94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

REVIEW article

Front. Plant Sci., 14 March 2022

Sec. Plant Cell Biology

Volume 13 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2022.864987

This article is part of the Research TopicMolecular Basis of Asexual Reproduction and its Application in CropsView all 9 articles

In plants, embryogenesis and reproduction are not strictly dependent on fertilization. Several species can produce embryos in seeds asexually, a process known as apomixis. Apomixis is defined as clonal asexual reproduction through seeds, whereby the progeny is identical to the maternal genotype, and provides valuable opportunities for developing superior cultivars, as its induction in agricultural crops can facilitate the development and maintenance of elite hybrid genotypes. In this review, we summarize the current understanding of apomixis and highlight the successful introduction of apomixis methods into sexual crops. In addition, we discuss several genes whose overexpression can induce somatic embryogenesis as candidate genes to induce parthenogenesis, a unique reproductive method of gametophytic apomixis. We also summarize three schemes to achieve engineered apomixis, which will offer more opportunities for the realization of apomictic reproduction.

Reproduction is a fundamental, essential process in plant biology and has great practical significance as much of the food supply is seed-based (Fei et al., 2019). Flowering plants follow one of two pathways for propagation through seeds: sexual and asexual reproduction (Vallejo-Marín et al., 2010). During sexual reproduction, two sperm cells combine with the central cell and the egg cell to produce the endosperm and embryo, respectively, during double fertilization (Dresselhaus et al., 2016). A drawback of sexual reproduction is that advantageous traits segregate randomly into different offspring at each generation, often resulting in the loss of advantageous gene combinations (Spillane et al., 2004; Brukhin, 2017). By contrast, asexual reproduction allows the inheritance of the maternal genome without fertilization or genetic recombination (Koltunow and Grossniklaus, 2003). Apomixis produces seeds that are genetically maternal and represents a natural type of asexual reproduction (Noyes, 2008), and it has tremendous potential in agriculture, in particular to preserve heterosis over multiple generations.

Given the significance of apomixis in crop production and breeding, scientists and breeders have worked to introduce apomixis into agronomically important crops, with some well-documented achievements (Hand and Koltunow, 2014; Sailer et al., 2016). In this review, we describe the classification and mechanisms of apomixis, then summarize the research achievements that are paving the way to the introduction of apomixis into sexually reproducing crops. We also highlight the importance of identifying new genes such as BABY BOOM (BBM) that can lead to somatic embryogenesis, particularly those that may be involved in zygote activation, with the eventual aim of achieving apomixis in agricultural crops.

Apomixis has two basic types: sporophytic and gametophytic. In sporophytic apomixis, embryos develop from the sporophytic cells of the ovule. Sporophytic apomixis is common in citrus plants, in which diploid ovule cells have an embryogenic cell fate and can form multiple globular embryos via mitosis, although their continued development requires the formation of a nutritive endosperm (Hand and Koltunow, 2014). By contrast, in the context of gametophytic apomixis, embryos are derived from the egg cells of diploid or polyploid plants produced by unreduced embryo sacs. Based on the origin of precursor cells that ultimately produce chromosomally unreduced embryo sacs, gametophytic apomixis is subdivided into two types: diplospory and apospory. In diplospory, the precursor is the megaspore mother cell, which undergoes aberrant or suppressed meiosis; in apospory, the precursor is a somatic nucellar cell, resembling the developmental fate of a functional megaspore (Koltunow, 1993; Koltunow and Grossniklaus, 2003; Hand and Koltunow, 2014; Sailer et al., 2016). Gametophytic diplospory has been used in engineered apomixis, whereby diploid or polyploid egg cells are produced by altered or omitted meiosis, referred to as apomeiosis (Hand and Koltunow, 2014). The embryos develop from diploid or polyploid egg cells via parthenogenesis without fertilization, while the endosperm of apomictic species develops either without fertilization in autonomous apomicts or following the induction of fertilization in pseudegamous apomicts (Koltunow, 1993; Koltunow and Grossniklaus, 2003).

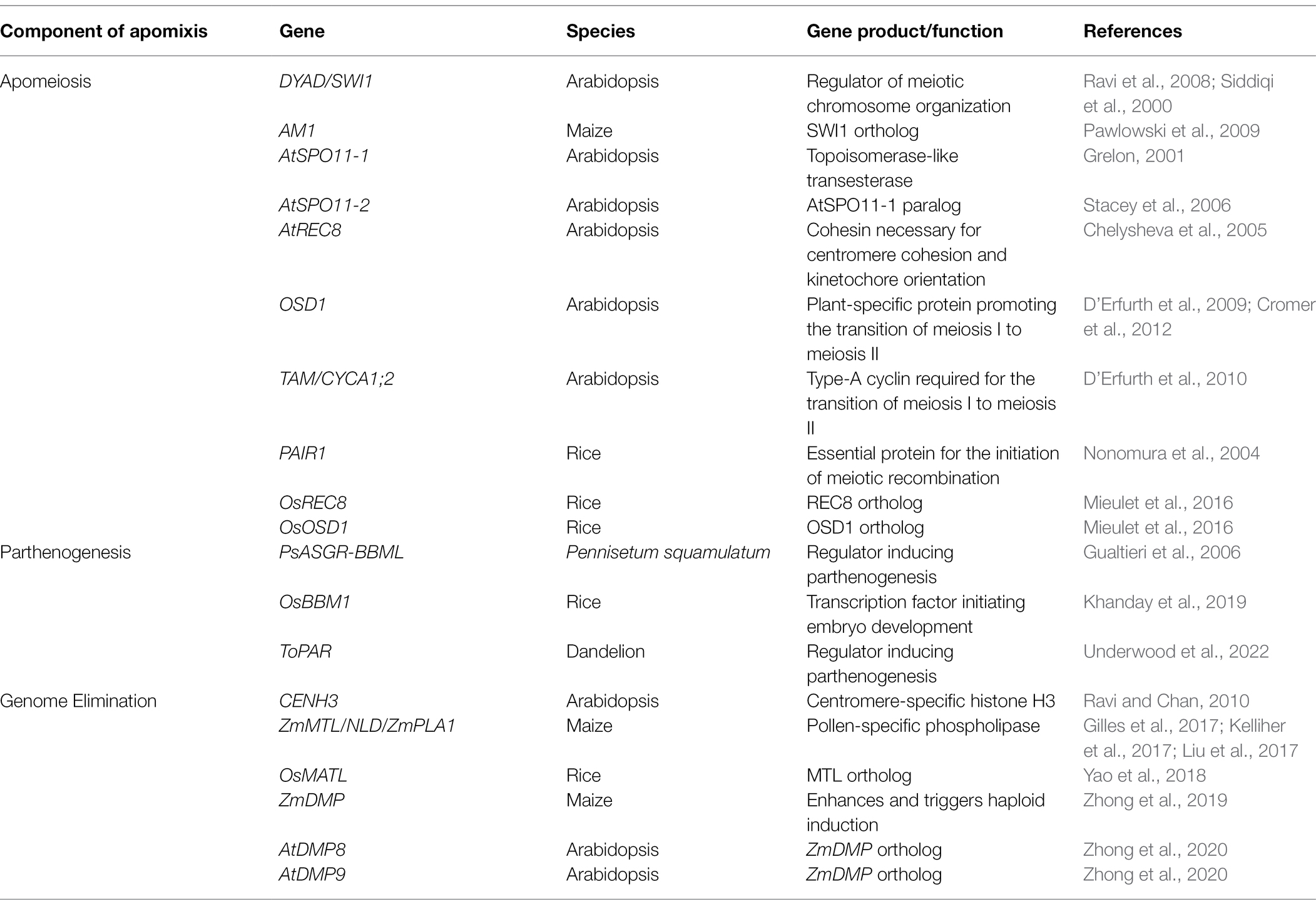

Although apomixis has been documented in over 400 angiosperm species, no major species of agricultural importance are apomictic other than a few fruit crops, such as apple (Malus domestica), citrus, and mango (Mangifera indica; Wang et al., 2017). To introduce apomixis, composite methods combining apomeiosis with parthenogenesis or genome elimination have been used in rice or Arabidopsis. Genes/alleles (Table 1) revealing phenotypes with potential for engineering apomixis have been identified, as outlined below.

Table 1. Genes and their related functions involved in apomeiosis, parthenogenesis, and genome elimination.

Bypassing or altering meiosis during embryo sac formation is a critical step for engineering apomixis in sexual plants. A mutation in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) DYAD (also named SWITCH1) can lead to apomeiosis and produce an unreduced female gamete (Ravi et al., 2008). AMEIOTIC1 (AM1) in maize (Zea mays) is an ortholog of DYAD, and the am1 mutant also displays mitotic-like division rather than a typical meiosis (Pawlowski et al., 2009). The mutation of a single gene in sexual plants can therefore give rise to functional apomeiosis. However, the dyad mutation is unlikely to be a good choice for engineering apomeiosis in crops because of its high rate of sterility.

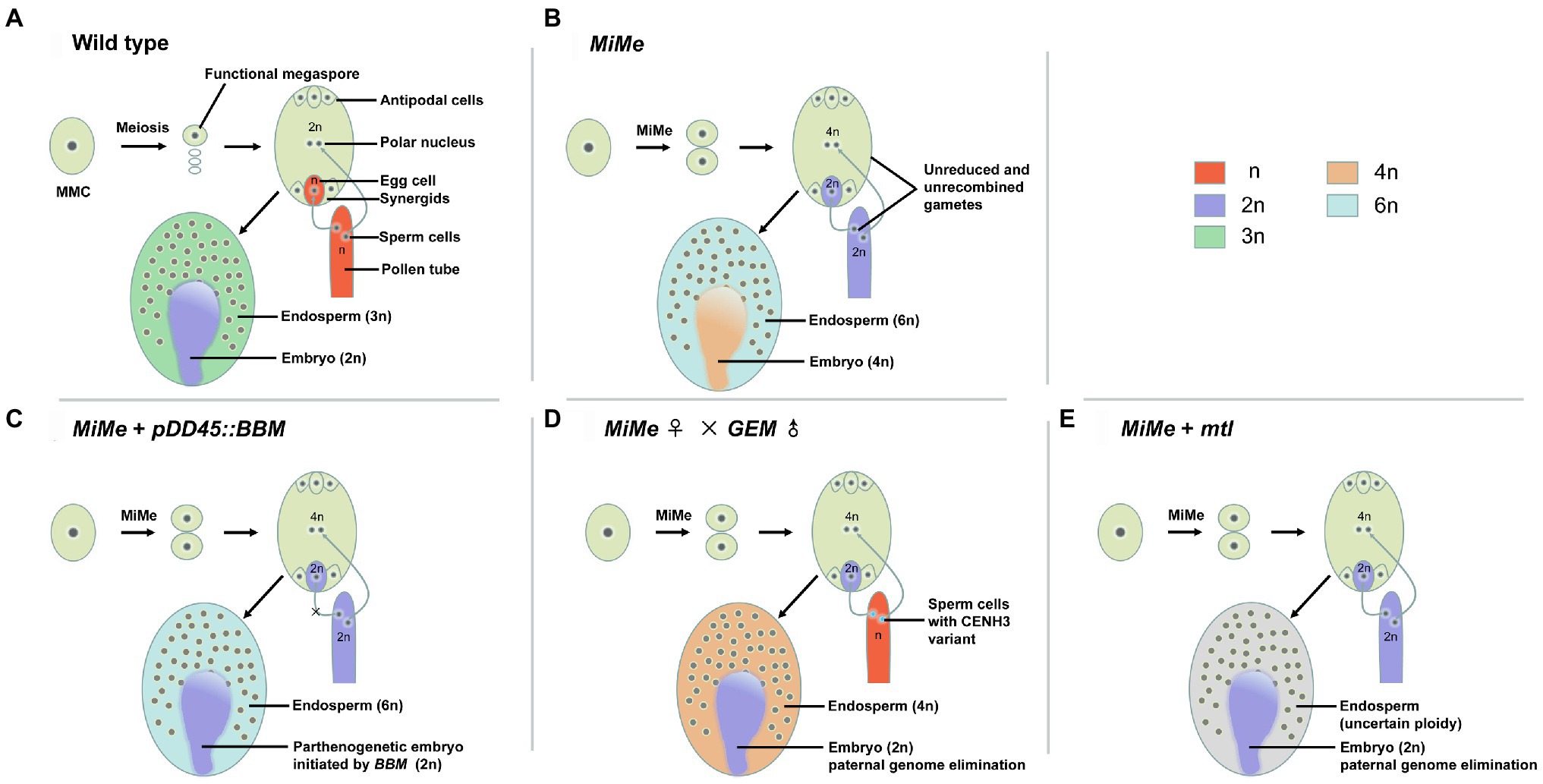

This challenge of high sterility was overcome by the development of an effective method called mitosis instead of meiosis (MiMe). The MiMe genotype, in which meiosis is completely replaced by a mitotic-like division without affecting subsequent sexual processes (Figures 1A,B), was first created in Arabidopsis (D’Erfurth et al., 2009). The MiMe genotype consists of mutations in three meiosis-specific genes: SPORULATION 11–1 (SPO11-1), REC8, and OMISSION OF SECOND DIVISION (OSD1). In addition to these genes, TARDY ASYNCHRONOUS MEIOSIS (TAM), encoding a type-A cyclin, is required for the transition of meiosis I to meiosis II. The tam mutation can substitute for the osd1 mutation to generate a spo11-1 rec8 tam triple mutant and create another triple mutant in which meiosis is replaced by mitosis, called MiMe-2 (D’Erfurth et al., 2010). Similarly, the spo11-1 mutation can be replaced by mutations in other genes, such as PUTATIVE RECOMBINATION INITIATION DEFECT genes (PRD1, PRD2, and PRD3), which are essential for the initiation of meiotic recombination to evoke the MiMe phenotype (Stacey et al., 2006; De Muyt et al., 2007). In addition, mutations in HOMOLOGOUS PAIRING ABERRATION IN RICE MEIOSIS 1 (PAIR1), which is required for homologous chromosome pairing in rice (Oryza sativa) such that meiotic recombination is completely abolished in the pair1 mutant (Nonomura et al., 2004), have been utilized in combination with mutant alleles of Osrec8 and Ososd1 through hybridization to transfer the MiMe approach to rice (Mieulet et al., 2016). With the development of targeted gene-editing technology such as clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)/CRISPR-associated protein 9 (Cas9), MiMe genotypes can be created more expediently without requiring cumbersome hybridization in the intermediate steps (Knott and Doudna, 2018). CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing was used to synchronously knockout three genes in rice, PAIR1, OsREC8, and OsOSD1 (Khanday et al., 2019) or OsSPO11-1, OsREC8, and OsOSD1 (Xie et al., 2019), to produce MiMe phenotypes and achieve apomixis through additional parthenogenesis or an inducer without fertilization.

Figure 1. Illustration of apomixis in wild type and engineering of asexual propagation through seeds based on the MiMe triple mutant. (A) In the wild type, the megaspore mother cell (MMC) undergoes meiosis, leading to the formation of reduced and recombined haploid (n) male and female gametes. Double fertilization of the egg cell and central cell by sperm cells leads to the formation of the embryo (2n) and endosperm (3n), respectively. (B) In the MiMe triple mutant, the MMC undergoes a mitotic-like division (mitosis instead of meiosis, MiMe), leading to the formation of unrecombined and unreduced diploid (2n) gametes. The fusion of the egg cell nucleus (2n) and central polar nucleus (4n) with the sperm cell nucleus (2n) produces a tetraploid (4n) clonal embryo and hexaploid (6n) endosperm, respectively. (C–E) Engineering apomixis has been achieved using three schemes based on the MiMe triple mutant. (C) Combination of the MiMe triple mutant with the ectopic expression of BBM (OsBBM1 in rice) in the egg cell triggers the formation of a parthenogenetic embryo (2n). (D) Crossing the male CENH3-modified genome elimination line (GEM) with the female MiMe triple mutant triggers the formation of a diploid clonal embryo (2n). (E) Creating the MiMe mtl quadruple mutant triggers the formation of a diploid clonal embryo (2n), but the ploidy of the endosperm is not known.

To achieve apomixis, another pivotal step is the autonomous development of an embryo from an egg cell by parthenogenesis. Pennisetum squamulatum, a wild relative of pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum), is a natural apomict, in which apomixis is transmitted by a large non-recombining chromosomal region named the apospory-specific genomic region (ASGR; Ozias-Akins et al., 1998). The ASGR contains multiple copies of PsASGR-BABY BOOM-like (PsASGR-BBML; Gualtieri et al., 2006), a member of the BBML subgroup of the APETALA 2 (AP2) gene family. PsASGR-BBML is expressed in the ovaries, unfertilized egg cells, and developing embryos and can induce parthenogenesis. When BBML is expressed under the control of its own promoter in sexual pearl millet, haploid embryos are produced (Conner et al., 2015). This result highlights the significant role of PsASGR-BBML in parthenogenesis and might be valuable for engineering apomixis in crops. Further studies suggested that PsASGR-BBML can induce parthenogenesis under the control of either its own promoter or an Arabidopsis egg-cell-specific promoter [DOWNREGULATED IN dif1 45 (DD45), At2g21740], which drives gene expression in egg cells in monocot crops, such as maize and rice (Steffen et al., 2007; Lawit et al., 2013; Ohnishi et al., 2014; Conner et al., 2017). The ASGR-BBML genes share high sequence similarity with OsBBM1 (Conner et al., 2015). Unlike PsASGR-BBML, OsBBM1 is expressed in sperm cells but not in egg cells (Khanday et al., 2019). The ectopic expression of OsBBM1 in egg cells under the control of the DD45 promoter can induce parthenogenesis in rice. Recently, the PARTHENOGENESIS (PAR) gene, which encodes a zinc finger domain protein with an EAR (ethylene-responsive element-binding factor-associated amphiphilic repression, DLNxxP) motif, was isolated from apomictic dandelion (Taraxacum officinale). Unlike the recessive sexual alleles, the dominant ToPAR allele is expressed in egg cells and has a conserved miniature inverted-repeat transposable element (MITE) transposon insertion in the promoter. The MITE-containing ToPAR promoter can invoke a PAR homolog from sexual lettuce (Lactuca sativa) to induce parthenogenesis (Underwood et al., 2022). The heterologous expression of the ToPAR gene can also induce embryo-like structures under the control of its own promoter in egg cells of sexual lettuce in the absence of fertilization. Taken together, these findings show that PsASGR-BBML, OsBBM1, and ToPAR are ideal genes for inducing parthenogenesis.

Somatic embryogenesis, a unique pathway for induced asexual reproduction or somatic cloning in vitro that bypasses the fusion of gametes, illustrates the extraordinary capacity for totipotent growth in plant cells (Su et al., 2015, 2020; Horstman et al., 2017). Somatic embryos retain the genotype of the explants and are used to asexually propagate plants to shorten the breeding cycle for species with a long reproductive cycle or highly heterozygous genomes (Park, 2002; Lelu-Walter et al., 2013; Horstman et al., 2017; Su et al., 2020). In Arabidopsis seedlings, somatic embryogenesis can be induced by the ectopic expression of certain transcription factor genes, mainly embryo-identity genes, in the absence of stress or growth regulator treatments. These include the AP2/ETHYLENE RESPONSE FACTOR (ERF) transcription factor gene BBM (Boutilier et al., 2002) and most of the genes encoding the network of LAFL proteins, including the HAP3 family of CCAAT-binding factors composed of LEAFY COTYLEDON 1 (LEC1) and LEC1-LIKE (L1L), and a subgroup of the plant-specific B3 domain protein family including LEAFY COTYLEDON 2 (LEC2), FUSCA3 (FUS3), and ABSCISIC ACID INSENSITIVE 3 (ABI3; Giraudat et al., 1992; Lotan et al., 1998; Luerßen et al., 1998; Stone et al., 2001; Kwong et al., 2003; Jia et al., 2013; Tang et al., 2020). As mentioned earlier, PsASGR-BBML and OsBBM1 can induce parthenogenesis, whereby embryos develop from female gametophytic cells (egg cells). OsBBM1 is expressed in sperm cells (Khanday et al., 2019) and functions as paternal factors that can trigger embryogenesis, perhaps by activating silent maternal transcripts. To date, none of the LAFL genes have been reported to induce parthenogenesis. Whether the other proteins can mimic BBM and confer totipotency to unfertilized egg cells to achieve parthenogenesis remains unknown. Those genes whose overexpression can induce somatic embryogenesis as BBM are considered as candidate genes to induce parthenogenesis.

The aim of engineering apomixis is to retain desirable traits harbored by the uniparental genotype. Genome elimination from a diploid zygote postfertilization may be another means to engineer apomixis. Eliminating one set of maternal or paternal chromosomes after fertilization can therefore achieve haploid induction. In plants, centromere-specific histone H3 (CENH3) can be used to identify the centromeres, chromosomal regions where the spindle microtubules are anchored to mediate chromosome segregation during cell division (Henikoff and Dalal, 2005). cenh3-1 is an embryo-lethal null mutation in Arabidopsis but can be fully complemented by the expression of a transgene encoding a green fluorescent protein (GFP)-tagged CENH3 (GFP-CENH3) fusion protein. In addition, the embryo lethality of cenh3-1 can be rescued using GFP-tailswap, in which the hypervariable N-terminal tail domain of CENH3 is replaced with the tail domain of conventional histone H3. When plants rescued by GFP-tailswap or GFP-CENH3 are used as male or female parents in a cross with the wild-type genotype containing unaltered CENH3, the genomes of the transgenic plants carrying mutant cenh3 are eliminated, and haploid offspring containing the genome of only one parent are generated (Ravi and Chan, 2010). The plants rescued with GFP-tailswap can induce haploids effectively but are largely male-sterile due to the defect in meiosis. Conversely, the GFP-CENH3 transgene mostly rescues fertility, but the frequency of haploid induction is much lower. Subsequently, a CENH3-modified genome elimination (GEM) line was produced, in which GFP-CENH3 and GFP-tailswap are co-expressed to rescue the cenh3-1 mutant. The GEM plants are fully fertile and can be used as either male or female parents in crosses. GEM plants also effectively lead to genome elimination when crossed to plants containing wild-type CENH3. Finally, clonal seeds (doubled haploids) can be generated by crossing the GEM line to male or female MiMe plants in Arabidopsis (Marimuthu et al., 2011).

Haploid induction can also occur spontaneously in nature, albeit infrequently (Gilles et al., 2017), and is routinely used in maize breeding. Recently, the molecular basis of haploid induction in maize was uncovered through fine-mapping and genome sequencing. A frameshift mutation in MATRILINEAL (MTL or MATL), also known as PHOSPHOLIPASE A1 and NOT LIKE DAD (NLD), whose wild-type allele encodes a pollen-specific phospholipase, triggers maternal haploid induction in maize (Gilles et al., 2017; Kelliher et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2017). OsMATL, a putative ZmMTL ortholog, is responsible for maternal haploid induction in rice. A knockout mutation in OsMATL leads to a 2–6% haploid induction rate when these plants are self-pollinated or outcrossed as the male parent (Yao et al., 2018). The underlying mechanism of haploid induction caused by the mutation of MTL remains unclear but may involve the selective elimination of uniparental chromosomes or the continuous chromosome fragmentation that takes place after meiosis in the gametophyte (Zhao et al., 2013; Li et al., 2017). In addition, a mutation in DOMAIN MEMBRANE PROTEIN (DMP), another gene expressed specifically in pollen, can lead to independent haploid induction and significantly improve the haploid induction rate in the presence of mtl in maize (Zhong et al., 2019). MTL is conserved only in monocots, while DMP-like genes exist in both eudicots and monocots and function similarly. Loss-of-function mutations in Arabidopsis DMP8 and DMP9 trigger haploid induction (Zhong et al., 2020). Induction of haploid plants from the genetic disruption of MTL or DMP is another form of paternal genome elimination. It would be possible to produce diploid clonal seeds via the simultaneous engineering of MiMe with loss-of-function in MTL or DMP.

Using the methods mentioned above, the introduction of apomixis into sexual plants has become a reality by combining the MiMe system with other genetic pathways that trigger the formation of uniparental embryos. Three composite methods (Figures 1C–E) are currently in use for triggering apomixis in sexual plants. First, asexual propagation through engineered apomixis can be achieved by combining the MiMe triple mutant with the ectopic expression of rice OsBBM1 in egg cells (Khanday et al., 2019). Using this approach, offspring retaining the same ploidy as the mother plants can be obtained at frequencies of 11–29%. This apomixis is heritable through multiple generations of clones, as demonstrated by whole-genome sequencing. Second, diploid clonal progenies can be generated by crossing the GEM line with male or female MiMe triple mutant plants in Arabidopsis, reaching frequencies of 24% (MiMe as female) or 42% (MiMe as male). The diploid clonal progeny retains the heterozygosity of the MiMe parent, providing evidence of clonal reproduction (Marimuthu et al., 2011). Third, engineered apomixis can be introduced into rice by creating quadruple mutants using the CRISPR/Cas9 system: Osrec8 pair1 Ososd1 Osmatl (named Fix, for Fixation of hybrids; Wang et al., 2019) and Osspo11-1 Osrec8 Ososd1 Osmatl (named AOP, for Apomictic Offspring Producer; Xie et al., 2019), resulting in plants that propagate clonally through their seeds. In this third approach, unreduced clonal female gametes develop into embryos through haploid induction in the absence of the paternal genome. However, the Fix or AOP quadruple mutants display reduced fertility and a low haploid induction rate caused by the mutation in OsMATL; for example, the haploid induction rate in Fix is 4.7–9.5% (Wang et al., 2019; Xie et al., 2019).

Apomixis in crops will not only facilitate the maintenance of elite hybrid genotypes but also shorten the breeding cycle of heterozygous plants to simplify hybrid production strategies. Recent publications have illustrated the diverse components of apomixis (Fayos et al., 2019; Kaushal et al., 2019; Vijverberg et al., 2019; Ozias-Akins and Conner, 2020). In this review, we systematically summarized the types of apomixis that spontaneously occur in nature and focused on inducing apomixis. For engineering apomixis, there are three schemes widely used as: combining MiMe with the ectopic expression of OsBBM1; crossing the CENH3-modified GEM line with MiMe; and creating quadruple mutants containing MiMe and mtl. The MiMe genotype is an effective system for replacing meiosis by mitosis, although it requires the simultaneous genetic inactivation of three genes. This obstacle can be overcome using CRISPR/Cas9 systems by mutating multiple genes without requiring cumbersome hybridization in the intermediate steps. For parthenogenesis, PsASGR-BBML has been verified as the parthenogenesis-inducing gene, following a demonstration of its functionality in sexual pearl millet, maize, and rice. The ectopic expression of OsBBM1 in egg cells can also induce parthenogenesis in rice. Driving the expression of a PAR gene in egg cells of dandelion can bring about parthenogenesis. Whether other proteins can mimic BBM or PAR to achieve parthenogenesis remains unknown. Identifying candidate genes for parthenogenesis, and then transferring this knowledge to crop species for its application to plant breeding, is the goal.

PPY and YHS designed and wrote the manuscript. LPT wrote some parts of the manuscript. XSZ gave valuable comments on the review. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31730008, 31872669, and 32070199) and the Program for Scientific Research Innovation Team of Young Scholar in Colleges and Universities of Shandong Province (2019KJE011).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Boutilier, K., Offringa, R., Sharma, V. K., Kieft, H., Ouellet, T., Zhang, L., et al. (2002). Ecotopic expression of BABY BOOM triggers a conversion from vegetative to embryonic growth. Plant Cell 14, 1737–1749. doi: 10.1105/tpc.001941

Brukhin, V. (2017). Molecular and genetic regulation of apomixis. Russ. J. Genet. 53, 943–964. doi: 10.1134/s1022795417090046

Chelysheva, L., Diallo, S., Vezon, D., Gendrot, G., Vrielynck, N., Belcram, K., et al. (2005). AtREC8 and AtSCC3 are essential to the monopolar orientation of the kinetochores during meiosis. J. Cell Sci. 118, 4621–4632. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02583

Conner, J. A., Mookkan, M., Huo, H., Chae, K., and Ozias-Akins, P. (2015). A parthenogenesis gene of apomict origin elicits embryo formation from unfertilized eggs in a sexual plant. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 112, 11205–11210. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1505856112

Conner, J. A., Podio, M., and Ozias-Akins, P. (2017). Haploid embryo production in rice and maize induced by PsASGR-BBML transgenes. Plant Reprod. 30, 41–52. doi: 10.1007/s00497-017-0298-x

Cromer, L., Heyman, J., Touati, S., Harashima, H., Araou, E., Girard, C., et al. (2012). OSD1 promotes meiotic progression via APC/C inhibition and forms a regulatory network with TDM and CYCA1;2/TAM. PLoS Genet. 8:e1002865. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002865

De Muyt, A., Vezon, D., Gendrot, G., Gallois, J. L., Stevens, R., and Grelon, M. (2007). AtPRD1 is required for meiotic double strand break formation in Arabidopsis thaliana. EMBO J. 26, 4126–4137. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601815

D’Erfurth, I., Cromer, L., Jolivet, S., Girard, C., Horlow, C., Sun, Y., et al. (2010). The cyclin-A CYCA1;2/TAM is required for the meiosis I to meiosis II transition and cooperates with OSD1 for the prophase to first meiotic division transition. PLoS Genet. 6:e1000989. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000989

D’Erfurth, I., Jolivet, S., Froger, N., Catrice, O., Novatchkova, M., and Mercier, R. (2009). Turning meiosis into mitosis. PLoS Biol. 7:e1000124. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000124

Dresselhaus, T., Sprunck, S., and Wessel, G. M. (2016). Fertilization mechanisms in flowering plants. Curr. Biol. 26, R125–R139. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.12.032

Fayos, I., Mieulet, D., Petit, J., Meunier, A. C., Périn, C., Nicolas, A., et al. (2019). Engineering meiotic recombination pathways in rice. Plant Biotechnol. J. 17, 2062–2077. doi: 10.1111/pbi.13189

Fei, X., Shi, J., Liu, Y., Niu, J., and Wei, A. (2019). The steps from sexual reproduction to apomixis. Planta 249, 1715–1730. doi: 10.1007/s00425-019-03113-6

Gilles, L. M., Khaled, A., Laffaire, J. B., Chaignon, S., Gendrot, G., Laplaige, J., et al. (2017). Loss of pollen-specific phospholipase NOT LIKE DAD triggers gynogenesis in maize. EMBO J. 36, 707–717. doi: 10.15252/embj.201796603

Giraudat, J., Hauge, B. M., Valon, C., Smalle, J., Parcy, F., and Goodman, H. M. (1992). Isolation of the Arabidopsis ABI3 gene by positional cloning. Plant Cell 4, 1251–1261. doi: 10.1105/tpc.4.10.1251

Grelon, M. (2001). AtSPO11-1 is necessary for efficient meiotic recombination in plants. EMBO J. 20, 589–600. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.3.589

Gualtieri, G., Conner, J. A., Morishige, D. T., Moore, L. D., Mullet, J. E., and Ozias-Akins, P. (2006). A segment of the apospory-specific genomic region is highly microsyntenic not only between the apomicts Pennisetum squamulatum and buffelgrass but also with a rice chromosome 11 centromeric-proximal genomic region. Plant Physiol. 140, 963–971. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.073809

Hand, M. L., and Koltunow, A. M. G. (2014). The genetic control of apomixis: asexual seed formation. Genetics 197, 441–450. doi: 10.1534/genetics.114.163105

Henikoff, S., and Dalal, Y. (2005). Centromeric chromatin: what makes it unique? Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 15, 177–184. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2005.01.004

Horstman, A., Bemer, M., and Boutilier, K. (2017). A transcriptional view on somatic embryogenesis. Regeneration 4, 201–216. doi: 10.1002/reg2.91

Jia, H., McCarty, D. R., and Suzuk, I. M. (2013). Distinct roles of LAFL network genes in promoting the embryonic seedling fate in the absence of VAL repression. Plant Physiol. 163, 1293–1305. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.220988

Kaushal, P., Dwivedi, K. K., Radhakrishna, A., Srivastava, M. K., Kumar, V., Roy, A. K., et al. (2019). Partitioning apomixis components to understand and utilize gametophytic apomixis. Front. Plant Sci. 10:256. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2019.00256

Kelliher, T., Starr, D., Richbourg, L., Chintamanani, S., Delzer, B., Nuccio, M. L., et al. (2017). MATRILINEAL, a sperm-specific phospholipase, triggers maize haploid induction. Nature 542, 105–109. doi: 10.1038/nature20827

Khanday, I., Skinner, D., Yang, B., Mercier, R., and Sundaresan, V. (2019). A male-expressed rice embryogenic trigger redirected for asexual propagation through seeds. Nature 565, 91–95. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0785-8

Knott, G. J., and Doudna, J. A. (2018). CRISPR-Cas guides the future of genetic engineering. Science 361, 866–869. doi: 10.1126/science.aat5011

Koltunow, A. M. (1993). Apomixis: embryo sacs and embryos formed without meiosis or fertilization in ovules. Plant Cell 5, 1425–1437. doi: 10.2307/3869793

Koltunow, A. M., and Grossniklaus, U. (2003). Apomixis: a developmental perspective. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 54, 547–574. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.54.110901.160842

Kwong, R. W., Bui, A. Q., Lee, H., Kwong, L. W., Fischer, R. L., Goldberg, R. B., et al. (2003). Leafy cotyledon1-like defines a class of regulators essential for embryo development. Plant Cell 15, 5–18. doi: 10.1105/tpc.006973

Lawit, S. J., Chamberlin, M. A., Agee, A., Caswell, E. S., and Albertsen, M. C. (2013). Transgenic manipulation of plant embryo sacs tracked through cell-type-specific fluorescent markers: cell labeling, cell ablation, and adventitious embryos. Plant Reprod. 26, 125–137. doi: 10.1007/s00497-013-0215-x

Lelu-Walter, M.-A., Thompson, D., Harvengt, L., Sanchez, L., Toribio, M., and Pâques, L. E. (2013). Somatic embryogenesis in forestry with a focus on Europe: state-of-the-art, benefits, challenges and future direction. Tree Genet. Genomes 9, 883–899. doi: 10.1007/s11295-013-0620-1

Li, X., Meng, D., Chen, S., Luo, H., Zhang, Q., Jin, W., et al. (2017). Single nucleus sequencing reveals spermatid chromosome fragmentation as a possible cause of maize haploid induction. Nat. Commun. 8:991. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00969-8

Liu, C., Li, X., Meng, D., Zhong, Y., Chen, C., Dong, X., et al. (2017). A 4-bp insertion at ZmPLA1 encoding a putative phospholipase A generates haploid induction in maize. Mol. Plant 10, 520–522. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2017.01.011

Lotan, T., Ohto, M. A., Yee, K. M., West, M. A. L., Lo, R., Kwong, R. W., et al. (1998). Arabidopsis LEAFY COTYLEDON1 is sufficient to induce embryo development in vegetative cells. Cell 93, 1195–1205. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81463-4

Luerßen, H., Kirik, V., Herrmann, P., and Miséra, S. (1998). FUSCA3 encodes a protein with a conserved VP1/ABI3-like B3 domain which is of functional importance for the regulation of seed maturation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 15, 755–764. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1998.00259.x

Marimuthu, M. P. A., Jolivet, S., Ravi, M., Pereira, L., Davda, J. N., Cromer, L., et al. (2011). Synthetic clonal reproduction through seeds. Science 331, 876–876. doi: 10.1126/science.1199682

Mieulet, D., Jolivet, S., Rivard, M., Cromer, L., Vernet, A., Mayonove, P., et al. (2016). Turning rice meiosis into mitosis. Cell Res. 26, 1242–1254. doi: 10.1038/cr.2016.117

Nonomura, K. I., Nakano, M., Fukuda, T., Eiguchi, M., Miyao, A., Hirochika, H., et al. (2004). The novel gene HOMOLOGOUS PAIRING ABERRATION IN RICE MEIOSIS1 of rice encodes a putative coiled-coil protein required for homologous chromosome pairing in MEIOSIS. Plant Cell 16, 1008–1020. doi: 10.1105/tpc.020701

Noyes, R. D. (2008). Sexual devolution in plants: apomixis uncloaked? Bio Essays 30, 798–801. doi: 10.1002/bies.20795

Ohnishi, Y., Hoshino, R., and Okamoto, T. (2014). Dynamics of male and female chromatin during karyogamy in rice zygotes. Plant Physiol. 165, 1533–1543. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.236059

Ozias-Akins, P., and Conner, J. A. (2020). Clonal reproduction through seeds in sight for crops. Trends Genet. 36, 215–226. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2019.12.006

Ozias-Akins, P., Roche, D., and Hanna, W. W. (1998). Tight clustering and hemizygosity of apomixis-linked molecular markers in Pennisetum squamulatum implies genetic control of apospory by a divergent locus that may have no allelic form in sexual genotypes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 95, 5127–5132. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.9.5127

Park, Y. S. (2002). Implementation of conifer somatic embryogenesis in clonal forestry: technical requirements and deployment considerations. Ann. Forest Sci. 59, 651–656. doi: 10.1051/forest:2002051

Pawlowski, W. P., Wang, C. J. R., Golubovskaya, I. N., Szymaniak, J. M., Shi, L., Hamant, O., et al. (2009). Maize AMEIOTIC1 is essential for multiple early meiotic processes and likely required for the initiation of meiosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106, 3603–3608. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810115106

Ravi, M., and Chan, S. W. L. (2010). Haploid plants produced by centromere-mediated genome elimination. Nature 464, 615–618. doi: 10.1038/nature08842

Ravi, M., Marimuthu, M. P. A., and Siddiqi, I. (2008). Gamete formation without meiosis in Arabidopsis. Nature 451, 1121–1124. doi: 10.1038/nature06557

Sailer, C., Schmid, B., and Grossniklaus, U. (2016). Apomixis allows the transgenerational fixation of phenotypes in hybrid plants. Curr. Biol. 26, 331–337. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.12.045

Siddiqi, I., Ganesh, G., Grossniklaus, U., and Subbiah, V. (2000). The dyad gene is required for progression through female meiosis in Arabidopsis. Development 127, 197–207. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.1.197

Spillane, C., Curtis, M. D., and Grossniklaus, U. (2004). Apomixis technology development-virgin births in farmers’ fields? Nat. Biotechnol. 22, 687–691. doi: 10.1038/nbt976

Stacey, N. J., Kuromori, T., Azumi, Y., Roberts, G., Breuer, C., Wada, T., et al. (2006). Arabidopsis SPO11-2 functions with SPO11-1 in meiotic recombination. Plant J. 48, 206–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313x.2006.02867.x

Steffen, J. G., Kang, I.-H., Macfarlane, J., and Drews, G. N. (2007). Identification of genes expressed in the Arabidopsis female gametophyte. Plant J. 51, 281–292. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313x.2007.03137.x

Stone, S. L., Kwong, L. W., Yee, K. M., Pelletier, J., Lepiniec, L., Fischer, R. L., et al. (2001). LEAFY COTYLEDON2 encodes a B3 domain transcription factor that induces embryo development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98, 11806–11811. doi: 10.1073/pnas.201413498

Su, Y. H., Liu, Y. B., Bai, B., and Zhang, X. S. (2015). Establishment of embryonic shoot-root axis is involved in auxin and cytokinin response during Arabidopsis somatic embryogenesis. Front. Plant Sci. 5:792. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2014.00792

Su, Y. H., Tang, L. P., Zhao, X. Y., and Zhang, X. S. (2020). Plant cell totipotency: insights into cellular reprogramming. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 63, 228–243. doi: 10.1111/jipb.12972

Tang, L. P., Zhang, X. S., and Su, Y. H. (2020). Regulation of cell reprogramming by auxin during somatic embryogenesis. aBIOTECH 1, 185–193. doi: 10.1007/s42994-020-00029-8

Underwood, C. J., Vijverberg, K., Rigola, D., Okamoto, S., Oplaat, C., Op den Camp, R. H. M., et al. (2022). A PARTHENOGENESIS allele from apomictic dandelion can induce egg cell division without fertilization in lettuce. Nat. Genet. 54, 84–93. doi: 10.1038/s41588-021-00984-y

Vallejo-Marín, M., Dorken, M. E., and Barrett, S. C. H. (2010). The ecological and evolutionary consequences of clonality for plant mating. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. 41, 193–213. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.110308.120258

Vijverberg, K., Ozias-Akins, P., and Schranz, M. E. (2019). Identifying and engineering genes for parthenogenesis in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 10:128. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2019.00128

Wang, C., Liu, Q., Shen, Y., Hua, Y., Wang, J., Lin, J., et al. (2019). Clonal seeds from hybrid rice by simultaneous genome engineering of meiosis and fertilization genes. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 283–286. doi: 10.1038/s41587-018-0003-0

Wang, X., Xu, Y., Zhang, S., Cao, L., Huang, Y., Cheng, J., et al. (2017). Genomic analyses of primitive, wild and cultivated citrus provide insights into asexual reproduction. Nat. Genet. 49, 765–772. doi: 10.1038/ng.3839

Xie, E., Li, Y., Tang, D., Lv, Y., Shen, Y., and Cheng, Z. (2019). A strategy for generating rice apomixis by gene editing. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 61, 911–916. doi: 10.1111/jipb.12785

Yao, L., Zhang, Y., Liu, C., Liu, Y., Wang, Y., Liang, D., et al. (2018). OsMATL mutation induces haploid seed formation in indica rice. Nat. Plants 4, 530–533. doi: 10.1038/s41477-018-0193-y

Zhao, X., Xu, X., Xie, H., Chen, S., and Jin, W. (2013). Fertilization and uniparental chromosome elimination during crosses with maize haploid inducers. Plant Physiol. 163, 721–731. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.223982

Zhong, Y., Chen, B., Li, M., Wang, D., Jiao, Y., Qi, X., et al. (2020). A DMP-triggered in vivo maternal haploid induction system in the dicotyledonous Arabidopsis. Nat. Plants 6, 466–472. doi: 10.1038/s41477-020-0658-7

Keywords: apomixis, apomeiosis, parthenogenesis, somatic embryogenesis, plant breeding

Citation: Yin PP, Tang LP, Zhang XS and Su YH (2022) Options for Engineering Apomixis in Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 13:864987. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.864987

Received: 29 January 2022; Accepted: 24 February 2022;

Published: 14 March 2022.

Edited by:

Alfred (Heqiang) Huo, University of Florida, United StatesReviewed by:

Joann Acciai Conner, University of Georgia, United StatesCopyright © 2022 Yin, Tang, Zhang and Su. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xian Sheng Zhang, emhhbmd4c0BzZGF1LmVkdS5jbg==; Ying Hua Su, c3V5aEBzZGF1LmVkdS5jbg==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.