1 Introduction

Nuclear physics has entered a new exciting era with next-generation rare isotope beam facilities like the Facility for Rare Isotope Beams (FRIB) coming online and enabling experiments with atomic nuclei, which were previously inaccessible, to study their structure and a multitude of reactions with them. These experiments are expected to inform, e.g., -process nucleosynthesis and to test fundamental symmetries by using nuclei as laboratories enhancing signals to investigate beyond standard model physics. In this new era, stable-beam facilities continue to play an important role by allowing detailed, high-statistics experiments with modern spectroscopy setups and provide complementary information for rare-isotope studies by, e.g., studying structure phenomena of stable nuclei close to the particle-emission thresholds and by investigating details of different nuclear reactions, thus, testing reaction theory. Modern coincidence experiments, that combine multiple detector systems, can also address open questions in stable nuclei providing important pieces to solving the nuclear many-body problem and quality data to guide the development of ab-initio-type theories for the spectroscopy of atomic nuclei. Since its foundation in the 1960s, the John D. Fox Superconducting Linear Accelerator Laboratory at Florida State University [1] has continued to pursue research at the forefront of nuclear science. New experimental setups, which were recently commissioned at the Fox Laboratory and which will be presented in this article, enable detailed studies of atomic nuclei close to the valley of stability through modern spectroscopy experiments that detect particles and rays in coincidence.

1.1 History of the John D. Fox laboratory

The Florida State University (FSU) Accelerator Laboratory began operation in 1960 following the installation of an EN Tandem Van de Graaf accelerator. It was the second of its type in the United States. Since its dedication in March 1960, the FSU Accelerator Laboratory has been recognized for several scientific and technical achievements. Examples of the early days of operation are the first useful acceleration of negatively-charged helium ions at FSU in 1961 [2] and the experimental identification of isobaric analogue resonances in proton-induced reactions in 1963 [3].

The laboratory entered its second development stage in 1970 with the installation of a Super-FN Tandem Van de Graaff accelerator. As a third major stage of evolution, a superconducting linear post-accelerator based on atlas technology was funded by the U.S. National Science Foundation in the mid-1980s [4], with the first experiment on the completed facility run in 1987 [5, 6]. The Super-FN Tandem Van de Graaff and superconducting linear post-accelerator are still being used at the FSU Accelerator Laboratory today. In combination with two SNICS sources and an RF-discharge source, they provide a variety of accelerated beams, ranging from protons to accelerated titanium ions, for experiments relevant for nuclear science. In March 2007, FSU’s Superconducting Linear Accelerator Laboratory was named for John D. Fox, a longtime FSU faculty member who was instrumental in its development.

Today, the local group operates in addition to the two accelerators a number of experimental end stations allowing experiments at the forefront of low-energy nuclear physics. The present layout of the FSU laboratory is shown in Figure 1. Experiments with light radioactive ion beams, which are produced in-flight, can be performed at the resolut facility [7]. The Array for Nuclear Astrophysics Studies with Exotic Nuclei, anasen [8], and the resoneut detector setup for resonance spectroscopy after reactions [9] are major detector setups available for experiments at the resolut beamline. The laboratory further added to its experimental capabilities by introducing the catrina neutron detector array [31], the MUSIC-type active target detector encore [10], and by installing the Super-Enge Split-Pole Spectrograph (se-sps) in collaboration with Louisiana State University, including its first new ancillary detector systems sabre [11] and cebra [12] for coincidence experiments. Recently, the FSU group also installed the high-resolution -ray array clarion2 and the trinity particle detector [13] in collaboration with Oak Ridge National Laboratory. This array consists of up to 16 Compton-suppressed, Clover-type High-Purity Germanium (HPGe) detectors.

2 Featured experimental setups and capabilities

2.1 The Super-Enge Split-Pole Spectrograph (SE-SPS)

The Super-Enge Split-Pole Spectrograph (SE-SPS) has been moved to FSU after the Wright Nuclear Structure Laboratory (WNSL) at Yale University ceased operation. Like any spectrograph of the split-pole design [14], the SE-SPS consists of two pole sections used to momentum-analyze reaction products and focus them at the magnetic focal plane to identify nuclear reactions and excited states. The split-pole design allows to accomplish approximate transverse focusing as well as to maintain second-order corrections in the polar angle and azimuthal angle , i.e., and , over the entire horizontal range [14]. H. Enge specifically designed the SE-SPS spectrograph as a large-acceptance modification to the traditional split-pole design for the WNSL. The increase in solid angle from 2.8 to 12.8 msr was achieved by doubling the pole-gap, making the SE-SPS well-suited for coincidence experiments. At FSU, the SE-SPS was commissioned in 2018. The design resolution of 20 keV was achieved in June 2019 during a12C13C experiment with a thin natural Carbon target after improvements to the accelerator optics, the dedicated beamline by adding a focusing quadrupole magnet in front of the scattering chamber, and the new CAEN digital data acquisition [15]. Figure 2 shows the SE-SPS in target room 2 of the FSU John D. Fox Laboratory.

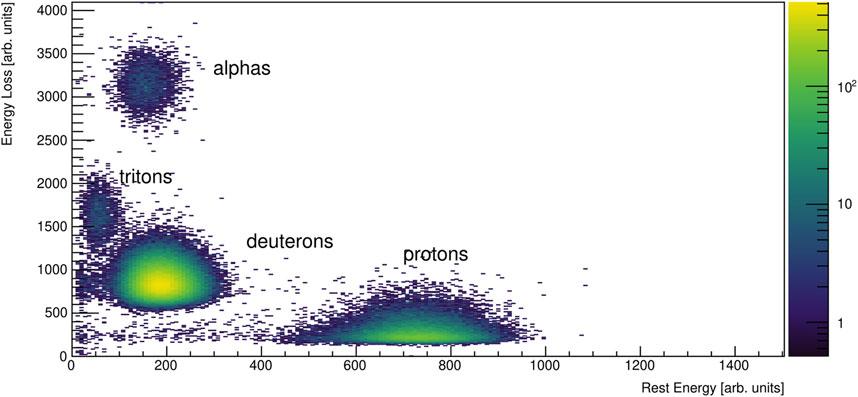

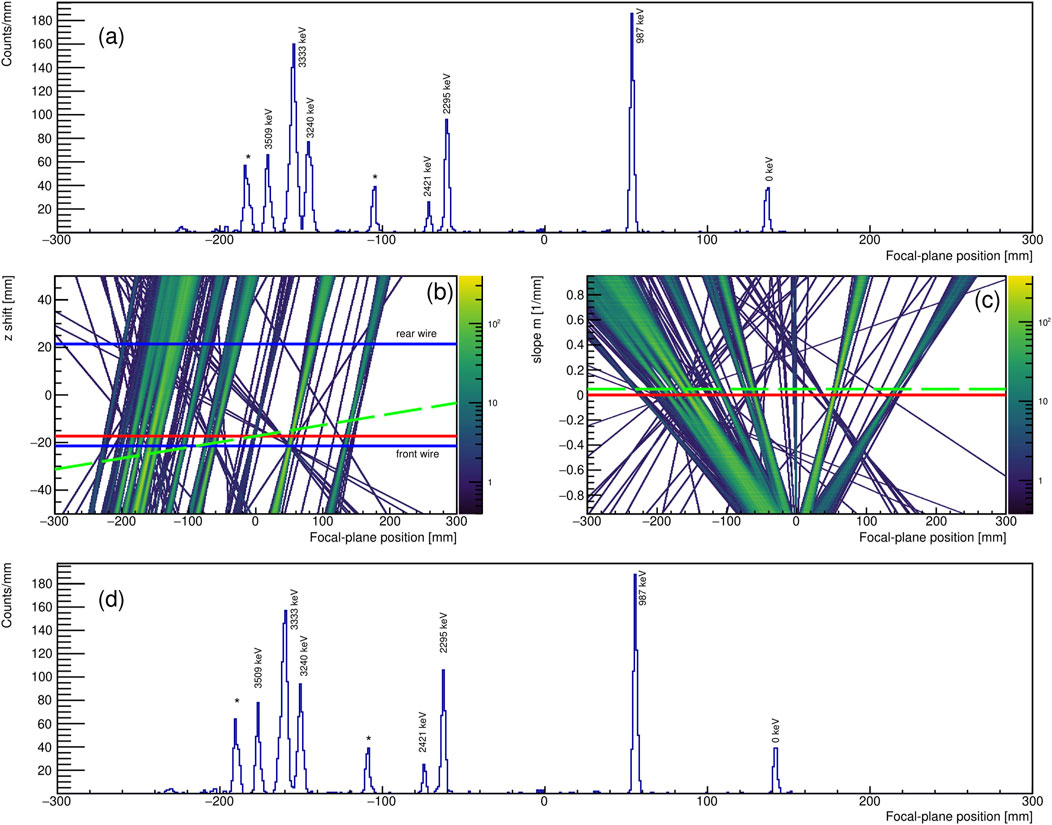

In singles experiments, i.e., stand-alone mode, the SE-SPS with its current light-ion with its current light-ion focal plane detection system [16] (see Figure 2) can be used to study the population of excited states in light-ion induced reactions, determine (differential) cross sections and measure the corresponding angular distributions. Currently, laboratory scattering angles of up to can be covered. The focal-plane detector consists of a position-sensitive proportional counter with two anode wires (see Figure 2), separated by about 4.3 cm, to measure position, angle, and energy loss, and a large plastic scintillator to determine the rest energy of the residual particles passing through the detector. The focal-plane detector has an active length of about 60 cm. A sample particle identification plot with the energy loss measured by the front-anode wire and the rest energy measured by the scintillator is shown in Figure 3. Unambiguous particle identification is achieved. Under favorable conditions, the detector can be operated at rates as high as two kilocounts/s (kcps). A sample position spectrum measured with the delay lines of the SE-SPS focal plane detector is also shown in Figure 4. As the resolution depends on the solid angle, target thickness and beam-spot size, it may vary from experiment to experiment. See also comments in [14, 17]. In standard operation and with a global kinematic correction, i.e., assuming a vertical shift of the real focal plane with respect to the two position-sensitive sections of the detector, a full width at half maximum of 30–70 keV has been routinely achieved. This corresponds to a position resolution of about 2 mm. This resolution can be improved further with position-dependent offline corrections. An example for such a correction, taking into account the position dependence of the shift for obtaining the true focal-plane position relative to the two anode wires and assuming that it depends linearly on the focal-plane position , has been added to Figure 4. A slope of would correspond to the standard correction of calculating the real focal plane from a “vertical” shift relative to the two focal-plane wires and is shown with a red line in Figures 4B, C. As can be seen in Figures 4B, C, there is a region with , where the “tracks” mostly corresponding to excited states of 48Ti populated in get narrower after the correction, thus improving the position resolution along the focal plane. The improved focal-plane spectrum is shown in Figure 4D. The magnetic field is 11.2 kG and the solid-angle acceptance was kept at 4.6 msr for this experiment. The necessity of kinematic corrections for magnetic spectrographs and how to calculate the vertical shift for, e.g., the split-pole design were also discussed in [14].

Angular distributions provide direct information on the angular momentum, , transfer and, for one-nucleon transfer reactions, information on the involved single-particle levels. For the set of experiments performed with the SE-SPS up to date, very good to excellent agreement has been observed between the experimental data and the reaction calculations using the conventional Distorted Wave Born Approximation (DWBA) and the adiabatic distorted wave (ADW) method with input from global optical model potentials. Further details were discussed in [18–23]. Some examples for are shown in Figure 7 and will be discussed further in the next section in the context of particle- coincidence experiments with the SE-SPS and CeBrA.

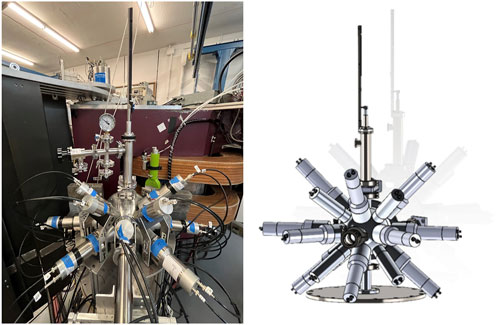

2.1.1 The CeBrA demonstrator for particle- coincidence experiments at the SE-SPS

The Cerium Bromide Array (CeBrA) demonstrator for particle- coincidence experiments at the SE-SPS has recently been commissioned at the John D. Fox Laboratory [12]. It has been extended since with four inch detectors on temporary loan from Mississippi State University (see Figure 5). This extended demonstrator has a combined full energy peak (FEP) efficiency of about 3.5 at 1.3 MeV. For comparison, the five-detector demonstrator had an FEP efficiency of about 1.5 at 1.3 MeV [12]. The comparison underscores the significant gain when adding larger volume detectors. Over the next years, a 14-detector array will be built in collaboration with Ursinus College and Ohio University through funding from the U.S. National Science Foundation, combining the existing detectors (four inch and one inch) of the demonstrator with five additional inch and four inch detectors.

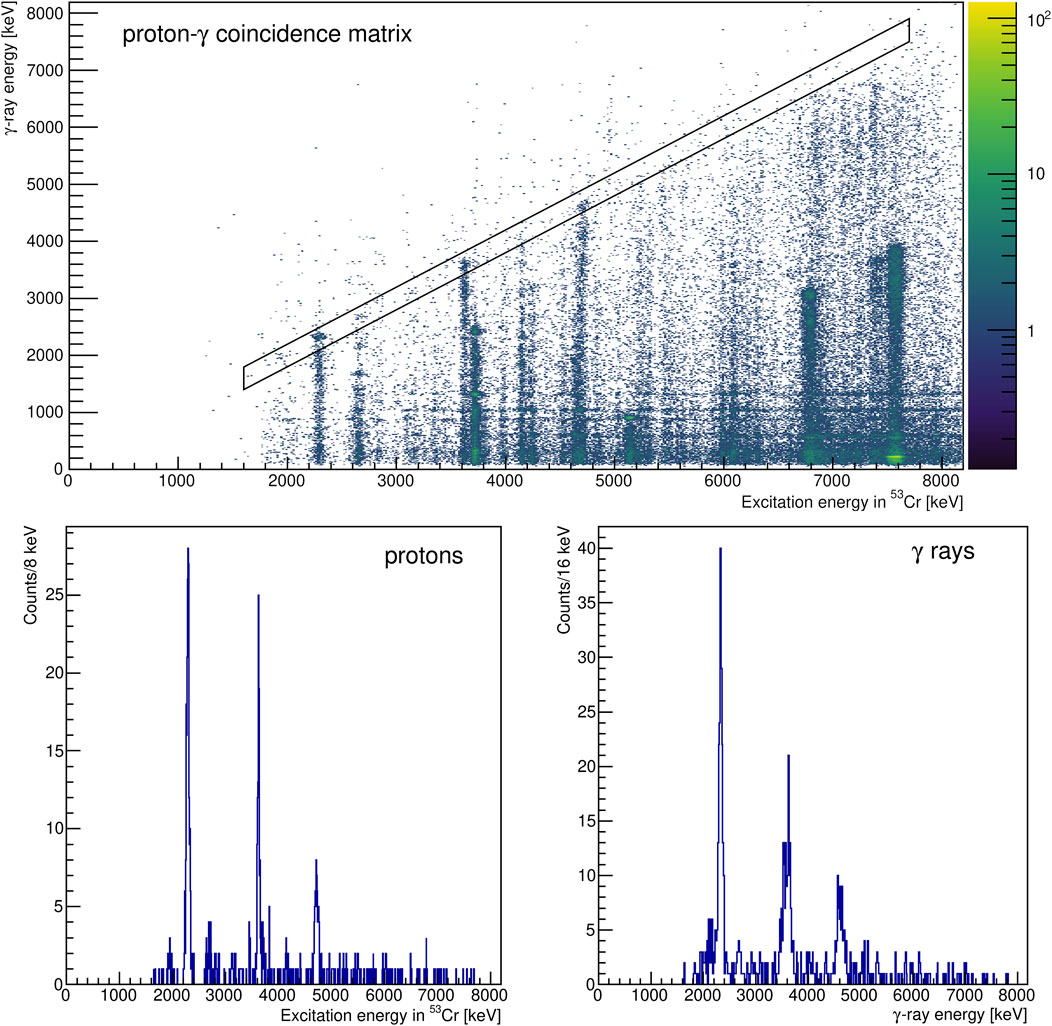

An example for a particle- coincidence matrix, measured in with the five-detector demonstrator, is shown in Figure 6. Using diagonal gates, decays leading to specific (excited) states can be selected. In Figure 6, decays to the ground state of 53Cr were selected. Three states stand out as they are also strongly populated in [21]. They are the excited states at 2,321 keV, 3,617 keV, and 4,690 keV. The decay of the 4690-keV state is, to our knowledge, observed for the first time. No information on its decay is adopted [24]. The ray at MeV indicates that, different from previous conclusions [21], both the 2657-keV and 2670-keV states might have been populated in . The ground-state branch of the , 2657-keV state is too small to explain the excess of counts. More details will be discussed in a forthcoming publication [25], which will also highlight the significant value added from performing complementary singles and coincidence experiments with the SE-SPS. A feature, which can be immediately appreciated from Figure 6, is that the energy resolution of the SE-SPS barely changes over the length of the focal plane, while the energy resolution shows the expected dependence on -ray energy [12]. Using the additional -ray information and projecting onto the excitation-energy axis will allow us to distinguish close-lying states, which might be too close in energy to do so in SE-SPS singles experiments or where particle spectroscopy alone does not provide conclusive results. For this, differences in -decay behavior can be used. As an example, see the very different -decay behavior of the 3617-keV, and the 3707-keV, states of 53Cr in Figure 6. For the 3,617-keV state, the 3,617-keV ground-state transition is the strongest, while it is the 2,417-keV transition for the 3,707-keV state. Another example, using different diagonal gates for the reaction and, thus, selecting decays leading to different final states with different as “spin filter”, was featured in Ref. [12].

The coincidently detected rays also provide access to important complementary information such as -decay branching ratios and particle- angular correlations for spin-parity assignments, as well as the possibility to determine nuclear level lifetimes via fast-timing techniques and excluding feeding due to gates on the excitation energy [12]. For the latter, the smaller detectors are better suited because of their better intrinsic timing resolution as also discussed in Ref. [12]. For dedicated fast-timing measurements, two inch detectors are available at FSU in addition to the four inch detectors. These have an even better timing resolution than the inch detectors, however, at the cost of a significantly lower FEP efficiency. A careful analysis of their timing properties and FEP efficiencies is ongoing.

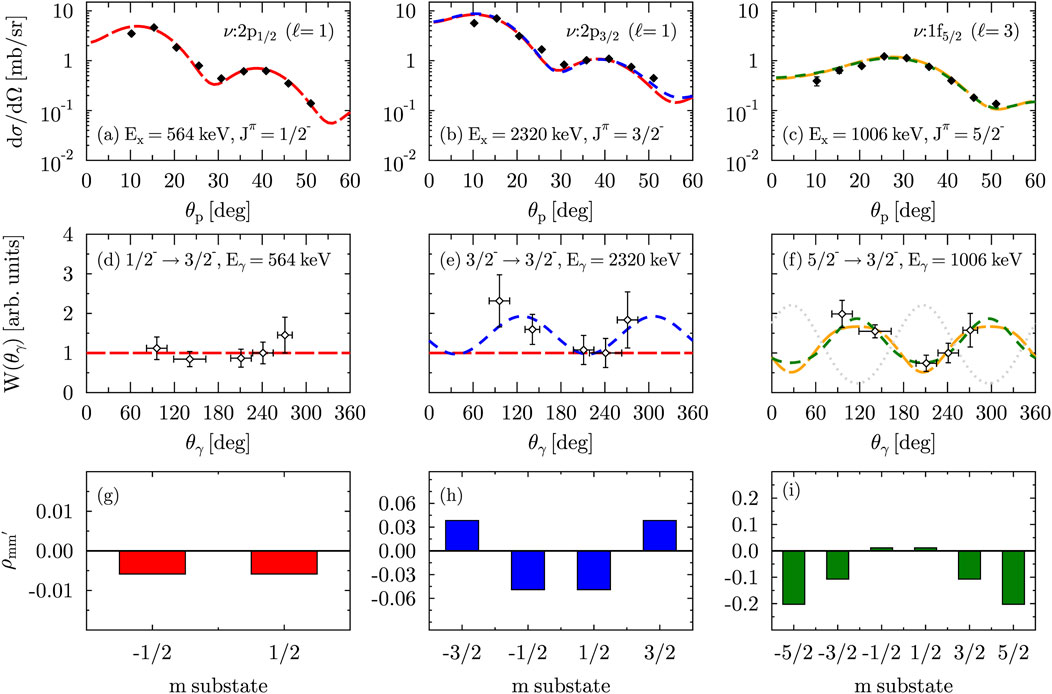

We will briefly highlight some particle- angular correlations measured with the five detector CeBrA demonstrator. Particularly, we will discuss how these can be used to make spin-parity assignments and to determine multipole mixing ratios . Figure 7 shows three proton- angular correlations measured in and with all five detectors placed in a common plane with an azimuthal angle . In addition to the experimental data, predictions from combined ADW calculations with chuck3 [26] yielding scattering amplitudes and angcor [27] calculations using these scattering amplitudes to generate the angular correlations are shown. The associated density matrices, , needed to calculate the proton- angular correlations with the formalism presented in Ref. [28] and which are connected to the scattering amplitudes for the different substates, were added, too. As all the -ray transitions of Figure 7 are primary transitions, the multipole mixing ratio is the only free parameter. It was determined via minimization. Excellent agreement is observed between the experimentally measured and the calculated distributions for the excited states at keV, 1,006 keV, and 2,320 keV of 53Cr. For the 564-keV state, a one-neutron transfer to the neutron orbital was assumed [red, longer dashed line in Figure 7A]. For the 2320-keV state, the neutron was transferred into the orbital (blue, shorter dashed line). For the 1,006-keV state, the neutron was transferred into the orbital (green, shorter dashed line). For the 2,320-keV and 1,006-keV states, transfers to their corresponding spin-orbit partner are also shown in Figure 7. In panels (c) and (f), predictions for a neutron transfer into the orbital are shown with orange, longer dashed lines.

As expected for the 564-keV, ground-state transition, the negligible alignment [see Figure 7G] leads to an isotropic angular distribution. We note that this is true for any value of . For the 2320-keV, and 1,006-keV, ground-state transitions, the -substate population (alignment) [see Figures 7H, I] results in observable angular distributions. In both cases, the multipole mixing ratio indicates that the transition is dominantly of character. A more in depth discussion will be provided in a forthcoming publication [25]. Figures 7D, E show clearly that and states can be distinguished based on their observed proton- angular correlation. singles experiments with an unpolarized deuteron beam cannot discriminate between these states since both are populated via an angular momentum transfer [see Figures 7A, B]. The situation appears more complex for the orbitals, where the predicted proton- angular correlations are not sufficiently different to discriminate between a and transition [see Figure 7F]. For the known 1,006-keV, state, the calculation assuming a neutron transfer into the orbital does provide the slightly better value though. For completeness, we added the proton- angular correlation for the transition calculated with the currently adopted multipole-mixing ratio to Figure 7F. As discussed in [12], the adopted ratio appears to be incorrect. However, different sign conventions for the multipole mixing ratios could also be the origin of the disagreement.

With more detectors, which will be added to the full CeBrA array within the next couple of years, statistics will increase and particle- angular correlation measurements can be performed in planes with varying . Four “rings” will be available in the standard configuration, where three of them have at least four detectors (see Figure 5). The full setup will allow to further test details of different transfer reactions and the predicted alignment. Measuring particle- angular correlations in planes with different could potentially help to better discriminate between spin-orbit partners, like and , too. Another example of how different angular correlations can look for the and spin-orbit partners will be shown in Section. 3.2.

2.2 The CATRiNA neutron detector array

The CATRiNA neutron detector array currently consists of 32 deuterated-benzene () liquid scintillator neutron detectors. There are two sizes of CATRiNA detectors: 16 “small” detectors and 16 “large” detectors. The “small” CATRiNA detectors encapsulate the deuterated scintillating material in a 2″ diameter 2″ deep cylindrical aluminum cell, while the “large” detectors encapsulate the scintillating material in a 4″ diameter 2″ deep cylindrical aluminum cell [30, 31].

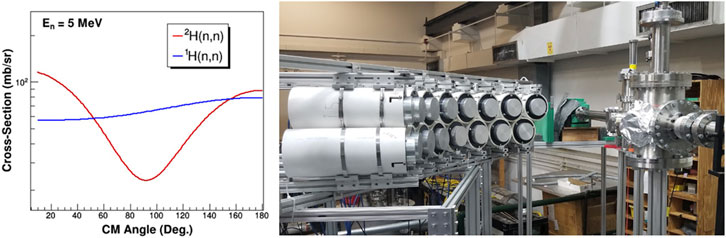

The use of deuterated scintillating material for neutron detection, rather than traditional hydrogen-based scintillating material, is due to unique features produced in the light-output spectrum. Neutrons scattered off the deuterium in the scintillator will produce a characteristic forward recoil peak and low valley in the light-output spectrum. This feature is due to the asymmetry of the cross section for scattering, which peaks at backwards angles and extends across a large range of neutron energies. As an example, Figure 8 shows a DWBA calculation made with the fresco computer program [29] for the elastic scattering cross sections of 5-MeV neutrons off the deuteron 2H and proton 1H as a function of the center-of-mass (CM) angle. The difference between the angular distributions can be clearly seen. The characteristic light-output spectra of deuterated scintillators is then used for the extraction of neutron energies using spectrum-unfolding methods. Determining neutron energies from spectrum unfolding is an alternative to fully relying on time-of-flight (ToF) information for neutron energies. This alternative is particularly beneficial if a compact neutron detector system like CATRiNA is used, which efficiently optimizes solid angle coverage and the size of the detector array for neutron studies. The CATRiNA detectors have equivalent properties of organic scintillators for neutron detection such as large scattering cross section for neutrons with the scintillating material, fast response time, and pulse shape discrimination capabilities that allow separation of neutron and gamma-ray events.

To highlight the capabilities of the CATRiNA neutron detectors, a proton-transfer experiment was conducted on a solid deuterated-polyethylene, , target of 400-g/ thickness and a set of “large” CATRiNA detectors placed in target room #1 of the Fox Laboratory. The FN Tandem accelerator provided deuteron beams with energy MeV. The deuteron beam was bunched to 2-ns width with intervals of 82.5 ns for time-of-flight (ToF) measurements using the accelerator’s radiofrequency (RF) as reference signal. The CATRiNA detectors were placed at 1-m distance from the target. A thick graphite disk was placed 2 m downstream from the target and used as a beam stop to minimize beam-induced background. The graphite beam stop was held inside a 30 cm 30 cm 30 cm borated-polyethylene block, which was surrounded with 5-cm thick lead bricks and thin lead sheets to reduce background from beam-induced neutrons and rays from the beamstop, respectively. The experimental setup is shown in Figure 8. The characterization of the CATRiNA detectors and the description of the unfolding method can be found in Refs. [30, 31]. Neutrons from the interaction of the deuterium beam with the carbon and deuterium in the target were used to compare neutron energies measured with ToF and extracted with the unfolding methods.

In the following, the pulse-shape discrimination (PSD) properties of the CATRiNA detectors have been used to separate neutron and -ray interactions in the detectors. For the ToF measurements, the time difference was measured between the prompt-gamma signal and the neutron peaks coming from the interaction of the beam with the target. The accelerator’s RF signal was used as a “stop” signal while the “start” signal was provided by an “or” of any events registered in the CATRiNA detectors. The energy of the neutrons was then calculated using non-relativistic kinematics taking into account the target to detector distance and the measured time of flight.

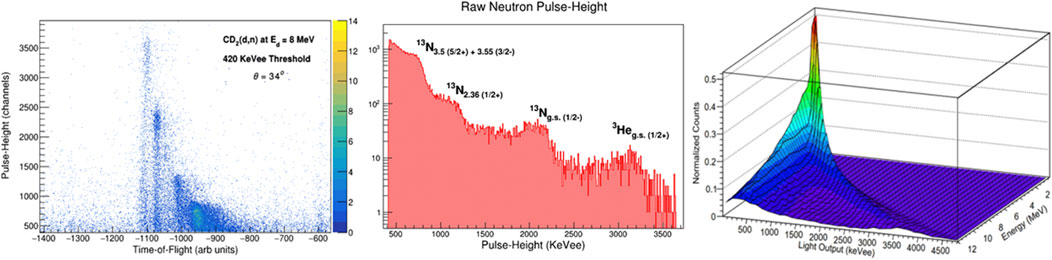

For the extraction of neutron energies via unfolding, the pulse height spectrum was analyzed. The raw pulse-height spectra of the detectors are obtained by gating the neutron events in the PSD plots and projecting onto the long-integration axis. A correlation matrix, ToF vs pulse height, of neutron events from interaction of an 8-MeV deuteron beam with the target is shown in Figure 9. It can be seen that the most energetic neutrons have the highest pulse-height values. The raw pulse-height spectra show distinctive shoulders that shift to the right as the neutron energy increases and can be attributed to separate states populated in the reaction. A typical raw pulse height spectrum is shown in Figure 9.

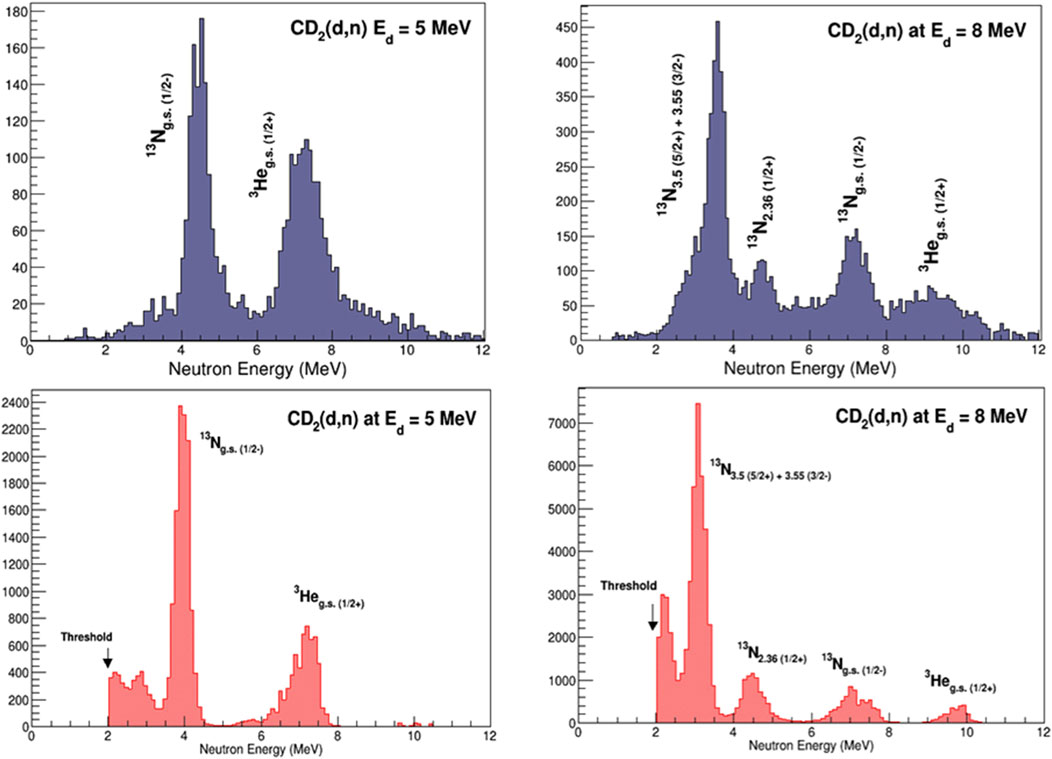

To unfold the neutron energies, a response matrix needs to be created. The response matrix correlates the light-output (or pulse-height) spectra of the detectors with the neutron energies and the detector efficiencies. A statistical method is then employed to extract energies of incident neutrons by comparing to the response matrix of the detector in an iterative process. The present data were analyzed using a response matrix simulated with the Monte Carlo neutron-particle transport code MCNP6 [32] and validated using selected mono-energetic neutrons from the reaction [30, 33]. The response matrix for one of the “large” CATRiNA detectors is shown in Figure 9. The neutron energies extracted via unfolding method were obtained using a statistical algorithm with the Maximum-Likelihood Expectation Method (MLEM) [30, 33]. Neutron energies obtained by the described spectrum unfolding method were compared with the neutron energies obtained from the ToF method. States in 13N were populated by the 12C (d,n)13N reaction. At MeV, the energy of neutrons corresponding to the population of the ground state in 13N is around 4 MeV for the angles measured. Similarly, the ground state in 3He populated by the 2HHe reaction is visible at MeV. A software threshold cut of around 2 MeV was placed on the neutron energies to minimize neutron background and obtain a clean separation with the CATRiNA detectors. The neutron spectra for a detector placed at 34 obtained by both methods is shown in Figure 10. As the beam energy was increased, other features of the spectrum became visible. At MeV, neutrons corresponding to the g.s in 13N have neutron energies of around 7.2 MeV. In addition, neutrons corresponding to the population of the first excited state in 13N at = 2.36 MeV are detected at 4.8 MeV, and a doublet with spin-parity assignments of and , respectively, and MeV is observed at 3.6 MeV. The ground state in 3He is now visible at around 9.5 MeV.

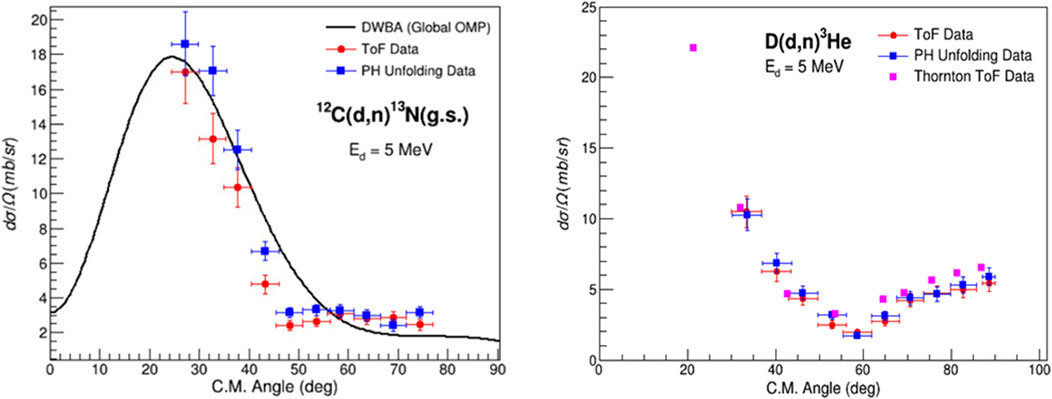

The direct comparison of neutron spectra obtained by ToF and by unfolding procedures in Figure 10 shows the potential of the CATRiNA detectors. Since the commissioning experiment reported here, the unfolding method has been improved with better experimental response matrices, which initially limited the resolution of the CATRiNA detectors. A Novel Unfolding algorithm Using Bayesian Iterative Statistics (anubis) was developed. ANUBIS takes into account uncertainties associated with the unfolding algorithm and determines stopping criteria to optimize the procedure [31]. Angular distributions from the and from the 2HHe reactions using a 5-MeV deuteron beam are shown in Figure 11. Comparison between the angular distributions with ToF and unfolding methods are in very good agreement, additionally validating the two independent approaches.

CATRiNA is envisioned to play a central role at the John D. Fox Laboratory for neutron spectroscopy studies as well as for coincidence measurements between neutrons, rays, and charged particles using the different detector systems available at the laboratory.

2.3 The CLARION2+TRINITY array for high-resolution -ray spectroscopy and reaction-channel selection

CLARION2-TRINITY is a new setup at the John D. Fox Laboratory for high-resolution -ray spectroscopy in conjunction with charged particle detection [13]. The rays are recorded by Clover-type High-Purity Germanium detectors (HPGe) detectors. The geometry is chosen to be non-Archimedian and detectors are arranged such that no detectors have a separation of to suppress coincident detection of 511-keV rays from pair production. The TRINITY particle detector uses a relatively new type of scintillator, Gadolinium Aluminum Gallium Garnet () doped with Cerium (GAGG:Ce). This scintillator has intrinsic particle discrimination capabilities through two decay components with different decay times and varying relative amplitudes. The particle identification with the GAGG:Ce is obtained by comparing waveform integrals of the fast “peak” and the delayed “tail”. The ratio of these two quantities allows to discriminate between protons, particles, and heavier ions. The array was commissioned in December 2021 with nine clover-type HPGe detectors and two rings of GAGG:Ce scintillators [13]. This initial setup has now been augmented with a tenth clover-type HPGe detector and all five GAGG:Ce rings of TRINITY installed. More details on the combined setup including a description of energy-loss and contaminant measurements with the zero-degree GAGG:Ce detector can be found in [13]. The first science publication from the array features results from the safe Coulomb excitation of Ti isotopes and focuses on the suppression of quadrupole collectivity in 49Ti [34].

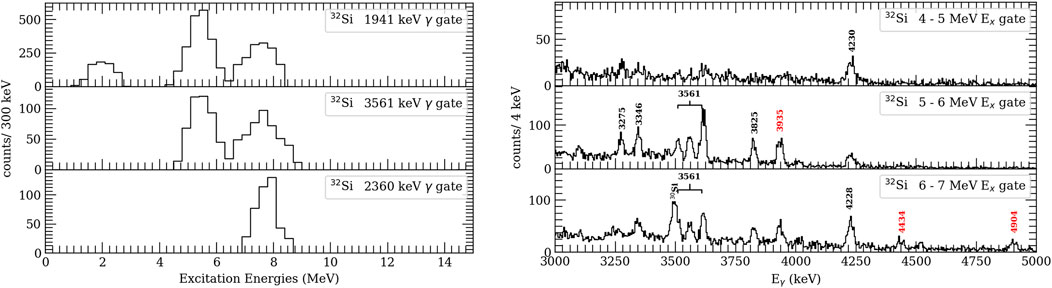

The setup has also been used to study unstable 32Si in the fusion-evaporation reaction. The weak evaporation channel could be isolated selectively by detecting both protons with TRINITY. For this reaction, triple coincidences between the two protons and rays were detected with CLARION2+TRINITY. As the beam energy is precisely known and the setup allows to measure the energies and angles of the outgoing protons, the excitation energy in 32Si, from which rays were emitted, as well as the velocity and direction of the 32Si recoil at the time of emission of the ray could be reconstructed. As the “complete” kinematics of the reaction are known, excitation-energy gated -ray spectra as well as -transition gated excitation-energy spectra could be generated (see Figure 12 for an example). As can be seen in Figure 12, the combined CLARION2+TRINITY system provides high resolution for rays and moderate resolution in the excitation-energy spectra, mainly due to the target thickness and limited energy resolution of the GAGG:Ce scintillators of TRINITY. For the reaction, which is a weak reaction channel, excitation-energy gating provided considerably better statistics for angular distribution and polarization analysis of -ray transitions than a conventional -coincidence analysis. Some details of the reaction-channel selection were already discussed in [13]. More details and results will be presented in a forthcoming publication.

3 Selected science highlights (2020–2024)

3.1 Single-particle strengths around measured with the SE-SPS

Spectroscopic factors obtained from one-nucleon adding and removal reactions have been critically discussed in recent years, especially for rare isotopes with large proton to neutron separation energy asymmetries (see, e.g., Refs. [35–37] and references therein). In stable nuclei, it is commonly accepted that only about 60 of the predicted spectroscopic strengths are observed experimentally (see, e.g., compilations in Refs. [36–40]). Often, systematics are, however, only available for a few selected nuclei, a few isotopic or isotonic chains, and for the spectroscopic strength of a specific single-particle orbit.

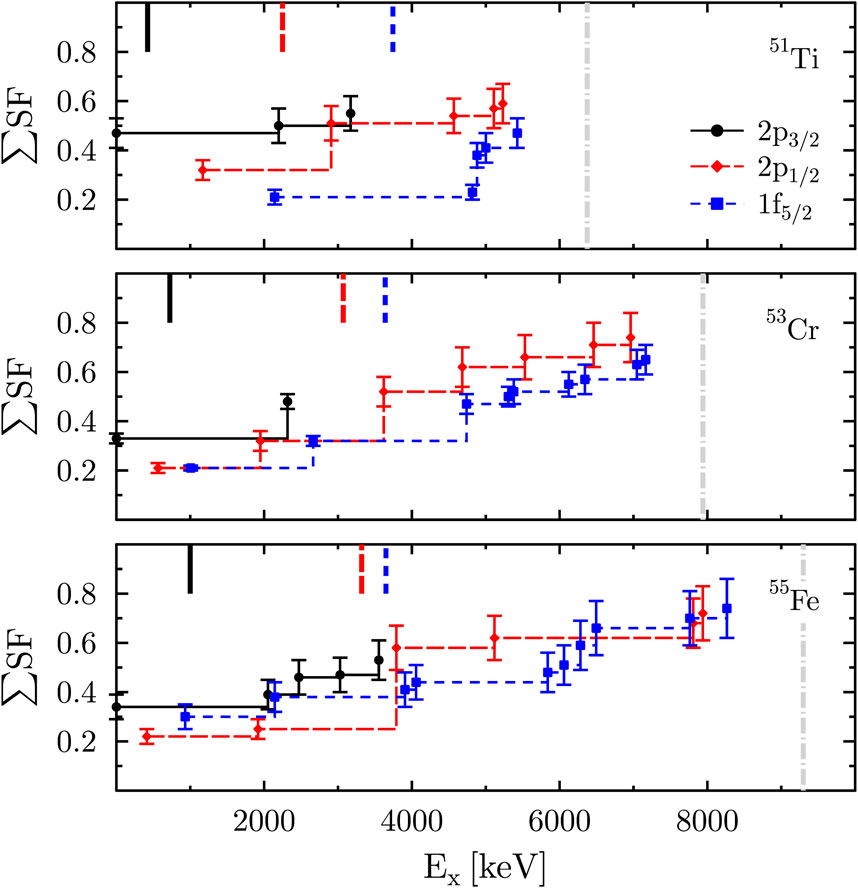

In Figure 13, we show a systematic study of the running sum for the neutron spectroscopic factors for the even-, isotones; is the single particle cross section predicted for an excited state with excitation energy from ADW calculations. The isotones were studied at the FSU SE-SPS in experiments [18, 19, 21]. As can be seen, about of the expected strength are exhausted in all three nuclei and for all three single-particle orbitals. However, it is also quite clear that it is not sufficient to just study the first few excited states. Significant parts of the , and spectroscopic strengths are fragmented to excited states with higher excitation energies. Especially for the and strengths, the strength is fragmented among excited states up to the neutron-separation energy, . Studying the fragmentation of the spectroscopic strengths in experiments up to such high energies allows for a more reliable extraction of the centroid energies of the neutron single-particle orbitals. It should be noted though, that, if orbitals were partially filled, one would in general need to perform both the adding and removal reactions to experimentally determine occupancies and the real single-particle orbital energies (see, e.g. [41, 42], and comments therein).

With our new data on the energies of the single-particle orbitals, we could address the disappearance of the and subshell gaps in the heavier isotones. The subshell gap for Ca and Ti isotopes, and its disappearance in Cr and Fe isotopes were discussed previously (see, e.g. [43, 44], and references therein). In Ref. [18], it was stated that the closure of the subshell gap in the transition from Ti to Cr would need to be explained by the placement of the neutron orbit relative to the orbit. Within the remaining uncertainties discussed in [18, 19, 21], our recent studies indeed support that the gap between these two orbits shrinks with increasing proton number (see Figure 13), possibly explaining the closing of the subshell gap in heavier isotones. The data do, however, also show that rather than the centroid coming significantly down in energy, it is the orbital’s centroid energy which increases. This is different from the initial hypothesis [18] and underlines the importance of performing systematic studies of spectroscopic strengths along isotopic and isotonic chains. The disappearance of the gap between the and neutron orbits with increasing proton number might also explain the possibly very localized occurrence of the subshell gap (see [45] and references therein).

3.2 The neutron one-particle-one-hole structure of the pygmy dipole resonance

The pygmy dipole resonance (PDR) has been observed on the low-energy tail of the isovector giant dipole resonance (IVGDR) below and above the neutron-separation threshold. While the additional strength is recognized as a feature of the electric dipole response of many nuclei with neutron excess [46–48], its microscopic structure, which intimately determines its contribution to the overall strength, is still poorly understood making reliable predictions of the PDR in neutron-rich nuclei far off stability difficult. It has been shown that the coupling to complex configurations drives the strength fragmentation for both the IVGDR and the PDR, and that more strength gets fragmented to lower energies when including such configurations (see the review article [48]). The wavefunctions of states belonging to the PDR are, however, expected to be dominated by one-particle-one-hole (1p-1h) excitations of the excess neutrons. First experiments were performed to access these parts of the wavefunction via inelastic proton scattering through isobaric analog resonances and via one-neutron transfer experiments. The experimental results were compared to predictions from large scale shell model calculations including up to two-particle-two-hole (2p-2h) excitations for both protons and neutrons, and to quasiparticle phonon model (QPM) calculations including up to 3-phonon excitations. The comparison of experiment and theory for doubly-magic 208Pb [49] and semi-magic 120Sn [50] indicates that PDR states’ wavefunctions are indeed largely dominated by 1p-1h excitations of the excess neutrons. It is important to note that experiments are not able to access all relevant neutron 1p-1h configurations within one even-even nucleus as only those can be populated that can be reached from the ground state of the even-odd target nucleus. Therefore, experiments performed along isotopic and isotonic chains are instructive. While these probe neutron configurations above the Fermi surface, and reactions can be used to study some of the relevant configurations below the Fermi surface.

First experiments were performed with the SE-SPS to study the emergence of the PDR around the shell closure. Results for 62Ni have been published [20]. A complimentary real photon scattering experiment was performed to aid the identification of the PDR states up to an excitation energy of MeV. As data are available up to , a follow-up experiment was performed at the high intensity -ray source (HIS) of the Triangle Universities Nuclear Laboratory (TUNL), which is currently being analyzed. As discussed in [20], the combined data allowed us to exclude a significant contribution of the neutron 1p-1h configuration to the wavefunctions below and, thus, to conclude that any strength increase beyond would need to be linked to either the or configurations if the predictions of Inakura et al. were correct [51].

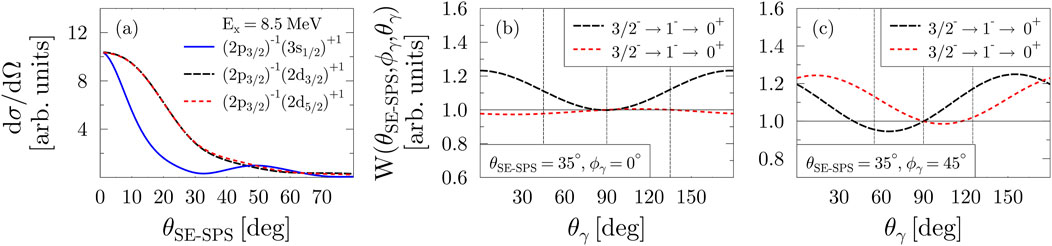

While transfers can be easily determined through angular distributions, the and neutron 1p-1h configurations cannot be distinguished in SE-SPS singles experiments with an unpolarized deuteron beam (see Figure 14A for the angular distributions calculated with chuck3 [26]). Particle- correlations provide, however, the means to discriminate between spin-orbit partners. See Figures 14B, C for the particle- angular correlations calculated with angcor [27] for a fixed polar angle and two different azimuthal angles. The correlations are expected to look quite different for varying azimuthal angles and, thus, provide additional sensitivity for discriminating between the spin-orbit partners. As mentioned in Section. 2.1.1, the full CeBrA array will enable measurements at different angles.

experiments have already been performed for nuclei close to with the extended CeBrA demonstrator (see Figure 5) to study the -ray strength function (SF) via the surrogate reaction method (SRM). As can be seen in Figure 6, the energy resolution of the detectors is sufficient to resolve several low-energy -ray transitions resulting from the deexcitation of low-lying excited states fed by higher-lying states. Therefore, the normalized -ray yields can be determined as a function of excitation energy providing the data for the SRM to constrain the SF [52]. The SE-SPS allows to perform these experiments well past the neutron-separation energy. The indirectly extracted SF from can then be compared to the ground-state SF measured in real-photon scattering, possibly helping to understand whether the PDR is only a feature of the ground state SF. The complimentary singles data provide the means to test the microscopic details of wavefunctions predicted by theoretical models that mean to describe the SF as also discussed in [49, 50].

3.3 Nuclear astrophysics studies with CATRiNA

The CATRiNA neutron detectors are aimed to be used in coincidence with other detector systems at the John D. Fox Laboratory. For instance, we recently performed a resonance spectroscopy study to constrain the 25AlSi reaction rate via a very selective coincidence measurement [53].

The detection of the long-lived radioisotope 26Al (, = yr) in the Galaxy via the satellite based observation of its characteristic 1.809-MeV -ray line is of paramount relevance in nuclear astrophysics [54]. This observation is recognized as direct evidence that nucleosynthesis is an ongoing process in the Galaxy, explaining earlier measurements of the excess of 26Mg found in meteorites and presolar dust grains [55, 56]. The COMPTEL [57] and INTEGRAL [58] space missions have mapped the intensity distribution of the 1.809-MeV -ray line and inferred an equilibrium mass of solar masses of 26Al in the Milky Way, with most of its mass accumulated in regions of star formation co-rotating with the plane of the Galaxy [59]. To understand the stellar nucleosynthesis of 26Al, one needs to understand all the reactions that produce and destroy 26Al in the relevant astrophysical scenarios. An additional complication to the accurate modeling and calculation of its nucleosynthesis comes from the short-lived isomeric state in 26Al (, = 6.4 s) located 228 keV above the long-lived ground state [60].

At nova burning temperatures of GK, the 25AlSi reaction and the subsequent -decay of 26Si leads predominantly to the population of 26Al in its short-lived isomeric state (26) rather than its ground state (26). The isomeric 26 () state directly -decays to the ground state of 26Mg (), bypassing the emission of the 1.809-MeV -ray line. Therefore, 26Al could contribute to the 26Mg abundance measured in meteorites and pre-solar grains without space telescopes observing its associated ray.

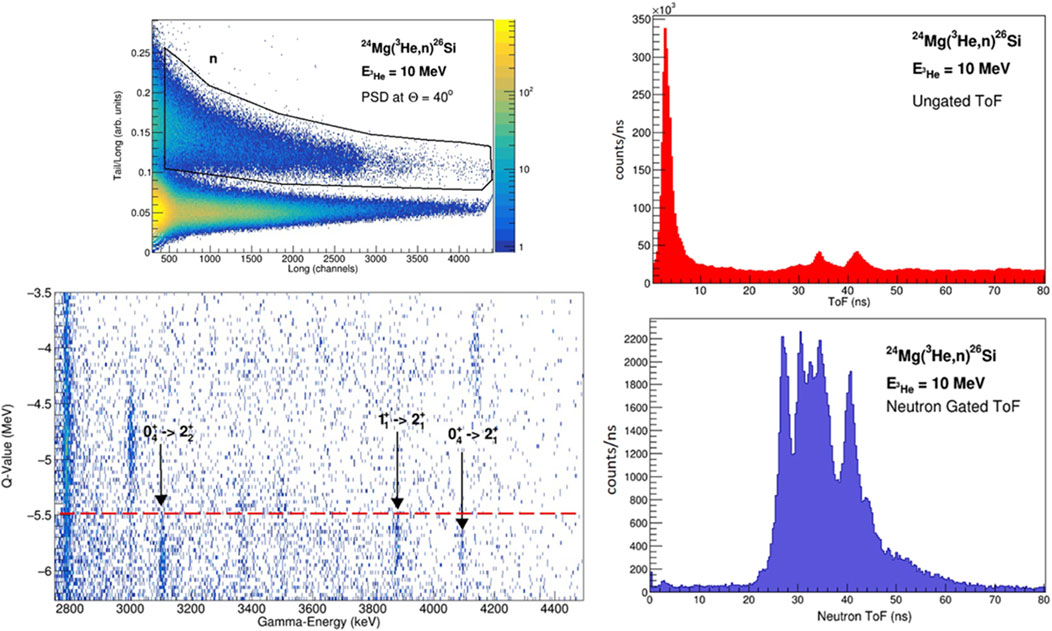

A high-resolution measurement at the John D. Fox Laboratory was conducted to populate low-lying proton resonances in 26Si using the reaction to resolve outstanding discrepancies on the properties of the resonances relevant for the calculation of the 25AlSi reaction rate. Specifically, we focused on five low-lying resonances within the Gamow window of this reaction [61]. For the experiment, a stable 10-MeV 3He beam from the FN Tandem accelerator was used to bombard an enriched 492-g/ self-supporting 24Mg target. The 3He beam was bunched to 1.7-ns width with intervals of 82.5 ns. The unreacted beam was sent into a thick graphite disk acting as beam-stop located 2 m downstream from the target position. Neutrons from the reaction were measured with a set of 16 CATRiNA neutron detectors placed at a distance of 1 m from the reaction target covering an angular range of = . A set of three FSU, Clover-type HPGe -ray detectors, placed at 90 from the target, were used to measure rays from deexcitations of populated states in 26Si in coincidence. The PSD capabilities of CATRiNA were used to separate neutron from events detected in the CATRiNA detectors. The neutron gate in the PSD plots were then applied to the raw ToF spectra to obtain neutron-ToF spectra for all the CATRiNA detectors as shown in Figure 15.

The ToF spectrum of each detector cannot be easily added together since neutrons arriving at each detector from a given populated state in 26Si have different energies due to the reaction kinematics. The neutron events for all 16 CATRiNA detectors were added together in a -value plot of the reaction. Given that the -value of the reaction for the ground-state is small ( = 70 keV), the -value plot can be read as the negative excitation energy of 26Si. The states of interest, low-lying proton resonances in 26Si, are located below ,MeV ( MeV). A -value vs. -ray energy correlation matrix was then built for events in coincidence between CATRiNA detectors and the FSU Clover-type HPGe detectors. Several transitions from resonant states are well resolved due to the high resolution of the -ray detectors. An example of this 2D correlation matrix is shown in Figure 15, expanded on states above the proton-separation threshold (states below the red dotted line) in coincidence with rays between MeV. One can clearly identify transitions corresponding to deexcitation of the and the states, respectively. Using the extracted spectroscopic information of relevant resonances in 26Si, we calculated the rate of the 25AlSi reaction over nova temperatures resolving long standing discrepancies in the literature. See [53] for more details.

4 Summary and outlook

This article highlighted recently commissioned setups for particle- coincidence experiments at the FSU John D. Fox Superconducting Linear Accelerator Laboratory. Particularly, the combined CeBrA + SE-SPS setup for light-ion transfer experiments and coincident -ray detection, the coupling of the CATRiNA neutron detectors with HPGe detectors measuring neutron- coincidences for reaction-channel selection, and the combined CLARION2+TRINITY setup for high resolution -ray spectroscopy were featured. These setups allow to perform selective experiments addressing open questions in nuclear structure, nuclear reactions, and nuclear astrophysics. studies of single-particle orbitals close to the neutron-shell closure, of the pygmy dipole resonance (PDR), and of the reaction to resolve outstanding discrepancies on the properties of the resonances relevant for the calculation of the 25AlSi reaction rate were discussed. In the next couple of years, the full CeBrA array consisting of 14 detectors will be completed. For the SE-SPS, plans are also in place to design a new focal-plane detector with increased position resolution and higher count rate capabilities based on the multi-layer thick gaseous electron multiplier (M-THGEM) technology [62–64], which also allows for the detection of heavier ions opening new possibilities for experimental studies. In addition, the design of a compact mini-orange conversion electron spectrometer for particle-electron coincidence experiments at the SE-SPS is nearly completed. In the near future, the CATRiNA detectors will be coupled with the CLARION2 HPGe detectors increasing the -ray efficiency significantly compared to previous experiments described in this article. Opportunities for coupling CATRiNA with the SE-SPS for charged-particle-neutron coincidence measurements are also being explored.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

M-CS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing. SA-C: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The FSU group acknowledges support by the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) under Grant Nos. PHY-2012522 (WoU-MMA: Studies of Nuclear Structure and Nuclear Astrophysics) and PHY-2412808 (Studies of Nuclear Structure and Nuclear Astrophysics), and by the U.S. Department of Energy, National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) under Grant No. DE-NA0004150 [Center for Excellence in Nuclear Training And University-based Research (CENTAUR)] as part of the Stewardship Science Academic Alliances Centers of Excellence Program. Support by Florida State University is also gratefully acknowledged.

Acknowledgments

M-CS and SA.C. express their gratitude to the staff at the John D. Fox Laboratory for their continued support of the research program. Input from Samuel L. Tabor and Vandana Tripathi for the description of CLARION2+TRINITY, and from John D. Fox Laboratory Director Ingo Wiedenhöver is gratefully acknowledged. The authors thank Kirby W. Kemper for input for the history of the laboratory. M-CS thanks Ben Crider from Mississippi State University for the temporary loan of his inch detectors, and Lewis A. Riley from Ursinus College as well as Paul D. Cottle from Florida State University for the continuing and productive collaboration. SA.C. thanks former FSU graduate students Jesus Perello and Ashton Morelock for the contributions to the development of CATRiNA during their graduate work. M-CS also thanks FSU graduate students Alex L. Conley, Dennis Houlihan, and Bryan Kelly for their contributions to the presented work.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

2. Carter E, Davis R. He-H2-and other negative ion beams available from a duoplasmatron ion source with gas charge exchange. Rev Scientific Instr (1963) 34:93–6. doi:10.1063/1.1718134

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

3. Fox J, Moore C, Robson D. Excitation of isobaric analog states in 89Y and 90Zr. Phys Rev Lett (1964) 12:198–200. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.12.198

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

4. Chapman K. Florida State University superconducting booster. Nucl Instr Methods (1981) 184:239–45. doi:10.1016/0029-554X(81)90875-2

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

5. Fox J, Frawley A, Myers E, Wright L, Chapman K, Smith D, et al. The Florida State University superconducting heavy ion linear accelerator — recent progress. Nucl Instr Methods Phys Res Section B: Beam Interactions Mater Atoms (1987) 24-25:757–8. doi:10.1016/S0168-583X(87)80240-9

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

6. Myers E, Chapman K, Fox J, Frawley A, Allen P, Faragasso J, et al. Status of the Florida State University superconducting linear accelerator. Nucl Instr Methods Phys Res Section B: Beam Interactions Mater Atoms (1989) 40-41:904–7. doi:10.1016/0168-583X(89)90504-1

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

7. Wiedenhoever I, Baby LT, Santiago-Gonzales D, Rojas A, Blackmon JC, Rogachev GV, et al. Studies of exotic nuclei at the RESOLUT facility of Florida state university. In: JH Hamilton, and AV Ramayya, editors. Fission and properties of neutron-rich nuclei - proceedings of the fifth international conference on ICFN5. World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd. (2013). p. 144–51. doi:10.1142/9789814525435_0015

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

8. Koshchiy E, Blackmon J, Rogachev G, Wiedenhöver I, Baby L, Barber P, et al. ANASEN: the array for nuclear astrophysics and structure with exotic nuclei. Nucl Instr Methods Phys Res Section A: Acc Spectrometers, Detectors Associated Equipment (2017) 870:1–11. doi:10.1016/j.nima.2017.07.030

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

9. Baby L, Kuvin S, Wiedenhöver I, Anastasiou M, Caussyn D, Colbert K, et al. RESONEUT: a detector system for spectroscopy with (d,n) reactions in inverse kinematicsn reactions in inverse kinematics. Nucl Instr Methods Phys Res Section A: Acc Spectrometers, Detectors Associated Equipment (2018) 877:34–43. doi:10.1016/j.nima.2017.09.019

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

10. Asher B, Almaraz-Calderon S, Baby L, Gerken N, Lopez-Saavedra E, Morelock A, et al. The encore active target detector: a multi-sampling ionization chamber. Nucl Instr Methods Phys Res Section A: Acc Spectrometers, Detectors Associated Equipment (2021) 1014:165724. doi:10.1016/j.nima.2021.165724

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

11. Good E, Sudarsan B, Macon K, Deibel C, Baby L, Blackmon J, et al. SABRE: the silicon array for branching ratio experiments. Nucl Instr Methods Phys Res Section A: Acc Spectrometers, Detectors Associated Equipment (2021) 1003:165299. doi:10.1016/j.nima.2021.165299

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

12. Conley A, Kelly B, Spieker M, Aggarwal R, Ajayi S, Baby L, et al. The CeBrA demonstrator for particle-γ coincidence experiments at the FSU Super-Enge Split-Pole Spectrograph. Nucl Instr Methods Phys Res Section A: Acc Spectrometers, Detectors Associated Equipment (2024) 1058:168827. doi:10.1016/j.nima.2023.168827

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

13. Gray T, Allmond J, Dowling D, Febbraro M, King T, Pain S, et al. CLARION2-TRINITY: a Compton-suppressed HPGe and GAGG: Ce-Si-Si array for absolute cross-section measurements with heavy ions. Nucl Instr Methods Phys Res Section A: Acc Spectrometers, Detectors Associated Equipment (2022) 1041:167392. doi:10.1016/j.nima.2022.167392

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

14. Enge HA. Magnetic spectrographs for nuclear reaction studies. Nucl Instr Methods (1979) 162:161–80. doi:10.1016/0029-554X(79)90711-0

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

16. Good EC. A study of 26Al (p, γ)27Si with the silicon array for branching ratio experiments (SABRE). Ph.D. thesis, Louisiana State University (2020).

Google Scholar

17. DeVries R, Shapira D, Clover M. Increasing a spectrometer’s solid angle without loss of resolution. Nucl Instr Methods (1977) 140:479–80. doi:10.1016/0029-554X(77)90364-0

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

18. Riley LA, Nebel-Crosson JM, Macon KT, McCann GW, Baby LT, Caussyn D, et al. 50Ti(d, p)51Ti: single-neutron energies in the N=29 isotones, and the N=32 subshell closure. Phys Rev C (2021) 103:064309. doi:10.1103/PhysRevC.103.064309

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

19. Riley LA, Hay ICS, Baby LT, Conley AL, Cottle PD, Esparza J, et al. 54Fe(d, p)55Fe and the evolution of single neutron energies in the N=29 isotones. Phys Rev C (2022) 106:064308. doi:10.1103/PhysRevC.106.064308

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

20. Spieker M, Baby LT, Conley AL, Kelly B, Müscher M, Renom R, et al. Experimental study of excited states of 62Ni via one-neutron (d, p) transfer up to the neutron-separation threshold and characteristics of the pygmy dipole resonance states. Phys Rev C (2023) 108:014311. doi:10.1103/PhysRevC.108.014311

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

21. Riley LA, Simms DT, Baby LT, Conley AL, Cottle PD, Esparza J, et al. g9/2 neutron strength in the N=29 isotones and the 52Cr(d, p)53Cr reaction. Phys Rev C (2023) 108:044306. doi:10.1103/PhysRevC.108.044306

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

22. Hay ICS, Cottle PD, Riley LA, Baby LT, Baker S, Conley AL, et al. Measurement of g9/2 strength in the stretched 8− state and other negative parity states via the 51V(d, p)52V reaction. Phys Rev C (2024) 109:024302. doi:10.1103/PhysRevC.109.024302

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

23. Kuchera AN, Hoffman CR, Ryan G, D’Amato IB, Guarinello OM, Kielb PS, et al. Single-neutron adding on 34S. The Eur Phys J A (2024) 60:176. doi:10.1140/epja/s10050-024-01399-z

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

25. Riley LA, Spieker M, Cottle PD, et al. A study of the 52Cr53(d, pγ)53Cr reaction with the CeBrA demonstrator (2024).

Google Scholar

26. Kunz PD, Comfort JR. Extended version (unpublished). Program CHUCK3 (1978).

Google Scholar

27. Harakeh MN, Put LW. KVI internal report 67i, (unpublished). Program ANGCOR (1979).

Google Scholar

28. Rybicki F, Tamura T, Satchler G. Particle-gamma angular correlations following nuclear reactions. Nucl Phys A (1970) 146:659–76. doi:10.1016/0375-9474(70)90748-7

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

29. Thompson IJ. Coupled reaction channels calculations in nuclear physics. Comput Phys Rep (1988) 7:167–212. doi:10.1016/0167-7977(88)90005-6

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

30. Perello J, Almaraz-Calderon S, Asher B, Baby L, Gerken N, Hanselman K. Characterization of the CATRiNA neutron detector system. Nucl Instr Methods Phys Res Section A: Acc Spectrometers, Detectors Associated Equipment (2019) 930:196–202. doi:10.1016/j.nima.2019.03.084

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

31. Morelock A, Perello J, Almaraz-Calderon S, Asher B, Brandenburg K, Derkin J, et al. Characterization and description of a spectrum unfolding method for the CATRiNA neutron detector array. Nucl Instr Methods Phys Res Section A: Acc Spectrometers, Detectors Associated Equipment (2022) 1034:166759. doi:10.1016/j.nima.2022.166759

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

32. Goorley T, James M, Booth T, Brown F, Bull J, Cox L, et al. Initial MCNP6 release overview. Nucl Technol (2012) 180:298–315. doi:10.13182/NT11-135

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

33. Perello Izaguirre J. Study of low-lying proton resonances in 26Si and neutron spectroscopic studies with CATRiNA. Ph.D. thesis, Florida State University (2021).

Google Scholar

34. Gray T, Allmond J, Benetti C, Wibisono C, Baby L, Gargano A, et al. Suppressed electric quadrupole collectivity in 49ti. Phys Lett B (2024) 855:138856. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2024.138856

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

35. Lee J, Tsang MB, Bazin D, Coupland D, Henzl V, Henzlova D, et al. Neutron-proton asymmetry dependence of spectroscopic factors in Ar isotopes. Phys Rev Lett (2010) 104:112701. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.104.112701

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

36. Tostevin JA, Gade A. Updated systematics of intermediate-energy single-nucleon removal cross sections. Phys Rev C (2021) 103:054610. doi:10.1103/PhysRevC.103.054610

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

37. Kay BP, Tang TL, Tolstukhin IA, Roderick GB, Mitchell AJ, Ayyad Y, et al. Quenching of single-particle strength in A=15 nuclei. Phys Rev Lett (2022) 129:152501. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.129.152501

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

38. Lee J, Tsang MB, Lynch WG. Neutron spectroscopic factors from transfer reactions. Phys Rev C (2007) 75:064320. doi:10.1103/PhysRevC.75.064320

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

39. Lee J, Tsang MB, Lynch WG, Horoi M, Su SC. Neutron spectroscopic factors of ni isotopes from transfer reactions. Phys Rev C (2009) 79:054611. doi:10.1103/PhysRevC.79.054611

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

40. Tsang MB, Lee J, Su SC, Dai JY, Horoi M, Liu H, et al. Survey of excited state neutron spectroscopic factors for Z=8−28 nuclei. Phys Rev Lett (2009) 102:062501. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.102.062501

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

41. Schiffer JP, Hoffman CR, Kay BP, Clark JA, Deibel CM, Freeman SJ, et al. Test of sum rules in nucleon transfer reactions. Phys Rev Lett (2012) 108:022501. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.108.022501

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

42. Schiffer JP, Hoffman CR, Kay BP, Clark JA, Deibel CM, Freeman SJ, et al. Valence nucleon populations in the Ni isotopes. Phys Rev C (2013) 87:034306. doi:10.1103/PhysRevC.87.034306

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

43. Prisciandaro J, Mantica P, Brown B, Anthony D, Cooper M, Garcia A, et al. New evidence for a subshell gap at N=32. Phys Lett B (2001) 510:17–23. doi:10.1016/S0370-2693(01)00565-2

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

44. Leistenschneider E, Reiter MP, Ayet San Andrés S, Kootte B, Holt JD, Navrátil P, et al. Dawning of the N=32 shell closure seen through precision mass measurements of neutron-rich titanium isotopes. Phys Rev Lett (2018) 120:062503. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.120.062503

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

45. Liu HN, Obertelli A, Doornenbal P, Bertulani CA, Hagen G, Holt JD, et al. How robust is the N=34 subshell closure? First spectroscopy of 52Ar. Phys Rev Lett (2019) 122:072502. doi:10.1103/physrevlett.122.072502

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

46. Savran D, Aumann T, Zilges A. Experimental studies of the pygmy dipole resonance. Prog Part Nucl Phys (2013) 70:210–45. doi:10.1016/j.ppnp.2013.02.003

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

47. Bracco A, Lanza E, Tamii A. Isoscalar and isovector dipole excitations: nuclear properties from low-lying states and from the isovector giant dipole resonance. Prog Part Nucl Phys (2019) 106:360–433. doi:10.1016/j.ppnp.2019.02.001

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

48. Lanza E, Pellegri L, Vitturi A, Andrés M. Theoretical studies of pygmy resonances. Prog Part Nucl Phys (2023) 129:104006. doi:10.1016/j.ppnp.2022.104006

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

49. Spieker M, Heusler A, Brown BA, Faestermann T, Hertenberger R, Potel G, et al. Accessing the single-particle structure of the pygmy dipole resonance in 208Pb. Phys Rev Lett (2020) 125:102503. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.125.102503

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

50. Weinert M, Spieker M, Potel G, Tsoneva N, Müscher M, Wilhelmy J, et al. Microscopic structure of the low-energy electric dipole response of 120Sn. Phys Rev Lett (2021) 127:242501. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.127.242501

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

51. Inakura T, Nakatsukasa T, Yabana K. Emergence of pygmy dipole resonances: magic numbers and neutron skins. Phys Rev C (2011) 84:021302. doi:10.1103/PhysRevC.84.021302

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

52. Ratkiewicz A, Cizewski JA, Escher JE, Potel G, Harke JT, Casperson RJ, et al. Towards neutron capture on exotic nuclei: demonstrating (d,pγ) as a surrogate reaction for (n, γ). Phys Rev Lett (2019) 122:052502. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.122.052502

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

53. Perello JF, Almaraz-Calderon S, Asher BW, Baby LT, Benetti C, Kemper KW, et al. Low-lying resonances in 26Si relevant for the determination of the astrophysical 25Al(p, γ)26Si reaction rate. Phys Rev C (2022) 105:035805. doi:10.1103/PhysRevC.105.035805

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

54. Prantzos N, Diehl R. Radioactive 26Al in the galaxy: observations versus theory. Phys Rep (1996) 267:1–69. doi:10.1016/0370-1573(95)00055-0

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

55. Lee T, Papanastassiou DA, Wasserburg GJ. Aluminum-26 in the early solar system: fossil or fuel? Astrophysical J Lett (1977) 211:L107–L110. doi:10.1086/182351

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

56. José J, Hernanz M, Amari S, Lodders K, Zinner E. The imprint of nova nucleosynthesis in presolar grains. Astrophysical J (2004) 612:414–28. doi:10.1086/422569

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

57. Diehl R, Dupraz C, Bennett K, Bloemen H, Hermsen W, Knoedlseder J, et al. COMPTEL observations of Galactic 2̂6Âl emission. Astron Astrophysics (1995) 298:445.

Google Scholar

58. Laurent Bouchet JPR Elisabeth Jourdain. Observation of the 26al emission distribution throughout the galaxy with integral/spi. PoS ICRC2015 (2015) 896. doi:10.22323/1.236.0896

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

60. Iliadis C, Champagne A, Chieffi A, Limongi M. The effects of thermonuclear reaction rate variations on 26Al production in massive stars: a sensitivity study. Astrophysical J Suppl Ser (2011) 193:16. doi:10.1088/0067-0049/193/1/16

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

62. de Olivera R, Cortesi M. First performance evaluation of a multi-layer thick gaseous electron multiplier with in-built electrode meshes—MM-THGEM. J Instrumentation (2018) 13:P06019. doi:10.1088/1748-0221/13/06/P06019

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

63. Cortesi M, Pereira J, Bazin D, Ayyad Y, Cerizza G, Fox R, et al. Development of a novel MPGD-based drift chamber for the NSCL/FRIB S800 spectrometer. J Instrumentation (2020) 15:P03025. doi:10.1088/1748-0221/15/03/P03025

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

64. Ciraldo I, Brischetto G, Torresi D, Cavallaro M, Agodi C, Boiano A, et al. Characterization of a gas detector prototype based on Thick-GEM for the MAGNEX focal plane detector. Nucl Instr Methods Phys Res Section A: Acc Spectrometers, Detectors Associated Equipment (2023) 1048:167893. doi:10.1016/j.nima.2022.167893

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Mark-Christoph Spieker

Mark-Christoph Spieker Sergio Almaraz-Calderon

Sergio Almaraz-Calderon