95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Plant Sci. , 16 January 2019

Sec. Plant Pathogen Interactions

Volume 9 - 2018 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2018.01992

This article is part of the Research Topic Metabolic Adjustments and Gene Expression Reprogramming for Symbiotic Nitrogen Fixation in Legume Nodules View all 12 articles

Aoi Sogawa1†

Aoi Sogawa1† Akihiro Yamazaki2†

Akihiro Yamazaki2† Hiroki Yamasaki1

Hiroki Yamasaki1 Misa Komi1

Misa Komi1 Tomomi Manabe1

Tomomi Manabe1 Shigeyuki Tajima1

Shigeyuki Tajima1 Makoto Hayashi2

Makoto Hayashi2 Mika Nomura1*

Mika Nomura1*SNARE (soluble N-ethyl maleimide sensitive factor attachment protein receptor) proteins mediate membrane trafficking in eukaryotic cells. Both LjVAMP72a and LjVAMP72b are members of R-SNARE and belong to a symbiotic subgroup of VAMP72 in Lotus japonicus. Their sequences are closely related and both were induced in the root upon rhizobial inoculation. The expression level of LjVAMP72a in the nodules was higher than in the leaves or roots; however, LjVMAP72b was expressed constitutively in the leaves, roots, and nodules. Immunoblot analysis showed that not only LjVAMP72a but also LjVAMP72b were accumulated in a symbiosome-enriched fraction, suggesting its localization in the symbiosome membrane during nodulation. Since there was 89% similarity between LjVAMP72a and LjVAMP72b, knockdown mutant by RNAi suppressed both genes. The suppression of both genes impaired root nodule symbiosis (RNS). The number of bacteroids and the nitrogen fixation activity were severely curtailed in the nodules formed on knockdown roots (RNAi-LjVAMP72a/72b). Arbuscular mycorrhization (AM) was also attenuated in knockdown roots, indicating that LjVAMP72a and LjVAMP72b were required to establish not only RNS but also AM. In addition, transgenic hairy roots of RNAi-LjVAMP72a/72b suppressed the elongation of root hairs without infections by rhizobia or arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Amino acid alignment showed the symbiotic subclade of VAMP72s containing LjVAMP72a and LjVAMP72b were a conserved six amino acid region (HHQAQD) within the SNARE motif. Taken together, our data suggested that LjVAMP72a and LjVAMP72b positively controlled both symbioses and root hair formation by affecting the secretory pathway.

Legume-rhizobia interaction has developed from complex signal exchange. Upon sensing host plant-derived flavonoids, rhizobia produce and secrete lipochito-oligosaccharides called nodulation factors (nod factors), which are then recognized by the host and trigger multiple events leading to establishing root nodule symbiosis (RNS) (Dénarié et al., 1996; Oldroyd, 2013). During nodulation, bacterial infection and nodule organogenesis take place in epidermal and cortical cells, respectively (Suzaki and Kawaguchi, 2014). Nod factors trigger deformation and curling of root hairs. Rhizobia then penetrate into root hairs via infection threads (Kouchi et al., 2010; Oldroyd, 2013). Simultaneously, cell division occurs in the cortical layer to form nodule primordia (Oldroyd, 2013). When infection threads reach the nodule primordia, rhizobia are released from the infection threads to nodule primordia by an endocytosis-like process, in which rhizobial cells are surrounded by host-derived membranes [symbiosome membrane (SM)] called a “symbiosome” (Newcomb, 1976; Verma et al., 1978). In addition to RNS, legumes establish an endosymbiotic association with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF). AMF secrete sulfated and non-sulfated lipochito-oligosaccharide signals (Myc-LCOs), which function as signals for allowing AMF to enter host roots (Maillet et al., 2011). AMF penetrate the root epidermis by forming hyphopodia on the root surface and extend their internal hyphae toward the inner cortex, where they form arbuscules that are surrounded by a plant plasma membrane called a periarbuscular membrane (PAM). These dynamic changes to form a SM and PAM are closely associated by membrane trafficking of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and/or Golgi apparatus and their transport vesicles (Robertson et al., 1978; Newcomb and McIntyre, 1981; Roth and Stacy, 1989; Genre et al., 2012).

SNARE (soluble NSF attachment protein receptor) proteins are known to mediate the transport vesicle, and its molecules have a highly conserved coiled-coil domain known as a SNARE motif (Harbury, 1998; Jahn et al., 2003). The SNARE-mediated membrane trafficking forms SNARE complexes with R-SNARE on the vesicle and two or three Q-SNAREs on the target membrane. During the past decade, it has been clear that SNARE proteins play roles in general homeostatic and housekeeping functions within the cell. In Arabidopsis, two plasma membrane-localized Qa-SNAREs, SYP123 and SYP132, mediate membrane trafficking for root hair formation (Ichikawa et al., 2014). Recently, a symbiotic Qa-SNARE protein, SYP132A, has been shown to be generated by alternative termination of transcription and is essential for the formation of both SM and PAM in Medicago truncatula (Huisman et al., 2016; Pan et al., 2016). R-SNAREs located on the transport vesicles are classified into three groups: Sec22, YKT6, and VAMP7 (McNew et al., 1997; Galli et al., 1998; Gonzalez et al., 2001). VAMP7 consists of two major subgroups in plants: VAMP71 and VAMP72 (Sanderfoot, 2007). VAMP71 is known to have a similar function to mammalian VAMP7s; however, another group, VAMP72, appears to be specific to green plants (Sanderfoot, 2007). The Arabidopsis VAMP72 proteins except AtVAMP727 are localized in the plasma membrane (Marmagne et al., 2004; Uemura et al., 2004). To determine the specific function for symbiosis, it is better to focus on VAMP72 in legume plants. In M. truncatula, VAMP721d and VAMP721e are required for both RNS and arbuscular mycorrhization (AM) (Ivanov et al., 2012). For Lotus japonicus, there are reports on SNARE-mediated membrane trafficking in nodules. The sed5-like LjSYP132-1, Qa-SNARE, contributes to nodule formation and plant growth development (Mai et al., 2006). SYP71, Qc-SNARE, plays a role in symbiotic nitrogen fixation (Hakoyama et al., 2012). However, there is no report on R-SNARE. In this study, we focused on an R-SNARE, VAMP72, in the formation of symbiotic interfaces. Our data revealed that LjVAMP72a and LjVAMP72b were required for both RNS and AM as well as for root hair development.

Seeds of L. japonicus B129 Gifu (Handberg and Stougaard, 1992) were surface sterilized with 3% sodium hypochlorite and then germinated. Six-day-old seedlings were transplanted onto sterile vermiculite with a half concentration of B&D medium (Broughton and Dilworth, 1971), followed by inoculation with Mesorhizobium loti strain MAFF303099 at 7 days after transplanting. Plants were grown in a growth chamber at 24°C under a 16 h light/b h dark condition.

Total RNA was isolated from various organs of L. japonicus using the RNeasy Plant Mini Kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Qiagen, Tokyo, Japan). The cDNA was synthesized using PrimeScript RT Master Mix (Takara, Shiga, Japan). Quantitative RT-PCR reactions were performed in triplicate on cDNA (equivalent to about 100 ng of RNA) using the SYPR premix Ex Taq (Takara), and real time detection was performed on a Thermal Cycler Dice Real Time System II (Takara) with the primer set shown in Supplementary Table S1. Ubiquitin was used as an internal standard. All data were normalized because the expression levels of ubiquitin are equal in each sample. All experiments were performed with more than three biological replications.

Putative orthologs of MtVAMP72d were searched for in a database consisting of genomes and transcriptomes (i.e., all available CDSs) of 70 green plant species (Sato et al., 2008; Carleton College, and The Science Education Resource Center, 2010; Goodstein et al., 2012; Dash et al., 2016) (see Supplementary Table S1 for the complete list). OrthoReD (Battenberg et al., 2017) was used to predict the orthologs of MtVAMP72d with its amino acid sequence as a query against the database without setting any outgroups. Based on the phylogenetic tree reconstructed by OrthoReD, a clade of putative orthologs of MtVAMP72d in several species (A. thaliana, Glycine max, L. japonicus, M. truncatula, Solanum lycopersicum, Populus trichocarpa, and Vitis vinifera following Ivanov et al., 2012) was determined manually. Gene names corresponding to Gene ID used in this study were listed in Supplementary Table S2.

The phylogeny of these putative orthologs was reconstructed. Amino acid sequences of these putative orthologs were aligned using MAFFT v7.407 (Katoh and Standley, 2013). Based on the multiple sequence alignment, the most likely phylogeny was reconstructed using RAxML v8.2.12 (Stamatakis, 2006). The best of four parallel runs was chosen as the most likely tree to avoid having the tree lodged onto a local optimum. Rapid bootstrapping of 100 replicates was also carried out using RAxML v8.2.12.

Isolated cDNA and PCR amplified products were sequenced according to the manufacturer’s instructions for the DNA sequencer (Model 3700; Applied Biosystems, CA, United States). The CDS of LjVAMP72b was speculated by genome sequence (Sato et al., 2008) and nodule cDNA was amplified with following primers; FW, 5′-ATGGGTCAGAACCAGAGATC-3′; RV, 5′-CCTTTCCTCGCATAATCACAA-3′ using Tks Gflex DNA polymerase (Takara, Japan). The resulting PCR product was sequenced from both strands.

To construct the LjVAMP72a promoter fused to the GUS gene, the GUS-NOS gene was first cloned into the XbaI/SalI sites of pC1300GFP, kindly provided by Dr. H. Kouchi (National Institute of Agricultural Sciences, Tsukuba), producing the GUS-NOS in pC1300 GFP. The 5′-flanking regions [-1,817 to before ATG of the translation-initiation site in the LjVAMP72a gene (genome clone; CM0066)] was then cloned into the GUS-NOS in pC1300GFP, following the production of LjVAMP72a prom::GUS.

To construct RNAi-LjVAMP72a/72b, the cDNA of LjVAMP72a was amplified using PCR from an EST clone MR100a03 (accession No. BP083622) with the following primers: RNAi-f, 5′-ATG GAT CCC TCG AGA ATG GCT ACA CAT ATT-3′ and RNAi-r, 5′-ATA TCG ATG GTA CCT TTT GGG AAT CCA CGA-3′. The amplified cDNA fragments for the RNAi construct was subcloned into the appropriate cloning sites of pC1300GFP. The procedure for constructing it has been described previously (Shimomura et al., 2006). Since the amplified cDNA has high similarity between LjVAMP72a and LjVAMP72b, the knockdown mutant suppressed both genes. Therefore the mutant was named as RNAi-LjVAMP72a/72b.

To construct LjVAMP72a-GFP, used by Arabidopsis suspension cells, LjVAMP72a cDNA was fused to the sGFP under the control of CaMV35S-sGFP (S65T)-NOS3′ (Niwa et al., 1999), provided by Dr. Y. Niwa, University of Shizuoka.

Hairy root transformation of L. japonicus Gifu using Agrobacterium rhizogenes LBA1334 was performed according to a procedure described previously (Kumagai and Kouchi, 2003). Transgenic hairy roots with GFP fluorescence were selected and transferred to vermiculite pots with a half concentration of B&D medium. Plants were grown in a growth cabinet at 24°C (16 h light/b h dark). After 1 week, the plants were transferred to pots and then inoculated with M. loti MAFF303099 and continued to grow in the same medium.

Hairy roots transformed with the LjVAMP72a prom::GUS construct were stained for 2 h at 37°C as described previously (Mai et al., 2006). GUS-stained nodules were observed using a DM6 upright microscope (Leica, Germany) with a differential interference contrast mode. Mycorrhized roots were embedded in 5% agarose, sliced in b0 μm sections using a Zero 1 super microslicer (D.S.K., Japan), and observed using the DM6 (Leica).

LjVAMP72a cDNA was fused to the sGFP of a CaMV35S-sGFP (S65T)-NOS3′ vector, producing the LjVAMP72a-GFP. RFP-tagged Arabidopsis AtSYP722, AtSYP722-RFP, was kindly provided by Dr. T. Ueda, University of Tokyo. The transient expression of LjVAMP72a-GFP and AtSYP722-RFP in Arabidopsis suspension culture cells was performed following a previous report (Ueda et al., 2001).

Plant tissue (0.1 g) was harvested after 35 days infection and homogenized with a mortar and pestle in extraction buffer containing 250 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 700 mM sucrose, 100 mM KCl, 2% (w/v) insoluble polyvinylpolypyrrolidone, 2% 2-mercaptoethanol, and 2% SDS. After total maceration, water-saturated phenol was added and then centrifuged at 3,000 ×g for 20 min. The phenol fraction was isolated and five volumes of methanol plus 100 mM ammonium acetate including 10 mM 2-mercaptoethanol were added. After incubation at -80°C for 2 h, the solution was centrifuged at 15,000 ×g for 5 min, and the pellets were resuspended with sample buffer [50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 6b), 100 mM DTT, 2% SDS, and 10% glycerol]. SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) was performed according to the procedure of Nomura et al. (2006). Immunoblot analysis was performed with rabbit antisera raised against a protein of (ENIEKVLDRGEKIE) antibody as the primary antibody and detected using ECL and a western blotting detection system (GE Healthcare, United Kingdom). Since the produced antibody can detect both proteins, the resulting antibody was named anti-LjVAMP72a/72b antibody. The protein concentration was determined using the Lowry method (Lowry et al., 1951). Lb antibody raised against rabbit was kindly provided by Prof. N. Suganuma, Aichi University of Education, Japan.

Fresh nodules (10–15 g) at 4 weeks post infection were used to isolate the symbiosome fraction. The symbiosome fraction was isolated from Percoll discontinuous gradients (Day et al., 1989). In brief, nodule homogenate was centrifuged at 1,000 rpm for 15 min, and the pellet was then suspended with washing medium and further centrifuged at 2,000 rpm for 10 min. The resulting pellet was used for Percoll discontinuous gradients (80, 60, and 45%), and loose pellets were collected from the bottom of the 80% layer and the 60/80% interface as a symbiosome fraction. The isolated symbiosome fraction was suspended in washing medium and used for immunoblot analysis. After centrifugation at 1,000 and 2,000 rpm, both supernatants were used as a soluble fraction.

For acetylene reduction activity, transgenic hairy root nodules were selected under fluorescence microscopy because the GFP gene was inserted in the construct vectors. The activity of GFP-positive nodules was measured using gas chromatography (Shimadzu GC-8A; Kyoto, Japan) as previously described (Suganuma et al., 1998). Experiments were performed with more than three biological replications.

Hairy roots of L. japonicus expressing the LjVAMP72a and LjVAMP72b knockdown construct (RNAi-LjVAMP72a/72b) were observed using the DM6 (Leica). Pictures were tiled using Microsoft Image Composite Editor (Microsoft, United States). The length of the root hairs was measured from a position 1 mm from the root tip. The length of 50 root hairs per transgenic plant was measured using Image J. Experiments were performed with more than three biological replications.

Lotus japonicus expressing the RNAi-LjVAMP72a/72b construct or GFP only (empty vector) in the hairy roots were planted in plastic pots filled with sterile vermiculites in ½ Hoagland culture medium and inoculated with Rhizophagus irregularis (Premier Tech, Rivière-du-Loup, Canada) at 100 spores/plant. At 6 weeks after inoculation, the roots were stained with 0.05% trypan blue, and AM events were numbered and calculated using the line intersect method (McGonigle et al., 1990). Pictures of AMF-inoculated roots were taken using the DM6 (Leica) after staining.

Hairy roots were inoculated with M. loti strain MAFF303099 expressing a red fluorescent protein from Discosoma sp. (DsRed) (Maekawa et al., 2009) and used in our nodulation test. Transgenic hairy roots were selected by GFP fluorescence and observed under a fluorescence microscope (Olympus SZX9). After infection of DsRed-labeled M. loti, bacteroid was isolated from the nodule and the number of bacteroid in each transgenic nodule was counted using fluorescent microscope BX51 (Olympus).

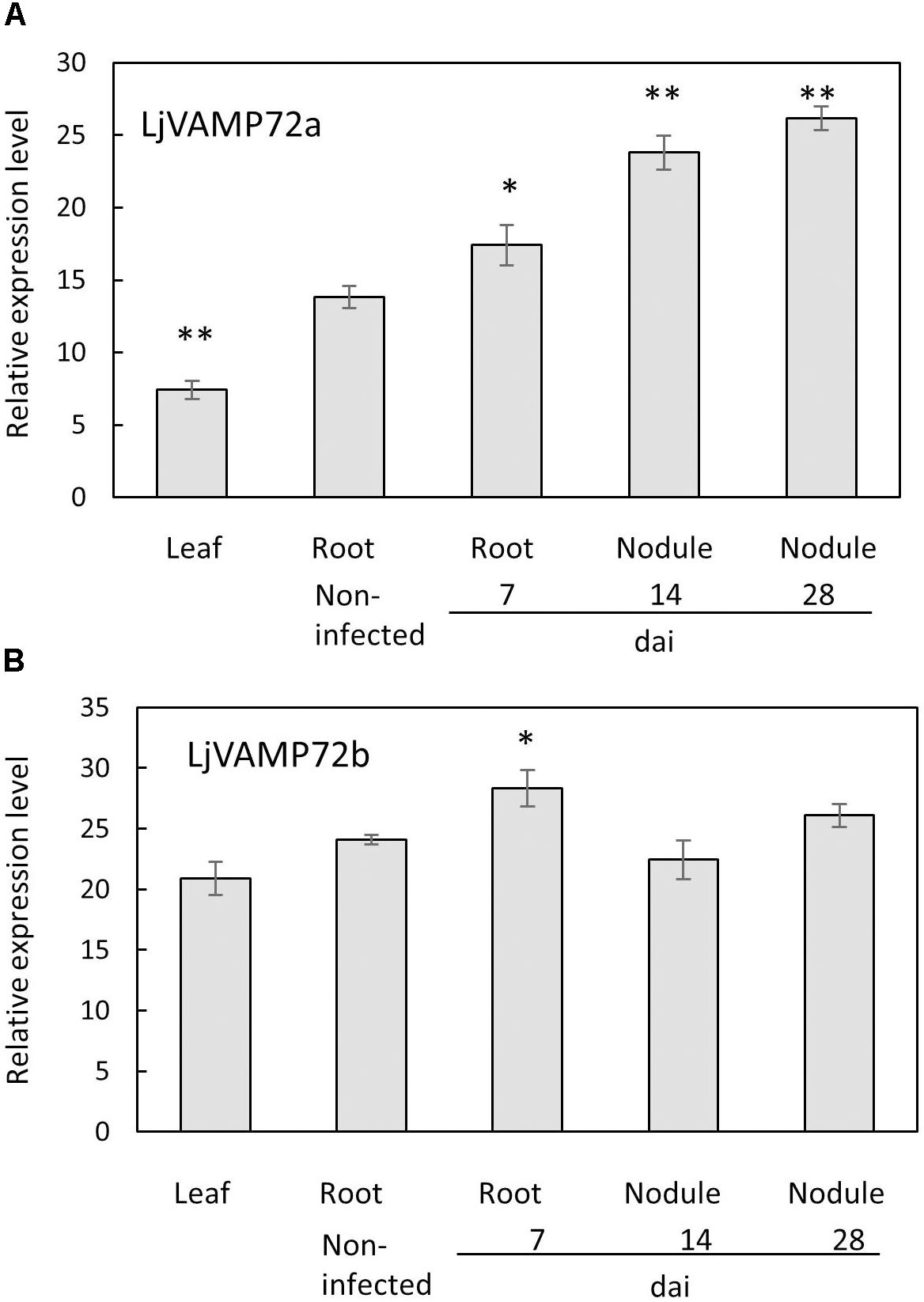

The genome database of L. japonicus1 possesses several VAMP72 proteins from LjVAMP72a to LjVAMP72f, LjVAMP724 and LjVAMP727. We found that one of the LjVAMP72s, LjVAMP72a in L. japonicus, was expressed in the nodules, induced upon rhizobial inoculation, and peaked at 14 days after inoculation (Figure 1). In addition, the genome database contains another LjVAMP72, LjVAMP72b, which has high homology to LjVAMP72a. There was 89% similarity between LjVAMP72a and LjVAMP72b. The expression of the LjVAMP72a genes was induced in the infected roots and nodules; however, LjVAMP72b was expressed constitutively in the leaves, roots, and nodules (Figure 1).

Figure 1. (A,B) Expression of LjVAMP72a and LjVAMP72b mRNA after inoculation with M. loti. The ubiquitin was used as an internal control. dai: days after inoculation. Experiments were performed with more than three biological replications. Statistically significant differences compared with non-infected roots were indicated by asterisks (∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.001).

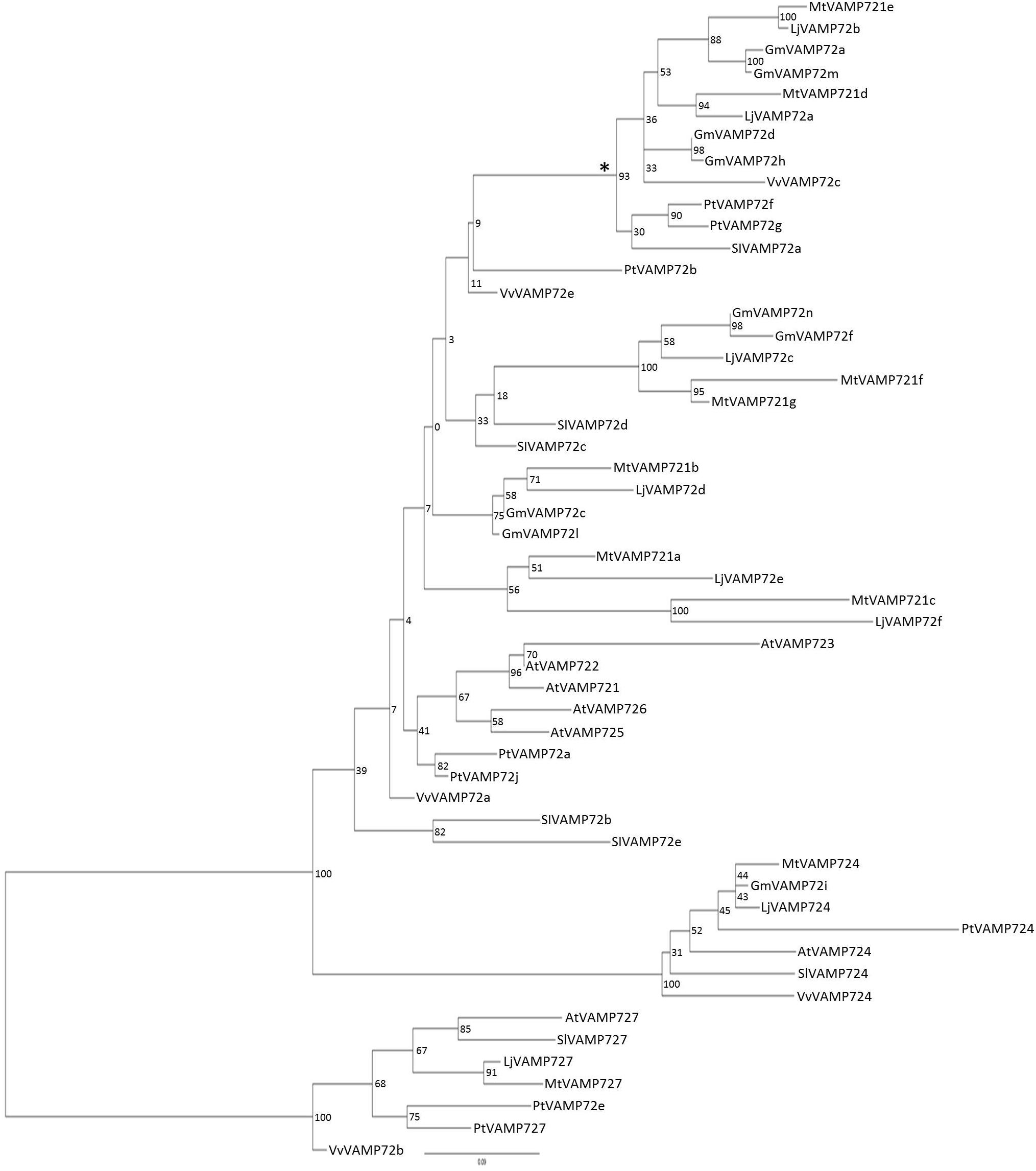

The phylogenic analysis (Figure 2) showed that both LjVAMP72a and LjVAMP72b belong to the “symbiotic” subgroup and were orthologous to MtVAMP721d and MtVAMP721e, respectively, which have been reported to function in symbioses (Ivanov et al., 2012).

Figure 2. Phylogenetic tree of VAMP72s. Phylogenetic tree of VAMP72s among L. japonicus (LjVAMP72s), Medicago truncatula (MtVAMP72s), G. max (GmVAMP72s), Phaseolus vulgaris (PvVAMP72s), Vitis vinifera (VvVAMP72s), Populus trichocarpa (PtVAMP72s), Solanum lycopersicum (SlVAMP72s), and Arabidopsis thaliana (AtVAMP72s). Gene ID corresponding to gene name was listed in Supplementary Table S2. The symbiotic subgroup was indicated with an asterisk. AtVAMP727 was used as an outgroup.

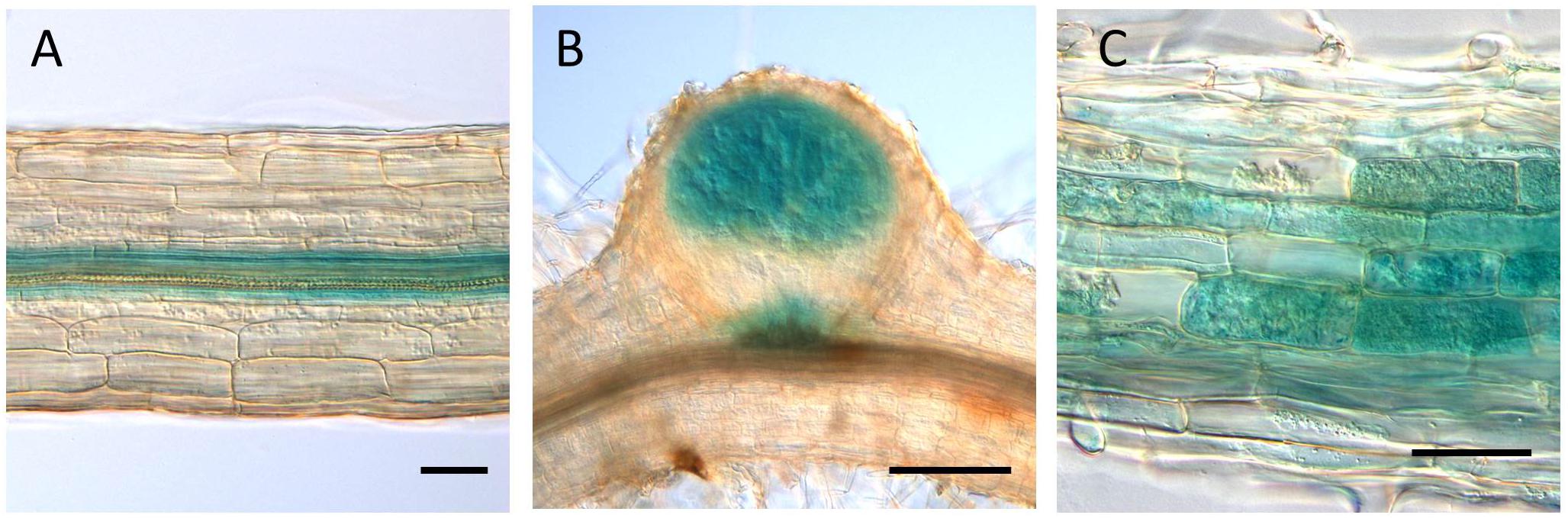

The GUS expression by the LjVAMP72a promoter was detected at the vascular bundle in non-infected roots (Figure 3A). The expression was strongly induced in nodule primordia upon rhizobial inoculation besides its basal expression at the vascular bundles of the roots (Figure 3B). The GUS induction at the vascular bundle of infected roots was detected with longer staining (data not shown). The higher GUS expression by the LjVAMP72a promoter in the nodules than that in the roots was identical to that expression level of the LjVAMP72a in nodules was higher than that in roots at 28 days after infection (Figure 1). AM also positively affected LjVAMP72a promoter activity. During AM, LjVAMP72a was induced in cells where arbuscules formed (Figure 3C). These data suggested that the LjVAMP72a plays a role in both symbioses, RNS and AM. Because the genome sequence of LjVAMP72b was not completed, we have not constructed the LjVAMP72b promoter fused to the GUS gene.

Figure 3. LjVAMP72a promoter activity during symbioses. The promoter activity of LjVAMP72a was visualized by staining the β-glucuronidase activity in transgenic hairy roots under three different conditions: (A) non-inoculated, (B) inoculated with M. loti MAFF303099, and (C) inoculated with R. irregularis. Pictures were taken at 14 and 48 days after inoculation for (B,C), respectively. Scale bars represent 100 μm for (A,C) and 200 μm for (B).

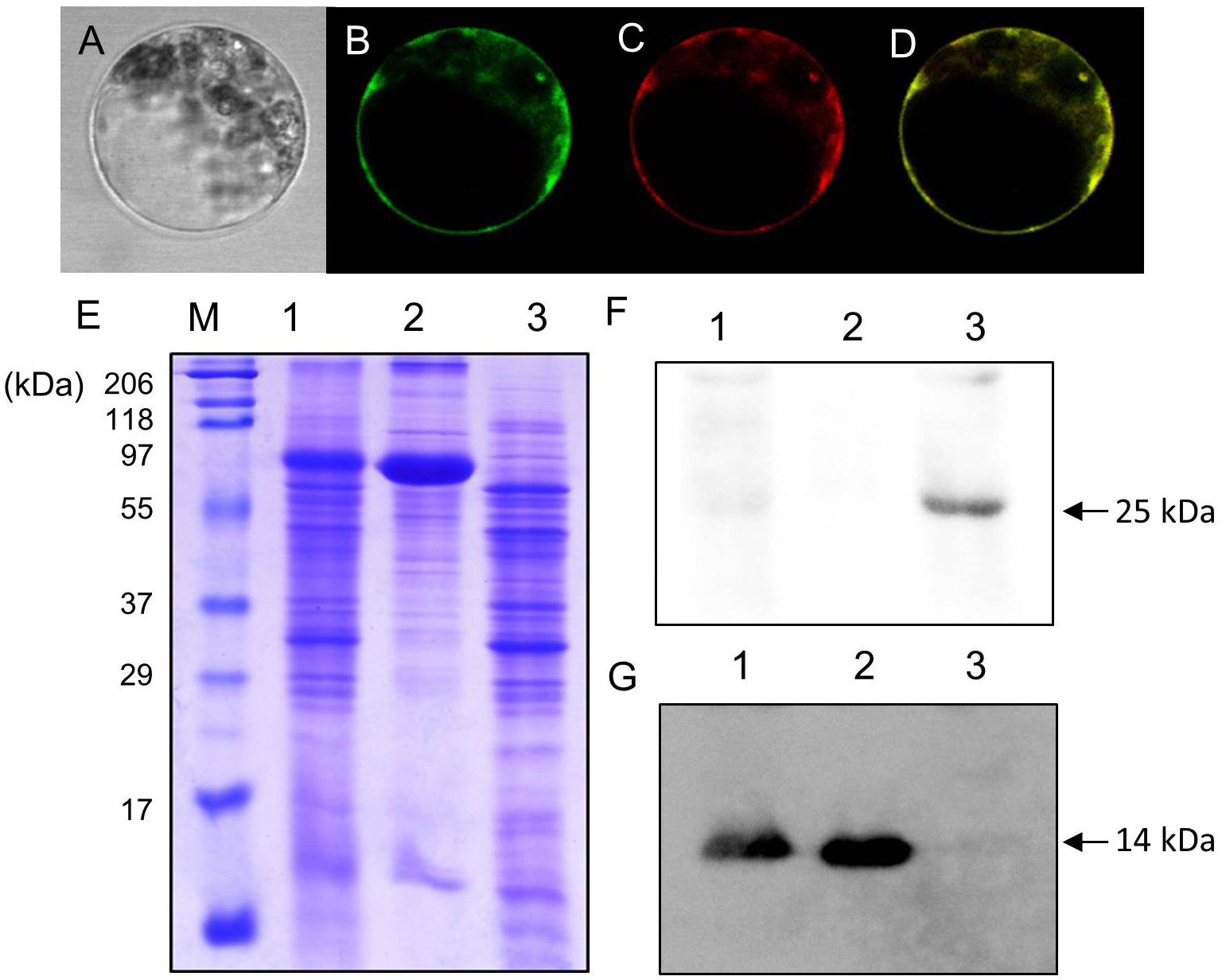

Uemura et al. (2004) identified AtVAMP722 SNARE localized in the plasma membrane in Arabidopsis suspension cells. Figure 4 shows LjVAMP72a co-localization with AtVAMP722 in suspension culture cells of A. thaliana, indicating its localization in plasma membrane (Figures 4A–D). We have produced a peptide antibody that can detect both LjVAMP72a and LjVAMP72b. After isolating the symbiosome-enriched fraction, immunoblot analysis was performed (Figure 4). Since the deduced molecular weight of LjVAMP72a and LjVAMP72b was similar (ca. 25 kDa), one band was detected at the deduced molecular size in the symbiosome-enriched fraction (Figure 4F, Lane 3). The LjVAMP72a and LjVAMP72b were not fractionated in the soluble fractions in which leghaemoglobin was detected (Figure 4G, Lanes 1 and 2). SM contains some of components present in the plasma membrane and the results showing its localization in the plasma membrane were obtained in Arabidopsis suspension cells. Taken together, these data indicated that LjVAMP72a and LjVAMP72b localized in the SM.

Figure 4. Cellular localization of LjVAMP72a and LjVAMP72b. (A–D) Transient expression of LjVAMP72a in Arabidopsis suspension cells. The GFP-tagged LjVAMP72a (B) and RFP-tagged Arabidopsis AtSYP722 (C) were transiently expressed in the protoplasts of Arabidopsis cells. Bright field (A) and fluorescence images were captured from the same cells expressing each GFP-tagged LjVAMP72a (B) or RFP-tagged AtSYP722 (C). (D) is a merging of (B,C). (E) Fractionated extracts from nodules were separated by SDS-PAGE and stained with CBB. (F,G) Immunoblot analysis using anti-LjVAMP72a/72b antibody (F) or anti-Lb antibody (G). Lane 1: crude extract from nodules, lane 2: supernatant of the crude extract, lane 3: symbiosome-enriched fraction of a Percoll-mediated equilibrium density-gradient centrifugation. Arrowheads indicate LjVAMP72a/72b (F) and Lb (G), respectively.

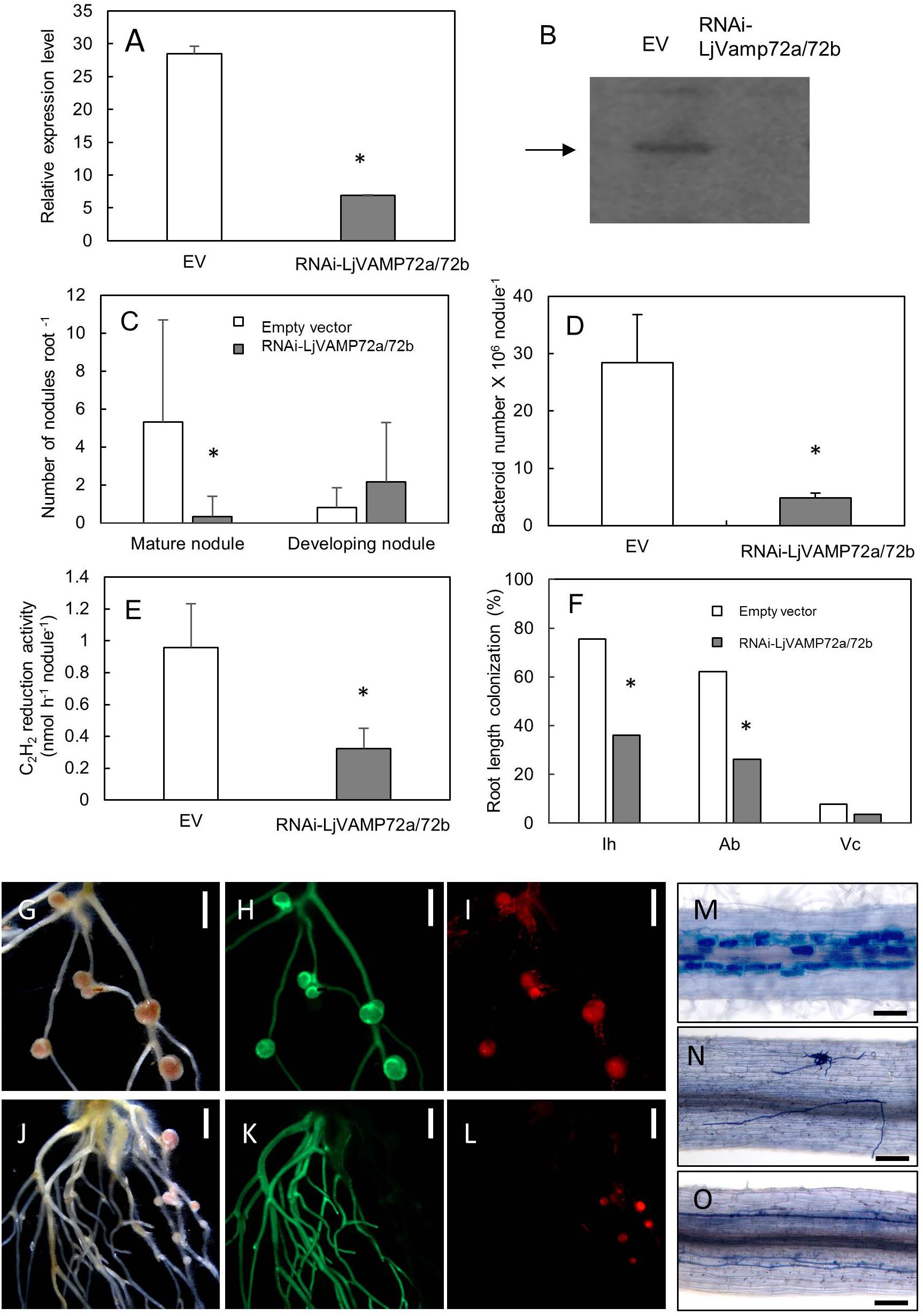

We made the transgenic hairy roots of knockdown LjVAMP72a genes. RNA interference of LjVAMP72a was confirmed using qRT-PCR (Figure 5A). Immunoblot analysis showed that no band could be detected in a knockdown mutant, suggesting that both LjVAMP72a and LjVAMP72b were suppressed in the knockdown mutant (Figure 5B). Therefore, the knockdown mutant was named as RNAi-LjVAMP72a/72b.

Figure 5. LjVAMP72a and LjVAMP72b were required for RNS and AM. RNA interference of LjVAMP72a/72b was confirmed using qRT-PCR (A) and western blot using an anti-LjVAMP72a/72b antibody (B). Arrowhead indicates LjVAMP72a. LjVAMP72a/72b knockdown attenuated the number of mature nodules (C), the number of bacteroids (D), acetylene reduction activity (E), and arbuscular mycorrhization (F). Photos of nodulation and arbuscular mycorrhization (G–O). Pictures of M. loti DsRed13-inoculated hairy roots transformed with an empty vector (G–I) or RNAi-LjVAMP72a/72b (J–L) at 28 days after inoculation were taken with a bright field (G,J), GFP fluorescence (H,K), and DsRed fluorescence (I,L). Transgenic hairy roots transformed with an empty vector (M) or with RNAi-LjVAMP72a/72b (N,O) were inoculated with R. irregularis and were stained with toluidine blue at 42 days after inoculation. The square boxes of white and gray in (C,F) indicate transgenic hairy roots transformed empty vector and RNAi-LjVAMP72a/72b, respectively. EV, empty vector; Ih, internal hyphae; Ab, arbuscule; Vc, vesicle. Scale bars represent 2 mm for (G–L) and 100 μm for (M–O). All experiments were performed with more than three biological replications. Statistically significant differences compared with EV are indicated by asterisks (p < 0.01).

The number of mature nodules was significantly lower in the RNAi-LjVAMP72a/72b roots compared with that in the roots transformed with an empty vector (Figures 5C,G–L). On the other hand, the number of developing nodules of RNAi-LjVAMP72a/72b increased, and the number of bacteroids and acetylene reduction activity were severely attenuated in the RNAi-LjVAMP72a/72b roots (Figures 5D,E).

LjVAMP72a and LjVAMP72b also positively affected AM (Figures 5F,M–O). Frequencies of the internal hyphae invasion, arbuscular and vesicle formation were significantly impaired in the RNAi-LjVAMP72a/72b knockdown roots (Figure 5F). Figure 5N shows the external hyphae did not invade the roots. Some of the infected roots only exhibited internal hyphae with almost no arbuscule when LjVAMP72a/72b was knocked-down (Figure 5O), whereas the empty vector control barely affected arbuscule formation (Figure 5M). These data speculate the symbiotic membranes would be developed by the vesicle trafficking through the LjVAMP72a and LjVAMP72b, resulting that the RNAi-LjVAMP72a/72b knockdown attenuated symbioses. These results were in line with a previous report in which the VAMP721d and VAMP721e double knockdown attenuated the number of nodules in M. truncatula (Ivanov et al., 2012).

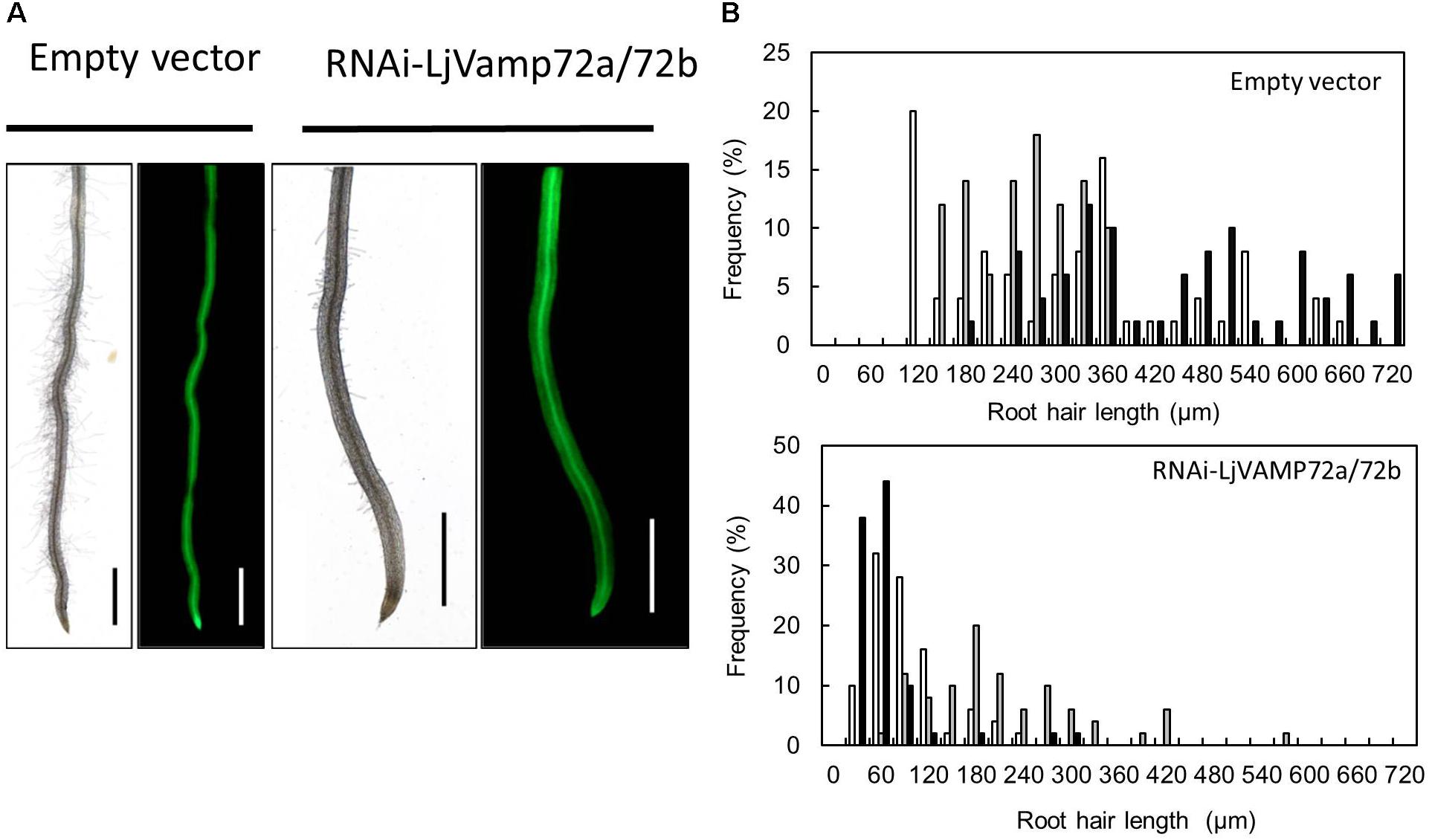

Suppression of LjVAMP72a and LjVAMP72b mRNAs also affected the elongation of root hairs. RNAi-LjVAMP72a/72b knockdown roots exhibited significantly fewer root hairs or almost root hair-less phenotypes (Figure 6), suggesting that LjVAMP72a and LjVAMP72b functioned not only in symbioses but also in the development of root hairs.

Figure 6. LjVAMP72a and LjVAMP72b functioned in the development of root hairs. (A) Transgenic hairy roots expressing either an empty vector or RNAi-LjVAMP72a/72b were subjected to microscopic observation for bright field (left) and GFP fluorescence (right). Scale bars represent 1 mm. (B) Histogram of root hair length in each transgenic hairy root. Upper and lower panels show transgenic lines transformed with empty vector and RNAi-LjVAMP72a/72b, respectively. Different colors indicate independent transgenic hairy roots.

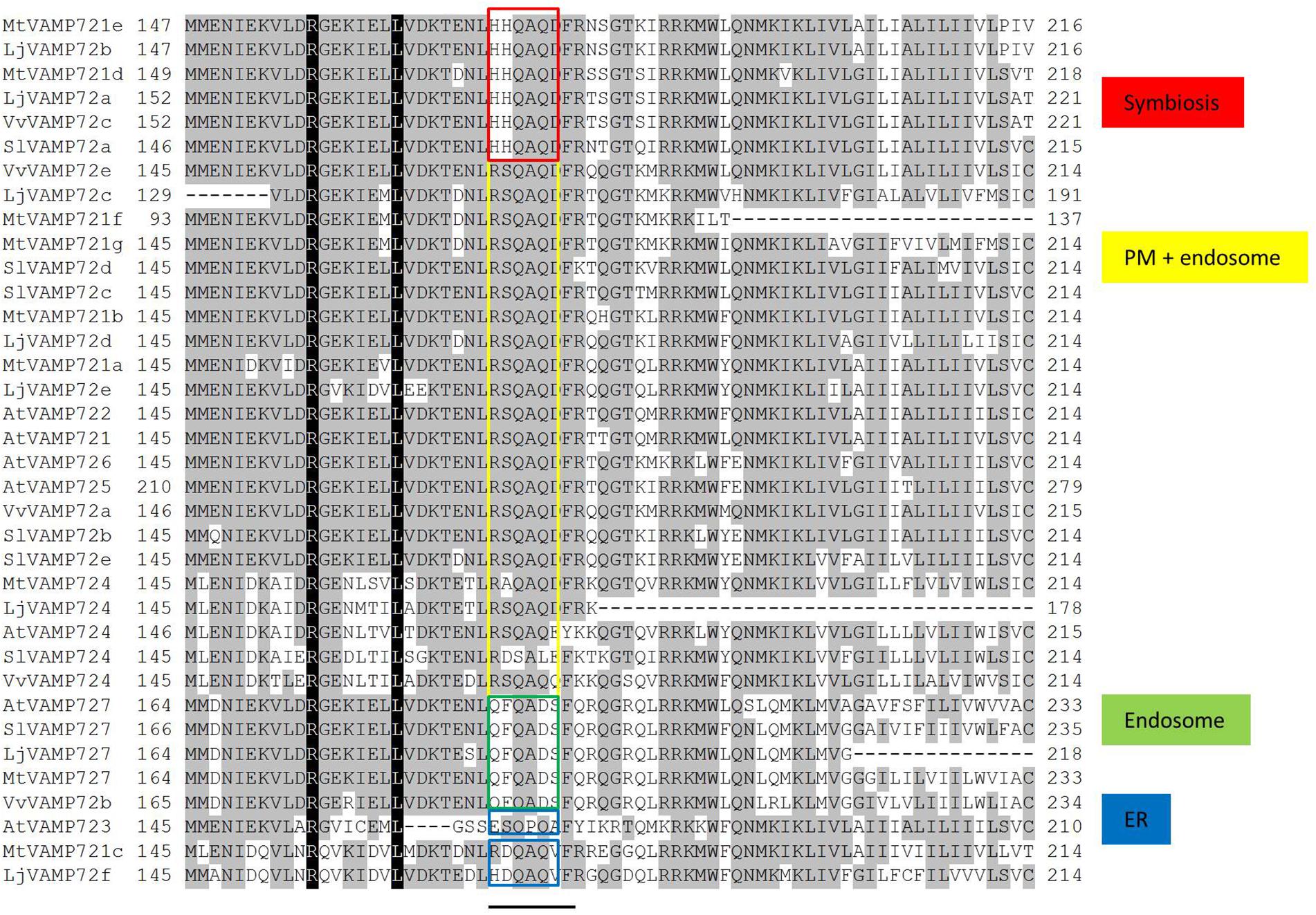

SNARE proteins have a highly conserved coined-coil domain, called a SNARE motif (Harbury, 1998). Uemura et al. (2004) found a six amino acid region that could be classified by its subcellular localization within the SNARE motif. Figure 7 shows the sequence alignment of the VAMP72 groups. The aligned sequences were selected from legume plants, non-legume plants including A. thaliana. The alignment shows that the six amino acid regions (RSQAQD and QFQADS) of VAMP72s in L. japonicus were identical to the AtVAMP72s that localize in plasma membrane and endosome, respectively. These common six amino acid regions were detected in other species: M. truncatula, A. thaliana, S. lycopersicum, and Vitis vulgaris. A different six amino acid region (HHQAQD) was conserved in the “symbiotic” VAMP72 subgroup, including LjVAMP72a and LjVAMP72b (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Sequence alignment of the VAMP72 group in plants. Conserved residues are shaded in black. A bar under the alignment represents the regions of possible localization signals (Uemura et al., 2004). Red boxes are conserved in the symbiotic VAMP72 subgroup.

For membrane trafficking, VAMP72 of R-SNARE is specific to green plants (Sanderfoot, 2007). Based on genome sequence information (Sato et al., 2008), rhizobia-induced LjVAMP72a and LjVAMP72b are classified in the symbiotic VAMP72 subgroup.

The producing knockdown mutant (RNAi-LjVAMP72a/72b) was suppressed both expressions (Figure 5B). In addition, RNS and AM were severely reduced on the LjVAMP72a/72b knockdown roots (Figure 5) and LjVAMP72a and LjVAMP72b were enriched in the symbiosome-containing fraction (Figure 4F), so LjVAMP72a and LjVAMP72b might be involved in the formation of a SM as reported in M. truncatula (Ivanov et al., 2012).

Both LjVAMP72a and LjVAMP72b were expressed in the nodules. The only difference was that the expression level of LjVAMP72a in the nodules was higher than that in the leaves or roots; however, LjVAMP72b was expressed constitutively in the leaves, roots, and nodules (Figure 1). A slight induction of LjVAMP72b appeared in the infected roots at 7 days compared with the non-infected roots. The data suggest that the expression ratio of LjVAMP72a and LjVAMP72b plays a role in forming the infection thread and the following SM. More data is needed to determine the different functions of the two.

Uemura et al. (2004) speculated that the six amino acid region within the SNARE motif differs depending on the subcellular localization in Arabidopsis VAMP72 proteins. From the genome data base, there were eight VAMP 72 genes in L. japonicus (Figure 2). In the alignment analysis (Figure 7), we could speculate the membrane localization of these Vamp72s from six amino acid region within the SNARE motif. Moreover, we found the symbiotic subgroup containing LjVAMP72a and LjVAMP72b conserved a different six amino acid region (HHQAQD). The symbiotic subgroup includes to non-legume genes, such as SlVAMP72a and VvVAMP72c (Figure 2, Ivanov et al., 2012) in S. lycopersicum and V. vulgaris, respectively, indicating that the VAMP72s with the six amino acid region (HHQAQD) is conserved among the R-SNARE for the localization of AM. The development of SM by LjVAMP72a and LjVAMP72b would be recruited during the evolution. The localization of another VAMP72s in L. japonicus (Figure 7) could be speculated from the six amino acid region that of AtVAMP72s localizing in the plasma membrane or endosome, except LjVAMP72f. The LjVAMP72f has a higher similarity to MtVAMP72c; however, there was no conserved amino acid in AtVAM72s of A. thaliana. Future studies may give more insight into the localization of LjVAMP72f.

We also found that LjVAMP72a/72b knockdown roots exhibited impaired root hair elongation (Figure 6), which was not reported in M. truncatula (Ivanov et al., 2012). Root hairs normally emerge at the apical end of root epidermal cells, implying that these cells are polarized because of vesicle targeting (Enami et al., 2009). In Arabidopsis, VAMP721/722/724 localizes in root hairs, and these AtVAMP72s form SNARE complexes with Q-SNARE, SYP123, and SYP132 (Ichikawa et al., 2014). LjVAMP72a and LjVAMP72b belonging to VAMP721 would have dual functions of root hair development and symbiotic membrane formation. Therefore, the Q-SNAREs responsible for root hair development and symbiotic membrane formation need to be confirmed. Taken together, our data suggested that the LjVAMP72a and LjVAMP72b played a role in RNS and AM as well as root hair development. Dual physiological activity of LjVAMP72a and LjVAMP72b likely involves a change in the vesicle cargo during the transition from plant growth to the symbiosis stage.

AS and AY performed most of the experiments and contributed equally. MH and MN designed the experiments. HY, MK, TM, and ST participated in some part of the study.

This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid (Grant No. 25450084, MN) and by the Special Coordination Funds for Promoting Science and Technology from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

We thank Dr. Keisuke Yokota, National Institute of Agrobiological Sciences, Tsukuba, Japan and Dr. Shusei Sato, Tohoku University, Japan for their technical support.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2018.01992/full#supplementary-material

Battenberg, K., Lee, E. K., Chiu, J. C., Berry, A. M., and Potter, D. (2017). OrthoReD: A rapid and accurate orthology prediction tool with low computational requirement. BMC Bioinformatics 18:310. doi: 10.1186/s12859-017-1726-5

Broughton, W. J., and Dilworth, M. J. (1971). Control of leghaemoglobin synthesis in snake beans. Biochem. J. 125, 1075–1080. doi: 10.1042/bj1251075

Carleton College, and The Science Education Resource Center (2010). Genome Explorer. Available at: https://serc.carleton.edu/exploring_genomics/index.html

Dash, S., Cannon, E. K. S., Kalberer, S. R., Farmer, A. D., and Cannon, S. B. (2016). “PeanutBase and other bioinformatic resources for peanut (Chapterb),” in Peanuts Genetics, Processing, and Utilization, eds H. T. Stalker and R. F. Wilson (New York, NY: Elsevier), 241–252.

Day, D., Price, G., and Udvardi, M. (1989). Membrane interface of the Bradyrhizobium japonicum–Glycine max symbiosis: peribacteroid units from soyabean nodules. Aust. J. Plant Physiol. 16:69. doi: 10.1071/PP9890069

Dénarié, J., Debellé, F., and Promé, J.-C. (1996). Rhizobium Lipo-chitooligosaccharide nodulation factors: signaling molecules mediating recognition and morphogenesis. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 65, 503–535. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.002443

Enami, K., Ichikawa, M., Uemura, T., Kutsuna, N., Hasezawa, S., Nakagawa, T., et al. (2009). Differential expression control and polarized distribution of plasma membrane-resident SYP1 SNAREs in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 50, 280–289. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcn197

Galli, T., Zahraoui, A., Vaidyanathan, V. V., Raposo, G., Tian, J. M., Karin, M., et al. (1998). A novel tetanus neurotoxin-insensitive vesicle-associated membrane protein in SNARE complexes of the apical plasma membrane of epithelial cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 9, 1437–1448. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.6.1437

Genre, A., Ivanov, S., Fendrych, M., Faccio, A., Zarsky, V., Bisseling, T., et al. (2012). Multiple exocytotic markers accumulate at the sites of perifungal membrane biogenesis in arbuscular mycorrhizas. Plant Cell Physiol. 53, 244–255. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcr170

Gonzalez, L. C. Jr., Weis, W. I., and Scheller, R. H. (2001). A novel SNARE N-terminal domain revealed by the crystal structure of Sec22b. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 24203–24211. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101584200

Goodstein, D. M., Shu, S., Howson, R., Neupane, R., Hayes, R. D., Fazo, J., et al. (2012). Phytozome: a comparative platform for green plant genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, D1178–D1186. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr944

Hakoyama, T., Oi, R., Hazuma, K., Suga, E., Adachi, Y., Kobayashi, M., et al. (2012). The SNARE protein SYP71 expressed in vascular tissues is involved in symbiotic nitrogen fixation in Lotus japonicus nodules. Plant Physiol. 160, 897–905. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.200782

Handberg, K., and Stougaard, J. (1992). Lotus japonicus, an autogamous, diploid legume species for classical and molecular genetics. Plant J. 2, 487–496. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.1992.00487.x

Harbury, P. A. B. (1998). Springs and zippers: coiled coils in SNARE-mediated membrane fusion. Structure 6, 1487-1491. doi: 10.1016/S0969-2126(98)00147-6

Huisman, R., Hontelez, J., Mysore, K. S., Wen, J., Bisseling, T., and Limpens, E. (2016). A symbiosis-dedicated SYNTAXIN OF PLANTS 13II isoform controls the formation of a stable host-microbe interface in symbiosis. New Phytol. 211, 1338–1351. doi: 10.1111/nph.13973

Ichikawa, M., Hirano, T., Enami, K., Fuselier, T., Kato, N., Kwon, C., et al. (2014). Syntaxin of plant proteins SYP123 and SYP132 mediate root hair tip growth in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 55, 790–800. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcu048

Ivanov, S., Fedorova, E. E., Limpensa, E., Mita, S. D., Genre, A., Bonfante, P., et al. (2012). Rhizobium–legume symbiosis shares an exocytotic pathway required for arbuscule formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 8316–8321. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200407109

Jahn, R., Lang, T., and Sudhof, T. C. (2003). Membrane fusion. Cell 112, 519–533. doi: 10.1016/S0092b674(03)00112-0

Katoh, K., and Standley, D. M. (2013). MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 772–780. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst010

Kouchi, H., Imaizumi-Anraku, H., Hayashi, M., Hakoyama, T., Nakagawa, T., Umehara, Y., et al. (2010). How many peas in a pod? Legume genes responsible for mutualistic symbioses underground. Plant Cell Physiol. 51, 1381–1397. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcq107

Kumagai, H., and Kouchi, H. (2003). Gene silencing by expression of hairpin RNA in Lotus japonicus roots and root nodules. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 16, 663–668. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2003.16b.663

Lowry, O. H., Rosebrough, N. J., Farr, A. L., and Randall, R. J. (1951). Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J. Biol. Chem. 193, 265–275.

Maekawa, T., Maekawa-Yoshikawa, M., Takeda, N., Imaizumi-Anraku, H., Murooka, Y., and Hayashi, M. (2009). Gibberellin controls the nodulation signaling pathway in Lotus japonicus. Plant J. 58, 183–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03774.x

Mai, H. T., Nomura, M., Takegawa, K., Asamizu, E., Sato, S., Kato, T., et al. (2006). Identification of a Sed5-like SNARE gene LjSYP32-1 that contributes to nodule tissue formation of Lotus japonicus. Plant Cell Physiol. 47, 829–838. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcj054

Maillet, F., Poinsot, V., André, O., Puech-Pagès, V., Haouy, A., Gueunier, M., et al. (2011). Fungal lipochitooligosaccharide symbiotic signals in arbuscular mycorrhiza. Nature 469, 58–63. doi: 10.1038/nature09622

Marmagne, A., Rouet, M.-A., Ferro, M., Rolland, N., Alcon, C., Joyard, J., et al. (2004). Identification of new intrinsic proteins in Arabidopsis plasma membrane proteome. Mol. Cell Proteomics 3, 675–691. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M400001-MCP200

McGonigle, T. P., Miller, M. H., Evans, D. G., Fairchild, G. L., and Swan, J. A. (1990). A new method which gives an objective measure of colonization of roots by vesicular—arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. New Phytol. 115, 495–501. doi: 10.1111/j.1469b137.1990.tb00476.x

McNew, J. A., Søgaard, M., Lampen, N. M., Machida, S., Ye, R. R., Lacomis, L., et al. (1997). Ykt6p, a prenylated SNARE essential for endoplasmic reticulum-Golgi transport. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 17776–17783. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.28.17776

Newcomb, W. (1976). A correlated light and electron microscopy study of symbiotic growth and differentiation in Pisum sativum root nodules. Can. J. Bot. 54, 2163–2186. doi: 10.1139/b76-233

Newcomb, W., and McIntyre, L. (1981). Development of root nodules of mung bean (Vigna radiata): a reinvestigation of endocytosis. Can. J. Bot. 59, 2478–2499. doi: 10.1139/b81-299

Niwa, Y., Hirano, T., Yoshimoto, K., Shimizu, M., and Kobayashi, H. (1999). Non-invasive quantitative detection and applications of non-toxic, S65T-type green fluorescent protein in living plants. Plant J. 18, 455–463. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1999.00464.x

Nomura, M., Mai, H. T., Fujii, M., Hata, S., Izui, K., and Tajima, S. (2006). Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase plays a crucial role in limiting nitrogen fixation in lotus japonicus nodules. Plant Cell Physiol. 47, 613–621. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcj028

Oldroyd, G. E. D. (2013). Speak, friend, and enter: signalling systems that promote beneficial symbiotic associations in plants. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 11, 252–263. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2990

Pan, H., Oztas, O., Zhang, X., Wu, X., Stonoha, C., Wang, E., et al. (2016). A symbiotic SNARE protein generated by alternative termination of transcription. Nat. Plants 2:15197. doi: 10.1038/nplants.2015.197

Robertson, J. G., Lyttleton, P., Bullivant, S., and Grayston, G. F. (1978). Membranes in lupin root nodules. I. the role of Golgi bodies in the biogenesis of infection threads and peribacteroid membranes. J. Cell Sci. 30, 129–149.

Roth, L. E., and Stacy, G. (1989). Cytoplasmic membrane systems involved in bacterium release into soybean nodule cells as studied with two Bradyrhizobium japonicum mutant strains. Eur. J. Cell. Biol. 49, 24–32.

Sanderfoot, A. (2007). Increases in the number of SNARE genes parallels the rise of multicellularity among the green plants. Plant Physiol. 144, 6–17. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.092973

Sato, S., Nakamura, Y., Kaneko, T., Asamizu, E., Kato, T., Nakao, M., et al. (2008). Genome structure of the legume, Lotus japonicus. DNA Res. 15, 227–239. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsn008

Shimomura, K., Nomura, M., Tajima, S., and Kouchi, H. (2006). LjnsRING, a novel RING finger protein, is required for symbiotic interactions between Mesorhizobium loti and Lotus japonicus. Plant Cell Physiol. 47, 1572–1581. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcl022

Stamatakis, A. (2006). RAxML-VI-HPC: maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic analyses with thousands of taxa and mixed models. Bioinformatics 22, 2688–2690. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl446

Suganuma, N., Sonoda, N., Nakane, C., Hayashi, K., Hayashi, T., Tamaoki, M., et al. (1998). Bacteroids isolated from infective nodules of Pisum sativum mutant E135 (sym13) lack nitrogenase activity but contain the two protein components of nitrogenase. Plant Cell Physiol. 39, 1093–1098. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pcp.a029307

Suzaki, T., and Kawaguchi, M. (2014). Root nodulation: a developmental program involving cell fate conversion triggered by symbiotic bacterial infection. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 21, 16–22. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2014.06.002

Ueda, T., Yamaguchi, M., Uchimiya, H., and Nakano, A. (2001). Ara6, a plant-unique novel type Rab-GTPase, functions in the endocytic pathway of Arabidopsis thaliana. EMBO J. 20, 4730–4741. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.17.4730

Uemura, T., Ueda, T., Ohniwa, R. L., Nakano, A., Takeyasu, K., and Sato, M. H. (2004). Systematic analysis of SNARE molecules in Arabidopsis: dissection of the post-Golgi network in plant cells. Cell Struct. Funct. 29, 49–65. doi: 10.1247/csf.29.49

Keywords: Lotus japonicus, nitrogen fixation, root hair, SNARE, symbiosis, VAMP72

Citation: Sogawa A, Yamazaki A, Yamasaki H, Komi M, Manabe T, Tajima S, Hayashi M and Nomura M (2019) SNARE Proteins LjVAMP72a and LjVAMP72b Are Required for Root Symbiosis and Root Hair Formation in Lotus japonicus. Front. Plant Sci. 9:1992. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.01992

Received: 13 September 2018; Accepted: 20 December 2018;

Published: 16 January 2019.

Edited by:

Kiwamu Minamisawa, Tohoku University, JapanReviewed by:

Norio Suganuma, Aichi University of Education, JapanCopyright © 2019 Sogawa, Yamazaki, Yamasaki, Komi, Manabe, Tajima, Hayashi and Nomura. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mika Nomura, bm9tdXJhQGFnLmthZ2F3YS11LmFjLmpw

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.