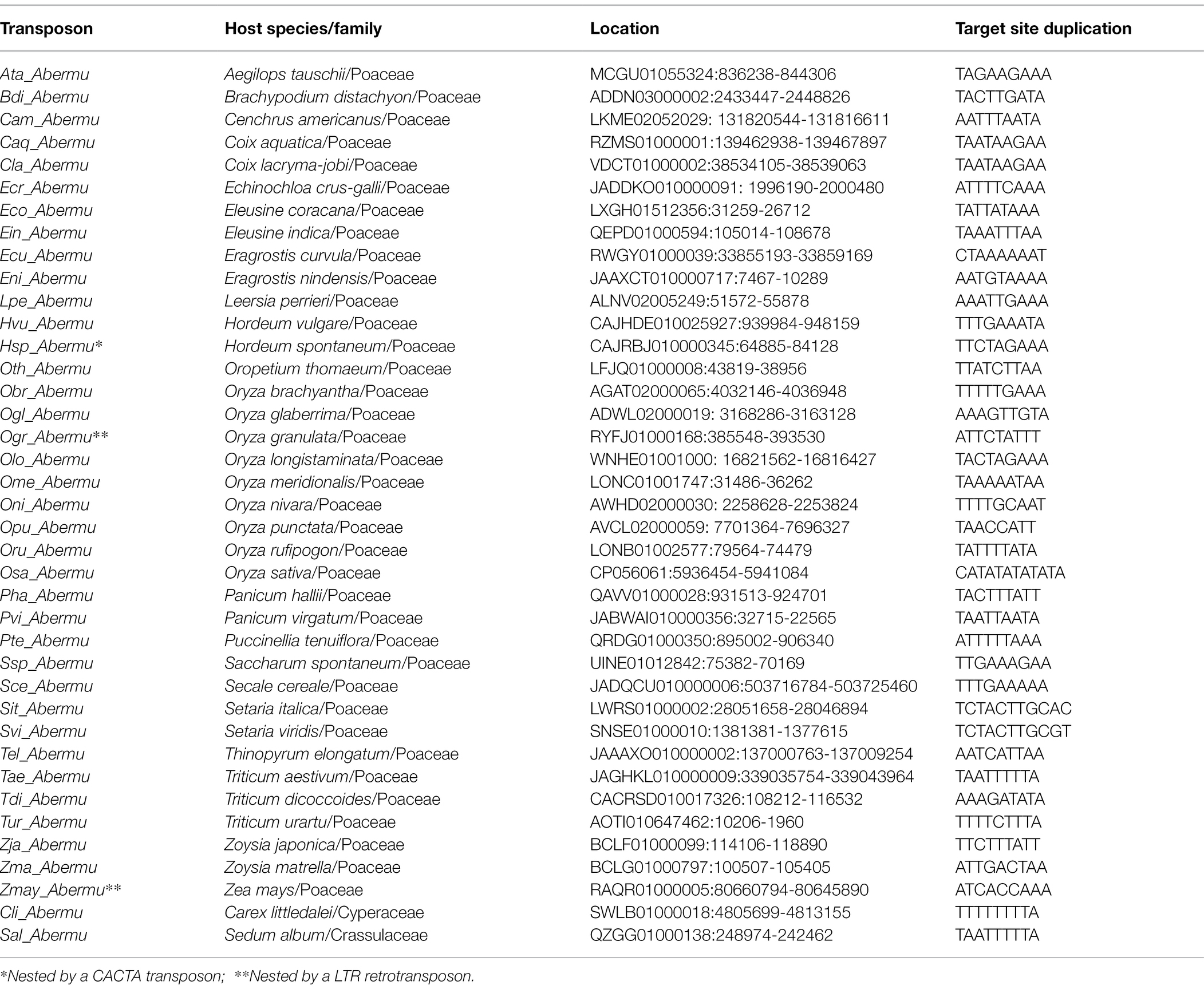

Transposons are genomic sequences that evolve very rapidly (Fedoroff, 2012). Therefore, homologous transposons are difficult to identify in distantly relative species (Gao et al., 2009). To detect if the homologous sequences of Hvu_Abermu are present in other genomes, GenBank was searched with the 8,176-bp Hvu_Abermu sequence. Significant hits were identified in 71 flowering plants (Angiosperms) including 66 monocots and five dicots, but no homolog was found in other main divisions of land plants. The hit sequences and their 20-Kb flanking regions (10Kb for each side) were extracted and manually inspected. We identified complete transposons in 38 flowering plants including 36 species of the family Poaceae, one non-grass monocot (Carex littledalei) and one dicot (Sedum album; Table 1). As these elements shared significant sequence identity to Hvu_Abermu and between each other, Hvu_Abermu and the homologous transposons were grouped into the same family called Abermu.

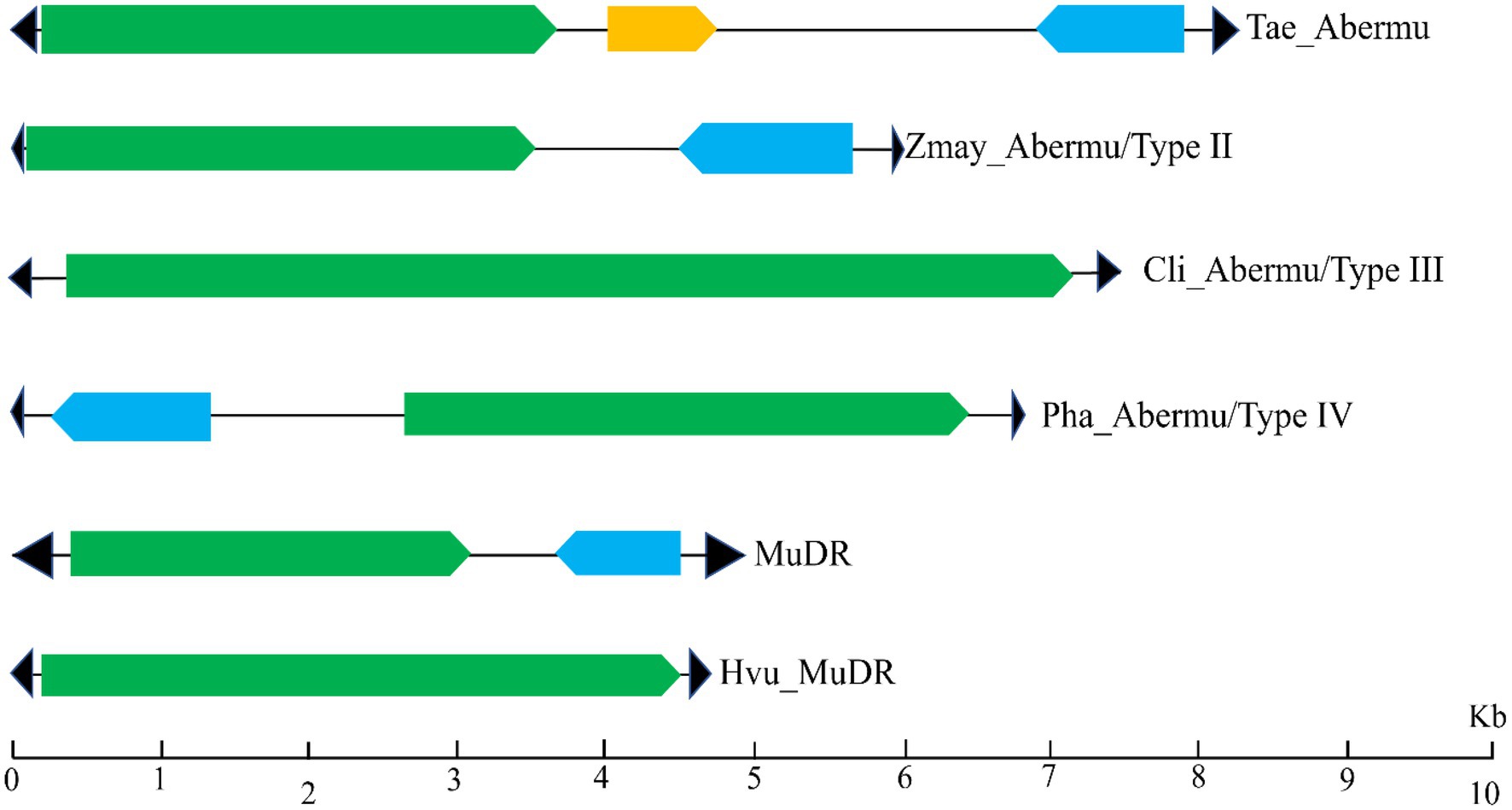

To test if Abermu elements in other plants exhibit similar structures with Hvu_Abermu, we annotated the representative elements in the 38 plants (Table 1) using Fgenesh (Solovyev et al., 2006) and GENSCAN (Burge and Karlin, 1997). These elements showed distinct structures that can be grouped into four types (Figure 3). The Type I Abermu elements showed the same structure as Hvu_Abermu, and their internal regions contain three ORFs. These transposons were only identified in the tribes Triticeae and Poeae including common wheat (Triticum aestivum, Tae_Abermu), Aegilops tauschii (Ata_Abermu), wild emmer wheat (Triticum dicoccoides, Tdi_Abermu), Aegilops tauschii (Ata_Abermu), Hordeum spontaneum (Hsp_Aberm) and Puccinellia tenuiflora (Pte_Abermu). The type II transposons which have two ORFs, the first ORF (ORF1) encodes mutator transposase protein, and the second ORF (ORFR) showed the opposite transcription direction to ORF1 and was located between ORF1 and 3′ TIR of the transposon. The type II Abermus were found in 13 plants including maize (Zea mays, Zmay_Abermu), two Coix species, four Oryza species and three plants of the tribe Triticeae, rye (Secale cereale, Sce_Abermu), Triticum urartu (Tur_Abermu) and Thinopyrum elongatum (Tel_Abermu). The type III transposons only have one ORF encoding mutator transposase, this type of Abermu was discovered in 17 plants including five Oryza species, two Eragrostis species, two Setaria species and two non-grass plants, Carex littledalei and Sedum album. In addition, we also found that Abermus in three plants, Panicum hallii (Pha_Abermu), Panicum virgatum (Pvu_Abermu) and Brachypodium distachyon (Bdi_Abermu), showed structures that were different from the three types above. For example, Pha_Abermu contains an opposite ORF (ORFR) located between 5′ TIR and the transposase-encoded ORF (ORF1).

Figure 3. The sequence structures of different types of Abermu transposons and MuDR elements. The black triangles represent the TIRs of transposons. The green rectangles represent the ORF (ORF1) encoding mutator transposase protein, the blue rectangles indicate that ORF (ORFR) showing opposite orientation of transcription and the orange rectangle mean the second ORF that has the same transcription orientation with ORF1.

Divergent ORFR Sequences

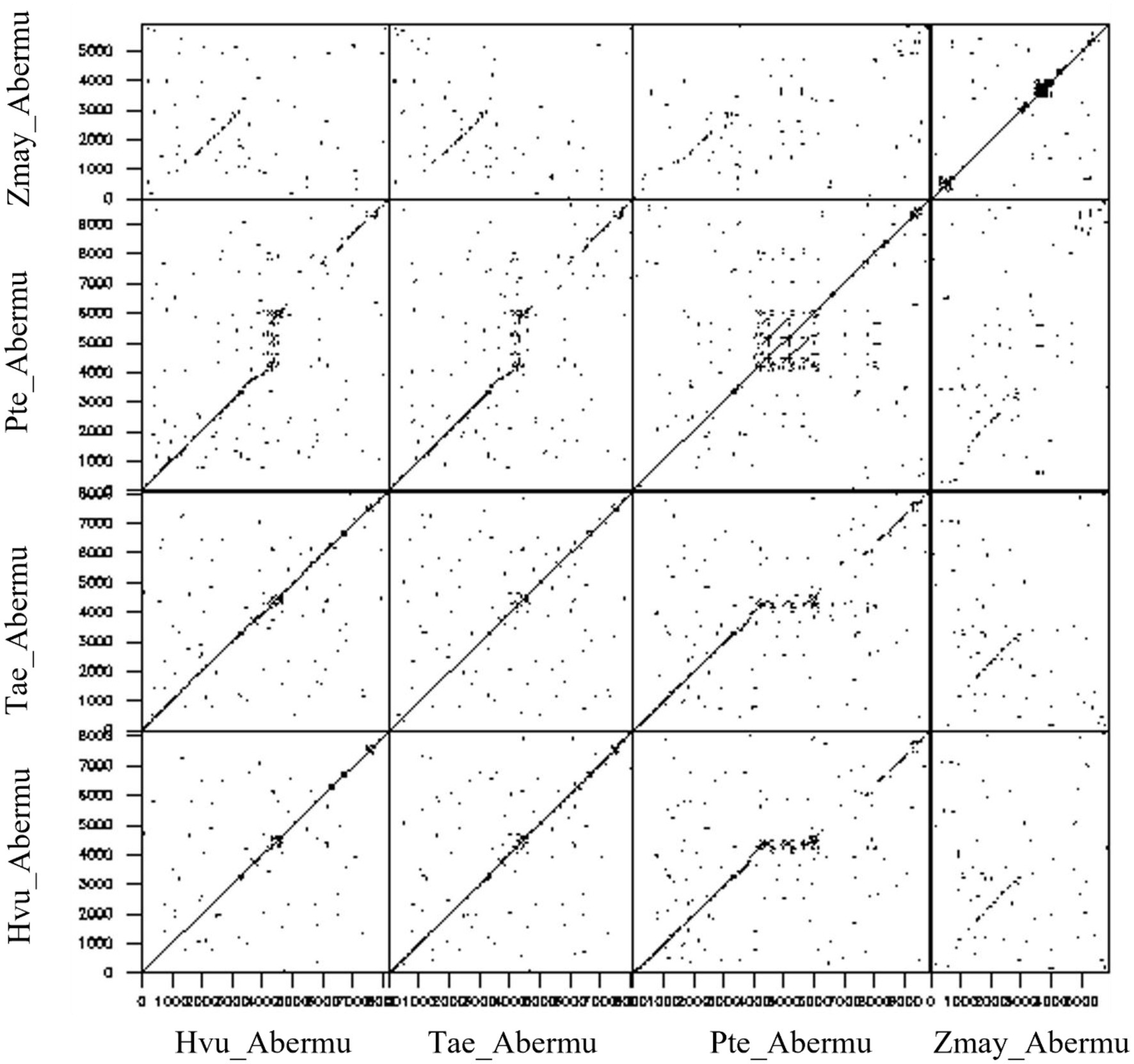

We further compared the Abermu elements that contain both ORFR and the ORF encoding mutator transposase (ORF1) to gain clues about their sequence divergence and relationships. Our sequence comparisons indicated that the ORF1 regions of these Abermu transposons showed significant sequence identity between each other. However, the ORFR regions were very dynamic, and no sequence similarity was detected for some elements. For example, the ORFR sequence of Hvu_Abermu only shared similarity with the Abermus identified in the Triticeae and Poeae including Tae_Abermu, Sce_Abermu and Pte_Abermu but lacked detectable similarity with the ORFRs of Zmay_Abermu (Figure 4) and the elements identified in Oryza and other genomes. Thus, these comparisons suggested that the ORFR sequences tended to be less conserved than the ORF1 regions. In maize, Zmay_Abermu exhibited similar structure with MuDR transposon (Figure 3). However, the DNA sequence of Zmay_Abermu shared no sequence identity to MuDR, implying that they have diverged from an ancestor mutator for a long evolutionary period.

Figure 4. Dotplot analysis between Hvu_Abermu and three other Abermu transposons in bread wheat, Puccinellia tenuiflora and maize.

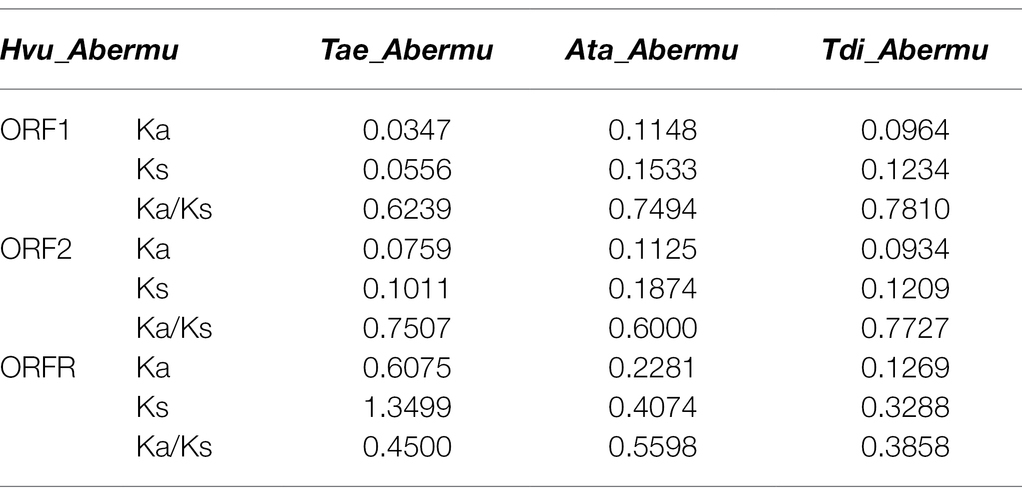

Previous studies revealed that some genomic regions have diverged more rapidly than others as they may have been subjected to different levels of selective pressures (Davidson et al., 2009; Seehausen et al., 2014; Sendell-Price et al., 2020). To gain insight into the sequence divergence of Abermus and test if different ORFs of the transposons have undergone similar levels of selective constraint, the number of non-synonymous substitutions per non-synonymous site (Ka) and synonymous substitutions per synonymous site (Ks) of three ORFs were calculated by comparing Hvu_Abermu with the three Abermu elements in related species. The Ka/Ks ratios for all three ORFs were less than 1 (Table 2) suggesting that they have undergone purifying selection. The Ka and Ks values of three pairs of ORF1 were similar to that of ORF2. However, the Ka and Ks values of ORFR were much higher than both ORF1 and ORF2, and the average Ka and Ks values were three to five times larger than that of ORF1 and ORF2 (Table 2), implying that ORFR regions have likely been subjected to relatively looser selection pressure than ORF1 and ORF2.

Phylogenetic Analysis of Abermu Transposons

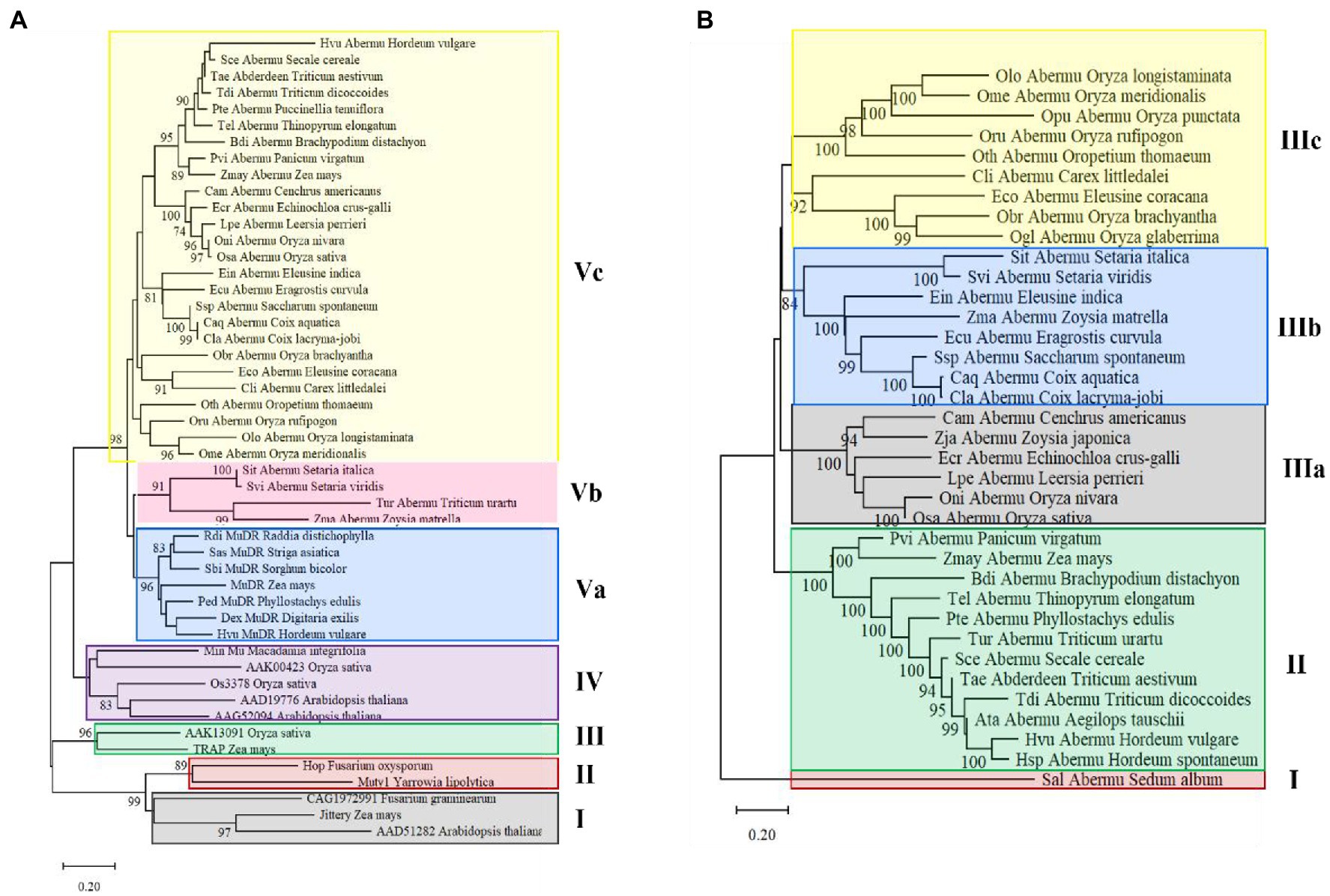

To understand the evolutionary origin of Abermu transposons, phylogenetic analysis was performed using the conserved domain of mutator transposase proteins of 30 complete Abermu elements from different plants (Table 1) and 19 MULEs published or identified in this study (Supplementary Table 3). Eight Abermu transposons listed in Table 1 were excluded from this analysis as their transposases lacked the conserved domain sequences or contained large deletions. The 49 MULEs were grouped into five clades, Jittery, Os3378 and Hop fell into different clades which were distantly related to Abermu transposons (Figure 5A). All Abermu transposons formed two subclades within the clade V sister to the subclade of MuDR-related elements in plants. Thus, Abermu transposons shared closer relationship with MuDR than other reported MULEs. The Abermu transposons identified in closely related species were mostly grouped together, but we found that the Abermus in six Oryza species were distantly separated.

Figure 5. Phylogenetic analysis of Abermu transposons and other mutator elements. (A) The phylogenetic tree made with the conserved domain of mutator transposase. (B) The phylogenetic tree built using whole mutator transposase. The branches with over 70% bootstrap values are marked.

As the conserved domains of the mutator transposase proteins were short [about 100 amino acids (aa)] and may only provide clues about the sequence divergence in the core regions of MULEs but not for the whole encoding regions. Thus, we further generated a phylogenetic tree with the whole transposase proteins of all complete Abermu transposons (Table 1) but Eni_Abermu, Ogr_Abermu and Pha_Abermu as these three encode shorter proteins (<420-aa). Other MULEs including Hop from a fungus was also excluded as their protein sequences were too divergent and can cause problematic alignment regions leading to more biased topologies (Talavera and Castresana, 2007). Sal_Abermu in the dicot Sedum album was separated from all 35 Abermu transposons found in monocots which fell into two clades. All Abermu transposons in the tribes Triticeae and Poeae were grouped into the clade II, and the Abermus in eight Oryza species were grouped into the two subclades of the clade III (Figure 5B). Consistent with the phylogeny of the conserved domains, Cli_Abermus, identified in Carex littledalei of the family Cyperaceae, was closely related to Eco_Abermu in Eleusine coracana that belongs to grass family. Both phylogenetic trees built with the conserved domains and whole transposase proteins indicated the phylogenetic separations and incongruence of Abermus from Oryza species as we found that the Abermu elements in rice and its wild species, O. nivara, showed close phylogenetic relationships to the Abermu from Leersia perrieri which is the outgroup species of the Oryza genus (Stein et al., 2018).

Abermu-Related Genes in Barley

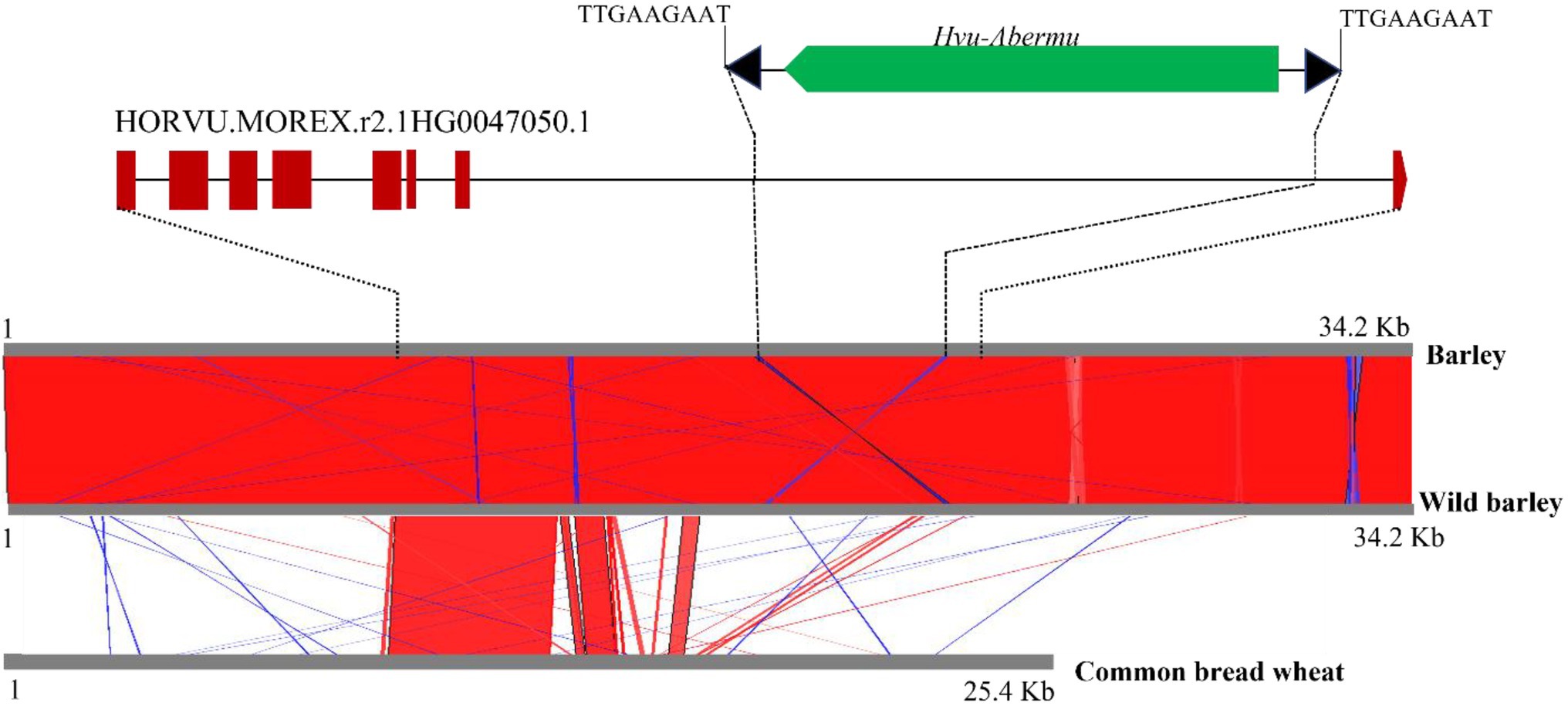

Transposons play important roles in gene evolution and morphological variation (Kazazian, 2004; Ong-Abdullah et al., 2015). Since Abermu elements are very abundant in the barley genome, we wonder if any Abermu elements were involved in gene formations. The annotated genes in the barley genome (Mascher et al., 2017) was searched using the Hvu_Abermu element as the query. The coding DNA sequences (CDSs) of 211 annotated genes showed significant sequence identity (E-value <1 × e−10) to Hvu-Abermu. Among them, seven genes encode mutator transposase protein and another 204 genes encode proteins with various molecular functions including metabolic pathways, disease resistance, and others (Supplementary Tables 4). Furthermore, Hvu-Abermu was found in the intronic regions of seven annotated genes including HORVU.MOREX.r2.1HG0047050.1 that harbors a Hvu-Abermu with partially internal deletion in the seventh intron (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Sequence alignments of the orthologous genes and 20-Kb flanking regions in cultivated and wild barley and bread wheat. Top shows the structure of the barley HORVU.MOREX.r2.1HG0047050.1 gene and the inserted Hvu_Abermu element. The brown rectangles/pentagon represent the exons of the barley gene, and the black solid lines mean introns of the gene. Bottom is the alignments of the orthologous genes and flanking regions. Red means shared sequences showing same orientations and blue means shared regions with reverse.

To gain clues about when this Hvu-Abermu element inserted into the gene, DNA sequence of HORVU.MOREX.r2.1HG0047050.1 and the 20-Kb flanking regions (10-Kb each side) was extracted and searched against the genomes of the wild barley (H. spontaneum) B1K-04-12 (Jayakodi et al., 2020) and the bread wheat (Zhu et al., 2021). The homologous sequences were detected for both the gene including the Hvu-Abermu and the 20-Kb flanking region in wild barley (Figure 6) suggesting that Hvu-Abermu inserted into the barley genome before its domestication occurring about 10,000 years (Badr et al., 2000). Three homologous genes of HORVU.MOREX.r2.1HG0047050.1 were identified in wheat genome, TraesCS1A03G0605600.1, TraesCS1B03G0707700.1 and TraesCS1D03G0582200.1. However, no Abermu sequence was identified within all three genes and the flanking regions, even we searched against their 200-Kb surrounding regions implying that the Hvu-Abermu element likely inserted into ancient wild barley after the divergence of barley and wheat, or the element was also present in the original ancestor of wheat but has excised before the radiation of three diploid wild wheat species (AA, BB, and DD).

Polymorphic Transposons in the Barley Pan Genomes

Potential active transposons can be identified based on the high sequence identity between the family members (Jiang et al., 2003). The complete Hvu-Abermu elements in barley was compared and found that they can share more than 95% sequence identity suggesting that Hvu-Abermu may be an active mutator. To detect its transpositional activity, the 600-bp flanking sequences (300-bp for each side) of the 284 Hvu_Abermu transposons with well-defined boundaries in the reference barley genome from the malting barley cultivar “Morex” (Mascher et al., 2017) were used to search against the genomes of 22 cultivated and wild barley accessions, including 18 cultivated barley genotypes and one accession of wild barley (B1K-04-12) generated by the barley pan-genome project (Jayakodi et al., 2020; Schreiber et al., 2020), one Canadian malting barley cultivar “AAC Synergy” (Xu et al., 2021), one Tibetan hulless barley “Lasa Goumang” (Zeng et al., 2020) and another wild barley accession AWCS276 (WB1; Liu et al., 2020). No hits or multiple highly identical hits were detected for the flanking sequences of 160 Hvu_Abermu transposons suggesting that these Hvu_Abermu elements were either inserted into highly repetitive regions or the flanking regions were not sequenced and/or assembled in the 22 genomes. However, the orthologous regions in the 22 genomes for 124 Hvu_Abermu elements were defined based on the sequence alignments. We found that 121 elements are shared by Morex and other barley genomes indicating that these Hvu_Abermu transposons have been retained in the population before the domestication of cultivated barley. Interestingly, three polymorphic Hvu_Abermu elements were identified that are present in the Morex genome but absent in some wild and barley genomes (Supplementary Table S5). For example, the Hvu_Abermu element located on chr7H (92741435–92758274) in Morex is absent in the wild barley B1K-04-12 and six cultivated barley accessions, HOR_7552, HOR_13942, Igri, OUN333, ZDM01467 and ZDM02064, but it is present in the wild barley WB1 and other 15 cultivated barley materials.

To detect more polymorphic Hvu_Abermu transposons, the 8,176-bp Hvu_Abermu was also used to screen the genomes of “Golden Promise” (Schreiber et al., 2020), “Lasa Goumang” (Zeng et al., 2020) and WB1 (Liu et al., 2020). We identified 278 complete Hvu_Abermu transposons and deletion derivatives with well-defined TIRs in the Golden Promise genome. We have extracted their 600-bp flanking sequences and used to compare with the Morex genome (Mascher et al., 2017). The orthologous loci for 119 Hvu_Abermu elements were identified in the Morex genome. Among them, 118 are shared between “Golden Promise” and “Morex.” However, one transposon (chr2H: 555341970–555347145) in “Golden Promise” is absent in “Morex.” In addition, the flanking sequence for 246 Hvu_Abermus transposons in “Lasa Goumang” was extracted and compared with the Morex genome. We found 108 Hvu_Abermu elements shared by “Lasa Goumang” and “Morex” and two Hvu_Abermu transposons located in the sequences DOW01000362.1 (860851–869592) and SDOW01000553.1 (879368–888197) present in “Lasa Goumang” but absent in “Morex.” In the WB1 genome, we extracted the flanking sequences of 284 Hvu_Abermu elements and searched against the Morex genome and found 117 Hvu_Abermu elements shared between WB1 and “Morex.” One Hvu_Abermu transposon (WB_00002568:81405–90263) is present in WB1 but absent in “Morex.” Taken all together, four Hvu_Abermus transposons were found that are present in one of the three genomes but absent in the Morex genome. We further detected the distributions of these four polymorphic elements in the barley pan genome and found these elements are absent in most of the 23 genomes (Supplementary Table S5).

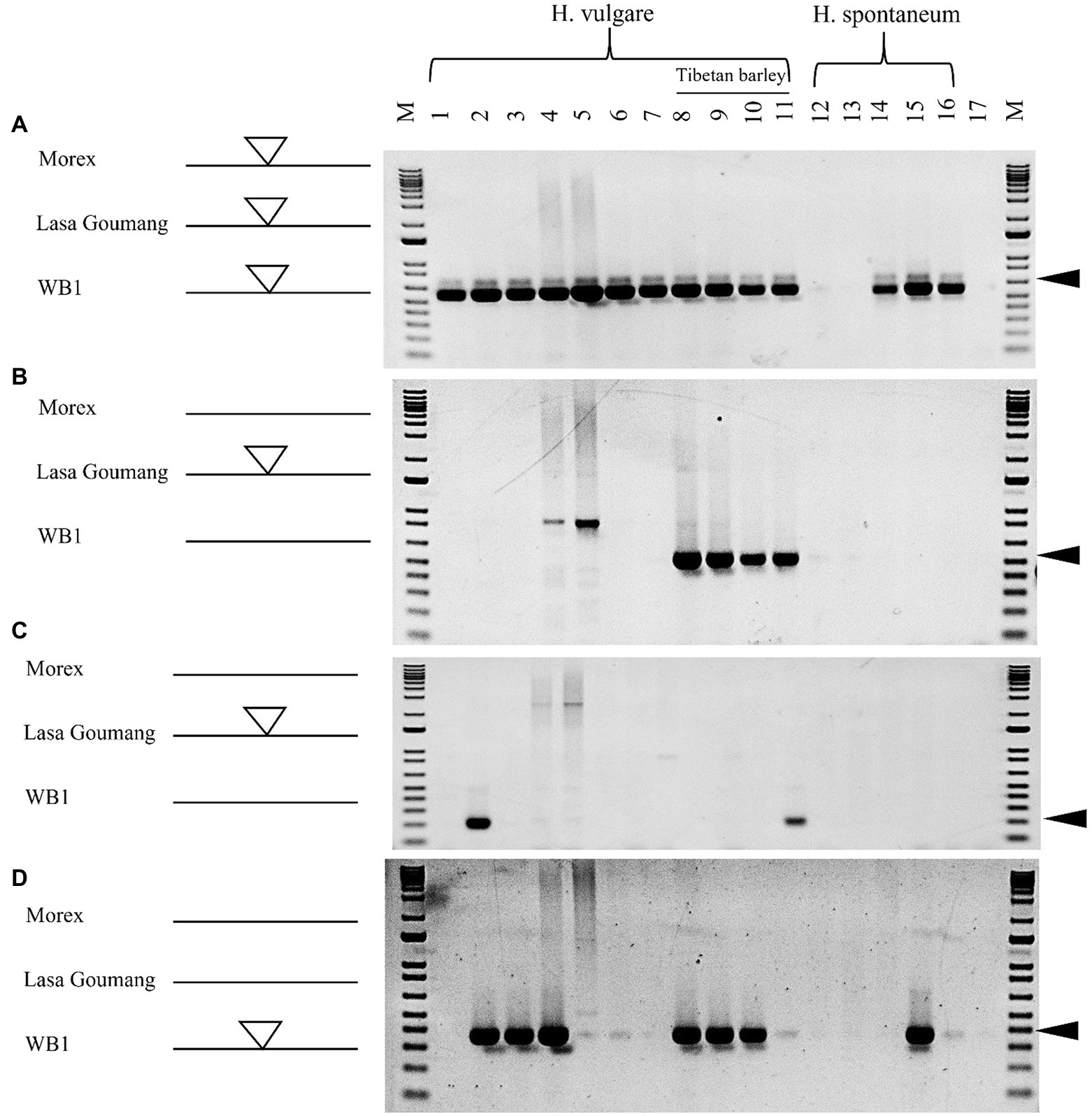

To validate the computational analyses performed, 16 barley genotypes were collected for PCR analysis including “Morex,” “Golden Promise” and other five cultivated barley varieties that genomes have been sequenced by the barley pan-genome and other projects (Jayakodi et al., 2020; Schreiber et al., 2020; Xu et al., 2021). We were not able to obtain the seeds or DNAs for “Lasa Goumang” and two wild barley B1K-04-12 and AWCS276 (WB1) but we collected four Tibetan hulless varieties and five wild barley accessions from the National Small Grains Collection (NSGC) at the USDA (Supplementary Table 1). Four pairs of PCR primers were designed based on the Hvu_Abermu transposons and their flanking sequences. For each pair, one primer targets the flanking sequence, and the other anchors the Hvu_Abermu transposon, thus an expected amplicon will be generated if the transposon is present in the orthologous locus. Using the UAAB5 primers designed with a Hvu_Abermu transposon (chr3H:168627665_168630547) in “Morex,” an expected band was amplified in all 11 cultivated barley varieties and three wild accessions (Figure 7A), which confirmed our sequence analysis that showed this element is shared by “Morex” and the other 22 wild and cultivated barley genomes including “Golden Promise,” “AAC Synergy,” “Lasa Goumang” and the two wild accessions (Supplementary Table S5). Using the UAAB11 primers targeting the polymorphic Hvu_Abermu (DOW01000362.1: 860851–869592) in Lasa Goumang, an amplicon with expected size (530-bp) was only found in four accessions of Tibetan barley (Figure 7B), it was consistent with our genomic comparisons showing that this transposon is present in “Lasa Goumang” but absent in the two wild barley accessions, “Morex” and “Golden Promise.” We also amplified the DNAs of 16 barley samples using the UAAB13 primers targeting a Hvu_Abermus transposon (SDOW01000553.1:879368–888197) in “Lasa Goumang,” the specific band was only amplified in a Tibetan barley (CIho 3,087) and Akashinriki (Figure 7C) that confirmed its presence in “Akashinriki” and absence in “Morex,” “Golden Promise,” “AAC Synergy,” and other barley varieties. Our sequence comparisons identified a Hvu_Abermu (WB_00002568:81405–90263) in the wild barley WB1 and revealed that it is present in “Lasa Goumang,” “Akashinriki,” “Igri,” and “HOR_3081,” but absent in “Morex,” “Golden Promise,” “AAC Synergy,” “Hockett” and the wild barley B1K-04-12 (Supplementary Table S5). Using the UAAB7 primers targeting this polymorphic element in WB1 and its flaking region, an expected PCR band was amplified in “Akashinriki,” “Igri,” “HOR_3081,” three Tibetan barley accessions and one wild barley (PI 282588) but no band was amplified in “Morex,” “Golden Promise” and other two (Figure 7D). Our PCR experiment revealed polymorphic Hvu_Abermu transposons in 16 wild and cultivated barley accessions and the results exactly matched the presence/absence of the Hvu_Abermu transposons in the seven non-Tibetan barley varieties identified by our computational analysis. For the four Tibetan barley varieties and five wild barley accessions, the absence of transposons may need to be further validated with sequencing data as point mutations and other factors can cause the failure of PCR amplification.

Figure 7. PCR analysis of 16 barley genotypes using the primers of UAAB5 (A), UAAB11 (B), UAAB13 (C), and UAAB7 (D). M means the 1-Kb plus DNA ladder. One to eleven represent 11 cultivated barley genotypes, 1: Morex; 2: Akashinriki; 3: Igri; 4: HOR_3081(Slaski); 5: Golden Promise; 6: Hockett; 7: AAC Synergy; 8: Qingki; 9: Tibetan (PI 506343); 10: Tibetan (PI 195542); 11: Tibetan (CIho 3,087), and the 12–16 indicated five wild barley accessions, 12: PI 282572; 13: PI 282574; 14: PI 282575; 15: PI 282588 and 16: PI 282593. Seventeen is a negative control and no DNA template was added for PCR amplification. The white and bigger triangles represent the inserted transposons in the left side, and the black and smaller triangles in the right side mean the expected sizes of amplifications.

Discussion

A New and Unusual MULE

In this study, a new mutator family Abermu was identified. Unlike other MULEs, Abermu transposons exhibit several unusual features in barley and its relatives. First, they are larger (over 8 Kb) and contain three ORFs including two extra ORFs with unknown functions, this type of transposon was not reported before. Second, they are present at extremely high copy numbers. We estimated that there are about 10,000 Abermu repeats in the barley genome and over 30,000 copies in the common wheat. MULEs transpose through a cut-and-paste mechanism and usually do not increase their copy numbers. It is not clear how Abermu transposons reached such high copies in the cereals. In Drosophila, the P elements can quickly increase their copy number via the gap repair mechanism or inserted into the chromosomes during S phase of meiosis (Spradling et al., 2011). Third, the insertion preference. Previous studies indicated that mutator transposons preferentially insert into genes in maize (Cresse et al., 1995; Fernandes et al., 2004). Our analysis suggests that Abermu are frequently inserted into TA-rich regions (Figure 1C). It seems that TA-rich regions play critical roles in plant gene expression as they may harbor the TATA box of promoters or other core motifs for gene regulation (Forde et al., 1990). Fourth, they demonstrated a possible higher retention rate. Transposon insertions may cause deleterious mutations and affect the host fitness, especially for the transposons with large sizes (Petrov et al., 2003). Therefore, transposons showed high turnover rates and can be quickly removed from the host genome. Genome-wide comparisons indicated that only 17 to 25% of full-length LTR in the wild barley B1K-04-12 are shared with the domesticated barley genotypes (Jayakodi et al., 2020). We analyzed the barley pan genomes and found that 98% (121/124*100) of complete Abermu elements are shared between two wild barley accessions and 21 cultivated barley genotypes (Supplementary Table S5). The retention rate of Abermu is three times or higher than the LTR retroelements.

Complex Evolution of Abermu Transposons

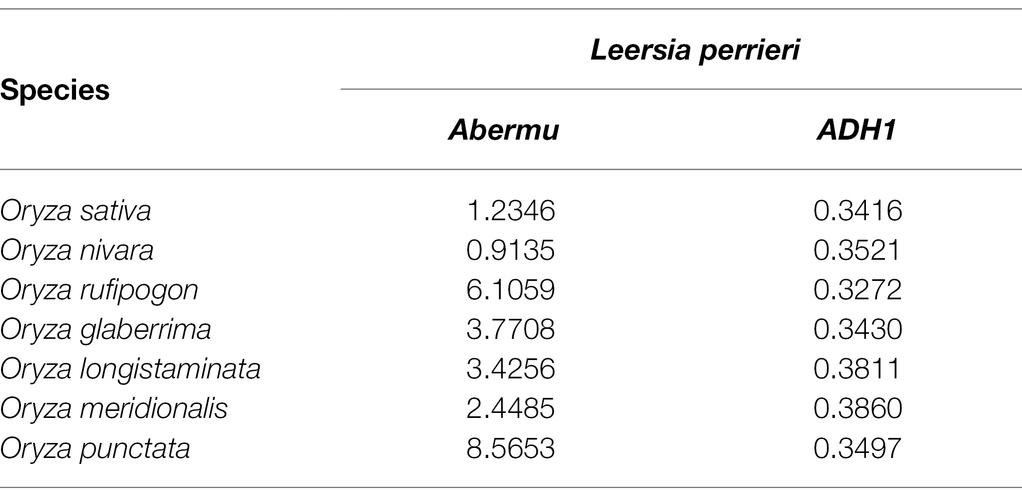

Our phylogenetic analysis suggests that Abermu share more close evolutionary relationship with MuDR than other reported MULEs (Figure 5A). However, these two mutator families have likely diverged a long time ago as the DNA sequence of Zmay_Abermu exhibited no sequence identity to MuDR in maize. In addition, a mutator transposon in barley called Hvu_MuDR (Figure 3) was identified which showed 64% sequence identity (E-value = 2 × e−53) to MuDR in maize but no significant sequence identity to Hvu_Abermu transposon in barley. Therefore, both Abermu and MuDR may have existed in the common ancestor of maize and barley which split about 50 million years ago (Gaut, 2002). Given that Abermu transposons are found in both dicots and monocots (Table 1), the emergence of Abermu family likely occurred even earlier than the divergence of maize and barley. Like many other genomic sequences, transposons are most transferred from parent to offspring, vertical transfers of transposons (VTT). However, they can also be transferred horizontally between reproductively isolated species even between plants and animals (Gao et al., 2018). The shared Abermu elements between barley and its wild species (Figures 6, 7; Supplementary Table S5) indicated the vertical transfers of Abermu elements. We also detected phylogenetic separations of Abermu elements in different Oryza species and Osa_Abermu in rice was grouped together with Lpe_Abermu but not with the Abermu from O. rufipogon, the wild progenitor of cultivated rice (Figures 5A,B). As L. perrieri has diverged from the Oryza genus about 15–20 million years ago (MYAs; Stein et al., 2018) and transposons were difficult to be retained for a long period. The phylogenetic separation and incongruence imply the possibility of horizontal transfer of Abermu between L. perrieri and rice. The synonymous divergence rate (Ks) provides another clue for HTTs (Diao et al., 2006). We calculated the Ks values of Abermu and the class I alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH1) gene between L. perrieri and each of the seven Oryza species (Table 3). The Ks value of ADH1 was similar for each pair of the comparisons. However, the Ks rates of Lpe_Abermu/Osa_Abermu and Lpe_Abermu/Oni_Abermu were much lower than other comparisons suggesting that Lpe _Abermu showed lower sequence divergence with Osa_Abermu and Oni_Abermu than with the Abermus in other Oryza species. Thus, both phylogenetic analysis and sequence divergence suggest possible horizontal transfers of Abermu sequences between L. perrieri and rice. It was reported that a MULE was horizontally transferred between the Setaria genus and rice (Diao et al., 2006). We compared Abermu transposons with the MULE sequences described by Diao et al. (2006), no significant sequence identity was detected suggesting that they were from different families.

The Origin and Function of ORFR

Except ORF1 encoding mutator transposase, some Abermu transposons contain one or two extra ORFs including the ORFR with opposite transcription director (Figure 3). Despite the molecular functions of the two ORFs are not clear, two basic questions need to be addressed. The first question is how and when the ORFR has emerged? As some MULEs (Pack-MULEs) can capture host’s genes (Yu et al., 2000; Jiang et al., 2004; Tan et al., 2021) and the Abermu elements in barley and other plants are larger than many MULEs, it was possible that the ORFR sequences were originally from host genomes and have been captured by the old Abermu transposons. No sequence similarity was detected between the ORFR sequences identified in distantly related plants. One possibility was that all ORFR sequences in different plants were derived from a single ancestor gene, but they evolved quickly (Table 2). Another possibility was that the ORFRs were acquired independently in different host genomes as we can see variable locations of ORFRs in different Abermu transposons, upstream or downstream of the ORF1 (Figure 3). It should be noted that Pack-MULEs are usually small (2–3 Kb) and non-autonomous transposons (Jiang et al., 2004). However, Hvu_Abermu in barley seems to be an autonomous transposon and has the potential to distribute the ORFR sequences throughout the genome. Second question is regarding the molecular function of ORFRs. In maize, MURB is crucial for the insertion of MuDR transposon as no new insertion was found in the lines without the mudrB gene (Lisch et al., 1999; Raizada and Walbot, 2000). The proteins encoded by the ORFRs of Abermu transposons showed no sequence similarity to MURB. We detected polymorphisms of Abermu which contains ORFR in the barley population (Supplementary Table S5). We also conducted genome-wide comparisons of Osa_Abermu transposon which lacks the ORFR sequence and identified polymorphic transposons between seven cultivated and wild rice genomes (Data not shown) suggesting recent activity of Osa_Abermu and that ORFR may be unimportant for transposition. However, more experiments are needed to better understand the functions of ORFR.

The Impacts and Potential Applications of Abermu Elements

Transposons contribute large fractions of cereal genomes such as 80.8% of the barley genome (Mascher et al., 2017) and 85.0% of the wheat genome (Zhu et al., 2021). However, their impacts on genome evolution and phenotypical mutations in major cereals are not well understood. More recent evidence revealed that transposons played pivotal roles in crop improvement including the seed quality in barley (Lei et al., 2020) and maize domestication (Studer et al., 2011). In the present study, we identified Abermu transposons in several agronomically important crops such as barley, wheat, rice, and maize, and found that Abermu-related sequences located in over 200 barley genes including CDSs and introns. In some cases, intronic transposons may affect gene functions. For example, a non-LTR retrotransposon located in an intron of the EgDEF1 gene altered the transcript and generated a truncated peptide causing abnormal fruits in oil palm (Ong-Abdullah et al., 2015). We are not sure if the Abermu element inserted in HORVU.MOREX.r2.1HG0047050.1 (Figure 6) affects the gene expression in barley and the functional divergence of the orthologous genes. The movements of transposons not only increase the host genetic diversity but also provide good resources for marker development. Indeed, our Abermu-based markers detected molecular polymorphisms among different barley genotypes (Figure 7).

Active transposons can be used to develop new genetic tools for gene-tagging and other studies (Fernandes et al., 2004). Barley has emerged as a model system for cereal crops, but no active transposon was identified in barley. Thus far, all transposon-based gene-tagging systems in barley were developed with the exogenous Ac/Ds transposons from maize (Singh et al., 2006; Lazarow and Lütticke, 2009). In rice, the endogenous retrotransposon Tos17 has been widely used for characterizing molecular functions of important genes (Miyao et al., 2003). We identified polymorphic Abermu elements within cultivated barley varieties and revealed the recent transpositional activity of Abermu. Thus, it provides potential resources for developing gene-tagging systems with this endogenous transposon in barley, wheat, and other crops. However, more experiments are needed to address the value of Abermu for gene-tagging system including to investigate if Abermu transposon can maintain its transposition activity in different generations and compare the polymorphic insertions between the wild type and the mutants induced by tissue culture and other stresses.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary Material.

Author Contributions

DG and XC designed the experiments. DG and AC performed computational and molecular analysis. HB, GH, and DG identified and provided seeds. DG drafted the manuscript. All authors were involved in manuscript revision and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. Mention of trade names or commercial products in this publication is solely for the purpose of providing specific information and does not imply recommendation or endorsement by the United States Department of Agriculture.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Noelle Anglin for the helpful comments.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2022.904619/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^http://plants.ensembl.org/Hordeum_vulgare/Info/Index

3. ^http://www.repeatmasker.org

4. ^https://bedtools.readthedocs.io

5. ^https://www.sanger.ac.uk/tool/artemis-comparison-tool-act

References

Badr, A., Müller, K., Schäfer-Pregl, R., El Rabey, H., Effgen, S., Ibrahim, H. H., et al. (2000). On the origin and domestication history of barley (Hordeum vulgare). Mol. Biol. Evol. 17, 499–510. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026330

Burge, C., and Karlin, S. (1997). Prediction of complete gene structures in human genomic DNA. J. Mol. Biol. 268, 78–94. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.0951

Carciofi, M., Blennow, A., Nielsen, M. M., Holm, P. B., and Hebelstrup, K. H. (2012). Barley callus: a model system for bioengineering of starch in cereals. Plant Methods 8:36. doi: 10.1186/1746-4811-8-36

Chalvet, F., Grimaldi, C., Kaper, F., Langin, T., and Daboussi, M. J. (2003). Hop, an active Mutator-like element in the genome of the fungus Fusarium oxysporum. Mol. Biol. Evol. 20, 1362–1375. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msg155

Cresse, A. D., Hulbert, S. H., Brown, W. E., Lucas, J. R., and Bennetzen, J. L. (1995). Mu1-related transposable elements of maize preferentially insert into low copy number DNA. Genetics 140, 315–324. doi: 10.1093/genetics/140.1.315

Davidson, S., Starkey, A., and MacKenzie, A. (2009). Evidence of uneven selective pressure on different subsets of the conserved human genome; implications for the significance of intronic and intergenic DNA. BMC Genomics 10:614. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-614

Diao, X., Freeling, M., and Lisch, D. (2006). Horizontal transfer of a plant transposon. PLoS Biol. 4:e5. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040005

Fedoroff, N. V. (2012). Transposable elements, epigenetics, and genome evolution. Science 338, 758–767. doi: 10.1126/science.338.6108.758

Fernandes, J., Dong, Q., Schneider, B., Morrow, D. J., Nan, G. L., Brendel, V., et al. (2004). Genome-wide mutagenesis of Zea mays L. using RescueMu transposons. Genome Biol. 5:R82. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-10-r82

Feschotte, C., and Pritham, E. J. (2007). DNA transposons and the evolution of eukaryotic genomes. Annu. Rev. Genet. 41, 331–368. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.40.110405.090448

Forde, B. G., Freeman, J., Oliver, J. E., and Pineda, M. (1990). Nuclear factors interact with conserved A/T-rich elements upstream of a nodule-enhanced glutamine synthetase gene from French bean. Plant Cell 2, 925–939. doi: 10.1105/tpc.2.9.925

Gao, D. (2012). Identification of an active Mutator-like element (MULE) in rice (Oryza sativa). Mol. Gen. Genomics. 287, 261–271. doi: 10.1007/s00438-012-0676-x

Gao, D., Chu, Y., Xia, H., Xu, C., Heyduk, H., Abernathy, B., et al. (2018). Horizontal transfer of non-LTR retrotransposons from arthropods to flowering plants. Mol. Biol. Evol. 35, 354–364. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msx275

Gao, D., Gill, N., Kim, H. R., Walling, J. G., Zhang, W., Fan, C., et al. (2009). A lineage-specific centromere retrotransposon in Oryza brachyantha. Plant J. 60, 820–831. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.04005.x

Gaut, B. S. (2002). Evolutionary dynamics of grass genomes. New Phytol. 154, 15–28. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-8137.2002.00352.x

Hershberger, R. J., Warren, C. A., and Walbot, V. (1991). Mutator activity in maize correlates with the presence and expression of the mu transposable element Mu9. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 88, 10198–10202. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.22.10198

Jayakodi, M., Padmarasu, S., Haberer, G., Bonthala, V. S., Gundlach, H., Monat, C., et al. (2020). The barley pan-genome reveals the hidden legacy of mutation breeding. Nature 588, 284–289. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2947-8

Jiang, N., Bao, Z., Zhang, X., Eddy, S. R., and Wessler, S. R. (2004). Pack-MULE transposable elements mediate gene evolution in plants. Nature 431, 569–573. doi: 10.1038/nature02953

Jiang, N., Bao, Z., Zhang, X., Hirochika, H., Eddy, S. R., McCouch, S. R., et al. (2003). An active DNA transposon family in rice. Nature 421, 163–167. doi: 10.1038/nature01214

Kapitonov, V. V., and Jurka, J. (2006). Self-synthesizing DNA transposons in eukaryotes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103, 4540–4545. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600833103

Kazazian, H. H. (2004). Mobile elements: drivers of genome evolution. Science 303, 1626–1632. doi: 10.1126/science.1089670

Lazarow, K., and Lütticke, S. (2009). An ac/ds-mediated gene trap system for functional genomics in barley. BMC Genomics 10:55. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-55

Lei, G. J., Fujii-Kashino, M., Wu, D. Z., Hisano, H., Saisho, D., Deng, F., et al. (2020). Breeding for low cadmium barley by introgression of a Sukkula-like transposable element. Nat. Food 1, 489–499. doi: 10.1038/s43016-020-0130-x

Lisch, D. (2002). Mutator transposons. Trends Plant Sci. 7, 498–504. doi: 10.1016/S1360-1385(02)02347-6

Lisch, D. (2009). Epigenetic regulation of transposable elements in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 60, 43–66. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.59.032607.092744

Lisch, D., Girard, L., Donlin, M., and Freeling, M. (1999). Functional analysis of deletion derivatives of the maize transposon MuDR delineates roles for the MURA and MURB proteins. Genetics 151, 331–341. doi: 10.1093/genetics/151.1.331

Liu, M., Li, Y., Ma, Y., Zhao, Q., Stiller, J., Feng, Q., et al. (2020). The draft genome of a wild barley genotype reveals its enrichment in genes related to biotic and abiotic stresses compared to cultivated barley. Plant Biotechnol. J. 18, 443–456. doi: 10.1111/pbi.13210

Liu, K., and Wessler, S. R. (2017). Functional characterization of the active Mutator-like transposable element, Muta1 from the mosquito Aedes aegypti. Mob. DNA 8:1. doi: 10.1186/s13100-016-0084-6

Mascher, M., Cundlach, H., Himmelbach, A., Beier, S., Twardziok, S. O. R. Y. Z. A., Wicker, T., et al. (2017). A chromosome conformation capture ordered sequence of the barley genome. Nature 544, 427–433. doi: 10.1038/nature22043

Matsumoto, T., Tanaka, T., Sakai, H., Amano, N., Kanamori, H., Kurita, K., et al. (2011). Comprehensive sequence analysis of 24,783 barley full-length cDNAs derived from 12 clone libraries. Plant Physiol. 156, 20–28. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.171579

Miyao, A., Tanaka, K., Murata, K., Sawaki, H., Takeda, S., Abe, K., et al. (2003). Target site specificity of the Tos17 retrotransposon shows a preference for insertion within genes and against insertion in retrotransposon-rich regions of the genome. Plant Cell 15, 1771–1780. doi: 10.1105/tpc.012559

Ong-Abdullah, M., Ordway, J. M., Jiang, N., Ooi, S. E., Kok, S. Y., Sarpan, N., et al. (2015). Loss of karma transposon methylation underlies the mantled somaclonal variant of oil palm. Nature 525, 533–537. doi: 10.1038/nature15365

Payer, L. M., and Burns, K. H. (2019). Transposable elements in human genetic disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 20, 760–772. doi: 10.1038/s41576-019-0165-8

Petrov, D. A., Aminetzach, Y. T., Davis, J. C., Bensasson, D., and Hirsh, A. E. (2003). Size matters: non-LTR retrotransposable elements and ectopic recombination in drosophila. Mol. Biol. Evol. 20, 880–892. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msg102

Raizada, M. N., and Walbot, V. (2000). The late developmental pattern of mu transposon excision is conferred by a CaMV 35S-driven MURA cDNA in transgenic maize. Plant Cell 12, 5–21. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.1.5

Robertson, D. S. (1978). Characterization of a Mutator system in maize. Mutat. Res. 51, 21–28. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(78)90004-0

Schreiber, M., Mascher, M., Wright, J., Padmarasu, S., Himmelbach, A., Heavens, D., et al. (2020). A genome assembly of the barley ‘Transformation Reference’ cultivar golden promise. G3 10, 1823–1827. doi: 10.1101/2020.02.12.945550

Seehausen, O., Butlin, R. K., Keller, I., Wagner, C. E., Boughman, J. W., Hohenlohe, P. A., et al. (2014). Genomics and the origin of species. Nat. Rev. Genet. 15, 176–192. doi: 10.1038/nrg3644

Sendell-Price, A. T., Ruegg, K. C., Anderson, E. C., Quilodrán, C. S., Van Doren, B. M., Underwood, V. L., et al. (2020). The genomic landscape of divergence across the speciation continuum in Island-colonising silvereyes (Zosterops lateralis) 10, 3147–3163. doi: 10.1534/g3.120.401352

Singer, T., Yordan, C., and Martienssen, R. A. (2001). Robertson's Mutator transposons in A. thaliana are regulated by the chromatin-remodeling gene decrease in DNA methylation (DDM1). Genes Dev. 15, 591–602. doi: 10.1101/gad.193701

Singh, J., Zhang, S., Chen, C., Cooper, L., Bregitzer, P., Sturbaum, A., et al. (2006). High-frequency ds remobilization over multiple generations in barley facilitates gene tagging in large genome cereals. Plant Mol. Biol. 62, 937–950. doi: 10.1007/s11103-006-9067-1

Solovyev, V., Kosarev, P., Seledsov, I., and Vorobyev, D. (2006). Automatic annotation of eukaryotic genes, pseudogenes and promoters. Genome Biol. 7(Suppl. 1), S10.1–S10.12. doi: 10.1186/gb-2006-7-s1-s10

Spradling, A. C., Bellen, H. J., and Hoskins, R. A. (2011). Drosophila P elements preferentially transpose to replication origins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108, 15948–15953. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112960108

Stein, J. C., Yu, Y., Copetti, D., Zwickl, D. J., Zhang, L., Zhang, C., et al. (2018). Genomes of 13 domesticated and wild rice relatives highlight genetic conservation, turnover and innovation across the genus Oryza. Nat. Genet. 50, 285–296. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0040-0

Studer, A., Zhao, Q., Ross-Ibarra, J., and Doebley, J. (2011). Identification of a functional transposon insertion in the maize domestication gene tb1. Nat. Genet. 43, 1160–1163. doi: 10.1038/ng.942

Suyama, M., Torrents, D., and Bork, P. (2006). PAL2NAL: robust conversion of protein sequence alignments into the corresponding codon alignments. Nucleic Acids Res. 34, W609–W612. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl315

Talavera, G., and Castresana, J. (2007). Improvement of phylogenies after removing divergent and ambiguously aligned blocks from protein sequence alignments. Syst. Biol. 56, 564–577. doi: 10.1080/10635150701472164

Tamura, K., Stecher, G., and Kumar, S. (2021). MEGA11: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 38, 3022–3027. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msab120

Tan, B. C., Chen, Z., Shen, Y., Zhang, Y., Lai, J., and Sun, S. S. (2011). Identification of an active new mutator transposable element in maize. G3 1, 293–302. doi: 10.1534/g3.111.000398

Tan, S., Ma, H., Wang, J., Wang, M., Wang, M., Yin, H., et al. (2021). DNA transposons mediate duplications via transposition-independent and -dependent mechanisms in metazoans. Nat. Commun. 12:4280. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-24585-9

Untergasser, A., Cutcutache, I., Koressaar, T., Ye, J., Faircloth, B. C., Remm, M., et al. (2012). Primer3: new capabilities and interfaces. Nucleic Acids Res. 40:e115. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks596

Xu, W., Tucker, J. R., Bekele, W. A., You, F. M., Fu, Y. B., Khanal, R., et al. (2021). Genome assembly of the Canadian two-row malting barley cultivar AAC synergy. G3 11:jkab031. doi: 10.1093/g3journal/jkab031

Xu, Z., Yan, X., Maurais, S., Fu, H., O'Brien, D. G., Mottinger, J., et al. (2004). Jittery, a Mutator distant relative with a paradoxical mobile behavior: excision without reinsertion. Plant Cell 16, 1105–1114. doi: 10.1105/tpc.019802

Yu, Z., Wright, S. I., and Bureau, T. E. (2000). Mutator-like elements in Arabidopsis thaliana. Structure, diversity and evolution. Genetics 156, 2019–2031. doi: 10.1093/genetics/156.4.2019

Zeng, X., Xu, T., Ling, Z., Wang, Y., Li, X., Xu, S., et al. (2020). An improved high-quality genome assembly and annotation of Tibetan hulless barley. Sci. Data 7:139. doi: 10.1038/s41597-020-0480-0

Zhao, D., Ferguson, A., and Jiang, N. (2015). Transposition of a rice Mutator-like element in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Plant Cell 27, 132–148. doi: 10.1105/tpc.114.128488

Keywords: barley, mutator, genome evolution, horizontal transfer of transposon, ORFR

Citation: Gao D, Caspersen AM, Hu G, Bockelman HE and Chen X (2022) A Novel Mutator-Like Transposable Elements With Unusual Structure and Recent Transpositions in Barley (Hordeum vulgare). Front. Plant Sci. 13:904619. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.904619

Edited by:

Mathieu Rouard, Alliance Bioversity International and CIAT, FranceReviewed by:

Francois Sabot, Institut de Recherche Pour le Développement (IRD), FranceCheng Sun, Institute of Apiculture Research (CAAS), China

Copyright © 2022 Gao, Caspersen, Hu, Bockelman and Chen. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Dongying Gao, ZG9uZ3lpbmcuZ2FvQHVzZGEuZ292

Dongying Gao

Dongying Gao Ann M. Caspersen1

Ann M. Caspersen1 Gongshe Hu

Gongshe Hu