95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

MINI REVIEW article

Front. Physiol. , 22 April 2020

Sec. Striated Muscle Physiology

Volume 11 - 2020 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2020.00384

This article is part of the Research Topic Pathogenic Mechanisms in Cardiac and Skeletal Muscle Diseases View all 15 articles

Non-genetic cardiac pathologies develop as an aftermath of extracellular stress-conditions. Nevertheless, the response to pathological stimuli depends deeply on intracellular factors such as physiological state and complex genetic backgrounds. Without a thorough characterization of their in vitro phenotype, modeling of maladaptive hypertrophy, ischemia and reperfusion injury or diabetes in human pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes (hPSC-CMs) has been more challenging than hereditary diseases with defined molecular causes. In past years, greater insights into hPSC-CM in vitro physiology and advancements in technological solutions and culture protocols have generated cell types displaying stress-responsive phenotypes reminiscent of in vivo pathological events, unlocking their application as a reductionist model of human cardiomyocytes, if not the adult human myocardium. Here, we provide an overview of the available literature of pathology models for cardiac non-genetic conditions employing healthy (or asymptomatic) hPSC-CMs. In terms of numbers of published articles, these models are significantly lagging behind monogenic diseases, which misrepresents the incidence of heart disease causes in the human population.

Nearly two decades since their first description (Kehat et al., 2001), hPSC-CMs are beginning to fulfill their potential as a reductionist model of the human cardiac muscle. Thanks to constant improvements in differentiation protocols (Mummery et al., 2003; Laflamme et al., 2007; Yang et al., 2008; Kattman et al., 2011; Lian et al., 2012; Burridge et al., 2014) and increasing understanding of their in vitro cardiac phenotype, hPSC-CMs are now an integral part of proposed high-throughput drug screening (Kirby et al., 2018; Fiedler et al., 2019) and drug risk-assessment platforms (Yang and Papoian, 2018; Lu H.R. et al., 2019; Li et al., 2020). Furthermore, there is evidence for their increasing reliability in predicting adverse drug effects (Blinova et al., 2018).

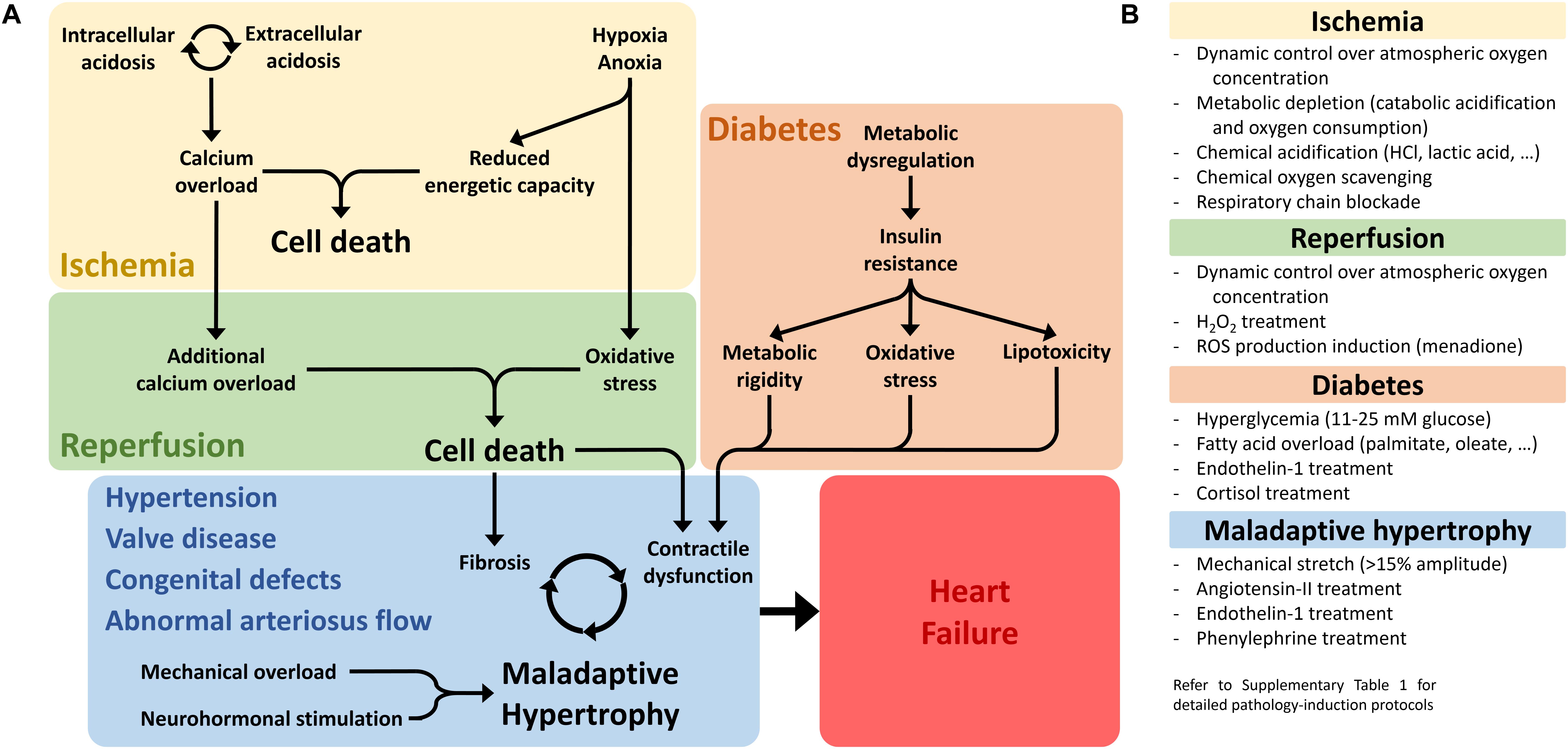

The successful induction of pluripotency in human somatic cells (Takahashi et al., 2007; Yu et al., 2007; Lowry et al., 2008; Park et al., 2008) opened the cardiac field to patient-specific disease modeling (Carvajal-Vergara et al., 2010; Moretti et al., 2010), although patient-specific treatment modeling still remains an open challenge (Blinova et al., 2019). The race toward generating mutation-specific in vitro models produced >150 independent hiPSC lines over the past 10 years and hundreds of scientific papers frequently and comprehensively reviewed (Ross et al., 2018; van Mil et al., 2018; van den Brink et al., 2019). Consequently, there is a clear literature unbalance against non-genetic cardiac pathology models, often coming with additional challenges in recreating in vitro either the pathological phenotype, the pathological environment or both (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Non-genetic pathological conditions leading to heart failure. (A) The three main pathological conditions discussed in this review are schematically represented, highlighting the major molecular drivers and pathological phenotypes that need to be reproduced in vitro in order to generate a representative and reliable pathology model. (B) Main experimental strategies employed to generate pathological phenotypes in non-genetic cardiac disease models in vitro. For detailed experimental protocols employed in the reviewed studies, see Supplementary Materials.

Here, we discuss modeling of non-genetic heart conditions, focusing exclusively on results obtained on human cells when the referenced study makes only sparing use of hPSC-CMs

Inter-species differences are a major concern in translational research. Therefore, the human origin paired with virtually unlimited low-cost supply constitute the most valuable advantages of hPSC-CMs. Beyond the most often quoted heart size, beating rate, electrophysiology and protein function (Nerbonne et al., 2001; Haghighi et al., 2003), more subtle differences are apparent also in stress-responses. For instance, an in vitro angiotensin-II-induced heart failure model reproduces the appearance observed in failing myocardia of two loss-of-function NaV1.5 channel isoforms produced by abnormal SCN5A splicing through a mechanism absent in species other than primates (Gao et al., 2011, 2013). Such response contributes to the sodium current reduction in angiotensin-II-treated hPSC-CMs, mimicking pro-arrhythmic conditions in failing ventricles (Mathieu et al., 2016). Similarly, evolutionarily closer species display divergent transcriptomic responses to ischemia-mimetic environments, with rhesus macaque monkey PSC-CMs failing to overlap results with hPSC-CMs at gene regulation level (Zhao et al., 2018), and chimpanzee PSC-CMs still diverging in regulation of critical genes tightly related to human ischemia/reperfusion pathogenesis (Ward and Gilad, 2019).

Although hPSC-CMs can develop full adult phenotypes, these have been achieved so far only by integration within healthy animal myocardia (Cho et al., 2017; Kadota et al., 2017), and hPSC-CM developmental immaturity is seen as their major drawback. We (Martewicz et al., 2019) and others (van den Berg et al., 2015) have shown that transcriptomic profiling places hPSC-CMs within the first trimester of fetal development, with structural, functional and metabolic features further supporting such characterization (Machiraju and Greenway, 2019).

Nevertheless, unprimed hPSC-CMs (no maturation protocol applied) still represent a valid reductionist model in dissecting molecular mechanisms within human and cardiac cell backgrounds. For instance, a recent study successfully identified direct inactivation mechanisms of human voltage-sensitive L-type calcium channels by molecular O2 and acidosis (Fernandez-Morales et al., 2019), complementing our findings in murine models (Martewicz et al., 2012). Simultaneously, the authors clearly show how studying more complex functional features requires careful evaluation of cardiac structural maturation, with whole-cell ion dynamics changing following substrate interaction, which our group showed to be mediated by mechanotransduction signaling (Martewicz et al., 2017).

Additionally, taking advantage of developmentally early phenotypes of hPSC-CM and hijacking the differentiation process from hPSCs allows modeling developmental defects leading to postnatal pathological conditions. Such is the case of hypoplastic left heart syndrome in a chronic-hypoxia model (Gaber et al., 2013), which preceded patient-specific hPSC-CMs models ultimately identifying the underlying genetic-driven molecular mechanisms (Jiang et al., 2014; Kobayashi et al., 2014; Tomita-Mitchell et al., 2016; Hrstka et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2017). Similarly, hPSC-CMs were used to model the role of the mitochondrial calcium uniporter in cardiac fetal development and maturation (Shanmughapriya et al., 2018). Finally, although chemically induced cardiotoxicity will not be a subject of this review [see (Magdy et al., 2018)], one recent study considered the impact of ethanol on hPSC-CM functionality as a model of prenatal exposure during maternal alcohol intoxication (Rampoldi et al., 2019).

The developmentally early phenotype of hPSC-CMs provides additional complexity in modeling hypertrophy in vitro, with differentiation/maturation phenomena blurring distinctions between physiological and pathological hypertrophy. Physiological hypertrophic growth is a cardiac perinatal maturation process, reactivated in adulthood upon regular physical activity, and differs substantially from pathological (or maladaptive) hypertrophy in activation mechanisms and elicited functional responses (McMullen and Jennings, 2007). For instance, the evaluation of cell-size increase must be performed carefully, being an ambivalent hallmark for both processes (Rupert et al., 2017), and appears to be absent in advanced maturation stages (Ronaldson-Bouchard et al., 2018). Similarly ambivalent is the application of mechanical stretch, which simultaneously induces hypertrophic responses and promotes hPSC-CM maturation (LaBarge et al., 2019), generating phenotypes divergent from pathological neurohormonal stimulation relative to αMHC/βMHC transcription activation ratios (Foldes et al., 2011) or CathepsinD/TroponinT release (Hoes et al., 2019).

Chronic adrenergic activation is one of the pathogenic triggers of maladaptive hypertrophy, and the effects of prolonged exposure to isoproterenol or phenylephrine have been studied in hPSC-CMs in regard to hypertrophy-inhibiting effects of several active compounds (Foldes et al., 2011; Martin et al., 2014; Gesmundo et al., 2017). Nevertheless, the reliability of this approach is hindered by hPSC-CM immature adrenergic signaling (Jung et al., 2016; Uzun et al., 2016; Trieschmann et al., 2019), which generates highly variable and aberrant stress-responses (Foldes et al., 2014) often failing to produce representative pathological phenotypes in vitro (Tanaka et al., 2014; Cui et al., 2016; Naftali-Shani et al., 2018).

Hormonal stimulation has been shown to be more effective for maladaptive hypertrophy modeling purposes, with angiotensin-II and especially endothelin-1 treatments successfully recapitulating hypertrophic phenotypes in terms of expression/secretion of natriuretic peptides A and B (Carlson et al., 2013), myofibrillar disarray (Tanaka et al., 2014) and mRNA/miRNA profiling (Aggarwal et al., 2014). Such a model has been dually employed thus far to study the molecular mechanisms of maladaptation in vitro (Cui et al., 2016; Rosales and Lizcano, 2018), and evaluate anti-hypertrophic effects of miRNAs (Scrimgeour et al., 2019), herbal extracts (Zhang et al., 2017) and antiparasitic compounds (Qin et al., 2017), for which hPSC-CMs are superior to murine cardiac cell lines lacking in expression of several key target proteins (Nagai et al., 2017).

Alternatively to being employed as in vitro hypertrophy modeling platform, hPSC-CMs have proven useful in experimentally confirming observations made in human and murine hypertrophic heart biopsies of the involvement of non-coding RNAs in maladaptive pathogenesis (Wang et al., 2016; Mirtschink et al., 2019).

Ischemia is the most dramatic of cardiac insults, leading to or aggravating pre-existing stages of heart failure. The nature of the pathological stressors (a composite of fast dynamic changes in nutrients, waste products, O2 and ROS) makes cellular responses and pathological fallouts tightly connected to adult cardiomyocyte metabolic processes, elevating hPSC-CM maturation to a necessity for modeling purposes.

Indeed, several studies describe little or no response to I/R-mimetic conditions in unprimed hPSC-CMs, although showing minimal but relatively significant cardioprotection by the individual molecules of interest (Hsieh et al., 2015; Wei et al., 2017; Mo et al., 2019). Our own experiments with oxygen/glucose deprivation in microfluidic devices show clearly divergent responses of postnatal murine cardiomyocytes and unprimed hPSC-CMs characterized by abnormal intracellular glycogen stores (Martewicz et al., 2018). Similar experimental setups have been used to study the mechanistic action of anesthetics (Lu Y. et al., 2019) and miRNA-based regulation of metalloproteases (Scrimgeour et al., 2019).

Recent studies demonstrate how developing a stress-responsive phenotype must be set as an essential element in a feasible hPSC-CM model for I/R studies. Priming hPSC-CMs through simple maturation steps generates cells responsive to I/R with mortality rates unseen in their unprimed counterparts, ultimately providing the biological model needed to test clinically effective small molecules (Hidalgo et al., 2018) or investigate the cardioprotective mechanism of cardiac progenitors (Sebastiao et al., 2019). The most intriguing example of in vitro I/R modeling to date fully embraces hPSC-CMs as platform for both drug screening and development (Fiedler et al., 2019). The researchers identify MAP4K4 as a druggable target, activity of which is altered across several clinically relevant heart failure models, and employ an I/R setup with primed hPSC-CMs to screen for suitable small-molecule inhibitors. After using the identified lead-compound to develop a novel inhibitor, they ultimately translate the cardioprotective properties of a small-molecule newly developed in hPSC-CMs to an in vivo murine model of ischemic insult.

Similar to ischemia models, replicating diabetic pathophysiology in vitro requires primed hPSC-CMs as starting point. While underlying genetic factors might further its severity, prolonged exposure to altered metabolic stimuli is the leading trigger and driving force of the clinical manifestations of diabetic cardiomyopathy (Graneli et al., 2019). Indeed, an I/R model that linked anesthetic-conferred cardioprotection to pharmacological tuning of mitochondrial function in hPSC-CMs (Sepac et al., 2010; Canfield et al., 2016) produced no differences between diabetic patient-specific cells and healthy controls. Both showed equal abrogation of protection under acute hyperglycemic conditions, thus failing to replicate the clinical differences between healthy and diabetic surgery patients (Canfield et al., 2012).

On the other hand, when allowed to adapt to prolonged exposure to hyperglycemic stress, hPSC-CMs develop pathological hypertrophy characterized by contractile and calcium cycling dysfunctions (Ng et al., 2018). Capitalizing on this phenotype has enabled investigations into mechanisms behind unexpected clinical trial evidence of empagliflozin-driven reduction of deadly cardiovascular complications in diabetic patients. Similar approaches of metabolic overload with fatty acids allow the induction of insulin-resistance and dissection of its mechanism in hPSC-CMs (Chanda et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2017; Graneli et al., 2019).

Primed hPSC-CMs develop a complete panel of diabetic cardiomyopathy phenotypes by integrating metabolic overload conditions with additional hormonal stimulation abnormally present in the diabetic milieu (Idris-Khodja et al., 2016; Joseph and Golden, 2017), proven by aggravated contractile dysfunction following endothelin-1 stimulation (Wu et al., 2018). A complete set of stressors (metabolic overload, endothelin-1 and cortisol treatment) recapitulates in vitro hypertrophic-like transcriptomic changes, increased BNP secretion, compromised calcium cycling and contraction, lipid accumulation and oxidation, sarcomeric disorganization (Drawnel et al., 2014), insulin-resistance and reduced respiratory capacity (Graneli et al., 2019), and deregulated non-coding RNAs expression (Pant et al., 2019). Satisfying all of these conditions in such a multifactorial pathological setting provides the necessary platform for drug-screening experiments and is instrumental in revealing underlying differences between healthy and patient-derived hPSC-CMs (Drawnel et al., 2014).

Hypertrophy, ischemia/reperfusion and diabetes are conditions with major economic and social impacts. Nevertheless, hPSC-CMs have been also employed in modeling less common pathological settings, such as systemic pathogen infections leading to myocarditis and heart failure. Modeling septic shock by exposure to bacterial lipopolysaccharides affects hPSC-CM survival, electrophysiology and demonstrates their competence in activating innate immune inflammatory responses (Yucel et al., 2017). Indeed, hPSC-CM display stronger macrophage chemo-attractant properties than purified chemokines (Pallotta et al., 2015) and significant stress-responsive paracrine pro-inflammatory signaling (Sebastiao et al., 2020) mediating fibrosis in vivo and in vitro (Kumar et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2019). Furthermore, functional expression of coxsackievirus and adenovirus receptor (Scassa et al., 2011) makes hPSC-CMs a better predictive model than murine cardiac cell lines for therapeutic approaches against viral myocarditis (Sharma et al., 2014). Similarly, hPSC-CMs are a viable host for parasites causing Chagas disease (da Silva Lara et al., 2018; Bozzi et al., 2019) and, consequently, a good screening platform for novel drugs preventing infection and major cardiac fallouts of the pathology (Sass et al., 2019a, b).

Spaceflight-associated stressors such as radiation and microgravity induce cardiac atrophy and arrhythmias, increasing cardiovascular complication rates in astronauts (Acharya et al., 2019). Thus far, the intrinsic challenges of hPSC-CM aerospace applications limit in vitro models to phenotypic descriptions, orphan of underlying molecular mechanisms. Microgravity modeling, for instance, has been performed only twice on human PSC-CMs, observing increases in beating rate under acute conditions during parabolic flight (Acharya et al., 2019) and mainly transcriptomic changes during chronic exposure onboard the International Space Station (Wnorowski et al., 2019). Although studied relative to anti-cancer treatment, radiation-induced heart disease is another astronaut concern, and hPSC-CMs respond to ionizing radiations in dose-dependent manner with electrophysiological (Becker et al., 2018b) and transcriptomic (Becker et al., 2018a) alterations.

hPSC-CM maturation in vitro is relatively fast in comparison with in vivo development, supporting the idea that these mechanisms differ substantially. Thus, modeling non-genetic pathologies mostly originating from insults to the adult heart in the late stages of cardiac development is within reach of 1,2 month-long cultures. While originally proposed as a maturation mechanism (Sartiani et al., 2007; Otsuji et al., 2010; Kamakura et al., 2013; Lundy et al., 2013), extended time in culture was recently extensively characterized over a 4-month period showing expression of aging markers in unprimed hPSC-CMs and increased sensitivity to I/R in disorganized 3D aggregates (Acun et al., 2019). To date, human engineered heart tissues (hEHTs) provide the closest match to an adult cardiomyocyte phenotype in vitro (Tiburcy et al., 2017; Ronaldson-Bouchard et al., 2018).

hEHTs assemble hPSC-CMs into 3D constructs integrating multifactorial stimuli such as electrophysiological pacing (Lemme et al., 2019; Zhao et al., 2019), mechanical loading (Leonard et al., 2018), ECM structure (Goldfracht et al., 2019) and non-myocyte cell interactions (Varzideh et al., 2019). Such constructs, in their immature state, have been proposed as models to study human cardiac self-regenerative potential after localized injury (Voges et al., 2017), and produce structurally and metabolically primed hPSC-CMs when allowed to develop further, even in absence of additional stimuli (Ulmer et al., 2018).

A recent hEHT I/R model showed for the first time in human cells the cardioprotective effect of ischemic preconditioning and efficacy of one out of three proposed cardioprotection treatments for reperfusion injury (Chen and Vunjak-Novakovic, 2019). Nevertheless, similar hEHTs generated by pure hPSC-CM populations are limited in their maturation potential (Park et al., 2019) and limit the study of the complex bidirectional crosstalk of multiple cell types, important during ischemic stress via paracrine signaling (Sandstedt et al., 2018; Sebastiao et al., 2019, 2020) and neurohormonal stimulation. The latter can be effectively modeled solely with hEHTs, as 2D cultures lack or display functionally impaired a β-adrenergic signaling cascades (Jung et al., 2016; Uzun et al., 2016; Trieschmann et al., 2019), despite being able to form functional sympathetic neuro-junctions (Sakai et al., 2017). Indeed, chronic exposure of hEHTs to norepinephrine induces contractile dysfunction and β-adrenergic desensitization, which with additional endothelin-1-driven hypertrophic stimulation, generates an advanced model of heart failure (Tiburcy et al., 2017). Notably, endothelin -1 treatment does not produce additional hypertrophic growth in hPSC-CM at such late stages of maturation, but induces more clinically relevant hypertrophic features, such as contractile dysfunction (Ronaldson-Bouchard et al., 2018). Additionally, porcine scaffold-based hEHTs have been employed recently to highlight the vicious cycle of maladaptive hypertrophy, with healthy hPSC-CMs responding to hypertrophic ECMs with impaired function, which in vivo would feed-back to the cardiac microenvironment triggering additional maladaptation preventing recovery under pharmacological treatment (Sewanan et al., 2019).

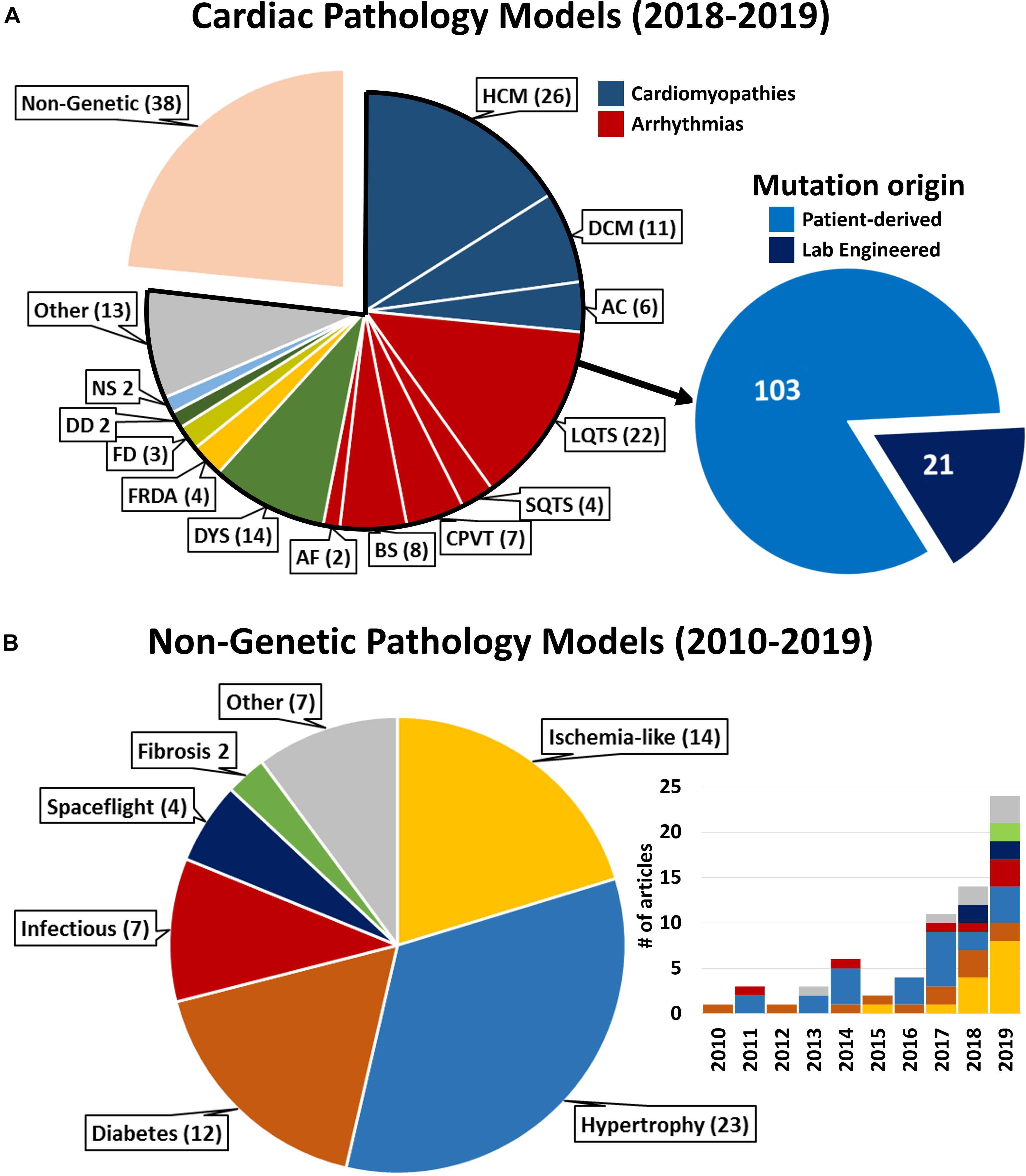

Animal-derived models often incorrectly represent human cardiac features and diverge in stress-responses (Olson et al., 2000; Davis et al., 2011). hPSC-CMs offer an invaluable tool to study the human heart in vitro, provided that stress-responsive phenotypes are apparent and representative of in vivo conditions. The necessity of hPSC-CM priming for pathology modeling is apparent in some hereditary monogenic pathologies (Kim et al., 2013), but becomes essential for most non-genetic diseases described here, given their incidence later in adult life. Optimization of cardiac maturation and metabolic priming protocols generated better insight into the crosstalk between structural, functional and metabolic states of hPSC-CMs. These advances now allow more representative modeling of non-genetic diseases, still lagging behind the highly penetrant genetic conditions with clear analytical read-outs that dominate hPSC-CM literature (Figure 2A).

Figure 2. Literature statistics on cardiac pathology models and cited references. (A) Complete representation of pathological models for cardiac diseases available on PubMed between January 1st 2018 and January 2nd 2020. HCM, Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy; DCM, Dilated Cardiomyopathy; AC, Arrhythmogenic Cardiomyopathy; L/SQTS, Long/Short QT Syndrome; CPVT, Catecholaminergic Polymorphic Ventricular Tachycardia; BS, Brugada Syndrome; AF, Atrial Fibrillation; DYS, Muscular Dystrophies [Duchenne (9), Myotonic (4), Limb-Girdle (1)]; FRDA, Friedriech’s Ataxia; FD, Fabry Disease; DD, Danon Disease; NS, Noonan Syndrome; Other, different genetic diseases represented by (1) article. Inset: all cardiac genetic pathology models reported in 2018–2019 relative to cell model derivation. “Lab engineered”: healthy hPSC genetically edited to carry the mutation under consideration. (B) Representation of non-genetic conditions referenced in this review according to the pathological condition modeled. Inset: distribution per year of publication of the referenced articles (same color coding). For bibliographical research methods and full list of references reported in this figure, see Supplementary Material.

Currently, advanced modeling of the adult myocardium requires hEHTs. These multiparametric setups integrating stimulation and data acquisition systems, act as human preclinical models refining the predictive efficacy of less throughput-limited 2D hPSC-CM models (Fiedler et al., 2019). Nevertheless, while closely resembling adult tissue transcriptomic and functional features, hEHTs fall short of gaining the status of full-fledged organoids, not fully mimicking adult myocardial macroscopic ultrastructure (Tiburcy et al., 2017; Ronaldson-Bouchard et al., 2018), thus requiring additional bioengineering efforts to scale up the systems from tissue- to organ-models, as the recently proposed atrioventricular composite (Zhao et al., 2019).

Importantly, the widespread use of commercially available cell products in the studies reported here (Supplementary Table S1) highlights the necessity of increasing robustness and reproducibility of the results through differentiation and culture protocols standardization. Indeed, whenever patient-specificity is not essential, employment of standardized experimental platforms is desirable to study a plethora of environmental cardiac insults (Turnbull et al., 2018; Figure 2B), remaining mindful of the pitfalls of broadening the results of few cell lines to the general population and of the aspirations toward personalized medicine approaches.

Finally, combining hPSC-CM-based models with high precision genome-editing technologies will be instrumental in not only supporting modeling of hereditary diseases by screening artificially introduced genetic variants of unknown significance (VUSs) (Figure 2A), but also in dissecting complex dynamics between non-genetic pathological stimuli and genetic backgrounds characterized by polygenic interactions.

All authors reviewed the literature, wrote, edited, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

This work was supported by ShanghaiTech University (SM, NE, Grant F-0301-15-009); Oak Foundation Award (NE, Grant W1095/OCAY-14-191); British Heart Foundation (MM, Grant FS/17/70/33482).

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphys.2020.00384/full#supplementary-material

Acharya, A., Brungs, S., Lichterfeld, Y., Hescheler, J., Hemmersbach, R., Boeuf, H., et al. (2019). Parabolic, flight-induced, acute hypergravity and microgravity effects on the beating rate of human cardiomyocytes. Cells 8:352. doi: 10.3390/cells8040352

Acun, A., Nguyen, T. D., and Zorlutuna, P. (2019). In vitro aged, hiPSC-origin engineered heart tissue models with age-dependent functional deterioration to study myocardial infarction. Acta Biomater. 94, 372–391. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2019.05.064

Aggarwal, P., Turner, A., Matter, A., Kattman, S. J., Stoddard, A., Lorier, R., et al. (2014). RNA expression profiling of human iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes in a cardiac hypertrophy model. PLoS One 9:e108051. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108051

Becker, B. V., Majewski, M., Abend, M., Palnek, A., Nestler, K., Port, M., et al. (2018a). Gene expression changes in human iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes after X-ray irradiation. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 94, 1095–1103. doi: 10.1080/09553002.2018.1516908

Becker, B. V., Seeger, T., Beiert, T., Antwerpen, M., Palnek, A., Port, M., et al. (2018b). Impact of Ionizing radiation on electrophysiological behavior of human-induced ipsc-derived cardiomyocytes on multielectrode arrays. Health Phys. 115, 21–28. doi: 10.1097/hp.0000000000000817

Blinova, K., Dang, Q., Millard, D., Smith, G., Pierson, J., Guo, L., et al. (2018). International multisite study of human-induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes for drug proarrhythmic potential assessment. Cell Rep. 24, 3582–3592. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.08.079

Blinova, K., Schocken, D., Patel, D., Daluwatte, C., Vicente, J., Wu, J. C., et al. (2019). Clinical trial in a dish: personalized stem cell-derived cardiomyocyte assay compared with clinical trial results for two qt-prolonging drugs. Clin. Transl. Sci. 12, 687–697. doi: 10.1111/cts.12674

Bozzi, A., Sayed, N., Matsa, E., Sass, G., Neofytou, E., Clemons, K. V., et al. (2019). Using human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes as a model to study trypanosoma cruzi infection. Stem Cell Rep. 12, 1232–1241. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2019.04.017

Burridge, P. W., Matsa, E., Shukla, P., Lin, Z. C., Churko, J. M., Ebert, A. D., et al. (2014). Chemically defined generation of human cardiomyocytes. Nat. Methods 11, 855–860. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2999

Canfield, S. G., Sepac, A., Sedlic, F., Muravyeva, M. Y., Bai, X., and Bosnjak, Z. J. (2012). Marked hyperglycemia attenuates anesthetic preconditioning in human-induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. Anesthesiology 117, 735–744. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3182655e96

Canfield, S. G., Zaja, I., Godshaw, B., Twaroski, D., Bai, X., and Bosnjak, Z. J. (2016). High glucose attenuates anesthetic cardioprotection in stem-cell-derived cardiomyocytes: the role of reactive oxygen species and mitochondrial fission. Anesth Analg. 122, 1269–1279. doi: 10.1213/ane.0000000000001254

Carlson, C., Koonce, C., Aoyama, N., Einhorn, S., Fiene, S., Thompson, A., et al. (2013). Phenotypic screening with human iPS cell-derived cardiomyocytes: HTS-compatible assays for interrogating cardiac hypertrophy. J. Biomol. Screen 18, 1203–1211. doi: 10.1177/1087057113500812

Carvajal-Vergara, X., Sevilla, A., D’Souza, S. L., Ang, Y. S., Schaniel, C., Lee, D. F., et al. (2010). Patient-specific induced pluripotent stem-cell-derived models of LEOPARD syndrome. Nature 465, 808–812. doi: 10.1038/nature09005

Chanda, D., Oligschlaeger, Y., Geraets, I., Liu, Y., Zhu, X., Li, J., et al. (2017). 2-Arachidonoylglycerol ameliorates inflammatory stress-induced insulin resistance in cardiomyocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 292, 7105–7114. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.767384

Chen, T., and Vunjak-Novakovic, G. (2019). Human tissue-engineered model of myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Tissue Eng. Part A 25, 711–724. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEA.2018.0212

Cho, G.-S., Lee, D. I., Tampakakis, E., Murphy, S., Andersen, P., Uosaki, H., et al. (2017). Neonatal transplantation confers maturation of PSC-Derived cardiomyocytes conducive to modeling cardiomyopathy. Cell Rep. 18, 571–582. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.12.040

Cui, H., Schlesinger, J., Schoenhals, S., Tonjes, M., Dunkel, I., Meierhofer, D., et al. (2016). Phosphorylation of the chromatin remodeling factor DPF3a induces cardiac hypertrophy through releasing HEY repressors from DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, 2538–2553. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1244

da Silva Lara, L., Andrade-Lima, L., Magalhaes Calvet, C., and Borsoi, J. Lopes Alberto, et al. (2018). Trypanosoma cruzi infection of human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes: an in vitro model for drug screening for Chagas disease. Microbes Infect. 20, 312–316. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2018.03.002

Davis, R. P., van den Berg, C. W., Casini, S., Braam, S. R., and Mummery, C. L. (2011). Pluripotent stem cell models of cardiac disease and their implication for drug discovery and development. Trends Mol. Med. 17, 475–484. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2011.05.001

Drawnel, F. M., Boccardo, S., Prummer, M., Delobel, F., Graff, A., Weber, M., et al. (2014). Disease modeling and phenotypic drug screening for diabetic cardiomyopathy using human induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Rep. 9, 810–821. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.09.055

Fernandez-Morales, J. C., Hua, W., Yao, Y., and Morad, M. (2019). Regulation of Ca(2+) signaling by acute hypoxia and acidosis in cardiomyocytes derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Calcium 78, 1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2018.12.006

Fiedler, L. R., Chapman, K., Xie, M., Maifoshie, E., Jenkins, M., Golforoush, P. A., et al. (2019). MAP4K4 inhibition promotes survival of human stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes and reduces infarct size In Vivo. Cell Stem Cell 24, 579.e12–591.e12. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2019.01.013

Foldes, G., Matsa, E., Kriston-Vizi, J., Leja, T., Amisten, S., Kolker, L., et al. (2014). Aberrant alpha-adrenergic hypertrophic response in cardiomyocytes from human induced pluripotent cells. Stem Cell Rep. 3, 905–914. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2014.09.002

Foldes, G., Mioulane, M., Wright, J. S., Liu, A. Q., Novak, P., Merkely, B., et al. (2011). Modulation of human embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocyte growth: a testbed for studying human cardiac hypertrophy? J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 50, 367–376. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.10.029

Gaber, N., Gagliardi, M., Patel, P., Kinnear, C., Zhang, C., Chitayat, D., et al. (2013). Fetal reprogramming and senescence in hypoplastic left heart syndrome and in human pluripotent stem cells during cardiac differentiation. Am. J. Pathol. 183, 720–734. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.05.022

Gao, G., Xie, A., Huang, S.-C., Zhou, A., Zhang, J., Herman, A. M., et al. (2011). Role of RBM25/LUC7L3 in abnormal cardiac sodium channel splicing regulation in human heart failure. Circulation 124, 1124–1131. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.044495

Gao, G., Xie, A., Zhang, J., Herman, A. M., Jeong, E. M., Gu, L., et al. (2013). Unfolded protein response regulates cardiac sodium current in systolic human heart failure. Circ. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol. 6, 1018–1024. doi: 10.1161/circep.113.000274

Gesmundo, I., Miragoli, M., Carullo, P., Trovato, L., Larcher, V., Di Pasquale, E., et al. (2017). Growth hormone-releasing hormone attenuates cardiac hypertrophy and improves heart function in pressure overload-induced heart failure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, 12033–12038. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1712612114

Goldfracht, I., Efraim, Y., Shinnawi, R., Kovalev, E., Huber, I., Gepstein, A., et al. (2019). Engineered heart tissue models from hiPSC-derived cardiomyocytes and cardiac ECM for disease modeling and drug testing applications. Acta Biomater. 92, 145–159. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2019.05.016

Graneli, C., Hicks, R., Brolen, G., Synnergren, J., and Sartipy, P. (2019). Diabetic cardiomyopathy modelling using induced pluripotent stem cell derived cardiomyocytes: recent advances and emerging models. Stem Cell Rev Rep. 15, 13–22. doi: 10.1007/s12015-018-9858-1

Haghighi, K., Kolokathis, F., Pater, L., Lynch, R. A., Asahi, M., Gramolini, A. O., et al. (2003). Human phospholamban null results in lethal dilated cardiomyopathy revealing a critical difference between mouse and human. J. Clin. Investig. 111, 869–876. doi: 10.1172/JCI17892

Hidalgo, A., Glass, N., Ovchinnikov, D., Yang, S. K., Zhang, X., Mazzone, S., et al. (2018). Modelling ischemia-reperfusion injury (IRI) in vitro using metabolically matured induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. APL Bioeng 2:026102. doi: 10.1063/1.5000746

Hoes, M. F., Tromp, J., Ouwerkerk, W., Bomer, N., Oberdorf-Maass, S. U., Samani, N. J., et al. (2019). The role of cathepsin D in the pathophysiology of heart failure and its potentially beneficial properties: a translational approach. Eur. J. Heart Fail doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1674

Hrstka, S. C., Li, X., and Nelson, T. J. (2017). NOTCH1-dependent nitric oxide signaling deficiency in hypoplastic left heart syndrome revealed through patient-specific phenotypes detected in bioengineered cardiogenesis. Stem Cells 35, 1106–1119. doi: 10.1002/stem.2582

Hsieh, A., Feric, N. T., and Radisic, M. (2015). Combined hypoxia and sodium nitrite pretreatment for cardiomyocyte protection in vitro. Biotechnol. Prog. 31, 482–492. doi: 10.1002/btpr.2039

Idris-Khodja, N., Ouerd, S., Mian, M. O. R., Gornitsky, J., Barhoumi, T., Paradis, P., et al. (2016). Endothelin-1 overexpression exaggerates diabetes-induced endothelial dysfunction by altering oxidative stress. Am. J. Hypertens 29, 1245–1251. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpw078

Jiang, Y., Habibollah, S., Tilgner, K., Collin, J., Barta, T., Al-Aama, J. Y., et al. (2014). An induced pluripotent stem cell model of hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS) reveals multiple expression and functional differences in HLHS-derived cardiac myocytes. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 3, 416–423. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2013-0105

Joseph, J. J., and Golden, S. H. (2017). Cortisol dysregulation: the bidirectional link between stress, depression, and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1391, 20–34. doi: 10.1111/nyas.13217

Jung, G., Fajardo, G., Ribeiro, A. J., Kooiker, K. B., Coronado, M., Zhao, M., et al. (2016). Time-dependent evolution of functional vs. remodeling signaling in induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes and induced maturation with biomechanical stimulation. Faseb J. 30, 1464–1479. doi: 10.1096/fj.15-280982

Kadota, S., Pabon, L., Reinecke, H., and Murry, C. E. (2017). In Vivo maturation of human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes in neonatal and adult rat hearts. Stem Cell Rep. 8, 278–289. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2016.10.009

Kamakura, T., Makiyama, T., Sasaki, K., Yoshida, Y., Wuriyanghai, Y., Chen, J., et al. (2013). Ultrastructural maturation of human-induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes in a long-term culture. Circ. J. 77, 1307–1314. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-12-0987

Kattman, S. J., Witty, A. D., Gagliardi, M., Dubois, N. C., Niapour, M., Hotta, A., et al. (2011). Stage-specific optimization of activin/nodal and BMP signaling promotes cardiac differentiation of mouse and human pluripotent stem cell lines. Cell Stem Cell 8, 228–240. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.12.008

Kehat, I., Kenyagin-Karsenti, D., Snir, M., Segev, H., Amit, M., Gepstein, A., et al. (2001). Human embryonic stem cells can differentiate into myocytes with structural and functional properties of cardiomyocytes. J. Clin. Invest 108, 407–414. doi: 10.1172/jci12131

Kim, C., Wong, J., Wen, J., Wang, S., Wang, C., Spiering, S., et al. (2013). Studying arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia with patient-specific iPSCs. Nature 494, 105–110. doi: 10.1038/nature11799

Kirby, R. J., Divlianska, D. B., Whig, K., Bryan, N., Morfa, C. J., Koo, A., et al. (2018). Discovery of novel small-molecule inducers of heme oxygenase-1 that protect human ipsc-derived cardiomyocytes from oxidative stress. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 364, 87–96. doi: 10.1124/jpet.117.243717

Kobayashi, J., Yoshida, M., Tarui, S., Hirata, M., Nagai, Y., Kasahara, S., et al. (2014). Directed differentiation of patient-specific induced pluripotent stem cells identifies the transcriptional repression and epigenetic modification of NKX2-5. HAND1, and NOTCH1 in hypoplastic left heart syndrome. PLoS One 9:e102796. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0102796

Kumar, A., Thomas, S. K., Wong, K. C., Lo Sardo, V., Cheah, D. S., Hou, Y. H., et al. (2019). Mechanical activation of noncoding-RNA-mediated regulation of disease-associated phenotypes in human cardiomyocytes. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 3, 137–146. doi: 10.1038/s41551-018-0344-5

LaBarge, W., Mattappally, S., Kannappan, R., Fast, V. G., Pretorius, D., Berry, J. L., et al. (2019). Maturation of three-dimensional, hiPSC-derived cardiomyocyte spheroids utilizing cyclic, uniaxial stretch and electrical stimulation. PLoS One 14:e0219442. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0219442

Laflamme, M. A., Chen, K. Y., Naumova, A. V., Muskheli, V., Fugate, J. A., Dupras, S. K., et al. (2007). Cardiomyocytes derived from human embryonic stem cells in pro-survival factors enhance function of infarcted rat hearts. Nat. Biotechnol. 25, 1015–1024. doi: 10.1038/nbt1327

Lemme, M., Braren, I., Prondzynski, M., Aksehirlioglu, B., Ulmer, B. M., Schulze, M. L., et al. (2019). Chronic intermittent tachypacing by an optogenetic approach induces arrhythmia vulnerability in human engineered heart tissue. Cardiovasc. Res. cvz245. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvz245

Leonard, A., Bertero, A., Powers, J. D., Beussman, K. M., Bhandari, S., Regnier, M., et al. (2018). Afterload promotes maturation of human induced pluripotent stem cell derived cardiomyocytes in engineered heart tissues. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 118, 147–158. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2018.03.016

Li, Z., Mirams, G. R., Yoshinaga, T., Ridder, B. J., Han, X., Chen, J. E., et al. (2020). General principles for the validation of proarrhythmia risk prediction models: an extension of the CiPA in silico strategy. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 107, 102–111. doi: 10.1002/cpt.1647

Lian, X., Hsiao, C., Wilson, G., Zhu, K., Hazeltine, L. B., Azarin, S. M., et al. (2012). Robust cardiomyocyte differentiation from human pluripotent stem cells via temporal modulation of canonical Wnt signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, E1848–E1857. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200250109

Liu, Y., Steinbusch, L. K. M., Nabben, M., Kapsokalyvas, D., van Zandvoort, M., Schönleitner, P., et al. (2017). Palmitate-induced vacuolar-type H+-ATPase inhibition feeds forward into insulin resistance and contractile dysfunction. Diabetes 66, 1521–1534. doi: 10.2337/db16-0727

Lowry, W. E., Richter, L., Yachechko, R., Pyle, A. D., Tchieu, J., Sridharan, R., et al. (2008). Generation of human induced pluripotent stem cells from dermal fibroblasts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 105, 2883–2888. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711983105

Lu, H. R., Zeng, H., Kettenhofen, R., Guo, L., Kopljar, I., van Ammel, K., et al. (2019). Assessing drug-induced long QT and proarrhythmic risk using human stem-cell-derived cardiomyocytes in a Ca2+ imaging assay: evaluation of 28 CiPA compounds at three test sites. Toxicol. Sci. 170, 345–356. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfz102

Lu, Y., Bu, M., and Yun, H. (2019). Sevoflurane prevents hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis by inhibiting PI3KC3-mediated autophagy. Hum. Cell 32, 150–159. doi: 10.1007/s13577-018-00230-4

Lundy, S. D., Zhu, W.-Z., Regnier, M., and Laflamme, M. A. (2013). Structural and functional maturation of cardiomyocytes derived from human pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells Dev. 22, 1991–2002. doi: 10.1089/scd.2012.0490

Machiraju, P., and Greenway, S. C. (2019). Current methods for the maturation of induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. World J. Stem Cells 11, 33–43. doi: 10.4252/wjsc.v11.i1.33

Magdy, T., Schuldt, A. J. T., Wu, J. C., Bernstein, D., and Burridge, P. W. (2018). Human induced pluripotent stem cell (hiPSC)-derived cells to assess drug cardiotoxicity: opportunities and problems. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 58, 83–103. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010617-053110

Martewicz, S., Gabrel, G., Campesan, M., Canton, M., Di Lisa, F., and Elvassore, N. (2018). Live cell imaging in microfluidic device proves resistance to oxygen/glucose deprivation in human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. Anal. Chem. 90, 5687–5695. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.7b05347

Martewicz, S., Luni, C., Serena, E., Pavan, P., Chen, H. V., Rampazzo, A., et al. (2019). Transcriptomic characterization of a human in vitro model of arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy under topological and mechanical stimuli. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 47, 852–865. doi: 10.1007/s10439-018-02134-8

Martewicz, S., Michielin, F., Serena, E., Zambon, A., Mongillo, M., and Elvassore, N. (2012). Reversible alteration of calcium dynamics in cardiomyocytes during acute hypoxia transient in a microfluidic platform. Integr. Biol. 4, 153–164. doi: 10.1039/c1ib00087j

Martewicz, S., Serena, E., Zatti, S., Keller, G., and Elvassore, N. (2017). Substrate and mechanotransduction influence SERCA2a localization in human pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes affecting functional performance. Stem Cell Res. 25, 107–114. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2017.10.011

Martin, T. P., Hortigon-Vinagre, M. P., Findlay, J. E., Elliott, C., Currie, S., and Baillie, G. S. (2014). Targeted disruption of the heat shock protein 20-phosphodiesterase 4D (PDE4D) interaction protects against pathological cardiac remodelling in a mouse model of hypertrophy. FEBS Open Bio 4, 923–927. doi: 10.1016/j.fob.2014.10.011

Mathieu, S., El Khoury, N., Rivard, K., Gelinas, R., Goyette, P., Paradis, P., et al. (2016). Reduction in Na(+) current by angiotensin II is mediated by PKCalpha in mouse and human-induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. Heart Rhythm 13, 1346–1354. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2016.02.015

McMullen, J. R., and Jennings, G. L. (2007). Differences between pathological and physiological cardiac hypertrophy: novel therapeutic strategies to treat heart failure. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 34, 255–262. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2007.04585.x

Mirtschink, P., Bischof, C., Pham, M. D., Sharma, R., Khadayate, S., Rossi, G., et al. (2019). Inhibition of the hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha-induced cardiospecific herna1 enhance-templated RNA protects from heart disease. Circulation 139, 2778–2792. doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.118.036769

Mo, B., Wu, X., Wang, X., Xie, J., Ye, Z., and Li, L. (2019). miR-30e-5p mitigates hypoxia-induced apoptosis in human stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes by suppressing bim. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 15, 1042–1051. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.31099

Moretti, A., Bellin, M., Welling, A., Jung, C. B., Lam, J. T., Bott-Flugel, L., et al. (2010). Patient-specific induced pluripotent stem-cell models for long-QT syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 363, 1397–1409. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908679

Mummery, C., Ward-van Oostwaard, D., Doevendans, P., Spijker, R., van den Brink, S., Hassink, R., et al. (2003). Differentiation of human embryonic stem cells to cardiomyocytes: role of coculture with visceral endoderm-like cells. Circulation 107, 2733–2740. doi: 10.1161/01.Cir.0000068356.38592.68

Naftali-Shani, N., Molotski, N., Nevo-Caspi, Y., Arad, M., Kuperstein, R., Amit, U., et al. (2018). Modeling peripartum cardiomyopathy with human induced pluripotent stem cells reveals distinctive abnormal function of cardiomyocytes. Circulation 138, 2721–2723. doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.118.035950

Nagai, H., Satomi, T., Abiru, A., Miyamoto, K., Nagasawa, K., Maruyama, M., et al. (2017). Antihypertrophic effects of small molecules that maintain mitochondrial ATP levels under hypoxia. EBioMed. 24, 147–158. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2017.09.022

Nerbonne, J. M., Nichols, C. G., Schwarz, T. L., and Escande, D. (2001). Genetic manipulation of cardiac K(+) channel function in mice: what have we learned, and where do we go from here? Circ. Res. 89, 944–956. doi: 10.1161/hh2301.100349

Ng, K. M., Lau, Y. M., Dhandhania, V., Cai, Z. J., Lee, Y. K., Lai, W. H., et al. (2018). Empagliflozin ammeliorates high glucose induced-cardiac dysfuntion in human iPSC-Derived cardiomyocytes. Sci. Rep. 8:14872. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-33293-2

Olson, H., Betton, G., Robinson, D., Thomas, K., Monro, A., Kolaja, G., et al. (2000). Concordance of the toxicity of pharmaceuticals in humans and in animals. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 32, 56–67. doi: 10.1006/rtph.2000.1399

Otsuji, T. G., Minami, I., Kurose, Y., Yamauchi, K., Tada, M., and Nakatsuji, N. (2010). Progressive maturation in contracting cardiomyocytes derived from human embryonic stem cells: qualitative effects on electrophysiological responses to drugs. Stem Cell Res. 4, 201–213. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2010.01.002

Pallotta, I., Sun, B., Wrona, E. A., and Freytes, D. O. (2015). BMP protein-mediated crosstalk between inflammatory cells and human pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 11, 1466–1478. doi: 10.1002/term.2045

Pant, T., Mishra, M. K., Bai, X., Ge, Z. D., Bosnjak, Z. J., and Dhanasekaran, A. (2019). Microarray analysis of long non-coding RNA and mRNA expression profiles in diabetic cardiomyopathy using human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. Diab. Vasc. Dis. Res. 16, 57–68. doi: 10.1177/1479164118813888

Park, I.-H., Zhao, R., West, J. A., Yabuuchi, A., Huo, H., Ince, T. A., et al. (2008). Reprogramming of human somatic cells to pluripotency with defined factors. Nature 451, 141–146. doi: 10.1038/nature06534

Park, J., Anderson, C. W., Sewanan, L. R., Kural, M. H., Huang, Y., Luo, J., et al. (2019). Modular design of a tissue engineered pulsatile conduit using human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. Acta Biomater 102, 220–230. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2019.10.019

Qin, P., Arabacilar, P., Bernard, R. E., Bao, W., Olzinski, A. R., Guo, Y., et al. (2017). Activation of the amino acid response pathway blunts the effects of cardiac stress. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 6:e004453. doi: 10.1161/jaha.116.004453

Rampoldi, A., Singh, M., Wu, Q., Duan, M., Jha, R., Maxwell, J. T., et al. (2019). Cardiac toxicity from ethanol exposure in human-induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. Toxicol. Sci. 169, 280–292. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfz038

Ronaldson-Bouchard, K., Ma, S. P., Yeager, K., Chen, T., Song, L., Sirabella, D., et al. (2018). Advanced maturation of human cardiac tissue grown from pluripotent stem cells. Nature 556, 239–243. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0016-3

Rosales, W., and Lizcano, F. (2018). The histone demethylase JMJD2A modulates the induction of hypertrophy markers in ipsc-derived cardiomyocytes. Front. Genet. 9:14. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2018.00014

Ross, S. B., Fraser, S. T., and Semsarian, C. (2018). Induced pluripotent stem cell technology and inherited arrhythmia syndromes. Heart Rhythm 15, 137–144. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2017.08.013

Rupert, C. E., Chang, H. H., and Coulombe, K. L. (2017). Hypertrophy changes 3D shape of hiPSC-cardiomyocytes: implications for cellular maturation in regenerative medicine. Cell Mol. Bioeng 10, 54–62. doi: 10.1007/s12195-016-0462-7

Sakai, K., Shimba, K., Ishizuka, K., Yang, Z., Oiwa, K., Takeuchi, A., et al. (2017). Functional innervation of human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes by co-culture with sympathetic neurons developed using a microtunnel technique. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 494, 138–143. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.10.065

Sandstedt, M., Rotter Sopasakis, V., Lundqvist, A., Vukusic, K., Oldfors, A., Dellgren, G., et al. (2018). Hypoxic cardiac fibroblasts from failing human hearts decrease cardiomyocyte beating frequency in an ALOX15 dependent manner. PLoS One 13:e0202693. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0202693

Sartiani, L., Bettiol, E., Stillitano, F., Mugelli, A., Cerbai, E., and Jaconi, M. E. (2007). Developmental changes in cardiomyocytes differentiated from human embryonic stem cells: a molecular and electrophysiological approach. Stem Cells 25, 1136–1144. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0466

Sass, G., Madigan, R. T., Joubert, L. M., Bozzi, A., Sayed, N., Wu, J. C., et al. (2019a). A combination of itraconazole and amiodarone is highly effective against trypanosoma cruzi Infection of human stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 101, 383–391. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.19-0023

Sass, G., Tsamo, A. T., Chounda, G. A. M., Nangmo, P. K., Sayed, N., Bozzi, A., et al. (2019b). Vismione B interferes with trypanosoma cruzi infection of vero cells and human stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 101, 1359–1368. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.19-0350

Scassa, M. E., Jaquenod, de Giusti, C., Questa, M., Pretre, G., Richardson, G. A., et al. (2011). Human embryonic stem cells and derived contractile embryoid bodies are susceptible to Coxsakievirus B infection and respond to interferon Ibeta treatment. Stem Cell Res. 6, 13–22. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2010.09.002

Scrimgeour, N. R., Wrobel, A., Pinho, M. J., and Hoydal, M. A. (2019). microRNA-451a prevents activation of matrix metalloproteinases 2/9 in human cardiomyocytes during pathological stress stimulation. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 318, C94–C102. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00204.2019

Sebastiao, M. J., Gomes-Alves, P., Reis, I., Sanchez, B., Palacios, I., Serra, M., et al. (2020). Bioreactor-based 3D human myocardial ischemia/reperfusion in vitro model: a novel tool to unveil key paracrine factors upon acute myocardial infarction. Transl. Res. 215, 57–74. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2019.09.001

Sebastiao, M. J., Serra, M., Pereira, R., Palacios, I., Gomes-Alves, P., and Alves, P. M. (2019). Human cardiac progenitor cell activation and regeneration mechanisms: exploring a novel myocardial ischemia/reperfusion in vitro model. Stem Cell Res Ther. 10:77. doi: 10.1186/s13287-019-1174-4

Sepac, A., Sedlic, F., Si-Tayeb, K., Lough, J., Duncan, S. A., Bienengraeber, M., et al. (2010). Isoflurane preconditioning elicits competent endogenous mechanisms of protection from oxidative stress in cardiomyocytes derived from human embryonic stem cells. Anesthesiology 113, 906–916. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181eff6b7

Sewanan, L. R., Schwan, J., Kluger, J., Park, J., Jacoby, D. L., Qyang, Y., et al. (2019). Extracellular matrix from hypertrophic myocardium provokes impaired twitch dynamics in healthy cardiomyocytes. JACC Basic Transl. Sci. 4, 495–505. doi: 10.1016/j.jacbts.2019.03.004

Shanmughapriya, S., Tomar, D., Dong, Z., Slovik, K. J., Nemani, N., Natarajaseenivasan, K., et al. (2018). FOXD1-dependent MICU1 expression regulates mitochondrial activity and cell differentiation. Nat. Commun. 9:3449. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05856-4

Sharma, A., Marceau, C., Hamaguchi, R., Burridge, P. W., Rajarajan, K., Churko, J. M., et al. (2014). Human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes as an in vitro model for coxsackievirus B3-induced myocarditis and antiviral drug screening platform. Circ. Res. 115, 556–566. doi: 10.1161/circresaha.115.303810

Takahashi, K., Tanabe, K., Ohnuki, M., Narita, M., Ichisaka, T., Tomoda, K., et al. (2007). Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell 131, 861–872. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.019

Tanaka, A., Yuasa, S., Mearini, G., Egashira, T., Seki, T., Kodaira, M., et al. (2014). Endothelin-1 induces myofibrillar disarray and contractile vector variability in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy-induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 3:e001263. doi: 10.1161/jaha.114.001263

Tiburcy, M., Hudson, J. E., Balfanz, P., Schlick, S., Meyer, T., Chang Liao, M. L., et al. (2017). Defined engineered human myocardium with advanced maturation for applications in heart failure modeling and repair. Circulation 135, 1832–1847. doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.116.024145

Tomita-Mitchell, A., Stamm, K. D., Mahnke, D. K., Kim, M. S., Hidestrand, P. M., Liang, H. L., et al. (2016). Impact of MYH6 variants in hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Physiol. Genomics 48, 912–921. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00091.2016

Trieschmann, J., Haustein, M., Koster, A., Hescheler, J., Brockmeier, K., Bennink, G., et al. (2019). Different responses to drug safety screening targets between human neonatal and infantile heart tissue and cardiac bodies derived from human-induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells Int. 2019:6096294. doi: 10.1155/2019/6096294

Turnbull, I. C., Mayourian, J., Murphy, J. F., Stillitano, F., Ceholski, D. K., and Costa, K. D. (2018). Cardiac tissue engineering models of inherited and acquired cardiomyopathies. Methods Mol. Biol. 1816, 145–159. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-8597-5_11

Ulmer, B. M., Stoehr, A., Schulze, M. L., Patel, S., Gucek, M., Mannhardt, I., et al. (2018). Contractile work contributes to maturation of energy metabolism in hiPSC-derived cardiomyocytes. Stem Cell Rep. 10, 834–847. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2018.01.039

Uzun, A. U., Mannhardt, I., Breckwoldt, K., Horvath, A., Johannsen, S. S., Hansen, A., et al. (2016). Ca(2+)-currents in human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes effects of two different culture conditions. Front. Pharmacol. 7:300. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2016.00300

van den Berg, C. W., Okawa, S., Chuva, de Sousa Lopes, S. M., van Iperen, L., Passier, R., et al. (2015). Transcriptome of human foetal heart compared with cardiomyocytes from pluripotent stem cells. Development 142, 3231–3238. doi: 10.1242/dev.123810

van den Brink, L., Grandela, C., Mummery, C. L., and Davis, R. P. (2019). Inherited cardiac diseases, pluripotent stem cells and genome editing combined - the past, present and future. Stem Cells. 38, 174–186. doi: 10.1002/stem.3110

van Mil, A., Balk, G. M., Neef, K., Buikema, J. W., Asselbergs, F. W., Wu, S. M., et al. (2018). Modelling inherited cardiac disease using human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes: progress, pitfalls, and potential. Cardiovasc. Res. 114, 1828–1842. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvy208

Varzideh, F., Mahmoudi, E., and Pahlavan, S. (2019). Coculture with noncardiac cells promoted maturation of human stem cell-derived cardiomyocyte microtissues. J. Cell Biochem. 120, 16681–16691. doi: 10.1002/jcb.28926

Voges, H. K., Mills, R. J., Elliott, D. A., Parton, R. G., Porrello, E. R., and Hudson, J. E. (2017). Development of a human cardiac organoid injury model reveals innate regenerative potential. Development 144, 1118–1127. doi: 10.1242/dev.143966

Wang, Z., Zhang, X. J., Ji, Y. X., Zhang, P., Deng, K. Q., Gong, J., et al. (2016). The long noncoding RNA Chaer defines an epigenetic checkpoint in cardiac hypertrophy. Nat. Med. 22, 1131–1139. doi: 10.1038/nm.4179

Ward, M. C., and Gilad, Y. (2019). A generally conserved response to hypoxia in iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes from humans and chimpanzees. eLife 8:e42374. doi: 10.7554/eLife.42374

Wei, W., Liu, Y., Zhang, Q., Wang, Y., Zhang, X., and Zhang, H. (2017). Danshen-enhanced cardioprotective effect of cardioplegia on ischemia reperfusion injury in a human-induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes model. Artif. Organs 41, 452–460. doi: 10.1111/aor.12801

Wnorowski, A., Sharma, A., Chen, H., Wu, H., Shao, N. Y., Sayed, N., et al. (2019). Effects of spaceflight on human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocyte structure and function. Stem Cell Rep. 13, 960–969. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2019.10.006

Wu, D., Zhang, Q., Yu, Y., Zhang, Y., Zhang, M., Liu, Q., et al. (2018). Oleanolic acid, a novel endothelin a receptor antagonist, alleviated high glucose-induced cardiomyocytes injury. Am. J. Chin. Med. 46, 1187–1201. doi: 10.1142/s0192415x18500623

Yang, C., Xu, Y., Yu, M., Lee, D., Alharti, S., Hellen, N., et al. (2017). Induced pluripotent stem cell modelling of HLHS underlines the contribution of dysfunctional NOTCH signalling to impaired cardiogenesis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 26, 3031–3045. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddx140

Yang, L., Soonpaa, M. H., Adler, E. D., Roepke, T. K., Kattman, S. J., Kennedy, M., et al. (2008). Human cardiovascular progenitor cells develop from a KDR+ embryonic-stem-cell-derived population. Nature 453, 524–528. doi: 10.1038/nature06894

Yang, X., and Papoian, T. (2018). Moving beyond the comprehensive in vitro proarrhythmia assay: use of human-induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes to assess contractile effects associated with drug-induced structural cardiotoxicity. J. Appl. Toxicol. 38, 1166–1176. doi: 10.1002/jat.3611

Yu, J., Vodyanik, M. A., Smuga-Otto, K., Antosiewicz-Bourget, J., Frane, J. L., Tian, S., et al. (2007). Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells. Science 318, 1917–1920. doi: 10.1126/science.1151526

Yucel, G., Zhao, Z., El-Battrawy, I., Lan, H., Lang, S., Li, X., et al. (2017). Lipopolysaccharides induced inflammatory responses and electrophysiological dysfunctions in human-induced pluripotent stem cell derived cardiomyocytes. Sci. Rep. 7:2935. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-03147-4

Zhang, H., Tian, L., Shen, M., Tu, C., Wu, H., Gu, M., et al. (2019). Generation of quiescent cardiac fibroblasts from human induced pluripotent stem cells for in vitro modeling of cardiac fibrosis. Circ. Res. 125, 552–566. doi: 10.1161/circresaha.119.315491

Zhang, M. Y., Guo, F. F., Wu, H. W., Yu, Y. Y., Wei, J. Y., Wang, S. F., et al. (2017). DanHong injection targets endothelin receptor type B and angiotensin II receptor type 1 in protection against cardiac hypertrophy. Oncotarget 8:103393–103409. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.21900

Zhao, X., Chen, H., Xiao, D., Yang, H., Itzhaki, I., Qin, X., et al. (2018). Comparison of Non-human primate versus human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes for treatment of myocardial infarction. Stem Cell Rep. 10, 422–435. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2018.01.002

Keywords: ischemia – reperfusion, diabetes, non-genetic diseases, HPSC-cardiomyocytes, hPSC-CM, maladaptive hypertrophy

Citation: Martewicz S, Magnussen M and Elvassore N (2020) Beyond Family: Modeling Non-hereditary Heart Diseases With Human Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Cardiomyocytes. Front. Physiol. 11:384. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2020.00384

Received: 06 January 2020; Accepted: 30 March 2020;

Published: 22 April 2020.

Edited by:

Martina Calore, Maastricht University, NetherlandsReviewed by:

Elisa Di Pasquale, Italian National Research Council, ItalyCopyright © 2020 Martewicz, Magnussen and Elvassore. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sebastian Martewicz, c21hcnRld2ljekBzaGFuZ2hhaXRlY2guZWR1LmNu; Nicola Elvassore, bmljb2xhLmVsdmFzc29yZUB1bmlwZC5pdA==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.