95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Plant Sci. , 29 April 2022

Sec. Plant Development and EvoDevo

Volume 13 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2022.878693

This article is part of the Research Topic Insights in Plant Development and EvoDevo: 2021 View all 7 articles

Reconstructing the development of sporangia in seed-free vascular plants provides crucial information about key processes enabling the production of spores that are important in the life cycle of these plants. By applying fluorescence imaging in intact tissues using dyes and confocal microscopy, this study aimed to reconstruct the key steps during the development of sporangia. Special emphasis was taken on the cell wall structures of tapetum and spore mother cells that have been challenged by microscopical documentation in the past. After staining the cell wall and cytoplasm using calcofluor white and basic fuchsin, the sporangium development of Pteris multifida was observed using confocal microscopy. The clear cell lineages from the sporangial initial cell to stalk, epidermis, inner tapetum, outer tapetum, and sporogenous cells were revealed by confocal imaging. The sporangium development improved in this work will be useful for a general understanding of fern spore formation.

The pteridophytes are constituted of lycophytes and ferns, both of which are spore plants (Smith et al., 2006; PPGI, 2016). Ferns are the second largest group of vascular plants (Kenrick and Crane, 1997), which provides functional comparisons with bryophytes, lycophytes, and seed plants (Harald Schneider et al., 2002; Schneider, 2013; Plackett et al., 2015). Ferns are further divided into eusporangiate and leptosporangiate (Clark et al., 2016). Pteris multifida Poir. belongs to the genus Pteris of the family Pteridaceae in the order Polypodiales of Leptosporangiatidae. Ferns include about 10,578 species, of which about 8,714 species belong to the Polypodiales. Pteridaceae has about 1,211 species, of which 250 species belong to the genus Pteris (PPGI, 2016). In the relatively evolved Polypodiales, the genus Pteris is a primitive group (Smith et al., 2006). Pteris multifida is native to Asia and is now widely distributed in many tropical, subtropical, and temperate regions of the world. It grows on walls, wells, and limestone crevices or under shrubs (Riefner and Smith, 2016). Pteris multifida is also one of the most common ornamental ferns. This species is a kind of folk herbal medicine known as Fengwei grass (Zheng et al., 2008; Ouyang et al., 2010; Yu et al., 2013).

Sporangium is the reproductive organ to produce spores. Fern plant shows great differences in sporangium morphology. Sporangium development in leptosporangiate had been carried out since Sheffield and Bell, 1979; the later decades of the 19th century (Bower, 1891; Wilson, 1958b,1999;

Long et al., 2016). Based on the research in some common genera, such as Plagiogyria, Asplenium, Pteridium, Pyrrosia, Xiphopteris of Polypodiales, fern sporangium development has been established (Bower, 1910; Warren and Wager, 1953; Wilson, 1958b,1960; Holttum et al., 1970; Sheffield and Bell, 1979).

Semi-thin sectioning is the major method for cellular analysis of sporangium development in fern (Wilson, 1958b,1999; Oldenhof and Willemse, 1999). This method may damage the tissue morphology which misleads results (Wilson, 1958b; Xue et al., 2021). During meiosis of sporangium development, the cell wall of the tapetum and the spore mother cells become extremely difficult to discern, and the actual behavior is difficult to recognize through the sections (Wilson, 1958b). With advances in microscopy technology, several fluorescence imaging methods have been developed to observe plant intact tissues. These methods provide high-resolution images in vivo, without sectioning and dehydrating (Truernit et al., 2008; Andriankaja et al., 2012; Sappl and Heisler, 2013; Kurihara et al., 2015; Ursache et al., 2018). Anther of seed plant is a homologous organ of the sporangium in fern. Recently, a fluorescence imaging method has been successfully used in Arabidopsis, showing clear cell lineages during anther development (Xue et al., 2021). Here, we established a co-staining method to observe sporangium development in leptosporangiate Pteris multifida. We provide clear cell lineages of the epidermis, inner tapetum, outer tapetum, and sporogenous cells of Pteris sporangium. These results will be helpful to the general understanding of sporangium development in ferns.

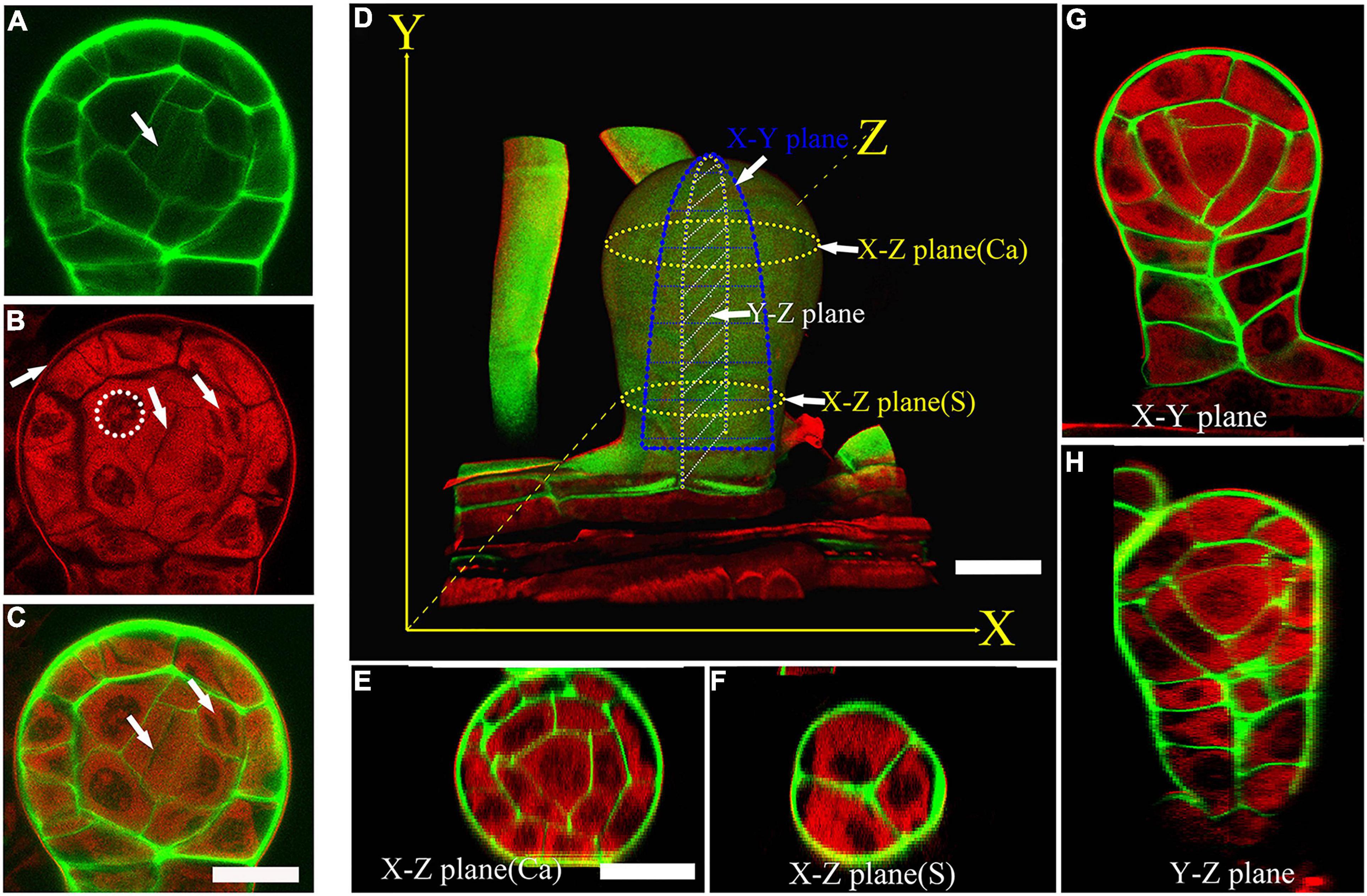

Pteris multifida is a typical species of Pteridaceae (PPGI, 2016). It has fertile leaves with sporangia in the intramarginal position (Supplementary Figure 1). To observe the sporangium development and cell lineages, we established a technique of co-staining and confocal imaging in Pteris multifida. Sporangia were fixed in ClearSee to improve the transparency for deep imaging (Supplementary Figure 1E; Kurihara et al., 2015). Calcofluor white (CW) stains polysaccharides of the cell wall (Ursache et al., 2018). Basic fuchsin (BF) is a commonly used red fluorescent dye for lignin, a product of the phenylpropanoid pathway (Yokoyama et al., 2007; Ursache et al., 2018). Recently, we showed that the sporopollenin wall of vascular plants also contains derivatives of the phenylpropanoid pathway (Xue et al., 2020), and BF could stain microspore sporopollenin wall. To observe both the cell lineages of sporangia and sporopollenin wall, co-staining of BF and CW was performed (Supplementary Figure 1E). The CW signals colored green clearly show the cell wall of sporangial layers (Figure 1A). The weak CW signals indicate newly formed cells in the sporangium (Figure 1A). The BF signals colored red are mainly detected in the cytoplasm of all the sporangial layers (Figure 1B), indicating that the phenylpropanoid derives might be synthesized in these cells. BF staining shows the cytokinesis of the sporangial cell, which is consistent with the CW staining showing newly formed cell walls. Therefore, the co-staining can observe the different cell layers and cell divisions in sporangium (Figure 1C). We performed a Z-stack of a series of 2-dimensional (2D) images to re-constitute the 3-dimensional (3D) structure of the sporangium (Figures 1D, and Supplementary Figure 2). The transverse light section of the sporangium is called the X-Z planes (Figures 1E,F). The periclinal light section of the sporangium is called the X-Y planes (Figure 1G). The anticlinal light section of the sporangium is called the Y-Z planes (Figure 1H). The morphology of the sporangium is observed in these light sections for a comprehensive analysis of the 3D organ structure, cell division, and developmental process (Supplementary Figure 2).

Figure 1. A co-staining method for the cell lineages and sporangium development. (A) CW staining of a sporangium. CW signals are colored green. Arrow points to the newly formed cell wall. (A–C) are at the same magnification. (B) BF staining of a sporangium. BF signals are colored red. Dotted circle points to the uncolored nuclear. The middle arrow points to the cytokinesis. The left arrow points to the outer wall of epidermal cells. The right arrow points to the nuclear division. (C) Merged image of (A,B). The left arrow points to the newly formed cell wall. The right arrow points to the nuclear division. Scale bar = 20μm. (D) 3D imaging of a sporangium. CW signals are colored green. BF signals are colored red. Scale bar = 20μm. (E) X-Z plane of a capsule. Scale bar = 20μm. (E–H) are at the same magnification. (F–H) X-Z plane of the stalk cells, X-Y plane of the sporangium, Y-Z plane of the sporangium. CW signals are colored green. BF signals are colored red. Ca, capsule; S, stalk cell.

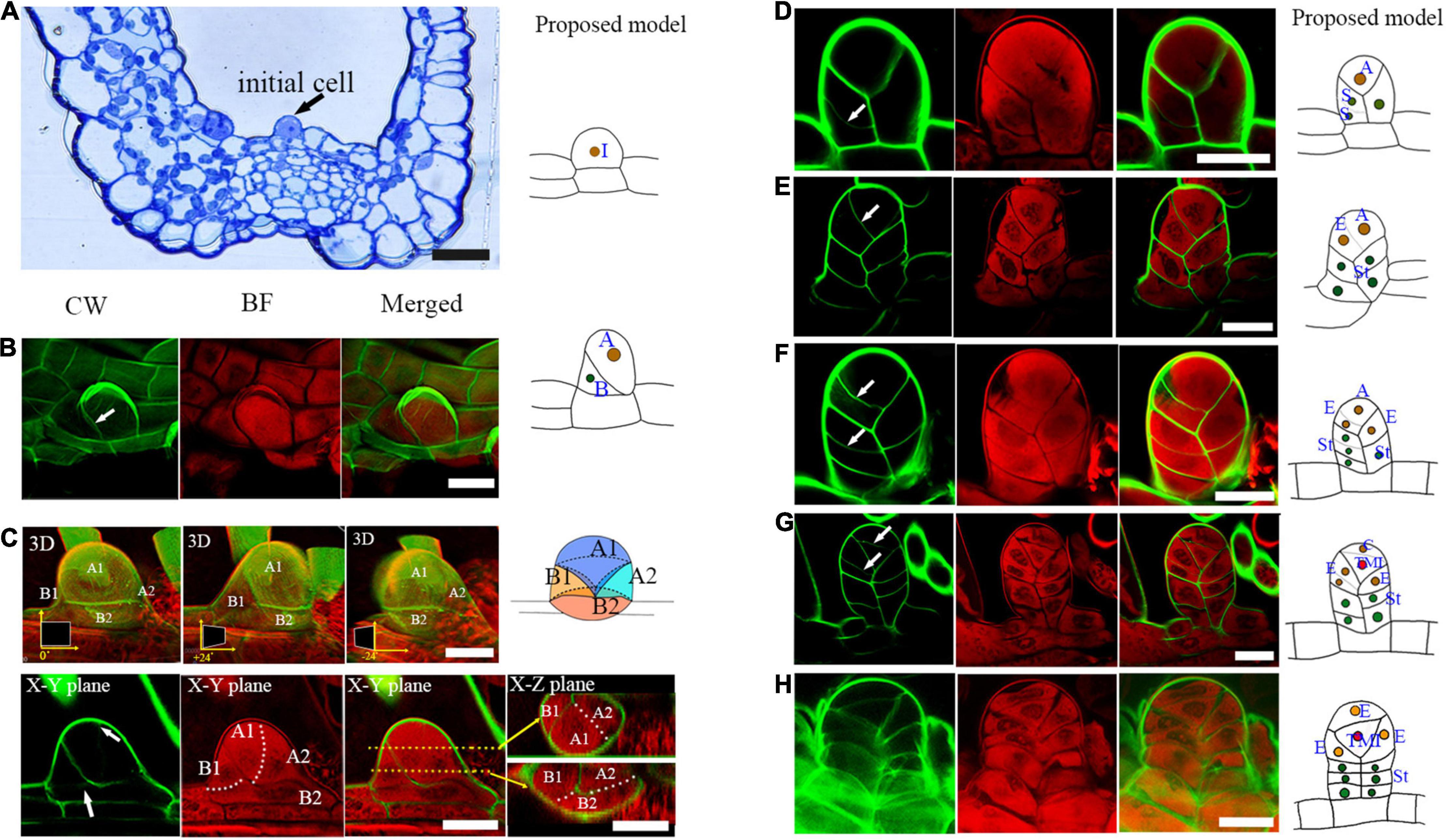

To observe the sporangium development in Pteris, this co-staining method was used in this study. The sporangium originates from a single superficial primordial cell of the receptacle, which is called the sporangial initial cell (Figure 2A; Bower, 1891; Wilson, 1999). The outer growth of the sporangial initial cell establishes the proximal-distal axes (Y-axis in this study) of the sporangium. The formation of an oblique cell wall indicates that this sporangial initial cell undergoes an asymmetric division (Figure 2B). Thereafter, both the basal and apical cells undergo further cell expansion (Figure 2C). The second round of asymmetric cell division occurs both in the apical and basal cells. The basal cell divides into two daughter cells, occupying about 2/3 of the base of the sporangium (Figure 2C). In the apical cell, an anticlinal oblique cell division was observed (Figure 2C). This cell division produces a daughter cell and a new apical cell. The daughter cell occupies 1/3 of the base of the sporangium (Figure 2C). The medio-lateral (Z-axis in this study) and adaxial-abaxial axis (X-axis in this study) are established after these cell divisions. At this stage, the sporangium consists of four cells: a new apical cell and three basal cells (Figure 2C).

Figure 2. Several rounds of asymmetric cell division initiate early sporangium development. (A) Semi-thin section stained with toluidine blue shows a sporangial initial cell (indicated by an arrow). (B) A sporangial initial cell under asymmetric division. Arrow points to the cell wall (C). The sporangium consists of four cells. The 3D diagram shows three rotations of 0 degrees, positive 24 degrees, and negative 24 degrees, respectively. The upper arrow points to the newly forming cell wall between the apical cell, the lower arrow points to the newly forming cell wall between the basal cell of the CW staining photo. The two white dotted lines represent the cell walls that will be formed. The two orange dotted lines represent two X-Z planes which are indicated with the two orange arrows. (D) Basal cells performed transverse division which formed the sporangial stalk. Arrow points to the newly formed cell wall. (E) The apical cell formed a new stalk cell. Arrow points to the newly formed cell wall. (F) The apical cell formed an epidermis cell and a new apical cell through oblique divisions. Arrows point to the newly formed cell wall. (F) An epidermis cell formed a stalk cell. Arrows point to the newly formed cell wall. (H) The tetrahedral mother initial cell formed. CW signals are colored green. BF signals are colored red. Scale bar = 20μm. (A–H) Proposed models are shown on the right of each inset. (A), the apical cell; (A1, A2), the daughter cells of the apical cell. (A1), the new apical cell; (A2), the third basal cell; TMI, the tetrahedral mother initial cell; (B), basal cell; (B1, B2), the daughter cells of basal cell; (C), the cap cell; (E), the epidermis cell; I, the initial cell; St, the stalk cell; 3D, three-dimensional.

The three basal cells perform several rounds of cell division to form the three-rowed sporangial stalk (Figures 2D,E,F,H). However, only the upper layer of the sporangial stalk will undergo further cell division, and all of them are horizontal divisions (Figure 2F). The apical cell performs three oblique divisions in different directions, forming three epidermal cells and another apical cell (Figures 2E,F). Finally, this apical cell produces a cap cell and an enclosed tetrahedral mother initial cell through a transverse cell division (Figures 2G,H). The three epidermal cells and the cap cell surrounding the tetrahedral mother initial cell further develop into the sporangial epidermis (Figures 2G,H). The sporangium now consists of a stalk and a capsule (Figure 2H). The capsule is constituted of four epidermis cells and an enclosed mother initial cell (Figure 2H).

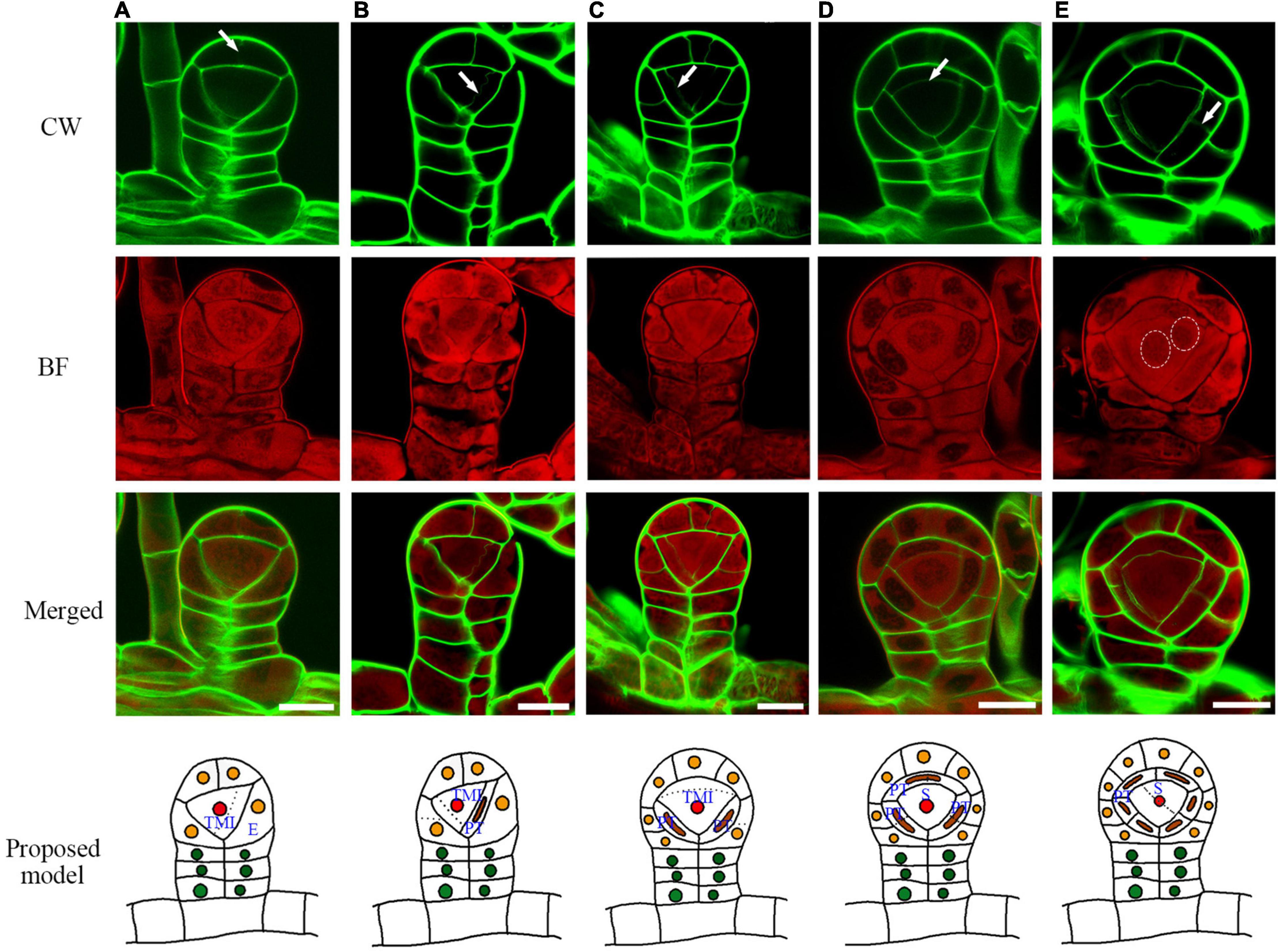

After the establishment of the capsule, the epidermis cell layer only performs anticlinal cell division (Figure 3). The tetrahedral mother initial cell performs four rounds of oblique cell divisions to produce the primary tapetum layer and an enclosed sporogenous cell (Figures 3B–D). The primary tapetum cells undergo anticlinal cell division to increase the cell numbers before the sporogenous cell mitoses (Figure 3E). The sporogenous cell undergoes multiple symmetric mitoses to produce the spore mother cells (Figures 4A–D). Usually, each sporangium contains about 64 spores. This indicates that the sporogenous cell undergoes 4 mitoses to produce 16 spore mother cells with each of them further divided into 4 spores. The primary tapetal layer produces the outer tapetal layer and inner tapetal layer through a periclinal cell division (Figures 4A–C). The morphology of the two layers of tapetal cells is quite similar at this stage (Figure 4C). CW staining shows both sporogenous cells and tapetum cells contain cellulose walls which is similar to the regular plant cell walls during the mitotic stage (Figures 4A–C). However, the cell walls of the spore mother cells and inner tapetum cells are gradually degraded after their last mitosis (Figures 4D,E).

Figure 3. The sporangium development with the formation of epidermis, tapetum, and sporangium cells. (A) The cap epidermis cell of the capsule undergoes an anticlinal division. (B) The tetrahedral mother initial cell cuts off the first primary tapetum cell. (C) The tetrahedral mother initial cell cuts off the second primary tapetum cell. (D) Arrow points to the cell wall being formed between the primary sporogenous cell and the primary tapetum cell. (E) The primary tapetum cell undergoes an anticlinal division. Two dotted circles point to the nuclear division. CW signals are colored green. BF signals are colored red. Arrow points to the newly formed cell wall. Scale bar = 20μm. (A–E) Proposed models are shown on the right of each inset. TMI, tetrahedral mother initial cell; PT, primary tapetum cell; S, sporogenous cell; E, epidermis cell.

Figure 4. The primary tapetum was divided into two layers by the periclinal division, and the sporogenous cells were divided four times to form sixteen spore mother cells. (A) The sporogenous cell undergoes symmetric mitosis. Arrow points to the newly formed cell wall. (B) A primary tapetum cell undergoes a periclinal division. Arrow points to the newly formed cell wall.(C) The primary tapetal layer produces two tapetal layers through periclinal divisions.(D) Two tapetal layers are formed. (E) Some cell walls among the spore mother cells and inner tapetal cells are gradually degraded. Arrow points to the degrading cell wall between a spore mother cell and inner tapetal cell. Dotted circle points to the area where the cell walls are degraded. CW signals are colored green. BF signals are colored red. Scale bar = 20μm. (A–E) Proposed models are shown on the right of each inset. PT, primary tapetum cell; IT, inner tapetum cell; OT, outer tapetum cell; S, sporogenous cell.

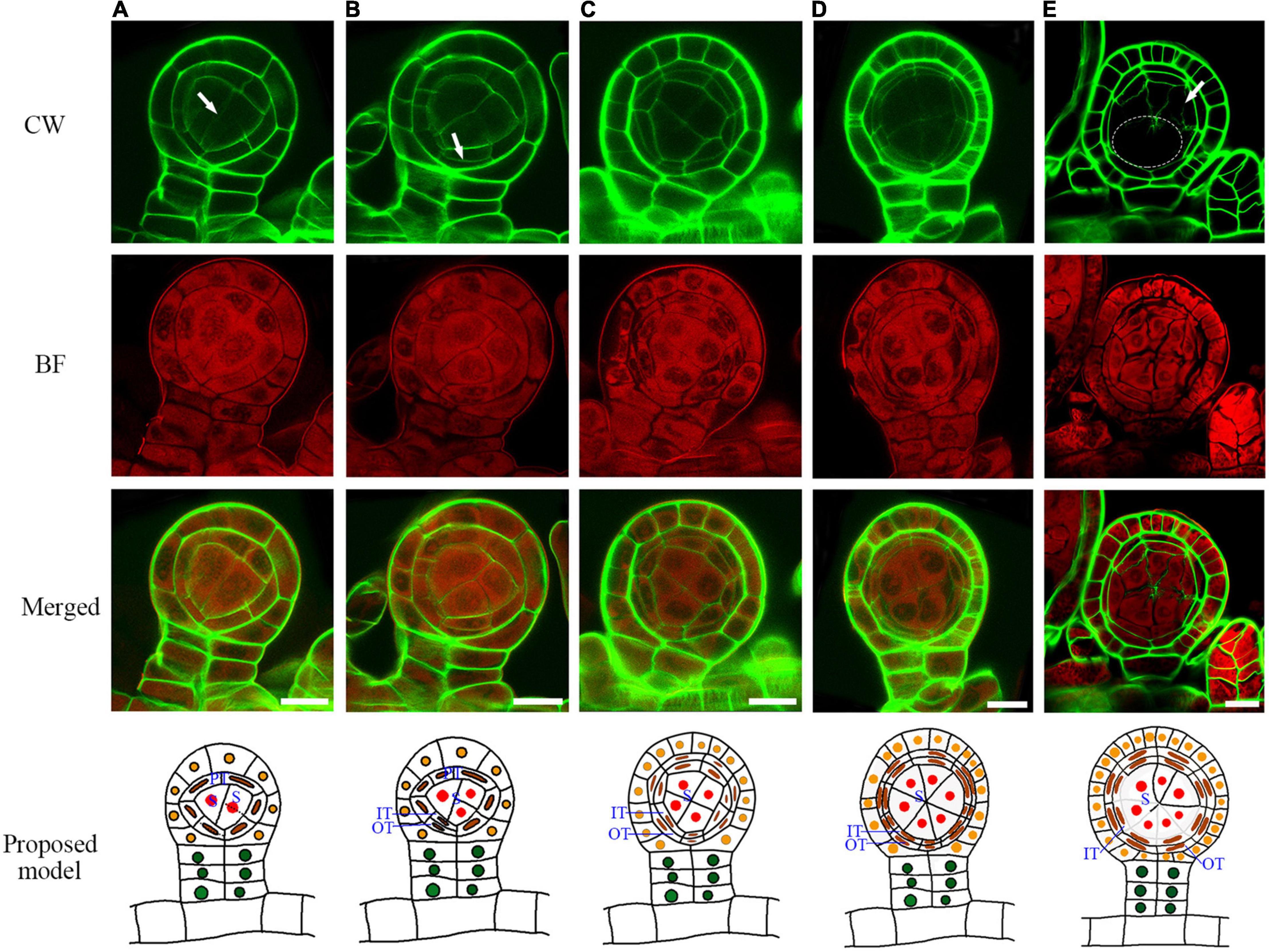

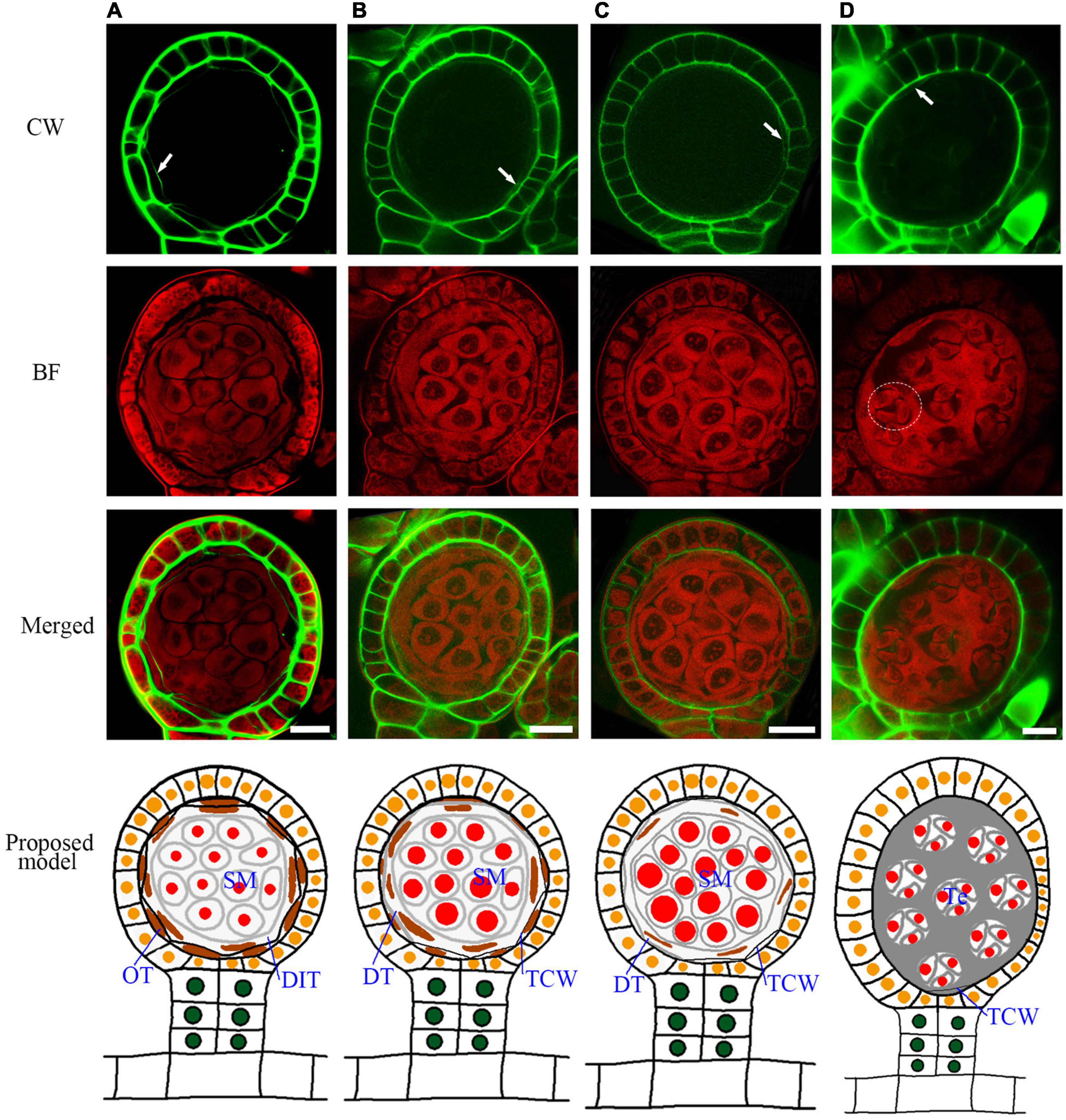

A spore mother cell undergoes meiosis to produce a tetrad. During this process, the spore mother cell wall is gradually degraded, and some materials are accumulated outside to form a tetrad wall (Supplementary Figure 3). This cell wall transition is quite similar to Arabidopsis (Xue et al., 2021). After the cell wall degradation, the spore mother cells turn to round and separate from each other (Figure 5A–C). The outer tapetum becomes a very thin cell layer while the inner tapetum layer is enlarged which adheres closely to the spore mother cells (Figures 5A,B, and Supplementary Figure 4). This result indicates a functional differentiation of the inner and outer tapetum layers. After meiosis, the microspores are enclosed in the tetrad wall (Figure 5D). CW stains Arabidopsis tetrad wall green (Supplementary Figure 3). However, the tetrad wall of Pteris shows no CW signals (Figures 5A,B). This indicates that the composition of the tetrad wall of Pteris is different from the callose in angiosperms. The cell wall of the outer tapetum is also degraded at this stage (Figure 5D). During sporangium development, the epidermis cells undergo anticlinal division to increase the volume of the locule (Figures 5A–C). At the meiosis stage, some epidermis cells are thinner than others, suggesting that these cells are differentiated into the stomium cell (Figure 5D).

Figure 5. Sporangium development with tetrad formation. The spore mother cells undergo meiosis to form the tetrads, and the cell wall of the tapetum is degraded. (A) The spore mother cell wall has been completely degraded. The cell wall of the inner tapetum degradation. Arrow points to the wall of the outer tapetal cell. (B,C) The inner tapetum cells become hypertrophy. Arrow points to the wall of the outer tapetal cell. (D) Tetrads are formed while the inner tapetum cells are almost disintegrated. Arrow points to the wall of the outer tapetal cell. The dotted circle points to the area of one tetrad. CW signals are colored green. BF signals are colored red. Scale bar = 20μm. (A–D) Proposed models are shown on the right of each inset. DIT, degraded inner tapetum cell; OT, outer tapetum cell; SM, spore mother cell; Te, tetrad; TCW, tapetum cell wall.

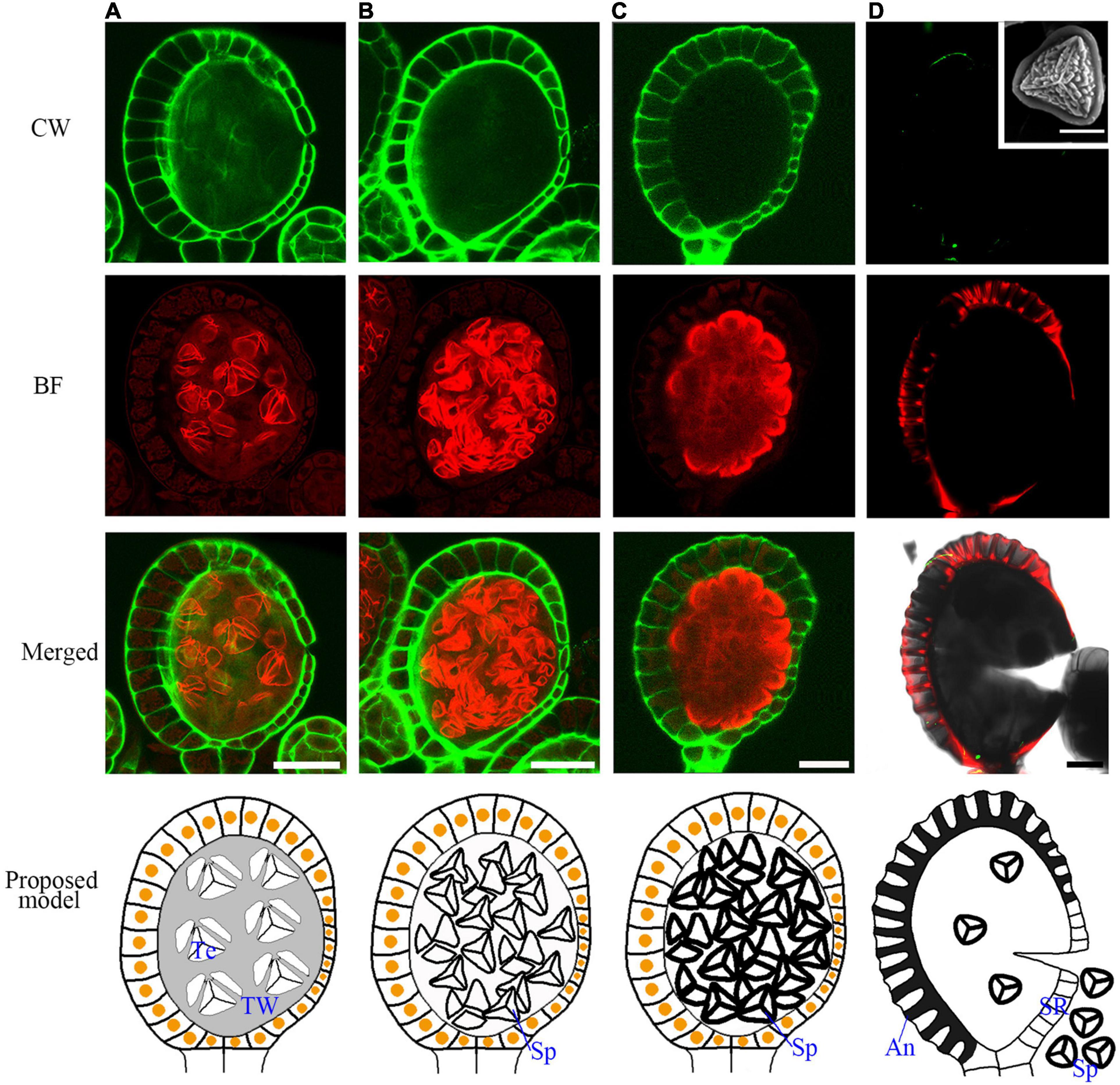

At the later tetrad stage, the haploid spores are covered by a sporopollenin wall (Figures 6A,B). In seed plants, sporopollenin material is from the tapetum. However, in the Pteris spore, sporopollenin is gradually accumulated after the degradation of the tapetum (Figures 6A–D and Supplementary Figure 5). Thus, epidermis or spores may also provide materials for sporopollenin formation. The annulus is a special structure on the sporangium, consisting of a row of cells that are unevenly thickened on the epidermis of the sporangium. It plays a role in dehiscence and spore dispersal (Noblin et al., 2012). The BF staining shows strong signals in the thickened annulus, indicating the lignification occurs in fern sporangium (Figure 6D and Supplementary Figure 6).

Figure 6. The mature spore formation and the lignification of the annulus in the epidermis for sporangium dehiscence. (A–C) The spores are released from tetrads in the spore sac and the spore wall is gradually thickened. (D) The annulus in the epidermis cells are lignified and mature spores are released from the sporangia. The SEM picture of the inset shows a mature spore. Scale bar = 20μm. CW signals are colored green. BF signals are colored red. Scale bar = 50μm. (A–D) Proposed models are shown on the right of each inset. An, annulus; TW, tetrads wall; SR, stomial region; Te, tetrad; Sp, spore.

Semi-thin sectioning is the classical tool that provides the fundamental knowledge of the developmental process of sporangia in all the land plants (Sheffield and Bell, 1979; Brown and Lemmon, 1980; Renzaglia et al., 1997; Sanders et al., 1999; van der Linde and Walbot, 2019). The two-dimensional images based on classical sectioning may miss some important information of plant cells with the wall structure. In this study, we established a fluorescence imaging method for sporangium development analysis (Figure 1). After CW and BF staining, the cell structure is visualized, which demonstrates the developmental process of both sporangium and spores even after the polysaccharide cell wall degradation (Figure 5). This easy-to-use and low-cost fluorescence imaging method avoids damage from sections and provides intact sporangium for cell lineages analysis. The anticlinal, periclinal, and transverse planes are easily analyzed in this structure, which provides novel information on sporangium development.

Through this fluorescence imaging method, the detailed sporangium developmental process of Pteris was visualized. The clear cell lineages from the sporangial initial cell to stalk, epidermis, inner tapetum, outer tapetum, and sporogenous cells were clearly revealed. We constructed the model of sporangium stalk formation in Pteris, which is different from the previous reports in other Polypodiales. The sporangial initial cell divides into an apical and a basal cell (Figure 2; Wilson, 1958b; Holttum et al., 1970). The stalk was considered to be generated from the basal cell and the capsule is generated from the apical cell in Thelypteridaceae (Holttum et al., 1970). However, in another study, basal cell and apical cell were both reported to contribute to the capsule in Grammitidaceae, Polypodiaceae, and Loxogrammaceae (Wilson, 1958b,1960, 1999). We found that the initial cell undergoes oblique division, and the formed apical cell and basal cell further undergo cell expansion (Figure 2C). Interestingly, the two daughter cells of basal cell occupy about 2/3 of the base space of the sporangium, while one daughter cell of the apical cell above is still the apical cell while the other daughter cell below occupies 1/3 of the base space of the sporangium forming a 3D structure with one cell on the top and three cells on the base (Figure 2C).

The general cell divisions in this study are consistent with the previous reports (Wilson, 1958b,1999; Brown and Lemmon, 1980; Rincón Barón et al., 2011; Long et al., 2016). However, the cell wall of the tapetum and the spore mother cell degraded during meiosis, which makes the actual behavior of these layers difficult to recognize in the sections of the previous investigation (Wilson, 1958b). Compared with the classical sectioning, the fluorescence imaging method can observe the process of cell wall degradation, cytoplasm transformation, and the formation of sporopollenin and lignin (Wilson, 1958a). Therefore, the sporangium development process, including cell wall degradation of the tapetum and the spore mother cells, the transformation of the outer and inner tapetum cytoplasm, formation of sporopollenin wall in spores, and the lignification of annual was visualized (Figures 4E, 5D, 6D). Based on these data, we obtained a model of the development of the sporangium in Pteris. In this model, cell lineages are traced, which are critical for sporangium development.

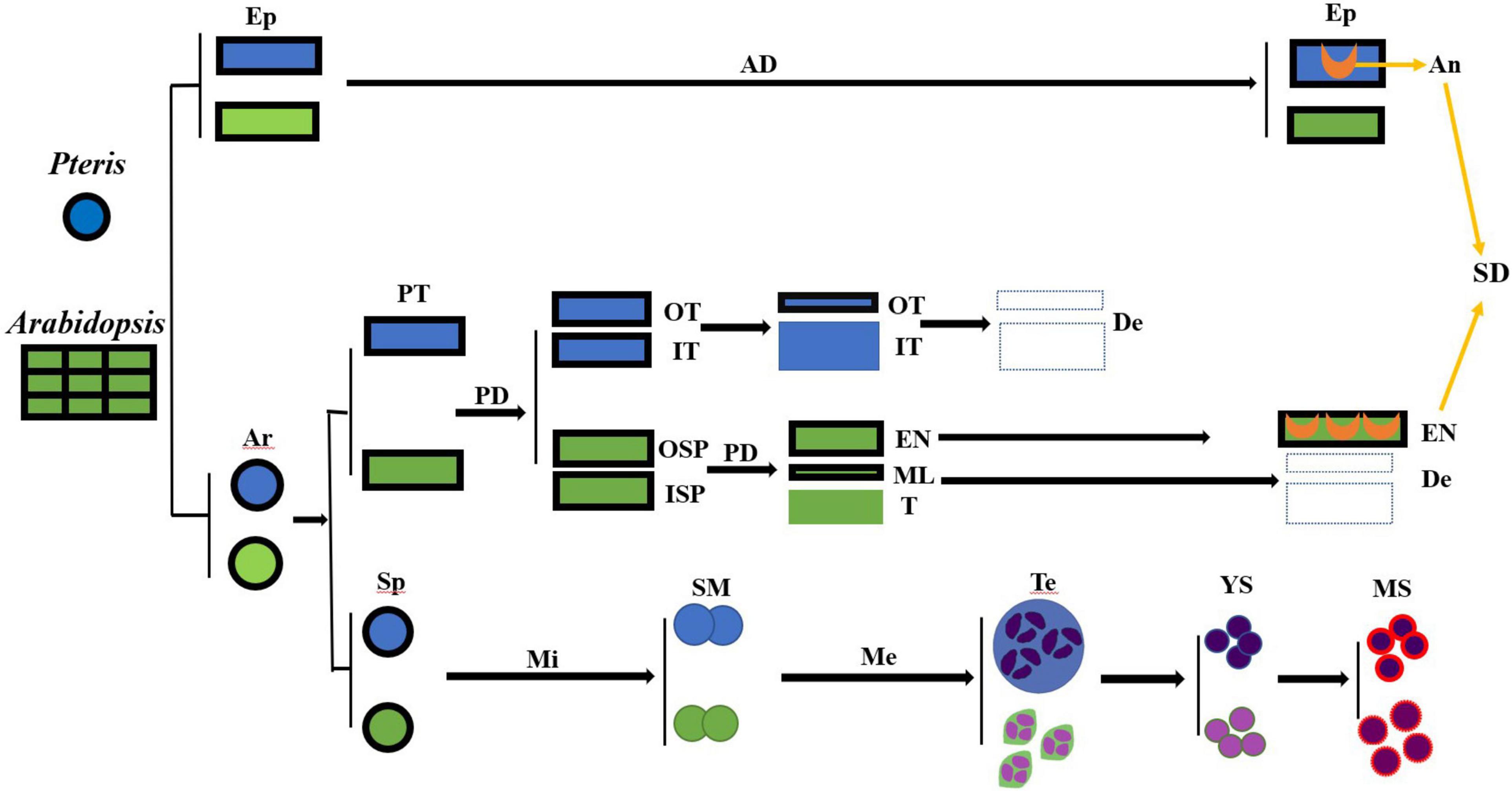

Angiosperms and pteridophytes are currently the two most prosperous vascular plants on earth. Both anthers and sporangia are used for reproductive development. The anther wall of Arabidopsis is divided into the epidermis, endothecium, middle layer, and tapetum. In Pteris, the sporangial wall contains 3 layers, including the epidermis, outer tapetum, and inner tapetum (Figure 3). The inner tapetum cell wall degrades before the meiosis of the spore mother cells, which is similar to the tapetum in angiosperms. The cell wall degradation of the outer tapetum is much later than that of the inner tapetum. Also, this cell layer becomes thinner during meiosis and tetrad stages (Figure 5), which is similar to the middle layer in angiosperm (Figure 7; Xue et al., 2021). The inner tapetum is likely sufficient to support spore development, and the middle layer of seed plants is evolved from the outer tapetum of their ancestors. The epidermis is an important cell layer to protect the sporangia in all the land plants. Most leptosporangiate ferns, including Pteris, have annulus in their epidermis. The lignification of the annulus is important for spore release. The epidermis of most fern plants seems to play roles of protection and spore release. In angiosperms, the epidermis plays a protection role while its lignification for pollen release is undertaken by the endothecium (Wilson, 1958b; Wilson et al., 2011; Noblin et al., 2012; van der Linde and Walbot, 2019). The sporangium development in Pteris and its comparison with Arabidopsis anther development is helpful to the general understanding of plant reproduction.

Figure 7. The cell lineages of the sporangia of Pteris and the anther of Arabidopsis. AD, anticlinal division; An, annulus; TMI, tetrahedral mother initial cell; De, degraded; Ep, epidermis; En, endothecium; ISP, inner secondary parietal cell; IT, inner tapetum layer; Me, meiosis; Mi, mitosis; ML, middle layer; MS, mature spores; OSP, outer secondary parietal cell; OT, outer tapetum layer; PD, periclinal division; PT, primary tapetum layer; SD, sporangia dehiscence; SM, the spore mother cells; Sp, sporogenous cell; T, tapetum; Te, tetrad; YS, young spore.

Sporangia at different development stages were collected from Pteris multifida Poir. grown in the campus of Shanghai Normal University (Shanghai, China) between April 1, 2020, and October 29, 2020. Each fertile leaf has a large number of sporangia at different development stages. For each development stage, at least 3 sporangia were imaged. The voucher specimens (NO.20200401001, NO.20200701001, and NO.20201029001) are deposited in the spore function laboratory herbarium of Shanghai Normal University.

Calcofluor white (CAS: 4404-43-7, Product no. F3543, Sigma) stains the primary cell wall and callose. However, the primary cell wall of the tapetum and the spore mother cells degrade during meiosis and become extremely difficult to discern (Wilson, 1958b). Basic Fuchsin (CAS: 58969-01-0, Product no. B0904, Sigma) stains the phenylpropanoid phenolics. We showed the expression of these pathway genes in tapetum (Xue et al., 2020), and this dye also stains the sporopollenin wall (Jia et al., 2021). Furthermore, these two dyes show non-overlapped emission wavelengths. Thus, we used these dyes for the staining. Toluidine Blue (CAS: 3209-30-1, Product no. 89640, Sigma).

ClearSee solutions were prepared by mixing xylitol powder, sodium deoxycholate, and urea in water as previously described (Kurihara et al., 2015). Sporangia were fixed in ClearSee solution, placed under vacuum for 15 min, and then were treated for two weeks, washed three times in pure water, followed by staining in a mixture of Calcofluor white (0.01M, Sigma)) and Basic Fuchsin (0.001M, Sigma) under 4 degrees in the dark for two days. The sporangia were washed with pure water, and then immediately observed by confocal scanning laser microscopy (objectives were 60x, and lasers were 405nm and 561nm). Sporangia at different developmental stages were fixed overnight in FAA [ethanol 50% (v/v), acetic acid 5.0% (v/v) and formaldehyde3.7% (v/v)], dehydrated in a graded ethanol series (50, 70, 80, 90, 95, and 100% twice), transferred to acetone (100% twice) and embedded in Spurr’s epoxy resin. Sections (1μm) were cut on a Leica UC7. Sections after staining with toluidine blue were taken photographs using an Olympus DX51 digital camera.

For Calcofluor white, we used 405 nm for excitation and the emission spectra were recorded in the range of 418-468 nm. For basic fuchsin, we used 561nm excitation and emission spectra were recorded in the range of 600-650 nm. All fluorescence images were obtained with an Olympus FV3000 laser scanning microscope. The 3D reconstruction was performed by Olympus FV31S-SW.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Z-NY and J-SX conceived and designed the experiments. N-YY, X-LJ, C-XS, and S-YS performed the experiments. N-YY, J-SX, X-LD, and Z-NY analyzed the data. Z-NY, J-SX, and N-YY wrote the manuscript. All authors have read the manuscript and approved it for submission.

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31930009 and 31870296), the Innovation Program of Shanghai Municipal Education Commission (NO. 2019-01-07-00-02-E00006), and the Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (18DZ2260500 and 17DZ2252700).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The authors thank Professor Jian-Guo Cao for the species collected and identified. We thank Professor Quan-Xi Wang and Professor Xian-Chun Zhang for their helpful comments on the manuscript.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2022.878693/full#supplementary-material

Andriankaja, M., Dhondt, S., De Bodt, S., Vanhaeren, H., Coppens, F., De Milde, L., et al. (2012). Exit from proliferation during leaf development in Arabidopsis Thaliana: a not-so-gradual process. Dev. Cell 22, 64–78. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.11.011

Bower, F. O. (1891). Is the eusporangiate or the leptosporangiate the more primitive type in the fern? Ann. Bot. 5, 109–135. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aob.a090629

Bower, F. O. (1910). Studies in the phylogeny of the filicales. I. Plagiogyria. Ann. Bot. 20, 423–450. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aob.a089277

Brown, R., and Lemmon, B. (1980). Ultrastructure of sporogenesis in a moss. Ditrichum pallidum I. meiotic prophase. Bryologist 83, 137–152. doi: 10.2307/3242127

Clark, J., Hidalgo, O., Pellicer, J., Liu, H., Marquardt, J., Robert, Y., et al. (2016). Genome evolution of ferns: evidence for relative stasis of genome size across the fern phylogeny. New Phytol. 210, 1072–1082. doi: 10.1111/nph.13833

Harald Schneider, K. M. P., Smith, A. R., and Wolf, P. G. (2002). “Evolution of vascular plant body plants: a phylogenetic perspective,” in Developmental Genetics and Plant Evolution, eds J. A. Hawkins and R. M. Bateman (Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press), 330–364. doi: 10.1201/9781420024982.ch17

Holttum, R. E., Sen, U., and Mrrtra, D. (1970). Studies in the family Thelypteridaceae II. A comparative study of the type-species of Thelypters schmidel, Cyclosorus link, and Ampelopteris kunze. Blumea 18, 195–215.

Jia, X. L., Xue, J. S., Zhang, F., Yao, C., Shen, S. Y., Sui, C. X., et al. (2021). A dye combination for the staining of pollen coat and pollen wall. Plant Reprod. 34, 91–101. doi: 10.1007/s00497-021-00412-5

Kenrick, P., and Crane, P. R. (1997). The origin and early evolution of plants on land. Nature 389, 33–39. doi: 10.1038/37918

Kurihara, D., Mizuta, Y., Sato, Y., and Higashiyama, T. (2015). ClearSee: a rapid optical clearing reagent for whole-plant fluorescence imaging. Development 142, 4168–4179. doi: 10.1242/dev.127613

Long, H., Li, J., Li, Y. Y., Xie, D. Y., Peng, Q. Z., and Li, L. (2016). Ontogenetic characterization of sporangium and spore of Huperzia serrata: an anti-aging disease fern. Bot. Stud. 57:36. doi: 10.1186/s40529-016-0151-9

Noblin, X., Rojas, N. O., Westbrook, J., Llorens, C., Argentina, M., and Dumais, J. (2012). The fern sporangium: a unique catapult. Science 335: 1322. doi: 10.1126/science.1215985

Oldenhof, H., and Willemse, M. I. M. (1999). Functional compartments during sporangium development in the pteridophyte Cyrtomium Falcatum (L.f.) Presl as expressed in tapetum function. Plant Biol. 1, 99–107. doi: 10.1111/j.1438-8677.1999.tb00715.x

Ouyang, D. W., Ni, X., Xu, H. Y., Chen, J., Yang, P. M., and Kong, D. Y. (2010). Pterosins from Pteris Multifida. Planta Med. 76, 1896–1900. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1249934

Plackett, A. R. G., Di Stilio, V. S., and Langdale, J. A. (2015). Ferns: the missing link in shoot evolution and development. Front. Plant Sci. 6:972. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.00972

PPGI (2016). A community-derived classification for extant lycophytes and ferns. J. Syst. Evol. 54, 563–603. doi: 10.1111/jse.12229

Renzaglia, K., McFarland, K., and Smith, D. (1997). Anatomy and ultrastructure of the sporophyte of Takakia Ceratophylla (Bryophyta). Am. J. Bot. 84:1337. doi: 10.2307/2446132

Riefner, R. E. J., and Smith, A. R. (2016). Pteris Multifida (Pteridaceae rediscovered in southern California (U.S.A.), with a key to species and notes on escaped cultivars. J. Bot. Res. Inst. Tex. 10, 517–525.

Rincón Barón, E. J., Forero Ballesteros, H. G., Gélvez Landazábal, L. V., Torres, G. A., and Rolleri, C. H. (2011). Ontogenia de los estróbilos, desarrollo de los esporangios y esporogénesis de Equisetum Giganteum (Equisetaceae) en los Andes de Colombia. Rev. Biol. Trop. 59, 1845–1858. doi: 10.15517/rbt.v59i4.33190

Sanders, P. M., Bui, A. Q., Weterings, K., McIntire, K. N., Yung-Chao, H., Yun, L. P., et al. (1999). Anther developmental defects in Arabidopsis Thaliana male-sterile mutants. Sex. Plant Reprod. 11, 297–322. doi: 10.1007/s004970050158

Sappl, P. G., and Heisler, M. G. (2013). Live-imaging of plant development: latest approaches. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 16, 33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2012.10.006

Schneider, H. (2013). Evolutionary morphology of ferns (monilophytes). Ann. Plant Rev. Online 45, 115–140. doi: 10.1002/9781119312994.apr0489

Sheffield, E., and Bell, P. R. (1979). Ultrastructural aspects of sporogenesis in a fern, Pteridium aquilinum(L.) Kuhn. Ann. Bot. 44, 393–405. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aob.a085748

Smith, A. R., Pryer, K. M., Schuettpelz, E., Korall, P., Schneider, H., and Wolf, P. G. (2006). A classification for extant ferns. Taxon 55, 705–731. doi: 10.2307/25065646

Truernit, E., Bauby, H., Dubreucq, B., Grandjean, O., Runions, J., Barthelemy, J., et al. (2008). High-resolution whole-mount imaging of three-dimensional tissue organization and gene expression enables the study of Phloem development and structure in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 20, 1494–1503. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.056069

Ursache, R., Andersen, T. G., Marhavy, P., and Geldner, N. (2018). A protocol for combining fluorescent proteins with histological stains for diverse cell wall components. Plant J. 93, 399–412. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13784

van der Linde, K., and Walbot, V. (2019). Pre-meiotic anther development. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 131, 239–256. doi: 10.1016/bs.ctdb.2018.11.001

Warren, H., and Wager, J. (1953). An asplenium prototype of the genus diellia. Bull. Torrey Bot. Club 80, 76–94. doi: 10.2307/2482236

Wilson, K. A. (1958a). Ontogeny of the sporangia in xiphopteris serrulata and pyrrosia nuda. J. Arnold Arbor. 39, 478–493. doi: 10.5962/p.186020

Wilson, K. A. (1958b). Ontogeny of the sporangium of Phlebodium(Polypodium) Aureum. Am. J. Bot. 45, 483–491. doi: 10.1002/j.1537-2197.1958.tb13155.x

Wilson, K. A. (1960). The leptosporangium of the New Zealand fern Anarthropteris dictyopteris. Contributions Gray Herbarium Harvard Univ. 187, 53–59.

Wilson, K. A. (1999). Ontogeny of the sporangia of Sphaeropteris Cooperi. Am. Fern J. 89, 204–214. doi: 10.2307/1547423

Wilson, Z. A., Song, J., Taylor, B., and Yang, C. (2011). The final split: the regulation of anther dehiscence. J. Exp. Bot. 62, 1633–1649. doi: 10.1093/jxb/err014

Xue, J. S., Yao, C., Xu, Q. L., Sui, C. X., Jia, X. L., Hu, W. J., et al. (2021). Development of the middle layer in the anther of Arabidopsis. Front. Plant Sci. 12:634114. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.634114

Xue, J. S., Zhang, B., Zhan, H., Lv, Y. L., Jia, X. L., Wang, T., et al. (2020). Phenylpropanoid derivatives are essential components of sporopollenin in vascular plants. Mol. Plant 13, 1644–1653. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2020.08.005

Yokoyama, A., Yamashino, T., Amano, Y., Tajima, Y., Imamura, A., Sakakibara, H., et al. (2007). Type-B ARR transcription factors. ARR10 and ARR12, are implicated in cytokinin-mediated regulation of protoxylem differentiation in roots of Arabidopsis Thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 48, 84–96. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcl040

Yu, C., Chen, J., and Huang, L. (2013). A study on the antitumour effect of total flavonoids from Pteris Multifida Poir in H22 tumour-bearing mice. Afr. J. Tradit. Complement. Altern. Med. 10, 459–463. doi: 10.4314/ajtcam.v10i6.11

Keywords: fern, sexual reproduction, sporangium development, fluorescence imaging, spore

Citation: Yang N-Y, Jia X-L, Sui C-X, Shen S-Y, Dai X-L, Xue J-S and Yang Z-N (2022) Documenting the Sporangium Development of the Polypodiales Fern Pteris multifida. Front. Plant Sci. 13:878693. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.878693

Received: 09 March 2022; Accepted: 12 April 2022;

Published: 29 April 2022.

Edited by:

Barbara Ambrose, New York Botanical Garden, United StatesReviewed by:

Harald Schneider, Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden (CAS), ChinaCopyright © 2022 Yang, Jia, Sui, Shen, Dai, Xue and Yang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zhong-Nan Yang, em55YW5nQHNobnUuZWR1LmNu; Zhong-Nan Yang, eHVlamluZ3NoaUBzaG51LmVkdS5jbg==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.