94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

BRIEF RESEARCH REPORT article

Front. Physiol., 12 October 2022

Sec. Membrane Physiology and Membrane Biophysics

Volume 13 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2022.1032132

This article is part of the Research TopicThe Role of Calcium and Calcium Binding Proteins in Cell Physiology and DiseaseView all 6 articles

The ryanodine receptor (RyR) is a homotetrameric channel mediating sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ release required for skeletal and cardiac muscle contraction. Mutations in RyR1 and RyR2 lead to life-threatening malignant hyperthermia episodes and ventricular tachycardia, respectively. In this brief report, we use chemical cross-linking to demonstrate that pathogenic RyR1 R163C and RyR2 R169Q mutations reduce N-terminus domain (NTD) tetramerization. Introduction of positively-charged residues (Q168R, M399R) in the NTD-NTD inter-subunit interface normalizes RyR2-R169Q NTD tetramerization. These results indicate that perturbation of NTD-NTD inter-subunit interactions is an underlying molecular mechanism in both RyR1 and RyR2 pathophysiology. Importantly, our data provide proof of concept that stabilization of this critical RyR1/2 structure-function parameter offers clear therapeutic potential.

Myocyte contraction is effected by a transient rise in the intracellular Ca2+ concentration mediated by the ryanodine receptor (RyR), the Ca2+ release channel of the sarcoplasmic reticulum. It is triggered by an action potential that depolarizes the plasma membrane to activate the voltage-gated Ca2+ channel, also known as dihydropyridine receptor (DHPR). In adult mammalian heart, the ensuing small Ca2+ influx activates the RyR to result in a much larger Ca2+ release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ store (Bers, 2002). This process, termed Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release, is also operational in skeletal muscle, but its contribution to contraction of adult mammalian muscles appears negligible (Rios, 2018). Unlike the heart, skeletal muscle is able to contract in the absence of extracellular Ca2+ influx due to physical coupling between DHPR and RyR, where the action potential-evoked conformation change in DHPR is mechanically transmitted to open the RyR (Hernandez-Ochoa and Schneider, 2018). The RyR, a homotetramer of ∼2.2 MDa, is the largest ion channel known to exist (Zissimopoulos and Lai, 2007). There are three mammalian isoforms, RyR1, the predominant type in skeletal muscle, RyR2, the exclusive type in cardiac muscle, and RyR3, which is expressed at low levels in skeletal and smooth muscles. The three RyR isoforms have ∼70% peptide sequence homology and very similar geometry.

Abnormal SR Ca2+ release due to missense mutations in RYR1 and RYR2 results in neuromuscular (e.g., malignant hyperthermia, MH) and cardiac disease (e.g., catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia, CPVT), respectively (Hernandez-Ochoa et al., 2016; Fowler and Zissimopoulos, 2022). Mutations are found throughout the RyR peptide sequence, but tend to concentrate on five structural domains, namely, the N-terminus domain (NTD), bridging solenoid B, core solenoid, transmembrane domain and C-terminus domain (Fowler and Zissimopoulos, 2022). Neighboring NTDs from the four RyR subunits interact with each other to promote channel closure (Tung et al., 2010; Zissimopoulos et al., 2013; Zissimopoulos et al., 2014). Notably, pathogenic RyR1 and RyR2 mutations impair NTD-NTD inter-subunit interactions and result in hyperactive and leaky channels (Iyer et al., 2020; Seidel et al., 2021; Seidel et al., 2015; Xiong et al., 2018; Zheng and Liu, 2017).

The aim of this study was two-fold. First, to empirically assess whether defective RyR1 NTD tetramerization is involved in MH. Second, to explore targeted amino acid modification for potential to restore RyR2 NTD tetramerization in CPVT.

The human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cell line was obtained from ATCC® (CRL-1573), mammalian cell culture reagents from Thermo Scientific, electrophoresis equipment and reagents from Bio-Rad, enhanced chemiluminescence detection kit from Thermo Scientific, mouse anti-cMyc (9E10) from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, goat anti-mouse IgG conjugated with horseradish peroxidase from Abcam, DNA restriction endonucleases from New England Biolabs, Pfu DNA polymerase from Promega, site-directed mutagenesis kit (QuikChange II XL) from Agilent Technologies, oligonucleotides and all other reagents from Sigma.

The plasmids encoding for wild-type rabbit RyR1 and human RyR2 N-terminal constructs tagged with the cMyc epitope at the N-terminus have been described previously (Zissimopoulos et al., 2014; Zissimopoulos et al., 2013). Desired missense mutations were generated using the site-directed mutagenesis QuikChange II XL kit and appropriate primers as recommended by the supplier. All plasmid constructs were verified by direct DNA sequencing.

HEK293 cells were transiently transfected using TurboFect according to the provider’s instructions. 24 h post-transfection, cells were homogenized on ice in homogenization buffer (5 mM HEPES, 0.3 M sucrose, 10 mM DTT, pH 7.4) by 20 passages through a needle (0.6 × 30 mm) and dispersing the cell suspension through half volume of glass beads (425–600 microns). Cell homogenate free of nuclei and heavy protein aggregates was obtained by centrifugation at 1,500 g for 5 min at 4°C, followed by a second centrifugation step at 20,000 x g for 10 min at 4°C. Cell homogenate supernatant (20 μg) was incubated with glutaraldehyde (0.0025% or 260 μmol/L) for the following time-points: 0, 2, 5, 10, 15, 20, 30 and 60 min. The reaction was stopped with the addition of hydrazine (2%) and SDS-PAGE loading buffer (60 mM Tris, 2% SDS, 10% glycerol, 5 mM EDTA, 0.01% bromophenol blue, pH 6.8). Samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with AbcMyc (1:1,000 dilution). Tetramer to monomer ratio was determined by densitometry using a GS-900 Scanner (Bio-Rad) and Image Lab software (Bio-Rad). Tetramer formation was calculated as follows: T = ODT/(ODT + ODM)x100, where ODT and ODM correspond to optical density obtained for tetramer and monomer bands respectively. Statistical analysis was carried out with GraphPad Prism software.

We have previously shown that the CPVT R176Q mutation disrupts NTD tetramerization to produce a hyperactive channel (Seidel et al., 2021). The equivalent residue in human RyR1, R163, is frequently mutated in individuals susceptible to MH. Two different substitutions have been reported, R163C and R163L (Table 1). We chose to study the R163C variant because its gain of function characteristics have been studied extensively in vivo and in vitro (Tong et al., 1997; Avila and Dirksen, 2001; Yang et al., 2003; Yang et al., 2006; Feng et al., 2011; Chen et al., 2018; Iyer et al., 2020).

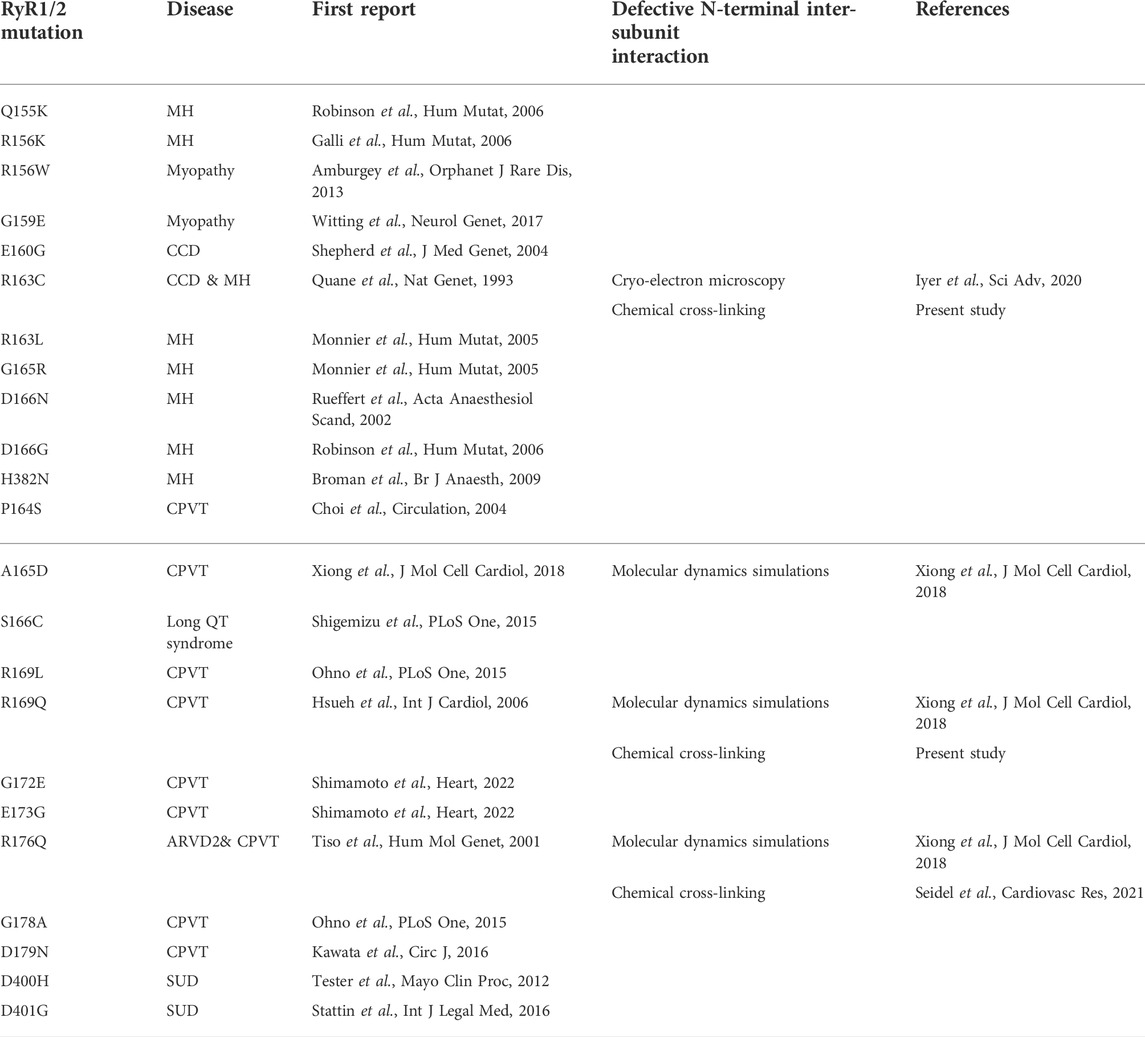

TABLE 1. Evidence for defective N-terminal inter-subunit interactions due to RyR1 (top) and RyR2 (bottom) pathogenic mutations within the β8-β9 and β23-β24 loops (ARVD2: arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia 2, CCD: central core disease, CPVT: catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia, MH: malignant hyperthermia, SUD: sudden unexplained death).

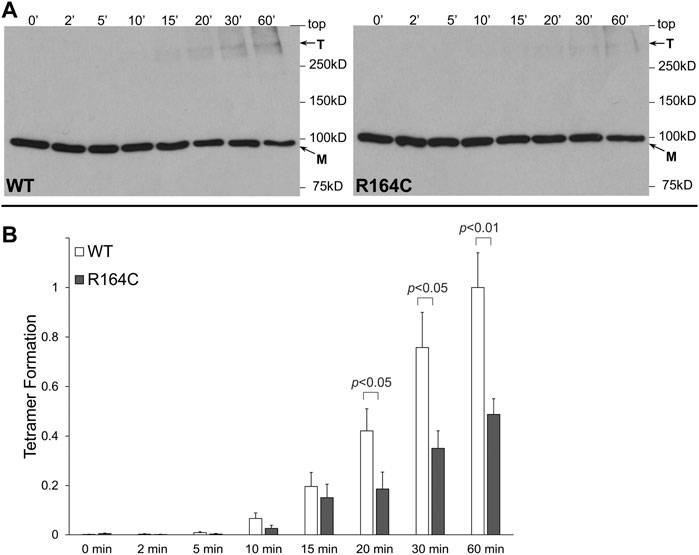

R164C, the corresponding mutation in the rabbit isoform, was introduced by site-directed mutagenesis in rabbit RyR1 N-terminal residues 1–915 tagged with the cMyc peptide epitope (NTRyR1-R164C). NTRyR1−WT and NTRyR1-R164C were expressed in mammalian HEK293 cells with an apparent molecular weight of ∼100 kDa as a monomer (Figure 1A). Chemical cross-linking was carried out using glutaraldehyde, a homo-bi-functional reagent with two aldehyde groups that react with the free amino group in the side chain of lysine residues to create stable covalent bonds. Glutaraldehyde does not induce tetramerization but merely cross-links pre-existing tetramers which could then be preserved despite protein denaturation during SDS-PAGE. Cross-linking of NTRyR1−WT and subsequent Western blotting using AbcMyc revealed the existence of the tetrameric species (Figure 1A), as previously reported (Zissimopoulos et al., 2014). Cross-linking of NTRyR1-R164C also demonstrated the presence of the tetramer, which increased in a time-dependent manner, however its relative abundance was low. Collective data (n = 7) following densitometry analysis indicated that the R164C mutation results in significant reduction (by 51% at 60 min) of the tetramer compared to WT (Figure 1B).

FIGURE 1. MH mutation R164C disrupts RyR1 NTD tetramerization. Chemical cross-linking assays of HEK293 cell homogenates expressing NTRyR1−WT (rabbit RyR1 residues 1–915, cMyc-tagged) or the R164C mutant, NTRyR1-R164C. (A). Cell homogenates were incubated with glutaraldehyde for the indicated time points under reducing (10 mM DTT) conditions and analyzed by Western blotting using AbcMyc; monomer (M) and tetramer (T) are indicated with the arrows. (B). Densitometry analysis was carried out on the bands corresponding to tetramer and monomer moieties and used to calculate tetramer formation. Data (n = 7) are given as mean value ±SEM; statistical analysis was carried out using Mann-Whitney test.

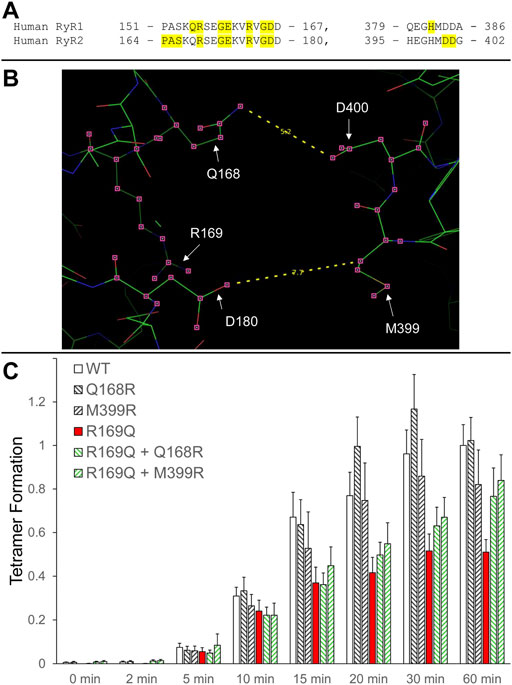

We have previously shown that RyR2 NTD tetramerization is mediated by the interaction between the β8-β9 (amino acids 165–179) and β23-β24 loops (amino acids 395–402) (Seidel et al., 2021) (Figure 2A). The experiments described above with RyR1 R163C as well as those with the equivalent residue in RyR2, R176Q (Seidel et al., 2021), demonstrate the involvement of NTD self-association and specifically, of the β8-β9 loop in RyR1/2 pathophysiology. To extend our findings to other β8-β9 loop CPVT mutations (Table 1), we assessed the impact of R169Q on RyR2 NTD tetramerization.

FIGURE 2. Rescue of defective RyR2 NTD tetramerization in CPVT. (A). Peptide sequence of RyR1/2 β8-β9 (left) and β23-β24 loops (right). RyR1 and RyR2 pathogenic mutations are shaded and listed in Table 1. (B). Image of the RyR2 N-terminal inter-subunit interface generated using PyMol from the RyR2 closed state (5GO9) structure. The location of the CPVT mutation R169Q, as well as residues Q168 and D180 on one subunit that are in close apposition to residues M399 and D400 on the neighboring subunit, are depicted. The Q168-D400 and D180-M399 distances (in Å) are also indicated. (C). Chemical cross-linking assays of NTWT (human RyR2 residues 1–906, cMyc-tagged), NTQ168R, NTM399R, NTR169Q, NTR169Q+Q168R and NTR169Q+M399R expressed in HEK293 cells. Cell homogenates were incubated with glutaraldehyde for the indicated time points under reducing (10 mM DTT) conditions and analyzed by Western blotting using AbcMyc. Densitometry analysis was carried out on the bands corresponding to tetramer and monomer moieties and used to calculate tetramer formation. Data (n ≥ 7) are given as mean value ±SEM.

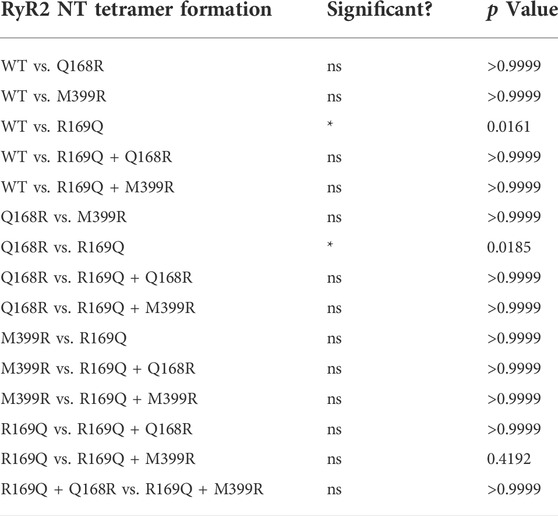

R169Q was introduced by site-directed mutagenesis in human RyR2 N-terminal residues 1–906 tagged with the cMyc peptide epitope (NTR169Q). NTWT and NTR169Q were expressed in mammalian HEK293 cells, subjected to chemical cross-linking using glutaraldehyde, and analyzed by Western blotting using AbcMyc. Both NTWT and NTR169Q were capable of tetramer formation but to quantitatively different extents. Collective data (n ≥ 7) following densitometry analysis indicated that the R169Q mutation results in significant reduction (by 49% at 60 min) of the tetramer compared to WT (Figure 2B; Table 2).

TABLE 2. Chemical cross-linking assays (n ≥ 7) of RyR2 NTWT, NTQ168R, NTM399R, NTR169Q, NTR169Q+Q168R and NTR169Q+M399R as described in the legend to Figure 2. Statistical analysis was carried out for tetramer formation at 60 min of cross-linking using Kruskal–Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparison test.

We next sought to genetically manipulate the RyR2 peptide sequence in order to normalize NTD tetramerization that was impaired by the R169Q mutation. Candidate amino acids are the ones that form the inter-subunit interface between the β8-β9 and β23-β24 loops, as indicated by the recent high-resolution electron cryo-microscopy structures of RyR1/2 in the closed and open configurations (des Georges et al., 2016; Peng et al., 2016). Specifically, the following pairs of closely apposed residues can be targeted: Q168-D400, D179-M399, D180-H398, D180-M399. We therefore hypothesized that the following two manipulations may reinforce NTR169Q tetramerization (Figure 2B): 1. Substitution of Q168 for arginine, a basic amino acid with a long side chain, which may increase the electrostatic interaction with the negatively-charged side chain of D400, 2. Substitution of M399 for arginine, which may increase the electrostatic interaction with both acidic residues D179 and D180.

Initially, we tested whether Q168R and M399R affect RyR2 NTD tetramerization. As shown in Figure 2C, NTQ168R and NTM399R tetramer formation (102% and 82% of WT at 60 min, respectively) was similar to NTWT. We next generated RyR2 NT constructs carrying the CPVT R169Q mutation together with the Q168R or M399R substitution. NTR169Q+Q168R and NTR169Q+M399R displayed higher tetramer formation (77% and 84% of WT at 60 min, respectively) compared to NTR169Q (51% of WT at 60 min). Although NTR169Q+Q168R and NTR169Q+M399R tetramer formation did not reach statistical significance relative to NTR169Q, it was also not significantly different to NTWT (Table 2). These results indicate that the engineered Q168R and M399R substitutions partially restore NTD tetramerization to RyR2-R169Q.

Numerous RyR1 and RyR2 mutations associated with MH and CPVT, respectively, have been functionally characterized with the vast majority resulting in gain-of-function channels (Hernandez-Ochoa et al., 2016; Fowler and Zissimopoulos, 2022). However, how pathogenic RyR mutations function at the molecular or structural level, i.e., what is the defective RyR regulatory mechanism(s), is poorly understood. Here, we demonstrate that perturbed NTD tetramerization is a common molecular mechanism operating in RyR1 and RyR2 genetic disease.

RyR1 R163C is one of the most studied MH mutations in heterologous (HEK293) and homologous expression systems (dyspedic myotubes) as well as in heterozygous knockin mice. Results obtained from single channel recordings, [3H]ryanodine binding and Ca2+ imaging indicate enhanced basal activity, increased sensitivity to Ca2+ activation, increased sensitivity to pharmacological activators, and elevated resting cytosolic Ca2+ concentration (Tong et al., 1997; Avila and Dirksen, 2001; Yang et al., 2003; Yang et al., 2006; Feng et al., 2011; Chen et al., 2018; Iyer et al., 2020). Here, we used chemical cross-linking to demonstrate that R163C impairs RyR1 NTD tetramerization (Figure 1). Our biochemical findings are in agreement with the 3D structure of RyR1-R163C, which was recently solved at near-atomic resolution under the same closed-state conditions as with RyR1-WT (Iyer et al., 2020). R163C was found to cause a shift and rotation in the NTD that resulted in increased NTD-NTD inter-subunit distance. This stabilized the NTD interaction with the core solenoid, which in turn altered the high-affinity Ca2+-binding site. Thus, RyR1-R163C is inherently hyperactive and leaky primarily due to defective N-terminal inter-subunit interactions.

RyR2 R169Q is a gain-of-function CPVT mutation as indicated by higher propensity for spontaneous Ca2+ oscillations in HEK293 cells and increased Ca2+-dependent [3H]ryanodine binding (Nozaki et al., 2020). Our chemical cross-linking analysis demonstrates that R169Q impairs RyR2 NTD tetramerization (Figure 2; Table 2), similar to our previous observation with the R176Q mutation (Seidel et al., 2021). The mutations studied here do not involve the loss or introduction of lysine residues and therefore there is no change in the number or location of amino acids amenable to glutaraldehyde reaction, however, we cannot rule out the possibility that these mutations indirectly alter the ability of glutaraldehyde to cross-link lysine residues in adjacent RyR NT monomers by affecting the local conformation. We should also note that we studied pathogenic mutations in a homozygous scenario, whereas MH and CPVT1 are autosomal dominant diseases. Our results are consistent with previous molecular dynamics simulations indicating that R169Q, as well as A165D and R176Q, increase the NTD-NTD inter-subunit distance (Xiong et al., 2018). Hence, the present study adds to the mounting evidence from biochemical, structural, and molecular dynamics analyses that RyR1 and RyR2 pathogenic mutations located within the β8-β9 loop disrupt NTD tetramerization (Table 1) (Iyer et al., 2020; Seidel et al., 2021; Xiong et al., 2018).

The RyR N-terminus has previously been implicated in neuromuscular and cardiac disease because of disrupted interaction with the central domain (Ikemoto and Yamamoto, 2002), also known as “helical domain-1” (Peng et al., 2016; Yan et al., 2015) and “bridging solenoid (BSol)” (des Georges et al., 2016). However, RyR1-R163C and RyR2-R169Q are unlikely to affect this structure-function parameter because the NTD interface with the BSol (RyR1 residues 2146–2712, RyR2 residues 2111–2679) involves residues other than those of the β8-β9 loop (des Georges et al., 2016; Peng et al., 2016; Yan et al., 2015). Indeed, no differences in the NTD-BSol interface were reported in the RyR1-R163C structure compared to WT (Iyer et al., 2020). On the other hand, altered NTD-BSol interface was recently reported for RyR1-R615C, which induced a distinct pathological conformation in RyR1 to facilitate channel opening (Woll et al., 2021). Thus, N-terminal mutations may affect different RyR inter-domain associations, but all the available evidence suggests that mutations within the β8-β9 loop (e.g., RyR1-R163C, RyR2-R169Q) alter N-terminal inter-subunit interactions.

Importantly, diminished NTD tetramerization due to the CPVT R169Q mutation can be reinforced by introducing positively-charged amino acids at the NTD-NTD interface (Figure 2). R169Q likely results in diminished NTD tetramerization because of the loss of a salt bridge with D400 on the neighboring subunit (Peng et al., 2016; Xiong et al., 2018). On the other hand, our introduced structural mutations Q168R and M399R may create new salt bridges with D400 and D179/D180, respectively, which appear to compensate for the loss of R169-D400 electrostatic interaction. These observations add further weight to the role of the β8-β9 and β23-β24 loops in mediating efficient N-terminal inter-subunit interactions. Notably, they act as proof of concept for stabilizing N-terminal inter-subunit interactions in RyR2 disease. While such genetic manipulation is an unlikely therapeutic tool, the development of small chemical compounds that target the RyR2 NTD-NTD interface holds great promise as potential therapy in CPVT.

The raw data supporting the conclusion of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

SZ conceived the study designed the experiments and wrote the paper; YZ, CRdM, and AB performed and analyzed the experimental data; FAL contributed reagents and materials; SZ and FAL edited the manuscript.

This work was supported by a British Heart Foundation Fellowship (FS/15/30/31494) and project grant to SZ (PG/21/10657).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Avila G., Dirksen G. (2001). Functional effects of central core disease mutations in the cytoplasmic region of the skeletal muscle ryanodine receptor. J. Gen. Physiol. 118, 277–290. doi:10.1085/jgp.118.3.277

Chen W., Koop A., Liu Y., Guo W., Wei J., Wang R., et al. (2018). Reduced threshold for store overload-induced Ca(2+) release is a common defect of RyR1 mutations associated with malignant hyperthermia and central core disease. Biochem. J. 474, 2749–2761. doi:10.1042/BCJ20170282

des Georges A., Clarke O. B., Zalk R., Yuan Q., Condon K. J., Grassucci R. A., et al. (2016). Structural basis for gating and activation of RyR1. Cell 167, 145–157. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2016.08.075

Feng W., Barrientos G. C., Cherednichenko G., Yang T., Padilla I. T., Truong K., et al. (2011). Functional and biochemical properties of ryanodine receptor type 1 channels from heterozygous R163C malignant hyperthermia-susceptible mice. Mol. Pharmacol. 79, 420–431. doi:10.1124/mol.110.067959

Fowler E. D., Zissimopoulos S. (2022). Molecular, subcellular, and arrhythmogenic mechanisms in genetic RyR2 disease. Biomolecules 12, 1030. doi:10.3390/biom12081030

Hernandez-Ochoa E. O., Pratt S. J. P., Lovering R. M., Schneider M. F. (2016). Critical role of intracellular RyR1 calcium release channels in skeletal muscle function and disease. Front. Physiol. 6, 420. doi:10.3389/fphys.2015.00420

Hernandez-Ochoa E. O., Schneider M. F. (2018). Voltage sensing mechanism in skeletal muscle excitation-contraction coupling: Coming of age or midlife crisis? Skelet. Muscle 8, 22. doi:10.1186/s13395-018-0167-9

Ikemoto N., Yamamoto T. (2002). Regulation of calcium release by interdomain interaction within ryanodine receptors. Front. Biosci. 7, d671–d683. doi:10.2741/A803

Iyer K. A., Hu Y., Nayak A. R., Kurebayashi N., Murayama T., Samso M. (2020). Structural mechanism of two gain-of-function cardiac and skeletal RyR mutations at an equivalent site by cryo-EM. Sci. Adv. 6, eabb2964. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abb2964

Nozaki Y., Kato Y., Uike K., Yamamura K., Kikuchi M., Yasuda M., et al. (2020). Co-phenotype of left ventricular non-compaction cardiomyopathy and atypical catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia in association with R169Q, a ryanodine receptor type 2 missense mutation. Circ. J. 84, 226–234. doi:10.1253/circj.CJ-19-0720

Peng W., Shen H., Wu J., Guo W., Pan X., Wang R., et al. (2016). Structural basis for the gating mechanism of the type 2 ryanodine receptor RyR2. Science 354, aah5324. doi:10.1126/science.aah5324

Rios E. (2018). Calcium-induced release of calcium in muscle: 50 years of work and the emerging consensus. J. Gen. Physiol. 150, 521–537. doi:10.1085/jgp.201711959

Seidel M., Thomas N. L., Williams A. J., Lai F. A., Zissimopoulos S. (2015). Dantrolene rescues aberrant N-terminus inter-subunit interactions in mutant pro-arrhythmic cardiac ryanodine receptors. Cardiovasc. Res. 105, 118–128. doi:10.1093/cvr/cvu240

Seidel M., de Meritens C. R., Johnson L., Parthimos D., Bannister M., Thomas N. L., et al. (2021). Identification of an amino-terminus determinant critical for ryanodine receptor/Ca2+ release channel function. Cardiovasc. Res. 117, 780–791. doi:10.1093/cvr/cvaa043

Tong J., Oyamada H., Demaurex N., Grinstein S., McCarthy T. V., MacLennan D. H. (1997). Caffeine and halothane sensitivity of intracellular Ca2+ release is altered by 15 calcium release channel (ryanodine receptor) mutations associated with malignant hyperthermia and/or central core disease. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 26332–26339. doi:10.1074/jbc.272.42.26332

Tung C. C., Lobo P. A., Kimlicka L., Van Petegem F. (2010). The amino-terminal disease hotspot of ryanodine receptors forms a cytoplasmic vestibule. Nature 468, 585–588. doi:10.1038/nature09471

Woll K. A., Haji-Ghassemi O., Van Petegem F. (2021). Pathological conformations of disease mutant Ryanodine Receptors revealed by cryo-EM. Nat. Commun. 12, 807. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-21141-3

Xiong J., Liu X., Gong Y., Zhang P., Qiang S., Zhao Q., et al. (2018). Pathogenic mechanism of a catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia causing-mutation in cardiac calcium release channel RyR2. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 117, 26–35. doi:10.1016/j.yjmcc.2018.02.014

Yan Z., Bai X. C., Yan C., Wu J., Li Z., Xie T., et al. (2015). Structure of the rabbit ryanodine receptor RyR1 at near-atomic resolution. Nature 517, 50–55. doi:10.1038/nature14063

Yang T., Ta T. A., Pessah I. N., Allen P. D. (2003). Functional defects in six ryanodine receptor isoform-1 (RyR1) mutations associated with malignant hyperthermia and their impact on skeletal excitation-contraction coupling. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 25722–25730. doi:10.1074/jbc.M302165200

Yang T., Riehl J., Esteve E., Matthaei K. I., Goth S., Allen P. D., et al. (2006). Pharmacologic and functional characterization of malignant hyperthermia in the R163C RyR1 knock-in mouse. Anesthesiology 105, 1164–1175. doi:10.1097/00000542-200612000-00016

Zheng W., Liu Z. (2017). Investigating the inter-subunit/subdomain interactions and motions relevant to disease mutations in the N-terminal domain of ryanodine receptors by molecular dynamics simulation. Proteins 85, 1633–1644. doi:10.1002/prot.25318

Zissimopoulos S., Lai F. (2007). “Ryanodine receptor structure, function and pathophysiology,” in Calcium: A matter of life or death (Elsevier), 287–342.

Zissimopoulos S., Viero C., Seidel M., Cumbes B., White J., Cheung I., et al. (2013). N-terminus oligomerization regulates the function of cardiac ryanodine receptors. J. Cell Sci. 126, 5042–5051. doi:10.1242/jcs.133538

Keywords: amino-terminus, catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia, malignant hyperthermia, inter-subunit interaction, tetramerization, ryanodine receptor (RyR)

Citation: Zhang Y, Rabesahala de Meritens C, Beckmann A, Lai FA and Zissimopoulos S (2022) Defective ryanodine receptor N-terminus inter-subunit interaction is a common mechanism in neuromuscular and cardiac disorders. Front. Physiol. 13:1032132. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2022.1032132

Received: 30 August 2022; Accepted: 28 September 2022;

Published: 12 October 2022.

Edited by:

Nordine Helassa, University of Liverpool, United KingdomReviewed by:

Angela Fay Dulhunty, Australian National University, AustraliaCopyright © 2022 Zhang, Rabesahala de Meritens, Beckmann, Lai and Zissimopoulos. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Spyros Zissimopoulos, c3B5cm9zLnppc3NpbW9wb3Vsb3NAc3dhbnNlYS5hYy51aw==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.