- 1Department of Geosciences, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ, United States

- 2Department of Marine and Coastal Science, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ, United States

- 3Department of Biological and Environmental Sciences, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden

- 4Department of Molecular Biology, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ, United States

- 5Department of Human and Evolutionary Biology, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, United States

- 6Department of Physiology and Neuroscience, University of Southern California Keck School of Medicine, Los Angeles, CA, United States

As the most abundant cation in archaeal, bacterial, and eukaryotic cells, potassium (K+) is an essential element for life. While much is known about the machinery of transcellular and paracellular K transport–channels, pumps, co-transporters, and tight-junction proteins—many quantitative aspects of K homeostasis in biological systems remain poorly constrained. Here we present measurements of the stable isotope ratios of potassium (41K/39K) in three biological systems (algae, fish, and mammals). When considered in the context of our current understanding of plausible mechanisms of K isotope fractionation and K+ transport in these biological systems, our results provide evidence that the fractionation of K isotopes depends on transport pathway and transmembrane transport machinery. Specifically, we find that passive transport of K+ down its electrochemical potential through channels and pores in tight-junctions at favors 39K, a result which we attribute to a kinetic isotope effect associated with dehydration and/or size selectivity at the channel/pore entrance. In contrast, we find that transport of K+ against its electrochemical gradient via pumps and co-transporters is associated with less/no isotopic fractionation, a result that we attribute to small equilibrium isotope effects that are expressed in pumps/co-transporters due to their slower turnover rate and the relatively long residence time of K+ in the ion pocket. These results indicate that stable K isotopes may be able to provide quantitative constraints on transporter-specific K+ fluxes (e.g., the fraction of K efflux from a tissue by channels vs. co-transporters) and how these fluxes change in different physiological states. In addition, precise determination of K isotope effects associated with K+ transport via channels, pumps, and co-transporters may provide unique constraints on the mechanisms of K transport that could be tested with steered molecular dynamic simulations.

1 Introduction

Archaeal, bacterial, and eukaryotic cells all concentrate potassium (K+). In fact, the ubiquity of elevated intracellular K+ has been hypothesized to provide insight into the environments (high K/Na ratios) where the first cells emerged (Mulkidjanian et al., 2012). In bacteria, intracellular K+ is at >100 mM by the active pumping of K+ from extracellular fluid (ECF) into the intracellular fluid (ICF) by transporters that use ATP or the proton motive force (Stautz et al., 2021). In eukaryotic cells, intracellular K+ is maintained at similarly elevated levels by the active pumping of K+ by plasma membrane Na,K-ATPase, an energetically intensive process which can account for ∼20% of basal metabolism in mammals (Rolfe and Brown, 1997). In all cells, the active transport of K+ into the cell establishes a steep transmembrane gradient that is a key determinant of membrane potential and a source of energy to drive action potentials, control muscle contractility, maintain cell turgor, contribute to pH homeostasis, and power ion transporters (Youn and McDonough, 2009; Stautz et al., 2021).

The regulation of K+ at both the cellular and organismal level, K+ homeostasis, is ultimately accomplished at the molecular level by transcellular and paracellular transporters (including ion pumps, channels, co-transporters) that move K+ across membranes and between cells (Agarwal et al., 1994; Gierth and Mäser, 2007; Youn and McDonough, 2009; Furukawa et al., 2012). Although life has evolved a diversity of molecular machines capable of K+ transport across cell membranes, certain aspects of cellular K+ transport are conserved across the major domains. For example, all known K+ channels are members of a single protein family whose amino acid sequence contains a highly conserved segment [the K+ channel signature sequence (MacKinnon, 2003)]. The shared molecular machinery of K+ transport in biological systems reflects the fundamental role of the electrochemical potential generated by biologically maintained gradients of K+ across cell membranes. K+ pumps establish and maintain concentration gradients across cell membranes by moving K+ (from ECF-ICF) and Na or H (from ICF to ECF) “uphill” against their electrochemical potentials coupled to and driven by the hydrolysis of ATP. K+ co-transporters couple uphill K+ transport to “downhill” transport of another ion (e.g., Na+ or Cl−). Finally, K+ channels and the pores in tight-junction proteins provide an energetically favorable pathway for rapid, yet highly selective, transport of K+ down its electrochemical potential.

While the identity and structure of the molecular machines that maintain K+ homeostasis in biological systems are well-known, many quantitative aspects of K+ homeostasis and the specific molecular mechanisms of K+ transport by pumps, channels, co-transporters, and through tight-junction proteins are unconstrained or debated. For example, structural, functional and computational studies of K+ channels produce conflicting results as to whether the molecular mechanism of K+ permeation is water mediated or occurs by direct knock-on of cations (Mironenko et al., 2021). In addition, while studies of gene expression in cells and tissues can be used to identify which K transporters are active, quantitative constraints on the fluxes of K+ through the different types of transporters in vivo are non-existent.

In natural systems potassium is made up of two stable (potassium-39 and potassium-41) and one radioactive (potassium-40) isotope. The two stable isotopes of K, 39K and 41K, constitute 93.258% and 6.730% of the total, respectively, resulting in a ratio of 41K/39K in nature of ∼0.07217. Recent advances in inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) now permit the precise quantification of deviations from the terrestrial ratio resulting from the biogeochemical cycling of potassium in nature with a precision of 1 part in 10,000 (Wang and Jacobsen, 2016; Morgan et al., 2018). Here we apply this analytical tool to study K+ homeostasis in three biological systems–aquatic green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (C. reinhardtii), a suite of marine fish that include species that can tolerate a wide range in salinities (euryhaline) as well as those that have a restricted salinity range (stenohaline), and the terrestrial mammal Rattus norvegicus (R. norvegicus). The results in each system are interpreted as reflecting K+ homeostasis under normal (optimal) growth conditions.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 C. reinhardtii cultures

The CMJ030 wild type strain was obtained from the Chlamydomonas culture collection www.chlamycollection.org). Tris Phosphate (TP) medium was prepared according to: Gorman, D.S, and R.P. Levine (1965) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. United States 54, 1665–1669. The culture at an initial density of 0.5 × 105 cells mL−1 was grown in TP under continuous illumination (100 μmol photons m−2 s−1) and shaking for 4 days. Samples (in triplicate) containing 2 × 107 cells (∼800 mg) were harvested and washed twice in 5 mM HEPES and 2 mM EDTA before collection and air-drying of the cell pellet. Pelletized cells (∼30 mg) were digested in screw-capped teflon vials on a hot plate at elevated temperatures (∼75°C) using a 5:2 mixture of HNO3 (68–70 vol.%) and H2O2 (30 vol.%).

2.2 Euryhaline and stenohaline marine teleosts

Samples of teleost muscle tissue were sourced from fish markets (Nassau Seafood and Trader Joe’s in Princeton, NJ and the Fulton Fish Market in Brooklyn, NY) and research cruises (NOAA NEFSC Bottom Trawl Survey, Fall 2015 and Spring 2015). All teleosts were caught in seawater which has a uniform δ41K value of +0.12‰ relative to SRM3141a (Ramos et al., 2020). Samples of white dorsal muscle (100–3000 mg) were digested on a hot plate at elevated temperatures (∼75°C) or in a high-pressure microwave system (MARS 6) using HNO3 (68–70 vol.%) H2O2 (30 vol.%) in a ratio of 5:2. Major/minor element analyses for digested samples were carried out at Princeton University using a quadrupole inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific iCap Q). Concentrations and elemental ratios were determined using externally calibrated standards and average uncertainties (element/element) are ∼10%.

2.3 R. norvegicus experiments

All rat experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of the University of Southern California. Two series were conducted. Series #1: Male Wistar rats (n = 3, 250–275 g body weight, Envigo, Indianapolis, IN) were housed in a climate controlled (22–24°C) environment with a 12 h: 12 h light/dark cycle, and fed casein based normal K+ diet TD.08267 (Envigo, Indianapolis, IN) and water ad libitum for 11 days. At day 8, rats were placed overnight into metabolic cages (Techniplast, Buguggiate, Italy) with food and water ad libitum for 16-h collection of urine and feces. On termination day (1:30–3:30p.m.), rats were anesthetized with an intramuscular (IM) injection of ketamine (80 mg/kg, Phoenix Pharmaceuticals, St. Joseph, MO) and xylazine (8 mg/kg, Lloyd Laboratories, Shenandoah, IA) in a 1:1 ratio. Through a midline incision, the liver, kidneys, heart, fat pads, and stomach (flushed of contents) were removed; blood was collected via cardiac puncture, spun down to separate plasma from RBCs. Then gastrocnemius, soleus, TA, and EDL skeletal muscles were dissected. All tissues were washed in ice-cold TBS to remove excess blood, weighed and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen. Series #2: Male Sprague Dawley rats (n = 4, 250–300 g, Envigo, Indianapolis, IN) were housed in a climate controlled (22–24°C) environment with a 12 h: 12 h light/dark cycle and fed grain-based vivarium chow (LabDiet 5001, labdiet.com). CSF extraction procedures are as reported previously (Noble et al., 2018). In brief, Rats were deeply anesthetized using a cocktail of ketamine 90 mg/kg, xylazine, 2.8 mg/kg, and acepromazine 0.72 mg/kg by intramuscular injection. A needle was lowered to below the caudal end of the occipital skull and the syringe plunger pulled back slowly, allowing the clear CSF to flow into the syringe. After extracting ∼100–200 µL of CSF, the needle was raised quickly (to prevent suction of blood while coming out of the cisterna magna) and the CSF dispensed into a microfuge tube and immediately frozen in dry ice and then stored at -80°C until time of analysis. Following CSF extraction and decapitation, whole brains with 10–15 mm spinal cord extension were rapidly removed and immediately flash frozen and stored in -80°C until dissection into spinal cord, cerebrum, and cerebellum for subsequent digestion and K isotopic analysis.

2.4 Ion chromatography and isotope ratio mass-spectrometry

K was purified for isotopic analyses using an automated high-pressure ion chromatography (IC) system. The IC methods utilized here followed those previously described in (Morgan et al., 2018; Ramos et al., 2018). Briefly, chemical separation of cations for high-precision isotopic analyses by MC-ICP-MS was performed using an automated Dionex ICS-5000 + ion chromatography (IC) system at Princeton University. Digested samples were dried down then diluted in 0.2% HNO3 acid to ∼10–20 ppm K and loaded onto a Dionex CS-16 cation exchange column at a rate of 1 ml/min with methanesulfonic acid (MSA) as eluent. Minimum sample sizes needed for both column chemistry and mass spectrometry were <5 µg of K and samples were run along with external standards in order to monitor the efficacy of column chemistry. External standards included a high-purity K solutions (SRM3141a), and the NIST K-feldspar standard SRM 70 b. Purified K solutions were allowed to dry overnight in PFA Teflon vials, redissolved in 200 µL of 16 N (70% v/v) trace-metal grade HNO3 in order to eliminate any organics, then dried again prior to isotopic analysis. Purified K separates were diluted to ∼1 ppm K in 2% trace-metal grade HNO3 prior to isotopic analysis on a Thermo Scientific Neptune Plus multi-collector inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometer (MC-ICP-MS) at Princeton University. Measurement of K isotopic ratios by MC-ICP-MS is hindered by the large isobaric interferences on masses 39 and 41, due to ionization of the carrier gas (argon) and formation of argon hydrides (38ArH+ and 40ArH+, respectively). Here, we use cold plasma (∼600 W) settings, an Elemental Scientific Instruments (ESI) Apex Omega desolvating nebulizer, and high mass-resolution mode (M/ΔM ca. 10,000) to measure 41K/39K ratios on small (2–3 milli-amu) but flat peak shoulders. The instrument is tuned to optimize stability and sensitivity, with ∼1 ppm K yielding voltages between 5 and 6 V on mass 39. Caution was taken to assure that samples matched standard concentrations (∼1 ppm K) to within 5%, artifacts due to imbalances during analysis were corrected using high-purity K standards run at different ion intensities in the same analytical session, and the same batch of 2% HNO3 was used to dilute both samples and standards in a single run. Instrumental mass-drift was corrected by applying the standard-sample-standard bracketing technique with high-purity KNO3 as the bracketing standard solution. The accuracy of our chromatographic methods was verified by purifying and analyzing external standards (SRM3141a and SRM70 b) alongside unknown samples. Purified aliquots of K were analyzed in 2% HNO3 for their isotopic compositions on a Thermo Scientific Neptune Plus multi-collector inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometer (MC-ICP-MS) at Princeton University, using previously published methods (Morgan et al., 2018; Ramos et al., 2020). The data are presented using standard delta notation in parts per thousand (‰).

where

3 Results

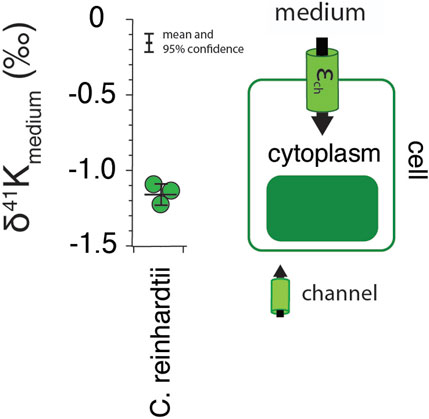

Results for the freshwater algae C. reinhardtii are shown in Figure 1. Measured δ41K values of the whole cells are 1.2 ± 0.07‰ lower than the δ41K value of the growth medium (0‰ by definition) (95% confidence; p = 4.5 × 10−5).

FIGURE 1. The difference in δ41K values between external and intracellular K+ in growth experiments of C. reinhardtii and a diagram of K+ transport in singlecelled algae grown under optimal conditions (See Methods) including major fluxes (Fin), transport machinery, and K isotope effects (εin). p = 4.5 × 10−5 by one-way ANOVA in Matlab.

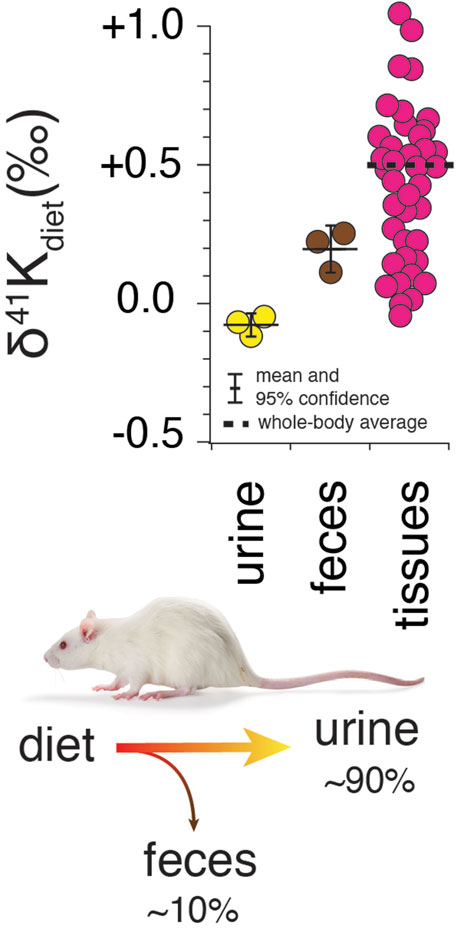

Results for R. norvegicus are shown in Figures 2–4. Figure 2 shows the measured δ41K values of both urine and feces, normalized to the δ41K value of the rat diet (δ41Kdiet). A positive δ41Kdiet value in feces (+0.19 ± 0.09‰, 95% confidence; p = 0.037; Figure 2) and slightly negative δ41Kdiet value in urine (-0.09 ± 0.10‰, 95% confidence; p = 0.1895) are consistent with preferential net uptake of 39K relative to 41K across the gut epithelium.

FIGURE 2. Whole-body K isotope mass balance in R. norvegicus on a controlled diet. Measured δ41K values of urine (p = 0.19) and feces (p = 0.037) relative to diet indicate a preferential uptake of 39K in the gut. The total range in δ41Kdiet values in the tissues of R. norvegicus is ∼1‰ with an estimated whole-body average δ41Kdiet value of approx. +0.5‰, consistent with preferential loss of 39K in urine.

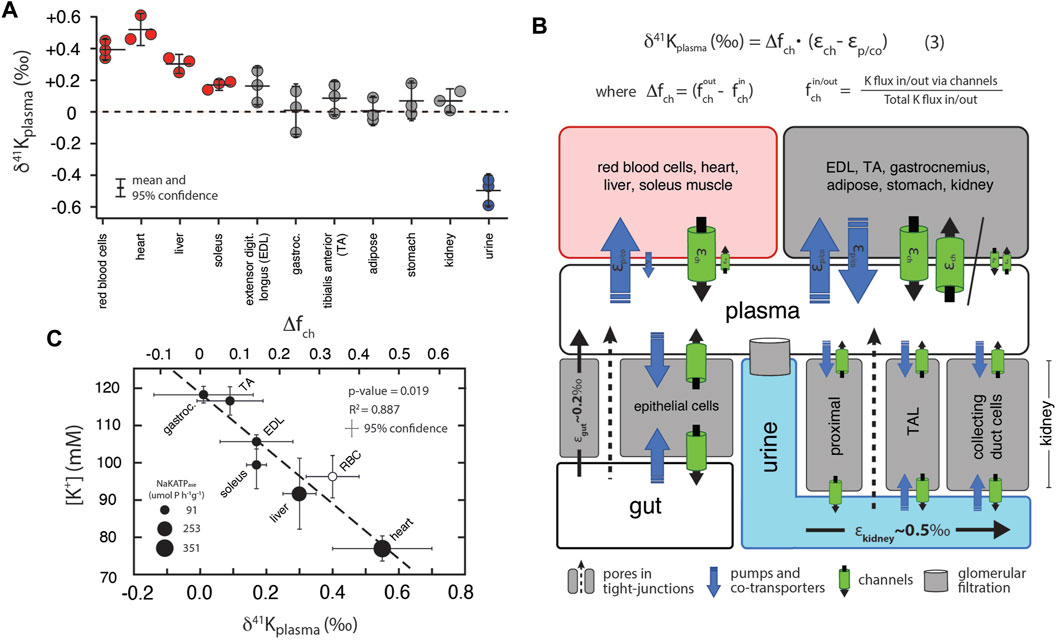

Figure 3A shows measurements of K isotopes of various tissues in R. norvegicus (except brain tissues) normalized to the δ41K value of the blood plasma (δ41Kplasma), as this represents the extracellular K concentration bathing the tissues. The overall range in δ41Kplasma values between different tissues and fluids is ∼1‰; δ41K values of the following tissues are elevated in 41K relative to blood plasma (positive δ41Kplasma values): red blood cells (+0.40 ± 0.08‰, p = 0.005), heart (+0.55 ± 0.15‰, p = 0.0047), liver (+0.30 ± 0.05‰, p = 0.01), and soleus muscle (+0.17 ± 0.03‰, p = 0.05). In another category are tissues with δ41Kplasma values that are statistically indistinguishable from zero: kidneys (+0.07 ± 0.07‰, p = 0.31), adipose tissue (+0.01 ± 0.08‰, p = 0.92), extensor digitorum longus (EDL, +0.17 ± 0.11‰, p = 0.099) gastrocnemius (+0.01 ± 0.15‰, p = 0.92), and tibialis anterior (TA, +0.09 ± 0.1‰, p = 0.30). Finally, urine is characterized by a δ41Kplasma value that is negative (-0.50 ± 0.10‰, p = 0.0019) indicating preferential enrichment of 39K relative to blood plasma. Figure 3B is a diagram of K isotope mass balance between internal tissues in R. norvegicus and Figure 3C shows the correlation between measured δ41Kplasma values, the concentration of K+ (in mM) in the tissue, and the activity of NaKATPase (Gick et al., 1993).

FIGURE 3. (A) K isotopic composition of tissues/fluids R. norvegicus (casein diet) normalized to plasma (δ41Kplasma = 0‰). δ41Kplasma values that are positive indicate that net K+ transport out of the tissue/cell/fluid is enriched in 39K relative to K+ transport into the tissue/cell/fluid. δ41Kplasma values that are indistinguishable from 0 indicate that the K isotope fractionation associated with K+ transport into and out of the cell/tissue/fluid are either 0 or equal in magnitude (and thus cancel). δ41Kplasma values that are negative indicate that net K+ transport into the cell/tissue/fluid is enriched in 39K relative to K+ transport out of the cell/tissue/fluid. (B) A diagram of K isotope mass balance including transport by (1) K-channels, (2) K-pumps/co-transporters, (3) through pores in tight-junctions, and (4) glomerular filtration. Eq. 3 solves for the δ41K value of a tissue/cell relative to blood plasma assuming steady-state K isotope mass balance with bi-directional K+ transport by both channels and pumps/co-transporters. Variables include fout/in ch , the fraction of total K+ transport into/out of the tissue/cell that occurs through K+ channels, Δfch , the difference in the fraction of K transport via channels (fout ch -fin ch), εch , K isotope fractionation associated with K channels, and εp/co K isotope fractionation associated with pumps/co-transporters. K isotope fractionation associated with K+ uptake in the gut (εgut) and K+ loss in urine (εkidney) reflect the flux-weighted average of both paracellular and transcelluar K+ transport. For example, K isotope fractionation in the kidney will be associated with both re-absorption and secretion of K+ in the proximal tubule, the thick ascending limb (TAL), and cells in the collecting ducts of the kidney. (C) Correlation between intercellular [K+] and δ41Kplasma values for a subset of tissues from R. norvegicus. Also shown are the measured activities of NaKATPase (µmol P h−1 g−1 from Gick et al., (1993) and values of Δfch from Eq. 3.

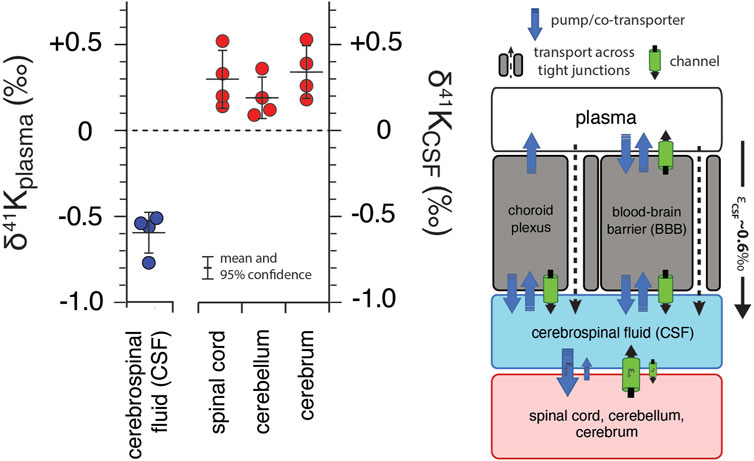

Figure 4 shows of K isotopes of brain tissues, normalized to CSF (δ41KCSF) and CSF normalized to blood plasma. Brain tissues are elevated in 41K relative to CSF (positive δ41KCSF values): cerebrum (+0.34 ± 0.15‰, p = 0.012), spinal cord (+0.30 ± 0.17‰, p = 0.026), and cerebellum (+0.21 ± 0.11‰, p = 0.037). In contrast, CSF (-0.59 ± 0.12‰, p = 6.2 × 10−5) is characterized by a negative δ41Kplasma value.

FIGURE 4. K isotopic composition of cerebrospinal fluid from R. norvegicus raised on a controlled diet (vivarium chow) normalized to blood plasma (δ41Kplasma = 0‰) and brain tissues normalized to cerebrospinal fluid (δ41KCSF = 0‰) together with a diagram of K homeostasis across the choroid plexus and blood brain barrier (BBB) from Hladky and Barrand (2016) including transport by (1) K-channels, (2) K-pumps/co-transporters, and (3) transcellularly through pores in tight-junctions. δ41KCSF values that are positive indicate that net K transport out of brain tissues (spinal cord, cerebellum, and cerebrum) and into CSF is enriched in 39K relative to K transport from CSF into these tissues. The negative δ41Kplasma values for CSF indicate that net K transport into CSF from blood plasma is enriched in 39K relative to K transport from CSF to blood plasma and reflects the flux weighted average of the transporters that dominate K+ exchange across both the choroid plexus and BBB.

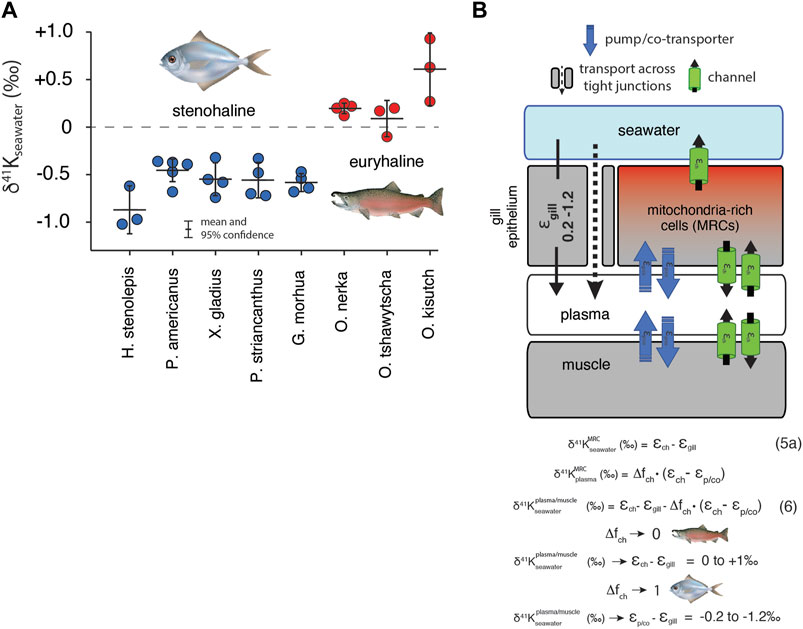

Results for white muscle tissue from a suite of stenohaline and euryhaline marine fish, reported relative to the 41K/39K of seawater (δ41Kseawater = 0‰) are shown in Figure 5A. The total range in muscle δ41K values is ∼2‰ (+1‰ to -1‰). Stenohaline species including Gadus morhua (Atlantic Cod), Peprilus striacanthus (Butterfish), Xiphias gladius (Swordfish), Pseudopleuronectes americanus (Winter Flounder), and Hippoglossus stenolepis (Pacific Halibut) are characterized by δ41Kseawater values that are uniformly negative whereas the euryhaline species Oncorhynchus kisutch (Coho Salmon), Oncorhynchus tshawytscha (King Salmon), and Oncorhynchus nerka (Sockeye Salmon) are characterized by δ41Kseawater values that are close to zero or positive. When species are grouped by salinity tolerance, average measured δ41Kseawater values of the two groups are -0.58 ± 0.09‰, and 0.29 ± 0.18‰ for stenohaline and euryhaline species, respectively (95% confidence; p = 1.4 × 10−10). Figure 5B shows a diagram of external and internal K isotope mass balance in marine fish.

FIGURE 5. (A) The difference in δ41K values between seawater and dorsal white muscle of various stenohaline and euryhaline marine fish. Muscle [K+] and δ41Kseawater values are listed in Supplementary Table S1. p = 1.4 × 10−10 for the difference in δ41Kseawater value between stenohaline and euryhaline teleosts. (B) A model of K isotope mass balance in a marine fish. K+ is supplied across the gill epithelium via transport through pores in tight-junction proteins and lost from mitochondria-rich cells (MRCs) through channels Eq. 5. K+ cycling within MRCs is modeled using Eq. 3. Combining Eq. 3 and Eq. 5a yields Eq. 6, the δ41K value of plasma/muscle relative to seawater as a funciton of εch, εgill, Δfch of MRC’s and εp/co. As Δfch → 0, δ41K of fish muscle → εch - εgill (≥ 0‰, euryhaline), whereas as Δfch→ 0, δ41K of fish muscle → εp/co-εgill (<0‰, stenohaline). fish illustrations from Lori Moore.

4 Discussion

The shared machinery of K+ transport across the domains of life suggests that the variability in K isotopes observed in biological systems can be reduced to a consideration of 1) how different classes of K+ transporters—tight junctions, channels, pumps, and co-transporters - discriminate between 39K and 41K and 2) how these transporters are assembled into a homeostatic system. The extent to which K+ transporters fractionate K isotopes will, in turn, depend on the mechanics and selectivity of the transporter and whether the binding of dissolved K+ to transporter is the rate-limiting step. In particular, K+ channels and pores in tight-junction proteins are both associated with selective and rapid (near the limit of diffusion) transport of K+ where the rate-limiting step is the binding of dissolved K+ to the transporter/selectivity filter. These conditions favor kinetic isotope effects which may arise from either partial or full desolvation of K+ as it binds to the selectivity filter (Berneche and Roux, 2003; Yu et al., 2010; Hofmann et al., 2012; Kopec et al., 2018), differences in ionic radius of 39K and 41K [size selectivity (Christensen et al., 2018)], or some combination of the two. Critically, the magnitude of the kinetic isotope effects associated with both desolvation and/or size selectivity appear to be large, with estimates from laboratory experiments and molecular dynamic simulations ranging from ∼1 to 2.7‰ (Hofmann et al., 2012).

In contrast to channels and pores in tight-junction proteins, transport of K+ by pumps and co-transporters is relatively slow [per unit transporter, (Roux, 2017)], requires the simultaneous binding of multiple ions (e.g., 2 K+ ions in the case of Na,K-ATPase), and is associated with mechanisms of self-correction that prevent the pump cycle from proceeding if incorrect ions bind to the ion pocket (Rui et al., 2016). As a result, although the binding of K+ to the active site of a pump or cotransporter may also involve desolvation, it is not the rate-limiting step in K+ transport. In this case, the isotopic composition of K+ that is transported by pumps and co-transporters may reflect isotopic equilibration between K+in the ion pocket and the fluid due to the longer residence time of K+ in the ion pocket prior to occlusion. As equilibrium K isotope effects tend to be small (Li et al., 2017; Ramos et al., 2018; Zeng et al., 2019), we hypothesize that K+ transport by pumps and co-transporters will be associated with less isotopic fractionation.

In the following sections we show how our results for the three studied biological systems (algae, fish, mammals) can be interpreted within a single framework where K+ transport by channels and pores in tight-junction proteins is associated with large (kinetic) K isotope effects whereas K+ transport by pumps and/or co-transporters is associated with smaller (equilibrium) K isotope effects. In simple biological systems (e.g., single celled alga) linking K isotope fractionation to the machinery of K+ transport is relatively straightforward due to the small number of pathways involved and the unidirectional nature of K+ transport. In more complex biological systems (e.g., higher plants, fish, and mammals) discerning transporter-specific fractionation of K isotopes is more difficult for at least two reasons. First, our understanding of K homeostasis at both the tissue and organism level is incomplete. Second, our measured K isotopic differences (e.g., between plasma/CSF/seawater and tissue) only provide information on net K isotope fractionation associated with bi-directional K+ transport at steady-state. In spite of these limitations, our results support a framework for K isotope fractionation in biological systems that can provide new quantitative insights into the mechanisms of K+ transport and the dynamics of K homeostasis.

4.1 Algae

As an essential macronutrient in all plants and the most abundant cation in the cytoplasm, K+ contributes to electrical neutralization of anionic groups, membrane potential and osmoregulation, photosynthesis, and the movements of stomata (Gierth and Mäser, 2007; Marchand et al., 2020). It is well-established that K+ channels play prominent roles in K+ uptake (Lebaudy et al., 2007). For example, under normal growth conditions {[K+]ext ∼1 mM; (Epstein et al., 1963; Kochian and Lucas, 1982; Malhotra and Glass, 1995)} K+ uptake in plants is dominated by transport via inward-rectifying K+ channels electrically balanced by the ATP-driven efflux of H+ (Hirsch et al., 1998; Britto and Kronzucker, 2008). Considered in this context our results for whole cells of C. reinhardtii can be interpreted as reflecting K isotope fractionation associated with uptake via K+ channels (

4.2 Higher plants

Our result for K isotope fractionation associated with K+ uptake in C. reinhardtii is similar in sign, though somewhat larger in magnitude, than the K isotope effect associated with K+ uptake estimated by Christensen et al. (2018) in experiments involving higher plants. Those authors analyzed the δ41K values of the roots, stems, and leaves of Triticum aestivum (wheat), Glycine max (soy) and Oryza sativa (rice) grown under hydroponic conditions and observed systematic differences in the δ41K value of the different reservoirs. In particular, roots, stems, and leaves exhibited increasingly negative δ41K values (Supplementary Figure S1). Compared to the freshwater alga C. reinhardtii, quantifying transport-specific K isotope effects in higher plants is more complex as the δ41K value of each individual compartment (root, stem, leaf) reflects a balance between isotopic sources and sinks [e.g., the δ41K value of the root will depend on K isotope effects associated with both net K+ uptake as well as translocation and recycling]. Using a model of K isotope mass balance that includes assumptions regarding plant growth and the partitioning of K+ fluxes between translocation and recycling, Christensen et al. (2018) estimated large K isotope effects for uptake (

4.3 Terrestrial mammals

K+ homeostasis in terrestrial mammals reflects the balance between K+ gained from diet and K+ lost in urine and feces (Figure 2, Figure 3A). This balance is largely achieved by the kidneys and colon, which possess a remarkable ability to sense a change in K+ in the diet and then appropriately adjust K+ loss in response. ECF (which includes blood plasma), the reservoir through which internal K+ is exchanged, represents only 2% of total body K+. Though small, this reservoir is tightly regulated to maintain membrane potential as indicated by the narrow range of normal ECF [K+] (∼ 3.5–5 mEq/L) (Boron and Boulpaep, 2005; McDonough and Youn, 2017). Of the remaining 98% of total body K+, 75% resides in muscle tissues ([K+] ∼ 130 mEq/L) and 23% in non-muscle tissues. Some tissues, particularly skeletal muscle, are critical to K+ homeostasis by providing a buffering reservoir of K+ that can take up K+ after a meal and altruistically donate K+ to ECF to maintain blood plasma levels during fasting (McDonough and Youn, 2017). Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), the body fluid that surrounds the brain and spinal cord of all vertebrates, merits special mention as its K+ content is even more tightly regulated than ECF (Bradbury and Davson, 1965).

4.3.1 External K isotope mass balance in terrestrial mammals

Roughly ∼80–90% of K in the diet is lost in urine with the remainder lost in feces (Agarwal et al., 1994). Uptake of K+ across gut endothelial cells occurs largely paracellularly through pores in tight-junction proteins like claudin-15 (Garcia-Hernandez et al., 2017) as a result of the transmucosal electrical potential difference (Barnaby and Edmonds, 1969). However, transcellular K+ uptake (via pumps) and secretion (via channels) and transcellular secretion has also been shown to occur in gut epithelial cells (Foster et al., 1984; Tsai et al., 2017). As a result, K isotope fractionation associated with net K uptake in the gut will reflect the flux-weighted average of the K isotope fractionation associated with both transcellular and paracellular K+ transport. The observation that feces is characterized by a positive δ41Kdiet value and urine with a slightly negative δ41Kdiet value (Figure 2) indicates that the net K isotope effect associated with K uptake under these conditions (

4.3.2 Internal K isotope mass balance in terrestrial mammals

As shown in Figures 3A, 4, measured δ41K values of the 16 different tissues and fluids analyzed in R. norvegicus fall into 3 distinct categories relative to ECF (δ41Kplasma or δ41KCSF): those with positive δ41Kplasma/CSF values (red blood cells, heart, liver, soleus muscle and brain tissues), those with δ41Kplasma/CSF values that are close to 0 (stomach, adipose tissue, kidney, gastrocnemius, EDL and TA muscles), and those with negative δ41Kplasma/CSF values (urine and CSF).

The timescale for K+ turnover in the studied tissue/cell/fluid reservoirs is rapid [e.g., 0.9–10%/min; (Terner et al., 1950; Jones et al., 1977)]. As a result, for all measured tissues/cells, the δ41K values in Figure 3A can be interpreted as reflecting steady-state K isotope mass balance between the tissue/cell/fluid and the relevant fluid (blood plasma/ECF or CSF). At isotopic steady-state, the δ41K value of K+ entering the reservoir must equal to δ41K value of K+ leaving the reservoir. As a result, reservoirs with δ41Kplasma/CSF values that differ from 0‰ require that net K+ transport in one direction results in greater fractionation of K isotopes than net K+ transport in the opposite direction. For example, reservoirs with positive δ41Kplasma values including red blood cells, heart, liver, and soleus require that K+ transport from ICF to plasma or ECF is associated with a larger K isotope effect than K+ transport from ECF to ICF. The same relationship is observed between brain tissues and CSF (Figure 4). Similarly, reservoirs with δ41Kplasma values that are close to 0‰ require that net K+ transport in both directions does not fractionate K isotopes, i.e., the isotope effects must be of equal magnitude and sign and cancel. These include kidney, adipose tissue, stomach, and gastrocnemius and TA muscles. Finally, the negative δ41Kplasma values for CSF requires that net K+ transport from ECF to CSF through the choroid plexus and blood brain barrier (BBB) is characterized by a K isotope effect that is ∼0.6‰ greater than the K isotope effect associated K+ transport from CSF to ECF (Figure 4).

Quantitatively linking the observed isotopic differences between ECF and ICF of various tissues/cells to the machinery of K+ homeostasis in complex biological systems is complicated by both an incomplete understanding of the machinery involved and limitations of steady-state isotopic mass balance. In particular, although much is known about the identity and molecular structure of the machinery that maintains K+ homeostasis, quantitative information on how each transporter contributes to the gross fluxes of K+ between ICF and ECF at the resting membrane potential is lacking. For example, in red blood cells, probably the best understood with regard to the machinery of K+ homeostasis due to the fundamental role it plays in the regulation of cell volume and longevity (Tosteson and Hoffman, 1960), elevated intercellular K+ is believed to be maintained by a ‘pump-leak’ mechanism where the pump is Na,K-ATPase and the leak is K+ channels (Gardos, 1958). However, red blood cells also show activity for co-transporters such as NKCC (Sachs, 1971; Duhm, 1987) and KCC (Franco et al., 2013), as well as inward-rectifying K+ channels (Hibino et al., 2010), and exactly how much K+ is transported by which transporter at the resting membrane potential is not well known.

In order to evaluate whether or not differences in measured δ41Kplasma values reflect quantitative differences in K+ fluxes through various transporters, we developed a generic model of K homeostasis (Figure 3B) that assumes 1) the tissue/cell is at the resting membrane potential and K is at isotopic steady-state between ECF and ICF, 2) all channels fractionate K isotopes identically (

where

where

As

Two lines of evidence provide additional independent support for our interpretation of δ41Kplasma values as quantitative indicators of the relative importance of K+ loss from ICF via channels (Eq. 3). First, measured δ41Kplasma values are correlated with the activity of NaKATPase (umol Pi/h per g tissue) in tissues where this activity is related to the maintenance of intercellular [K+]. In particular, NaKATPase activity ranges from 91 ± 15 in skeletal muscles, to 253 ± 8 in the liver, and 351 ± 23 in the heart (Gick et al., 1993). All else held constant, higher NaKATPase activity (K+ sources to the ICF via pumps) will lower

4.3.2.1 Urine

Unlike the internal K+ reservoirs discussed above, all of which are interpreted as independent homeostatic systems at isotopic steady-state with respect to ECF (plasma), the loss of K+ through the urine represents the end product of a series of steps each of which may contribute to the observed net K isotope fractionation (e.g., Figure 3B;

4.3.2.2 Cerebrospinal fluid

K+ in CSF reflects a balance between paracellular and transcellular K+ transport across endothelial cells at the blood-brain-barrier (BBB) and paracellular K+ transport of across epithelial cells of the choroid plexus (Hladky and Barrand, 2016). Gross fluxes of K+ into the brain across the BBB are 4x larger than those associated with the choroid plexus (Katzman et al., 1965), suggesting that the observed net K isotope effects may be largely due to fractionation associated with transport across the BBB. However, K+ transport from ECF to CSF through the choroid plexus is thought to occur by paracellular routes through pores in tight junctions (Figure 4), a process that we expect to fractionate K isotopes and thus may contribute to the observed negative δ41Kplasma values for CSF. With regards to K+ transport across the BBB, both paracellular (through tight-junction pores) and transcellular (through BBB endothelial cells) routes may be important (Hladky and Barrand, 2016). Again, we expect paracellular K+ transport through tight junction pores to be associated with a larger K isotope effect whereas any K isotope effects associated with transcellular transport will depend on the internal cycling of K+ (and associated isotope effects) within endothelial BBB cells (pumps, (Betz et al., 1980); co-transporters, (Foroutan et al., 2005); and channels, (Van Renterghem et al., 1995)). Overall, the observation of large K isotope fractionation associated with the transport of K+ from plasma to CSF (Figure 5;

4.4 Stenohaline and euryhaline marine fish

K+ homeostasis in both euryhaline and stenohaline marine fish is linked to ionic and osmotic regulation (Figure 5). While K+ sources include ingestion of seawater and diet (Hickman Jr, 1968), by far the largest K+ source is transport across the gills (Maetz, 1969), which are permeable to monovalent cations (Na+, K+) and anions (Cl−). Fish balance this salt intake by actively secreting Na+, K+, and Cl− through mitochondria-rich cells (MRCs) of the gills and paracellularly through tight-junction proteins (claudins) in the gill epithelium (Evans et al., 2005; Kolosov et al., 2013). K+ loss is not well-understood but recent discoveries of apical ROMK channels indicate that transcellular secretion through MRCs is likely an important pathway (Furukawa et al., 2012). Both stenohaline and euryhaline marine fish possess this capability but euryhaline marine fish have evolved the ability to adapt this machinery to a wide range of water salinities by adjusting expression of ROMK and tight junction claudins (Furukawa et al., 2012; Kolosov et al., 2013; Furukawa et al., 2014; Furukawa et al., 2015).

In seawater adapted stenohaline and euryhaline marine fish, K+ homeostasis can be approximated as a balance between gain of K+ across tight-junctions in the gill epithelium and loss of K+ through apical ROMK channels in MRCs (Figure 5B). Other potential sources and sinks of K+ including the ingestion of seawater, diet, and excretion are either small compared to the fluxes of K+ across the gills (Maetz, 1969) or transient in nature and unlikely to explain the systematic difference we observe between the δ41Kseawater values of stenohaline and euryhaline fish. Furthermore, as most of the total K+ content of fish resides in muscle tissue, the δ41Kseawater value of the muscle can be used as a reasonable approximation of the δ41Kseawater value of the whole organism (Figure 5B). At steady-state

which reduces to:

where

where

But is there any independent evidence that K homeostasis in MRCs in stenohaline marine fish operates close to a perfect “pump-leak” (

5 Conclusion

The results presented here demonstrate that K+ homeostasis in biological systems is associated with systematic variability in 41K/39K ratios and strongly suggests that K+ transport through channels and tight-junction proteins is associated with greater fractionation of K isotopes than transport via pumps and co-transporters. Using results from 3 biological systems (algae, mammals, and fish) we developed a simple framework for interpreting differences in measured δ41K values between intercellular fluid (ICF) and extracellular fluid (ECF) and between different internal fluid reservoirs (e.g., blood plasma and cerebrospinal fluid). If correct, this framework permits quantification of the relative importance of K+ channels and pump/cotransporters in different physiological states–e.g., K depletion/excess—in situ (e.g.,

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The animal study was reviewed and approved by USC Keck School of Medicine.

Author contributions

JH, AM, JY, DSR, and CS designed the research. JH, DSR, DH, SK, SG, and CS carried out the experiments and associated analytical measurements. JH, AM, JY, DSR, and CS interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors were involved in the revising of the manuscript.

Funding

JH, JY, AM thank the University Kidney Research Organization (URKO) for funding.

Acknowledgments

CS acknowledges the sabbatical program at the Faculty of Science, University of Gothenburg, and thanks Martin C. Jonikas for the Chlamydomonas experiments performed in his laboratory at Princeton University. JH, AM, and JY thank the University Kidney Research Organization (UKRO) for financial support. Anne Pearson is thanked for helpful reviews on an earlier version of this manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphys.2022.1016242/full#supplementary-material

References

Agarwal R., Afzalpurkar R., Fordtran J. S. (1994). Pathophysiology of potassium absorption and secretion by the human intestine. Gastroenterology 107, 548–571. doi:10.1016/0016-5085(94)90184-8

Barnaby C. F., Edmonds C. J. (1969). Use of a miniature GM counter and a whole body counter in the study of potassium transport by the colon of normal, sodium-depleted and adrenalectomized rats in vivo. J. Physiol. 205, 647–665. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.1969.sp008988

Berneche S., Roux B. (2003). A microscopic view of ion conduction through the K+ channel. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100, 8644–8648. doi:10.1073/pnas.1431750100

Betz A. L., Firth J. A., Goldstein G. W. (1980). Polarity of the blood-brain barrier: Distribution of enzymes between the luminal and antiluminal membranes of brain capillary endothelial cells. Brain Res. 192, 17–28. doi:10.1016/0006-8993(80)91004-5

Boron W. F., Boulpaep E. L. (2005). Medical physiology. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Elsevier Saunders.

Bradbury M., Davson H. (1965). The transport of potassium between blood, cerebrospinal fluid and brain. J. Physiol. 181, 151–174. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.1965.sp007752

Britto D. T., Kronzucker H. J. (2008). Cellular mechanisms of potassium transport in plants. Physiol. Plant. 133, 637–650. doi:10.1111/j.1399-3054.2008.01067.x

Chasiotis H., Kolosov D., Bui P., Kelly S. (2012). Tight junctions, tight junction proteins and paracellular permeability across the gill epithelium of fishes: A review. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 184, 269–281. doi:10.1016/j.resp.2012.05.020

Christensen J. N., Qin L., Brown S. T., DePaolo D. J. (2018). Potassium and calcium isotopic fractionation by plants (soybean [Glycine max], rice [Oryza sativa], and wheat [Triticum aestivum]). ACS Earth Space Chem. 2, 745–752. doi:10.1021/acsearthspacechem.8b00035

Duhm J. (1987). Furosemide-sensitive K+ (Rb+) transport in human-erythrocytes - modes of operation, dependence on extracellular and intracellular Na+, kinetics, pH dependency, and the effect of cell-volume and N-ethylmaleimide. J. Membr. Biol. 98, 15–32. doi:10.1007/BF01871042

Epstein E., Rains D., Elzam O. (1963). Resolution of dual mechanisms of potassium absorption by barley roots. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 49, 684–692. doi:10.1073/pnas.49.5.684

Epstein F. H., Katz A. I., Pickford G. E. (1967). Sodium- and potassium-activated adenosine triphosphatase of gills: Role in adaptation of teleosts to salt water. Science 156, 1245–1247. doi:10.1126/science.156.3779.1245

Evans D. H., Piermarini P. M., Choe K. P. (2005). The multifunctional fish gill: Dominant site of gas exchange, osmoregulation, acid-base regulation, and excretion of nitrogenous waste. Physiol. Rev. 85, 97–177. doi:10.1152/physrev.00050.2003

Foroutan S., Brillault J., Forbush B., O’Donnell M. E. (2005). Moderate-to-severe ischemic conditions increase activity and phosphorylation of the cerebral microvascular endothelial cell Na+-K+-Cl− cotransporter. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 289, C1492–C1501. doi:10.1152/ajpcell.00257.2005

Foster E. S., Hayslett J. P., Binder H. J. (1984). Mechanism of active potassium absorption and secretion in the rat colon. Am. J. Physiol. 246, G611–G617. doi:10.1152/ajpgi.1984.246.5.G611

Franco R. S., Puchulu-Campanella M. E., Barber L. A., Palascak M. B., Joiner C. H., Low P. S., et al. (2013). Changes in the properties of normal human red blood cells during in vivo aging. Am. J. Hematol. 88, 44–51. doi:10.1002/ajh.23344

Furukawa F., Watanabe S., Kakumura K., Hiroi J., Kaneko T. (2014). Gene expression and cellular localization of ROMKs in the gills and kidney of Mozambique tilapia acclimated to fresh water with high potassium concentration. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 307, R1303–R1312. doi:10.1152/ajpregu.00071.2014

Furukawa F., Watanabe S., Kimura S., Kaneko T. (2012). Potassium excretion through ROMK potassium channel expressed in gill mitochondrion-rich cells of Mozambique tilapia. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 302, R568–R576. doi:10.1152/ajpregu.00628.2011

Furukawa F., Watanabe S., Seale A. P., Breves J. P., Lerner D. T., Grau E. G., et al. (2015). In vivo and in vitro effects of high-K+ stress on branchial expression of ROMKa in seawater-acclimated Mozambique tilapia. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 187, 111–118. doi:10.1016/j.cbpa.2015.05.017

Garcia-Hernandez V., Quiros M., Nusrat A. (2017). Intestinal epithelial claudins: Expression and regulation in homeostasis and inflammation. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1397, 66–79. doi:10.1111/nyas.13360

Gardos G. (1958). The function of calcium in the potassium permeability of human erythrocytes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 30, 653–654. doi:10.1016/0006-3002(58)90124-0

Gaymard F., Pilot G., Lacombe B., Bouchez D., Bruneau D., Boucherez J., et al. (1998). Identification and disruption of a plant shaker-like outward channel involved in K+ release into the xylem sap. Cell 94, 647–655. doi:10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81606-2

Gick G. G., Hatala M. A., Chon D., Ismail-Beigi F. (1993). Na, K-ATPase in several tissues of the rat: Tissue-specific expression of subunit mRNAs and enzyme activity. J. Membr. Biol. 131, 229–236. doi:10.1007/BF02260111

Gierth M., Mäser P. (2007). Potassium transporters in plants–involvement in K+ acquisition, redistribution and homeostasis. FEBS Lett. 581, 2348–2356. doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2007.03.035

Hibino H., Inanobe A., Furutani K., Murakami S., Findlay I., Kurachi Y. (2010). Inwardly rectifying potassium channels: Their structure, function, and physiological roles. Physiol. Rev. 90, 291–366. doi:10.1152/physrev.00021.2009

Hickman C. P. (1968). Ingestion, intestinal absorption, and elimination of seawater and salts in the southern flounder, Paralichthys lethostigma. Can. J. Zool. 46, 457–466. doi:10.1139/z68-063

Hirsch R. E., Lewis B. D., Spalding E. P., Sussman M. R. (1998). A role for the AKT1 potassium channel in plant nutrition. Science 280, 918–921. doi:10.1126/science.280.5365.918

Hladky S. B., Barrand M. A. (2016). Fluid and ion transfer across the blood–brain and blood–cerebrospinal fluid barriers; a comparative account of mechanisms and roles. Fluids Barriers CNS 13, 19–69. doi:10.1186/s12987-016-0040-3

Hofmann A. E., Bourg I. C., DePaolo D. J. (2012). Ion desolvation as a mechanism for kinetic isotope fractionation in aqueous systems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 109, 18689–18694. doi:10.1073/pnas.1208184109

Jampol L. M., Epstein F. H. (1970). Sodium-potassium-activated adenosine triphosphatase and osmotic regulation by fishes. Am. J. Physiol. 218, 607–611. doi:10.1152/ajplegacy.1970.218.2.607

Jones A. W., Sander P. D., Kampschmidt D. L. (1977). The effect of norepinephrine on aortic 42K turnover during deoxycorticosterone acetate hypertension and antihypertensive therapy in the rat. Circ. Res. 41, 256–260. doi:10.1161/01.res.41.2.256

Katzman R., Graziani L., Kaplan R., Escriva A. (1965). Exchange of cerebrospinal fluid potassium with blood and brain: Study in normal and ouabain perfused cats. Arch. Neurol. 13, 513–524. doi:10.1001/archneur.1965.00470050061007

Kochian L. V., Lucas W. J. (1982). Potassium transport in corn roots: I. Resolution of kinetics into a saturable and linear component. Plant Physiol. 70, 1723–1731. doi:10.1104/pp.70.6.1723

Kolosov D., Bui P., Chasiotis H., Kelly S. P. (2013). Claudins in teleost fishes. Tissue barriers. 1, e25391. doi:10.4161/tisb.25391

Kopec W., Köpfer D. A., Vickery O. N., Bondarenko A. S., Jansen T. L., De Groot B. L., et al. (2018). Direct knock-on of desolvated ions governs strict ion selectivity in K+ channels. Nat. Chem. 10, 813–820. doi:10.1038/s41557-018-0105-9

Lacombe B., Pilot G., Michard E., Gaymard F., Sentenac H., Thibaud J.-B. (2000). A shaker-like K+ channel with weak rectification is expressed in both source and sink phloem tissues of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 12, 837–851. doi:10.1105/tpc.12.6.837

Lebaudy A., Véry A.-A., Sentenac H. (2007). K+ channel activity in plants: Genes, regulations and functions. FEBS Lett. 581, 2357–2366. doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2007.03.058

Li W., Kwon K. D., Li S., Beard B. L. (2017). Potassium isotope fractionation between K-salts and saturated aqueous solutions at room temperature: Laboratory experiments and theoretical calculations. Geochimica Cosmochimica Acta 214, 1–13. doi:10.1016/j.gca.2017.07.037

Maetz J. (1969). Seawater teleosts: Evidence for a sodium-potassium exchange in the branchial sodium-excreting pump Science 166, 613–615. doi:10.1126/science.166.3905.613

Malhotra B., Glass A. D. (1995). Potassium fluxes in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (I. Kinetics and electrical potentials). Plant Physiol. 108, 1527–1536. doi:10.1104/pp.108.4.1527

Marchand J., Heydarizadeh P., Schoefs B., Spetea C. (2020). “Chloroplast ion and metabolite transport in algae,” in Photosynthesis in algae: Biochemical and physiological mechanisms. Editors A. W. D. Larkum, A. R. Grossman, and J. A. Raven (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 107–139.

McDonough A. A., Youn J. H. (2017). Potassium homeostasis: The knowns, the unknowns, and the health benefits. Physiol. (Bethesda) 32, 100–111. doi:10.1152/physiol.00022.2016

Mironenko A., Zachariae U., de Groot B. L., Kopec W. (2021). The persistent question of potassium channel permeation mechanisms. J. Mol. Biol. 433, 167002. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2021.167002

Morgan L. E., Ramos D. P. S., Davidheiser-Kroll B., Faithfull J., Lloyd N. S., Ellam R. M., et al. (2018). High-precision 41K/39K measurements by MC-ICP-MS indicate terrestrial variability of δ41K. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 33, 175–186. doi:10.1039/c7ja00257b

Mulkidjanian A. Y., Bychkov A. Y., Dibrova D. V., Galperin M. Y., Koonin E. V. (2012). Origin of first cells at terrestrial, anoxic geothermal fields. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 109, E821–E830. doi:10.1073/pnas.1117774109

Noble E. E., Hahn J. D., Konanur V. R., Hsu T. M., Page S. J., Cortella A. M., et al. (2018). Control of feeding behavior by cerebral ventricular volume transmission of melanin-concentrating hormone. Cell Metab. 28, 55–68. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2018.05.001

Pilot G., Lacombe B. t., Gaymard F., Chérel I., Boucherez J., Thibaud J.-B., et al. (2001). Guard cell inward K+ channel activity inarabidopsis involves expression of the twin channel subunits KAT1 and KAT2. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 3215–3221. doi:10.1074/jbc.M007303200

Ramos D. P. S., Coogan L. A., Murphy J. G., Higgins J. A. (2020). Low-temperature oceanic crust alteration and the isotopic budgets of potassium and magnesium in seawater. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 541, 116290. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2020.116290

Ramos D. P. S., Morgan L. E., Lloyd N. S., Higgins J. A. (2018). Reverse weathering in marine sediments and the geochemical cycle of potassium in seawater: Insights from the K isotopic composition (K-41/K-39) of deep-sea pore-fluids. Geochimica Cosmochimica Acta 236, 99–120. doi:10.1016/j.gca.2018.02.035

Rolfe D. F., Brown G. C. (1997). Cellular energy utilization and molecular origin of standard metabolic rate in mammals. Physiol. Rev. 77, 731–758. doi:10.1152/physrev.1997.77.3.731

Roux B. (2017). Ion channels and ion selectivity. Essays Biochem. 61, 201–209. doi:10.1042/EBC20160074

Rui H., Artigas P., Roux B. (2016). The selectivity of the Na+/K+-pump is controlled by binding site protonation and self-correcting occlusion. Elife 5, e16616. doi:10.7554/eLife.16616

Sachs J. R. (1971). Ouabain-insensitive sodium movements in the human red blood cell J. Gen. Physiol. 57, 259–282. doi:10.1085/jgp.57.3.259

Stautz J., Hellmich Y., Fuss M. F., Silberberg J. M., Devlin J. R., Stockbridge R. B., et al. (2021). Molecular mechanisms for bacterial potassium homeostasis. J. Mol. Biol. 433, 166968. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2021.166968

Terner C., Eggleston L., Krebs H. (1950). The role of glutamic acid in the transport of potassium in brain and retina. Biochem. J. 47, 139–149. doi:10.1042/bj0470139

Tosteson D. C., Hoffman J. F. (1960). Regulation of cell volume by active cation transport in high and low potassium sheep red cells. J. Gen. Physiol. 44, 169–194. doi:10.1085/jgp.44.1.169

Tsai P.-Y., Zhang B., He W.-Q., Zha J.-M., Odenwald M. A., Singh G., et al. (2017). IL-22 upregulates epithelial claudin-2 to drive diarrhea and enteric pathogen clearance. Cell Host Microbe 21, 671–681. e674. doi:10.1016/j.chom.2017.05.009

Van Renterghem C., Vigne P., Frelin C. (1995). A charybdotoxin‐sensitive, Ca2+‐activated K+ channel with inward rectifying properties in brain microvascular endothelial cells: Properties and activation by endothelins. J. Neurochem. 65, 1274–1281. doi:10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.65031274.x

Wang K., Jacobsen S. B. (2016). An estimate of the Bulk Silicate Earth potassium isotopic composition based on MC-ICPMS measurements of basalts. Geochimica Cosmochimica Acta 178, 223–232. doi:10.1016/j.gca.2015.12.039

Youn J. H., McDonough A. A. (2009). Recent advances in understanding integrative control of potassium homeostasis. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 71, 381–401. doi:10.1146/annurev.physiol.010908.163241

Yu H., Noskov S. Y., Roux B. (2010). Two mechanisms of ion selectivity in protein binding sites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107, 20329–20334. doi:10.1073/pnas.1007150107

Keywords: potassium, homeostasis, stable isotope, physiology, potassium channel, Na-K ATPase

Citation: Higgins JA, Ramos DS, Gili S, Spetea C, Kanoski S, Ha D, McDonough AA and Youn JH (2022) Stable potassium isotopes (41K/39K) track transcellular and paracellular potassium transport in biological systems. Front. Physiol. 13:1016242. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2022.1016242

Received: 11 August 2022; Accepted: 21 September 2022;

Published: 26 October 2022.

Edited by:

Qin Xu, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, ChinaReviewed by:

Xin Cong, Peking University, ChinaLi Zuo, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, United States

Copyright © 2022 Higgins, Ramos, Gili, Spetea, Kanoski, Ha, McDonough and Youn. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: John A. Higgins, amFoaWdnaW5AcHJpbmNldG9uLmVkdQ==

John A. Higgins

John A. Higgins Danielle Santiago Ramos

Danielle Santiago Ramos Stefania Gili

Stefania Gili Cornelia Spetea

Cornelia Spetea Scott Kanoski

Scott Kanoski Darren Ha

Darren Ha Alicia A. McDonough

Alicia A. McDonough Jang H. Youn

Jang H. Youn