- 1Sports Performance Division, Institut Sukan Negara Malaysia (National Sports Institute of Malaysia), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

- 2Department of Sport and Exercise Science, Faculty of Applied Sciences, Tunku Abdul Rahman University of Management and Technology, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

- 3Scientific Conditioning Centre, Hong Kong Sports Institute, Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

- 4Division of Health, Engineering Computing and Science, Te Huataki Waiora School of Health, University of Waikato, Tauranga, New Zealand

- 5Aspetar, Orthopaedic and Sports Medicine Hospital, FIFA Medical Centre of Excellence, Doha, Qatar

- 6Research Institute for Sport and Exercise, University of Canberra, Canberra, ACT, Australia

Purpose: We evaluated the extent of changes in training practices, recovery, mental health, and sleep patterns of athletes during the early COVID-19 lockdown in a single country-cohort.

Methods: A total of 686 athletes (59% male, 41% female; 9% World Class, 28% International, 29% National, 26% State, 8% Recreational) from 50 sports (45% individual, 55% team) in Malaysia completed an online, survey-based questionnaire study. The questions were related to training practices (including recovery and injury), mental health, and sleep patterns.

Results: Relative to pre-lockdown, training intensity (−34%), frequency (−20%, except World-Class), and duration (−24%–59%, especially International/World-Class) were compromised, by the mandated lockdown. During the lockdown, more space/access (69%) and equipment (69%) were available for cardiorespiratory training, than technical and strength; and these resources favoured World-Class athletes. Most athletes trained for general strength/health (88%) and muscular endurance (71%); and some used innovative/digital training tools (World-Class 48% vs. lower classification-levels ≤34%). More World-Class, International, and National athletes performed strength training, plyometrics, and sport-specific technical skills with proper equipment, than State/Recreational athletes. More females (42%) sourced training materials from social media than males (29%). Some athletes (38%) performed injury prevention exercises; 18% had mild injuries (knees 29%, ankles 26%), and 18% received a medical diagnosis (International 31%). Lower-level athletes (e.g., State 44%) disclosed that they were mentally more vulnerable; and felt more anxious (36% vs. higher-levels 14%–21%). Sleep quality and quantity were “normal” (49% for both), “improved” (35% and 27%), and only 16% and 14% (respectively) stated “worsened” sleep.

Conclusion: Lockdown compromised training-related practices, especially in lower-level athletes. Athletes are in need of assistance with training, and tools to cope with anxiety that should be tailored to individual country requirements during lockdown situations. In particular, goal-driven (even if it is at home) fitness training, psychological, financial, and lifestyle support can be provided to reduce the difficulties associated with lockdowns. Policies and guidelines that facilitate athletes (of all levels) to train regularly during the lockdown should be developed.

Introduction

Almost as soon as the Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic was declared, daily routines of people worldwide including athletes were disrupted. Mandated lockdowns and other measures associated with varying levels of restriction on movement and social interactions (daily living, occupational and physical activity) were imposed across the globe that negatively impacted factors including mental health, sleep patterns, nutritional intake, and fitness levels (Ammar et al., 2020; Trabelsi et al., 2021; Washif et al., 2022b; Romdhani et al., 2022c). Consequently, athletes, from Recreational to World-Class calibre, were forced to alter their training routines (such as training loads and modalities) due to the imposed constraints (Washif et al., 2022e). These constraints necessitated modified training that was often home-based and streamed on the internet (Ammar et al., 2021; Tjønndal, 2022). This online support was especially evident among elite-level athletes (Washif et al., 2022b).

Lockdowns have been reported to be costly for most nations and created a burden for athletes, both physically and mentally. During the lockdown, some countries (such as Sweden) allowed outdoor activities (Carlander et al., 2022); whereas, in contrast, such activity was strictly prohibited in Malaysia (Washif et al., 2021). Thus, athletes in Malaysia, irrespective of their competition classification level (World-Class, International, National, State, Recreational), were confined to training in their homes (Washif et al., 2021). The environmental conditions of the country (hot and humid) may have imposed additional training challenges on the athletes. In addition to these challenges, not all high-level Malaysian athletes received remote training support from their coaches and trainers at the beginning of lockdown training. Logistical constraints and limited resources delayed the implementation of training assistance and athlete support. A large-scale study involving >12,000 athletes with diverse characteristics from 142 countries reported widespread challenges faced by athletes, including disruptions to training and decreased motivation levels among athletes (Washif et al., 2022b). Following this, a study that focused specifically on a sample of elite Malaysian athletes (n = 76) reported negative experiences from mandatory lockdown such as increased mental and emotional stress, fewer nutritional choices, and reduced training motivation (Washif et al., 2021; Washif et al., 2022a). These results are comparable to the conditions faced by South African athletes (Pillay et al., 2020).

Male and female athletes have reported different training experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. Female athletes are inclined to be involved with online training, while male athletes were more likely to participate in virtual sports competitions (Tjønndal, 2022) in their own homes. Virtual sports are based on simulator platforms (digital technology) or a treadmill/bicycle connected to a computer (with screen monitor) that enables actual and live running/pedaling. The objective is to replicate racing realities, hills, headwinds, drafting effects, and/or even online competition with other athletes. Male athletes also appear to have maintained a higher number of weekly training days and hours, to a greater extent than female athletes (Mon-López et al., 2020). As well as differences between gender, differences between sporting types were identified, with sports requiring specialist facilities such as swimming, shooting, archery, and team sports often unable to carry out technical training at training sites (Washif et al., 2022e). However, some athletes were able to perform specific skills or fitness training such as running for endurance athletes, throwing for shot putters, weight training for weightlifters, and continuance of strength development if possessing training equipment at home (Washif et al., 2022b; Meier et al., 2022; Pagaduan et al., 2022).

Sleep quantity and quality are of paramount importance for recovery and performance of the athletes. Reduced training intensity and fewer training sessions result in circadian interference, which negatively impacts sleep quality (Romdhani et al., 2022b) and could potentially trigger mental health issues (Facer-Childs et al., 2021), such as elevated stress and depression (Facer-Childs et al., 2021; Romdhani et al., 2022b). In this context, high intensity training can promote 1) increased sleep drive contributing to improved sleep (Romdhani et al., 2022b) and 2) activation of endogenous opioid release (inside the brain) resulting in mood elevation and stress reduction (Saanijoki et al., 2018). Unfortunately, mental distress and the athletes’ inability to maintain athletic routines have also been associated with an increased injury risk (Wiese-Bjornstal, 2019; Rampinini et al., 2021b). Uncertainty around the resumption of competitions while in lockdown situation, may worsen mood, reduce motivation, and amplify eventual mental health issues (Facer-Childs et al., 2021).

Although some studies have proposed how the lockdown has affected athletes’ training practices, injury prevalence, sleep disorder occurrences, and mental-health-related challenges during the lockdown, patterns of discrepancies between gender (male vs. female), and sport-type (individual vs. team-based sports) require clarification. Currently, very few studies have investigated differences due to athlete classification levels (Mon-López et al., 2020; Pillay et al., 2020). Higher classification-level athletes (i.e., World-Class, International) would likely have higher needs for training equipment, frequency, facilities and intensity than lower classification-level athletes (e.g., State).

The aim of this study was to evaluate training and recovery practices, injury prevalence, mental perspectives, and sleep patterns of athletes in Malaysia during the early stages of lockdown, including changes in key training variables with references to athlete classification level, sport type, and gender. This information will elucidate the effects of lockdown among athletes in Malaysia to develop appropriate mitigation approaches for future lockdowns, and/or challenging lockdown-like situations. We expected that athletes from higher classification levels (e.g., World Class), and individual-based sports, would better maintain key training variables compared to athletes from other classification levels and sports.

Materials and methods

Design

A within-subject, cross-sectional, questionnaire study was conducted 2 months after the country’s announcement of a lockdown, from 17 May–5 July 2020. This study was part of a global survey investigating athletes’ training knowledge, beliefs, and practices during the COVID-19 lockdown (Washif et al., 2022b). Overall data and comparisons for differences according to athlete competition classification level (World-Class, International, National, State, and Recreational), sport-type (individual e.g., athletics, badminton, karate vs. team-based sports e.g., hockey, soccer, rugby), and gender (male vs. female) were made. Sport type comparison excluded parasports given a possible confounding factor in the grouping of para-athletes. Athlete classification was based on their highest competition level e.g., Olympic or world championship representatives or similar caliber athletes were grouped as World-Class; participation at other international-, continental-, regional-, and inter-community competitions as International; participation at national-level competition as National; participation at state-level competition as State; and other non-competitive sports participation, usually for leisure, health, or work-related as Recreational (Washif et al., 2022b; Washif et al., 2022e).

Respondents

Participant eligibility is described elsewhere (Washif et al., 2022b). Briefly, only athletes aged 18 years old or above, and who had not missed training for 7 days or more due to illness and/or injury during the lockdown, were allowed to participate in the survey. These participants provided informed consent prior to participation. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the institutional research committee of Institut Sukan Negara, Malaysia (ISNRP004-21).

Sample size

Taking into account the rate of sports participation (two-thirds of the population) in Malaysia (www.iyres.gov.my), a response distribution of 50% (which maximises sample size), a Z-score or standard deviation of 2.6 (for a 99% confidence interval), and the margin of error of ∼5%, the sample size requirement of 664 athletes was calculated for the current study. A final sample of 686 consenting athletes was subsequently collected and analysed.

Questionnaires

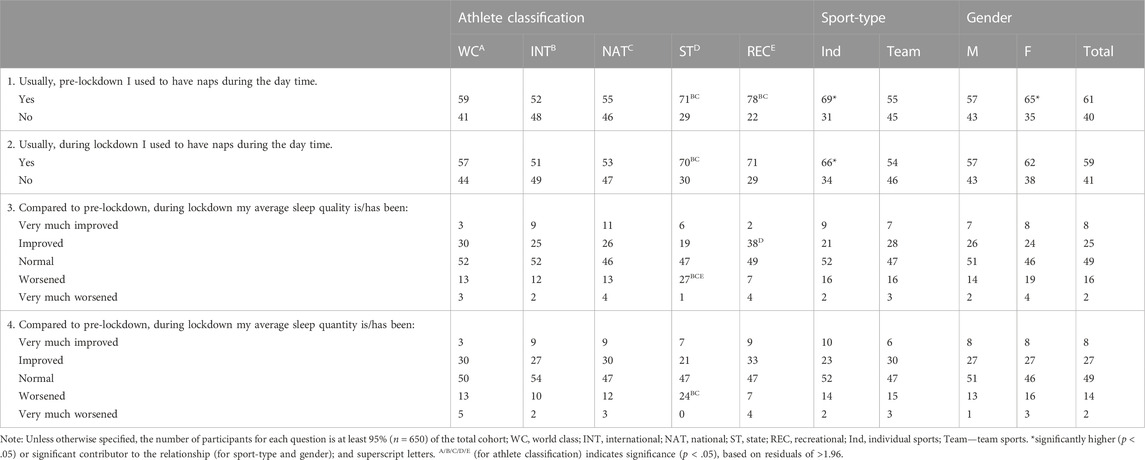

The survey was developed initially by the first (JAW) and last (KC) authors, then reviewed and revised by the wider authorship team, involving >100 researchers from >60 countries. In the present study, questions were partially taken form the global study of Washif et al., 2022b. The socio-demographic section comprised 7 questions; Table 1; Figure 1 (Washif et al., 2022b). The training practice section comprised 11 questions; Table 2, Figures 2, 3, 4 (Washif et al., 2022b). Monitoring, recovery, and injury comprised of 8 questions (Table 3; Figure 5). Psychological responses and financial challenge section comprised 5 questions (Table 4; Figure 6). Sleep habits comprised 4 questions (Table 5). These questions involved: 1) selecting one or more predefined answers; 2) comparing related pre-to during-lockdown effects on training practices; 3) yes or no; and 4) sub-questions including a free-text cell to capture details (Washif et al., 2022b). Responses were carefully screened (e.g., exclusion criteria), cleaned (e.g., removal of duplicates), checked for genuinity, and then converted into standardised codes/numbers to facilitate statistical analysis. Test-retest reliability of the survey was rated as good-excellent (ICCs of >.82).

TABLE 1. Socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents in Malaysia during the 2020 COVID-19 lockdown under a national Movement Control Order (n = 686).

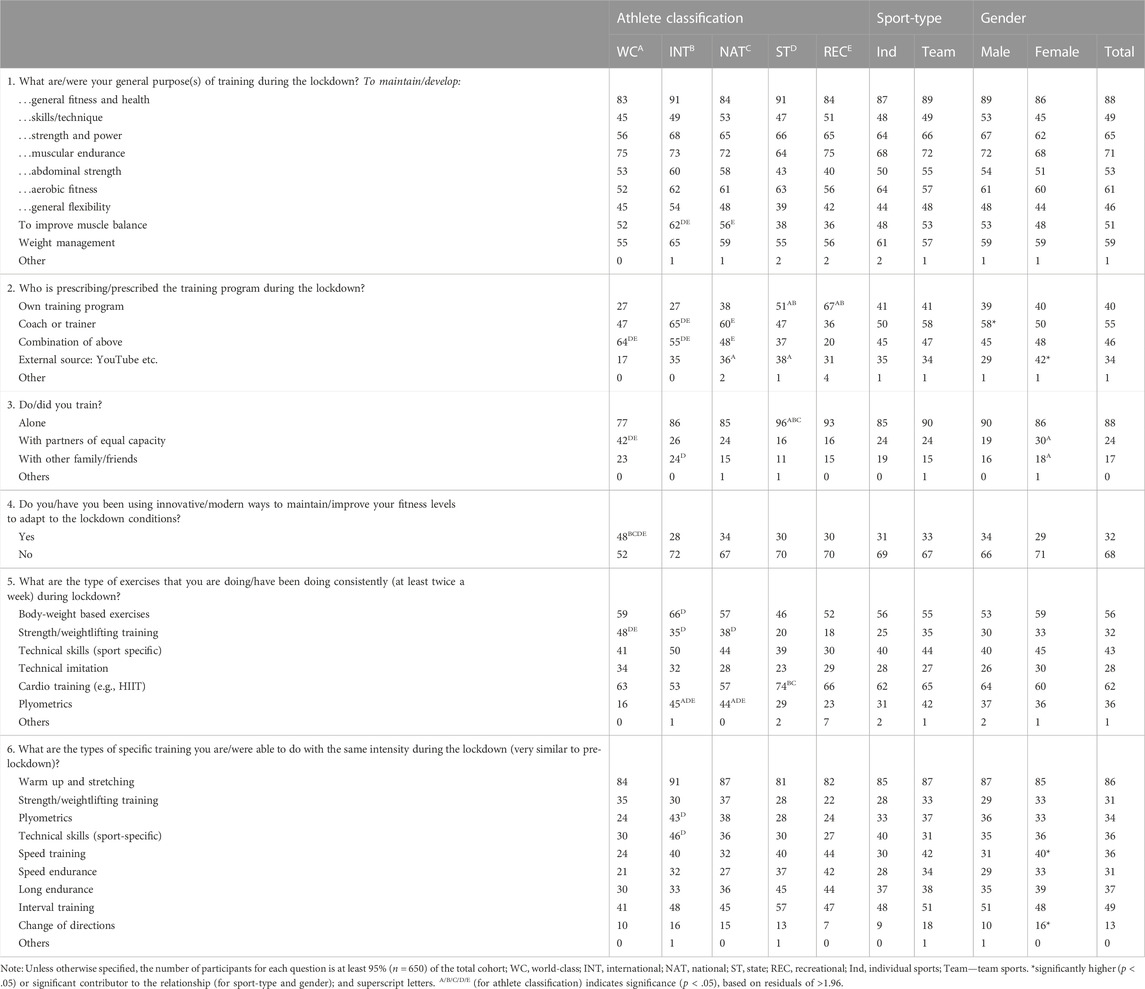

TABLE 2. Training practices during COVID-19 lockdown in Malaysia by athlete classification, sport-type, gender, and total cohort (percentage of respondents).

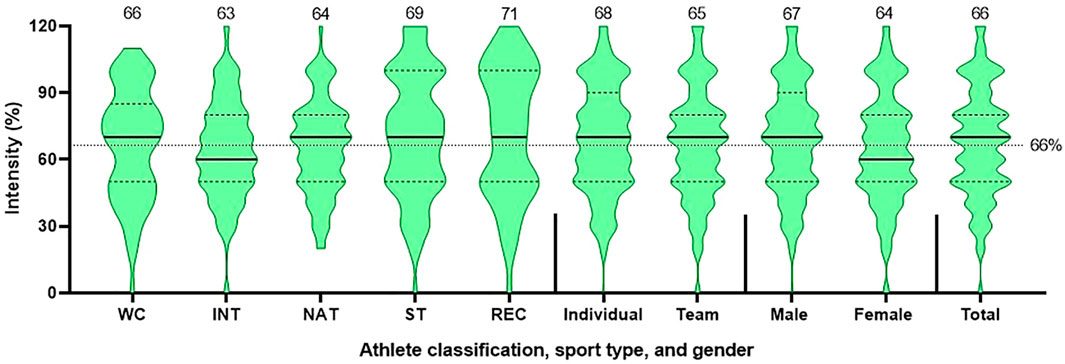

FIGURE 2. Training intensity depicted by athlete classification, sport-type, gender, and total cohort (n = 665). (Question: Do/did you maintain your pre-lockdown intensity for sports specific training (practicing your sport) during the lockdown? Can you estimate how much in percentage? (100% represents the same intensity as before the lockdown). Note: The violin plot includes a 5-point summary, which represents the number in dataset: minimum (lower extreme); 25% percentile (first dashed line/lower quartile); median (black thick line); 75% percentile (second dashed line/third quartile); and maximum (upper extreme). The thin dotted line across all charts/violins represents average intensity.

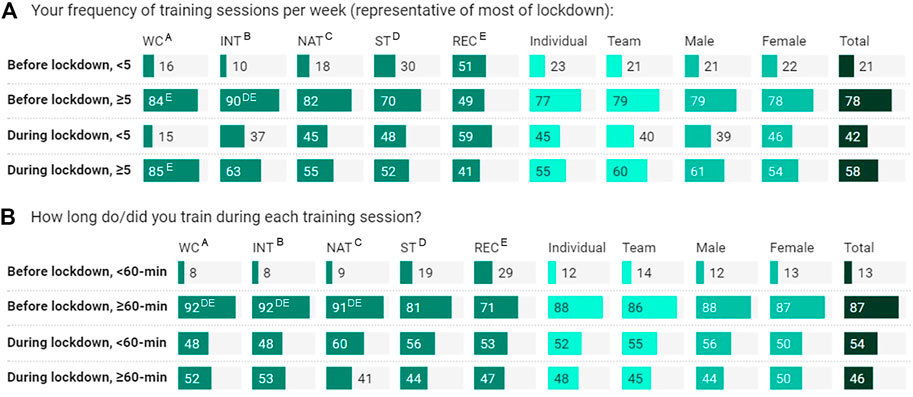

FIGURE 3. Training frequency (< or ≥ 5 sessions/week; (A)) and duration (< or ≥ 60 min/session (B)) based on athlete classification, sport-type, gender, and total cohort, before and during lockdown; data are column % of respondents (n = 661). Percentage, within athlete classification, sport-type, and gender represents “yes” answer, relative to “no” answer. WC, world-class; INT, international; NAT, national; ST, state; REC, recreational. *Significantly higher (or significant contributor to the relationship); superscript letter represents significantly higher than A/B/C/D/E; all at p < .05, based on residuals of >1.96.

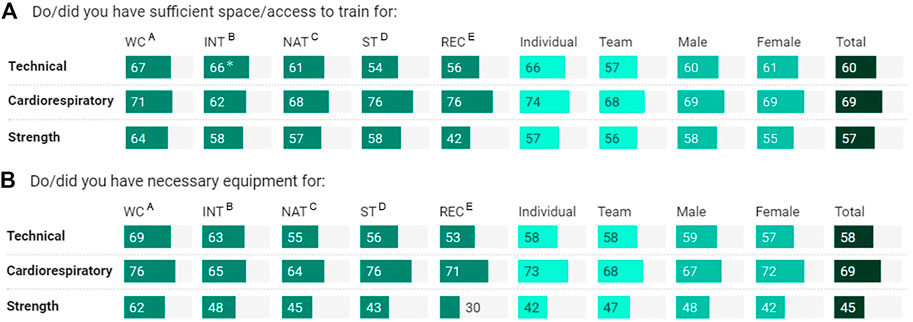

FIGURE 4. Training space/access (A) and equipment (B) for technical, cardiorespiratory, and strength by athlete classification, sport-type, gender, and total cohort (n = 660). Percentage, within athlete classification, sport-type, and gender, represents “yes” answer, relative to “no” answer. WC, world-class; INT, international; NAT, national; ST, state; REC, recreational. *Significantly higher (or significant contributor to the relationship); superscript letter represents significantly higher than A/B/C/D/E; all at p < .05, based on residuals of >1.96.

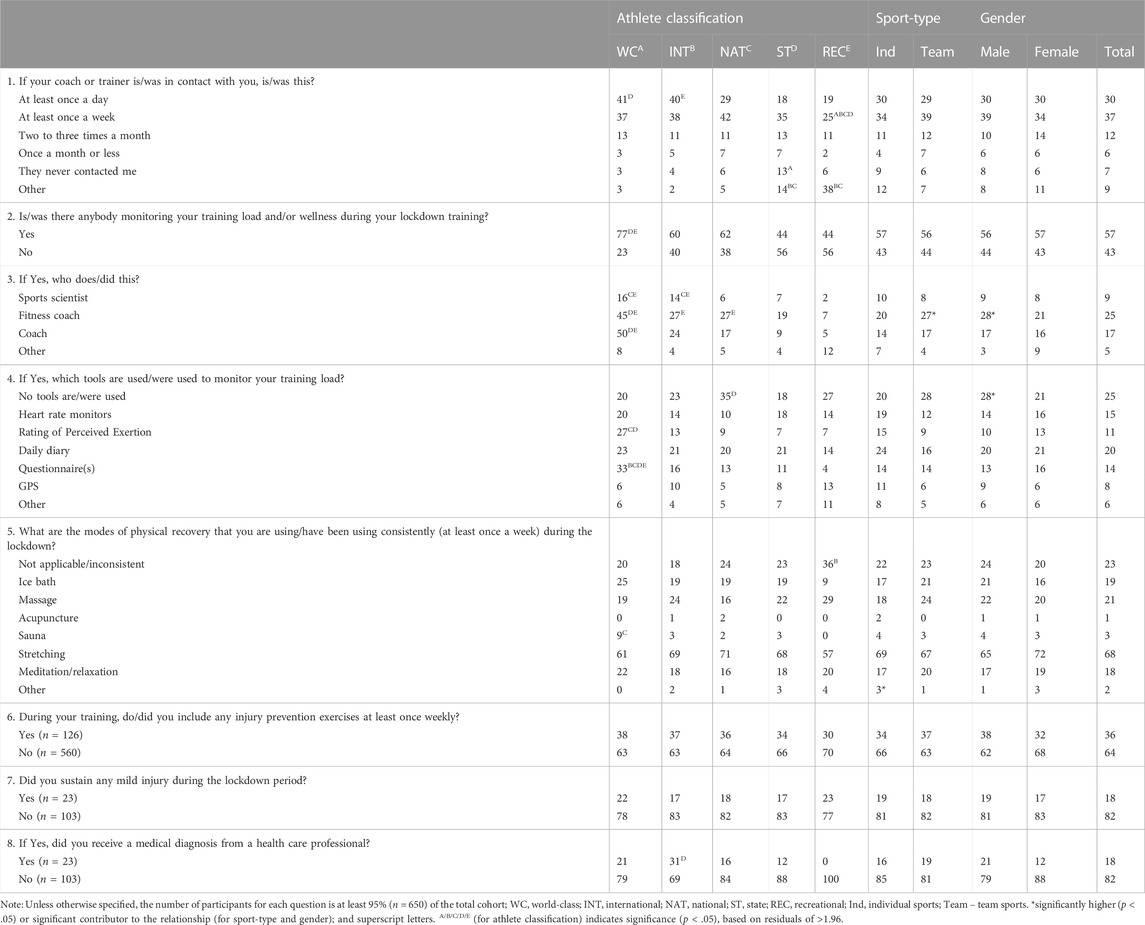

TABLE 3. Monitoring, recovery, and injury by athlete classification, sport-type, gender, and total cohort, during COVID-19 lockdown in Malaysia (percentage of respondents).

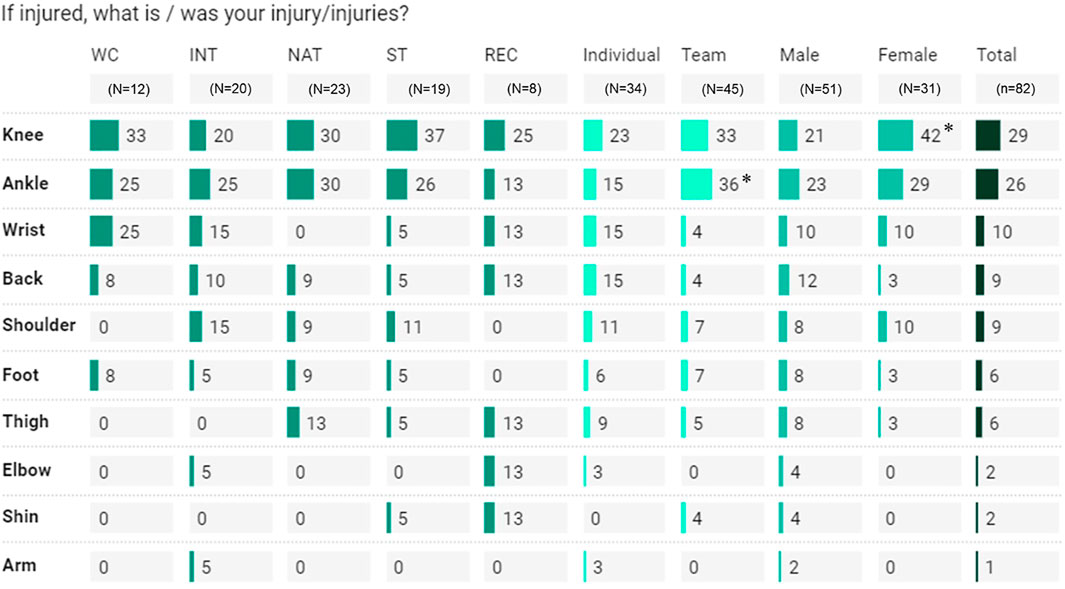

FIGURE 5. Injury prevalence as shown by muscle areas Percentage, within athlete classification, sport-type, and gender, represents “yes” answer, relative to “no” answer. WC, world-class; INT, international; NAT, national; ST, state; REC, recreational. *Significantly higher at p < .05 (within the specific comparative variable).

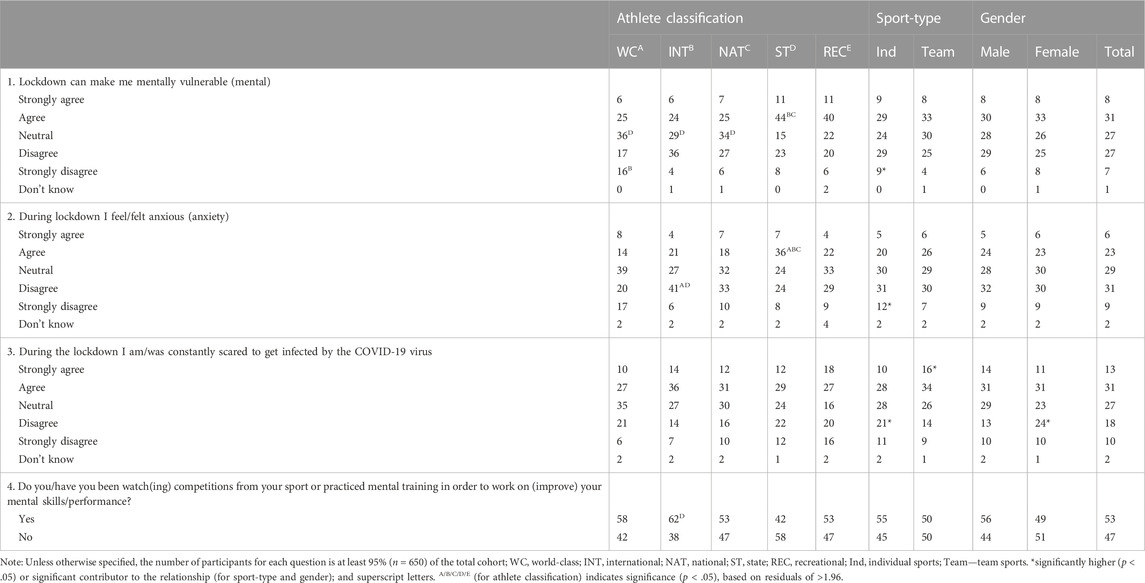

TABLE 4. Athletes’ psychological responses by athlete classification, sport-type, gender, and total cohort, during a COVID-19 lockdown in Malaysia (percentage of respondents).

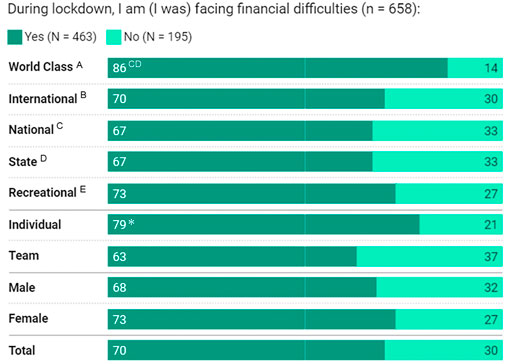

FIGURE 6. Financial challenges during lockdown based on athlete classification, sport-type, gender, and total cohort; data are presented in percentage. CDSignificantly higher than National and State, *significantly higher at p < .05 (within the specific comparative variable).

TABLE 5. Sleep pattern during lockdown in Malaysia based on athlete classification, sport-type, gender, and total cohort (percentage of respondents).

Data collection

The survey was conducted via Google Forms, which was disseminated via e-mail, personal/group messaging applications (e.g., WhatsApp and Telegram) and social media (e.g., Facebook and Twitter) through networks of the research team. All participants were asked to reflect on their “worst experience” of the lockdown (locally known as Movement Control Order) between March and May 2020.

Statistical analysis

All data were analysed using SPSS v.26 (IBM, Chicago, Illinois, United States). Data are presented using a variety of appropriate descriptive statistics, including frequencies, percentages, and mean ± standard deviation. Mean scores (where related) of two factors (gender, and sport type) or more than two (athlete classification) comparators were compared using an independent t-test and one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni adjusted post hoc test, respectively. Contingency tables with Pearson’s chi-squared (χ2) test for independence were utilised to assess the categorical variables. Furthermore, to account for variation due to the sample size (unequal sample size between comparators), adjusted residuals were performed to identify which subsets were significant, or contributed the most (residual greater than 1.96; i.e., significantly higher) or the least (residual less than −1.96; i.e., significantly lower) to the relationships, which corresponds to p < .05. A p-value of <.05 was considered statistically significant. Overall data, as well as differences and/or changes before and during lockdown [i.e., ≥10% (p < .05), or otherwise noted] in variables are highlighted in the Results section. Visualization of datasets (figures) were made using GraphPad Prism (8.0.1) and Datawrapper (Datawrapper GmbH, Berlin, Germany).

Results

Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of athletes in Malaysia (n = 686). Most respondents were male (59%), aged 24.2 ± 7.2 years (18–29 years: 82% of the sample), with competitive experience of 8.1 ± 6.3 years, from 50 sports, mostly athletics (12%). All respondents were of various ethnicities who resided in one of 13 states or 3 Federal Territories in Malaysia (Table 1; Figure 1). During the lockdown, athletes were training at home (74%), with <2% having access to gym facilities. At their homes, para-athletes (43%) received more assistance with training equipment than World-Class (23%), Team (9%) and Endurance (4%) athletes.

Training practices of athletes are shown in Table 2. Athletes trained for general strength and health (88%), and muscular endurance (71%). More International- (62%) and National-level (56%) athletes than recreational athletes (36%) dedicated time to improving muscle balance. More females (42%) than males (29%) sourced training materials from social media (e.g., YouTube). More World-Class (64%) and International (55%) athletes received training programs from coaches, or from coaches combined with their own programs (65% in Internationals). More females (30%) than males (19%) trained with partners of equal capacity (fitness), and similarly for World-Class (42%) compared to State and Recreational athletes (16%). More State athletes were training alone (96%) compared to higher classification-level counterparts (≤86%). As part of lockdown training, more World-Class (48%) than lower classification-level athletes (≤34%) used innovative/modern training modalities (e.g., digital based, Avatars, Zwift racing) to maintain/improve fitness. A greater proportion of higher classification-level (especially World Class athletes, 48%) athletes performed weightlifting/strength training than State athletes (20%). More International (45%) and National (44%) athletes performed plyometric training than the other athlete classifications. Also, more International athletes performed plyometrics (43%) and sport-specific technical skills (46%) than others (Table 2).

Changes in training intensity (Figure 2), frequency, and duration are shown in Figure 3. Overall, the training intensity of sport-specific training during lockdown was approximately 66% of pre-lockdown levels, without a marked difference among the comparators (Figures 2, 3). There was a ∼20% reduction in athletes who trained ≥5 sessions/week, during lockdown. World-Class athletes had similar training frequencies pre- and during-lockdown (84% vs. 85%). Training duration of all athletes was reduced (24%–59%), especially the National (50%), International (39%) and World-Class (40%) athletes. In terms of training space and equipment (Figure 4), athletes had less training space/access (69%), including equipment (69%), for cardiorespiratory training, which was more available for technical and strength training (Figure 4). More World-Class athletes (62%) had greater access to necessary equipment for strength training than the other classifications (<50%) (Figure 4).

Athletes’ monitoring, recovery, and injury prevalence are shown in Table 3; Figure 5. During lockdown, contact with a coach/trainer at least once per day occurred more among World-Class (41%) and International (40%) than State (18%) and Recreational (19%) athletes. A large number of World-Class athletes monitored training load (77%) than other athletes. Training monitoring by fitness coaches occurred more commonly among World-Class athletes (45%), than State (19%) and Recreational (7%) athletes. World-Class athletes had their training loads monitored mostly via questionnaire (33%) and RPE (27%) scales/methods. One main mode of physical recovery, which was similar across all comparative variables, was stretching (68%). Overall, 38% of athletes included injury prevention exercises (e.g., stretching, stability, mobility, flexibility) and 18% reported experiencing mild injury. Of these, 18% (across all athletes) received a medical diagnosis, mostly among International athletes (31%). The reported injuries (n = 82) were mostly related to the knee (29%) and ankle (26%) (Figure 5).

Psychological and financial status of athletes are shown in Table 4; Figure 6. Lower classification athletes, especially State (44%) athletes agreed that the mandated lockdown increased feelings of mental vulnerability. More of these athletes (36%) also agreed feeling anxious during lockdown, compared to higher classification-level athletes (14%–21%). A greater proportion of higher classification-level athletes, especially International (62%) compared to State athletes (42%), developed their mental skills/performance by watching competitions or practising mental training. More Individual-sport (79%) than team-sport (63%) athletes experienced financial difficulty during lockdown, as well as World-Class athletes (86%) compared to National and State athletes (both 67%) (Figure 6).

Sleep pattern data during lockdown is shown in Table 5. Lower-classification athletes practised power naps during the daytime, both before (State 71%, Recreational 78%) and during lockdown (70% and 71%, respectively). More athletes indicated that their sleep quality was “normal” (49%) and improved (35%), than those who reporting “worsened” sleep (16%). Similarly, for sleep quantity, 49% of respondents indicated normal, 27% improved, and 14% worsened. State athletes typically had inferior sleep quality (27%) and quantity (24%) (Table 5).

Discussion

Key training variables of athletes from Malaysia were substantially altered during the mandated COVID-19 lockdown, especially for different classification athletes (World-Class, National, State, and Recreational). Despite the observed overall reduction in training frequency, the proportion of World-Class athletes training at least five times weekly during lockdown was preserved. This group, and other athletes, however, reduced their training duration per session, training intensity (during sport-specific training), and performed alternative training modes. Most athletes aimed to maintain or develop general strength and health, and muscular endurance, utilising body-weight-based exercises. Interestingly, most of higher classification-level athletes (World-Class, International) received their training programs from coaches, using innovative/modern methods (e.g., digital-based), with more opportunities to perform weightlifting/strength (proper equipment), plyometrics, and sport-specific technical skills than lower classification-level athletes. Higher classification-level athletes had regular contact with coaches/trainers, which facilitated their training monitoring. Even though some athletes practised injury prevention exercises, ∼18% reported suffering from a mild injury (e.g., knees and ankles) during the lockdown. These findings indicate that athletes, coaches, and support staff need logistical support that facilitates training in a lockdown situation.

Athletes reported that lockdown situations made them mentally more vulnerable, along with increased anxiety feeling, especially the lower classification-level athletes, regardless of sport type (individual or team) or gender. Higher classification-level athletes (e.g., International) spent more time training mental skills/performance by watching competitions or undertaking mental training. Interestingly, sleep patterns were generally unaffected as more athletes indicated sleep quality and quantity to be “normal” or “improved” during lockdown compared to pre-lockdown. Conversely, “worsened” sleep was reported among lower classification-level (State) athletes. The majority of athletes reported financial difficulties, especially among individual sports, and World-Class athletes. During lockdown situations, decisive efforts to scale-up assistance (e.g., physical, mental and wellbeing related support) are necessary, e.g., put into place measures that facilitate the training (even if quarantine- or home-based) and protect the wellbeing (including mental and finance related support) of athletes.

Home/modified training (in a lockdown context) appeared to compromise weekly training frequency, intensity of sport-specific training, and session duration. These negative impacts in training variables are likely associated with facility limitations, e.g., limited availability of training space and equipment, as reported among athletes in many other countries worldwide (Pillay et al., 2020; Washif et al., 2022b; Pagaduan et al., 2022). A similar proportion of World-Class athletes (∼86%) maintained their pre- and during-lockdown training frequency of ≥5 times per week. When lockdowns were instigated, many World-Class athletes were already in their preparation for major competitions (e.g., Olympic Games, World cups, and international tours), and endeavoured to practice “everyday”. Some of these athletes also received/bought new equipment, further enabling this training consistency/maintenance (Washif et al., 2022b; Meier et al., 2022). During lockdown, home-based or modified training (i.e., bodyweight-based) widely replaced the traditional resistance training, which is similar to the changes reported in our global study (Washif et al., 2022b). It is reasonable to surmise that these changes were responsible for the 35% reduction in training intensity in the current study. An important caveat is that training intensity is a key component required to preserve fitness (Mujika, 2010), including endurance and strength performance (Izquierdo et al., 2007; Mujika, 2010; McMaster et al., 2013; Spiering et al., 2021). It is important that a decrease in strength level may be observed after a 3-week cessation of resistance training, and exacerbated after ≥5 weeks (McMaster et al., 2013). It would seem that athletes in Malaysia preserved their weekly training frequency (especially the World-Class cohort) when other key training variables (e.g., duration, intensity) were compromised.

Training duration (volume) is crucial among athletes requiring a high level of endurance. We observed that ∼41% of athletes maintained a training duration of ≥60 min (per session), during the lockdown. A similar proportion of athletes training at shorter duration of 30 to ≤60 min (∼43%) or at ≥60 min (46%) during lockdown, globally (Washif et al., 2022b). In this context, a weekly training volume of ∼380 min (4–5 sessions/week) can improve aerobic fitness and maintain muscular power of soccer players (Rampinini et al., 2021a). Essentially, athletes who were in possession of a home treadmill or a bike would be the least affected by the lockdown situations. This group of athletes appeared to preserve the majority of specific training they performed daily (Washif et al., 2022b). In particular, a previous study reported that endurance runners (especially top-level athletes) predominantly undertake low-intensity, long-duration training, with the addition of highly intensive bouts (Seiler, 2010). Meanwhile, a review of 9 studies (in team sports players) described the typical home training comprising of an average ∼5 ± 2 weekly training sessions, with a session duration of ∼45–90 min (Paludo et al., 2022). The latter authors reported VO2max changes from +6% to -9% (highly variable results), increased sprint times (.4%–36%) reflective of poorer sprint performance; and changes in countermovement jump height (−5% to +15%) after home/modified training that focused on muscular strength and endurance (Paludo et al., 2022). Furthermore, with similar training focuses, minor changes were reported in reactive agility performance of −12% (Pucsok et al., 2021), and one-repetition maximum strength of −3% (Pedersen et al., 2021). It appears there are highly variable between-athlete changes in physiological and performance changes due to the COVID-19 lockdowns (Paludo et al., 2022).

During the Malaysian lockdown, athletes modified their training aims, and mostly trained for general strength and health, and muscular endurance. It is important that the prevalence of athletes training for muscular endurance was relatively higher (71% vs. 55%) than that reported in a global study (Washif et al., 2022b). These changes were associated with restrictions during the lockdown, further reducing training specificity (e.g., different training modes/types). It is important that, unlike the “transition phase,” “altered training” during lockdown is usually designed to limit detraining effects i.e., to maintain or even improve performance (Washif et al., 2022c). This approach can be facilitated by regular contact with coaches/trainers, i.e., training monitoring (e.g., loading regulation) and prescriptions (e.g., training programs); for athletes to perform an appropriate training program that permits adaptation while reducing the risk of “overreaching” and injury. In the current study, such provisions were seen more often among higher classification-level athletes (i.e., World-Class, International). According to a recent study, World-Class athletes were the least to adopt a self-designed training routine, since they received the greatest support from their coaching team (Pagaduan et al., 2022). Indeed, a structured home-based training program during the COVID-19 lockdown preserved lower limb explosive strength (Font et al., 2021). Additionally, a 3-month period of home-based and group-based interventions (mainly for strength, jump, and sprints) during lockdown was effective for maintaining strength, jumping, and sprinting ability among high-level female football players (Pedersen et al., 2021). In the case of facing limited resources (lockdown situation), a tailor-made home-based exercise program (typically bodyweight-based; Yousfi et al., 2020) not only ensures regular and consistent training, but helps promote health-related benefits (mental, emotional, and physical). Further, athletes may take advantage of the hot and humid conditions (e.g., Malaysia), and use clothing/garments that restrict heat loss while training at home as a means to ‘heat up’ the body temperature and heart rate to boost metabolic responses (Willmott et al., 2018). Even though beneficial for fitness maintenance (or improvement), the safety ramifications of home-based and modified training have not been assured (Washif et al., 2022b). In the current study, ∼18% of athletes reported a mild injury, mostly knee and ankle injuries, irrespective of sports, gender, and level of athletes, despite ∼36% of the athletes implementing injury prevention exercises as part of their training at home. These phenomena could be as a result of the abrupt resumption of high-intensity training to be ready for the competitions after lockdown (Bazett-Jones et al., 2020; DeJong et al., 2021).

Remote conditioning training aims at maintaining some level of training and preserving some social connections. Collaterally, decreases in training were linked with higher depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms during the COVID-19 lockdown (Facer-Childs, et al., 2021). Some elite athletes reported psychological distress due to training cessation during lockdown (di Cagno et al., 2020; Jia et al., 2022; Venturelli et al., 2022), changes in sleep (Facer-Childs et al., 2021; Romdhani et al., 2022b), financial problems, among others. In the current study, the majority of athletes reported financial difficulties, especially among individual-sport, and World-Class athletes; an extra stressor that potentially impacted the athletes’ mental health (Busch et al., 2022). Individual and team-based sports obtained mixed results with both categories indicating increased risks for poor mental and emotional health (Jia et al., 2022). In professional football, the prevalence of anxiety (8%–18% in females) and depression (6%–13% in males) increased during the COVID-19 lockdown (Gouttebarge et al., 2022). Athletes in the present study, especially the lower classification-levels, reported that they felt mentally vulnerable, and similarly, had increased anxiety levels. Such observations may relate to reduced or missing interactions with teammates, including “online team training” that was also limited among lower classification-level athletes, as shown in the current study. In contrast, higher classification-level athletes might have adequate (more) social support and/or connections (e.g., during “online training” sessions), with some athletes practising their mental skills to improve their mental status. Concomitantly, mental health was associated with lockdown-induced sleep pattern changes (i.e., increased total sleep time and sleep latency) (Facer-Childs et al., 2021). In the current study, sleep patterns were generally unaffected as more athletes indicated that their sleep quality and quantity were “normal”, and for some sleep was “improved” during the lockdown. However, relatively poorer sleep patterns were reported among lower classification-level (State) athletes. We are unable to directly identify what caused the worsening of sleep in the lower classification-level athletes, but it can likely be attributed to several factors, including financial difficulties and/or reduced social connections during training.

To our knowledge, only a few country-specific studies have investigated training practices, recovery, sleep, mental, and injury prevalence of athletes for different classification athletes (recreational to World-Class levels), different sports, and gender. Here we report the results of athletes from 50 sports (individual and team). However, this study is not without limitations. Subjective questionnaires were used to obtain responses from participants retrospectively and therefore subject to recall bias. Here we considered a convenience sampling approach that limits the generalisability of our findings. Furthermore, a qualitative analysis through interviews might address more detailed (or specific) issues of athletes from a different perspective of performance; whereas questionnaires we used were specific to our objectives, albeit checked and verified by a large number of researchers and scientists including experts (e.g., in sports performance, periodisation, detraining, recovery, sleep, psychology, injury, among others). Ramadan fasting occurred in the early the lockdown, and might have impacted on the results (Romdhani et al., 2022a), which we addressed elsewhere (Washif et al., 2022d). Moreover, data concerning injury prevalence is only specific to athletes with acute mild (light) injury as we did not consider the participation (survey) of athletes having moderate or severe injuries, which further limits the conclusions regarding injury prevalence during the lockdown.

Conclusion

The early mandated COVID-19 lockdown in Malaysia (2020) induced more severe effects on the training-related practices of lower classification-level athletes. World-Class athletes experienced the fewest effects on training-related issues (e.g., training programs, sport-specific training, monitoring, and equipment). Overall, the key training variables of frequency, intensity, duration, and modes were compromised. During the lockdown, athletes focused more on preserving (or possibly enhancing) general strength and health, with an emphasis on muscular endurance given high accessibility to bodyweight-based related exercises. Some other exercises (e.g., plyometrics) were emphasised and their use was mediated by athlete classification level. Training at home (including modified training) was associated with safety considerations, as a substantial proportion of athletes reported having had mild “injuries” during the lockdown. Recognising the associated challenges, a one-size-fits-all program may not be ideal during lockdowns. Thus, we recommend objective-driven country-specific support to athletes; possibly implemented as home-based support e.g., fitness training, psychology, financial, and lifestyle. It might be necessary to consider an arrangement that permits “bubble training/competition” to reduce lockdown-associated challenges, and facilitate regular training during the lockdown, not only for high classification-level athletes, but also State- and/or National-level athletes.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by National Sports Institute of Malaysia. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

The study was designed by all authors. All authors involved in the survey development. JW, L-YK, and CJ involved in data collection. JW and AF performed the statistical analysis. JW prepared the first draft. The manuscript was critically revised by all authors. All authors approved the manuscript’s final version.

Funding

The publication of this study was funded by the National Sports Institute of Malaysia.

Acknowledgments

The ECBATA (Effects of Confinement on knowledge, Beliefs/Attitudes, and Training in Athletes) COVID-19 consortium sincerely thank all of those who supported this project, especially the athletes (respondents), individuals (friends/colleagues) and sports organisations in Malaysia for disseminations of survey. We would like to thank other ECBATA_COVID-19 members who helped with different aspects of the survey/project.

Conflict of interest

Author CJ is employed by Hong Kong Sports Institute Ltd.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Ammar A., Mueller P., Trabelsi K., Chtourou H., Boukhris O., Masmoudi L., et al. (2020). Psychological consequences of COVID-19 home confinement: The ECLB-COVID19 multicenter study. PLoS One 15 (11), e0240204. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0240204

Ammar A., Trabelsi K., Brach M., Chtourou H., Boukhris O., Masmoudi L., et al. (2021). Effects of home confinement on mental health and lifestyle behaviours during the COVID-19 outbreak: Insight from the ECLB-COVID19 multicenter study. Biol. Sport. 38 (1), 9–21. doi:10.5114/biolsport.2020.96857

Bazett-Jones D. M., Garcia M. C., Taylor-Haas J. A., Long J. T., Rauh M. J., Paterno M. V., et al. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 social distancing restrictions on training habits, injury, and care seeking behavior in youth long-distance runners. Front. Sports Act. Living. 11 (2), 586141. doi:10.3389/fspor.2020.586141

Busch A., Kubosch E. J., Bendau A., Leonhart R., Meidl V., Bretthauer B., et al. (2022). Mental health in German paralympic athletes during the 1st year of the COVID-19 pandemic compared to a general population sample. Front. Sports Act. Living. 14 (4), 870692. doi:10.3389/fspor.2022.870692

Carlander A., Lekander M., Asmundson G. J. G., Taylor S., Olofsson Bagge R., Lindqvist Bagge A. S. (2022). COVID-19 related distress in the Swedish population: Validation of the Swedish version of the COVID Stress Scales (CSS). PLoS One 17 (2), e0263888. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0263888

DeJong A. F., Fish P. N., Hertel J. (2021). Running behaviors, motivations, and injury risk during the COVID-19 pandemic: A survey of 1147 runners. PloS One 16 (2), e0246300. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0246300

di Cagno A., Buonsenso A., Baralla F., Grazioli E., Di Martino G., Lecce E., et al. (2020). Psychological impact of the quarantine-induced stress during the coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak among Italian athletes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 17 (23), 8867. doi:10.3390/ijerph17238867

Facer-Childs E. R., Hoffman D., Tran J. N., Drummond S. P. A., Rajaratnam S. M. W. (2021). Sleep and mental health in athletes during COVID-19 lockdown. Sleep 44 (5), zsaa261. doi:10.1093/sleep/zsaa261

Font R., Irurtia A., Gutierrez J. A., Salal S., Vila E., Carmona G. (2021). The effects of COVID-19 lockdown on jumping performance and aerobic capacity in elite handball players. Biol. Sport 38 (4), 753–759. doi:10.5114/biolsport.2021.109952

Gouttebarge V., Ahmad I., Mountjoy M., Rice S., Kerkhoffs G. (2022). Anxiety and depressive symptoms during the COVID-19 emergency period: A comparative cross-sectional study in professional football. Clin. J. Sport Med. 32, 21–27. doi:10.1097/JSM.0000000000000886

Izquierdo M., Ibañez J., González-Badillo J. J., Ratamess N. A., Kraemer W. J., Häkkinen K., et al. (2007). Detraining and tapering effects on hormonal responses and strength performance. J. Strength Cond. Res. 21 (3), 768–775. doi:10.1519/R-21136.1

Jia L., Carter M. V., Cusano A., Li X., Kelly J. D., Bartley J. D., et al. (2022). The effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental and emotional health of athletes: A systematic review. Am. J. Sports Med. 12, 036354652210874. doi:10.1177/03635465221087473

McMaster D. T., Gill N., Cronin J., McGuigan M. (2013). The development, retention and decay rates of strength and power in elite rugby union, rugby league and American football: A systematic review. Sports Med. 43, 367–384. doi:10.1007/s40279-013-0031-3

Meier N., Nägler T., Wald R., Schmidt A. (2022). Purchasing behavior and use of digital sports offers by CrossFit® and weightlifting athletes during the first SARS-CoV-2 lockdown in Germany. BMC Sports Sci. Med. Rehabil. 14, 44. doi:10.1186/s13102-022-00436-y

Mon-López D., de la Rubia Riaza A., Galán M. H., Roman I. R. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 and the effect of psychological factors on training conditions of handball players. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 17 (18), 6471. doi:10.3390/ijerph17186471

Mujika I. (2010). Intense training: the key to optimal performance before and during the taper. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 20, 24–31. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0838.2010.01189.x

Pagaduan J. C., Washif J. A., Krug I., Ammar A., Ben Saad H., James C., et al. (2022). Training practices of Filipino athletes during the early COVID-19 lockdown. Kinesiology 54 (2), 335–346. doi:10.26582/k.54.2.15

Paludo A. C., Karpinski K., Silva S. E., Kumstát M., Sajdlová Z., Milanovic Z. (2022). Effect of home training during the COVID-19 lockdown on physical performance and perceptual responses of team-sport athletes: A mini-review. Biol. Sport. 39 (4), 1095–1102. doi:10.5114/biolsport.2022.117040

Pedersen S., Johansen D., Casolo A., Randers M. B., Sagelv E. H., Welde B., et al. (2021). Maximal strength, sprint, and jump performance in high-level female football players are maintained with a customized training program during the COVID-19 lockdown. Front. Physiol. 12, 623885. doi:10.3389/fphys.2021.623885

Pillay L., van Rensburg D. C., van Rensburg A. J., Ramagole D. A., Holtzhausen L., Dijkstra H. P., et al. (2020). Nowhere to hide: The significant impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) measures on elite and semi-elite South African athletes. J. Sci. Med. Sport. 23 (7), 670–679. doi:10.1016/j.jsams.2020.05.016

Pucsok J. M., Kovács M., Ráthonyi G., Pocsai B., Balogh L. (2021). The impact of Covid-19 lockdown on agility, explosive power, and speed-endurance capacity in youth soccer players. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 18, 9604. doi:10.3390/ijerph18189604

Rampinini E., Donghi F., Martin M., Bosio A., Riggio M., Maffiuletti N. A. (2021a). Impact of COVID-19 lockdown on Serie A soccer players’ physical qualities. Int. J. Sports Med. 42 (10), 917–923. doi:10.1055/a-1345-9262

Rampinini E., Martin M., Bosio A., Donghi F., Carlomagno D., Riggio M., et al. (2021b). Impact of COVID-19 lockdown on professional soccer players' match physical activities. Sci. Med. Footb. 5 (S1), 44–52. doi:10.1080/24733938.2021.1995033

Romdhani M., Ammar A., Trabelsi K., Chtourou H., Vitale J. A., Masmoudi L., et al. (2022a). Ramadan observance exacerbated the negative effects of COVID-19 lockdown on sleep and training behaviors: A international survey on 1, 681 muslim athletes. Front. Nutr. 9, 925092. doi:10.3389/fnut.2022.925092

Romdhani M., Fullagar H. H. K., Vitale J. A., Nédélec M., Rae D. E., Ammar A., et al. (2022b). Lockdown duration and training intensity affect sleep behavior in an international sample of 1, 454 elite athletes. Front. Physiol. 13, 904778. doi:10.3389/fphys.2022.904778

Romdhani M., Rae D. E., Nédélec M., Ammar A., Chtourou H., Al Horani R., et al. (2022c). COVID-19 lockdowns: A worldwide survey of circadian rhythms and sleep quality in 3911 athletes from 49 countries, with data-driven recommendations. Sports Med. 52 (6), 1433–1448. doi:10.1007/s40279-021-01601-y

Saanijoki T., Tuominen L., Tuulari J., Nummenmaa L., Arponen E., Kalliokoski K., et al. (2018). Opioid release after high-intensity interval training in healthy human subjects. Neuropsychopharmacol 43, 246–254. doi:10.1038/npp.2017.148

Seiler S. (2010). What is best practice for training intensity and duration distribution in endurance athletes? Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 5 (3), 276–291. doi:10.1123/ijspp.5.3.276

Spiering B. A., Mujika I., Sharp M. A., Foulis S. A. (2021). Maintaining physical performance: The minimal dose of exercise needed to preserve endurance and strength over time. J. Strength Cond. Res. 35 (5), 1449–1458. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000003964

Tjønndal A. (2022). The impact of COVID-19 lockdowns on Norwegian athletes’ training habits and their use of digital technology for training and competition purposes. Sport Soc. 25 (7), 1373–1387. doi:10.1080/17430437.2021.2016701

Trabelsi K., Ammar A., Masmoudi L., Boukhris O., Chtourou H., Bouaziz B., et al. (2021). Globally altered sleep patterns and physical activity levels by confinement in 5056 individuals: ECLB COVID-19 international online survey. Biol. Sport 38 (4), 495–506. doi:10.5114/biolsport.2021.101605

Venturelli M., Mancini A., Di Cagno A., Fiorilli G., Paneroni M., Roggio F., et al. (2022). Adapted physical activity in subjects and athletes recovering from Covid-19: A position statement of the società italiana scienze motorie e sportive. Sport Sci. Health. 18, 659–669. doi:10.1007/s11332-022-00951-y

Washif J. A., Ammar A., Trabelsi K., Chamari K., Chong C. S. M., Mohd Kassim S. F. A., et al. (2022a). Regression analysis of perceived stress among elite athletes from changes in diet, routine and well-being: Effects of the COVID-19 lockdown and “bubble” training camps. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 19 (1), 402. doi:10.3390/ijerph19010402

Washif J. A., Farooq A., Krug I., Pyne D. B., Verhagen E., Taylor L., et al. (2022b). Training during the COVID-19 lockdown: Knowledge, beliefs, and practices of 12, 526 athletes from 142 countries and six continents. Sports Med. 52 (4), 933–948. doi:10.1007/s40279-021-01573-z

Washif J. A., Mohd Kassim S. F. A., Lew P. C. F., Chong C. S. M., James C. (2021). Athlete’s perceptions of a “quarantine” training camp during the COVID-19 lockdown. Front. Sports Act. Living. 2, 622858. doi:10.3389/fspor.2020.622858

Washif J. A., Mujika I., DeLang M., Brito J., Dellal H. T. (2022c). Training practices of football players during the early COVID-19 lockdown worldwide. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 1, 1–10. doi:10.1123/ijspp.2022-0186

Washif J. A., Pyne D. B., Sandbakk O., Trabelsi K., Aziz A. R., Beaven C. M., et al. (2022d). Ramadan intermittent fasting induced poorer training practices during the COVID-19 lockdown: A global cross-sectional study with 5529 athletes from 110 countries. Biol. Sport. 39 (4), 1103–1115. doi:10.5114/biolsport.2022.117576

Washif J. A., Sandbakk Ø., Seiler S., Haugen T., Farooq A., Quarrie K., et al. (2022e). COVID-19 lockdown: A global study investigating the effect of athletes’ sport classification and sex on training practices. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 8, 1242–1256. doi:10.1123/ijspp.2021-0543

Wiese-Bjornstal D. M. (2019). “Psychological predictors and consequences of injuries in sport settings,” in APA handbook of sport and exercise psychology, sport psychology. Editors M. H. Anshel, T. A. Petrie, and J. A. Steinfeldt (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association), 699–725.

Willmott A. G. B., Gibson O. R., James C. A., Hayes M., Maxwell N. S. (2018). Physiological and perceptual responses to exercising in restrictive heat loss attire with use of an upper-body sauna suit in temperate and hot conditions. Temp. (Austin) 5 (2), 162–174. doi:10.1080/23328940.2018.1426949

Keywords: elite athlete, injury, mental health, periodisation, recovery, remote training

Citation: Washif JA, Kok L-Y, James C, Beaven CM, Farooq A, Pyne DB and Chamari K (2023) Athlete level, sport-type, and gender influences on training, mental health, and sleep during the early COVID-19 lockdown in Malaysia. Front. Physiol. 13:1093965. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2022.1093965

Received: 09 November 2022; Accepted: 26 December 2022;

Published: 11 January 2023.

Edited by:

Achraf Ammar, Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz, GermanyReviewed by:

Goran Kuvačić, University of Split, CroatiaDaichi Yamashita, Japan Institute of Sports Sciences, Japan

Copyright © 2023 Washif, Kok, James, Beaven, Farooq, Pyne and Chamari. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jad Adrian Washif, amFkQGlzbi5nb3YubXk=

Jad Adrian Washif

Jad Adrian Washif Lian-Yee Kok2

Lian-Yee Kok2 Carl James

Carl James Christopher Martyn Beaven

Christopher Martyn Beaven Abdulaziz Farooq

Abdulaziz Farooq David B. Pyne

David B. Pyne Karim Chamari

Karim Chamari