- 1Kihara Institute for Biological Research, Yokohama City University, Yokohama, Japan

- 2Department of Plant and Soil Sciences, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY, United States

Flowering plant zygotes possess complete developmental potency, and the mixture of male and female genetic and cytosolic materials in the zygote is a trigger to initiate embryo development. Plasmogamy, the fusion of the gamete cytoplasms, facilitates the cellular dynamics of the zygote. In the last decade, mutant analyses, live cell imaging-based observations, and direct observations of fertilized egg cells by in vitro fusion of isolated gametes have accelerated our understanding of the post-plasmogamic events in flowering plants including cell wall formation, gamete nuclear migration and fusion, and zygotic cell elongation and asymmetric division. Especially, it has become more evident that paternal parent-of-origin effects, via sperm cytoplasm contents, not only control canonical early zygotic development, but also activate a biparental signaling pathway critical for cell fate determination after the first cell division. Here, we summarize the plasmogamic paternal contributions via the entry of sperm contents during/after fertilization in flowering plants.

Introduction

The fusion of male and female gametes initiates the development of the next generation in sexual reproduction. In flowering plants, two sperm cells are delivered via a pollen tube to a female gametophyte. Each fuses with a female gamete, the egg cell and central cell. These two gamete fusion processes (double fertilization) result in a zygote and a primary endosperm cell, respectively. The zygote develops into an embryo that inherits the genomic information from both parents for the next generation. The primary endosperm cell develops into the endosperm that nourishes the developing embryo or seedling after germination (Dresselhaus et al., 2016).

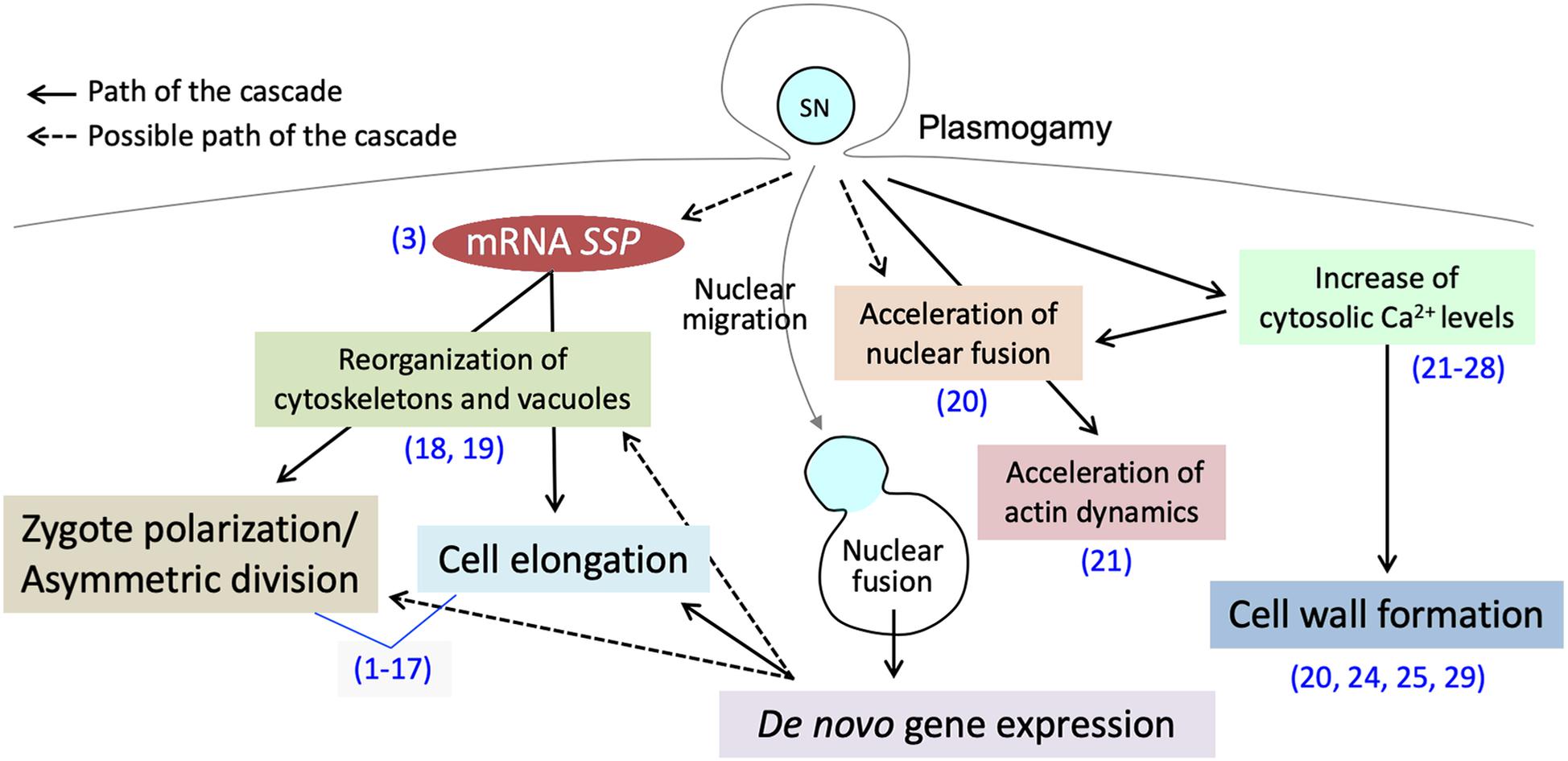

In flowering plants, the cytosolic and genetic mixture, through the cell membrane fusion between the sperm cell and egg cell (plasmogamy) and gamete nuclear migration and fusion (karyogamy), is one of the main transitions of the life cycle (gametophytic-to-sporophytic transition) (Kawashima and Berger, 2014). Although the location of fertilization in flowering plants makes it difficult to observe such events, confocal microscopy live-cell imaging as well as direct investigation of isolated zygotes has successfully revealed intracellular dynamics during early zygote development (Kurihara et al., 2013). Direct investigation of isolated zygotes in monocots (Wang et al., 2006; Kranz and Scholten, 2008), and in eudicots (He et al., 2007; Zhao et al., 2019) is now possible. Furthermore, several in vitro fertilization systems have been established, allowing us further understanding of complex, yet well-orchestrated, early zygotic development (Wang et al., 2006; Kranz and Scholten, 2008; Maryenti et al., 2019). Interestingly, the studies supported by these improved observation techniques have shown much evidence that the sperm cytoplasm contributes to the post-plasmogamic events (Figure 1). In this review, we summarize the plasmogamic paternal contributions to early zygotic development in flowering plants. We also elucidate the relationship between mRNAs carried in from the sperm cell and signaling pathways controlling cell elongation and asymmetric cell division in Arabidopsis zygotes. Epigenetic reprogramming including imprinting is another dynamic process during sexual plant reproduction and reviewed elsewhere (Kawashima and Berger, 2014; Batista and Kohler, 2020).

Figure 1. Post-plasmogamicevents in flowering plant zygotes. Paternal materials brought by the fusion of male andfemale gamete cytoplasms initiate and/or facilitate the post-plasmogamic events in flowering plant zygotes. The numbers in parentheses indicate the reference which describes the step of the pathway; (1) Lukowitz et al., 2004; (2) Wang et al., 2007; (3) Bayer et al., 2009; (4) Ueda et al., 2011; (5) Jeong et al., 2011; (6) Waki et al., 2011; (7) Fiume and Fletcher, 2012; (8) Babu et al., 2013; (9) Costa et al., 2014; (10) Huang et al., 2014; (11) Yu et al., 2016; (12) Ueda et al., 2017; (13) Yuan et al., 2017; (14) Armenta-Medina et al., 2017; (15) Zhang et al., 2017; (16) Neu et al., 2019; (17) Zhao et al., 2019; (18) Kimata et al., 2016; (19) Kimata et al., 2019; (20) Ohnishi et al., 2019; (21) Ohnishi and Okamoto, 2017; (22) Tirlapur et al., 1995; (23) Digonnet et al., 1997; (24) Antoine et al., 2000; (25) Antoine et al., 2001; (26) Hamamura et al., 2014; (27) Denninger et al., 2014; (28) Ponya et al., 2014; (29) Kranz et al., 1995.

Plasmogamic Paternal Contributions Through the Increase of Cytosolic Ca2+ Level by Sperm Entry

In animals, the phospholipase C (PLC) isoform, PLC-zeta (PLCζ), is delivered from the sperm to oocyte, triggering cytosolic Ca2+ oscillations (Saunders et al., 2002; Nomikos et al., 2017). The acute rise of the cytosolic Ca2+ concentration plays important roles in the early zygotic development of most animals, referred to as the “egg activation” or “oocyte activation” (Stricker, 1999). The cytosolic Ca2+ oscillations in mammalian zygotes prevent polyspermy by inducing cortical granule exocytosis. The oscillations then activate calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CAMKII), indirectly triggering meiotic resumption and ultimately leading to the formation of pronuclei and entry into interphase of the first cell cycle (Sanders and Swann, 2016). The activated CAMKII promotes specific maternal mRNA degradation in Drosophila melanogaster zygotes, maternal protein degradation in Xenopus, and the degradation of both in mice (Krauchunas and Wolfner, 2013).

In flowering plants, the transient increase of the cytosolic Ca2+ level in the zygote immediately after sperm entry was visualized by treatment with fluorescent Ca2+ indicators, Fluo-3 AM and Calcium green-1, during maize and rice in vitro fertilization (Digonnet et al., 1997; Antoine et al., 2001; Ohnishi and Okamoto, 2017), and by a Ca+2-selective vibrating electrode during maize in vitro fertilization (Antoine et al., 2000). Using the Ca2+ probes Yellow Cameleon 3.60 or CerTN-L15, fluorescence resonance energy transfer probes of cytosolic Ca2+ that are concentration-dependent indicators, the transient increase of the cytosolic Ca2+ level was also observed in semi in vivo fertilized egg cells in Arabidopsis (Denninger et al., 2014; Hamamura et al., 2014). The increased Ca2+ level in plant zygotes induces cell wall formation (Kranz et al., 1995; Antoine et al., 2000; Ohnishi et al., 2019) and the acceleration of nuclear fusion in rice zygotes (Ohnishi et al., 2019). However, the molecular entities responsible for the increase of the cytosolic Ca2+ level and the molecular mechanisms of how Ca2+ levels control cell wall formation and accelerate the gamete nuclear fusion remain unclear. Further investigations should be performed to dissect the cytosolic Ca2+ increase and cellular dynamics in plant zygotes.

A Possible Plasmogamic Paternal Contribution Enhancing Sperm Nuclear Migration

Although the molecular mechanism is still largely unknown, several factors responsible for filamentous actin (F-actin) dynamics that control sperm nuclear migration in flowering plants have been recently identified (Kawashima et al., 2014; Ohnishi et al., 2014; Ohnishi and Okamoto, 2017; Peng et al., 2017). F-actin, arranged in a network in rice egg cells, continuously converges toward the central egg nucleus and mediates the migration of the sperm nucleus (Ohnishi and Okamoto, 2017). Similar F-actin dynamics were observed in Arabidopsis central cells and primary endosperm cells (Kawashima et al., 2014; Kawashima and Berger, 2015), implying a common mechanism for the distinctive F-actin dynamics between the egg cell and central cell, and also between monocots and eudicots. In the rice zygote, the velocity of F-actin convergence is accelerated after sperm entry, likely supporting rapid sperm nuclear migration (Ohnishi and Okamoto, 2017). The acceleration of F-actin convergence was not observed in isolated egg cells cultured with 5 mM CaCl2 (Ohnishi et al., 2019). This CaCl2 concentration is sufficient to increase the Ca2+ level in the egg cytoplasm, suggesting that the Ca2+ increase by sperm entry itself is not enough to cause the acceleration of F-actin convergence, and there should be an additional, unidentified, pathway controlling this velocity shift. Although the molecular mechanism thereof and its biological significance are not clear, plasmogamic paternal contributions cloud enhance this early zygotic event.

Asymmetric Division and Cell Elongation in Arabidopsis Zygotes

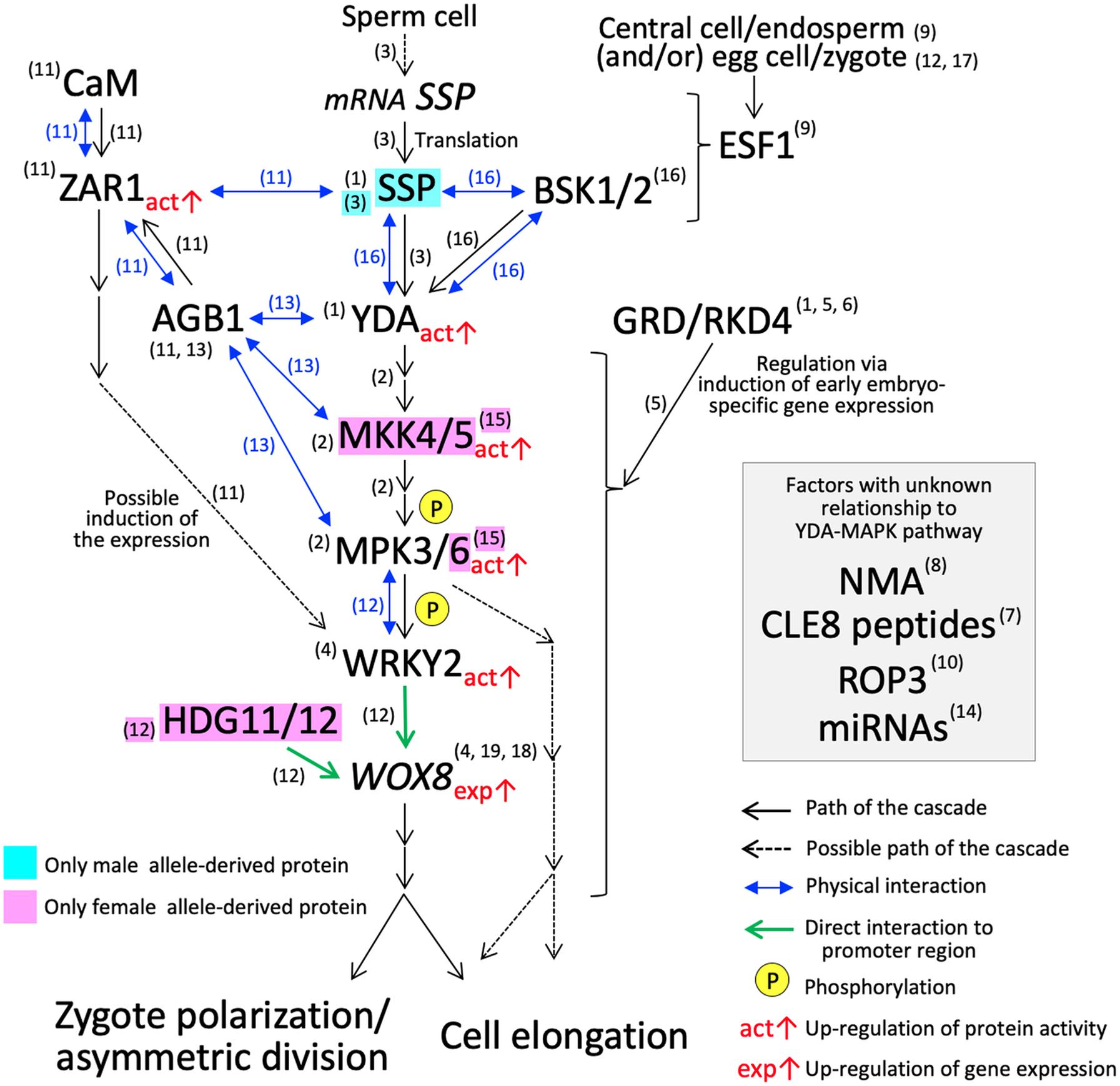

While knowledge is still sparse, several key players controlling cellular polarity that leads to asymmetric division and cell elongation of Arabidopsis zygotes have emerged in the last decade (Figure 2). Asymmetrical division and cell elongation of the zygote is the first hallmark of apical-basal polarity. Signaling through the YODA (YDA) mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase (MAPKKK) cascade sets up the apical-basal polarity in the zygote, promoting basal-cell-lineage (suspensor) differentiation (Lukowitz et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2007). In Arabidopsis zygotes, YDA functions directly or indirectly as an activator of MKK4/MKK5, which subsequently activates MPK3/MPK6 by phosphorylation (Wang et al., 2007; Zhang et al., 2017). The phosphorylated MPK3/MPK6 directly activates WRKY2, a transcription factor, by phosphorylation (Ueda et al., 2017). Thereafter, WRKY2 and transcription factors, HOMEODOMAIN GLABROUS 11/12 (HDG11/12), bind directly to the WUSCHEL RELATED HOMEOBOX 8 (WOX8) intron and activate its transcription in the zygote (Ueda et al., 2017). WOX8 expression continues in the basal daughter cell after the first cell division and persists in the suspensor. Although the direct target genes remain unknown, WOX8 functions as a master regulator of zygote polarization and embryo patterning (Haecker et al., 2004; Breuninger et al., 2008; Ueda et al., 2011).

Figure 2. YDA-MAP cascade responsible for the cell elongation and asymmetric cell division in Arabidopsis zygote. The numbers in parentheses indicate the reference which describes the step of the pathway; (1) Lukowitz et al., 2004; (2) Wang et al., 2007; (3) Bayer et al., 2009; (4) Ueda et al., 2011; (5) Jeong et al., 2011; (6) Waki et al., 2011; (7) Fiume and Fletcher, 2012; (8) Babu et al., 2013; (9) Costa et al., 2014; (10) Huang et al., 2014; (11) Yu et al., 2016; (12) Ueda et al., 2017; (13) Yuan et al., 2017; (14) Armenta-Medina et al., 2017; (15) Zhang et al., 2017; (16) Neu et al., 2019; (17) Bayer et al., 2017; (18) Haecker et al., 2004; (19) Breuninger et al., 2008.

Arabidopsis Gβ protein (AGB1) has a direct physical interaction with MPK3/MPK6, MKK4/MKK5, and YDA, and may function as a scaffold to improve the progression of the YDA-MAPK cascade (Yuan et al., 2017). The physical interaction of AGB1 in vitro and in vivo was also demonstrated with a member of the leucine-rich repeat receptor-like kinase family, ZYGOTIC ARREST 1 (ZAR1) (Yu et al., 2016). ZAR1 also interacts with calmodulin (CaM) at the plasma membrane, and ZAR1 kinase activity is activated by the binding of CaM and/or AGB1 (Yu et al., 2016). The zar1 catalytic (zar1-1) and null (zar1-2) mutations cause asymmetric division arrest and show downregulation and ectopic expression of WRKY2 and WOX8 in early embryo development, respectively, (Yu et al., 2016). These results suggest that ZAR1, possibly activated though a Ca2+ signaling cascade, has an important role in the precise progression of asymmetric division of the zygote and the subsequent embryo development. ZAR1 orchestrates the expression of genes related to the YDA-MAPK cascade. However, the direct/downstream targets remain unclear and additional verifications of this pathway especially physical interactions of factors are awaited.

CLAVATA3/EMBRYO SURROUNDING REGION-RELATED 8 (CLE8), encoding small post translationally modified peptides (Fiume and Fletcher, 2012) and Rho-like small G protein 3 (ROP3) (Huang et al., 2014) also affect WOX8 expression pattern and/or asymmetric division. The direct/downstream targets of these factors, again, remain unknown. EMBRYO SURROUNDING FACTOR 1 (ESF1) peptides, a member of the small cysteine-rich peptide family, were first thought to be expressed specifically in the central cell/endosperm, and may be delivered into the zygote to control upstream the YDA-MAPK cascade (Costa et al., 2014). However, ESF1 transcripts are also present in the egg cell, zygote, and early embryo (Le et al., 2010; Nodine and Bartel, 2012; Slane et al., 2014; Zhao et al., 2019), and the possible involvement of ESF1 expressed from the maternal allele in the egg cell and/or zygote has also been pointed out (Bayer et al., 2017; Ueda et al., 2017). A mutant of NIMNA (NMA), encoding a polygalacturonase, appears to show a strong defect in zygote cell elongation, but not in the asymmetric division (Babu et al., 2013). Likewise, mutants of factors associated with zygote cell elongation and asymmetric division show a diverse range of phenotypes compared to yda, which shows the most severe phenotype (Supplementary Table S1).

Two-photon confocal microscopy, Kimata et al. (2016, 2019) revealed the precise dynamics of F-actin and microtubules in Arabidopsis zygotes. High-resolution observation with cytoskeleton inhibiter treatments indicated that the organization of microtubules plays a major role in zygote elongation (Kimata et al., 2016). For asymmetric division, nuclear positioning toward the apical end of the cell is regulated by longitudinal F-actin along the apical–basal axis and the redistribution and shape of the vacuoles (Kimata et al., 2016, 2019). The structural and kinetic mechanisms of the asymmetric division and cell elongation are gradually being elucidated, leading to further understanding of the roles of previously identified factors as well as their relationships to the YDA-MAPK cascade.

Parent-Of-Origin Effects in Asymmetric Division and Cell Elongation of Arabidopsis Zygotes

In flowering plants, de novo transcripts from both paternal and maternal chromosomes in the zygote are immediately detectable after fertilization (Anderson et al., 2017; Chen et al., 2017; Rahman et al., 2019; Zhao et al., 2019). The inhibition of RNA polymerase II, important for de novo transcription, showed delay or arrest of the cell division of Arabidopsis zygotes (Pillot et al., 2010; Kao and Nodine, 2019; Zhao et al., 2019). Consistently, WOX8 becomes highly expressed after fertilization (Haecker et al., 2004; Breuninger et al., 2008; Ueda et al., 2011). Parallel to the YDA-MAPK cascade, GROUNDED (GRD)/RKD4, an RWP-RK motif-containing transcription factor, activates early embryo-specific genes, which may also be downstream of the YDA-MAPK cascade (Figure 2; Lukowitz et al., 2004; Jeong et al., 2011; Waki et al., 2011). Thus, the de novo gene expression in the zygote is a key biological process, contributing to the subsequent zygotic developmental processes including the asymmetric division and cell elongation.

However, the majority of transcripts found in plant zygote are already present in the egg cell (Anderson et al., 2017; Chen et al., 2017; Zhao et al., 2019), indicating that maternal contribution is also critical for the onset of development (Armenta-Medina and Gillmor, 2019). For example, except MKK5, WOX9, ZAR1, and CLE8, the previously identified factors responsible for the asymmetric division and cell elongation in Arabidopsis are already expressed in the egg cell prior to fertilization (Zhao et al., 2019). In addition, some paternally inherited gene alleles may become activated later than the maternally inherited alleles (Del Toro-De Leon et al., 2014; Baroux and Grossniklaus, 2015; Zhao and Sun, 2015). The reciprocal cross between wild-type and each loss-of-function mutant of MKK4/MKK5 and MPK6 showed only a maternal effect in the asymmetric division and cell elongation (Zhang et al., 2017). HDG11/12 genes expressed in the egg cell or from the maternal allele in the zygote are responsible for their function (Ueda et al., 2017). These findings indicate that maternal contribution is crucial for the YDA-MAPK cascade in Arabidopsis zygote.

On the other hand, transcriptomic analyses among gametes and zygotes also identified a group of genes that are prevalent in the sperm cell and zygote (Anderson et al., 2017; Chen et al., 2017; Rahman et al., 2019), elucidating a possible large-scale transcript carryover from the sperm cell to the zygote. A membrane-associated pseudokinase called SHORT SUSPENSOR (SSP) is known, as a paternal factor, to activate YDA (Bayer et al., 2009). SSP belongs to a recently diverged Brassicaceae-specific member of the BRASSINOSTEROID SIGNALING KINASE (BSK) family (Liu and Adams, 2010). Premature stop (ssp-1) or null (ssp-2) mutations showed symmetric division and arrested cell elongation in the zygote; however, the ssp-2 phenotype in the Colombia-0 ecotype is much weaker than the ssp-1 phenotype and the yda phenotype in the Landsberg erecta ecotype (Supplementary Table S1; Lukowitz et al., 2004; Bayer et al., 2009). Although the BSK family members, BSK1 and BSK2, cannot completely complement the loss of SSP, these may weakly activate the YDA-MAPK cascade in parallel to SSP (Neu et al., 2019). The bsk1;bsk2;ssp triple mutant phenotype, however, is still weaker than that of yda (Neu et al., 2019), indicating another signaling input for the full activation of YDA.

The reciprocal cross between wild-type and ssp showed only a paternal effect (Bayer et al., 2009). Interestingly, SSP transcripts accumulate specifically in sperm cells, but are translationally repressed and SSP protein is transiently produced in the zygote only after fertilization (Bayer et al., 2009). Therefore, SSP transcripts are considered to have been brought in the zygote from the sperm cell via plasmogamy (Musielak and Bayer, 2014; Jeong et al., 2016; Bayer et al., 2017; Armenta-Medina and Gillmor, 2019; Wu and Zheng, 2019). However, the mechanisms of SSP translational repression in sperm cells and the resurgence of the translation of mRNAs carried into the zygote, still remains unclear. In animal cells, many studies of the translational regulation mediated by RNA binding proteins have been conducted (Harvey et al., 2018; Hentze et al., 2018). In plants, recent studies have gradually revealed the role of translational repression mediated by RNA-induced silencing complexes (RISCs) consisting of microRNAs (miRNAs) and ARGONAUTE (AGO) (Hou et al., 2019). AGO1-RISCs in vitro repress translation of the target gene, which contains sequences nearly complementary to the miRNAs (mismatches in the center of the sequence). When this sequence is located at the 5′ UTR or the ORF, translational repression occurs through blocking recruitment or movement of ribosomes (Iwakawa and Tomari, 2013). It is becoming evident that small RNAs accumulate in the pollen (Chambers and Shuai, 2009; Grant-Downton et al., 2009; Slotkin et al., 2009). Transposable element (TE) small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) participate in both post-transcriptional silencing and RNA-directed DNA methylation (Nuthikattu et al., 2013; McCue et al., 2015). They exert an effect on RNA silencing activity in sperm cells during pollen development, suggesting the transportation of TE siRNAs from the pollen vegetative cell to sperm cells (Slotkin et al., 2009; Martinez et al., 2016). Although the function of miRNA biogenesis enzyme DICER-LIKE 1 (DCL1) in zygotic development remains largely unknown and dcl mutants show phenotypic variability, dcl1-7 showed arrested asymmetric division in zygotes (Armenta-Medina et al., 2017). These facts imply that the SSP transcripts should be under translational repression by RISCs, and that repression needs to be released after plasmogamy.

It is unclear whether the translational repression by RISCs in flowering plants is reversible, as reported for stress-induced de-repression in human cells (Bhattacharyya et al., 2006; Gebert and MacRae, 2019). Recently, Mergner et al. (2020) conducted multi-omics analysis composed of the transcriptome, proteome, and phosphoproteome, to each organ of the whole plant in Arabidopsis, and the pollen omics data suggested a low protein-to-mRNA ratio compared to other adult plant tissues. Although it is not yet clear, this low ratio might reflect the hypothesis that the accumulated mRNAs are under translational repression. In rice, a proteome analysis of sperm cells identified approximately 2,000 expressed proteins (Abiko et al., 2013), and a recent rice sperm cell transcriptomic study verified that more than 18,000 genes are transcribed (Rahman et al., 2019). In the maize egg cell, genes encoding proteins for translation are up-regulated (Chen et al., 2017), possibly supporting the active translation of paternally carried-over transcripts in the zygote right after fertilization. Nevertheless, asymmetric division and cell elongation are generated by parent-of-origin effects responsible for the YDA-MAPK cascade and SSP is paternally contributing to it. Future verification will be necessary to reveal whether transcripts other than SSP are under translational repression in sperm cells and to elucidate the significance and mechanism of the paternal translational repression in sexual reproduction and the transport of transcripts via plasmogamy.

Conclusion

The sperm cytoplasm, although significantly reduced, plays a major role in the post-plasmogamic events in the flowering plant zygote. Further investigations of the molecular relationship between Ca2+ and the zygotic events, such as cell wall formation and karyogamy (Kranz et al., 1995; Ohnishi et al., 2019), will reveal what exactly is initiated and/or facilitated by the fluctuation in ion amount caused by sperm entry. On the other hand, the observed acceleration of inward movement of the F-actin meshwork after sperm entry in rice early zygotes appears to be independent from the cytosolic Ca2+ level (Ohnishi et al., 2019). This implies the presence of factors being carried in other than those regulating Ca2+. The YDA-MAP signaling cascade in the Arabidopsis zygote is initially activated by paternal SSP, and the SSP mRNAs are translationally repressed in the sperm cell and delivered into the egg cell (Bayer et al., 2009). Transcripts from the paternal genome are detected in the Arabidopsis zygote (Zhao et al., 2019), and it is not yet clear how many paternally derived transcripts, like SSP mRNA, are brought to the zygote and regulate zygote dynamics and subsequent development. Very recently, Arabidopsis sperm RNA-seq data has been published (Borg et al., 2020). Together with these omics data and fine-scale imaging, in vitro and semi in vivo fertilization systems could reveal plasmogamic paternal contributions to the progress of early zygotic development in flowering plants.

Author Contributions

YO and TK summarized the current investigation and its recent developments in the studies of plant zygotic development, especially plasmogamic paternal contributions via an entry of sperm contents. YO prepared the draft and figures of the mini review. TK summarized and conducted the manuscript preparation and proof trading.

Funding

YO was supported by a research fellowship from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (No. 18J02251). TK was supported by the National Science Foundation (IOS-1928836) and the National Institute of Food and Agriculture, United States Department of Agriculture (Hatch Program-1014280).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Anthony J. Clark for editing the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2020.00871/full#supplementary-material

References

Abiko, M., Furuta, K., Yamauchi, Y., Fujita, C., Taoka, M., Isobe, T., et al. (2013). Identification of proteins enriched in rice egg or sperm cells by single-cell proteomics. PLoS One 8:e69578. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069578

Anderson, S. N., Johnson, C. S., Chesnut, J., Jones, D. S., Khanday, I., Woodhouse, M., et al. (2017). The zygotic transition is initiated in unicellular plant zygotes with asymmetric activation of parental genomes. Dev. Cell 43, 349–358. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2017.10.005

Antoine, A. F., Faure, J. E., Cordeiro, S., Dumas, C., Rougier, M., and Feijo, J. A. (2000). A calcium influx is triggered and propagates in the zygote as a wavefront during in vitro fertilization of flowering plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 10643–10648. doi: 10.1073/pnas.180243697

Antoine, A. F., Faure, J. E., Dumas, C., and Feijo, J. A. (2001). Differential contribution of cytoplasmic Ca2+ and Ca2+ influx to gamete fusion and egg activation in maize. Nat. Cell Biol. 3, 1120–1123. doi: 10.1038/ncb1201-1120

Armenta-Medina, A., and Gillmor, C. S. (2019). Genetic, molecular and parent-of-origin regulation of early embryogenesis in flowering plants. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 131, 497–543. doi: 10.1016/bs.ctdb.2018.11.008

Armenta-Medina, A., Lepe-Soltero, D., Xiang, D., Datla, R., Abreu-Goodger, C., and Gillmor, C. S. (2017). Arabidopsis thaliana miRNAs promote embryo pattern formation beginning in the zygote. Dev. Biol. 431, 145–151. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2017.09.009

Babu, Y., Musielak, T., Henschen, A., and Bayer, M. (2013). Suspensor length determines developmental progression of the embryo in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 162, 1448–1458. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.217166

Baroux, C., and Grossniklaus, U. (2015). The maternal-to-zygotic transition in flowering plants: evidence, mechanisms, and plasticity. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 113, 351–371. doi: 10.1016/bs.ctdb.2015.06.005

Batista, R. A., and Kohler, C. (2020). Genomic imprinting in plants-revisiting existing models. Genes Dev. 34, 24–36. doi: 10.1101/gad.332924.119

Bayer, M., Nawy, T., Giglione, C., Galli, M., Meinnel, T., and Lukowitz, W. (2009). Paternal control of embryonic patterning in Arabidopsis thaliana. Science 323, 1485–1488. doi: 10.1126/science.1167784

Bayer, M., Slane, D., and Jurgens, G. (2017). Early plant embryogenesis-dark ages or dark matter? Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 35, 30–36. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2016.10.004

Bhattacharyya, S. N., Habermacher, R., Martine, U., Closs, E. I., and Filipowicz, W. (2006). Relief of microRNA-mediated translational repression in human cells subjected to stress. Cell 125, 1111–1124. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.04.031

Borg, M., Jacob, Y., Susaki, D., LeBlanc, C., Buendia, D., Axelsson, E., et al. (2020). Targeted reprogramming of H3K27me3 resets epigenetic memory in plant paternal chromatin. Nat. Cell Biol. 22, 621–629. doi: 10.1038/s41556-020-0515-y

Breuninger, H., Rikirsch, E., Hermann, M., Ueda, M., and Laux, T. (2008). Differential expression of WOX genes mediates apical-basal axis formation in the Arabidopsis embryo. Dev. Cell 14, 867–876. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.03.008

Chambers, C., and Shuai, B. (2009). Profiling microRNA expression in Arabidopsis pollen using microRNA array and real-time PCR. BMC Plant Biol. 9:87. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-9-87

Chen, J., Strieder, N., Krohn, N. G., Cyprys, P., Sprunck, S., Engelmann, J. C., et al. (2017). Zygotic genome activation occurs shortly after fertilization in maize. Plant Cell 29, 2106–2125. doi: 10.1105/tpc.17.00099

Costa, L. M., Marshall, E., Tesfaye, M., Silverstein, K. A., Mori, M., Umetsu, Y., et al. (2014). Central cell-derived peptides regulate early embryo patterning in flowering plants. Science 344, 168–172. doi: 10.1126/science.1243005

Del Toro-De Leon, G., Garcia-Aguilar, M., and Gillmor, C. S. (2014). Non-equivalent contributions of maternal and paternal genomes to early plant embryogenesis. Nature 514, 624–627. doi: 10.1038/nature13620

Denninger, P., Bleckmann, A., Lausser, A., Vogler, F., Ott, T., Ehrhardt, D. W., et al. (2014). Male-female communication triggers calcium signatures during fertilization in Arabidopsis. Nat. Commun. 5:4645. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5645

Digonnet, C., Aldon, D., Leduc, N., Dumas, C., and Rougier, M. (1997). First evidence of a calcium transient in flowering plants at fertilization. Development 124, 2867–2874.

Dresselhaus, T., Sprunck, S., and Wessel, G. M. (2016). Fertilization mechanisms in flowering plants. Curr. Biol. 26, R125–R139. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.12.032

Fiume, E., and Fletcher, J. C. (2012). Regulation of Arabidopsis embryo and endosperm development by the polypeptide signaling molecule CLE8. Plant Cell 24, 1000–1012. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.094839

Gebert, L. F. R., and MacRae, I. J. (2019). Regulation of microRNA function in animals. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 20, 21–37. doi: 10.1038/s41580-018-0045-7

Grant-Downton, R., Le Trionnaire, G., Schmid, R., Rodriguez-Enriquez, J., Hafidh, S., Mehdi, S., et al. (2009). MicroRNA and tasiRNA diversity in mature pollen of Arabidopsis thaliana. BMC Genomics 10:643. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-643

Haecker, A., Gross-Hardt, R., Geiges, B., Sarkar, A., Breuninger, H., Herrmann, M., et al. (2004). Expression dynamics of WOX genes mark cell fate decisions during early embryonic patterning in Arabidopsis thaliana. Development 131, 657–668. doi: 10.1242/dev.00963

Hamamura, Y., Nishimaki, M., Takeuchi, H., Geitmann, A., Kurihara, D., and Higashiyama, T. (2014). Live imaging of calcium spikes during double fertilization in Arabidopsis. Nat. Commun. 5:4722. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5722

Harvey, R. F., Smith, T. S., Mulroney, T., Queiroz, R. M. L., Pizzinga, M., Dezi, V., et al. (2018). Trans-acting translational regulatory RNA binding proteins. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 9:e1465. doi: 10.1002/wrna.1465

He, Y. C., He, Y. Q., Qu, L. H., Sun, M. X., and Yang, H. Y. (2007). Tobacco zygotic embryogenesis in vitro: the original cell wall of the zygote is essential for maintenance of cell polarity, the apical-basal axis and typical suspensor formation. Plant J. 49, 515–527. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02970.x

Hentze, M. W., Castello, A., Schwarzl, T., and Preiss, T. (2018). A brave new world of RNA-binding proteins. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 19, 327–341. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2017.130

Hou, J., Lu, D., Mason, A. S., Li, B., Xiao, M., An, S., et al. (2019). Non-coding RNAs and transposable elements in plant genomes: emergence, regulatory mechanisms and roles in plant development and stress responses. Planta 250, 23–40. doi: 10.1007/s00425-019-03166-7

Huang, J. B., Liu, H., Chen, M., Li, X., Wang, M., Yang, Y., et al. (2014). ROP3 GTPase contributes to polar auxin transport and auxin responses and is important for embryogenesis and seedling growth in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 26, 3501–3518. doi: 10.1105/tpc.114.127902

Iwakawa, H. O., and Tomari, Y. (2013). Molecular insights into microRNA-mediated translational repression in plants. Mol. Cell 52, 591–601. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.10.033

Jeong, S., Eilbert, E., Bolbol, A., and Lukowitz, W. (2016). Going mainstream: how is the body axis of plants first initiated in the embryo? Dev. Biol. 419, 78–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2016.05.002

Jeong, S., Palmer, T. M., and Lukowitz, W. (2011). The RWP-RK factor GROUNDED promotes embryonic polarity by facilitating YODA MAP kinase signaling. Curr. Biol. 21, 1268–1276. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.06.049

Kao, P., and Nodine, M. D. (2019). Transcriptional Activation of Arabidopsis zygotes is required for initial cell divisions. Sci. Rep. 9:17159. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-53704-2

Kawashima, T., and Berger, F. (2014). Epigenetic reprogramming in plant sexual reproduction. Nat. Rev. Genet. 15, 613–624. doi: 10.1038/nrg3685

Kawashima, T., and Berger, F. (2015). The central cell nuclear position at the micropylar end is maintained by the balance of F-actin dynamics, but dispensable for karyogamy in Arabidopsis. Plant Reprod. 28, 103–110. doi: 10.1007/s00497-015-0259-1

Kawashima, T., Maruyama, D., Shagirov, M., Li, J., Hamamura, Y., Yelagandula, R., et al. (2014). Dynamic F-actin movement is essential for fertilization in Arabidopsis thaliana. eLife 3:4501. doi: 10.7554/eLife.04501

Kimata, Y., Higaki, T., Kawashima, T., Kurihara, D., Sato, Y., Yamada, T., et al. (2016). Cytoskeleton dynamics control the first asymmetric cell division in Arabidopsis zygote. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, 14157–14162. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1613979113

Kimata, Y., Kato, T., Higaki, T., Kurihara, D., Yamada, T., Segami, S., et al. (2019). Polar vacuolar distribution is essential for accurate asymmetric division of Arabidopsis zygotes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116, 2338–2343. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1814160116

Kranz, E., and Scholten, S. (2008). In vitro fertilization: analysis of early post-fertilization development using cytological and molecular techniques. Sex. Plant Reprod. 21, 67–77. doi: 10.1007/s00497-007-0060-x

Kranz, E., von Wiegen, P., and Lörz, H. (1995). Early cytological events after induction of cell division in egg cells and zygote development following in vitro fertilization with angiosperm gametes. Plant J. 8, 9–23. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1995.08010009.x

Krauchunas, A. R., and Wolfner, M. F. (2013). Molecular changes during egg activation. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 102, 267–292. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-416024-8.00010-6

Kurihara, D., Hamamura, Y., and Higashiyama, T. (2013). Live-cell analysis of plant reproduction: live-cell imaging, optical manipulation, and advanced microscopy technologies. Dev. Growth Differ. 55, 462–473. doi: 10.1111/dgd.12040

Le, B. H., Cheng, C., Bui, A. Q., Wagmaister, J. A., Henry, K. F., Pelletier, J., et al. (2010). Global analysis of gene activity during Arabidopsis seed development and identification of seed-specific transcription factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 8063–8070. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003530107

Liu, S. L., and Adams, K. L. (2010). Dramatic change in function and expression pattern of a gene duplicated by polyploidy created a paternal effect gene in the Brassicaceae. Mol. Biol. Evol. 27, 2817–2828. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msq169

Lukowitz, W., Roeder, A., Parmenter, D., and Somerville, C. (2004). A MAPKK kinase gene regulates extra-embryonic cell fate in Arabidopsis. Cell 116, 109–119. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)01067-5

Martinez, G., Panda, K., Kohler, C., and Slotkin, R. K. (2016). Silencing in sperm cells is directed by RNA movement from the surrounding nurse cell. Nat. Plants 2:16030. doi: 10.1038/nplants.2016.30

Maryenti, T., Kato, N., Ichikawa, M., and Okamoto, T. (2019). Establishment of an in vitro fertilization system in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Plant Cell Physiol. 60, 835–843. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcy250

McCue, A. D., Panda, K., Nuthikattu, S., Choudury, S. G., Thomas, E. N., and Slotkin, R. K. (2015). ARGONAUTE 6 bridges transposable element mRNA-derived siRNAs to the establishment of DNA methylation. EMBO J. 34, 20–35. doi: 10.15252/embj.201489499

Mergner, J., Frejno, M., List, M., Papacek, M., Chen, X., Chaudhary, A., et al. (2020). Mass-spectrometry-based draft of the Arabidopsis proteome. Nature 579, 409–414. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2094-2

Musielak, T. J., and Bayer, M. (2014). YODA signalling in the early Arabidopsis embryo. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 42, 408–412. doi: 10.1042/BST20130230

Neu, A., Eilbert, E., Asseck, L. Y., Slane, D., Henschen, A., Wang, K., et al. (2019). Constitutive signaling activity of a receptor-associated protein links fertilization with embryonic patterning in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116, 5795–5804. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1815866116

Nodine, M. D., and Bartel, D. P. (2012). Maternal and paternal genomes contribute equally to the transcriptome of early plant embryos. Nature 482, 94–97. doi: 10.1038/nature10756

Nomikos, M., Kashir, J., and Lai, F. A. (2017). The role and mechanism of action of sperm PLC-zeta in mammalian fertilisation. Biochem. J. 474, 3659–3673. doi: 10.1042/BCJ20160521

Nuthikattu, S., McCue, A. D., Panda, K., Fultz, D., DeFraia, C., Thomas, E. N., et al. (2013). The initiation of epigenetic silencing of active transposable elements is triggered by RDR6 and 21-22 nucleotide small interfering RNAs. Plant Physiol. 162, 116–131. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.216481

Ohnishi, Y., Hoshino, R., and Okamoto, T. (2014). Dynamics of male and female chromatin during karyogamy in rice zygotes. Plant Physiol. 165, 1533–1543. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.236059

Ohnishi, Y., Kokubu, I., Kinoshita, T., and Okamoto, T. (2019). Sperm entry into the egg cell induces the progression of karyogamy in rice zygotes. Plant Cell Physiol. 60, 1656–1665. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcz077

Ohnishi, Y., and Okamoto, T. (2017). Nuclear migration during karyogamy in rice zygotes is mediated by continuous convergence of actin meshwork toward the egg nucleus. J. Plant Res. 130, 339–348. doi: 10.1007/s10265-016-0892-2

Peng, X., Yan, T., and Sun, M. (2017). The WASP-Arp2/3 complex signal cascade is involved in actin-dependent sperm nuclei migration during double fertilization in tobacco and maize. Sci. Rep. 7:43161. doi: 10.1038/srep43161

Pillot, M., Baroux, C., Vazquez, M. A., Autran, D., Leblanc, O., Vielle-Calzada, J. P., et al. (2010). Embryo and endosperm inherit distinct chromatin and transcriptional states from the female gametes in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 22, 307–320. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.071647

Ponya, Z., Corsi, I., Hoffmann, R., Kovacs, M., Dobosy, A., Kovacs, A. Z., et al. (2014). When isolated at full receptivity, in vitro fertilized wheat (Triticum aestivum, L.) egg cells reveal [Ca2 + ]cyt oscillation of intracellular origin. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 15, 23766–23791. doi: 10.3390/ijms151223766

Rahman, M. H., Toda, E., Kobayashi, M., Kudo, T., Koshimizu, S., Takahara, M., et al. (2019). Expression of genes from paternal alleles in rice zygotes and involvement of OsASGR-BBML1 in initiation of zygotic development. Plant Cell Physiol. 60, 725–737. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcz030

Sanders, J. R., and Swann, K. (2016). Molecular triggers of egg activation at fertilization in mammals. Reproduction 152, R41–R50. doi: 10.1530/REP-16-0123

Saunders, C. M., Larman, M. G., Parrington, J., Cox, L. J., Royse, J., Blayney, L. M., et al. (2002). PLC zeta: a sperm-specific trigger of Ca(2+) oscillations in eggs and embryo development. Development 129, 3533–3544.

Slane, D., Kong, J., Berendzen, K. W., Kilian, J., Henschen, A., Kolb, M., et al. (2014). Cell type-specific transcriptome analysis in the early Arabidopsis thaliana embryo. Development 141, 4831–4840. doi: 10.1242/dev.116459

Slotkin, R. K., Vaughn, M., Borges, F., Tanurdzic, M., Becker, J. D., Feijo, J. A., et al. (2009). Epigenetic reprogramming and small RNA silencing of transposable elements in pollen. Cell 136, 461–472. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.12.038

Stricker, S. A. (1999). Comparative biology of calcium signaling during fertilization and egg activation in animals. Dev. Biol. 211, 157–176. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9340

Tirlapur, U. K., Kranz, E., and Cresti, M. (1995). Characterisation of isolated egg cells, in vitro fusion products and zygotes of Zea mays L. using the technique of image analysis and confocal laser scanning microscopy. Zygote 3, 57–64. doi: 10.1017/s0967199400002380

Ueda, M., Aichinger, E., Gong, W., Groot, E., Verstraeten, I., Vu, L. D., et al. (2017). Transcriptional integration of paternal and maternal factors in the Arabidopsis zygote. Genes Dev. 31, 617–627. doi: 10.1101/gad.292409.116

Ueda, M., Zhang, Z., and Laux, T. (2011). Transcriptional activation of Arabidopsis axis patterning genes WOX8/9 links zygote polarity to embryo development. Dev. Cell 20, 264–270. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.01.009

Waki, T., Hiki, T., Watanabe, R., Hashimoto, T., and Nakajima, K. (2011). The Arabidopsis RWP-RK protein RKD4 triggers gene expression and pattern formation in early embryogenesis. Curr. Biol. 21, 1277–1281. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.07.001

Wang, H., Ngwenyama, N., Liu, Y., Walker, J. C., and Zhang, S. (2007). Stomatal development and patterning are regulated by environmentally responsive mitogen-activated protein kinases in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 19, 63–73. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.048298

Wang, Y. Y., Kuang, A., Russell, S. D., and Tian, H. Q. (2006). In vitro fertilization as a tool for investigating sexual reproduction of angiosperms. Sex. Plant Reprod. 19, 103–115. doi: 10.1007/s00497-006-0029-1

Wu, W., and Zheng, B. (2019). Intercellular delivery of small RNAs in plant gametes. New Phytol. 224, 86–90. doi: 10.1111/nph.15854

Yu, T. Y., Shi, D. Q., Jia, P. F., Tang, J., Li, H. J., Liu, J., et al. (2016). The Arabidopsis Receptor Kinase ZAR1 Is Required for Zygote Asymmetric Division and Its Daughter Cell Fate. PLoS Genet. 12:e1005933. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005933

Yuan, G. L., Li, H. J., and Yang, W. C. (2017). The integration of Gbeta and MAPK signaling cascade in zygote development. Sci. Rep. 7:8732. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-08230-4

Zhang, M., Wu, H., Su, J., Wang, H., Zhu, Q., Liu, Y., et al. (2017). Maternal control of embryogenesis by MPK6 and its upstream MKK4/MKK5 in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 92, 1005–1019. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13737

Zhao, P., and Sun, M. X. (2015). The maternal-to-zygotic transition in higher plants: available approaches, critical limitations, and technical requirements. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 113, 373–398. doi: 10.1016/bs.ctdb.2015.06.006

Keywords: plasmogamy, karyogamy, cell elongation, asymmetric division, paternal parent-of-origin effects

Citation: Ohnishi Y and Kawashima T (2020) Plasmogamic Paternal Contributions to Early Zygotic Development in Flowering Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 11:871. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.00871

Received: 08 April 2020; Accepted: 28 May 2020;

Published: 19 June 2020.

Edited by:

Tzung-Fu Hsieh, North Carolina State University, United StatesReviewed by:

Daphné Autran, Institut de Recherche pour le Développement (IRD), FranceRavishankar Palanivelu, The University of Arizona, United States

Stewart Gillmor, Center for Research and Advanced Studies of the National Polytechnic Institute, Mexico

Copyright © 2020 Ohnishi and Kawashima. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yukinosuke Ohnishi, oonishiy@yokohama-cu.ac.jp; Yukinosuke.Onishi@uky.edu; Tomokazu Kawashima, Tomo.K@uky.edu

Yukinosuke Ohnishi

Yukinosuke Ohnishi