- 1Department of Plant, Soil and Microbial Sciences, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, United States

- 2Department of Plant Biology, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, United States

- 3Plant Resilience Institute, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, United States

- 4AgBioResearch – Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, United States

- 5Department of Genetics, Cell Biology, and Development, Center for Precision Plant Genomics, University of Minnesota, Saint Paul, MN, United States

Genome-editing has revolutionized biology. When coupled with a recently streamlined regulatory process by the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the potential to generate transgene-free varieties, genome-editing provides a new avenue for crop improvement. For heterozygous, polyploid and vegetatively propagated crops such as cultivated potato, Solanum tuberosum Group Tuberosum L., genome-editing presents tremendous opportunities for trait improvement. In potato, traits such as improved resistance to cold-induced sweetening, processing efficiency, herbicide tolerance, modified starch quality and self-incompatibility have been targeted utilizing CRISPR/Cas9 and TALEN reagents in diploid and tetraploid clones. However, limited progress has been made in other such crops including sweetpotato, strawberry, grapes, citrus, banana etc., In this review we summarize the developments in genome-editing platforms, delivery mechanisms applicable to plants and then discuss the recent developments in regulation of genome-edited crops in the United States and The European Union. Next, we provide insight into the challenges of genome-editing in clonally propagated polyploid crops, their current status for trait improvement with future prospects focused on potato, a global food security crop.

Introduction

Genome-editing technologies such as TALENs (Transcription Activator Like Effector Nucleases), CRISPR/Cas9 (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats/CRISPR-associated systems), CRISPR/Cas12a (Cpf1, CRISPR from Prevotella and Francisella 1), and Cas9-derived DNA base editors, provide an unprecedented advancement in genome engineering due to precise DNA manipulation. Genome-editing is being widely applied in plants and has revolutionized crop improvement. Polyploidy and vegetative reproduction are unique to plants, frequently found in a large number of important food crops including root and tuber crops, several perennial fruit crops as well as forage crops (McKey et al., 2010; Gemenet and Khan, 2017). Several cultivated polyploids have vegetative mode of reproduction (Herben et al., 2017) and with allopolyploidy combined with heterozygosity makes breeding challenging in these crops. In order to introduce genetic diversity by crossing two heterozygous parents, multiple alleles segregate at a given locus. Backcrossing techniques to add traits cannot be used because it will destroy the unique gene combination within a preferred variety.

Potato, (Solanum tuberosum Group Tuberosum L.) (2n = 4x = 48) represents one such heterozygous, polyploid crop that is clonally propagated by tubers. Potato is a global food security crop and is the third most important food crop after rice and wheat (Devaux et al., 2014). While conventional breeding and genetic analysis are challenging in cultivated potato due to the above mentioned features, majority of diploid potatoes possess gametophytic self-incompatibility (SI). Historically, conventional breeding has been used to create improved potato cultivars. Yet due to its unique challenges, breeding is inefficient when a large number of agronomic, market quality and resistance traits need to be combined or if novel traits not present in the germplasm bank are wanted. Insertion and expression or silencing of economically important genes is being used to improve potato production and quality traits without impacting optimal allele combinations in current varieties (Diretto et al., 2006, 2007; Rommens et al., 2006; Chi et al., 2014; Clasen et al., 2016; Sun et al., 2016; Andersson et al., 2017; McCue et al., 2018). Genome sequence information coupled with established genetic transformation and regeneration procedures make potato a strong candidate for genetic engineering. In 2017, the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS), the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved Simplot Plant Sciences to commercially release genetically engineered potatoes with reduced bruising and acrylamide content in tubers (Innate potatoes1).

In this review, we describe various genome-editing platforms available for plants, their delivery mechanisms and discuss the recent USDA and the European Union clarifications regarding regulatory aspects of gene-edited crops. Next, we discuss the challenges of genome-editing in clonally propagated polyploid crops and summarize the insights gained from case studies along with future prospects focused on enhancement of potato breeding using this technology.

Genome-Editing – Emerging Technologies for Genetic Manipulation in Plants

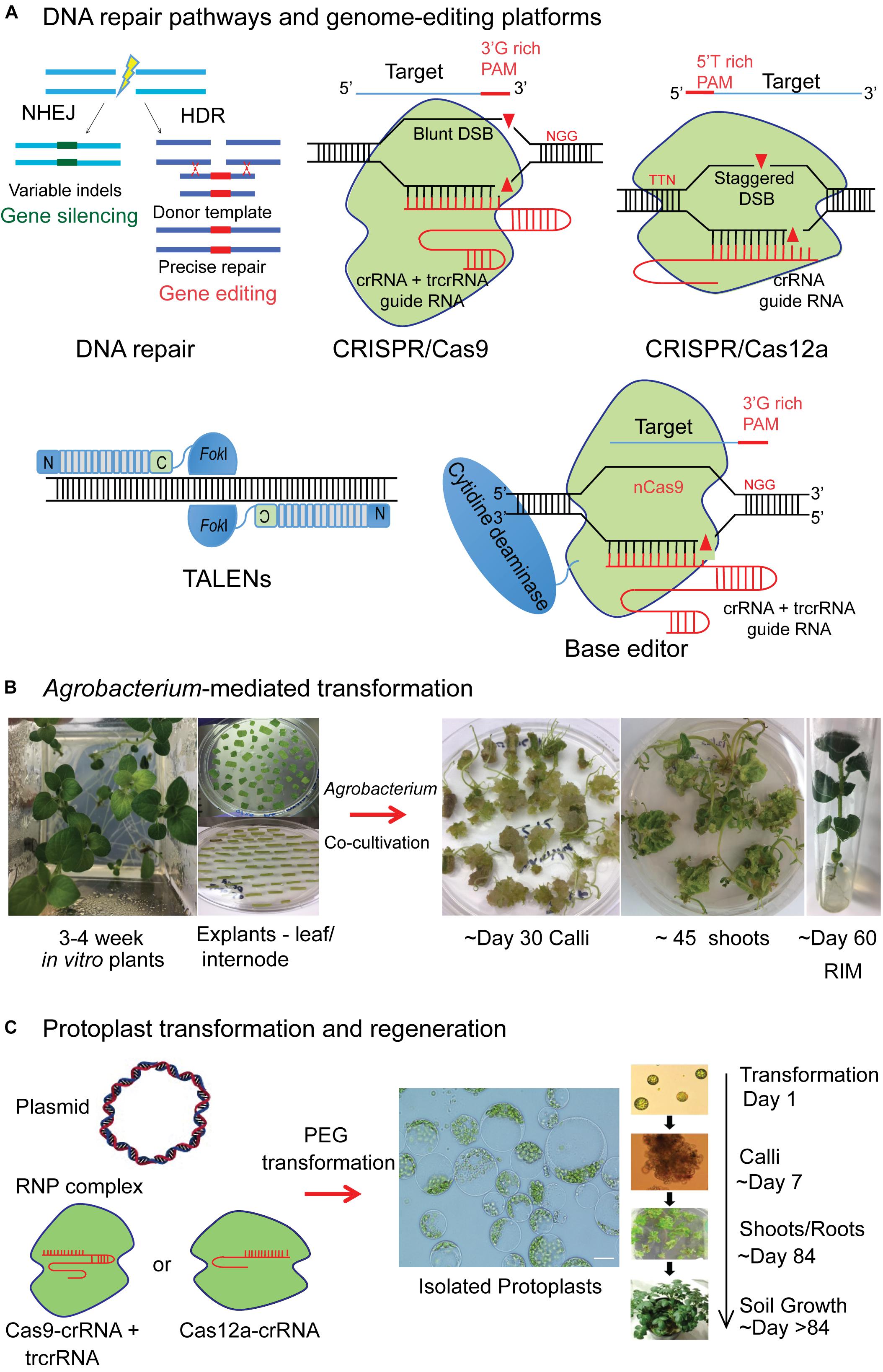

Genome-editing by sequence-specific nucleases (SSNs) such as CRISPR/Cas9 and TALENs facilitate targeted insertion, replacement, or disruption of genes in plants. SSNs create double stranded breaks (DSBs) at the target locus and rely on cellular repair mechanisms to correct these breaks (Figure 1A).

FIGURE 1. Illustration of genome-editing platforms and genetic transformation procedures in potato. (A) Double stranded DNA (dsDNA) break repair in a cell occurs either by non-homologous end joining (NHEJ), where the cleaved DNA molecule is simply rejoined, often with indels in coding regions (green) that result in gene knock-out or by homologous recombination (HR), where a donor repair template (red) can be used for targeted knock-in experiments, where a single or few nucleotides alterations, insertion of an entire transgene or suites of transgenes can be made. CRISPR/Cas9 nuclease engineered to have a Cas9 protein and a guide RNA (gRNA) that is a fusion of CRISPR RNA (crRNA) and trans-activating crRNA (tracrRNA). Cas9 and gRNA complex can recognize and cleave target dsDNA that is complementary to 5′ end of target spacer sequence that is next to protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) of 5′-NGG-3′. CRISPR/Cas12a is a single CRISPR RNA guided nuclease lacking tracrRNA. Cas12a has PAM requirement of “TTTN” allowing targeting of AT rich regions and expanding the target range of RNA-guided genome-editing nucleases. Cas12a cleaves DNA at sites distal to PAM and introduces a staggered DSB with a 4–5-nt 5′ overhang, unlike blunt DSB by Cas9. Transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs) bound to their target site are shown. The TALE array contains repeat variable di-residues that make sequence-specific contact with the target DNA. TALE repeats are fused to FokI, a non-specific nuclease that can cleave the dsDNA upon dimerization. Base editor constitutes fusion of nickase Cas9 (nCas9) with cytidine deaminase enabling the editing of single bases by C→T conversion of single-stranded target. (B) Agrobacterium-mediated plant transformation and regeneration in potato. 3–4-week-old in vitro propagated potato plants in a Magenta box are shown. Ex-plants are prepared from leaf and stem internodes and placed on callus induction media after Agrobacterium inoculation and co-cultivation. Callus growth observed from the ex-plants. After 6–8 weeks, shoots emerge and are grown on shoot induction media. 1–2 cm shoots are excised and transferred to root induction media. The lines that develop roots and have growth on selection media are chosen as candidates for molecular screening to confirm the gene editing events. (C) Delivery of the gene editing reagents as plasmid DNA or as preassembled Cas9 or Cas12a protein-gRNA ribonucleoproteins (RNPs) into protoplasts by polyethylene glycol (PEG) mediated transformation. The timeline from protoplast transformation to regeneration of mutagenized plants in potato is reproduced from Clasen et al. (2016) with the permission of the copyright holder (John Wiley & Sons, Inc.).

The CRISPR/Cas9 system has demonstrated great potential in various crop species due to simplicity of use and versatility of the reagents (Jiang W. et al., 2013; Sun et al., 2015; Svitashev et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2016; Shimatani et al., 2017; Soyk et al., 2017). Engineered CRISPR/Cas9 nucleases target DNA adjacent to the 5′-NGG-3′, protospacer adjacent motif (PAM), in a single guide RNA (sgRNA) specific manner (Jinek et al., 2012; Figure 1A). CRISPR/Cas12a that has PAM requirement of “TTTN”, allowing targeting of AT rich regions, is emerging as equally effective alternative, implemented in various plants (Kim et al., 2017; Tang et al., 2017). For multiplexing, to target more than one gene at a time, Cas12a requires only a single RNA PolIII promoter to drive several crRNAs, whereas Cas9 requires relatively large constructs (Zetsche et al., 2017). In TALENs, the TALE protein is engineered for sequence-specific DNA binding and is fused to a non-sequence-specific FokI nuclease to create a targeted DSB (Bogdanove and Voytas, 2011; Voytas, 2013).

Base-editing technology, based on CRISPR/Cas9 system generates base substitutions without requiring dsDNA cleavage. Cas9 is engineered to retain DNA-binding ability in a sgRNA programmed manner without the nuclease activity such as catalytically inactive Cas9 (dCas9) or a nickase (nCas9) (Jinek et al., 2012). If either dCas9 or nCas9 is fused with a cytidine deaminase that mediates the conversion of cytidine to uridine, the result is a base editor that results in a C→T (or G→A) substitution (Komor et al., 2016; Figure 1A). More recently, adenine base editors have been developed that convert A→G (or T→C) (Gaudelli et al., 2017). Base editing has been successfully applied in plants to confer both gain of function by incorporating correct mutations and loss of function by generating knock-out mutations (Chen et al., 2017; Li et al., 2017; Lu and Zhu, 2017; Shimatani et al., 2017; Zong et al., 2017; Kang et al., 2018).

Delivery of Genome-Editing Nucleases Into Plant Cells

The three major methods of genetic transformation in plants are: Agrobacterium-mediated transformation, biolistics and protoplast transfection. By far the most commonly used method to introduce genome-editing reagents in potato is by Agrobacterium-mediated transformation (Figure 1B). A binary T-DNA vector is used to deliver and express the reagents in plant cells. Once inside the nucleus, the T-DNA randomly integrates into the plant/host genome leading to stable transformation resulting in persistent activity of reagents. However, there is a possibility that it remains extra-chromosomal leading to transient gene expression.

The other common method is polyethylene glycol (PEG)-mediated protoplast transfection. Protoplasts facilitate direct delivery of DNA into cells with gene-editing reagents expressed as plasmid DNA for transient transformation. Protoplasts have greater transformation efficiency compared to other methods (Jiang F. et al., 2013; Dlugosz et al., 2016; Baltes et al., 2017). They retain their cell identity and differentiated state and, for some plant species, have the capability to regenerate into an entire plant.

To improve specificity and to reduce the duration of activity of SSNs in the cell, purified recombinant Cas9 or Cas12a protein with an in vitro transcribed or synthetically produced sgRNA resulting in a ribonucleoprotein complex (RNP) is delivered into protoplasts (Figure 1C). The Cas9 protein continues to be expressed in the cell for several days when delivered as a plasmid, whereas it is degraded within 24 h when delivered as RNPs, improving the specificity of the reagent (Zetsche et al., 2015). Preassembled CRISPR/Cas9 or Cas12a RNP complexes were successfully delivered into protoplasts of Arabidospsis, tobacco, lettuce, rice, wheat, soybean and potato and plants were regenerated with heritable targeted mutagenesis (Woo et al., 2015; Kim et al., 2017; Liang et al., 2017; Andersson et al., 2018). Using RNPs, possibility of integration of plasmid-derived DNA sequences or foreign DNA into the host genome can be eliminated. Plants regenerated from protoplast cells without the integration of any foreign DNA would likely avoid the regulatory process (Haun et al., 2014; Clasen et al., 2016).

Regulatory Aspects on Genome-Edited Crops – Impact on Advancing Crop Improvement

Genome-editing has been successfully implemented in several plant species, and some cases, the regulatory status of the edited plants has been considered by USDA/APHIS (“Am I Regulated?”2 (Waltz, 2018). USDA considers genome-editing as a novel breeding tool and released a definitive statement that if plant varieties developed through genome-editing do not possess any foreign genetic material and they are indistinguishable from those developed by conventional breeding or mutagenesis approaches, then they will not be regulated (USDA press release3). The edits made in edited varieties can include deletions of any length, single base substitutions or genetic variation from any species or variety that is sexually compatible. In the case of Agrobacterium-mediated delivery of SSNs, any stably integrated T-DNA sequences can be segregated away by meiotic recombination. Null segregants – progeny of the transgenic, edited parent that still retain the germline edit but lack the integrated T-DNA or other foreign sequence – are excempt from regulation. In clonally propagated plants like potato, null segregants are difficult or impossible to obtain. However, transient expression in protoplasts, for example, can achieve gene edits, and regeneration of the edited protoplasts can create edited plants without any foreign DNA and hence are exempt from regulation by USDA/APHIS (Clasen et al., 2016) (“Am I Regulated?”2). In Japan, a government panel recently recommended following a regulatory policy similar to that of USDA/APHIS, that gene edited plants in Japan should not be regulated (TheScientist news4).

Clarity on guidelines for regulating gene-edited crops will undoubtedly promote wider use of this technology in the United States. In contrast, the European Union recently declared that plants generated by genome-editing are not exempt from regulation; rather, they must be treated just like transgenic plant lines (Court of Justice of the European Union verdict5). The EU’s argument is that gene editing alters the genetic material in a way that is not natural, and edited plants might have adverse effects on human health and the environment. Unlike the United States, Europe chose a “process-based” approach to regulation, rather than a “product-based” approach. Gene editing could be used to create genetic variation that is identical to that already present in crop varieties grown in Europe; however, it would nonetheless be regulated due to this process-based approach. A “product-based” regulatory policy allows multiple levels of checks and balances. For example, in the United States, the FDA can weigh in on health benefits or concerns of a given crop, and the EPA can weigh in on potential environmental effects of an edited plant variety. The conservative, process-based approach adopted by Europe will likely both slow the development of the technology in European research labs and will also have global ramifications in terms of trade of gene edited commodities.

Genome-Editing Challenges in Clonally Propagated Polyploid Crops – Case Studies in Potato

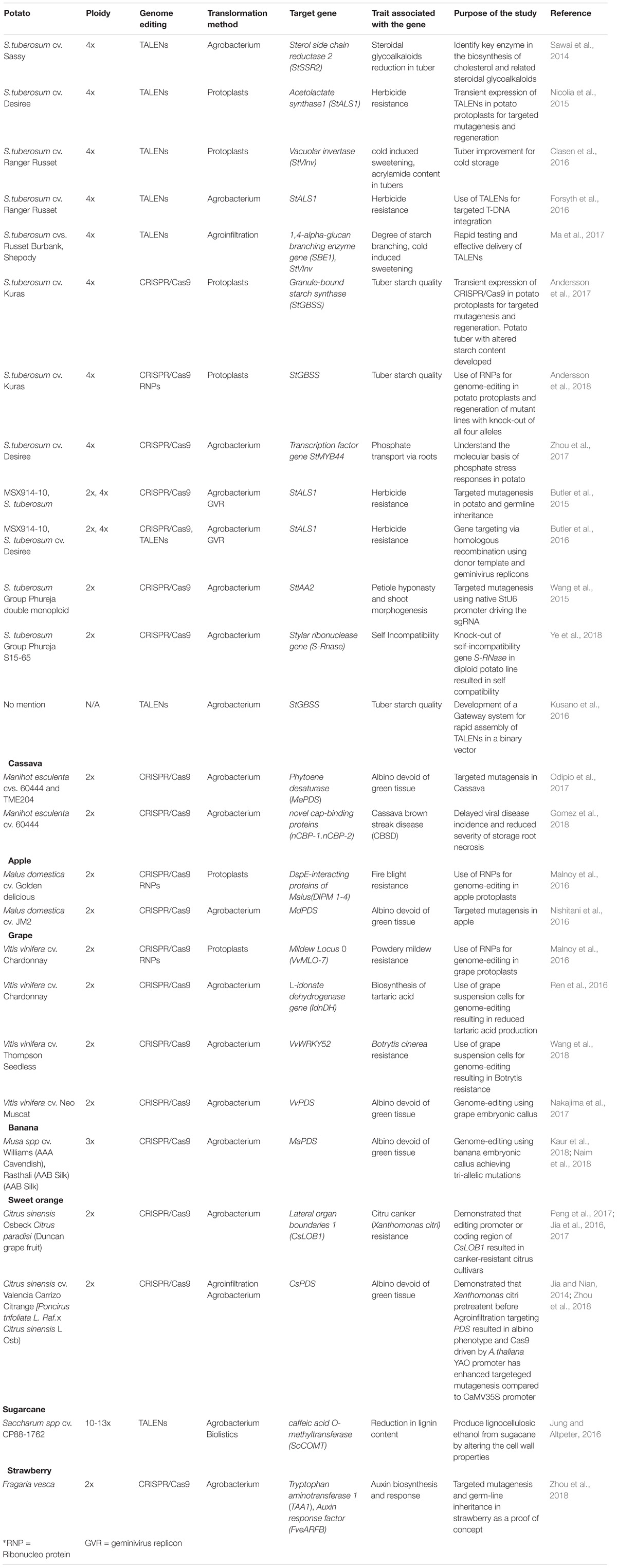

Genome manipulation in polyploid heterozygous crops include the task of simultaneously targeting multiple alleles and screening large number of transformants to recover multiallelic mutagenic lines. Moreover, unlike the seed producing species where Cas9 can be segregated out, it is not feasible in clonally propagated plants. Nevertheless, genome-editing using TALENs and CRISPR/Cas9 has been successfully demonstrated in a number of clonally propagated crops presented in Table 1. Potato is chosen for case studies, since it has been subjected to more genome-editing, even though it is a tetraploid, compared to other crops.

The first successful demonstration of the use of TALENs in a tetraploid potato cultivar was by knocking out all four alleles of Sterol side chain reductase 2 (StSSR2) (Sawai et al., 2014) involved in anti-nutritional sterol glycoalkaloid (SGA) synthesis (Itkin et al., 2011, 2013). Similarly, using CRISPR/Cas9 and TALENs, geminivirus replicon-mediated gene targeting (by HR) was successfully demonstrated in diploid and tetraploid varieties. The endogenous Acetolactate synthase1 (StALS1) gene was modified to incorporate mutations using a donor repair template leading to herbicide tolerance and mutations were shown to be heritable (Butler et al., 2015, 2016). StALS1 was also targeted by TALENs via protoplast transfection and successful regeneration of StALS1 knock-out lines from transformed protoplasts was demonstrated in tetraploid potato (Nicolia et al., 2015). Initial studies in potato mainly constituted proof-of-concept demonstrations of the genome-editing technology.

However, improvement in tuber cold storage quality of a commercial tetraploid cultivar, Ranger Russet, was achieved by targeting Vacuolar invertase (StVlnv) using TALENs via protoplast transformation and regeneration (Clasen et al., 2016). Vlnv enzyme breaks down sucrose to the reducing sugars glucose and fructose in cold-stored potato tubers which form dark-pigmented bitter tasting products when processed at high temperatures (Sowokinos, 2001; Kumar et al., 2004; Matsuura-Endo et al., 2006). In addition, the reducing sugars react with free amino acids via the nonenzymatic Maillard reaction to form acrylamide, a carcinogen (Tareke et al., 2002). Tubers from StVlnv knock-out lines had undetectable levels of reducing sugars, low acrylamide, and made light colored chips along with no foreign DNA in their genome (Clasen et al., 2016). Recently, a waxy potato with altered tuber starch quality was developed by knocking out all four alleles of Granule-bound starch synthase (GBSS) in a tetraploid potato cultivar via CRISPR/Cas9. By transient expression of reagents as plasmid DNA or via RNPs in potato protoplasts, mutagenized lines in all four alleles were regenerated with tubers that had the desired high amylopectin starch (Andersson et al., 2017, 2018).

Furthermore, studies related to technological advances in genome-editing in potato have been reported such as utilizing a native StU6 promoter to drive sgRNA expression, targeted insertion of transgenes, a Gateway system for rapid assembly of TALENs, and delivery of TALENs via agroinfiltration for rapid mutagenesis detection (Wang et al., 2015; Forsyth et al., 2016; Kusano et al., 2016; Ma et al., 2017).

Future Prospects to Enhance Potato Breeding Using Genome-Editing

Genome-editing has tremendous potential for crop improvement, and although implemented in many crops, it has yet to be fully realized in clonally propagated polyploids like potato. Only certain cultivars of potato are amenable to transformation and others need to be tested for transformation and regeneration in tissue culture. Protoplast transformation and regeneration of plants from leaf protoplasts also can lead to somaclonal variation, which may have negative impact(s) on plant development.

In potato, Late blight, caused by fungus Phytophthora infestans, is the most critical problem and threat to global potato production (Fry, 2008; Fisher et al., 2012). Two approaches currently used to combat this disease are fungicide spraying and breeding for disease resistance. Canonical disease resistance genes, R-genes, belong to nucleotide-binding, leucine-rich repeat (NLR) class of intracellular immune receptor proteins that recognize pathogen effectors to initiate defense responses in the plant (El Kasmi and Nishimura, 2016; Jones et al., 2016). Due to continued high rates of evolution of effector proteins, pathogens overcome recognition, thereby limiting the durability of resistance (Raffaele et al., 2010; Dong et al., 2014). Genome-editing by base editors could potentially be applied to engineer potato for late blight resistance by editing the codons encoding specific amino acids in R-genes essential for effector recognition.

Loss of susceptibility is considered as an alternative breeding strategy for durable broad spectrum resistance (Pavan et al., 2009). Silencing of multiple susceptibility genes (S-genes) by RNAi resulted in late blight resistance in potato (Sun et al., 2016). Since RNAi does not always result in a complete knockout, genome-editing could potentially be used to simultaneously knockout genes belonging to the S-locus. Recently, an extracellular surface protein called receptor-like protein ELR (elicitin response) from the wild potato species, S. microdontum, has been reported to recognize an elicitin that is highly conserved in Phytophthora species offering a broad spectrum durable resistance to this pathogen (Du et al., 2015). Introducing both extracellular and intracellular receptors in potato cultivars by genome-editing can aid in attaining durable broad-spectrum resistance for late blight.

Tuber quality traits, such as reduced SGAs or potatoes with reduced bruising, are some of the traits that could be improved using genome-editing. Previously, RNAi silencing of Polyphenol oxidase (PPO) was shown to reduce the browning in tubers due to mechanical damage (Bachem et al., 1994; Coetzer et al., 2001; Arican and Gozukirmizi, 2003). Recently, anti-browning genetically modified apples have been successfully introduced into market developed by RNAi silencing of PPO (Waltz, 2015). Anti-browning mushrooms, developed by targeting PPO using CRISPR/Cas9, are not regulated by the USDA, suggesting that traits created by knocking out genes may have an accelerated path to market (Waltz, 2016, 2018).

Reduction of SGA levels in the tuber is another important breeding objective in potato previously achieved by targeting different genes in SGA biosynthetic pathway (Sawai et al., 2014; Cárdenas et al., 2016; Umemoto et al., 2016; McCue et al., 2018). As per industry standards, total glycoalkaloid content must be less than 20 mg/100 g tuber fresh weight to be released for commercial tuber production. However, SGAs also have positive impact as defensive allelochemicals deterring insect herbivores (Sinden et al., 1980; Sanford et al., 1990, 1997). Therefore, reduction of SGAs in aboveground tissues may deteriorate pathogen resistance (Ginzberg et al., 2009). Studies have shown differential levels of SGA accumulation among plant organs and developmental stages (Valkonen et al., 1996; Eltayeb et al., 1997; Friedman and McDonald, 1997). Although α-chaconine and α-solanine, which constitute >90% of SGAs, are the predominant SGAs found in cultivated potato (Moehs et al., 1997; McCue et al., 2005, 2006, 2007), other novel SGAs are found in various Solanum species (Shakya and Navarre, 2008; Itkin et al., 2013; Cárdenas et al., 2016). For example, in S. chacoense, leptines and leptinines accumulate only in aerial plant organs and are correlated with plant resistance to Colarado potato beetle (Sinden et al., 1980, 1986; Sanford et al., 1990; Mweetwa et al., 2012). Such qualitative differences in SGAs in terms of organ specificity and composition provide opportunities to select specific targets for potato improvement via genome engineering. For example, silencing exclusively tuber expressed members of the SGA biosynthetic pathway or editing specific gene targets expressed in aerial organs can be achieved. The ultimate goal would be to develop new potato cultivars with low SGA levels in tubers while still maintaining high levels in above ground tissues for crop protection.

Breeders are currently working toward re-inventing potato as a diploid crop in order to accelerate progress toward understanding the genetics of complex traits such as yield, quality and drought resistance (Jansky et al., 2016). Genome-editing combined with inbred diploid line development would be a monumental shift in the potential for genetic improvement and opens up possibilities for creating a better potato breeding pipeline. Moving to diploid potatoes enables us to develop hybrids based on selected inbred lines by which we can improve various agronomic traits such as disease resistance and remove compatibility barriers. Genome-editing was successfully applied in diploid potato to overcome gametophytic SI by knocking-out the Stylar ribonuclease gene (S-RNase) (Ye et al., 2018). Self-compatibility allows fixing of gene edits and segregating out any insertions of foreign DNA from the process of transformation by selection in the progeny. Genome-editing will best be applied to potato improvement using diploid F1 hybrids. There is a need for a set of germplasm that is diploid, inbred and self-compatible forming tubers with commercial shape and appearance and high regeneration capability in plant transformation. Although, some existing diploid lines have some of the characteristics, more work is needed to produce germplasm that meets these requirements.

Author Contributions

SN and CB conceived the idea, SN wrote most of the manuscript. DV and SN wrote the regulatory aspects. CB, DD, CS, and DV contributed to part of writing and overall improvement of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Funding

Funding for this study was provided by the Biotechnology Risk Assessment Grant Program competitive grant no. 2013-33522-21090 from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture and the Agricultural Research Service.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

- ^ http://www.innatepotatoes.com/newsroom/press-releases

- ^ https://www.aphis.usda.gov/aphis/ourfocus/biotechnology/am-i-regulated

- ^ https://www.usda.gov/media/press-releases/2018/03/28/secretary-perdue-issues-usda-statement-plant-breeding-innovation

- ^ https://www.the-scientist.com/news-opinion/japanese-authorities-recommend-not-regulating-gene-editing-64675

- ^ http://curia.europa.eu/juris/celex.jsf?celex=62016CJ0528&lang1=en&type=TXT&ancre=

References

Andersson, M., Turesson, H., Nicolia, A., Fält, A. S., Samuelsson, M., and Hofvander, P. (2017). Efficient targeted multiallelic mutagenesis in tetraploid potato (Solanum tuberosum) by transient CRISPR-Cas9 expression in protoplasts. Plant Cell Rep. 36, 117–128. doi: 10.1007/s00299-016-2062-3

Andersson, M., Turesson, H., Olsson, N., Fält, A. S., Olsson, P., Gonzalez, M. N., et al. (2018). Genome editing in potato via CRISPR-Cas9 ribonucleoprotein delivery. Physiol. Plant doi:10.1111/ppl.12731 [Epub ahead of print].

Arican, E., and Gozukirmizi, N. (2003). Reduced polyphenol oxidase activity in transgenic potato plants associated with reduced wound-inducible browning phenotypes. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2818, 15–21. doi: 10.1080/13102818.2003.10817052

Bachem, C. W. B., Speckmann, G. J., Van der Linde Piet, C. G., Verheggen, F. T. M., Hunt, M. D., Steffens, J. C., et al. (1994). Antisense expression of polyphenol oxidase genes inhibits enzymatic browning in potato tubers. Nat. Biotechnol. 12, 1101–1105. doi: 10.1038/nbt1194-1101

Baltes, N. J., Gil-Humanes, J., and Voytas, D. F. (2017). “Genome engineering and agriculture: opportunities and challenges,” in Gene Editing in Plants Progress in Molecular Biology and Translational Science, eds D. P. Weeks and B. Yang (Cambridge, MA: Academic Press), 1–26. doi: 10.1016/bs.pmbts.2017.03.011

Bogdanove, A. J., and Voytas, D. F. (2011). TAL effectors: customizable proteins for DNA targeting. Science 333, 1843–1846. doi: 10.1126/science.1204094

Butler, N. M., Atkins, P. A., Voytas, D. F., and Douches, D. S. (2015). Generation and inheritance of targeted mutations in potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) using the CRISPR/Cas system. PLoS One 10:e0144591∗. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0144591

Butler, N. M., Baltes, N. J., Voytas, D. F., and Douches, D. S. (2016). Geminivirus-mediated genome editing in potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) using sequence-specific nucleases. Front. Plant Sci. 7:1045. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01045

Cárdenas, P. D., Sonawane, P. D., Pollier, J., Vanden Bossche, R., Dewangan, V., Weithorn, E., et al. (2016). GAME9 regulates the biosynthesis of steroidal alkaloids and upstream isoprenoids in the plant mevalonate pathway. Nat. Commun. 7:10654. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10654

Chen, Y., Wang, Z., Ni, H., Xu, Y., Chen, Q., and Jiang, L. (2017). CRISPR/Cas9-mediated base-editing system efficiently generates gain-of-function mutations in Arabidopsis. Sci. China Life Sci. 60, 520–523. doi: 10.1007/s11427-017-9021-5

Chi, M., Bhagwat, B., Lane, W., Tang, G., Su, Y., Sun, R., et al. (2014). Reduced polyphenol oxidase gene expression and enzymatic browning in potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) with artificial microRNAs. BMC Plant Biol. 14:62. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-14-62

Clasen, B. M., Stoddard, T. J., Luo, S., Demorest, Z. L., Li, J., Cedrone, F., et al. (2016). Improving cold storage and processing traits in potato through targeted gene knockout. Plant Biotechnol. J. 14, 169–176. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12370

Coetzer, C., Corsini, D., Love, S., Pavek, J., and Turner, N. (2001). Control of enzymatic browning in potato (solanum tuberosum L.) by sense and antisense RNA from tomato polyphenol oxidase. J. Agric. Food Chem. 49, 652–657. doi: 10.1021/jf001217f

Devaux, A., Kromann, P., and Ortiz, O. (2014). Potatoes for sustainable global food security. Potato Res. 57, 185–199. doi: 10.1007/s11540-014-9265-1

Diretto, G., Tavazza, R., Welsch, R., Pizzichini, D., Mourgues, F., Papacchioli, V., et al. (2006). Metabolic engineering of potato tuber carotenoids through tuber-specific silencing of lycopene epsilon cyclase. BMC Plant Biol. 6:13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-6-13

Diretto, G., Welsch, R., Tavazza, R., Mourgues, F., Pizzichini, D., Beyer, P., et al. (2007). Silencing of beta-carotene hydroxylase increases total carotenoid and beta-carotene levels in potato tubers. BMC Plant Biol. 7:11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-7-11

Dlugosz, E. M., Lenaghan, S. C., and Stewart, C. N. (2016). A robotic platform for high-throughput protoplast isolation and transformation. J. Vis. Exp. 115:e54300. doi: 10.3791/54300

Dong, S., Stam, R., Cano, L. M., Song, J., Sklenar, J., Yoshida, K., et al. (2014). Effector specialization in a lineage of the Irish potato famine pathogen. Science 343, 552–555. doi: 10.1126/science.1246300

Du, J., Verzaux, E., Chaparro-Garcia, A., Bijsterbosch, G., Keizer, L. C. P., Zhou, J., et al. (2015). Elicitin recognition confers enhanced resistance to Phytophthora infestans in potato. Nat. Plants 1:15034. doi: 10.1038/NPLANTS.2015.34

El Kasmi, F., and Nishimura, M. T. (2016). Structural insights into plant NLR immune receptor function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 113, 12619–12621. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1615933113

Eltayeb, E. A., Al-Ansari, A. S., and Roddick, J. G. (1997). Changes in the steroidal alkaloid solasodine during development of Solanum nigrum and Solanum incanum. Phytochemistry 46, 489–494. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(97)00323-3

Fisher, M. C., Henk, D. A., Briggs, C. J., Brownstein, J. S., Madoff, L. C., McCraw, S. L., et al. (2012). Emerging fungal threats to animal, plant and ecosystem health. Nature 484, 186–194. doi: 10.1038/nature10947

Forsyth, A., Weeks, T., Richael, C., and Duan, H. (2016). Transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALEN)-mediated targeted DNA insertion in potato plants. Front. Plant Sci. 7:1572. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01572

Friedman, M., and McDonald, G. M. (1997). Potato glycoalkaloids: chemistry, analysis, safety, and plant physiology. CRC. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 16, 55–132. doi: 10.1080/07352689709701946

Fry, W. (2008). Phytophthora infestans: the plant (and R gene) destroyer. Mol. Plant Pathol. 9, 385–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2007.00465.x

Gaudelli, N. M., Komor, A. C., Rees, H. A., Packer, M. S., Badran, A. H., Bryson, D. I., et al. (2017). Programmable base editing of A∗T to G∗C in genomic DNA without DNA cleavage. Nature 551, 464–471. doi: 10.1038/nature24644

Gemenet, D. C., and Khan, A. (2017). “Opportunities and challenges to implementing genomic selection in clonally propagated crops,” in Genomic Selection for Crop Improvement: New Molecular Breeding Strategies for Crop Improvement, eds R. K. Varshney, M. Roorkiwal, and M. E. Sorrells (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 185–198. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-63170-7-8

Ginzberg, I., Tokuhisa, J. G., and Veilleux, R. E. (2009). Potato steroidal glycoalkaloids: biosynthesis and genetic manipulation. Potato Res. 52, 1–15. doi: 10.1007/s11540-008-9103-4

Gomez, M. A., Lin, Z. D., Moll, T., Chauhan, R. D., Hayden, L., Renninger, K., et al. (2018). Simultaneous CRISPR/Cas9-mediated editing of cassava eIF4E isoforms nCBP-1 and nCBP-2 reduces cassava brown streak disease symptom severity and incidence. Plant Biotechnol. J. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12987 [Epub ahead of print].

Haun, W., Coffman, A., Clasen, B. M., Demorest, Z. L., Lowy, A., Ray, E., et al. (2014). Improved soybean oil quality by targeted mutagenesis of the fatty acid desaturase 2 gene family. Plant Biotechnol. J. 12, 934–940. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12201

Herben, T., Suda, J., and Klimešová, J. (2017). Polyploid species rely on vegetative reproduction more than diploids: a re-examination of the old hypothesis. Ann. Bot. 120, 341–349. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcx009

Itkin, M., Heinig, U., Tzfadia, O., Bhide, A. J., Shinde, B., Cardenas, P. D., et al. (2013). Biosynthesis of antinutritional alkaloids in solanaceous crops is mediated by clustered genes. Science 341, 175–179. doi: 10.1126/science.1240230

Itkin, M., Rogachev, I., Alkan, N., Rosenberg, T., Malitsky, S., Masini, L., et al. (2011). GLYCOALKALOID METABOLISM1 is required for steroidal alkaloid glycosylation and prevention of phytotoxicity in tomato. Plant Cell 23, 4507–4525. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.088732

Jansky, S. H., Charkowski, A. O., Douches, D. S., Gusmini, G., Richael, C., Bethke, P. C., et al. (2016). Reinventing potato as a diploid inbred line-based crop. Crop Sci. 56, 1412–1422. doi: 10.2135/cropsci2015.12.0740

Jia, H., and Nian, W. (2014). Targeted genome editing of sweet orange using Cas9/sgRNA. PLoS One 9:e93806. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0093806

Jia, H., Orbović, V., Jones, J. B., and Wang, N. (2016). Modification of the PthA4 effector binding elements in Type I CsLOB1 promoter using Cas9/sgRNA to produce transgenic Duncan grapefruit alleviating XccΔpthA4:DCsLOB1.3 infection. Plant Biotechnol. J. 14, 1291–1301. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12495

Jia, H., Zhang, Y., Orbović, V., Xu, J., White, F. F., Jones, J. B., et al. (2017). Genome editing of the disease susceptibility gene CsLOB1 in citrus confers resistance to citrus canker. Plant Biotechnol. J. 15, 817–823. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12677

Jiang, F., Zhu, J., and Liu, H. L. (2013). Protoplasts: a useful research system for plant cell biology, especially dedifferentiation. Protoplasma 250, 1231–1238. doi: 10.1007/s00709-013-0513-z

Jiang, W., Zhou, H., Bi, H., Fromm, M., Yang, B., and Weeks, D. P. (2013). Demonstration of CRISPR/Cas9/sgRNA-mediated targeted gene modification in Arabidopsis, tobacco, sorghum and rice. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, 1–12. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt780

Jinek, M., Chylinski, K., Fonfara, I., Hauer, M., Doudna, J. A., and Charpentier, E. (2012). A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science 337, 816–821. doi: 10.1126/science.1225829

Jones, J. D., Vance, R. E., and Dangl, J. L. (2016). Intracellular innate immune surveillance devices in plants and animals. Science 354:aaf6395. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf6395

Jung, J. H., and Altpeter, F. (2016). TALEN mediated targeted mutagenesis of the caffeic acid O-methyltransferase in highly polyploid sugarcane improves cell wall composition for production of bioethanol. Plant Mol. Biol. 92, 131–142. doi: 10.1007/s11103-016-0499-y

Kang, B.-C., Yun, J.-Y., Kim, S.-T., Shin, Y., Ryu, J., Choi, M., et al. (2018). Precision genome engineering through adenine base editing in plants. Nat. Plants 4, 427–431. doi: 10.1038/s41477-018-0178-x

Kaur, N., Alok, A., Shivani, Kaur, N., Pandey, P., Awasthi, P., et al. (2018). CRISPR/Cas9-mediated efficient editing in phytoene desaturase (PDS) demonstrates precise manipulation in banana cv. Rasthali genome. Funct. Integr. Genomics 18, 89–99. doi: 10.1007/s10142-017-0577-5

Kim, H., Kim, S. T., Ryu, J., Kang, B. C., Kim, J. S., and Kim, S. G. (2017). CRISPR/Cpf1-mediated DNA-free plant genome editing. Nat. Commun. 8:14406. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14406

Komor, A. C., Kim, Y. B., Packer, M. S., Zuris, J. A., and Liu, D. R. (2016). Programmable editing of a target base in genomic DNA without double-stranded DNA cleavage. Nature 533, 420–424. doi: 10.1038/nature17946

Kumar, D., Singh, B. P., and Kumar, P. (2004). An overview of the factors affecting sugar content of potatoes. Ann. Appl. Biol. 145, 247–256. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7348.2004.tb00380.x

Kusano, H., Onodera, H., Kihira, M., Aoki, H., Matsuzaki, H., and Shimada, H. (2016). A simple gateway-assisted construction system of TALEN genes for plant genome editing. Sci. Rep. 6:30234. doi: 10.1038/srep30234

Li, J., Sun, Y., Du, J., Zhao, Y., and Xia, L. (2017). Generation of targeted point mutations in rice by a modified CRISPR/Cas9 system. Mol. Plant 10, 526–529. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2016.12.001

Liang, Z., Chen, K., Li, T., Zhang, Y., Wang, Y., Zhao, Q., et al. (2017). Efficient DNA-free genome editing of bread wheat using CRISPR/Cas9 ribonucleoprotein complexes. Nat. Commun. 8, 1–5. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14261

Lu, Y., and Zhu, J. K. (2017). Precise editing of a target base in the rice genome using a modified CRISPR/Cas9 system. Mol. Plant 10, 523–525. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2016.11.013

Ma, J., Xiang, H., Donnelly, D. J., Meng, F. R., Xu, H., Durnford, D., et al. (2017). Genome editing in potato plants by agrobacterium-mediated transient expression of transcription activator-like effector nucleases. Plant Biotechnol. Rep. 11, 249–258. doi: 10.1007/s11816-017-0448-5

Malnoy, M., Viola, R., Jung, M.-H., Koo, O.-J., Kim, S., Kim, J.-S., et al. (2016). DNA-free genetically edited grapevine and apple protoplast using CRISPR/Cas9 ribonucleoproteins. Front. Plant Sci. 7:1904. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01904

Matsuura-Endo, C., Ohara-Takada, A., Chuda, Y., Ono, H., Yada, H., Yoshida, M., et al. (2006). Effects of storage temperature on the contents of sugars and free amino acids in tubers from different potato cultivars and acrylamide in chips. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 70, 1173–1180. doi: 10.1271/bbb.70.1173

McCue, K. F., Allen, P. V., Shepherd, L. V. T., Blake, A., Malendia Maccree, M., Rockhold, D. R., et al. (2007). Potato glycosterol rhamnosyltransferase, the terminal step in triose side-chain biosynthesis. Phytochemistry 68, 327–334. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2006.10.025

McCue, K. F., Allen, P. V., Shepherd, L. V. T., Blake, A., Whitworth, J., Maccree, M. M., et al. (2006). The primary in vivo steroidal alkaloid glucosyltransferase from potato. Phytochemistry 67, 1590–1597. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2005.09.037

McCue, K. F., Breksa, A., Vilches, A., and Belknap, W. R. (2018). Modification of potato steroidal glycoalkaloids with silencing RNA constructs. Am. J. Potato Res. 95:317. doi: 10.1007/s12230-018-9658-9

McCue, K. F., Shepherd, L. V. T., Allen, P. V., MacCree, M. M., Rockhold, D. R., Corsini, D. L., et al. (2005). Metabolic compensation of steroidal glycoalkaloid biosynthesis in transgenic potato tubers: using reverse genetics to confirm the in vivo enzyme function of a steroidal alkaloid galactosyltransferase. Plant Sci. 168, 267–273. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2004.08.006

McKey, D., Elias, M., Pujol, M. E., and Duputié, A. (2010). The evolutionary ecology of clonally propagated domesticated plants. New Phytol. 186, 318–332. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03210.x

Moehs, C. P., Allen, P. V., Friedman, M., and Belknap, W. R. (1997). Cloning and expression of solanidine UDP-glucose glucosyltransferase from potato. Plant J. 11, 227–236. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1997.11020227.x

Mweetwa, A. M., Hunter, D., Poe, R., Harich, K. C., Ginzberg, I., Veilleux, R. E., et al. (2012). Steroidal glycoalkaloids in Solanum chacoense. Phytochemistry 75, 32–40. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2011.12.003

Naim, F., Dugdale, B., Kleidon, J., Brinin, A., Shand, K., Waterhouse, P., et al. (2018). Gene editing the phytoene desaturase alleles of Cavendish banana using CRISPR/Cas9. Transgenic Res. doi: 10.1007/s11248-018-0083-0 [Epub ahead of print].

Nakajima, I., Ban, Y., Azuma, A., Onoue, N., Moriguchi, T., Yamamoto, T., et al. (2017). CRISPR/Cas9-mediated targeted mutagenesis in grape. PLoS One 12:e0177966. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0177966

Nicolia, A., Proux-Wéra, E., Åhman, I., Onkokesung, N., Andersson, M., Andreasson, E., et al. (2015). Targeted gene mutation in tetraploid potato through transient TALEN expression in protoplasts. J. Biotechnol. 204, 17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2015.03.021

Nishitani, C., Hirai, N., Komori, S., Wada, M., Okada, K., Osakabe, K., et al. (2016). Efficient genome editing in apple using a CRISPR/Cas9 system. Sci. Rep. 6:31481. doi: 10.1038/srep31481

Odipio, J., Alicai, T., Ingelbrecht, I., Nusinow, D. A., Bart, R., and Taylor, N. J. (2017). Efficient CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing of Phytoene desaturase in cassava. Front. Plant Sci. 8:1780. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.01780

Pavan, S., Jacobsen, E., Visser, R. G. F., and Bai, Y. (2009). Loss of susceptibility as a novel breeding strategy for durable and broad-spectrum resistance. Mol. Breed. 25:1. doi: 10.1007/s11032-009-9323-6

Peng, A., Chen, S., Lei, T., Xu, L., He, Y., Wu, L., et al. (2017). Engineering canker-resistant plants through CRISPR/Cas9-targeted editing of the susceptibility gene CsLOB1 promoter in citrus. Plant Biotechnol. J. 15, 1509–1519. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12733

Raffaele, S., Farrer, R. A., Cano, L. M., Studholme, D. J., MacLean, D., Thines, M., et al. (2010). Genome evolution following host jumps in the Irish potato famine pathogen lineage. Science 330, 1540–1543. doi: 10.1126/science.1193070

Ren, C., Liu, X., Zhang, Z., Wang, Y., Duan, W., Li, S., et al. (2016). CRISPR/Cas9-mediated efficient targeted mutagenesis in Chardonnay (Vitis vinifera L.). Sci. Rep. 6:32289. doi: 10.1038/srep32289

Rommens, C. M., Ye, J., Richael, C., and Swords, K. (2006). Improving potato storage and processing characteristics through all-native DNA transformation. J. Agric. Food Chem. 54, 9882–9887. doi: 10.1021/jf062477l

Sanford, L. L., Deahl, K. L., Sinden, S. L., and Ladd, T. L. (1990). Foliar solanidine glycoside levels in Solanum tuberosum populations selected for potato leafhopper resistance. Am. Potato J. 67, 461–466. doi: 10.1007/BF03044513

Sanford, L. L., Kobayashi, R. S., Deahl, K. L., and Sinden, S. L. (1997). Diploid and tetraploid Solanum chacoense genotypes that synthesize leptine glycoalkaloids and deter feeding by Colorado potato beetle. Am. Potato J. 74, 15–21. doi: 10.1007/BF02849168

Sawai, S., Ohyama, K., Yasumoto, S., Seki, H., Sakuma, T., Yamamoto, T., et al. (2014). Sterol side chain reductase 2 is a key enzyme in the biosynthesis of cholesterol, the common precursor of toxic steroidal glycoalkaloids in potato. Plant Cell 26, 3763–3774. doi: 10.1105/tpc.114.130096

Shakya, R., and Navarre, D. A. (2008). LC-MS analysis of solanidane glycoalkaloid diversity among tubers of four wild potato species and three cultivars (Solanum tuberosum). J. Agric. Food Chem. 56, 6949–6958. doi: 10.1021/jf8006618

Shimatani, Z., Kashojiya, S., Takayama, M., Terada, R., Arazoe, T., Ishii, H., et al. (2017). Targeted base editing in rice and tomato using a CRISPR-Cas9 cytidine deaminase fusion. Nat. Biotechnol. 35, 441–443. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3833

Sinden, S. L., Sanford, L. L., and Deahl, K. L. (1986). Segregation of leptine glycoalkaloids in Solanum chacoense Bitter. J. Agric. Food Chem. 34, 372–377. doi: 10.1021/jf00068a056

Sinden, S. L., Sanford, L. L., and Osman, S. F. (1980). Glycoalkaloids and resistance to the Colorado potato beetle in Solanum chacoense Bitter. Am. Potato J. 57, 331–343. doi: 10.1007/BF02854028

Sowokinos, J. R. (2001). Biochemical and molecular control of cold-induced sweetening in potatoes. Am. J. Potato Res. 78, 221–236. doi: 10.1007/BF02883548

Soyk, S., Müller, N. A., Park, S. J., Schmalenbach, I., Jiang, K., Hayama, R., et al. (2017). Variation in the flowering gene SELF PRUNING 5G promotes day-neutrality and early yield in tomato. Nat. Genet. 49, 162–168. doi: 10.1038/ng.3733

Sun, K., Wolters, A. M., Vossen, J. H., Rouwet, M. E., Loonen, A. E., Jacobsen, E., et al. (2016). Silencing of six susceptibility genes results in potato late blight resistance. Transgenic Res. 25, 731–742. doi: 10.1007/s11248-016-9964-2

Sun, X., Hu, Z., Chen, R., Jiang, Q., Song, G., Zhang, H., et al. (2015). Targeted mutagenesis in soybean using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Sci. Rep. 5:10342. doi: 10.1038/srep10342

Svitashev, S., Schwartz, C., Lenderts, B., Young, J. K., and Mark Cigan, A. (2016). Genome editing in maize directed by CRISPR-Cas9 ribonucleoprotein complexes. Nat. Commun. 7, 1–7. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13274

Tang, X., Lowder, L. G., Zhang, T., Malzahn, A. A., Zheng, X., Voytas, D. F., et al. (2017). A CRISPR-Cpf1 system for efficient genome editing and transcriptional repression in plants. Nat. Plants 3:17018. doi: 10.1038/nplants.2017.18

Tareke, E., Rydberg, P., Karlsson, P., Eriksson, S., and Törnqvist, M. (2002). Analysis of acrylamide, a carcinogen formed in heated foodstuffs. J. Agric. Food Chem. 50, 4998–5006. doi: 10.1021/jf020302f

Umemoto, N., Nakayasu, M., Ohyama, K., Yotsu-Yamashita, M., Mizutani, M., Seki, H., et al. (2016). Two cytochrome P450 monooxygenases catalyze early hydroxylation steps in the potato steroid glycoalkaloid biosynthetic pathway. Plant Physiol. 171, 2458–2467. doi: 10.1104/pp.16.00137

Valkonen, J. P. T., Keskitalo, M., Vasara, T., Pietilä, L., and Raman, D. K. V. (1996). Potato glycoalkaloids: a burden or a blessing? CRC. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 15, 1–20. doi: 10.1080/07352689609701934

Voytas, D. F. (2013). Plant genome engineering with sequence-specific nucleases. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 64, 327–350. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042811-105552

Waltz, E. (2015). Nonbrowning GM apple cleared for market. Nat. Biotechnol. 33, 326–327. doi: 10.1038/nbt0415-326c

Waltz, E. (2016). Gene-edited CRISPR mushroom escapes US regulation. Nature 532:293. doi: 10.1038/nature.2016.19754

Waltz, E. (2018). With a free pass, CRISPR-edited plants reach market in record time. Nat. Biotechnol. 36, 2017–2018. doi: 10.1038/nbt0118-6b

Wang, S., Zhang, S., Wang, W., Xiong, X., Meng, F., and Cui, X. (2015). Efficient targeted mutagenesis in potato by the CRISPR/Cas9 system. Plant Cell Rep. 34, 1473–1476. doi: 10.1007/s00299-015-1816-7

Wang, X., Tu, M., Wang, D., Liu, J., Li, Y., Li, Z., et al. (2018). CRISPR/Cas9-mediated efficient targeted mutagenesis in grape in the first generation. Plant Biotechnol. J. 16, 844–855. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12832

Woo, J. W., Kim, J., Kwon, S. I., Corvalán, C., Cho, S. W., Kim, H., et al. (2015). DNA-free genome editing in plants with preassembled CRISPR-Cas9 ribonucleoproteins. Nat. Biotechnol. 33, 1162–1164. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3389

Ye, M., Peng, Z., Tang, D., Yang, Z., Li, D., Xu, Y., et al. (2018). Generation of self-compatible diploid potato by knockout of S-RNase. Nat. Plants. 4, 651–654. doi: 10.1038/s41477-018-0218-6

Zetsche, B., Gootenberg, J. S., Abudayyeh, O. O., Slaymaker, I. M., Makarova, K. S., Essletzbichler, P., et al. (2015). Cpf1 is a single RNA-guided endonuclease of a class 2 CRISPR-Cas system. Cell 163, 759–771. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.09.038

Zetsche, B., Heidenreich, M., Mohanraju, P., Fedorova, I., Kneppers, J., Degennaro, E. M., et al. (2017). Multiplex gene editing by CRISPR-Cpf1 using a single crRNA array. Nat. Biotechnol. 35, 31–34. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3737

Zhang, F., LeBlanc, C., Irish, V. F., and Jacob, Y. (2017). Rapid and efficient CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing in Citrus using the YAO promoter. Plant Cell Rep. 36, 1883–1887. doi: 10.1007/s00299-017-2202-4

Zhang, Y., Liang, Z., Zong, Y., Wang, Y., Liu, J., Chen, K., et al. (2016). Efficient and transgene-free genome editing in wheat through transient expression of CRISPR/Cas9 DNA or RNA. Nat. Commun. 7, 1–8. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12617

Zhou, J., Wang, G., and Liu, Z. (2018). Efficient genome editing of wild strawberry genes, vector development and validation. Plant Biotechnol. J. 16, 1868–1877. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12922

Zhou, X., Zha, M., Huang, J., Li, L., Imran, M., and Zhang, C. (2017). StMYB44 negatively regulates phosphate transport by suppressing expression of PHOSPHATE1 in potato. J. Exp. Bot. 68, 1265–1281. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erx026

Keywords: genome-editing, clonal propagation, polyploidy, potato (Solanum tuberosum), CRISPR/Cas system, TALENs, Agrobacterium-mediated transformation, protoplast transformation

Citation: Nadakuduti SS, Buell CR, Voytas DF, Starker CG and Douches DS (2018) Genome Editing for Crop Improvement – Applications in Clonally Propagated Polyploids With a Focus on Potato (Solanum tuberosum L.). Front. Plant Sci. 9:1607. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.01607

Received: 10 September 2018; Accepted: 17 October 2018;

Published: 13 November 2018.

Edited by:

Joachim Hermann Schiemann, Julius Kühn-Institut, GermanyReviewed by:

Frank Hartung, Julius Kühn-Institut, GermanyThomas Debener, Leibniz Universität Hannover, Germany

Copyright © 2018 Nadakuduti, Buell, Voytas, Starker and Douches. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Satya Swathi Nadakuduti, bmFkYWt1ZHVAbXN1LmVkdQ== David S. Douches, ZG91Y2hlc2RAbXN1LmVkdQ==

Satya Swathi Nadakuduti

Satya Swathi Nadakuduti C. Robin Buell

C. Robin Buell Daniel F. Voytas

Daniel F. Voytas Colby G. Starker5

Colby G. Starker5