94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

REVIEW article

Front. Plant Sci., 12 November 2021

Sec. Plant Cell Biology

Volume 12 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2021.723128

Hemicellulose is entangled with cellulose through hydrogen bonds and meanwhile acts as a bridge for the deposition of lignin monomer in the secondary wall. Therefore, hemicellulose plays a vital role in the utilization of cell wall biomass. Many advances in hemicellulose research have recently been made, and a large number of genes and their functions have been identified and verified. However, due to the diversity and complexity of hemicellulose, the biosynthesis and regulatory mechanisms are yet unknown. In this review, we summarized the types of plant hemicellulose, hemicellulose-specific nucleotide sugar substrates, key transporters, and biosynthesis pathways. This review will contribute to a better understanding of substrate-level regulation of hemicellulose synthesis.

The plant cell wall, primarily composed of cellulose, hemicellulose, pectin, and lignin, serves a variety of functions, including protection, support, material transport, and information exchange (Pauly and Keegstra, 2008). The plant cell wall is composed of into three layers: the middle lamella, the primary wall, and the secondary wall (Pauly and Keegstra, 2008). Middle lamella makes first thin layer mainly rich with pectin and is formed to connect two adjacent cells. The plant subsequently produces nucleosides and their metabolites via photosynthesis and adds them to the middle lamella, forming a flexible and elastic the primary cell wall. After cell growth ceases, the cell wall thickens in the inside and accumulate cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin to form secondary cell wall.

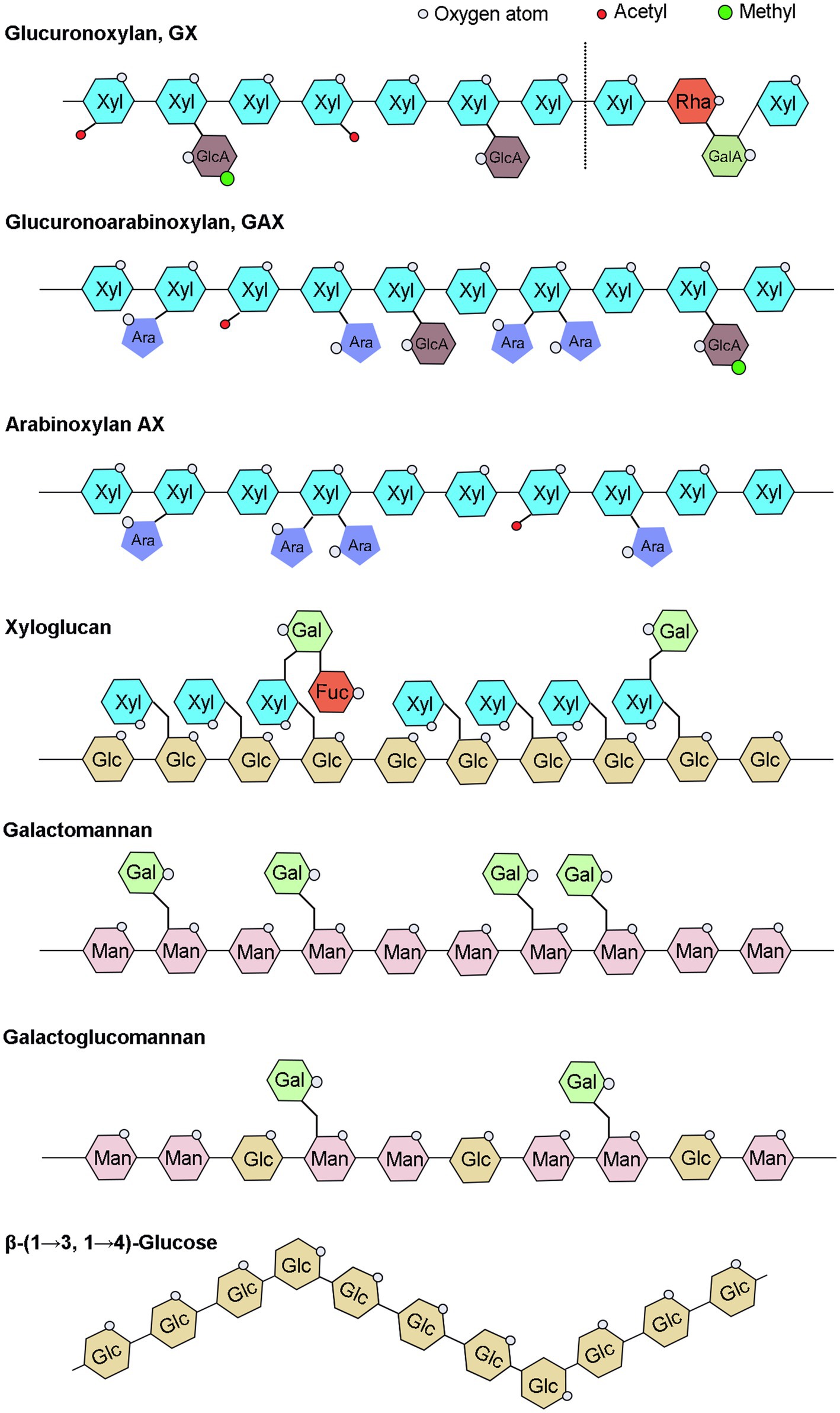

Hemicellulose, a broad term for a group of complex glycans, is a major component of plant cell walls and one of the most essential modern chemical raw materials for fuel. Hemicellulose widely used in variety of other fields, including as food additives in food industry and as plasticizer, drug delivery agent in medicinal industry (Qaseem et al., 2021). Hemicelluloses have various distinct structures, primarily xylan, xyloglucan, mannan, β-(1→3, 1 →4)-glucan, and their derivatives, and their content and detailed structure vary greatly depending on plant species and growth phases (Scheller and Ulvskov, 2010; Figure 1). Xylan is the most abundant type of hemicelluloses in broad-leaved woods, cereals, and dicotyledonous herbs. Mannan is mainly found in gymnosperms, and xyloglucan is a minor hemicellulose component of all terrestrial plants, including mosses (Scheller and Ulvskov, 2010). β-(1→3, 1→4)-glucans are less abundant in many plants than other hemicelluloses, but are abundant in grasses and have received less attention.

Figure 1. Schematic illustration of hemicelluloses. UDP-Glc, Uridine diphosphate glucose; UDP-GlcA, UDP-glucuronic acid; UDP-Xyl, UDP-xylose; UDP-Gal, UDP-galactose; UDP-GalA, UDP-galacturonic acid; UDP-Ara, UDP-arabinose; UDP-Rha, UDP-rhamnose; GDP-Man, guanosine diphosphate-mannose; and GDP-Fuc, GDP-fucose.

Hemicelluloses are a general term for heteropolysaccharides composed of two or more free monosaccharides linked in various ways, such as xylose, glucose, mannose, and galactose. Xylose is the main hemicellulose monosaccharide in grasses and hardwood, whereas arabinose, galactose, and mannose are the principal hemicellulose monosaccharides in softwood, plant seeds, endosperms, and fruits (Gibeaut et al., 2005; Schadel et al., 2010). Hemicellulose is composed of several different types of five-carbon sugars [β-D-xylose (Xyl), α-L-arabinose (Ara), α-L-rhamnose (Rha), and α-L-fucose (Fuc)], six-carbon sugars [β-D-glucose (Glu), β-D-mannose (Man), and α-D-galactose (Gal)], and glyoxalate [UDP-glucuronic acid (UDP-GlcA) and UDP-galacturonic acid (UDP-GalA)] monomers (Schadel et al., 2010).

Among them, UDP-Glc and GDP-Man work as upstream originators then are further catalyzed and converted to other nucleotide sugars by a series of 4-isomerase, 3,5-isomerase, 4-reductase, 4,6-dehydratase, 6-dehydrogenase, and decarboxylase (Reiter, 2008). Many other nucleotide sugars are abundant in plant cell walls, but there is no clear evidence that they are structural component of hemicelluloses. Studying and comprehending the process of the nucleotide sugars synthesis, interconversion, and transport can help in analysis of structures and functions, as well as the regulation of hemicellulose. In this review, we mainly encompass the synthesis and transportation of hemicellulose nucleotide sugars.

The xylan backbone consists of xylose residues linked by a β-(1→4) glycosidic bond, with reducing tetrasaccharide structure: β-D-xylose-(1→3)-α-L-rhamnose-(1→2)-α-D-galacturonic acid-(1→4)-D-xylose at the end of the xylan backbone in dicots and gymnosperms (Peña et al., 2007). Based on side chains branching, xylans can be divided into glucuronoxylan (GX), arabinoxylan (AX), and glucuronoarabinoxylan (GAX; Figure 1). The backbone of xyloglucan is composed of a β-D-(1-4)-glucan with α-D-xylosyl group attached to the 6-position hydroxyl group of approximately 75% of the glucose residues in the skeleton, and some of the 2-position hydroxyl groups of α-D-xylosyl group are additionally connected to β-D-galactosyl or α-L-amylosyl (Figure 1; Perrin et al., 2003). The hemicellulose acetylation, which was covered in our recent review paper (Qaseem et al., 2020), will not be discussed in this article since it does not belong to the sugar substrates. The mannans backbone is inconsistent and can be divided into two categories, one consisting entirely of β-D-mannose and the other also with β-D-glucose, and the side chains of mannans are mainly α-D-galactose linked by α-(1,6) glycosidic chains (Figure 1). Therefore, depending on main chain and side chain glycosyl groups, mannans can be divided into four categories: mannan, galactomannan, glucomannan, and galactoglucomannan (Scheller and Ulvskov, 2010). Β-(1→3, 1→4)-glucans are homogeneous unbranched chain polysaccharides and composed of three or four β-D-glucose units connected by β-1, 3 bonds and β-1, 4 bonds, and the content of triose units is generally higher than that of tetraose units, while the proportion of β-1, 3 and β-1, 4 bonds varies among different sources of β-glucans (Figure 1; Hu et al., 2015; Zielke et al., 2018; Chang et al., 2021).

In addition to the maintenance of cell wall organization, hemicelluloses are important group of cell wall polysaccharides which perform many functions, such as structure of primary and secondary walls, cell expansion, seed storage carbohydrates, and aggregation to facilitate plant growth. All xylan-deficient mutants exhibit collapsed xylem vessels and have severely impaired growth and fertility with decreased mechanical strength in stem, indicating the importance of xylans in secondary wall strengthening (Scheller and Ulvskov, 2010). Some xyloglucans not only have a protective role serves as a physical barrier to prevent pathogens from invading and colonizing, and they protect plant from aluminum toxicity, but also has a vital role in cell wall extension and providing strength to plant organs as it binds along the length of cellulose microfibrils (Park and Cosgrove, 2015; Claverie et al., 2018; Galloway et al., 2018; Wan et al., 2018; Kuki et al., 2020). Recent research has revealed that Xanthomonas, the main causal pathogens of citrus bacterial canker disease, has a complicated enzymatic machinery capable of depolymerizing xyloglucans and disrupting the cell wall (Vieira et al., 2021). Function of mannan depends on tissue in which they are present; in cell wall, these have structural role and provide strength and hardness, while in seeds, they function as storage polysaccharides. The specific function of β-(1→3, 1→4)-glucan in plants is not yet clear.

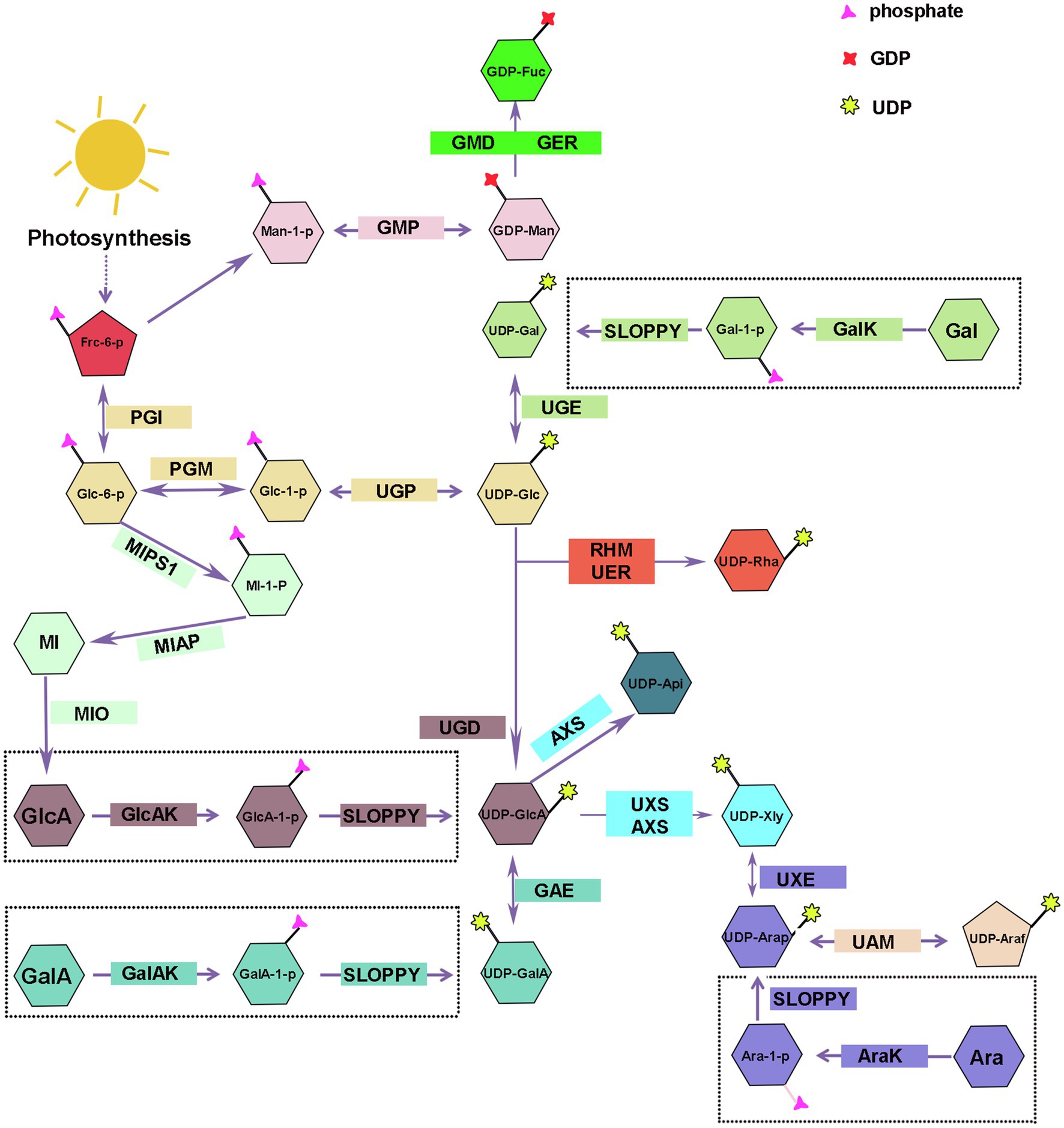

UDP-nucleotide sugars are glycosyl donors for hemicellulose biosynthesis, and their synthesis is divided into a “de novo pathway” and a “salvage pathway” (Figure 2). The majority of nucleotides are synthesized via the de novo pathway, which involves a series of sugar interconverting enzymes in the cytosol and Golgi (Bar-Peled and O’Neill, 2011). UTP is used by sugar-specific kinases and pyrophosphorylases to specifically convert free monosaccharides, breakdown produced releasing from polysaccharide, into their corresponding UDP-sugars via the “salvage” pathway (Kotake et al., 2007; Bar-Peled and O’Neill, 2011). During plant growth and development, some of hemicelluloses are metabolized or remodeled releasing free monosaccharides that gradually accumulated in the plant and finally might result in sugar toxicity (Althammer et al., 2020). SLOPPY, a recombinant protein encoded by Arabidopsis gene At5g52560, has a very strong ability to convert GlcA-1-P, Glc-1-P, Gal-1-P, Xyl-1-P, Ara-1-P, and GalA-1-P into their corresponding UDP-sugars (Yang et al., 2009; Decker and Kleczkowski, 2018). At present, we still do not know how many nucleotide sugars are provided by the “salvage” pathway in plants or if the substrate monosaccharides are produced from polysaccharide degradation in the cell wall, cytoplasm, or both (Dhonukshe et al., 2006).

Figure 2. Biosynthesis of nucleotide sugars for plant hemicellulose. Frc-6-P, Fructose-6-phosphate; Glc-1-P, Glucose-1-Phosphate; Man-1-P, Mannose-1-Phosphate; UDP-Glc, uridine diphosphate glucose; UDP-GlcA, UDP-glucuronate; UDP-Api, UDP-Apiose; Xyl, UDP-xylose; UDP-Gal, UDP-galactose; UDP-GalA, UDP-galacturonate; UDP-UDP-Ara, UDP-arabinose; UDP-Rha, UDP-rhamnose; GDP-Man, guanosine diphosphate-mannose; GDP-Fuc, GDP-fucose; UGP, uridine diphosphate glucose pyrophosphorylase; GMP, guanosine diphosphate-mannose pyrophosphorylases; UGE, UDP-galactose/glucose 4-epimerase; GalK, galactokinase; UGD, UDP-D-glucose dehydrogenase; GlcAK, glucuronide kinase; GAE, UDP-GlcA 4-epimerase; GalAK, GalA kinase; UXS, UDP-GlcA decarboxylase; AXS, UDP-D-apiose/UDP-D-xylose synthase; UXE, UDP-Xyl epimerase; UAM, UDP-arabinopyranose mutase; RHM, rhamnose synthase; UER, UDP-4-keto- 6-deoxy-D-glucose 3, 5-epimerase 4-reductase; GMD, GDP-mannose-4, 6-dehydratase; GER, GDP-4-keto-6-deoxymannose-3, 5-epimerase −4-reductase (GDP-fucose synthetase); MIPS1, myo-inositol-1-phosphatase synthase; MI-1-P, myo-inositol-1-phosphatase; MIAP, myo-inositol alkaline phosphatase; MI, myo-inositol; MIO, myo-inositol oxidase.

UDP-Glc and GDP-Man are the starting compounds for the synthesis of all hemicellulose riboside sugars. Fructose-6-phosphate (Fru-6-P), the photosynthetic intermediate, is converted to glucose-1-phosphate (Glc-1-P) and mannose-1-phosphate (Man-1-P) by the collective effect of phosphate-sugar isomerase and metathesis enzymes, and then, uridine diphosphate glucose pyrophosphorylase/guanosine diphosphate-mannose pyrophosphorylases (UGP/GMP) convert reversibly Glc-1-P and Man-1-P into UDP-Glc and GDP-Man in cytosol (Reiter, 2008; Figure 2). Munch Petersen discovered UGP in yeast cells for the first time in 1953. There are two genes encoding UGP in Arabidopsis (Meng et al., 2009) and rice (Long et al., 2017). Silencing Atugp1/Atugp2 genes in Arabidopsis reduces the activity of UGP and reduces seed yield by 50% (Meng et al., 2009). As the most abundant nucleotide sugars in plants, UDP-Glc can be obtained through two other sources addition to above-mentioned pathways. Sucrose synthase can reversibly catalyze the degradation of sucrose to UDP-glucose and fructose; however, in the presence of UDP, glucose inhibits the reaction in both directions (Ruan et al., 2003; Reiter, 2008; Abdullah et al., 2018). Gal, Glc, and Man produced by the degradation of plant cell wall polysaccharides can also be used as substrates for UDP-Glc (Figure 2). Some plants glycosyltransferases can catalyze the interconversion of sugar molecules between the oligosaccharyl in glucoside and other UDP-monosaccharides to compose UDP-Glc in the presence of UDP (Bode and Muller, 2007; Bar-Peled and O’Neill, 2011).

Galactose is important for the plant growth and occupies a large proportion in a variety of hemicellulose polysaccharides, such as xyloglucan and galactomannan (Scheller and Ulvskov, 2010). There are two mechanisms for the synthesis of UDP-Gal: the de novo pathway and the “salvage” pathway.

UDP-galactose/glucose 4-epimerase (UGE) catalyzes the interconversion of UDP-Glc and UDP-Gal, and the reaction is reversible (Figure 2). There are two types of UGE in vascular plants. In addition to catalyzing the conversion of UDP-glucose and UDP-galactose, one type of UGE can also reversibly convert UDP-xylose and UDP-arabinose, and different types of UGE have different catalytic efficiency of UDP-xylose in different plants (Guevara et al., 2014; Yin et al., 2016a). There are five AtUGE genes in the Arabidopsis genome, all of them have catalytic activity. AtUGE1 and AtUGE3 mainly catalyze the conversion of UDP-galactose to UDP-glucose, while AtUGE2, AtUGE4, and AtUGE5 mainly catalyze the conversion of UDP-glucose to UDP-galactose (Seifert, 2004). Reverse genetic studies of these five genes revealed no significant phenotypic changes in the single mutant. However, a significant decrease in the galactose content was seen in cell wall of double mutant, indicating that the UGE proteins of different isoforms have functional redundancy and synergy (Seifert, 2004; Rösti et al., 2007) and participate in many physiological processes, such as cell growth and differentiation, cell-to-cell communication, and defense responses by regulating the interconversion of nucleotide sugars (Hou et al., 2021). In addition to Arabidopsis, similar phenomena have been observed in other plants, and including Oryza sativa (Kim et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2020), barley (Zhang et al., 2006), Phyllostachys edulis (Sun et al., 2016), and Ornithogalum caudatum (Yin et al., 2016a) were reported to contain various plant UGE genes. Compared with the wild type, these studies found that the content of galactose and glucose increased in the hemicellulose polysaccharide profile of rice OsUGE1-OX overexpression plants (Guevara et al., 2014). In contrast, OsUGE2 mutation significantly reduced accumulation of arabinogalactan proteins in the cell walls, which consequently affected plant growth and cell wall deposition (Zhang et al., 2020).

Using real-time NMR spectroscopy to monitor the enzymatic reaction, the investigators confirmed that Arabidopsis galactokinase (GalK) phosphorylates galactose to Gal-1-P at position C-1. Finally, Gal-1-P is converted to UDP-Gal in the presence of SLOPPY (Yang et al., 2009; Decker and Kleczkowski, 2017; Figure 2). The AtGALK T-DNA insertion mutant (atgalk) showed no growth or morphological defects in the absence of Arabidopsis galactokinase and was unable to use free Gal and accumulated it in vegetative tissues; the phenotype was recovered by constitutively overexpressing the AtGALK cDNA (Egert et al., 2012). The toxicity of free galactose has yet to be determined, but galactose-1-phosphate or an imbalance in the sugar-1-phosphate and nucleotide sugar network can cause growth defects.

Glucuronic acid mainly exists in glucuronoxylan and glucuronoarabinolxylan (Figure 1). UDP-GlcA is a key intermediate product in the process of nucleotide sugar metabolism and direct precursor of UDP-GalA, UDP-Api, and UDP-Xyl, and critical substrate for the transformation of UDP-monosaccharides from six-carbon sugars to five-carbon sugars (Bar-Peled and O’Neill, 2011).

UDP-D-glucose dehydrogenase (UGD) action results in the irreversible elimination of hydrogen at the C-6 position, resulting in the conversion of UDP-Glc to UDP-GlcA (Figure 2). Since it was cloned in soybean in 1996 (Tenhaken and Thulke, 1996), the gene encoding UGD has been cloned in various other plants, such as Arabidopsis (Klinghammer and Tenhaken, 2007), cotton (Pang et al., 2010), Larix gmelinii (Li et al., 2014), and moso bamboo (Yang et al., 2020). Four UGD genes are identified in Arabidopsis, which differ in their enzyme kinetic properties and tissue expression specificity, including AtUGD3 having the highest activity (Klinghammer and Tenhaken, 2007). Yang and his colleagues discovered nine UGD genes with three predicted conserved domains, one of which, PeUGDH4, was found in the cytoplasm and showed strong expression in the leaf and stem. The overexpression of PeUGDH4 in Arabidopsis dramatically boosted hemicellulose production and accumulation (Yang et al., 2020). On the other hand, UDP-GlcA can also be formed via myo-inositol oxygenase pathway. D-glucose-6-phosphate is cyclized under the action of myo-inositol-1-phosphate synthase to form myo-inositol-1-phosphate, myo-inositol alkaline phosphatase catalyzes the dephosphorylation of later to form myo-inositol, and myo-inositol is oxidized to UDP-glucuronic acid by the action of myo-inositol oxidase (Lorence et al., 2004; Endres and Tenhaken, 2009; Pieslinger et al., 2010; Alford et al., 2012; Figure 2).

There are two genes in Arabidopsis (At3g01640 and At5g14470) that encode a α-D-glucuronide acid-1-phosphate kinase (GlcAK), which phosphorylates GlcA to GlcA-1-P using ATP and is then pyrophosphorylated by SLOPPY to UDP-GlcA (Geserick and Tenhaken, 2013; Figure 2).

GalA is present in xyloglucan side chain of lower plants, such as mosses, and also part of the tetrasaccharide reducing terminus of dicotyledonous and gymnosperm xyloglucan (Peña et al., 2007; Pena et al., 2008). The research on UDP-GalA synthesis-related proteins in plants started late.

UDP-GalA can reversibly transform from UDP-GlcA via UDP-GlcA 4-epimerase (UGLcAE, GAE), and the activity of GAE is NAD+-dependent (Figure 2). In 2004, three research teams identified GAE enzymes almost simultaneously and performed expression level analysis. The results showed that there were six GAE genes in the Arabidopsis genome, and all of them were localized in the Golgi apparatus and differently expressed in Arabidopsis roots, leaves, pollen, and angiosperms (Gu and Bar-Peled, 2004; Molhoj et al., 2004; Usadel et al., 2004; Rösti et al., 2007). In addition to Arabidopsis, genes encoding GAE were also identified in tomato (Ding et al., 2018), Nicotiana benthamiana (Ahmed et al., 2020), and O. caudatum (Yin et al., 2016b). UAE isoforms in different plant species have different enzymatic properties, but UAE isoform of the same plant are highly conserved. The GAE can produce UDP-GlcA and UDP-GalA in Arabidopsis, maize, and rice with a ratio of 1:2, and this reversible reaction was inhibited by UDP-Ara and UDP-Xyl, though the degree of GAE inhibition by UDP-Xyl varied among plants (Gu et al., 2009; Figure 2).

The α-D-galacturonic acid-1-phosphate kinase (GalAK) phosphorylates GalA to GalA-1-P, then GlcA-1-P can be pyrophosphorylated by SLOPPY to UDP-GalA (Decker and Kleczkowski, 2017). Arabidopsis has a single copy of the GalAK gene (At3g10700), and its catalytic activity was confirmed using real-time NMR (Yang et al., 2009). However, the extent to which UDP-GalA formed by this pathway contributes to the UDP-GalA in plants needs to be further investigated (Bar-Peled and O’Neill, 2011; Figure 2).

Xylose is a significant component of xyloglucan and xylan. With the participation of NAD+ and NADH, UDP-GlcA decarboxylase (UDP-GlcA-DC/UXS) catalyzes the decarboxylation of UDP-GlcA to form UDP-Xyl in an essentially irreversible reaction (Harper and Bar-Peled, 2002; Figure 2). The proteins encoded by the Arabidopsis UXS gene family are classified as membrane-anchored or cytoplasmic soluble. UXS1, UXS2, and UXS4 are membrane-anchored proteins that are found in the Golgi, whereas UXS3, UXS5, and UXS6 are soluble proteins that are found in the cytoplasm (Harper and Bar-Peled, 2002; Kuang et al., 2016). In Arabidopsis xylan synthesis, UXS localized in the cytoplasm plays a more essential role; however, xylosyltransferases all use UDP-Xyl in the Golgi for hemicellulose synthesis, so UDP-Xyl synthesized in the cytoplasm must be transferred to the Golgi (Kuang et al., 2016; Zhao et al., 2018). Ebert et al. (2015) discovered types of UXTs that were localized to the Golgi, and Arabidopsis has three UXT genes. Except for the Atuxt1 mutant, whose xylose concentration was significantly lower than that of the wild type, no other UXT mutant showed a clear phenotype (Harper and Bar-Peled, 2002; Ebert et al., 2015). Further, Zhao et al. (2018) identified that uxt1uxt2uxt3 triple mutants showed an uneven xylem and xylan deposition defects (Zhao et al., 2018). Like Arabidopsis, rice (O. sativa) also has six UXS genes, which were classified into three types (Suzuki et al., 2003, 2004). Subsequently, besides Arabidopsis and rice, UXS gene family with varied members has been cloned from only a few plants, for example, tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum; Bindschedler et al., 2007), Gossypium hirsutum (Pan et al., 2010), Populus tomentosa (Du et al., 2013), and O. caudatum (Yin et al., 2016b).

UDP-D-apiose/UDP-D-xylose synthase (AXS) can also produce UDP-Xyl with UDP-GlcA as substrate in plants (Figure 2). Besides, AXS can also convert UDP-GlcA to UDP-Apiose via decarboxylation and rearrangement of the carbon skeleton (Figure 2). Arabidopsis has two AtAXS genes that are ubiquitously expressed across all tissues and developmental stages, with AtAXS2 showing higher overall expression. AXS has lower enzyme activity to convert UDP-GlcA to UDP-Xyl than UXS, implying that it functions on pectin RG-II side chain A and B biosynthesis by Apiose (Zhao et al., 2020a). Although AXS and UXS can utilize the same substrate, AXS may not have evolved from UXS and both may have their own synthetic precursors (Gu et al., 2010). Under normal physiological conditions in plants, AXS plays a minor role in the synthesis of UDP-Xyl, because its optimum activity conditions close to the pH and temperature in plants (pH 5–6, temperature 20–30°C), while AXS makes a difference in harsh conditions with higher temperature (50°C) and pH optimum (pH 8.5; Yin et al., 2016b).

There are two forms of arabinose, furanose and pyranose. Arabinose is found mostly as furanose in grass xylan, and xyloglucans of pteridophytes and solanaceous plants, and is a major component of the side chains of glucuronide arabinoxylan and arabinoxylan. Pyranose, on the other hand, is thermodynamically more stable and has been detected earlier from various plants as it has been studied more extensively. The synthesis of UDP-Arap also has two ways.

UDP-Xyl epimerase (UXE) can catalyze the allosteric transition of UDP-Xyl into UDP-Arap in a reversible manner (Figure 2). The Arabidopsis genome contains four UXE genes, which encode the membrane-bound protein UXE, which is present in the Golgi apparatus. The cell wall arabinose level was drastically reduced in the AtUXE1 gene mutant mur4 screened by EMS induction; however, the ability to synthesize UDP-Arap was not completely absent (Burget and Reiter, 1999; Burget et al., 2003). Among the three UXE genes in rice, the total expression of OsUXE1 was significantly higher than OsUXE2 and OsUXE3 in mature rice, especially in the middle of the stalk, indicating that UXE1 plays a critical role in UDP-Arap production in mature rice, and the arabinose content was reduced by 2.19% in the cell wall of the rice ux1uxe2 double mutant compared with the wild type (Chen et al., 2021).

Arabinose kinase (AraK) can use Ara as a substrate and phosphorylate it to Ara-1-P, which later can be pyrophosphorylated to UDP-Arap by SLOPPY (Neufeld et al., 1960; Figure 2). There are two AraKs in the Arabidopsis genome (AT4G16130, ARA1; AT3G42850, ARA2), and ara1 mutants have lost AraK activity and have diminished metabolism of arabinose (Gy et al., 1998). The free arabinose content in plants increased significantly after mutation of the ARA1 gene, whereas the ara2 mutant did not accumulate free arabinose, probably because of the relatively low expression of the ARA2 gene (Behmüller et al., 2016).

After UDP-Arap is synthesized, UDP-arabinopyranose mutase (UAM) isomerizes it into UDP-Araf in the cytoplasm, which is then transferred to the Golgi apparatus to participate in polysaccharide synthesis (Figure 2). The interconversion of UDP-Arap and UDP-Araf is reversible, and the reaction tends to produce pyranose products. Rice, like Arabidopsis and pea, has three UAM proteins (UAM1-3), with 80% of them localized in the cytoplasm (Klinghammer and Tenhaken, 2007). Willis et al. (2016) used RNAi to downregulate the expression of the PvUAM1 gene in switchgrass, and the arabinose associated with the cell wall was reduced by more than 50% in the mutant leaves and stems, resulting in a compensatory response with increased cellulose and lignin content (Willis et al., 2016). Honta et al. (2018) used RNAi to downregulate four NcUAM genes and found that, compared to the WT, arabinose content was diminished by 35% in NtUAM-KD cell walls (Honta et al., 2018).

Rhamnose, also known as 6-deoxy-L-mannose, is used in the synthesis of the reduced tetrasaccharide terminus of xylan in dicotyledonous and gymnosperm (Peña et al., 2007; Jiang et al., 2021). The conversion of UDP-Glc to UDP-Rha in bacteria requires three enzymatic sequences: dehydratase, isomerase, and reductase, while in plants, it require rhamnose synthase (RHM) and UDP-4-keto-6-deoxy-D-glucose 3, 5-epimerase 4-reductase (NRS/UER; Watt et al., 2004; Oka et al., 2007; Figure 2). RHM possesses three enzymatically active structural domains (RHM1; RHM2; RHM3) and catalyzes the three-step reaction of the substrate UDP-glucose to produce UDP-Rha in the presence of cofactors NAD+ and NADPH (Reiter and Vanzin, 2001; Oka et al., 2007). AtRHM1 was found practically everywhere, with higher levels of expression in roots and cotyledons. Overexpression of the AtRHM1 gene in Arabidopsis resulted in a 40% increase in rhamnose content in the cell wall as compared to the wild type (Wang et al., 2009). One or more RHM genes were found in a variety of plants, including Lobelia erinus (Hsu et al., 2017), Camellia sinensis (Dai et al., 2018), prunes, and peaches (Zhao et al., 2020b), and the recombinant proteins were shown to catalyze the production of UDP-rhamnose from UDP-glucose by enzymatic analysis and in vitro enzymatic reaction.

The At1g6300 gene, which encodes UDP-4-keto-6-deoxy-D-glucose3,5-epimerase/UDP-4-keto-rhamnose 4-keto-reductase (NRS/UER), was also discovered in Arabidopsis, and the amino acids encoded by AtNRS/UER are highly similar to the C-terminal sequence of AtRHM2 amino acids, with both isomerase and reductase (Watt et al., 2004). The fusion enzyme (VvRHM-NRS) may convert UDP-glucose to UDP-rhamnose by fusing the N-terminus of VvRHM with the bifunctional (NRS/UER) from Arabidopsis. However, it is unclear how NRS/UER function in vivo (Pei et al., 2018).

Fucose is mainly present in pectin and seed coat mucilage, less in hemicellulose, and only the side chain of xyloglucan contains a small amount of GDP-Fuc (Pena et al., 2008; Bar-Peled and O’Neill, 2011).

GDP-Fuc is converted from GDP-man, which involves three sequential enzyme processes, just like the conversion from UDP-Glc to UDP-Rha. GDP-mannose-4, 6-dehydratase (GMD) is a key enzyme in the GDP-fucose synthesis pathway, catalyzing the formation of GDP-4-keto-6-deoxy-D-mannose from GDP-D-mannose, and then, in the presence of NADPH, the GDP-4-keto-6-deoxymannose-3, 5-epimerase-4-reductase (GDP-fucose synthetase, GER) catalyzed the conversion of the intermediate into GDP-Fuc (Figure 2). GER contains two enzymatic activity domains, epimerase and reductase, and it has been shown that this system can catalyze epimerism of substrates even in the absence of NADPH, indicating that epimerism and reduction reactions are carried out independently (Menon et al., 1999). At1g73250 (GER1) and At1g17890 (GER2) encode GER isoforms with 88 percent sequence similarity (Bar-Peled and O’Neill, 2011). In Arabidopsis, two genes, that is, GMD1 and GMD2 (MUR1), encode for GMD, with GMD2 being the major housekeeping gene and expressed in most cell types of the root, while GMD1 is expressed in the root tip, juvenile stipule organs, and pollen grains (Bonin et al., 2003). Arabidopsis mur1 mutant lacks GMD2 in the aboveground portion and has almost no fucose in the cell wall, and biochemical assays indicate that the nucleotide sugar conversion is blocked in the first step, and the GMD is mutated (Bonin et al., 1997; Bonin and Reiter, 2000; Freshour et al., 2003). Compared to wild-type plants, 80 percent of N. benthamiana plants with GMD repression using virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) and RNA interference (RNAi) were fucose-free in total soluble protein (Matsuo and Matsumura, 2011).

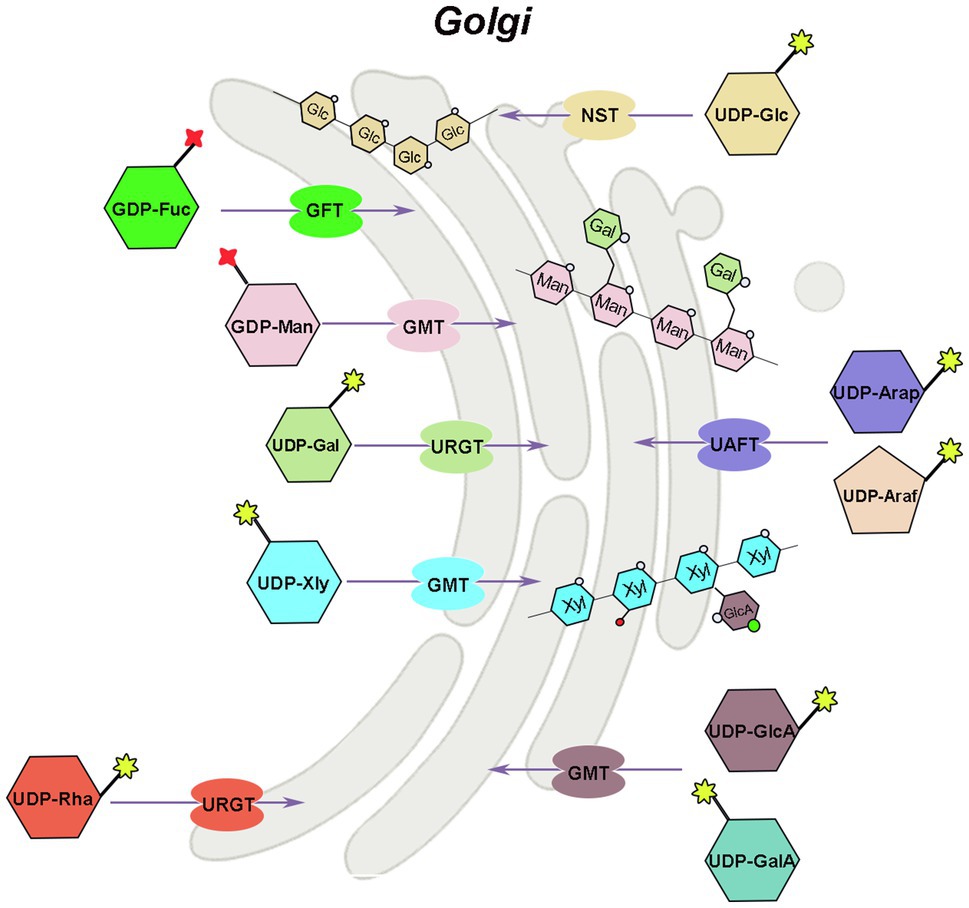

Hemicellulose is synthesized by glycosyltransferases in the Golgi apparatus, which are type II transmembrane proteins with functional structural domains in the Golgi lumen (Reyes and Orellana, 2008). The majority of nucleotide sugar synthases and all salvage pathway-related enzymes are found in the cytoplasm, whereas GAE, UXE, and a portion of UXS are found in the Golgi apparatus, that is, place where hemicellulose synthesis occurs. The related glycosyltransferases can directly use the nucleotide sugars produced in the Golgi apparatus (GTs). However, the nucleotide sugars in the cytoplasm must therefore be transported to the Golgi apparatus to added to specific polysaccharide acceptors and participate in hemicellulose synthesis (Figure 3). Because the phosphate groups in nucleotide sugars have a high molecular mass (500–650Da) and a negative charge, they cannot diffuse directly across membranes and must be transported by nucleotide sugar transporters (NST), which are antiporters that exchange nucleoside monophosphate for specific NDP-sugars (Orellana et al., 2016; Figure 3). NST generally contains 300–350 amino acids and has 6–10 transmembrane domains (Handford et al., 2006). Plant NSTs belongs to the nucleotide sugar transporter/triose phosphate translocator (NST-TPT) super-family, and the NST-TPT gene family of Arabidopsis has 51 members, which can be divided into six clades and are generally highly substrate-specific (Knappe et al., 2003; Rautengarten et al., 2014). Except for UDP-GalA and UDP-Arap, all other transport proteins of hemicellulose substrate nucleotide sugars have been identified in a variety of plants, including Arabidopsis (Baldwin et al., 2001; Norambuena et al., 2002, 2005; Knappe et al., 2003; Handford et al., 2004, 2012; Rollwitz et al., 2006; Rautengarten et al., 2008, 2011, 2014; Mortimer et al., 2013; Saez-Aguayo et al., 2017), rice (Zhang et al., 2011), tobacco, grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.), and Dendrobium officinale (Yu et al., 2018).

Figure 3. Mechanism of hemicellulose substrate transport. UTR, UDP-galactose/UDP-glucose transporter; URGT, UDP-Rha/UDP-Gal transporter; UAFT, UDP-arabinofuranose transporter; UXT, UDP-Xyl transporter; UAfT, UDP-Araf transporter proteins; GFT, GDP-fucose transporter; GMT, GDP-mannose transporter.

There are two ways to identify the function of NST, the most direct way is to analyze its biochemical activity, and the other way is to screen for mutants of the NST gene. Joshua Heazlewood’s team at the University of Melbourne has developed a rapid method for measuring NST biochemical activity, and in combination with Arabidopsis mutant analysis, the function of individual genes was rapidly unraveled in the NST-TPT family (Rautengarten et al., 2014, 2017; Saez-Aguayo et al., 2017). Substrate-specific examination of plant NSTs indicated that certain NSTs can transport two or more UDP-sugars, and many NSTs maintain their ability to transport either UDP-glucose or UDP-galactose (Orellana et al., 2016).

The AtUTr1 gene that transports both UDP-Gal and UDP-Glc was discovered in 2000 by Norambuena et al. (2002; Figure 3). The tobacco plant expressing human UDP-galactose transporter gene 1 (hUGT1) showed significantly higher galactose to total monosaccharide ratios in the hemicellulose and pectin fractions of transgenic plants compared to control plants, enhanced growth, and increased chlorophyll and lignin accumulation (Abedi et al., 2016). There are six UDP-Rha/UDP-Gal transporter (URGT) in the Arabidopsis genome, which are localized to the Golgi apparatus, and all have detectable transporter activity, while mutants of URGT2 gene have significantly reduced Rha content in the seed coat mucilage, and URGT1 and URGT2 overexpressing Arabidopsis have significantly increased Gal content in their cell walls (Rautengarten et al., 2014; Figure 3). The upregulation of UDP-arabinofuranose transporter protein (UAFT2) suggests the existence of compensatory mechanisms triggered by URGT2 deficiency, and URGT2 overexpression in urgt1 mutant rescues reduced galactose in Arabidopsis rosette leaves (Parra-Rojas et al., 2019; Celiz-Balboa et al., 2020). In addition, it has also been shown that the UDP-Gal transporter, named AtUTr2, is located in the Golgi apparatus and is highly expressed in the root and calli (Norambuena et al., 2005). The nucleotide sugar transporter (GONST1) localized to the Golgi apparatus in Arabidopsis was identified as the GDP-mannose transporter (GMT; Baldwin et al., 2001; Figure 3). Yu et al. (2018) also cloned three DoGMT genes in Dendrobium which are mainly expressed in the stem (Yu et al., 2018). In Arabidopsis, a UUAT1 gene was identified, which produces a Golgi-localized protein that transports UDP-GlcA and UDP-GalA in vitro (Saez-Aguayo et al., 2017). There are three UDP-Xyl transporters (UXT; UXT1, AT2G28315; UXT2, AT2G30460; and UXT3, AT1G06890) in the Arabidopsis genome. Mutants of the UXT1 gene have significantly reduced Xyl content in the cell wall, and triple mutant exhibits collapsed vessels and reduced cell wall thickness and significantly affected xylan content and fine structure (Ebert et al., 2015; Saez-Aguayo et al., 2017; Zhong et al., 2017). The discovery of the UXT genes and the research results on the uxt mutants suggest that the UDP-Xyl in the cytoplasm is very essential for the growth and development of Arabidopsis. Four genes in the Arabidopsis NST family encode UDP-Araf transporter proteins (UAfT) localized in the Golgi apparatus (Figure 3). Compared with the wild type, the phenotype of the uaft mutant did not change significantly, but the Ara content in the cell wall of the uaft4 mutant leaves was decreased (Rautengarten et al., 2017). GDP-fucose transporter (GFT), which can import GDP-fucose into the Golgi, has now been identified from Phaeodactylum tricornutum and Arabidopsis (Rautengarten et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2019). The GFT1-silenced plants exhibited severe growth inhibition or even death, with up to 80% decrease in fucose content in cell wall-derived xyloglucan and rhamnogalacturonan II (Rautengarten et al., 2016).

Forward and reverse genetic approaches, as well as biochemical enzyme analyses, have recently made significant advances in hemicellulose biosynthesis. Pair genes of IRX9/IRX9L, IRX14/IRX14L, and IRX10/IRX10L involved in xylan backbone elongation by added substrate UDP-Xyl in the Golgi (Brown et al., 2007, 2009; Wu et al., 2009, 2010; Hornblad et al., 2013; Jensen et al., 2014). FRA8, PARVUS, and IRX8 mainly participate in reducing end biosynthesis by adding substrate UDP-Xyl, UDP-Rha, and UDP-GalA to the xylan backbone (Brown et al., 2007, 2009; Wu et al., 2009). Likewise, five glucuronic acid substitution of xylan (GUX) genes are involved in side chain decoration and catalyze the attachment of UDP-GlcA and other nucleotide sugars to the xylan backbone (Lee et al., 2012; Rennie et al., 2012; Bromley et al., 2013).

The β-1,4-glucan synthase, α-1,6-xylosyltransferase, β-1,2-galactosyltransferase, and α-1,2-fucosyltransferase play primary role in xyloglucan biosynthesis, and the former synthesizes the glucan backbone and different types of glycosyl transferases produce the broad diversity of XyG side chain to decorate the glucan chain (Zabotina, 2012). CSLC4 gene from GT2 family encodes for β-1,4-glucan synthase, which enzyme synthesis of xyloglucan backbone with UDP-Glc as substrate, and α-1,6-xylosyltransferase encoded by five genes of GT34 family, XXT1-5, also involved in xyloglucan backbone synthesis by affixing UDP-Xyl (Faik et al., 2002; Cocuron et al., 2007; Liepman and Cavalier, 2012; Vuttipongchaikij et al., 2012). MUR3, XLT2, XUT1, and the XSTs are part of the same subclade of GT47 involved in xyloglucan synthesis or side chain decoration by substituting two different UDP-Xyl residues for UDP-Glc or other nucleotide sugars (Zabotina, 2012; Jensen et al., 2014).

The CSLD gene family and GT2 family members, CSLA2, CSLA7, and CSLA9, are involved in mannan biosynthesis (Dhugga et al., 2004; Liepman et al., 2005; Verhertbruggen et al., 2011). The recombinant CSLA protein catalyzes the production of mannans when GDP-Man is used as a substrate, and the same protein produces glucomannan with the substrate of a mixture of GDP-Man and GDP-Glc (Liepman et al., 2005). The Csl family of CslF and CslH proteins is the major components of β-(1→3, 1→4)-glucan synthase, and each of them can independently involve in the biosynthesis of the later linking multiple UDP-Glc with β-1→3 or β-1→4-glycosidicor, while CslF proteins and CslH proteins do not need to be active at the same time (Burton et al., 2006; Doblin et al., 2009; Chang et al., 2021).

The hemicellulose content and composition vary with different plant species or within the same plant during different growth phases, tissues, and cell types, so do their nucleoside substrates. Many genes involved in the biosynthesis and transport of the substrate nucleotides sugars for hemicellulose were studied in vitro and in vivo. However, the absorption and utilization of nucleoside sugars are a balance. Multiple nucleoside sugars may be affected if one gene or one substrate is changed or mutated. So, we must employ a systemic approach to investigate nucleotide sugar changes using high-throughput multi-omics analysis, such as transcriptome-proteome-metabolism analysis. It is also unknown which transcription factors regulate nucleotide sugar synthesis networks and how they do so. These researches will provide a better insight into the interconversion and regulation of hemicellulose substrates. As research progressed, researchers found that NST is substrate-specific and can only transport one or two nucleotide sugars specifically. With the continuous development of live cell imaging technology, the spatial and temporal resolution of in vivo observation has been greatly improved, making it possible to track the transport process of NST in real time, which can provide a clearer understanding of how NSTs, such as GMT and UAFT, transport nucleotide sugars.

The regarding interconversion of nucleotides sugars and hemicellulose synthesis needs to be further explored in depth. At the same time, CRISPR/CAS9 gene editing technology can be used to knock out nucleotide sugars biosynthesis and transport genes in plants, besides Arabidopsis, to alter the composition and structure of hemicellulose and improve hemicellulose and biofuel utilization in future.

WZ drafted the manuscript. WQ constructed figures. HL searched the literature and provided suggestions for writing. AW conceived the project and gave suggestions on the revision of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This work was supported by China and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Numbers 31870653, 31670670, and 31811530009).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abdullah, M., Cao, Y., Cheng, X., Meng, D., Chen, Y., Shakoor, A., et al. (2018). The sucrose synthase gene family in Chinese pear (Pyrus bretschneideri Rehd.): structure, expression, and evolution. Molecules 23:1144. doi: 10.3390/molecules23051144

Abedi, T., Khalil, M. F., Asai, T., Ishihara, N., Kitamura, K., Ishida, N., et al. (2016). UDP-galactose transporter gene hUGT1 expression in tobacco plants leads to hyper-galactosylated cell wall components. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 121, 573–583. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2015.09.014

Ahmed, R. I., Ren, A., Yang, D., Ding, A., and Kong, Y. (2020). Identification and characterization of pectin related gene NbGAE6 through virus-induced gene silencing in Nicotiana benthamiana. Gene 741:144522. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2020.144522

Alford, S. R., Rangarajan, P., Williams, P., and Gillaspy, G. E. (2012). Myo-inositol oxygenase is required for responses to low energy conditions in Arabidopsis thaliana. Front. Plant Sci. 3:69. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2012.00069

Althammer, M., Blochl, C., Reischl, R., Huber, C. G., and Tenhaken, R. (2020). Phosphoglucomutase is not the target for galactose toxicity in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 11:167. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.00167

Baldwin, T. C., Handford, M. G., Yuseff, M. I., Orellana, A., and Dupree, P. (2001). Identification and characterization of GONST1, a golgi-localized GDP-mannose transporter in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 13, 2283–2295. doi: 10.1105/tpc.010247

Bar-Peled, M., and O’Neill, M. A. (2011). Plant nucleotide sugar formation, interconversion, and salvage by sugar recycling. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 62, 127–155. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042110-103918

Behmüller, R., Kavkova, E., Düh, S., Huber, C. G., and Tenhaken, R. (2016). The role of arabinokinase in arabinose toxicity in plants. Plant J. 87, 376–390. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13206

Bindschedler, L. V., Tuerck, J., Maunders, M., Ruel, K., Petit-Conil, M., Danoun, S., et al. (2007). Modification of hemicellulose content by antisense down-regulation of UDP-glucuronate decarboxylase in tobacco and its consequences for cellulose extractability. Phytochemistry 68, 2635–2648. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2007.08.029

Bode, H. B., and Muller, R. (2007). Reversible sugar transfer by glycosyltransferases as a tool for natural product (bio)synthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Eng. 46, 2147–2150. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604671

Bonin, C. P., Freshour, G., Hahn, M. G., Vanzin, G. F., and Reiter, W. D. (2003). The GMD1 and GMD2 genes of Arabidopsis encode isoforms of GDP-D-mannose 4,6-dehydratase with cell type-specific expression patterns. Plant Physiol. 132, 883–892. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.022368

Bonin, C. P., Potter, I., Vanzin, G. F., and Reiter, W. D. (1997). The MUR1 gene of Arabidopsis thaliana encodes an isoform of GDP-D-mannose-4,6-dehydratase, catalyzing the first step in the de novo synthesis of GDP-L-fucose. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 94, 2085–2090. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.5.2085

Bonin, C. P., and Reiter, W. D. (2000). A bifunctional epimerase-reductase acts downstream of the MUR1 gene product and completes the de novo synthesis of GDP-L-fucose in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 21, 445–454. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00698.x

Bromley, J. R., Busse-Wicher, M., Tryfona, T., Mortimer, J. C., Zhang, Z., Brown, D. M., et al. (2013). GUX1 and GUX2 glucuronyltransferases decorate distinct domains of glucuronoxylan with different substitution patterns. Plant J. 74, 423–434. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12135

Brown, D. M., Goubet, F., Wong, V. W., Goodacre, R., Stephens, E., Dupree, P., et al. (2007). Comparison of five xylan synthesis mutants reveals new insight into the mechanisms of xylan synthesis. Plant J. 52, 1154–1168. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03307.x

Brown, D. M., Zhang, Z., Stephens, E., Dupree, P., and Turner, S. R. (2009). Characterization of IRX10 and IRX10-like reveals an essential role in glucuronoxylan biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 57, 732–746. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03729.x

Burget, E. G., and Reiter, W. D. (1999). The mur4 mutant of arabidopsis is partially defective in the de novo synthesis of uridine diphospho L-arabinose. Plant Physiol. 121, 383–389. doi: 10.1104/pp.121.2.383

Burget, E. G., Verma, R., Molhoj, M., and Reiter, W. D. (2003). The biosynthesis of L-arabinose in plants: molecular cloning and characterization of a Golgi-localized UDP-D-xylose 4-epimerase encoded by the MUR4 gene of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 15, 523–531. doi: 10.1105/tpc.008425

Burton, R. A., Wilson, S. M., Hrmova, M., Harvey, A. J., Shirley, N. J., Medhurst, A., et al. (2006). Cellulose synthase-like CslF genes mediate the synthesis of cell wall (1,3;1,4)-beta-D-glucans. Science 311, 1940–1942. doi: 10.1126/science.1122975

Celiz-Balboa, J., Largo-Gosens, A., Parra-Rojas, J. P., Arenas-Morales, V., Sepulveda-Orellana, P., Salinas-Grenet, H., et al. (2020). Functional interchangeability of nucleotide sugar transporters URGT1 and URGT2 reveals that urgt1 and urgt2 cell wall chemotypes depend on their Spatio-temporal expression. Front. Plant Sci. 11:594544. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.594544

Chang, S. C., Saldivar, R. K., Liang, P. H., and Hsieh, Y. (2021). Structures, biosynthesis, and physiological functions of (1,3;1,4)-beta-D-glucans. Cell 10:510. doi: 10.3390/cells10030510

Chen, C., Zhao, X., Wang, X., Wang, B., Li, H., Feng, J., et al. (2021). Mutagenesis of UDP-xylose epimerase and xylan arabinosyl-transferase decreases arabinose content and improves saccharification of rice straw. Plant Biotechnol. J. 19, 863–865. doi: 10.1111/pbi.13552

Claverie, J., Balacey, S., Lemaitre-Guillier, C., Brule, D., Chiltz, A., Granet, L., et al. (2018). The cell wall-derived Xyloglucan is a new DAMP triggering plant immunity in vitis vinifera and Arabidopsis thaliana. Front. Plant Sci. 9:1725. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.01725

Cocuron, J. C., Lerouxel, O., Drakakaki, G., Alonso, A. P., Liepman, A. H., Keegstra, K., et al. (2007). A gene from the cellulose synthase-like C family encodes a beta-1,4 glucan synthase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104, 8550–8555. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703133104

Dai, X., Zhao, G., Jiao, T., Wu, Y., Li, X., Zhou, K., et al. (2018). Involvement of three CsRHM genes from Camellia sinensis in UDP-Rhamnose biosynthesis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 66, 7139–7149. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.8b01870

Decker, D., and Kleczkowski, L. A. (2017). Substrate specificity and inhibitor sensitivity of plant UDP-sugar producing pyrophosphorylases. Front. Plant Sci. 8:1610. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.01610

Decker, D., and Kleczkowski, L. A. (2018). UDP-sugar producing pyrophosphorylases: distinct and essential enzymes with overlapping substrate specificities, providing de novo precursors for glycosylation reactions. Front. Plant Sci. 9:1822. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.01822

Dhonukshe, P., Baluška, F., Schlicht, M., Hlavacka, A., Šamaj, J., Friml, J., et al. (2006). Endocytosis of cell surface material mediates cell plate formation during plant cytokinesis. Dev. Cell 10, 137–150. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.11.015

Dhugga, K. S., Barreiro, R., Whitten, B., Stecca, K., Hazebroek, J., Randhawa, G. S., et al. (2004). Guar seed beta-mannan synthase is a member of the cellulose synthase super gene family. Science 303, 363–366. doi: 10.1126/science.1090908

Ding, X., Li, J., Pan, Y., Zhang, Y., Ni, L., Wang, Y., et al. (2018). Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of the UGlcAE gene family in tomato. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19:1583. doi: 10.3390/ijms19061583

Doblin, M. S., Pettolino, F. A., Wilson, S. M., Campbell, R., Burton, R. A., Fincher, G. B., et al. (2009). A barley cellulose synthase-like CSLH gene mediates (1,3;1,4)-beta-D-glucan synthesis in transgenic Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106, 5996–6001. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902019106

Du, Q., Pan, W., Tian, J., Li, B., and Zhang, D. (2013). The UDP-glucuronate decarboxylase gene family in Populus: structure, expression, and association genetics. PLoS One 8:e60880. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060880

Ebert, B., Rautengarten, C., Guo, X., Xiong, G., Stonebloom, S., Smith-Moritz, A. M., et al. (2015). Identification and characterization of a Golgi-localized UDP-xylose transporter family from Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 27, 1218–1227. doi: 10.1105/tpc.114.133827

Egert, A., Peters, S., Guyot, C., Stieger, B., and Keller, F. (2012). An Arabidopsis T-DNA insertion mutant for galactokinase (AtGALK, At3g06580) hyperaccumulates free galactose and is insensitive to exogenous galactose. Plant Cell Physiol. 53, 921–929. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcs036

Endres, S., and Tenhaken, R. (2009). Myoinositol oxygenase controls the level of myoinositol in Arabidopsis, but does not increase ascorbic acid. Plant Physiol. 149, 1042–1049. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.130948

Faik, A., Price, N. J., Raikhel, N. V., and Keegstra, K. (2002). An Arabidopsis gene encoding an alpha-xylosyltransferase involved in xyloglucan biosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99, 7797–7802. doi: 10.1073/pnas.102644799

Freshour, G., Bonin, C. P., Reiter, W. D., Albersheim, P., Darvill, A. G., and Hahn, M. G. (2003). Distribution of fucose-containing xyloglucans in cell walls of the mur1 mutant of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 131, 1602–1612. doi: 10.1104/pp.102.016444

Galloway, A. F., Pedersen, M. J., Merry, B., Marcus, S. E., Blacker, J., Benning, L. G., et al. (2018). Xyloglucan is released by plants and promotes soil particle aggregation. New Phytol. 217, 1128–1136. doi: 10.1111/nph.14897

Geserick, C., and Tenhaken, R. (2013). UDP-sugar pyrophosphorylase controls the activity of proceeding sugar-1-kinases enzymes. Plant Signal. Behav. 8:e25478. doi: 10.4161/psb.25478

Gibeaut, D. M., Pauly, M., Bacic, A., and Fincher, G. B. (2005). Changes in cell wall polysaccharides in developing barley (Hordeum vulgare) coleoptiles. Planta 221, 729–738. doi: 10.1007/s00425-005-1481-0

Gu, X., and Bar-Peled, M. (2004). The biosynthesis of UDP-galacturonic acid in plants. Functional cloning and characterization of Arabidopsis UDP-D-glucuronic acid 4-epimerase. Plant Physiol. 136, 4256–4264. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.052365

Gu, X., Glushka, J., Yin, Y., Xu, Y., Denny, T., Smith, J., et al. (2010). Identification of a bifunctional UDP-4-keto-pentose/UDP-xylose synthase in the plant pathogenic bacterium Ralstonia solanacearum strain GMI1000, a distinct member of the 4,6-dehydratase and decarboxylase family. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 9030–9040. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.066803

Gu, X., Wages, C. J., Davis, K. E., Guyett, P. J., and Bar-Peled, M. (2009). Enzymatic characterization and comparison of various poaceae UDP-GlcA 4-epimerase isoforms. J. Biochem. 146, 527–534. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvp099

Guevara, D. R., El-Kereamy, A., Yaish, M. W., Mei-Bi, Y., and Rothstein, S. J. (2014). Functional characterization of the rice UDP-glucose 4-epimerase 1, OsUGE1: a potential role in cell wall carbohydrate partitioning during limiting nitrogen conditions. PLoS One 9:e96158. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096158

Gy, I., Aubourg, S., Sherson, S., Cobbett, C. S., Cheron, A., Kreis, M., et al. (1998). Analysis of a 14-kb fragment containing a putative cell wall gene and a candidate for the ARA1, arabinose kinase, gene from chromosome IV of Arabidopsis thaliana. Gene 209, 201–210. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(98)00049-3

Handford, M., Rodríguez-Furlán, C., Marchant, L., Segura, M., Gómez, D., Alvarez-Buylla, E., et al. (2012). Arabidopsis thaliana AtUTr7 encodes a golgi-localized UDP-glucose/UDP-galactose transporter that affects lateral root emergence. Mol. Plant 5, 1263–1280. doi: 10.1093/mp/sss074

Handford, M., Rodriguez-Furlan, C., and Orellana, A. (2006). Nucleotide-sugar transporters: structure, function and roles in vivo. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 39, 1149–1158. doi: 10.1590/S0100-879X2006000900002

Handford, M. G., Sicilia, F., Brandizzi, F., Chung, J. H., and Dupree, P. (2004). Arabidopsis thaliana expresses multiple Golgi-localised nucleotide-sugar transporters related to GONST1. Mol. Gen. Genomics. 272, 397–410. doi: 10.1007/s00438-004-1071-z

Harper, A. D., and Bar-Peled, M. (2002). Biosynthesis of UDP-xylose. Cloning and characterization of a novel Arabidopsis gene family, UXS, encoding soluble and putative membrane-bound UDP-glucuronic acid decarboxylase isoforms. Plant Physiol. 130, 2188–2198. doi: 10.1104/pp.009654

Honta, H., Inamura, T., Konishi, T., Satoh, S., and Iwai, H. (2018). UDP-arabinopyranose mutase gene expressions are required for the biosynthesis of the arabinose side chain of both pectin and arabinoxyloglucan, and normal leaf expansion in Nicotiana tabacum. J. Plant Res. 131, 307–317. doi: 10.1007/s10265-017-0985-6

Hornblad, E., Ulfstedt, M., Ronne, H., and Marchant, A. (2013). Partial functional conservation of IRX10 homologs in physcomitrella patens and Arabidopsis thaliana indicates an evolutionary step contributing to vascular formation in land plants. BMC Plant Biol. 13:3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-13-3

Hou, J., Tian, S., Yang, L., Zhang, Z., and Liu, Y. (2021). A systematic review of the uridine diphosphate-galactose/Glucose-4-epimerase (UGE) in plants. Plant Growth Regul. 93, 267–278. doi: 10.1007/s10725-020-00686-1

Hsu, Y. H., Tagami, T., Matsunaga, K., Okuyama, M., Suzuki, T., Noda, N., et al. (2017). Functional characterization of UDP-rhamnose-dependent rhamnosyltransferase involved in anthocyanin modification, a key enzyme determining blue coloration in Lobelia erinus. Plant J. 89, 325–337. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13387

Hu, X., Zhao, J., Zhao, Q., and Zheng, J. (2015). Structure and characteristic of β-glucan in cereal: a review. J. Food Process. Preserv. 39, 3145–3153. doi: 10.1111/jfpp.12384

Jensen, J. K., Johnson, N. R., and Wilkerson, C. G. (2014). Arabidopsis thaliana IRX10 and two related proteins from psyllium and Physcomitrella patens are xylan xylosyltransferases. Plant J. 80, 207–215. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12641

Jiang, N., Dillon, F. M., Silva, A., Gomez-Cano, L., and Grotewold, E. (2021). Rhamnose in plants – from biosynthesis to diverse functions. Plant Sci. 302:110687. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2020.110687

Kim, S., Kim, D. H., Kim, B., Jeon, Y. M., Hong, B. S., and Ahn, J.-H. (2009). Cloning and characterization of the UDP glucose/galactose epimerases of Oryza sativa. J. Korean Soc. Appl. Biol. Chem. 52, 315–320. doi: 10.3839/jksabc.2009.056

Klinghammer, M., and Tenhaken, R. (2007). Genome-wide analysis of the UDP-glucose dehydrogenase gene family in Arabidopsis, a key enzyme for matrix polysaccharides in cell walls. J. Exp. Bot. 58, 3609–3621. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erm209

Knappe, S., Flugge, U. I., and Fischer, K. (2003). Analysis of the plastidic phosphate translocator gene family in Arabidopsis and identification of new phosphate translocator-homologous transporters, classified by their putative substrate-binding site. Plant Physiol. 131, 1178–1190. doi: 10.1104/pp.016519

Kotake, T., Hojo, S., Yamaguchi, D., Aohara, T., Konishi, T., and Tsumuraya, Y. (2007). Properties and physiological functions of UDP-sugar pyrophosphorylase in Arabidopsis. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 71, 761–771. doi: 10.1271/bbb.60605

Kuang, B., Zhao, X., Zhou, C., Zeng, W., Ren, J., Ebert, B., et al. (2016). Role of UDP-glucuronic acid decarboxylase in xylan biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Mol. Plant 9, 1119–1131. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2016.04.013

Kuki, H., Yokoyama, R., Kuroha, T., and Nishitani, K. (2020). Xyloglucan is not essential for the formation and integrity of the cellulose network in the primary cell wall regenerated from arabidopsis protoplasts. Plants 9:629. doi: 10.3390/plants9050629

Lee, C., Teng, Q., Zhong, R., and Ye, Z. (2012). Arabidopsis GUX proteins are glucuronyltransferases responsible for the addition of glucuronic acid side chains onto xylan. Plant Cell Physiol. 53, 1204–1216. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcs064

Li, N., Wang, L., Zhang, W., Takechi, K., Takano, H., and Lin, X. (2014). Overexpression of UDP-glucose pyrophosphorylase from Larix gmelinii enhances vegetative growth in transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Rep. 33, 779–791. doi: 10.1007/s00299-013-1558-3

Liepman, A. H., and Cavalier, D. M. (2012). The CELLULOSE SYNTHASE-LIKE a and CELLULOSE SYNTHASE-LIKE C families: recent advances and future perspectives. Front. Plant Sci. 3:109. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2012.00109

Liepman, A. H., Wilkerson, C. G., and Keegstra, K. (2005). Expression of cellulose synthase-like (Csl) genes in insect cells reveals that CslA family members encode mannan synthases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102, 2221–2226. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409179102

Long, W., Dong, B., Wang, Y., Pan, P., Wang, Y., Liu, L., et al. (2017). FLOURY ENDOSPERM8, encoding the UDP-glucose pyrophosphorylase 1, affects the synthesis and structure of starch in rice ENDOSPERM. J. Plant Biol. 60, 513–522. doi: 10.1007/s12374-017-0066-3

Lorence, A., Chevone, B. I., Mendes, P., and Nessler, C. L. (2004). Myo-inositol oxygenase offers a possible entry point into plant ascorbate biosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 134, 1200–1205. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.033936

Matsuo, K., and Matsumura, T. (2011). Deletion of fucose residues in plant N-glycans by repression of the GDP-mannose 4,6-dehydratase gene using virus-induced gene silencing and RNA interference. Plant Biotechnol. J. 9, 264–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2010.00553.x

Meng, M., Geisler, M., Johansson, H., Harholt, J., Scheller, H. V., Mellerowicz, E. J., et al. (2009). UDP-glucose pyrophosphorylase is not rate limiting, but is essential in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol. 50, 998–1011. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcp052

Menon, S., Stahl, M., Kumar, R., Xu, G. Y., and Sullivan, F. (1999). Stereochemical course and steady state mechanism of the reaction catalyzed by the GDP-fucose synthetase from Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 26743–26750. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.38.26743

Molhoj, M., Verma, R., and Reiter, W. D. (2004). The biosynthesis of D-galacturonate in plants. Functional cloning and characterization of a membrane-anchored UDP-D-Glucuronate 4-epimerase from Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 135, 1221–1230. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.043745

Mortimer, J. C., Yu, X., Albrecht, S., Sicilia, F., Huichalaf, M., Ampuero, D., et al. (2013). Abnormal glycosphingolipid mannosylation triggers salicylic acid-mediated responses in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 25, 1881–1894. doi: 10.1105/tpc.113.111500

Neufeld, E. F., Feingold, D. S., and Hassid, W. Z. (1960). Phosphorylation of D-galactose and L-arabinose by extracts from Phaseolus aureus seedlings. J. Biol. Chem. 235, 906–909. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)69448-7

Norambuena, L., Marchant, L., Berninsone, P., Hirschberg, C. B., Silva, H., and Orellana, A. (2002). Transport of UDP-galactose in plants. Identification and functional characterization of AtUTr1, an Arabidopsis thaliana UDP-galactos/UDP-glucose transporter. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 32923–32929. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204081200

Norambuena, L., Nilo, R., Handford, M., Reyes, F., Marchant, L., Meisel, L., et al. (2005). AtUTr2 is an Arabidopsis thaliana nucleotide sugar transporter located in the Golgi apparatus capable of transporting UDP-galactose. Planta 222, 521–529. doi: 10.1007/s00425-005-1557-x

Oka, T., Nemoto, T., and Jigami, Y. (2007). Functional analysis of Arabidopsis thaliana RHM2/MUM4, a multidomain protein involved in UDP-D-glucose to UDP-L-rhamnose conversion. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 5389–5403. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610196200

Orellana, A., Moraga, C., Araya, M., and Moreno, A. (2016). Overview of nucleotide sugar transporter gene family functions across multiple species. J. Mol. Biol. 428, 3150–3165. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2016.05.021

Pan, Y., Wang, X., Liu, H., Zhang, G., and Ma, Z. (2010). Molecular cloning of three UDP-Glucuronate decarboxylase genes that are preferentially expressed in gossypium fibers from elongation to secondary cell wall synthesis. J. Plant Biol. 53, 367–373. doi: 10.1007/s12374-010-9124-9

Pang, C. Y., Wang, H., Pang, Y., Xu, C., Jiao, Y., Qin, Y. M., et al. (2010). Comparative proteomics indicates that biosynthesis of pectic precursors is important for cotton fiber and Arabidopsis root hair elongation. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 9, 2019–2033. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M110.000349

Park, Y. B., and Cosgrove, D. J. (2015). Xyloglucan and its interactions with other components of the growing cell wall. Plant Cell Physiol. 56, 180–194. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcu204

Parra-Rojas, J. P., Largo-Gosens, A., Carrasco, T., Celiz-Balboa, J., Arenas-Morales, V., Sepúlveda-Orellana, P., et al. (2019). New steps in mucilage biosynthesis revealed by analysis of the transcriptome of the UDP-rhamnose/UDP-galactose transporter 2 mutant. J. Exp. Bot. 70, 5071–5088. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erz262

Pauly, M., and Keegstra, K. (2008). Cell-wall carbohydrates and their modification as a resource for biofuels. Plant J. 54, 559–568. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03463.x

Pei, J., Chen, A., Sun, Q., Zhao, L., Cao, F., and Tang, F. (2018). Construction of a novel UDP-rhamnose regeneration system by a two-enzyme reaction system and application in glycosylation of flavonoid. Biochem. Eng. J. 139, 33–42. doi: 10.1016/j.bej.2018.08.007

Pena, M. J., Darvill, A. G., Eberhard, S., York, W. S., and O’Neill, M. A. (2008). Moss and liverwort xyloglucans contain galacturonic acid and are structurally distinct from the xyloglucans synthesized by hornworts and vascular plants. Glycobiology 18, 891–904. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwn078

Peña, M. J., Zhong, R., Zhou, G. K., Richardson, E. A., O'Neill, M. A., Darvill, A. G., et al. (2007). Arabidopsis irregular xylem8 and irregular xylem9: implications for the complexity of glucuronoxylan biosynthesis. Plant Cell 19, 549–563. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.049320

Perrin, R. M., Jia, Z., Wagner, T. A., O'Neill, M. A., Sarria, R., York, W. S., et al. (2003). Analysis of xyloglucan fucosylation in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 132, 768–778. doi: 10.1104/pp.102.016642

Pieslinger, A. M., Hoepflinger, M. C., and Tenhaken, R. (2010). Cloning of Glucuronokinase from Arabidopsis thaliana, the last missing enzyme of the myo-inositol oxygenase pathway to nucleotide sugars. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 2902–2910. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.069369

Qaseem, M. F., and Wu, A. (2020). Balanced xylan acetylation is the key regulator of plant growth and development, and cell wall structure and for industrial utilization. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21:7875. doi: 10.3390/ijms21217875

Qaseem, M. F., and Wu, A. (2021). Marginal lands for bioenergy in China; An outlook in status, potential and management. Glob. Change Biol. Bioenergy 13, 21–44. doi: 10.1111/gcbb.12770

Rautengarten, C., Birdseye, D., Pattathil, S., McFarlane, H. E., Saez-Aguayo, S., Orellana, A., et al. (2017). The elaborate route for UDP-arabinose delivery into the Golgi of plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 114, 4261–4266. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1701894114

Rautengarten, C., Ebert, B., Herter, T., Petzold, C. J., Ishii, T., Mukhopadhyay, A., et al. (2011). The interconversion of UDP-arabinopyranose and UDP-arabinofuranose is indispensable for plant development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 23, 1373–1390. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.083931

Rautengarten, C., Ebert, B., Liu, L., Stonebloom, S., Smith-Moritz, A. M., Pauly, M., et al. (2016). The Arabidopsis Golgi-localized GDP-L-fucose transporter is required for plant development. Nat. Commun. 7:12119. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12119

Rautengarten, C., Ebert, B., Moreno, I., Temple, H., Herter, T., Link, B., et al. (2014). The Golgi localized bifunctional UDP-rhamnose/UDP-galactose transporter family of Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 111, 11563–11568. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1406073111

Rautengarten, C., Usadel, B., Neumetzler, L., Hartmann, J., Büssis, D., and Altmann, T. (2008). A subtilisin-like serine protease essential for mucilage release from Arabidopsis seed coats. Plant J. 54, 466–480. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03437.x

Reiter, W. D. (2008). Biochemical genetics of nucleotide sugar interconversion reactions. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 11, 236–243. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2008.03.009

Reiter, W. D., and Vanzin, G. F. (2001). Molecular genetics of nucleotide sugar interconversion pathways in plants. Plant Mol. Biol. 47, 95–113. doi: 10.1023/A:1010671129803

Rennie, E. A., Hansen, S. F., Baidoo, E. E. K., Hadi, M. Z., Keasling, J. D., and Scheller, H. V. (2012). Three members of the Arabidopsis glycosyltransferase family 8 are xylan glucuronosyltransferases. Plant Physiol. 159, 1408–1417. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.200964

Reyes, F., and Orellana, A. (2008). Golgi transporters: opening the gate to cell wall polysaccharide biosynthesis. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 11, 244–251. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2008.03.008

Rollwitz, I., Santaella, M., Hille, D., Flugge, U. I., and Fischer, K. (2006). Characterization of AtNST-KT1, a novel UDP-galactose transporter from Arabidopsis thaliana. FEBS Lett. 580, 4246–4251. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.06.082

Rösti, J., Barton, C. J., Albrecht, S., Dupree, P., Pauly, M., Findlay, K., et al. (2007). UDP-glucose 4-epimerase isoforms UGE2 and UGE4 cooperate in providing UDP-galactose for cell wall biosynthesis and growth of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 19, 1565–1579. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.049619

Ruan, Y. L., Llewellyn, D. J., and Furbank, R. T. (2003). Suppression of sucrose synthase gene expression represses cotton fiber cell initiation, elongation, and seed development. Plant Cell 15, 952–964. doi: 10.1105/tpc.010108

Saez-Aguayo, S., Rautengarten, C., Temple, H., Sanhueza, D., Ejsmentewicz, T., Sandoval-Ibañez, O., et al. (2017). UUAT1 is a Golgi-localized UDP-Uronic acid transporter that modulates the polysaccharide composition of Arabidopsis seed mucilage. Plant Cell 29, 129–143. doi: 10.1105/tpc.16.00465

Schadel, C., Blochl, A., Richter, A., and Hoch, G. (2010). Quantification and monosaccharide composition of hemicelluloses from different plant functional types. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 48, 1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2009.09.008

Scheller, H. V., and Ulvskov, P. (2010). Hemicelluloses. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 61, 263–289. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042809-112315

Seifert, G. J. (2004). Nucleotide sugar interconversions and cell wall biosynthesis: how to bring the inside to the outside. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 7, 277–284. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2004.03.004

Sun, H., Li, L., Lou, Y., Zhao, H., Yang, Y., and Gao, Z. (2016). Cloning and preliminary functional analysis of PeUGE gene from moso bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis). DNA Cell Biol. 35, 706–714. doi: 10.1089/dna.2016.3389

Suzuki, K., Suzuki, Y., and Kitamura, S. (2003). Cloning and expression of a UDP-glucuronic acid decarboxylase gene in rice. J. Exp. Bot. 54, 1997–1999. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erg203

Suzuki, K., Watanabe, K., Masumura, T., and Kitamura, S. (2004). Characterization of soluble and putative membrane-bound UDP-glucuronic acid decarboxylase (OsUXS) isoforms in rice. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 431, 169–177. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2004.08.029

Tenhaken, R., and Thulke, O. (1996). Cloning of an enzyme that synthesizes a key nucleotide-sugar precursor of hemicellulose biosynthesis from soybean: UDP-glucose dehydrogenase. Plant Physiol. 112, 1127–1134. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.3.1127

Usadel, B., Schlüter, U., Mølhøj, M., Gipmans, M., Verma, R., Kossmann, J., et al. (2004). Identification and characterization of a UDP-D-glucuronate 4-epimerase in Arabidopsis. FEBS Lett. 569, 327–331. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.06.005

Verhertbruggen, Y., Yin, L., Oikawa, A., and Scheller, H. V. (2011). Mannan synthase activity in the CSLD family. Plant Signal. Behav. 6, 1620–1623. doi: 10.4161/psb.6.10.17989

Vieira, P. S., Bonfim, I. M., Araujo, E. A., Melo, R. R., Lima, A. R., Fessel, M. R., et al. (2021). Xyloglucan processing machinery in Xanthomonas pathogens and its role in the transcriptional activation of virulence factors. Nat. Commun. 12:4049. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-24277-4

Vuttipongchaikij, S., Brocklehurst, D., Steele-King, C., Ashford, D. A., Gomez, L. D., and McQueen-Mason, S. J. (2012). Arabidopsis GT34 family contains five xyloglucan alpha-1,6-xylosyltransferases. New Phytol. 195, 585–595. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2012.04196.x

Wang, J., Ji, Q., Jiang, L., Shen, S., Fan, Y., and Zhang, C. (2009). Overexpression of a cytosol-localized rhamnose biosynthesis protein encoded by Arabidopsis RHM1 gene increases rhamnose content in cell wall. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 47, 86–93. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2008.10.011

Wan, J. X., Zhu, X. F., Wang, Y. Q., Liu, L. Y., Zhang, B. C., Li, G. X., et al. (2018). Xyloglucan fucosylation modulates Arabidopsis cell wall hemicellulose aluminium binding capacity. Sci. Rep. 8:428. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-18711-1

Watt, G., Leoff, C., Harper, A. D., and Bar-Peled, M. (2004). A bifunctional 3,5-epimerase/4-keto reductase for nucleotide-rhamnose synthesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 134, 1337–1346. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.037192

Willis, J. D., Smith, J. A., Mazarei, M., Zhang, J. Y., Turner, G. B., Decker, S. R., et al. (2016). Downregulation of a UDP-arabinomutase gene in switchgrass (Panicum virgatum L.) results in increased cell wall lignin while reducing arabinose-glycans. Front. Plant Sci. 7:1580. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01580

Wu, A. M., Hörnblad, E., Voxeur, A., Gerber, L., Rihouey, C., Lerouge, P., et al. (2010). Analysis of the Arabidopsis IRX9/IRX9-L and IRX14/IRX14-L pairs of glycosyltransferase genes reveals critical contributions to biosynthesis of the hemicellulose glucuronoxylan. Plant Physiol. 153, 542–554. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.154971

Wu, A. M., Rihouey, C., Seveno, M., Hörnblad, E., Singh, S. K., Matsunaga, T., et al. (2009). The Arabidopsis IRX10 and IRX10-LIKE glycosyltransferases are critical for glucuronoxylan biosynthesis during secondary cell wall formation. Plant J. 57, 718–731. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03724.x

Yang, T., Bar-Peled, L., Gebhart, L., Lee, S. G., and Bar-Peled, M. (2009). Identification of galacturonic acid-1-phosphate kinase, a new member of the GHMP kinase superfamily in plants, and comparison with galactose-1-phosphate kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 21526–21535. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.014761

Yang, Y., Kang, L., Wu, R., Chen, Y., and Lu, C. (2020). Genome-wide identification and characterization of UDP-glucose dehydrogenase family genes in moso bamboo and functional analysis of PeUGDH4 in hemicellulose synthesis. Sci. Rep. 10:10124. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-67227-8

Yin, S., Liu, M., and Kong, J. Q. (2016a). Functional analyses of OcRhS1 and OcUER1 involved in UDP-L-rhamnose biosynthesis in Ornithogalum caudatum. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 109, 536–548. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2016.10.029

Yin, S., Sun, Y. J., Liu, M., Li, L. N., and Kong, J. Q. (2016b). CDNA isolation and functional characterization of UDP-d-glucuronic acid 4-epimerase family from Ornithogalum caudatum. Molecules 21:1505. doi: 10.3390/molecules21111505

Yu, Z., He, C., Teixeira da Silva, J. A., Luo, J., Yang, Z., and Duan, J. (2018). The GDP-mannose transporter gene (DoGMT) from Dendrobium officinale is critical for mannan biosynthesis in plant growth and development. Plant Sci. 277, 43–54. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2018.07.021

Zabotina, O. A. (2012). Xyloglucan and its biosynthesis. Front. Plant Sci. 3:134. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2012.00134

Zhang, P., Burel, C., Plasson, C., Kiefer-Meyer, M. C., Ovide, C., Gügi, B., et al. (2019). Characterization of a GDP-Fucose transporter and a fucosyltransferase involved in the fucosylation of glycoproteins in the diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Front. Plant Sci. 10:610. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2019.00610

Zhang, Q., Hrmova, M., Shirley, N. J., Lahnstein, J., and Fincher, G. B. (2006). Gene expression patterns and catalytic properties of UDP-D-glucose 4-epimerases from barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). Biochem. J. 394, 115–124. doi: 10.1042/BJ20051329

Zhang, R., Hu, H., Wang, Y., Hu, Z., Ren, S., Li, J., et al. (2020). A novel rice fragile culm 24 mutant encodes a UDP-glucose epimerase that affects cell wall properties and photosynthesis. J. Exp. Bot. 71, 2956–2969. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eraa044

Zhang, B., Liu, X., Qian, Q., Liu, L., Dong, G., Xiong, G., et al. (2011). Golgi nucleotide sugar transporter modulates cell wall biosynthesis and plant growth in rice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108, 5110–5115. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016144108

Zhao, X., Ebert, B., Zhang, B., Liu, H., Zhang, Y., Zeng, W., et al. (2020a). UDP-Api/UDP-Xyl synthases affect plant development by controlling the content of UDP-Api to regulate the RG-II-borate complex. Plant J. 104, 252–267. doi: 10.1111/tpj.14921

Zhao, X., Liu, N., Shang, N., Zeng, W., Ebert, B., Rautengarten, C., et al. (2018). Three UDP-xylose transporters participate in xylan biosynthesis by conveying cytosolic UDP-xylose into the Golgi lumen in Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot. 69, 1125–1134. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erx448

Zhao, Z., Ren, C., Xie, L., Xing, M., Zhu, C., Jin, R., et al. (2020b). Functional analysis of PpRHM1 and PpRHM2 involved in UDP-l-rhamnose biosynthesis in Prunus persica. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 155, 658–666. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2020.08.011

Zhong, R., Teng, Q., Haghighat, M., Yuan, Y., Furey, S. T., Dasher, R. L., et al. (2017). Cytosol-localized UDP-xylose synthases provide the major source of UDP-xylose for the biosynthesis of xylan and xyloglucan. Plant Cell Physiol. 58, 156–174. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcw179

Keywords: hemicellulose, nucleotide sugar, transporter, biosynthesis, cell wall

Citation: Zhang W, Qin W, Li H and Wu A-m (2021) Biosynthesis and Transport of Nucleotide Sugars for Plant Hemicellulose. Front. Plant Sci. 12:723128. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.723128

Received: 10 June 2021; Accepted: 22 October 2021;

Published: 12 November 2021.

Edited by:

Ajaya K. Biswal, University of Georgia, United StatesReviewed by:

Shiu Cheung Lung, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, ChinaCopyright © 2021 Zhang, Qin, Li and Wu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ai-min Wu, d3VhaW1pbkBzY2F1LmVkdS5jbg==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.