94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Plant Sci., 02 October 2018

Sec. Plant Physiology

Volume 9 - 2018 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2018.01279

Seed germination is a complex process controlled by various mechanisms. To examine the potential contribution of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and gibberellin acid (GA) in regulating seed germination, diphenylene iodonium chloride (DPI) and uniconazole (Uni), as hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and GA synthesis inhibitor, respectively, were exogenously applied on tobacco seeds using the seed priming method. Seed priming with DPI or Uni decreased germination percentage as compared with priming with H2O, especially the DPI + Uni combination. H2O2 and GA completely reversed the inhibition caused by DPI or Uni. The germination percentages with H2O2 + Uni and GA + DPI combinations kept the same level as with H2O. Meanwhile, GA or H2O2 increased GA content and deceased ABA content through corresponding gene expressions involving homeostasis and signal transduction. In addition, the activation of storage reserve mobilization and the enhancement of soluble sugar content and isocitrate lyase (ICL) activity were also induced by GA or H2O2. These results strongly suggested that H2O2 and GA were essential for tobacco seed germination and by downregulating the ABA/GA ratio and inducing reserve composition mobilization mutually promoted seed germination. Meanwhile, ICL activity was jointly enhanced by a lower ABA/GA ratio and a higher ROS concentration.

Seeds are important genetic resources for sustainable agriculture and agricultural economy. Successful germination and seedling establishment are the foundation of agricultural production (Bentsink and Koornneef, 2008). It has been proposed that seed germination is mediated by gibberellin acid (GA) that promotes germination completion. Abscisic acid (ABA) has antagonistic effects on GA in inducing seed dormancy. The dynamic balance of ABA and GA, resulting from their synthesis, catabolism, and signaling pathway, is crucial for seed germination (Razem et al., 2006; Seo et al., 2006; Weiss and Ori, 2007; Topham et al., 2017). Up to now, the molecular mechanism of interaction between ABA and GA during germination remains largely elusive. It is well known that NCED (encoding 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase) is a key gene in ABA biosynthesis, and CYP707A (encoding ABA 8-hydroxylases) is the essential gene in ABA catabolism (Footitt et al., 2011). ABA insensitive 3 (ABI3) and ABA insensitive 5 (ABI5), the central ABA signaling components, serve as the final downstream repressors of seed germination in the ABA signaling pathway (Carles et al., 2002; Lim et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2013). GA20ox (encoding GA 20-oxidase) and GA3ox (encoding GA 3-oxidase) are critical genes during bioactive GA biosynthesis and GA2ox (encoding GA 2-oxidase) transfers active GAs to inactive GAs. RGL2 (repressor of GA-like protein), one of plant growth repressor DELLA proteins (DELLAs) (Zentella et al., 2007; Golldack et al., 2013), is considered the vital repressor of seed germination (Piskurewicz et al., 2008; Stamm et al., 2012). Gibberellin-insensitive dwarf protein (GID), a receptor of GA signaling, could interact with GA and eliminate the inhibition of seed germination by triggering the degradation of RGL2 (Cao et al., 2006; Griffiths et al., 2006).

Seed reserve composition mobilization is an important requirement for germination as well as subsequent plant growth and development (Bau et al., 1997; Kupidłowska et al., 2006). It should be noted that the lipid content of tobacco seed is up to 40% by weight (Giannelos et al., 2002). Isocitrate lyase (ICL, EC 4.1.3.1) is a key enzyme during the glyoxylate cycle that plays a major role in affecting net gluconeogenesis from lipid metabolism (Borek and Nuc, 2011). Generally, seed germination and seedling establishment are restrained by inhibiting ICL activity, as demonstrated in oilseeds such as sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.), coffee (Coffea arabica L.), and canola (Brassica napus L.) (Baleroni et al., 2000; Kupidłowska et al., 2006; Selmar et al., 2006). In addition, phytohormones ABA and GA are widely known to control the mobilization of lipids by inhibiting or inducing ICL activity and the responding gene expression in rice (Oryza sativa L.), wheat (Triticum aestivum L.), and barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) (Eastmond and Jones, 2005; Penfield et al., 2006).

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) act as regulators of growth and development, programmed cell death, hormone signaling, and responses to biotic and abiotic stresses (Breusegem et al., 2008). In seeds, ROS play a key role in various events, such as maturation, ripening, aging, and germination (Bailly et al., 2008; Müller et al., 2009; Barba-Espín et al., 2011). Plasma membrane nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase, the pivotal enzyme involved in ROS generation, regulates germination of barley seeds (Ishibashi et al., 2010). Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) is considered as the ROS messenger for long-distance transport in cells (Moller, 2001; Möller and Sweetlove, 2010), the stimulation of downstream transcription, and the activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) (Neill S. et al., 2002). Exogenous H2O2 stimulates seed germination of Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana L.), maize (Zea mays L.), and sunflower seeds by enhancing GA biosynthesis and ABA catabolism (Maarouf et al., 2015; Huang et al., 2017; Li et al., 2017). Nevertheless, H2O2 releases embryo dormancy in barley by activating GA signaling and synthesis rather than the repression of ABA signaling (Bahin et al., 2011). GA biosynthesizes in embryo during the germination and induces H2O2 production in wheat aleurone cells; H2O2 subsequently acts as a signal molecule to antagonize ABA signaling (Wu et al., 2014). Additional evidence has suggested that GA induces the germination of dormant caryopses by regulating the level of ABA and the ROS-antioxidant status (Cembrowska-Lech et al., 2015). Programmed cell death is induced by GA in aleurone layers also via the regulation of H2O2 production (Aoki et al., 2014). The application of H2O2-induced cell death was observed only under GA treatment but not ABA treatment (Bailly, 2013). Although several evidences indicate the crosstalk among ROS, GA and ABA affect seed germination, but the interaction between them remains elusive. Is there a relationship between GA and ROS that mutually induced or maintained homeostasis during seed germination? Similarly, it is unknown how ROS and GA synergistically control ABA levels during seed germination. Moreover, the relationship among ROS, GA, and ABA with ICL activity also has not been analyzed in tobacco seed germination.

Therefore, the purpose of the present study is to examine the interaction mechanism of H2O2, GA, ABA, and ICL in the process of germination. The effect of diphenylene iodonium chloride (DPI), a NADPH oxidases inhibitor (Morré, 2002), uniconazole (Uni), a GA synthesis inhibitor (Yang et al., 2012), DPI + GA and Uni + H2O2 on seed germination is investigated. In addition, ICL activity, ABA, GA, H2O2 contents, and the corresponding gene expressions involved in homeostasis and signal transduction are determined to gain insights on the crosstalk among ROS, ABA, and GA, and to acquire the regulation mechanism of ICL activity, by proposing a comprehensive model of tobacco seed germination.

Tobacco seeds, MS Yunyan 97, from Yunnan Tobacco Science Research Institute were used. GA, H2O2, DPI, and Uni were obtained from Aladdin Company, Hangzhou, China.

Seeds were surface-sterilized with 0.5% NaClO solution for 15 min and then washed three times with sterilized distilled water to remove the residue of the disinfectant. The sterilized seeds were poured into a sealed beaker with priming solutions (1:5, w/v) at 20°C in darkness for 24 h, without changing the solutions during the priming process. All primed seeds were air-dried at 25°C for 48 h to the original moisture content. In this study, ten priming solutions including distilled water (H2O), 10 mM GA, 50 mM H2O2, 30 μM Uni, 100 μM DPI, and the corresponding combination priming GA + DPI, H2O2 + Uni, GA + Uni, H2O2 + DPI, and Uni + DPI were all carried out.

All primed tobacco seeds were germinated on three-layer water-saturated filter papers in germination dishes of 10 cm diameter at 25°C, with a photosynthetic active photon flux density of 250 mmol m-2 s-1 and a photoperiod of 8 h light (L): 16 h dark (D). In addition, four replications of 100 seeds for each treatment were used. Germinated seeds (radicle emergence) were recorded daily (International Seed Testing Association [ISTA], 2010). Germination percentage (GP) was calculated from the 1st to the 16th day (GP = 100% × Gt/100, where Gt is the total germinated seeds on the tth day. Germination energy (GE) was the GP on the 7th day. Germination index (GI) and mean germination time (MGT) were also calculated on the 2nd, 5th, and 7th days [GI = Σ(Gt/Tt); MGT = Σ(Gt × Tt)/ΣGt, where Gt is the number of new germinated seeds in time Tt].

The ICL activity assay was performed as described by Yanik and Donaldson (2005). The mixture containing 72.5 mM phosphate buffer (pH 6.9), 10.8 mM MgCl2, and 10 mM phenylhydrazine in a volume of 1 ml was used. Freshly prepared 1.74 mM isocitrate and protein extracts were then added at 25°C. Phenylhydrazine forms a yellow phenylhydrazone in the presence of glyoxylic acid. The activity was detected by the increase in absorbance at 324 nm using the molar extinction coefficient 𝜀 = 1.7 × 104.

Seeds were collected at 0, 24, and 48 h during imbibition. For each treatment, 0.4 g seeds with four biological replications were collected for physiological parameter determination. H2O2 content was determined according to the method of Doulis et al. (1997), and calculated as μmol H2O2 decomposition min-1⋅g-1⋅FW. Soluble sugar content in seeds was measured by using the anthrone colorimetric method (Li and Li, 2013) with a slight modification.

Seeds were collected at 0, 24, and 48 h during imbibition. Approximately 0.4 g seed powder for each treatment with three biological replications were homogenized with 2 mL of cold acetonitrile, kept at 4°C for 12 h and then centrifuged at 23,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant was transferred to a new centrifugal tube and mixed with 1.5 mL of phosphate buffer solution (0.1 M), kept at -80°C for 30 min and thawed adequately at 4°C. The mixture was extracted by 2.5 mL of ethyl acetate three times after the addition of 1 mL hydrochloric acid (0.5 mM). Five milliliters of the ethyl acetate phase was collected after centrifuging at 1500 × g for 5 min at 4°C, dried with a nitrogen evaporator, and redissolved in 1 mL mobile phase consisting of methanol and water (1:1, v/v). The collected extract was filtered through a 0.22 mm membrane filter for high-performance liquid chromatography equipped with a 6.0 mm × 150 mm, a 5 mm particle size reverse-phase (C18) column, and an ultraviolet detector (Waters 2487), as previously described (Huang et al., 2017). GA3 and ABA peaks were detected by using a SPD-20A (Shimadzu) absorbance detector at 254 nm. The mobile phase consisted of methanol and 0.2% phosphoric acid solution (1:1, v/v) at a flow rate of 0.8 mL min-1. Standard GA3 and ABA (Sigma Chemical Company) were used for the development of standard curves.

Total RNA was isolated from seeds using TRIzol reagent (Huayueyang, Beijing, China) and reverse-transcribed using a ReverTra Ace qPCR RT Kit (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Eight genes were involved in the tobacco GA signal: NtGA20ox1, NtGA20OX2, NtGA3OX2, NtGA2OX1, NtGA2OX2, NtGID1, NtGID2, and NtRGL2. Four genes were involved in the ABA signal: NtNCED1, NtNCED3, NtCYP707A1, and NtCYP707A2. NtRBOH (Nicotiana tabacum respiratory burst oxidase homolog) and NtICL were involved in NADPH oxidase and ICL biosynthesis (Supplementary Table S1). RT-qPCR was performed using the Roche real-time PCR detection system (Roche Life Science, United States). Each reaction (20 μL) consisted of 10 μL SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Takara, Chiga, Japan), 1 μL diluted cDNA, and 0.1 μM forward and reserve primers. The PCR cycling conditions were as follows: 95°C for 3 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 10 s and 58°C for 45 s. The tobacco Actin gene was used as an internal control. Relative gene expression was calculated according to Livak and Schmittgen (2001).

Data were analyzed by analysis of variance (ANOVA) using the Statistical Analysis System (SAS) (version 9.2) followed by the calculation of the least significant difference (LSD, α = 0.05). Percentage data were arc-sin-transformed prior to analysis.

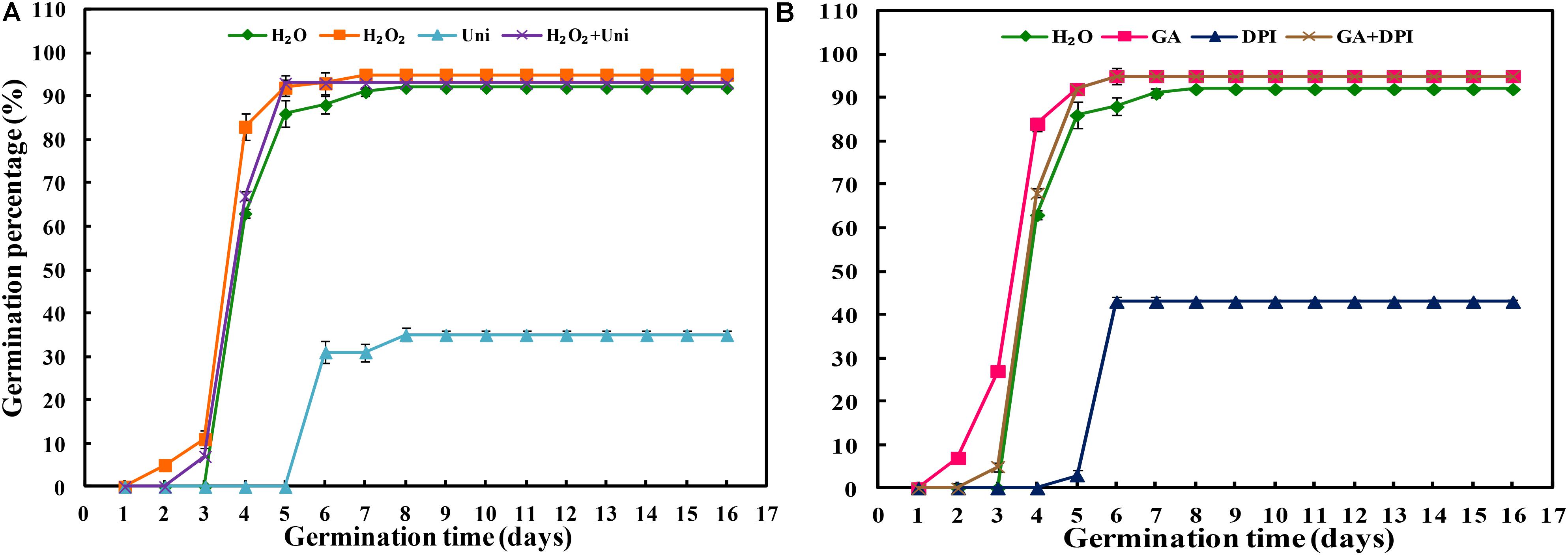

Uni or DPI significantly inhibited seed germination compared with other treatments (Figure 1 and Supplementary Figure S2). The GP of Uni was 35% ultimately, and that of DPI was 43%. Seeds treated by Uni + DPI barely germinated, and GP was only 5% until the end of germination (Supplementary Figure S1). The seed germination inhibition of Uni or DPI could be reversed by adding GA or H2O2. Eventually, the GP of H2O2 + DPI and GA + Uni reached 92%, respectively (Supplementary Figure S1). Interestingly, the combination of H2O2 + Uni or GA + DPI reversed the inhibition effect of Uni or DPI on germination, and the GPs of both were greater than 90%. Seeds treated with H2O2 or GA started germinating on the second day, and those treated with H2O2 + Uni or GA + DPI began to germinate on the third day, followed by H2O on the fourth day, while seeds treated with Uni or DPI delayed germination until the sixth day of germination when the GP of GA or H2O2 had already reached 92% (Figure 1 and Supplementary Table S2).

FIGURE 1. Inhibitor of H2O2 (A) or GA (B) decreased seed germination. H2O, hydropriming (water priming); H2O2, 50 mM hydrogen peroxide priming; Uni, priming with 30 μM uniconazole, as GA synthesis inhibitor; H2O2 + Uni, 50 mM hydrogen peroxide and 30 μM uniconazole combination priming; GA, 10 mM gibberellin acid priming; DPI, priming with 100 μM diphenyliodonium, as H2O2 scavenger; GA+ DPI, 10 mM gibberellin acid and 100 μM diphenyliodonium combination priming. Vertical bars above mean indicate standard error of four replicates of 100 seeds each for each treatment. Values are mean ± SE (n = 4).

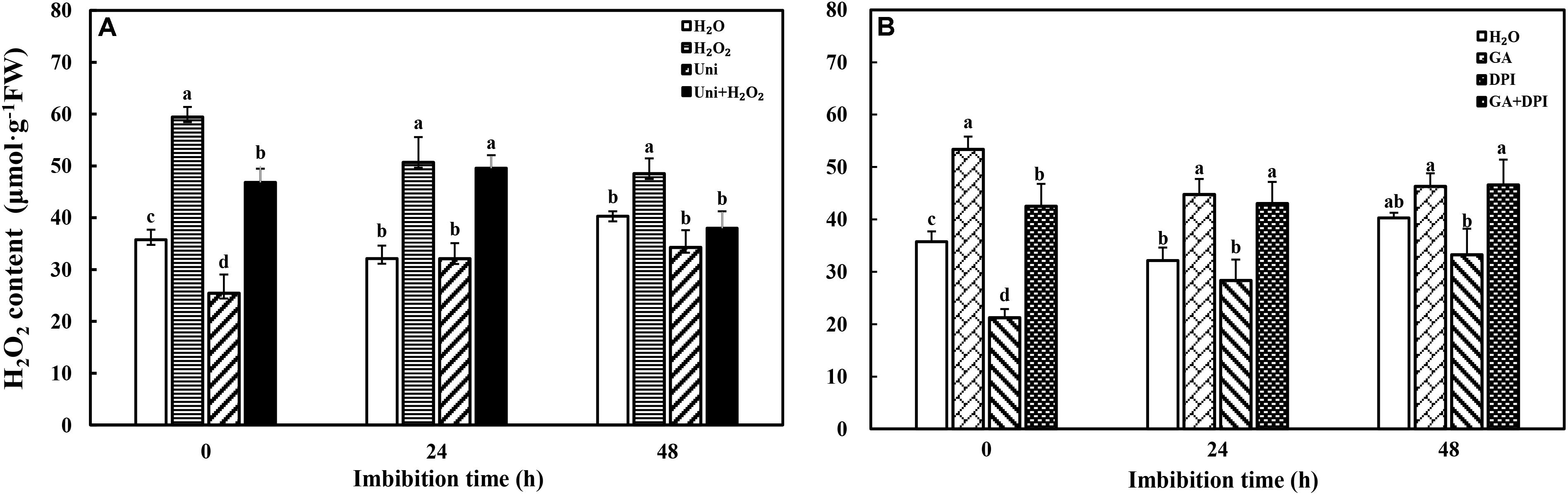

Exogenous H2O2 and GA obviously increased endogenous H2O2 content, while DPI and Uni significantly reduced the content at 0 h of imbibition (also the end time of priming) compared with H2O (Figure 2). GA + DPI reversed the reduction of endogenous H2O2 caused by DPI, and H2O2 + Uni also reversed the reduction caused by Uni, especially from 0 to 24 h.

FIGURE 2. Accumulation of H2O2 during seed imbibition in response to different treatments. (A,B) H2O2, hydrogen peroxide. Seeds were collected, respectively, at 0, 24, and 48 h during imbibition, and four replications for each treatment at each sampling time were used. Different small letters on top of the bars indicate significant differences (LSD, α = 0.05) among treatments at the same imbibition time. Error bars indicate ± SE of mean (n = 4). For additional explanations, please see Figure 1.

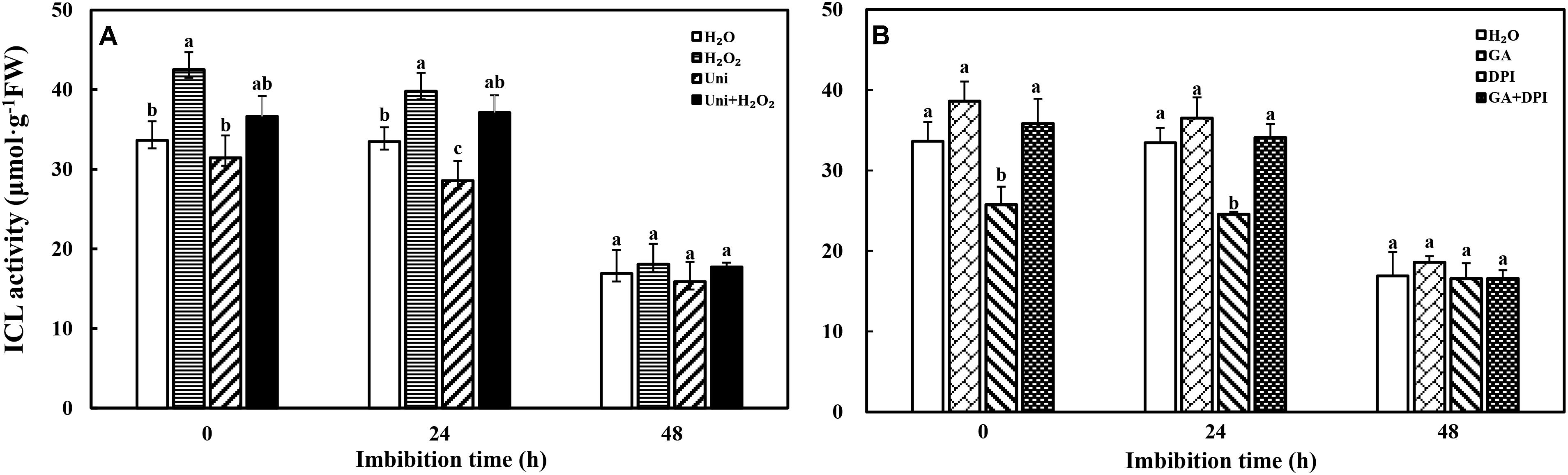

ICL activity had an observable decrease at 48 h that was about half the ICL activity at 0 h (Figure 3). The ICL activity of DPI and Uni was notably lower than that of H2O at 0 and 24 h, and at 24 h, respectively. The maximal ICL activity was recorded in H2O2 or GA, followed by H2O2 + Uni or GA + DPI from 0 to 24 h. Ultimately, all treatments kept the same level at 48 h.

FIGURE 3. ICL activity decreased accompanied by seed imbibition. (A,B) ICL, isocitrate lyase. Seeds were collected, respectively, at 0, 24, and 48 h during imbibition, and four replications for each treatment at each sampling time were used. Different small letters on top of the bars indicate significant differences (LSD, α = 0.05) among treatments at the same imbibition time. Error bars indicate ± SE of mean (n = 4). For additional explanations, please see Figure 1.

The change trend of soluble sugar was consistent with ICL activity. The main difference was that soluble sugar content dropped significantly at 24 h, which was earlier than 48 h when the changes in ICL activity occurred (Supplementary Figure S4). H2O2 or GA increased the content of soluble sugar at 0 and 24 h, significantly at 24 h, while Uni or DPI decreased the content at 0 and 48 h, significantly at 48 h. H2O2 + Uni or GA + DPI slightly reversed the effects induced by Uni or DPI at 0 and 48 h.

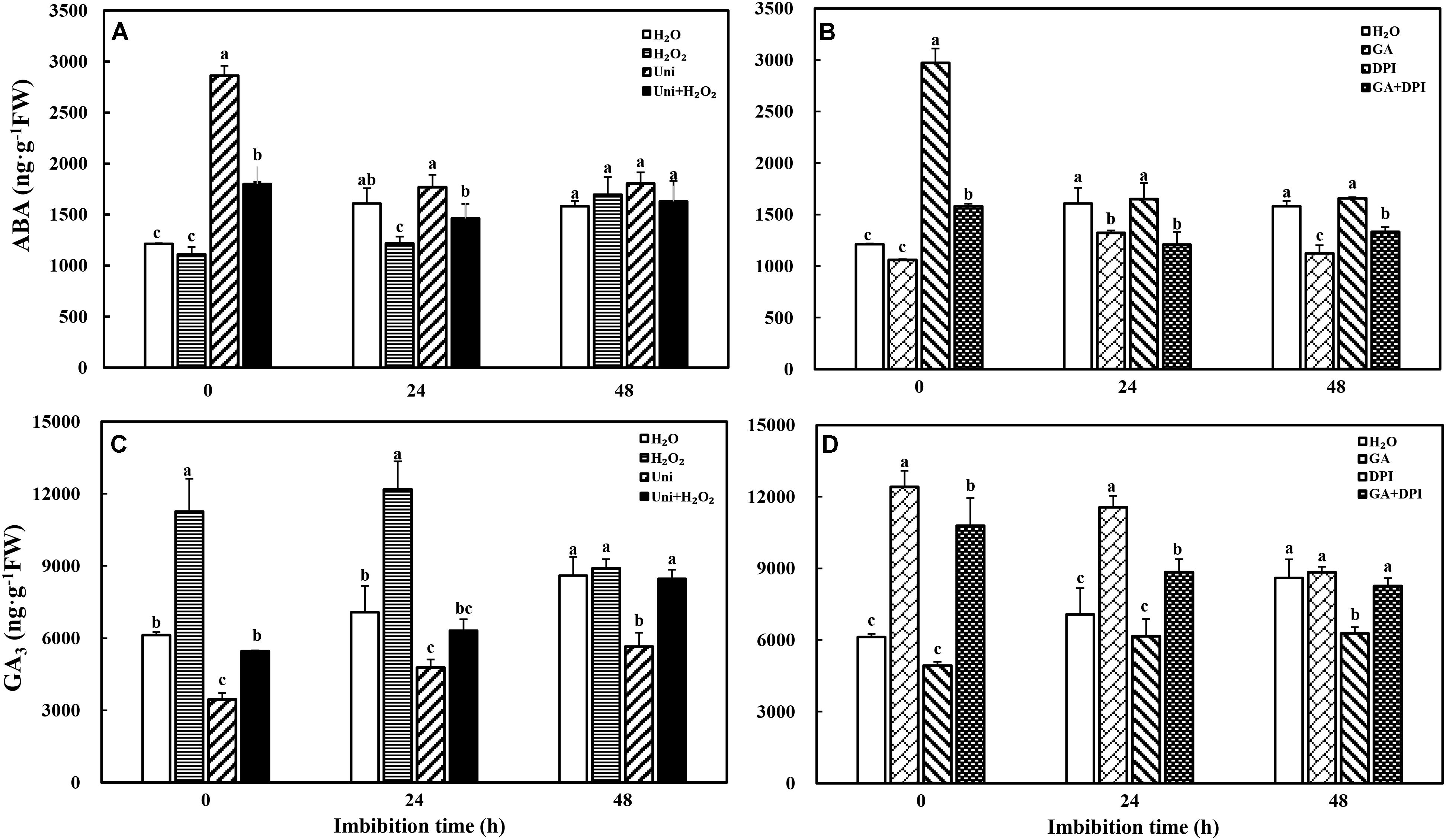

It was rather obvious that both Uni and DPI dramatically induced endogenous ABA accumulation at the beginning of imbibition (Figures 4A,B, 0 h). GA decreased ABA content throughout the whole imbibition period, while H2O2 decreased ABA content at 0 and 24 h. In general, H2O2 + Uni or GA + DPI counteracted the accumulation of ABA induced by Uni or DPI, of which ABA content was still higher than that in GA or H2O2, especially at 0 h.

FIGURE 4. Inhibitor of GA or H2O2 increased ABA (A,B) and GA3 (C,D) content during seed imbibition in response to different treatments. Seeds were collected, respectively, at 0, 24, and 48 h during imbibition, and four replications for each treatment at each sampling time were used. Different small letters on top of the bars indicate significant differences (LSD, α = 0.05) among treatments at the same imbibition time. Error bars indicate ± SE of mean (n = 4). For additional explanations, please see Figure 1.

In addition, the rapid and extensive generation of endogenous GA3 with H2O2 or GA treatment was also significantly higher than that with H2O treatment at 0 and 24 h. Uni markedly decreased GA3 content, which was distinctly lower than H2O from 0 to 48 h (Figure 4C). H2O2 + Uni obviously alleviated the decrease in GA3 content caused by Uni at 0 and 24 h and stablized at the same GA3 level as H2O at 48 h. GA3 significantly declined at 48 h with DPI treatment (Figure 4D). Exogenous GA obviously increased GA3 content at 0 and 24 h. GA + DPI slightly decreased GA3 content comparing with exogenous GA, which was still significantly higher than H2O from 0 to 24 h.

The ABA/GA ratio of Uni and DPI was obviously higher than other treatments at 0 h, which was 2–3 fold as much as H2O (Supplementary Figure S3), and then decreased sharply at 24 h, when Uni was still significantly higher than H2O. The ABA/GA ratio and H2O2 remained at lower levels during the whole imbibition process.

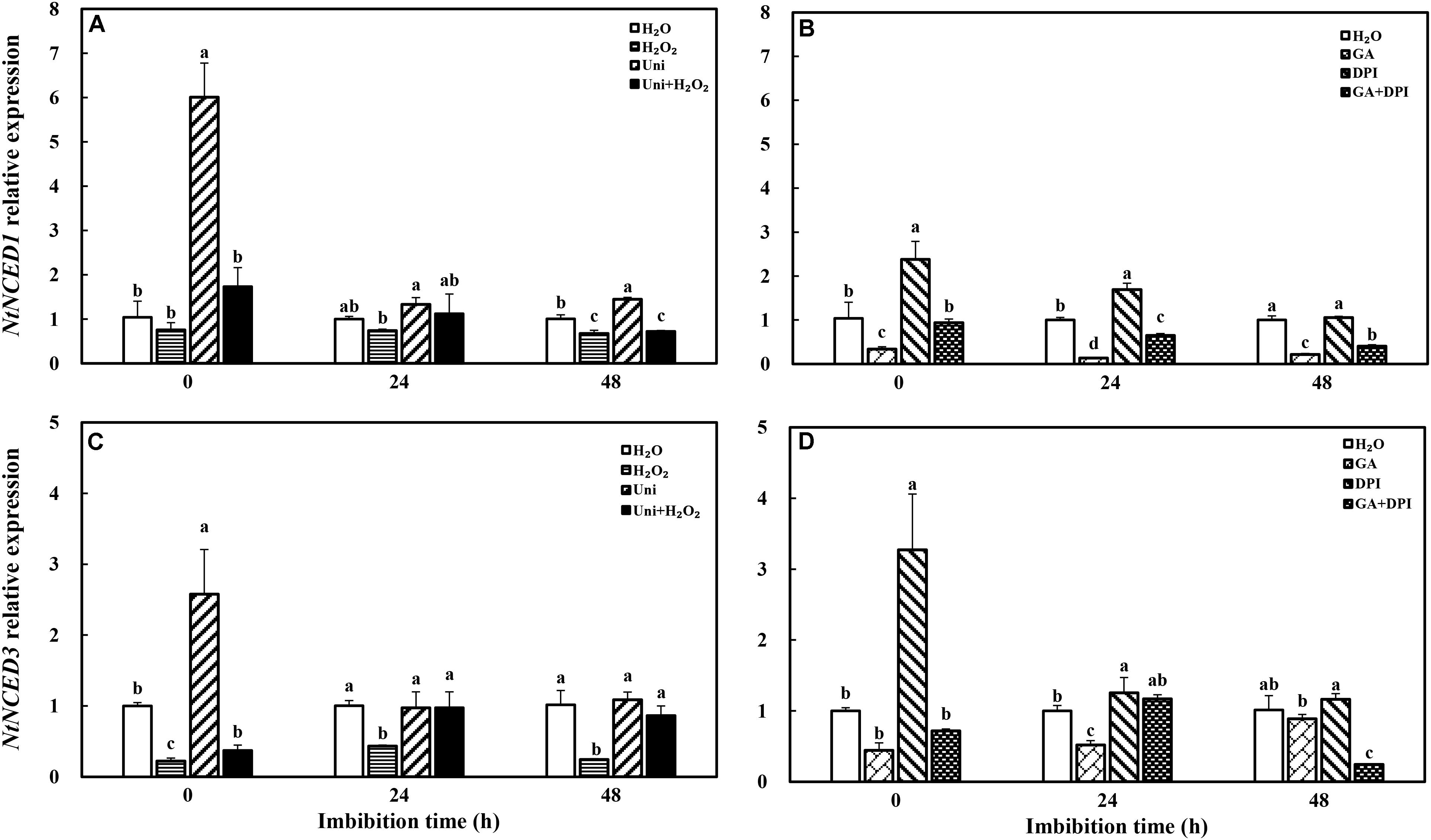

Both Uni and DPI induced the expression of NtNCED1 and NtNCED3, ABA synthesis genes, at the end of priming (Figure 5, 0 h). The NtNCED1 expression of Uni was 6-fold of H2O, and that of DPI was 2.5-fold. Meanwhile, the NtNCED3 transcription level of DPI was 3.2-fold of H2O, and that of Uni was 2.5-fold. H2O2 significantly decreased NtNCED3 expression and slightly decreased NtNCED1 expression, while GA significantly decreased NtNCED1 expression. At 48 h, H2O2 + Uni significantly decreased the expression of NtNCED3, while GA + DPI decreased the expression of both NtNCED1 and NtNCED3.

FIGURE 5. GA or H2O2 decreased the transcript level of ABA biosynthesis genes NtNCED1 (A,B) and NtNCED3 (C,D) during seed imbibition. Seeds were collected, respectively, at 0, 24, and 48 h during imbibition, and four replications for each treatment at each sampling time were used. Different small letters on top of the bars indicate significant differences (LSD, α = 0.05) among treatments at the same imbibition time. Error bars indicate ± SE of mean (n = 4). For additional explanations, please see Figure 1.

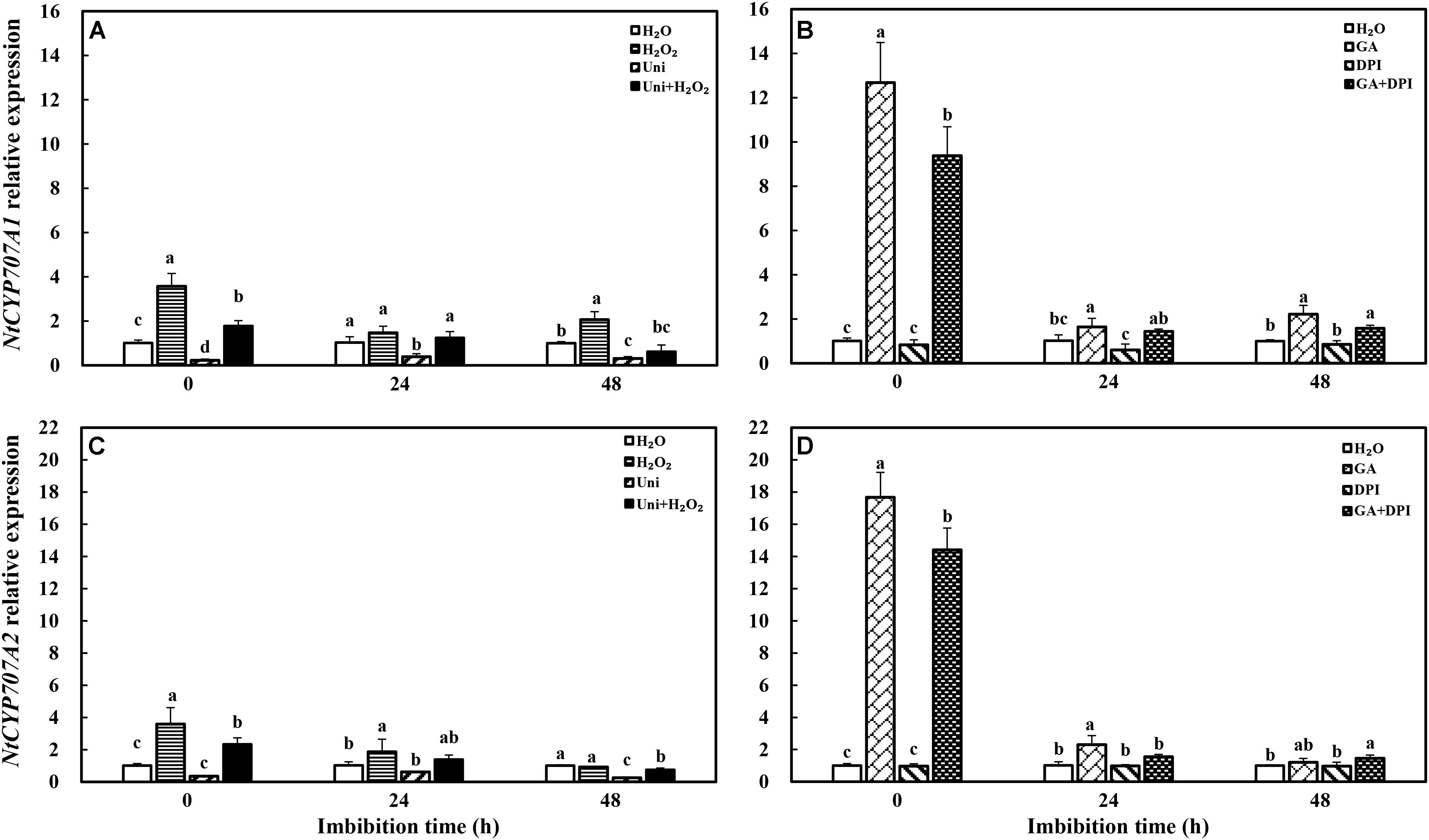

Gibberellin acid dramatically promoted the transcription level of NtCYP707A1 and NtCYP707A2, ABA catabolism genes, which was, respectively, 12-fold and 17-fold of H2O, followed by GA + DPI with 9- and 14-fold of H2O, while the effect of H2O2 was weaker than GA, approximately 3.6- and 4-fold of H2O (Figure 6). Uni significantly decreased the expression of NtCYP707A1 and NtCYP707A2 from 0 to 48 h and at 48 h, respectively, and both remained at a low level during imbibition. DPI had no obvious function on the expression of NtCYP707A1 and NtCYP707A2.

FIGURE 6. GA or H2O2 enhanced the transcript level of ABA catabolism genes NtCYP707A1 (A,B) and NtCYP707A2 (C,D) during seed imbibition. Seeds were collected, respectively, at 0, 24, and 48 h during imbibition, and four replications for each treatment at each sampling time were used. Different small letters on top of the bars indicate significant differences (LSD, α = 0.05) among treatments at the same imbibition time. Error bars indicate ± SE of mean (n = 4). For additional explanations, please see Figure 1.

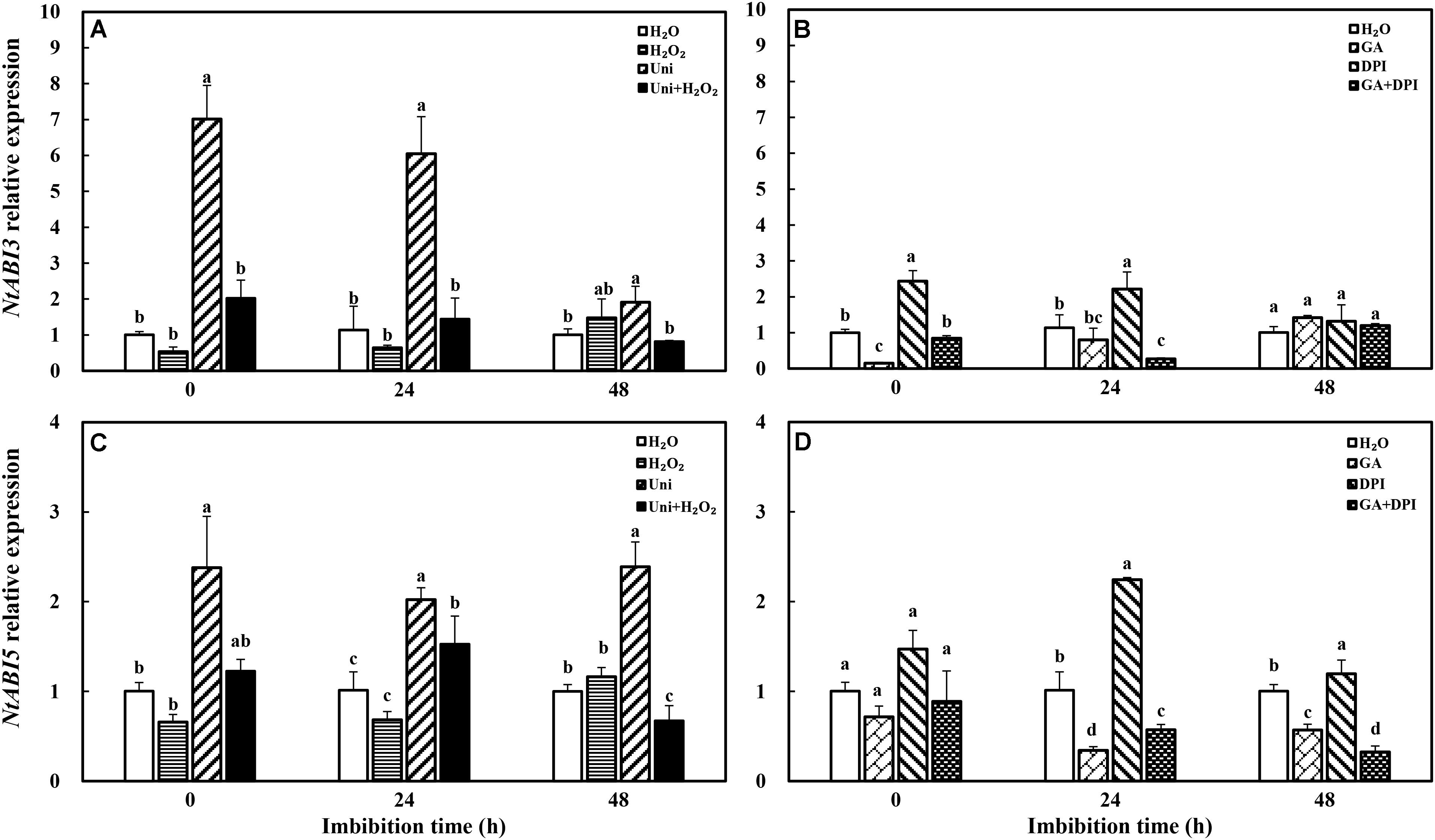

In addition, Uni significantly enhanced NtABI3 and NtABI5 expression compared with H2O during the whole progress of imbibition (Figure 7), and DPI upregulated the expression of NtABI3 from 0 to 24 h and NtABI5 from 24 to 48 h. The downregulation induced by H2O2 was not obvious in NtABI3 and NtABI5 similarly to H2O2 + Uni. GA downregulated the expression of NtABI3 from 0 to 24 h as well as the expression of NtABI5 from 24 to 48 h, consistent with GA + DPI.

FIGURE 7. GA or H2O2 downregulated the transcript level of ABA signaling genes NtABI3 (A,B) and NtABI5 (C,D) during seed imbibition. Seeds were collected, respectively, at 0, 24, and 48 h during imbibition, and four replications for each treatment at each sampling time were used. Different small letters on top of the bars indicate significant differences (LSD, α = 0.05) among treatments at the same imbibition time. Error bars indicate ± SE of mean (n = 4). For additional explanations, please see Figure 1.

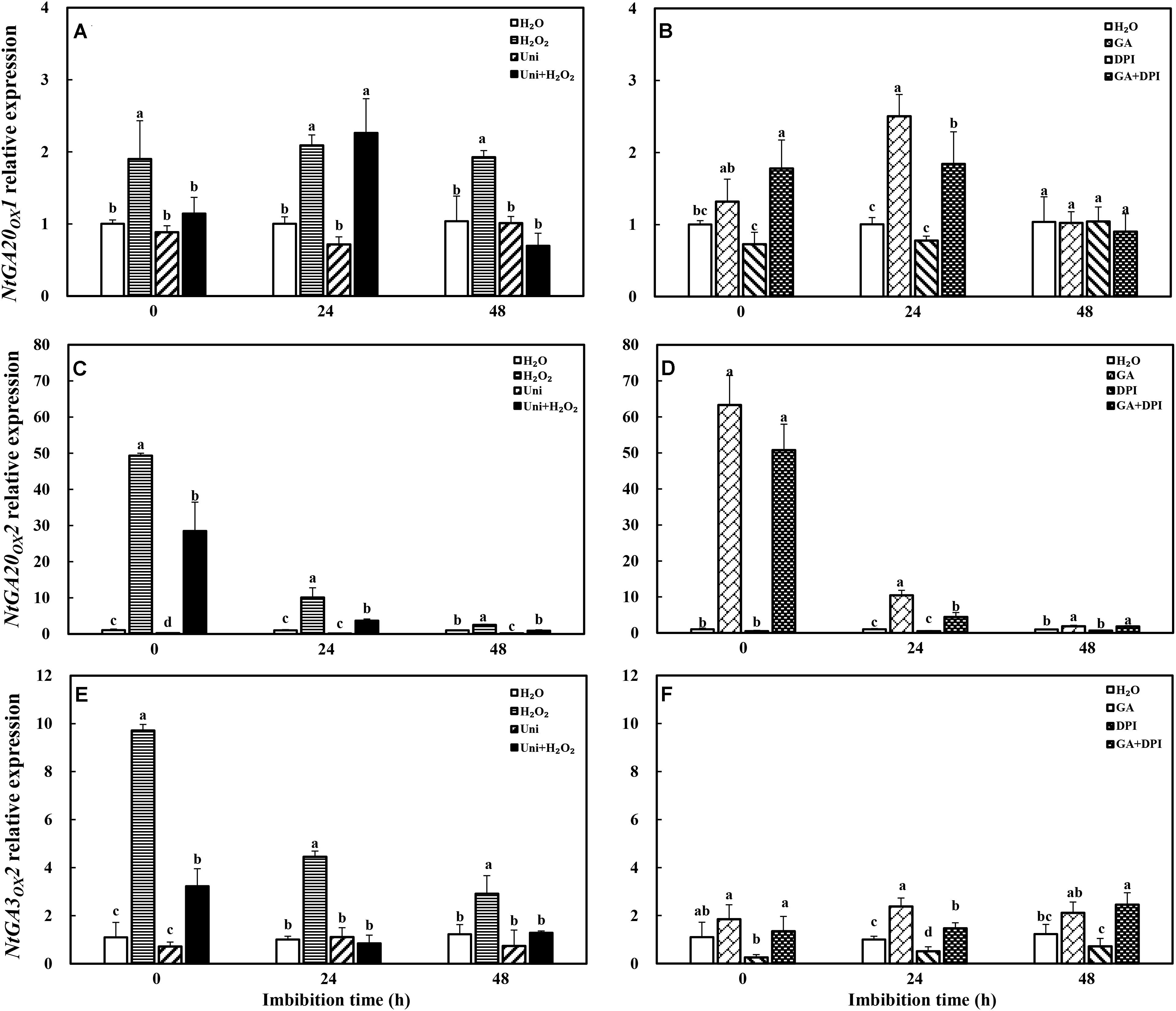

H2O2 dramatically enhanced the transcription level of GA synthesis genes (NtGA20OX1, NtGA20OX2, and NtGA3OX2). GA only obviously increased the expression of NtGA20OX2 (Figure 8). Uni largely inhibited NtGA20OX2 expression at 0 and 48 h, while H2O2 + Uni significantly upregulated the expression of NtGA20OX2 from 0 to 24 h, NtGA20OX1 at 24 h, and NtGA3OX2 at 0 h, respectively. In addition, DPI mainly inhibited the expression of NtGA3OX2 and was ineffective in NtGA20OX1 and NtGA20OX2. GA + DPI obviously upregulated the expression of NtGA20OX2, followed by NtGA20OX1 and NtGA3OX2.

FIGURE 8. GA or H2O2 upregulated the transcript level of GA biosynthesis genes NtGA20OX2 (A,B), NtGA20OX1 (C,D), and NtGA3OX2 (E,F) during seed imbibition. Seeds were collected, respectively, at 0, 24, and 48 h during imbibition, and four replications for each treatment at each sampling time were used. Different small letters on top of the bars indicate significant differences (LSD, α = 0.05) among treatments at the same imbibition time. Error bars indicate ± SE of mean (n = 4). For additional explanations, please see Figure 1.

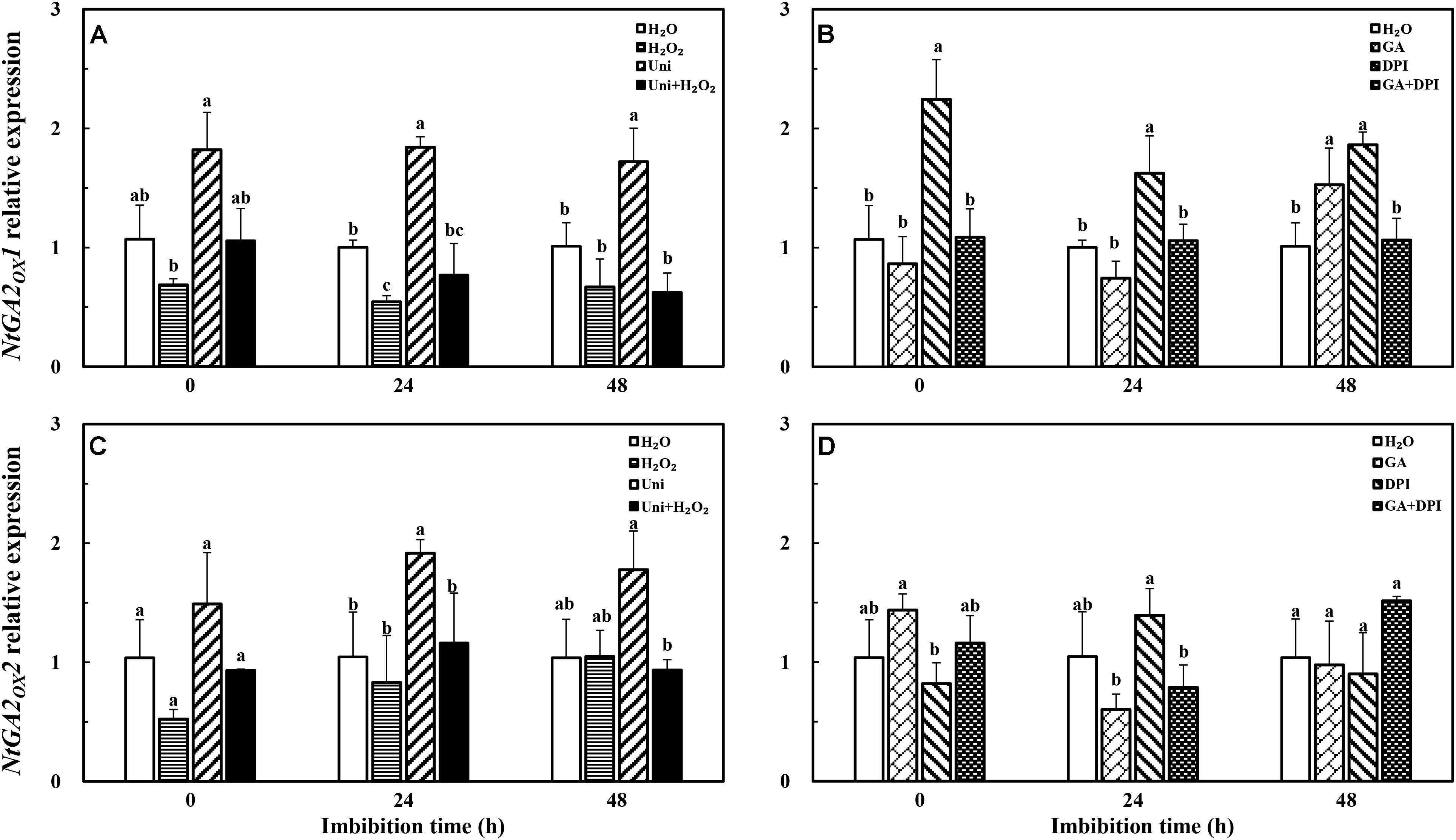

The transcription level of the GA catabolism gene NtGA2OX1 was significantly decreased by H2O2 at 24 h, but not found in exogenous GA treatment (Figure 9). There was no significant difference among GA, H2O2, and H2O treatments with regard to NtGA2OX2. The expression of the two NtGA2OX genes was increased rapidly under the Uni condition, and was notably reversed by the addition of H2O2, meanwhile, NtGA2OX1 expression was upregulated by DPI during the entire imbibition period but inhibited by GA + DPI.

FIGURE 9. GA or H2O2 mediated the transcript level of GA catabolism genes NtGA2OX1 (A,B) and NtGA2OX2 (C,D) during seed imbibition. Seeds were collected, respectively, at 0, 24, and 48 h during imbibition, and four replications for each treatment at each sampling time were used. Different small letters on top of the bars indicate significant differences (LSD, α = 0.05) among treatments at the same imbibition time. Error bars indicate ± SE of mean (n = 4). For additional explanations, please see Figure 1.

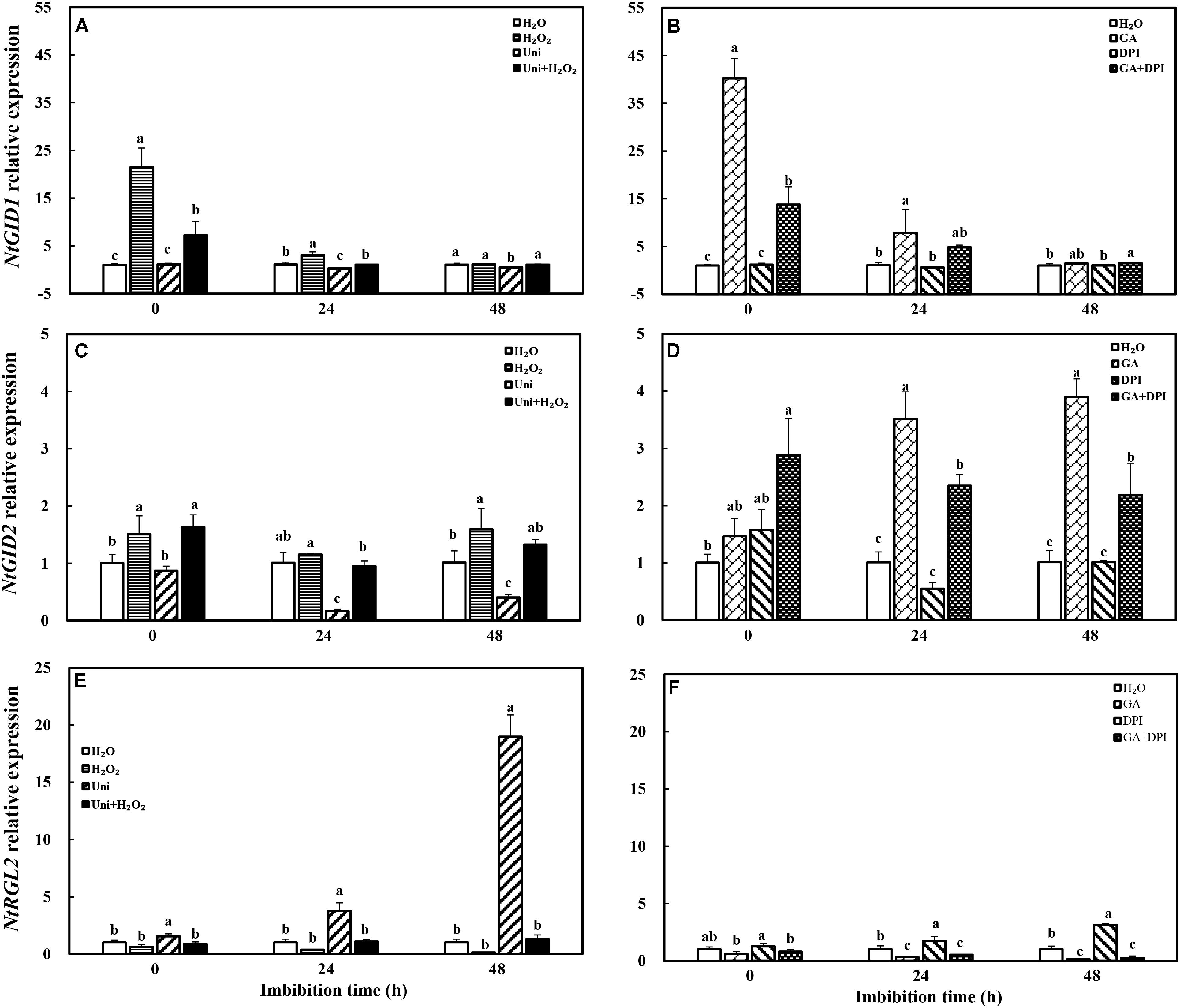

Uni significantly upregulated the transcription level of NtRGL2 and downregulated the NtGID2 gene expression, while DPI only influenced the upregulation of NtRGL2 (Figure 10). H2O2 enhanced the expression of NtGID1 and NtGID2 as did H2O2 + Uni, significantly at 0 h. GA also downregulated the NtRGL2 expression and upregulated NtGID1 and NtGID2; especially, the NtGID1 expression was 40-fold of H2O at 0 h. GA + DPI obviously enhanced the expression of NtGID1 and NtGID2 during the whole imbibition process.

FIGURE 10. GA or H2O2 mediated the transcript level of GA signaling genes NtGID1 (A,B), NtGID2 (C,D), and NtRGL2 (E,F) during seed imbibition. Seeds were collected, respectively, at 0, 24, and 48 h during imbibition, and four replications for each treatment at each sampling time were used. Different small letters on top of the bars indicate significant differences (LSD, α = 0.05) among treatments at the same imbibition time. Error bars indicate ± SE of mean (n = 4). For additional explanations, please see Figure 1.

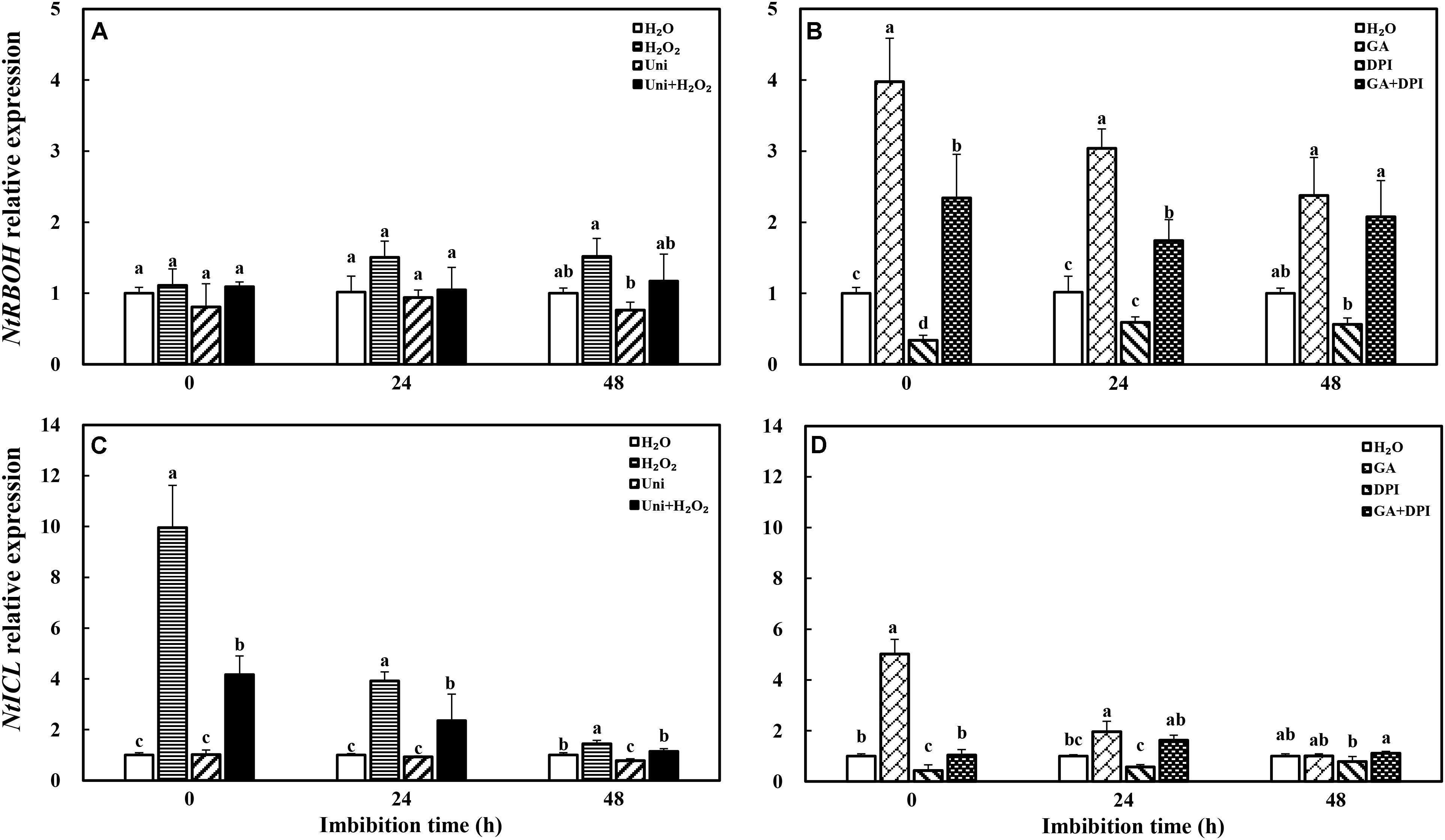

The transcription of NADPH oxidase gene (NtRBOH), involved in H2O2 production, was markedly upregulated by priming with GA (Figure 11), and was reversed by the addition of DPI in GA + DPI. Conversely, there was only weak enhancement or decrease with H2O2 or Uni compared with H2O, as well as H2O2 + Uni. NtICL was obviously upregulated by exogenous H2O2 or GA, especially H2O2 treatment, the NtICL expression was 10-fold of H2O at 0 h. Meanwhile, Uni kept the same level as H2O but DPI was significantly lower than H2O at the end of priming (Figure 11D, 0 h). The expression of NtICL in H2O2 + Uni was significantly higher than in H2O at 0 h and 24 h, and it was not found in GA + DPI.

FIGURE 11. GA or H2O2 upregulated the transcript level of NtRBOH (A,B) and NtICL (C,D) during seed imbibition. NtRBOH and NtICL were involved in NADPH oxidase and ICL biosynthesis. Seeds were collected, respectively, at 0, 24, and 48 h during imbibition, and four replications for each treatment at each sampling time were used. Different small letters on top of the bars indicate significant differences (LSD, α = 0.05) among treatments at the same imbibition time. Error bars indicate ± SE of mean (n = 4). For additional explanations, please see Figure 1.

Gibberellin acid was crucial for seed germination, and the seed germination ability was also related to the accumulation of H2O2 to a critical level (Weiss and Ori, 2007; Huang et al., 2017). In the present study, H2O2 and GA accelerated seeds to germinate 2 days in advance. While DPI and Uni, which are considered as generation inhibitors of H2O2 and GA, respectively, significantly delayed the germination by 2 and 1 days, respectively (Figure 1 and Supplementary Figure S2). Meanwhile, the GP of DPI and Uni was obviously decreased, whereas the GP of DPI (43%) was slightly higher than that of Uni (35%). These results suggest that both GA and H2O2 are essential for seed germination and to guarantee germination speed and percentage. Similar results were found in flixweed (Descurainia sophia L.) and rice seeds; 10 μM uniconazole completely inhibited flixweed seed germination, and rice seed germination was inhibited by 10 μM DPI (Li et al., 2005; Ye and Zhang, 2012). Further evidence was presented in DPI + Uni treatment in which seeds barely germinated during the whole germination progress (Supplementary Figure S1). In addition, with H2O2 + Uni or GA + DPI treatment, seeds germinated 1 day in advance and the GP reached the same high level as with H2O2 + DPI or GA + Uni (Supplementary Figure S1). Furthermore, exogenous GA significantly increased the endogenous H2O2 content but Uni inhibited H2O2 synthesis (Figure 2). Likewise, exogenous H2O2 induced endogenous GA synthesis but DPI decreased the GA content (Figures 4C,D). These results all led to the preliminary conclusion that GA and H2O2 may mutually induce and have a synergistic effect on seed germination.

It is well known that ABA and GA are essential regulation factors in seed dormancy and germination (Toh et al., 2008; Stamm et al., 2012; Maarouf et al., 2015), and the antagonistic crosstalk between GA and ABA plays a pivotal role in the modulation of seed germination (Piskurewicz et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2016). Studies on numerous species have demonstrated that H2O2 promotes seed germination by triggering GA biosynthesis and ABA catabolism (Liu et al., 2010). DPI or Uni priming obviously increased the ABA content and the ABA/GA ratio (Figures 4A,B and Supplementary Figure S3), and decreased endogenous H2O2 content at the end of priming (Figure 2). These may be the reasons for intense reduction in the germination speed and the GP resulting from DPI or Uni. Arabidopsis seeds have evolved a mechanism to regulate the abundance of the antagonistically acting hormones ABA and GA before germination. GA increased synthesis arising from diminished ABA by downregulating AtNCED9 and upregulating AtCYP707A1 and AtCYP707A2 (Topham et al., 2017). The mechanism also appeared in this study, and H2O2 and GA significantly reduced the ABA content at 24 h of imbibition and obviously increased the endogenous GA content at 0 and 24 h, and kept a lower level of the ABA/GA ratio during imbibition (Supplementary Figure S3). Exogenous GA reduced the expression of the ABA biosynthesis genes: NtNCED1 from 0 to 48 h of imbibition, and NtNCED3 (Figure 5) and NtABI5 at 24 h (Figure 7). H2O2 mainly downregulated the transcription level of NtNCED3 (Figure 5). Concomitantly, at 0 h of imbibition, ABA metabolic genes were highly upregulated by exogenous GA (12∼17-fold of H2O treatment), followed by H2O2 (9∼14-fold of H2O treatment) (Figure 6). However, DPI did not affect the expression of NtCYP707A1 and NtCYP707A2. This result may hint that H2O2 affected NtCPY707A through GA rather than directly affecting them. Plenty of studies have shown that H2O2 affects GA content by upregulating synthetic gene and downregulating catabolism gene during seed germination (Liu et al., 2010; Gomes and Garcia, 2013). Further evidence has shown that H2O2 markedly upregulated NtGA20OX2 (50-fold of H2O at 0 h) and NtGA3OX2 (10-fold of H2O at 0 h) (Figure 8) from 0 to 48 h during imbibition, and downregulated NtGA2OX1 (Figure 9). Notably, exogenous GA enhanced the production of endogenous GA by upregulating NtGA20OX2 (Figure 8). This seems to be a self-induced feedback regulation. On the whole, these results suggest that there is a crosstalk between GA and H2O2 in mediating the homeostasis of ABA and GA.

On the other hand, the expression of GA signaling transduction genes NtGID1 and NtGID2 increased and the level of the seed germination inhibitor gene NtRGL2 decreased after seed priming by GA or H2O2 (Figure 10), as different as possible from Uni or DPI. Cellular GA binds to the receptor GID, and the GID–GA complex interacts with DELLA to trigger the ubiquitination and destruction of RGL2, and induce seed germination (Ariizumi and Steber, 2007; Golldack et al., 2013). GA or H2O2 downregulated the expression of NtABI3 and NtABI5, while Uni or DPI upregulated their expression. ABI3 and ABI5 were considered as the final downstream repressor of seed germination in the counterbalance of ABA and GA signals (Carles et al., 2002; Piskurewicz et al., 2008), and this was consistent with the RGL2-ABI5 model module that integrated the GA and ABA signaling pathways during seed germination (Liu et al., 2016). Another study has shown that H2O2 affects the ABA signal by inactivating ABI1 and ABI2 (Neill S. et al., 2002). These results suggest that there is a crosstalk between GA and H2O2 in mediating the signal transduction of ABA and GA.

Seed germination is a complex process controlled by many mechanisms, including the roles of GA and ABA (Toh et al., 2008), as well as radicle emergence (Guo et al., 2013), endosperm weakening (Zhang et al., 2014), and mobilization of storage reserves (Kelly et al., 2011; Han et al., 2013). During seed germination, lipolysis was followed by the gluconeogenesis pathway mainly conducting glucose production and sucrose used for seedling growth (Eckardt, 2005; Yan et al., 2014). For oilseeds, effective degradation of storage lipids is crucial for supporting respiratory substrates and energy generation, leading to successful seed germination and seedling establishment (Graham, 2008). Tobacco seeds contained higher lipid (30%) and lower sugar (10%) contents compared to the contents before priming (data are not shown), but the highest contents of soluble sugar in tobacco seeds was recorded at the end of priming (Supplementary Figure S3, 0 h). In addition, the change pattern of the ICL activity, which was involved in gluconeogenesis from lipid metabolism, was correlated with soluble sugar content during imbibition (Figure 3). Previous research conducted on oilseed species Arabidopsis (Meyer et al., 2012), sunflower (Raineri et al., 2016), and Brassica rapa (Gu et al., 2016) had also indicated that the levels of triacylglycerols, as components of lipids, decreased gradually during germination, suggesting that oilseed germination depends on oil breakdown and gluconeogenesis (Pritchard et al., 2002; Kelly et al., 2011).

Moreover, ABA and GAs have opposite roles in storage oil breakdown in the embryo (Penfield et al., 2006). Uni and DPI obviously increased the ABA content at 0 h of imbibition, and decreased the ICL activity at 0 and 24 h, significantly in DPI. ABA content increase accompanied with the reduction of ICL activity in Uni and DPI, this result was in agreement with the studies showed that exogenous ABA inhibited the activity of ICL in castor bean endosperm and Brassica rapa (Marriott and Northcote, 1977; Finkelstein and Lynch, 2000), and GA was able to reverse the inhibitory effect of ABA. However, it was also interesting to note that GA significantly decreased the endogenous ABA content at 24 and 48 h (Figure 4) but was ultimately ineffective in increasing the ICL activity (Figure 3); on the contrary, the ICL activity induced by H2O2 significantly increased at 0 and 24 h of imbibition without a decline in the ABA content (Figure 3A). Remarkably, exogenous GA obviously upregulated the expression of NtRBOH, encoded the NADPH oxidase biosynthesis genes and was involved in the generation of H2O2, triggering the accumulation of H2O2 content at 0 and 24 h of imbibition in tobacco seeds (Figure 2). It could be hypothesized that both exogenous GA and H2O2 increased the endogenous H2O2 content to enhance the expression of NtICL (Figure 11) and promote ICL activity (Figure 3); only in the case of exogenous H2O2 priming, the expression of NtICL was reflected in a significant promotion of ICL activity. The ABA/GA ratio of Uni and DPI was obviously high at 0 and 24 h (Supplementary Figure S3), but the ICL activity of Uni and DPI was low at 0 and 24 h (Figure 3); the ABA/GA ratio of GA and H2O2 kept low levels at 0 and 24 h but the ICL activity of GA and H2O2 kept high levels at 0 and 24 h. The present results support the conclusion that not the contents of ABA and GA, but the low ABA/GA ratio and the high ROS contents were both responsible for enhancing ICL activity. Previous studies by Yanik and Donaldson (2005) showed that a very high concentration of H2O2 inactivates ICL and degrades its product, glyoxylate, when CAT is inactive in castor beans. Similar results were also confirmed by Jeon et al. (2011) who showed that ICL activity was induced by a reasonable concentration H2O2 in Bradyrhizobium japonicum, as was evident at both the transcriptional and translational levels. In addition, earlier results indicated that the amounts and activities of ROS scavenging enzymes were strongly downregulated in barley treated with GA, thus increasing the H2O2 concentration. Nevertheless, ABA had the opposite effects (Fath et al., 2001). Curiously, H2O2 treatment had a weak effect on the NtRBOH expression levels (Figure 11A). In N. benthamiana, RBOH localized in the plasma membrane (PM) and the Golgi apparatus. PM-localized RBOH oxidase has been identified as a major source of ROS (Lherminier et al., 2009). ROS accumulation preceded RBOHD transcript- and protein-upregulation, indicating that ROS resulted from the activation of a PM-resident pool of enzymes, and that enzymes newly addressed to the PM were inactive (Noirot et al., 2014). Subcellular trafficking from Golgi to the PM was a potential determinant of RBOH activity, and this process regulation has mainly been addressed by considering the variation of gene expression or other signaling molecules, such as nitric oxide (NO) (Noirot et al., 2014). Both NO and ROS are known to react with each other and a balanced production between intracellular ROS and NO has been shown to be critical to the hypersensitive response (Delledonne et al., 2001). Yun et al. (2011) found that NO mediated S-nitrosylation of AtRBOHD governs a negative feedback loop limiting the production of ROS. We hypothesized that there is also feedback regulation between ROS and NtRBOH; H2O2 suppresses NtRBOH expression through other signaling when H2O2 is sufficient in the cell. Signaling activities of RBOH-derived ROS are probably also modulated by other ROS sources including xanthine oxidase, amine oxidase, and a cell wall peroxidase. It is possible that different stimuli activate specific H2O2-generating enzymes (Neill S.J. et al., 2002). Multiple source pathways of H2O2 may also be responsible for the inconsistency in H2O2 concentration and NtRBOH expression.

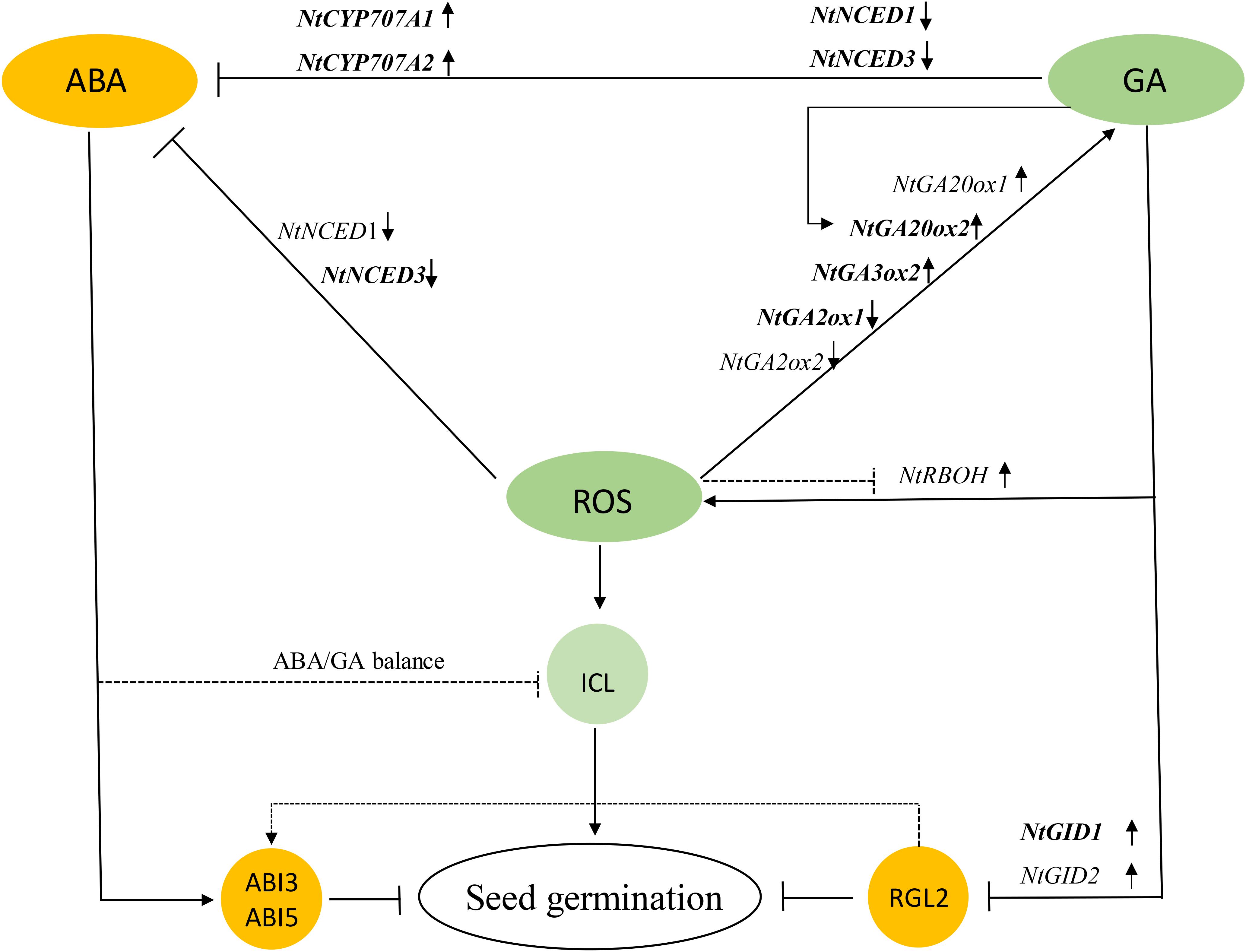

The present results show that the application of DPI and Uni increased ABA content and decreased GA content, by regulating the corresponding gene expression and, eventually, delayed the germination time and reduced the GP. The experiment revealed that H2O2 and GA were essential for tobacco seed germination mainly because of downregulating the ABA/GA ratio and inducing reserve composition mobilization to mutually promote seed germination. In addition, the potential role of ROS in seed germination was proposed that it affected the homeostasis and the signal transduction of GA and ABA by activating or inactivating gene expressions, eventually decreasing the ABA/GA ratio. ROS is also attributed to enhanced ICL activity at a higher concentration (Figure 12). However, in this work, the interaction effects between ROS, GA, and ABA were primary determined, and the underlined mechanisms need further study.

FIGURE 12. Model showing how GA, ROS, ABA, and ICL regulate seed germination. ROS led to increases in GA and decreases in ABA, where ABA inhibited seed germination and GA downregulated the DELLA Protein RGL2 suppressor to promote germination. ROS also enhanced ICL activity to directly mobilize storage reserves. GA feedback increased ROS, and on the other hand, GA inhibited the generation of ABA by downregulating ABA biosynthesis and upregulating ABA catabolism, indirectly stimulating seed germination; but a balance of these two hormones jointly controls the germination of tobacco seeds. GA, gibberellin acid; ROS, reactive oxygen species; ICL, isocitrate lyase.

ZL conceived and designed the experiments. ZL, YG, YZ, CL, and DG performed the experiments. ZL and YG analyzed the data. All authors contributed reagents, materials, and analysis tools. ZL, YG, and YJG wrote the paper.

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 31201279, 31371708, and 31671774), Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation (Nos. LY15C130002 and LZ14C130002), Science and Technology Project of Yunnan Provincial Tobacco Company (2018530000241035), Dabeinong Funds for Discipline Development and Talent Training in Zhejiang University and Jiangsu Collaborative Innovation Center for Modern Crop Production, China.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2018.01279/full#supplementary-material

Aoki, N., Ishibashi, Y., Kai, K., Tomokiyo, R., Yuasa, T., and Iwaya-Inoue, M. (2014). Programmed cell death in barley aleurone cells is not directly stimulated by reactive oxygen species produced in response to gibberellin. J. Plant Physiol. 171, 615–618. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2014.01.005

Ariizumi, T., and Steber, M. (2007). Seed germination of GA-insensitive sleepy1 mutants does not require RGL2 protein disappearance in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 19, 791–804. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.048009

Bahin, E., Bailly, C., Sotta, B., Kranner, I., Corbineau, F., and Leymarie, J. (2011). Crosstalk between reactive oxygen species and hormonal signalling pathways regulates grain dormancy in barley. Plant Cell Environ. 34, 980–993. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2011.02298.x

Bailly, C. (2013). Oxidative signalling in seed germination and dormancy. Biotechnol. J. Biotechnol. Comput. Biol. Bionanotechnol. 3, 175–182.

Bailly, C., El-Maarouf-Bouteau, H., and Corbineau, F. (2008). From intracellular signaling networks to cell death: the dual role of reactive oxygen species in seed physiology. C. R. Biol. 331, 806–814. doi: 10.1016/j.crvi.2008.07.022

Baleroni, C. R. S., Ferrarese, M. L. L., Souza, N. E., and Ferrarese-Filho, O. (2000). Lipid accumulation during canola seed germination in response to cinnamic acid derivatives. Biol. Plant. 43, 313–316. doi: 10.1023/A:1002789218415

Barba-Espín, G., Diaz-vivancos, P., Job, D., Belghazi, M., Job, C., and Hernández, J. A. (2011). Understanding the role of H2O2 during pea seed germination: a combined proteomic and hormone profiling approach. Plant Cell Environ. 34, 1907–1919. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2011.02386.x

Bau, H. M., Villaume, C., Nicolas, J. P., and Méjean, L. (1997). Effect of germination on chemical composition, biochemical constituents and antinutritional factors of soya bean (Glycine max) seeds. J. Sci. Food Agric. 73, 1–9. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0010(199701)73:1<1::AID-JSFA694>3.0.CO;2-B

Bentsink, L., and Koornneef, M. (2008). Seed dormancy and germination. Arabidopsis Book 6:e0119. doi: 10.1199/tab.0119

Borek, S., and Nuc, K. (2011). Sucrose controls storage lipid breakdown on gene expression level in germinating yellow lupine (Lupinus luteus L.) seeds. J. Plant Physiol. 168, 1795–1803. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2011.05.016

Breusegem, F. V., Bailey-Serres, J., and Mittler, R. (2008). Unraveling the tapestry of networks involving reactive oxygen species in plants. Plant Physiol. 147, 978. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.122325

Cao, D., Cheng, H., Wu, W., Soo, H. M., and Peng, J. (2006). Gibberellin mobilizes distinct DELLA-dependent transcriptomes to regulate seed germination and floral development in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 142, 509–525. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.082289

Carles, C., Bies-Etheve, N., Aspart, L., Léon-Kloosterziel, K. M., Koornneef, M., Echeverria, M., et al. (2002). Regulation of Arabidopsis thaliana Em genes: role of ABI5. Plant J. Cell Mol. Biol. 30, 373–383. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2002.01295.x

Cembrowska-Lech, D., Koprowski, M., and Kępczyn’ski, J. (2015). Germination induction of dormant Avena fatua caryopses by KAR1 and GA3 involving the control of reactive oxygen species (H2O2 and O2⋅-) and enzymatic antioxidants (superoxide dismutase and catalase) both in the embryo and the aleurone layers. J. Plant Physiol. 176, 169–179. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2014.11.010

Delledonne, M., Zeier, J., Marocco, A., and Lamb, C. (2001). Signal interactions between nitric oxide and reactive oxygen intermediates in the plant hypersensitive disease resistance response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 13454–13459. doi: 10.1073/pnas.231178298

Doulis, A. G., Debian, N., Kingston-Smith, A. H., and Foyer, C. H. (1997). Differential localization of antioxidants in maize leaves. Plant Physiol. 114, 1031–1037. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.3.1031

Eastmond, P. J., and Jones, R. L. (2005). Hormonal regulation of gluconeogenesis in cereal aleurone is strongly cultivar-dependent and gibberellin action involves SLENDER1 but not GAMYB. Plant J. 44, 483–493. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02544.x

Eckardt, N. A. (2005). Peroxisomal citrate synthase provides exit route from fatty acid metabolism in oilseeds. Plant Cell 17, 1863–1865. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.034843

Fath, A., Bethke, P. C., and Jones, R. L. (2001). Enzymes that scavenge reactive oxygen species are down-regulated prior to gibberellic acid-induced programmed cell death in barley aleurone. Plant Physiol. 126, 156–166. doi: 10.1104/pp.126.1.156

Finkelstein, R. R., and Lynch, T. J. (2000). Abscisic acid inhibition of radicle emergence but not seedling growth is suppressed by sugars. Plant Physiol. 122, 1179–1186. doi: 10.1104/pp.122.4.1179

Footitt, S., Douterelo-Soler, I., Clay, H., and Finch-Savage, W. E. (2011). Dormancy cycling in Arabidopsis seeds is controlled by seasonally distinct hormone-signaling pathways. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 20236–20241. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1116325108

Giannelos, P. N., Zannikos, F., and Stournas, S. (2002). Tobacco seed oil as an alternative diesel fuel: physical and chemical properties. Ind. Crops Prod. 16, 1–9. doi: 10.1016/S0926-6690(02)00002-X

Golldack, D., Li, C., Mohan, H., and Probst, N. (2013). Gibberellins and abscisic acid signal crosstalk: living and developing under unfavorable conditions. Plant Cell Rep. 32, 1007–1016. doi: 10.1007/s00299-013-1409-2

Gomes, M. P., and Garcia, Q. S. (2013). Reactive oxygen species and seed germination. Biologia 68, 351–357. doi: 10.2478/s11756-013-0161-y

Graham, I. A. (2008). Seed storage oil mobilization. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 59, 115–142. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.59.032607.092938

Griffiths, J., Murase, K., Rieu, I., Zentella, R., Zhang, Z. L., Powers, S. J., et al. (2006). Genetic characterization and functional analysis of the GID1 gibberellin receptors in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 18, 3399–3414. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.047415

Gu, J., Chao, H., Gan, L., Guo, L., Zhang, K., Li, Y., et al. (2016). Proteomic dissection of seed germination and seedling establishment in Brassica napus. Front. Plant Sci. 7:637. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01482

Guo, B., Chen, Y., Zhang, G., Xing, J., Hu, Z., Feng, W., et al. (2013). Comparative proteomic analysis of embryos between a maize hybrid and its parental lines during early stages of seed germination. PLoS One 8:e65867. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065867

Han, C., Yin, X., He, D., and Yang, P. (2013). Analysis of proteome profile in germinating soybean seed, and its comparison with rice showing the styles of reserves mobilization in different crops. PLoS One 8:e56947. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056947

Huang, Y., Lin, C., He, F., Li, Z., Guan, Y., Hu, Q., et al. (2017). Exogenous spermidine improves seed germination of sweet corn via involvement in phytohormone interactions, H2O2 and relevant gene expression. BMC Plant Biol. 17:1. doi: 10.1186/s12870-016-0951-9

International Seed Testing Association [ISTA]. (2010). International Rules for Seed Testing. Bassersdorf: International Seed Testing Association.

Ishibashi, Y., Tawaratsumida, T., and Zheng, S. H. (2010). NADPH oxidases act as key enzyme on germination and seedling growth in Barley (L.). Plant Prod. Sci. 13, 45–52. doi: 10.1626/pps.13.45

Jeon, J. M., Lee, H. I., Donati, A. J., So, J. S., Emerich, D. W., and Chang, W. S. (2011). Whole-genome expression profiling of Bradyrhizobium japonicum in response to hydrogen peroxide. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 24, 1472–1481. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-03-11-0072

Kelly, A. A., Quettier, A. L., Shaw, E., and Eastmond, P. J. (2011). Seed storage oil mobilization is important but not essential for germination or seedling establishment in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 157, 866–875. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.181784

Kupidłowska, E., Gniazdowska, A., Stępień, J., Corbineau, F., Vinel, D., Skoczowski, A., et al. (2006). Impact of sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) extracts upon reserve mobilization and energy metabolism in germinating mustard (Sinapis alba L.) seeds. J. Chem. Ecol. 32, 2569–2583. doi: 10.1007/s10886-006-9183-z

Lherminier, J., Elmayan, T., and Fromentin, J. (2009). NADPH oxidase-mediated reactive oxygen species production: subcellular localization and reassessment of its role in plant defense. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 22, 868–881. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-22-7-0868

Li, W., Liu, X., Khan, M. A., Kamiya, Y., and Yamaguchi, S. (2005). Hormonal and environmental regulation of seed germination in flixweed (Descurainia sophia). Plant Growth Regul. 45, 199–207. doi: 10.1007/s10725-005-4116-3

Li, X. X., and Li, J. Z. (2013). Determination of the content of soluble sugar in sweet corn with optimized anthrone colorimetric method. Storage Process 13, 24–27.

Li, Z., Xu, J., Gao, Y., Wang, C., Guo, G., Luo, Y., et al. (2017). The synergistic priming effect of exogenous salicylic acid and H2O2 on chilling tolerance enhancement during maize (Zea mays L.) seed germination. Front. Plant Sci. 8:1153. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.01153

Lim, S., Park, J., Lee, N., Jeong, J., Toh, S., Watanabe, A., et al. (2013). ABA-INSENSITIVE3, ABA-INSENSITIVE5, and DELLAs interact to activate the expression of SOMNUS and other high-temperature-inducible genes in imbibed seeds in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 25, 4863–4878. doi: 10.1105/tpc.113.118604

Liu, X., Hu, P., Huang, M., Tang, Y., Li, Y., Li, L., et al. (2016). The NF-YC-RGL2 module integrates GA and ABA signalling to regulate seed germination in Arabidopsis. Nat. Commun. 7:12768. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12768

Liu, X., Zhang, H., Zhao, Y., Feng, Z., Li, Q., Yang, H. Q., et al. (2013). Auxin controls seed dormancy through stimulation of abscisic acid signaling by inducing ARF-mediated ABI3 activation in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 15485–15490. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1304651110

Liu, Y., Ye, N., Liu, R., Chen, M., and Zhang, J. (2010). H2O2 mediates the regulation of ABA catabolism and GA biosynthesis in Arabidopsis seed dormancy and germination. J. Exp. Bot. 61, 2979–2990. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erq125

Livak, K. J., and Schmittgen, T. D. (2001). Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2- ΔΔCT method. Methods 25, 402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262

Maarouf, B., Sajjad, Y., Bazin, J., Langlade, N., Cristescu, S. M., Balzergue, S., et al. (2015). Reactive oxygen species, abscisic acid and ethylene interact to regulate sunflower seed germination. Plant Cell Environ. 38, 364–374. doi: 10.1111/pce.12371

Marriott, K. M., and Northcote, D. H. (1977). The influence of abscisic acid, adenosine 3′, 5′ cyclic phosphate, and gibberellic acid on the induction of isocitrate lyase activity in the endosperm of germinating castor bean seeds. J. Exp. Bot. 28, 219–224. doi: 10.1093/jxb/28.1.219

Meyer, K., Stecca, K. L., Ewell-Hicks, K., Allen, S. M., and Everard, J. D. (2012). Oil and protein accumulation in developing seeds is influenced by the expression of a cytosolic pyrophosphatase in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 159, 1221. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.198309

Moller, I. M. (2001). Plant mitochondria and oxidative stress: electron transport, NADPH turnover, and metabolism of reactive oxygen species. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 52, 561–591. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.52.1.561

Möller, I. M., and Sweetlove, L. J. (2010). ROS signalling -specificity is required. Trends Plant Sci. 15, 370–374. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2010.04.008

Morré, D. J. (2002). Preferential inhibition of the plasma membrane NADH oxidase (NOX) activity by diphenyleneiodonium chloride with NADPH as donor. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 4, 207–212. doi: 10.1089/152308602753625960

Müller, K., Carstens, A. C., Linkies, A., Torres, M. A., and Leubner-Metzger, G. (2009). The NADPH-oxidase AtrbohB plays a role in Arabidopsis seed after-ripening. New Phytol. 184, 885–897. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.03005.x

Neill, S., Desikan, R., and Hancock, J. (2002). Hydrogen peroxide signalling. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 5, 388–395. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5266(02)00282-0

Neill, S. J., Desikan, R., Clarke, A., Hurst, R. D., and Hancock, J. T. (2002). Hydrogen peroxide and nitric oxide as signalling molecules in plants. J. Exp. Bot. 53, 1237–1247. doi: 10.1093/jexbot/53.372.1237

Noirot, E., Der, C., Lherminier, J., and Robert, F. (2014). Dynamic changes in the subcellular distribution of the tobacco ROS-producing enzyme RBOHD in response to the oomycete elicitor cryptogein. J. Exp. Bot. 65, 5011–5022. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eru265

Penfield, S., Li, Y., Gilday, A. D., Graham, S., and Graham, I. A. (2006). Arabidopsis ABA INSENSITIVE4 regulates lipid mobilization in the embryo and reveals repression of seed germination by the endosperm. Plant Cell 18, 1887–1899. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.041277

Piskurewicz, U., Jikumaru, Y., Kinoshita, N., Nambara, E., Kamiya, Y., and Lopez-Molina, L. (2008). The gibberellic acid signaling repressor RGL2 inhibits Arabidopsis seed germination by stimulating abscisic acid synthesis and ABI5 activity. Plant Cell 20, 2729–2745. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.061515

Pritchard, S. L., Charlton, W. L., Baker, A., and Graham, I. A. (2002). Germination and storage reserve mobilization are regulated independently in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 31, 639–647. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2002.01376.x

Raineri, J., Hartman, M. D., Chan, R. L., Iglesias, A. A., and Ribichich, K. F. (2016). A sunflower WRKY transcription factor stimulates the mobilization of seed-stored reserves during germination and post-germination growth. Plant Cell Rep. 35, 1875–1890. doi: 10.1007/s00299-016-2002-2

Razem, F. A., Baron, K., and Hill, R. D. (2006). Turning on gibberellin and abscisic acid signaling. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 9, 454–459. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2006.07.007

Selmar, D., Bytof, G., Knopp, S. E., and Breitenstein, B. (2006). Germination of coffee seeds and its significance for coffee quality. Plant Biol. 8, 260–264. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-923845

Seo, M., Hanada, A., and Kuwahara, A. (2006). Regulation of hormone metabolism in Arabidopsis seeds: phytochrome regulation of abscisic acid metabolism and abscisic acid regulation of gibberellin metabolism. Plant J. Cell Mol. Biol. 48, 354–366. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02881.x

Stamm, P., Ravindran, P., Mohanty, B., Tan, E., Yu, H., and Kumar, P. (2012). Insights into the molecular mechanism of RGL2-mediated inhibition of seed germination in Arabidopsis thaliana. BMC Plant Biol. 12:179. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-12-179

Toh, S., Imamura, A., Watanabe, A., Nakabayashi, K., Okamoto, M., and Jikumaru, Y. (2008). High temperature induced abscisic acid biosynthesis and its role in the inhibition of gibberellin action in Arabidopsis seeds. Plant Physiol. 146, 1368–1385. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.113738

Topham, A. T., Taylor, R. E., Yan, D., Nambara, E., Johnston, I. G., and Bassel, G. W. (2017). Temperature variability is integrated by a spatially embedded decision-making center to break dormancy in Arabidopsis seeds. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, 201704745. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1704745114

Weiss, D., and Ori, N. (2007). Mechanisms of cross talk between gibberellin and other hormones. Plant Physiol. 144, 1240–1246. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.100370

Wu, M., Li, J., Wang, F., Li, F., Yang, J., and Shen, W. (2014). Cobalt alleviates GA-induced programmed cell death in wheat aleurone layers via the regulation of h2o2 production and heme oxygenase-1 expression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 15, 21155–21178. doi: 10.3390/ijms151121155

Yan, D., Duermeyer, L., Leoveanu, C., and Nambara, E. (2014). The functions of the endosperm during seed germination. Plant Cell Physiol. 55, 1521–1533. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcu089

Yang, D. L., Yao, J., Mei, C. S., Tong, X. H., Zeng, L. J., Li, Q., et al. (2012). Plant hormone jasmonate prioritizes defense over growth by interfering with gibberellin signaling cascade. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 1192–1200. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1201616109

Yanik, T., and Donaldson, R. P. (2005). A protective association between catalase and isocitrate lyase in peroxisomes. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 435, 243–252. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2004.12.017

Ye, N., and Zhang, J. (2012). Antagonism between abscisic acid and gibberellins is partially mediated by ascorbic acid during seed germination in rice. Plant Signal. Behav. 7, 563–565. doi: 10.4161/psb.19919

Yun, B. W., Feechan, A., Yin, M., Saidi, N. B., Le, Bihan T, Yu, M., et al. (2011). S-nitrosylation of NADPH oxidase regulates cell death in plant immunity. Nature 478, 264–268. doi: 10.1038/nature10427

Zentella, R., Zhang, Z. L., Park, M., Thomas, S. G., Endo, A., Murase, K., et al. (2007). Global analysis of DELLA direct targets in early gibberellin signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 19, 3037–3057. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.054999

Keywords: tobacco seed, germination, H2O2, GA, ABA, homeostasis, signal transduction

Citation: Li Z, Gao Y, Zhang Y, Lin C, Gong D, Guan Y and Hu J (2018) Reactive Oxygen Species and Gibberellin Acid Mutual Induction to Regulate Tobacco Seed Germination. Front. Plant Sci. 9:1279. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.01279

Received: 20 April 2018; Accepted: 15 August 2018;

Published: 02 October 2018.

Edited by:

Francisco Javier Cejudo, Universidad de Sevilla, SpainReviewed by:

Sara Maldonado, Universidad de Buenos Aires, ArgentinaCopyright © 2018 Li, Gao, Zhang, Lin, Gong, Guan and Hu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yajing Guan, dmNndWFuQHpqdS5lZHUuY24=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.