- 1The Key Laboratory of Plant Development and Environmental Adaptation Biology, Ministry of Education, School of Life Science, Shandong University, Qingdao, China

- 2School of Life Science, Guangzhou University, Guangzhou, China

- 3Shandong Provincial Key Laboratory of Plant Stress, Shandong Normal University, Ji’nan, China

- 4Grassland Agri-Husbandry Research Center, Qingdao Agricultural University, Qingdao, China

- 5Institute of Animal Sciences, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Beijing, China

WUSCHEL (WUS) is thought to be required for the establishment of the shoot stem cell niche in Arabidopsis thaliana. HEADLESS (HDL), a gene that encodes a WUS-related homeobox family transcription factor, is thought to be the Medicago truncatula ortholog of the WUS gene. HDL plays conserved roles in shoot apical meristem (SAM) and axillary meristem (AM) maintenance. HDL is also involved in compound leaf morphogenesis in M. truncatula; however, its regulatory mechanism has not yet been explored. Here, the significance of HDL in leaf development was investigated. Unlike WUS in A. thaliana, HDL was transcribed not only in the SAM and AM but also in the leaf. Both the patterning of the compound leaves and the shape of the leaf margin in hdl mutant were abnormal. The transcriptional profile of the gene SLM1, which encodes an auxin efflux carrier, was impaired and the plants’ auxin response was compromised. Further investigations revealed that HDL positively regulated auxin response likely through the recruitment of MtTPL/MtTPRs into the HDL repressor complex. Its participation in auxin-dependent compound leaf morphogenesis is of interest in the context of the functional conservation and neo-functionalization of the products of WUS orthologs.

Introduction

The plant leaf, which varies strongly with respect to both its shape and size, is broadly classified as being either simple or compound. The former, typified by the leaves of the model dicotyledonous species Arabidopsis thaliana, forms a single undivided lamina, the margin of which can be smooth, serrated, or lobed. In contrast, compound leaves are composed of a number of leaflets of variable shape, each attached to the central rachis. Leaves are initiated from the shoot apical meristem (SAM) through a process of founder cell recruitment. The developmental relationship between the SAM and the leaf primordia has been a long-running topic of plant developmental biology (Arber, 1941a; Arber, 1941b; Claßen-Bockhoff, 2001).

The correct initiation of leaf and leaflet primordia and the form of the leaf margin are dependent on localized auxin concentration and PIN1 polarity (Benkova et al., 2003; Barkoulas et al., 2008; Koenig et al., 2009; Bilsborough et al., 2011; Zhou et al., 2011). Any disruption of auxin accumulation imposed by the presence of auxin transport inhibitors or mutations in auxin efflux carrier genes results in the defective development of the leaf/leaflet primordia and typically a simplification in the leaf’s form. In contrast, exogenous auxin treatment can induce ectopic leaflets and outgrowths in the leaf lamina (Barkoulas et al., 2008; Koenig et al., 2009).

Both the establishment and the maintenance of the A. thaliana SAM require the expression of the gene WUSCHEL (WUS), which encodes a transcription factor (Mayer et al., 1998). This enables the specification of the organizing center, a structure that determines the integrity of the stem cell niche and the maintenance of the meristem (Laux et al., 1996; Baurle and Laux, 2005; Sarkar et al., 2007; Dodsworth, 2009; Yadav et al., 2010; Yadav et al., 2011). Mutations in WUS result in the premature termination of both the shoot and the floral meristem (Laux et al., 1996; Mayer et al., 1998; Clark, 2001; Fletcher, 2002; Kieffer et al., 2006; Tanaka et al., 2015). In antirrhinum (Antirrhinum majus), the product of the WUS ortholog ROA also controls the stem cell fate in the SAM, as loss-of-function (LOF) roa mutants form short bushy plants, and the AMs are not maintained (Kieffer et al., 2006). In rice, the WUS ortholog TAB1 (syn. MOC3 or OsWUS) is inactive in both the embryo and the SAM and is not required for SAM formation. However, its presence is necessary for the initiation of the AM and for the development of tillers (Nardmann and Werr, 2006; Lu et al., 2015; Tanaka et al., 2015).

Although the participation of WUS in meristem maintenance in A. thaliana is well understood, the extent to which this function is conserved and/or neo-functionalized by its orthologs has been explored in only a few species. Recently, HEADLESS (HDL), the ortholog of WUS in Medicago truncatula, was identified, which played conserved roles in SAM maintenance (Meng et al., 2019). In this study, we characterized the function of HDL in compound leaf patterning and leaf margin formation. The molecular and genetic evidence suggested that HDL was involved in the maintenance of auxin homeostasis, which is critical for the leaf morphogenesis.

Materials and Methods

Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

M. truncatula ecotype R108 was used for all experiments described in this study. NF11982 (hdl-1; Meng et al., 2019), NF1272 (hdl-4; this study), slm1-1 (Zhou et al., 2011), mtnam-2 (Cheng et al., 2012), mtago7-1 (Zhou et al., 2013), and sgl1-1 (Wang et al., 2008) mutant lines were identified from a Tnt1 retrotransposon-tagged mutant collection of M. truncatula. Plants were grown at 22°C day/20°C night temperature, 16 h day/8 h night photoperiod, and 70% to 80% relative humidity.

Plasmid Construction and Plant Transformation

To generate the HDLpro : GUS construct, a 2366-bp promoter sequence upstream of the HDL start codon was amplified using primer pair HDL-Prom-F/HDL-Prom-R (Table S2) and transferred into the gateway destination vector pBGWFS7 (Karimi et al., 2002) vector for gene expression pattern analysis. All final binary vectors were introduced into the disarmed Agrobacterium tumefaciens EHA105 strain. For stable transformation, leaves of wild-type (WT) were transformed with EHA105 harboring HDL promoter analysis vectors (Crane et al., 2006).

Histology, β-Glucuronidase (GUS) Staining, and Microscopy

The apical shoots of WT and hdl-1 mutant were fixed in 3% glutaraldehyde in a phosphate buffer and then dehydrated and embedded in wax. Samples were sectioned into 10-μm-thick sections using a Leica RM 2255 microtome (Leica) and then stained with toluidine blue-O (Sigma-Aldrich) for observation. For GUS staining analysis, fully expanded leaves were collected. GUS activity was histochemically detected as described previously (Zhou et al., 2011). For scanning electron microscopy (SEM), tissue samples were fixed in 3% (v/v) glutaraldehyde, dissolved in 1× PBS overnight, washed five times in 1× PBS every 10 min, dehydrated in a series of ethanol (30%, 50%, 60%, 70%, 85%, 95%, 100%, and 100% ethanol every 20 min), and then carbon dioxide (CO2) dried and sprayed with gold powder. The samples were observed using Tecnai G2 F20 (FEI, USA) SEM at an accelerating voltage of 15 kV.

In Situ Hybridization Analysis

For RNA in situ hybridization, the probe fragments of 509-bp HDL CDS, 624-bp SLM1 CDS, 498-bp MtTPL CDS, and 556-bp MtTPR1 CDS were polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplified using primers listed in Table S2. The PCR products were cloned into pGEM-T vector (Promega) and then labeled with digoxigenin-11-UTP (Roche). RNA in situ hybridization was performed on vegetative buds of 4-week-old WT or hdl-1 plants as described previously (Zhou et al., 2011).

RNA Extraction and Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR) Analysis

Total RNA from different organs was extracted from 6-week-old plants. Plant materials were fully ground using Tissuelyser-48 (Shanghai Jingxin). Total RNA isolation, cDNA synthesis, and qRT-PCR analysis was performed as described previously (Zhou et al., 2011). The primers used for qRT-PCR analysis are listed in Table S2. For all qRT-PCR analyses, three biological samples were collected.

Phylogenetic Analysis

The protein sequences of HDL and the WUS orthologs and TPL/TPRs were used for phylogenetic analysis. The alignment of multiple protein sequences was performed using CLUSTALW online (http://www.genome.jp/tools/clustalw/). Then, the neighbor-joining phylogenetic trees in the Poisson model were constructed using the MEGA7 software suite (http://www.megasoftware.net/). The phylogenetic trees with bootstrap values from 1,000 replicates were shown.

Yeast Two-Hybrid (Y2H) Assays and BiFC Assay

To test the protein interaction between HDL and MtTPL/MtTPRs family proteins, the CDS of HDL and MtTPL/MtTPRs genes were cloned into the pENTR/D TOPO vector using primers (Table S2) to generate pENTR-HDL and pENTR-MtTPL/MtTPRs, respectively. For bait and prey plasmid constructs, the DBD-MtTPL/MtTPRs and AD-HDL vectors were generated by recombination reaction between pENTR-MtTPL/MtTPRs and pDEST32 and pENTR-HDL and pDEST22. To make the mutation and deletion in WUS domain and EAR motif in HDL, mutation and deletion were introduced into pENTR-HDL using the Fast Mutagenesis System (Transgene) and then transferred into pDEST22. The bait and prey plasmids were cotransformed into yeast MAV203 strain. Yeast transformants were selected on synthetic minimal double dropout medium deficient in Trp and Leu (DDO; Clontech). Medium supplemented with SD-Leu-Trp-His-Ade (quadruple dropout, QDO; Clontech) and 1.5 mM 3-amino-1,2,4 triazole (Sigma) was used for protein interaction tests.

BiFC assays were conducted as described previously (Ou et al., 2011) with some modifications. Briefly, pENTR-HDL and pENTR-HDL-mEAR-mWUS were cloned into gateway vector pEARLEY201-YN and produced destination pEARLEY201-HDL and pEARLEY201-HDL-mEAR-mWUS vectors, whereas pENTR-MtTPL was cloned into gateway vector pEARLEY202-YC and produced destination pEARLEY202-MtTPL. The Agrobacterium GV3101 harboring these constructions was coinfiltrated into 4-week-old Nicotiana benthamiana leaves. After incubation in the dark for 24 h and then in the light for 36 h, the leaves were dissected for observation. For fluorescent imaging, a Leica LSM 780 laser scanning confocal microscope was used. The 488 nm line of an argon laser was chosen for the yellow fluorescent protein signal.

Transient Expression Analysis in Leaves of N. benthamiana

For transient expression analysis, GAL4BD, GAL4BD-HDL, GAL4BD-HDL-ΔEAR, GAL4BD-HDL-ΔWUS, and GAL4BD-HDL-ΔWUS-ΔEAR were amplified from pDEST32 series vector using specific primers (Table S2). The products were cloned into gateway vector pK2GW7 to generate the effector constructs. The reporter and effector plasmids were transformed into Agrobacterium GV3101, and then different effectors were coinfiltrated with the reporter vector 35S-UAS-GUS into 4-week-old N. benthamiana leaves as described previously (Voinnet et al., 2015). After incubation in the dark for 24 h and then in the light for 36 h, the leaves were used for histochemical GUS staining.

Accession Numbers

Sequence data from this article can be found in the Medicago truncatula Genome Project version 4.0 (http://www.medicagogenome.org/search): HDL, Medtr5g021930; SLM1, Medtr7g089360; MtAGO7, Medtr5g042590; STF, Medtr8g107210; SGL1, Medtr3g098560; MtNAM, Medtr2g078700; MtTPL, Medtr4g009840; MtTPR1, Medtr2g104140; MtTPR2, Medtr4g120900; MtTPR3, Medtr1g083700; MtTPR4, Medtr7g112460; and MtTPR5, Medtr4g114980.

Results

HDL Plays Conserved Roles in SAM and AM Maintenance

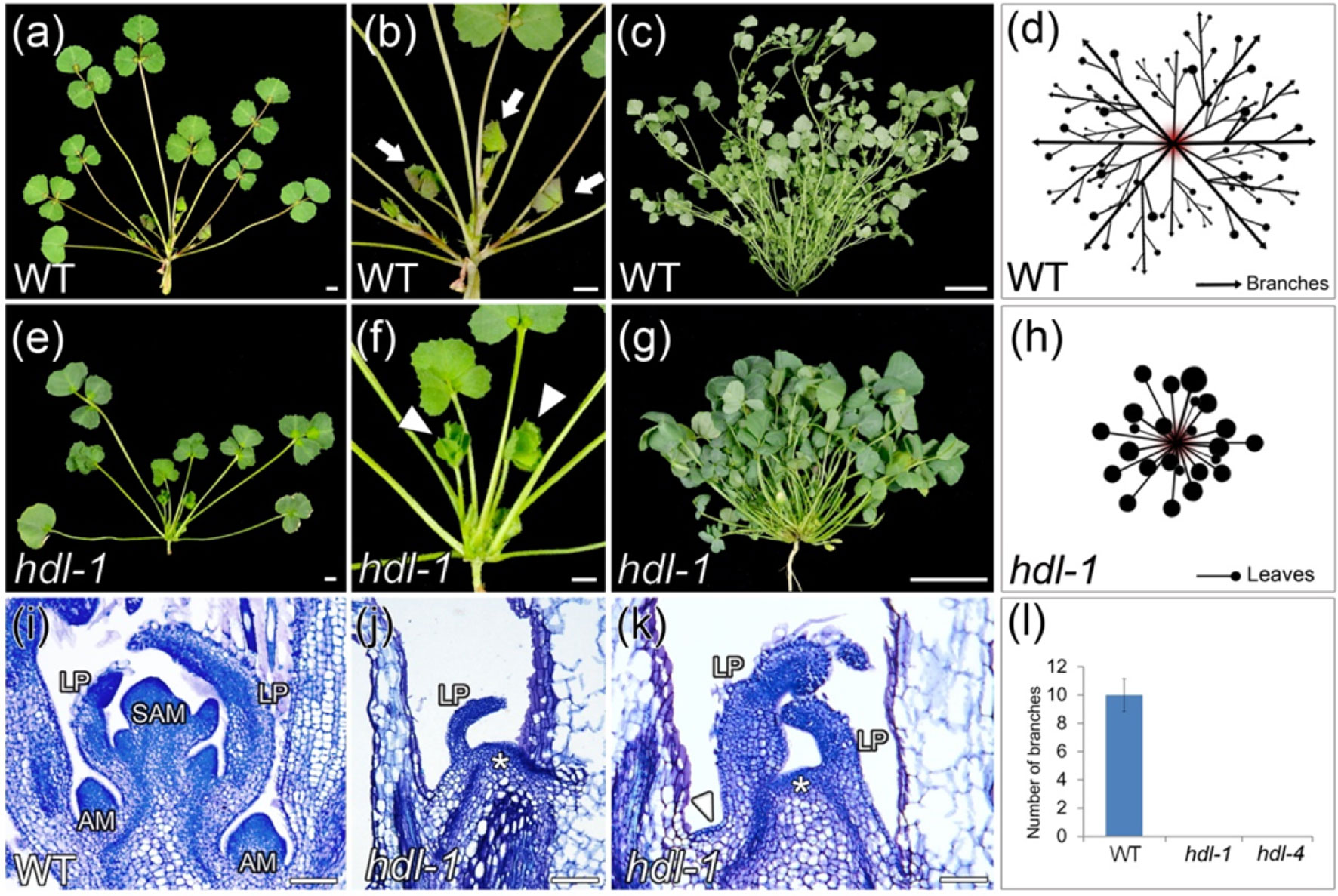

As for the HDL locus, the two mutant lines hdl-1 and hdl-4 were identified (Figure S1). A comparison of the vegetative development between the two lines showed that the developmental defects in hdl-1 and hdl-4 were essentially same. Compared to WT, hdl-1 mutant exhibited an altered plant architecture (Figures 1A–H). Their branchless phenotype was the outcome of the emergence from the SAM of leaves but no branches (Figures 1E–H). The plants of both entries grew slowly, developed a bushy habit, and failed to flower. A comparison of the vegetative buds formed by WT and hdl-1 plants showed that, within the hdl-1 SAM, leaf primordia were initiated abnormally (Figures 1E–K). In addition, AM formation was completely compromised, resulting in a non-branched structure (Figures 1J–L).

Figure 1 hdl-1 mutant of M. truncatula shows defects in the development of branches. (A–D) 4-week-old (A and B) and 9-week-old (C) plants of WT. (B) Close view of the branches in (A). (D) Schematic illustration of the branch arrangement in WT. Arrows indicate branches in (B). (E–H) 4-week-old (E and F) and 9-week-old (G) plants of hdl-1. (F) Close view of the leaves in (E). (H) Schematic illustration of the leaf arrangement in hdl-1. Arrowheads indicate leaves in (F). (I–K) Longitudinal sections of apical shoot buds in WT (I) and hdl-1(J and K). LP, leaflet primordium. Asterisks indicate the flattened structure in the apical position of brl-1. Arrowhead indicates the flattened structure between leaves. (L) Number of branches in 7-week-old plants of WT, hdl-1, and hdl-4. Bar, 5 mm (A, B, E, and F), 5 cm (C and G), and 50 µm (I–K).

HDL Is Required for Compound Leaf Development and Leaf Margin Formation

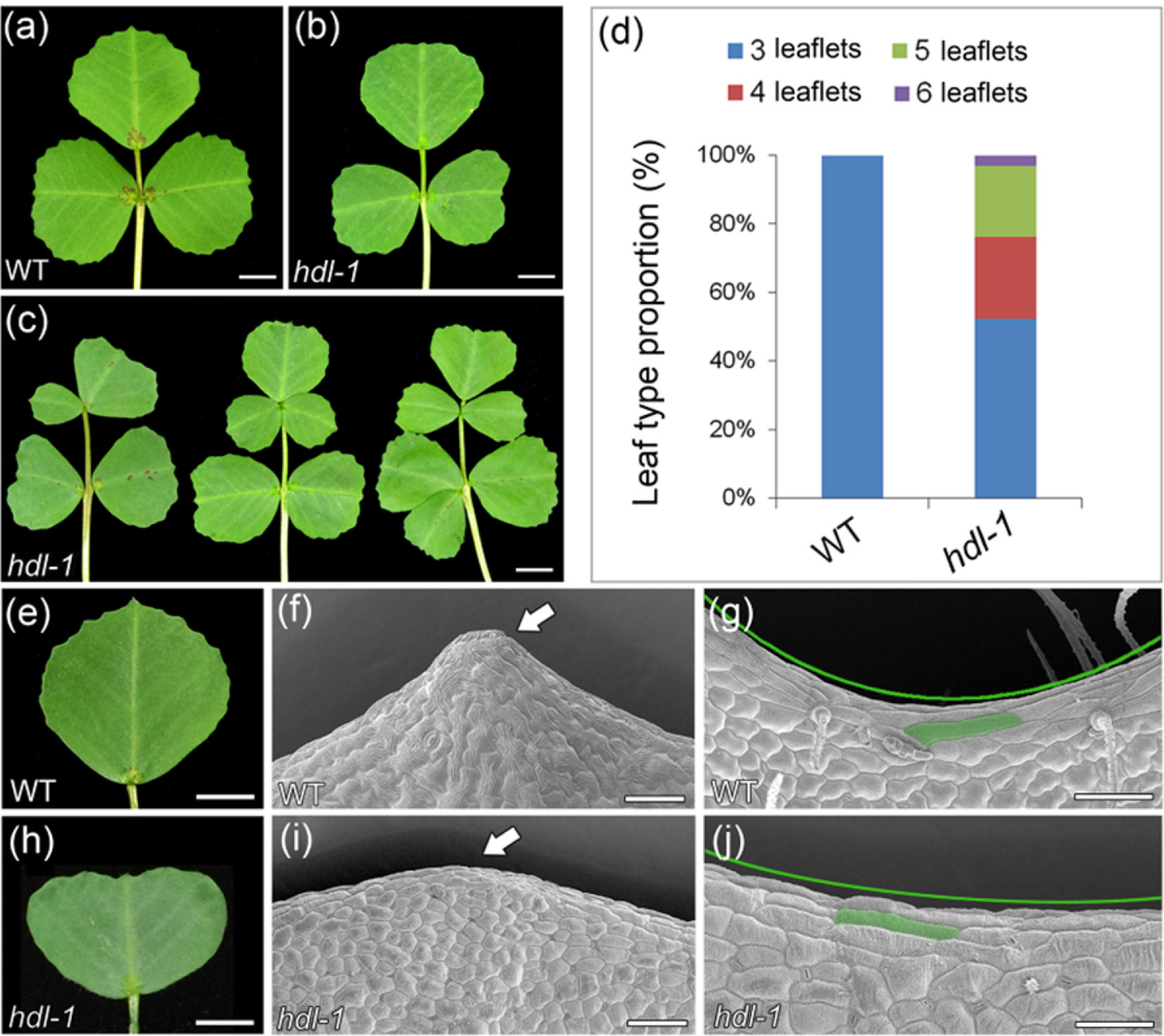

The WT adult leaf is composed of a terminal leaflet plus two lateral leaflets (Figure 2A), a morphology that differed markedly from that of the hdl-1 mutant (Figures 2B, C), in which half of the adult leaves produced between one and three ectopic leaflets (Figure 2D). This altered compound leaf patterning was similar to that shown by the slm1 mutant (Zhou et al., 2011). Whereas WT leaves form a strongly serrated margin (Figures 2E–G), the margin of those formed by the hdl-1 mutant were relatively smooth (Figures 2H–J). Elongated marginal cells were present in both WT and hdl-1 plants (Figures 2G, J), showing that the mutation did not influence their development. Moreover, HDL is also involved in stipule development. The inspection of SEM micrographs showed that leaf primordia were continuously initiated from the periphery of the SAM in WT plants (Wang et al., 2008). At stage 5, a single terminal leaflet primordium, two lateral leaflet primordia, and two stipule primordia were evident, complete with primordial trichomes on the abaxial surface of the leaf primordia (Figure S2a). Leaf primordia could be formed in the mutant, but their development was defective as the formation of stipule and trichomes was delayed (Figure S2b). Moreover, stipule size was reduced in the mutant and its stipule teeth were less sharp compared to that of WT (Figure S2c and d).

Figure 2 hdl-1 mutant of M. truncatula shows defects in leaf development. (A–C) Adult leaves of WT (A) and hdl-1(B and C). Leaflet number is significantly increased in some leaves of hdl-1 mutant (C). Bar, 5 mm. (D) Leaf type proportion in WT (n = 30) and hdl-1 mutant (n = 63). (E–J) Development of leaf margin in WT (E–G) and hdl-1(H–J). Observation of marginal cells at the teeth tips (F and I) and leaf sinus (G and J) in WT and hdl-1 by SEM. Arrows indicate the relatively smooth leaf margin serration in hdl-1(I) compared to WT (F). Green lines indicate the less pronounced sinus in hdl-1(J) compared to WT (G). Representative marginal cells are marked in green color in WT (G) and hdl-1(J). Bar, 5 mm (E and H) and 50 µm (F, G, I, and J).

HDL Is Expressed in Leaf Primordia and Leaf Marginal Serrations

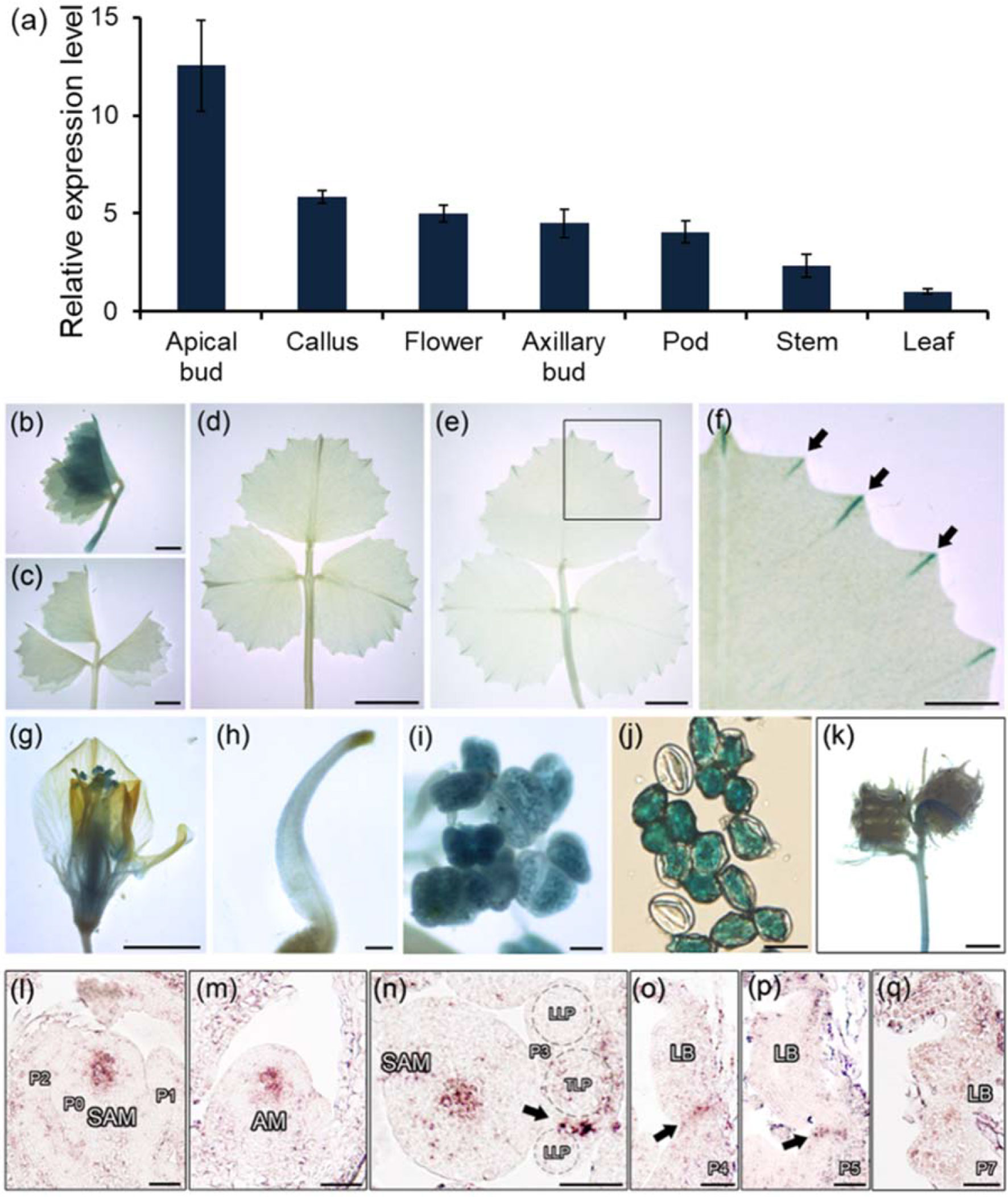

A qRT-PCR assay showed that HDL was strongly transcribed in vegetative shoot buds, axillary buds, flowers, and callus but only at a relatively low level in leaves (Figure 3A). When a transgene comprising the GUS reporter gene driven by the HDL promoter (HDLpro : GUS) was introduced into WT M. truncatula, the strongest levels of GUS activity were observed in the leaf buds (Figure 3B; Figure S4). Although the GUS signal was weak in the leaf lamina as a whole (Figures 3C, D), it was considerable at the tips of the leaf margin serrations during the course of leaf development (Figures 3E, F) as confirmed by qRT-PCR (Figure S5). GUS activity was also observed in the basal portions of flowers, stigmas, anthers, pollen grains, and immature pods (Figure 3G–K). A finer level of spatial and temporal resolution was achieved using RNA in situ hybridization (Figures 3L–Q; Figure S3); this showed that HDL was transcribed abundantly in the central domain of both the SAM and the AM (Figures 3L, M) but not during the early stages (P0, P1, or P2) of leaf primordium development (Figure 3L). Transverse sections taken at the P3 stage confirmed that HDL was transcribed in the junction between the terminal leaflet and the lateral leaflet primordia (Figure 3N). At the P4 and P5 stages, HDL transcription was concentrated in the central region of the leaf primordium (Figures 3O, P), whereas at P7 a low level of transcription was detectable in the leaf margins (Figure 3Q). The conclusion was that HDL likely functions not only in SAM/AM maintenance but also in the process of compound leaf development.

Figure 3 Expression patterns of HDL in M. truncatula. (A) Relative expression level of HDL in different plant organs. Three biological replicates were performed. (B–K) Promoter-GUS fusion studies of HDL expression in transgenic plants. GUS histochemical staining was detected in unexpanded leaf (B and C), fully expanded leaf (D and E), leaf margin serrations (F), flower (G), stigma (H), anther (I), pollen (J), and seed pods (K). (F) Close view of GUS staining of leaf margin (empty box). Arrows indicate the tips of leaf serrations. Bar, 2 mm (B and C), 5 mm (D–G and K), 50 µm (H and I), and 200 µm (J). (L–Q) RNA in situ hybridization analysis of HDL mRNA in WT. Longitudinal and transverse sections of the SAM (L and N), longitudinal section of AM (M), and longitudinal and transverse sections of leaf primordia (N–Q) at different developmental stages were shown. Arrows indicate the signals. P, leaf primordium; TLP, terminal leaflet primordium; LLP, lateral leaflet primordium; LB, leaf blade. Bar, 50 µm.

SLM1 Transcription Differs Between WT and hdl-1 Mutant Plants

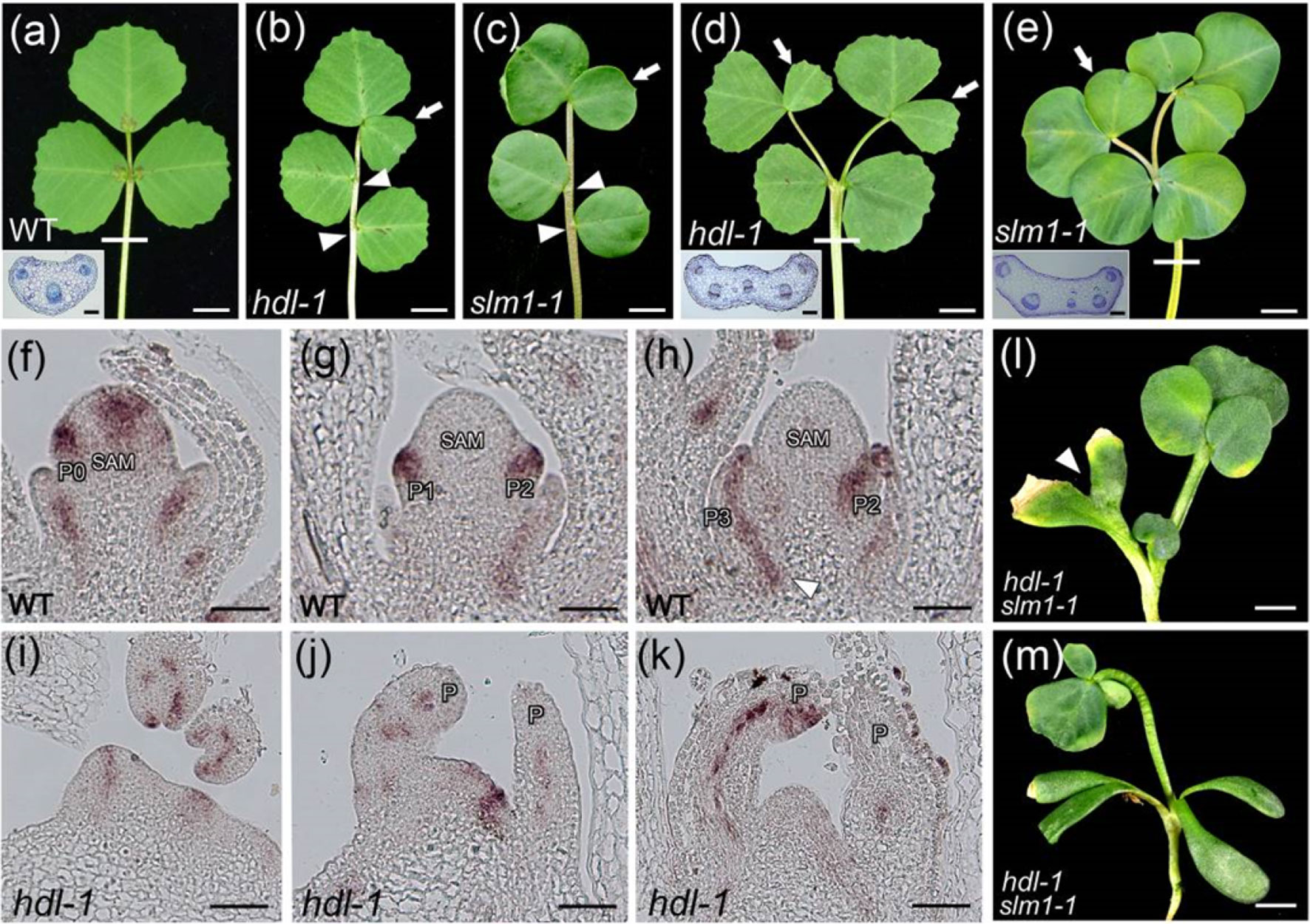

SLM1 is known to encode an auxin efflux carrier protein and is an ortholog of A. thaliana PIN1 (Zhou et al., 2011). The adult leaves of both mutants were similarly defective: in some cases, ectopic leaflets were formed, some of the lateral leaflets were asymmetric, and petioles sometimes appeared fused (Figures 4A–E; Figure S6a). The dimensions (length, width, and length/width ratio) of both the terminal and lateral leaflets formed by the hdl-1 mutant were comparable to those formed by the slm1-1 mutant (Table S1). To test the hypothesis that the defective leaf developmental shown by the hdl-1 mutant involved a disruption in the auxin/SLM1 module, a qRT-PCR-based assay was used to contrast the transcription of SLM1 in WT and hdl-1 plants. This experiment showed that the abundance of transcript generated from SLM1 and other MtPIN genes was unaffected by the HDL mutation (Figure S6b). However, when the comparison was based on RNA in situ hybridization at the early stages of leaf development, it became clear that, in WT plants, SLM1 transcription occurred in the leaf primordia at P0, the developing leaf primordia, and the provascular trace (Figures 4F–H). In hld-1 mutant, the expression level of SLM1 was decreased, especially in SAM and leaf primordia at P0 (Figure 4I). The expression of SLM1 in leaf primordia was disturbed in some cases (Figures 4J–K). Plants of the double mutant hdl-1 slm1-1 were weak and dwarfed and featured both ectopic and fused cotyledons, and the small number of leaves they developed exhibited clustered leaflets (Figures 4L, M; Figure S7). The suggestion was that HDL and SLM1 act synergistically during leaf initiation and compound leaf patterning.

Figure 4 Developmental defects in hdl resemble those in slm1. (A–C) Compared to WT (A), hdl-1 (B) and slm1-1 (C) mutants exhibit similar defects of leaf pattern. Arrowheads indicate asymmetric lateral leaflets. Arrows indicate ectopic terminal leaflets. Transverse section of petiole in WT is shown in the inset (A). The sectioning region is shown by white line. Bar, 5 mm. (D and E) Petiole fusion can be observed in both hdl-1 (D) and slm1-1 (E). Transverse sections of petioles in hdl-1 (D) and slm1-1 (E) are shown in the insets. White lines indicate sectioning regions. Arrows indicate ectopic terminal leaflets. Bar, 5 mm. (F–K) RNA in situ hybridization analysis of SLM1 mRNA in the longitudinal sections of the SAM in WT (F–H) and hdl-1 (I–K). Arrowhead indicates provascular trace in (H). Bar, 50 µm. (L and M) Phenotype of hdl-1 slm1-1 double mutant. Arrowhead indicates fused cotyledons in (L). Note that quadruple cotyledons are developed in double mutant (M). Bar, 5 mm.

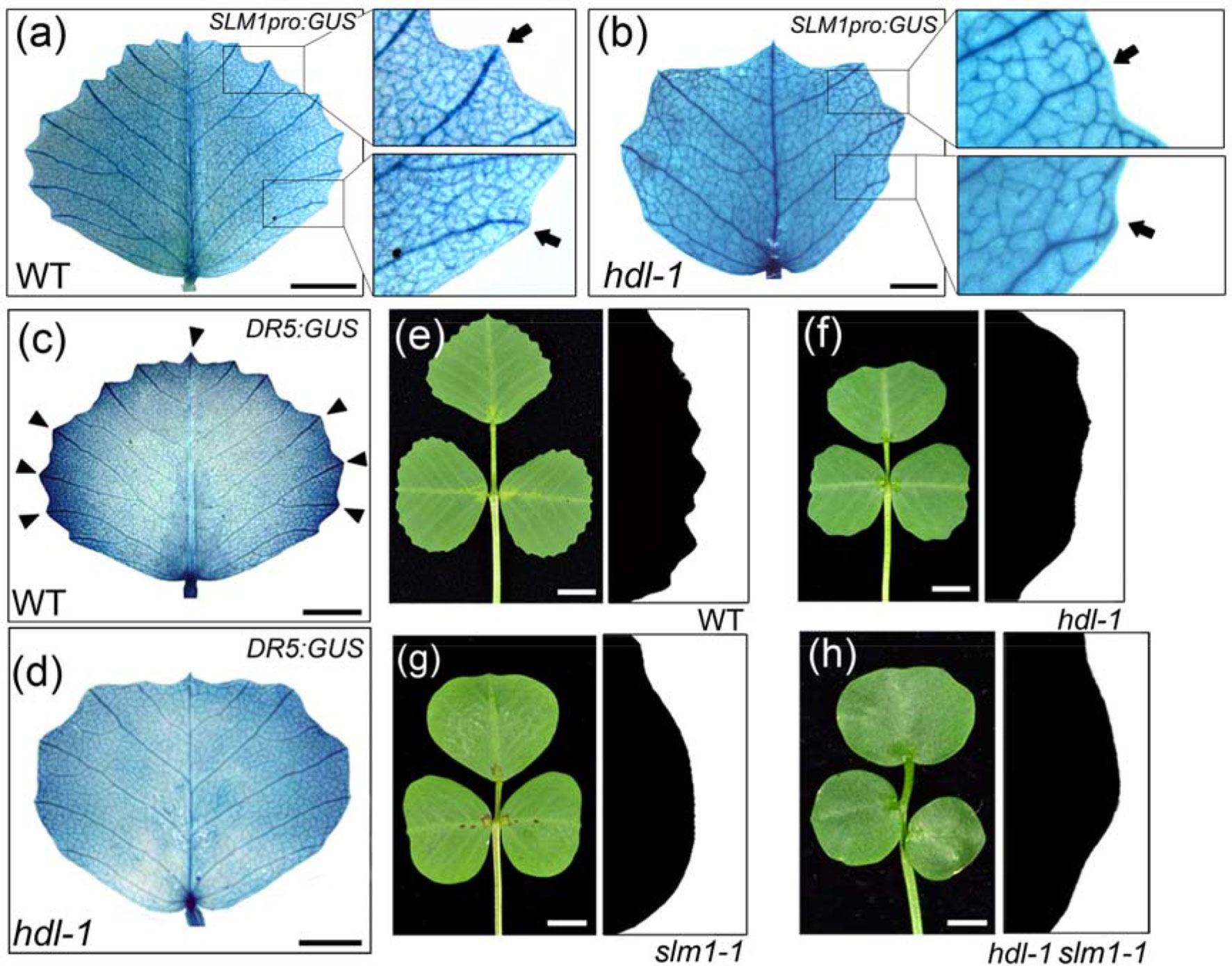

LOF of HDL Compromises the Auxin Response During the Formation of the Leaf Margin

It is known that the auxin/SLM1 module is a determinant of leaf margin development through its generation of local auxin activity gradients (Zhou et al., 2013). When a transgene comprising GUS driven by the native SLM1 promoter (SLM1pro:GUS; Zhou et al., 2011) was introduced into a WT background, the resulting pattern of GUS activity revealed that the promoter activity was concentrated in the vasculature associated with serrations (Figure 5A). However, in hdl-1 mutants carrying SLM1pro:GUS, reporter gene expression was detected in free-ending veins developed at the distal end of lateral veins (Figure 5B). These observations implied an alteration in auxin accumulation along the leaf margin as mediated by SLM1. To contrast the auxin responsiveness of WT and hdl-1 mutant plants, the DR5:GUS transgenes (Zhou et al., 2011) were introduced respectively into both backgrounds. The observation was that GUS activity was decreased along the leaf margin, which was taken to imply that auxin responsiveness was repressed in the hdl-1 mutant (Figures 5C, D). Like the leaves of the slm1-1 mutant (Zhou et al., 2011), those formed by the hdl-1/slm1-1 double mutant lacked marginal serration (Figures 5E–H), which suggested that HDL regulates leaf margin formation in an auxin/SLM1-dependent manner.

Figure 5 LOF of HDL results in the repression of auxin response in leaf margin formation. (A and B) Expression pattern of SLM1 in fully expanded leaflet of WT (A) and hdl-1 (B) as determined by the detection of SLM1pro:GUS activity. Close views of leaf margin serrations are shown in empty boxes. Arrows indicate lateral veins, which terminate at the marginal serrations in WT (A) but not in hdl-1 (B). Bar, 5 mm. (C and D)DR5:GUS expression in the fully expanded terminal leaflet of WT (C) and hdl-1 (D). Arrowheads mark auxin accumulation at the tip of serrations. Bar, 5 mm. (E–H) Leaf margin phenotype of WT (E), hdl-1 (F), slm1-1 (G), and hdl-1 slm1-1 (H). Bar, 5 mm.

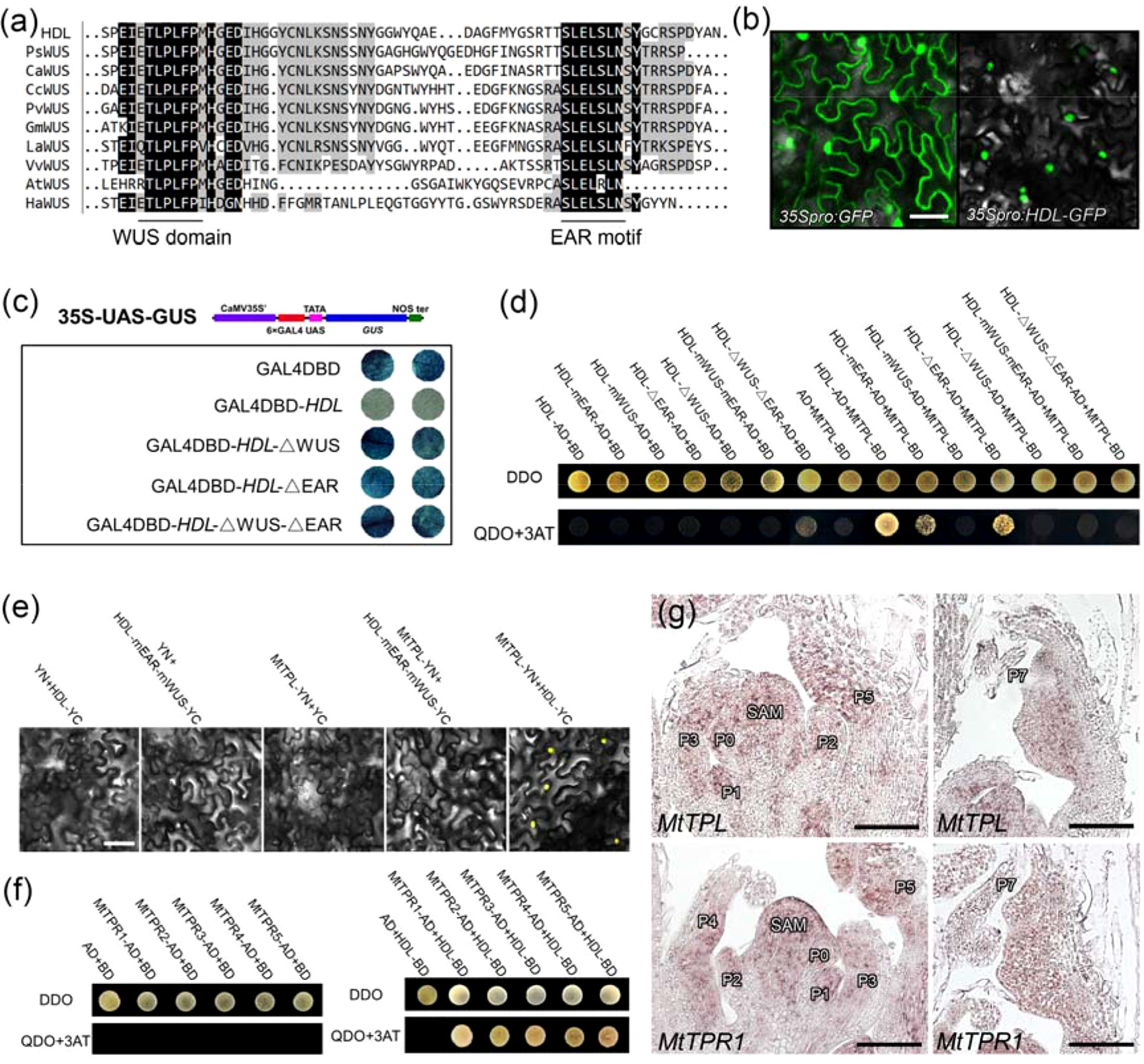

HDL Mainly Acts as a Transcriptional Repressor

HDL encoded a protein of 302 amino acids that contained a homeodomain (residues 28–96) in the N-terminal region, a WUS domain (ETLPLFPM; between residues 240 and 247), and an EAR motif (SLELSLN; residues 285–291) in the C-terminal region (Figure 6A; Figure S8), suggesting that HDL may function as a transcriptional repressor. To verify this hypothesis, the construct 35S:HDL-GFP was transiently expressed in tobacco leaves. The HDL-GFP fusion protein was localized to the nucleus (Figure 6B), supporting its roles as a putative transcription factor. To determine the possible transcriptional activity, a reporter construct 35S-UAS-GUS was generated. The GUS gene was driven by a synthetic promoter that contained six copies of GAL4 binding site (6×UAS) driven by a CaMV 35S promoter. Then, HDL was fused with the GAL4 DNA-binding domain (DBD) to generate GAL4DBD-HDL, which was cotransformed with 35S-UAS-GUS into tobacco leaves (Figure 6C). Compared to control (GAL4DBD), the GUS staining signal was severely attenuated when 35S-UAS-GUS was cotransformed with GAL4DBD-HDL (Figure 6C), supporting that HDL is a transcriptional repressor. To test whether the WUS domain and EAR motif in HDL were responsible for the repression activity of HDL, the HDL-ΔWUS (WUS domain deleted), HDL-ΔEAR (EAR motif deleted), and HDL-ΔWUS-ΔEAR (both WUS domain and EAR motif deleted) were fused with the GAL4 DBD and cotransformed with 35S-UAS-GUS, respectively. The results showed that these constructs could not repress GUS expression, compared to GAL4DBD-HDL (Figure 6C), indicating that both WUS domain and EAR motif are required for the repression activities of HDL.

Figure 6 Physically interaction between HDL and MtTPL/MtTPRs. (A) Multiple amino acid sequence alignment of the C-terminal region containing WUS domain and EAR motif in different species.(B) Subcellular protein localization of HDL. HDL was localized in the nucleus. Free GFP as a control. Bar, 50 µm. (C) HDL mainly acts as a transcriptional repressor. The transcription activity of HDL was tested in tobacco leaves using a GAL4/UAS-based system. (D) WUS domain and EAR motif are required for interaction between HDL and MtTPL. Interaction was examined by yeast growth on QDO (SD-Leu-Trp-His-Ade) medium. Data are representative of three replicates. (E) BiFC showing the interaction between HDL and MtTPL in tobacco cells. Interaction between HDL-mEAR-mWUS and MtTPL is absent. (F) HDL interacts with all the MtTPR proteins. (G) Expression patterns of MtTPL and MtTPR1 in WT. Longitudinal sections of SAM and leaf primordia are shown. Bar, 50 µm.

HDL Physically Interacts With the MtTPL Protein via Its WUS Domain and EAR Motif

It has been shown that WUS interacts with the two members of the TPL/TPR family of corepressors to function as a repressor (Kieffer et al., 2006; Causier et al., 2012). Phylogenetic analysis showed that there is one TPL (MtTPL) protein and five TPR (MtTPR1-5) proteins in M. truncatula (Figure S9). To understand the potential regulatory mechanism of HDL, we performed Y2H assay to examine the interaction between HDL and MtTPL. The results showed that HDL could interact with MtTPL in vitro (Figure 6D). As HDL protein contained WUS domain and EAR motif, we next test which domain and motif in HDL are responsible for the interaction with MtTPL. The interaction was completely abolished by the mutation of two Leu residues in the WUS domain (HDL-mWUS) or the deletion of WUS domain (HDL-ΔWUS; Figure 6D), indicating that the WUS domain is likely to be important for the interaction between HDL and MtTPL. The mutation of two Leu residues in EAR motif (HDL-mEAR) or the deletion of EAR motif (HDL-ΔEAR) somewhat reduced its interaction with MtTPL (Figure 6D), suggesting that the EAR motif is essential for the interaction with MtTPL. Furthermore, the combined mutation or deletion in both the WUS domain and the EAR motif in HDL also abolished the interaction with MtTPL (Figure 6D), which was confirmed by BiFC assay (Figure 6E). In addition, HDL could interact with all of the five MtTPR proteins (Figure 6F). To investigate whether HDL functions with MtTPL/MtTPR in leaves, spatial localization of MtTPL/MtTPR1 was detected by in situ hybridization. The results showed that MtTPL and MtTPR1 were expressed not only in SAM but also in young and old leaf primordia (Figure 6G), which overlapped with the expression domain of HDL. Taken together, these data demonstrate that HDL functions as a transcriptional repressor by recruiting the MtTPL/MtTPRs to form the complex for developmental regulation.

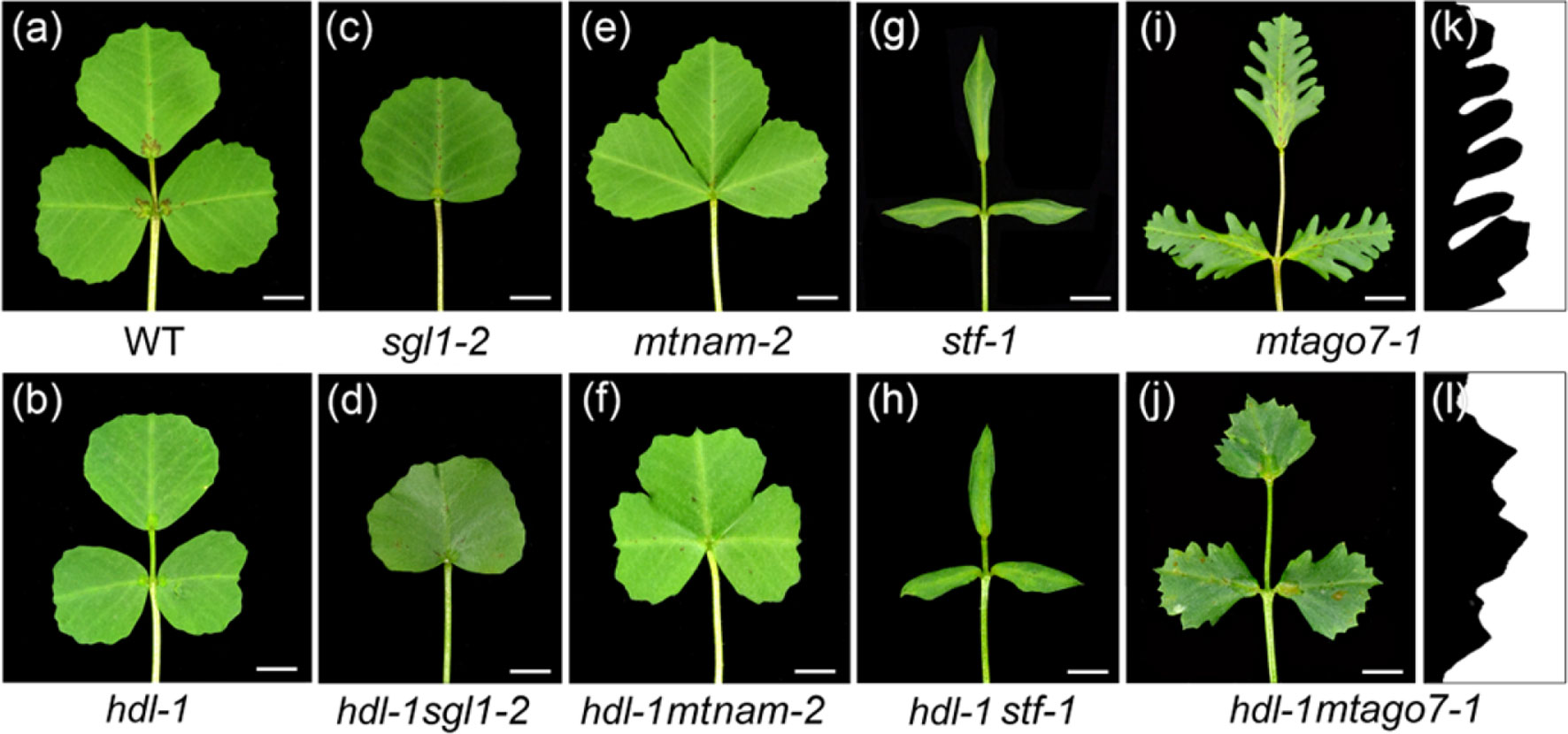

Genetic Interactions Between HDL and Other Genes Responsible for Leaf Development

To investigate the possible role of HDL in leaf patterning, the hdl-1 mutant was crossed with the leaf pattern mutants. SGL1 is the M. truncatula ortholog of pea UNIFOLIATE; the adult leaves of LOF sgl1 mutants are simple rather than compound (Wang et al., 2008). Double hdl-1 sgl1-2mutant plants also formed simple leaves (Figures 7A–D), indicating that the LOF of HDL had no effect on leaf form if SGL1 is disabled. The product of MtNAM (a member of the angiosperm NAM/CUC gene family) is involved in the development of lateral organ boundaries (Cheng et al., 2012). The salved offspring of an mtnam-2/+ heterozygote included around a quarter (presumed mutant homozygotes) in which the cotyledons were fused together. When a population of 385 salved offspring of the double heterozygote mtnam-2/+/hdl-1/+ was screened, only one double-mutant homozygote was recovered probably due to the embryo lethal (Figure S10). All of its leaves featured fused leaflets (Figures 7E, F), showing that the LOF of HDL had no effect on lateral organ formation if MtNAM is disabled. Thus, although HDL is clearly involved in compound leaf patterning, this function appears to depend on the presence of both SGL1 and MtNAM. To further investigate the potential genetic interactions between HDL and the gene related to leaf margin development, the hdl-1 mutant was crossed with the stf-1 and mtago7-1 mutants, respectively (Figures 7G–L). STF is a member of the WUS-related homeobox (WOX) family of transcription factors and acts to promote cell proliferation at the adaxial-abaxial junction; plants carrying the stf mutation develop narrow leaves lacking marginal serration (Tadege et al., 2011). The hdl-1 stf-1 double mutant produced a similar, narrowed leaf (Figures 7G, H). LOF mutants for MtAGO7, an ortholog of AtAGO7, produce lobed leaves (Zhou et al., 2013). The margins of the leaves developed by the double mutant hdl-1 mtago7-1 were less indented than those of the mtago7-1 mutant (Figures 7I–L), indicating that the TAS3 ta-siRNA/AGO7 pathway acts antagonistically with HDL in elaborating leaf margin serration.

Figure 7 Genetic interactions between hdl and different leaf pattern mutants. (A–J) Leaf phenotype of WT (A), hdl-1 (B), sgl1-2 (C), hdl-1 sgl1-2 (D), mtnam-2 (E), hdl-1 mtnam-2 (F), stf-1 (G), hdl-1 stf-1 (H), mtago7-1 (I), and hdl-1 mtago7-1 (J). Bar, 5 mm. (K and L) Leaf margin phenotype of mtago7-1 (K) and hdl-1 mtago7-1 (L).

Discussion

Conservation and Specialization Roles of WUS Orthologs Among Different Plant Species

The products of WUS and of its orthologs in both antirrhinum (ROA) and petunia (TER) all exert a major influence on the maintenance of the SAM and the AM (Laux et al., 1996; Mayer et al., 1998; Hamada et al., 2000; Stuurman et al., 2002; Kieffer et al., 2006). However, there are species differences with respect to their effect on the shoot and floral meristem and on leaf morphology. In A. thaliana, wus mutants are unable to form a viable shoot meristem in the developing embryo (Laux et al., 1996; Mayer et al., 1998), the appearance of the first rosette leaf is markedly delayed (Hamada et al., 2000), no juvenile leaves are formed (Hamada et al., 2000), and the floral meristem is terminated prematurely to create a central stamen (Laux et al., 1996; Mayer et al., 1998). Shoot development in petunia ter mutants is terminated after the two first true leaves have been produced; in the rare cases where plants flower, fewer floral organs are formed than normal (Stuurman et al., 2002). Finally, in antirrhinum roa mutants, the initiation of the SAM appears normal, but its maintenance is compromised, and the plants do not flower (Kieffer et al., 2006). The effect of the LOF of HDL was to disrupt the development of the shoot meristem, and there was no transition into reproductive growth. As it is also the case for mutants harboring LOF alleles of WUS and its orthologs, the AM of hdl mutants was defective, resulting in the failure to form branches.

Expression pattern diversity in key domains is an important driver of functional specialization. Some variations in the transcriptional profile of WUS and its orthologs have been noted, especially between dicotyledonous and monocotyledonous species. WUS is active in both the SAM and the developing embryo of A. thaliana (Mayer et al., 1998); in antirrhinum, ROA is transcribed in the vegetative apex, inflorescences, and young floral meristems (Kieffer et al., 2006); in petunia, TER has a similar transcriptional profile to WUS at least in the vegetative apex (Stuurman et al., 2002). Both wus and ter mutants produce only leaves, with the result that they form bushy plants. In contrast, the rice gene TAB1 is active in emerging AMs, but its transcript cannot be detected in established SAMs (Lu et al., 2015; Tanaka et al., 2015). The tab1 mutant is unable to form tillers, but the plant is not compromised with respect to leaf development; this has been taken to suggest that TAB1 is involved in the initiation of AMs but not in SAM maintenance (Tanaka et al., 2015). Although no wus-type mutant has yet to be described in maize, the transcriptional behavior of the two related genes ZmWUS1 and ZmWUS2 was fine-tuned by specific signal (Nardmann and Werr, 2006; Je et al., 2016). The M. truncatula HDL gene is active in both the SAM and the AM, and the developmental defects with respect to both the SAM and the AM associated with its LOF are comparable to those expressed in both wus and roa mutants. Unlike the latter, however, and more akin to the phenotype of the rice tab1 mutant, hdl mutant plants were able to produce a number of leaves; the implication is that, in M. truncatula, SAM functionality is only partially compromised in the hdl SAM, suggesting some possible genetic redundancy between HDL and the products of other WOX genes. HDL was successfully detected in the leaf and the development of the leaf margin was defective in plants of genotype hdl. The species differences in the transcriptional behavior of WUS and its orthologs imply that these genes have experienced some neo-functionalization over the course of evolution. Overall, their functional conservation appears to have been stronger in the context of AM than of SAM growth, development, and maintenance.

HDL Plays a Role With MtTPL/MtTPRs at the Protein Level

WUS acts as a repressor by recruiting the corepressor TPL (Kieffer et al., 2006; Ikeda et al., 2009). TPL and TPRs are members of Gro/Tup1 family corepressors that are complicated in a wide range of processes by directly or indirectly interacting with repressive transcription factors to repress the expression of downstream target genes (Liu and Karmarkar, 2008; Causier et al., 2012). Mutation of the WUS domain and the EAR motif interferes with the repressive activity of WUS (Kieffer et al., 2006; Ikeda et al., 2009). In addition, the LOF of the WUS-TPL interaction impairs WUS function, suggesting that the recruitment of TPL in SAM is a general mechanism to repress differentiation-promoting genes in stem cells (Kieffer et al., 2006; Causier et al., 2012). In this study, deletion of each of the WUS domain and the EAR motif or both significantly blocks the repressive activity of HDL. Thus, HDL acts mainly as a transcriptional repressor that depends on its WUS domain and EAR motif. HDL also interacts with MtTPL, and such interaction is completely abolished by the mutation or deletion of the WUS domain. Moreover, the mutation or deletion of the EAR motif reduces the intensity of their interaction. Therefore, the WUS domain and the EAR motif in HDL cooperate to recruit the MtTPL into the HDL repressor complex. Besides, HDL also interacts with all of the five MtTPRs in M. truncatula, suggesting a complex regulatory interaction between HDL and MtTPL/MtTPRs. It has been reported that WOX family members, STF and LFL, interact with different members of the transcriptional corepressor MtTPL/MtTPRs and are involved in M. trunctula compound leaf and flower development as the transcriptional repressor (Zhang et al., 2014; Niu et al., 2015). STF is expressed at the adaxial-abaxial layer in leaf primordia and LFL is expressed in the emerging petals and sepals. In contrast, HDL is expressed in SAM and leaf primordia. It is possible that the diverse biological functions of the WOX-MtTPL/MtTPRs complexes on M. trunctula development largely depend on the expression pattern or function of WOX, whereas MtTPL/MtTPRs only act as a partner or mediator.

HDL Is Involved in Regulation of Auxin Response in Compound Leaf Morphogenesis

Plant hormones are an important regulatory component of meristem cell maintenance and differentiation. The LOF of HDL generated a number of abnormalities in leaf morphology, including an altered structure of the compound leaf and a different appearance of the leaf margin, which are changes that resemble those induced by the LOF of SLM1. Previously, it has been shown that leaf development is influenced by SLM1-mediated auxin distribution (Zhou et al., 2011). The transcriptional profile of SLM1 in the flattened structure at the stem apex produced by the hdl mutant mirrors the phenotypic similarity between the hdl and slm1 mutants, although the severity of the leaf developmental defects present in hdl-1 mutants was not as great as in the slm1 mutant. By implication, these defects likely arose, at least in part, from a disordering of SLM1-dependent auxin gradients. The product of STF is known to regulate leaf growth through its control over auxin levels (Tadege et al., 2011). The behavior of hdl-1 stf-1 double mutants supports the proposition that auxin is involved in leaf formation. Given that the margin of the leaves formed by the stf mutant is smooth and that stf is genetically epistatic to hdl in leaf margin formation, it is plausible to suggest that the defects in leaf development displayed by hdl mutant plants are related to problems in maintaining auxin homeostasis.

Some functional diversification of WOX genes has been observed in cross-species comparisons. In A. thaliana, SAM maintenance is regulated by WUS, whereas WOX4 is not transcribed in the SAM. However, in rice, WOX4 is transcribed in both the meristem and leaf primordia, so its product is likely involved in maintaining the meristem and regulating leaf development (Ohmori et al., 2013; Yasui et al., 2018). However, the product of the WUS ortholog TAB1 participates in AM formation but not in SAM maintenance. Overall, the present data have provided novel information regarding the function of the WUS ortholog in compound leaf morphogenesis in M. truncatula, which underlines how the WUS gene family has diversified during the course of speciation.

Conclusion

In this paper, we reported the studies of the regulatory mechanism of HDL in compound leaf morphogenesis in M. truncatula. HDL is the ortholog of A. thaliana WUS and plays conserved roles in the maintenance of SAM and AM. LOF in HDL results not only in the compromised SAM and AM but also in the altered compound leaf patterning and leaf margin formation. Based on the molecular and genetic evidence, we find that the expression pattern of SLM1/PIN1, which regulates auxin activity gradients, was impaired. Moreover, HDL positively regulates auxin response in leaves through the recruitment of MtTPL/MtTPRs into the HDL repressor complex. This study expands our knowledge about the conservation and specialization roles of WUS orthologs among different plant species, especially the regulation of auxin response by HDL in compound leaf morphogenesis.

Data Availability

All datasets generated for this study are included in the manuscript/supplementary files.

Author Contributions

HW, LuH, and CZ conceived the study and designed the experiments. HW, YX, LiH, XZ, XW, JZ, LuH, and ZM performed the experiments. ZD, Z-YW, RL, QY, FK, and CZ analyzed the data, provided the critical discussion on the work, and edited the manuscript. HW and CZ wrote the article.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (2015CB943500), the Shandong Province Natural Science Foundation (ZR2018ZC0334 and ZR2019MC013), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (projects 31671507 and 31371235), and the 1000-Talents Plan from China for Young Researchers.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Yuling Jiao (Institute of Genetics and Developmental Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences) for constructive comments on this manuscript. We thank Prof. Kirankumar Mysore and Dr. Jiangqi Wen (both from Noble Research Institute) for providing the Tnt1 mutants. We also thank the Microscopy Core Facility of School of Life Science in Shandong University for the help with SEM and confocal microscopy work.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2019.01024/full#supplementary-material

References

Arber, A. (1941a). The interpretation of leaf and root in the angiosperms. Biol. Rev. 16 (2), 81–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-185X.1941.tb01096.x

Arber, A. (1941b). On the morphology of the pitcher-leaves in Heliamphora, Sarracenia, Darlingtonia, Cephalotus, and Nepenthes. Ann. Bot. 5 (20), 563–578. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aob.a087407

Barkoulas, M., Hay, A., Kougioumoutzi, E., Tsiantis, M. (2008). A developmental framework for dissected leaf formation in the Arabidopsis relative Cardamine hirsuta. Nat. Genet. 40 (9), 1136–1141. doi: 10.1038/ng.189

Baurle, I., Laux, T. (2005). Regulation of WUSCHEL transcription in the stem cell niche of the Arabidopsis shoot meristem. Plant Cell 17 (8), 2271–2280. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.032623

Benkova, E., Michniewicz, M., Sauer, M., Teichmann, T., Seifertova, D., Jurgens, G., et al. (2003). Local, efflux-dependent auxin gradients as a common module for plant organ formation. Cell 115 (5), 591–602. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00924-3

Bilsborough, G. D., Runions, A., Barkoulas, M., Jenkins, H. W., Hasson, A., Galinha, C., et al. (2011). Model for the regulation of Arabidopsis thaliana leaf margin development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108 (8), 3424–3429. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015162108

Causier, B., Ashworth, M., Guo, W. J., Davies, B. (2012). The TOPLESS interactome: a framework for gene repression in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 158 (1), 423–438. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.186999

Cheng, X., Peng, J., Ma, J., Tang, Y., Chen, R., Mysore, K. S., et al. (2012). NO APICAL MERISTEM (MtNAM) regulates floral organ identity and lateral organ separation in Medicago truncatula. New Phytol. 195 (1), 71–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2012.04147.x

Clark, S. E. (2001). Cell signalling at the shoot meristem. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2 (4), 276–284. doi: 10.1038/35067079

Claßen-Bockhoff, R. (2001). Plant morphology: the historic concepts of Wilhelm Troll, Walter Zimmermann and Agnes Arber. Ann. Bot. 88 (6), 1153–1172. doi: 10.1006/anbo.2001.1544

Crane, C., Wright, E., Dixon, R. A., Wang, Z. Y. (2006). Transgenic Medicago truncatula plants obtained from Agrobacterium tumefaciens-transformed roots and Agrobacterium rhizogenes-transformed hairy roots. Planta 223 (6), 1344–1354. doi: 10.1007/s00425-006-0268-2

Dodsworth, S. (2009). A diverse and intricate signalling network regulates stem cell fate in the shoot apical meristem. Dev. Biol. 336 (1), 1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.09.031

Fletcher, J. C. (2002). Coordination of cell proliferation and cell fate decisions in the angiosperm shoot apical meristem. Bioessays 24 (1), 27–37. doi: 10.1002/bies.10020

Hamada, S., Onouchi, H., Tanaka, H., Kudo, M., Liu, Y. G., Shibata, D., et al. (2000). Mutations in the WUSCHEL gene of Arabidopsis thaliana result in the development of shoots without juvenile leaves. Plant J. 24 (1), 91–101. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00858.x

Ikeda, M., Mitsuda, N., Ohme-Takagi, M. (2009). Arabidopsis WUSCHEL is a bifunctional transcription factor that acts as a repressor in stem cell regulation and as an activator in floral patterning. Plant Cell 21 (11), 3493–3505. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.069997

Je, B. I., Gruel, J., Lee, Y. K., Bommert, P., Arevalo, E. D., Eveland, A. L., et al. (2016). Signaling from maize organ primordia via FASCIATED EAR3 regulates stem cell proliferation and yield traits. Nat. Genet. 48 (7), 785–791. doi: 10.1038/ng.3567

Karimi, M., Inze, D., Depicker, A. (2002). GATEWAY((TM)) vectors for Agrobacterium-mediated plant transformation. Trends Plant Sci. 7 (5), 193–195. doi: 10.1016/S1360-1385(02)02251-3

Kieffer, M., Stern, Y., Cook, H., Clerici, E., Maulbetsch, C., Laux, T., et al. (2006). Analysis of the transcription factor WUSCHEL and its functional homologue in Antirrhinum reveals a potential mechanism for their roles in meristem maintenance. Plant Cell 18 (3), 560–573. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.039107

Koenig, D., Bayer, E., Kang, J., Kuhlemeier, C., Sinha, N. (2009). Auxin patterns Solanum lycopersicum leaf morphogenesis. Development 136 (17), 2997–3006. doi: 10.1242/dev.033811

Laux, T., Mayer, K. F. X., Berger, J., Jurgens, G. (1996). The WUSCHEL gene is required for shoot and floral meristem integrity in Arabidopsis. Development 122 (1), 87–96.

Liu, Z., Karmarkar, V. (2008). Groucho/Tup1 family co-repressors in plant development. Trends Plant Sci. 13 (3), 137–144. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2007.12.005

Lu, Z., Shao, G., Xiong, J., Jiao, Y., Wang, J., Liu, G., et al. (2015). MONOCULM 3, an ortholog of WUSCHEL in rice, is required for tiller bud formation. J. Genet. Genomics 42 (2), 71–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jgg.2014.12.005

Mayer, K. F. X., Schoof, H., Haecker, A., Lenhard, M., Jurgens, G., Laux, T. (1998). Role of WUSCHEL in regulating stem cell fate in the Arabidopsis shoot meristem. Cell 95 (6), 805–815. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81703-1

Meng, Y., Liu, H., Wang, H., Liu, Y., Zhu, B., Wang, Z., et al. (2019). HEADLESS, a WUSCHEL homolog, uncovers novel aspects of shoot meristem regulation and leaf blade development in Medicago truncatula. J. Exp. Bot. 70 (1), 149–163. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ery346

Nardmann, J., Werr, W. (2006). The shoot stem cell niche in angiosperms: expression patterns of WUS orthologues in rice and maize imply major modifications in the course of mono- and dicot evolution. Mol. Biol. Evol. 23 (12), 2492–2504. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msl125

Niu, L., Lin, H., Zhang, F., Watira, T. W., Li, G., Tang, Y., et al. (2015). LOOSE FLOWER, a WUSCHEL-like homeobox gene, is required for lateral fusion of floral organs in Medicago truncatula. Plant J. 81 (3), 480–492. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12743

Ohmori, Y., Tanaka, W., Kojima, M., Sakakibara, H., Hirano, H. Y. (2013). WUSCHEL-RELATED HOMEOBOX4 is involved in meristem maintenance and is negatively regulated by the CLE gene FCP1 in rice. Plant Cell 25 (1), 229–241. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.103432

Ou, B., Yin, K. Q., Liu, S. N., Yang, Y., Gu, T., Wing Hui, J. M., et al. (2011). A high-throughput screening system for Arabidopsis transcription factors and its application to Med25-dependent transcriptional regulation. Mol. Plant 4 (3), 546–555. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssr002

Sarkar, A. K., Luijten, M., Miyashima, S., Lenhard, M., Hashimoto, T., Nakajima, K., et al. (2007). Conserved factors regulate signalling in Arabidopsis thaliana shoot and root stem cell organizers. Nature 446 (7137), 811–814. doi: 10.1038/nature05703

Stuurman, J., Jaggi, F., Kuhlemeier, C. (2002). Shoot meristem maintenance is controlled by a GRAS-gene mediated signal from differentiating cells. Genes Dev. 16 (17), 2213–2218. doi: 10.1101/gad.230702

Tadege, M., Lin, H., Bedair, M., Berbel, A., Wen, J., Rojas, C. M., et al. (2011). STENOFOLIA regulates blade outgrowth and leaf vascular patterning in Medicago truncatula and Nicotiana sylvestris. Plant Cell 23 (6), 2125–2142. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.085340

Tanaka, W., Ohmori, Y., Ushijima, T., Matsusaka, H., Matsushita, T., Kumamaru, T., et al. (2015). Axillary meristem formation in rice requires the WUSCHEL ortholog TILLERS ABSENT1. Plant Cell 27 (4), 1173–1184. doi: 10.1105/tpc.15.00074

Voinnet, O., Rivas, S., Mestre, P., Baulcombe, D. (2015). An enhanced transient expression system in plants based on suppression of gene silencing by the p19 protein of tomato bushy stunt virus (Retraction of Vol 33, Pg 949, 2003). Plant J. 84 (4), 846–846. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13066

Wang, H. L., Chen, J. H., Wen, J. Q., Tadege, M., Li, G. M., Liu, Y., et al. (2008). Control of compound leaf development by FLORICAULA/LEAFY ortholog SINGLE LEAFLET1 in Medicago truncatula. Plant Physiol. 146 (4), 1759–1772. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.117044

Yadav, R. K., Perales, M., Gruel, J., Girke, T., Jonsson, H., Reddy, G. V. (2011). WUSCHEL protein movement mediates stem cell homeostasis in the Arabidopsis shoot apex. Genes Dev. 25 (19), 2025–2030. doi: 10.1101/gad.17258511

Yadav, R. K., Tavakkoli, M., Reddy, G. V. (2010). WUSCHEL mediates stem cell homeostasis by regulating stem cell number and patterns of cell division and differentiation of stem cell progenitors. Development 137 (21), 3581–3589. doi: 10.1242/dev.054973

Yasui, Y., Ohmori, Y., Takebayashi, Y., Sakakibara, H., Hirano, H. Y. (2018). WUSCHEL-RELATED HOMEOBOX4 acts as a key regulator in early leaf development in rice. PLoS Genet. 14 (4), e1007365. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007365

Zhang, F., Wang, Y. W., Li, G. F., Tang, Y. H., Kramer, E. M., Tadege, M. (2014). STENOFOLIA recruits TOPLESS to repress ASYMMETRIC LEAVES2 at the leaf margin and promote leaf blade outgrowth in Medicago truncatula. Plant Cell 26 (2), 650–664. doi: 10.1105/tpc.113.121947

Zhou, C. N., Han, L., Fu, C. X., Wen, J. Q., Cheng, X. F., Nakashima, J., et al. (2013). The trans-acting short interfering RNA3 pathway and NO APICAL MERISTEM antagonistically regulate leaf margin development and lateral organ separation, as revealed by analysis of an argonaute7/lobed leaflet1 mutant in Medicago truncatula. Plant Cell 25 (12), 4845–4862. doi: 10.1105/tpc.113.117788

Keywords: Medicago truncatula, WUSCHEL, SAM maintenance, smooth leaf margin1 (SLM1), auxin response, compound leaf

Citation: Wang H, Xu Y, Hong L, Zhang X, Wang X, Zhang J, Ding Z, Meng Z, Wang Z-Y, Long R, Yang Q, Kong F, Han L and Zhou C (2019) HEADLESS Regulates Auxin Response and Compound Leaf Morphogenesis in Medicago truncatula. Front. Plant Sci. 10:1024. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2019.01024

Received: 30 May 2019; Accepted: 22 July 2019;

Published: 16 August 2019.

Edited by:

Elena M. Kramer, Harvard University, United StatesCopyright © 2019 Wang, Xu, Hong, Zhang, Wang, Zhang, Ding, Meng, Wang, Long, Yang, Kong, Han and Zhou. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lu Han, bGhhbkBzZHUuZWR1LmNu; Chuanen Zhou, Y3pob3VAc2R1LmVkdS5jbg==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work.

Hongfeng Wang

Hongfeng Wang Yiteng Xu

Yiteng Xu Limei Hong1

Limei Hong1 Zhaojun Ding

Zhaojun Ding Ruicai Long

Ruicai Long Qingchuan Yang

Qingchuan Yang Chuanen Zhou

Chuanen Zhou