94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

Front. Physiol., 06 March 2025

Sec. Integrative Physiology

Volume 16 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2025.1543217

Background: Cognitive enhancement treatments are limited, and while High-Intensity Interval Training (HIIT) has been suggested to improve cognitive function, high-quality evidence remains scarce. This meta-analysis evaluates the effects of HIIT on cognitive performance compared to moderate-intensity continuous training (MICT) and control groups in older adults and cognitively Impaired Patients.

Methods: A systematic search of PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane Library databases was conducted for articles published until 10 October 2024. Eighteen studies were included, comparing cognitive outcomes across HIIT, MICT, and control groups. Cognitive tests evaluated included the Stroop test, Digit Span Test (DST), Trail Making Test (TMT), and the MOST test.

Results: HIIT significantly improved performance compared to MICT in the Stroop test (SMD = −0.8, 95% CI: −1.3 to −0.2) and DST (SMD = 0.3, 95% CI: −0.0–0.5). Compared to control groups, HIIT significantly enhanced performance in the TMT (SMD = −0.7, 95% CI: −1.3 to 0.0) and MOST test (SMD = −1.2, 95% CI: −1.8 to −0.7).

Conclusion: This meta-analysis supports the efficacy of HIIT in enhancing cognitive functions, particularly in cognitive flexibility, working memory, task switching, attention control, and inhibitory control. These findings suggest that HIIT can be an effective intervention for improving cognitive behavior in older adults and cognitively Impaired Patients.

Systematic Review Registration: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/, Identifier CRD42023413879.

Over the past few decades, a great number of studies have revealed numerous benefits of exercise for physical health (Fiuza-Luces et al., 2018; D’Onofrio et al., 2023; Sellami et al., 2021), particularly its positive impact on the brain and cognitive function (Stillman et al., 2020; Mandolesi et al., 2018; Hertzog et al., 2008). Cognitive function refers to the ability of the brain to process information, solve problems, and perform tasks, including executive functions, memory, language skills, and cognitive flexibility. As the aging population continues to grow, the importance of maintaining and enhancing cognitive function becomes increasingly prominent. Therefore, investigating how exercise positively affects cognitive function has become a critical area of study.

High-intensity interval training (HIIT) has garnered considerable attention as a time-efficient and effective exercise method. This training modality involves alternating periods of high-intensity exercise with rest or low-intensity exercise for recovery (Wewege et al., 2018). Previous applications and studies have primarily focused on training methods for athletes, and HIIT has been shown to significantly enhance their performance in sports (Reindell and Roskamm, 1959; Reindell, 1962; Billat, 2001). Not until the 21st century, did the research focus shift to the clinical applications of HIIT, particularly its potential for cognitive function improvement and brain rehabilitation (Calverley et al., 2020; Poon et al., 2023; LaCount et al., 2022). Several studies have already confirmed that HIIT offers greater health benefits compared to traditional moderate-intensity continuous training (MICT) (Stensvold et al., 2020; Cuddy et al., 2019; Taylor et al., 2020). The physiological mechanisms underlying these effects may include increased Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF), which could all support cognitive function (Jiménez-Maldonado et al., 2018).

Despite the growing body of research on HIIT and cognitive function, current findings remain inconsistent. Some studies have found positive effects of HIIT on cognitive function. For instance, the study by Gjellesvik et al. (2021) suggests that HIIT can improve executive functions; Drollette and Meadows (2022) propose improvements in working memory; Tian et al. (2021) report enhanced cognitive flexibility. However, other studies failed to observe significant effects, as stated by Sokołowski et al. (2021), who found no association between HIIT and cognitive performance. Nicolas Hugues’ (Hugues et al., 2021) article reviews the therapeutic application of HIIT in stroke rehabilitation. However, most of the article focuses on changes in serum biomarkers related to the treatment, without clearly describing the specific behavioral rehabilitation outcomes. These studies and reviews primarily target elderly individuals or populations after a stroke, both of which are characterized by cognitive deficits. Therefore, this paper aims to synthesize and categorize these populations to investigate the effects of HIIT on cognitive reshaping.

This meta-analysis aims to provide a comprehensive assessment of HIIT’s effects on cognitive function, clarify its physiological mechanisms, and offer practical guidance for implementing HIIT in cognitive rehabilitation, especially for populations at risk of cognitive decline.

This systematic review was designed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Liberati et al., 2009) and followed the Cochrane systematic review guidelines for literature search and selection (Moher et al., 2009).

Computerized searches were conducted in PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane Library databases for articles published until 10 October 2024. Boolean search methods were employed with the following mesh terms: [“high-intensity intermittent exercise” OR “high-intensity intermittent training”] AND [“cognitive accessibility” OR “cognitive balance”]. The search strategy is detailed in Appendix). All articles considered in the search were restricted to peer-reviewed publications written in English.

To determine the inclusion criteria for the study, we followed the PICOS framework. Population: The study population included different age groups, such as children, adolescents, adults, and elderly individuals. It encompassed both healthy individuals and those with physical and mental illnesses, athletes and trained individuals, All participants exhibited some degree of cognitive and awareness decline, but their physical health status was sufficient to perform exercise modalities such as HIIT and MICT. The search was not restricted by age, race, or gender, which can provide a more comprehensive understanding of the effects of the intervention across different demographic groups. Intervention: High-intensity exercise was defined as exercise intervals lasting up to 5 min, which elicited a peak heart rate of at least 80%. These intervals were characterized by rest or light exercise. Any form of exercise that met these intensity criteria (e.g., treadmill running, cycling, whole-body exercises) was included. There were no limitations on the duration of HIIT interventions. Both acute HIIT interventions and long-term HIIT interventions lasting several months were included in the review. Comparison: The controls were those who did no exercise and continued their regular daily activities or were engaged in reading. Additionally, the comparison between HIIT and MICT was included in the search. MICT is defined as exercise lasting no less than 20 min and performed at a maximum heart rate of 75% or lower, without short rest or lighter exercise periods. Outcome: Cognitive function assessments including the Stroop Test, Digit Span Test (DST), TMT and The More-odd Shifting Task (MOST). Study design: the predominant study design was randomized controlled trial (RCT).

After the article search by an initial reviewer, two reviewers screened the study titles and abstracts for further selection. Any discrepancies were resolved through discussion with a third reviewer until a consensus was reached.

The risk of bias within each domain of the included studies was assessed using a domain-based assessment tool from the Cochrane Collaboration (Higgins et al., 2019) (Figure 1), Since most of the included studies employed a crossover design, allocation concealment and blinding were not reported, indicating potential methodological weaknesses. Figure 2 presents the proportion of methodological quality items across the studies. The quality assessment was conducted by two reviewers, with any discrepancies resolved by consulting a third reviewer.

Titles and abstracts of all identified studies from the search were independently reviewed by two reviewers. Each reviewer created a relevant abstract list for reading and determined eligibility according to the inclusion criteria. Any discrepancies were resolved by a third reviewer. Data were extracted by one reviewer from the selected papers, which were then validated by a second reviewer. The data included for analysis encompassed the number of studies included, study design, participant numbers (including participants in the control group), details of HIIT interventions, outcome measures related to HIIT (such as Stroop, TMT, DST, MOST), and corresponding effect size.

In this study, meta-analysis was performed using a random-effects model, with the pooled effect size represented as standardized mean difference (SMD) with 95% confidence interval (95%CI). To investigate the impact of HIIT on changes in cognitive function, an overall analysis was conducted. Furthermore, sensitivity analyses were conducted to detect if specific studies contributed significantly to heterogeneity (I2). Based on I2 values, heterogeneity was evaluated as not important (0%–40%), moderate (30%–60%), substantial (50%–90%), or considerable (75%–100%) (Higgins et al., 2003). Publication bias was not evaluated due to the limited number of studies involved (less than 10). All analyses were performed using the R statistical software (version 4.2.1). Results were considered statistically significant when the p-value of the overall effect (z-value) was less than 0.05.

According to the inclusion criteria, a total of 1,598 articles were retrieved from databases (PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane Library). After removing duplicate articles, 1,526 articles remained for further screening of titles and abstracts. Subsequently, 263 articles were assessed for eligibility by reading the full texts. Finally, 18 articles (Gjellesvik et al., 2021; Tian et al., 2021; Tsukamoto et al., 2016; Kujach et al., 2018; Khandekar et al., 2023; Shi et al., 2022; Alves et al., 2014; Coetsee and Terblanche, 2017; de Lima et al., 2022; Fiorelli et al., 2019; Lee et al., 2019; Mekari et al., 2020; Piraux et al., 2021; Tottori et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2022a; Ahmad et al., 2024; Mou et al., 2023; Oliva et al., 2023) were included in the systematic review (Figure 3).

All included articles focused on the effects of HIIT on cognition. The characteristics of the included studies are provided in Table 1. In this meta-analysis, the predominant study design was RCTs, supplemented by randomized balanced crossover experiments, crossover design experiments, and randomized crossover experiments. Cognitive function was assessed primarily using cognitive scales including the Stroop Test, DST, TMT, MOST. These scales covered various cognitive domains, including executive function, attention, short-term memory, and cognitive flexibility.

This meta-analysis focused on the impact of HIIT on executive function. Executive function, as a fundamental aspect of cognitive process (Nguyen et al., 2019), encompasses crucial domains such as working memory, inhibitory control, and cognitive flexibility. We utilized the Stroop Test as primary outcome to quantify the effect of HIIT on executive function.

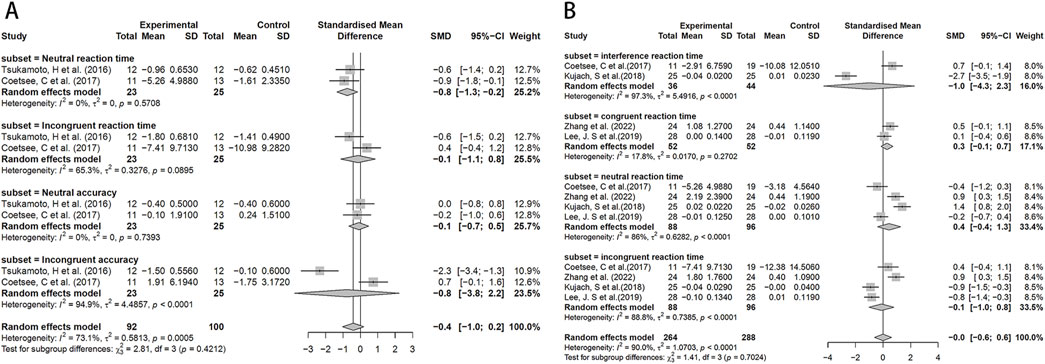

Since the Stroop test results were expressed in multiple ways, for analysis purposes, we only selected data expressed in the same way. The analysis results showed that compared to MICT, HIIT significantly reduced neural response time (SMD = −0.8, 95%CI: −1.3 to −0.2). However, its effects on incongruent response time, neutral accuracy, and incongruent accuracy were not statistically significant (Figure 4A). No significant difference was observed in interference response time, neutral response time, and incongruent response time between the HIIT group and the control group, suggesting similar effects across studies (Figure 4B).

Figure 4. Forest plot for between-group effects of HIIT on the stroop test. (A) Comparison of HIIT and MICT in Stroop test results; (B) Comparison of HIIT and control in Stroop test.

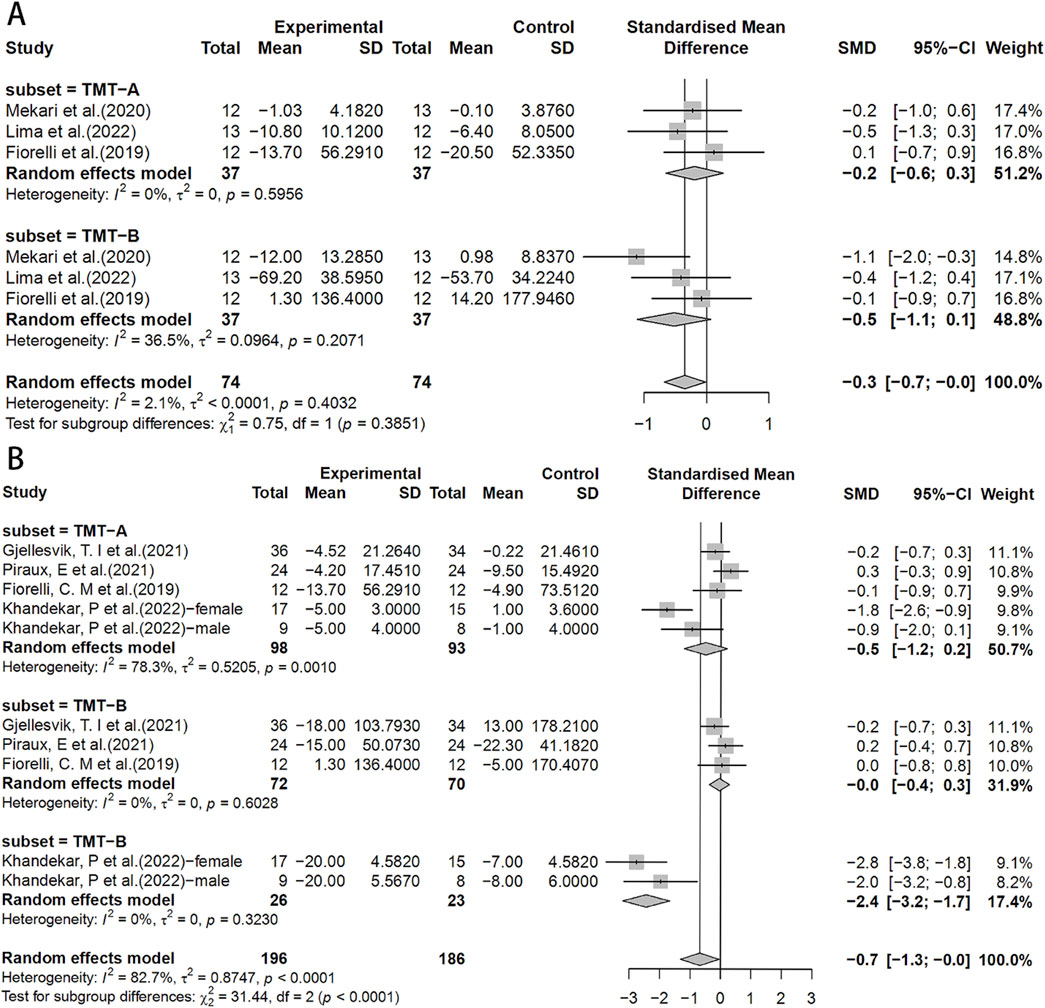

In the TMT test, the HIIT group exhibited a significant effect compared to the control group (SMD = −0.7, 95% CI: −1.3 to 0.0) (Figure 5B). Similarly, there were no significant differences between the HIIT group and the MICT group in the TMT test (Figure 5A).

Figure 5. Forest plot for between-group effects of HIIT on the TMT test. (A) Comparison of HIIT and MICT in TMT test; (B) Comparison of HIIT and control in TMT test. TMT: Trail Making Test.

In the DST test, the HIIT group showed a potentially slightly better working memory span compared to the MICT group (SMD = 0.3, 95%CI: −0.0–0.5) (Figure 6A). However, no significant effects were found in the HIIT group when compared to the control group, although chance factors cannot be completely ruled out (Figure 6B).

Figure 6. Forest plot for between-group effects of HIIT on the DST test. (A) Comparison of HIIT and MICT in DST test; (B) Comparison of HIIT and control in DST test. DST: Digit Span Test.

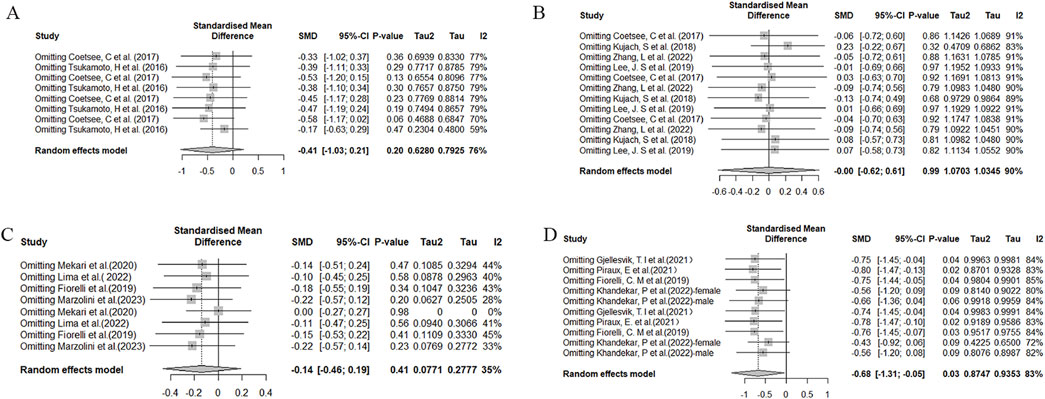

In the MOST test, no significant differences were observed between HIIT and MICT (Figure 7A), but a significant effect was observed in the HIIT group when compared to the control (SMD = −1.2, 95%CI: −1.8 to −0.7) (Figure 7B).

Figure 7. Forest plot for between-group effects of HIIT on the MOST test. (A) Comparison of HIIT and MICT in MOST test; (B) Comparison of HIIT and control in MOST test. MOST: The More-odd Shifting Task.

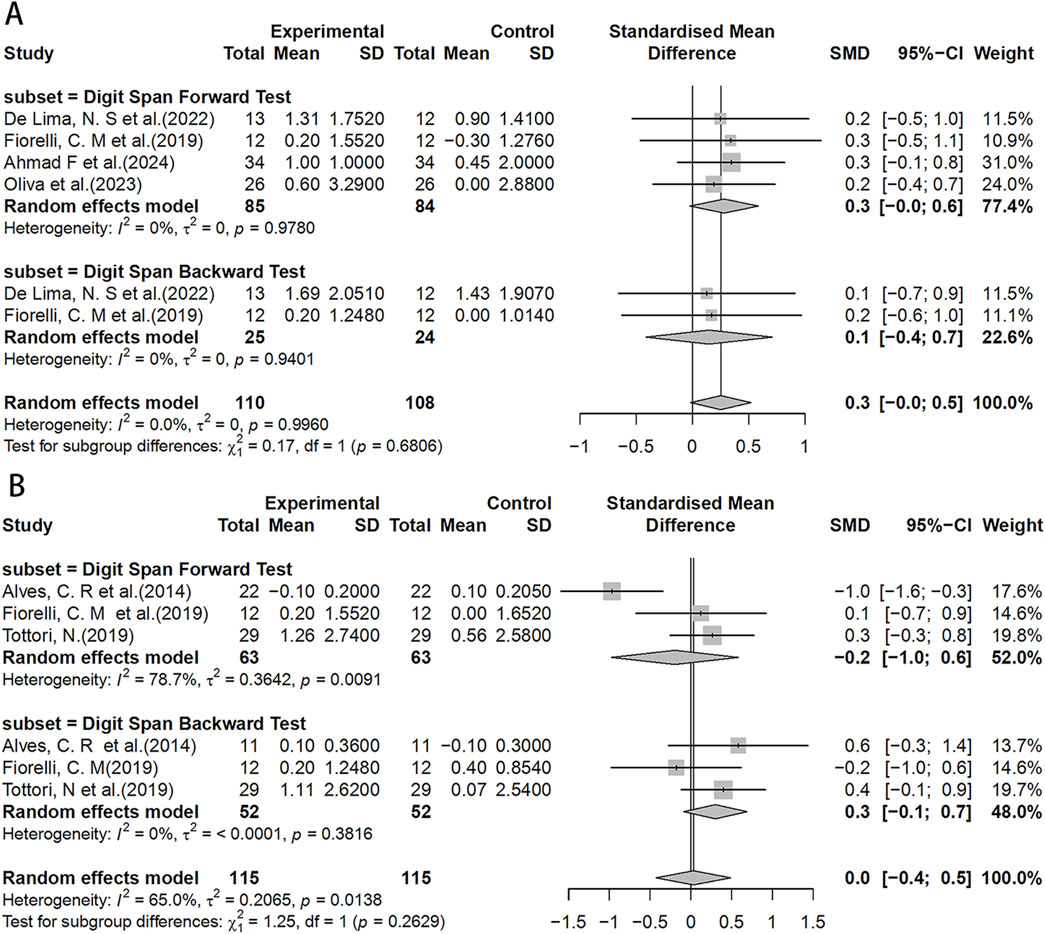

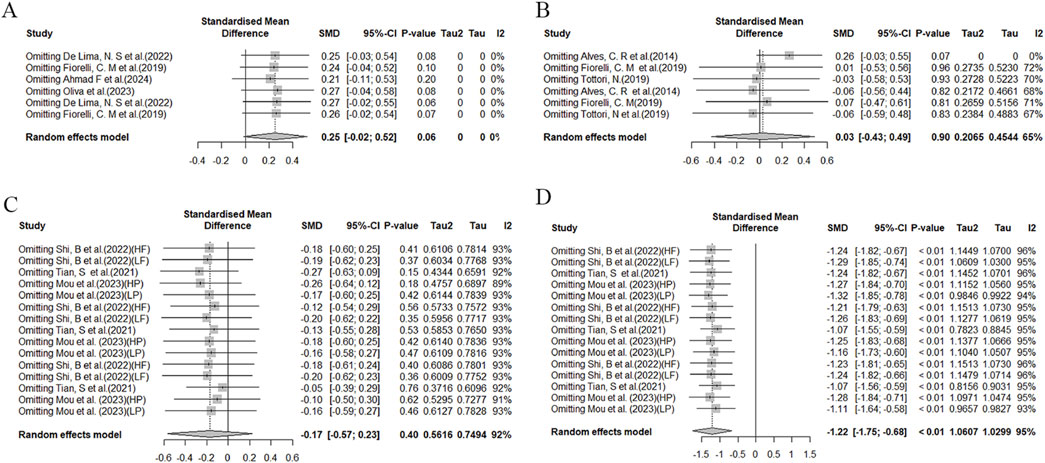

To assess the stability and reliability of the results obtained in this meta-analysis, a sensitivity analysis was conducted. Significantly heterogeneous findings were observed during functional assessments, specifically in the Stroop and TMT tests (Figure 8). This heterogeneity may be attributed to significant differences in factors such as age and training frequency among the study samples, as well as variations in experimental design methods. Specifically, in the Stroop test, differences were observed between the studies conducted by Tsukamoto, H (Tsukamoto et al., 2016) and Kujach, S (Kujach et al., 2018), which may have contributed to increased heterogeneity. In the case of the TMT test, the study conducted by Khandekar (Khandekar et al., 2023), P significantly differed from other studies, potentially contributing to increased heterogeneity.

Figure 8. Sensitivity analysis of the effects of HIIT on Stroop and TMT tests. (A) Comparison of HIIT and MICT in Stroop test results; (B) Comparison of HIIT and control in Stroop test; (C) Comparison of HIIT and MICT in TMT test; (D) Comparison of HIIT and control in TMT test.

Sensitivity analysis of the DST test (Figures 9A, B) reveals variability in effect sizes and observed heterogeneity across studies. In the MOST test (Figures 9C, D), we also observed high heterogeneity, which may stem from differences in experimental designs. For instance, Shi et al. (2022) employed a crossover design; Tian et al. (2021) utilized a within-subject repeated measures design.

Figure 9. Sensitivity analysis of the effects of HIIT on MOST and DST tests. (A) Comparison of HIIT and MICT in DST test; (B) Comparison of HIIT and control in DST test; (C) Comparison of HIIT and MICT in MOST test; (D) Comparison of HIIT and control in MOST test.

Therefore, these differences and potential sources of heterogeneity should be considered when interpreting these findings. Due to limitations in sample size and study design, further research is needed to accurately understand and explain the observed heterogeneity.

The present meta-analysis included 18 studies with a total of 827 patients. It compared the cognitive assessment results among the HIIT group, MICT group, and control group. We found that HIIT demonstrated better effects than MICT in the Stroop test (assessing attention control (Gignac et al., 2022) and inhibitory abilities (Chen et al., 2019; Daza González et al., 2021) and the DST test (assessing working memory (Sánchez-Cubillo et al., 2009; Llinàs-Reglà et al., 2017). Additionally, compared to the control group, HIIT showed significant effects in the TMT and MOST tests (evaluating cognitive flexibility (Tian et al., 2021; Shi et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2022b; Xia et al., 2022), working memory (Zhang et al., 2022b), and inhibitory control (Zhang et al., 2022b). Overall, our study supports the effectiveness of HIIT in improving specific cognitive functions, particularly cognitive flexibility, working memory, task-switching abilities, attention control, and inhibitory control.

This meta-analysis aimed to systematically evaluate the effects of High-Intensity Interval Training (HIIT) on cognitive function, with a focus on executive function, which includes key domains such as working memory, inhibitory control, and cognitive flexibility. Our findings suggest that HIIT has a significant effect on certain aspects of cognitive function, particularly in executive control, as evidenced by the Stroop Test results, where HIIT significantly reduced neural response time compared to moderate-intensity continuous training (MICT). However, the effects of HIIT on other aspects, such as incongruent response time, accuracy, and interference response time, were not significant, indicating that the impact of HIIT on cognitive function is not uniform across all domains.

To provide clarity on the effectiveness of HIIT, it is important to consider the specific characteristics of the HIIT protocols used in the studies included in this meta-analysis. Most studies implemented HIIT sessions with varying duration, frequency, intensity, and types of intervals, which could contribute to the heterogeneity observed in our results. For instance, some studies employed walking or cycling as the primary mode of exercise, while others used running or uphill exercises. The frequency of HIIT sessions ranged from two to five times per week, with session durations ranging from 20 to 45 min. These variations in protocol design may explain some of the differences in the observed effects on cognitive function across studies.

Our meta-analysis included studies involving a range of populations, including healthy adults, older adults, and individuals recovering from stroke. It is important to note that these populations may have different baseline cognitive function levels and responses to exercise. For example, studies involving older adults and stroke patients consistently demonstrated improvements in executive functions, such as inhibitory control and cognitive flexibility. These findings suggest that HIIT may be particularly beneficial for individuals with cognitive impairments or those at risk for cognitive decline.

Neuroplasticity: HIIT can significantly increase the levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) (Jiménez-Maldonado et al., 2018; Hsu et al., 2021) which triggers a cascade of signaling pathways by activating its specific cell surface receptor, tropomyosin receptor kinase B (TrkB) (Casarotto et al., 2021). Which plays a crucial role in cell survival, anti-apoptosis, and neuronal growth and differentiation (Jin et al., 2022; Goyal et al., 2023).

Secondly, BDNF, through binding with the TrkB receptor, activates the MAPK/ERK signaling pathway (Li et al., 2021; Numakawa et al., 2018). In this process, a series of protein kinases are phosphorylated and activated. Additionally, BDNF, by activating the TrkB receptor, can trigger the PLCγ (Phospholipase C-gamma) pathway (Mohammadi et al., 2018). Activation and interaction of these signaling pathways are orderly and closely connected, collectively regulating various biological processes of neurons.

Cerebral hemodynamics: HIIT can enhance cardio-pulmonary function (Lavín-Pérez et al., 2021; Licker et al., 2017; Bönhof et al., 2022) by increasing cardiac output and cerebral blood flow (Lucas et al., 2015; Smith et al., 2021). The augmented blood circulation not only supplies neurons with additional energy sources like glucose and oxygen but also aids in clearing metabolic waste products such as beta-amyloid protein (associated with Alzheimer’s disease), thus mitigating their accumulation and neurotoxicity in the brain (Kisler et al., 2017; Qiang et al., 2017; Li et al., 2019). Moreover, the improved cerebral blood flow facilitates neuronal metabolism, synthesis, and release of neurotransmitters, thereby enhancing interneuronal information transmission (Kisler et al., 2017).

Neurochemical responses: HIIT can influence various neurotransmitters in the brain, such as serotonin, dopamine, and endorphins, which play crucial roles in emotional regulation (Anish, 2005; Zárate et al., 2002), attention, memory, and learning processes (Unger et al., 2020; Thiele and Bellgrove, 2018; Westbrook et al., 2021; Schoenfeld and Swanson, 2021). HIIT modulates the synthesis and release of these neurotransmitters through diverse pathways. Firstly, by inducing a stress response, HIIT triggers the release of stress hormones such as adrenaline and cortisol, thereby regulating the synthesis and release of serotonin and dopamine (de Oliveira Teles et al., 2022). Secondly, HIIT improves cardiovascular fitness by increasing cardiac output and cerebral blood flow, thereby facilitating neurotransmitter synthesis and release (Sultana et al., 2019). In addition, HIIT can impact neuronal excitability, making neurons more susceptible to activation, thereby stimulating the generation and release of a greater quantity of neurotransmitters.

Antioxidant and inflammatory responses: HIIT enhances the body’s antioxidant capacity by stimulating the production of antioxidant enzymes which can reduce damage to neurons caused by free radicals (Gholipour et al., 2022; Freitas et al., 2019; Souza et al., 2022). HIIT strengthens antioxidant capacity through multiple pathways. Firstly, during HIIT, muscle contractions and energy metabolism are activated, which induces intracellular stress responses. This stress response stimulates the production of antioxidant enzymes such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), and glutathione peroxidase (Gpx) (Fakhri et al., 2020; Azhdari et al., 2019).

While the current evidence is promising, the lack of standardization in HIIT protocols and population characteristics makes it difficult to draw firm conclusions about the most effective implementation of HIIT for cognitive improvement. Future research should aim to determine the optimal duration, frequency, and intensity of HIIT for improving executive function, especially in at-risk populations such as older adults and stroke survivors.

In the studies included in this meta-analysis, interventions varied in terms of duration, frequency, intensity, type of intervals, and exercise modality. The HIIT protocols generally involved sessions lasting between 4 and 12 weeks, with frequencies ranging from 2 to 5 sessions per week. Exercise intensity during HIIT was typically 80%–90% of maximum heart rate, with short bursts of high-intensity exercise followed by brief recovery periods. In contrast, MICT involved continuous moderate-intensity exercise, such as walking or cycling, at 50%–70% of maximum heart rate. These interventions were typically designed to be accessible to individuals with varying levels of fitness, with walking and cycling being the most common exercise types. Understanding the specific design of these interventions helps in determining the most appropriate and effective approach for different populations, highlighting the need for tailored recommendations for implementing HIIT and MICT in clinical and rehabilitation settings.

Overall, compared to MICT and a sedentary lifestyle, HIIT may enhance cerebral blood flow dynamics and neuroplasticity more effectively, leading to better improvements in cognitive performance. This does not imply, however, the benefits of MICT and other forms of exercise on health and cognitive function should be discounted. While HIIT has shown cognitive benefits, it is important to consider the value of moderate-intensity continuous training (MICT) as well. Both types of exercise offer unique advantages, with HIIT being time-efficient and MICT providing sustained benefits. Including both in an exercise regimen allows for a more tailored approach, ensuring that individuals at different fitness levels can benefit from both cognitive and physical health improvements. Additionally, given the high intensity of HIIT, individuals performing HIIT should adjust the intensity and frequency of exercise under medical guidance to avoid the risks of overtraining or injury.

Due to potential variations in the design and quality of the included primary studies, heterogeneity within certain subgroups may have influenced our results. Additionally, the small number of included studies and the inclusion of diverse populations (including healthy individuals, cancer patients, Parkinson’s disease patients, stroke patients, etc.,) may limit the generalizability of our findings. Furthermore, we did not extensively explore the effects of various forms and frequencies of HIIT on cognitive function, which limits our comprehensive understanding of the effects of HIIT. Lastly, since the majority of the study participants were young individuals, we did not fully consider the impact of age on the study outcomes.

Our meta-analysis demonstrates that HIIT significantly enhances specific cognitive functions, particularly cognitive flexibility, working memory, task-switching ability, attention control, and inhibitory control. This finding underscores the potential value of HIIT in improving specific cognitive tasks. Therefore, we recommend healthcare professionals consider incorporating HIIT into training programs when developing exercise plans. In the future, further high-quality research is needed to clarify the optimal patterns and frequencies of HIIT, as well as its applicability in different populations, thereby providing more comprehensive guidance for clinical and practical applications.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

WZ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing. SZ: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing. YN: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing–original draft. KX: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Writing–original draft. QZ: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Writing–review and editing. YQ: Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Writing–review and editing. YL: Conceptualization, Supervision, Validation, Writing–review and editing.

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the 2023 Graduate Research and Practice Plan Innovation Project (KYCX23_2367).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Ahmad F., Zahra M., Zoofeen U., Shah Z., Mahmood A., Afridi A., et al. (2024). ENHancing selective attention: a comparative study of moderate-intensity exercise and high-intensity interval exercise in young adults. 32, 255–259. doi:10.52764/jms.24.32.3.9

Alves C. R., Tessaro V. H., Teixeira L. A. C., Murakava K., Roschel H., Gualano B., et al. (2014). Influence of acute high-intensity aerobic interval exercise bout on selective attention and short-term memory tasks. Percept. Mot. Ski. 118, 63–72. doi:10.2466/22.06.PMS.118k10w4

Anish E. J. (2005). Exercise and its effects on the central nervous system. Curr. sports Med. Rep. 4, 18–23. doi:10.1097/01.csmr.0000306066.14026.77

Azhdari A., Hosseini S. A., Farsi S. (2019). Antioxidant effect of high intensity interval training on cadmium-induced cardiotoxicity in rats. J. Gene, Cell Tissue 6. doi:10.5812/gct.94671

Billat L. V. (2001). Interval training for performance: a scientific and empirical practice. Special recommendations for middle- and long-distance running. Part I: aerobic interval training. Sports Med. Auckl. N.Z. 31, 13–31. doi:10.2165/00007256-200131010-00002

Bönhof G. J., Strom A., Apostolopoulou M., Karusheva Y., Sarabhai T., Pesta D., et al. (2022). High-intensity interval training for 12 weeks improves cardiovascular autonomic function but not somatosensory nerve function and structure in overweight men with type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia 65, 1048–1057. doi:10.1007/s00125-022-05674-w

Calverley T. A., Ogoh S., Marley C. J., Steggall M., Marchi N., Brassard P., et al. (2020). HIITing the brain with exercise: mechanisms, consequences and practical recommendations. J. physiology 598, 2513–2530. doi:10.1113/jp275021

Casarotto P. C., Girych M., Fred S. M., Kovaleva V., Moliner R., Enkavi G., et al. (2021). Antidepressant drugs act by directly binding to TRKB neurotrophin receptors. Cell 184, 1299–1313.e19. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2021.01.034

Chen Y., Huang X., Wu M., Li K., Hu X., Jiang P., et al. (2019). Disrupted brain functional networks in drug-naïve children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder assessed using graph theory analysis. Hum. Brain Mapp. 40, 4877–4887. doi:10.1002/hbm.24743

Coetsee C., Terblanche E. (2017). The effect of three different exercise training modalities on cognitive and physical function in a healthy older population. Eur. Rev. aging Phys. activity official J. Eur. Group Res. into Elder. Phys. Activity 14, 13. doi:10.1186/s11556-017-0183-5

Cuddy T. F., Ramos J. S., Dalleck L. C. (2019). Reduced exertion high-intensity interval training is more effective at improving cardiorespiratory fitness and cardiometabolic health than traditional moderate-intensity continuous training. Int. J. Environ. Res. public health 16, 483. doi:10.3390/ijerph16030483

Daza González M. T., Phillips-Silver J., López Liria R., Gioiosa Maurno N., Fernández García L., Ruiz-Castañeda P. (2021). Inattention, impulsivity, and hyperactivity in deaf children are not due to deficits in inhibitory control, but may reflect an adaptive strategy. Front. Psychol. 12, 629032. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.629032

de Lima N. S., De Sousa R. A. L., Amorim F. T., Gripp F., Diniz E Magalhães C. O., Henrique Pinto S., et al. (2022). Moderate-intensity continuous training and high-intensity interval training improve cognition, and BDNF levels of middle-aged overweight men. Metab. Brain Dis. 37, 463–471. doi:10.1007/s11011-021-00859-5

de Oliveira Teles G., da Silva C. S., Rezende V. R., Rebelo A. C. S. (2022). Acute effects of high-intensity interval training on diabetes mellitus: a systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. public health 19, 7049. doi:10.3390/ijerph19127049

D'Onofrio G., Kirschner J., Prather H., Goldman D., Rozanski A. (2023). Musculoskeletal exercise: its role in promoting health and longevity. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 77, 25–36. doi:10.1016/j.pcad.2023.02.006

Drollette E. S., Meadows C. C. (2022). The effects of acute high-intensity interval exercise on the temporal dynamics of working memory and contralateral delay activity. Psychophysiology 59, e14112. doi:10.1111/psyp.14112

Fakhri S., Shakeryan S., Alizadeh A., Shahryari A. (2020). Effect of 6 weeks of high intensity interval training with nano curcumin supplement on antioxidant defense and lipid peroxidation in overweight girls-clinical trial. Iran. J. diabetes Obes. doi:10.18502/ijdo.v11i3.2606

Fiorelli C. M., Ciolac E. G., Simieli L., Silva F. A., Fernandes B., Christofoletti G., et al. (2019). Differential acute effect of high-intensity interval or continuous moderate exercise on cognition in individuals with Parkinson's disease. J. Phys. activity and health 16, 157–164. doi:10.1123/jpah.2018-0189

Fiuza-Luces C., Santos-Lozano A., Joyner M., Carrera-Bastos P., Picazo O., Zugaza J. L., et al. (2018). Exercise benefits in cardiovascular disease: beyond attenuation of traditional risk factors. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 15, 731–743. doi:10.1038/s41569-018-0065-1

Freitas D. A., Rocha-Vieira E., De Sousa R. A. L., Soares B. A., Rocha-Gomes A., Chaves Garcia B. C., et al. (2019). High-intensity interval training improves cerebellar antioxidant capacity without affecting cognitive functions in rats. Behav. Brain Res. 376, 112181. doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2019.112181

Gholipour P., Komaki A., Ramezani M., Parsa H. (2022). Effects of the combination of high-intensity interval training and Ecdysterone on learning and memory abilities, antioxidant enzyme activities, and neuronal population in an Amyloid-beta-induced rat model of Alzheimer's disease. Physiology and Behav. 251, 113817. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2022.113817

Gignac F., Righi V., Toran R., Paz Errandonea L., Ortiz R., Mijling B., et al. (2022). Short-term NO(2) exposure and cognitive and mental health: a panel study based on a citizen science project in Barcelona, Spain. Environ. Int. 164, 107284. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2022.107284

Gjellesvik T. I., Becker F., Tjønna A. E., Indredavik B., Lundgaard E., Solbakken H., et al. (2021). Effects of high-intensity interval training after stroke (the HIIT stroke study) on physical and cognitive function: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Archives Phys. Med. rehabilitation 102, 1683–1691. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2021.05.008

Goyal A., Agrawal A., Verma A., Dubey N. (2023). The PI3K-AKT pathway: a plausible therapeutic target in Parkinson's disease. Exp. Mol. pathology 129, 104846. doi:10.1016/j.yexmp.2022.104846

Hertzog C., Kramer A. F., Wilson R. S., Lindenberger U. (2008). Enrichment effects on adult cognitive development: can the functional capacity of older adults Be preserved and enhanced? Psychol. Sci. public interest a J. Am. Psychol. Soc. 9, 1–65. doi:10.1111/j.1539-6053.2009.01034.x

Higgins J. P., Thomas J., Chandler J., Cumpston M., Li T., Page M. J., et al. (2019). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions.

Higgins J. P., Thompson S. G., Deeks J. J., Altman D. G. (2003). Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ Clin. Res. ed. 327, 557–560. doi:10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557

Hsu C. C., Fu T. C., Huang S. C., Chen C. P., Wang J. S. (2021). Increased serum brain-derived neurotrophic factor with high-intensity interval training in stroke patients: a randomized controlled trial. Ann. Phys. rehabilitation Med. 64, 101385. doi:10.1016/j.rehab.2020.03.010

Hugues N., Pellegrino C., Rivera C., Berton E., Pin-Barre C., Laurin J. (2021). Is high-intensity interval training suitable to promote neuroplasticity and cognitive functions after stroke? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 3003. doi:10.3390/ijms22063003

Jiménez-Maldonado A., Rentería I., García-Suárez P. C., Moncada-Jiménez J., Freire-Royes L. F. (2018). The impact of high-intensity interval training on brain derived neurotrophic factor in brain: a mini-review. Front. Neurosci. 12, 839. doi:10.3389/fnins.2018.00839

Jin T., Zhang Y., Botchway B. O. A., Zhang J., Fan R., Zhang Y., et al. (2022). Curcumin can improve Parkinson's disease via activating BDNF/PI3k/Akt signaling pathways. Food Chem. Toxicol. Int. J. Publ. Br. Industrial Biol. Res. Assoc. 164, 113091. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2022.113091

Khandekar P., Shenoy S., Sathe A. (2023). Prefrontal cortex hemodynamic response to acute high intensity intermittent exercise during executive function processing. J. general Psychol. 150, 295–322. doi:10.1080/00221309.2022.2048785

Kisler K., Nelson A. R., Montagne A., Zlokovic B. V. (2017). Cerebral blood flow regulation and neurovascular dysfunction in Alzheimer disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 18, 419–434. doi:10.1038/nrn.2017.48

Kujach S., Byun K., Hyodo K., Suwabe K., Fukuie T., Laskowski R., et al. (2018). A transferable high-intensity intermittent exercise improves executive performance in association with dorsolateral prefrontal activation in young adults. NeuroImage 169, 117–125. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.12.003

LaCount P. A., Hartung C. M., Vasko J. M., Serrano J. W., Wright H. A., Smith D. T. (2022). Acute effects of physical exercise on cognitive and psychological functioning in college students with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Ment. health Phys. activity 22, 100443. doi:10.1016/j.mhpa.2022.100443

Lavín-Pérez A. M., Collado-Mateo D., Mayo X., Humphreys L., Liguori G., James Copeland R., et al. (2021). High-intensity exercise to improve cardiorespiratory fitness in cancer patients and survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Scand. J. Med. and Sci. sports 31, 265–294. doi:10.1111/sms.13861

Lee J. S., Boafo A., Greenham S., Longmuir P. E. (2019). The effect of high-intensity interval training on inhibitory control in adolescents hospitalized for a mental illness. J. Ment. Health Phys. Act. 17, 100298. doi:10.1016/j.mhpa.2019.100298

Li B., Liang F., Ding X., Yan Q., Zhao Y., Zhang X., et al. (2019). Interval and continuous exercise overcome memory deficits related to β-Amyloid accumulation through modulating mitochondrial dynamics. Behav. Brain Res. 376, 112171. doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2019.112171

Li C., Sui C., Wang W., Yan J., Deng N., Du X., et al. (2021). Baicalin attenuates oxygen-glucose deprivation/reoxygenation-induced injury by modulating the BDNF-TrkB/PI3K/akt and MAPK/Erk1/2 signaling axes in neuron-astrocyte cocultures. Front. Pharmacol. 12, 599543. doi:10.3389/fphar.2021.599543

Liberati A., Altman D. G., Tetzlaff J., Mulrow C., Gøtzsche P. C., Ioannidis J. P. A., et al. (2009). The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ Clin. Res. ed. 339, b2700. doi:10.1136/bmj.b2700

Licker M., Karenovics W., Diaper J., Frésard I., Triponez F., Ellenberger C., et al. (2017). Short-term preoperative high-intensity interval training in patients awaiting lung cancer surgery: a randomized controlled trial. J. Thorac. Oncol. official Publ. Int. Assoc. Study Lung Cancer 12, 323–333. doi:10.1016/j.jtho.2016.09.125

Llinàs-Reglà J., Vilalta-Franch J., López-Pousa S., Calvó-Perxas L., Torrents Rodas D., Garre-Olmo J. (2017). The Trail making test. Assessment 24, 183–196. doi:10.1177/1073191115602552

Lucas S. J., Cotter J. D., Brassard P., Bailey D. M. (2015). High-intensity interval exercise and cerebrovascular health: curiosity, cause, and consequence. J. Cereb. blood flow metabolism official J. Int. Soc. Cereb. Blood Flow Metabolism 35, 902–911. doi:10.1038/jcbfm.2015.49

Mandolesi L., Polverino A., Montuori S., Foti F., Ferraioli G., Sorrentino P., et al. (2018). Effects of physical exercise on cognitive functioning and wellbeing: biological and psychological benefits. Front. Psychol. 9, 509. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00509

Mekari S., Earle M., Martins R., Drisdelle S., Killen M., Bouffard-Levasseur V., et al. (2020). Effect of high intensity interval training compared to continuous training on cognitive performance in young healthy adults: a pilot study. Brain Sci. 10, 81. doi:10.3390/brainsci10020081

Mohammadi A., Amooeian V. G., Rashidi E. (2018). Dysfunction in brain-derived neurotrophic factor signaling pathway and susceptibility to schizophrenia, Parkinson's and Alzheimer's diseases. Curr. gene Ther. 18, 45–63. doi:10.2174/1566523218666180302163029

Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D. G.PRISMA Group (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ Clin. Res. ed. 339, b2535. doi:10.1136/bmj.b2535

Mou H., Tian S., Yuan Y., Sun D., Qiu F. (2023). Effect of acute exercise on cognitive flexibility: role of baseline cognitive performance. Ment. Health Phys. Act. 25, 100522. doi:10.1016/j.mhpa.2023.100522

Nguyen L., Murphy K., Andrews G. (2019). Cognitive and neural plasticity in old age: a systematic review of evidence from executive functions cognitive training. Ageing Res. Rev. 53, 100912. doi:10.1016/j.arr.2019.100912

Numakawa T., Odaka H., Adachi N. (2018). Actions of brain-derived neurotrophin factor in the neurogenesis and neuronal function, and its involvement in the pathophysiology of brain diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19, 3650. doi:10.3390/ijms19113650

Oliva H. N. P., Oliveira G. M., Oliva I. O., Cassilhas R. C., de Paula A. M. B., Monteiro-Junior R. S. (2023). Middle cerebral artery blood velocity and cognitive function after high- and moderate-intensity aerobic exercise sessions. Neurosci. Lett. 817, 137511. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2023.137511

Piraux E., Caty G., Renard L., Vancraeynest D., Tombal B., Geets X., et al. (2021). Effects of high-intensity interval training compared with resistance training in prostate cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy: a randomized controlled trial. Prostate cancer prostatic Dis. 24, 156–165. doi:10.1038/s41391-020-0259-6

Poon E. T., Wongpipit W., Sun F., Tse A. C., Sit C. H. (2023). High-intensity interval training in children and adolescents with special educational needs: a systematic review and narrative synthesis. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. activity 20, 13. doi:10.1186/s12966-023-01421-5

Qiang W., Yau W. M., Lu J. X., Collinge J., Tycko R. (2017). Structural variation in amyloid-β fibrils from Alzheimer's disease clinical subtypes. Nature 541, 217–221. doi:10.1038/nature20814

Reindell H., Roskamm H., Gerschler W., Adam K., Braecklein H., Keul J., et al. (1962). Das intervalltraining: physiologische Grundlagen, praktische Anwendungen und Schädigungsmöglichkeiten.

Reindell H., Roskamm H. (1959). Ein Beitrag zu den physiologischen Grundlagen des Intervalltrainings unter besonderer Berücksichtigung des Kreislaufes. Geneva, Switzerland: Editions Médecine et Hygiène.

Sánchez-Cubillo I., Periáñez J. A., Adrover-Roig D., Rodríguez-Sánchez J. M., Ríos-Lago M., Tirapu J., et al. (2009). Construct validity of the Trail Making Test: role of task-switching, working memory, inhibition/interference control, and visuomotor abilities. J. Int. Neuropsychological Soc. JINS 15, 438–450. doi:10.1017/s1355617709090626

Schoenfeld T. J., Swanson C. (2021). A runner's high for new neurons? Potential role for endorphins in exercise effects on adult neurogenesis. Biomolecules 11, 1077. doi:10.3390/biom11081077

Sellami M., Bragazzi N. L., Aboghaba B., Elrayess M. A. (2021). The impact of acute and chronic exercise on immunoglobulins and cytokines in elderly: insights from a critical review of the literature. Front. Immunol. 12, 631873. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2021.631873

Shi B., Mou H., Tian S., Meng F., Qiu F. (2022). Effects of acute exercise on cognitive flexibility in young adults with different levels of aerobic fitness. Int. J. Environ. Res. public health 19, 9106. doi:10.3390/ijerph19159106

Smith E. C., Pizzey F. K., Askew C. D., Mielke G. I., Ainslie P. N., Coombes J. S., et al. (2021). Effects of cardiorespiratory fitness and exercise training on cerebrovascular blood flow and reactivity: a systematic review with meta-analyses. Am. J. physiology. Heart circulatory physiology 321, H59–h76. doi:10.1152/ajpheart.00880.2020

Sokołowski D. R., Hansen T. I., Rise H. H., Reitlo L. S., Wisløff U., Stensvold D., et al. (2021). 5 Years of exercise intervention did not benefit cognition compared to the physical activity guidelines in older adults, but higher cardiorespiratory fitness did. A generation 100 substudy. Front. aging Neurosci. 13, 742587. doi:10.3389/fnagi.2021.742587

Souza J., da Silva R. A., da Luz Scheffer D., Penteado R., Solano A., Barros L., et al. (2022). Physical-exercise-Induced antioxidant effects on the brain and skeletal muscle. Antioxidants Basel, Switz. 11, 826. doi:10.3390/antiox11050826

Stensvold D., Viken H., Steinshamn S. L., Dalen H., Støylen A., Loennechen J. P., et al. (2020). Effect of exercise training for five years on all cause mortality in older adults-the Generation 100 study: randomised controlled trial. BMJ Clin. Res. ed. 371, m3485. doi:10.1136/bmj.m3485

Stillman C. M., Esteban-Cornejo I., Brown B., Bender C. M., Erickson K. I. (2020). Effects of exercise on brain and cognition across age groups and health states. Trends Neurosci. 43, 533–543. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2020.04.010

Sultana R. N., Sabag A., Keating S. E., Johnson N. A. (2019). The effect of low-volume high-intensity interval training on body composition and cardiorespiratory fitness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. Auckl. N.Z. 49, 1687–1721. doi:10.1007/s40279-019-01167-w

Taylor J. L., Holland D. J., Keating S. E., Leveritt M. D., Gomersall S. R., Rowlands A. V., et al. (2020). Short-term and long-term feasibility, safety, and efficacy of high-intensity interval training in cardiac rehabilitation: the FITR heart study randomized clinical trial. JAMA Cardiol. 5, 1382–1389. doi:10.1001/jamacardio.2020.3511

Thiele A., Bellgrove M. A. (2018). Neuromodulation of attention. Neuron 97, 769–785. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2018.01.008

Tian S., Mou H., Fang Q., Zhang X., Meng F., Qiu F. (2021). Comparison of the sustainability effects of high-intensity interval exercise and moderate-intensity continuous exercise on cognitive flexibility. Int. J. Environ. Res. public health 18, 9631. doi:10.3390/ijerph18189631

Tottori N., Morita N., Ueta K., Fujita S. (2019). Effects of high intensity interval training on executive function in children aged 8-12 years. Int. J. Environ. Res. public health 16, 4127. doi:10.3390/ijerph16214127

Tsukamoto H., Suga T., Takenaka S., Tanaka D., Takeuchi T., Hamaoka T., et al. (2016). Greater impact of acute high-intensity interval exercise on post-exercise executive function compared to moderate-intensity continuous exercise. Physiology and Behav. 155, 224–230. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2015.12.021

Unger E. K., Keller J. P., Altermatt M., Liang R., Matsui A., Dong C., et al. (2020). Directed evolution of a selective and sensitive serotonin sensor via machine learning. Cell 183, 1986–2002.e26. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2020.11.040

Westbrook A., Frank M. J., Cools R. (2021). A mosaic of cost-benefit control over cortico-striatal circuitry. Trends cognitive Sci. 25, 710–721. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2021.04.007

Wewege M. A., Ahn D., Yu J., Liou K., Keech A. (2018). High-intensity interval training for patients with cardiovascular disease-is it safe? A systematic review. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 7, e009305. doi:10.1161/jaha.118.009305

Xia T., An Y., Guo J. (2022). Bilingualism and creativity: benefits from cognitive inhibition and cognitive flexibility. Front. Psychol. 13, 1016777. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1016777

Zárate A., Fonseca E., Ochoa R., Basurto L., Hernández M. (2002). Low-dose conjugated equine estrogens elevate circulating neurotransmitters and improve the psychological well-being of menopausal women. Fertil. Steril. 77, 952–955. doi:10.1016/s0015-0282(02)03077-7

Zhang F., Yin X., Liu Y., Li M., Gui X., Bi C. (2022b). Association between sugar-sweetened beverage consumption and executive function among Chinese Tibetan adolescents at high altitude. Front. Nutr. 9, 939256. doi:10.3389/fnut.2022.939256

Keywords: high-intensity interval training, cognitive function, moderateintensity continuous training, exercise, cognitive flexibility, attention

Citation: Zhang W, Zeng S, Nie Y, Xu K, Zhang Q, Qiu Y and Li Y (2025) Meta-analysis of high-intensity interval training effects on cognitive function in older adults and cognitively impaired patients. Front. Physiol. 16:1543217. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2025.1543217

Received: 15 December 2024; Accepted: 17 February 2025;

Published: 06 March 2025.

Edited by:

Giuseppe Longo, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS), FranceReviewed by:

Jérôme Laurin, Aix-Marseille Université, FranceCopyright © 2025 Zhang, Zeng, Nie, Xu, Zhang, Qiu and Li. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yongqiang Li, bGl5b25ncWlhbmduam11QG91dGxvb2suY29t

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.