95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Plant Sci. , 10 October 2012

Sec. Plant Proteomics and Protein Structural Biology

Volume 3 - 2012 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2012.00228

This article is part of the Research Topic Plant Protein Phosphorylation View all 11 articles

MAP3Kε1 and MAP3Kε2 are a pair of Arabidopsis thaliana genes that encode protein kinases related to cdc7p from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. We have previously shown that the map3kε1;map3kε2 double-mutant combination causes pollen lethality. In this study, we have used an ethanol-inducible promoter construct to rescue this lethal phenotype and create map3kε1-/-;map3kε2-/- double-mutant plants in order to examine the function of these genes in the sporophyte. These rescued double-mutant plants carry a yellow fluorescent protein (YFP)-MAP3Kε1 transgene under the control of the alcohol-inducible AlcA promoter from Aspergillus nidulans. The double-mutant plants were significantly smaller and had shorter roots than wild-type when grown in the absence of ethanol treatment. Microscopic analysis indicated that cell elongation was reduced in the roots of the double-mutant plants and cell expansion was reduced in rosette leaves. Treatment with ethanol to induce expression of YFP-MAP3Kε1 largely rescued the leaf phenotypes. The double-mutant combination also caused embryos to arrest in the early stages of development. Through the use of YFP reporter constructs we determined that MAP3Kε1 and MAP3Kε2 are expressed during embryo development, and also in root tissue. Our results indicate that MAP3Kε1 and MAP3Kε2 have roles outside of pollen development and that these genes affect several aspects of sporophyte development.

The Arabidopsis genes MAP3Kε1 and MAP3Kε2 encode protein kinases that were originally named as members of the MAP kinase kinase kinase (MAP3K) gene family (MAPK Group, 2002). More recent analysis has indicated that MAP3Kε1 and MAP3Kε2 are more closely related to cdc7p from Schizosaccharomyces pombe and Cdc15p from Saccharomyces cerevisiae, which are not MAP3Ks (Jouannic et al., 2001; Champion et al., 2004a,b). Cdc7p is one of the components of the septation initiation network (SIN). The SIN has been shown to regulate the formation of the septum in fission yeast after chromosome segregation has been completed (Simanis, 2003). The functionally equivalent pathway in the budding yeast S. cerevisiae is called the mitotic exit network (MEN), and it regulates cytokinesis and mitotic exit (Simanis, 2003). SIN-like elements such as sid1p-, cdc16-, and mob1p-related proteins have been identified in both the Arabidopsis and rice (Oryza sativa) genomes (Bedhomme et al., 2008), leading to the speculation that a SIN-like pathway may exist in plants.

The Arabidopsis genome encodes the following signaling proteins closely related to the core elements of the SIN pathway: AtMAP3Kε1, AtMAP3Kε2, AtSGP1, AtSGP2, AtMAP4Kα1, and AtMAP4Kα2 (Champion et al., 2004b; Bedhomme et al., 2008). These Arabidopsis genes partially rescue homologous fission yeast mutants and encode proteins that interact with their fission yeast counterparts. There is currently, however, no direct evidence in support of the idea that plants use these SIN-related components to regulate cytokinesis (Champion et al., 2004b; Bedhomme et al., 2008).

We have previously reported that single-mutant plants carrying T-DNA null alleles for either map3kε1 or map3kε2 displayed no obvious abnormal phenotypes, while the double-mutant combination caused pollen lethality (Chaiwongsar et al., 2006). These results suggested that functional compensation could be occurring between MAP3Kε1 and MAP3Kε2 such that the loss of one gene is compensated for by the second gene (Liljegren et al., 2000). This appears to be the case for pollen development, but remained an untested hypothesis for the sporophyte since the pollen-lethality of the double-mutant combination prevents the formation of a homozygous double-mutant sporophyte. It has been reported that MAP3Kε1 is expressed in all organs of the plant, and that MAP3Kε1 and MAP3Kε2 are expressed strongly in regions of the sporophyte that contain actively dividing cells (Jouannic et al., 2001; Chaiwongsar et al., 2006; Bedhomme et al., 2009). These reports indicate that MAP3Kε1 and MAP3Kε2 are likely to have functions outside of pollen development.

In order to generate map3kε1-/-;map3kε2-/- double-mutant plants we made use of an alcohol-inducible transcription system to rescue the pollen lethal phenotype of the map3kε1;map3kε2 double-mutant combination. This system is derived from the filamentous fungus Aspergillus nidulans and has been successfully adopted for use in plants (Caddick et al., 1998; Roslan et al., 2001; Laufs et al., 2003). It is composed of the alcR-encoded transcriptional activator (AlcR) and a promoter derived from the alcA promoter (Kulmburg et al., 1992). In A. nidulans, these elements allow for the controlled activation of a series of structural genes important for alcohol catabolism (Pickett et al., 1987). In our study we used the alcR/alcA system to express yellow fluorescent protein (YFP)-MAP3Kε1 in map3kε1;map3kε2 double-mutant pollen, thereby allowing for the generation of map3kε1-/-;map3kε2-/- plants. We report here on our phenotypic analysis of these rescued map3kε1-/-;map3kε2-/- double-mutant plants. Taken together our genetic analyses indicated that MAP3Kε1 and MAP3Kε2 are involved in multiple aspects of plant development, including root cell elongation, rosette leaf expansion, and embryo deve- lopment.

We have previously described the T-DNA null alleles map3kε1 and map3kε2 (Chaiwongsar et al., 2006). In that previous work we observed that homozygous single-mutant lines for either map3kε1 or map3kε2 did not display any obvious abnormal phenotypes when grown under standard laboratory conditions. We also found that the map3kε1;map3kε2 double-mutant combination caused pollen lethality (Chaiwongsar et al., 2006). These results suggested that there is functional redundancy between MAP3Kε1 and MAP3Kε2 during pollen development. Because map3kε1;map3kε2 pollen is non-viable, however, it is not straightforward to generate a plant that is homozygous double-mutant for these T-DNA null alleles. For this reason one cannot directly explore via genetic analysis the function of this pair of potentially redundant genes in the sporophyte.

In order to overcome this challenge we needed an experimental strategy that would allow map3kε1;map3kε2 double-mutant pollen to be viable, which would in turn allow a homozygous double-mutant sporophyte to be formed. The strategy that we chose was to place the wild-type MAP3Kε1 coding region under the transcriptional control of an alcohol-inducible promoter system and induce expression of MAP3Kε1 during pollen and embryo development so that these processes could proceed normally. After seed had been produced by these plants, the progeny could be grown under conditions that do not induce expression of the MAP3Kε1 transgenic construct, thereby allowing us to observe any phenotypic consequences of the reduced levels of MAP3Kε1 and MAP3Kε2.

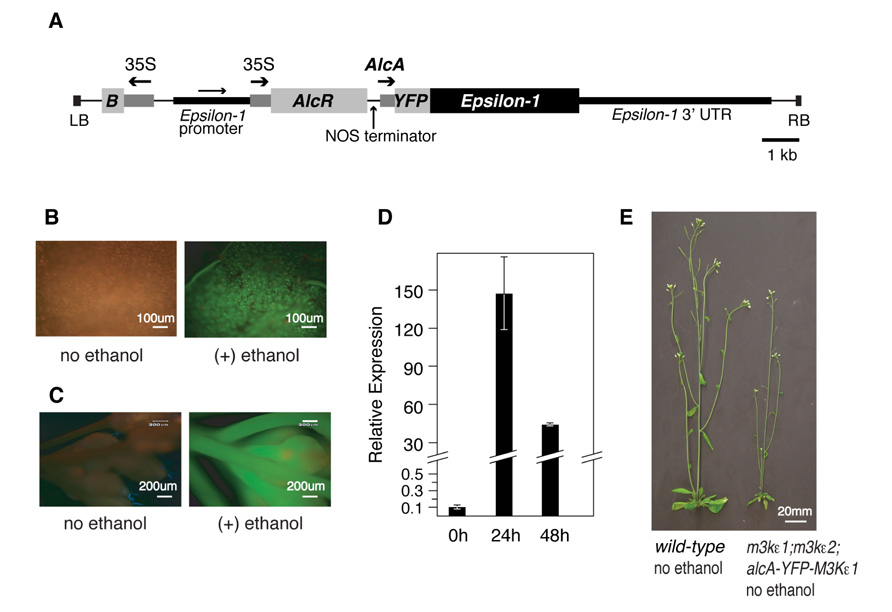

We began by constructing a plasmid in which a YFP tag is translationally fused to the wild-type MAP3Kε1 coding sequence (CDS) under the transcriptional control of the ethanol-inducible alcA promoter (Figure 1A; Caddick et al., 1998; Roslan et al., 2001; Deveaux et al., 2003). We included the YFP tag on this construct so that we could monitor YFP-MAP3Kε1 expression at the protein level via fluorescence microscopy. This construct was then introduced via Agrobacterium-mediated transformation into plants that were homozygous for map3kε2 and heterozygous for map3kε1. PCR-based genotyping was used to identify map3kε1-/+;map3kε2-/- primary transformants that were also carrying the alcA:YFP-MAP3Kε1 construct. In order to determine if these plants carried a functional copy of the alcA:YFP-MAP3Kε1 construct, we monitored YFP-MAP3Kε1 protein expression using fluorescence microscopy. Twenty-four hours after treatment with a 1% ethanol spray, strong induction of YFP fluorescence was observed throughout the aerial tissue of the plants, including leaves and flowers (Figures 1B,C), indicating that the alcA:YFP-MAP3Kε1 construct present in these lines was performing as expected.

FIGURE 1. Using an alcohol-inducible promoter construct to generate map3kε1-/-;map3kε2-/- double-mutant plants. (A) Plasmid map of the T-DNA portion of the alcohol-inducible YFP-MAP3Kε1 expression construct. Arrows indicate the direction of transcription for each of the promoters. The MAP3Kε1 native promoter is present on the construct as an artifact of the cloning procedures used to assemble this plasmid. “B” indicates the coding region for the Bar gene that serves as a plant-selectable marker by encoding resistance to the herbicide Basta. “LB” and “RB” indicate the T-DNA left border and right border sequences. “35S” indicates the cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter. “AlcA” indicates the alcohol-inducible promoter element. Scale bar indicates 1 kb. (B,C) Epifluorescence images of a rosette leaf (B) or an inflorescence (C) of an map3kε1-/-;map3kε2-/-;alc-YFP-MAP3Kε1 plant before and after exposure to exogenous ethanol. Images were collected 24 h after ethanol treatment. Green color indicates YFP fluorescence. Red color is due to autofluorescence of the plant tissue. (D) Two-week-old map3kε1-/-;map3kε2-/-;alc-YFP-MAP3Kε1 seedlings carrying the alcA:YFP-MAP3Kε1 construct were sprayed with ethanol to induce YFP-MAP3Kε1 expression. RNA was isolated at the indicated time points. “Relative expression” indicates the RNA level of YFP-MAP3Kε1 transcripts relative to MAP3Kε1 in wild-type control seedlings not carrying the alcA:YFP-MAP3Kε1 construct. Standard deviation is based on three independent replicates of real-time quantitative RT-PCR. Expression of YFP-MAP3Kε1 the zero-hour time point prior to ethanol treatment was at a level of 0.1 compared to wild-type MAP3Kε1 in control seedlings. (E) Representative 3-week-old wild-type Columbia and map3kε1-/-;map3kε2-/-;alc-YFP-MAP3Kε1 plants grown in soil without exposure to exogenous ethanol.

In order to rescue the lethal phenotype displayed by map3kε1;map3kε2 double-mutant pollen, developing flowers of map3kε1-/+;map3kε2-/-;alcA:YFP-MAP3Kε1 plants were sprayed with 1% ethanol on a daily basis throughout their life-cycle in order to activate expression of alcA:YFP-MAP3Kε1 and allow double-mutant pollen grains to survive. Progeny from these ethanol-treated plants were genotyped and several map3kε1-/-;map3kε2-/-;alcA:YFP-MAP3Kε1 individuals were identified. These results indicated that the alcA:YFP-MAP3Kε1 construct was able to rescue the map3kε1;map3kε2 pollen lethal phenotype, and that the YFP tag did not interfere with MAP3Kε1 function during pollen development.

Progeny derived from eight independently transformed map3kε1-/-;map3kε2-/-;alc-YFP-MAP3Kε1 lines were screened using quantitative reverse-transcriptase PCR to find the line with the lowest background level of YFP-MAP3Kε1 expression. In the absence of ethanol treatment, the double-mutant line chosen for phenotypic analysis in this study expressed YFP-MAP3Kε1 at a level that was 10-fold lower than that of native MAP3Kε1 expressed in wild-type plants (Figure 1D). When treated with exogenous ethanol, seedlings carrying this construct displayed strong induction of the YFP-MAP3Kε1 gene up to a level ca. 150 times higher than that of native MAP3Kε1 expressed in wild-type plants (Figure 1D). When grown in soil in the absence of exogenous ethanol treatment, progeny of this map3kε1-/-;map3kε2-/-;alc-YFP-MAP3Kε1 line had an overall reduction in the size of their rosette leaves and bolts (Figure 1E).

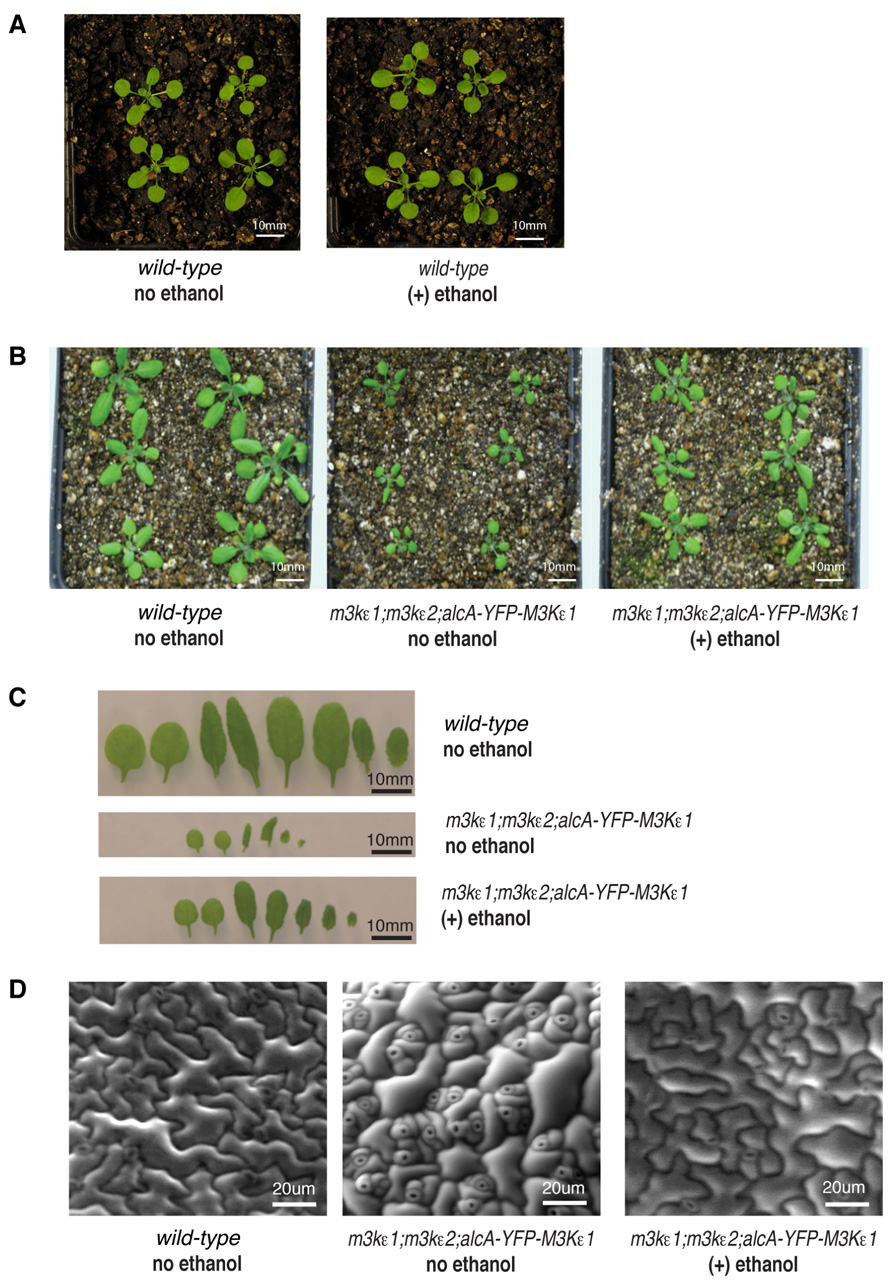

In order to determine if the reduced size of rosette leaves seen in map3kε1-/-;map3kε2-/-;alc-YFP-MAP3Kε1 plants grown in the absence of ethanol was due to the low level of MAP3Kε1 expression in these plants relative to wild-type, we performed the following experiment. Two pots of map3kε1-/-;map3kε2-/-;alc-YFP-MAP3Kε1 plants were grown side-by-side, along with wild-type controls. One pot of map3kε1-/-;map3kε2-/-;alc-YFP-MAP3Kε1 plants was sprayed with 1% ethanol every 2 days throughout development, while the second was sprayed with water only. We also subjected wild-type Columbia plants to the same regimen of water and ethanol treatments to determine if ethanol treatment had any effect on the growth of wild-type plants. As seen in Figure 2A, treatment with ethanol did not affect the growth of wild-type plants. Spraying map3kε1-/-;map3kε2-/-;alc-YFP-MAP3Kε1 plants with ethanol to induce YFP-MAP3Kε1 expression, however, resulted the partial rescue of the reduced-leaf-size phenotype (Figures 2B,C).

FIGURE 2. Reduced cell expansion in rosette leaves of map3kε1-/-;map3kε2-/-;alc-YFP-MAP3Kε1 plants. (A,B) Fourteen-day-old soil-grown plants. (C) Detached rosette leaves from 14-day-old soil grown plants arranged in developmental order from left to right. (D) Environmental scanning electron microscope images of leaf epidermal cells from 14-day-old soil grown plants. For ethanol treatment, plants were sprayed with 1% ethanol (v/v) every 2 days throughout development. “no ethanol” samples were sprayed on the same time schedule with distilled water.

We also performed scanning electron microscopy of the leaf epidermis of map3kε1-/-;map3kε2-/-;alc-YFP-MAP3Kε1 plants to observe the size and shape of the epidermal cells. This analysis revealed that the epidermal cells of untreated map3kε1-/-;map3kε2-/-;alc-YFP-MAP3Kε1 plants were heterogeneous in size, with a majority of the cells being much smaller than those of wild-type (Figure 2D). Some relatively large cells were also observed in the untreated mutant lines, but these cells did not have the typical jig-saw shape of wild-type epidermal cells. These results indicate that MAP3Kε1/2 may be important for the normal expansion of leaf epidermal cells. The cellular phenotypes displayed by the untreated map3kε1-/-;map3kε2-/-;alc-YFP-MAP3Kε1 plants were partially rescued when the plants were sprayed with ethanol every 2 days throughout development to induce expression of YFP-MAP3Kε1 (Figure 2C).

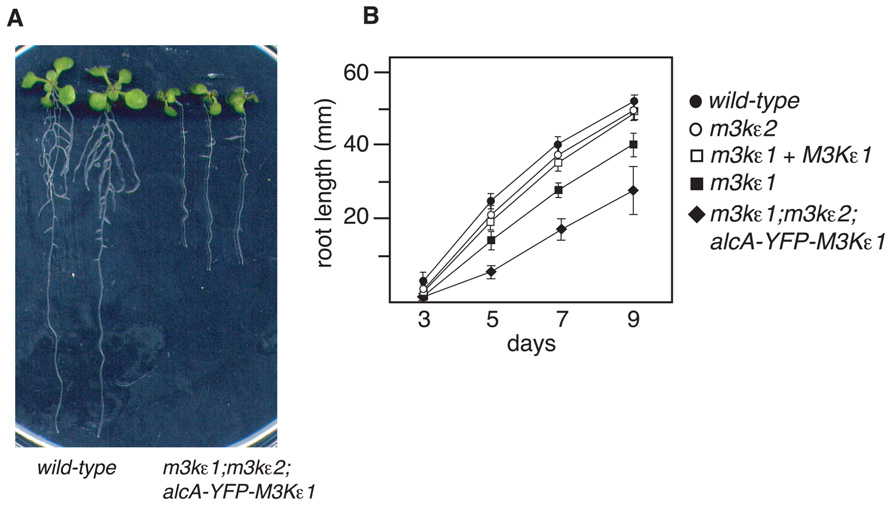

To investigate the role of MAP3Kε1/2 in root growth, seeds of the map3kε1-/-;map3kε2-/-;alc-YFP-MAP3Kε1 mutant line as well as a wild-type control were sown on agar plates containing growth media. Root length was then measured after 5 days of growth on vertically oriented plates. We observed that the primary roots of the map3kε1-/-;map3kε2-/-;alc-YFP-MAP3Kε1 plants were ca. 40% shorter than wild-type (Figure 3A). In order to further investigate the contribution of map3kε1 and map3kε2 to this phenotype, we performed a time-course experiment to measure root length over the course of 9 days of growth on vertical agar plates. As additional controls, this experiment included map3kε1 and map3kε2 homozygous single-mutant lines as well as the map3kε1-/-;map3kε2-/-;alc-YFP- MAP3Kε1 line.

FIGURE 3. Reduced root length of map3kε1-/-;map3kε2-/-; alc-YFP-MAP3Kε1 plants. (A) Nine-day-old plants grown on vertically oriented agar plates. (B) Primary root length of seedlings grown on agar plates. “days” indicates age of seedling. map3kε1+MAP3Kε1 indicates a line that is homozygous for the map3kε1 mutation and also carries an ectopic copy of the wild-type MAP3Kε1 locus. Mean root length is reported. n ≥ 30 for each genotype. Error bars indicate standard error.

As shown in Figure 3B, the primary roots of map3kε1 homozygous single-mutant lines were significantly shorter than those of wild-type. This phenotype is fully rescued by the presence of an ectopic copy of the wild-type MAP3Kε1 genomic locus (Figure 3B). By comparison, the roots of map3kε1-/-;map3kε2-/-;alc-YFP-MAP3Kε1 plants were found to be even shorter than those of the map3kε1 single-mutant.

We next attempted to use ethanol-induction to rescue the short-root phenotype of map3kε1-/-;map3kε2-/-;alc-YFP-MAP3Kε1 plants. We tested a variety of ethanol-treatment procedures but were not able to generate substantial YFP-MAP3Kε1 expression in root tissue as determined by fluorescent microscopy, and no phenotypic rescue was observed.

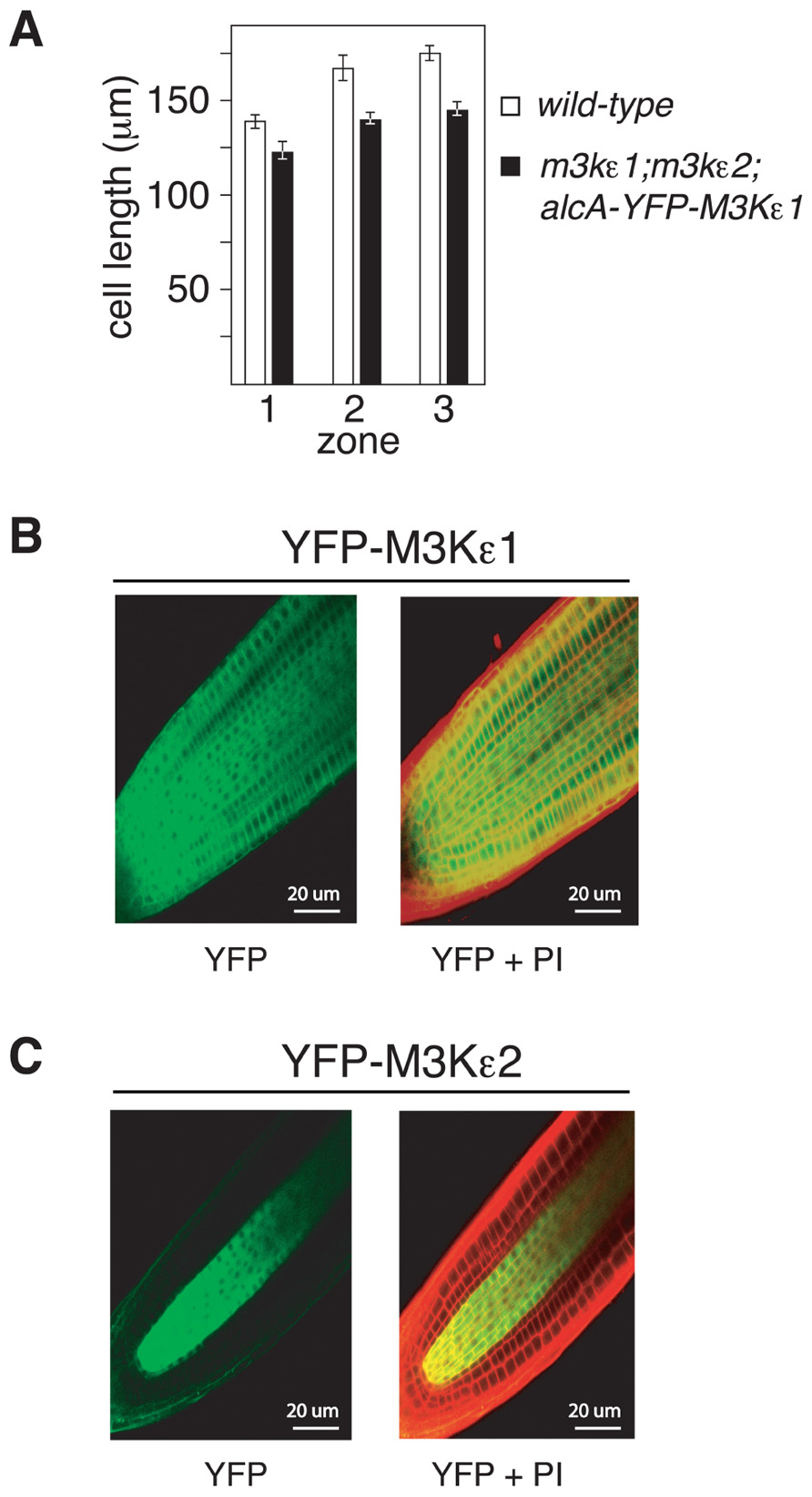

To further explore the cause of the short-root phenotype displayed by map3kε1-/-;map3kε2-/-;alc-YFP-MAP3Kε1 plants, epidermal cell length was measured in three different zones of 7-day-old roots. These zones correspond to the root meristem, the elonga- tion zone, and the mature zone where cell elongation has ceased (Cruz-Ramirez et al., 2004). Root epidermal cells of map3kε1-/-; map3kε2-/-;alc-YFP-MAP3Kε1 seedlings were shorter than wild-type in all of these zones. On average the root epidermal cells were ca. 20% shorter in the map3kε1-/-;map3kε2-/-;alc-YFP-MAP3Kε1 plants when compared to wild-type, indicating that cell elongation is reduced (Figure 4A). Because the overall length of the primary root in map3kε1-/-;map3kε2-/-;alc-YFP-MAP3Kε1 plants is ca. 40% less than wild-type (Figure 3), reduced cell elongation alone cannot fully account for the total reduction in root length. The mutant lines must also have fewer total cells in the primary root, suggesting a reduction in the rate of new cell production in the roots of map3kε1-/-;map3kε2-/-;alc-YFP-MAP3Kε1 plants.

FIGURE 4. Reduced cell elongation in the roots of map3kε1-/-; map3kε2-/-;alc-YFP-MAP3Kε1 plants. (A) Mean length of root epidermal cells from three previously defined zones of root growth (Cruz-Ramirez et al., 2004). Zone 1 is the root meristem, zone 2 is the cell elongation zone, and zone 3 is the mature zone where cell elongation has ceased. n ≥ 15. Error bars represent the standard error. (B,C) Confocal microscopy images of primary root tips of transgenic lines expressing YFP-MAP3Kε1 or YFP-MAP3Kε2 from their respective native promoters. Roots were stained with propidium iodide (PI) to highlight cell walls (indicated by red color in the images). Left panels display YFP fluorescence in green. Right panels are merged images of the YFP and PI fluorescent signals. Emission was detected at 590–640 nm for PI and 500–550 nm for YFP.

We also documented the expression pattern of MAP3Kε1 and MAP3Kε2 in Arabidopsis primary roots using YFP fusion constructs. YFP-MAP3Kε1 and YFP-MAP3Kε2 translational fusions under the transcriptional control of their respective native promoters were introduced into wild-type Arabidopsis plants via Agrobacterium-mediated transformation. Transgenic lines were generated and fluorescence microscopy was used to detect YFP-MAP3Kε1 or YFP-MAP3Kε2 expression. After seed germination, YFP-MAP3Kε1 was strongly expressed throughout the root apical meristem (Figure 4B). By contrast, YFP-MAP3Kε2 expression in the root apical meristem was largely restricted to vascular tissues (Figure 4C). These results indicate that MAP3Kε1 and MAP3Kε2 are both expressed in the root apical meristem region with overlapping, but distinct expression patterns.

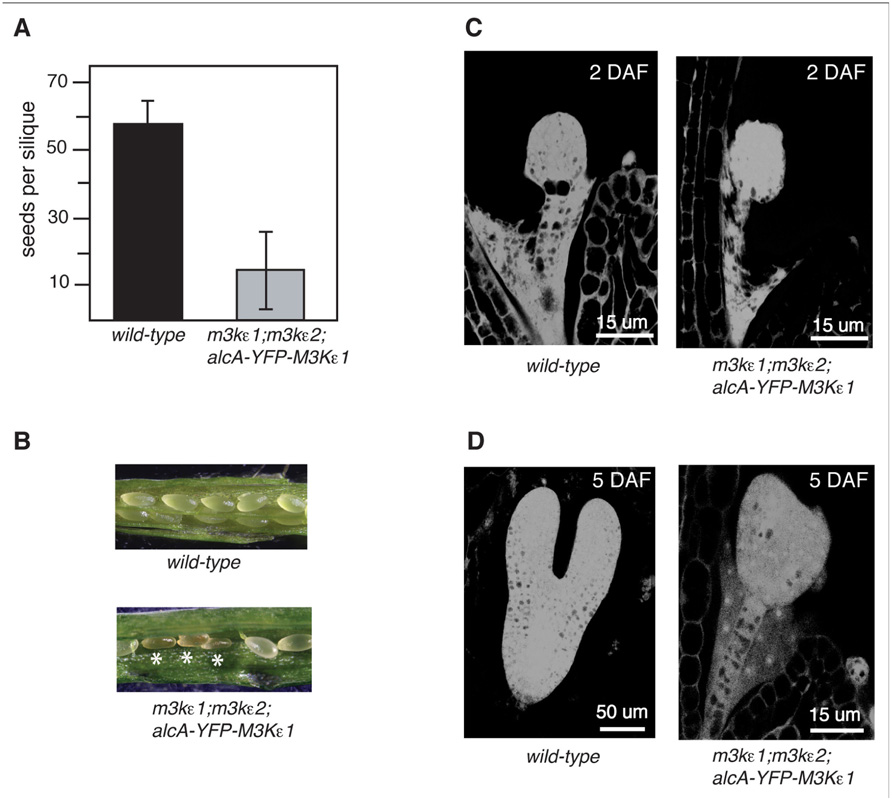

map3kε1-/-;map3kε2-/-;alc-YFP-MAP3Kε1 plants produce fewer seeds than wild-type when grown in the absence of exogenous ethanol (Figure 5B). The mutant plants produce an average of 15 seeds per silique, compared to 55 seeds per silique for wild-type (Figure 5B). Although map3kε1;map3kε2 pollen is not viable (Chaiwongsar et al., 2006), Alexander’s staining showed that pollen from map3kε1-/-;map3kε2-/-;alc-YFP-MAP3Kε1 plants was viable in the absence of exogenous ethanol treatment, suggesting that the alcA:YFP-MAP3Kε1 construct is expressed in the absence of ethanol treatment in developing pollen (data not shown). This phenomenon might be due to the fact that the ethanolic fermentation pathway is normally activated during pollen development (Mellema et al., 2002), resulting in the production of acetaldehyde and ethanol, which can both act as inducers of the alcA promoter (Tadege and Kuhlemeier, 1997).

FIGURE 5. Seed production and embryo development of map3kε1-/-;map3kε2-/-;alc-YFP-MAP3Kε1 plants. (A) Mean number of seeds produced per silique for plants grown in the absence of exogenous ethanol treatment. Error bars indicate standard error. n ≥150 siliques for each genotype. (B) Siliques of 3-week-old plants grown in the absence of exogenous ethanol treatment. Shriveled seeds are indicated by white asterisks. (C,D) Microscopic analysis of embryo development. (C) Images at 2 days after flowering (DAF). (D) Images at 5 DAF. Images were obtained by capturing the autofluorescence of fixed embryos using a confocal microscope.

We have previously shown that map3kε1;map3kε2 double-mutant female gametophytes develop normally (Chaiwongsar et al., 2006). Therefore, the decrease in seed production of the map3kε1-/-;map3kε2-/-;alc-YFP-MAP3Kε1 plants may be due to a disruption of seed development, rather than reduced pollen fitness. To test this possibility, map3kε1-/-;map3kε2-/-;alc-YFP-MAP3Kε1 plants were grown and allowed to self-pollinate in the absence of exogenous ethanol treatment. Developing seeds from the map3kε1-/-;map3kε2-/-;alc-YFP-MAP3Kε1 plants were then analyzed microscopically. Siliques from wild-type and map3kε1-/-;map3kε2-/-;alc-YFP-MAP3Kε1 plants were removed from the main shoot and compared. During normal Arabidopsis seed development, the external appearance of immature seeds changes from white to green, and then to brown at ca. 15–17 days after flowering (DAF). At 7 DAF, we observed that a portion of the seeds from the map3kε1-/-;map3kε2-/-;alc-YFP-MAP3Kε1 plants were smaller than wild-type and brown (Figure 5A). By 16 DAF, a majority of the seeds from map3kε1-/-;map3kε2-/-;alc-YFP-MAP3Kε1 siliques appeared collapsed and shriveled (data not shown).

Immature seeds within a single wild-type silique normally develop at approximately the same rate (Sparkes et al., 2003). In wild-type plants grown in our laboratory conditions, the embryos reached the globular stage by 2 DAF and the torpedo stage by 5–6 DAF (Figures 5C,D). However, many of the embryos from map3kε1-/-;map3kε2-/-;alc-YFP-MAP3Kε1 plants grown under the same conditions displayed delayed development. All of the map3kε1-/-;map3kε2-/-;alc-YFP-MAP3Kε1 embryos reached the globular stage at the normal time of 2 DAF, but at 6 DAF development was stalled at the globular or transition stage in many of the embryos (Figure 5D). At 7 DAF, most of the map3kε1-/-;map3kε2-/-;alc-YFP-MAP3Kε1 seeds had collapsed and the embryos were arrested at either the globular or heart stage (data not shown).

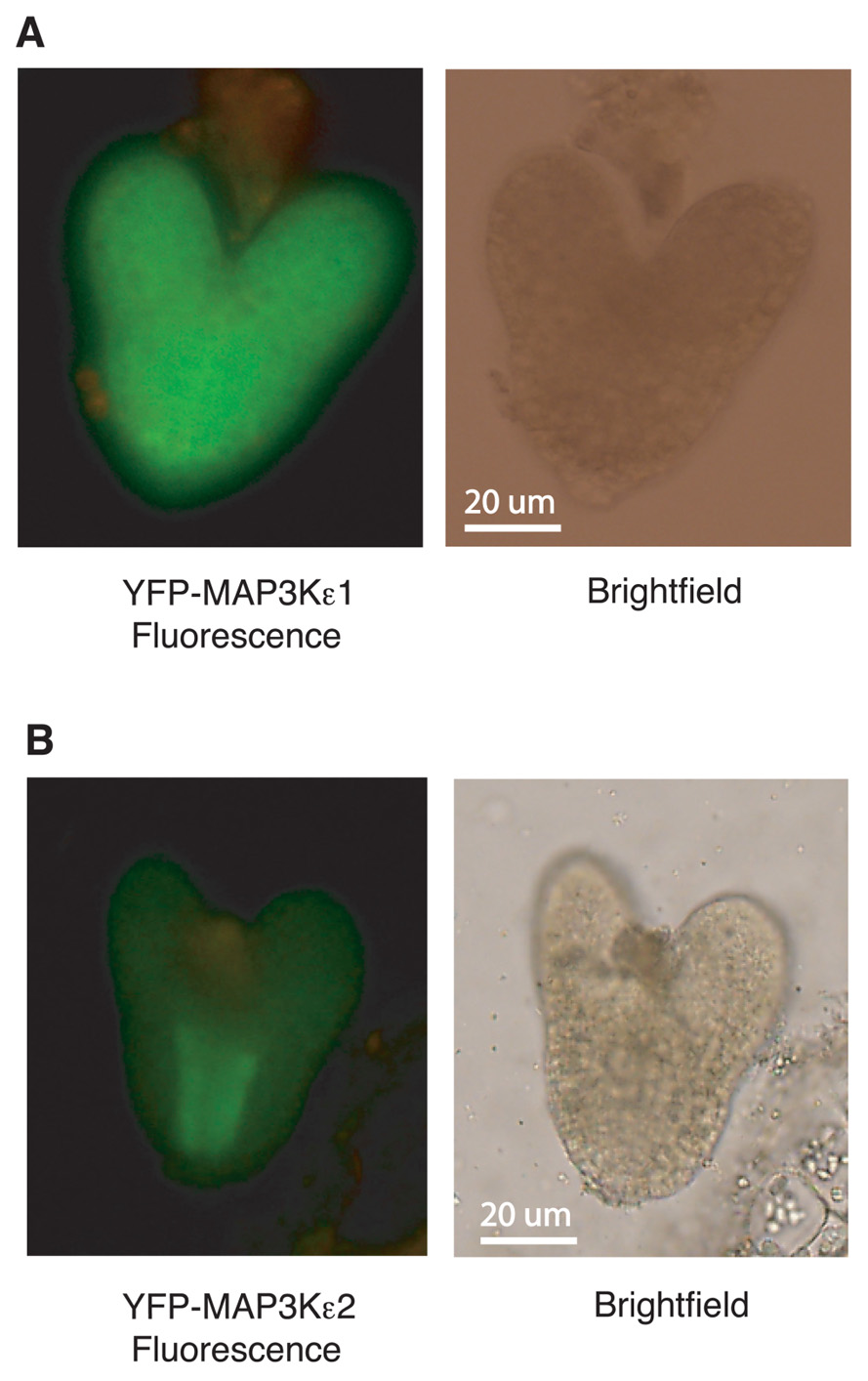

The arrest of embryo development observed with map3kε1-/-;map3kε2-/-;alc-YFP-MAP3Kε1 plants suggested that MAP3Kε1, MAP3Kε2 play an important role in normal embryo development. If these proteins are directly involved in embryo development, then one would expect the proteins to be expressed in developing embryos. To directly explore this question we used the YFP-MAP3Kε1 and YFP-MAP3Kε2, translational fusion constructs described above to determine if these proteins are expressed in developing embryos. These constructs express the fusion proteins using the gene’s respective native promoters. YFP fluorescence was detected via fluorescence microscopy in the developing embryos of plants expressing YFP-MAP3Kε1 and YFP-MAP3Kε2 (Figure 6). YFP-MAP3Kε1 expression was observed throughout all the tissues of the embryo. By contrast, the expression pattern of YFP-MAP3Kε2 was noticeably concentrated in the developing vascular cells (Figure 6).

FIGURE 6. MAP3Kε1 and MAP3Kε2 are expressed during embryo development. (A,B) Embryos from wild-type plants carrying a YFP-MAP3Kε1 construct or a YFP-MAP3Kε2 construct under the transcriptional control of their respective native promoters were removed from seeds and observed using epifluorescence microscopy to detect YFP-MAP3Kε1 and YFP-MAP3Kε2 protein expression. Green color represents YFP-MAP3Kε1 or YFP-MAP3Kε2 expression. Brightfield and fluorescence images of each embryo are shown.

We have previously shown that the map3kε1-/-;map3kε2-/- double-mutant combination causes pollen lethality (Chaiwongsar et al., 2006). In order to study the function of MAP3Kε1/2 in the sporophyte, we used an ethanol-inducible system to provide conditional expression of MAP3Kε1 during pollen development, thereby rescuing the map3kε1;map3kε2 pollen lethality and allowing us to generate map3kε1-/-;map3kε2-/- double-mutant plants. Using this system, YFP-MAP3Kε1 expression could be strongly induced by spraying plants with a solution of 1% ethanol. It should be noted that the basal level of expression from the alc-YFP-MAP3Kε1 construct in the absence of exogenous ethanol treatment was not zero. The map3kε1-/-;map3kε2-/-;alc-YFP-MAP3Kε1 line that we chose for detailed study expressed YFP-MAP3Kε1 at a level that was 10% that of the wild-type MAP3Kε1 gene in wild-type plants. The presence of detectable transcription from the alcA promoter in transgenic plants in the absence of exogenous inducer is commonly observed and is possibly caused by the production of an endogenous inducer in tissue where the oxygen level is low (Roberts et al., 2005).

The residual expression of YFP-MAP3Kε1 by the alc promoter that we observed in our experiments highlights some of the advantages and disadvantages of using the alc promoter to rescue pollen lethal mutations. Residual expression can be seen as a disadvantage of this system because it prevents one from obtaining a true null allele for the gene of interest, so one cannot observe the effect of the complete loss of a protein on the growth and development of the plant. Residual expression could also, however, be seen as an advantage of the system. In cases where the complete absence of a gene product causes embryo lethality, residual expression from the alc promoter may be able to provide enough gene product to allow the embryo to develop to maturity so that the effect of the partial loss of the gene product of interest can be evaluated in developing seedlings and plants. In the case of our study, the residual expression of MAP3Kε1 driven by the alc promoter in the absence of ethanol was sufficient to allow seedling germination and plant growth, but cell expansion in roots and leaves was compromised. The leaky expression of the alc promoter therefore allows one to produce what is effectively a “weak” allele of a locus for which a null allele would otherwise be lethal. If a true null allele is desired, then it may be possible to use other inducible expression systems such as the dexamethasone-inducible system, the beta-estradiol-inducible system, or a heat shock-inducible promoter in order to obtain a lower background level of gene expression (Borghi, 2010). Alternatively, a pollen-specific promoter (Twell et al., 1990) could be used to rescue the pollen-lethal mutation during pollen development, thus allowing for the formation of a homozygous-mutant embryo. If the basal expression level of the pollen-specific promoter in other stages of plant development was sufficiently low, then one would be able to observe the effect of loss of that gene product during embryo development and beyond.

map3kε1-/-;map3kε2-/-;alc-YFP-MAP3Kε1 plants were able to germinate and grow in the absence of ethanol treatment. We observed that these map3kε1-/-;map3kε2-/-;alc-YFP-MAP3Kε1 plants had reduced primary root cell elongation and reduced epidermal leaf cell expansion. This reduced cell expansion may explain the overall small size of the mutant plants. The induction of YFP-MAP3Kε1 expression in these plants via exogenous ethanol treatment could partially rescue the leaf phenotypes, indicating that the map3kε1 mutation in the map3kε2 background is responsible for these phenotypes.

The short-root phenotype of map3kε1-/-;map3kε2-/-;alc-YFP-MAP3Kε1 plants could not be rescued by exogenous ethanol treatment. Despite the application of various concentrations of exogenous ethanol and various methods of ethanol application, including direct application or exposure of plants to ethanol vapor, we could not detect substantial expression of YFP-MAP3Kε1 in root tissue, even though YFP-MAP3Kε1 expression was strongly induced in the leaves of these same plants (data not shown). These results suggest that the ethanol-inducible construct used in these experiments may not be suitable for providing inducible gene expression in root tissue.

We have previously shown that MAP3Kε1 is localized to the plasma membrane (Chaiwongsar et al., 2006), suggesting that MAP3Kε1 may be involved in the process of cell expansion by performing an as of yet unknown function at the plasma membrane. This view is supported by the abnormality of the plasma membrane in map3kε1;map3kε2 double-mutant pollen (Chaiwongsar et al., 2006). In addition, the thicker intine layer observed with map3kε1;map3kε2 double-mutant pollen suggests that MAP3Kε1 may also affect cell wall synthesis. Future studies will be needed to pinpoint the specific aspect of cell expansion that is influenced by MAP3Kε1 and MAP3Kε2.

Using fluorescence microscopy and YFP-tagged fusion proteins, we observed that MAP3Kε1 and MAP3Kε2 were expressed in the embryos. A majority of the embryos that develop on map3kε1-/-;map3kε2-/-;alc-YFP-MAP3Kε1 plants arrest their development at the globular or heart stages. Because map3kε1-/-;map3kε2-/-;alc-YFP-MAP3Kε1 plants have a low basal level of transcription from the alcA:YFP-MAP3Kε1 construct, it seems likely that viable seeds are able to form on map3kε1-/-;map3kε2-/-;alc-YFP-MAP3Kε1 plants as a result of slightly higher alc-YFP-MAP3Kε1 activity in a given developing embryo. We frequently observed that the first siliques that develop on map3kε1-/-;map3kε2-/-;alc-YFP-MAP3Kε1 plants yield more viable seeds than later siliques, but it is not clear what the mechanism responsible for this differential seed yield is.

In roots the expression of MAP3Kε2 seems to be focused in the area of vascular tissue, while MAP3Kε1 is more uniformly distributed across all tissue types. In addition, we observed that map3kε1-/- single-mutant plants have shorter roots than wild-type, whereas map3kε2-/- single-mutants are indistinguishable from wild-type. These results suggest that MAP3Kε1 can compensate for the absence of MAP3Kε2, while the converse is not true. The embryo-lethality observed in map3kε1-/-;map3kε2-/-;alc-YFP-MAP3Kε1 plants indicates that absence of both gene products is lethal, suggesting substantial functional redundancy within this pair of genes. One interesting question raised by these results is how the expression of MAP3Kε2 in the vascular tissue of roots is able to compensate for the absence of MAP3Kε1 in the non-vascular tissues of map3kε1-/- single-mutant plants. It is possible that a low level of MAP3Kε2 expression occurs outside of vascular tissue that is below the level of detection afforded by the visualization of YFP fluorescence. Alternatively, MAP3Kε2 expression could be induced in non-vascular tissues in the map3kε1-/- mutant background. Further study will be required to determine the extent to which MAP3Kε1 and MAP3Kε2 have unique versus redundant roles in plant growth and development.

In this study we have demonstrated how an ethanol-inducible promoter system can be used to rescue a pollen-lethal mutation, thereby allowing one to study mutations in the sporophyte that would otherwise be lethal. Our initial analysis of the resulting map3kε1-/-;map3kε2-/- double-mutant plants indicated a role for these kinases in the processes of cell elongation and embryo development. Further studies will be needed to pinpoint the specific pathways in which MAP3Kε1 and MAP3Kε2 function. The work reported here provides a starting point for more detailed functional analysis of this pair of genes and also provides an example of the utility of the alcohol-inducible system for studying pollen-lethal mutations.

Arabidopsis thaliana (Columbia ecotype) were grown under continuous light at 22–25°C in soil. To activate expression of the alcohol-inducible alcA-YFP-MAP3Kε1 construct in plants growing in soil, the plants were sprayed with 1% (v/v) ethanol every 2 days throughout development.

In order to create the YFP-MAP3Kε1 fusion construct, a wild-type MAP3Kε1 genomic clone previously described (Chaiwongsar et al., 2006) was modified using site-directed mutagenesis to add recognition sites for the restriction enzymes AvrII and AgeI immediately after the start codon. The YFP CDS was then PCR amplified from a plasmid vector using PCR primers that added an NheI site to the 5′. end of the CDS and an AgeI site to the 3′. end. This PCR-amplified fragment containing the YFP CDS was then ligated to the modified MAP3Kε1 clone using sticky ends generated by AvrII, AgeI, and NheI cleavage. NheI sticky ends are identical to those produced by AvrII. The resulting construct contains the YFP CDS fused in frame to the 5′. end of the MAP3Kε1 coding region and retains the MAP3Kε1 native promoter. The same strategy was used to construct the YFP-MAP3Kε2 fusion construct. The resulting plasmids were introduced into plants using Agrobacterium-mediated transformation (Clough and Bent, 1998).

In order to construct the ethanol-inducible version of the YFP-MAP3Kε1 fusion protein, recognition sites for the restriction enzyme RsrII were introduced immediately downstream of the ATG start codon of the YFP-MAP3Kε1 coding region described above. A 3.7 kb fragment from the plasmid pBinSRNACATN (Caddick et al., 1998) was then PCR amplified using primers that added RsrII sites to the PCR product and cloned into the RsrII sites in YFP-MAP3Kε1. This 3.7 kb fragment contained an AlcR expression cassette as well as the AlcA promoter. The resulting plasmid contains the YFP-MAP3Kε1 gene under the transcriptional control of the AlcA promoter (Figure 1A). This vector was introduced into Arabidopsis plants via Agrobacterium-mediated transformation (Clough and Bent, 1998).

Seeds were surface sterilized with 95% (v/v) ethanol for 5 min, air dried, and sown on 0.5× Murashige and Skoog basal salt mixture media (pH 5.8; Sigma) with 0.7% agar (w/v). After sowing, seeds were allowed to imbibe in the dark at 4°C for 2 days and were then grown on vertically oriented plates under constant light at 22–24°C. To measure the root lengths, images were captured using a flat-bed scanner and analyzed with Adobe Illustrator software.

Confocal microscopy was used to collect images of root epidermal cells to measure cell length. For these experiments, cell walls were stained using propidium iodide (PI) and optical sections were obtained using a Zeiss LSM 510 Meta Confocal microscope (Zeiss, Thornwood, NY, USA). For PI staining, fresh plant tissue was transferred to a solution of 10 µg/mL of PI (Sigma) for 15–30 min. Imaging was performed using a 568-nm excitation line and an emission window of 585–610-nm. Epifluorescence images were captured digitally using an Olympus DP70 camera (Center Valley, PA, USA) attached to an Olympus BX60 epifluorescence microscope (Center Valley, PA, USA).

To detect YFP fluorescence in embryos, embryos were removed from the seed coats at various stages and viewed with an epifluorescence microscope. To study embryo development, embryos were fixed with 4% glutaraldehyde (in 12.5 mM cacodylate, pH 6.9) overnight. After fixation, the embryos were dehydrated through a 20, 40, 60, 80, and 100% ethanol series for 20 min per step. After dehydration, embryos were cleared in 1:1 (v/v) benzyl benzoate:benzyl alcohol for minimum of 2 h. Embryos were then mounted with glycerol and observed with a Zeiss LSM 510 Meta Confocal microscope with a 488-nm argon laser and an LP539 filter to detect autofluorescence.

In order to measure the expression level of YFP-MAP3Kε1 expression in the map3kε1-/-;map3kε2-/-;alc-YFP-MAP3Kε1 lines, total RNA was isolated from rosette leaf tissue using a Qiagen RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). First-strand cDNA was prepared using 100 µg of total RNA with the Super Script First-Strand synthesis system (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The resulting first-strand cDNA was diluted 1:100 with water and used as a template for real-time, quantitative RT-PCR amplification using an iCYCLER PCR system (BioRad, Hercules, CA, USA). SYBR Green (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA) was used to detect RT-PCR product accumulation. Primers for the actin gene ACT2 were used as a control (Genbank Accession: U41998). To detect MAP3Kε1 expression, the predicted cDNA sequence of MAP3Kε1 was used to design the following pair of PCR primers: ε1-RT-A1, 5′.-AAAAACATTGTGAAGTATCTTGGGTCGTC-3′.; ε1-RT-A2, 5′.-GCTTCTTTACGAATTTCGCGAGAACGATC-3′. (Chaiwongsar et al., 2006).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The authors would like to thank Peter Jester for technical assistance with these experiments. This work was supported by a grant from the National Science Foundation (grant number MCB-0447750).

Bedhomme, M., Jouannic, S., Champion, A., Simanis, V., and Henry, Y. (2008). Plants, MEN and SIN. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 46, 1–10.

Bedhomme, M., Mathieu, C., Pulido, A., Henry, Y., and Bergounioux, C. (2009). Arabidopsis monomeric G proteins, markers of early and late events in cell differentiation. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 53, 177–185.

Caddick, M. X., Greenland, A. J., Jepson, I., Krause, K. P., Qu, N., Riddell, K. V., et al. (1998). An ethanol inducible gene switch for plants used to manipulate carbon metabolism. Nat. Biotechnol. 16, 177–180.

Chaiwongsar, S., Otegui, M. S., Jester, P. J., Monson, S. S., and Krysan, P. J. (2006). The protein kinase genes MAP3Kepsilon1 and MAP3Kepsilon2 are required for pollen viability in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 48, 193–205.

Champion, A., Picaud, A., and Henry, Y. (2004a). Reassessing the MAP3K and MAP4K relationships. Trends Plant Sci. 9, 123–129.

Champion, A., Jouannic, S., Guillon, S., Mockaitis, K., Krapp, A., Picaud, A., et al. (2004b). AtSGP1, AtSGP2 and MAP4K alpha are nucleolar plant proteins that can complement fission yeast mutants lacking a functional SIN pathway. J. Cell Sci. 15, 4265–4275.

Clough, S. J., and Bent, A. F. (1998). Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium-media- ted transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 16, 735–743.

Cruz-Ramirez, A., Lopez-Bucio, J., Ramirez-Pimentel, G., Zurita-Silva, A., Sanchez-Calderon, L., Ramirez-Chavez, E., et al. (2004). The xipotl mutant of Arabidopsis reveals a critical role for phospholipid metabolism in root system development and epidermal cell integrity. Plant Cell 16, 2020–2034.

Deveaux, Y., Peaucelle, A., Roberts, G. R., Coen, E., Simon, R., Mizukami, Y., et al. (2003). The ethanol switch: a tool for tissue-specific gene induction during plant development. Plant J. 36, 918–930.

Jouannic, S., Champion, A., Segiu-Simarro, J. M., Salimova, E., Picuad, A., Tregear, J., et al. (2001). The protein kinases AtMAP3Kepsilon1 and BnMAP3Kepsilon1 are functional homologues of S. pombe cdc7p and may be involved in cell division. Plant J. 26, 637–649.

Kulmburg, P., Judewicz, N., Mathieu, M., Lenouvel, F., Sequeval, D., and Felenbok, B. (1992). Specific binding sites for the activator protein, ALCR, in the alcA promoter of the ethanol regulon of Aspergillus nidulans. J. Biol. Chem. 267, 21146–21153.

Laufs, P., Coen, E., Konenberger, J., Traas, J., and Doonan, J. (2003). Separable roles of UFO during floral development revealed by conditional restoration of gene function. Development 130, 785–796.

Liljegren, S. J., Ditta, G. S., Eshed, Y., Savidge, B., Bowman, J. L., and Yanofsky, M. F. (2000). SHATTERPROOF MADS-box genes control seed dispersal in Arabidopsis. Nature 404, 766–770.

MAPK Group. (2002). Mitogen-activated protein kinase cascades in plants: a new nomenclature. Trends Plant Sci. 7, 301–308.

Mellema, S., Eichenberger, W., Rawyler, A., Suter, M., Tadege, M., and Kuhlemeier, C. (2002). The ethanolic fermentation pathway supports respiration and lipid biosynthesis in tobacco pollen. Plant J. 30, 329–336.

Pickett, M., Gwynne, D. I., Buxton, F. P., Elliot, R., Davies, R. W., Lockinton, R. A., et al. (1987). Cloning and characterization of the alcA gene of Aspergillus nidulans. Gene 51, 217–216.

Roberts, G. R., Garoosi, G. A., Koroleva, O., Ito, M., Laufs, P., Leader, D. J., et al. (2005). The alc-GR system: a modified alc gene switch designed for use in plant tissue culture. Plant Physiol. 138, 1259–1267.

Roslan, H. A., Salter, M. G., Wood, C. D., White, M. R., Croft, K. P., Robson, F., et al. (2001). Characterization of the ethanol-inducible alc gene-expression system in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 26, 225–235.

Simanis, V. (2003). Events at the end of mitosis in the budding and fission yeasts. J. Cell Sci. 116, 4263–4275.

Sparkes, I. A., Brandizzi, F., Slocombe, S. P., El-Shami, M., Hawes, C., and Baker, A. (2003). An Arabidopsis pex10 null mutant is embryo lethal, implicating peroxisomes in an essential role during plant embryogenesis. Plant Physiol. 133, 1809–1819.

Tadege, M., and Kuhlemeier, C. (1997). Aerobic fermentation during tobacco pollen development. Plant Mol. Biol. 35, 343–345.

Keywords: MAP kinase, MAP3Kε1, MAP3Kε2, cell expansion, embryo development, Arabidopsis

Citation: Chaiwongsar S, Strohm AK, Su S-H and Krysan PJ (2012) Genetic analysis of the Arabidopsis protein kinases MAP3Kε1 and MAP3Kε2 indicates roles in cell expansion and embryo development. Front. Plant Sci. 3:228. doi:10.3389/fpls.2012.00228

Received: 30 July 2012; Accepted: 21 September 2012;

Published online: 10 October 2012.

Edited by:

Steven Huber, United States Department of Agriculture, USAReviewed by:

Etienne H. Meyer, Max Planck Society, GermanyCopyright: © 2012 Chaiwongsar, Strohm, Su and Krysan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits use, distribution and reproduction in other forums, provided the original authors and source are credited and subject to any copyright notices concerning any third-party graphics etc.

*Correspondence: Patrick J. Krysan, Department of Horticulture and Genome Center of Wisconsin, University of Wisconsin at Madison, 1575 Linden Drive, Madison, WI 53706, USA. e-mail:ZnBhdEBiaW90ZWNoLndpc2MuZWR1

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.