94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Physiol. , 30 June 2011

Sec. Membrane Physiology and Membrane Biophysics

volume 2 - 2011 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2011.00033

Rodrigo Alzamora1

Rodrigo Alzamora1 Fiona O’Mahony1

Fiona O’Mahony1 Wing-Hung Ko2

Wing-Hung Ko2 Tiffany Wai-Nga Yip2

Tiffany Wai-Nga Yip2 Derek Carter1

Derek Carter1 Mustapha Irnaten1

Mustapha Irnaten1 Brian Joseph Harvey1*

Brian Joseph Harvey1*Berberine is a plant alkaloid with multiple pharmacological actions, including antidiarrhoeal activity and has been shown to inhibit Cl− secretion in distal colon. The aims of this study were to determine the molecular signaling mechanisms of action of berberine on Cl− secretion and the ion transporter targets. Monolayers of T84 human colonic carcinoma cells grown in permeable supports were placed in Ussing chambers and short-circuit current measured in response to secretagogues and berberine. Whole-cell current recordings were performed in T84 cells using the patch-clamp technique. Berberine decreased forskolin-induced short-circuit current in a concentration-dependent manner (IC50 80 ± 8 μM). In apically permeabilized monolayers and whole-cell current recordings, berberine inhibited a cAMP-dependent and chromanol 293B-sensitive basolateral membrane K+ current by 88%, suggesting inhibition of KCNQ1 K+ channels. Berberine did not affect either apical Cl− conductance or basolateral Na+–K+-ATPase activity. Berberine stimulated p38 MAPK, PKCα and PKA, but had no effect on p42/p44 MAPK and PKCδ. However, berberine pre-treatment prevented stimulation of p42/p44 MAPK by epidermal growth factor. The inhibitory effect of berberine on Cl− secretion was partially blocked by HBDDE (∼65%), an inhibitor of PKCα and to a smaller extent by inhibition of p38 MAPK with SB202190 (∼15%). Berberine treatment induced an increase in association between PKCα and PKA with KCNQ1 and produced phosphorylation of the channel. We conclude that berberine exerts its inhibitory effect on colonic Cl− secretion through inhibition of basolateral KCNQ1 channels responsible for K+ recycling via a PKCα-dependent pathway.

Berberine is a benzodioxoquinolone plant alkaloid isolated from several species of Berberis and Coptis. In Chinese and Hindu medicine, berberine has been used to treat gastroenteritis, abdominal pain, and diarrhea for over two millennia. Various pharmacological actions have been described for berberine, including antimicrobial (Iwasa et al., 1998), anti-inflammatory (Ivanovska and Philipov, 1996), and cardiovascular effects (Lau et al., 2001). In several small-scale clinical trials, berberine has proven effective in the treatment of secretory diarrhea (Rabbani et al., 1987; Tang and Eisenbrand, 1992). Although its therapeutic benefit has been attributed in part to its antimicrobial and antimotility properties (Yamamoto et al., 1993), berberine has been shown to prevent epithelial electrolyte secretion in vitro in rabbit and rat intestine (Guandalini et al., 1987; Taylor and Baird, 1995).

Diarrheal diseases continue to be a major cause of morbidity and mortality in children and elderly people throughout the world. Oral rehydration therapy remains the mainstay of treatment for diarrhea (Taylor and Greenough, 1989). However, in recent years significant effort has been made in the search for antisecretory drugs that will directly inhibit secretory processes within the enterocytes (Ma et al., 2002; Farthing, 2006).

Activated Cl− secretion from the intestinal crypt is thought to play a major role in secretory diarrhea of several aetiologies (Field, 2003). The generation of the electrochemical driving force required for Cl− secretion by crypt epithelial cells depends on their ability to accumulate intracellular Cl− ions to concentrations greater than their electrochemical equilibrium (Barrett and Keely, 2000; Kunzelmann and Mall, 2002). Cl− enters the cell across the basolateral membrane through the activity of Na+–K+-2Cl− cotransporters. The cotransporter is, in turn, driven by a strong inwardly directed electrochemical Na+ gradient established by the basolaterally located Na+–K+-ATPase. In order to maintain the membrane potential at rest and during Cl− secretion, both Na+ and K+ must be recycled out of the cell through the basolateral membrane. The Na+–K+-ATPase serves to recycle Na+, while basolateral potassium channels recycle K+ (Schultheiss and Diener, 1998). The basolateral K+ conductance in intestinal epithelial cells is formed by at least two different types of K+ channels, one activated by Ca2+-mobilizing secretagogues and the other by cAMP-dependent agonists (Heitzmann and Warth, 2008). Electrophysiological studies have revealed the latter to be KCNQ1, a low conductance (1–3 pS) basolateral K+ channel, which is activated during cAMP-stimulated Cl− secretion and inhibited by chromanol 293B and HMR-1556 (Schroeder et al., 2000; Robbins, 2001). As in all secretory epithelia, the channels and transporters of the crypt epithelial cell must operate in concert to achieve vectorial ion transport. Therefore, blockade of specific basolateral K+ conductance would be expected to inhibit the Cl− secretory process.

The T84 cell line is a well-differentiated intestinal human carcinoma cell line proved to be a robust model for the study of molecular mechanisms of intestinal secretion in close to 1,200 publications since the early 1980s (Dharmsathaphorn et al., 1984). Previous studies using T84 cells, grown to confluence and mounted in Ussing chambers, have shown that berberine decreased Cl− secretion in a dose-dependent manner (Taylor and Baird, 1995). More importantly, berberine attenuated the large Cl− secretory current produced by agents that increase intracellular cAMP. However, the specific transport pathways responsible for the inhibitory effect of berberine on Cl− secretion have not been identified. Herein we report on a series of experiments designed to clarify which epithelial transport processes are affected by berberine. Using the short-circuit current technique, we studied the ability of berberine to inhibit Cl− secretion induced by cAMP in T84 cells. Using the pore-forming antibiotics nystatin and amphotericin B to permeabilized the basolateral and apical membranes respectively, we were able to isolate membrane currents and assess the effects of berberine on (1) the apical membrane Cl− conductance, (2) the basolateral membrane Na+–K+-ATPase activity, and (3) the basolateral membrane K+ conductance. Also, we explored the signaling involved in the antisecretory action of berberine in particular the role of protein kinases such as PKC, PKA, mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), and membrane targets such as ion channels and transporters. Our results indicate that berberine inhibits Cl− secretion by decreasing the basolateral membrane K+ conductance and therefore K+ recycling necessary for the generation of the favorable electrochemical gradient required for Cl− secretion.

T84 cells (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA, USA) were cultured in a 1:1 mixture of DMEM and Ham’s F-12 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% non-essential amino acids, 50 U·ml−1 penicillin, 0.05 mg·ml−1 streptomycin, and grown onto Costar Snapwell culture inserts (Corning, Dublin, Ireland) with an area of 1 cm2 for short-circuit current measurements or onto 24 mm Costar Transwell filters (0.4 μm pore) for protein assays. Experiments were conducted on confluent monolayers 8–12 days after culture onto the permeable supports.

T84 cells were grown onto Snapwell inserts and mounted in Ussing chambers (Physiologic Instruments, San Diego, CA, USA). Transepithelial potential difference was clamped to zero using an EVC-4000 voltage-clamp apparatus (World Precision Instruments, UK). The transepithelial short-circuit current (ISC) was recorded using Ag–AgCl electrodes in 3 M KCl agar bridges as previously described (Condliffe et al., 2001). Transepithelial resistance (Rt) was calculated by measuring the ISC resulting from 5-s square voltage pulses (2 or 4 mV) imposed across the monolayer. All preparations were allowed to equilibrate for 30 min before the experiments were performed. Amiloride (50 μM) was added at the start of the experiments to block Na+ absorption. All experiments were performed at 37°C. The ISC was defined as positive for anion flow from the basolateral to apical chamber.

Specific apical Cl− channel conductance and basolateral Na+/K+ pump and K+ channel conductances were isolated and analyzed using a well-established technique consisting of selective membrane permeabilization using ionophores as previously described (DuVall et al., 1998). To investigate the activity of apical Cl− conductance in isolation, the basolateral membrane was permeabilized by addition of 200 μg·ml−1 nystatin in the presence of an apical to basolateral Cl− gradient. Forskolin was then added to the apical and basolateral sides of the monolayers to activate the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR). Under these conditions, the ISC represents the Cl− current (ICl) as Cl− moves down its concentration gradient through the CFTR channels in the apical plasma membrane.

To investigate the activity of basolateral Na+–K+-ATPase activity in isolation, the apical membrane was permeabilized by addition of 10 μM amphotericin B. Na+–K+-ATPase activity was examined in monolayers bathed with medium in which NaCl was replaced by N-methyl-D-glutamine chloride, such that the final bath Na+ concentration was 25 mM on both sides of the monolayers. Under short-circuit conditions, the resulting current is due to the transport of Na+ across the basolateral membrane by the Na+–K+-ATPase (INa).

To investigate the activity of the basolateral K+ conductance in isolation, the apical membrane was permeabilized by addition of 10 μM amphotericin B in the presence of an apical to basolateral K+ gradient. Ouabain (100 μM) was added to the basolateral bath to inhibit Na+–K+-ATPase. The resulting ISC is due to the movement of K+ through channels in the basolateral membrane (IK). The use of antibiotic-based ionophores to selectively permeabilized epithelial membranes is a well-established electrophysiological protocol since the 1980s to gain an insight into ion conductive properties at the opposite unpermeabilized membrane. Antibiotic ionophores used for transport studies are permselective for ions of similar size with the exception of valinomycin for K+. The establishment of large transepithelial (transmembrane) ionic gradients for the ion under study and the use of selective channel blockers aid in extracting the conductive properties of the particular rheogenic ion transport pathway as was done in this study.

A small aliquot of Krebs solution containing single T84 cells was transferred into a 1-ml superfusion chamber mounted on the stage of an inverted microscope (Nikon Diaphot). Patch pipettes were prepared from capillary glass (GC150 F-10, Harvard Apparatus Ltd., Edenbridge, UK) using a programmable horizontal puller (DMZ-Universal Puller, Zeitz-Instruments GmbH, Munich, Germany) and had a resistance of 3–6 Ω when filled with the pipette solution. The reference electrode was an Ag–AgCl wire in direct contact with the superfusion bath. Patch-clamp apparatus consisted of a CV-203BU headstage (Axon Instruments Inc., Union City, CA, USA) connected to an Axopatch 200B series amplifier. Experiments were performed using the whole-cell patch-clamp configuration and recorded membrane currents were filtered at 1 kHz and digitized at 5 kHz. Membrane voltage was clamped from −100 to +100 mV with ramps of 20 mV from an initial holding potential of −50 mV. The protocols for patch-clamp and data analysis were established using pClamp 9.2 software (Axon Instruments Inc.) running on a PC, and data were stored for subsequent analysis. For patch-clamp measurements, the standard bath solution contained (in mM): NaCl 140, KCl 5.4, MgCl2 1, CaCl2 1.25, glucose 12.2, and HEPES 10, buffered at pH 7.4 with NaOH. The patch pipette solution contained (in mM): K-gluconate 95, KCl 30, Na2HPO4 4.8, KH2PO4 1.2, EGTA 1, Ca-gluconate 0.73, MgCl2 1, Na2ATP 3, glucose 5 (pH 7.2). Drug actions were measured only after steady-state conditions were reached. All patch-clamp experiments were performed at 37°C.

T84 cells were serum-starved for 24 h prior to treatment. Drugs were added to the basolateral side of the cell monolayers for the required time. After treatment cells were lysed and subjected to standard 10% SDS-PAGE and Western blotting as previously described (Dilly et al., 2004). Immunoblots were developed using specific phospho-antibodies against human PKCα, PKCδ, p42/p44 MAPK, and p38 MAPK. Immunoprecipitation assays for KCNQ1 were carried out as previously described (Dilly et al., 2004).

PKA activity was detected using the PepTag® assay for non-radioactive detection of cAMP-dependent protein kinase. The kit was used according to manufacturer’s instructions using 30 μg of protein in each reaction http://www.promega.com/resources/protocols/technical-bulletins/0/peptag-assay-for-nonradioactive-detection-of-pkc-or-campdependent-protein-kinase-protocol/. T84 cells were lysed by hypotonic shock on ice for 45 min (lysis buffer: 20 mM tris, pH 7.4, 0.5% non-ident P-40, 250 mM NaCl, 3 mM EDTA, 3 mM EGTA, leupeptin 1 μg/μl, 500 mM dithiothreitol, 5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, complete mini EDTA-free protease inhibitor mixture tablets (1 tablet/7 ml of lysis buffer; Roche Applied Science) and phosphatase inhibitors.

Densitometric analysis was performed using Genetools software (Syngene, Cambridge, UK). Statistical analysis of the data was obtained using paired t-test for analysis between two groups. ANOVA and Tukeys post hoc test for multiple analyses. P-values of 0.05 and less were considered to be significant. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM unless specifically stated to be from a representative experiment.

Phospho-PKCd/θ (Ser643/676), p44/p42 MAPK, phospho-p42/p44 MAPK (Thr202/Tyr204), and phospho-p38 MAPK (Thr180/Tyr182) antibodies were from Cell Signaling Technologies (Hertfordshire, UK). PKCα and PKAcI antibodies were from BD Transduction Antibodies (NJ, USA). Phospho-PKCα (Ser657) antibody was from Upstate (Dublin, Ireland). KCNQ1 antibody was from Santa Cruz (CA, USA). Chromanol 293B was obtained from Tocris (Avonmouth, UK). Rottlerin, clotrimazole, SB202190, and HBDDE were purchased from Calbiochem (Nottingham, UK). (3R,4S)-(+)-N-[3-hydroxy-2,2-dimethyl-6-(4,4,4-trifluorobutoxy)chroman-4-yl]-N-methylethanesulfonami de (HMR-1556) was kindly provided by Dr. Uwe Gerlach (Aventis Pharma Deutschland, Frankfurt-am-Main, Germany). All other chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Dublin, Ireland). All drugs were dissolved in DMSO or water as stock solutions and diluted appropriately. The final DMSO concentration was less than 0.1%.

Short-circuit current measurements across T84 monolayers under basal conditions revealed a small ISC reflecting a low level of Cl− secretion. When the epithelium was treated with forskolin (10 μM), the ISC rapidly increased from 4 ± 2 to 48 ± 6 μA·cm−2 and remained significantly elevated for over 30 min. Berberine when added to the basolateral solution at the peak of the forskolin response decreased the ISC (control 46 ± 5 μA·cm−2, berberine 5 ± 3 μA·cm−2; n = 8, P < 0.01; Figure 1A). The inhibitory effect of berberine on forskolin-induced Cl− secretion was concentration-dependent between 10 and 300 μM with an IC50 of 80 ± 3 μM (Figure 1B). No significant effect on ISC was observed when berberine was added in the absence of forskolin, however, subsequent treatment with forskolin failed to increase ISC (not shown). In approximately 75% of the experiments berberine-induced a small and transient increase in ISC (Figure 1A). This response was prevented by addition of BaCl2 (2 mM) to the apical bath suggesting berberine also inhibits an apical K+ conductance responsible for K+ secretion (data not shown). Berberine treatment for as long as 2 h did not decrease the transepithelial resistance Rt compared to vehicle controls, suggesting that the effects of berberine, at the concentrations used in this study, were not due to cytotoxicity (Table 1).

Figure 1. Effect of berberine on forskolin-induced Cl− secretion. (A) Representative short-circuit current recording of the effect of berberine (300 μM) on forskolin-stimulated ISC in T84 cell monolayers. Drugs were added at arrow and remained in the bathing solutions throughout the experiment (B) Concentration-response curve for the antisecretory effect of berberine on forskolin-stimulated ISC in T84 cell monolayers. Change in ISC measured 15 min post berberine application at different concentrations. Values are mean ± SEM n = 8 for each point.

Nystatin, added to the basolateral bathing solution of T84 monolayers increased the apical membrane Cl− specific current ICl from 3 ± 1 to 14 ± 2 μA·cm−2 (n = 6), this likely reflects a constitutively active apical membrane Cl− conductance. Subsequent addition of forskolin (10 μM) further increased the ICl to 88 ± 12 μA·cm−2. Treatment of T84 cell monolayers with berberine (300 μM) on either apical or basolateral bath for 15 min had no effect on either basal or forskolin-activated apical membrane ICl (Table 2).

The addition of amphotericin B to the apical bathing solution containing 25 mM Na+ increased the basolateral membrane Na+ specific pump current INa from 3 ± 1 to 16 ± 3 μA·cm−2 (n = 6). Under these conditions, the amphotericin-induced INa was completely inhibited by 100 μM ouabain. When T84 monolayers were treated with berberine (300 μM) for 10 min, the amphotericin-induced INa was not different from that of vehicle controls (Table 2).

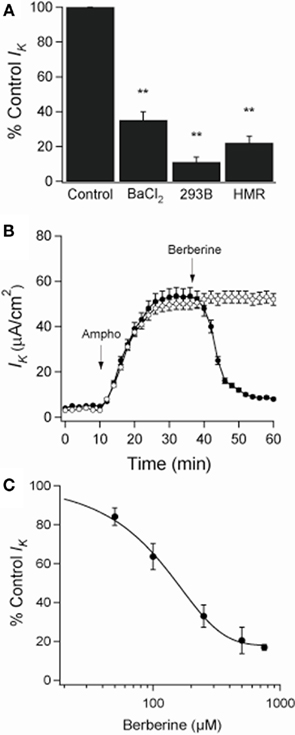

When amphotericin B was added to the apical bath in the presence of an apical to basolateral K+ gradient (80:5 mM) and basolateral ouabain (100 μM), the IK immediately began to increase and reached maximal levels within 15 min (from 5 ± 3 to 53 ± 4 μA·cm−2; n = 6). In these conditions, IK was almost completely inhibited by addition of BaCl2 (2 mM), chromanol 293B (10 μM), or HMR-1556 (500 nM) to the basolateral bath (Figure 2A). When monolayers were treated with berberine (300 μM), IK was rapidly inhibited (53 ± 4 to 9 ± 2 μA·cm−2; P < 0.01, n = 6; Figure 2B) with half-maximal inhibition produced at a concentration of 150 μM (Figure 2C).

Figure 2. Effect of berberine on basolateral K+ current (IK) across apically permeabilized T84 cell monolayers. (A) Effect of KCNQ1 channel inhibitors on IK in T84 cell monolayers. Amphotericin B (10 μM) was added to apical bath after ouabain (100 μM) was added to basolateral bath. BaCl2 (2 mM), chromanol 293B (10 μM), or HMR-1556 (500 nM) were added to the basolateral bath. Values were measured at the point of maximal inhibition of IK by each inhibitor. (B) Short-circuit currents recording of the effect of berberine (300 μM, filled circles) on IK across T84 cells monolayers compared to a vehicle control (DMSO 0.05%, open circles). Drugs were added at arrow and remained in the bathing solutions throughout the experiment. Values are mean ± SEM, **P < 0.01 compared to controls, n = 6 for each group. (C) The concentration dependence of the inhibitory effect of berberine on basolateral membrane K+ current showed a half-maximal inhibition at 150 μM.

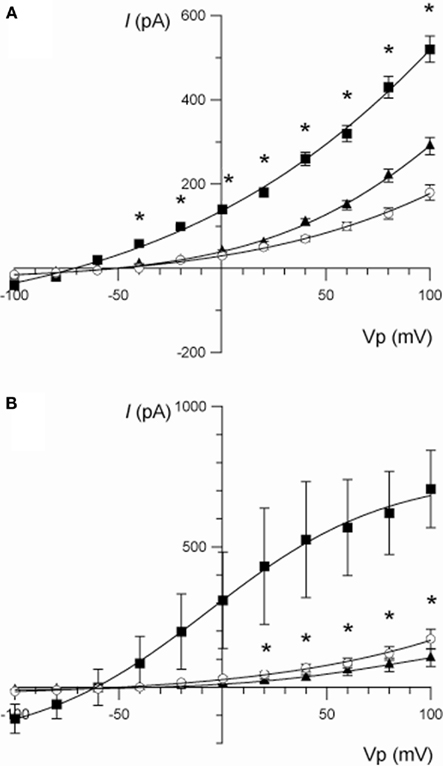

Berberine produced a strong inhibitory effect on forskolin-activated basolateral membrane IK in T84 monolayers (Table 2). The effect of berberine on cAMP-stimulated whole-cell currents in T84 cells was examined (Figure 3A). Forskolin (10 μM) stimulated a mean maximal increase in whole-cell current of 359 ± 71 pA (at Vp = +100 mV; n = 7, P < 0.001). Berberine (100 μM) addition to isolated T84 cells reduced the forskolin-activated current by 68% (corresponding to a reduction of 245 ± 44 pA (at Vp = +100 mV, n = 7, P < 0.01). Consistent with the increase in whole-cell current, forskolin-stimulated an increase in the chord conductance at +100 mV (γ+100) from 1.7 ± 0.3 to 5.2 ± 0.4 nS (P < 0.001, n = 7), which was reduced to 2.8 ± 0.2 nS (P < 0.01, n = 7) following treatment with berberine.

Figure 3. (A) Current/voltage relationships illustrating the effect of berberine (100 μM) on the increase in whole-cell current stimulated by forskolin (10 μM) in T84 cells. Traces are control (○), forskolin (■), and forskolin + berberine (▲). Data are mean ± SEM (*P < 0.01 between the forskolin-stimulated current and berberine, n = 7). (B) Current/voltage relationships illustrating the effect of chromanol 293B (10 μM) on the increase in whole-cell current stimulated by forskolin (10 μM) in T84 cells. Traces are control (○), forskolin (■), and forskolin + chromanol 293B (▲). Data are mean ± SEM (*P < 0.01 between the forskolin-stimulated current and chromanol 293B, n = 3).

The identity of the K+ channels underlying the current stimulated by forskolin and inhibited by berberine was investigated using a variety of K+ channel blockers. Chromanol 293B (10 μM) completely inhibited the forskolin-stimulated current below the level of the control current measured prior to the addition of forskolin (at Vp +100 mV: forskolin = 665 ± 193 pA; forskolin + chromanol 293B = 86 ± 51 pA; P < 0.05, n = 3; Figure 3B). Superfusion with chromanol 293B also reduced the forskolin-induced chord conductance at +100 mV from 7.2 ± 1.4 to 1.2 ± 0.5 nS (P < 0.05, n = 3). Other specific K+ channel inhibitors (of large and small conductance, Ca2+-dependent K+ channels) such as iberiotoxin (BK, 200 nM), apamin (SK, 500 nM), and TRAM-34 (KCNN4, 500 nM) did not affect the forskolin-induced whole-cell K+ currents.

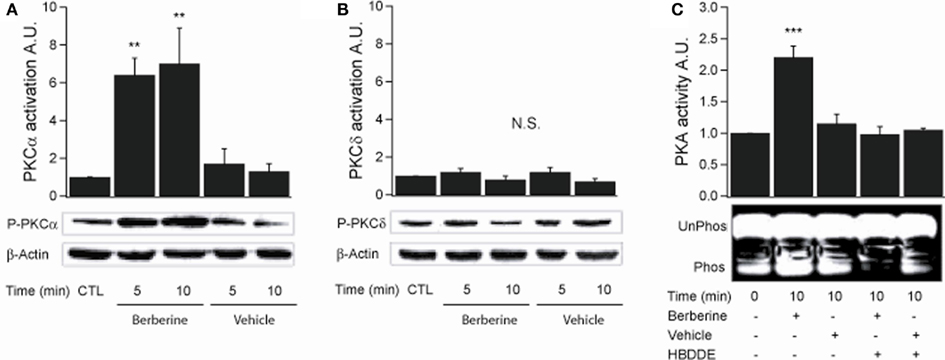

PKCα activation was assessed by probing with a specific antibody to phospho-Ser657. Berberine treatment increased PKCα phosphorylation levels at 5 and 10 min with fold increases of 6.4 ± 0.8 and 7.4 ± 1.8 respectively (n = 3, P < 0.01) compared to vehicle controls (Figure 4A). PKCδ activity was measured using an antibody specific to phospho-Ser643. Berberine treatment had no effect on PKCδ phosphorylation levels (5 min 1.1 ± 0.1; 10 min 0.9 ± 0.1; n = 3) compared to vehicle controls within the time period assayed (Figure 4B). These results show that berberine selectively activates the classical PKCα with no effect on the novel PKCδ. Berberine pre-treatment activated PKA at 10 min with a fold increase of 2.2 ± 0.1 compared to vehicle controls (n = 3, P < 0.001; Figure 4C). Pre-treatment for 10 min with 100 μM HBDDE, a selective PKCα inhibitor at this concentration (Kashiwada et al., 1994), prevented berberine-induced PKA activation (1.0 ± 0.1; n = 3; Figure 4C). This result indicates that PKA is activated in response to berberine and is downstream to PKCα activation.

Figure 4. Berberine effect on PKC isoforms and PKA activity in T84 cells. (A) Representative blot of PKCα phosphorylation levels at Ser657 in cellular extracts from T84 cells after berberine treatment (300 μM) for 5 and 10 min compared to vehicle controls. (B) Representative blot of PKCδ phosphorylation levels at Ser643 in cellular extracts from T84 after berberine treatment (300 μM) cells for 5 and 10 min compared to vehicle controls. Beta-actin was used as an internal control for protein loading. The graphs represent densitometric analysis of PKC blots or PKA activity assays. Values are given as fold changes in PKC phosphorylation (activation) or PKA activity respect to an untreated control. Values are displayed as mean ± SEM (n = 3 for each group, **P < 0.01). (C) Representative blot of PKA phosphorylation levels in cellular extracts from T84 after berberine treatment (300 μM) cells for 10 min compared to vehicle controls and cells pretreated for 10 min with 100 μM HBDDE, a selective PKCα inhibitor.

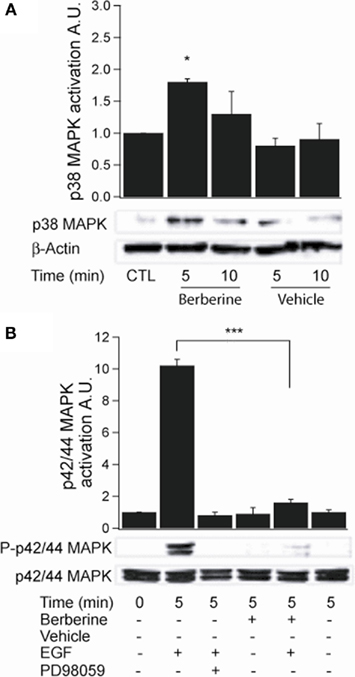

Activation of p38 MAPK was assessed by probing with a specific antibody to phospho-Thr180/Tyr182. Berberine treatment induced p38 MAPK phosphorylation at 5 min with a fold increase of 1.8 ± 0.02 (n = 3, P < 0.05; Figure 5A). The activity of p42/p44 MAPK was measured using an antibody specific to phospho-Thr202/Tyr204. Treatment with berberine had no effect on basal p42/p44 MAPK phosphorylation levels compared to vehicle controls (0.8 ± 0.3, P < 0.04, n = 4) within the time points assayed (Figure 5B). However, pre-treatment of the cells with berberine for 5 min inhibited activation of p42/p44 MAPK by epidermal growth factor (EGF 100 ng·ml−1) with similar potency to that of PD98059 (20 μM), a specific MEK1 inhibitor that prevent receptor-mediated activation of p42/p44 MAPK, (EGF 10.3 ± 1.1; berberine + EGF 1.6 ± 0.7; PD98059 + EGF 0.6 ± 0.1; n = 4, P < 0.01; Figure 5B). These results confirm that berberine selectively activates the p38 MAPK isoform but does not activate p42/p44 MAPK isoforms. Moreover, berberine prevents the EGF-induced activation of p42/p44 MAPK.

Figure 5. Berberine effect on MAPK signaling in T84 cells. (A) Representative blot of p38 MAPK phosphorylation levels at Thr180/Tyr182 in cellular extracts from T84 cells after berberine treatment (300 μM) for 5 and 10 min compared to vehicle controls. (B) Representative blot of p42/p44 MAPK phosphorylation levels at Thr202/Tyr204 in cellular extracts from T84 cells after berberine treatment (300 μM) for 5 and 10 min compared to vehicle controls. T84 cells were treated with EGF (100 ng·ml−1) for 5 min to stimulate p42/p44 MAPK phosphorylation. PD98059 (20 μM) was added 15 min prior EGF-treatment. B-actin was used as an internal control for protein loading. The graphs represent densitometric analysis of blots. Values are given as fold changes in MAPK phosphorylation (activation) respect to an untreated control. Values are displayed as mean ± SEM (n = 3 for each group, *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001).

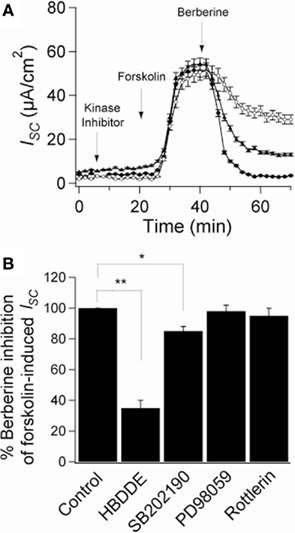

To assess the role of berberine-induced protein kinase activation on its antisecretory effect, T84 monolayers mounted in Ussing chambers were pre-treated with specific kinase inhibitors. Treatment of T84 monolayers with the PKCα inhibitor HBDDE and the specific p38 MAPK inhibitor SB202190 (10 μM) had no effect on basal or forskolin-stimulated ISC. However, HBDDE significantly reduced the inhibitory effect of berberine on ISC by 65 ± 7% (Figure 6A). SB202190 also reduced the effect of berberine but only by 14 ± 5% (Figure 6A). Co-incubation with both inhibitors inhibited the effect of berberine by 82 ± 4% suggesting parallel and synergistic signaling pathways. In contrast, inhibitors of PKCδ (rottlerin 10 μM) and p42/p44 MAPK (PD98059 20 μM) failed to prevent the antisecretory effect of berberine. Figure 6B shows percentage of inhibition of the berberine antisecretory action on forskolin-stimulated ISC by several kinase inhibitor treatments.

Figure 6. Role of protein kinases on the antisecretory effect of berberine. (A) Short-circuit current recordings in T84 cell monolayers of the effect of protein kinases inhibitors on the antisecretory effect of berberine (300 μM). Cells were pre-incubated for 15 min with HBDDE 100 μM (▲), SB202190 10 μM (○), or vehicle DMSO 0.05% (•). (B) Mean ± SEM (n = 6) change in total ISC caused by preincubation with several kinase inhibitors on the antisecretory effect of berberine on forskolin-stimulated ISC. Values are mean ± SEM, n = 6, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 compared to controls.

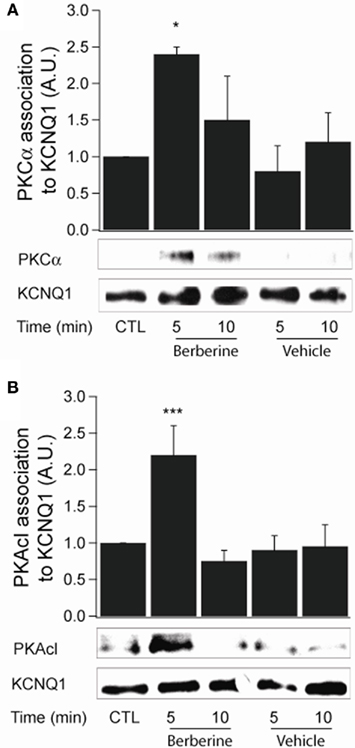

Berberine pre-treatment increased the association of PKCα with the KCNQ1 channel at 5 min with a fold increase of 2.4 ± 0.1 (n = 3, P < 0.05; Figure 7A). Upon activation, PKA catalytic subunits (PKAcI) dissociate from their regulatory subunits and interact with their substrates. Berberine treatment increased PKAcI association with the KCNQ1 channel with a fold increase of 2.2 ± 0.4 (n = 3, P < 0.05; Figure 7B). These experiments demonstrate the association of two kinases, PKCα and PKAcI, with the KCNQ1 channel upon treatment with berberine.

Figure 7. Berberine effect on protein kinase association with KCNQ1 channel. (A) Representative blot of PKCα association with the KCNQ1 channel in response to berberine (300 μM) in T84 cells. (B). Representative blot of PKACI association with the KCNQ1 ion channel in response to berberine (300 μM) in T84 cells. Total KCNQ1 pools were immunoprecipitated from total cellular lysates using an antibody specific to KCNQ1. Associated PKCα and PKAcI were quantified by Western blot analysis. The graphs represent densitometric analysis at specific time points of berberine treatment compared to vehicle controls. Values are given as fold changes in kinase association with KCNQ1 respect to an untreated control. Values are displayed as mean ± SEM (n = 3 for each group, *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001).

The results from this study show that the plant alkaloid berberine inhibits cAMP-dependent Cl− secretion through a kinase-dependent inhibition of the KCNQ1 potassium channel located at the basolateral membrane of human colonic T84 cells. These data identify the ion channel target of berberine to produce inhibition of transepithelial Cl− secretion which we described in early studies in human colonic epithelia (Taylor et al., 1999). Taken together our results are consistent with the hypothesis that blockade of Cl− secretion by berberine in colonic epithelia is secondary to blockade of basolateral membrane K+ channels involved in cAMP-regulated Cl− secretory pathways.

At least two types of K+ channels are present in T84 cells (Barrett and Keely, 2000; Kunzelmann and Mall, 2002). One channel is activated by agents that elevate cytosolic Ca2+ and has been identified as the KCNN4 channel (Warth et al., 1999). A separate K+ channel is activated by cAMP-dependent agonists. Electrophysiological and pharmacological studies have demonstrated this K+ conductance to correspond to the KCNQ1 channel (Schroeder et al., 2000) and this channel has been shown to be rate-limiting for secretion in colon (Preston et al., 2010). In our study, berberine significantly reduced the basolateral membrane K+ conductance. This conductance was stimulated by the cAMP-dependent agonist forskolin and was sensitive to basolateral addition of Ba2+, a non-specific K+ channel blocker, and chromanol 293B, and HMR-1556, two specific KCNQ1 channel blockers, suggesting the main component of the basolateral K+ conductance is composed of current flow through KCNQ1 channels. Similarly, berberine inhibited a cAMP-stimulated and chromanol 293B-sensitive whole-cell conductance, suggesting berberine inhibits KCNQ1 channels. Berberine had no effect on the apical Cl− conductance nor did it affect the basolateral Na+–K+-ATPase pump activity determined as ouabain-sensitive basolateral membrane Na+ current. Therefore, this data suggests berberine exerts its antisecretory effect primarily by inhibiting KCNQ1 channels, thus, decreasing K+ recycling at the basolateral membrane.

Recent studies have examined the effects of berberine on protein kinase activity in several tissues. These reports have shown that the antihyperglycemic activity of berberine is mediated by activation of p38 MAPK and AMP-activated protein kinase (Cheng et al., 2006; Lee et al., 2006). The antiproliferative activity of berberine has been reported to be mediated by inhibition of cyclin-dependent kinases and the MAPK pathway in several tissues (Liang et al., 2006; Mantena et al., 2006). In T84 cells, no effect on basal p42/44 MAPK activity was observed, however, berberine did prevent EGF-induced activation of p42/44 MAPK. Several studies have described the ability of EGF receptor-mediated signaling in regulating Cl− secretion though MAPK (Bertelsen et al., 2004). Therefore, it is possible that berberine may also reduce Cl− secretion by interfering with the EGF signaling. Also, the inhibitory effect of berberine on EGF signaling may be relevant in the antiproliferative action of berberine.

Berberine activated p38 MAPK, PKA, and PKCα. Activation of PKA was observed to be dependent on PKCα activity, and this is the first study to demonstrate berberine-induced activation of PKA and PKCα. Upon activation by berberine, both kinases were shown to transiently associate with the KCNQ1 channel even though both kinases remained activated for a longer period. Several studies have demonstrated regulation of K+ channels by protein kinases. We have previously shown that estrogen causes a female-gender specific inhibition of KCNQ1 channels in rat colonic crypts, producing an antisecretory response which is also dependent on PKA activation and association with the KCNQ1 channel (O’Mahony et al., 2009). Therefore, we investigated the role of berberine-induced kinase activity on the antisecretory effect of berberine. Using specific kinase inhibitors we demonstrated that the antisecretory effect of berberine could be halved by the PKCα inhibitor HBDDE. Pre-treatment with SB202190, a specific inhibitor of p38 MAPK, also significantly decreased the effect of berberine on secretion, although to a much lesser degree. In agreement with these findings, several studies have shown that the phorbol ester PMA inhibits the basolateral K+ conductance of T84 cells and that this effect reduces transepithelial Cl− secretion (Matthews et al., 1993; Reenstra, 1993). The molecular mechanism by which berberine-induced activation of PKCα and p38 MAPK inhibits basolateral KCNQ1 channels in T84 is an important goal of future studies. One possibility to be considered is a change in the phosphorylation state of the channel protein, which is an important determinant of K+ channel activity (Kathöfer et al., 2003; Kurokawa et al., 2003; Li et al., 2004) and which we have shown to mediate the estrogen-induced inhibition of KCNQ1 in rat colonic crypts (O’Mahony et al., 2007).

The present study has shown activation of PKA by berberine. It is well documented that activation of these enzyme lead to an increase in CFTR activity in colonic crypts (Schultheiss and Diener, 1998; Barrett and Keely, 2000; Kunzelmann and Mall, 2002). However, in this study berberine did not affect the apical Cl− current but had an overall inhibitory effect on Cl− secretion. This paradox of activation of PKA without activation of CFTR can be explained if we consider that the cAMP–PKA pathway is tightly regulated at several levels to maintain specificity in the multitude of signal inputs (Tasken and Aandahl, 2004; Cooper, 2005). Ligand-induced changes in cAMP concentration vary in duration, amplitude, and localization into the cell, and cAMP microdomains are shaped by adenylyl cyclases that form cAMP as well as phosphodiesterases that degrade cAMP. Different PKA isozymes with distinct biochemical properties and cell-specific expression contribute to cell and organ specificity. Activated kinase anchoring proteins target PKA to specific substrates and distinct subcellular compartments providing spatial and temporal specificity for mediation of biological effects channeled through the cAMP–PKA pathway (McConnachie et al., 2006). Therefore, the activation of PKA by berberine does not necessarily imply phosphorylation and activation of CFTR located in the apical membrane.

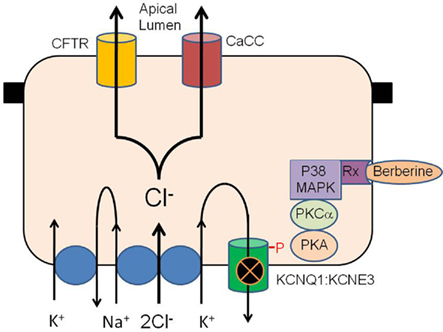

Berberine is freely permeable across human intestinal epithelia and its absorption is significantly increased by P-glycoprotein inhibitors (Pan et al., 2002). It is possible that berberine interacts with a known receptor to effect its antisecretory action. Recently berberine has been shown to affect the activity of sex steroid receptors including the androgen receptor (antagonist) in prostate cancer cells (Li et al., 2011) and the pregnane X receptor (agonist) in HepG2 cells (Yu et al., 2011). Berberine has been shown to enhance the anticancer effect of estrogen receptor antagonists on human breast cancer cells (Liu et al., 2009). The only known receptor-mediated inhibition of KCNQ1 channels in intestine is the estrogen receptor (O’Mahony et al., 2007). 17-B estradiol (E2) inhibits Cl− secretion via PKC and PKA dependent phosphorylation of the KCNQ1:KCNE3 K+ channels in colonic crypts and berberine displays a remarkably similar mechanism of antisecretory action to E2 (both inhibit KCNQ1 channels by protein kinase phosphorylation and neither molecule inhibits CFTR). It is possible that berberine modulates estrogen receptor signaling in intestinal cells to inhibit KCNQ1 channels similar to E2. The chemical structure of berberine is similar to the novel GPR30 receptor agonist G-1 and this orphan estrogen receptor may also be a target of berberine. A hypothetical schema of the antisecretory action of berberine in intestinal epithelium is presented in Figure 8.

Figure 8. Hypothetical schema of the antisecretory action of berberine in intestinal epithelium. Berberine activates p38 MAPK, PKCα and PKA to phosphorylate the KCNQ1:KCNE3 K+ channel causing the channel to become inactive either through closure or removal from the plasma membrane. Inhibition of basolateral K+ channel reduces the electrical driving force for Cl− exit across the apical membrane through CFTR and calcium-activated Cl− channels. The receptor transducing the response to berberine may be the estrogen receptor or GPR30/GPCR as previously described for similar antisecretory and rapid protein kinase responses to estrogen in the intestine.

The ability of berberine to inhibit salt and water secretion from native intestinal tissue, as evidenced by blockade of stimulated ISC in rabbit and rat colon in vitro, raises the distinct possibility that berberine and related compounds may display utility in the clinical treatment of secretory diarrhoeas. High doses of berberine have already been administered orally to humans (Rabbani et al., 1987; Tang and Eisenbrand, 1992), and can be therapeutically safe over the long term. In support of this view, we found that berberine had no detectable effect on the transepithelial resistance of T84 monolayers over a 2-h treatment period. Thus, berberine may inhibit basal and cAMP-induced fluid secretion from intestine without affecting the net transport and absorption of nutrient substrates or absorptive capacity. In fact, berberine has been shown to stimulate Na+ absorption (Tai et al., 1981). Unlike most antidiarrheals, berberine exhibits several pharmacological actions useful to the treatment of secretory diarrhea. Firstly, it reduces the cause of infection via its antimicrobial activity. Secondly, berberine increases stool transit time through the intestine via its antimotility action. Finally, as shown here, berberine decreases basolateral membrane K+ recycling, thus reducing the electrical driving force for whole secretory process in the enterocytes.

Other laboratories have also explored the use of K+ channel blockers to inhibit epithelial Cl− secretion. The antifungal antibiotic, clotrimazole, has been shown to prevent fluid and electrolyte secretion in rabbit and mouse intestine triggered by Ca2+- and cAMP-mediated agonists via specific inhibition of basolateral K+ conductances (Rufo et al., 1997). Furthermore, levamisole (and other phenylimidazothiazoles) inhibits Ca2+- and cAMP-activated Cl− secretion in T84 cell monolayers and isolated human distal colon, apparently by blocking basolateral K+ channels (Mun et al., 1998). Greger and colleagues noted that a group of chromanol compounds selected from agents screened for the ability to block ISC in isolated rabbit colon turned out to be ineffective as Cl− channel blockers, but effective as blockers of K+ channel activity elicited by cAMP-dependent agonists. The most potent of these was chromanol 293B (Lohrmann et al., 1995), which here was shown to block KCNQ1 channels in T84 cells. Chromanol 293B has been described to block CFTR currents when expressed in Xenopus oocytes (Bachmann et al., 2001) but this has not been observed in native epithelia. In our study, the KCNQ1 inhibitors, chromanol 293B, and HMR-1556 were added from the basolateral side without affecting apical Cl− currents. The inhibitory effects of these molecules on transepithelial Cl− secretion is indirect via block of KCNQ1 channels. Like chromanol 293B, berberine also reduced the basolateral K+ current activated by cAMP-dependent agonists. Our finding that berberine has a marked inhibitory effect on basolateral KCNQ1 channel current in T84 cells highlights this component of the intestinal Cl− secretory process as a target for new antidiarrhoeal strategies. Identification of the mechanism of kinase regulation of basolateral K+ channels in colonic epithelia and a better understanding of the signaling processes involved may provide a basis for the development of new antisecretory drugs with greater potency and specificity.

In summary, based on the results of our previous studies in rat colon in vitro and the present studies in T84 cells monolayers, we propose that the effect of berberine on chloride ion secretion in intestine is mediated by a protein kinase-dependent reduction in basolateral KCNQ1 channel activity.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

This work was supported by The Wellcome Trust Biomedical Research Collaboration Grant GR059395FR with Dr. Ko (CUHK), a Higher Education Authority of Ireland PRTLI Grants cycle 1 and 3, and Health Research Board of Ireland. R. Alzamora was recipient of a Wellcome Trust Studentship Prize 06379/Z/01/Z. We thank Wallace C. Y. Yip (Chinese University of Hong Kong) for his technical support.

Bachmann, A., Quast, U., and Russ, U. (2001). Chromanol 293B, a blocker of the slow delayed rectifier K+ current (IKs), inhibits the CFTR Cl- current. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 363, 590–596.

Barrett, K. E., and Keely, S. J. (2000). Chloride secretion by the intestinal epithelium: molecular basis and regulatory aspects. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 62, 535–572.

Bertelsen, L. S., Barrett, K. E., and Keely, S. J. (2004). Gs protein-coupled receptor agonists induce transactivation of the epidermal growth factor receptor in T84 cells: implications for epithelial secretory responses. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 6271–6279.

Cheng, Z., Pang, T., Gu, M., Gao, A. H., Xie, C. M., Li, J. Y., Nan, F. J., and Li, J. (2006). Berberine-stimulated glucose uptake in L6 myotubes involves both AMPK and p38 MAPK. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1760, 1682–1689.

Condliffe, S. B., Doolan, C. M., and Harvey, B. J. (2001). 17β-Oestradiol acutely regulates Cl- secretion in rat distal colonic epithelium. J. Physiol. 530, 47–54.

Cooper, D. M. (2005). Compartmentalization of adenylate cyclase and cAMP signalling. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 33, 1319–1322.

Dharmsathaphorn, K., McRoberts, J. A., Mandel, K. G., Tisdale, L. D., and Masui, H. (1984). A human colonic tumor cell line that maintains vectorial electrolyte transport. Am. J. Physiol. 246(Pt 1), G204–G208.

Dilly, K. W., Kurokawa, J., Terrenoire, C., Reiken, S., Lederer, W. J., Marks, A. R., and Kass, R. S. (2004). Overexpression of grbeta2-adrenergic receptors cAMP-dependent protein kinase phosphorylates and modulates slow delayed rectifier potassium channels expressed in murine heart: evidence for receptor/channel co-localization. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 40778–40787.

DuVall, M. D., Guo, Y., and Matalon, S. (1998). Hydrogen peroxide inhibits cAMP-induced Cl- secretion across colonic epithelial cells. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 275, C1313–C1322.

Field, M. (2003). Intestinal ion transport and the pathophysiology of diarrhea. J. Clin. Invest. 111, 931–943.

Guandalini, S., Fasano, A., Migliavacca, M., Marchesano, G., Ferola, A., and Rubino, A. (1987). Effects of berberine on basal and secretagogue-modified ion transport in the rabbit ileum in vitro. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 6, 953–960.

Heitzmann, D., and Warth, R. (2008). Physiology and pathophysiology of potassium channels in gastrointestinal epithelia. Physiol. Rev. 88, 1119–1182.

Ivanovska, N., and Philipov, S. (1996). Study on the anti-inflammatory actions of Berberis vulgaris root extract, alkaloid fractions and pure alkaloid. Int. J. Immunopharmacol. 18, 553–561.

Iwasa, K., Lee, D. U., Kang, S. I., and Wiegrebe, W. (1998). Antimicrobial activity of 8-alkyl- and 8-phenyl-substituted berberines and their 12-bromo-derivatives. J. Nat. Prod. 61, 1150–1153.

Kashiwada, Y., Huang, L., Ballas, L. M., Jiang, J. B., Janzen, W. P., and Lee, K. H. (1994). New hexahydroxybiphenyl derivatives as inhibitors of protein kinase C. J. Med. Chem. 37, 195–200.

Kathöfer, S., Rockl, K., Zhang, W., Thomas, D., Katus, H., Kiehn, J., Kreye, V., Schoels, W., and Karle, C. (2003). Human grbeta3-adrenoreceptors couple to KVLQT1/MinK potassium channel in Xenopus oocytes via protein kinase C phosphorylation of the KVLQT1 protein. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 368, 119–126.

Kunzelmann, K., and Mall, M. (2002). Electrolyte transport in the mammalian colon: mechanisms and implications for disease. Physiol. Rev. 82, 245–289.

Kurokawa, J., Chen, L., and Kass, R. S. (2003). Requirement of subunit expression for cAMP-mediated regulation of a heart potassium channel. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 2122–2127.

Lau, C. W., Yao, X. O., Ko, W. H., and Huang, Y. (2001). Cardiovascular actions of berberine. Cardiovasc. Drug Rev. 19, 234–244.

Lee, Y. S., Kim, W. S., Kim, K. H., Yoon, M. J., Cho, H. J., Shen, Y., Ye, J. M., Lee, C. H., Oh, W. K., Kim, C. T., Hohnen-Behrens, C., Gosby, A., Kraegen, E. W., James, D. E., and Kim, J. B. (2006). Berberine, a natural plant product, activates AMP-activated protein kinase with beneficial metabolic effects in diabetic and insulin-resistant states. Diabetes 55, 2256–2264.

Li, J., Cao, B., Liu, X., Fu, X., Xiong, Z., Chen, L., Sartor, O., Dong, Y., and Zhang, H. (2011). Berberine suppresses androgen receptor signaling in prostate cancer. Mol. Cancer Ther.. [Epub ahead of print].

Li, Y., Langlais, P., Gamper, N., Liu, F., and Shapiro, M. S. (2004). Dual phosphorylations underlie modulation of unitary KCNQ K+ channels by Src tyrosine kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 45399–45407.

Liang, K. W., Ting, C. T., Yin, S. C., Chen, Y. T., Lin, S. J., Liao, J. K., and Hsu, S. L. (2006). Berberine suppresses MEK/ERK-dependent Egr-1 signaling pathway and inhibits vascular smooth muscle cell regrowth after in vitro mechanical injury. Biochem. Pharmacol. 71, 806–817.

Liu, J., He, C., Zhou, K., Wang, J., and Kang, J. X. (2009). Coptis extracts enhance the anticancer effect of estrogen receptor antagonists on human breast cancer cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 378, 174–178.

Lohrmann, E., Burhoff, I., Nitschke, R. B., Lang, H. J., Mania, D., Englert, H. C., Hropot, M., Warth, R., Rohm, W., Bleich, M., and Greger, R. (1995). A new class of inhibitors of cAMP-mediated Cl- secretion in rabbit colon acting by the reduction of cAMP-activated K+ conductance. Pflügers Arch. 429, 517–530.

Ma, T., Thiagarajah, J. R., Yang, H., Sonawane, N. D., Folli, C., Galietta, L. J., and Verkman, A. S. (2002). Thiazolidinone CFTR inhibitor identified by high-throughput screening blocks cholera toxin–induced intestinal fluid secretion. J. Clin. Invest. 110, 1651–1658.

Mantena, S. K., Sharma, S. D., and Katiyar, S. K. (2006). Berberine inhibits growth, induces G1 arrest and apoptosis in human epidermoid carcinoma A431 cells by regulating Cdki-Cdk-cyclin cascade, disruption of mitochondrial membrane potential and cleavage of caspase 3 and PARP. Carcinogenesis 27, 2018–2027.

Matthews, J. B., Awtrey, C. S., Hecht, G., Tally, K. J., Thompson, R. S., and Madara, J. L. (1993). Phorbol ester sequentially downregulates cAMP-regulated basolateral and apical Cl- transport pathways in T84 cells. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 265, C1109–C1117.

McConnachie, G., Langeberg, L. K., and Scott, J. D. (2006). AKAP signaling complexes: getting to the heart of the matter. Trends Mol. Med. 12, 317–323.

Mun, E. C., Mayol, J. M., Reegler, M., O’Brien, T. C., Farokhzad, O. C., Song, J. C., Pothoulakis, C., Hrnjez, B. J., and Matthews, J. B. (1998). Levamisole inhibits intestinal Cl- secretion via basolateral K+ channel blockade. Gastroenterology 114, 1257–1267.

O’Mahony, F., Alzamora, R., Betts, V., LaPaix, F., Carter, D., Irnaten, M., and Harvey, B. J. (2007). Female gender-specific inhibition of KCNQ1 channels and chloride secretion by 17-beta estradiol in rat distal colonic crypts. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 24563–24573.

O’Mahony, F., Alzamora, R., Chung, H. L., Thomas, W., and Harvey, B. J. (2009). Genomic priming of the antisecretory response to estrogen in rat distal colon throughout the estrous cycle. Mol. Endocrinol. 23, 1885–1899.

Pan, G. Y., Wang, G. J., Liu, X. D., Fawcett, J. P., and Xie, Y. Y. (2002). The involvement of P-glycoprotein in berberine absorption. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 91, 193–197.

Preston, P., Wartosch, L., Günzel, D., Fromm, M., Kongsuphol, P., Ousingsawat, J., Kunzelmann, K., Barhanin, J., Warth, R., and Jentsch, T. J. (2010). Disruption of the K+ channel beta-subunit KCNE3 reveals an important role in intestinal and tracheal Cl- transport. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 7165–7175.

Rabbani, G. H., Butler, T., Knight, J., Sanyal, S. C., and Alam, K. (1987). Randomized controlled trial of berberine sulfate therapy for diarrhea due to enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli and Vibrio cholerae. J. Infect. Dis. 155, 979–984.

Reenstra, W. W. (1993). Inhibition of cAMP- and Ca2+-dependent Cl- secretion by phorbol esters: inhibition of basolateral K+ channels. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 264, C161–C168.

Robbins, J. (2001). KCNQ potassium channels: physiology, pathophysiology, and pharmacology. Pharmacol. Ther. 90, 1–19.

Rufo, P. A., Merlin, D., Riegler, M., Ferguson-Maltzman, M. H., Dickinson, B. L., Brugnara, C., Alper, S. L., and Lencer, W. I. (1997). The antifungal antibiotic, clotrimazole, inhibits chloride secretion by human intestinal T84 cells via blockade of distinct basolateral K+ conductances. Demonstration of efficacy in intact rabbit colon and an in vivo mouse model of cholera. J. Clin. Invest. 100, 3111–3120.

Schroeder, B. C., Waldegger, S., Fehr, S., Bleich, M., Warth, R., Greger, R., and Jentsch, T. J. (2000). A constitutively open potassium channel formed by KCNQ1 and KCNE3. Nature 403, 196–199.

Schultheiss, D., and Diener, M. (1998). K+ and Cl- conductances in the distal colon of the rat. Gen. Pharmacol. 31, 337–342.

Tai, Y. H., Feser, J. F., Marnane, W. G., and Desjeux, J. F. (1981). Antisecretory effects of berberine in rat ileum. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 241, G253–G258.

Tang, W., and Eisenbrand, G. (1992). Chinese Drugs of Plant Origin: Chemistry, Pharmacology, and Use in Traditional and Modern Medicine. Berlin: Springer-Verlag Press, 361–371.

Tasken, K., and Aandahl, E. M. (2004). Localized effects of cAMP mediated by distinct routes of protein kinase A. Physiol. Rev. 84, 137–167.

Taylor, C. E., and Greenough, W. B. (1989). Control of diarrheal diseases. Annu. Rev. Public Health 10, 221–244.

Taylor, C. T., and Baird, A. W. (1995). Berberine inhibition of electrogenic ion transport in rat colon. Br. J. Pharmacol. 116, 2667–2672.

Taylor, C. T., Winter, D. C., Skelly, M. M., O’Donoghue, D. P., O’Sullivan, G. C., Harvey, B. J., and Baird, A. W. (1999). Berberine inhibits ion transport in human colonic epithelia. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 368, 111–118.

Warth, R., Hamm, K., Bleich, M., Kunzelmann, K., von Hahn, T., Schreiber, R., Ullrich, E., Mengel, M., Trautmann, N., Kindle, P., Schwab, A., and Greger, R. (1999). Molecular and functional characterization of the small Ca2+-regulated K+ channel (rSK4) of colonic crypts. Pflügers Arch. 438, 437–444.

Yamamoto, K., Takase, H., Abe, K., Sato, Y., and Suzuki, A. (1993). Pharmacological studies on anti-diarrhoeal effects of a preparation containing berberine and geranii herba. Nippon Yakurigaku Zasshi 101, 169–175.

Keywords: berberine, KCNQ1 K+ channels, CFTR, chloride secretion, colon ion transport, T84 cells

Citation: Alzamora R, O’Mahony F, Ko W-H, Yip TW-N, Carter D, Irnaten M and Harvey BJ (2011) Berberine reduces cAMP-induced chloride secretion in T84 human colonic carcinoma cells through inhibition of basolateral KCNQ1 channels. Front. Physio. 2:33. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2011.00033

Received: 13 May 2011; Paper pending published: 04 June 2011;

Accepted: 18 June 2011; Published online: 30 June 2011.

Edited by:

Ali Mobasheri, The University of Nottingham, UKReviewed by:

Richard Barrett-Jolley, University of Liverpool, UKCopyright: © 2011 Alzamora, O’Mahony, Ko, Yip, Carter, Irnaten and Harvey. This is an open-access article subject to a non-exclusive license between the authors and Frontiers Media SA, which permits use, distribution and reproduction in other forums, provided the original authors and source are credited and other Frontiers conditions are complied with.

*Correspondence: Brian Joseph Harvey, Department of Molecular Medicine, Education and Research Centre, Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland, Beaumont Hospital PO Box 9063, Dublin 9, Ireland. e-mail:YmpwaGFydmV5QHJjc2kuaWU=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.