95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Physiol. , 13 January 2025

Sec. Exercise Physiology

Volume 15 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2024.1496243

This article is part of the Research Topic Biomechanical Performance and Relevant Mechanism of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation for Neuromusculoskeletal Disorders, Volume II View all 13 articles

Background: Vocal therapy, such as singing training, is an increasingly popular pulmonary rehabilitation program that has improved respiratory muscle status in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). However, variations in singing treatment protocols have led to inconsistent clinical outcomes.

Objective: This study aims to explore the content of vocalization training for patients with COPD by observing differences in respiratory muscle activation across different vocalization tasks.

Methods: All participants underwent measurement of surface electromyography (sEMG) activity from the sternocleidomastoid (SCM), parasternal intercostal muscle (PARA), seventh intercostal muscle (7thIC), and rectus abdominis (RA) during the production of the vowels/a/,/i/, and/u/at varying pitches (comfortable, +6 semitones) and loudness (−10 dB, +10 dB) levels. The Visual Analog Scale (VAS) was used to evaluate the condition of patients concerning vocalization, while the Borg-CR10 breathlessness scale was utilized to gauge the level of dyspnea following the task. Repeated-measure (RM) ANOVA was utilized to analyze the EMG data of respiratory muscles and the Borg scale across different tasks.

Results: Forty-one patients completed the experiment. Neural respiratory drive (NRD) in the SCM muscle did not significantly increase at high loudness levels (VAS 7-8) compared with that at low loudness levels (F (2, 120) = 1.548, P = 0.276). However, NRD in the PARA muscle (F (2, 120) = 55.27, P< 0.001), the 7thIC muscle (F (2, 120) = 59.08, P < 0.001), and the RA muscle (F (2, 120) = 39.56, P < 0.001) were significantly higher at high loudness compared with that at low loudness (VAS 2-3). Intercostal and abdominal muscle activation states were negatively correlated with maximal expiratory pressure (r = −0.671, P < 0.001) and inspiratory pressure (r = −0.571, P < 0.001) in the same loudness.

Conclusion: In contrast to pitch or vowel, vocal loudness emerges as a critical factor for vocalization training in patients with COPD. Higher pitch and loudness produced more dyspnea than lower pitch and loudness. In addition, maximal expiratory/inspiratory pressure was negatively correlated with respiratory muscle NRD in the same loudness vocalization task.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a heterogeneous lung condition characterized by chronic respiratory symptoms (dyspnea, cough, sputum production, and/or exacerbations) due to abnormalities of the airways and/or alveoli that cause persistent airflow obstruction (Celli et al., 2022). According to the estimation of large-scale epidemiology research, the global epidemic rate of COPD is 10.3% [95% confidence interval (CI) = 8.2%–12.8%], with the progress of the global population aging, the prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease will continue to increase (Adeloye et al., 2022; Adeloye et al., 2015). Although pulmonary damage in COPD is permanent, symptoms, such as respiratory muscle weakness and dyspnea, can be improved through pulmonary rehabilitation (Nolan et al., 2022).

Vocalization, such as singing, as a pulmonary rehabilitation program can combine specific abdominal respiratory patterns with respiratory muscle training to provide positive expiratory pressure and improve lung dynamic suction (O'Donnell and Webb, 2008; Kaasgaard et al., 2022; McNamara et al., 2017). Vocalization training can enhance exhalation muscle strength and FEV1 in patients with COPD(McNamara et al., 2017; Bonilha et al., 2009). However, variations in vocalization treatment protocols have led to inconsistent clinical outcomes (Lord et al., 2012). Developing and applying effective vocalization mechanisms face challenges, including lack of consistent research content and a standardized vocalization protocol (Fang et al., 2022).

In addition, studies have shown significant differences in subglottal pressure during the vocalization of different vowels, suggesting that vowels may produce different afterloads in respiratory muscles (Pettersen, 2005). On the other hand, the activation of respiratory muscles varies with different loudness and pitch vocalization levels (Wang and Yiu, 2023). Hence, pitch, loudness, and vowels may be the main factors that contribute to differences in respiratory muscle activation during vocal content (Higgins, Netsell, and Schulte, 1998). In addition, unlike relaxed, natural expiration, vocalization requires the coordination of expiratory muscles and tends to cause dyspnea (Pettersen and Westgaard, 2004). Respiratory muscles, such as abdominal muscles, are the driving force for the power of vocalization. Although it is usually considered an inspiratory muscle, SCM is activated during speech (Wang and Yiu, 2023). Neural respiratory drive (NRD) measured by surface electromyography (sEMG) is a noninvasive measure of respiratory muscle activation that can be used in studies of physiologic mechanisms of respiratory muscles (Lin et al., 2019; Suh et al., 2020; AbuNurah, Russell, and Lowman, 2020).

Understanding the NRD of respiratory muscles in different vocalization tasks helps develop vocalization training programs for patients with COPD (Jolley et al., 2015; Pozzi et al., 2022). We aimed to 1) monitor the NRD of the SCM, PARA, 7thIC, and RA during various vocalization tasks by using sEMG; 2) evaluate the dyspnea index across different vocalization tasks; and 3) identify factors associated with respiratory muscle activation. We hypothesized that target muscles are more activated at high pitch and loudness and show different activity levels in vowel control tasks.

From April 2023 to June 2023, we conducted a non-blind observational study in Qingdao, China. This study was registered at ChinaTrials.gov under the identifier ChiCTR2100052874 and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Qingdao Municipal Hospital. We posted the COPD pulmonary rehabilitation poster in several medical facilities to recruit participants. We screened other patients referred to outpatient clinics for pulmonary rehabilitation to determine their eligibility. The observation experiment occurred after formal recruitment in the intervention study, during their pulmonary rehabilitation sessions. Before participation, all patients were provided informed consent by signing a written document confirming their complete understanding of the study’s purpose, procedures, and potential risks or benefits. The inclusion criteria for study patients encompassed a diagnosis of COPD based on the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD), willingness to participate in the group, and normal vocal function. Patients with unstable heart diseases or severe cognitive impairment were excluded from the study.

After instructing patients in vocal techniques (pitch and loudness), the vowels of /a/,/i/, and/u/were assessed at varying pitch and loudness levels through a visual analog scale (VAS). Task1: To observe different vocal pitches, patients were instructed to relax their whole body and pronounce /a/,/i/, and/u/at low (VAS 2-3) and high pitches (VAS 7-8) with the same loudness (Bane et al., 2023; Awan et al., 2013; Awan et al., 2012). Task 2: To observe different vocal loudness, patients were instructed to pronounce /a/,/i/, and/u/at low (VAS 2-3) and high loudness (VAS 7-8) with the same pitches. Task 3: The same vocalization loudness of 60 dB was selected, and the patient was instructed to continue for more than 5 s to reach the tension-time threshold. The visual feedback interface displays real-time loudness. The patients had rest time between tasks and communicate fully to one another to ensure that patients are relaxed before pronouncing. The Borg-CR10 breathlessness scale was used to assess the degree of dyspnea of the patients after each cycle of /a/,/i/,/u/. Two tasks were carried out at different periods, and the patients were assured of adequate rest before each task. A decibel meter measured at least 15 dB between low and high levels for accurate loudness difference. To assess different pitches, the patients initially produced a comfortable pitch while maintaining a comfortable loudness and then shifted to a higher base pitch (at least +5 semitones) while monitoring the pitch by using online tuning software (Wang and Yiu, 2023). Throughout the process, the voice was required to maintain a stable loudness and pitches and measured approximately 20 cm away from the participant. Data acquisition concluded when the voice reached a weak level (decrease of more than 5 dB or 2 semitones).

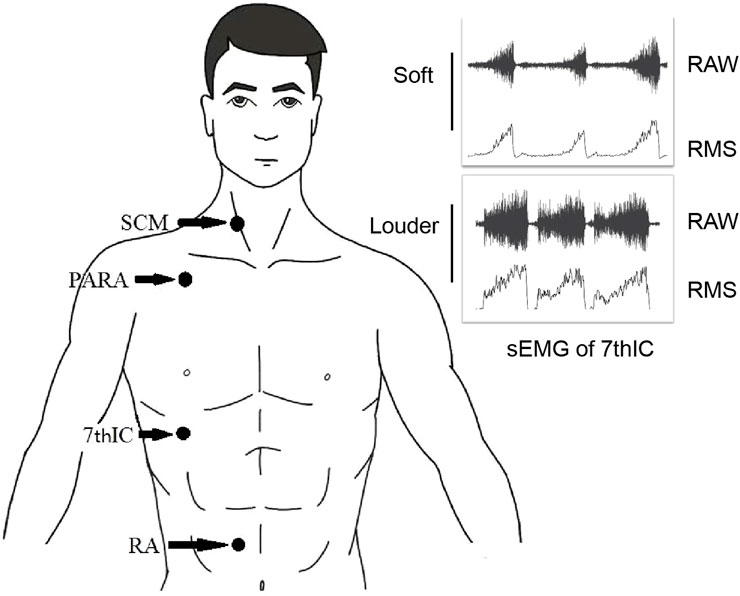

The Delsys Trigno™ wireless system (Delsys, Natick, MA) and four attached electrodes captured EMG signals at a sampling rate of 2,000 Hz. Wireless electrodes were placed at specific anatomical locations to ensure accurate measurements: the middle and lower 1/3 of the SCM, the junction of the PARA, the 7thIC, and 3 cm above the umbilicus in the position of the RA (Figure 1). Before electrode placement, the skin was meticulously cleaned with a medical alcohol pad to ensure optimal signal acquisition (Liu et al., 2019; da Fonsêca et al., 2019; Cabral et al., 2018). All surface EMG electrodes were positioned on the right side of the body for consistency (Ramsook et al., 2016). After data acquisition, all sEMG signals were analyzed using EMG works analysis software (Delsys, Natick). The sEMG signals recorded were filtered by a 20–450 Hz band-pass Butterworth filter. The signals were then segmented using a root-mean-square (RMS) value calculated based on a 100 ms moving window (Stepp, 2012) (Figure 1). The sEMG signal was calibrated as a percentage of the sEMG signal at maximum voluntary contraction (MVC) (Nguyen et al., 2020). NRD was used to represent RMS%MVC. During the performance of the MVC task, the subjects were instructed to exert their best effort by conducting three maximum breath tests (Cabral et al., 2018).

Figure 1. Electrode position and sEMG signals processing. Abbreviations: SCM, sternocleidomastoid; PARA, parasternal intercostal muscle; 7thIC, seventh intercostal muscle; RA, rectus abdominis; RAW, raw surface electromyographic signal; RMS, root-mean-square of surface electromyographic signal.

Statistical analysis used SPSS software v26.0 and GraphPad Prism v9.5.1. Data with normal distribution were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD), while data with a skewed distribution were expressed as median ± interquartile range (IQR). Repeated-measures analysis of variance (RM-ANOVA) was utilized to analyze the EMG data of respiratory muscles and Borg scale across different tasks. Correlation analysis was conducted using Pearson correlation. A 95% confidence interval was established, and the significance level was set at 0.05.

Forty-eight patients who met the criteria were recruited and trained; five were excluded because they could not maintain pitch or loudness, and two were excluded because they could not support sound. Finally, forty-one patients successfully concluded the experiment. No adverse events occurred during the experiment. Demographic and anthropometric data of patents with COPD patients who underwent voice tasks are shown in Table 1.

We found no difference at the NRD of SCM (F (2, 120) = 0.116, P = 0.890), PARA (F (2, 120) = 0.034, P = 0.967), 7thIC (F (2, 120) = 0.755, P = 0.473), and RA (F (2, 120) = 0.019, P = 0.982) during the high pitches task compared with the low pitch task (Table 2).

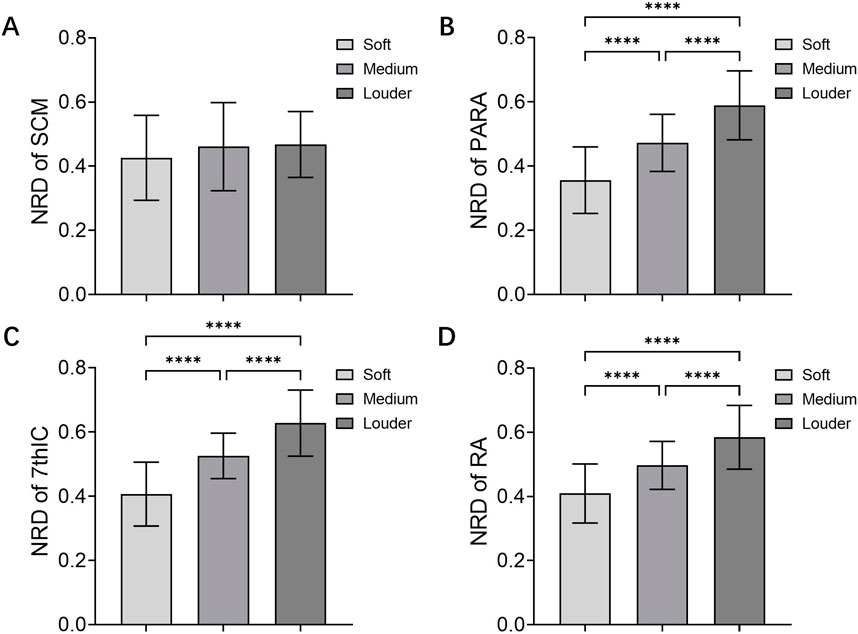

The study showed no significantly higher NRD in patients with high loudness compared to those with low loudness in SCM (F (2, 120) = 1.300, P = 0.276) (Figure 2A). Furthermore, COPD patients with high loudness exhibited significantly higher NRD in the PARA (F (2, 120) = 55.27, P < 0.001) (Figure 2B), 7thIC (F (2, 120) = 59.08, P < 0.001) (Figure 2C), and RA (F (2, 120) = 39.56, P < 0.001) (Figure 2D) when compared to those with low loudness.

Figure 2. NRD of Muscles in loudness control. NRD of (A) SCM, (B) PARA, (C) 7thIC, and (D) RA during soft and louder loudness. Abbreviations: NRD, neural respiratory drive; SCM, sternocleidomastoid; PARA, parasternal intercostal muscle; 7thIC, seventh intercostal muscle; RA, rectus abdominis; ****P < 0.001.

No differences in NRD were found for SCM (F (2, 120) = 0.309, P = 0.735), PARA (F (2, 120) = 0.058, P = 0.944), 7thIC (F (2, 120) = 0.051, P = 0.944), and RA (F (2, 120) = 2.128, P = 0.124) across vowel tasks (Table 2).

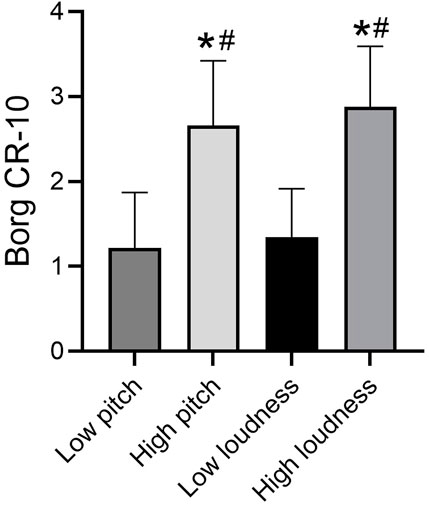

Borg dyspnea scores significantly differed across tasks [F (3, 160) = 66.47, P< 0.001]. We found no statistically significant difference in Borg dyspnea scores under low pitch and low loudness. The difference between Borg dyspnea scores under the high sound task was not statistically significant. However, Borg dyspnea scores were significantly higher after the high-loudness task than after the low-loudness task (P< 0.001) and after the low-pitched task (P< 0.001). Borg dyspnea scores were also significantly higher after the high-pitched task than after the low-loudness task (P< 0.001) and after the low-pitched task (P< 0.001) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Borg breathlessness score in different tasks. Note: *compare with low loudness P < 0.05, #compare with High loudness P < 0.05.

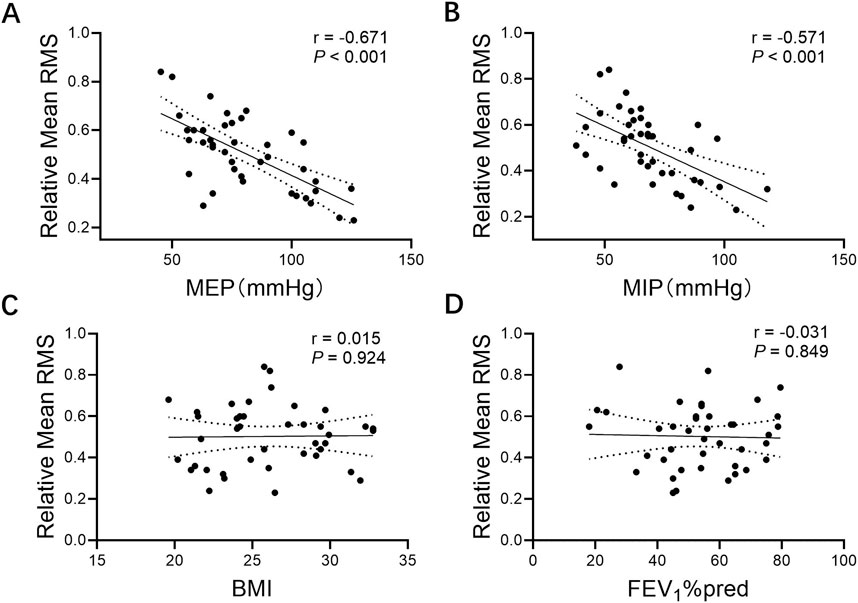

Correlation analysis of expiratory muscle RMS measured after harmonization of pitch with baseline patient data showed that loudness was unrelated to baseline patient status. However, the RMS of the loudness control task was significantly negatively correlated with MEP (r = −0.671, P < 0.001) and MIP (r = −0.571, P < 0.001). Higher respiratory muscle strength was associated with lower RMS (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Correlations between relative mean RMS and (A) MEP, (B) MIP, (C) BMI, and (D) FEV1%pred. Note: Relative mean RMS, mean respiratory muscle RMS% MVC of parasternal intercostal muscle, seventh intercostal muscle, rectus abdominis; MEP, maximal expiratory pressure; MIP, maximal inspiratory pressure; BMI, body mass index; FEV1%pred, forced expiratory volume in one second % predicted.

Vocalization, such as singing training, can enhance expiratory muscle strength and improve lung function in patients with COPD (McNamara et al., 2017; Bonilha et al., 2009). However, its clinical effectiveness remains inconsistent and warrants further exploration due to the limited research on prescribing vocalization as a treatment (Fang et al., 2022). The neural drive of the expiratory muscles was significantly higher during high-loudness sounds compared with that during low-loudness sounds, and no differences were observed across varying pitches and vowel states. Second, high pitch and loudness produced higher dyspnea compared with low loudness and pitch. In addition, patients with higher MEP/MIP had lower respiratory muscle activation during the fixed loudness task.

Categorization of vowels into high vowels and low vowels, along with mid vowels, is a well-established concept in linguistics. Subglottic pressure is produced by respiratory and laryngeal muscles, which is necessary for voice change (Traser et al., 2020). However, no significant difference was found in the NRD of respiratory muscle under different pitches and vowels. Plexico and Sandage (2012) showed that under any evaluation frequency, the threshold pressure value was not significantly different among the three consonant-vowel sequences, similar to the present results. However, Pettersen et al. found significant differences in the activation of intercostal, lateral abdominal, and rectus abdominus with different pitch and loudness levels. The vocalization task in Pettersen’s study did not control for confounding factors, such as sound loudness. By contrast, loudness was controlled in this study, which may be the reason for the difference in the results (Pettersen, 2005). In addition, high-pitched voices produced prokinetic symptoms despite no significant respiratory muscle activation. Correspondingly, Wang and Yiu (2023). Showed that the activation level of suprhyal muscle was different with different vowels due to the different shapes of the mouth and the position of the tongue. Recruitment of laryngeal muscles increased significantly with increased pitch (Zhu et al., 2022). This finding suggests that perilaryngeal muscles rather than respiratory muscles produced pitch changes. This phenomenon is consistent with the view that the original power of the respiratory muscle produces sound and that the larynx and mouth are mainly used to modify the sound (Körner and Strack, 2023; Herbst, 2017). In conclusion, this study confirms that different pitches and vowels in different training programs do not directly affect respiratory muscle training effects.

The vocal effort produced significantly greater subglottic pressure during maximum-effort speech (Rosenthal et al., 2014), which may have increased the load during the expiratory phase. However, not all expiratory muscles were significantly associated with loudness. In the loudness control task, the lower ribcage embodied vocalization preferentially because only the 7thIC showed differences while PARA and RA did not. The lack of coordination of abdominal vocalization during the vocalization state in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease was unexpected. We observed a more generalized chest breathing habit in patients with COPD, which may explain the lack of pronounced abdominal muscle vocalization. Some research suggests that SCM muscles may help stabilize human vocalizations (Van Houtte et al., 2013). Pettersen et al. (2005) showed that when healthy ordinary people (professional or non-professional singers) participated in vocalization training and performed vocalization content with different loudness and pitch levels, the activities of the sternocleidomastoid muscle and trapezius muscle increased; this effect was more noticeable when the respiratory demand was strong. Similarly, our observational research showed that the NRD of respiratory muscle was not significantly higher than that of low-loudness vocalizations in SCM in patients with COPD.

Previous studies have shown that comprehensive pulmonary rehabilitation, based on standard protocols, can improve dyspnea and quality of life in patients (Troosters et al., 2023). However, there are still inconsistencies in vocalization training programs for COPD patients (Fang et al., 2022). This study offers clinical implications for the implementation of vocalization training. Regarding the physiological effects on patients, Fu et al. showed that collective singing and vocal training improved the maximum expiratory pressure and exercise ability of older people in the community (Fu et al., 2018). Lord et al. (2012) reported that the objective physiological state of patients with COPD did not change after vocalization training. However, the content and intensity of singing are not disclosed in vocalization studies, which may be the reason for the differences in the outcome indicators (Patel et al., 2022; Selickman and Marini, 2022). In addition, correlation analysis showed that vocalization of the same loudness produced great stimulation in patients with low respiratory muscle strength. This finding is consistent with the theory that the intercostal and abdominal muscles provide vocal expiratory support (Pettersen et al., 2005; De Troyer and Boriek, 2011). Muscle control and improvement are required to ensure an intensity threshold for training; according to the results of this study, vocalization at a lower intensity may not be sufficient to engage the respiratory muscles fully. At the same time, the degree of dyspnea after the high-loudness task was higher than that after the high-pitched task, while the degree of dyspnea between the low-loudness task and the low-pitched task was not significantly different. Hence, home oxygen therapy, breathing exercises, and other treatments that can improve dyspnea can be combined with vocalization training for improved clinical outcomes. Personalized vocalization prescriptions for patients with COPD should consider the respiratory muscle state of patients rather than simply pursuing vocalization loudness.

Although the study examined the NRD of respiratory muscles to different vocalization tasks, this study still has some limitations. First, this study only addressed the physiological effects of vocal tasks and did not address the psychological effects of vocal training as an artistic engagement. Second, all syllable pitches and loudness are difficult to study because of the patients’ limited tolerance. Relatively simple /a/, /i/, and/u/were chosen for this study, considering vocal teachers’ suggestions and previous studies. Finally, participants included patients with COPD only who had performed primary vocal exercises to study the effect of training on uninitiated patients. Therefore, the results of the article cannot be generalized to patients who have received full vocalization training.

In vocalization training for patients with COPD, focusing on increasing loudness, rather than pitch or vowel, led to the activation of the expiratory muscles. High pitches and loudness produced dyspnea compared with low pitches and low loudness. The maximal expiratory/inspiratory pressure was negatively correlated with respiratory muscle NRD in the same loudness vocalization task.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

The studies involving humans were approved by Qingdao Municipal Hospital Ethics Committee. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

ZQ: Data curation, Methodology, Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing. ZK: Formal Analysis, Methodology, Writing–original draft. JZ: Methodology, Writing–review and editing. DaL: Methodology, Writing–original draft. DoL: Writing–review and editing. XC: Writing–review and editing. KL: Funding acquisition, Methodology, Supervision, Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing.

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by the Health Science and Technology Development Program of Shandong Province (Grant No. 202020010606) and the Shinan District Science and Technology Plan Project (Grant No. 2022-2-014-YY).

Liu Yuying provided technical support for the author in completing the picture production.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

AbuNurah H. Y., Russell D. W., Lowman J. D. (2020). The validity of surface EMG of extra-diaphragmatic muscles in assessing respiratory responses during mechanical ventilation: a systematic review. Pulmonology 26 (6), 378–385. doi:10.1016/j.pulmoe.2020.02.008

Adeloye D., Chua S., Lee C., Basquill C., Papana A., Theodoratou E., et al. (2015). Global and regional estimates of COPD prevalence: systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Glob. Health 5 (2), 020415. doi:10.7189/jogh.05.020415

Adeloye D., Song P., Zhu Y., Campbell H., Sheikh A., Rudan I., et al. (2022). Global, regional, and national prevalence of, and risk factors for, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in 2019: a systematic review and modelling analysis. Lancet Respir. Med. 10 (5), 447–458. doi:10.1016/s2213-2600(21)00511-7

Awan S. N., Giovinco A., Owens J. (2012). Effects of vocal intensity and vowel type on cepstral analysis of voice. J. Voice 26 (5), 670.e15–e20. doi:10.1016/j.jvoice.2011.12.001

Awan S. N., Novaleski C. K., Yingling J. R. (2013). Test-retest reliability for aerodynamic measures of voice. J. Voice 27 (6), 674–684. doi:10.1016/j.jvoice.2013.07.002

Bane M., Angadi V., Andreatta R., Stemple J. (2023). The effect of maximum phonation time goal on efficacy of vocal function exercises. J. Voice. doi:10.1016/j.jvoice.2023.03.009

Bonilha A. G., Onofre F., Vieira M. L., Prado M. Y., Martinez J. A. (2009). Effects of singing classes on pulmonary function and quality of life of COPD patients. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 4, 1–8.

Cabral E. E. A., Fregonezi G. A. F., Melo L., Basoudan N., Mathur S., Reid W. D. (2018). Surface electromyography (sEMG) of extradiaphragm respiratory muscles in healthy subjects: a systematic review. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol 42, 123–135. doi:10.1016/j.jelekin.2018.07.004

Celli B., Fabbri L., Criner G., Martinez F. J., Mannino D., Vogelmeier C., et al. (2022). Definition and nomenclature of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: time for its revision. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 206 (11), 1317–1325. doi:10.1164/rccm.202204-0671PP

da Fonsêca J. D. M., Resqueti V. R., Benício K., Fregonezi G., Aliverti A. (2019). Acute effects of inspiratory loads and interfaces on breathing pattern and activity of respiratory muscles in healthy subjects. Front. Physiol. 10, 993. doi:10.3389/fphys.2019.00993

De Troyer A., Boriek A. M. (2011). Mechanics of the respiratory muscles. Compr. Physiol. 1 (3), 1273–1300. doi:10.1002/cphy.c100009

Fang X., Qiao Z., Yu X., Tian R., Liu K., Han W. (2022). Effect of singing on symptoms in stable COPD: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 17, 2893–2904. doi:10.2147/copd.S382037

Fu M. C., Belza B., Nguyen H., Logsdon R., Demorest S. (2018). Impact of group-singing on older adult health in senior living communities: a pilot study. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 76, 138–146. doi:10.1016/j.archger.2018.02.012

Herbst C. T. (2017). A review of singing voice subsystem interactions-toward an extended physiological model of support. J. Voice 31 (2), 249.e13–249. doi:10.1016/j.jvoice.2016.07.019

Higgins M. B., Netsell R., Schulte L. (1998). Vowel-related differences in laryngeal articulatory and phonatory function. J. Speech Lang. Hear Res. 41 (4), 712–724. doi:10.1044/jslhr.4104.712

Jolley C. J., Luo Y. M., Steier J., Rafferty G. F., Polkey M. I., Moxham J. (2015). Neural respiratory drive and breathlessness in COPD. Eur. Respir. J. 45 (2), 355–364. doi:10.1183/09031936.00063014

Kaasgaard M., Rasmussen D. B., Andreasson K. H., Hilberg O., Løkke A., Vuust P., et al. (2022). Use of Singing for Lung Health as an alternative training modality within pulmonary rehabilitation for COPD: a randomised controlled trial. Eur. Respir. J. 59 (5), 2101142. doi:10.1183/13993003.01142-2021

Körner A., Strack F. (2023). Articulation posture influences pitch during singing imagery. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 30, 2187–2195. doi:10.3758/s13423-023-02306-1

Lin L., Guan L., Wu W., Chen R. (2019). Correlation of surface respiratory electromyography with esophageal diaphragm electromyography. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 259, 45–52. doi:10.1016/j.resp.2018.07.004

Liu H., Song M., Zhai Z. H., Shi R. J., Zhou X. L. (2019). Group singing improves depression and life quality in patients with stable COPD: a randomized community-based trial in China. Qual. Life Res. 28 (3), 725–735. doi:10.1007/s11136-018-2063-5

Lord V. M., Hume V. J., Kelly J. L., Cave P., Silver J., Waldman M., et al. (2012). Singing classes for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Pulm. Med. 12, 69. doi:10.1186/1471-2466-12-69

McNamara R. J., Epsley C., Coren E., McKeough Z. J. (2017). Singing for adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 12 (12), Cd012296. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012296.pub2

Nguyen D. A. T., Lewis R. H. C., Boswell-Ruys C. L., Hudson A. L., Gandevia S. C., Butler J. E. (2020). Increased diaphragm motor unit discharge frequencies during quiet breathing in people with chronic tetraplegia. J. Physiol. 598 (11), 2243–2256. doi:10.1113/jp279220

Nolan C. M., Polgar O., Schofield S. J., Patel S., Barker R. E., Walsh J. A., et al. (2022). Pulmonary rehabilitation in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and COPD: a propensity-matched real-world study. Chest 161 (3), 728–737. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2021.10.021

O'Donnell D. E., Webb K. A. (2008). The major limitation to exercise performance in COPD is dynamic hyperinflation. J. Appl. Physiol. 105 (2), 753–755. discussion 755-7. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.90336.2008b

Patel N., Chong K., Baydur A. (2022). Methods and applications in respiratory physiology: respiratory mechanics, drive and muscle function in neuromuscular and chest wall disorders. Front. Physiol. 13, 838414. doi:10.3389/fphys.2022.838414

Pettersen V. (2005). Muscular patterns and activation levels of auxiliary breathing muscles and thorax movement in classical singing. Folia Phoniatr. Logop. 57 (5-6), 255–277. doi:10.1159/000087079

Pettersen V., Bjørkøy K., Torp H., Westgaard R. H. (2005). Neck and shoulder muscle activity and thorax movement in singing and speaking tasks with variation in vocal loudness and pitch. J. Voice 19 (4), 623–634. doi:10.1016/j.jvoice.2004.08.007

Pettersen V., Westgaard R. H. (2004). Muscle activity in professional classical singing: a study on muscles in the shoulder, neck and trunk. Logop. Phoniatr. Vocol 29 (2), 56–65. doi:10.1080/14015430410031661

Plexico L. W., Sandage M. J. (2012). Influence of vowel selection on determination of phonation threshold pressure. J. Voice 26 (5), 673.e7–12. doi:10.1016/j.jvoice.2011.12.005

Pozzi M., Rezoagli E., Bronco A., Rabboni F., Grasselli G., Foti G., et al. (2022). Accessory and expiratory muscles activation during spontaneous breathing trial: a physiological study by surface electromyography. Front. Med. (Lausanne) 9, 814219. doi:10.3389/fmed.2022.814219

Ramsook A. H., Koo R., Molgat-Seon Y., Dominelli P. B., Syed N., Ryerson C. J., et al. (2016). Diaphragm recruitment increases during a bout of targeted inspiratory muscle training. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc 48 (6), 1179–1186. doi:10.1249/mss.0000000000000881

Rosenthal A. L., Lowell S. Y., Colton R. H. (2014). Aerodynamic and acoustic features of vocal effort. J. Voice 28 (2), 144–153. doi:10.1016/j.jvoice.2013.09.007

Selickman J., Marini J. J. (2022). Chest wall loading in the ICU: pushes, weights, and positions. Ann. Intensive Care 12 (1), 103. doi:10.1186/s13613-022-01076-8

Stepp C. E. (2012). Surface electromyography for speech and swallowing systems: measurement, analysis, and interpretation. J. Speech Lang. Hear Res. 55 (4), 1232–1246. doi:10.1044/1092-4388(2011/11-0214

Suh E. S., Pompilio P., Mandal S., Hill P., Kaltsakas G., Murphy P. B., et al. (2020). Autotitrating external positive end-expiratory airway pressure to abolish expiratory flow limitation during tidal breathing in patients with severe COPD: a physiological study. Eur. Respir. J. 56 (3), 1902234. doi:10.1183/13993003.02234-2019

Traser L., Burk F., Özen A. C., Burdumy M., Bock M., Blaser D., et al. (2020). Respiratory kinematics and the regulation of subglottic pressure for phonation of pitch jumps - a dynamic MRI study. PLoS One 15 (12), e0244539. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0244539

Troosters T., Janssens W., Demeyer H., Rabinovich R. A. (2023). Pulmonary rehabilitation and physical interventions. Eur. Respir. Rev. 32 (168). doi:10.1183/16000617.0222-2022

Van Houtte E., Claeys S., D'Haeseleer E., Wuyts F., Van Lierde K. (2013). An examination of surface EMG for the assessment of muscle tension dysphonia. J. Voice 27 (2), 177–186. doi:10.1016/j.jvoice.2011.06.006

Wang F., Yiu E. M. (2023). Surface electromyographic (sEMG) activity of the suprahyoid and sternocleidomastoid muscles in pitch and loudness control. Front. Physiol. 14, 1147795. doi:10.3389/fphys.2023.1147795

Keywords: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, vocalization training, neural respiratory drive, respiratory muscle, surface electromyographic

Citation: Qiao Z, Kou Z, Zhang J, Lv D, Li D, Cui X and Liu K (2025) Optimal vocal therapy for respiratory muscle activation in patients with COPD: effects of loudness, pitch, and vowels. Front. Physiol. 15:1496243. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2024.1496243

Received: 14 September 2024; Accepted: 25 October 2024;

Published: 13 January 2025.

Edited by:

Cui Zhang, Shandong Institute of Sport Science, ChinaReviewed by:

Hubert Forster, Medical College of Wisconsin, United StatesCopyright © 2025 Qiao, Kou, Zhang, Lv, Li, Cui and Liu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kai Liu, a2FpbGl1QHVvci5lZHUuY24=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.