94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Plant Sci. , 06 February 2018

Sec. Plant Development and EvoDevo

Volume 9 - 2018 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2018.00102

Flower organ patterning is accomplished by spatial and temporal functioning of various regulatory genes. We previously reported that Oryza sativa VIN3-LIKE 2 (OsVIL2) induces flowering by mediating the trimethylation of Histone H3 on LFL1 chromatin. In this study, we report that OsVIL2 also plays crucial roles during spikelet development. Two independent lines of T-DNA insertional mutants in the gene displayed altered organ numbers and abnormal morphology in all spikelet organs. Scanning electron microscopy showed that osvil2 affected organ primordia formation during early spikelet development. Expression analysis revealed that OsVIL2 is expressed in all stages of the spikelet developmental. Transcriptome analysis of developing spikelets revealed that several regulatory genes involved in that process and the formation of floral organs were down-regulated in osvil2. These results suggest that OsVIL2 is required for proper expression of the regulatory genes that control floral organ number and morphology.

Grasses have a unique inflorescence unit, the spikelet, that contains a different number of florets and glumes depending on species (Bommert et al., 2005). The spikelet of rice (Oryza sativa) consists of two rudimentary glumes, two empty glumes, and a single floret (Bommert et al., 2005). Each floret is composed of a lemma, a palea, two lodicules on the palea side, six stamens, and a carpel (Yoshida and Nagato, 2011).

APETALA2/ethylene responsive factor (AP2/ERF) family genes, SUPERNUMERARY BRACT (SNB), and INDETERMINATE SPIKELET1 (IDS1), play crucial roles in the transition from spikelet meristem (SM) to floral meristem (FM) (Lee et al., 2007; Lee and An, 2012). Their mutant lines produce repetitive glumes and show an abnormal floral organ pattern due to extended activity of SM. Another AP2/ERF gene, MULTI-FLORET SPIKELET1 (MFS1), also has a role in regulating SM fate. In mfs1 mutants, additional lemma-like organs and elongated rachilla are produced, and empty glumes and palea are degenerated (Ren et al., 2013). These results suggest that proper transition from SM to FM is needed for normal spikelet development.

Analysis of various rice mutants has revealed several genes involved in glume development. For example, mutations in EXTRA GLUME1 (EG1) and EG2/OsJAZ1, which function in jasmonic acid signaling, cause abnormal spikelet phenotypes. Empty glumes are transformed into lemma-like organs and extra glumes are produced (Li et al., 2009; Cai et al., 2014). In addition, floral organ identity and number are affected. These changes are probably due to altered expression of OsMADS1 in the mutants (Jeon et al., 2000a; Prasada et al., 2005). Similar phenotypes are observed for rice INDETERMINATE GAMETOPHYTE1 (OsIG1) RNAi plants (Zhang et al., 2015). Mutations in long sterile lemma (G1) are associated with homeotic transformation of the sterile lemma to a lemma, suggesting that the gene represses lemma identity to specify sterile lemma (Yoshida et al., 2009). Mutations of OsMADS34 cause pleiotropic effects including alteration of empty glumes into lemma-like organs (Gao et al., 2010).

The development of palea is retarded in mutants defective in RETARDED PALEA1 (REP1) (Yuan et al., 2009). DEPRESSED PALEA 1 (DP1), encoding AT-hook DNA binding protein, also plays a crucial role in palea development (Jin et al., 2011). Mutations of that gene cause a palea defect as well as an increase in floral organ numbers. Expression analyses have indicated that DP1 functions upstream of REP1. Mutations of OsMADS15 also result in defective palea (Wang et al., 2010), while those of OsMADS6 also have disturbed palea and altered carpel development (Ohmori et al., 2009; Li et al., 2010). Mutations of OsMADS32 are linked with defective marginal regions for palea and ectopic floral organs (Sang et al., 2012).

Polycomb group proteins (PcG) are epigenetic repressors that control gene expression (Mozgova and Hennig, 2015). They function in various developmental processes by forming Polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2), which inhibits target chromatins through the trimethylation of Histone 3 lysine 27 (H3K27me3) (Cao et al., 2002; Czermin et al., 2002; Müller et al., 2002; Nekrasov et al., 2005). PRC2 controls FM initiation, organ identity specification, and meristem termination (Gan et al., 2013).

The PRC2 has several components. In Arabidopsis, mutants of the core components of PRC2 – CLF/SWN, FIE, EMF2, and MSI – present ectopic expression of AGAMOUS (AG), causing abnormal floral phenotypes similar to those of AG-overexpression plants (Goodrich et al., 1997; Yoshida et al., 2001; Hennig et al., 2003; Moon et al., 2003; Katz et al., 2004). This complex also influences FM termination by regulating the temporal expression of WUSCHEL (WUS) and KNUCKLES (KNU) (Mozgova et al., 2015). After all of the floral organs are initiated, FM is terminated through the repression of WUS, a meristem maintenance gene (Mayer et al., 1998). PRC2 inhibits the expression of KNU, which inhibits WUS transcription (Lenhard et al., 2001; Sun et al., 2009). For floral termination, activated AG displaces PRC2 from KNU, leading to activation of KNU and repression of WUS (Sun et al., 2014).

VERNALIZATION INSENSITIVE 3 (VIN3), another component of PRC2, enhances H3K27me3 in FLOWERING LOCUS C (FLC), a repressor of flowering (Sung and Amasino, 2004). In rice, the VIN3-LIKE protein OsVIL2 enhances flowering by mediating H3K27me3 on chromatin of LFL1, which is a negative regulator of flowering (Yang et al., 2013). OsVIL2 binds to OsEMF2b, an ortholog of Arabidopsis EMF2 (Yang et al., 2013). Mutants in OsEMF2b display phenotypes of severe floral organ defects and meristem indeterminacy, similar to the mutants defective in E-function genes OsMADS1, OsMADS6, and OsMADS34 (Luo et al., 2009; Yang et al., 2013; Conrad et al., 2014; Xie et al., 2015). OsEMF2b represses the expression of these E-function genes by altering H3K27me3 on their chromatins (Conrad et al., 2014). In addition, OsEMF2b inhibits OsLFL1 and OsMADS4 by mediating H3K27me3 on their chromatin, resulting in the promotion of flowering and regulating the specification of floral organ identity (Xie et al., 2015).

The osvil2 mutants also display abnormal spikelet development. In this study, we studied the mutant phenotypes that appear in the early stages of that process and performed transcriptome analysis to identify downstream genes controlled by OsVIL2.

Two OsVIL2 mutant lines, osvil2-1 and osvil2-2, were isolated from a pool of rice T-DNA tagging lines (Jeon et al., 2000b; Jeong et al., 2002; Yang et al., 2013). Seeds of the mutants and wild type (WT) were germinated on MS media and genotyping was conducted to identify homozygous plants, as previously explained (Yi and An, 2013). Plants were grown either in the paddy field under natural conditions or in a greenhouse under supplemental, artificial lighting.

For OsVIL2 promoter – GUS fusion construction, we used the 2,348-bp promoter fragment between -2340 and +8 from the translation initiation site of OsVIL2 that was used for complementation of the mutant (Zhao et al., 2010). The fragment was amplified by PCR and placed upstream of the promoterless GUS gene using the pGA3519 binary vector that contains hygromycin selectable marker. The primer sequences for amplification of the promoter region are listed in Supplementary Table S1. Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain LBA4404 was transformed with this vector by the freeze-thaw method (An et al., 1989). Transgenic plants expressing the GUS reporter gene were generated by co-cultivating the Agrobacterium cells with scutellum calli derived from mature seeds of rice (cv. Longjin). The co-cultivated calli were selected and regenerated as previously reported (Jeon et al., 1999).

Plant tissues were submerged in GUS-staining solution that contained 100 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.0), 0.1 mM potassium ferricyanide, 0.1 mM potassium ferrocyanide, 0.1% Triton X-100, 10 mM EDTA (pH 8.0), 1% DMSO, 0.1% X-gluc (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-D-glucuronic acid/cyclohexylammonium salt), and 5% methanol (Yoon et al., 2014). Samples were incubated overnight at 37°C, then transferred to 70% ethanol at 65°C for several hours to remove chlorophylls before being stored in 95% ethanol.

Specimens were prepared as previously described (Lee et al., 2007). Samples were fixed in FAA solution, dehydrated in an ethanol series, and critical point-dried in a Leica EM CPD300 (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany). They were mounted on stubs, sputter-coated with platinum, and observed under a scanning electron microscope (SIGMA FE-SEM; Carl Zeiss, Germany).

Total RNAs were isolated with RNAiso Plus (TaKaRa, Shiga, Japan). The cDNAs were synthesized with 2 μg of RNA, Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Promega, Madison, WI, United States), RNasin Ribonuclease Inhibitor (Promega), 10 ng of the oligo (dT)18 primer, and 2.5 mM deoxyribonucleotide triphosphates. Quantitative RT-PCR was conducted with SYBR Green I Prime Q-Mastermix (GENETBIO, Daejeon, South Korea) and a Rotor-Gene 6000 (Corbett Research, Sydney, NSW, Australia), following protocols reported earlier (Yang et al., 2013; Wei et al., 2016). Rice Ubiquitin1 was used as an internal control for quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR).

For transcriptome analyses, total RNAs were prepared from 2- and 4-mm panicles of WT and osvil2-1 plants, in three biological replicates. Double-stranded cDNAs were synthesized with random hexamers and ligated to adaptors. This library was pair-end sequenced using the PE90 strategy on an Illumina HiSeqTM 2000 at the Beijing Genomics Institute (Wuhan, China). The DEseq algorithm was applied to filter the differentially expressed genes. All Gene Ontology (GO) annotations were downloaded from NCBI1, UniProt2, and the Gene Ontology website3. The RNA sequencing data were deposited to the GEO database (accession number: GSE108538).

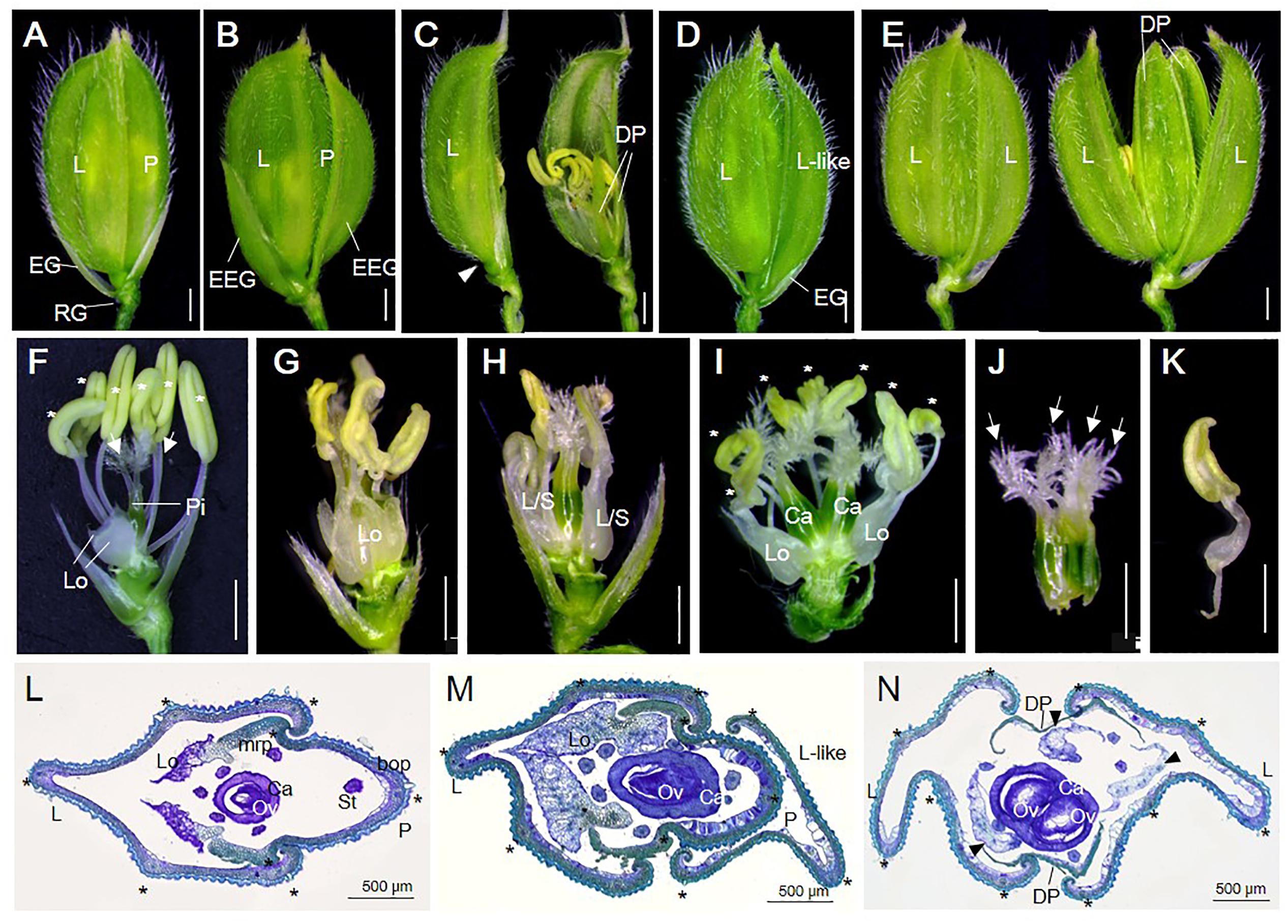

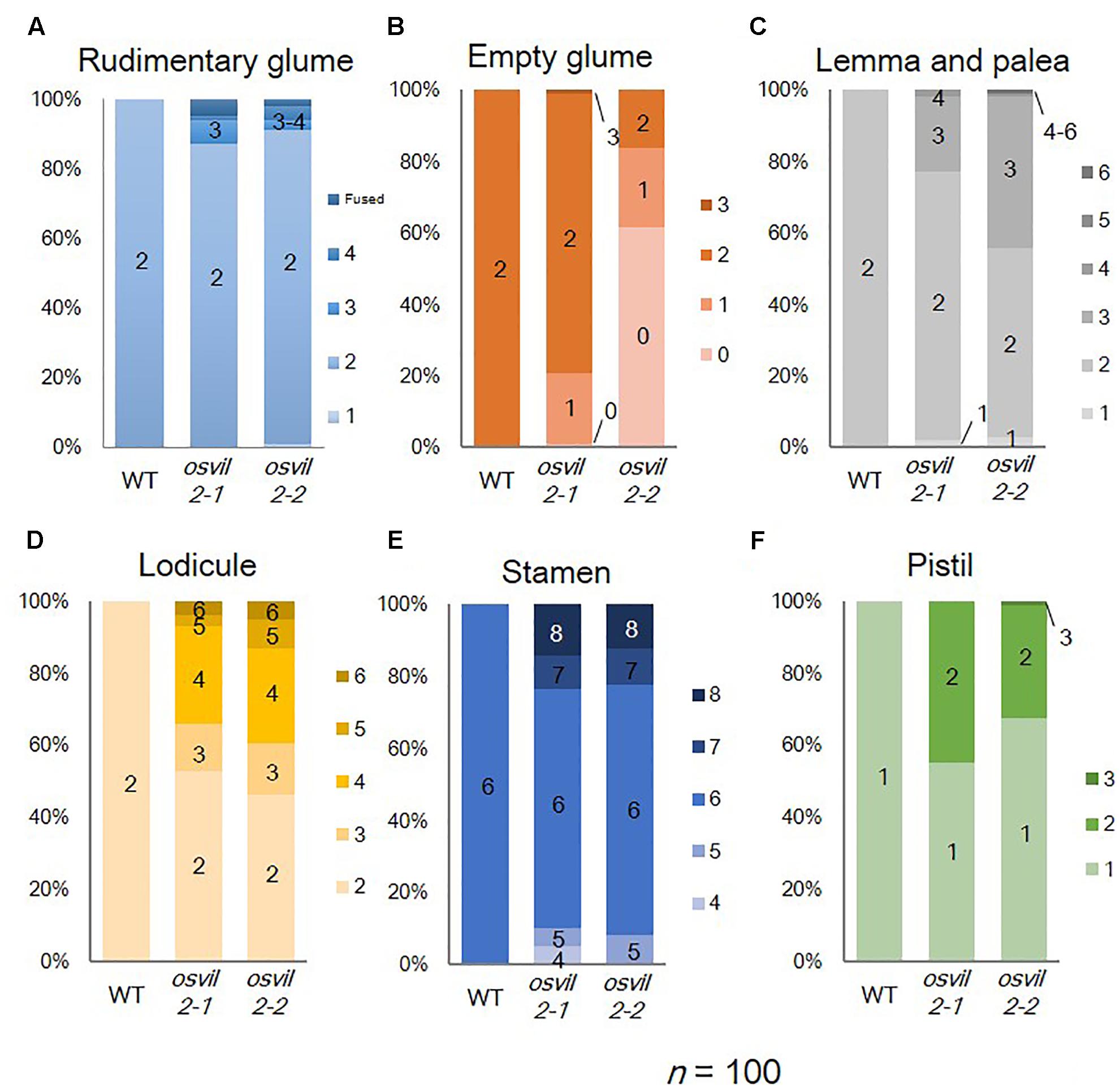

We previously showed that T-DNA insertional mutant lines osvil2-1 and osvil2-2 display pleiotropic phenotypes, including late-flowering, fewer tillers, and abnormal spikelet development (Yang et al., 2013). In this study we characterized the spikelet defects in detail (Figure 1 and Supplementary Figure S1). The WT spikelets had a pair of rudimentary glumes plus empty glumes (Figure 1A). In contrast, the number of rudimentary glumes was increased in 14% of the osvil2 spikelets (Figure 2A). Furthermore, the empty glumes were elongated in 21% of the mutant spikelets (Figure 1B and Supplementary Figure S1B), while the number of empty glumes was decreased in 21%, resulting in spikelets with one or no empty glumes (Figures 1C, 2B). Occasionally, a lemma-like organ developed at the position of the empty glume. These observations indicated that mutations of OsVIL2 affected both the number and morphology of empty glumes.

FIGURE 1. Spikelet phenotypes of WT and osvil2 mutant. (A–E) Phenotypes of WT and osvil2-1 spikelets. (A) WT spikelet with pair of rudimentary glumes and empty glumes, lemma, palea. (B) osvil2-1 spikelet with elongated empty glumes. (C) osvil2-1 spikelet with degenerated palea and no empty glume on lemma side (arrowhead). (D) osvil2-1 spikelet with additional lemma-like organ. (E) osvil2-1 spikelet with 2 lemma and 2 degenerated palea. (F–K) Phenotypes of inner floral organs of WT and osvil2-1. Palea and lemma were removed. (F) WT spikelet comprises two lodicules on lemma side, six stamens (asterisks), and one pistil with two stigmas (arrows). (G) osvil2-1 floret with extra lodicules and immature stamens. (H) osvil2-1 floret with lodicule–stamen mosaic organs. (I) osvil2-1 floret with extra lodicules, seven stamens (asterisks), and two carpels. (J) osvil2-1 carpel in which several carpels are fused. Number of stigma is also increased (arrows). (K) Lodicule–stamen mosaic organ in osvil2-1. (L) Cross section of WT spikelet. (M,N) Cross section of osvil2 spikelet. (M) Formation of additional lemma-like organ in osvil2 spikelet. (N) osvil2 with two lemma, two degenerated palea, three abnormal lodicules (arrow heads), and one fused carpel having two ovules. bop, body of palea; Ca, carpel; DP, depressed palea; EG, empty glume; EEG, elongated empty glume; L, lemma; Lo, lodicule; L/S, lodicule–stamen mosaic organ; L-like; lemma-like organ; mrp, marginal region of palea; Ov, ovule; P, palea; RG, rudimentary glume. Asterisks indicate stamens (F,I) or vascular bundles (L–N). Scale bars = 1 mm (A–K) or 500 μm (L–N).

FIGURE 2. Floral organ numbers in WT, osvil2-1, and osvil2-2 spikelets. (A) Rudimentary glumes; (B) empty glumes; (C) lemma and palea; (D) lodicules; (E) stamens; (F) pistils.

In addition, the development of all floral organs was abnormal in the osvil2 florets. Extra lemma-like structures were observed in 45% of the osvil2 spikelets, creating three or more such structures (Figures 1D, 2C and Supplementary Figure S1C). Additional lemma-like organs were often produced at an ectopic whorl. Some of those ectopic lemma-like organs resembled lemma (Figure 1D). The number of lemma was increased in 14% of the spikelets from osvil2, and they often accompanied degenerated palea (Figures 1E, 2C). The development of palea was defective in 33% of those mutants (Figure 1C and Supplementary Figure S1D), and cross sections of the spikelets showed extra lemma-like organs (Figure 1M) and degenerated palea (Figure 1N).

The number of lodicules increased to three or more in 54% of the osvil2 spikelets (Figures 1G–I, 2D and Supplementary Figures S1F,G), and their morphology was occasionally abnormal. Lodicules were elongated (20%) or an anther-like organ formed in the upper part of 26% of those lodicules (Figures 1 H,I,K). The number of stamens decreased in 8% of the spikelets (Figures 1H, 2E) but increased in 22% (Figures 1I, 2E). Finally, the number of carpels rose to two in 32% of the mutant spikelets (Figures 1I, 2F) and they were often fused (Figures 1 H,J). These observations indicated that OsVIL2 is needed for proper development of all organs within a spikelet.

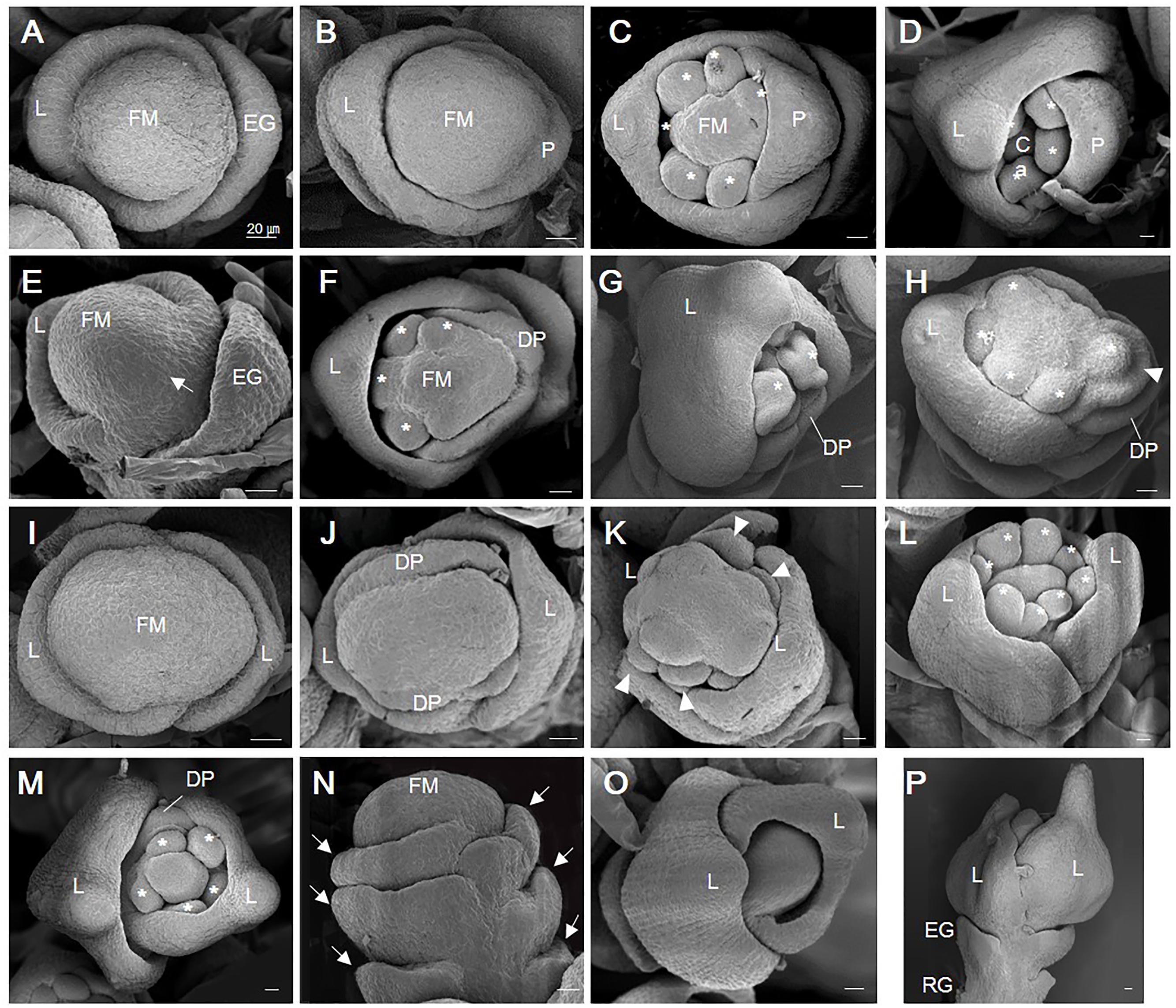

We used a scanning electron microscope to study spikelet defects during early developmental stages that were classified based on the previous research (Ikeda et al., 2004). In the WT, the FM produced an empty glume and a lemma on the opposite side of the empty glume during spikelet developmental stage Sp3 in the WT (Figure 3A). Palea subsequently developed in Stages 4–5 (Figure 3B). While the lemma and palea were elongating, stamens developed at Stage 6 (Figure 3C). Finally, a carpel arose at the central position of the spikelet at Stage 8 (Figure 3D).

FIGURE 3. Scanning electron micrographic images of WT and osvil2 spikelets during early developmental stages. (A–D) WT spikelets. (A) Stage Sp3 during lemma primordia formation. (B) Stage Sp4-5 of palea primordia formation; possibly two lodicule primordia are initiating inside lemma. (C) Stage Sp6, with formation of six stamen primordia (asterisk). (D) Stage Sp8, with carpel primordia initiation during growth of lemma and palea. (E–H) Retarded palea growth in osvil2 spikelets. (E) Stage Sp4, showing retardation of palea primordia (arrow) when compared with lemma growth. (F) Stage Sp6, with degenerated palea formation and retarded stamen primordia formation on palea side. (G) Stage Sp8, with retarded growth of palea compared with lemma. (H) Stage Sp6, showing formation of stamen primordia (asterisk) in irregular pattern. Additional organ primordia (arrow head) between palea and stamen, increasing size of floral whorl. (I–L) osvil2 spikelet with twin-flower phenotype. (I) Stage Sp3, with wider floral meristem and two lemma primordia on both sides. (J) Stage Sp4, with two degenerated palea primordia forming in middle of two lemma. (K) Stage Sp6, representing ectopic organ primordia (arrow heads) likely to produce additional palea and lodicules. (L) Stage Sp6-7, with eight stamen primordia produced. (M–P) osvil2 spikelet with additional glume or lemma-like organs. (M) Stage Sp7, in which number of stamen primordia is reduced to 5. Floral whorls are increased and degenerated palea form after additional lemma. (N) Stage Sp4, with formation of additional glume primordia (arrows). (O) Stage Sp6, in which additional lemma are produced while inner organ formation is delayed. (P) Stage Sp8, with additional lemma produced after formation of normal empty glumes and rudimentary glumes. Ca, carpel; DP, degenerated palea; EG, empty glume; FM, floral meristem; L, lemma; P, palea; RG, rudimentary glume. Scale bars = 20 μm.

In osvil2 spikelets, the formation of palea primordia was often retarded at Sp4 (Figure 3E). At Sp6, the mutant spikelets displayed degenerated palea primordia, often along with retarded development of inner floral organs on the palea side (Figures 3F,G). This retardation seemed to cause a decline in the number of stamens produced as well as abnormal development of inner floral organs (Figure 3H). The FM were larger in some osvil2 spikelets that usually accompanied two lemma primordia and two degenerated palea primordia (Figures 3I,J). At Sp6, additional lodicule primordia were observed between the lemma and stamen primordia (Figure 3K). During that stage, the number of stamen primordia was altered (Figures 3L,M), and reiterative formation of glumes occurred occasionally (Figure 3N). Extra glumes and lemma-like organs were produced at additional whorls (Figures 3M–P). These findings indicated that OsVIL2 functions during the early stages of spikelet development.

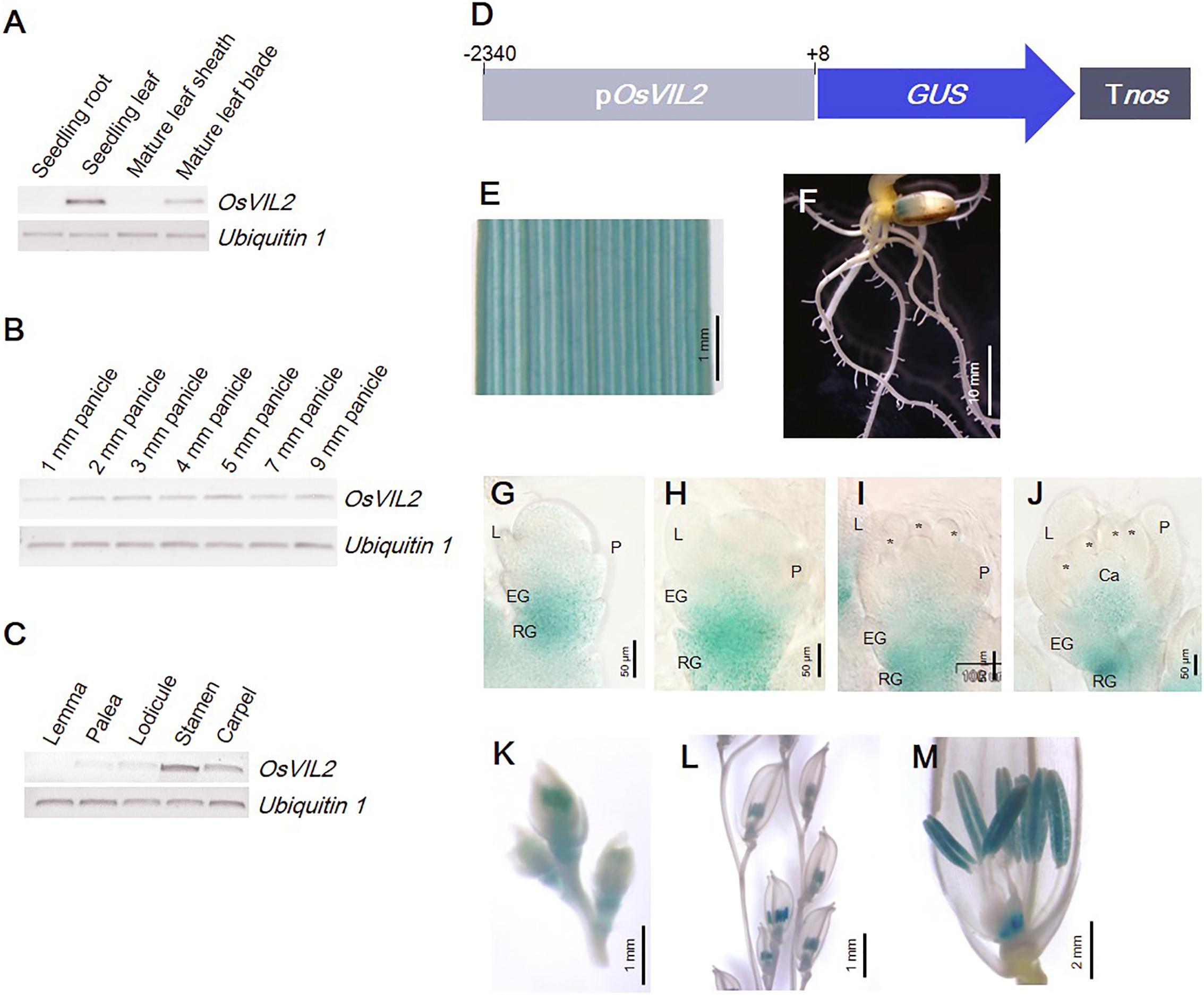

The pattern of OsVIL2 expression was analyzed by RT-PCR. In vegetative tissues, the gene was detected in seedling leaves and in the leaf blades of mature plants (Figure 4A). It was also constitutively expressed in panicles at various developmental stages (Figure 4B). In mature spikelets, expression was strong in the stamens and carpels and weak in the lodicules and palea (Figure 4C). Expression was also studied at the tissue level by using the promoter region of OsVIL2 fused to the GUS reporter gene (Figure 4D). We obtained 13 plants independently transformed with this OsVIL2 promoter-GUS construct. Those lines displayed similar expression pattern, thus we selected the line with the highest GUS expression for further analysis. The GUS reporter was expressed strongly in leaves but not expressed in roots, as observed from the RT-PCR analyses (Figures 4E,F). During spikelet development, the reporter was detected in the basal regions of the spikelets (Figures 4G–J). In florets at Sp8, it was strongly expressed in anthers and the basal region of carpels (Figures 4K–M). This organ-preferential expression pattern was consistent with the pattern revealed from the qRT-PCR data.

FIGURE 4. Expression pattern of OsVIL2 in various organs. (A–C) RT-PCR expression analysis. (A) Expression in various organs. (B) Expression during early spikelet development. (C) Expression in each floral organ within mature spikelets. (D) Schematic diagram of pOsVIL2::GUS construct. (E–M) Observation of promoter-GUS trapping line of OsVIL2. Expression in leaf blade (E), root (F), spikelet at Sp4 (G), spikelet at Sp5 (H), spikelet at Sp6 (I), spikelet at Sp7 (J), spikelets in 12-mm young panicle (K), spikelets in 50-mm panicle (L), and mature spikelet (M). EG, empty glume; L, lemma; P, palea; RG, rudimentary glume.

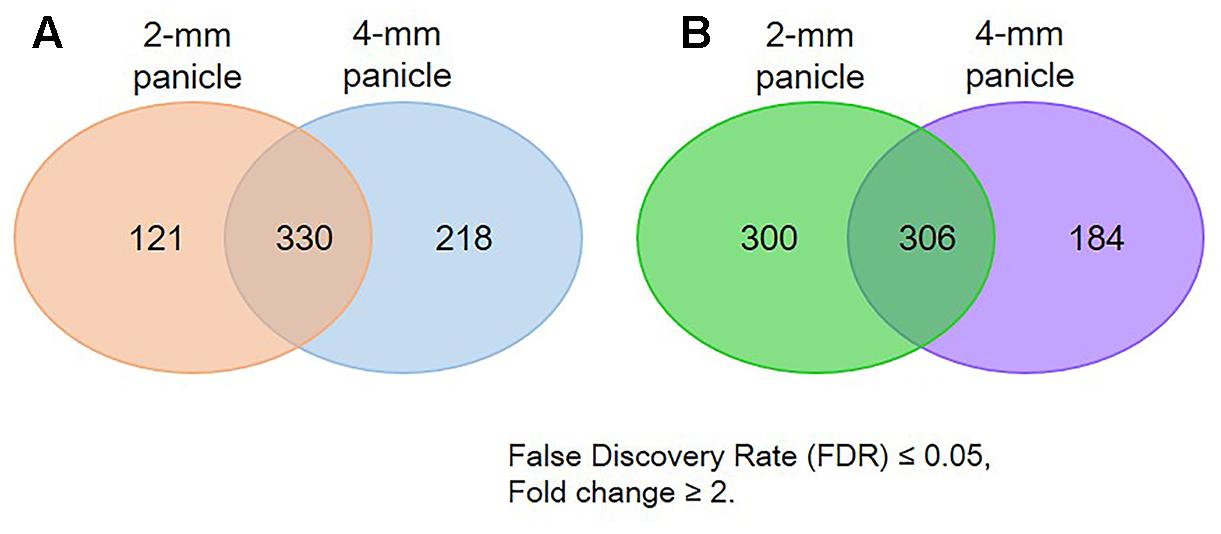

RNA-sequencing assays were conducted to identify genes differentially expressed in osvil2 during early spikelet development. Two stages were examined: 2-mm panicles containing spikelets mostly at Sp4 or earlier, and 4-mm panicles containing spikelets at mainly Sp7 or younger. In the 2-mm samples, 451 genes were up-regulated (Supplementary Table S2) and 606 genes were down-regulated (Supplementary Table S3) by at least twofold. In the 4-mm samples, 548 genes were up-regulated (Supplementary Table S4) and 490 genes were down-regulated (Supplementary Table S5) by at least twofold. The overlap between 2- and 4-mm samples showed that 330 genes were up-regulated (Supplementary Table S6) while 306 were down-regulated (Supplementary Table S7). In total, 669 genes were up-regulated and 790 genes were down-regulated by at least twofold in both size classes (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5. Number of genes differentially expressed in osvil2 young panicles. (A) Number up-regulated; (B) number down-regulated.

We performed GO analysis using the differentially expressed genes (Supplementary Figure S2). Our GO analysis revealed that Flower Development (GO:0009908) was significantly enriched for the downregulated genes in 2-mm panicles, which implied that the regulatory genes involved in that process were suppressed in osvil2 at the early stages. Terms for Transcription (GO:0006351) and Regulation of Transcription (GO:0006355) were also highly enriched for the downregulated genes from both panicle sizes (Supplementary Figures S2B,D). Among the transcription factors, many of the AP2 and MADS-box family genes were significantly down-regulated (Supplementary Table S3). Because several genes within those families play important functions in SM formation and floral organ development, their downregulation in developing panicles was likely the reason for the abnormal spikelet phenotypes.

Transcriptome analyses of the genes involved in meristem phase transition or spikelet organ development are shown in Table 1. Genes determining meristem size – FON1, FON4, and OsWUS (Suzaki et al., 2004; Chu et al., 2006; Moon et al., 2006; Nardmann and Werr, 2006) – were almost equally expressed in the osvil2 mutants. Among the genes that function in the transition from inflorescence meristem (IM) to SM, the transcriptome frequency of APO1 was significantly reduced in both panicle sizes. APO1, an ortholog of Arabidopsis UFO, suppresses earlier conversion of IM to SM and promotes cell proliferation in the IM (Ikeda et al., 2005, 2007; Ikeda-Kawakatsu et al., 2009). In addition, APO1 regulates floral organ identity and floral determinacy by enhancing expression of the C-function gene OsMADS3 (Ikeda et al., 2005). However, we found that the level of APO2/RFL expression was increased in our osvil2 mutants. The APO2/RFL gene, an ortholog of Arabidopsis LFY, also suppresses the transition from IM to SM. A reduction in its expression decreases the number of panicle branches produced and alters floral organ identity (Rao et al., 2008; Ikeda-Kawakatsu et al., 2012).

Among the four RCN genes that are homologous to Arabidopsis TERMINAL FLOWER 1 (Nakagawa et al., 2002), expression of RCN4 was increased by at least twofold in the mutant spikelets, while that of RCN1, RCN2, and RCN3 was not significantly affected. Furthermore, we were unable to find any significant change in transcriptome levels for SNB and MFS, which function during the transition from SM to FM (Table 1). Expression was slightly elevated for FZP, a gene that inhibits the axillary meristem in spikelets and promotes FM by enhancing the expression of B-function (OsMADS4 and OsMADS16), E-function (OsMADS1, OsMADS7, and OsMADS8), and AGL6-like (OsMADS6 and OsMADS17) MADS-box genes (Komatsu et al., 2003; Bai et al., 2016).

Among the genes that are necessary for the formation of empty glumes (Yoshida et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2015), G1 and OsIG1 were significantly down-regulated in young spikelets from osvil2. Because empty glume development was abnormal and their numbers were fewer in the mutant, reduced gene expression may have been responsible for these defects. Moreover, downregulation of REP1, which is requires for palea development (Yuan et al., 2009), may have been related to the degeneration of palea in osvil2.

Several MADS-box genes that function in floral organ identity were down-regulated in the osvil2 spikelets. Expression of the B-function OsMADS4 and OsMADS16 was affected in the mutant, especially in 2-mm spikelets. The C-function OsMADS3, OsMADS58, and DL were also down-regulated in the mutant spikelets. In addition, expression was significantly reduced for the D-function OsMADS13 and the E-function OsMADS1, OsMADS6, OsMADS7, and OsMADS8. In contrast, expression of A-function genes OsMADS14, OsMADS15, and OsMADS18 was not significantly affected while that of OsMADS5 was increased.

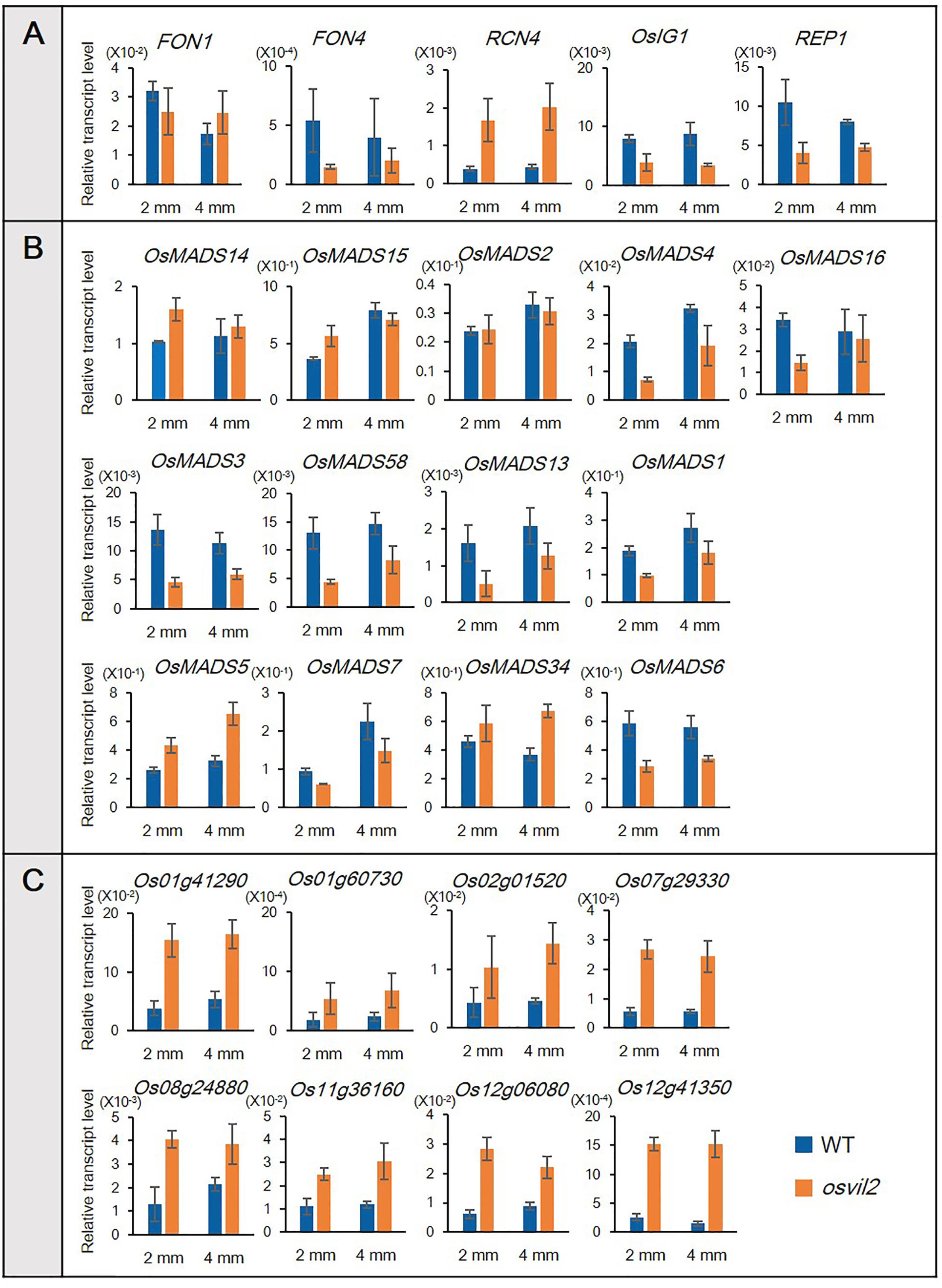

To verify our RNA-sequencing data, we conducted qRT-PCR, focusing on 13 MADS-box genes that control floral organ identity and development (Figure 6). Among them, eight (OsMADS1, OsMADS3, OsMADS4, OsMADS6, OsMADS7, OsMADS13, OsMADS16, and OsMADS58) were down-regulated while the expression of five (OsMADS2, OsMADS5, OsMADS14, OsMADS15, and OsMADS34) was not changed significantly, according to the transcriptome analyses (Figure 6B). In the osvil2 mutants, expression of all eight downregulated genes was significantly reduced, based on the qRT-PCR results. Among the five for which RNA-sequencing analyses showed no significant change, expression was similar between WT and osvil2 for three, while two others, OsMADS5 and OsMADS34, were slightly up-regulated in the mutant panicles.

FIGURE 6. Verification of RNA-sequencing results via qRT-PCR. Transcript levels are relative to Ubi1. (A) qRT-PCR analysis of genes involved in spikelet development. (B) qRT-PCR analysis of MADS-box genes involved in floral organ development. (C) qRT-PCR analysis of upregulated genes previously identified in RNA-sequencing analysis.

We also selected eight genes shown to be up-regulated based on our transcriptome analyses (Figure 6C). The qRT-PCR verification experiments revealed that their expression was much higher in the osvil2 mutants. All of these outcomes demonstrated that the data obtained from RNA-sequencing analyses are reliable.

In this study, we analyzed the abnormal phenotypes of osvil2 and found that they were variable in all organs of the spikelets. Furthermore, expression of essential regulatory genes for spikelet development was significantly altered in the mutant. These results demonstrated how necessary OsVIL2 is for normal organ patterning during spikelet formation because it modulates proper expression of those genes that control organ development and identity in spikelets.

The osvil2 mutant spikelets produced elongated empty glumes that resembled lemma. Homeotic transformation of empty glumes into lemma has also been described for mutants defective in G1, EG1, EG2, OsMADS34, and OsIG1 (Li et al., 2009; Yoshida et al., 2009; Gao et al., 2010; Cai et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2015). As the empty glumes are not found in the spikelets of other grasses, the origin and identity of empty glume are controversial (Yoshida and Nagato, 2011). Elongated empty glume phenotype of osvil2 supports the idea that the empty glumes are degenerated lemma of sterile florets (Arber, 1934). Expression of genes for empty glume identity – G1 and OsIG1 – was substantially lower in the developing panicles of osvil2 than in those of the WT, suggesting that OsVIL2 functions upstream of G1 and OsIG1 to specify sterile lemma identity.

Another phenotype of osvil2 spikelets was the formation of degenerated palea. This defect occurred mostly in the palea body rather than in the marginal region. In addition, the middle portion of the palea primordia often did not grow, thereby splitting the palea. These phenotypes are similar to those reported for mutants defective in REP1, OsMADS15, MFS1, DP1, or OsIG1 (Yuan et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2010; Jin et al., 2011; Ren et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2015). Expression of REP1, DP1, and OsIG1 was reduced in osvil2 mutants, suggesting that those genes are linked with the palea defects. In Arabidopsis, VIL genes function in vernalization and flowering time (Sung and Amasino, 2004; Sung et al., 2006; Greb et al., 2007). Our observation that rice VIL functions in spikelet development indicates a diversified function of the gene family. Because spikelet is a unique structure of grass inflorescence, it will be interesting to study whether function of OsVIL2 is conserved in other grass species.

The most significant phenotype of osvil2 was an increase in numbers for all floral organs. This phenotype was similar to that of mutants defective in FON4, an ortholog of Arabidopsis CLV3 (Chu et al., 2006). There, the number of floral organs in the inner whorls is more highly affected in the spikelets. For fon4 mutants, the carpel number can increase up to 10 whereas that number rose to two in osvil2. Stamen numbers also increase up to 10 in fon4 versus up to eight in osvil2. The homeotic conversion of empty glumes to lemma is common to both fon4 and osvil2 mutants. We noted that expression of FON4 was reduced in the developing osvil2 panicles, suggesting that this gene functions downstream of OsVIL2.

Floral organ identity is regulated by numerous genes, including some MADS-box genes (Zhang and Yuan, 2014). We observed that several MADS-box genes were differentially expressed in osvil2. Alteration in the expression of these floral homeotic genes may have been responsible for the abnormal development of floral organs in the mutant.

This study revealed that OsVIL2 affects variable aspects of spikelet development by controlling various genes important for spikelet development. Because OsVIL2 functions together with PRC2, which suppresses target chromatin, we expected to find that expression of direct targets would be higher in the osvil2 mutants. Instead, transcription levels for most regulatory genes that control organ number or identity were reduced, while expression was slightly increased for RCN4, OsMADS5, and OsMADS34. This implied that they may be direct targets of OsVIL2-PRC2. Although the function of RCN4 remains unknown, overexpression of RCN1 and RCN2 can result in highly branched panicles, suggesting that they also have roles in suppressing floral fate (Nakagawa et al., 2002). In an earlier functional study of OsEMF2b, OsMADS34 was predicted as a direct target gene of OsEMF2b (Conrad et al., 2014). Because OsEMF2b interacts with OsVIL2 (Yang et al., 2013), mutations of OsVIL2 may also influence the MADS-box genes.

GA organized the entire of this research. GA, HY, JY, WL, and DZ designed the research. HY, JY, WL, and DZ performed the experiments and analyzed data. HY and GA wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

This work was supported by the grant from the Cooperative Research Program for Agriculture Science & Technology Development, Rural Development Administration, South Korea (Project no. PJ013210) to GA.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The authors thank Kyungsook An for handling the seed stock, and Priscilla Licht for editing the English language content of the article.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2018.00102/full#supplementary-material

FIGURE S1 | Phenotypes of osvil2-2 spikelets. (A) Abnormal rudimentary glume formation in osvil2-2 spikelet. (B) osvil2-2 spikelet with elongated empty glumes. (C) osvil2-2 spikelet with additional lemma-like organs, indicated by arrows. (D) osvil2-2 spikelet with degenerated palea. (E) Twin-flower phenotype. (F) Additional floral organ formation. (G) Additional lodicule and elongated lodicule formation. (H) Abnormal carpel with increased number of stigmas and undifferentiated cell mass. (I) Lodicule–stamen mosaic organ in osvil2-2. Ca, carpel; EEG, elongated empty glume; Elo, elongated lodicule; L, lemma; Lo, lodicule; P, palea; ucm, undifferentiated cell mass. Scale bars = 1 mm.

FIGURE S2 | Geneontology analysis of differentially expressed genes in osvil2. (A) Enrichment of upregulated genes in 2-mm panicle. (B) Enrichment of downregulated genes in 2-mm panicle. (C) Enrichment of upregulated genes in 4-mm panicle. (D) Enrichment of downregulated genes in 4-mm panicle.

TABLE S1 | Sequences of primers used in this study.

TABLE S2 | Genes up-regulated in 2-mm young panicles of osvil2.

TABLE S3 | Genes down-regulated in 2-mm young panicles of osvil2.

TABLE S4 | Genes up-regulated in 4-mm young panicles of osvil2.

TABLE S5 | Genes down-regulated in 4-mm young panicles of osvil2.

TABLE S6 | Genes up-regulated in both 2- and 4-mm young panicles of osvil2.

TABLE S7 | Genes down-regulated in both 2- and 4-mm young panicles of osvil2.

An, G., Ebert, P. R., Mitra, A., and Ha, S. B. (1989). “Binary vectors,” in The Plant Molecular Biology Manual, eds S. B. Gelvin and R. A. Schilperoort (Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publisher), 1–19.

Arber, A. (1934). The Gramineae: A Study of Cereal, Bamboo, and Grasses. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bai, X., Huang, Y., Mao, D., Wen, M., Zhang, L., and Xing, Y. (2016). Regulatory role of FZP in the determination of panicle branching and spikelet formation in rice. Sci. Rep. 6:19022. doi: 10.1038/srep19022

Bommert, P., Satoh-Nagasawa, N., Jackson, D., and Hirano, H. Y. (2005). Genetics and evolution of inflorescence and flower development in grasses. Plant Cell Physiol. 46, 69–78. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pci504

Cai, Q., Yuan, Z., Chen, M., Yin, C., Luo, Z., Zhao, X., et al. (2014). Jasmonic acid regulates spikelet development in rice. Nat. Commun. 5:3476. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4476

Cao, R., Wang, L., Wang, H., Xia, L., Erdjument-Bromage, H., Tempst, P., et al. (2002). Role of histone H3 lysine 27 methylation in Polycomb-group silencing. Science 298, 1039–1043. doi: 10.1126/science.1076997

Chu, H., Qian, Q., Liang, W., Yin, C., Tan, H., Yao, X., et al. (2006). The FLORAL ORGAN NUMBER4 gene encoding a putative ortholog of Arabidopsis CLAVATA3 regulates apical meristem size in rice. Plant Physiol. 142, 1039–1052. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.086736

Conrad, L. J., Khanday, I., Johnson, C., Guiderdoni, E., An, G., Vijayraghavan, U., et al. (2014). The polycomb group gene EMF2B is essential for maintenance of floral meristem determinacy in rice. Plant J. 80, 883–894. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12688

Czermin, B., Melfi, R., McCabe, D., Seitz, V., Imhof, A., and Pirrotta, V. (2002). Drosophila enhancer of Zeste/ESC complexes have a histone H3 methyltransferase activity that marks chromosomal Polycomb sites. Cell 111, 185–196. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00975-3

Gan, E. S., Huang, J., and Ito, T. (2013). Functional roles of histone modification, chromatin remodeling and microRNAs in Arabidopsis flower development. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 305, 115–161. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-407695-2.00003-2

Gao, X., Liang, W., Yin, C., Ji, S., Wang, H., Su, X., et al. (2010). The SEPALLATA-like gene OsMADS34 is required for rice inflorescence and spikelet development. Plant Physiol. 153, 728–740. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.156711

Goodrich, J., Puangsomlee, P., Martin, M., Long, D., Meyerowitz, E. M., and Coupland, G. (1997). A Polycomb-group gene regulates homeotic gene expression in Arabidopsis. Nature 386, 44–51. doi: 10.1038/386044a0

Greb, T., Mylne, J. S., Crevillen, P., Geraldo, N., An, H., Gendall, A. R., et al. (2007). The PHD finger protein VRN5 functions in the epigenetic silencing of Arabidopsis FLC. Curr. Biol. 17, 73–78. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.11.052

Hennig, L., Taranto, P., Walser, M., Schönrock, N., and Gruissem, W. (2003). Arabidopsis MSI1 is required for epigenetic maintenance of reproductive development. Development 130, 2555–2565. doi: 10.1242/dev.00470

Ikeda, K., Ito, M., Nagasawa, N., Kyozuka, J., and Nagato, Y. (2007). Rice ABERRANT PANICLE ORGANIZATION 1, encoding an F-box protein, regulates meristem fate. Plant J. 51, 1030–1040. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03200.x

Ikeda, K., Nagasawa, N., and Nagato, Y. (2005). ABERRANT PANICLE ORGANIZATION 1 temporally regulates meristem identity in rice. Dev. Biol. 282, 349–360. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.03.016

Ikeda, K., Sunohara, H., and Nagato, Y. (2004). Developmental course of inflorescence and spikelet in rice. Breed. Sci. 54, 147–156. doi: 10.1270/jsbbs.54.147

Ikeda-Kawakatsu, K., Maekawa, M., Izawa, T., Ito, J. I., and Nagato, Y. (2012). ABERRANT PANICLE ORGANIZATION 2/RFL, the rice ortholog of Arabidopsis LEAFY, suppresses the transition from inflorescence meristem to floral meristem through interaction with APO1. Plant J. 69, 168–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04781.x

Ikeda-Kawakatsu, K., Yasuno, N., Oikawa, T., Iida, S., Nagato, Y., Maekawa, M., et al. (2009). Expression level of ABERRANT PANICLE ORGANIZATION1 determines rice inflorescence form through control of cell proliferation in the meristem. Plant Physiol. 150, 736–747. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.136739

Jeon, J. S., Chung, Y. Y., Lee, S., Yi, G. H., Oh, B. G., and An, G. (1999). Isolation and characterization of an anther-specific gene, RA8, from rice (Oryza sativa L.). Plant Mol. Biol. 39, 35–44. doi: 10.1023/A:1006157603096

Jeon, J. S., Jang, S., Lee, S., Nam, J., Kim, C., Lee, S. H., et al. (2000a). leafy hull sterile1 is a homeotic mutation in a rice MADS box gene affecting rice flower development. Plant Cell 12, 871–884. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.6.871

Jeon, J. S., Lee, S., Jung, K. H., Jun, S. H., Jeong, D. H., Lee, J., et al. (2000b). T-DNA insertional mutagenesis for functional genomics in rice. Plant J. 22, 561–570. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00767.x

Jeong, D. H., An, S., Kang, H. G., Moon, S., Han, J. J., Park, S., et al. (2002). T-DNA insertional mutagenesis for activation tagging in rice. Plant Physiol. 130, 1636–1644. doi: 10.1104/pp.014357

Jin, Y., Luo, Q., Tong, H., Wang, A., Cheng, Z., Tang, J., et al. (2011). An AT-hook gene is required for palea formation and floral organ number control in rice. Dev. Biol. 359, 277–288. doi: 10.1016/j.dbio.2011.08.023

Katz, A., Oliva, M., Mosquna, A., Hakim, O., and Ohad, N. (2004). FIE and CURLY LEAF polycomb proteins interact in the regulation of homeobox gene expression during sporophyte development. Plant J. 37, 707–719. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2003.01996.x

Komatsu, M., Chujo, A., Nagato, Y., Shimamoto, K., and Kyozuka, J. (2003). FRIZZY PANICLE is required to prevent the formation of axillary meristems and to establish floral meristem identity in rice spikelets. Development 130, 3841–3850. doi: 10.1242/dev.00564

Lee, D. Y., and An, G. (2012). Two AP2 family genes, SUPERNUMERARY BRACT (SNB) and OsINDETERMINATE SPIKELET 1 (OsIDS1), synergistically control inflorescence architecture and floral meristem establishment in rice. Plant J. 69, 445–461. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04804.x

Lee, D. Y., Lee, J., Moon, S., Park, S. Y., and An, G. (2007). The rice heterochronic gene SUPERNUMERARY BRACT regulates the transition from spikelet meristem to floral meristem. Plant J. 49, 64–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02941.x

Lenhard, M., Bohnert, A., Jürgens, G., and Laux, T. (2001). Termination of stem cell maintenance in Arabidopsis floral meristems by interactions between WUSCHEL and AGAMOUS. Cell 105, 805–814. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00390-7

Li, H., Liang, W., Jia, R., Yin, C., Zong, J., Kong, H., et al. (2010). The AGL6-like gene OsMADS6 regulates floral organ and meristem identities in rice. Cell Res. 20, 299–313. doi: 10.1038/cr.2009.143

Li, H., Xue, D., Gao, Z., Yan, M., Xu, W., Xing, Z., et al. (2009). A putative lipase gene EXTRA GLUME1 regulates both empty-glume fate and spikelet development in rice. Plant J. 57, 593–605. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03710.x

Luo, M., Platten, D., Chaudhury, A., Peacock, W. J., and Dennis, E. S. (2009). Expression, imprinting, and evolution of rice homologs of the polycomb group genes. Mol. Plant 2, 711–723. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssp036

Mayer, K. F., Schoof, H., Haecker, A., Lenhard, M., Jürgens, G., and Laux, T. (1998). Role of WUSCHEL in regulating stem cell fate in the Arabidopsis shoot meristem. Cell 95, 805–815. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81703-1

Moon, S., Jung, K. H., Lee, D. E., Lee, D. Y., Lee, J., An, K., et al. (2006). The rice FON1 gene controls vegetative and reproductive development by regulating shoot apical meristem size. Mol. Cells 21, 147–152.

Moon, Y. H., Chen, L., Pan, R. L., Chang, H. S., Zhu, T., Maffeo, D. M., et al. (2003). EMF genes maintain vegetative development by repressing the flower program in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 15, 681–693. doi: 10.1105/tpc.007831

Mozgova, I., and Hennig, L. (2015). The polycomb group protein regulatory network. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 66, 269–296. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-043014-115627

Mozgova, I., Köhler, C., and Hennig, L. (2015). Keeping the gate closed: functions of the polycomb repressive complex PRC2 in development. Plant J. 83, 121–132. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12828

Müller, J., Hart, C. M., Francis, N. J., Vargas, M. L., Sengupta, A., Wild, B., et al. (2002). Histone methyltransferase activity of a Drosophila Polycomb group repressor complex. Cell 111, 197–208. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00976-5

Nakagawa, M., Shimamoto, K., and Kyozuka, J. (2002). Overexpression of RCN1 and RCN2, rice TERMINAL FLOWER 1/CENTRORADIALIS homologs, confers delay of phase transition and altered panicle morphology in rice. Plant J. 29, 743–750. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2002.01255.x

Nardmann, J., and Werr, W. (2006). The shoot stem cell niche in angiosperms: expression patterns of WUS orthologues in rice and maize imply major modifications in the course of mono- and dicot evolution. Mol. Biol. Evol. 23, 2492–2504. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msl125

Nekrasov, M., Wild, B., and Müller, J. (2005). Nucleosome binding and histone methyltransferase activity of Drosophila PRC2. EMBO Rep. 6, 348–353. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400376

Ohmori, S., Kimizu, M., Sugita, M., Miyao, A., Hirochika, H., Uchida, E., et al. (2009). MOSAIC FLORAL ORGANS1, an AGL6-like MADS box gene, regulates floral organ identity and meristem fate in rice. Plant Cell 21, 3008–3025. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.068742

Prasada, K., Parameswaran, S., and Vijayraghavan, U. (2005). OsMADS1, a rice MADS-box factor, controls differentiation of specific cell types in the lemma and palea and is an early-acting regulator of inner floral organs. Plant J. 43, 915–928. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02504.x

Rao, N. N., Prasad, K., Kumar, P. R., and Vijayraghavan, U. (2008). Distinct regulatory role for RFL, the rice LFY homolog, in determining flowering time and plant architecture. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 3646–3651. doi: 10.1073/pnas.070905910

Ren, D., Li, Y., Zhao, F., Sang, X., Shi, J., Wang, N., et al. (2013). MULTI-FLORET SPIKELET1, which encodes an AP2/ERF protein, determines spikelet meristem fate and sterile lemma identity in rice. Plant Physiol. 162, 872–884. doi: 10.1104/PP.113.216044

Sang, X., Li, Y., Luo, Z., Ren, D., Fang, L., Wang, N., et al. (2012). CHIMERIC FLORAL ORGANS1, encoding a monocot-specific MADS box protein, regulates floral organ identity in rice. Plant Physiol. 160, 788–807. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.200980

Sun, B., Looi, L. S., Guo, S., He, Z., Gan, E. S., Huang, J., et al. (2014). Timing mechanism dependent on cell division is invoked by Polycomb eviction in plant stem cells. Science 343:1248559. doi: 10.1126/science.1248559

Sun, B., Xu, Y., Ng, K. H., and Ito, T. (2009). A timing mechanism for stem cell maintenance and differentiation in the Arabidopsis floral meristem. Genes Dev. 23, 1791–1804. doi: 10.1101/gad.1800409

Sung, S., and Amasino, R. M. (2004). Vernalization in Arabidopsis thaliana is mediated by the PHD finger protein VIN3. Nature 427, 159–164. doi: 10.1038/nature02195

Sung, S., Schmitz, R. J., and Amasino, R. M. (2006). A PHD finger protein involved in both the vernalization and photoperiod pathways in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev. 20, 3244–3248. doi: 10.1101/gad.1493306

Suzaki, T., Sato, M., Ashikari, M., Miyoshi, M., Nagato, Y., and Hirano, H. Y. (2004). The gene FLORAL ORGAN NUMBER1 regulates floral meristem size in rice and encodes a leucine-rich repeat receptor kinase orthologous to Arabidopsis CLAVATA1. Development 131, 5649–5657. doi: 10.1242/dev.01441

Wang, K., Tang, D., Hong, L., Xu, W., Huang, J., Li, M., et al. (2010). DEP and AFO regulate reproductive habit in rice. PLOS Genet. 6:e1000818. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000818

Wei, J., Choi, H., Jin, P., Wu, Y., Yoon, J., Lee, Y. S., et al. (2016). GL2-type homeobox gene Roc4 in rice promotes flowering time preferentially under long days by repressing Ghd7. Plant Sci. 252, 133–143. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2016.7.012

Xie, S., Chen, M., Pei, R., Ouyang, Y., and Yao, J. (2015). OsEMF2b acts as a regulator of flowering transition and floral organ identity by mediating H3K27me3 deposition at OsLFL1 and OsMADS4 in rice. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 33, 121–132. doi: 10.1007/s11105-014-0733-1

Yang, J., Lee, S., Hang, R., Kim, S. R., Lee, Y. S., Cao, X., et al. (2013). OsVIL2 functions with PRC2 to induce flowering by repressing OsLFL1 in rice. Plant J. 73, 566–578. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12057

Yi, J., and An, G. (2013). Utilization of T-DNA tagging lines in rice. J. Plant Biol. 56, 85–90. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12057

Yoon, J., Cho, L. H., Kim, S. L., Choi, H., Koh, H. J., and An, G. (2014). The BEL1-type homeobox gene SH5 induces seed shattering by enhancing abscission-zone development and inhibiting lignin biosynthesis. Plant J. 79, 717–728. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12581

Yoshida, A., Suzaki, T., Tanaka, W., and Hirano, H. Y. (2009). The homeotic gene long sterile lemma (G1) specifies sterile lemma identity in the rice spikelet. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 20103–20108. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907896106

Yoshida, H., and Nagato, Y. (2011). Flower development in rice. J. Exp. Bot. 62, 4719–4730. doi: 10.1093/jxb/err272

Yoshida, N., Yanai, Y., Chen, L., Kato, Y., Hiratsuka, J., Miwa, T., et al. (2001). EMBRYONIC FLOWER2, a novel polycomb group protein homolog, mediates shoot development and flowering in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 13, 2471–2481. doi: 10.1105/tpc.010227

Yuan, Z., Gao, S., Xue, D. W., Luo, D., Li, L. T., Ding, S. Y., et al. (2009). RETARDED PALEA1 controls palea development and floral zygomorphy in rice. Plant Physiol. 149, 235–244. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.128231

Zhang, D., and Yuan, Z. (2014). Molecular control of glass inflorescence development. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. 65, 553–578. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-050213-040104

Zhang, J., Tang, W., Huang, Y., Niu, X., Zhao, Y., Han, Y., et al. (2015). Down-regulation of a LBD-like gene, OsIG1, leads to occurrence of unusual double ovules and developmental abnormalities of various floral organs and megagametophyte in rice. J. Exp. Bot. 66, 99–112. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eru396

Keywords: VIN3-LIKE gene, spikelet development, floral organ number, rice, Polycomb repressive complex 2, chromatin remodeling factor

Citation: Yoon H, Yang J, Liang W, Zhang D and An G (2018) OsVIL2 Regulates Spikelet Development by Controlling Regulatory Genes in Oryza sativa. Front. Plant Sci. 9:102. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.00102

Received: 01 October 2017; Accepted: 18 January 2018;

Published: 06 February 2018.

Edited by:

Stefan de Folter, Centro de Investigación y de Estudios Avanzados del Instituto Politécnico Nacional (CINVESTAV-IPN), MexicoReviewed by:

Xiaoli Jin, Zhejiang University, ChinaCopyright © 2018 Yoon, Yang, Liang, Zhang and An. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Gynheung An, Z2VuZWFuQGtodS5hYy5rcg==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.