- Department of Biophysics, Centre of the Region Haná for Biotechnological and Agricultural Research, Faculty of Science, Palacký University, Olomouc, Czechia

The effect of various abiotic stresses on photosynthetic apparatus is inevitably associated with formation of harmful reactive oxygen species (ROS). In this review, recent progress on ROS production by photosystem II (PSII) as a response to high light and high temperature is overviewed. Under high light, ROS production is unavoidably associated with energy transfer and electron transport in PSII. Singlet oxygen is produced by the energy transfer form triplet chlorophyll to molecular oxygen formed by the intersystem crossing from singlet chlorophyll in the PSII antennae complex or the recombination of the charge separated radical pair in the PSII reaction center. Apart to triplet chlorophyll, triplet carbonyl formed by lipid peroxidation transfers energy to molecular oxygen forming singlet oxygen. On the PSII electron acceptor side, electron leakage to molecular oxygen forms superoxide anion radical which dismutes to hydrogen peroxide which is reduced by the non-heme iron to hydroxyl radical. On the PSII electron donor side, incomplete water oxidation forms hydrogen peroxide which is reduced by manganese to hydroxyl radical. Under high temperature, dark production of singlet oxygen results from lipid peroxidation initiated by lipoxygenase, whereas incomplete water oxidation forms hydrogen peroxide which is reduced by manganese to hydroxyl radical. The understanding of molecular basis for ROS production by PSII provides new insight into how plants survive under adverse environmental conditions.

Introduction

Photosystem II (PSII) is water-plastoquinone oxidoreductase embedded in the thylakoid membrane that catalyzes light-driven H2O oxidation to O2 and plastoquinone (PQ) reduction to plastoquinol (PQH2; Dau et al., 2012; Vinyard et al., 2013; Nelson and Junge, 2015; Suga et al., 2015; Najafpour et al., 2016). In this reaction, primary charge separation between the chlorophyll monomer (ChlD1) and pheophytin (PheoD1) of D1 protein forms 1[ChlD1•+PheoD1•–] radical pair which is fast stabilized by the oxidation of the weakly coupled chlorophyll dimer PD1 and PD2 (P680) forming 1[P680•+PheoD1•–] radical pair (Cardona et al., 2012). 1[P680•+PheoD1•–] radical pair is stabilized by the electron transport from PheoD1 to the tightly bound plastoquinone QA forming QA•– and from the redox active tyrosine residue D1:161Y (YZ) to P680•+ forming YZ•. Electron transport form QA•– to loosely bound plastoquinone QB and the reduction of YZ• by the proton-coupled electron transport from the Mn4O5Ca cluster forms reducing and oxidizing equivalent at QB and Mn4O5Ca cluster, respectively. When two reducing equivalents are formed at QB site, its protonation forms plastoquinol (PQH2) which is liberated to PQ pool via channels (Lambreva et al., 2014). Formation of four oxidizing equivalents in the Mn4O5Ca cluster causes four-electron oxidation of two H2O to O2 which is released via channels into the lumen (Vogt et al., 2015).

Light-driven processes comprising both energy transfer and electron transport are accompanied by formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS). In the energy transfer, singlet oxygen (1O2) is formed by the energy transfer from triplet chlorophyll to O2 (Triantaphylides and Havaux, 2009; Pospíšil, 2012; Fischer et al., 2013). In electron transport, ROS are formed by the consecutive one-electron reduction of O2 and by the concerted two-electron oxidation of H2O on the PSII electron acceptor and donor sides, respectively (Pospíšil, 2009). The one-electron reduction of O2 forms superoxide anion radical (O2•–) which dismutes spontaneously or enzymatically to hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and subsequently is reduced to hydroxyl radical (HO•) via Fenton reaction. The two-electron oxidation of water forms H2O2 which is oxidized and reduced to O2•– and HO•, respectively. Non-enzymatic and enzymatic scavenging systems have been engaged to eliminate ROS and thus control level of ROS formed under various types of abiotic (adverse environmental conditions such as high light, high and low temperatures, UV-radiation, and drought) and biotic (herbivores and pathogens such as viruses, bacteria, and fungi) stresses.

Under moderate stress, when scavenging system maintains ROS level low, ROS serves as signaling molecules which activate an acclimation response and programmed cell death (Apel and Hirt, 2004; Dietz et al., 2016). Several lines of evidence have been provided that ROS play a crucial role in intracellular signaling from the chloroplast to the nucleus under high light (Gollan et al., 2015; Laloi and Havaux, 2015) and high temperature (Sun and Guo, 2016). However, due high reactivity of ROS toward proteins and lipids, ROS diffusion is limited. It seems to be unlikely that ROS might transmit signal from the chloroplast to the nucleus. It is considered that products of protein oxidation and lipid peroxidation might serve as signaling molecules (Fischer et al., 2012). As ROS formed by energy transfer (1O2) and electron transport (H2O2) are produced simultaneously, it seems to be likely that their action in signaling pathways interferes. It was demonstrated that H2O2 antagonizes the 1O2 signaling pathways in the flu Arabidopsis mutant (Laloi et al., 2007).

Under severe stress, when scavenging system is unable to sufficiently eliminate undesirable ROS formation, PSII proteins and lipids might be oxidized by ROS. Several lines of evidence were provided in the last three decades on the oxidative damage of PSII proteins by ROS under high light (Aro et al., 1993) and high temperature (Yamamoto et al., 2008). It is widely accepted that 1O2 is major ROS responsible for oxidative modification of PSII proteins. Contrary, H2O2 has low capability to oxidize PSII protein; however, when free or protein-bound metals are available, HO• formed by Fenton reaction oxidizes nearby proteins. It has to be pointed that experimental evidence on PSII protein oxidation was obtained in vitro and thus it remains to be clarified whether oxidative modification of PSII proteins by ROS occurs in vivo. Apart to involvement of ROS in PSII protein damage, the inhibition of de novo protein synthesis by ROS was proposed under high light (Nishiyama et al., 2006) and high temperature (Allakhverdiev et al., 2008). Whereas PSII protein oxidation is widely described, limited evidence has been provided on lipid peroxidation near PSII. It was shown that 1O2 formed in PSII initiates lipid peroxidation in the thylakoid membrane (Triantaphylides et al., 2008).

In this review, an update on the latest findings on molecular mechanism of ROS formation at high light and high temperature is presented. In spite of the fact that molecular mechanism of ROS formation is substantially different at high light and high temperature, high light regularly combined with high temperature might bring about more serious impact on ROS formation.

High Light

When light energy which is driving force for photosynthetic reactions exceeds the photosynthetic capacity, a light-induced decline in photochemical activity in PSII denoted as photoinhibition occurs. Limitations in the energy transfer and electron transport result in the generation of ROS. Limitation in energy transfer occurs, when the excess energy absorbed by chlorophyll in the PSII antennae complex is not fully utilized in the PSII reaction center by charge separation. Under these conditions, singlet chlorophyll might be converted to deleterious triplet chlorophyll. To prevent formation of triplet chlorophyll, quenching of singlet chlorophyll to heat is maintained directly by xanthophylls or indirectly by the rearrangement of Lhcb protein by PsbS (Ruban et al., 2012). However, when quenching of singlet chlorophyll is not sufficient, singlet chlorophyll is converted to triplet chlorophyll which transfers energy to O2 forming 1O2. Limitation in electron transport on the PSII electron acceptor side is accompanied by full reduction of PQ pool. As the QB site becomes unoccupied by PQ due to the full reduction of PQ pool, forward electron from QA to QB is blocked. Under these conditions, back electron transport from QA•– to Pheo and consequent recombination of Pheo•– with P680•+ forms deleterious triplet chlorophyll which transfer to O2 forming 1O2. Under highly reducing conditions, double reduction and protonation of QA might result in the release of QAH2 from its binding site. To prevent double reduction of QA, electron from QA•– leaks to O2 forming O2•–. Superoxide anion radical is eliminated by its spontaneous and enzymatic dismutation to H2O2. In the interior of the thylakoid membrane, O2•– is eliminated by the intrinsic SOD activity of cyt b559, whereas O2•– which diffuse out the thylakoid membrane is eliminated by FeSOD attached to the stromal side of the thylakoid membrane at the vicinity of PSII. Limitation in electron transport on the PSII electron donor side is associated with incomplete H2O oxidation catalyzed by the Mn4O5Ca cluster. Incomplete H2O oxidation results in the formation of H2O2 which serves as precursor for HO•. Under conditions, when H2O2 is not properly eliminated by catalase, HO• is formed by Fenton reactions catalyzed by iron and manganese on the PSII electron acceptor and donor sides, respectively.

Singlet Oxygen

Singlet oxygen is formed by the triplet-triplet energy transfer from triplet chlorophyll or triple carbonyl to O2. Triplet-triplet energy transfer from triplet chlorophyll to O2 occurs in both the PSII antennae complex and the PSII reaction center. In the PSII antennae complex, triplet chlorophyll is formed by the photosensitization reaction, whereas in PSII reaction center triplet chlorophyll is formed by the charge recombination of triplet radical pair 3[P680•+Pheo•–]. Triplet-triplet energy transfer from triplet carbonyl to O2 proceeds during lipid peroxidation initiated by ROS formed by light. Whereas 1O2 formation by the energy transfer from triplet chlorophyll is well documented and represents the main source of 1O2 at high light, 1O2 formation by the energy transfer from triplet carbonyls is rarely evidenced and has marginal contribution to the overall 1O2 formation.

Triplet Chlorophyll

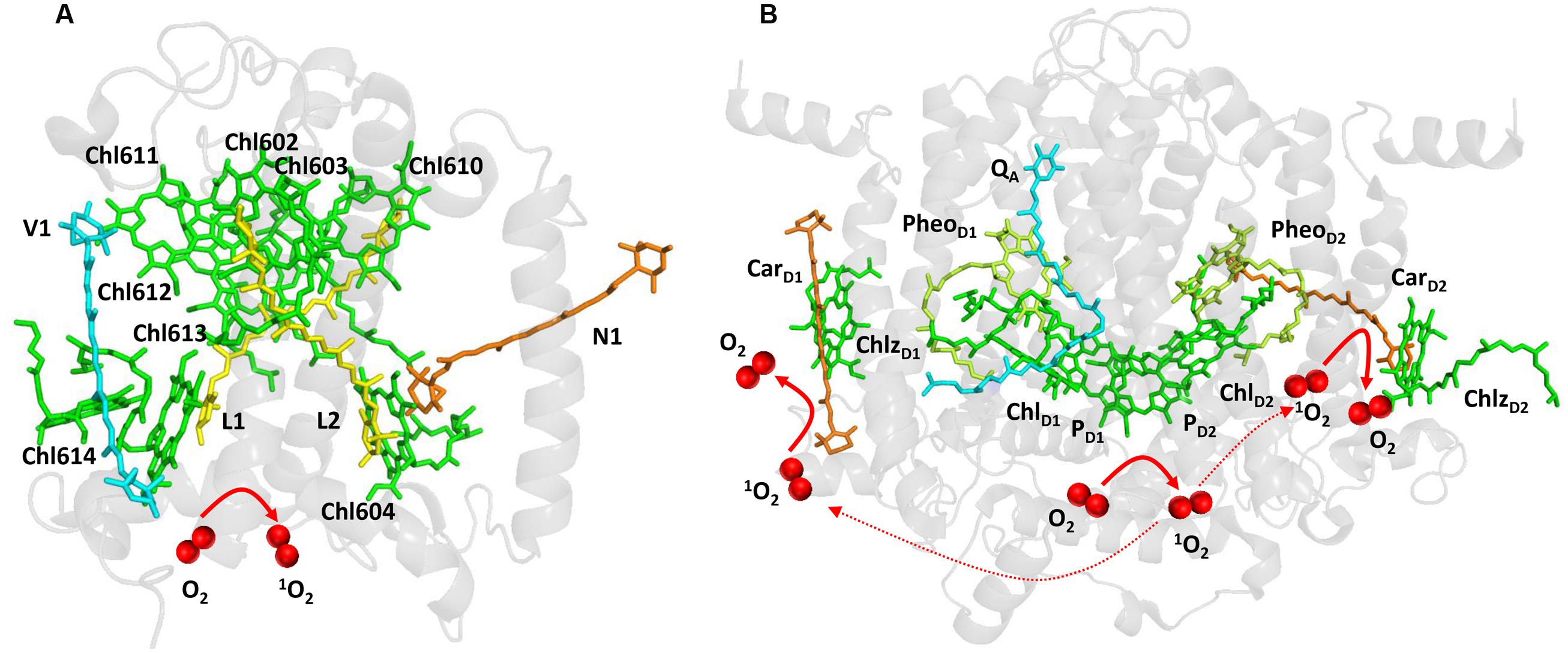

Light energy absorbed by chlorophylls is transferred from the PSII antennae complex toward the PSII reaction center (van Amerongen and Croce, 2013). However, when energy transfer is limited, chlorophylls might serve as photosensitizers which form 1O2 by the energy transfer from their triplet state to O2 (Figure 1A). To prevent this, chlorophylls are coupled with carotenoids which have capability to quench triplet chlorophylls. Carotenoids consist of carotenes (β-carotene) and their oxygenated derivatives xanthophylls (lutein, zeaxanthin; Domonkos et al., 2013). In the PSII antennae complex, lutein and zeaxanthin play a crucial role in triplet chlorophyll quenching (Dall’Osto et al., 2006, 2012). Whereas lutein is permanently coordinated to Lhcb proteins, zeaxanthin is accumulated under high light by the reversible de-epoxidation of violaxanthin and is either free in the thylakoid membrane or bound to Lhcb protein (Havaux and Niyogi, 1999; Pinnola et al., 2013). Four xanthophyll binding sites were documented in the monomeric (Lhcb4-6) and the trimeric (LHCII) antenna proteins of PSII (Liu et al., 2004). Xanthophylls bound in both L1 (lutein) and L2 (lutein in LHCII and lutein or zeaxanthin in monomeric Lhcb4-6 proteins) sites can efficiently quench the neighboring triplet chlorophylls. Lutein in L1 (Lut620) and L2 (Lut621) are coupled with chlorophylls Chl610-Chl614 and Chl602- Chl604, respectively. The quenching of triplet chlorophylls 602 and 603 by lutein in L2 is highly efficient, whereas lutein in L1 site had no effect on quenching of triplet chlorophyll 612 (Ballottari et al., 2013). To maintain effective quenching of triplet chlorophyll by carotenoids, carotenoids has to be properly distanced and oriented from chlorophylls. Triplet-triplet energy transfer from chlorophylls to carotenoids is mediated by Dexter mechanism (Dexter, 1953), which needs overlap between the electron clouds of the donor and acceptor. When distance or orientation of carotenoid and chlorophyll is changed, the capability of carotenoids to quench excitation energy of triplet chlorophylls is diminished (Cupellini et al., 2016). Under such conditions, when O2 is in the proximity of triplet chlorophyll, the transfer of excitation energy from triplet chlorophyll to O2 forms 1O2. Comparison of the monomeric and the trimeric antenna proteins of PSII showed that the monomeric antenna proteins (Lhcb6 > Lhcb5 > Lhcb4) produced more 1O2 as compared to trimeric antenna proteins (LHCII; Ballottari et al., 2013).

FIGURE 1. Light-induced formation of 1O2 in the antennae complex (A) and the reaction center (B) of PSII. The figures were made with Pymol (DeLano, 2002) using the structure for LHCII from Spinacia oleracea (PDB ID: 1rwt; Liu et al., 2004) and PSII from Spinacia oleracea (PDB ID: 3JCU; Wei et al., 2016).

When electron transport on the PSII electron acceptor side is limited due to the slow electron transport to the QA and QB, several types of charge recombination of [P680•+ QA•–] and 1[P680•+PheoD1•–] radical pairs occur. Whereas [P680•+ QA•–] radical pair recombines solely to the ground state P680, primary radical pair 1[P680•+PheoD1•–] formed by the reverse electron transport from QA•– to PheoD1 either recombines to the ground state P680 or converts to the triplet radical pair 3[P680•+PheoD1•–] by change in the spin orientation. Recombination of triplet radical pair 3[P680•+PheoD1•–] forms triplet chlorophyll 3P680∗ delocalized on the weakly coupled chlorophyll dimer PD1 and PD2 (Fischer et al., 2013; Telfer, 2014). Evidence has been provided that triplet state is localized on the ChlD1 at low temperature (Noguchi et al., 2001). The formation of 3ChlD1 was proposed to occur either directly by the charge recombination of the triplet radical pair 3[P680•+PheoD1•–] or by the triplet energy transfer from 3P680∗ to ChlD1. As two β-carotenes (CarD1 and CarD2) are distanced from chlorophyll dimer PD1 and PD2, β-carotenes are not able to quench triplet chlorophyll 3P680∗ (Figure 1B).

Triplet Carbonyl

Lipid peroxidation initiated by radical ROS (O2•–, HO•) forms the primary and the secondary lipid peroxidation products. The primary lipid peroxidation product are lipid hydroperoxides (lipid hydroperoxy fatty acids, LOOH) which decompose to the secondary lipid peroxidation products lipid hydroxides (hydroxy fatty acids, LOH), reactive carbonyl species (RCS), and electronically excited species. Hydrogen abstraction from polyunsaturated fatty acid by HO• forms lipid alkyl radical (L•) which interacts with O2 forming lipid peroxyl radical (LOO•). Lipid peroxyl radical abstracts hydrogen from the adjacent polyunsaturated fatty acid forming LOOH. Lipid hydroperoxide is stable; however, under oxidizing or reducing condition it is oxidized or reduced to LOO• or alkoxyl radical (LO•). Cyclization or recombination of LOO• forms high energy intermediates, dioxetane, or tetroxide. High energy intermediates are highly unstable and decomposite to triplet excited carbonyls (3L∗) which might transfer triplet energy to O2 forming 1O2. Alternatively, tetroxide might directly decompose to 1O2 via the Russell mechanism. Evidence has been provided that 1O2 is formed through lipid peroxidation under light stress in spinach PSII membranes deprived by the Mn4O5Ca cluster (Yadav and Pospíšil, 2012a). The authors demonstrated that the oxidation of lipids by highly oxidizing P680•+ and TyrZ• caused 1O2 formation via the Russell mechanism. It has to be noted that amount of 1O2 formed by the triplet-triplet energy transfer from triplet chlorophyll is considerably higher than from triplet carbonyl.

Superoxide Anion Radical

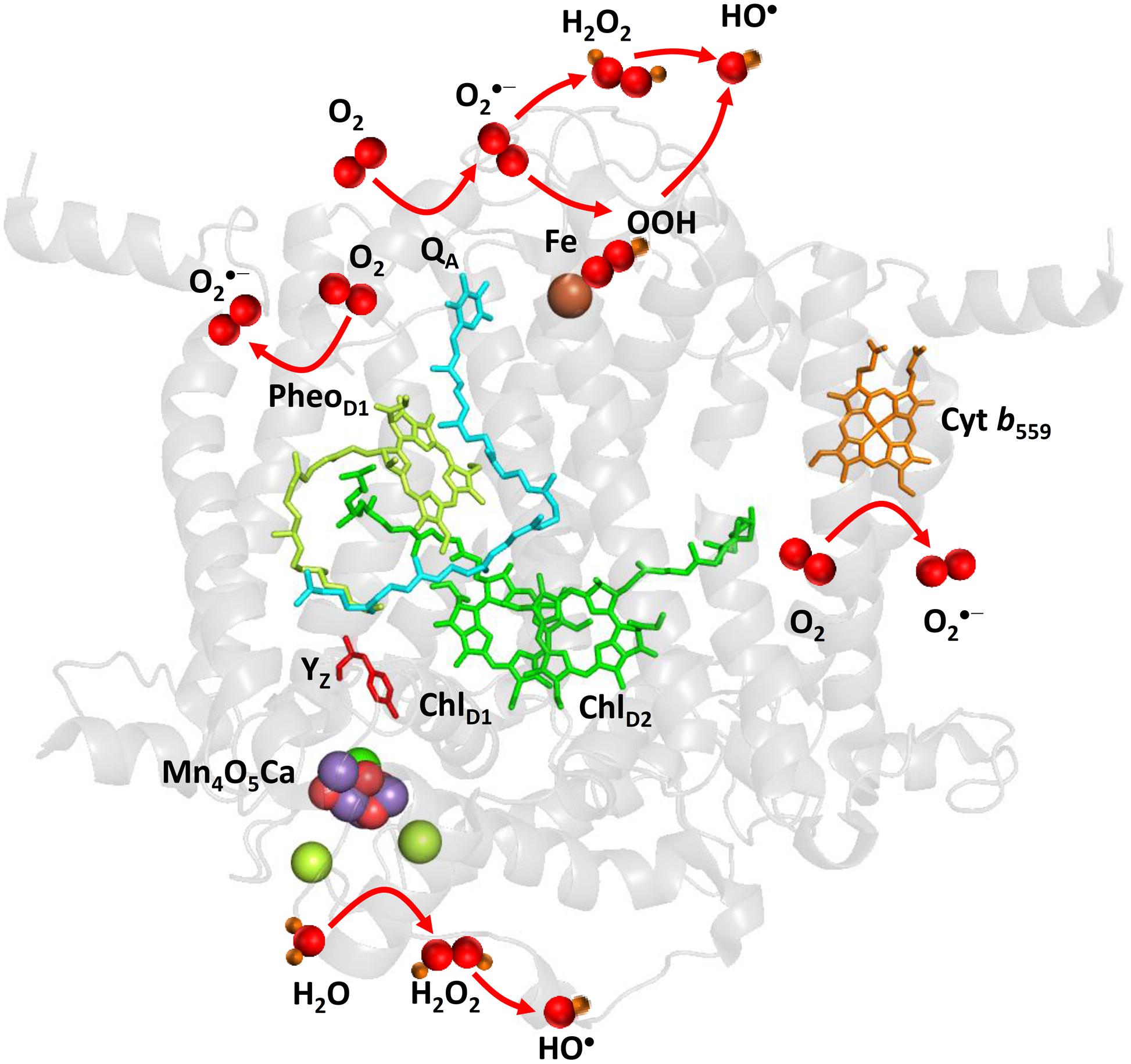

Superoxide anion radical is formed by the one-electron reduction of O2 on the PSII electron acceptor side (Figure 2). Pheophytin (PheoD1•–), tightly bound plastosemiquinone (QA•–), loosely bound plastosemiquinones (QB•– or QC•–), free PQ (PQ•–), and ferrous iron of LP form of cyt b559 were proposed to serve as electron donors to O2 (Ananyev et al., 1994; Cleland and Grace, 1999; Pospíšil et al., 2004, 2006; Yadav et al., 2014). As PheoD1•– has highly negative redox potential, the reduction of O2 by PheoD1•– is thermodynamically feasible; however, its short lifetime makes the diffusion limited reduction of O2 less reasonable. Contrary, plastosemiquinones (QA•–, QB•–) does not fulfill thermodynamic criteria due to their more positive redox potential, whereas they accomplish the kinetic criteria due their long lifetime. However, due to the different concentration of O2 and O2•–, the standard redox potential of O2/O2•– redox couple is shifted according Nernst equation to more positive and thus the reduction of O2 by plastosemiquinones becomes feasible (Pospíšil, 2009). The observation that exposure of isolated D1/D2/cyt b559 complexes which lacks QA to high light causes a significant rate of cytochrome (III) reduction revealed that PheoD1•– has capability to reduces O2. The detection of O2•– in isolated thylakoids by a voltammetric method showed O2•– production by the tightly bound plastosemiquinone QA•– (Cleland and Grace, 1999). Experimental evidence has been recently provided on the reduction of O2 by the loosely bound plastosemiquinones (Yadav et al., 2014). The authors demonstrated that plastosemiquinone is formed by the one-electron reduction of plastoquinone at the QB site and the one-electron oxidation of plastoquinol by cyt b559 at the QC site. Apart to cofactors involved in the linear transport, the ferrous heme iron of LP form of cyt b559 was shown to reduce O2 forming O2•– (Pospíšil et al., 2006).

FIGURE 2. Light-induced formation of O2•-, H2O2, and HO• by PSII. The figure was made with Pymol (DeLano, 2002) using the structure for PSII from Spinacia oleracea (PDB ID: 3JCU; Wei et al., 2016). Loosely bound plastoquinones (QB and QC) were not resolved.

It has been demonstrated that PsbS knock-out rice mutants produced more O2•– compared to WT under high light (Zulfugarov et al., 2014). The authors proposed that the lack of PsbS may cause shift in the midpoint redox potential of QA/QA•– redox couple to more negative value and thus enhance O2•– production by QA•–. The D1 protein phosphorylation which is associated with the migration of damaged PSII complexes from the grana to the stroma lamellae during D1 protein repair cycle was shown to decrease O2•– production (Chen et al., 2012). The author proposed that the D1 protein phosphorylation causes conformation change of D1 protein and thus modifies the binding of loosely bound plastosemiquinone to QB site. Consequently, the alternation of QB site brings about the decrease in O2•– formed by the loosely bound plastosemiquinone QB•–. In agreement with this proposal, it has been recently demonstrated that O2•– production is enhanced in STN8 kinase knock-out rice mutants under high light (Poudyal et al., 2016). It has been proposed that enhancement in O2•– production is due to the absence of conformational changes caused by STN8 kinase-induced phosphorylation. Using PsbY knock-out Arabidopsis plants, it has been shown that redox potential property of cyt b559 is controlled by PsbY protein (von Sydow et al., 2016). It has to be explored whether PsbY protein controls O2•– production.

Hydrogen Peroxide

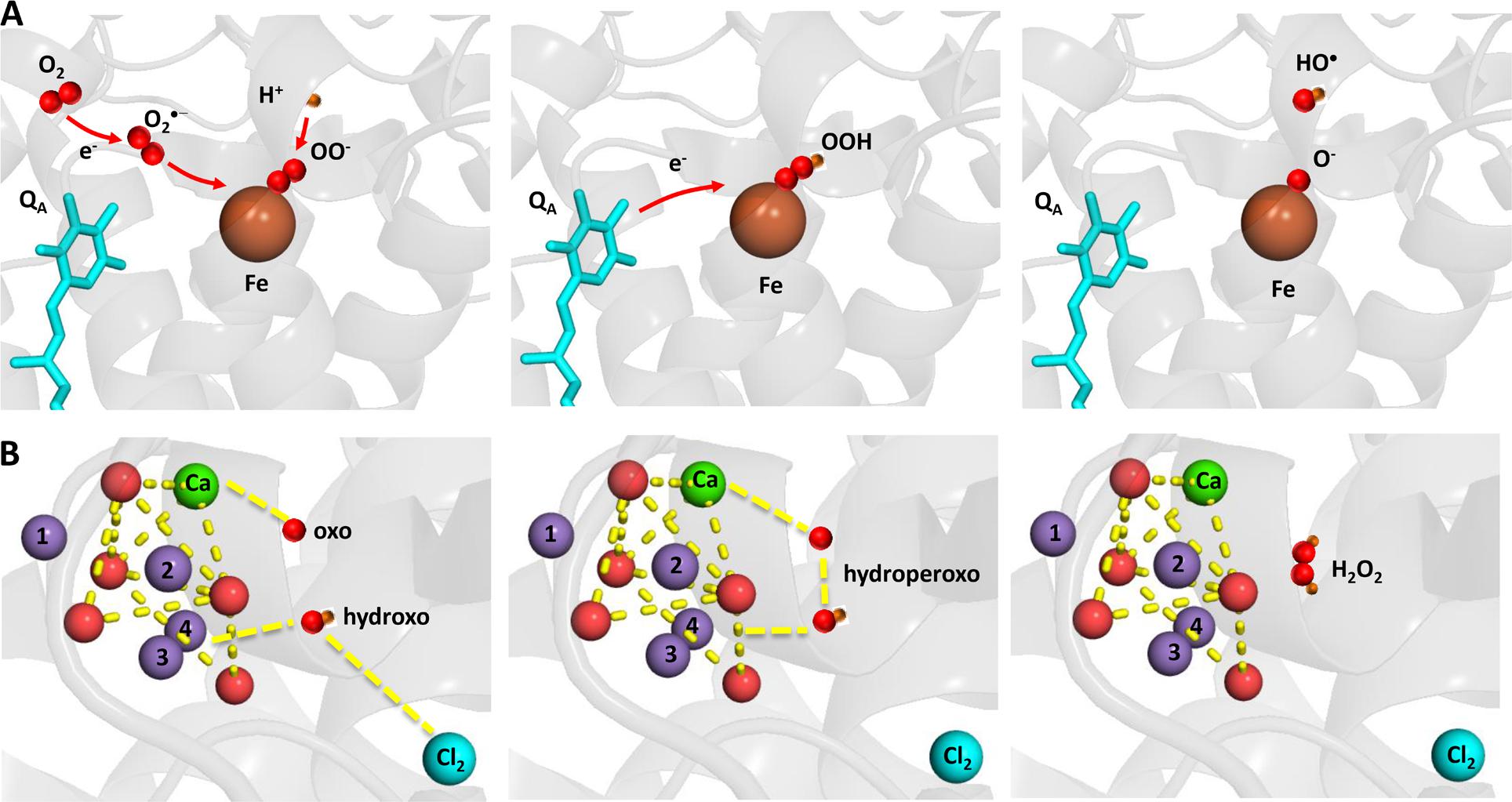

Hydrogen peroxide is formed by the one-electron reduction of O2•– and the two-electron oxidation of H2O on the PSII electron acceptor and donor sides, respectively (Figure 2). Hydrogen peroxide formation by the one-electron reduction of O2•– occurs as dismutation or is maintained by plastosemiquinone. In the dismutation, two O2•– are simultaneously reduced and oxidized forming H2O2 and O2, respectively. In the spontaneous dismutation, the interaction of two O2•– is restricted due to repulsion of the negative charge on the molecule, whereas the interaction of the protonated form of superoxide, hydroperoxyl radical (HO2•), either with O2•– or HO2• is feasible. Spontaneous dismutation has been recently monitored by real-time detection of H2O2 in PSII membrane under high light using highly sensitive and selective osmium-horseradish modified electrode (Prasad et al., 2015). In the enzymatic dismutation, reduction and oxidation of O2•– is associated with the redox change of the redox active metal center which serves as a superoxide oxidase (SOO) and superoxide reductase (SOR), respectively. It was demonstrated that the interaction of O2•– with the non-heme iron results in the oxidation of the ferrous iron and the formation of ferric-peroxo species which is protonated to ferric-hydroperoxo species (bound peroxide; Pospíšil et al., 2004) (Figure 3A). Evidence has been provided that the ferric and ferrous heme irons of cyt b559 exhibit the SOO and the SOR activities, respectively (Tiwari and Pospíšil, 2009; Pospíšil, 2011). Apart to dismutation, free PQ•– in PQ pool was proposed to participate in H2O2 formation. Hydrogen peroxide was shown to be formed by reduction of O2•– by free PQ•– (Borisova-Mubarakshina et al., 2015). The authors showed that H2O2 formed in PQ pool regulates the size of PSII antenna complex at high light. Furthermore, evidence has been provided that H2O2 might be formed by reduction 1O2 of by PQH2 (Khorobrykh et al., 2015). It was demonstrated that 1O2 generated by photosensitizer Rose Bengal interacts with PQH2 forming H2O2. The authors proposed that H2O2 formed by reduction of 1O2 by PQH2 in the thylakoid membrane might cause dimerization of the protein kinase STN7 and thus activates the enzyme.

FIGURE 3. Light-induced formation of bound peroxide and HO• on the PSII electron acceptor (A) donor (B) sides. The figure was made with Pymol (DeLano, 2002) using the structure for PSII from Spinacia oleracea (PDB ID: 3JCU; Wei et al., 2016).

Hydrogen peroxide formation by the two-electron oxidation of H2O is maintained by the Mn4O5Ca cluster when the complete four-electron oxidation of H2O to O2 is limited. Whereas all four manganese are redox active in four-electron oxidation of H2O to O2, the incomplete oxidation of H2O to H2O2 involves two redox active manganese. The two-electron oxidation of H2O has been proposed to involve the transition from either S2 to S0 state or S1 to S-1 state. Evidence has been provided that release of chloride from its binding site near to the Mn4O5Ca cluster enhanced H2O2 formation (Bradley et al., 1991; Fine and Frasch, 1992; Arato et al., 2004). A nucleophilic attack of hydroxo group on oxo group was proposed as an attractive model for formation of hydroperoxo species. It is proposed that nucleophilic attack of hydroxo group coordinated to Mn(4) and Cl(2) and oxo group coordinated to Ca forms hydroperoxo intermediate (Figure 3B). The hydroxo group is formed by deprotonation of the H2O substrate coordinated to to Mn(4) and Cl(2), whereas the oxo group is formed by double deprotonation of H2O substrate coordinated to Ca. A nucleophilic attack of manganese-coordinated hydroxo group on the calcium-coordinated electrophilic oxo group forms a peroxide intermediate that substitutes Cl(2) in coordination to Mn(4). Chloride controls accessibility of H2O substrate to Mn(4) and the nucleophilicity of hydroxo group and thus interaction of hydroxo and oxo groups. Water substrate, which serves as a precursor for the hydroxo group, enters into the catalytic site, when the Cl(2) binding site becomes opened to the solvent H2O due to its release.

Hydroxyl Radical

Hydroxyl radical is formed by the one-electron reduction of H2O2 formed on the both PSII electron acceptor and donor sides (Figure 2). Hydroxyl radical formation by the one-electron reduction of free H2O2 and bound peroxide on the PSII electron acceptor side was shown to be maintained by free iron and the non-heme iron, respectively (Pospíšil et al., 2004). The authors demonstrated that the reduction of bound peroxide (ferric iron-hydroperoxo intermediate) formed by the interaction of O2•– with the ferrous non-heme iron forms HO• via ferric iron-oxo intermediate (Figure 3A).

Hydroxyl radical formation by the one-electron reduction of H2O2 on the PSII electron donor side is likely to be maintained by manganese. From thermodynamic point of view, the reduction of H2O2 by manganese is not feasible. It was proposed that the reduction of H2O2 by manganese becomes thermodynamically more favorable by (1) the coordination of manganese to the protein due to the decrease in the redox potential of manganese and (2) the pH decrease in the lumen due to the increase in the standard redox potential of H2O2/HO• redox couple (Pospíšil, 2012). It was demonstrated that PSII membranes depleted by chloride shows higher HO• formation compared to control PSII membranes (Arato et al., 2004). Based on the observation that HO• formation was not completely suppressed by exogenous SOD, the authors proposed that HO• is formed by reduction of H2O2 produced by the incomplete water oxidation on the PSII electron donor side.

High Temperature

When PSII is exposed to high temperature, decline in the PSII activity denoted as heat inactivation occurs (Mathur et al., 2014). Heat inactivation occurs on the both PSII electron acceptor and donor sides. On the PSII electron donor side, heat inactivation is associated with the inhibition of water oxidation accompanied with release of PsbO, PsbP, and PsbQ proteins, calcium, chloride, and manganese from their binding sites (Coleman et al., 1988; Enami et al., 1994; Pospíšil et al., 2003; Barra et al., 2005). On the PSII electron acceptor side, heat inactivation is linked to the inhibition of electron transport from QA to QB (Pospíšil and Tyystjarvi, 1999). The authors demonstrated that increase in the midpoint redox potential of QA/QA•– redox couple is responsible for the inhibition of QA to QB electron transport. Contrary to high light, ROS formation at high temperature is not driven by energy absorbed by chlorophylls; however, it is associated with heat-induced structural and functional changes in the thylakoid membrane. On the PSII electron acceptor side, 1O2 is formed decomposition of high energy intermediates formed by lipid peroxidation. On the PSII electron donor side, incomplete H2O oxidation forms H2O2 which is reduced by manganese to HO• via Fenton reaction.

Singlet Oxygen

Singlet oxygen is formed by the triplet-triplet energy transfer from 3L∗ to O2 produced by the decomposition of high energy intermediates, dioxetane, or tetroxide, formed during lipid peroxidation (Havaux et al., 2006; Pospíšil and Prasad, 2014). The observation that elimination of HO• formation by mannitol did not suppress 1O2 formation revealed that lipid peroxidation is unlikely initiated by HO• (Pospíšil et al., 2007). More recently, it has been demonstrated that inhibition of lipoxygenase by catechol and caffeic acid in Chlamydomonas cells prevented 1O2 formation (Prasad et al., 2016). Singlet oxygen was proposed to be generated at the lipid phase near the QB site (Yamashita et al., 2008). It was pointed that PQH2 formed by reduction of PQ by stromal reducing compound might cause ROS production which can damage D1 protein (Marutani et al., 2012).

Hydrogen Peroxide

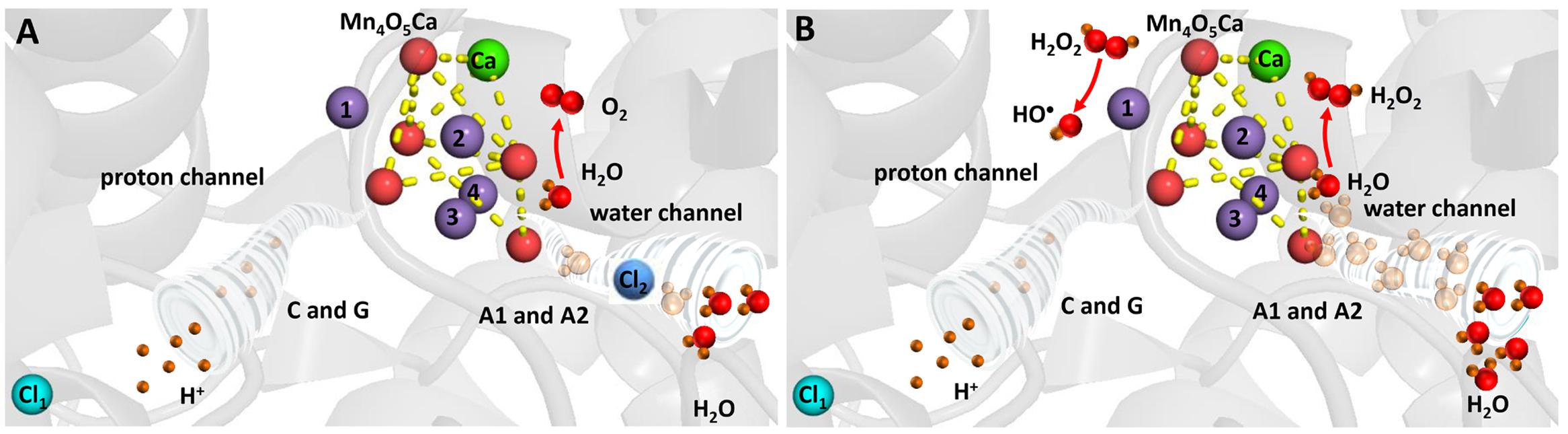

Hydrogen peroxide is formed by the two-electron oxidation of H2O on the PSII electron donor side (Figure 4). It was proposed that the release of extrinsic proteins (PsbO, PsbP, and PsbQ) leads to the inadequate accessibility of water to the Mn4O5Ca cluster and consequently to the formation of H2O2 (Thompson et al., 1989). Indeed, it was demonstrated using the amplex red fluorescent assay that exposure of PSII membranes to high temperature (40°C) results in H2O2 formation (Yadav and Pospíšil, 2012b). The authors demonstrated that the binding of acetate to the Mn4O5Ca cluster in the competition with chloride and blockage of water channel prevented H2O2 formation. Based on these observations, it was suggested that the release of chloride from its binding site near to the Mn4O5Ca cluster leads to uncontrolled accessibility of H2O to the Mn4O5Ca cluster. To maintain controlled four-electron oxidation of H2O to O2, the accessibility of H2O to the Mn4O5Ca cluster has to be regulated. Chloride coordinated to amino acids nearby the Mn4O5Ca cluster controls the accessibility of H2O to the metal center und thus maintain proper four-electron oxidation of H2O to O2. However, when chloride is released from its binding site, the delivery of H2O to the Mn4O5Ca cluster is unrestricted and incomplete oxidation of O2 to H2O2 occurs. Crystal structure of PSII from cyanobacteria Thermosynechococcus vulcanus reveals that two chlorides are located at distances of 6.67 and 7.40 Å from the Mn4O5Ca cluster (Umena et al., 2011). To avoid oxidation of nearby amino acid, diffusion of H2O2 into the lumen has to be restricted to the channels. As H2O2 is larger polar molecule similar to H2O, it seems to be likely that H2O2 diffuse into the lumen via water channels. However, when H2O2 leaks from the water channels, it might interact with manganese and formed HO•.

FIGURE 4. Heat-induced formation of H2O2 and HO• on the PSII electron donor side. (A) Chloride controls accessibility of H2O to the Mn4O5Ca cluster and maintains complete oxidation of H2O to O2. (B) Removal of chloride results in uncontrolled accessibility of H2O to the Mn4O5Ca cluster and incomplete oxidation of H2O to H2O2. The figure was made with Pymol (DeLano, 2002) using the structure for PSII from Spinacia oleracea (PDB ID: 3JCU; Wei et al., 2016).

Hydroxyl Radical

Hydroxyl radical is formed by the one-electron reduction of H2O2 formed on the PSII electron donor side (Figure 4). It was demonstrated by the EPR spin trapping spectroscopy that the exposure of PSII membranes to high temperature results in HO• formation (Pospíšil et al., 2007). The authors showed that HO• production is completely suppressed by exogenous catalase and metal chelator desferal revealing that HO• is formed via the metal-catalyzed Fenton reaction. Furthermore, the observation that the addition of exogenous calcium and chloride prevented HO• formation reveals that HO• is produced by the Mn4O5Ca cluster. This proposal was confirmed by the observation that no HO• formation was observed in PSII membranes deprived by the Mn4O5Ca cluster (Yamashita et al., 2008). As the replacement of chloride by acetate at its binding site near to the Mn4O5Ca cluster and the blockage of water channel prevented HO• formation in a similar manner as H2O2 formation, it was assumed that chloride plays a crucial role in HO• formation (Yadav and Pospíšil, 2012b). The authors proposed that H2O2 formed by the incomplete H2O oxidation is reduced to HO• via the Fenton reaction mediated by free manganese released from the Mn4O5Ca cluster. The release of manganese from its binding site at high temperature was reported using atomic absorption (Nash et al., 1985) and EPR (Coleman et al., 1988; Pospíšil et al., 2003) spectroscopy. Detailed study using X-ray absorption spectroscopy showed that decomposition of the Mn4O5Ca cluster occurs in two steps (Pospíšil et al., 2003). In the first step, two manganese are released from their binding sites into the lumen remaining two manganese connected by a di-μ-oxo bridge, whereas in the second phase the remaining two manganese are liberated form PSII.

Physiological Relevance of ROS Formation

Role of ROS in Retrograde Signaling

Both 1O2 and H2O2 formed in the thylakoid membrane were proposed to be involved in retrograde signaling (Dietz et al., 2016). Role of 1O2 in acclimation and programmed cell death was demonstrated in green algae (Erickson et al., 2015) and higher plants (Triantaphylides and Havaux, 2009; Laloi and Havaux, 2015). In higher plants, fluorescent (flu) and chlorina 1 (ch1) Arabidopsis mutants were advantageously used due to their high capability to form 1O2. It was proposed that the 1O2 level determines whether acclimation response or programmed cell death is triggered (Laloi and Havaux, 2015).

At low 1O2 level, acclimation response is mediated by β-cyclocitral formed by oxidation of β-carotene (Ramel et al., 2013a; Havaux, 2014). It was demonstrated that exposure of WT Arabidopsis plants to β-cyclocitral caused expression of 1O2 related gene (Ramel et al., 2012). In agreement with this finding, it was shown that concentration of β-cyclocitral is enhanced in ch1 Arabidopsis plants under acclimation (Ramel et al., 2013b). Further, evidence was provided on the role of jasmonic acid in acclimation response. It was demonstrated that jasmonate-deficient Arabidopsis mutant (delayed-dehiscence 2) was more resistant to light and jasmonate biosynthesis was pronouncedly lowered under acclimation (Ramel et al., 2013b). Based on these observations, the authors proposed that downregulation of jasmonate biosynthesis plays a crucial role in the triggering of acclimation response (Ramel et al., 2013c).

At high 1O2 level, programmed cell death is dependent on the plastid proteins EXECUTER1 (EX1) and EXECUTER2 (EX2; Lee et al., 2007) and OXIDATIVE SIGNAL INDUCIBLE1 (OXI1) encoding an AGC kinase (Shumbe et al., 2016). Several lines of evidence on the involvement of EX1 and EX2 in programmed cell death were provided using flu Arabidopsis mutant (Lee et al., 2007). In this mutant, 1O2 is formed by triplet-triplet energy transfer from the triplet chlorophyll precursor protochlorophyllide to O2 (op den Camp et al., 2003). Even if EX1 and EX2 are located in chloroplast, it was proposed that jasmonic acid formed by 1O2-initiated lipid peroxidation mediates genetically controlled programmed cell death response via these two plastid proteins (Przybyla et al., 2008). The initiation of 1O2 signaling has been recently demonstrated close to EX1 in the grana margins nearby the site of chlorophyll synthesis and 1O2 formation (Wang et al., 2016). As 1O2 signaling depends on the FstH protease, the authors proposed that 1O2 signaling is linked to D1 repair cycle. Apart to EX1 and EX2, it has been shown recently that OXI1 kinase is involved in 1O2 signaling in ch1 Arabidopsis mutant (Shumbe et al., 2016). In this mutant, 1O2 is formed by triplet-triplet energy transfer from the triplet chlorophyll formed in PSII to O2 (Krieger-Liszkay, 2005). As OXI1 kinase is localized at the cytosol at the cell periphery or in the nucleus, it seems to be likely that oxylipins mediate signal transduction from chloroplast to cytosol (Shumbe et al., 2016).

Hydrogen peroxide formed under high light was demonstrated to play a crucial role in signaling associated with acclimation and programmed cell death (Foyer and Noctor, 2009; Karpinski et al., 2013; Gollan et al., 2015). It is well established that H2O2 regulates expression of genes by the activation of protein kinase signaling pathways. It was proposed that precursor of jasmonic acid, 12-oxo phytodienoic acid (OPDA), mediates signal transduction from chloroplast to cytosol (Tikkanen et al., 2014). It has been recently demonstrated that H2O2 formed in PQ pool triggers signal transduction from the chloroplast to the nucleus via protein kinase signaling pathways leading to the regulation of the PSII antenna size during the acclimation response (Borisova-Mubarakshina et al., 2015).

Our knowledge on the involvement of ROS in retrograde signaling at high temperature is highly limited. While the physiological relevance of light-induced 1O2 to acclimation and programmed cell death is described to some extent, no evidence was provided on the role of 1O2 formed under high temperature to plant stress response. However, it seems to be likely that 1O2 might oxidize lipid, protein or pigment forming specific oxidation products and thus initiates signal transduction from the chloroplast to the nucleus in the signaling cascade pathway. Contrary to 1O2, H2O2 was shown to be an important component in heat stress-activated gene expression. Hydrogen peroxide was demonstrated to be involved in the synthesis of heat shock proteins (Volkov et al., 2006). More experimental data are required to pronouncedly progress our understanding of multiple signaling pathways involved the in response to heat stress.

Role of ROS in Oxidative Damage

At high light, proteins and lipids might be oxidized by ROS formed in PSII. PSII proteins were evidenced to be oxidatively modified in the following order D1 > D2 > Cyt b559 > CP43 > CP47 > Mn4O5Ca cluster (Komenda et al., 2006). Amino acid oxidation at the lumen exposed AB-loop of D1 protein forms 24 kDa C-terminal and 9 kDa N-terminal fragments, whereas amino acid oxidation in the stromally exposed D-de loop of the D1 protein form 23-kDa N-terminal and 9-kDa C-terminal fragments (Edelman and Mattoo, 2008). Identification of naturally oxidized amino acid in D1 protein using mass spectrometry was shown nearby to the site of ROS production (Sharma et al., 1997; Frankel et al., 2012, 2013). Whereas D1 protein oxidation was pronouncedly studied in vitro, limited evidence was provided on D1 protein oxidation in vivo (Shipton and Barber, 1994; Lupinkova and Komenda, 2004). Regardless of a broad range of evidence on PSII protein oxidation obtained in vitro, the plausibility of these processes in vivo has to be clarify. An efficient repair cycle for D1 protein, which includes proteolytic degradation of damaged D1 protein and its replacement with a newly synthetized D1 copy is essential for maintaining the viability of PSII (Komenda et al., 2012; Mulo et al., 2012; Jarvi et al., 2015). Apart to involvement of ROS in PSII protein damage under high light, ROS were shown to suppress the synthesis de novo of proteins with the elongation step of translation as primary target (Nishiyama et al., 2006). However, considering the limited ROS diffusion, it seems to be more likely that ROS produced in the stroma might oxidize the translational elongation factors involved in D1 repair cycle. Unbound chlorophylls released to the stroma from their binding sites during PSII protein damage or chlorophyll precursors during chlorophyll synthesis are likely candidates for 1O2 formation due to the lack of effective quenching of triplet excitation energy by carotenoids. To avoid 1O2 formation, unbound chlorophylls might be temporarily coordinated to early light-induced proteins (ELIPs). In agreement with this proposal, it was demonstrated that small CAB-like proteins prevent 1O2 formation during PSII damage, most probably by the binding of unbound chlorophylls released from the damaged PSII complexes (Sinha et al., 2012). Lipids associated with membrane proteins were shown to be oxidized by ROS. The initiation of lipid peroxidation by 1O2 comprises the insertion of 1O2 to double bond of polyunsaturated fatty acid, whereas HO• initiates lipid peroxidation by hydrogen abstraction from polyunsaturated fatty acid. It has been demonstrated that primary (LOOH) and secondary (LOH, RCS, and electronically excited species) lipid peroxidation products are formed at high light. Formation of hydroxy fatty acid was demonstrated in Arabidopsis plants (Triantaphylides et al., 2008). The authors showed that oxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acid by 1O2 leads to formation of LOOH which further forms LOH isomers (10-HOTE and 15-HOTE).

At high temperature, limited evidence was provided on the oxidation of proteins and lipids by ROS. It was demonstrated that exposure of thylakoid membranes to high temperature caused cleavage of D1 protein forming 9 kDa C-terminal and 23 kDa N-terminal fragments (Yoshioka et al., 2006). The authors demonstrated that FtsH protease is involved in the cleavage of the D1 protein at high temperature. Furthermore, it was reported that 1O2 formed at QB site by the recombination of LOO• formed by the lipid peroxidation caused the D1 protein degradation by the interaction with D-de loop of the D1 protein in a similar manner as under high light (Yamashita et al., 2008). As experimental evidence for oxidative damage of PSII protein by endogenous ROS was obtained predominantly in vitro, it is unclear whether the PSII protein oxidation at high temperature occurs in vivo. Apart to involvement of ROS in PSII protein oxidation, the inhibition of de novo protein synthesis by ROS was proposed at high temperature (Allakhverdiev et al., 2008). Lipid peroxidation is associated with formation of RCS. It was demonstrated that malondialdehyde is formed in Arabidopsis plants exposed to heat stress (Yamauchi et al., 2008).

Conclusion and Perspectives

Under environmental conditions, abiotic stresses adversely affect plant growth and survival. The impact of high light on the photosynthetic apparatus is considered to be of particular significance as light reactions of photosynthesis are inhibited prior to other cell functions are impaired. However, under environmental conditions, plants are exposed to combination of multiple stresses. High light stress is often associated with high temperature causing global warming which is one of the most important characteristics of accelerated climatic changes. Extensive research over the last 10 years focused on the structural and functional changes of the photosynthetic complexes in response to high light, high temperature or their combination. The exploration of molecular mechanism of ROS production by PSII helps to understand the adaptive processes by which plants cope with high light and high temperature stresses.

Author Contributions

The PP wrote and approved manuscript for publication.

Funding

This work was supported by the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic through grant no. LO1204 (Sustainable development of research in the Centre of the Region Haná from the National Program of Sustainability I).

Conflict of Interest Statement

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgment

I thank to Ravindra Kale for his advice with molecular visualization system Pymol and Lenka Kuchařová for stimulating discussion.

References

Allakhverdiev, S. I., Kreslavski, V. D., Klimov, V. V., Los, D. A., Carpentier, R., and Mohanty, P. (2008). Heat stress: an overview of molecular responses in photosynthesis. Photosynth. Res. 98, 541–550. doi: 10.1007/s11120-008-9331-0

Ananyev, G., Renger, G., Wacker, U., and Klimov, V. (1994). The photoproduction of superoxide radicals and the superoxide-dismutase activity of photosystem-II - the possible involvement of cytochrome B559. Photosynth. Res. 41, 327–338. doi: 10.1007/BF00019410

Apel, K., and Hirt, H. (2004). Reactive oxygen species: metabolism, oxidative stress, and signal transduction. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 55, 373–399. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.55.031903.141701

Arato, A., Bondarava, N., and Krieger-Liszkay, A. (2004). Production of reactive oxygen species in chloride- and calcium-depleted photosystem II and their involvement in photoinhibition. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1608, 171–180. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2003.12.003

Aro, E. M., Virgin, I., and Andersson, B. (1993). Photoinhibition of Photosystem II. Inactivation, protein damage and turnover. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1143, 113–134. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(93)90134-2

Ballottari, M., Mozzo, M., Girardon, J., Hienerwadel, R., and Bassi, R. (2013). Chlorophyll triplet quenching and photoprotection in the higher plant monomeric antenna protein Lhcb5. J. Phys. Chem. B 117, 11337–11348. doi: 10.1021/jp402977y

Barra, M., Haumann, M., and Dau, H. (2005). Specific loss of the extrinsic 18 Kda protein from Photosystem II upon heating to 47 degrees C causes inactivation of oxygen evolution likely due to Ca release from the Mn-complex. Photosynth. Res. 84, 231–237. doi: 10.1007/s11120-004-7158-x

Borisova-Mubarakshina, M. M., Ivanov, B. N., Vetoshkina, D. V., Lubimov, V. Y., Fedorchuk, T. P., Naydov, I. A., et al. (2015). Long-term acclimatory response to excess excitation energy: evidence for a role of hydrogen peroxide in the regulation of photosystem II antenna size. J. Exp. Bot. 66, 7151–7164. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erv410

Bradley, R. L., Long, K. M., and Frasch, W. D. (1991). The involvement of photosystem-ii-generated H2o2 in photoinhibition. FEBS Lett. 286, 209–213. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)80975-9

Cardona, T., Sedoud, A., Cox, N., and Rutherford, A. W. (2012). Charge separation in Photosystem II: a comparative and evolutionary overview. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1817, 26–43. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2011.07.012

Chen, L. B., Jia, H. Y., Tian, Q., Du, L. B., Gao, Y. L., Miao, X. X., et al. (2012). Protecting effect of phosphorylation on oxidative damage of D1 protein by down-regulating the production of superoxide anion in photosystem II membranes under high light. Photosynth. Res. 112, 141–148. doi: 10.1007/s11120-012-9750-9

Cleland, R. E., and Grace, S. C. (1999). Voltammetric detection of superoxide production by photosystem II. FEBS Lett. 457, 348–352. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(99)01067-4

Coleman, W. J., Govindjee, and Gutowsky, H. S. (1988). The effect of chloride on the thermal inactivation of oxygen evolution. Photosynth. Res. 16, 261–276. doi: 10.1007/BF00028844

Cupellini, L., Jurinovich, S., Prandi, I. G., Caprasecca, S., and Mennucci, B. (2016). Photoprotection and triplet energy transfer in higher plants: the role of electronic and nuclear fluctuations. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 18, 11288–11296. doi: 10.1039/C6CP01437B

Dall’Osto, L., Holt, N. E., Kaligotla, S., Fuciman, M., Cazzaniga, S., Carbonera, D., et al. (2012). Zeaxanthin protects plant photosynthesis by modulating chlorophyll triplet yield in specific light-harvesting antenna subunits. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 41820–41834. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.405498

Dall’Osto, L., Lico, C., Alric, J., Giuliano, G., Havaux, M., and Bassi, R. (2006). Lutein is needed for efficient chlorophyll triplet quenching in the major LHCII antenna complex of higher plants and effective photoprotection in vivo under strong light. BMC Plant Biol. 6:32. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-6-32

Dau, H., Zaharieva, I., and Haumann, M. (2012). Recent developments in research on water oxidation by photosystem II. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 16, 3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2012.02.011

DeLano, W. L. (2002). The PYMOL Molecular Graphics System. Software. Available at: http://www.pymol.org

Dexter, D. L. (1953). A theory of sensitized luminescence in solids. J. Chem. Phys. 21, 836–850. doi: 10.1063/1.1699044

Dietz, K. J., Turkan, I., and Krieger-Liszkay, A. (2016). Redox- and reactive oxygen species-dependent signaling into and out of the photosynthesizing chloroplast. Plant Physiol. 171, 1541–1550. doi: 10.1104/pp.16.00375

Domonkos, I., Kis, M., Gombos, Z., and Ughy, B. (2013). Carotenoids, versatile components of oxygenic photosynthesis. Prog. Lipid Res. 52, 539–561. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2013.07.001

Edelman, M., and Mattoo, A. K. (2008). D1-protein dynamics in photosystem II: the lingering enigma. Photosynth. Res. 98, 609–620. doi: 10.1007/s11120-008-9342-x

Enami, I., Kitamura, M., Tomo, T., Isokawa, Y., Ohta, H., and Katoh, S. (1994). Is the primary cause of thermal inactivation of oxygen evolution in spinach PS-ii membranes release of the extrinsic 33 kda protein or of MN. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1186, 52–58. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(94)90134-1

Erickson, E., Wakao, S., and Niyogi, K. K. (2015). Light stress and photoprotection in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant J. 82, 449–465. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12825

Fine, P. L., and Frasch, W. D. (1992). The oxygen-evolving complex requires chloride to prevent hydrogen-peroxide formation. Biochemistry 31, 12204–12210. doi: 10.1021/bi00163a033

Fischer, B. B., Hideg, E., and Krieger-Liszkay, A. (2013). Production, detection, and signaling of singlet oxygen in photosynthetic organisms. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 18, 2145–2162. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.5124

Fischer, B. B., Ledford, H. K., Wakao, S., Huang, S. G., Casero, D., Pellegrini, M., et al. (2012). Singlet oxygen resistant 1 links reactive electrophile signaling to singlet oxygen acclimation in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, E1302–E1311. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1116843109

Foyer, C. H., and Noctor, G. (2009). Redox regulation in photosynthetic organisms: signaling, acclimation, and practical implications. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 11, 861–905. doi: 10.1089/ars.2008.2177

Frankel, L. K., Sallans, L., Limbach, P. A., and Bricker, T. M. (2012). Identification of oxidized amino acid residues in the vicinity of the Mn4CaO5 cluster of Photosystem II: implications for the identification of oxygen channels within the photosystem. Biochemistry 51, 6371–6377. doi: 10.1021/bi300650n

Frankel, L. K., Sallans, L., Limbach, P. A., and Bricker, T. M. (2013). Oxidized amino acid residues in the vicinity of Q(A) and Pheo(D1) of the photosystem II reaction center: putative generation sites of reducing-side reactive oxygen species. PLoS ONE 8:e58042. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058042

Gollan, P. J., Tikkanen, M., and Aro, E.-M. (2015). Photosynthetic light reactions: integral to chloroplast retrograde signalling. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 27, 180–191. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2015.07.006

Havaux, M. (2014). Carotenoid oxidation products as stress signals in plants. Plant J. 79, 597–606. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12386

Havaux, M., and Niyogi, K. K. (1999). The violaxanthin cycle protects plants from photooxidative damage by more than one mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 8762–8767. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.15.8762

Havaux, M., Triantaphylides, C., and Genty, B. (2006). Autoluminescence imaging: a non-invasive tool for mapping oxidative stress. Trends Plant Sci. 11, 480–484. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2006.08.001

Jarvi, S., Suorsa, M., and Aro, E. M. (2015). Photosystem II repair in plant chloroplasts - regulation, assisting proteins and shared components with photosystem II biogenesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1847, 900–909. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2015.01.006

Karpinski, S., Szechynska-Hebda, M., Wituszynska, W., and Burdiak, P. (2013). Light acclimation, retrograde signalling, cell death and immune defences in plants. Plant Cell Environ. 36, 736–744. doi: 10.1111/pce.12018

Khorobrykh, S. A., Karonen, M., and Tyystjarvi, E. (2015). Experimental evidence suggesting that H2O2 is produced within the thylakoid membrane in a reaction between plastoquinol and singlet oxygen. FEBS Lett. 589, 779–786. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2015.02.011

Komenda, J., Kuvikovi, S., Lupinkova, L., and Masojidek, J. (2006). “Biogenesis and structural dynamics of the photosystem II complex,” in Biotechnological Applications of Photosynthetic Proteins: Biochips, Biosensors, and Biodevices, eds M. T. Giardi and E. V. Piletska (New York, NY: Springer).

Komenda, J., Sobotka, R., and Nixon, P. J. (2012). Assembling and maintaining the photosystem II complex in chloroplasts and cyanobacteria. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 15, 245–251. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2012.01.017

Krieger-Liszkay, A. (2005). Singlet oxygen production in photosynthesis. J. Exp. Bot. 56, 337–346. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erh237

Laloi, C., and Havaux, M. (2015). Key players of singlet oxygen-induced cell death in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 6:39. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.00039

Laloi, C., Stachowiak, M., Pers-Kamczyc, E., Warzych, E., Murgia, I., and Apel, K. (2007). Cross-talk between singlet oxygen- and hydrogen peroxide-dependent signaling of stress responses in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 672–677. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609063103

Lambreva, M. D., Russo, D., Polticelli, F., Scognamiglio, V., Antonacci, A., Zobnina, V., et al. (2014). Structure/function/dynamics of photosystem II plastoquinone binding sites. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 15, 285–295. doi: 10.2174/1389203715666140327104802

Lee, K. P., Kim, C., Landgraf, F., and Apel, K. (2007). EXECUTER1- and EXECUTER2-dependent transfer of stress-related signals from the plastid to the nucleus of Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 10270–10275. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702061104

Liu, Z. F., Yan, H. C., Wang, K. B., Kuang, T. Y., Zhang, J. P., Gui, L. L., et al. (2004). Crystal structure of spinach major light-harvesting complex at 2.72 angstrom resolution. Nature 428, 287–292. doi: 10.1038/nature02373

Lupinkova, L., and Komenda, J. (2004). Oxidative modifications of the Photosystem II D1 protein by reactive oxygen species: from isolated protein to cyanobacterial cells. Photochem. Photobiol. 79, 152–162. doi: 10.1562/0031-8655nyr(2004)079<0152:OMOTPI>2.0.CO;2

Marutani, Y., Yamauchi, Y., Kimura, Y., Mizutani, M., and Sugimoto, Y. (2012). Damage to photosystem II due to heat stress without light-driven electron flow: involvement of enhanced introduction of reducing power into thylakoid membranes. Planta 236, 753–761. doi: 10.1007/s00425-012-1647-5

Mathur, S., Agrawal, D., and Jajoo, A. (2014). Photosynthesis: response to high temperature stress. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 137, 116–126. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2014.01.010

Mulo, P., Sakurai, I., and Aro, E.-M. (2012). Strategies for psbA gene expression in cyanobacteria, green algae and higher plants: from transcription to PSII repair. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1817, 247–257. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2011.04.011

Najafpour, M. M., Renger, G., Hołyńska, M., Moghaddam, A. N., Aro, E.-M., Carpentier, R., et al. (2016). Manganese compounds as water-oxidizing catalysts: from the natural water-oxidizing complex to nanosized manganese oxide structures. Chem. Rev. 116, 2886–2936. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00340

Nash, D., Miyao, M., and Murata, N. (1985). Heat inactivation of oxygen evolution in photosystem-II particles and its acceleration by chloride depletion and exogenous manganese. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 807, 127–133. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(85)90115-X

Nelson, N., and Junge, W. (2015). Structure and energy transfer in photosystems of oxygenic photosynthesis. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 84, 659–683. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-092914-041942

Nishiyama, Y., Allakhverdiev, S. I., and Murata, N. (2006). A new paradigm for the action of reactive oxygen species in the photoinhibition of photosystem II. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1757, 742–749. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2006.05.013

Noguchi, T., Tomo, T., and Kato, C. (2001). Triplet formation on a monomeric chlorophyll in the photosystem II reaction center as studied by time-resolved infrared spectroscopy. Biochemistry 40, 2176–2185. doi: 10.1021/bi0019848

op den Camp, R. G. L., Przybyla, D., Ochsenbein, C., Laloi, C., Kim, C. H., Danon, A., et al. (2003). Rapid induction of distinct stress responses after the release of singlet oxygen in arabidopsis. Plant Cell 15, 2320–2332. doi: 10.1105/tpc.014662

Pinnola, A., Dall’osto, L., Gerotto, C., Morosinotto, T., Bassi, R., and Alboresi, A. (2013). Zeaxanthin binds to light-harvesting complex stress-related protein to enhance nonphotochemical quenching in Physcomitrella patens. Plant Cell 25, 3519–3534. doi: 10.1105/tpc.113.114538

Pospíšil, P. (2009). Production of reactive oxygen species by photosystem II. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1787, 1151–1160. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2009.05.005

Pospíšil, P. (2011). Enzymatic function of cytochrome b(559) in photosystem II. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 104, 341–347. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2011.02.013

Pospíšil, P. (2012). Molecular mechanisms of production and scavenging of reactive oxygen species by photosystem II. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1817, 218–231. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2011.05.017

Pospíšil, P., Arato, A., Krieger-Liszkay, A., and Rutherford, A. W. (2004). Hydroxyl radical generation by Photosystem II. Biochemistry 43, 6783–6792. doi: 10.1021/bi036219i

Pospíšil, P., Haumann, M., Dittmer, J., Sole, V. A., and Dau, H. (2003). Stepwise transition of the tetra-manganese complex of photosystem II to a binuclear Mn-2(mu-O)(2) complex in response to a temperature jump: a time-resolved structural investigation employing X-ray absorption spectroscopy. Biophys. J. 84, 1370–1386. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74952-2

Pospíšil, P., and Prasad, A. (2014). Formation of singlet oxygen and protection against its oxidative damage in Photosystem II under abiotic stress. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 137, 39–48. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2014.04.025

Pospíšil, P., Snyrychova, I., Kruk, J., Strzalka, K., and Naus, J. (2006). Evidence that cytochrome b(559) is involved in superoxide production in photosystem II: effect of synthetic short-chain plastoquinones in a cytochrome b(559) tobacco mutant. Biochem. J. 397, 321–327. doi: 10.1042/BJ20060068

Pospíšil, P., Šnyrychová, I., and Nauš, J. (2007). Dark production of reactive oxygen species in photosystem II membrane particles at elevated temperature: EPR spin-trapping study. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1767, 854–859. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2007.02.011

Pospíšil, P., and Tyystjarvi, E. (1999). Molecular mechanism of high-temperature-induced inhibition of acceptor side of Photosystem II. Photosynth. Res. 62, 55–66. doi: 10.1023/A:1006369009170

Poudyal, R. S., Nath, K., Zulfugarov, I. S., and Lee, C. H. (2016). Production of superoxide from photosystem II-light harvesting complex II supercomplex in STN8 kinase knock-out rice mutants under photoinhibitory illumination. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 162, 240–247. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2016.06.050

Prasad, A., Ferretti, U., Sedlářová, M., and Pospíšil, P. (2016). Singlet oxygen production in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii under heat stress. Sci. Rep. 6, 20094. doi: 10.1038/srep20094

Prasad, A., Kumar, A., Suzuki, M., Kikuchi, H., Sugai, T., Kobayashi, M., et al. (2015). Detection of hydrogen peroxide in Photosystem II (PSII) using catalytic amperometric biosensor. Front. Plant Sci. 6:862. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.00862

Przybyla, D., Gobel, C., Imboden, A., Hamberg, M., Feussner, I., and Apel, K. (2008). Enzymatic, but not non-enzymatic, O-1(2)-mediated peroxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids forms part of the EXECUTER1-dependent stress response program in the flu mutant of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 54, 236–248. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03409.x

Ramel, F., Birtic, S., Ginies, C., Soubigou-Taconnat, L., Triantaphylides, C., and Havaux, M. (2012). Carotenoid oxidation products are stress signals that mediate gene responses to singlet oxygen in plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 5535–5540. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115982109

Ramel, F., Ksas, B., Akkari, E., Mialoundama, A. S., Monnet, F., Krieger-Liszkay, A., et al. (2013b). Light-induced acclimation of the Arabidopsis chlorina1 mutant to singlet oxygen. Plant Cell 25, 1445–1462. doi: 10.1105/tpc.113.109827

Ramel, F., Ksas, B., and Havaux, M. (2013c). Jasmonate: a decision maker between cell death and acclimation in the response of plants to singlet oxygen. Plant Signal. Behav. 8, e26655. doi: 10.4161/psb.26655

Ramel, F., Mialoundama, A. S., and Havaux, M. (2013a). Nonenzymic carotenoid oxidation and photooxidative stress signalling in plants. J. Exp. Bot. 64, 799–805. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ers223

Ruban, A. V., Johnson, M. P., and Duffy, C. D. P. (2012). The photoprotective molecular switch in the photosystem II antenna. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1817, 167–181. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2011.04.007

Sharma, J., Panico, M., Shipton, C. A., Nilsson, F., Morris, H. R., and Barber, J. (1997). Primary structure characterization of the photosystem II D1 and D2 subunits. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 33158–33166. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.52.33158

Shipton, C. A., and Barber, J. (1994). In-vivo and in-vitro photoinhibition reactions generate similar degradation fragments of D1 and D2 photosystem-ii reaction-center proteins. Eur. J. Biochem. 220, 801–808. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.tb18682.x

Shumbe, L., Chevalier, A., Legeret, B., Taconnat, L., Monnet, F., and Havaux, M. (2016). Singlet oxygen-induced cell death in Arabidopsis under high-light stress is controlled by OXI1 kinase. Plant Physiol. 170, 1757–1771.

Sinha, R. K., Komenda, J., Knoppova, J., Sedlářová, M., and Pospíšil, P. (2012). Small CAB-like proteins prevent formation of singlet oxygen in the damaged photosystem II complex of the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp PCC 6803. Plant Cell Environ. 35, 806–818. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2011.02454.x

Suga, M., Akita, F., Hirata, K., Ueno, G., Murakami, H., Nakajima, Y., et al. (2015). Native structure of photosystem II at 1.95 angstrom resolution viewed by femtosecond X-ray pulses. Nature 517, 99–103. doi: 10.1038/nature13991

Sun, A. Z., and Guo, F. Q. (2016). Chloroplast retrograde regulation of heat stress responses in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 7:398. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00398

Telfer, A. (2014). Singlet oxygen production by PSII under light stress: mechanism, detection and the protective role of beta-carotene. Plant Cell Physiol. 55, 1216–1223. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcu040

Thompson, L. K., Blaylock, R., Sturtevant, J. M., and Brudvig, G. W. (1989). Molecular-basis of the heat denaturation of photosystem-II. Biochemistry 28, 6686–6695. doi: 10.1021/bi00442a023

Tikkanen, M., Gollan, P. J., Mekala, N. R., Isojarvi, J., and Aro, E. M. (2014). Light-harvesting mutants show differential gene expression upon shift to high light as a consequence of photosynthetic redox and reactive oxygen species metabolism. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 369, 20130229. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2013.0229

Tiwari, A., and Pospíšil, P. (2009). Superoxide oxidase and reductase activity of cytochrome b(559) in photosystem II. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1787, 985–994. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2009.03.017

Triantaphylides, C., and Havaux, M. (2009). Singlet oxygen in plants: production, detoxification and signaling. Trends Plant Sci. 14, 219–228. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2009.01.008

Triantaphylides, C., Krischke, M., Hoeberichts, F. A., Ksas, B., Gresser, G., Havaux, M., et al. (2008). Singlet oxygen is the major reactive oxygen species involved in photooxidative damage to plants. Plant Physiol. 148, 960–968. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.125690

Umena, Y., Kawakami, K., Shen, J. R., and Kamiya, N. (2011). Crystal structure of oxygen-evolving photosystem II at a resolution of 1.9 A. Nature 473, 55–60. doi: 10.1038/nature09913

van Amerongen, H., and Croce, R. (2013). Light harvesting in photosystem II. Photosynth. Res. 116, 251–263. doi: 10.1007/s11120-013-9824-3

Vinyard, D. J., Ananyev, G. M., and Dismukes, G. C. (2013). Photosystem II: the reaction center of oxygenic photosynthesis. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 82, 577–606. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-070511-100425

Vogt, L., Vinyard, D. J., Khan, S., and Brudvig, G. W. (2015). Oxygen-evolving complex of Photosystem II: an analysis of second-shell residues and hydrogen-bonding networks. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 25, 152–158. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2014.12.040

Volkov, R. A., Panchuk, I. I, Mullineaux, P. M., and Schoffl, F. (2006). Heat stress-induced H2O2 is required for effective expression of heat shock genes in Arabidopsis. Plant Mol. Biol. 61, 733–746. doi: 10.1007/s11103-006-0045-4

von Sydow, L., Schwenkert, S., Meurer, J., Funk, C., Mamedov, F., and Schröder, W. P. (2016). The PsbY protein of Arabidopsis PhotosystemII is important for the redox control of cytochrome b559. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1857, 1524–1533. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2016.05.004

Wang, L. S., Kim, C., Xu, X., Piskurewicz, U., Dogra, V., Singh, S., et al. (2016). Singlet oxygen- and EXECUTER1-mediated signaling is initiated in grana margins and depends on the protease FtsH2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, E3792–E3800. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1603562113

Wei, X., Su, X., Cao, P., Liu, X.-Y., Chang, W., Li, M., et al. (2016). Structure of spinach photosystem II–LHCII supercomplex at 3.2 Å resolution. Nature 534, 69–74. doi: 10.1038/nature18020

Yadav, D. K., and Pospíšil, P. (2012a). Evidence on the formation of singlet oxygen in the donor side photoinhibition of photosystem II: EPR spin-trapping study. PLoS ONE 7:e45883. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045883

Yadav, D. K., and Pospíšil, P. (2012b). Role of chloride ion in hydroxyl radical production in photosystem II under heat stress: electron paramagnetic resonance spin-trapping study. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 44, 365–372. doi: 10.1007/s10863-012-9433-4

Yadav, D. K., Prasad, A., Kruk, J., and Pospíšil, P. (2014). Evidence for the involvement of loosely bound plastosemiquinones in superoxide anion radical production in photosystem II. PLoS ONE 9:e115466. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0115466

Yamamoto, Y., Aminaka, R., Yoshioka, M., Khatoon, M., Komayama, K., Takenaka, D., et al. (2008). Quality control of photosystem II: impact of light and heat stresses. Photosynth. Res. 98, 589–608. doi: 10.1007/s11120-008-9372-4

Yamashita, A., Nijo, N., Pospíšil, P., Morita, N., Takenaka, D., Aminaka, R., et al. (2008). Quality control of photosystem II - Reactive oxygen species are responsible for the damage to photosystem II under moderate heat stress. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 28380–28391. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710465200

Yamauchi, Y., Furutera, A., Seki, K., Toyoda, Y., Tanaka, K., and Sugimoto, Y. (2008). Malondialdehyde generated from peroxidized linolenic acid causes protein modification in heat-stressed plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 46, 786–793. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2008.04.018

Yoshioka, M., Uchida, S., Mori, H., Komayama, K., Ohira, S., Morita, N., et al. (2006). Quality control of photosystem II. Cleavage of reaction center D1 protein in spinach thylakoids by FtsH protease under moderate heat stress. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 21660–21669. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602896200

Keywords: photoinhibition, heat inactivation, singlet oxygen, free oxygen radicals, lipid peroxidation

Citation: Pospíšil P (2016) Production of Reactive Oxygen Species by Photosystem II as a Response to Light and Temperature Stress. Front. Plant Sci. 7:1950. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01950

Received: 23 September 2016; Accepted: 07 December 2016;

Published: 26 December 2016.

Edited by:

Maya Velitchkova, Institute of Biophysics and Biomedical Engineering, Bulgarian Academy of Science, BulgariaReviewed by:

Christine Helen Foyer, University of Leeds, UKAnjana Jajoo, Devi Ahilya University, India

Copyright © 2016 Pospíšil. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Pavel Pospíšil, cGF2ZWwucG9zcGlzaWxAdXBvbC5jeg==

Pavel Pospíšil

Pavel Pospíšil