- 1Key Laboratory of Crop Ecophysiology and Farming System in Southwest, Ministry of Agriculture, College of Agronomy, Sichuan Agricultural University, Chengdu, China

- 2Department of Agronomy, College of Agriculture, University of Sargodha, Sargodha, Pakistan

- 3Department of Plant Physiology, Slovak University of Agriculture, Nitra, Slovakia

- 4Department of Botany and Plant Physiology, Faculty of Agrobiology, Food and Natural Resources, Czech University of Life Science Prague, Prague, Czechia

- 5Institute of Ecological Agriculture, Sichuan Agricultural University, Chengdu, China

Water deficiency significantly affects photosynthetic characteristics. However, there is little information about variations in antioxidant enzyme activities and photosynthetic characteristics of soybean under imbalanced water deficit conditions (WDC). We therefore investigated the changes in photosynthetic and chlorophyll fluorescence characteristics, total soluble protein, Rubisco activity (RA), and enzymatic activities of two soybean varieties subjected to four different types of imbalanced WDC under a split-root system. The results indicated that the response of both cultivars was significant for all the measured parameters and the degree of response differed between cultivars under imbalanced WDC. The maximum values of enzymatic activities (SOD, CAT, GR, APX, and POD), chlorophyll fluorescence (Fv/Fm, qP, ɸPSII, and ETR), proline, RA, and total soluble protein were obtained with a drought-tolerant cultivar (ND-12). Among imbalanced WDC, the enhanced net photosynthesis, transpiration, and stomatal conductance rates in T2 allowed the production of higher total soluble protein after 5 days of stress, which compensated for the negative effects of imbalanced WDC. Treatment T4 exhibited greater potential for proline accumulation than treatment T1 at 0, 1, 3, and 5 days after treatment, thus showing the severity of the water stress conditions. In addition, the chlorophyll fluorescence values of FvFm, ɸPSII, qP, and ETR decreased as the imbalanced WDC increased, with lower values noted under treatment T4. Soybean plants grown in imbalanced WDC (T2, T3, and T4) exhibited signs of oxidative stress such as decreased chlorophyll content. Nevertheless, soybean plants developed their antioxidative defense-mechanisms, including the accelerated activities of these enzymes. Comparatively, the leaves of soybean plants in T2 displayed lower antioxidative enzymes activities than the leaves of T4 plants showing that soybean plants experienced less WDC in T2 compared to in T4. We therefore suggest that appropriate soybean cultivars and T2 treatments could mitigate abiotic stresses under imbalanced WDC, especially in intercropping.

Introduction

Soybean is an important crop throughout the world as a source of vegetable oil and protein. In southwest China, it is primarily intercropped with maize (Yan et al., 2010; Iqbal et al., 2018a). In maize-soybean planting, the height of the maize affects the microenvironment of the soybean in terms of light and moisture, having a negative effect on the soybean growth and development (Liu et al., 2017a). Earlier studies have shown imbalanced water deficit conditions for the soybean plants (Rahman et al., 2016). Interestingly, these imbalanced conditions significantly increased the production of biomass and yield and improved the quality of soybean (Iqbal et al., 2018b; Raza et al., 2018b). Reduced moisture leads to less photosynthesis, which reduces the dry matter production (Grassi and Magnani, 2005; Raza et al., 2018a). Therefore, the relative importance of physiological mechanisms should be recognized under imbalanced water deficit conditions.

Adequate water is needed for the development and growth of plants. The consequences of less than optimal water are oxidative stress and a reduction in photosynthetic characteristics (Guo et al., 2018). Reduction of photosynthesis results in decreased CO2 diffusion into the leaves because of lower internal (gi) and stomatal conductance (gs). It also results in the inhibition of photosynthesis due to limited leaf growth because of decreased cell proliferation (Lawlor and Tezara, 2009; Wu et al., 2018). More research is required to determine the activity and number of enzymes responsible for CO2 fixation and the regeneration of Rubisco-1,5-bisphosphate (RuBP). Rubisco (RuBP carboxylase or oxygenase) catalyzes the process of CO2 fixation (Susana et al., 2007) and is involved in the first phase of the Calvin Benson cycle. It accounts for 12–35% of leaf protein production in C3 plants (Evans and Seemann, 1989). Decreased RA may be involved in drought-associated photosynthetic rate (Flexas et al., 2006; Galmés et al., 2011). Imbalance in water deficit conditions may remarkably change the effect of Rubisco, but this has not been well elucidated yet.

Chlorophyll fluorescence measurements are an indicator of different drought responses of photosynthesis (Kalaji et al., 2018). Characteristics of chlorophyll fluorescence are a critical consideration as it is used to measure the quantum yield of photosystem II (PSII) and photoinactivation by determining the possible quantum yield under water limiting conditions (Batra et al., 2014). Photosynthesis is significantly affected by drought because it blocks the transport of energy from PSII to PSI (Siddique et al., 2016). It also leads to low chlorophyll fluorescence by reducing the palisade of spongy tissues and ultimate leaf thickness (Wang et al., 2018). In addition, the plant produces chemical signals in the dry portion of the root and this feed-forward mechanism reduces transpiration rate, stomatal opening, and shoot growth (Tardieu, 2016). These chemical signals are generally increased concentrations of abscisic acid (ABA) in the root that result in oxidative damage by unnecessary production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Beis and Patakas, 2015). ROS are regarded as second messengers in the ABA signaling pathway that regulate guard cell development (Yan et al., 2007). In the plasma membrane, the induction of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) by ABA is an essential signaling event in modulating stomatal closure to decrease water loss through the activation of calcium-permeable channels (Pei et al., 2000). The presence of the plant defense system can protect the plant metabolism because ROS magnifies water stress leading to cell death by changing the properties of the cell membrane and causes oxidative damage to chlorophyll, protein, lipids, and DNA (Ahmad et al., 2010). Therefore, plants activate their antioxidant defense system to reduce the effects of ROS (Fan et al., 2017). Major enzymes which scavenge the ROS are peroxidase (POD), superoxide dismutase (SOD), ascorbate peroxidase (APX), glutathione reductase (GR), and catalase (CAT). Although the physiological impacts produced by water deficit are well documented, this remains a subject of high priority under imbalanced water deficit conditions.

By analyzing photosynthesis, it is possible to determine the degree of resistance to adverse conditions of the environment, e.g., excessive congestion (Prasad et al., 2015; Olechowicz et al., 2018). Photosynthesis is progressively reduced during drought, but the reason for this reduction is unclear at the seedling stage of soybean. Many studies propose the importance of diffusional limitations (stomatal and mesophyll) for most water deficit situations. Recently, there have been many investigations about the photosynthetic characteristics and antioxidant potential of soybean and other plants in water-limited conditions (Zivcak et al., 2013; Guo et al., 2018; Prasad et al., 2018), but these studies have focused primarily on photosynthetic gas exchange, chlorophyll fluorescence and antioxidant activities. However, it is unclear how the imbalanced water deficit influences photosynthesis, chlorophyll fluorescence and antioxidant activities of soybean seedlings. Therefore, this study aims to analyze the variations in antioxidant enzyme activity and photosynthetic characteristics of soybean under imbalanced water deficit conditions. The objectives of the current study were to (1) determine the antioxidant enzyme activities and ROS in terms of malondialdehyde (MDA) and H2O2, and SOD, CAT, GR, POD and APX, and (2) evaluate the photosynthetic characteristics, fluorescence parameters, total soluble protein, proline and Rubisco-activated enzyme.

Materials and Methods

Plant Growth Exposure and Experimental Conditions

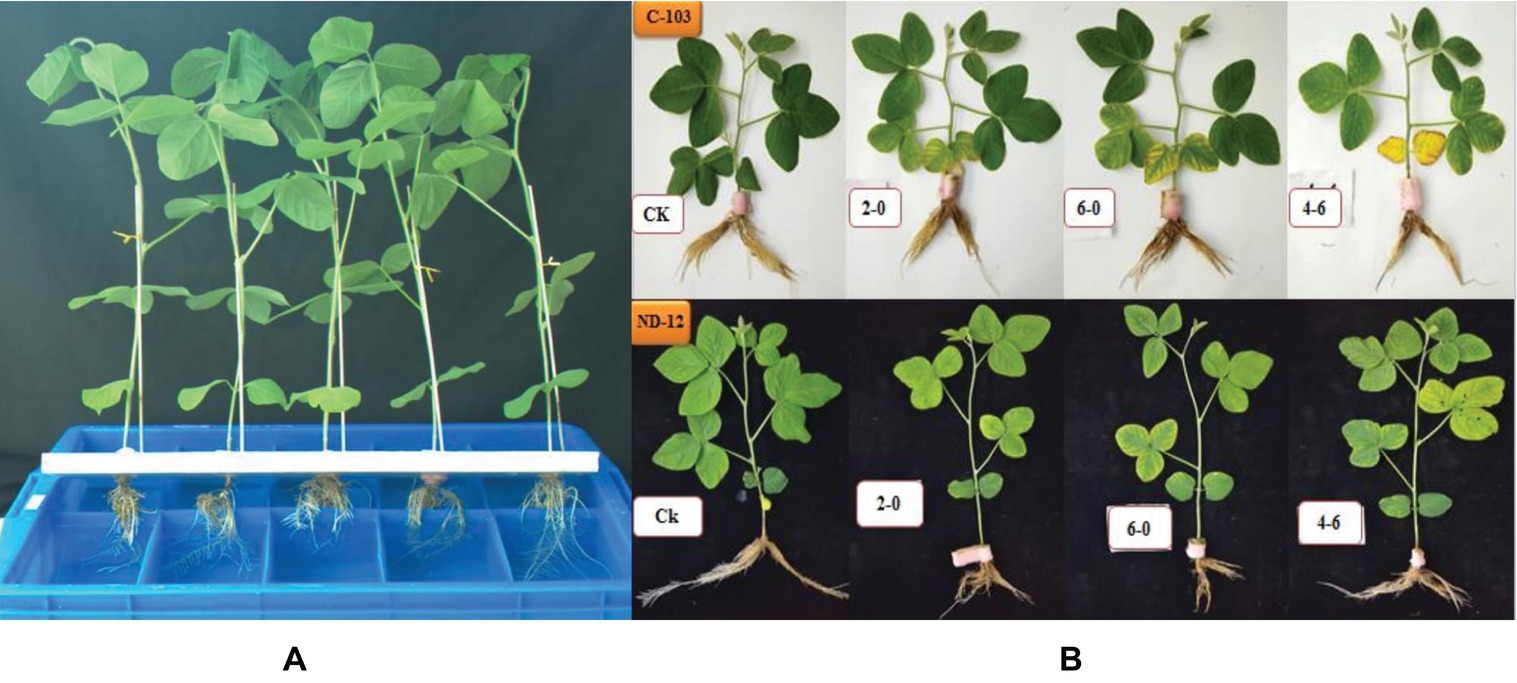

In this experiment, two soybean cultivars, ND-12 (drought-tolerant) and C-103 (drought-susceptible) were used in the greenhouse of Sichuan Agricultural University, Chengdu, China (29° 59′N, 103° 00′E). Seven-day-old seedlings (at the VC stage) were transplanted to plastic boxes containing half-strength Hoagland solution. Plant growth conditions were normal in the greenhouse, maintaining a 12 h photoperiod, 24/20°C day/night temperature and approximately 60–70% relative humidity. The photosynthetically active radiation was 279 μmol m−2 s−1. At the V3 stage, healthy plants were selected and their roots were equally divided in the solution boxes (Figure 1). Horizontal foam (polyurethane) was used to hold the soybean plants, which were kept under normal conditions for 1 week before exposure to stress treatments.

Figure 1. (A) Schematic representation of equally divided soybean roots in the solution box. (B) Phenotypic appearance of soybean cultivars after 5 days of PEG treatments; C-103 with a white background and ND-12 with a black background.

At the V4 stage, combinations of four different treatments were imposed: 0% polyethylene glycol (PEG) on both sides as control (T1 = 0%: 0%), 2% PEG on side A and 0% PEG on side B (T2 = 2%A: 0%B), 6% PEG on side A and 0% PEG on side B (T3 = 6%A: 0%B), and 4% PEG on side A and 6% PEG on side B (T4 = 4%A: 6%B). PEG-6000 was used to produce osmotic potential. Each treatment had three boxes each having five plants and had internal and external sizes of 530 mm × 350 mm × 130 mm and 590 mm × 380 mm × 140 mm, respectively. Leaf samples of each treatment were harvested in triplicate. Samples to be used for analysis were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored with their tags at −80°C.

Enzymatic Activities Measurement

All ROS and enzymatic activities were measured from one of the most recently expanded trifoliate leaves. Leaf samples were collected at 0, 1, 3, and 5 days and stored at −80°C for analysis. Commercial kits were used to determine the total soluble protein, superoxide dismutase (SOD), glutathione reductase (GR), peroxidase (POD), ascorbate peroxidase (APX), catalase (CAT), malondialdehyde (MDA), and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) as per the manufacturer’s instructions (Supplementary data). These commercial kits were ordered from Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China.

Proline Measurement

Free proline was measured according to a previously published method (Bates et al., 1973). Soybean leaves were collected at reproductive stage R5 and were freeze-dried and extracted with a 5 ml extraction solution of 3% sulfosalicylic acid. Then, 2 ml supernatant was reacted with glacial acid (2 ml) and acid ninhydrin (3 ml); the solution was boiled for 40 min. After cooling the samples at room temperature, 5 ml toluene was added and mixed by vortexing. The spectrophotometer (Mapada-V-1100D) read the absorbance at 520 nm.

Photosynthetic Characteristics and Chlorophyll Content

We used a portable photosynthesis system (Model LI-6400, LI-COR Inc., Lincoln, NE) to determine the net photosynthetic rate (PN), stomatal conductance (gs) and transpiration (E). Photosynthetic parameters were measured through the latest, fully expanded leaves between 08:00 to 11:00 h. The following settings of PARi = 1,000, flow = 500 μmol mol−1, stomatal ratio = 0.5, and reference CO2 concentration = 400 μmol mol−1 were used. Leaf chlorophyll contents were noted with the help of the SPAD-502 (Minolta, Japan) apparatus.

Chlorophyll Fluorescence Parameters

In this experiment, Fluor Technologia software (Fluor Images, United Kingdom) measured the chlorophyll fluorescence. We used plastic bags to preserve fully expanded leaf samples and placed them in an icebox covered with a lid to prevent the entry of direct light. Later, the samples were passed to a fluorescence analyzing device by using software. By placing them under dark and light conditions for 20 min., their photochemical efficiency (ɸPSII), photochemical quenching (qP) and electron transport rate (ETR) were determined by the FluorImager software, Technologia LTD (version 2.2.2.2) (Pan et al., 2017).

Analysis of Plant Rubisco-Activated Enzyme

The Rubisco ELISA kit (96 micropores) was purchased from Shanghai Fu Life Industry Co. Ltd., Shanghai, China. To measure the Rubisco-activated enzyme, 1 g of frozen leaf samples were ground with the help of a mortar and pestle and an icebox, using 2 ml of 50 mmol L−1 phosphate buffer solution (pH 7.8). The solution was centrifuged at 7000 rcf at 4°C for 15 min. The level of plant Rubisco activase was determined by the double antibody sandwich method. The micropore plate encapsulated the Rubisco activase antibody to form a solid phase antibody. This was added to the micropore of the monoclonal antibody. The 40 μl of phosphate buffer solution as a sample diluent was added first, followed by 10 ml of the sample solution in the micropore plate. A plastic film sealed the micropore plate and kept it incubated at 37°C for 30 min. This incubation was repeated five times. The 3,3′5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine was transferred under the catalysis of horseradish peroxidase enzyme, which first turned blue and finally to a yellow color under the action of an acid. The absorbance was measured after adding the stop solution within 15 min at a 450 nm wavelength by an enzyme marker. A standard curve was used to calculate the sample and the RA was expressed as U/g (Hussain et al., 2019).

Statistical Analysis

The experimental data analysis used Statistics software (Statistics 8.1. Tallahassee, FL, USA), while the figures were drawn using Microsoft Office 2010. Duncan’s multiple range tests compared the treatment means, with statistically significant differences at p ≤ 0.05.

Results

Effect of Imbalanced Water Deficit on Soybean ROS

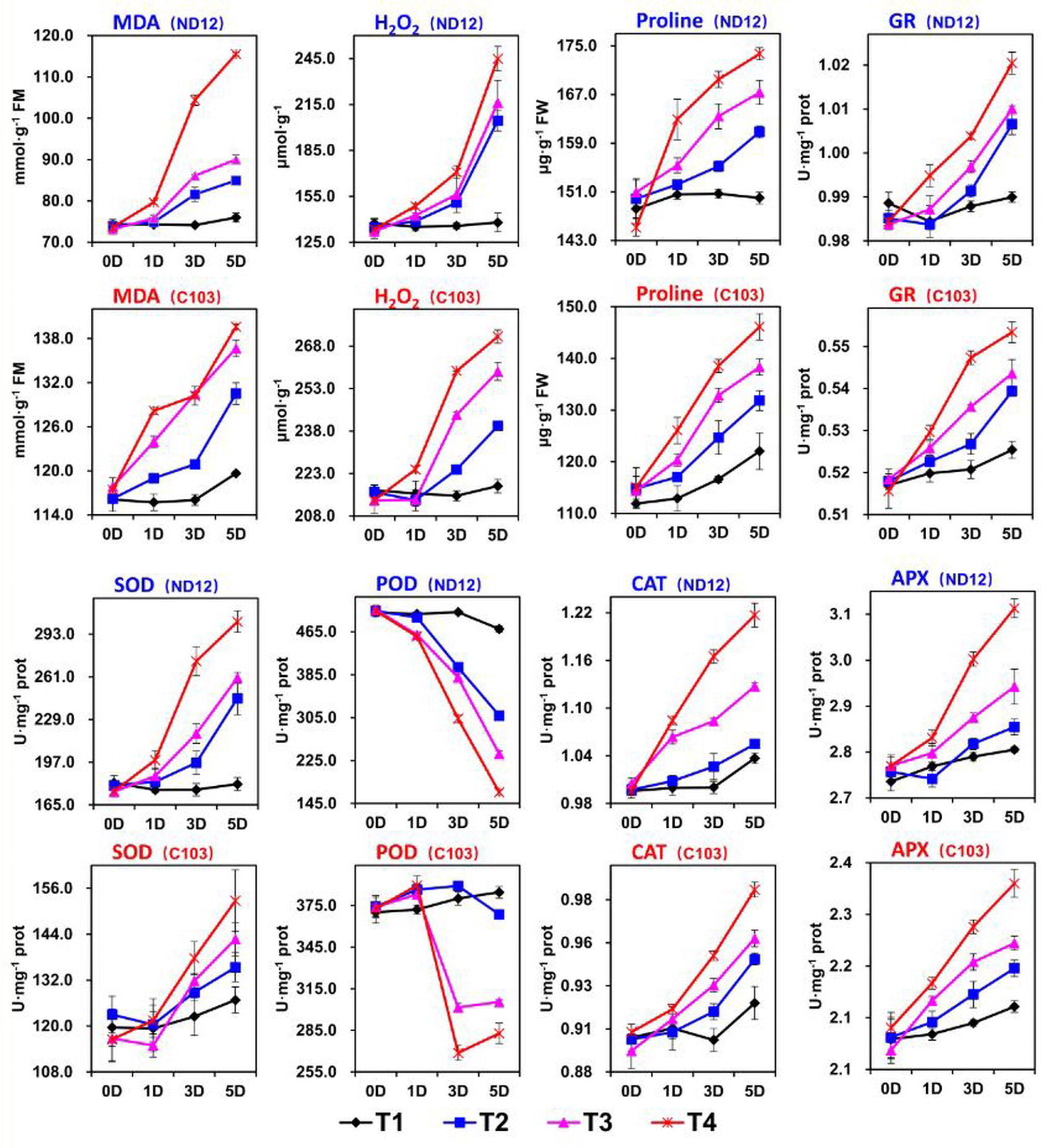

In this experiment, we examined the effects of imbalanced water deficit on the levels of MDA and H2O2 in the leaves of soybean seedlings. Different split-root PEG treatments (SRP) indicated a significant (p < 0.05) effect on the ROS levels in ND-12 and C-103 from 0 to 5 days (Figure 2). Between both cultivars, the highest average MDA (131.6 nmol mg−1 prot) and H2O2 (247.1 μmol g−1) were measured in C-103, while the lowest MDA (91.63 nmol mg−1 prot) and H2O2 (200.8 μmol g−1) were recorded in ND-12 at the 5th day of sampling. All the SRP treatments significantly affected the ROS levels in soybean seedlings; the maximum (127.5 nmol mg−1 prot and 258.1 μmol g−1) and minimum (97.8 nmol mg−1 prot and 178.2 μmol g−1) values of MDA and H2O2 were measured in the T4 and T1 treatments, respectively, on the 5th day of sampling (Figure 2). The interactive effect of soybean cultivars and SRP treatments for MDA was significant for all sampling days except at day 0. On average, on the 5th day of sampling, T4 increased the levels of MDA and H2O2 by 30 and 45%, respectively, compared to T1 (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Effect of different split-root PEG treatments on reactive oxygen species, enzymatic activity and proline of two soybean cultivars, ND-12 (drought-resistant) and C-103 (drought-susceptible). (Mean ± SE). T1 (0%: 0%), T2 (2%A: 0%B), T3 (6%A: 0%B), and T4 (4%A: 6%B).

Effect of Imbalanced Water Deficit on Soybean Antioxidative Enzymes

Plants activate their defense system to eliminate ROS. Major enzymes that scavenge ROS include CAT, SOD, APX, and POD. In this experiment, SRP treatments and soybean cultivars showed a significant effect on the activities of SOD, CAT, GR, APX, and POD, and maximum activities of these enzymes were obtained by ND-12 and C-103 (Figure 2). Furthermore, enzymatic activities of SOD, GR, CAT, and APX increased with the increase in SRP concentration, with their maximum activities measured in T4 and minimum activities in treatment T1 on the 5th day of measurement. Overall, on the 5th day of measurement, treatment T4 increased the SOD, GR, CAT, and APX activities by 48, 4, 13, and 10%, respectively, over treatment T1. However, the activity of POD significantly (p < 0.05) decreased with the increase in PEG concentration. Specifically, on the 5th day of measurement, the activity of POD reduced by 91, 58, and 26% in T4, T3, and T2, respectively, compared to that in T1. The interactive effect of SRP treatments and soybean cultivars for GR was found nonsignificant and significant at 0, 1, and 5 day and at 3 day intervals, respectively; for POD and CAT, it was found nonsignificant and significant at 0 days and at 1, 3, and 5 days, respectively; and for SOD and APX, it was found nonsignificant and significant at 0 and 1 days and at 3 and 5 days, respectively (Figure 2).

Effect of Imbalanced Water Deficit on Proline

Plants accumulate free proline under water-limited conditions. In this study, cultivars exhibited significant differences in free proline. The highest (162.9 μg g−1) and the lowest (134.5 μg g−1) proline accumulation in soybean seedlings were noted in cultivar ND-12 and C-103, respectively, on the 5th day of measurement. Additionally, free proline significantly increased with SRP concentration. The maximum (159.9 μg g−1) and minimum (136.0 μg g−1) values of free proline were measured in the T4 and T1 treatments, respectively, on the 5th day of sampling (Figure 2). The interactive effect of SRP treatments and soybean cultivars for the accumulation of free proline was nonsignificant.

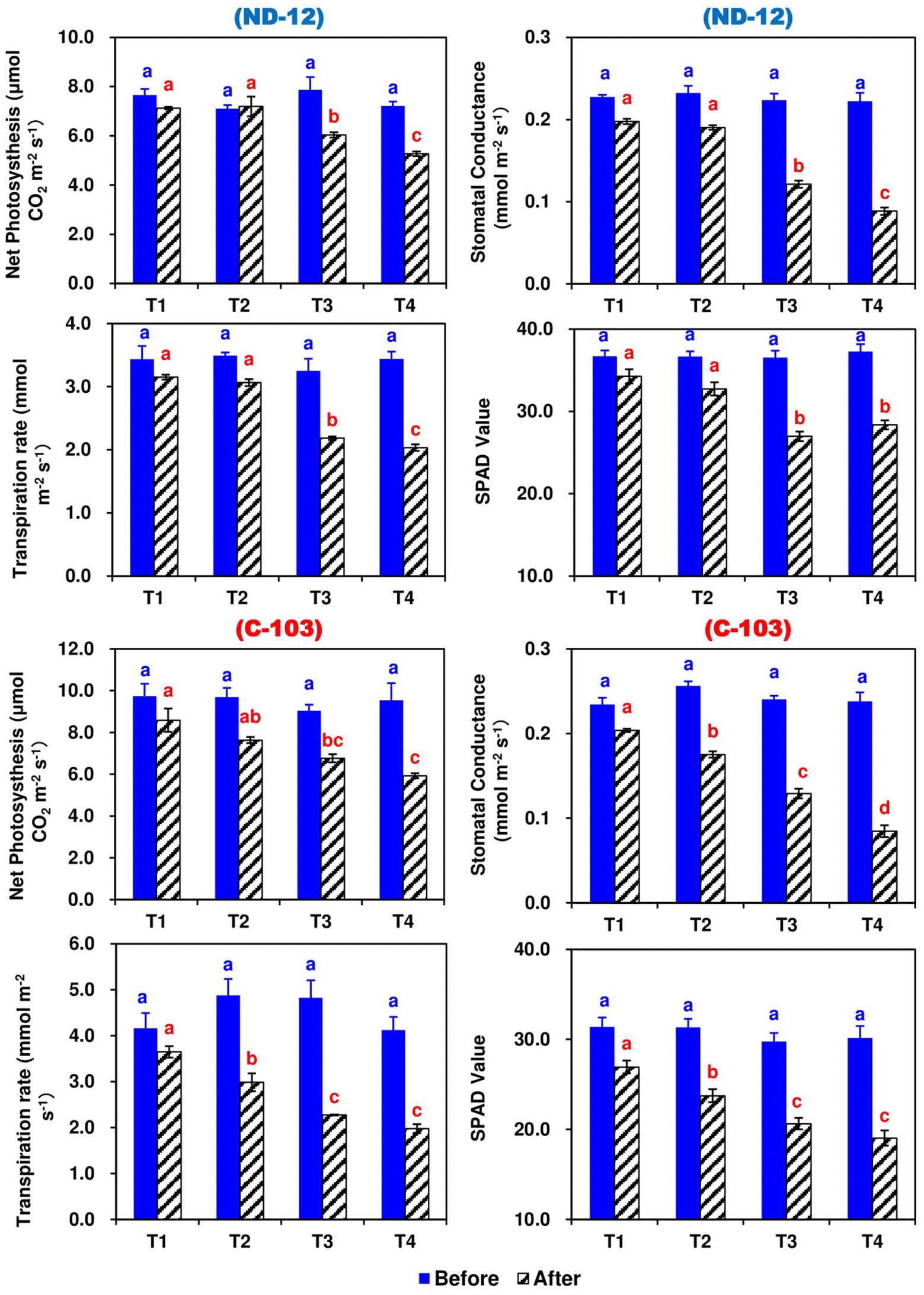

Effect of Imbalanced Water Deficit on Photosynthetic Parameters

The effect of different SRP treatments and soybean cultivars on the photosynthetic rate (PN), transpiration rate (E), stomatal conductance (gs), and chlorophyll content (Chl) in the leaves of soybean are shown in Figure 3. Prior to the applied stress, the values of these traits were significantly higher among all treatments and no changes were observed. However, after 5 days of stress, different SRP treatments significantly affected the PN, E, gs, and Chl contents of the soybean cultivars. Maximums for PN (7.8545 and 7.4134 CO2 m−2 s−1), E (3.3980 and 3.0253 mmol m−2 s−1), gs (0.2007 and 0.1828 mmol m−2 s−1), and Chl contents (30.60 and 28.23) were measured in T1 and T2, while minimums for PN (5.6004 CO2 m−2 s−1), E (2.0056 mmol m−2 s−1), gs (0.0866 mmol m−2 s−1), and Chl contents (23.70) were noted under the T4 treatment. Among soybean cultivars, the highest values of PN (7.2273 CO2 m−2 s−1) and E (2.7206 mmol m−2 s−1) were noted for C-103, whereas the highest values of gs (0.1495 mmol m−2 s−1) and Chl contents (30.58) were observed in cultivar ND-12. The interactive effect of SRP treatments and soybean cultivars for photosynthetic parameters were found to be significant (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Effect of different split-root PEG treatments on photosynthetic parameters of two soybean cultivars, ND-12 (drought resistant) and C-103 (drought susceptible). (Mean ± SE), same small letters are not significantly different at p < 0.05. T1 (0%: 0%), T2 (2%A: 0%B), T3 (6%A: 0%B), and T4 (4%A: 6%B).

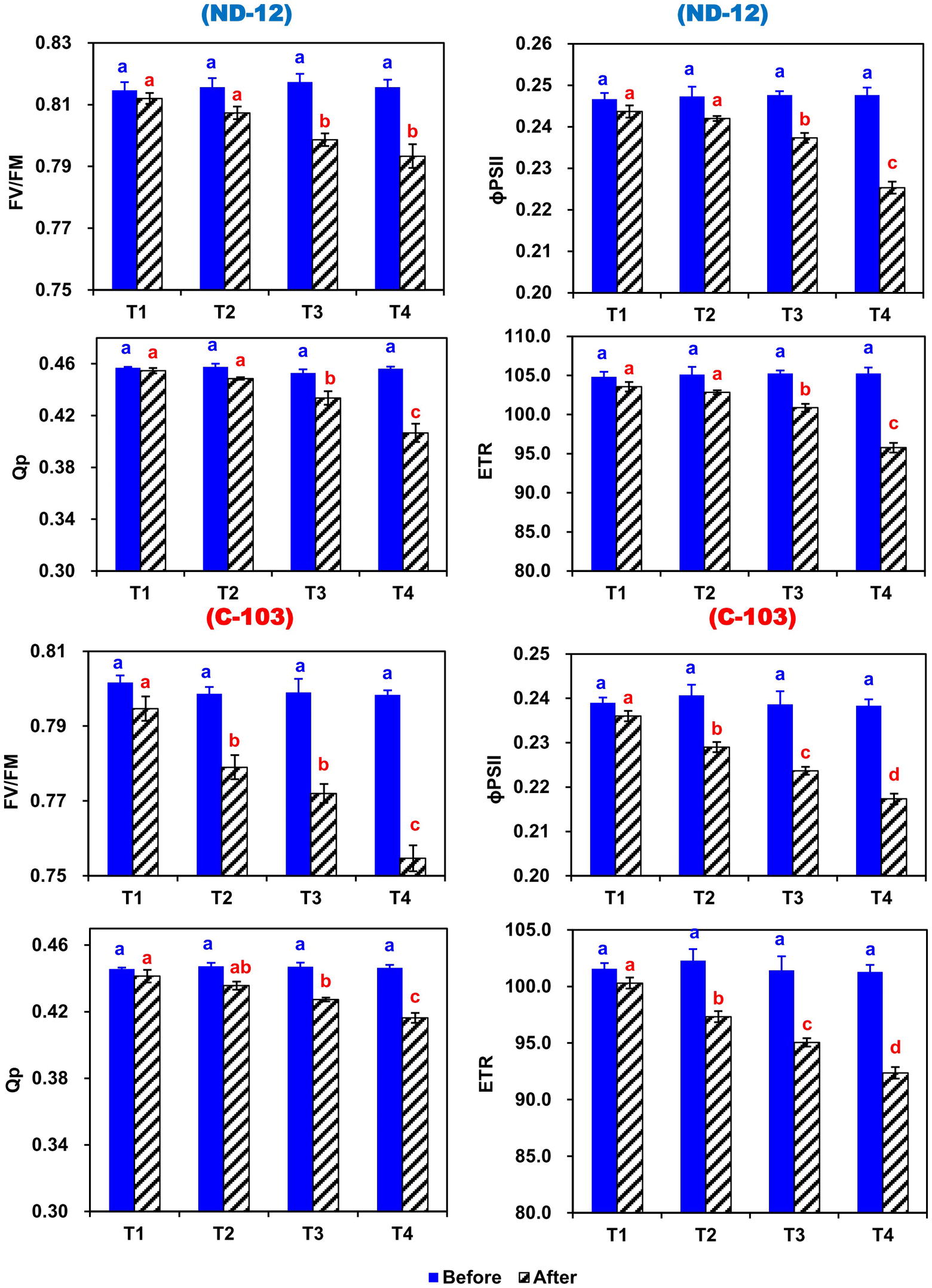

Effect of Imbalanced Water Deficit on Chlorophyll Fluorescence Parameters of Soybean

In this experiment, the chlorophyll fluorescence significantly changed during the experimental period in response to induced imbalanced water deficit conditions (Figure 4). Prior to the applied stress, there was a nonsignificant difference in maximum quantum yield (Fv/Fm), photochemical quenching (qP), effective quantum yield of photosystem (ɸPSII) and electron transport rate (ETR). After 5 days of stress, the Fv/Fm, qP, ɸPSII, and ETR of both soybean cultivars showed significant changes under different SRP treatments. In soybean cultivars, the maximum (0.8028, 0.4359, 0.2371, and 100.76) and minimum (0.7751, 0.4302, 0.2265, and 96.26) values of Fv/Fm, qP, ɸPSII, and ETR were observed in ND-12 and C-103, respectively. Among SRP treatments, the maximum values of Fv/Fm (0.8033 and 0.7932), qP (0.4480 and 0.4422), ɸPSII (0.2398 and 0.2355), and ETR (101.93 and 100.09) were noticed under treatments T1 and T2, while minimum concentrations of Fv/Fm (0.7740), qP (0.4115), ɸPSII (0.2213), and ETR (94.07) were measured in T4. The interactive effect of SRP treatments and soybean cultivars for Fv/Fm, qP, ɸPSII, and ETR were found to be significant. Overall, relative to treatment T1, the Fv/Fm, qP, ɸPSII, and ETR decreased by 4, 9, 8, and 8%, respectively, under the T4 treatment, indicating that changes in photosynthetic rate under imbalanced water deficit conditions were directly associated with the changes in chlorophyll fluorescence parameters.

Figure 4. Effect of different split-root PEG treatments on chlorophyll fluorescence parameters of two soybean cultivars ND-12 (drought-resistant) and C-103 (drought-susceptible). (Mean ± SE), same small letters are not significantly different at p < 0.05. T1 (0%: 0%), T2 (2%A: 0%B), T3 (6%A: 0%B), and T4 (4%A: 6%B). Maximum quantum yield (Fv/Fm), effective quantum yield of photosystem (ɸPSII), photochemical quenching (qP), and electron transport rate (ETR).

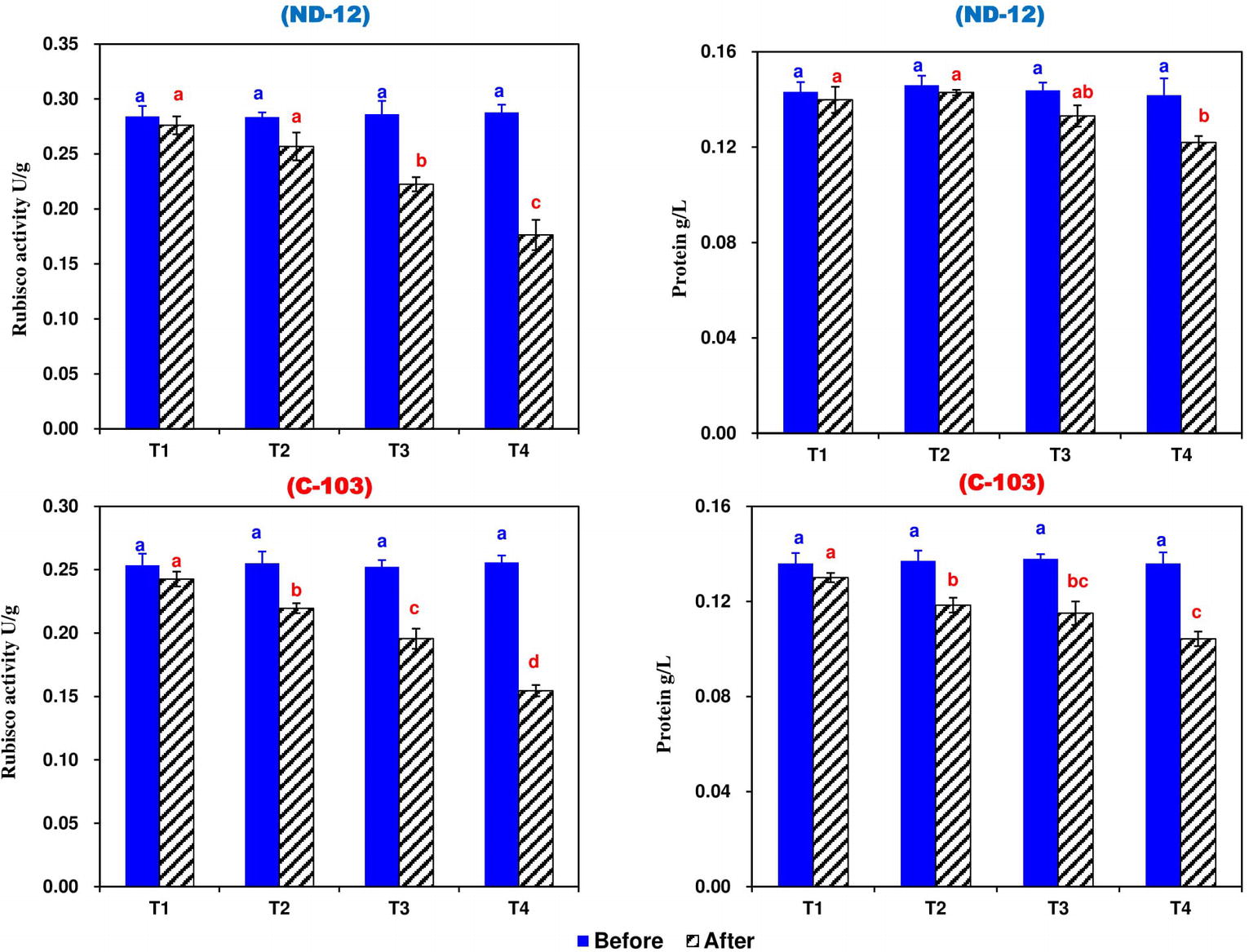

Effect of Imbalanced Water Deficit on Rubisco Activity (RA) and Total Soluble Protein of Soybean

Prior to the stress applied, the RA and total soluble protein were significantly higher among all treatments compared to the control and no changes were observed, while after stress treatment, SRP treatments significantly affected the RA and total soluble protein of soybean cultivars. The maximum RA (0.2329 U g−1) and total soluble protein (0.1345 g L−1) were noted in ND-12, while the minimum RA (0.2031 U g−1) and total soluble protein (0.1169 g L−1) were observed in C-103. Among the SRP treatments, the maximum RA (0.2593 and 0.2382 U g−1) and total soluble protein (0.1349 and 0.1307 g L−1) were measured in T1 and T2, while the minimum RA (0.1654 U g−1) and total soluble protein (0.1131 g L−1) were noted under the T4 treatment. The interactive effect of different SRP treatments and soybean cultivars for RA and total soluble protein were found to be significant (Figure 5). These results suggest that the RA and total soluble protein were inhibited more obviously in ND-12 than in C-103, which in turn improves the chlorophyll fluorescence and photosynthetic parameters of ND-12 under the imbalanced water deficit conditions.

Figure 5. Effect of different split-root PEG treatments on Rubisco activity and total soluble protein of two soybean cultivars, ND-12 (drought-resistant) and C-103 (drought-susceptible). (Mean ± SE), same small letters are not significantly different at p < 0.05. T1 (0%: 0%), T2 (2%A: 0%B), T3 (6%A: 0%B), and T4 (4%A: 6%B).

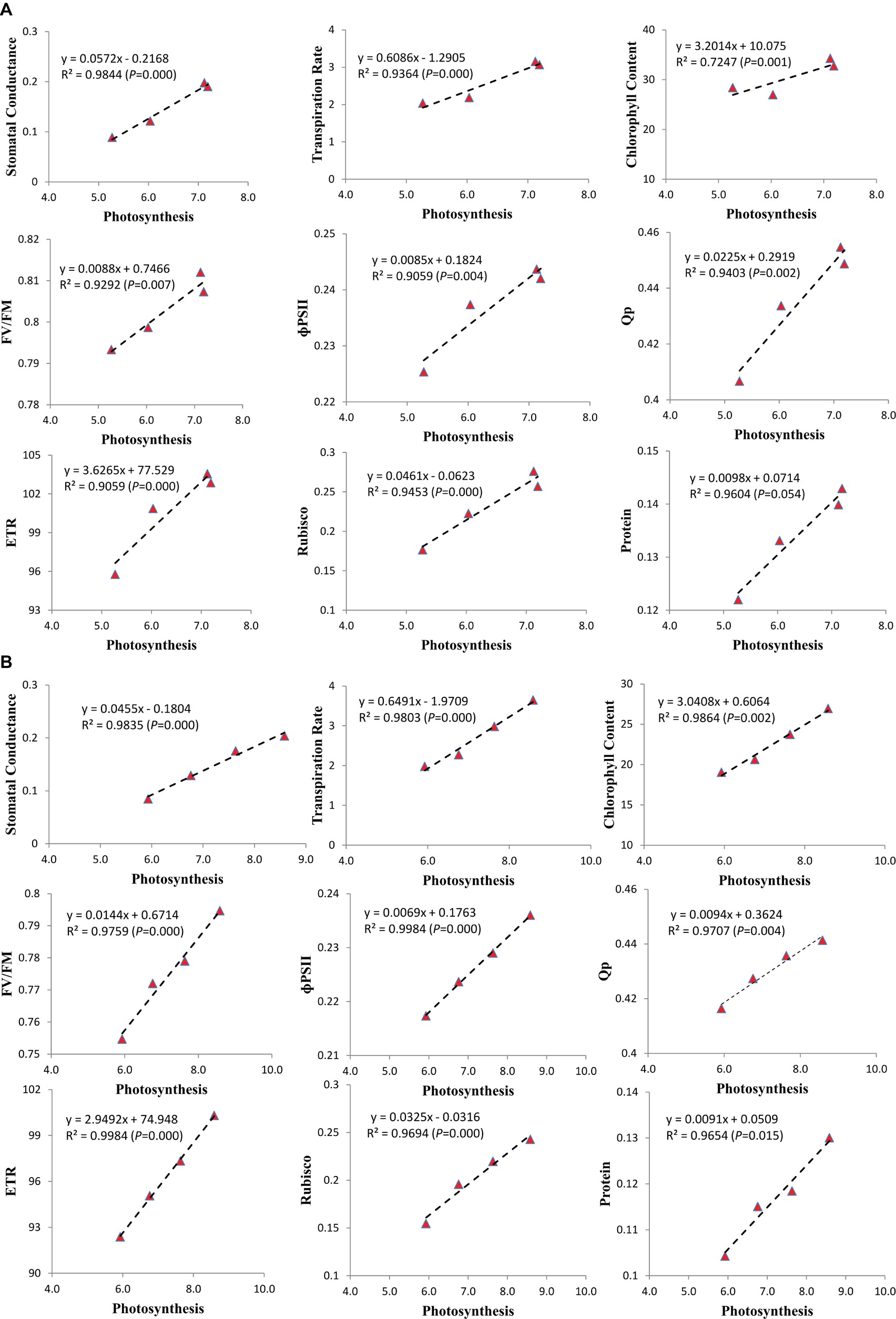

Correlation

To recognize the most critical photosynthetic parameters affecting soybean growth, the relationship between the increasing photosynthetic rate and photosynthetic characteristics was drawn (Figure 6). Among the photosynthetic parameters of soybean cultivars, the stomatal conductance, transpiration rate, chlorophyll content, chlorophyll fluorescence characteristics (FV/FM, PSII, qP, and ETR), RA, and protein content of both cultivars increased with the increase in photosynthetic rate. We found that the stomatal conductance (R2 = 0.9844 and 0.9835, p = 0.000 and 0.000), transpiration rate (R2 = 0.9364 and 0.9803, p = 0.000 and 0.000), chlorophyll content (R2 = 0.7247 and 0.9864, p = 0.001 and 0.002), FV/FM (R2 = 0.9292 and 0.9759, p = 0.007 and 0.000), ɸPSII (R2 = 0.9059 and 0.9984, p = 0.004 and 0.000), Qp (R2 = 0.9403 and 0.9707, p = 0.002 and 0.004), ETR (R2 = 0.9059 and 0.9984, p = 0.000 and 0.000), RA (R2 = 0.9453 and 0.9694, p = 0.000 and 0.000) and protein content (R2 = 0.9604 and 0.9654, p = 0.054 and 0.015) of ND-12 and C-103, respectively, at the V4 soybean growth stage were strongly and positively (p < 0.05) related to the increasing photosynthetic rate of soybean plants. The correlation coefficient between all the measured parameters and increasing photosynthetic rate for the mean data sets of cultivars ND-12 and C-103 were all higher than 0.00 (p < 0.05).

Figure 6. Relationship of photosynthesis with the stomatal conductance, transpiration rate, chlorophyll content, chlorophyll fluorescence parameters, Rubisco activity and protein of soybean seedlings in (A) (ND-12) and (B) (C-103). Correlation coefficients (R) are calculated and significance (P) represents significance at the 0.05 probability.

Discussion

Effect of Imbalanced Water Deficit on Soybean ROS and Antioxidant Enzymes

Environmental stresses have been known to cause oxidative injuries by increasing the levels of ROS; excessive production of ROS can severely damage plant metabolism (Sinha et al., 2016). ROS enhances the effects of water stress by disturbing the cell membrane of plants and causing oxidative impairment to chlorophyll pigments, lipids, protein, and DNA, which altogether lead to cell death. In this study, a clear increase in MDA and H2O2 content was recorded in both cultivars in response to enhanced split-root PEG stress. However, better protection from oxidative damage was observed in the ND-12 cultivar than in C-103 due to its lowered MDA and H2O2 content. The highest concentration of H2O2 is attributed to lipids, proteins, and nucleic acid oxidization, which led to inactivation of photosystems I and II. These findings are consistent with the previous reports where MDA and H2O2 content increased in soybean leaves under water-limited conditions (Türkan et al., 2005; Shen et al., 2010).

To prevent cellular damage, plants mobilize the antioxidant defense system to eliminate ROS. In this study, soybean cultivars increased enzyme activities, which may be attributed to the protection of plants from an imbalanced water deficit. These findings are consistent with an earlier study in which water deficit caused an increase in the enzymatic activities except for POD in soybean (Shen et al., 2015). In addition, enzyme activities varied between the two soybean cultivars. However, these changes in enzymatic activities are dependent on plant age, species, treatment durations, and experimental conditions (Pan et al., 2006). Higher values of ROS and lower antioxidant enzyme activities in C-103 might be due to its low drought tolerance. Eventually, these conditions caused injuries to the plant by increasing ROS production.

The increase in proline is a common response of plants under water deficit conditions. Proline protects the stressed cells by adjusting intercellular osmotic potential in soybean (Heerden and Kruger, 2002). In this study, soybean cultivars increased the free proline content, which may be attributed to high water retention. A higher value of proline accumulation in ND-12 showed its high water retention ability compared to C-103. The results of this study are in agreement with those of earlier investigators, who noted a significant increase in free proline in soybean in response to water stress (Shen et al., 2010; Sharma et al., 2012).

Effect of Imbalanced Water Deficit on Photosynthetic Characteristics of Soybean

Split-root drought is a smart approach to minimize water loss and maximize crop productivity (Iqbal et al., 2019). Plants have the ability to perceive dried soil and reduce water use by regulating certain physiological and biochemical changes in the dry segment of the root zone (Mingo et al., 2004). In the present studies, two soybean cultivars were grown in Hoagland solution to know the physiological response of soybean seedlings against imbalanced water deficit conditions. PN, gs, and E were significantly higher before the treatment application. Plants under SRP treatments maintained significantly lower values of these parameters. Retardation of photosynthesis resulted in low agricultural productivity, and a decrease in PN was attributed to the decrease in gs and intercellular CO2 concentration in drought-stressed plants (Chaves et al., 2009). These results are consistent with the earlier report where PN, gs, and E were significantly decreased in partial-root drying of tomato grown in a greenhouse (Campos et al., 2009). However, these parameters varied between both cultivars. In ND-12, the values of PN, gs, and E were not significantly different under treatments T1 and T2, which was the reason for its high drought resistance.

A sharp decrease in RA is considered an early response to drought stress in soybean (Bota et al., 2004). This decrease was significantly higher in drought-stressed plants compared to the control. In this study, the results showed that RA remained higher before treatment application and a strong reduction was often found after T2 and T3 in ND-12 and C-103, respectively. Treatment T2 reduced RA by 10% in C-103 and only 7% in ND-12. As described above, PN and gs were more inhibited in ND-12 than in C-103 under imbalanced water deficit treatments. These results are in line with earlier findings that the downregulation of RA is induced by gs (Flexas et al., 2006) and suppression of Rubisco could be the possible reason for the low photosynthetic rate (Pietrini et al., 2003). However, the mechanism for decreased RA seems species-dependent. In principle, decreased RA could be the consequence of decreased soluble protein concentration (Bota et al., 2004). In this study, RA and total soluble protein were more inhibited in ND-12 than in C-103 under imbalanced water deficit treatments. However, it cannot be evaluated in terms of alterations in total soluble protein contents, as there are some other possibilities (Zhang et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2017b). Therefore, the physiological meaning of these adjustments deserves detailed attention in the future.

In addition, the chlorophyll content decreased as the levels of PEG increased in both cultivars. Relatively lower values of chlorophyll were found for C-103, which supports the view that this cultivar is more affected by imbalanced water deficit conditions. Reduction in chlorophyll content is attributed as a typical symptom of oxidative stress and has been reported in earlier studies (Gunes et al., 2008; Masoumi et al., 2010). Chlorophyll degradation and pigment photo-oxidation caused by chlorophyll reduction ultimately inactivates photosynthesis (Hajihashemi and Ehsanpour, 2013). Therefore, the current study clearly showed that the reduction of chlorophyll content also affected soybean photosynthesis.

Increased photosynthetic capacity accompanies a high quantity of electrons passing through PSII (Yao et al., 2017). Under different environmental conditions (sensitivity and convenience), parameters derived from chlorophyll fluorescence measurements can indicate changes in photosynthesis (Dai et al., 2009). A decrease in plant growth under drought is due to lower energy absorbed by the leaf and subsequently translocated to PSII (Rahbarian et al., 2011; Kalaji et al., 2014). In the present study in soybean plants, as the stress increased, Fv/Fm, qP, PSII, and ETR were significantly lower. However, the decrease in chlorophyll fluorescence parameters in ND-12 occurred later than that in C-103. The results showed that the limitations of these parameters were similar to that of PN. However, no significant decrease in chlorophyll fluorescence parameters was observed in ND-12 (drought-resistant) under T1 and T2, suggesting that the PSII structural integrity of the resistant soybean cultivar was not injured by imbalanced water deficit conditions. Our results are similar to those of Piper et al. (2007) and Mao et al. (2018), where the Fv/Fm ratio was higher in resistant than in susceptible cultivars (Piper et al., 2007; Mao et al., 2018). Thus, our results suggest that under imbalanced water deficits conditions, the efficiency of PSII increases in the resistant cultivar. Improving the energy transport from PSII to PSI may enhance photosynthesis.

Conclusion

This research will ensure a better understanding of the response mechanisms of plants to imbalanced WDC. Biased application of PEG treatments reduced the oxidative stress by upregulating the enzymatic activities of key enzymes (SOD, POD, CAT, GR, and APX). Compared to normal conditions, the split-root PEG treatment T4 increased the MDA and H2O2 of soybean plants by 30 and 45%, respectively, on the 5th day of sampling. In response to ROS, antioxidant activities of SOD, CAT, GR, and APX improved by 48 13, 4, and 10%, respectively, in T4 over T1 on the 5th day of measurement in both cultivars. Furthermore, imbalanced WDC (T4) decreased the efficiency of PSII by regulating chlorophyll fluorescence (Fv/Fm, qP, PSII, and ETR) by 2, 12, 8, and 8% in ND-12 and 5, 6, 9, and 9% in C-103, respectively. Additionally, the activities of Rubisco were significantly reduced under T4 treatment, which in turn decreased the photosynthesis of soybean seedling. Furthermore, increased enzymatic activity, photosynthetic efficiency, RA and total soluble protein upon high PEG application in both cultivars ensured healthier plant growth, particularly in the drought-tolerant cultivar (ND-12). The results of the current study suggested that the appropriate cultivars and imbalanced WDC of T2 can modify the photosynthetic performance of plants, especially in intercropping systems.

Author Contributions

NI and C-QY helped in data curation. SH and MR helped in formal analysis. WY, WC, and ZJ helped in funding acquisition. NI and SH developed the methodology. JL collected the resources. WY and JL helped in supervision MS and MH helped in validation. NI, SH, and MB helped in writing—original draft. MS, AA, and MA helped in writing—review and editing.

Funding

The authors are grateful to the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2016YFD0300209), China Agriculture Research System (CARS-04-PS19), National Natural Science Foundation of China (31301277), and project APVV- 15-0721 for providing the funds for this study. We would also like to acknowledge WC and ZJ for supporting this study.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphys.2019.00786/full#supplementary-material

References

Ahmad, P., Jaleel, C. A., Salem, M. A., Nabi, G., and Sharma, S. (2010). Roles of enzymatic and nonenzymatic antioxidants in plants during abiotic stress. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 30, 161–175. doi: 10.3109/07388550903524243

Bates, L. S., Waldren, R. P., and Teare, I. (1973). Rapid determination of free proline for water-stress studies. Plant Soil 39, 205–207. doi: 10.1007/BF00018060

Batra, N. G., Sharma, V., and Kumari, N. (2014). Drought-induced changes in chlorophyll fluorescence, photosynthetic pigments, and thylakoid membrane proteins of Vigna radiata. J. Plant Interact. 9, 712–721. doi: 10.1080/17429145.2014.905801

Beis, A., and Patakas, A. (2015). Differential physiological and biochemical responses to drought in grapevines subjected to partial root drying and deficit irrigation. Eur. J. Agron. 62, 90–97. doi: 10.1016/j.eja.2014.10.001

Bota, J., Medrano, H., and Flexas, J. (2004). Is photosynthesis limited by decreased Rubisco activity and RuBP content under progressive water stress? New Phytol. 162, 671–681. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2004.01056.x

Campos, H., Trejo, C., Pena-Valdivia, C. B., Ramírez-Ayala, C., and Sánchez-García, P. (2009). Effect of partial rootzone drying on growth, gas exchange, and yield of tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.). Sci. Hortic. 120, 493–499. doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2008.12.014

Chaves, M. M., Flexas, J., and Pinheiro, C. (2009). Photosynthesis under drought and salt stress: regulation mechanisms from whole plant to cell. Ann. Bot. 103, 551–560. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcn125

Dai, Y., Shen, Z., Liu, Y., Wang, L., Hannaway, D., and Lu, H. (2009). Effects of shade treatments on the photosynthetic capacity, chlorophyll fluorescence, and chlorophyll content of Tetrastigma hemsleyanum Diels et Gilg. Environ. Exp. Bot. 65, 177–182. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2008.12.008

Evans, J. R., and Seemann, J. R. (1989). “The allocation of protein nitrogen in the photosynthetic apparatus: costs, consequences, and control” in Photosynthesis. ed. W. R. Briggs (New York: Alan R. Liss, Inc.), 183–205.

Fan, H., Ding, L., Xu, Y., and Du, C. (2017). Antioxidant system and photosynthetic characteristics responses to short-term PEG-induced drought stress in cucumber seedling leaves. Russ. J. Plant Physiol. 64, 162–173. doi: 10.1134/S1021443717020042

Flexas, J., Ribas-Carbó, M., Bota, J., Galmés, J., Henkle, M., Martínez-Cañellas, S., et al. (2006). Decreased Rubisco activity during water stress is not induced by decreased relative water content but related to conditions of low stomatal conductance and chloroplast CO2 concentration. New Phytol. 172, 73–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2006.01794.x

Galmés, J., Ribas-Carbó, M., Medrano, H., and Flexas, J. (2011). Rubisco activity in Mediterranean species is regulated by the chloroplastic CO2 concentration under water stress. J. Exp. Bot. 62, 653–665. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erq303

Grassi, G., and Magnani, F. (2005). Stomatal, mesophyll conductance and biochemical limitations to photosynthesis as affected by drought and leaf ontogeny in ash and oak trees. Plant Cell Environ. 28, 834–849. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2005.01333.x

Gunes, A., Inal, A., Adak, M., Bagci, E., Cicek, N., and Eraslan, F. (2008). Effect of drought stress implemented at pre-or post-anthesis stage on some physiological parameters as screening criteria in chickpea cultivars. Russ. J. Plant Physiol. 55, 59–67. doi: 10.1134/S102144370801007X

Guo, Y., Tian, S., Liu, S., Wang, W., and Sui, N. (2018). Energy dissipation and antioxidant enzyme system protect photosystem II of sweet sorghum under drought stress. Photosynthetica 56, 1–12. doi: 10.1007/s11099-017-0741-0

Hajihashemi, S., and Ehsanpour, A. A. (2013). Influence of exogenously applied paclobutrazol on some physiological traits and growth of Stevia rebaudiana under in vitro drought stress. Biologia 68, 414–420. doi: 10.2478/s11756-013-0165-7

Heerden, P. D. R. V., and Kruger, G. H. J. (2002). Separately and simultaneously induced dark chilling and drought stress effects on photosynthesis, proline accumulation and antioxidant metabolism in soybean. J. Plant Physiol. 159, 1077–1086. doi: 10.1078/0176-1617-00745

Hussain, S., Iqbal, N., Brestic, M., Raza, M. A., Pang, T., Langham, D. R., et al. (2019). Changes in morphology, chlorophyll fluorescence performance and Rubisco activity of soybean in response to foliar application of ionic titanium under normal light and shade environment. Sci. Total Environ. 658, 626–637. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.12.182

Iqbal, N., Hussain, S., Ahmed, Z., Yang, F., Wang, X., Liu, W., et al. (2018a). Comparative analysis of maize–soybean strip intercropping systems: a review. Plant Prod. Sci. 22, 1–12. doi: 10.1080/1343943X.2018.1541137

Iqbal, N., Hussain, S., Raza, M. A., Safdar, M. E., Hayyat, M. S., Shafiq, I., et al. (2019). Exploring half root-stress approach: current knowledge and future prospects. Plant Prod. Sci. 1–11. doi: 10.1080/1343943X.2019.1604145 (just-accepted)

Iqbal, N., Hussain, S., Zhang, X.-W., Yang, C.-Q., Raza, M. A., Deng, J.-C., et al. (2018b). Imbalance water deficit improves the seed yield and quality of soybean. Agronomy 8:168. doi: 10.3390/agronomy8090168

Kalaji, H., Rastogi, A., Živčák, M., Brestic, M., Daszkowska-Golec, A., Sitko, K., et al. (2018). Prompt chlorophyll fluorescence as a tool for crop phenotyping: an example of barley landraces exposed to various abiotic stress factors. Photosynthetica 56, 953–961. doi: 10.1007/s11099-018-0766-z

Kalaji, H. M., Schansker, G., Ladle, R. J., Goltsev, V., Bosa, K., Allakhverdiev, S. I., et al. (2014). Frequently asked questions about in vivo chlorophyll fluorescence: practical issues. Photosynth. Res. 122, 121–158. doi: 10.1007/s11120-014-0024-6

Lawlor, D. W., and Tezara, W. (2009). Causes of decreased photosynthetic rate and metabolic capacity in water-deficient leaf cells: a critical evaluation of mechanisms and integration of processes. Ann. Bot. 103, 561–579. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcn244

Liu, X., Rahman, T., Song, C., Su, B., Yang, F., Yong, T., et al. (2017a). Changes in light environment, morphology, growth and yield of soybean in maize-soybean intercropping systems. Field Crop Res. 200, 38–46. doi: 10.1016/j.fcr.2016.10.003

Liu, Y., Song, Q., Li, D., Yang, X., and Li, D. (2017b). Multifunctional roles of plant dehydrins in response to environmental stresses. Front. Plant Sci. 8:1018. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.01018

Mao, H., Chen, M., Su, Y., Wu, N., Yuan, M., Yuan, S., et al. (2018). Comparison on photosynthesis and antioxidant defense systems in wheat with different ploidy levels and octoploid triticale. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19:3006. doi: 10.3390/ijms19103006

Masoumi, H., Masoumi, M., Darvish, F., Daneshian, J., Nourmohammadi, G., and Habibi, D. (2010). Change in several antioxidant enzymes activity and seed yield by water deficit stress in soybean (Glycine max L.) cultivars. Notulae Botanicae Horti Agrobotanici Cluj-Napoca 38, 86–94. doi: 10.15835/nbha3834936

Mingo, D. M., Theobald, J. C., Bacon, M. A., Davies, W. J., and Dodd, I. C. (2004). Biomass allocation in tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum) plants grown under partial rootzone drying: enhancement of root growth. Funct. Plant Biol. 31, 971–978. doi: 10.1071/FP04020

Olechowicz, J., Chomontowski, C., Olechowicz, P., Pietkiewicz, S., Jajoo, A., and Kalaji, M. (2018). Impact of intraspecific competition on photosynthetic apparatus efficiency in potato (Solanum tuberosum) plants. Photosynthetica 56, 971–975. doi: 10.1007/s11099-017-0728-x

Pan, Y., Lu, Z., Lu, J., Li, X., Cong, R., and Ren, T. (2017). Effects of low sink demand on leaf photosynthesis under potassium deficiency. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 113, 110–121. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2017.01.027

Pan, Y., Wu, L. J., and Yu, Z. L. (2006). Effect of salt and drought stress on antioxidant enzymes activities and SOD isoenzymes of liquorice (Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch). Plant Growth Regul. 49, 157–165. doi: 10.1007/s10725-006-9101-y

Pei, Z.-M., Murata, Y., Benning, G., Thomine, S., Klüsener, B., Allen, G. J., et al. (2000). Calcium channels activated by hydrogen peroxide mediate abscisic acid signalling in guard cells. Nature 406, 731–734. doi: 10.1038/35021067

Pietrini, F., Iannelli, M. A., Pasqualini, S., and Massacci, A. (2003). Interaction of cadmium with glutathione and photosynthesis in developing leaves and chloroplasts of Phragmites australis (Cav.) Trin. Ex Steudel. Plant Physiol. 133, 829–837. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.026518

Piper, F. I., Corcuera, L. J., Alberdi, M., and Lusk, C. (2007). Differential photosynthetic and survival responses to soil drought in two evergreen Nothofagus species. Ann. For. Sci. 64, 447–452. doi: 10.1051/forest:2007022

Prasad, A., Kumar, A., Suzuki, M., Kikuchi, H., Sugai, T., Kobayashi, M., et al. (2015). Detection of hydrogen peroxide in photosystem II (PSII) using catalytic amperometric biosensor. Front. Plant Sci. 6:862. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.00862

Prasad, A., Sedlářová, M., and Pospíšil, P. (2018). Singlet oxygen imaging using fluorescent probe singlet oxygen sensor green in photosynthetic organisms. Sci. Rep. 8:13685. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-31638-5

Rahbarian, R., Khavari-Nejad, R., Ganjeali, A., Bagheri, A., and Najafi, F. (2011). Drought stress effects on photosynthesis, chlorophyll fluorescence and water relations in tolerant and susceptible chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) genotypes. Acta Biol. Cracov. Ser. Bot. 53, 47–56. doi: 10.2478/v10182-011-0007-2

Rahman, T., Ye, L., Liu, X., Iqbal, N., Du, J., Gao, R., et al. (2016). Water use efficiency and water distribution response to different planting patterns in maize–soybean relay strip intercropping systems. Exp. Agric. 53, 1–19. doi: 10.1017/S0014479716000260

Raza, M., Feng, L., Iqbal, N., Manaf, A., Khalid, M., Wasaya, A., et al. (2018a). Effect of sulphur application on photosynthesis and biomass accumulation of sesame varieties under rainfed conditions. Agronomy 8:149. doi: 10.3390/agronomy8080149

Raza, M. A., Feng, L. Y., Manaf, A., Wasaya, A., Ansar, M., Hussain, A., et al. (2018b). Sulphur application increases seed yield and oil content in sesame seeds under rainfed conditions. Field Crop Res. 218, 51–58. doi: 10.1016/j.fcr.2017.12.024

Sharma, P., Jha, A., Dubey, R., and Pessarakli, M. (2012). Reactive oxygen species, oxidative damage, and antioxidative defense mechanism in plants under stressful conditions. J. Bot. 2012, 1–26. doi: 10.1155/2012/217037

Shen, X., Dong, Z., and Chen, Y. (2015). Drought and UV-B radiation effect on photosynthesis and antioxidant parameters in soybean and maize. Acta Physiol. Plant. 37:25. doi: 10.1007/s11738-015-1778-y

Shen, X., Zhou, Y., Duan, L., Li, Z., Eneji, A. E., and Li, J. (2010). Silicon effects on photosynthesis and antioxidant parameters of soybean seedlings under drought and ultraviolet-B radiation. J. Plant Physiol. 167, 1248–1252. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2010.04.011

Siddique, Z., Jan, S., Imadi, S. R., Gul, A., and Ahmad, P. (2016). “Drought stress and photosynthesis in plants” in Water stress and crop plants: A sustainable approach 2. ed. P. Ahmad, 1–11. doi: 10.1002/9781119054450.ch1

Sinha, R. K., Pospíšil, P., Maheshwari, P., and Eudes, F. (2016). Bcl-2△ 21 and Ac-DEVD-CHO inhibit death of wheat microspores. Front. Plant Sci. 7:1931. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01931

Susana, R.-G., Enrique, M.-N., Anthony, J. D., Francisco, F.-M., Elloy, M. C., Teresa, L., et al. (2007). Growth and photosynthetic responses to salinity of the salt-marsh shrub Atriplex portulacoides. Ann. Bot. 100, 555–563. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcm119

Tardieu, F. (2016). Too many partners in root–shoot signals. Does hydraulics qualify as the only signal that feeds back over time for reliable stomatal control? New Phytol. 212, 802–804. doi: 10.1111/nph.14292

Türkan, I., Bor, M., Özdemir, F., and Koca, H. (2005). Differential responses of lipid peroxidation and antioxidants in the leaves of drought-tolerant P. acutifolius Gray and drought-sensitive P. vulgaris L. subjected to polyethylene glycol mediated water stress. Plant Sci. 168, 223–231. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2004.07.032

Wang, W., Wang, C., Pan, D., Zhang, Y., Luo, B., and Ji, J. (2018). Effects of drought stress on photosynthesis and chlorophyll fluorescence images of soybean (Glycine max) seedlings. Int. J. Agric. & Biol. Eng 11, 196–201. doi: 10.25165/j.ijabe.20181102.3390

Wu, Y., Gong, W., Wang, Y., Yong, T., Yang, F., Liu, W., et al. (2018). Leaf area and photosynthesis of newly emerged trifoliolate leaves are regulated by mature leaves in soybean. J. Plant Res. 131, 1–10. doi: 10.1007/s10265-018-1027-8

Yan, Y., Gong, W., Yang, W., Wan, Y., Chen, X., Chen, Z., et al. (2010). Seed treatment with uniconazole powder improves soybean seedling growth under shading by corn in relay strip intercropping system. Plant Prod. Sci. 13, 367–374. doi: 10.1626/pps.13.367

Yan, J., Tsuichihara, N., Etoh, T., and Iwai, S. (2007). Reactive oxygen species and nitric oxide are involved in ABA inhibition of stomatal opening. Plant Cell Environ. 30, 1320–1325. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2007.01711.x

Yao, X., Li, C., Li, S., Zhu, Q., Zhang, H., Wang, H., et al. (2017). Effect of shade on leaf photosynthetic capacity, light-intercepting, electron transfer and energy distribution of soybeans. Plant Growth Regul. 83, 409–416. doi: 10.1007/s10725-017-0307-y

Zhang, D., Tong, J., He, X., Xu, Z., Xu, L., Wei, P., et al. (2016). A novel soybean intrinsic protein gene, GmTIP2; 3, involved in responding to osmotic stress. Front. Plant Sci. 6:1237. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.01237

Keywords: enzymatic activity, chlorophyll fluorescence, polyethylene glycol, reactive oxygen species, Rubisco activity

Citation: Iqbal N, Hussain S, Raza MA, Yang C-Q, Safdar ME, Brestic M, Aziz A, Hayyat MS, Asghar MA, Wang XC, Zhang J, Yang W and Liu J (2019) Drought Tolerance of Soybean (Glycine max L. Merr.) by Improved Photosynthetic Characteristics and an Efficient Antioxidant Enzyme Activities Under a Split-Root System. Front. Physiol. 10:786. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2019.00786

Edited by:

Ankush Prasad, Palacký University Olomouc, CzechiaReviewed by:

Rakesh Kumar Sinha, Biology Centre (ASCR), CzechiaParvaiz Ahmad, Sri Pratap College Srinagar, India

Copyright © 2019 Iqbal, Hussain, Raza, Yang, Safdar, Brestic, Aziz, Hayyat, Asghar, Wang, Zhang, Yang and Liu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Wenyu Yang, bXNzaXlhbmd3eUBzaWNhdS5lZHUuY24=; Jiang Liu, amlhbmdsaXVAc2ljYXUuZWR1LmNu

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Nasir Iqbal

Nasir Iqbal Sajad Hussain

Sajad Hussain Muhammad Ali Raza

Muhammad Ali Raza Cai-Qiong Yang

Cai-Qiong Yang Muhammad Ehsan Safdar2

Muhammad Ehsan Safdar2 Marian Brestic

Marian Brestic Muhammad Sikander Hayyat

Muhammad Sikander Hayyat Muhammad Ahsan Asghar

Muhammad Ahsan Asghar Jiang Liu

Jiang Liu