- 1Department of Pharmaceutical Botany, School of Pharmacy, Naval Medical University, Shanghai, China

- 2Biomedical Innovation R&D Center, School of Medicine, Shanghai University, Shanghai, China

- 3Institute of Interdisciplinary Integrative Medicine Research, Medical School of Nantong University, Nantong, China

- 4Shanghai Key Laboratory for Pharmaceutical Metabolite Research, Shanghai, China

MicroRNAs (miRNA), recognized as crucial regulators of gene expression at the posttranscriptional level, have been found to be involved in the biological processes of plants. Some miRNAs are up- or down-regulated during plant development, stress response, and secondary metabolism. Over the past few years, it has been proved that miR160 is directly related to the developments of different tissues and organs in multifarious species, as well as plant–environment interactions. This review highlights the recent progress on the contributions of the miR160-ARF module to important traits of plants and the role of miR160-centered gene regulatory network in coordinating growth with endogenous and environmental factors. The manipulation of miR160-guided gene regulation may provide a new method to engineer plants with improved adaptability and yield.

Introduction

MicroRNAs (miRNA) are a class of 20–24 nt small non-coding single-stranded RNAs which are found with high conservation and are widely presented in eukaryotes (Ambros et al., 2003; Bartel, 2004). In plants, RNA polymerase II participates in miRNAs transcription to derive pri-miRNAs, which can fold to form a hairpin structure and be processed by Dicer-like RNase III endonucleases (DCLs). The pri-miRNAs are cut by DCL1/HYL1/SE to produce most of the miRNAs in the nucleus through four processing pathways (short base to loop, sequential base to loop, short loop to base, and sequential loop to base), other DCLs can also be involved in miRNA production (Bologna et al., 2013; Moro et al., 2018; Li and Ren, 2021). The nascent miRNA:miRNA* duplexes generated by DCL-mediated processing will be methylated at the 3′-ends by HUAENHANCER 1 (HEN1). Recent study shows that mature miRNA is mainly bound to the ARGONAUTE (AGO) in RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) in the nucleus and exported to the cytosol by EXPO1. But some miRNA:miRNA* duplexes may be exported by HASTY and assembled in the cytosol (Jones-Rhoades et al., 2006; Bologna et al., 2018; Song et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2019; Brioudes et al., 2021; Cambiagno et al., 2021). Mature miRNAs recognize target messenger RNA (mRNA) sites by perfect or near perfect complementarity, then it can regulate mRNA expression negatively by cleaving it or repressing translation. The correct temporal and spatial accumulation of some highly conserved miRNAs is essential for maintaining the normal development of plants. miR160 is one of miRNAs that regulate the auxin signaling pathways and plays a critical role in various biological processes of plants. Here we reviewed the structures of miR160 family, their targets, expression patterns, and functions in plant development, abiotic/biotic responses, and secondary metabolism.

The miR160 Family and AUXIN RESPONSE FACTORS

MiR160 is a conserved miRNA that is popularly confirmed in many model and non-model plants, such as Arabidopsis, tomato, rice, poplar, and so on. The first miR160 was identified in Arabidopsis and the miR160 family was encoded by three loci (Reinhart et al., 2002). MIR160b and MIR160c were very similar, but they were different from MIR160a (Liu et al., 2010). Recently, a large number of MIR160 homologs have been discovered in land plants and Brassicaceae. MIR160a was considered to be the progenitor of MIR160b and MIR160c paralogs because they originated from the segmental duplication of the region encompassing the ancient prototype MIR160a (Singh and Singh, 2021). The miR160 family has tissue-specific expression due to various functions. In tobacco, miR160 was expressed flower buds and vascular bundles, but no expression signal could be detected in young leaves and seeds (Valoczi et al., 2006). The miR160 family in plants targets the AUXIN RESPONSE FACTORS (ARFs) transcription factors which have been found in the auxin signaling pathways (Li et al., 2016). ARF specifically binds to auxin-responsive elements (AuxREs) TGTCTC in the promoter region of auxin-responsive genes to activate or inhibit gene expression (Tiwari et al., 2003). It can also combine with Aux/indoleacetic acid (IAA) inhibitors to form dimers which are regulated by auxin.

In Arabidopsis, the ARF gene families consisting of 23 loci had been identified to date (Remington et al., 2004). It was reported that miR160 could regulate a group of ARF genes: ARF10, ARF16, and ARF17 (Rhoades et al., 2002). They all had a fragment that could be recognized by miR160 in a conserved N-terminal DNA binding domain (DBD). But ARF17 was different from others because of its poorly conserved C-terminal dimerization domain (CTD) (Tiwari et al., 2003). Recent studies demonstrated that three genes had a significant impact on the development of Arabidopsis. For instance, the increased levels of ARF17 due to the missing of miR160 regulation could contribute to severe developmental abnormalities, such as defects in vegetative, adventitious root (AR), embryonic, and floral development (Sorin et al., 2005). In addition, OsARF18 was found as the target of miR160 in rice (Huang et al., 2016). Many results show that miR160 and its target gene ARF family are important to plant development, anabolism, and abiotic stress.

Regulate the Development of Plants

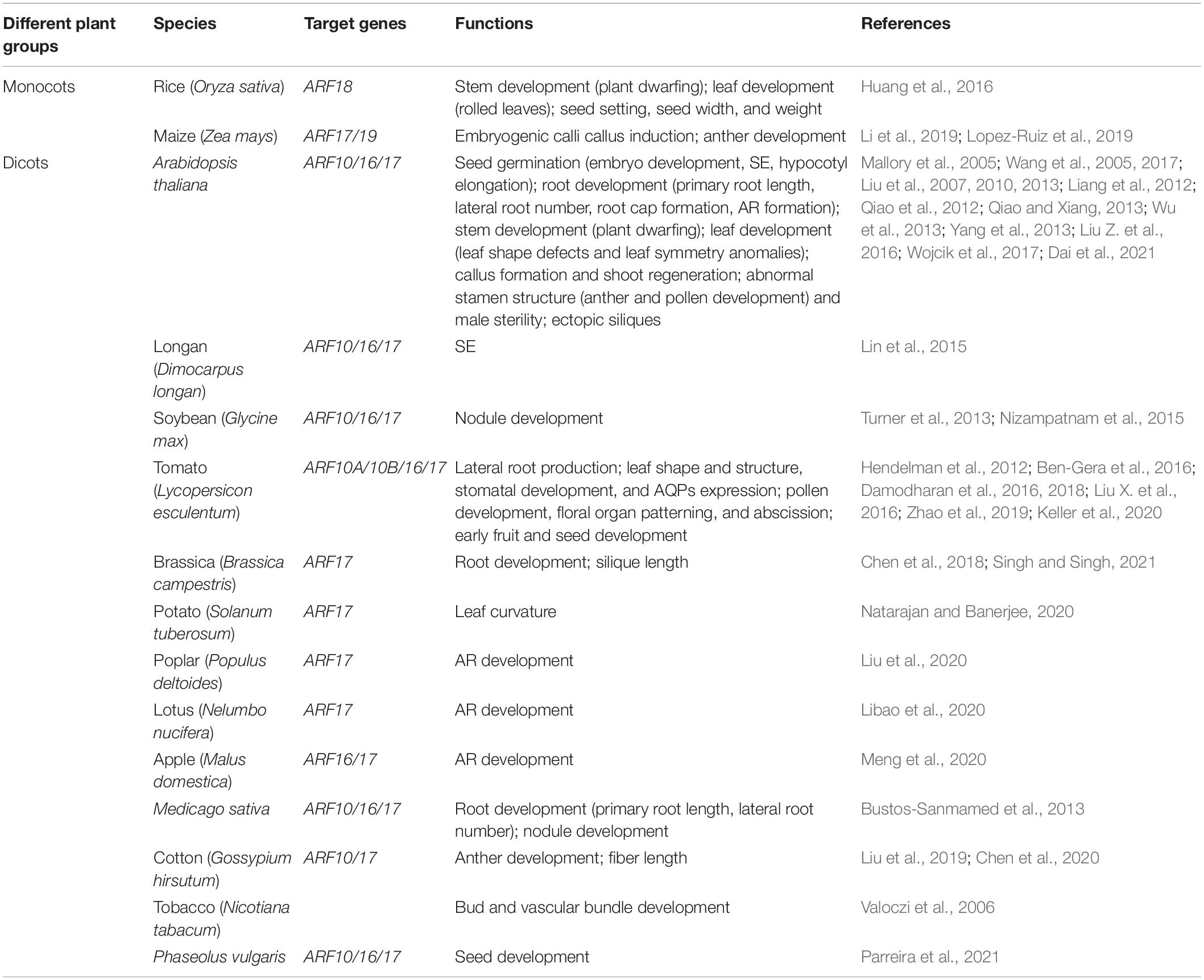

The miR160 family targets the ARF gene involved in the auxin signal transduction pathway, and it is essential for the growth and development of plants (Figure 1A). Different ARF genes mediate auxin signals in different parts, thereby controlling the fate of cell differentiation. ARF is also of great significance for mediating the interaction between auxin and other hormones.

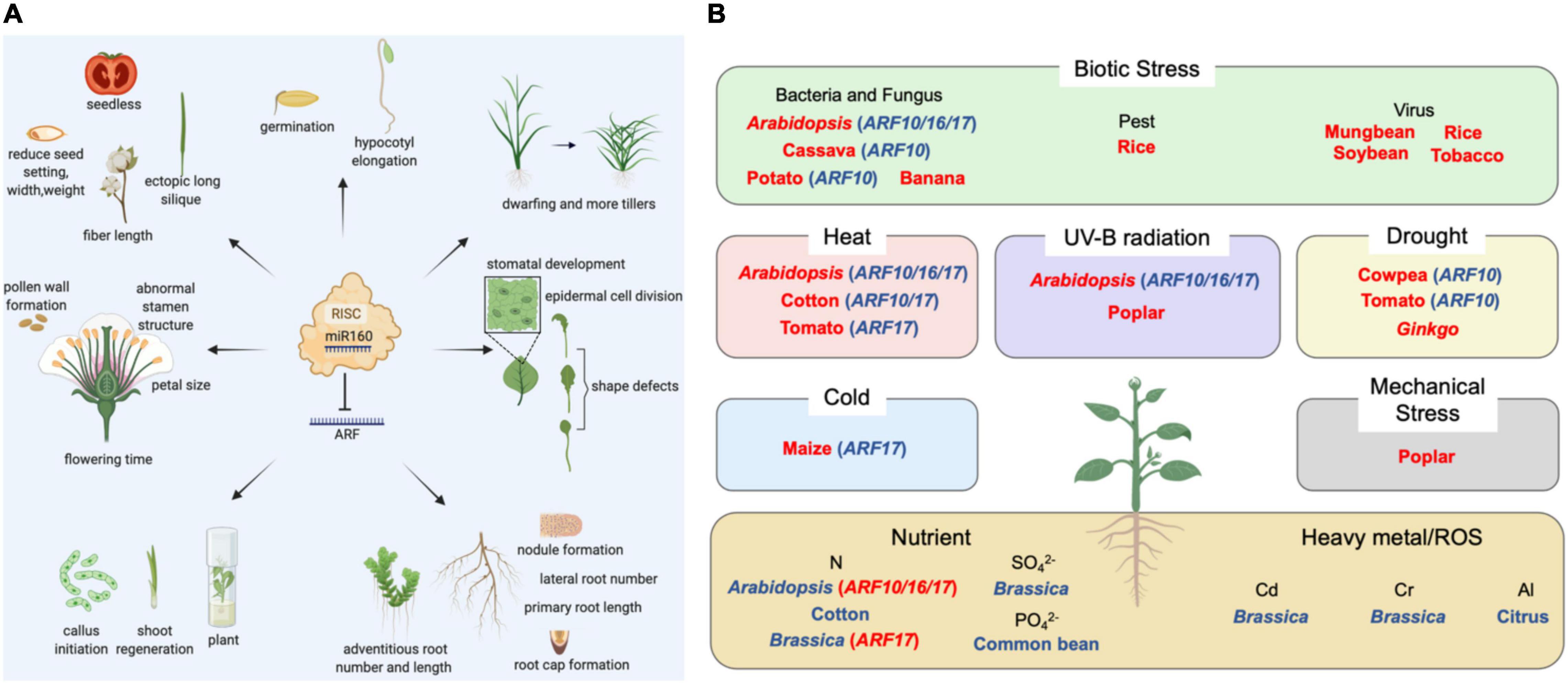

Figure 1. The functions of miR160-ARF module in plants. (A) List of miR160-ARF’s role in various plants during their growth and development. (B) Summary of plant stress responses with miR160 involvement. Blue represents gene down-regulation; red represents gene up-regulation.

Seed Germination

In Arabidopsis, transgenic seeds overexpressing miR160 were less sensitive to abscisic acid (ABA) during germination, but miR160-resistant (mARF10) mutant seeds were hypersensitive to ABA and impaired seedling establishment. The negative regulation of ARF10 by miR160 was crucial to seed germination and post-embryonic development through involving the interactions between ARF10-dependent auxin and ABA pathways (Liu et al., 2007). Moreover, auxin controlled the expression of ABI3 and dramatically released seed dormancy by recruiting the ARF10 and ARF16 during seed germination (Liu et al., 2013). By analyzing the phenotypes of the MIR160a loss-of-function mutants without a 3′ regulatory region, MIR160a and its targets ARF10/16/17 fulfilled a key role in embryo development. Auxin took part in regulating the expression of MIR160a by its 3′ region (Liu et al., 2010). miR160-ARF10/16/17 were also found as a modulator in the cross-talk of auxin, light, gibberellin (GA), and brassinosteroids (BR) during hypocotyl elongation of Arabidopsis. Among them, ARF10 was associated with GA (Dai et al., 2021).

Root Development

The miR160-ARF module has been shown to affect the root development of plants (Barrera-Rojas et al., 2021). In Arabidopsis, ARF17 as a regulator of auxin-inducible GH3-like mRNAs altered the primary root length and lateral root (LR) number (Mallory et al., 2005). ARF10 and ARF16 were considered as a whole controlled root cap formation, although their functions were redundant. In addition, the regulation of ARF16 expression by miR160 was essential for maintaining the LR production (Wang et al., 2005). The same phenomenon was observed in methane-induced tomato LR formation (Zhao et al., 2019). In apple rootstock, over-expressed miR160a reduced ARF16/17 levels and inhibited AR formation, including the number and length (Meng et al., 2020). The miR160-ARF17 module was also an important regulator in the development of AR of poplar and lotus (Libao et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2020). It is important to control the auxin/cytokinin balance during nodule development. In soybean, miR160 negatively regulated ARF10/16/17, and overexpression of miR160 led to hyposensitivity to cytokinin and auxin hypersensitivity, and reduced nodule primordium initiation (Turner et al., 2013). At the later stage of nodule development, high miR160 activity favored auxin activity and promoted the nodule maturation albeit in spite of reduced nodule formation (Nizampatnam et al., 2015). The feedback regulatory loops involving miR160/ARF and auxin/cytokinin governed root and nodule organogenesis, which were also presented in Medicago (Bustos-Sanmamed et al., 2013).

Shoot and Shoot Lateral Organ Growth

Evidence shows that miR160 plays an important role in the normal growth of leaves. In Arabidopsis, the overexpression of mARF (miR160-resistant) or eTM160 (inactivation of miR160) increased the accumulation of ARFs and caused severe leaf developmental defects, including leaf shape defects (serrated leaves) and leaf symmetry anomalies (Mallory et al., 2005; Wu et al., 2013). In tomatoes, miR160 was required for leaflet initiation and controlled the final leaf shape and structure. Both the miR160-targeted ARFs and the Aux/IAA protein SlIAA9/ENTIRE were required to locally inhibit lamellipodia growth between initiating leaflets. They reduced lamina, increased leaf complexity, and decreased auxin response in young leaves (Hendelman et al., 2012; Ben-Gera et al., 2016; Damodharan et al., 2016). Among them, ARF10A was proved indispensable by the knockout of miR160-targeted ARFs, while the functions of ARF16A and ARF17 were redundant (Damodharan et al., 2018). SlARF10 also influenced stomatal development and ABA synthesis/signal response so as to close the stomata under drought. In addition, SlARF10 enhanced hydraulic conductance by directly increasing aquaporin expression. An appropriate ARF10 expression level controlled by miR160 was important to keep the leaf water balance between leaf development and adaptation to water stress (Liu X. et al., 2016). Moreover, miR160 controlled leaf curvature in potatoes by modulating the activity of StTCP4 (involved in cell differentiation) and StCYCLIND3;2 (involved in cell proliferation). The leaves of plants with overexpressed miR160 had a high positive curvature because of prolonged activation of the cell cycle in the center region of leaves. However, the leaves of miR160-knockdown plants were flattened, the StTCP4 activity in both the central and marginal regions of leaves could be responsible for the flattened leaf phenotype (Natarajan and Banerjee, 2020). But the over-accumulation of ARF18 showed rolled leaves in rice due to the anomaly in epidermal cell division in leaves (Huang et al., 2016).

Furthermore, miR160 decreased the accumulation of ARFs in the stem, reduced plant dwarfing, and formed more tillers by fine-tuning auxin signaling in rice (Huang et al., 2016).

Reproductive Development

MiR160 controlled the floral organ growth by targeting ARFs, especially ARF17, in Arabidopsis. The mutants expressing mARF17 had dramatic floral developmental defects, including accelerated flowering time, reduced petal size, altered phyllotaxy along the primary and lateral stems, abnormal stamen structure, and sterility (Mallory et al., 2005). Auxin was vital in plant male reproductive development (Cecchetti et al., 2008; Cardarelli and Cecchetti, 2014). The biosynthesis and transport of auxin were related to anther and pollen formation (Bender et al., 2013). The response of ARF17 to auxin affected both abnormal stamen structure and male sterility, the overexpression of ARF17 led to defects in microsporocytes and tapetum (Wang et al., 2017). But rational ARF17 was essential to pollen wall formation pollen tube growth (Yang et al., 2013). The miR160-ARF17 module associated with anther and pollen development had been found in many other species, such as cotton, tobacco, tomato, and maize (Valoczi et al., 2006; Li et al., 2019; Chen et al., 2020; Keller et al., 2020). In tomatoes, miR160 regulated auxin-mediated floral organ patterning and abscission (Damodharan et al., 2016, 2018).

The miR160-ARF module has a certain regulatory influence on the fruits and seed development of plants. In Arabidopsis, the mARF10 plants produced ectopic siliques with wavy silique walls (Liu et al., 2007). Furthermore, the overexpression of miR160 repressed the ARF10/17 and increased the silique length in Brassica napus (Chen et al., 2018). In tomatoes, overexpressing mARF10 changed the early development of fruits and seeds, resulting in cone-shaped and/or seedless fruit (Hendelman et al., 2012). miR160 negatively regulated ARF17 and the related gene GH3, resulting in the increase of indole-3-acetic acid that is involved in fiber elongation. Finally, the fiber length of cotton was increased (Liu et al., 2019). In rice, ARF18 decreased seed setting, seed width, and seed weight. At the same time, the starch accumulation was significantly reduced (Huang et al., 2016). miR160 inhibited ARF10/16/17, also contributed to the assimilation and allocation of sulfate during seed filling in Phaseolus vulgaris L. (Parreira et al., 2021).

While specific mechanisms are still unclear for many plants, detailed developmental research of various mARFs mutants in Arabidopsis has revealed the contribution of specific family members to reproductive development, proving that they are indispensable for stamen development.

Regeneration Process

Auxin and cytokinin are significantly involved in the regeneration process. In Arabidopsis, miR160 repressed callus initiation and shoot regeneration by cutting ARF10 which was bounded to the ARR15 promoter, repressed ARR15 expression, and promoted the cytokinin response (Qiao et al., 2012; Qiao and Xiang, 2013; Liu Z. et al., 2016). Being essential in LEC2-mediated somatic embryogenesis (SE), the auxin signaling pathway was controlled by miR160 and ARF10/16/17 of Arabidopsis. The repression of miR160 led to the spontaneous formation of somatic embryos and the significant accumulation of auxin in the cultured explants (Wojcik et al., 2017). The similar effects of miR160-ARF16/17 auxin signal transduction could be observed by target mimicry technology during the early stages of longan SE (Lin et al., 2015). At the late embryogenic calli callus induction stages of maize, ARF19 was significantly increased with miR160 being heavily reduced, but their roles in regeneration remained unclear (Lopez-Ruiz et al., 2019).

Role of the miR160 in the Interaction of Plants With the Environment

Abiotic Stress

Abiotic stress is caused by the change of external natural conditions, including cold, heat, drought, high light, mechanical stress, salinity, metals (including heavy metals), nutrient deficiencies, and so on. In the wild, plants are often subjected to a combination of abiotic stresses (Mittler, 2006). It has been found that miR160 is directly associated with plant responses to several stress conditions.

In Arabidopsis, miR160 suppressed ARF10/16/17 expressions to control heat shock protein (HSP) genes levels and regulate thermotolerance (Li et al., 2014; Lin et al., 2018). Accumulating evidence supports a role of the miR160-ARF network in male sterility caused by long-term high temperature (HT) stress. Overexpressing miR160 increased cotton sensitivity to HT stress with the decrease of ARF10/17 mRNA levels, resulting in another indehiscence by activating the auxin response at the sporogenous cell proliferation stage (Ding et al., 2017; Chen et al., 2020). miR160 and ARF17 also regulated the development of transition from post-meiotic to mature pollen in tomatoes under heat stress response (Keller et al., 2020). This gene pair were found to participate in the response to chilling stress in maize as well (Aydinoglu, 2020).

The expressions of several conserved miRNAs were analyzed in two cowpea genotypes during water deficit. miR160a/b has been found strongly upregulated, which inversely correlated to the expression levels of their targets ARF10 (Barrera-Figueroa et al., 2011). In Ginkgo biloba, miR160a decreased ARFs expression and took part in the drought stress tolerance through the IAA signaling pathway (Chang et al., 2020). It is possible that the increase of miR160 and the concomitant decrease of ARF are part of the plant’s strategy to balance water loss and growth under drought.

The exposure to ultraviolet-B (UV-B) can generally cause irreversible damage to DNA, proteins and lipids, and overwhelms antioxidant defense systems in plants because of the excessive production of reactive oxygen species (ROS). A total of 11 putative UV-B-responsive miRNAs, including miR160, were identified by UV-B radiation in Arabidopsis (Zhou et al., 2007). In addition, a set of miRNAs that were responsive to UV-B radiation were found by miRNA filter array assay in P. tremula. miR160 was one of 13 up-regulated miRNAs by UV-B radiation (Jia et al., 2009).

In poplar, miR160 belonged to a pair of mechanical stress-induced miRNAs that may function in one of the most critical defense systems for structural and mechanical fitness (Lu et al., 2005).

It is well known that metals such as Cu, Hg, Cd, Fe, and Al have the potential to induce oxidative stress with the generation of •OH in plants (Shahid et al., 2014). miR160 was transcriptionally down-regulated by metals exposure, Cd stress in B. napus, Cr stress in rice, Al stress in citrus plants, for example (Huang et al., 2010; Dubey et al., 2020; Zhou et al., 2020). On one hand, the low expression of miR160 causes elevated auxin which was required to combat metals stress, on the other hand, ARFs expression enhances adventitious and LR development, which could improve metals tolerance.

In the field, macronutrients and micronutrients are necessary for plants. As a nitrogen-starvation responsive gene, miR160 regulated the establishment of root system architecture through the auxin signaling pathway under nitrogen starvation conditions in plants (Liang et al., 2012; Hua et al., 2020; Singh and Singh, 2021). miR160 could enhance LRs or ARs developments under N-deficiency conditions to maximize the capacity of many plants, such as Arabidopsis, cotton, and B. napus, to uptake the little available nitrogen (Magwanga et al., 2019). In common beans, miR160 was found to be differentially regulated under P-deficiency in different organs. This was conducive to coping with nutrient deficiency stresses (Valdes-Lopez et al., 2010). Thus, miR160 can be used as an engineering target to improve nutrient usage efficiency and reduce fertilizer application.

Biotic Stress

Biotic stress leads to severe damage in plants. Bacterial and fungal pathogen exposure could cause induction of miR160 and downregulation of ARFs to generate defense responses in Arabidopsis (Pst DC3000, Botrytis cinerea), banana (Fusarium oxysporum), and cassava (Colletotrichum gloeosporioides) (Zhang et al., 2011; Pinweha et al., 2015; Xue and Yi, 2018; Cheng et al., 2019). miR160 downregulated ARFs levels and expressions of auxin-response genes (AXR3/IAA17, BDL/IAA12, and GH3-like), and increased callose deposition to activate basal defense PAMP-triggered immunity (Stork et al., 2010). Furthermore, it was also found that miR160 played a crucial part in local defense and systemic acquired resistance response during potato-P. infestans interaction by regulating antagonistic cross-talk between auxin-mediated growth and salicylic acid-mediated defense responses (Natarajan et al., 2018). Moreover, recent studies demonstrated a critical role of miR160 in plant defense against viruses and pests, such as the mosaic virus (Bazzini et al., 2007; Yin et al., 2013; Kundu et al., 2017), rice stripe virus (Du et al., 2011), and brown planthopper (Tan et al., 2020). It may be related to the induction of RNA silencing pathway components.

Participate in Secondary Metabolism

To our knowledge, plant secondary metabolism is an adaptation of plants to the environment, resulting from the plant interactions between biotic and abiotic factors during the long-term evolution process. There are few studies on the regulation of secondary metabolism by miR160, for example, one study showed that the overexpression of miR160a reduced the GH3-like level and negatively regulated the biosynthesis of tanshinones by targeting ARF10/16/17 in Salvia miltiorrhiza hairy roots (Zhang et al., 2020). The miR160-ARF10/16 pathway also regulated terpenoid indole alkaloid biosynthesis (Shen et al., 2017). Recent research suggested that miR160h-ARF18 potentially regulated the accumulation of anthocyanins in poplar, but the exact regulation network remained unclear (Wang et al., 2020).

Conclusion

Plants use a complex variety of transcriptional, post-transcriptional, and translational gene expression programs to survive in the wild. miR160-guided post-transcriptional gene regulation acts a pivotal part in plants. Up to now, rapid and significant progress has been made in miR160 biogenesis, targets prediction, biological functions, and molecular mechanisms. miR160 regulates plant growth and development by interacting with target genes ARFs, a regulatory pathway that is closely related to auxin signal transduction (Table 1). miR160, therefore, can act as a new breeding tool in plant genetic improvement to achieve better agronomic characters. Moreover, there may be feedback regulation between miRNAs and their target genes. Studies have shown that a staggering number of miRNA genes were formed under the control of their targets. Their expression level, duplication status, and miRNA–target interaction were important to the evolution of miRNAs and targets. But little research has been done on the co-evolution of miR160 and ARF (Carthew and Sontheimer, 2009; Huang et al., 2016; Liu T. et al., 2016).

Sessile by nature, plants have to suffer different kinds of abiotic and biotic stresses (Figure 1B). Limited by the resources available, plants always need to control the balance between development and stress responses (Fan et al., 2014). It has been demonstrated that transcription factors are important in the trade-off between development and stresses responses (Pajerowska-Mukhtar et al., 2012). miR160 implicates in multiple regulations of biological processes by regulating ARFs. For example, as the main root and floral regulator, miR160 and its ARF targets were proved to involve in heat stress, drought tolerance and N-deficiency stress (Magwanga et al., 2019; Chen et al., 2020; Dai et al., 2021). By controlling the establishment of the root system architecture of root, the key organ governing water and nutrients uptake, miR160 was able to regulate plants development under N-deficiency condition (Liang et al., 2012). A better understanding of miR160 in stress responses will help us design new strategies to improve the combined stress tolerance of crop plants.

In summary, the miR160-ARF module makes up a crucial hub coordinating developments and physiological responses with endogenous and environmental signals. Its universality among plants and diverse possibilities for modification, together make it a highly promising genetic manipulation target for crop breeding. However, overexpressing ARFs can cause plant dwarfing and leaf deformities, which affects the utilization of plants whose aerial part is the main source of active ingredients. Hence, there is still a lot of work to be done to exploit its biotechnological potentials, such as a new function mining of miR160, upstream regulatory mechanism, and interaction with other non-coding RNAs (long non-coding RNA, lncRNA, and siRNA). We should pay more attention to the function of miR160 in secondary metabolites, which is the key to the formation of good quality crops, especially medicinal plants.

Author Contributions

KH and YWa collected the documents and wrote the manuscript. LZ conceived and developed the idea of this review and designed the overall concept. ZZ, YWu, and RC revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was financially supported by funds from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31970316, 32170274, and 32000231), China National Key Research and Development Program (2017ZX09101002-003-002), and Program of Shanghai Academic Research Leader (19XD1405000).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Biorender (https://biorender.com/) since figures of the review were made by this software.

References

Ambros, V., Bartel, B., Bartel, D. P., Burge, C. B., Carrington, J. C., Chen, X., et al. (2003). A uniform system for microRNA annotation. RNA 9, 277–279. doi: 10.1261/rna.2183803

Aydinoglu, F. (2020). Elucidating the regulatory roles of microRNAs in maize (Zea mays L.) leaf growth response to chilling stress. Planta 251:38. doi: 10.1007/s00425-019-03331-y

Barrera-Figueroa, B. E., Gao, L., Diop, N. N., Wu, Z., Ehlers, J. D., Roberts, P. A., et al. (2011). Identification and comparative analysis of drought-associated microRNAs in two cowpea genotypes. BMC Plant Biol. 11:127. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-11-127

Barrera-Rojas, C. H., Otoni, W. C., and Nogueira, F. T. S. (2021). Shaping the root system: the interplay between miRNA regulatory hubs and phytohormones. J. Exp. Bot. 2, 6822–6835. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erab299

Bartel, D. P. (2004). MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell 116, 281–297. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00045-5

Bazzini, A. A., Hopp, H. E., Beachy, R. N., and Asurmendi, S. (2007). Infection and coaccumulation of tobacco mosaic virus proteins alter microRNA levels, correlating with symptom and plant development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 12157–12162. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705114104

Bender, R. L., Fekete, M. L., Klinkenberg, P. M., Hampton, M., Bauer, B., Malecha, M., et al. (2013). PIN6 is required for nectary auxin response and short stamen development. Plant J. 74, 893–904. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12184

Ben-Gera, H., Dafna, A., Alvarez, J. P., Bar, M., Mauerer, M., and Ori, N. (2016). Auxin-mediated lamina growth in tomato leaves is restricted by two parallel mechanisms. Plant J. 86, 443–457. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13188

Bologna, N. G., Iselin, R., Abriata, L. A., Sarazin, A., Pumplin, N., Jay, F., et al. (2018). Nucleo-cytosolic shuttling of ARGONAUTE1 prompts a revised model of the plant MicroRNA pathway. Mol. Cell. 69, 709.e705–719.e705. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.01.007

Bologna, N. G., Schapire, A. L., Zhai, J., Chorostecki, U., Boisbouvier, J., Meyers, B. C., et al. (2013). Multiple RNA recognition patterns during microRNA biogenesis in plants. Genome Res. 23, 1675–1689. doi: 10.1101/gr.153387.112

Brioudes, F., Jay, F., Sarazin, A., Grentzinger, T., Devers, E. A., and Voinnet, O. (2021). HASTY, the Arabidopsis EXPORTIN5 ortholog, regulates cell-to-cell and vascular microRNA movement. EMBO J. 40:e107455. doi: 10.15252/embj.2020107455

Bustos-Sanmamed, P., Mao, G., Deng, Y., Elouet, M., Khan, G. A., Bazin, J. R. M., et al. (2013). Overexpression of miR160 affects root growth and nitrogen-fixing nodule number in Medicago truncatula. Funct. Plant Biol. 40, 1208–1220. doi: 10.1071/FP13123

Cambiagno, D. A., Giudicatti, A. J., Arce, A. L., Gagliardi, D., Li, L., Yuan, W., et al. (2021). HASTY modulates miRNA biogenesis by linking pri-miRNA transcription and processing. Mol. Plant 14, 426–439. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2020.12.019

Cardarelli, M., and Cecchetti, V. (2014). Auxin polar transport in stamen formation and development: how many actors? Front. Plant Sci. 5:333. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2014.00333

Carthew, R. W., and Sontheimer, E. J. (2009). Origins and mechanisms of miRNAs and siRNAs. Cell 136, 642–655. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.035

Cecchetti, V., Altamura, M. M., Falasca, G., Costantino, P., and Cardarelli, M. (2008). Auxin regulates Arabidopsis anther dehiscence, pollen maturation, and filament elongation. Plant Cell 20, 1760–1774. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.057570

Chang, B., Ma, K., Lu, Z., Lu, J., Cui, J., Wang, L., et al. (2020). Physiological, transcriptomic, and metabolic responses of Ginkgo biloba L. to drought, salt, and heat stresses. Biomolecules 10:1635. doi: 10.3390/biom10121635

Chen, J., Pan, A., He, S., Su, P., Yuan, X., Zhu, S., et al. (2020). Different MicroRNA families involved in regulating high temperature stress response during cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) anther development. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21:1280. doi: 10.3390/ijms21041280

Chen, L., Chen, L., Zhang, X., Liu, T., Niu, S., Wen, J., et al. (2018). Identification of miRNAs that regulate silique development in Brassica napus. Plant Sci. 269, 106–117. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2018.01.010

Cheng, C., Liu, F., Sun, X., Tian, N., Mensah, R. A., Li, D., et al. (2019). Identification of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. cubense tropical race 4 (Foc TR4) responsive miRNAs in banana root. Sci. Rep. 9:13682. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-50130-2

Dai, X., Lu, Q., Wang, J., Wang, L., Xiang, F., and Liu, Z. (2021). MiR160 and its target genes ARF10, ARF16 and ARF17 modulate hypocotyl elongation in a light, BRZ, or PAC-dependent manner in Arabidopsis: miR160 promotes hypocotyl elongation. Plant Sci. 303:110686. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2020.110686

Damodharan, S., Corem, S., Gupta, S. K., and Arazi, T. (2018). Tuning of SlARF10A dosage by sly-miR160a is critical for auxin-mediated compound leaf and flower development. Plant J. 96, 855–868. doi: 10.1111/tpj.14073

Damodharan, S., Zhao, D., and Arazi, T. (2016). A common miRNA160-based mechanism regulates ovary patterning, floral organ abscission and lamina outgrowth in tomato. Plant J. 86, 458–471. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13127

Ding, Y., Ma, Y., Liu, N., Xu, J., Hu, Q., Li, Y., et al. (2017). microRNAs involved in auxin signalling modulate male sterility under high-temperature stress in cotton (Gossypium hirsutum). Plant J. 91, 977–994. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13620

Du, P., Wu, J., Zhang, J., Zhao, S., Zheng, H., Gao, G., et al. (2011). Viral infection induces expression of novel phased microRNAs from conserved cellular microRNA precursors. PLoS Pathog. 7:e1002176. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002176

Dubey, S., Saxena, S., Chauhan, A. S., Mathur, P., Rani, V., and Chakrabaroty, D. (2020). Identification and expression analysis of conserved microRNAs during short and prolonged chromium stress in rice (Oryza sativa). Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 27, 380–390. doi: 10.1007/s11356-019-06760-0

Fan, M., Bai, M. Y., Kim, J. G., Wang, T., Oh, E., Chen, L., et al. (2014). The bHLH transcription factor HBI1 mediates the trade-off between growth and pathogen-associated molecular pattern-triggered immunity in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 26, 828–841. doi: 10.1105/tpc.113.121111

Hendelman, A., Buxdorf, K., Stav, R., Kravchik, M., and Arazi, T. (2012). Inhibition of lamina outgrowth following Solanum lycopersicum AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR 10 (SlARF10) derepression. Plant Mol. Biol. 78, 561–576. doi: 10.1007/s11103-012-9883-4

Hua, Y. P., Zhou, T., Huang, J. Y., Yue, C. P., Song, H. X., Guan, C. Y., et al. (2020). Genome-Wide differential DNA methylation and miRNA expression profiling reveals epigenetic regulatory mechanisms underlying nitrogen-limitation-triggered adaptation and use efficiency enhancement in allotetraploid rapeseed. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21:8453. doi: 10.3390/ijms21228453

Huang, J., Li, Z., and Zhao, D. (2016). Deregulation of the OsmiR160 target gene OsARF18 causes growth and developmental defects with an alteration of auxin signaling in rice. Sci. Rep. 6:29938. doi: 10.1038/srep29938

Huang, S. Q., Xiang, A. L., Che, L. L., Chen, S., Li, H., Song, J. B., et al. (2010). A set of miRNAs from Brassica napus in response to sulphate deficiency and cadmium stress. Plant Biotechnol. J. 8, 887–899. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2010.00517.x

Jia, X., Ren, L., Chen, Q. J., Li, R., and Tang, G. (2009). UV-B-responsive microRNAs in Populus tremula. J. Plant Physiol. 166, 2046–2057. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2009.06.011

Jones-Rhoades, M. W., Bartel, D. P., and Bartel, B. (2006). MicroRNAS and their regulatory roles in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 57, 19–53. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105218

Keller, M., Schleiff, E., and Simm, S. (2020). miRNAs involved in transcriptome remodeling during pollen development and heat stress response in Solanum lycopersicum. Sci. Rep. 10:10694. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-67833-6

Kundu, A., Paul, S., Dey, A., and Pal, A. (2017). High throughput sequencing reveals modulation of microRNAs in Vigna mungo upon Mungbean Yellow Mosaic India Virus inoculation highlighting stress regulation. Plant Sci. 257, 96–105. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2017.01.016

Li, N., and Ren, G. (2021). Systematic characterization of MicroRNA processing modes in plants with parallel amplification of RNA ends. Front. Plant Sci. 12:793549. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.793549

Li, S., Liu, J., Liu, Z., Li, X., Wu, F., and He, Y. (2014). HEAT-INDUCED TAS1 TARGET1 mediates thermotolerance via HEAT STRESS TRANSCRIPTION FACTOR A1a-Directed pathways in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 26, 1764–1780. doi: 10.1105/tpc.114.124883

Li, S. B., Xie, Z. Z., Hu, C. G., and Zhang, J. Z. (2016). A review of Auxin Response Factors (ARFs) in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 7:47. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00047

Li, Z., An, X., Zhu, T., Yan, T., Wu, S., Tian, Y., et al. (2019). Discovering and constructing ceRNA-miRNA-Target gene regulatory networks during anther development in maize. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20:3480. doi: 10.3390/ijms20143480

Liang, G., He, H., and Yu, D. (2012). Identification of nitrogen starvation-responsive microRNAs in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS One 7:e48951. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048951

Libao, C., Minrong, Z., Zhubing, H., Huiying, L., and Shuyan, L. (2020). Comparative transcriptome analysis revealed the cooperative regulation of sucrose and IAA on adventitious root formation in lotus (Nelumbo nucifera Gaertn). BMC Genomics 21:653. doi: 10.1186/s12864-020-07046-3

Lin, J. S., Kuo, C. C., Yang, I. C., Tsai, W. A., Shen, Y. H., Lin, C. C., et al. (2018). MicroRNA160 modulates plant development and heat shock protein gene expression to mediate heat tolerance in Arabidopsis. Front. Plant Sci. 9:68. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.00068

Lin, Y., Lai, Z., Tian, Q., Lin, L., Lai, R., Yang, M., et al. (2015). Endogenous target mimics down-regulate miR160 mediation of ARF10, -16, and -17 cleavage during somatic embryogenesis in Dimocarpus longan Lour. Front. Plant Sci. 6:956. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.00956

Liu, G., Liu, J., Pei, W., Li, X., Wang, N., Ma, J., et al. (2019). Analysis of the MIR160 gene family and the role of MIR160a_A05 in regulating fiber length in cotton. Planta 250, 2147–2158. doi: 10.1007/s00425-019-03271-7

Liu, P. P., Montgomery, T. A., Fahlgren, N., Kasschau, K. D., Nonogaki, H., and Carrington, J. C. (2007). Repression of AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR10 by microRNA160 is critical for seed germination and post-germination stages. Plant J. 52, 133–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03218.x

Liu, S., Yang, C., Wu, L., Cai, H., Li, H., and Xu, M. (2020). The peu-miR160a-PeARF17.1/PeARF17.2 module participates in the adventitious root development of poplar. Plant Biotechnol. J. 18, 457–469. doi: 10.1111/pbi.13211

Liu, T., Fang, C., Ma, Y., Shen, Y., Li, C., Li, Q., et al. (2016). Global investigation of the co-evolution of MIRNA genes and microRNA targets during soybean domestication. Plant J. 85, 396–409. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13113

Liu, X., Dong, X., Liu, Z., Shi, Z., Jiang, Y., Qi, M., et al. (2016). Repression of ARF10 by microRNA160 plays an important role in the mediation of leaf water loss. Plant Mol. Biol. 92, 313–336. doi: 10.1007/s11103-016-0514-3

Liu, Z., Li, J., Wang, L., Li, Q., Lu, Q., Yu, Y., et al. (2016). Repression of callus initiation by the miRNA-directed interaction of auxin-cytokinin in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 87, 391–402. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13211

Liu, X., Huang, J., Wang, Y., Khanna, K., Xie, Z., Owen, H. A., et al. (2010). The role of floral organs in carpels, an Arabidopsis loss-of-function mutation in MicroRNA160a, in organogenesis and the mechanism regulating its expression. Plant J. 62, 416–428. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04164.x

Liu, X., Zhang, H., Zhao, Y., Feng, Z., Li, Q., Yang, H. Q., et al. (2013). Auxin controls seed dormancy through stimulation of abscisic acid signaling by inducing ARF-mediated ABI3 activation in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 15485–15490. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1304651110

Lopez-Ruiz, B. A., Juarez-Gonzalez, V. T., Sandoval-Zapotitla, E., and Dinkova, T. D. (2019). Development-related miRNA expression and target regulation during staggered in vitro plant regeneration of tuxpeno VS-535 maize cultivar. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20:2079. doi: 10.3390/ijms20092079

Lu, S., Sun, Y. H., Shi, R., Clark, C., Li, L., and Chiang, V. L. (2005). Novel and mechanical stress-responsive MicroRNAs in Populus trichocarpa that are absent from Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 17, 2186–2203. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.033456

Magwanga, R. O., Kirungu, J. N., Lu, P., Cai, X., Zhou, Z., Xu, Y., et al. (2019). Map-Based functional analysis of the GhNLP genes reveals their roles in enhancing tolerance to N-Deficiency in cotton. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20:4953. doi: 10.3390/ijms20194953

Mallory, A. C., Bartel, D. P., and Bartel, B. (2005). MicroRNA-directed regulation of Arabidopsis AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR17 is essential for proper development and modulates expression of early auxin response genes. Plant Cell 17, 1360–1375. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.031716

Meng, Y., Mao, J., Tahir, M. M., Wang, H., Wei, Y., Zhao, C., et al. (2020). Mdm-miR160 participates in auxin-induced adventitious root formation of apple rootstock. Sci. Hortic. 270:109442. doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2020.109442

Mittler, R. (2006). Abiotic stress, the field environment and stress combination. Trends Plant Sci. 11, 15–19. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2005.11.002

Moro, B., Chorostecki, U., Arikit, S., Suarez, I. P., Hobartner, C., Rasia, R. M., et al. (2018). Efficiency and precision of microRNA biogenesis modes in plants. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, 10709–10723. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky853

Natarajan, B., and Banerjee, A. K. (2020). MicroRNA160 regulates leaf curvature in potato (Solanum tuberosum L. cv. Desiree). Plant Signal Behav. 15:1744373. doi: 10.1080/15592324.2020.1744373

Natarajan, B., Kalsi, H. S., Godbole, P., Malankar, N., Thiagarayaselvam, A., Siddappa, S., et al. (2018). MiRNA160 is associated with local defense and systemic acquired resistance against Phytophthora infestans infection in potato. J. Exp. Bot. 69, 2023–2036. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ery025

Nizampatnam, N. R., Schreier, S. J., Damodaran, S., Adhikari, S., and Subramanian, S. (2015). microRNA160 dictates stage-specific auxin and cytokinin sensitivities and directs soybean nodule development. Plant J. 84, 140–153. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12965

Pajerowska-Mukhtar, K. M., Wang, W., Tada, Y., Oka, N., Tucker, C. L., Fonseca, J. P., et al. (2012). The HSF-like transcription factor TBF1 is a major molecular switch for plant growth-to-defense transition. Curr. Biol. 22, 103–112. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.12.015

Parreira, J. R., Cappuccio, M., Balestrazzi, A., Fevereiro, P., and Araujo, S. S. (2021). MicroRNAs expression dynamics reveal post-transcriptional mechanisms regulating seed development in Phaseolus vulgaris L. Hortic. Res. 8:18. doi: 10.1038/s41438-020-00448-0

Pinweha, N., Asvarak, T., Viboonjun, U., and Narangajavana, J. (2015). Involvement of miR160/miR393 and their targets in cassava responses to anthracnose disease. J. Plant Physiol. 174, 26–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2014.09.006

Qiao, M., and Xiang, F. (2013). A set of Arabidopsis thaliana miRNAs involve shoot regeneration in vitro. Plant Signal Behav. 8:e23479. doi: 10.4161/psb.23479

Qiao, M., Zhao, Z., Song, Y., Liu, Z., Cao, L., Yu, Y., et al. (2012). Proper regeneration from in vitro cultured Arabidopsis thaliana requires the microRNA-directed action of an auxin response factor. Plant J. 71, 14–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2012.04944.x

Reinhart, B. J., Weinstein, E. G., Rhoades, M. W., Bartel, B., and Bartel, D. P. (2002). MicroRNAs in plants. Genes Dev. 16, 1616–1626. doi: 10.1101/gad.1004402

Remington, D. L., Vision, T. J., Guilfoyle, T. J., and Reed, J. W. (2004). Contrasting modes of diversification in the Aux/IAA and ARF gene families. Plant Physiol. 135, 1738–1752. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.039669

Rhoades, M. W., Reinhart, B. J., Lim, L. P., Burge, C. B., Bartel, B., and Bartel, D. P. (2002). Prediction of plant microRNA targets. Cell 110, 513–520. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00863-2

Shahid, M., Pourrut, B., Dumat, C., Nadeem, M., Aslam, M., and Pinelli, E. (2014). Heavy-metal-induced reactive oxygen species: phytotoxicity and physicochemical changes in plants. Rev. Environ. Contam Toxicol. 232, 1–44. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-06746-9_1

Shen, E. M., Singh, S. K., Ghosh, J. S., Patra, B., Paul, P., Yuan, L., et al. (2017). The miRNAome of Catharanthus roseus: identification, expression analysis, and potential roles of microRNAs in regulation of terpenoid indole alkaloid biosynthesis. Sci. Rep. 7:43027. doi: 10.1038/srep43027

Singh, S., and Singh, A. (2021). A prescient evolutionary model for genesis, duplication and differentiation of MIR160 homologs in Brassicaceae. Mol. Genet. Genomics 296, 985–1003. doi: 10.1007/s00438-021-01797-8

Song, X., Li, Y., Cao, X., and Qi, Y. (2019). MicroRNAs and their regulatory roles in plant-environment interactions. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 70, 489–525. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-050718-100334

Sorin, C., Bussell, J. D., Camus, I., Ljung, K., Kowalczyk, M., Geiss, G., et al. (2005). Auxin and light control of adventitious rooting in Arabidopsis require ARGONAUTE1. Plant Cell 17, 1343–1359. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.031625

Stork, J., Harris, D., Griffiths, J., Williams, B., Beisson, F., Li-Beisson, Y., et al. (2010). CELLULOSE SYNTHASE9 serves a nonredundant role in secondary cell wall synthesis in Arabidopsis epidermal testa cells. Plant Physiol. 153, 580–589. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.154062

Tan, J., Wu, Y., Guo, J., Li, H., Zhu, L., Chen, R., et al. (2020). A combined microRNA and transcriptome analyses illuminates the resistance response of rice against brown planthopper. BMC Genomics 21:144. doi: 10.1186/s12864-020-6556-6

Tiwari, S. B., Hagen, G., and Guilfoyle, T. (2003). The roles of auxin response factor domains in auxin-responsive transcription. Plant Cell 15, 533–543. doi: 10.1105/tpc.008417

Turner, M., Nizampatnam, N. R., Baron, M., Coppin, S., Damodaran, S., Adhikari, S., et al. (2013). Ectopic expression of miR160 results in auxin hypersensitivity, cytokinin hyposensitivity, and inhibition of symbiotic nodule development in soybean. Plant Physiol. 162, 2042–2055. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.220699

Valdes-Lopez, O., Yang, S. S., Aparicio-Fabre, R., Graham, P. H., Reyes, J. L., Vance, C. P., et al. (2010). MicroRNA expression profile in common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) under nutrient deficiency stresses and manganese toxicity. New Phytol. 187, 805–818. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03320.x

Valoczi, A., Varallyay, E., Kauppinen, S., Burgyan, J., and Havelda, Z. (2006). Spatio-temporal accumulation of microRNAs is highly coordinated in developing plant tissues. Plant J. 47, 140–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02766.x

Wang, B., Xue, J. S., Yu, Y. H., Liu, S. Q., Zhang, J. X., Yao, X. Z., et al. (2017). Fine regulation of ARF17 for anther development and pollen formation. BMC Plant Biol. 17:243. doi: 10.1186/s12870-017-1185-1

Wang, J., Mei, J., and Ren, G. (2019). Plant microRNAs: biogenesis, homeostasis, and degradation. Front. Plant Sci. 10:360. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2019.00360

Wang, J. W., Wang, L. J., Mao, Y. B., Cai, W. J., Xue, H. W., and Chen, X. Y. (2005). Control of root cap formation by MicroRNA-targeted auxin response factors in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 17, 2204–2216. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.033076

Wang, Y., Liu, W., Wang, X., Yang, R., Wu, Z., Wang, H., et al. (2020). MiR156 regulates anthocyanin biosynthesis through SPL targets and other microRNAs in poplar. Hortic. Res. 7:118. doi: 10.1038/s41438-020-00341-w

Wojcik, A. M., Nodine, M. D., and Gaj, M. D. (2017). miR160 and miR166/165 Contribute to the LEC2-Mediated auxin response involved in the somatic embryogenesis induction in Arabidopsis. Front. Plant Sci. 8:2024. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.02024

Wu, H. J., Wang, Z. M., Wang, M., and Wang, X. J. (2013). Widespread long noncoding RNAs as endogenous target mimics for microRNAs in plants. Plant Physiol. 161, 1875–1884. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.215962

Xue, M., and Yi, H. (2018). Enhanced Arabidopsis disease resistance against Botrytis cinerea induced by sulfur dioxide. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 147, 523–529. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2017.09.011

Yang, J., Tian, L., Sun, M. X., Huang, X. Y., Zhu, J., Guan, Y. F., et al. (2013). AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR17 is essential for pollen wall pattern formation in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 162, 720–731. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.214940

Yin, X., Wang, J., Cheng, H., Wang, X., and Yu, D. (2013). Detection and evolutionary analysis of soybean miRNAs responsive to soybean mosaic virus. Planta 237, 1213–1225. doi: 10.1007/s00425-012-1835-3

Zhang, H., Chen, H., Hou, Z., Xu, L., Jin, W., and Liang, Z. (2020). Overexpression of Ath-MIR160b increased the biomass while reduced the content of tanshinones in Salvia miltiorrhiza hairy roots by targeting ARFs genes. Plant Cell Tissue Organ. Culture (PCTOC) 142, 327–338. doi: 10.1007/s11240-020-01865-8

Zhang, W., Gao, S., Zhou, X., Chellappan, P., Chen, Z., Zhou, X., et al. (2011). Bacteria-responsive microRNAs regulate plant innate immunity by modulating plant hormone networks. Plant Mol. Biol. 75, 93–105. doi: 10.1007/s11103-010-9710-8

Zhao, Y., Zhang, Y., Liu, F., Wang, R., Huang, L., and Shen, W. (2019). Hydrogen peroxide is involved in methane-induced tomato lateral root formation. Plant Cell Rep. 38, 377–389. doi: 10.1007/s00299-019-02372-7

Zhou, X., Wang, G., and Zhang, W. (2007). UV-B responsive microRNA genes in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol. Syst. Biol. 3:103. doi: 10.1038/msb4100143

Keywords: miR160, ARFs, growth and development, stress response, secondary metabolism

Citation: Hao K, Wang Y, Zhu Z, Wu Y, Chen R and Zhang L (2022) miR160: An Indispensable Regulator in Plant. Front. Plant Sci. 13:833322. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.833322

Received: 17 December 2021; Accepted: 25 February 2022;

Published: 22 March 2022.

Edited by:

Xiaozeng Yang, Beijing Academy of Agricultural and Forestry Sciences, ChinaReviewed by:

Guodong Ren, Fudan University, ChinaCopyright © 2022 Hao, Wang, Zhu, Wu, Chen and Zhang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lei Zhang, c3RhcnpoYW5nbGVpQGFsaXl1bi5jb20=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Kai Hao

Kai Hao Yun Wang2†

Yun Wang2† Lei Zhang

Lei Zhang