95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

REVIEW article

Front. Plant Sci. , 06 October 2022

Sec. Plant Metabolism and Chemodiversity

Volume 13 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2022.1001756

This article is part of the Research Topic Illuminating Carotenoid Synthesis and Plastid Transition in Plants, Volume II View all 6 articles

Yuanyuan Li1

Yuanyuan Li1 Yue Jian1

Yue Jian1 Yuanyu Mao1

Yuanyu Mao1 Fanliang Meng1

Fanliang Meng1 Zhiyong Shao1

Zhiyong Shao1 Tonglin Wang2

Tonglin Wang2 Jirong Zheng2

Jirong Zheng2 Qiaomei Wang1

Qiaomei Wang1 Lihong Liu1*

Lihong Liu1*Plastids are a group of diverse organelles with conserved carotenoids synthesizing and sequestering functions in plants. They optimize the carotenoid composition and content in response to developmental transitions and environmental stimuli. In this review, we describe the turbulence and reforming of transcripts, proteins, and metabolic pathways for carotenoid metabolism and storage in various plastid types upon organogenesis and external influences, which have been studied using approaches including genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabonomics. Meanwhile, the coordination of plastid signaling and carotenoid metabolism including the effects of disturbed carotenoid biosynthesis on plastid morphology and function are also discussed. The “omics” insight extends our understanding of the interaction between plastids and carotenoids and provides significant implications for designing strategies for carotenoid-biofortified crops.

Carotenoids are a group of isoprenoid compounds distributed widely in all photosynthetic organisms (including plants, algae, bacteria) and some non-photosynthetic bacteria and fungi (Sun and Li, 2020; Sun et al., 2022). In plants, carotenoids have both primary (essential) and secondary (specialized) roles (Li et al., 2016b). In green tissues, photosynthesis and photoprotection require carotenoids such as lutein, β-carotene, and violaxanthin (Jia et al., 2022). A majority of carotenoids and their volatile cleavage products give fruits and flowers a distinctive color and flavor to attract pollinating animals (Sandmann, 2021). Meanwhile, carotenoids provide precursors for the biosynthesis of phytohormones abscisic acids (ABA) and strigolactones (SLs) and serve as communication signals with environment as specialized metabolites (Chen et al., 2020). Besides their central roles in plants, carotenoids also play essential roles in human nutrition and health (Torres-Montilla and Rodriguez-Concepcion, 2021). In addition to providing dietary sources of provitamin A (Li et al., 2016a; Giuliano, 2017), they serve as antioxidants that reduce the risk of chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease, cancers, and age-related eye diseases (Rodriguez-Concepcion et al., 2018; Quian-Ulloa and Stange, 2021).

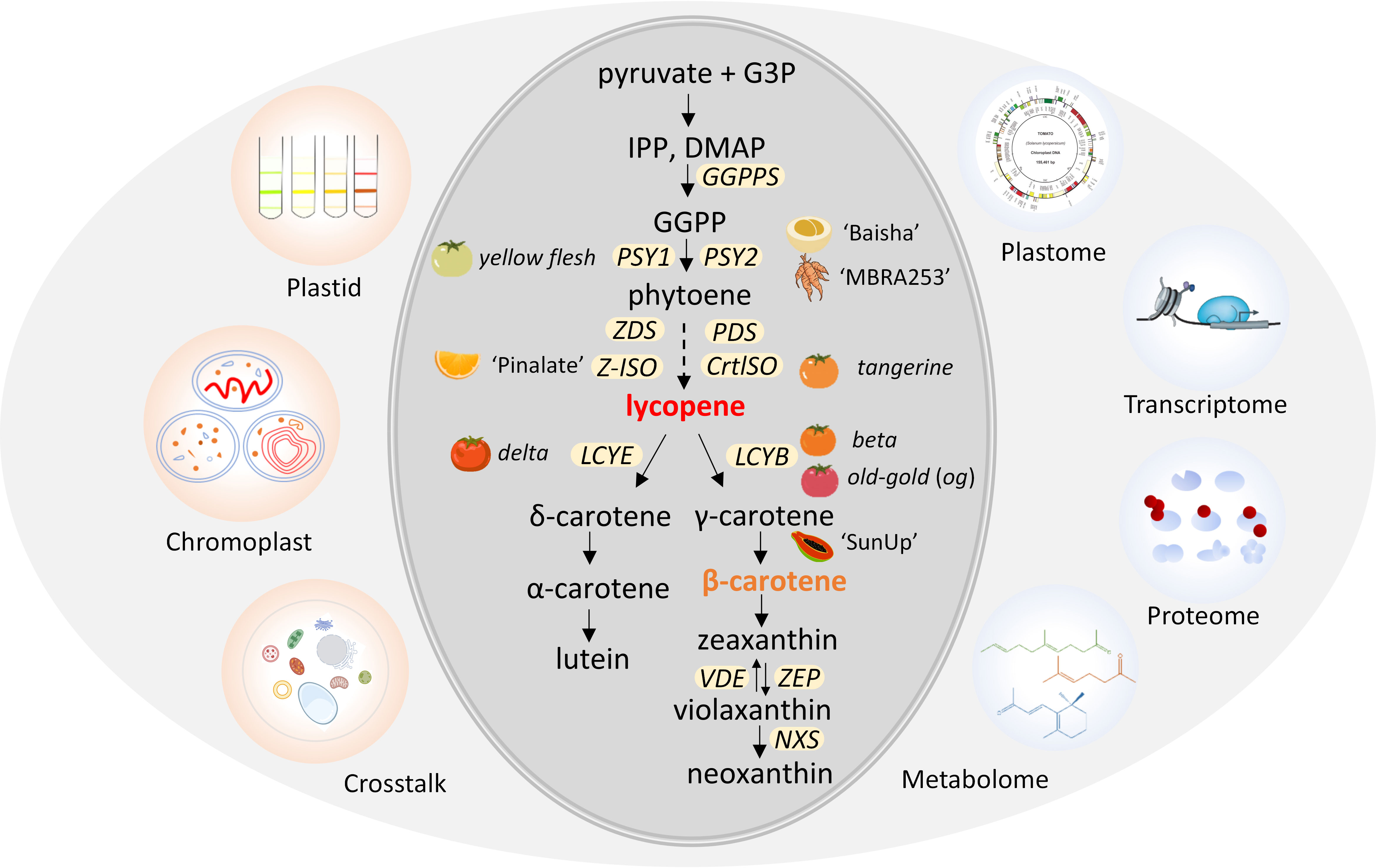

The carotenoid metabolic pathway can be divided into two parts, lycopene production and cyclization (Figure 1). The first bottleneck reaction is bonding two molecules of geranylgeranyl diphosphate (GGPP) by phytoene synthase (PSY) to synthesize the colorless 15-cis-phytoene (Zhou et al., 2022). Then, 15-cis-phytoene is converted into red-colored all-trans lycopene by sequential desaturation and isomerization reactions catalyzed by enzymes PDS, Z-ISO, ZDS and CrtISO (Wurbs et al., 2007). The hydroxylation and epoxidation of the rings in these carotenes generates yellow xanthophylls of lutein in the α-branch by lycopene cyclase (LCYE) and zeaxanthin in the β-branch by LCYB (Garcia-Plazaola et al., 2007). Following hydroxylation of α-carotene and β-carotene by two heme hydroxylases (LUT1/CYP97c1 and LUT5/CYP97a3) and two non-heme carotene hydroxylases (BCH1 and BCH2), yellow xanthophylls of lutein in the α-branch and zeaxanthin in the β-branch are synthesized (Cazzonelli et al., 2020; Sandmann, 2021). Zeaxanthin is epoxidized by zeaxanthin epoxidase (ZEP) and de-epoxidized by violaxanthin de epoxidase (VDE), forming the xanthophyll cycle to protect plants from photo damage (Galpaz et al., 2008; Jia et al., 2022). In the final step, neoxanthin synthase (NXS) converts violaxanthin to neoxanthin (Aluru et al., 2006; Galpaz et al., 2008; Llorente et al., 2017). A variety of species-specific carotenoids are produced by further modifications of carotenes and xanthophylls (Park et al., 2002; Li et al., 2016a). Carotenoid cleavage dioxygenases (CCDs) and 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenases (NCEDs) catalyze carotenoids to apocarotenoid, which can serve as cellular signaling molecules (Priya et al., 2019). The genes and enzymes involved in carotenoid biosynthesis have been isolated and well characterized (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Schematic diagram of carotenoids metabolic pathway and omics in plant plastid. Plastids can be isolated for futher biochemical and molecular characterization via omics, including chromoplast with diverse structures. Plastids possess unique crosstalk mechanisms to synthesize and accumulate massive amounts of carotenoids. Mutants or varieties associated with genes for carotenoid biosynthesis are indicated next to the gene. G3P, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate; IPP, isopentenyl diphosphate; DMAP, dimethylallyl diphosphate; GGPP, geranylgeranyl diphosphate. The yellow ellipses represent carotenoid pathway genes localized in plastids. GGPPS, geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate synthase; PSY, phytoene synthase; PDS, phytoene desaturase; Z-ISO, ζ-carotene isomerase; CrtISO, carotene isomerase; LCYB, lycopene β-cyclase; LCYE, lycopene ϵ-cyclase; VDE, violaxanthin de-epoxidase; ZEP, zeaxanthin epoxidase; NXS, neoxanthin synthase gene; ‘Baisha’, loquat (Eriobotrya japonica); ‘MBRA253’, cassava (Manihot esculenta); ‘Pinalate’, sweet orange (Citrus sinensis); ‘SunUp’, Papaya, (Carica papaya).

The plastids in plant cells are responsible for carotenoid biosynthesis and storage (Fish et al., 2022). Apart from proplastids which are undifferentiated plastids, all other types of plastids are capable of producing carotenoids (Sadali et al., 2019). The etioplast is considered an intermediate stage in the development of chloroplasts in plants grown in the dark (Quian-Ulloa and Stange, 2021). Etioplasts accumulate relatively small amounts of carotenoids along with the chlorophyll precursor protochlorophyllide within structures called prolamellar bodies (PLBs) (Johnson and Stepien, 2016). All green tissues contain chloroplasts, and abundant carotenoids are reside in chloroplast thylakoid for photosynthesis and photoprotection (Klasek and Inoue, 2016). The chromoplast is a carotenoid-accumulation plastid that contributes to the varied color of the organs (Ling et al., 2021). Comparatively, chromoplasts contain a wide variety of carotenoid compounds that are essential for the nutritional and sensory quality of agricultural products. On the basis of carotenoid-lipoprotein sequestering structures, chromoplasts can be classified as globular, crystalline, membraneous, or tubular to accommodate different compositions of carotenoids (Torres-Montilla and Rodriguez-Concepcion, 2021). Despite the importance of carotenoids in maintaining agricultural value and health, the knowledge on their synthesis and accumulation is still limited. The distinctive functions of diverse plastids shape the regulatory networks of carotenoid metabolism and influence their capacities for carotenoid biosynthesis and sequestration, which results in various amounts and types of carotenoids in plant organs (Choi et al., 2021). A variety of biotechnological strategies have been developed to understand carotenoid metabolism and to enrich plant tissues with carotenoids. The advanced “omics” technologies including genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, etc. facilitate our understanding of the carotenoid accumulation in the plastids and aid in the discovery of new genes involved in carotenoid metabolism.

Plastids are organelles with their own prokaryotic genomes, genetic structure, and gene expression (Fish et al., 2022). For the past two decades, numerous plastid genomes (plastome) have been sequenced, conferring substantial information of their organization and evolution (Tonti-Filippini et al., 2017). Plastome containing approximately 100 genes in a 100-220 kb sequence and relatively small (non-coding) intergenic spacer regions, is the most gene-dense among the three genomes of higher plants (Barkan, 2011; Rogalski et al., 2015). At present, over 7731 chloroplast genome sequences of land plants are uploaded in the NCBI GenBank Organelle Genome Resources (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/organelle/), including that of 61 horticultural plants (Table 1). Horticultural plant chloroplast genomes are generally conserved in two types of genes, including the genetic system components (i.e. subunits of an RNA polymerase, rRNAs, tRNAs, and ribosomal proteins) and photosynthetic components (i.e. photosystem I, photosystem II, the cytochrome b6/f complex and the ATP synthase) (Liu et al., 2020; He et al., 2022). Genes coding for catalytic subunit of Clp protease (clpP1), Acyl-CoA carboxylase catalytic subunit (accD) and two putative protein import components (Ycf1 and Ycf2) are consistently retained in most plastome (Ma et al., 2017; Bouchnak and van Wijk, 2021; Rodiger et al., 2021). As a result of this conservation, plastid DNA markers are widely used to establish the phylogeny of many plant groups, such as Rosaceae, Solanaceae and Cucurbitaceae (He et al., 2022; Miao et al., 2022; Zhang Z. et al., 2022). Species boundaries, inter-population variation, and gene flow have also been observed using plastid DNA on a much more local scale. Despite the high conservativeness, plastome size varies between species (Table 1). A detailed plastome provides cis-elements to be engineered and valuable data for analyzing plastid gene expression in the horticulture plant (Bock, 2022; Chen et al., 2022). The plastid has been selected as a “protein factory” for biotechnology applications on account of its protein production efficiency by plastome (Bharadwaj et al., 2019). However, the regulatory circuits that control the expression of these functions remain to be identified.

Plastid genes are highly expressed in chloroplasts but are drastically downregulated in nongreen plastids (Kahlau and Bock, 2008). The genome organization and gene expression in plastids are largely similar to those in bacteria (Zoschke and Bock, 2018). Most plastid genes are operon gene expression with co-transcription pattern. Plastid primary transcripts will be processed successively to generate the mature ones, including cleavage of polycistronic transcripts into oligocistronic or monocistronic isoforms, 5’ and 3’ end processing, intron splicing, and C-to-U editing (Majeran et al., 2012; Bock, 2022). Plastid-encoded RNA polymerase (PEP) and nuclear-encoded plastid RNA polymerase (NEP) transcribe overlapped sets of genes contributing to the complexity of plastid transcription (Koussevitzky et al., 2007). Several plastid genes are predominantly transcribed from PEP or NEP, but many genes have promoters for both RNA polymerases (Pfannschmidt et al., 2015). It is important to understand the regulation and expression of plastid genes through a combination of ChIP-seq and RNA-seq analysis in plastids. The ptChIP-seq can demonstrate the levels of PEP binding to DNA and show the impact of PEP on chloroplast gene expression throu gh a publicly available tool named Plaviso (https://plavisto.mcdb.lsa.umich.edu/) (Palomar et al., 2022).

During tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) fruit ripening and concomitant chloroplast-to-chromoplast transformation, minor changes in plastid RNA accumulation were observed. Whereas, most plastid genes expressions are dramatically downregulated in ripening fruits compared with those in leaves and are translationally downregulated during chromoplast development. With the exception of accD involved in fatty acid biosynthesis, both transcriptional and translational downregulation are pronounced for photosynthetic genes (Kahlau and Bock, 2008). In kiwifruit (Actinidia chinensis cv. Hongyang), several photosynthesis-related genes, as well as most genes associated with the genetic system, were substantially upregulated in green fruits compared to leaves and nearly all plastid genes were significantly downregulated during fruit development (Chen et al., 2022). Although the expression of psbA remained unchanged, the level of psbA protein decreased continuously during chloroplast-to-chromoplast transformation (Chen et al., 2022).

Plastid genome engineering has evolved in transgene expression (Hasunuma et al., 2008). Current plastid research is focused on plastid transformation for biotechnology applications, namely molecular agriculture that adds new agronomic traits, controls metabolic pathways, enhances insect resistance, and agricultural and horticulture-related species (Hasunuma et al., 2008; Rogalski et al., 2015). Plastid transformation is the process of targeting foreign genes to plastids to obtain plants with new traits. The synthetic operon sequence elements that confer processing into monocistronic mRNAs are a safe strategy, and have been successfully applied to a number of metabolic pathways (Lu et al., 2017). Homologous recombination is required for transformation, which facilitates site-specific alteration of endogenous plastid genes and precise targeted insertion of foreign genes into plastid DNA. The carotenoid pathway engineering of plastid genomes by transgene expression has profound advantages over nuclear transformation, including higher levels of heterologous gene expression, materal inheritance for transgene containment, lack of position effects and gene silencing, and the straightforward multigene engineering (Lelivelt et al., 2005; Hasunuma et al., 2008; Yarra, 2020). Some agronomically significant genes have been stably integrated and expressed in plastids, and vegetable crops can be used for the production of industrially important products and increase in nutritional value (Yarra, 2020). In vegetable plants such as tomato, eggplant, potato, carrot, cabbage, lettuce, cauliflower, soybean, and bitter melon, chloroplast transformation is successful (Ruhlman et al., 2006; Zhou et al., 2008; Jo et al., 2011; Ding et al., 2016; Yarra, 2020; Chayut et al., 2021), but only transplastomic tomato and lettuce exhibited an accumulation of foreign proteins (Liu et al., 2020; Ling et al., 2021). Plastid genome engineering has potential applications in molecular agriculture to accumulate carotenoids for better nutrition (Bock, 2022; Singhal et al., 2022). For instance, plastid expression of a bacterial LCYB gene triggers conversion of lycopene to β-carotene, thus resulting in quadrupled pro-vitamin A content in tomato fruits (Wurbs et al., 2007).

The plastome encodes less than 100 ‘autonomous’ genes (Bharadwaj et al., 2019) and remaining 3500 ~ 4000 plastid proteins building and maintaining the functional apparatus are encoded by the nuclear genome (Beck, 2005). The sequential bioprocesses including transcription in the nucleus, translation in the cytosol, the transportation of proteins into the plastid, and protein degradation in the plastid ensure the assembly of the plastid proteome (Egea et al., 2010). High-throughput proteomics is performed upon the tremendous genomics and bioinformatics, and has matured to identify proteins involved in the carotenoids accumulation and the plastid differentiation (Mergner and Kuster, 2022). In addition, various proteomics approaches have been developed and adopted in either whole chloroplast or sub-plastidial fractions (i.e. purified envelope membranes, stroma, and thylakoids) (Subba et al., 2019). There are three main steps in most proteomics technologies, including protein extraction, separation, and identification or quantification (Mergner and Kuster, 2022). These tools paved the way for high-throughput protein localization, quantification, and post-translational modifications (PTMs) analysis in plastids. For example, the Plant Protein Database (http://ppdb.tc.cornell.edu/default.aspx, Sun et al., 2009) presents the most exhaustive plastid proteome available online. And AT_CHLORO is a comprehensive chloroplast proteome database with sub-plastidial localization and curated information on envelope proteins (Bruley et al., 2012). Plastid proteome reveals the general and basic metabolism and function of the chromoplasts and meanwhile bring new insights into its uniqueness.

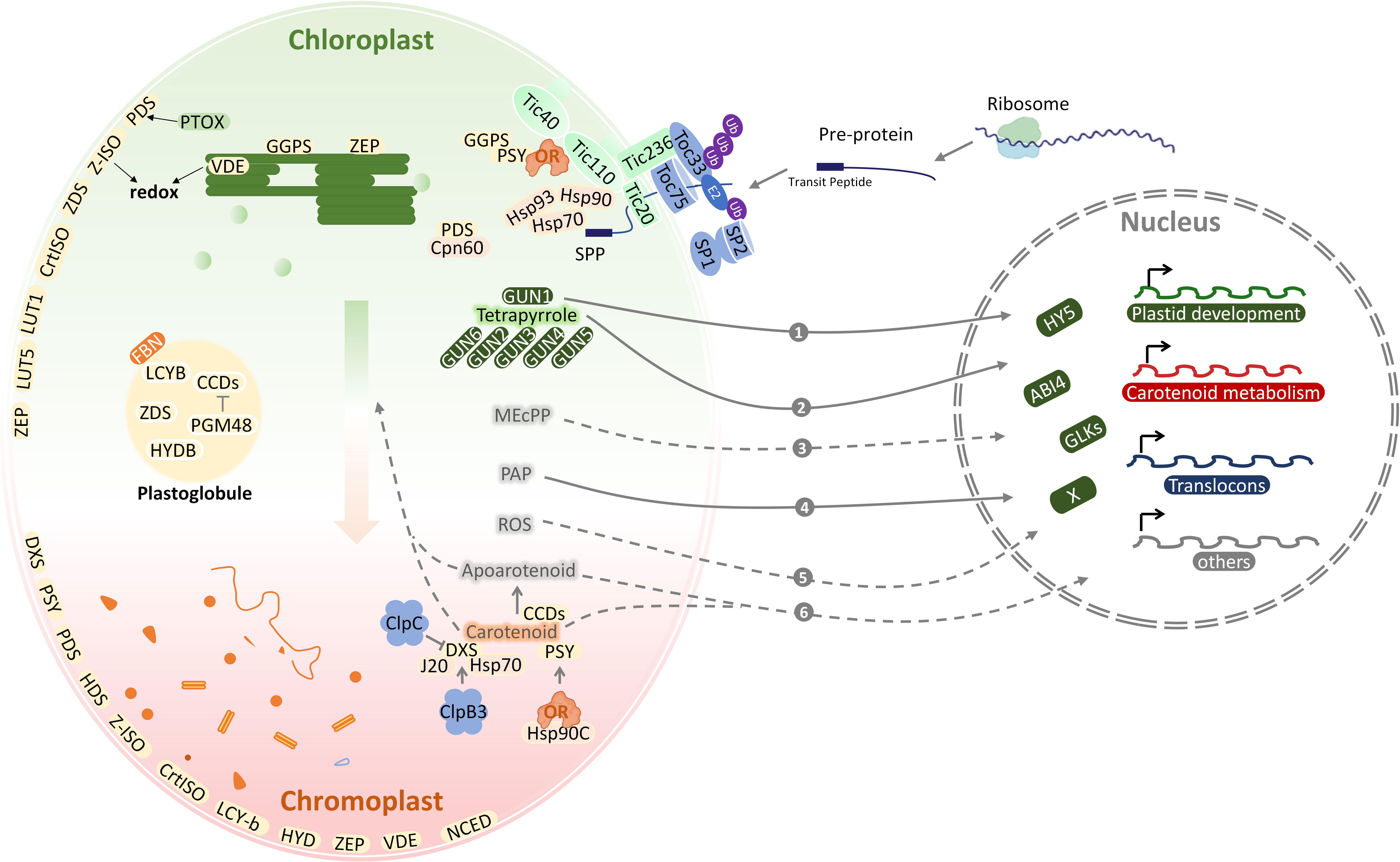

The study of the proteomes in heterotrophic plastids is limited and mainly performed in wheat amyloplasts (Ma et al., 2018), rice etioplasts (von Zychlinski et al., 2005), citrus elaioplast (Zhu et al., 2018) and tobacco proplastids (Sakai et al., 1992). Proteomic analysis of chloroplasts has been extensively studied for many years and has illustrated carotenoid function in chloroplasts (Figure 2) (Joyard et al., 2009). As the major plastids that synthesize and store carotenoids, chromoplasts contain a wide variety of carotenoids in different species and organs (Sun et al., 2018). A number of proteomic studies have been conducted on chromoplasts of fruits and vegetables, which identified 1170 proteins from watermelon (Citrullus lanatus), 1581 proteins from red papaya (Carica papaya), 493 proteins from sweet orange (Citrus sinensis), 1891 proteins from carrot (Daucus carota), 2262 proteins from orange curd cauliflower (Brassica oleracea), 1752 proteins from red bell pepper (Capsicum annuum), and 988 proteins from tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) (Barsan et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2013). Although chromoplast from different horticulture species share similar carotenoids metabolic processes, the distinctive protein distribution patterns were observed in chromoplast proteome, which varies in the morphology of carotenoid-accumulating substructures (Sadali et al., 2019). In addition, 1937 proteins were identified during tomato chloroplast-chromoplast transition (Barsan et al., 2012). Chromoplast proteins differ considerably in relative abundance from the chloroplast proteome, suggesting metabolic processes specific to chromoplasts. As chromoplasts from diverse fruits are derived either from chloroplasts or other non-coloured plastids and possess specific carotenoid-accumulating substructures, chromoplast proteomes from different crops should possess unique characteristics (Ytterberg et al., 2006). Plastoglobule protein profiling from pepper fruit chromoplasts and from Arabidopsis leaf chloroplast has been performed (Nacir and Brehelin, 2013; Wojtowicz and Gieczewska, 2020), yielding around 20 proteins (Rottet et al., 2015), including PSY, ZDS, LCYB, BCH1, BCH2, which suggest plastoglobules are not only involved in the carotenoid biosynthesis but also the carotenoids sequestration (Diretto et al., 2020). Fibrillins (FBNs), which are structural proteins for plastoglobules formation, are identified in various plastids that produce plastoglobules, including chromoplasts, chloroplasts, and elaioplasts (Schwenkert et al., 2018; Zhu et al., 2018). There is a fibril structure in plastoglobules of fruits and petals that accumulate carotenoids and enzymes for carotenoid metabolism (Kim and Kim, 2022).

Figure 2 The coordination of plastid development and carotenoid metabolism. Carotenoid metabolic sink is enhanced during chloroplast-to-chromoplast transition. Locations of carotenoid pathway enzymes within chloroplasts and chromoplasts are shown based on subplastidial proteomic identification. Nucleus-encoded chloroplast proteins are synthesized in the cytosol as pre-proteins and post-translationally imported into the chloroplast through the TOC/TIC translocons. With the integration of retrograde communication with nucleus and protein quality control, the plastid development and carotenoid metabolism adapt to each other. The various molecules involved in retrograde signaling are numbered. ABI4, abscisic acid-insensitive 4; BCH, β-carotene hydrolase; CCD, carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase; Clp, Casein lytic proteinase; Cpn60, chaperonin 60; CrtISO, carotene isomerase; DXS, deoxy-D-xylulose 5-phosphate synthase; E2, E2 conjugase; FBN, Fibrillins; GLK, Golden2-like; GUN, genomes uncoupled; Hsp, Heat shock proteins; HY5, long hypocytol 5; HYDB, β-carotene hydroxylase; IEM, inner envelope membrane; J20, J-Protein 20; MEcPP, methylerythritol cyclodiphosphate; NCED, 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase; OR, ORANGE protein; PAP, 3-phosphoadenosine 5 -phosphate; PGM48, plastoglobule-localized metallopeptidase; PTOX, plastid terminal oxidase; ROS, reactive oxygen species; SP, suppressor of ppi1; SPP, stromal processing peptidase; Tic, translocon at the inner envelope membrane of chloroplasts; Toc, translocon at the outer envelope membrane of chloroplasts; Ub, ubiquitin; VDE, violaxanthin de-epoxidase; ZEP, zeaxanthin epoxidase.

The structural differentiation of the plastids is characterized by the sharp and continuous decrease of thylakoid proteins, while the envelope and matrix proteins remain stable (Majeran et al., 2012). This is related to the photosynthetic mechanism of thylakoids, the destruction of photosystem biogenesis, and the loss of the plastid division mechanism (Galpaz et al., 2008; Joyard et al., 2009). Most of the work related to the plastid proteome has been conducted on chloroplasts, including sub-organelle protein localization for the thylakoid and lumen as well as the stroma, envelope, and plastoglobules (Wojtowicz and Gieczewska, 2020; Zhu et al., 2022). Sub-plastidial proteomic studies locate most carotenogenic enzymes in chloroplast envelopes (Figure 2) (Vishnevetsky et al., 1999; Michel et al., 2021), with ZEP being found both in envelopes and thylakoids, whereas VDE appears only in the latter (Sun et al., 2018). According to proteomic analysis of chloroplasts, lycopene cyclization, responsible for the formation of β-carotene, lutein, and zeaxanthin, occurs in the envelope membranes (Facchinelli and Weber, 2011). As a whole, these data demonstrate that chloroplast envelope membranes participate in carotenoid biosynthesis and metabolism, including the synthesis of precursors from signaling molecules such as ABA (Dong et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2021).

Many proteins translocate from their place of synthesis to plastids or shuttle between different cellular compartments as part of a signal (Thomson et al., 2020). Posttranslational modifications, protein interactions, changes in conformation can modulate localization signals under different conditions (Mergner and Kuster, 2022). In addition, protein targeting mechanisms have been advanced (Zhu et al., 2022). Typically, chloroplast-localized proteins are synthesized as precursors with an N-terminal sign al known as a transit peptide (TP) and delivered to the chloroplast surface by cytosolic chaperones (Fish et al., 2022). Most of these proteins are imported through translocons of the inner and outer membrane of the chloroplast, termed TIC andTOC, respectively (Hoermann et al., 2007). Translocon complexes in envelope membranes facilitate TP entry into the chloroplast via translocon recognition (Figure 2) (Richardson and Schnell, 2020). A stromal processing peptidase (SPP) then cleaves off the TPs of translocated precursor proteins (pre-proteins) (Kmiec et al., 2014), before final folding and assembly in the stroma or further transport to the thylakoids (Chen et al., 2022). For plants such as Arabidopsis, pea, and tomato, the TOC machinery exists in multiple bv forms and plays a key role in precursor protein recognition (Figure 2) (Ganesan and Theg, 2019). This may help to accommodate different proteomes in diverse plastid types, as the majority of proteins in plastids are imported from the cytosol (Fish et al., 2022). It was discovered that this RING-type E3 ligase suppresses the ppi1 locus 1 (SP1) (Ling et al., 2019), which is a TOC33 knock-out mutant with pale yellow phenotypes in Arabidopsis thaliana (Thomson et al., 2020). An important mechanism underlying the transformation of plastids from etioplast to chloroplast and chloroplast to gerontoplast transitions involves direct action of the ubiquitin–proteasome system, and is mediated by SP1 (Ling et al., 2019), which is located in the plastid outer envelope membrane. It has recently been shown that the tomato homologs SP1 and SP1-like2 (SPL2) also play key roles in chloroplast-to-chromoplast transition (Figure 2) (Ling et al., 2021). As tomatoes ripen, the chloroplasts of mature green fruit degrade their chlorophyll and gradually convert to chromoplasts that accumulate large amounts of carotenoids including lycopene and β-carotene, the main precursor of vitamin A (Giuliano, 2017; Ling et al., 2021). The alteration of SlSP1 expression can be attributed to the regulation of plastid protein import by CHLORAD, which in turn regulates the plastid proteome. In agreement with this, knockdown of SP1 or SPL2 delayed the process of chromoplast differentiation (Ling et al., 2021). Different components and isoforms of the TIC machinery mediate the translocation of preproteins through the inner envelope membrane in chloroplast. It remains unclear whether they play a role in the discriminative import of specific precursor proteins into chromoplasts or any other type of plastid.

Additionally, a Ycf2-FTSHi ATPase complex, acting as a motor for pulling preproteins across the inner envelope membrane, was identified as being associated with the TIC machinery (Xing et al., 2022). Orf2971, the ortholog of Ycf2 and, is encoded by the largest gene in chloroplast genome of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (Chlamydomonas throughout) and directly associated with the protein import machinery to ensure the quality of proteins targeted to the chloroplast (Xing et al., 2022). Particularly, Orf2971 interacts with CrTic214 (also called Orf1995 or Ycf1), a protein involved in chloroplast protein translocation, as well as with chaperones like Hsp70 and Cpn60, which direct protein folding or assembly (Bonk et al., 1996; Bonk et al., 1997). TOC33 belong to the TOC complex, which contains cytosol-projecting GTPase domains that bind to preprotein TPs (Kessler and Schnell, 2006). TOC75, the β-barrel protein, is responsible for translocating pre-proteins through the outer envelope membrane. A continuous chaperoned passage for preprotein translocation across the intermembrane space is provided by TIC236 and POTRA domains of TOC75 (Chen Y. L. et al., 2018). Other mechanisms may ensure inward transport, such as increased affinity for transit-peptides or stromal ATPase motors (Ling et al., 2019). Different components and isoforms of the TIC machinery mediate the translocation of preproteins through the inner envelope membrane. It remains unclear whether they play a role in the specific import of certain precursor proteins into chromoplasts or other kinds of plastid.

Plastid proteome changes are associated with or caused by chromoplast differentiation (Kahlau and Bock, 2008). Proteomic studies have shown that proteins involved in photosynthesis are typically reduced following the chloroplast-to-chromoplast transition, whereas many non-photosynthetic plastid proteins, including those linked to the biosynthesis of carotenoids, vitamins, hormones, and aroma volatiles, are accumulated (Moreno, 2018). Proteomics has identified several key proteins as well as regulatory mechanisms, including protein import, quality control, and structural proteins. After protein introduction, nuclear encoded plastid protein transport peptides are cleaved by specific proteases, and mature proteins are folded, assembled into complexes, or transmitted to their target sites in plastids through the complex network of plastid chaperones (Figure 2) (Torres-Montilla and Rodriguez-Concepcion, 2021). Molecular chaperones and proteases also form a protein quality control (PQC) system to ensure the stability, refolding or degradation of mature proteins (Rochaix, 2022). Plastid PQC components include chaperones, such as heat shock proteins Cpn60, Hsp70, and Hsp100, and proteases Clp, Lon, Deg, and FstH (Torres-Montilla and Rodriguez-Concepcion, 2021). Our understanding of the PQC system mainly comes from the model of chloroplast. Genetic manipulation of these components in tomato and other crops changes their carotenoid content and affects chromoplast differentiation (Torres-Montilla and Rodriguez-Concepcion, 2021).

Among the molecular chaperones, a well-studied one affecting chromoplasts differentiation is ORANGE (Lopez et al., 2008), and increased carotenoid accumulation was observed in OR mutants of cauliflower and melon (Lu et al., 2006; Chayut et al., 2021). Heterologous overexpression of OR increases carotenoid accumulation by promoting chromoplasts differentiation (Lopez et al., 2008; Welsch et al., 2019). PSY is the first rate-limiting enzyme in carotenoid metabolism, and OR acts as a molecular chaperone to prevent PSY degradation (Lu et al., 2006). In addition, OR also affects carotenoid accumulation and chromoplasts differentiation through other mechanisms (Giuliano, 2017). It plays a role in protein input by physically interacting with many components in the TIC machine, including TIC40 and TIC110 (Yuan et al., 2021). OR also interferes with the interaction between TIC40 and TIC110 by reducing the turnover of TIC40 (Fish et al., 2022), and reducing the binding of pre-protein and TIC110, thereby carrying out protein translocation and processing (Yuan et al., 2021). The OR of a “golden SNP” (ORHis) in melon fruit prevents the conversion of β-carotene to downstream products (Chayut et al., 2017; Giuliano, 2017). ORHis promotes chromoplast differentiation when overexpressed in tomato fruit (Yazdani et al., 2019). Increased chromoplast number and size enhances carotenoid metabolic strength, such as increased total carotenoid levels in fruits of tomato high pigment1 (hp1) mutant (Galpaz et al., 2008; Kilambi et al., 2013). In addition to promoting carotenoid biosynthesis and chromoplasts biogenesis, ORHis also functions in regulating the number of chromoplast (Sun et al., 2020). In Arabidopsis, both ARC3 and PARC6 are key regulators of plastid division, and ORHis limits the number of chromoplasts by interacting with ARC3 to interfere with its binding to PARC6 (Sun et al., 2020). Overexpression of ORHis did not alter the number or ultrastructure of chloroplasts, and the direct interaction of OR with TCP14 inhibited its transactivation activity and ultimately suppressed the etioplast-to-chloroplast transition during desulfurization in Arabidopsis seedlings (Sun et al., 2020). The study of molecular chaperone OR has paved the way for further unravelling the molecular mechanism of carotenoid accumulation in plastids. In plastids, the Clp protease system is the main mechanism for removing improperly folded proteins and inhibiting toxic protein aggregate formation (Welsch et al., 2018). The Clp complex has two domains: a proteolytic core consisting of two loops formed by the ClpP and ClpR subunits, and a chaperone loop formed by the ClpC and ClpD subunits responsible for transporting substrates into the proteolytic compartment (Welsch et al., 2018). The Clp protease complex controls DXS, PSY and other enzymes involved in carotenoid biosynthetic pathway (Sun et al., 2018). In tobacco, higher levels of carotenoid biosynthesis enzymes were observed in plants with deletions of subunits of the catalytic core of Clp (such as ClpR1) or the chaperone loop (such as ClpC1), suggesting that these enzymes are direct targets of proteases (Welsch et al., 2018). However, carotenoid levels were not increased in leaves of these lines, as defective Clp protease function also affects chloroplast development and thus alters carotenoid deposition sites (D’Andrea et al., 2018). Knockdown of ClpR1 in tomato fruit inhibited the activity of Clp protease and increased the levels of DXS and PSY proteins in chromoplasts (D’Andrea et al., 2018). ClpR1-deficient tomato fruits show increased expression of plastid chaperones genes, with a similar phenomenon observed in Clp protease-deficient Arabidopsis mutants, which may be a compensatory mechanism to alleviate protein folding stress due to turnover defects (D’Andrea et al., 2018). ClpR1-deficient fruits expressing OR displayed a phenotype of β-carotene-rich chromoplast development similar to OR overexpression lines (D’Andrea et al., 2018). Chaperone proteins such as OR and proteases such as Clp are closely linked and cooperate with each other to ensure the normal function and differentiation of chromoplasts.

Plastids are essential biosynthetic organelles. To understand the regulation of the biological processes in plastid, the in vivo reactions of metabolites have to be measured separately. The in-depth metabolite profiling has been a pivotal tool to elucidate the environmentally and developmentally dependent dynamics of metabolism. Most metabolic profilings provide an average across different cell types and all sub-cellular compartments. However, the organelles in the different cell types execute distinct metabolic programs and produce unique metabolites. Thus, considering metabolic heterogeneity, it is vital to perform metabolome analysis in organelle resolution. Non-aqueous fractionation (NAF) method has been developed to measure the sub-cellular distribution of metabolites in plant cells by density gradient and has been broadly applied (Geigenberger et al., 2011; Dietz, 2017). For example, 70 metabolites were obtained from sub cellular compartment of Arabidopsis leaves by NAF, including plastids, cytoplasm, vacuoles, mitochondria and peroxisomes (Arrivault et al., 2014) and the cold-induced sugar and amino acid dynamics in chloroplasts of leaf were explored (Nägele and Heyer, 2013; Fürtauer et al., 2016). The metabolites in cytosol, plastids, and vacuole were profiled during apple fruit development with NAF method, demonstrating the localization of sugars and organic acids in vacuole and amino acids in cytosol and the vacuole (Beshir et al., 2019). The lipoprotein particles, plastoglobuli (PGs), are present in different plastids, including chloroplast and chromoplast (Figure 2). PGs in chloroplasts function in metabolism of prenyl lipids and jasmonate. Whereas, in chromoplasts, PGs are found to be highly enriched in carotenoid esters by systerm analysis (van Wijk and Kessler, 2017). Still, the attention on plastid metabolites profiling is limited, even though sigle cell sequencing has been rising. Plastid or other organelles in sigle cell level is challenging but essential to dissect the heterogeneity in cellular populations. The transport systems in plastid envelope membrane determines the type and rate of metabolic pathways. With the advanced mutiple omics technologies, the corresponding proteins and the associated metabolites are expected to be elucidated, which will facilitate our understanding of the metabolic networks in plastid and develop strategies for carotenoid biofortification in crops.

The current regulatory mechanisms of carotenoid metabolism include transcription of carotenoid biosynthetic and catabolic genes, translation and activity of the corresponding enzymes, and plastids development for storage. All three aspects are fine coordinated by both developmental signals and environmental stimuli. For example, the transition from etioplasts to chloroplasts during photomorphogenesis is concomitant with carotenoid accumulation to protect the photosynthetic apparatus against photodamage caused by light stress (Gommers and Monte, 2018). Chromoplast with specialized carotenoid-sequestering structures is the most efficient plastid in carotenoid production and storage. The characteristic orange and red colors in ripe tomato and many other fleshy fruits result from the chloroplast-to-chromoplast transition concomitant with chlorophyll degradation and the surge of carotenoids, mainly lycopene and β-carotene. At the transcriptomic level, nuclear genes encoding carotenoid biosynthetic enzymes are up-regulated, whereas those encoding photosynthesis related proteins are down-regulated (Sadali et al., 2019). Still, the fact that what came first: the plastid type is transformed for carotenoids or the carotenoids trigger the plastid transition, is a conundrum. In either case, the effective and timely communication between plastid and nucleus is essential and is governed by different signaling (Moreno et al., 2021). The coordinated action of the nucleus and plastid is ensured by two types of signals: anterograde signals from the nucleus to the plastids, and retrograde signals from plastids to nucleus (Jiang and Dehesh, 2021). The key components of anterograde signaling pathways in carotenoid metabolism in particular is better established than the retrograde signals. This section mainly focuses on the coordination of plastid retrograde signaling and carotenoid metabolism.

Chloroplasts, the hub of all carbon sources, is also a sensor in perceiving developmental signals and environmental stresses. Chloroplast signals harmonize gene expression at transcription and posttranscriptional levels in the nucleo-cytoplasmic compartment. The signaling molecules in response to real-time disruptions and metabolic status in plastid will be transported out to be sensed and transducted in cytosol and nucleus. However, the mechanism by which plastid connect with the nucleus through the cytosol is still not clear. Insights into the plastid-to-nucleus signaling have come from the application of two photobleaching agents, norflurazon (NF, an inhibitor of the carotenoid biosynthesis enzyme phytoene desaturase) and lincomycin (Linc, plastid translation inhibitor). Both NF and Linc treantments repress expression of photosynthesis-associated nuclear genes (PhANGs), such as light-harvesting Chla/β-binding protein (LHCB) (Cottage et al., 2008; Zhao et al., 2018). A set of genomes uncoupled (gun) mutants was genetic screened through the rescue of LHCB expression after NF treatment (Susek et al., 1993; Mochizuki et al., 2001; Larkin et al., 2003; Koussevitzky et al., 2007; Woodson et al., 2011). Mutant lines gun 1 to 6 affected tetrapyrrole metabolism. Particularly, GUN2 to GUN6 encode enzymes in the tetrapyrrole biosynthesis or metabolism and GUN1 encodes a chloroplast protein containing a pentatricopeptide repeat (PPR) protein with a small MutS-related domain, which can bind tetrapyrroles and regulate the flow through the tetrapyrrole biosynthesis pathway (Woodson et al., 2011; Zhao et al., 2018; Shimizu et al., 2019). The adapted nuclear gene expression requires transcriptional factors (TF) downstream of plastid signals. Abscisic acid insensitive 4 (ABI4), the “master switch” of ABA, is a nuclear APETALA 2 (AP-2)-type TF and controls the expression of a large number of genes (Finkelstein et al., 1998). Elongated hypocotyl 5 (HY5), one of the potent TFs involved in light response, is a bZIP transcription factor that promotes de-etiolation and chloroplast development. Golden2-like (GLK) synchronize the expression of a suite of chloroplast genes and PhANGs including chlorophyll biosynthesis, light harvesting, and carbon fixation genes, contributing to retrograde signal response (Waters et al., 2009). Chloroplast outer membrane-bound plant TF named phd transcription factor with transmembrane domains 1 (PTM1) mediates chloroplast signals, regulating the expression of PhANGs. Besides, an increasing number of signaling molecules have been identified to be involved in plastid retrograde signaling transduction, including (1) tetrapyrrole biosynthetic pathway, such as MgProto and heme (Woodson et al., 2011), (2) reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the plastids (Apel and Hirt, 2004), (3) methylerythritol cyclodiphosphate (MEcPP) (Xiao et al., 2012), (4) SAL1-3-phosphoadenosine 5-phosphate (PAP) (Zhao et al., 2019), and (5) apocarotenoids (Figure 2).

Carotenoid compositions and concentrations are adjusted in accordance with plant developmental stages and environmental changes. In chloroplast, carotenoids are integral to the light-harvesting apparatus and serve as structural components of photosystems. In contrast to chloroplast, less is studied about the retrograde signals during the differentiation of chromoplast. Massive reprogramming of the nuclear transcriptome during chloroplast-to-chromoplast transition in tomato have been revealed. The transition is achieved by the coordinated assembly of nucleus- and plastid-encoded proteins, as well as the simultaneous incorporation of pigments (chlorophylls and carotenoids). Thus, compared to the ‘green’ signaling molecules, there is a possibility that carotenoids and/or their degradation products also serve as plastidial retrograde communication metabolite. Carotenoid degradation by CCDs produces apocarotenoids. The ζ-carotene desaturase (zds/clb5) exhibits stunted growth and albino seedling phenotypes due to an apocarotenoid signal that alters PhANG expression (Avendaño-Vázquez et al., 2014). The plastidial development perturbation in the carotenoid biosynthesis mutant, carotenoid chloroplast regulation 2 (ccr2) indicating the existence of a unique apocarotenoid retrograde signal that functions through PIF3, HY5 and photomorphogenesis repressor deetiolated1 (DET1) (Cazzonelli et al., 2020). β-Cyclocitral, an apocarotenoid produced by oxidative cleavage in chloroplasts, was identified as a protective retrograde metabolite in response to excess illumination via the TGAII/Scarecrow-like protein 14 (SCL14) transcription factor (D’Alessandro et al., 2018). The molecular action of β-cyclocitral was initially reported to induce salicylic acid (SA) and subsequent transcriptional activation of gluthathione-S-transferase 5 (GST5) and GST13 (Lv et al., 2015). The other mode of β-cyclocitral action is via the induction of PAP accumulation and trigger PAP-mediated retrograde signaling in response to disturbed photosynthetic process. The transcriptome analysis of β-cyclocitral-treated plants revealed a reprogramming in the expression of genes associated with higher photosystem II photochemical efficiency and lower lipid peroxidation (Ramel et al., 2012). In addition, overexpression of a bacterial phytoene synthase gene (crtB) caused reduced chloroplast photosynthetic competence, excessive metabolic flux into carotenoid biosynthesis, and induced the transition from chloroplasts to chromoplasts in various tissues of different plant species (Llorente et al., 2020) (Figure 2). This demonstrates a retrograde signal emitted from carotenoid-accumulating plastids to facilitate chromoplast formation.

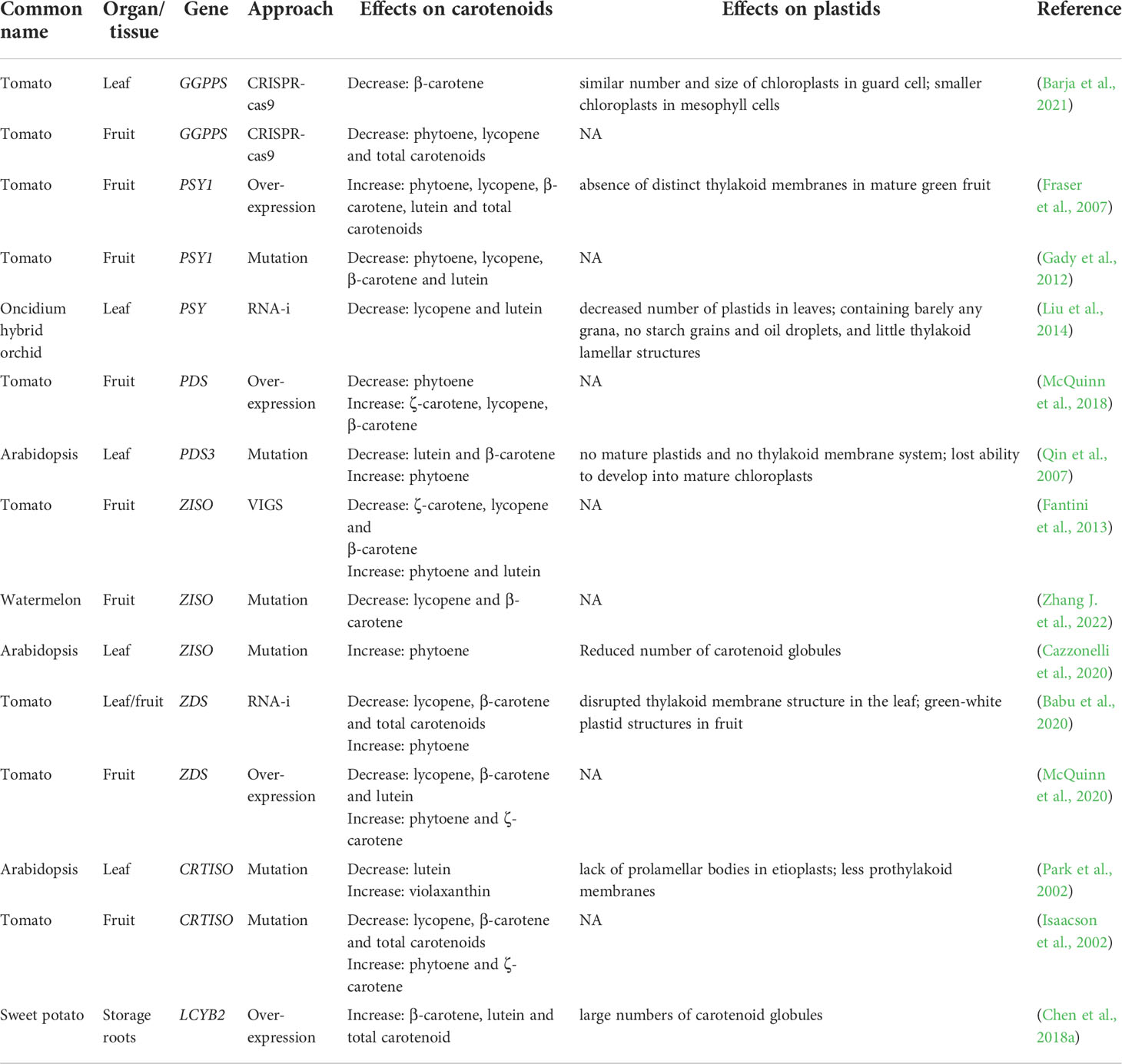

Modification of structural genes and regulators can affect their expression and cause the accumulation of specific carotenoids in plants (Kilambi et al., 2013). For example, the altered content of carotenoid compositions making the yellow, tangerine, orange, and orange-red tomato fruits (Galpaz et al., 2008). The changes of the predominant carotenoids in the disturbed lines are shown in Table 2. The general pattern is that silencing of metabolic genes leads to increased accumulation of upstream substrates and decreased levels of downstream products by feedback and feedforward regulation. In tomato, phytoene and lycopene were decreased in GGPPS knock-out mutants (Barja et al., 2021). The levels of the predominant carotenoids were elevated in PSY1 overexpressed tomato fruits and significantly decreased in PSY1 RNA-i mutant (Aluru et al., 2006; Fraser et al., 2007). PDS-silenced fruits displayed reduced levels of total carotenoids, with phytoene and phytofluene being the most abundant compounds, whereas ZDS-silenced fruits, contained abundant ζ-carotene and traces of neurosporene. However, not all downstream carotenoid composition levels will be reduced by the enzyme gene shut down; some will result in increased lutein and β-carotene contents. ZISO silencing resulted in a significant decrease in lycopene and a compensatory increase of phytoene, phytofluene, and ζ-carotene, while downstream compounds, such as lutein, were increased. We are aware of the consequences of carotenoid metabolism disorders and understand that plastids are linked to carotenoid metabolism (Sun et al., 2018; Sun et al., 2022).

Table 2 Effects of different carotenoid biosynthetic genes on carotenoid composition and content as well as plastid morphology.

Since plastids are organelles for carotenoid biosynthesis and storage, the levels of diverse carotenoid compositions can also in turn alter plastids development (Sun et al., 2018). When carotenoid metabolic pathways are disrupted, not only the development of carotenoid storage structures in the plastid is affected, but also the function of the plastid as well as the developmental processes are affected (Table 2). Modification of key enzyme genes for carotenoid metabolism causes changes in plastid microstructure. It was found that overexpression of the LCYB2 in potato resulted in an increase in lutein and β-carotene content, as well as an increase in the number of plastid globules (Chen S. et al., 2018; Diretto et al., 2020). Second, the function of plastids is also affected by changes in key enzyme genes. The thylakoid membrane structure was found to be disrupted in the leaf tissues of ZDS RNAi plants exposed to sunlight (Babu et al., 2020). The PSY RNAi-transgenic orchids exhibit a disappearance of the thylakoid lamellar structure (Liu et al., 2014). Mutation of key enzyme genes for carotenoid metabolism also caused stagnation of plastid development and loss of functional structures. One of the more intensively studied is that mutation of CRTISO leads to the disappearance of prolamellar body in the etioplast and the plant cannot synthesize chlorophyll normally for photosynthesis (Park et al., 2002). There is no doubt that carotenoid metabolites influence the substructure, function, and developmental processes of plastids. The mechanism by which metabolites themselves influence plastids remains largely unknown.

Integrating information from multiple omics, such as genomics, transcriptomics, epigenomics, proteomics, metabolics, phenomics, next-generation sequencing, and advanced bioinformatics, as a systems biology approach may enable better understanding of metabolic regulatory networks and key components in carotenoid metabolism. Therefore, the plastid “omic” response to the developmental and environmental signals should be further explored. Chromoplast is critically important for carotenoid accumulation in many agricultural plants. In comparison with the understanding of chloroplast retrograde regulatory mechanisms, less is known about its retrograde signaling pathway. Therefore, new strategies for carotenoid biofortification may be developed for human nutrition and health by gain more regulatory components involved in chromoplast biogenesis. Finally, we believe that, the comprehensive utilization of omics methods will help us further reveal the internal regulation of carotenoid accumulation in plastid and benefit biology researchers and breeders in low-cost, scalable, safe, and environmentally friendly molecular farming.

LL, QW, and YL conceived the idea of the review and prepared the initial outline and the first draft. YL, YJ, YM, and LL gathered the literature and contributed to writing the different sections. FM, ZS, TW, JZ, and QW critically revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Key Program, No. 31830078; No. 32002024) and Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (No. LY22C150001).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Aguirre-Dugua, X., Castellanos-Morales, G., Paredes-Torres, L. M., Hernandez-Rosales, H. S., Barrera-Redondo, J., Sanchez-de la Vega, G., et al. (2019). Evolutionary dynamics of transferred sequences between organellar genomes in cucurbita. J. Mol. Evol. 87, 327–342. doi: 10.1007/s00239-019-09916-1

Aluru, M. R., Yu, F., Fu, A., Rodermel, S. (2006). Arabidopsis variegation mutants: New insights into chloroplast biogenesis. J. Exp. Bot. 57, 1871–1881. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erj008

Apel, K., Hirt, H. (2004). Reactive oxygen species: metabolism, oxidative stress, and signal transduction. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 55, 373–399. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.55.031903.141701

Arrivault, S., Guenther, M., Florian, A., Encke, B., Feil, R., Vosloh, D., et al. (2014). Dissecting the subcellular compartmentation of proteins and metabolites in arabidopsis leaves using non-aqueous fractionation*. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 13, 2246–2259. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M114.038190

Asaf, S., Khan, A. L., Khan, A. R., Waqas, M., Kang, S.-M., Khan, M. A., et al. (2016). Complete chloroplast genome of nicotiana otophora and its comparison with related species. Front. Plant Sci. 7, 843. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00843

Avendaño-Vázquez, A. O., Cordoba, E., Llamas, E., San Román, C., Nisar, N., de la Torre, S., et al. (2014). An uncharacterized apocarotenoid-derived signal generated in ζ-carotene desaturase mutants regulates leaf development and the expression of chloroplast and nuclear genes in arabidopsis. Plant Cell 26, 2524–2537. doi: 10.1105/tpc.114.123349

Babu, M. A., Srinivasan, R., Subramanian, P., Kodiveri Muthukaliannan, G. (2020). RNAi silenced ζ-carotene desaturase developed variegated tomato transformants with increased phytoene content. Plant Growth Regul. 93, 189–201. doi: 10.1007/s10725-020-00678-1

Bai, D., Luo, X., Yang, Y. (2021). Complete chloroplast genome sequence of ‘Field muskmelon,’ an invasive weed to China. Mitochondrial DNA B Resour. 6, 3352–3353. doi: 10.1080/23802359.2021.1994888

Barja, M. V., Ezquerro, M., Beretta, S., Diretto, G., Florez-Sarasa, I., Feixes, E., et al. (2021). Several geranylgeranyl diphosphate synthase isoforms supply metabolic substrates for carotenoid biosynthesis in tomato. New Phytol. 231, 255–272. doi: 10.1111/nph.17283

Barkan, A. (2011). Expression of plastid genes: organelle-specific elaborations on a prokaryotic scaffold. Plant Physiol. 155, 1520–1532. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.171231

Barsan, C., Sanchez-Bel, P., Rombaldi, C., Egea, I., Rossignol, M., Kuntz, M., et al. (2010). Characteristics of the tomato chromoplast revealed by proteomic analysis. J. Exp. Bot. 61, 2413–2431. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erq070

Barsan, C., Zouine, M., Maza, E., Bian, W., Egea, I., Rossignol, M., et al. (2012). Proteomic analysis of chloroplast-to-chromoplast transition in tomato reveals metabolic shifts coupled with disrupted thylakoid biogenesis machinery and elevated energy-production components. Plant Physiol. 160, 708–725. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.203679

Bausher, M. G., Singh, N. D., Lee, S. B., Jansen, R. K., Daniell, H. (2006). The complete chloroplast genome sequence of citrus sinensis (L.) osbeck var ‘Ridge pineapple’: Organization and phylogenetic relationships to other angiosperms. BMC Plant Biol. 6, 21.doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-6-21

Beck, C. F. (2005). Signaling pathways from the chloroplast to the nucleus. Planta 222, 743–756. doi: 10.1007/s00425-005-0021-2

Beshir, W. F., Tohge, T., Watanabe, M., Hertog, M. L., Hoefgen, R., Fernie, A. R., et al. (2019). Non-aqueous fractionation revealed changing subcellular metabolite distribution during apple fruit development. Horticult. Res. 6, 98. doi: 10.1038/s41438-019-0178-7

Bharadwaj, R. K. B., Kumar, S. R., Sathishkumar, R. (2019). “Green biotechnology: A brief update on plastid genome engineering,” in Advances in plant transgenics: Methods and applications, eds. Sathishkumar, R., Kumar, S., Hema, J., Baskar, V. (Springer, Singapore) 79–100. doi: 10.1007/978-981-13-9624-3_4

Bock, R. (2022). Transplastomic approaches for metabolic engineering. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 66, 102185. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2022.102185

Bonk, M., Hoffmann, B., Von Lintig, J., Schledz, M., Al-Babili, S., Hobeika, E., et al. (1997). Chloroplast import of four carotenoid biosynthetic enzymes in vitro reveals differential fates prior to membrane binding and oligomeric assembly. Eur. J. Biochem. 247, 942–950. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00942.x

Bonk, M., Tadros, M., Vandekerckhove, J., Al-Babili, S., Beyer, P. (1996). Purification and characterization of chaperonin 60 and heat-shock protein 70 from chromoplasts of narcissus pseudonarcissus. Plant Physiol. 111, 931–939. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.3.931

Bouchnak, I., van Wijk, K. J. (2021). Structure, function, and substrates of clp AAA+ protease systems in cyanobacteria, plastids, and apicoplasts: A comparative analysis. J. Biol. Chem. 296, 100338. doi: 10.1016/j.jbc.2021.100338

Bruley, C., Dupierris, V., Salvi, D., Rolland, N., Ferro, M. (2012). AT_CHLORO: A chloroplast protein database dedicated to sub-plastidial localization. Front. Plant Sci. 3. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2012.00205

Cazzonelli, C. I., Hou, X., Alagoz, Y., Rivers, J., Dhami, N., Lee, J., et al. (2020). A cis-carotene derived apocarotenoid regulates etioplast and chloroplast development. Elife 9, e45310. doi: 10.7554/eLife.45310

Chayut, N., Yuan, H., Ohali, S., Meir, A., Sa’ar, U., Tzuri, G., et al. (2017). Distinct mechanisms of the ORANGE protein in controlling carotenoid flux. Plant Physiol. 173, 376–389. doi: 10.1104/pp.16.01256

Chayut, N., Yuan, H., Saar, Y., Zheng, Y., Sun, T., Zhou, X., et al. (2021). Comparative transcriptome analyses shed light on carotenoid production and plastid development in melon fruit. Hortic. Res. 8, 112. doi: 10.1038/s41438-021-00547-6

Chen, Y. L., Chen, L. J., Chu, C. C., Huang, P. K., Wen, J. R., Li, H. M. (2018). TIC236 links the outer and inner membrane translocons of the chloroplast. Nature 564, 125–129. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0713-y

Chen, K., Li, G. J., Bressan, R. A., Song, C. P., Zhu, J. K., Zhao, Y. (2020). Abscisic acid dynamics, signaling, and functions in plants. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 62, 25–54. doi: 10.1111/jipb.12899

Chen, Q., Shen, P., Bock, R., Li, S., Zhang, J. (2022). Comprehensive analysis of plastid gene expression during fruit development and ripening of kiwifruit. Plant Cell Rep. 41, 1103–1114. doi: 10.1007/s00299-022-02840-7

Chen, S., Xu, Z., Zhao, Y., Zhong, X., Li, C., Yang, G. (2018). Structural characteristic and phylogenetic analysis of the complete chloroplast genome of dianthus caryophyllus. Mitochondrial DNA B Resour. 3, 1131–1132. doi: 10.1080/23802359.2018.1521313

Choi, H., Yi, T., Ha, S. H. (2021). Diversity of plastid types and their interconversions. Front. Plant Sci. 12, 692024. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.692024

Cho, M.-S., Yoon, H. S., Kim, S.-C. (2018). Complete chloroplast genome of cultivated flowering cherry, prunus ×yedoensis ‘Somei-yoshino’ in comparison with wild prunus yedoensis matsum. (Rosaceae). Mol. Breed. 38, 112.

Chung, H. J., Jung, J. D., Park, H. W., Kim, J. H., Cha, H. W., Min, S. R., et al. (2006). The complete chloroplast genome sequences of solanum tuberosum and comparative analysis with solanaceae species identified the presence of a 241-bp deletion in cultivated potato chloroplast DNA sequence. Plant Cell Rep. 25, 1369–1379. doi: 10.1007/s00299-006-0196-4

Cottage, A. J., Mott, E. K., Wang, J.-H., Sullivan, J. A., MacLean, D., Tran, L., et al. (2008). GUN1 (GENOMES UNCOUPLED1) encodes a pentatricopeptide repeat (PPR) protein involved in plastid protein synthesis-responsive retrograde signaling to the nucleus. paper presented at: Photosynthesis energy from the sun (Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands).

D’Alessandro, S., Ksas, B., Havaux, M. (2018). Decoding β-Cyclocitral-Mediated retrograde signaling reveals the role of a detoxification response in plant tolerance to photooxidative stress. Plant Cell 30, 2495–2511. doi: 10.1105/tpc.18.00578

D’Andrea, L., Simon-Moya, M., Llorente, B., Llamas, E., Marro, M., Loza-Alvarez, P., et al. (2018). Interference with clp protease impairs carotenoid accumulation during tomato fruit ripening. J. Exp. Bot. 69, 1557–1568. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erx491

Daniell, H., Lee, S. B., Grevich, J., Saski, C., Quesada-Vargas, T., Guda, C., et al. (2006). Complete chloroplast genome sequences of solanum bulbocastanum, solanum lycopersicum and comparative analyses with other solanaceae genomes. Theor. Appl. Genet. 112, 1503–1518. doi: 10.1007/s00122-006-0254-x

Dietz, K.-J. (2017). Subcellular metabolomics: the choice of method depends on the aim of the study. J. Exp. Bot. 68, 5695–5698. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erx406

Ding, Q.-X., Liu, J., Gao, L.-Z. (2016). The complete chloroplast genome of eggplant (Solanum melongena l.). Mitochondrial DNA Part B Resour. 1, 843–844. doi: 10.1080/23802359.2016.1186510

Diretto, G., Frusciante, S., Fabbri, C., Schauer, N., Busta, L., Wang, Z., et al. (2020). Manipulation of β-carotene levels in tomato fruits results in increased ABA content and extended shelf life. Plant Biotechnol J. 18, 1185–1199. doi: 10.1111/pbi.13283

Dong, T., Park, Y., Hwang, I. (2015). Abscisic acid: biosynthesis, inactivation, homoeostasis and signalling. Essays Biochem. 58, 29–48. doi: 10.1042/bse0580029

Egea, I., Barsan, C., Bian, W., Purgatto, E., Latche, A., Chervin, C., et al. (2010). Chromoplast differentiation: Current status and perspectives. Plant Cell Physiol. 51, 1601–1611. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcq136

Facchinelli, F., Weber, A. P. M. (2011). The metabolite transporters of the plastid envelope: an update. Front. Plant Sci. 2. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2011.00050

Fajardo, D., Senalik, D., Ames, M., Zhu, H., Steffan, S. A., Harbut, R., et al. (2012). Complete plastid genome sequence of vaccinium macrocarpon: structure, gene content, and rearrangements revealed by next generation sequencing. Tree Genet. Genomes 9, 489–498. doi: 10.1007/s11295-012-0573-9

Fantini, E., Falcone, G., Frusciante, S., Giliberto, L., Giuliano, G. (2013). Dissection of tomato lycopene biosynthesis through virus-induced gene silencing. Plant Physiol. 163, 986–998. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.224733

Finkelstein, R. R., Wang, M. L., Lynch, T. J., Rao, S., Goodman, H. M. (1998). The arabidopsis abscisic acid response locus ABI4 encodes an APETALA 2 domain protein. Plant Cell 10, 1043–1054. doi: 10.1105/tpc.10.6.1043

Fish, M., Nash, D., German, A., Overton, A., Jelokhani-Niaraki, M., Chuong, S. D. X., et al. (2022). New insights into the chloroplast outer membrane proteome and associated targeting pathways. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 1571. doi: 10.3390/ijms23031571

Fraser, P. D., Enfissi, E. M., Halket, J. M., Truesdale, M. R., Yu, D., Gerrish, C., et al. (2007). Manipulation of phytoene levels in tomato fruit: effects on isoprenoids, plastids, and intermediary metabolism. Plant Cell 19, 3194–3211. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.049817

Fürtauer, L., Weckwerth, W., Nägele, T. (2016). A benchtop fractionation procedure for subcellular analysis of the plant metabolome. Front. Plant Sci. 7, 1912. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01912

Gady, A. L., Vriezen, W. H., Van de Wal, M. H., Huang, P., Bovy, A. G., Visser, R. G., et al. (2012). Induced point mutations in the phytoene synthase 1 gene cause differences in carotenoid content during tomato fruit ripening. Mol. Breeding: New Strategies Plant Improvement 29, 801–812. doi: 10.1007/s11032-011-9591-9

Galpaz, N., Wang, Q., Menda, N., Zamir, D., Hirschberg, J. (2008). Abscisic acid deficiency in the tomato mutant high-pigment 3 leading to increased plastid number and higher fruit lycopene content. The Plant Journal 53, 717–730. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03362.x

Ganesan, I., Theg, S. M. (2019). Structural considerations of folded protein import through the chloroplast TOC/TIC translocons. FEBS Lett. 593, 565–572. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.13342

Garcia-Plazaola, J. I., Matsubara, S., Osmond, C. B. (2007). Review: The lutein epoxide cycle in higher plants: its relationships to other xanthophyll cycles and possible functions. Funct. Plant Biol. 34, 759–773. doi: 10.1071/FP07095

Geigenberger, P., Tiessen, A., Meurer, J. (2011). Use of non-aqueous fractionation and metabolomics to study chloroplast function in arabidopsis. Methods Mol. Biol. 775, 135–160. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-237-3_8

Giuliano, G. (2017). Provitamin a biofortification of crop plants: a gold rush with many miners. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 44, 169–180. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2017.02.001

Gommers, C. M. M., Monte, E. (2018). Seedling establishment: A dimmer switch-regulated process between dark and light signaling. Plant Physiol. 176, 1061–1074. doi: 10.1104/pp.17.01460

Goremykin, V. V., Hirsch-Ernst, K. I., Wölfl, S., Hellwig, F. H. (2004). The chloroplast genome of nymphaea alba: whole-genome analyses and the problem of identifying the most basal angiosperm. Mol. Biol. Evol. 21, 1445–1454. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msh147

Govindarajulu, R., Parks, M., Tennessen, J. A., Liston, A., Ashman, T. L. (2015). Comparison of nuclear, plastid, and mitochondrial phylogenies and the origin of wild octoploid strawberry species. Am. J. Bot. 102, 544–554. doi: 10.3732/ajb.1500026

Hasunuma, T., Miyazawa, S.-I., Yoshimura, S., Shinzaki, Y., Tomizawa, K.-I., Shindo, K., et al. (2008). Biosynthesis of astaxanthin in tobacco leaves by transplastomic engineering. The Plant Journal 55, 857–868. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03559.x

He, X., Jiao, Y., Shen, Y., Zhang, T. (2022). The complete chloroplast genome of medicago scutellata (Fabaceae). Mitochondrial DNA B Resour. 7, 379–381. doi: 10.1080/23802359.2022.2039083

Hoang, N. V., Furtado, A., McQualter, R. B., Henry, R. J. (2015). Next generation sequencing of total DNA from sugarcane provides no evidence for chloroplast heteroplasmy. New Negatives Plant Sci. 1-2, 33–45. doi: 10.1016/j.neps.2015.10.001

Hörmann, F., Soll, J., Bölter, B. (2007). The chloroplast protein import machinery: A review. Methods in molecular biology (Clifton, N.J.) 390, 179–193. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-466-7_12

Huang, Y. Y., Matzke, A. J., Matzke, M. (2013). Complete sequence and comparative analysis of the chloroplast genome of coconut palm (Cocos nucifera). PloS One 8, e74736. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074736

Huang, X., Ni, Z., Shi, T., Tao, R., Yang, Q., Luo, C., et al. (2022). Novel insights into the dissemination route of Japanese apricot (Prunus mume sieb. et zucc.) based on genomics. Plant J. 110, 1182–1197. doi: 10.1111/tpj.15731

Isaacson, T., Ronen, G., Zamir, D., Hirschberg, J. (2002). Cloning of tangerine from tomato reveals a carotenoid isomerase essential for the production of beta-carotene and xanthophylls in plants. Plant Cell 14, 333–342. doi: 10.1105/tpc.010303

Jansen, R. K., Kaittanis, C., Saski, C., Lee, S. B., Tomkins, J., Alverson, A. J., et al. (2006). Phylogenetic analyses of vitis (Vitaceae) based on complete chloroplast genome sequences: effects of taxon sampling and phylogenetic methods on resolving relationships among rosids. BMC Evol. Biol. 6, 32. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-6-32

Jansen, R. K., Saski, C., Lee, S. B., Hansen, A. K., Daniell, H. (2011). Complete plastid genome sequences of three rosids (Castanea, prunus, theobroma): evidence for at least two independent transfers of rpl22 to the nucleus. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28, 835–847. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msq261

Jia, K. P., Mi, J., Ali, S., Ohyanagi, H., Moreno, J. C., Ablazov, A., et al. (2022). An alternative, zeaxanthin epoxidase-independent abscisic acid biosynthetic pathway in plants. Mol. Plant 15, 151–166. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2021.09.008

Jiang, J., Dehesh, K. (2021). Plastidial retrograde modulation of light and hormonal signaling: an odyssey. New Phytol. 230, 931–937. doi: 10.1111/nph.17192

Jian, H. Y., Zhang, Y. H., Yan, H. J., Qiu, X. Q., Wang, Q. G., Li, S. B., et al. (2018). The complete chloroplast genome of a key ancestor of modern roses, Rosa chinensis var. spontanea, and a comparison with congeneric species. Molecules 23, 389. doi: 10.3390/molecules23020389

Johnson, G. N., Stepien, P. (2016). Plastid terminal oxidase as a route to improving plant stress tolerance: Known knowns and known unknowns. Plant Cell Physiol. 57, 1387–1396. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcw042

Jo, Y. D., Park, J., Kim, J., Song, W., Hur, C. G., Lee, Y. H., et al. (2011). Complete sequencing and comparative analyses of the pepper (Capsicum annuum l.) plastome revealed high frequency of tandem repeats and large insertion/deletions on pepper plastome. Plant Cell Rep. 30, 217–229. doi: 10.1007/s00299-010-0929-2

Joyard, J., Ferro, M., Masselon, C., Seigneurin-Berny, D., Salvi, D., Garin, J., et al. (2009). Chloroplast proteomics and the compartmentation of plastidial isoprenoid biosynthetic pathways. Mol. Plant 2, 1154–1180. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssp088

Kahlau, S., Bock, R. (2008). Plastid transcriptomics and translatomics of tomato fruit development and chloroplast-to-chromoplast differentiation: chromoplast gene expression largely serves the production of a single protein. Plant Cell 20, 856–874. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.055202

Kessler, F., Schnell, D. J. (2006). The function and diversity of plastid protein import pathways: A multilane GTPase highway into plastids. Traffic 7, 248–257. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2005.00382.x

Kilambi, H. V., Kumar, R., Sharma, R., Sreelakshmi, Y. (2013). Chromoplast-specific carotenoid-associated protein appears to be important for enhanced accumulation of carotenoids in hp1 tomato fruits. Plant Physiol. 161, 2085–2101. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.212191

Kim, J. S., Jung, J. D., Lee, J. A., Park, H. W., Oh, K. H., Jeong, W. J., et al. (2006). Complete sequence and organization of the cucumber (Cucumis sativus l. cv. baekmibaekdadagi) chloroplast genome. Plant Cell Rep. 25, 334–340. doi: 10.1007/s00299-005-0097-y

Kim, I., Kim, H. U. (2022). The mysterious role of fibrillin in plastid metabolism: current advances in understanding. journal of. Exp. Bot. 73, 2751–2764. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erac087

Kim, J. H., Lee, S. I., Kim, B. R., Choi, I. Y., Ryser, P., Kim, N. S. (2017). Chloroplast genomes of Lilium lancifolium, L. amabile, L. callosum and L. philadelphicum: Molecular characterization and their use in phylogenetic analysis in the genus lilium and other allied genera in the order liliales. PloS One 12, e0186788. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0186788

Klasek, L., Inoue, K. (2016). Dual Protein Localization to the Envelope and Thylakoid Membranes Within the Chloroplast. International review of cell and molecular biology. Cambridge, MA: Elsevier. Acadamic Press. 323, 231–263. doi: 10.1016/bs.ircmb.2015.12.008

Kmiec, B., Teixeira, P. F., Glaser, E. (2014). Shredding the signal: targeting peptide degradation in mitochondria and chloroplasts. Trends Plant Sci. 19, 771–778. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2014.09.004

Koussevitzky, S., Nott, A., Mockler, T. C., Hong, F., Sachetto-Martins, G., Surpin, M., et al. (2007). Signals from chloroplasts converge to regulate nuclear gene expression. Science 316, 715–719. doi: 10.1126/science.1140516

Ku, C., Chung, W.-C., Chen, L.-L., Kuo, C.-H. (2013). The complete plastid genome sequence of Madagascar periwinkle catharanthus roseus (L.) g. don: Plastid genome evolution, molecular marker identification, and phylogenetic implications in asterids. PloS One 8, e68518. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068518

Larkin, R. M., Alonso, J. M., Ecker, J. R., Chory, J. (2003). GUN4, a regulator of chlorophyll synthesis and intracellular signaling. Science 299, 902–906. doi: 10.1126/science.1079978

Lee, H. L., Jansen, R. K., Chumley, T. W., Kim, K. J. (2007). Gene relocations within chloroplast genomes of jasminum and menodora (Oleaceae) are due to multiple, overlapping inversions. Mol. Biol. Evol. 24, 1161–1180. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm036

Lelivelt, C., McCabe, M. S., Newell, C. A., deSnoo, C. B., van Dun, K., Birch-Machin, I., et al (2005). Stable plastid transformation in lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.). Plant molecular biology 58 (6), 763–774. doi: 10.1007/s11103-005-7704-8

Li, H., Guo, Q., Zheng, W. (2016). The complete chloroplast genome of cupressus gigantea, an endemic conifer species to qinghai-Tibetan plateau. Mitochondrial DNA A DNA Mapp. Seq. Anal. 27, 3743–3744.

Lin, W., Dai, S., Chen, Y., Zhou, Y., Liu, X. (2019). The complete chloroplast genome sequence of moringa oleifera lam. (Moringaceae). Mitochondrial DNA B Resour. 4, 4094–4095. doi: 10.1080/23802359.2019.1627922

Ling, Q., Broad, W., Trosch, R., Topel, M., Demiral Sert, T., Lymperopoulos, P., et al. (2019). Ubiquitin-dependent chloroplast-associated protein degradation in plants. Science 363(6429), eaav4467. doi: 10.1126/science.aav4467

Ling, Q., Sadali, N. M., Soufi, Z., Zhou, Y., Huang, B., Zeng, Y., et al. (2021). The chloroplast-associated protein degradation pathway controls chromoplast development and fruit ripening in tomato. Nat. Plants 7, 655–666. doi: 10.1038/s41477-021-00916-y

Liu, J. X., Chiou, C. Y., Shen, C. H., Chen, P. J., Liu, Y. C., Jian, C. D., et al. (2014). RNA Interference-based gene silencing of phytoene synthase impairs growth, carotenoids, and plastid phenotype in oncidium hybrid orchid. SpringerPlus 3, 478. doi: 10.1186/2193-1801-3-478

Liu, B. B., Liu, G. N., Hong, D. Y., Wen, J. (2019). Eriobotrya belongs to rhaphiolepis (Maleae, rosaceae): Evidence from chloroplast genome and nuclear ribosomal DNA data. Front. Plant Sci. 10, 1731. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2019.01731

Liu, L. X., Li, R., Worth, J. R. P., Li, X., Li, P., Cameron, K. M., et al. (2017). The complete chloroplast genome of Chinese bayberry (Morella rubra, myricaceae): Implications for understanding the evolution of fagales. Front. Plant Sci. 8, 968. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00968

Liu, J., Niu, Y. F., Liu, S. H., Ni, S. B. (2016). The complete pineapple (Ananas comosus; bromeliaceae) varieties F153 chloroplast genome sequence. Mitochondrial DNA B Resour. 1, 390–391. doi: 10.1080/23802359.2016.1174084

Liu, M. X., Tao, X. L., Zhu, H. X., Hou, D. (2020). The complete chloroplast genome sequence of red asparagus lettuce (Lactuca sativa var. asparagine l. red) (Asteraceae), endemic to China. Mitochondrial DNA B Resour. 5, 3013–3014. doi: 10.1080/23802359.2020.1778553

Li, L., Yuan, H., Zeng, Y., Xu, Q. (2016a). Plastids and carotenoid accumulation. Subcell Biochem. 79, 273–293. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-39126-7_10

Li, L., Yuan, H., Zeng, Y., Xu, Q. (2016b). “Plastids and carotenoid accumulation,” in Carotenoids in nature: Biosynthesis, regulation and function. Ed. Carotenoids in Nature. Cham: Springer. 273–293. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-39126-7_10

Llorente, B., Martinez-Garcia, J. F., Stange, C., Rodriguez-Concepcion, M. (2017). Illuminating colors: regulation of carotenoid biosynthesis and accumulation by light. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 37, 49–55. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2017.03.011

Llorente, B., Torres-Montilla, S., Morelli, L., Florez-Sarasa, I., Matus, J. T., Ezquerro, M., et al. (2020). Synthetic conversion of leaf chloroplasts into carotenoid-rich plastids reveals mechanistic basis of natural chromoplast development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 117, 21796–21803. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2004405117

Lopez, A. B., Van Eck, J., Conlin, B. J., Paolillo, D. J., O’Neill, J., Li, L. (2008). Effect of the cauliflower or transgene on carotenoid accumulation and chromoplast formation in transgenic potato tubers. J. Exp. Bot. 59, 213–223. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erm299

Lu, Y., Stegemann, S., Agrawal, S., Karcher, D., Ruf, S., Bock, R. (2017). Horizontal transfer of a synthetic metabolic pathway between plant species. Curr. Biol. 27, 3034–3041 e3033. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2017.08.044

Lu, S., Van Eck, J., Zhou, X., Lopez, A. B., O’Halloran, D. M., Cosman, K. M., et al. (2006). The cauliflower or gene encodes a DnaJ cysteine-rich domain-containing protein that mediates high levels of beta-carotene accumulation. Plant Cell 18, 3594–3605. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.046417

Lv, F., Zhou, J., Zeng, L., Xing, D. (2015). β-cyclocitral upregulates salicylic acid signalling to enhance excess light acclimation in arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot. 66, 4719–4732. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erv231

Ma, D., Huang, X., Hou, J., Ma, Y., Han, Q., Hou, G., et al. (2018). Quantitative analysis of the grain amyloplast proteome reveals differences in metabolism between two wheat cultivars at two stages of grain development. BMC Genomics 19, 768. doi: 10.1186/s12864-018-5174-z

Majeran, W., Friso, G., Asakura, Y., Qu, X., Huang, M., Ponnala, L., et al. (2012). Nucleoid-enriched proteomes in developing plastids and chloroplasts from maize leaves: a new conceptual framework for nucleoid functions. Plant Physiol. 158, 156–189. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.188474

Ma, Q., Li, S., Bi, C., Hao, Z., Sun, C., Ye, N. (2017). Complete chloroplast genome sequence of a major economic species, ziziphus jujuba (Rhamnaceae). Curr. Genet. 63, 117–129. doi: 10.1007/s00294-016-0612-4

Martin, G., Baurens, F. C., Cardi, C., Aury, J. M., D’Hont, A. (2013). The complete chloroplast genome of banana (Musa acuminata, zingiberales): Insight into plastid monocotyledon evolution. PloS One 8, e67350. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067350

McQuinn, R. P., Gapper, N. E., Gray, A. G., Zhong, S., Tohge, T., Fei, Z., et al. (2020). Manipulation of ZDS in tomato exposes carotenoid- and ABA-specific effects on fruit development and ripening. Plant Biotechnol. J. 18, 2210–2224. doi: 10.1111/pbi.13377

McQuinn, R. P., Wong, B., Giovannoni, J. J. (2018). AtPDS overexpression in tomato: exposing unique patterns of carotenoid self-regulation and an alternative strategy for the enhancement of fruit carotenoid content. Plant Biotechnol. J. 16, 482–494. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12789

Mehmood, F., Abdullah, Ubaid, Z., Shahzadi, I., Ahmed, I., Waheed, M. T., Poczai, P., et al. (2020). Plastid genomics of nicotiana (Solanaceae): Insights into molecular evolution, positive selection and the origin of the maternal genome of Aztec tobacco (Nicotiana rustica). PeerJ 8, e9552–e9552. doi: 10.7717/peerj.9552

Mergner, J., Kuster, B. (2022). Plant proteome dynamics. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 73, 67–92. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-102620-031308

Miao, X. R., Chen, Q. X., Niu, J. Q., Guo, Y. P. (2022). The complete chloroplast genome of highbush blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum). Mitochondrial DNA B Resour. 7, 87–88. doi: 10.1080/23802359.2021.2009384

Michel, E. J. S., Ponnala, L., van Wijk, K. J. (2021). Tissue-type specific accumulation of the plastoglobular proteome, transcriptional networks, and plastoglobular functions. J. Exp. Bot. 72, 4663–4679. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erab175

Mochizuki, N., Brusslan, J. A., Larkin, R., Nagatani, A., Chory, J. (2001). Arabidopsis genomes uncoupled 5 (GUN5) mutant reveals the involvement of mg-chelatase h subunit in plastid-to-nucleus signal transduction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 2053–2058. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.4.2053

Moreno, J. C. (2018). The proteOMIC era: A useful tool to gain deeper insights into plastid physiology. Theor. Exp. Plant Physiol. 31, 157–171. doi: 10.1007/s40626-018-0133-2

Moreno, J. C., Mi, J., Alagoz, Y., Al-Babili, S. (2021). Plant apocarotenoids: from retrograde signaling to interspecific communication. Plant J. 105, 351–375. doi: 10.1111/tpj.15102

Nacir, H., Brehelin, C. (2013). When proteomics reveals unsuspected roles: the plastoglobule example. Front. Plant Sci. 4, 114. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2013.00114

Nägele, T., Heyer, A. G. (2013). Approximating subcellular organisation of carbohydrate metabolism during cold acclimation in different natural accessions of arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol. 198, 777–787. doi: 10.1111/nph.12201

Palomar, V. M., Jaksich, S., Fujii, S., Kucinski, J., Wierzbicki, A. T. (2022). High-resolution map of plastid-encoded RNA polymerase binding patterns demonstrates a major role of transcription in chloroplast gene expression. Plant J. 111, 1139–1151. doi: 10.1111/tpj.15882

Park, J., Kim, Y., Kwon, W., Xi, H., Kwon, M. (2019). The complete chloroplast genome of tulip tree, liriodendron tulifipera l. (Magnoliaceae): investigation of intra-species chloroplast variations. Mitochondrial DNA B Resour. 4, 2523–2524. doi: 10.1080/23802359.2019.1598822

Park, H., Kreunen, S. S., Cuttriss, A. J., DellaPenna, D., Pogson, B. J. (2002). Identification of the carotenoid isomerase provides insight into carotenoid biosynthesis, prolamellar body formation, and photomorphogenesis. Plant Cell 14, 321–332. doi: 10.1105/tpc.010302

Pfannschmidt, T., Blanvillain, R., Merendino, L., Courtois, F., Chevalier, F., Liebers, M., et al. (2015). Plastid RNA polymerases: Orchestration of enzymes with different evolutionary origins controls chloroplast biogenesis during the plant life cycle. J. Exp. Bot. 66, 6957–6973. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erv415

Prabhudas, S. K., Raju, B., Kannan Thodi, S., Parani, M., Natarajan, P. (2016). The complete chloroplast genome sequence of Indian mustard (Brassica juncea l.). Mitochondrial DNA A DNA Mapp. Seq. Anal. 27(6), 4622–4623. doi: 10.3109/19401736.2015.1101586

Priya, R., Sneha, P., Dass, J., Doss, C, G. P., Manickavasagam, M., Siva, R. (2019). Exploring the codon patterns between CCD and NCED genes among different plant species. Computers in biology and medicine 114, 103449. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2019.103449

Qiao, J., Cai, M., Yan, G., Wang, N., Li, F., Chen, B., et al. (2016). High-throughput multiplex cpDNA resequencing clarifies the genetic diversity and genetic relationships among brassica napus, brassica rapa and brassica oleracea. Plant Biotechnol. J. 14, 409–418. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12395

Qin, G., Gu, H., Ma, L., Peng, Y., Deng, X. W., Chen, Z., et al. (2007). Disruption of phytoene desaturase gene results in albino and dwarf phenotypes in arabidopsis by impairing chlorophyll, carotenoid, and gibberellin biosynthesis. Cell Res. 17, 471–482. doi: 10.1038/cr.2007.40

Quian-Ulloa, R., Stange, C. (2021). Carotenoid biosynthesis and plastid development in plants: The role of light. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 1184. doi: 10.3390/ijms22031184

Ramel, F., Birtic, S., Ginies, C., Soubigou-Taconnat, L., Triantaphylidès, C., Havaux, M. (2012). Carotenoid oxidation products are stress signals that mediate gene responses to singlet oxygen in plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 5535–5540. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115982109

Ren, Y., Xia, H., Lu, L., Zhao, G. (2021). Characterization of the complete chloroplast genome of hordeum vulgare l. var. trifurcatum with phylogenetic analysis. Mitochondrial DNA B Resour. 6, 1852–1854. doi: 10.1080/23802359.2021.1935343

Richardson, L. G. L., Schnell, D. J. (2020). Origins, function, and regulation of the TOC-TIC general protein import machinery of plastids. J. Exp. Bot. 71, 1226–1238. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erz517