- 1Department of Physiology & Pharmacology, Robarts Research Institute, Schulich School of Medicine, University of Western Ontario, London, ON, Canada

- 2Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, Faculty of Pharmacy, Alexandria University, Alexandria, Egypt

Arterial networks are controlled by the consolidated output of stimuli that set “how much” (magnitude) and “where” (distribution) blood flow is delivered. While notable changes in magnitude are tied to network wide responses, altered distribution often arises from focal changes in tone, whose mechanistic foundation remains unclear. We propose herein a framework of focal vasomotor contractility being controlled by pharmacomechanical coupling and the generation of Ca2+ waves via the sarcoplasmic reticulum. We argue the latter is sustained by receptor operated, transient receptor potential (TRP) channels through direct extracellular Ca2+ influx or indirect Na+ influx, reversing the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger. We view this focal regulatory mechanism as complementary, but not redundant with, electromechanical coupling in the precision tuning of blood flow delivery.

1 Introduction

Arterial networks are rationalized as an intricate system of segments which serves to set blood flow magnitude and adapt its distribution dependent on local energetic demands. Arteries are described as single-layered tubes of endothelial cells surrounded by smooth muscle cells arranged in a circular fashion. Endothelial cells are arranged parallel to the axis of blood flow and as they are in intimate contact with blood, they respond to mechanical forces like shear stress. They are strongly coupled to one another, unlike smooth muscle, and thus constitute the primary pathway for electrical and chemical signals to spread along vasculature (Mironova et al., 2024). Smooth muscle cells are circumferentially arranged and retain the contractile machinery responsible for altering arterial tone. Tone within arterial networks is governed by multiple stimuli, the most important being intravascular pressure, blood flow, neural activity, and a range of endothelial derived factors. Alterations in smooth muscle [Ca2+] are the principal driver of arterial tone, with cytosolic levels largely set by the activity of voltage gated Ca2+ channels. The standard mechanistic paradigm, commonly termed electromechanical coupling, is straightforward in thought, thousands of smooth muscle cells exposed to a defined stimulus (e.g., intravascular pressure) subtly change their conductance to Na+, Cl− or K+. With the aid of gap junction, charge spreads among coupled vascular cells, producing a homogenous membrane potential response that gates L- and to a lesser extent T-type Ca2+ channels. The ensuing cytosolic Ca2+ response modulates myosin light chain kinase and consequently the contractile state of smooth muscle. These integrated responses have garnered deep interrogation as they set the foundation of blood flow control and coordinate the dilations that increase tissue perfusion with rising metabolic demand. What is often overlooked in such examinations is the need to discretely tune blood flow distribution by allowing segments, in particular terminal/pre-capillary arterioles, to focally constrict independent of the broader structure (Sweeney et al., 2016; Grubb et al., 2020; Zambach et al., 2021). Such behavior is observable in isolated vessels and in-vivo to focal agent delivery, and it is insensitive to membrane potential and the influx of Ca2+ via L-type Ca2+ channels. Voltage insensitive contraction is often termed pharmacomechanical coupling, and its transduction is tied to signaling pathways activated G-protein coupled receptors.

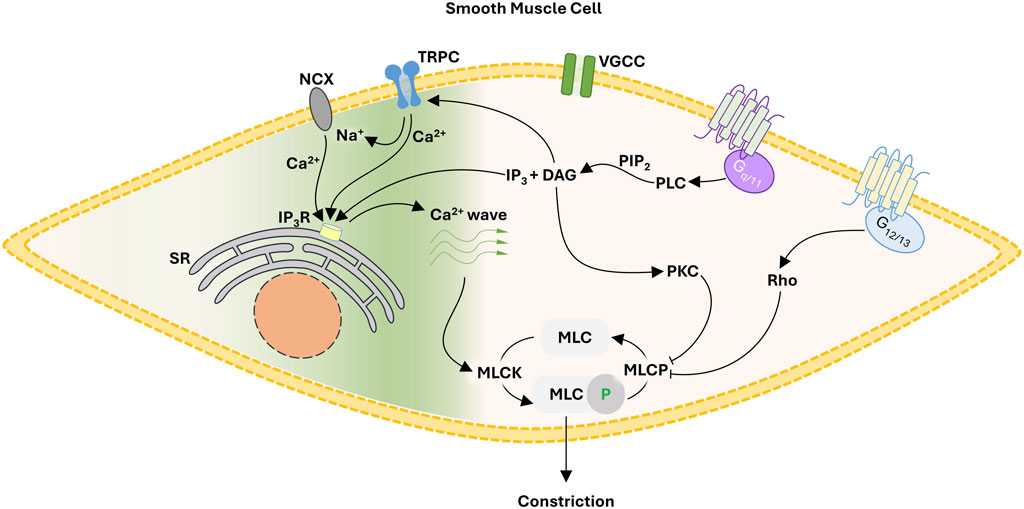

The query addressed herein centers on how focal constrictor events can be generated independent of electromechanical coupling. Reason dictates careful consideration of pharmacomechanical coupling and the regulation of myosin light chain phosphatase (MLCP) through Gq/11 and G12/13 coupled signal pathways (Figure 1). Gq/11 coupled receptors (e.g., α1 adrenoreceptors) activate phospholipase C-β, the ensuing hydrolysis of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate leading to diacylglycerol and inositol triphosphate (IP3) production. The former leads to the activation of protein kinase C and the phosphorylation of CPI-17, an upstream inhibitor of the MLCP catalytic subunit (PP1c). In contrast, G12/13 coupled receptors (e.g., thromboxane A2 receptor) activate the monomeric G-protein RhoA and then Rho-kinase to regulate the MLCP targeting subunit, MYPT1 via two key phosphorylation sites (T-697 & T-855). While MLCP inhibition is logically essential for focal vasoconstrictor control, a Ca2+ signal, one modest in magnitude and uncoupled to voltage, is still required for myosin light chain kinase (MLCK) activation. While the mechanistic foundation of this Ca2+ signal remains unsettled, it is intriguing to consider Ca2+ waves which originate from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) and are triggered by IP3 production and extracellular Ca2+ influx through an elusive Ca2+ permeable pore. The subsequent sections will consider the molecular identity of that Ca2+ permeable pore and how a voltage-insensitive Ca2+ source shapes focal tone development and blood flow distribution throughout integrated arterial networks.

FIGURE 1. Proposed framework for focal constriction through pharmacomechanical coupling, a process independent of membrane potential and VGCC. A Gq/11 signaling pathway inhibits MLCP while activating TRPC cationic channels. The latter, operating as a Ca2+ influx pathway or by reversing NCX transport, facilitates the generation of Ca2+ waves necessary for MLCK activation. Abbreviations: NCX, Na+/Ca2+ exchanger; TRPC, canonical transient receptor potential channel; VGCC, voltage-gated Ca2+ channel; SR, sarcoplasmic reticulum; IP3, inositol triphosphate; DAG, diacyl glycerol; PLC, phospholipase C; PIP2, phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate; MLC, myosin light chain; MLCK, MLC kinase; MLCP, MLC phosphatase.

2 The sarcoplasmic reticulum and Ca2+ waves

Vascular smooth muscle retains sarcoplasmic reticulum, an internal store that releases Ca2+ upon activation of ryanodine or IP3-sensitive receptors (IP3R). Ca2+ release takes the form of several definable events, the two most common being “Ca2+ sparks” and “Ca2+ waves.” Ca2+ sparks, as discerned by Nelson et al. (1995) are focal voltage-dependent events that rapidly activate large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels, thus initiate spontaneous transient outward currents (STOCs). In resistance arteries, STOCs drive a feedback hyperpolarization that moderates constriction initiated by stimuli like intravascular pressure. Ca2+ waves are slower events (1–3 s, duration) characterized by a wave front spreading from end-to-end within one cell and then asynchronously among neighboring cells. Their spatial/temporal heterogeneity is notably distinct from the synchronous, oscillatory behavior underpinning arterial vasomotion (Seppey et al., 2009). Asynchronous Ca2+ waves display voltage-insensitive properties and their abolishment moderates tone development to superfused agonist (Jaggar and Nelson, 2000; Mufti et al., 2010). Ca2+ waves reflect regenerative Ca2+-induced Ca2+-release among neighboring IP3 and/or ryanodine receptors, an event dependent on IP3 production and extracellular Ca2+ influx. The latter would be presumptively important to driving the initial opening of IP3Rs or to refilling of the SR. What is the most likely identity of this Ca2+ permeable pore?

3 Ca2+ permeable pores and Ca2+ waves

3.1 The fabled “receptor operated Ca2+ channel”

Receptor operated Ca2+ channels were first rationalized by Somlyo and Somlyo (1968) to partly explain persistent agonist-induced tone following L-type Ca2+ channel blockade. Despite this early conceptualization, the identity of “receptor operated Ca2+ channels” remained elusive for decades as its electrophysiological and pharmacological fingerprint was variable and difficult to define. A bona fide target emerged in the 21st century, with the isolation of transient receptor potential (TRP) channels, named after a mutant drosophila strain with visual cue blindness (Cosens and Manning, 1969). Molecular studies revealed TRP channels as a diverse group of cation permeable pores, comprised of 4 pore forming subunits, 6 transmembrane domains each and intracellular termini whose molecular diversity imparts unique regulatory properties (Hellmich and Gaudet, 2014). There are six subfamilies, the first identified being the canonical (TRPC) class (Wes et al., 1995) followed by those: 1) modulated by “vanilloid”-like molecules (TRPV; Caterina et al., 1997); and 2) retaining C-terminal repeats related to the “ankyrin” protein (TRPA; Jaquemar et al., 1999). Genomic analysis of disease pathologies subsequently identified the final three subfamilies that being the melanoma metastasis/TRP melastatin (TRPM; Duncan et al., 1998), the autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease/TRP polycycstin (TRPP; Mochizuki et al., 1996), and the human mucolipidosis type IV/TRP mucolipin (TRPML; Bargal et al., 2000). While multiple TRP subunits are expressed in vascular smooth muscle, the canonical subclass has garnered particular attention as activation is coupled to Gq signal transduction, rendering it “receptor operated.” TRPC channels pass both mono- (e.g., Na2+) and di- (Ca2+) valents, their relative permeability set by subunit composition (Bolton, 1979; Putney and Tomita, 2012). As such, they can operate as a depolarizing current and/or a Ca2+ influx pathway that drives: 1) electrical feedback, via the large conductance Ca2+ activated K+ channel (Earley et al., 2005); or 2) Ca2+ wave generation (Figure 1). We will consider the latter below, with attention focused on two TRPC channel subunits for which foundational data is available. We acknowledge a priori TRPC channel subunits do heteromultimerize, but due to a lack of functional observations, discussion on this topic cannot be advanced.

3.1.1 TRPC6

TRPC6 is ubiquitously expressed in vascular smooth muscle and recognized for its relatively high permeability to Ca2+ over Na+ (5-6:1; Hofmann et al., 1999; Dietrich et al., 2003). When expressed in HEK293 cells, TRPC6 channels displayed two prominent properties, that being dual rectification and the induction of a cytosolic Ca2+ response following activation (Dietrich et al., 2003; Estacion et al., 2006). TRPC6 were first reported as a Gq-coupled, receptor operated Ca2+ channel in fibroblast-like monkey cells (Boulay et al., 1997), an observation later transposed into vascular smooth muscle (Inoue et al., 2001; Anfinogenova et al., 2011). As to the latter, Ca2+ influx through TRPC6 channels is under the regulatory control of catecholamines (Inoue et al., 2001) along with vasopressin (Maruyama et al., 2006) and angiotensin II (Saleh et al., 2006). Evidence that Ca2+ influx via TRPC6 might facilitate to SR Ca2+ wave generation is developing but somewhat indirect, with evidence showing that: 1) channel clusters form in plasma membrane adjacent to the SR; and 2) TRPC6 knockdown is associated with a reduction in agonist induced, Ca2+ oscillations in cultured smooth muscle cells (Li et al., 2008).

3.1.2 TRPC3

TRPC3 cation channels shares similarities to TPRC6 being activated by Gq-coupled agonists (Liu et al., 2009) and displaying inward and outward rectification (Kamouchi et al., 1999). It is however distinct from TRPC6, in that basal activity is higher (Dietrich and Gudermann, 2007) and selectivity to Ca2+ over Na+ is reduced (1.6:1; Kamouchi et al., 1999). Arteries from TRPC3−/− mice display diminished constriction to phenylephrine (Yeon et al., 2014), presumptively due to TRPC3 inducing a depolarization that triggers L-type Ca2+ channels (Reading et al., 2005; Pereira da Silva et al., 2022). While reasoned, more recent work has suggested that TRPC3 may also act as a receptor operated Ca2+ channel, enabling tone development through Ca2+ waves induction. Of particular interest are findings showing that TRPC3 binds to IP3R (Yuan et al., 2003; Adebiyi et al., 2012) through its calmodulin/IP3R binding domain (Zhang et al., 2001). This C-terminus motif impacts channel gating (Wedel et al., 2003) and presumptively the concomitant Ca2+ influx needed to initiate or sustain SR Ca2+ waves generation (Curcic et al., 2022). Note, TRPC1 also been alluded to interact with IP3Rs although findings remain limited (Yuan et al., 2003).

3.1.3 Indirect role for TRPC channels?

While it reasoned to suggest that Ca2+ influx through TRPC channels induces SR Ca2+ waves directly, there is a body of literature which suggests their role in internal Ca2+ mobilization is indirect. Consider the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger, an antiporter that employs the Na+ electrochemical gradient to facilitate the efflux of Ca2+. Due to its electrogenic nature, the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger can operate in reverse mode, enabling the Ca2+ influx presumptively needed to drive Ca2+ wave generation (Blaustein and Lederer, 1999) (Figure 1). This perspective aligns with past work showing that Na+/Ca2+ exchanger inhibition not only diminishes Ca2+ waves but the generation of nifedipine-insensitive tone (Dai et al., 2006; Syyong et al., 2009). Antiporter reversal occurs when cells are depolarized or when local intercellular [Na+] rises, presumptively due to TRPC channel activation and monovalent influx (Rosker et al., 2004; Lemos et al., 2007). While evidence is somewhat circumspect, past studies have shown a physical association between TRPC channels and NCX. TRPC3 coimmunoprecipitates with NCX in transfected HEK cells (Rosker et al., 2004), while in vascular smooth muscle, Na+/Ca2+ exchangers are thought to cluster in association with TRPC6 adjacent to the sarcoplasmic reticulum (Poburko et al., 2007).

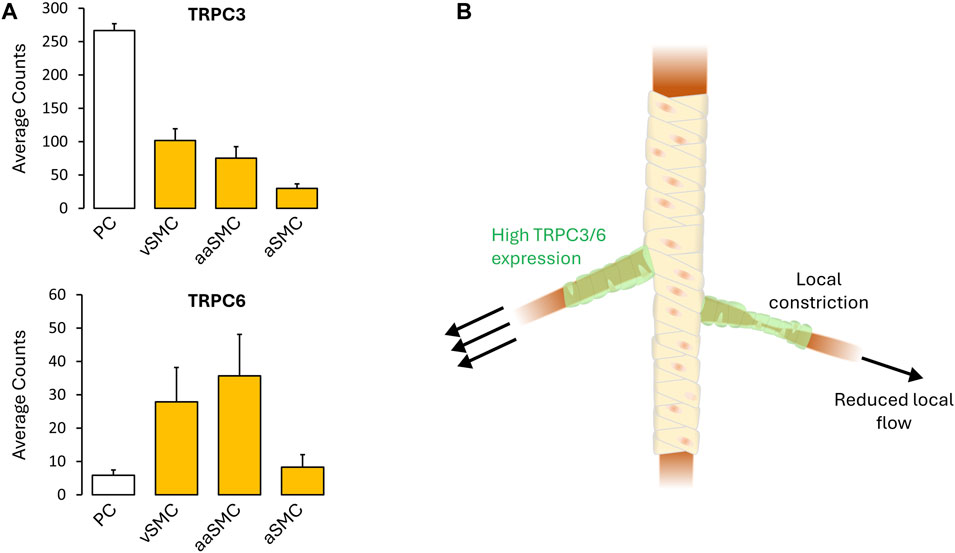

4 Focal constriction and the spatial throttling of blood supply

Fundamental understanding of vascular control is shaped by prevailing tools and the manner in which experiments are designed to probe biological behavior. In this regard, the use of vessel myography is central, as is the examination of arterial tone to agonists broadly applied to a bath. The interpretational consequence of this embedded approach is to view arterial tone as a global integrated phenomenon, among and across vessel segments, a property essential to the control of blood flow magnitude. As such, electro- and pharmaco-mechanical coupling, the latter of which incorporates receptor operated Ca2+ channels/Ca2+ sensitization, are viewed as contractile mechanisms working proportionally and synergistically with one another. Deeper examination, however, reveals a flaw in this reasoning, embodied by this query “Why are two distinct contractile mechanisms needed to regulate a singular aspect of arterial tone development and presumptively blood flow control? Indeed, integrated tone control across vessels and branch points can be achieved through electromechanical coupling alone, as charge spread through gap junctions ensures a comparable VM and cytosolic Ca2+ response across thousands of smooth muscle cells. Could it be that pharmacomechanical coupling encodes for an aspect of blood flow delivery distinct from “magnitude”? Consider for example, a single terminal arteriole and the associated tuning of blood flow “distribution” within each capillary network. Local tuning presumptively requires focal vasomotor control, a response difficult to achieve via electromechanical coupling as the charge arise from a small number of activated cells gets readily diluted into the large mass of unstimulated cells to which they are coupled. It is in this context that the value of pharmacomechanical coupling, with its dependence on MLCP regulation and receptor operated Ca2+ channel activation, becomes evident. Although observations are limited, brain studies have noted that precapillary arterioles can operate in a sphincter-like manner as they branch from the penetrating arteriole. The mural cells embedded in these segments are intriguing in many aspects (Phillips et al., 2022), perhaps most notably herein, the robust expression of TRPC3 and TRPC6 (He et al., 2018; Vanlandewijck et al., 2018) (Figure 2). Vasomotor heterogeneity is also observable across the length of a penetrating arterioles, a behavior consistent although not definitive for, focal zones of enhanced TRPC channel expression and pharmacomechanical control (Institoris et al., 2015; Chow et al., 2020). What triggers focal vasomotor responses in organs like the brain, remains a question of active inquiry. Perhaps, a single astrocytic endfoot produces a diffusible signal from appropriate sensory input that tunes pharmacomechanical rather than electromechanical coupling. Arguably, pharmacomechanical regulation might also be achieved via direct neural synapses onto smooth muscle, regions of which have been recently identified by scanning electron microscopy (Zhang et al., 2024). The genesis of focal vasomotor tone should also be rationalized in a pathobiological context. Consider for example, cerebral arterial vasospasm, a profound local constriction induced by the extravasation of blood, and which elicits stroke-like symptoms. These deleterious responses are often refractory to L-type Ca2+ channel blockade, and thus presumptively pharmacomechanical in foundation. It follows that targeting key pathways and signaling proteins underpinning pharmacomechanical coupling may be of clinical benefit to appropriate patient populations.

FIGURE 2. (A) TRPC3/6 expression (defined as cellular transcript counts/cell) in the mouse brain mural cells, as determined by single-cell RNA sequencing. Note the strong TRPC3/6 expression. Figures provided by http://betsholtzlab.org/VascularSingleCells/database.html (He et al., 2018; Vanlandewijck et al., 2018). (B) Spatial throttling of blood supply through pharmacomechanical coupling independent of an integrated electrical signal. Abbreviations: PC, pericytes; SMC, smooth muscle cells; v, venous; a, arterial; aa, arteriolar.

5 Summary

A putative receptor activated TRPC channel in a cohort of smooth muscle cells, could serve as a Ca2+ source to drive SR Ca2+ wave generation and a local pharmacomechanical constrictor response, independent of membrane potential. Contrary to electromechanical coupling where an electrical signal integrated across vessel segments sets blood flow magnitude, local VM-independent constriction would be presumptively designed to tune distribution. In this regard, pharmacomechanical coupling should be view as functional distinctive from electromechanical coupling but essential to the optimization of demand/supply coupling to active tissues (Figure 2). While an intriguing concept, experimental validation is essential, the first step being the identification of local constrictor sites in vivo, a process which has begun. Further, it is interesting to consider whether such sites are molecularly unique, perhaps displaying enhanced expression of receptor operated Ca2+ channels. One could alternatively argue that these sites of point control receive additional inputs from surrounding parenchymal cells, for example, defined astrocytic end feet or the sparely arranged interneurons in brain. Further experimentation is clearly needed to deepen insight on this novel aspect of blood flow control. Likewise, intricate computers models of contractile control, akin to those used to probe intercellular conduction in brain microvascular networks will provide further conceptual insight and set new boundaries to our understanding of blood flow coupling to energetic demands.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

MAE: Conceptualization, Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing, Funding acquisition. DGW: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing, Funding acquisition.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was funded by the Natural Science and Engineering Council of Canada [RGPIN-2017-04659 (DGW)], Canadian Institutes of Health Research [PG RN452347 – 462379 (DGW) and CGS-D RN498499 – 493860 (MAE)], and the Rorabeck Chair in Molecular Neuroscience and Vascular Biology (DGW).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adebiyi A., Thomas-Gatewood C. M., Leo M. D., Kidd M. W., Neeb Z. P., Jaggar J. H. (2012). An elevation in physical coupling of type 1 inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) receptors to transient receptor potential 3 (TRPC3) channels constricts mesenteric arteries in genetic hypertension. Hypertension 60, 1213–1219. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.112.198820

Anfinogenova Y., Brett S. E., Walsh M. P., Harraz O. F., Welsh D. G. (2011). Do TRPC-like currents and G protein-coupled receptors interact to facilitate myogenic tone development? Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 301, H1378–H1388. doi:10.1152/ajpheart.00460.2011

Bargal R., Avidan N., Ben-Asher E., Olender Z., Zeigler M., Frumkin A., et al. (2000). Identification of the gene causing mucolipidosis type IV. Nat. Genet. 26, 118–123. doi:10.1038/79095

Blaustein M. P., Lederer W. J. (1999). Sodium/calcium exchange: its physiological implications. Physiol. Rev. 79, 763–854. doi:10.1152/physrev.1999.79.3.763

Bolton T. B. (1979). Mechanisms of action of transmitters and other substances on smooth muscle. Physiol. Rev. 59, 606–718. doi:10.1152/physrev.1979.59.3.606

Boulay G., Zhu X., Peyton M., Jiang M., Hurst R., Stefani E., et al. (1997). Cloning and expression of a novel mammalian homolog of Drosophila transient receptor potential (Trp) involved in calcium entry secondary to activation of receptors coupled by the Gq class of G protein. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 29672–29680. doi:10.1074/jbc.272.47.29672

Caterina M. J., Schumacher M. A., Tominaga M., Rosen T. A., Levine J. D., Julius D. (1997). The capsaicin receptor: a heat-activated ion channel in the pain pathway. Nature 389, 816–824. doi:10.1038/39807

Chow B. W., Nunez V., Kaplan L., Granger A. J., Bistrong K., Zucker H. L., et al. (2020). Caveolae in CNS arterioles mediate neurovascular coupling. Nature 579, 106–110. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2026-1

Cosens D. J., Manning A. (1969). Abnormal electroretinogram from a Drosophila mutant. Nature 224, 285–287. doi:10.1038/224285a0

Curcic S., Erkan-Candag H., Pilic J., Malli R., Wiedner P., Tiapko O., et al. (2022). TRPC3 governs the spatiotemporal organization of cellular Ca2+ signatures by functional coupling to IP3 receptors. Cell Calcium 108, 102670. doi:10.1016/j.ceca.2022.102670

Dai J. M., Kuo K. H., Leo J. M., Van Breemen C., Lee C. H. (2006). Mechanism of ACh-induced asynchronous calcium waves and tonic contraction in porcine tracheal muscle bundle. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 290, L459–L469. doi:10.1152/ajplung.00092.2005

Dietrich A., Gudermann T. (2007). “TRPC6,” in Transient receptor potential (TRP) channels. Editors V. Flockerzi, and B. Nilius (Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer), 125–141.

Dietrich A., Y Schnitzler M. M., Emmel J., Kalwa H., Hofmann T., Gudermann T. (2003). N-linked protein glycosylation is a major determinant for basal TRPC3 and TRPC6 channel activity. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 47842–47852. doi:10.1074/jbc.M302983200

Duncan L. M., Deeds J., Hunter J., Shao J., Holmgren L. M., Woolf E. A., et al. (1998). Down-regulation of the novel gene melastatin correlates with potential for melanoma metastasis. Cancer Res. 58, 1515–1520.

Earley S., Heppner T. J., Nelson M. T., Brayden J. E. (2005). TRPV4 forms a novel Ca2+ signaling complex with ryanodine receptors and BKCa channels. Circ. Res. 97, 1270–1279. doi:10.1161/01.RES.0000194321.60300.d6

Estacion M., Sinkins W. G., Jones S. W., Applegate M. A., Schilling W. P. (2006). Human TRPC6 expressed in HEK 293 cells forms non-selective cation channels with limited Ca2+ permeability. J. Physiol. 572, 359–377. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2005.103143

Grubb S., Cai C., Hald B. O., Khennouf L., Murmu R. P., Jensen A. G. K., et al. (2020). Precapillary sphincters maintain perfusion in the cerebral cortex. Nat. Commun. 11, 395. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-14330-z

He L., Vanlandewijck M., Mae M. A., Andrae J., Ando K., Del Gaudio F., et al. (2018). Single-cell RNA sequencing of mouse brain and lung vascular and vessel-associated cell types. Sci. Data 5, 180160. doi:10.1038/sdata.2018.160

Hellmich U. A., Gaudet R. (2014). Structural biology of TRP channels. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 223, 963–990. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-05161-1_10

Hofmann T., Obukhov A. G., Schaefer M., Harteneck C., Gudermann T., Schultz G. (1999). Direct activation of human TRPC6 and TRPC3 channels by diacylglycerol. Nature 397, 259–263. doi:10.1038/16711

Inoue R., Okada T., Onoue H., Hara Y., Shimizu S., Naitoh S., et al. (2001). The transient receptor potential protein homologue TRP6 is the essential component of vascular α1-adrenoceptor–activated Ca2+-permeable cation channel. Circulation Res. 88, 325–332. doi:10.1161/01.res.88.3.325

Institoris A., Rosenegger D. G., Gordon G. R. (2015). Arteriole dilation to synaptic activation that is sub-threshold to astrocyte endfoot Ca2+ transients. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 35, 1411–1415. doi:10.1038/jcbfm.2015.141

Jaggar J. H., Nelson M. T. (2000). Differential regulation of Ca2+ sparks and Ca2+ waves by UTP in rat cerebral artery smooth muscle cells. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 279, C1528–C1539. doi:10.1152/ajpcell.2000.279.5.C1528

Jaquemar D., Schenker T., Trueb B. (1999). An ankyrin-like protein with transmembrane domains is specifically lost after oncogenic transformation of human fibroblasts. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 7325–7333. doi:10.1074/jbc.274.11.7325

Kamouchi M., Philipp S., Flockerzi V., Wissenbach U., Mamin A., Raeymaekers L., et al. (1999). Properties of heterologously expressed hTRP3 channels in bovine pulmonary artery endothelial cells. J. Physiol. 518, 345–358. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0345p.x

Lemos V. S., Poburko D., Liao C. H., Cole W. C., Van Breemen C. (2007). Na+ entry via TRPC6 causes Ca2+ entry via NCX reversal in ATP stimulated smooth muscle cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 352, 130–134. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.10.160

Li M., Zacharia J., Sun X., Wier W. G. (2008). Effects of siRNA knock-down of TRPC6 and InsP3R1 in vasopressin-induced Ca2+ oscillations of A7r5 vascular smooth muscle cells. Pharmacol. Res. 58, 308–315. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2008.09.004

Liu D., Yang D., He H., Chen X., Cao T., Feng X., et al. (2009). Increased transient receptor potential canonical type 3 channels in vasculature from hypertensive rats. Hypertension 53, 70–76. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.116947

Maruyama Y., Nakanishi Y., Walsh E. J., Wilson D. P., Welsh D. G., Cole W. C. (2006). Heteromultimeric TRPC6-TRPC7 channels contribute to arginine vasopressin-induced cation current of A7r5 vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ. Res. 98, 1520–1527. doi:10.1161/01.RES.0000226495.34949.28

Mironova G. Y., Kowalewska P. M., El-Lakany M., Tran C. H. T., Sancho M., Zechariah A., et al. (2024). The conducted vasomotor response and the principles of electrical communication in resistance arteries. Physiol. Rev. 104, 33–84. doi:10.1152/physrev.00035.2022

Mochizuki T., Wu G., Hayashi T., Xenophontos S. L., Veldhuisen B., Saris J. J., et al. (1996). PKD2, a gene for polycystic kidney disease that encodes an integral membrane protein. Science 272, 1339–1342. doi:10.1126/science.272.5266.1339

Mufti R. E., Brett S. E., Tran C. H., Abd El-Rahman R., Anfinogenova Y., El-Yazbi A., et al. (2010). Intravascular pressure augments cerebral arterial constriction by inducing voltage-insensitive Ca2+ waves. J. Physiol. 588, 3983–4005. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2010.193300

Nelson M. T., Cheng H., Rubart M., Santana L. F., Bonev A. D., Knot H. J., et al. (1995). Relaxation of arterial smooth muscle by calcium sparks. Science 270, 633–637. doi:10.1126/science.270.5236.633

Pereira Da Silva E. A., Martin-Aragon Baudel M., Navedo M. F., Nieves-Cintron M. (2022). Ion channel molecular complexes in vascular smooth muscle. Front. Physiol. 13, 999369. doi:10.3389/fphys.2022.999369

Phillips B., Clark J., Martineau É., Rungta R. L. (2022). Store-operated Ca2+ channels mediate microdomain Ca2+ signals and amplify gq-coupled Ca2+ elevations in capillary pericytes. bioRxiv.

Poburko D., Liao C. H., Lemos V. S., Lin E., Maruyama Y., Cole W. C., et al. (2007). Transient receptor potential channel 6-mediated, localized cytosolic [Na+] transients drive Na+/Ca2+ exchanger-mediated Ca2+ entry in purinergically stimulated aorta smooth muscle cells. Circ. Res. 101, 1030–1038. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.155531

Putney J. W., Tomita T. (2012). Phospholipase C signaling and calcium influx. Adv. Biol. Regul. 52, 152–164. doi:10.1016/j.advenzreg.2011.09.005

Reading S. A., Earley S., Waldron B. J., Welsh D. G., Brayden J. E. (2005). TRPC3 mediates pyrimidine receptor-induced depolarization of cerebral arteries. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 288, H2055–H2061. doi:10.1152/ajpheart.00861.2004

Rosker C., Graziani A., Lukas M., Eder P., Zhu M. X., Romanin C., et al. (2004). Ca2+ signaling by TRPC3 involves Na+ entry and local coupling to the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 13696–13704. doi:10.1074/jbc.M308108200

Saleh S. N., Albert A. P., Peppiatt C. M., Large W. A. (2006). Angiotensin II activates two cation conductances with distinct TRPC1 and TRPC6 channel properties in rabbit mesenteric artery myocytes. J. Physiol. 577, 479–495. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2006.119305

Seppey D., Sauser R., Koenigsberger M., Bény J.-L., Meister J.-J. (2009). Intercellular calcium waves are associated with the propagation of vasomotion along arterial strips. Am. J. Physiology-Heart Circulatory Physiology 298, H488–H496. doi:10.1152/ajpheart.00281.2009

Somlyo A. V., Somlyo A. P. (1968). Electromechanical and pharmacomechanical coupling in vascular smooth muscle. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 159, 129–145.

Sweeney M. D., Ayyadurai S., Zlokovic B. V. (2016). Pericytes of the neurovascular unit: key functions and signaling pathways. Nat. Neurosci. 19, 771–783. doi:10.1038/nn.4288

Syyong H. T., Yang H. H., Trinh G., Cheung C., Kuo K. H., Van Breemen C. (2009). Mechanism of asynchronous Ca2+ waves underlying agonist-induced contraction in the rat basilar artery. Br. J. Pharmacol. 156, 587–600. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.2008.00063.x

Vanlandewijck M., He L., Mae M. A., Andrae J., Ando K., Del Gaudio F., et al. (2018). A molecular atlas of cell types and zonation in the brain vasculature. Nature 554, 475–480. doi:10.1038/nature25739

Wedel B. J., Vazquez G., Mckay R. R., St J. B. G., Putney J. W. (2003). A calmodulin/inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) receptor-binding region targets TRPC3 to the plasma membrane in a calmodulin/IP3 receptor-independent process. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 25758–25765. doi:10.1074/jbc.M303890200

Wes P. D., Chevesich J., Jeromin A., Rosenberg C., Stetten G., Montell C. (1995). TRPC1, a human homolog of a Drosophila store-operated channel. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 92, 9652–9656. doi:10.1073/pnas.92.21.9652

Yeon S. I., Kim J. Y., Yeon D. S., Abramowitz J., Birnbaumer L., Muallem S., et al. (2014). Transient receptor potential canonical type 3 channels control the vascular contractility of mouse mesenteric arteries. PLoS One 9, e110413. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0110413

Yuan J. P., Kiselyov K., Shin D. M., Chen J., Shcheynikov N., Kang S. H., et al. (2003). Homer binds TRPC family channels and is required for gating of TRPC1 by IP3 receptors. Cell 114, 777–789. doi:10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00716-5

Zambach S. A., Cai C., Helms H. C. C., Hald B. O., Dong Y., Fordsmann J. C., et al. (2021). Precapillary sphincters and pericytes at first-order capillaries as key regulators for brain capillary perfusion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 118, e2023749118. doi:10.1073/pnas.2023749118

Zhang D., Ruan J., Peng S., Li J., Hu X., Zhang Y., et al. (2024). Synaptic-like transmission between neural axons and arteriolar smooth muscle cells drives cerebral neurovascular coupling. Nat. Neurosci. 27, 232–248. doi:10.1038/s41593-023-01515-0

Keywords: TRP channels, Ca2+ waves, pharmacomechanical coupling, receptor operated Ca2+ channels, vascular ion channels

Citation: El-Lakany MA and Welsh DG (2024) TRP channels: a provocative rationalization for local Ca2+ control in arterial tone development. Front. Physiol. 15:1374730. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2024.1374730

Received: 22 January 2024; Accepted: 15 February 2024;

Published: 28 February 2024.

Edited by:

Silvestro Roatta, University of Turin, ItalyReviewed by:

Erik Josef Behringer, Loma Linda University, United StatesCopyright © 2024 El-Lakany and Welsh. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mohammed A. El-Lakany, bWVsbGFrYW5AdXdvLmNh

Mohammed A. El-Lakany

Mohammed A. El-Lakany Donald G. Welsh

Donald G. Welsh