- Physics Division, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Oak Ridge, TN, United States

The study of direct reactions is of broad interest in nuclear physics, providing constraint to models of nuclear structure evolution and data to better understand the creation of the elements. In many cases, however, the data of interest are hindered by backgrounds and poor resolution from contaminants in either the beam, the target, or both. The use of a gas jet can overcome some of these issues through clever engineering, providing a reaction target that is chemically pure and thin enough to significantly reduce the impact on experimental resolution. This Perspective will discuss the effort to design, construct, and operate gas jet targets for direct reaction studies in the rare isotope era.

1 Introduction

Direct reactions have long been a tool in nuclear physics to probe the evolution of nuclear structure and the role nuclei play in astrophysical events. With the development of rare isotope beams, however, new opportunities brought with them new challenges.

For one, beams of more and more exotic nuclei are less intense, due to the difficulty in producing them (increasing energy and decreasing production cross sections). To achieve the same results, then, either the time for a measurement or the target density must be increased, or indeed both. To ensure that the statistics that are collected do not suffer from backgrounds induced by unwanted target components (such as backing foils or spectator atoms in a chemical compound), pure targets are desired.

In addition to reduced intensities compared to stable beams, rare isotope beams are also more prone to be delivered on-target as “cocktail” beams, with multiple beam constituents alongside the nuclei of interest. This is due to production mechanisms like fragmentation and in-flight reactions. Because reactions are possible on any of the nuclei present in the beam, the purity of the targets is again a significant concern.

Lastly, as rare beams often result in decreased statistics, improvements in detectors are also needed–and need to be accommodated. Next-generation gamma arrays like GRETA [1], high-segmentation, high-coverage charged particle arrays like ORRUBA [2], and electromagnetic devices to separate reactions from unreacted beam like SECAR [3] or EMMA [4], all have strict mechanical and electronic requirements for interfacing with them. A new target technology loses value if it cannot accommodate the new detector technology needed to make use of it.

Gas jet targets take advantage of increased engineering–in the form of more complicated pumping schemes and fluid dynamics borrowed from aerospace–to achieve a dense, pure, and highly localized target of gas, as can be seen in Figure 1.

Some of the earliest gas jets for nuclear reaction studies were built and operated in Germany in the 1970s through the early 2000s [5–17]. Others (e.g., Refs. 18–22) were built in the United States and abroad for various applications. Of these, the Jet Experiments in Nuclear Structure and Astrophysics (JENSA) gas jet target [23–25] is the most dense gas jet target for direct reaction studies in the world.

2 The JENSA gas jet target

To expand the use of gas jets to rare isotope facilities, such as the Argonne Tandem-Linac Accelerator System (ATLAS) facility or the Facility for Rare Isotope Beams (FRIB) in the United States, changes to the basic design of the target were needed. Beam intensities are, by their exotic nature, lower than for stable beams, necessitating an increase in the target density. Correspondingly, lower intensities require more detector coverage to maximize statistics, and the design of the target chamber has to accommodate this. Additional detectors to measure the heavy outgoing recoil or any gamma rays de-exciting the populated levels may also be desired. The Jet Experiments in Nuclear Structure and Astrophysics (JENSA) gas jet target system was designed and built to meet these new requirements.

2.1 15N(

While JENSA was designed explicitly for performing reaction studies in inverse kinematics with rare isotope beams, early science measurements focused on demonstrations of the system performance and comparison to existing reaction data. One such measurement was a study of 15N elastic scattering on a 4He jet target. This measurement was undertaken to constrain R-matrix analysis of the 15N +

Not only were the yields consistent between the two techniques, but the use of the JENSA gas jet target allowed for extension of the scattering data down to much lower center-of-mass angles: as the target exhibits cylindrical symmetry, detectors can be placed all the way to 90

2.2 20Ne(p,d)19Ne

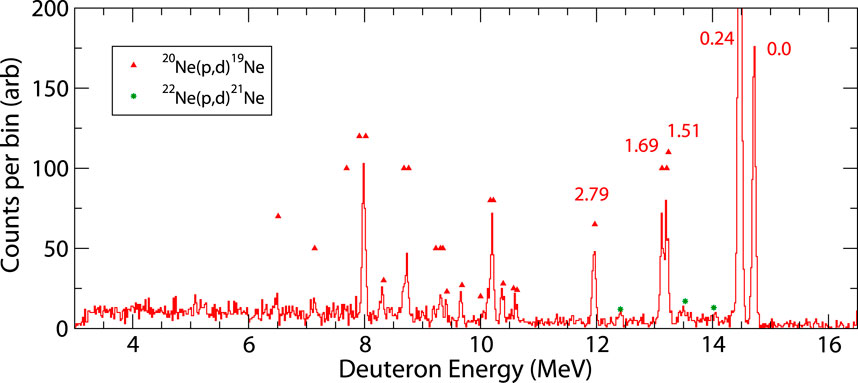

A distinct benefit to the use of gas jets for direct reaction studies is the ability to enable reactions between two gaseous elements to be studied in high precision. A proton beam of 30 MeV, produced by the HRIBF, impinged on the JENSA target operating with natural neon. Deuterons from the (p,d) reaction, populating states in 19Ne of astrophysical interest, were selected in the SIDAR detector array using standard energy loss techniques. An example spectrum is shown in Figure 2. In Figure 6 of Ref. 26, a similar spectrum is compared against the results of a test with a neon-implanted carbon foil. The reduction in background and improvement in the resolution due to JENSA is clear.

Figure 2. Example spectrum, taken for one angle, from the 20Ne(p,d)19Ne reaction measurement using JENSA. The first few states in 19Ne are labeled. Peaks due to reactions on the naturally-occurring 22Ne in the neon gas target (

In the case of 18F(p,

2.3 14N(p,t)12N

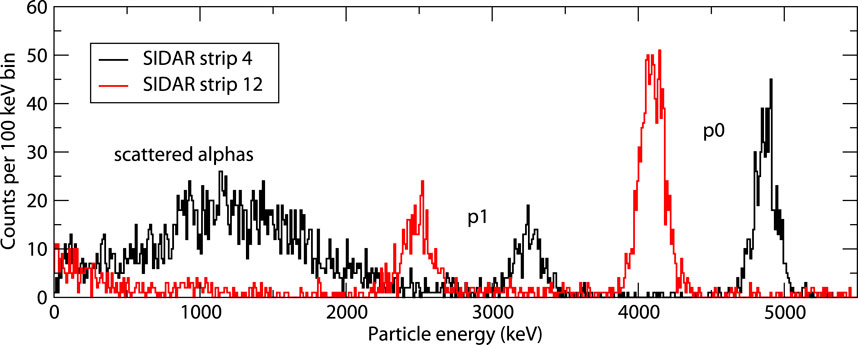

As with gas jets in previous decades, the relatively thin jet (with respect to energy loss) allows for precision particle spectroscopy from direct reaction studies. JENSA was used with a natural nitrogen jet to study the 14N(p,t)12N reaction, looking for potential new levels in 12N. Because the energy straggling of the incoming beam as well as the outgoing tritons through the jet was small, the resolution of the measurement was dominated by the resolution of the detectors (SIDAR in “lampshade” mode), and the width of broad, unbound levels in 12N was immediately apparent in the spectra.

Two potentially new levels were observed in this direct reaction measurement with JENSA, including a strongly-populated level at

In addition to the direct spectroscopy capability, decay particles–such as protons or alphas emitted by the product of the reaction–are able to escape the thin jet target and potentially be detected. In the case of 12N, protons corresponding to the p0 (to the ground state of 11C), p1 (11C

2.4 20Ne(p,t)18Ne

Taking advantage of the unique combination of a gas jet target with a facility able to deliver high-energy proton beams, the 20Ne(p,t)18Ne reaction was studied, again at HRIBF. Due to the very high Q-value barrier for this reaction (

The spin and parity of the level at 6,150 keV, which appeared as a shoulder on top of the 6,297 + 6,353 doublet, has been contested, as has the width of this level: depending on the spin assignment, variations of up to a factor of 2.4 in the 14O(

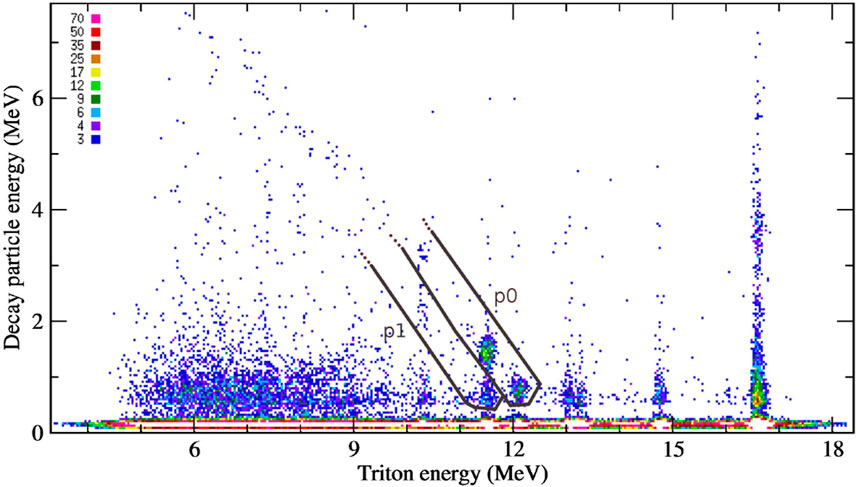

As before, the thin jet target allowed for decay particles to escape and be detected in coincidence with reaction tritons. This is shown in Figure 3. A determination of the branching ratio from the 6,150 keV level to the ground state of 17F will help to confirm whether the state contributes strongly to the 14O(

Figure 3. Preliminary matrix of the energy of any particle in coincidence with a reaction triton from JENSA (vertical axis) versus the triton energy (horizontal axis). Two bands, associated with the p0 and p1 decay channels from 18Ne, are indicated with the black bands. Protons originating from the

2.5 JENSA at ReA3: (

(

During its tenure in the reaccelerated (ReA3) hall at the new Facility for Rare Isotope Beams (FRIB), JENSA has been used to study several (

The 14N(

Figure 4. JENSA 14N(

A spectroscopic measurement of the 34Ar(

3 Combining technologies: the SOLSTISE gas jet

Gas jet targets offer several significant advantages to traditional targets, such as improved resolution, improved purity, and the ability to measure reactions near 90

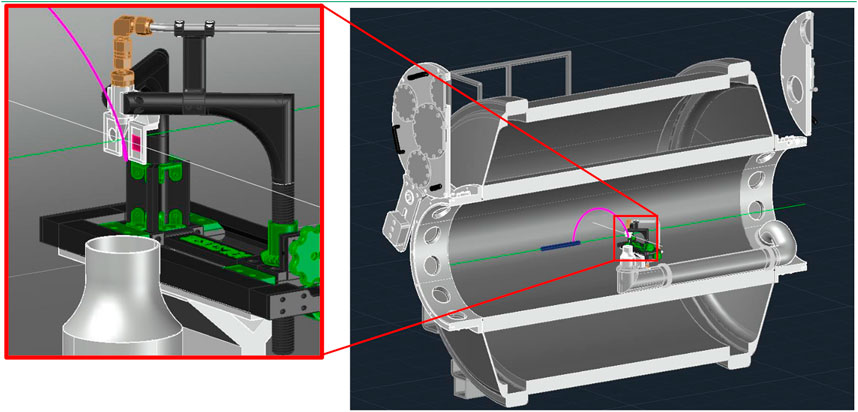

Figure 5. Computer aided design drawing of the SOLSTISE gas jet target setup inside of the SOLARIS solenoidal spectrometer magnet bore. CAD courtesy of M. Hall.

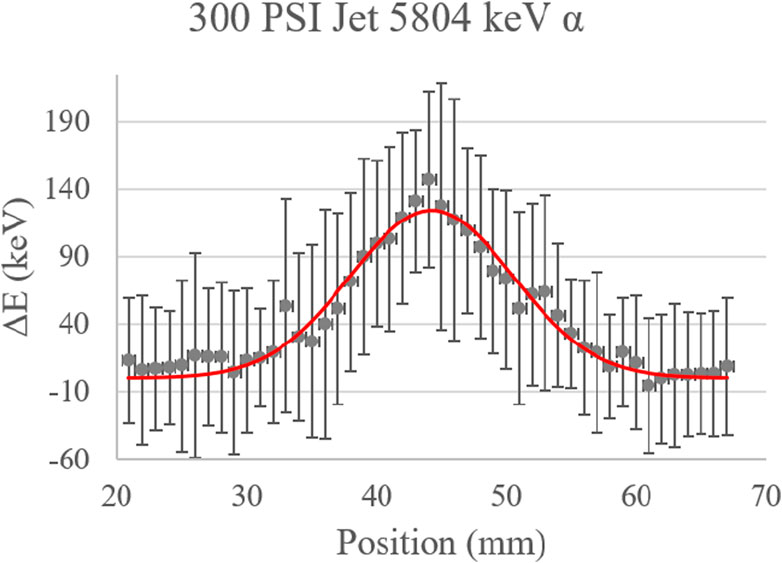

Due to the constraints of operating inside of a solenoidal magnetic field, the design of SOLSTISE is such that the amount of material–in particular, components made from materials which may impact the magnetic field lines–is minimized. In Figure 6, the impact of this design criterion on the size of the jet nozzle is apparent. In fact, the SOLSTISE project has taken significant advantage of additive manufacturing, producing many internal components such as receiver cones, frames, supports, and even jet nozzles using precision 3D printing techniques. Despite these design changes, the SOLSTISE system has been demonstrated to produce an equivalent jet to JENSA for nitrogen (see Figure 7). Additional changes to the pumping scheme between the two systems have resulted in improvements to the SOLSTISE pumping stage pressures, despite a lower overall pumping capacity. A comparison can be seen in Figure 8.

Figure 6. Size comparison between the SOLSTISE (center) and JENSA gas jet nozzles. Despite the difference in external size, the internal nozzle design is the same.

Figure 7. Energy losses for a known alpha source passing through a jet from SOLSTISE produced with 300 psi of nitrogen gas. For nitrogen, an energy loss of

Figure 8. System pressures for SOLSTISE and JENSA compared at various stages, for nitrogen. For equivalent jet densities, the pressures inside the SOLSTISE system are comparable to JENSA.

The SOLSTISE system has been designed to be compatible with both the HELIOS and SOLARIS spectrometers. Plans for first experimental measurements at ATLAS are underway.

4 Conclusion

Ongoing advances in rare isotope beam production, detector technology, analysis techniques, and reaction theory have given us unprecedented access to the nature of exotic nuclei. Gas jets can provide a pure, dense, and localized target to further improve the state of the art of direct reaction measurements.

Data availability statement

The data analyzed in this study is subject to the following licenses/restrictions: Data available upon request. Requests to access these datasets should be directed to Y2hpcHBza2FAb3JubC5nb3Y=.

Author contributions

KC: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This material is based upon work supported by the U.S. DOE, Office of Science, Office of Nuclear Physics under contract DE-AC05-00OR22725 (ORNL).

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the members of the JENSA Collaboration, M. Hall, B. P. Kay, H. Stemp, and M. Cantrell.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. GRETA. GRETA/GRETINA (2024). Available from: https://greta.lbl.gov/ (Accessed October 23, 2024)

2. ORRUBA. ORRUBA (2024). Available from: https://orruba.org/ (Accessed October 23, 2024).

3. Berg GPA, Couder M, Moran MT, Smith K, Wiescher M, Schatz H, et al. Design of SECAR a recoil mass separator for astrophysical capture reactions with radioactive beams. Nucl Instr Methods Phys Res A (2018) 877:87–103. doi:10.1016/j.nima.2017.08.048

4. Davids B, Davids CN. Emma: a recoil mass spectrometer for isac-ii at triumf. Nucl Instr Methods Phys Res Section A: Acc Spectrometers, Detectors Associated Equipment (2005) 544:565–76. doi:10.1016/j.nima.2005.01.297

5. Ulbricht J, Clausnitzer G, Graw G. High density windowless gas target. Nucl Inst Meth (1972) 102:93–9. doi:10.1016/0029-554x(72)90526-5

8. Bittner G, Kretschmer W, Schuster W. A windowless high-density gas target for nuclear scattering experiments. Nucl Instr Meth (1979) 167:1–8. doi:10.1016/0029-554x(79)90465-8

9. Tietsch W, Bethge K. High density windowless gas jet target. Nucl Instr Methods (1979) 158:41–50. doi:10.1016/S0029-554X(79)90340-9

10. Becker H, Buchmann L, Görres J, Kettner K, Kräwinkel H, Rolfs C A supersonic jet gas target for \gamma-ray spectroscopy measurements. Nucl Instr Methods Phys Res (1982) 198:277–92. doi:10.1016/0167-5087(82)90265-4

12. Gorres J, Becker H, Krauss A, Redder A, Rolfs C, Trautvetter H. The influence of intense ion beams on the density of supersonic jet gas targets. Nucl Instr Methods Phys Res Section A: Acc Spectrometers, Detectors Associated Equipment (1985) 241:334–8. doi:10.1016/0168-9002(85)90586-8

15. Griegel T, Drotleff HW, Hammer JW, Knee H, Petkau K. Physical properties of a heavy-ion-beam-excited supersonic jet gas target. J Appl Phys (1991) 69:19–22. doi:10.1063/1.347743

17. Hammer JW, Biermayer W, Grieger T, Knee H, Petkau K. Rhinoceros, the versatile stuttgart gas target facility (part i). unpublished (2000).

18. Shapira D, Ford JLC, Novotny R, Shivakumar B, Parks RL, Thornton ST, et al. The HHIRF supersonic gas jet target facility. Nucl Instr Meth A (1985) 228:259.

19. Kontos A, Schurman D, Akers C, Couder M, Gorres J, Robertson D, et al. Nucl Instr Methods A (2011) 664:272. doi:10.1016/j.nima.2011.10.039

20. Schmid K, Veisz L. Supersonic gas jets for laser-plasma experiments. Rev Sci Instrum (2012) 83:053304. doi:10.1063/1.4719915

21. Rapagnani D, Buompane R, DiLeva A, Gialanella L, Busso M, DeCesare M A supersonic jet target for the cross section measurement of the 12C(a,g)16O reaction with the recoil mass separator ERNA. Nucl Instr Methods Phys Res Section B: Beam Interactions Mater Atoms (2017) 407:217–21. doi:10.1016/j.nimb.2017.07.003

22. Schlimme BS, Aulenbacher S, Brand P, Littich M, Wang Y, Achenbach P, et al. Operation and characterization of a windowless gas jet target in high-intensity electron beams. Nucl Instrum Methods Phys Res A (2021) 1013:165668. doi:10.1016/j.nima.2021.165668

23. Chipps KA, Greife U, Bardayan DW, Blackmon JC, Kontos A, Linhardt LE, et al. The jet experiments in nuclear structure and astrophysics (JENSA) gas jet target. Nucl Instrum Methods Phys Res (2014) A763:553. doi:10.1016/j.nima.2014.06.042

24. Chipps KA. Reaction measurements with the jet experiments in nuclear structure and astrophysics (JENSA) gas jet target. Nucl Instrum Methods Phys Res (2017) B407:297–303. doi:10.1016/j.nimb.2017.07.023

25. Schmidt K, Chipps KA, Ahn S, Bardayan DW, Browne J, Greife U, et al. Status of the JENSA gas-jet target for experiments with rare isotope beams. Nucl Instr Methods Phys Res A (2018) 911:1–9. doi:10.1016/j.nima.2018.09.052

26. Pain SD. Advances in instrumentation for nuclear astrophysics. AIP Adv (2014) 4:041015. doi:10.1063/1.4874116

27. Bardayan DW, Chipps KA, Ahn S, Blackmon JC, deBoer RJ, Greife U, et al. The first science result with the jensa gas-jet target: confirmation and study of a strong subthreshold 18F(p,α)15O resonance. Phys Lett B (2015) 751:311.

28. Bardayan DW, Chipps KA, Ahn S, Blackmon JC, deBoer RJ, Greife U, et al. Spectroscopic study of 20ne+p reactions using the JENSA gas-jet target to constrain the astrophysical 18f(p,α)15o rate. Phys Rev C (2017) 96:055806. doi:10.1103/PhysRevC.96.055806

29. Bardayan DW, Chipps KA, Ahn S, Blackmon JC, Greife U, Jones KL, et al. Particle decay of astrophysically-important 19Ne levels. Journal of physics conference series (IOP). J Phys Conf Ser (2019) 1308:012004. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/1308/1/012004

30. Chipps KA, Pain SD, Greife U, Kozub RL, Nesaraja CD, Smith MS, et al. Levels in 12n via the 14n(p,t) reaction using the JENSA gas-jet target. Phys Rev C (2015) 92:034325. doi:10.1103/PhysRevC.92.034325

31. Chipps KA, Pain SD, Greife U, Kozub RL, Nesaraja CD, Smith MS, et al. Particle decay of proton-unbound levels in 12N. Phys Rev C (2017) 95:044319. doi:10.1103/PhysRevC.95.044319

32. Thompson PJ. A study of spin-parity assignments in 18Ne using the 20Ne(p, t)18Ne reaction. Knoxville, Tennessee: University of Tennessee (2018). Ph.D. thesis.

33. Browne J, Chipps KA, Schmidt K, Schatz H, Ahn S, Pain SD, et al. First direct measurement constraining the 34Ar (α p) 37K reaction cross section for mixed hydrogen and helium burning in accreting neutron stars. Phys Rev Lett (2023) 130:212701. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.130.212701

34. Back BB, Baker SI, Brown BA, Deibel CM, Freeman SJ, DiGiovine BJ, et al. First experiment with HELIOS: the structure of 13B. Phys Rev Lett (2010) 104:132501. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.104.132501

Keywords: nuclear reactions, direct reactions, gas targets, gas jets, nuclear structure

Citation: Chipps KA (2025) Gas jet targets for direct reaction studies. Front. Phys. 12:1507544. doi: 10.3389/fphy.2024.1507544

Received: 21 November 2024; Accepted: 23 December 2024;

Published: 29 January 2025.

Edited by:

Alan Wuosmaa, University of Connecticut, United StatesReviewed by:

Alessandra Guglielmetti, University of Milan, ItalyCopyright © 2025 Chipps. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: K. A. Chipps, Y2hpcHBza2FAb3JubC5nb3Y=

K. A. Chipps

K. A. Chipps